“white women do have it easier”

Amy is joined by Dr. Bri Romanello to discuss the nuanced history and modern ramifications of immigration and interracial marriage across LDS and Latine communities.

Our Guest

Dr. Bri Romanello

Brittany “Bri” Romanello earned a Ph.D. in Sociocultural Anthropology from Arizona State University. Her research in the Southwest and borderland areas used mixed ethnographic methods to understand better how the intersections of race, ethnicity, legal status, and religion shape Latinx immigrants’ lives, social networks, family structures, parenting, and identity. On a personal note, Bri enjoys existing outdoors, buying too many books, cooking, thrifting, cumbias, film and gardening.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: During the first season of the podcast, we examined the origins of patriarchy on a timeline through the history of Western civilization, centered mostly on the United States. During the second season of the podcast, when we solicited listeners’ stories, we were flooded with submissions containing powerful and painful experiences, most of which came from white women, and a large percentage of these women had grown up in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This season, we’ve taken on the huge project of trying to understand patriarchy around the world, region by region, and our past several episodes have focused on Latin America.

Throughout the project, we have discovered ways that systems of oppression intersect, and especially the ways that white American women occupy a position in society where they can be both the oppressed and the oppressor. But until this episode, I had never encountered scholarship that brought the themes of all three podcast seasons together, examining structural patriarchy, white Mormon women, and immigrant women from Latin America. This intersection will hit very close to home for many listeners, so please listen with an open mind and an open heart and join me in welcoming to the podcast our guest, Dr. Bri Romanello. Welcome, Bri!

Dr. Bri Romanello: Hi, good morning!

AA: I’m so happy to have you here with us. I’ll start by reading your professional bio and then, as usual, we’ll ask you to introduce yourself more personally afterwards. Brittany “Bri” Romanello earned a PhD in Sociocultural Anthropology from Arizona State University. Her research in the Southwest and borderland areas used mixed ethnographic methods to understand better how the intersections of race, ethnicity, legal status, and religion shape Latinx immigrants’ lives, social networks, family structures, parenting, and identity.

During the next two years as a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, she will continue doing intersectional immigration and sociocultural research in the Arizona borderlands. Additionally, she is an affiliated researcher with Arizona State University, the Arizona delegate for the Southwest Oral History Association, and a medico-legal death investigator for the Maricopa County Medical Examiner.

There is so much interesting information in that bio, Bri. I hope you’ll explain some of those terms and talk a little bit more about what you do for work, but I’m so excited to have you. And maybe you can start by introducing U.S. to you, where you’re from originally, and then how you came to do the work that you do today.

BR: Absolutely. Thank you so much for that amazing introduction and I’m also really excited to be here today. A little bit about me, and I guess explaining what that professional bio is. I was born in Türkiye (Turkey) before the Gulf War. And my dad worked for the Department of Defense Education so we moved around a lot in my early life, across the Eastern U.S. and I lived in Germany. I came to Utah when I was a small child, and grew up basically living in the Southwest area, so I’ve lived most of my life in Utah, Nevada, and Arizona.

I worked in immigration, education, in immigration law, and also did advocacy work before I began my graduate studies in anthropology at ASU. And it’s something that’s always interested me. I was especially interested in gender and how gendered experiences impact and shape immigration to the U.S. because of how the women I was encountering in ICE detention centers, trying to get them out and reunited with their families, how their experiences as mothers differed from men who were immigrating or who had been experiencing detention and deportation processes. It became very relevant when the first summer I was doing fieldwork, I had dozens of LDS women across three states who expressed interest in talking about their immigration experiences and how the church intersects with that. So that’s how I came to do what I do.

I’m an ethnographer, which basically means I spend a lot of time in intimate personal contact with a specific community. My community was Latina, immigrant, Mormon mothers in the U.S. Southwest. So I spent three years doing fieldwork on top of my personal experience studying how women had similar interactions or similar experiences and how they were, in almost all cases, very different and unique in how they viewed their immigration experience and as members of the church.

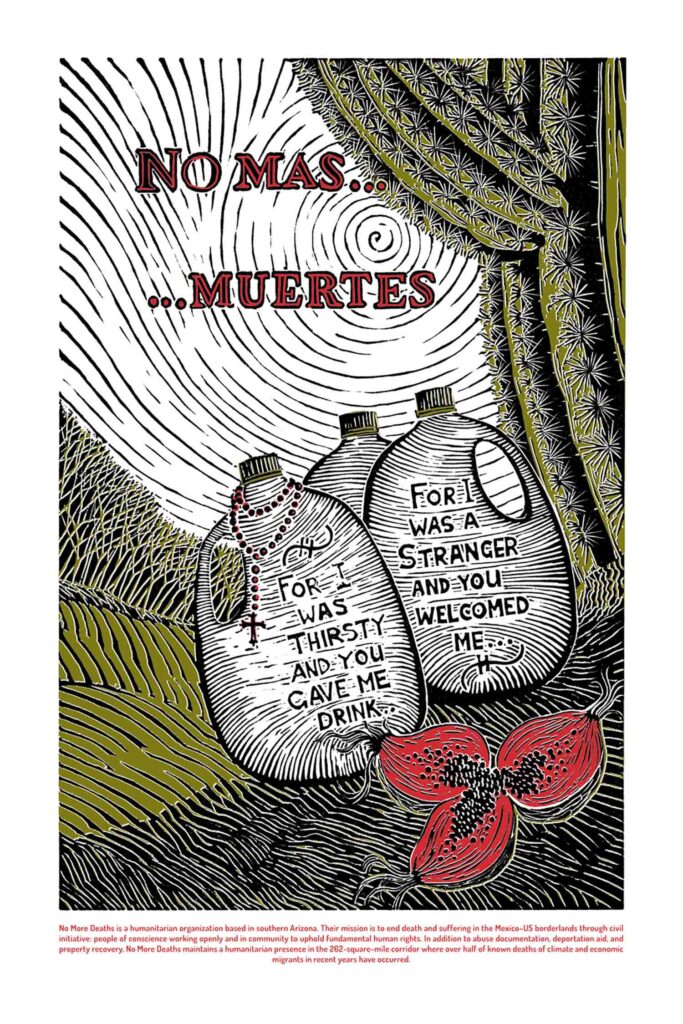

I also do a lot of other things. I’m involved in a lot of activist work in Arizona. I’ve been working with No Más Muertes (No More Deaths) for quite a few years, doing water and food drops along known migrant trails in Arizona. And I am also a medico-legal death investigator, so I work in active homicides in Maricopa County. I’m the only Spanish-speaking medico-legal death investigator, and I do it on a volunteer basis because there is no state money. And what I also specialize in, though, is migrants. So repatriating people who have passed away crossing the border, or people who have been living as undocumented immigrants in Maricopa County, finding out who they are and repatriating them back to their families in Latin America. So I do a lot of embassy work and I do a lot of missing persons work. That’s what I’ve been doing on a volunteer basis for almost two years.

AA: Wow. I’m guessing that people who are immigrating are really at risk of violence. I just know I’ve studied in other contexts that people in refugee and immigrant situations can be completely invisible. And maybe if they’re here without documentation, people don’t really prioritize investigating their deaths or investigating what happened to them. They can just fall through the cracks and be lost. Is that true? Is that what you find?

BR: I would say it’s more than true. Something that I speak about in my work a lot is that I consider myself an immigration scholar across the lifespan, and that extends into mistreatment and the indignities that happen after death. Death is, in my opinion, still a business and a product of capitalism in the way governments and societies treat people in death based on how they valued them in life. And so, if you think about the way immigrants in general, but especially if you are a non-European immigrant, and the way Latino populations specifically are racialized as “illegal”, as “criminal”, that treatment extends into death. It extends into how hard law enforcement or border patrol is willing to investigate the circumstances of someone’s death, and in the willingness of embassies and agents of the state to provide funding for DNA testing to make sure we have the right person that we’re sending home. And how we prioritize families in other countries who are waiting for answers. So, I would say the injustice extends far beyond what I even imagined as someone who studies immigration in birth, and how people make decisions in families, and then their experiences post-migration. Before I started this work, I hadn’t thought about death, and then I was exposed to every horrific thing you can imagine and how the injustice extends there.

So, yeah, it’s a very unique experience and I try very hard to understand in some ways the privilege that it is to understand more about the world and how our world works in fortunate and unfortunate ways. But it’s also a lot of secondhand trauma to realize there’s very little I can do about it except what I’m doing. It does sustain my drive and passion for social justice in all walks of life. Again, immigration across the lifespan, including understanding the conditions of why people migrate, which was a big part of my work, my motivations for doing my PhD work.

AA: Oh, hats off to you, Bri. I’m so inspired by what you’re choosing to do with your life, with your time on this earth. That’s beautiful, beautiful and important work. And it does seem like so few people are doing it, even hearing you talk about food and water drops on migrant trails. I just really respect you and I’m grateful for you.

BR: Thank you.

governments and societies treat people in death based on how they valued them in life

AA: So let’s dive into some of this content. And actually I was going to start off by asking you what the reasons are for people to migrate. I know I’ve had experiences with people I know in Latin America immigrating to the United States because they joined the church somewhere in Latin America, and they’re wanting to come specifically to this region of the U.S. to have a community of Latter-day Saints. But if you could start U.S. off by telling us, is there a typical immigration story for these people that you’re working with?

BR: I want listeners to understand the context of the study and understand that I’m not trying to make a monolith of experience in my answers. I interviewed over 70 women between 2018 and 2021 living in Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and California, most of whom were living in Arizona, which is a unique sociopolitical context because of the COVID pandemic. But I did have over 250 women volunteer or sign up to be contacted to participate, but as anyone might know, there’s no way I could interview that many people. But I did use the data from 69 of them for this analysis, so this is where a lot of my answers are going to be coming from. And I do want to make sure listeners know that when you’re doing an ethnographic project, you need to interview at least 25 to 30 people to “saturate” your findings, which means we can confidently say this is a common experience if we’re finding patterns, if that makes sense. I did double that because of the demand to participate, but also because I knew, unfortunately, that there would be pushback from inside and outside the church, like these experiences might be seen as a one-off or like that’s just one person who had this experience with a bad apple, right? And I really wanted to make sure that my findings could be saturated or well established enough to say, no, these are things that I can confidently say are happening and have been happening and will continue to happen unless we have these conversations. So I just wanted to give that background to answer your question about if there is a typical immigration story.

I do want to start off by saying, as you and many others who’ve studied U.S. history or Latin American history may know, the U.S. has had a huge impact in creating the conditions for migration from Latin America. And what I mean by that is involving themselves and funding guerrilla movements that interrupt the democratic processes like fair elections in these countries, wanting to have a stakehold in agricultural production or resource production. And so, in many countries that I have visited, like Colombia, Argentina, Guatemala, Mexico, the U.S. government has been depleting and destabilizing the ability for people to make a safe living. And so that impacts Latina LDS women from the get-go, right? They’re living as the products of the history that our country has had a huge hand in creating.

And so the women I spoke to, most of them ranged from their late 20s to early 70s, so a lot of these women had lived through civil wars. Especially in Central America or in Chile and Argentina where they had different dictatorships and revolutions. And so when joining the church the main factor was not to immigrate. But because a lot of the missionaries in these countries were white Americans, it created a social network that allowed new members or pioneer members, people who had been the first members in their areas to have a pathway, to have sponsorship to come to the U.S. The church and religious groups as a whole serve as an entity of power outside of state agents. So basically the shared belief in something, in this case the LDS belief, unites people and it unites their resources and networks. So a lot of women I interviewed were able to have former missionaries or mission presidents or people that they had met who had come from the U.S. connect them with lawyers who were LDS, who were using their resources and expertise.

But another huge way, that is a little taboo to talk about, is that a lot of white missionaries married women that they met in Latin America. So you have a marriage market that’s created by that and a power dynamic. A lot of women I talked to, I would say at least a dozen of the women I interviewed who were married to white men had met these men in the mission field. Either when they were missionaries or the men had approached them and been like, “Can I write you a letter?” So you have a big fiancé visa or family connection there.

I wouldn’t say there’s a typical one other than the sense that social networks in the church facilitate or make the difficult immigration process easier. Nowadays, as immigration laws have become very difficult to navigate, especially since the Trump administration, and the government’s basically trying to get rid of what’s called “chain migration”. Which is like if I came here on a fiancé visa and I married and I got my green card. You used to be able to get a green card after having a visa between six months to a year depending on your country of origin. After a couple of years, you could petition to bring family members over. And that’s how a lot of women and their families were able to enter with authorization, even if they overstayed their visas and became undocumented. Or that was a pathway for women to just be able to live with authorization from the get-go.

AA: So what do immigrants report when they arrive in the U.S.?

BR: In my experience, about 60+ percent of the women I interviewed were not members when they arrived in the U.S. But my study was unique in the sense that I don’t know of that many other studies that look at women’s membership across the migration process. So about 35% were members, born in the church, and then immigrated.

AA: So when you say members, we’re referring to members of the LDS church.

BR: Yes. Born in the covenant, as many people might say. So I think that that shaped a lot of people’s experiences. And what I mean by that is that for many women who had been a member of a different religion, identified as Catholic or Protestant or something else pre-migration, they maybe did not have a built-in support network. I mean, there are ethnic enclaves, and what that means is that if I interview a woman from Honduras, for example, one woman I interviewed moved to Southern California to a neighborhood where there are a lot of Central Americans and other Hondureñas. And that’s a safety net, right? A lot of literature talks about ethnic enclaves as safety nets. While you’re adjusting to the U.S., you have other people from similar backgrounds to help you find work, housing, maybe eat some food and have music that’s familiar to what you grew up with. And it makes the adjustment, I don’t want to say less traumatizing, but it allows a buffer. That you have some type of support network. Women who were already members in the Church had a built-in support network, oftentimes from beginning the process and making the decision to migrate and then coming in and having a built-in support network.

And that was a stark difference that I saw between women that came depending solely on ethnic enclaves and maybe some extended family or kin they had in the general area, being like “I’m moving to California because there’s lots of Hondureños” or “I have a cousin that lives there.” That’s how other groups are making these decisions, right? Mormons are making the decision to come to Utah or come to other places that have high Church membership on top of ethnic enclaves. And so many women would tell me, like one woman, Maria Dolores, she’s from Ecuador. Her ex-husband was from El Salvador and they were already members before they came. So the minute they crossed the border they had cousins and ward members and a bishop who had all set up the structure for them to stay in someone’s guest room. They were able to find jobs within a couple of weeks because of networks within the Spanish-speaking congregation. And they had a close relationship with the bishop who was also from El Salvador. And so the husband and the bishop had some cultural connections and that rapport allowed them to access more resources while they were getting on their feet. So that’s kind of one example, that if you weren’t Mormon when you migrated, yes you still had support, but it wasn’t as strong.

AA: Okay, that makes sense. So, you’ve talked so far about missionaries. And I can speak from my own experience, I was actually a missionary in Chile for the Church. And I mean, this is hitting close to home for me too, because I do have very, very dear friends in Chile that I love very much and some of them actually have come to Utah and don’t live far away from me right now. So I’ve seen this firsthand. And I do know that so many missionaries do develop a lot of love, genuine love for the people. And so that’s definitely part of this equation. And then, like you said, relationships and even marriages come from missionary work. And I know the Church does, at least in their values, talk a lot about the siblinghood of all human beings and that we’re all children of God. So that’s definitely in LDS theology, and so I do want to make sure that we’ve established that there is so much good and genuine love. And on the other hand, I know that these immigrants who come to the U.S. do experience racism also, and so I do want to add to this narrative that there is some really problematic racism even in LDS history and theology. So let’s talk about that a little bit too.

BR: Absolutely. And just a side note, I served my mission in Taiwan. And I realize those are different contexts, but I am a hundred percent glad that you mentioned that. And I relate to that because it’s a very complicated and nuanced relationship. You’re in a position of power as a missionary, you have this badge of authority, and you’re encouraged to speak with that. And you’re also encouraged to have genuine love and compassion for everyone you meet. And so I think a lot of these relationships and how things progress, like people migrating or how people sustain relationships in the Church, is problematic if we think about neo-colonization efforts and the overall purpose of missionary work and how American nationalism is rooted in that. But also, as a 19-23 year-old, if you grew up in the Church, I don’t think you’re taught to actively think about that. And a lot of the love and compassion you’re developing is really real. And a lot of times it’s the first time that you’ve had to think outside of yourself and about others for a long period of time. So I just want to comment on that in that both of these things exist: the neo-colonization, the racism enmeshed in the theology, and also missionary and cultural practices are real.

And I also think that people’s perceptions of how they’re loving and fellowshipping is also very real. And I think a lot of times those two things coexisting are oversimplified in and outside of LDS spaces. And how we perceive living and experiencing religion. So I just want to make that note of that, and I love that you brought that up, because I think it ties directly to the origins of LDS racism, and what I often call benevolent racism, which is like, I’m serving, loving, living, laughing, but the racism is also there. It’s enmeshed in a lot of those power dynamics and relationships as well.

So, the way I try to conceptualize or explain to folks who have never been LDS or don’t really have a concept of LDS doctrine is that I would always argue that Christianity, and if you’re looking at the Bible, which Mormonism is based off of, we are fulfilling biblical prophecy and we are adding to what’s already in the Bible. The Bible is already based on hierarchies because of race, ethnicity, and background. And the Book of Mormon is an extension of that, which is in-groups and out-groups. And I think something that is unique about the LDS church origins is that Mormonism was meant to be a fulfillment of Jesus’s vision of unity and a utopian-like society that would welcome all who wanted to hear the gospel. So while there were other religions like Seventh Day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses that came out of this religious movement in the early 1800s, Mormonism was, at least according to Paul Reeve and other scholars that I’ve read, was one of the first religions that was actually racially integrated. A lot of religious practices were for men only, which was true of some rights in Mormonism for a long time, but women were allowed to join and fellowship. But most of those religions in the eastern U.S. stayed relatively white and European and were even split along ethnic lines. The Irish Christians stayed together, the German Christians stayed together. And Joseph Smith’s vision of saving people of color was a motivator to allow people of other races to join. And there was a lot of pushback from LDS members and also outsiders due to that because of white supremacy and racial views of purity and acceptability at that time.

And so you also have that plus the theology of Mormonism, which talks about two groups, the Nephites and the Lamanites, and their skin color being a differentiation in “righteousness and worthiness”. And there’s a lot of scholars that have talked about Lamanite identity, such as Farina King, Moroni Benally, Angelo Baca, Ignacio Garcia, Hōkūlani Aikau, Daniel Hernandez, and many others. And so I recommend looking at their work because they are coming from Latine or Pacifica or indigenous backgrounds of how this use of “Lamanite” has impacted their experience and the legacies of that.

But what I mean to say is that race and hierarchy and power have always existed in Mormonism, especially as an extension from Christianity overall. And so a lot of pushback I get sometimes is a lot of colorblind attitudes that exist, not just in the LDS church, but I would argue that’s present everywhere, especially in this political landscape in the U.S. right now. Like “I don’t see color” or “that’s in the past and it doesn’t matter”. But it very much does matter. Because as my study showed, this is very much affecting a lot of people’s experiences week to week, day to day. And while the overt narratives that some would deem as racist are not as commonplace as they were in maybe the 70s and 80s, it’s still there. It’s still fresh. I think in this past General Conference, Dallin H. Oaks or someone said we need to be unified. The most important part of our identity is that we’re Mormon, and little pushes here and there that try to de-center the very real experiences of race and class and gender that impact and shape people’s lives, even in the church. So the origins are there and they continue to permeate lived experiences today. And I saw a lot of that in my case study.

I’m serving, loving, living, laughing, but the racism is also there. It’s enmeshed in a lot of those power dynamics…

AA: Well, let’s dive into one of the facets of this racism and talk about the history of interracial marriage within the LDS church. And I want to say, too, you talked about Joseph Smith and his vision of unity, but that’s kind of complicated by the passages in the Book of Mormon that very explicitly equate sin with dark skin. So you have both in the very origins. And then you have Brigham Young who really leaned in hard to the racism and took it in a different direction than Smith did. But, like you said, let’s go into interracial marriage because I think this is a really important lens through which to see race. And I know this is what you encounter a ton in your research.

BR: Yes. Something I do want to say that I didn’t say earlier, I apologize, is that people like Bruce R. McConkie who served as a top leader in the LDS church, for those who may not know, there was a lot of differentiating along race. The Black church members couldn’t have full rights until 1978. If you were Black there was this “seed of Cain” ideology that impacted white leaders’ beliefs. This wasn’t just LDS, this extends into a lot of Christian group belief systems. Being Black was seen as almost irredeemable. And that race and hierarchy was innate as part of God’s plan. And there was a belief that Black folks could not be saved or redeemed as equals to white members.

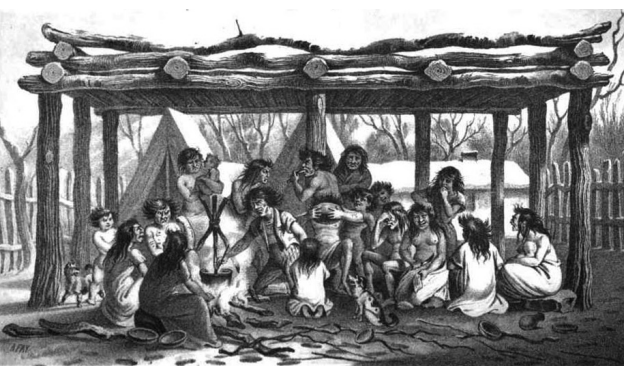

However, people of “Lamanite” heritage, so Pacifica, indigenous, and Latin American origin folks could be saved if they received the gospel. And this is important when we’re thinking about interracial marriage because a lot of the early interracial marriage that happened in the church, that was condoned by the church, was through marrying indigenous women. And through marrying Latin American women and “whitening” them through marriage, your children would be born whiter. And historian Andrés Reséndez talks about this in his book called The Other Slavery and it’s about indigenous enslavement in the United States. And I think something important to point out is that Utah was the only territory and state in the United States that practiced the enslavement of indigenous people.

AA: I did not know that. That’s horrifying.

BR: Yes. A lot of people focus on Utah being denied statehood because of polygamy, which was very true. But another reason the Republican Party wanted to deny statehood to Utah was because they believed Mormons practiced what Andrés Reséndez calls the “twin pillars of barbarism”, one of which was polygamy and the other one was slavery. And a large practice that Brigham Young condoned that leaders who talked about interracial marriage later on rescinded, or maybe glossed over, was the violence that indigenous folks in the Utah and Mexican territories experienced. Because there were Mexican-origin slave traders who would capture and enslave indigenous women and children and try to sell them. And Brigham Young, in these racialized hierarchies, if you’re thinking about saving people, he saw this as an opportunity to literally “save” enslaved indigenous folks. And they would bring women and children into the household as indentured servants. They didn’t want to call it slavery, but some did actually practice enslavement. And they would intermarry.

And I think if we’re talking about terms like consent, I have a hard time believing any of this was consensual. Those were the first origins of a lot of interracial marriage. And people like Lindsay Hansen Park and other scholars have podcasts about Brigham Young’s relationship with Black membership. And the origin of when Black folks who had originally been allowed to join the church ended up losing full fellowship rights, and how intermarriage, like Black men marrying White women, interplays with this. So I highly recommend her podcast. And other scholars I can tell you about later who talk in depth about this.

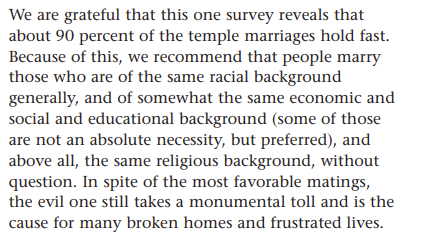

But from my study, thinking about the way Utah participated in the enslavement of indigenous folks, and how what I would call forced intermarriage happened as a saving mechanism impacted a lot of Latina women, and how families thought about interracial marriage. And so that was a lot of the origin of the first interracial marriages between “Lamanite” groups and white Mormons. Because the church was targeted for their racial inclusivity, for polygamy, for indigenous enslavement, all of these things that were considered barbaric and inappropriate in white nationalist America, the church had a lot of rebranding to do. And after suffering, as we know, a lot of exclusion and being forced to move, which I would argue was a natural consequence of a lot of the choices that leaders made, especially under Joseph Smith and Brigham Young’s leadership. You then start to hear narratives in the 60s and 70s, even up until the 80s and 90s, discouraging interracial relationships. And you even have Boyd K. Packer in 1977, the year before the priesthood ban was lifted, saying “We’ve always counseled church members to marry within their race. So Mexicans marry Mexicans, Japanese marry Japanese, Caucasians marry Caucasians, and so forth.” So while that has been taken out of a lot of handbooks, that was really only recently.

AA: That was, I have to throw in here, that was explicitly taught to me when I was a kid. I don’t know if it was to you, I’m a little bit older than you are, but that was taught to me by multiple people when I was growing up in the church. And I do have to say, we all absorb the racist environment that we grow up in and we can’t escape the water we swim in, but I do remember the first time someone said that to me specifically I felt just heat going through my body. And I’m really grateful that for whatever reason, something in me knew that that was not true and I felt really angry. So I’m not saying that I was impervious to absorbing racial ideology or racist ideologies, we all do, but I’m grateful that I never bought that. I don’t blame if people do just accept as children the messages that adults tell them. I feel like that was in the handbook until very recently, wasn’t it Bri? They said bishops were supposed to counsel their members to not marry outside their race until so recently.

BR: Even in my life, although my parents have never commented on what race of a person I’m dating, that wasn’t part of the conversation. It was more focused on heteronormativity and sexual purity than anything else. It is something I saw and it’s something that came up in my study a lot. Over a third of the women I interviewed had been married to white men or were married to white men. And this narrative of “you’re too different culturally” or “it’s best to marry within your culture” was very prominent. So the benevolent racism of like “we’re just trying to help you because of cultural clashes” was a way to cover up for racism.

AA: Yeah, absolutely. Let’s dig into that. What did you see? What were some common features of these interracial marriages that you studied specifically? Especially those between a white Mormon man and a Latina woman.

BR: Well, that’s exclusively what I studied. My study was only with women because of the gender power dynamics, and me being single and unmarried, while I did have interactions with men, I had no desire to have these deeply intimate conversations with men because of how that can be viewed in our LDS sexual politics. Unfortunately, me being a single woman and perceived as heterosexual in a lot of situations can create some awkward social interaction. So I only worked with women. I would have loved to get the perspective of white men and hopefully in the future I can interview men. So the perspectives I’m sharing are solely from the women I interviewed. And while every situation was different, I would say that men initiated most of these relationships, which I think is important for what I’m going to talk about later. But men initiated these relationships, whether they were missionaries, “lock your heart”, who had solicited women to write them. Or a lot of women described their husbands who they met on their missions as coming back for them after the mission was over, arranging to come see them. Or whether it was in an LDS singles ward. Men were initiating these relationships almost all the time. I didn’t hear an instance in which a woman was going after a man, which may reflect the deeper gendered politics of dating in a conservative religion. That’s what I saw a lot.

I saw a lot of women reporting that, yes, their parents may have had some concerns about cultural differences, but they were mostly concerned that they didn’t want their daughters to be victims of racism or ethnocentric treatment. But because most of these men had either served Spanish-speaking missions or had lived prolonged periods of time with Spanish speakers, I think there was only maybe one or two husbands that didn’t speak Spanish at all but grew up in highly Latine areas, parents expressed that they were okay with it, because the most important thing was that the man was LDS. If their families were LDS, that was a priority, marrying within the faith. Or that they were a hard worker, that they respected the culture, that they were going to take care of their daughters, because even if the women had parents who weren’t LDS, or maybe their mom was LDS but their dad was not religious, there were still these very gendered ideas that you need a man to take care of you and you need a man to be responsible. Especially as many women were first generation students or hadn’t had the opportunity to go to school beyond primary school. That was a lot of what was reported to me, like, “My parents may have had some concerns but it wasn’t about race, it was about, can this man provide? And if their parents were Mormon, can they share in the same religion as me? Can they take me to the temple?” essentially.

For white families, it’s a stark contrast. All of the women I talked to reported the racism, aggression, or varying levels of coldness and isolation that they felt based on race or based on perceptions of legal status when entering into marriages with their white husbands. So that was really stark. Women almost never shared about things like “Was it about me being able to be a good wife or being able to be a good mother, or what was I as an individual person offering this family?” The concern was about race and the concern was, “Are you marrying my son for papers?” Women were undocumented or the perception that because they were Latina, that they were “illegal”. There was a racialized assumption that you must be living without documentation in the U.S. So that was really hard for women because they felt like who they were as people, all of these individual nuances about them, were not considered. It was about what they looked like and a piece of paper that they had or didn’t have.

AA: Mm-hmm. So they were concerned that they were going to use their sons to get citizenship in the U.S. This is what you were referring to earlier when you said this is why it’s critical to know that it was not the women that were pursuing these men, it was the men that were pursuing the women, right?

BR: Yes. So that’s completely the opposite of what happened. That assumption was not true at all. And especially it was very interesting for women that lived with their in-laws, whether it was California or Utah or Arizona. The interactions specifically between white mothers-in-law and sisters-in-law and Latina women, this benevolent racism and power dynamic was especially stark. It was very prominent because of the gender dynamics that exist in LDS culture. While white fathers-in-law did do racist things and had their own situations of micro- and macro-aggressions happening, it was the mothers-in-law and white women in the family that were perpetuating a lot of the long-term isolation and discriminatory behavior towards women. Especially when Latina women became mothers and were having biracial or multiracial children that they were trying to raise bilingual across cultures.

AA: Yeah, what did this look like? What did this discrimination look like? What did they report to you in their real experience?

BR: A lot of the women reported that because the majority of white women members in the U.S. come from a middle or high income demographic background, socioeconomic background, and a lot of them grew up in segregated or racially homogenous areas. So a lot of white women had never had to interact with immigrant or non-white women like Latinas on a level of equality. What I’m saying is what Latina women said in our interviews. I think I have one instance, Lily, who’s Mexican, said that her mother in-law, when she first met her when they got engaged, said, “Oh, I had a Mexican friend once, she used to come over and we would talk.” And then Lily’s husband, Aaron, said, “No, mom, that was the maid. She wasn’t your friend.” And so it was these very weird, uncomfortable and awkward situations that white women had not actively chosen or been put in situations that they were interacting with women of color outside of these stereotypical and perceived notions like immigrant women working in service industries, like as maids and domestic workers. And because of that, a lot of Latina women I interviewed described these uncomfortable and very demoralizing, degrading interactions with white mothers-in-law.

Another mom told me that she received some pajamas with llamas on them for Christmas, and this was after years of a lot of racialized remarks from her parents-in-law. And she just said to her mother in-law “Thank you for these pajamas.” And the mother in-law said to her, “Yeah, I know llamas are from your country.” And she said, “I’m Mexican, llamas come from Peru.” And her mother in-law responded, “Well, all of those are the same thing.” And so, for this mom, Veronica, she described like, “Okay, I’ve been married into this family for almost a decade and my mother-in-law is giving me this gift. But you still don’t know the difference between Mexico and Peru?”

AA: She’s making no effort.

white women had not actively chosen or been put in situations that they were interacting with women of color

BR: Yeah, you don’t care to understand my culture or my background and you see us all as the same. And then we have even more stark interactions between white women in their families and outside of it. One woman, Natalia, she’s from Argentina, and she’s also Black and Argentine, so she’s biracial herself. Her white sisters-in-law refused to come to the wedding because of her Blackness and because she was undocumented and people thought she’s marrying Jacob, her husband, to get papers.

AA: And they wouldn’t even come to the wedding.

BR: They wouldn’t come to the wedding.

AA: That’s so heartbreaking.

BR: And she reported years later after she had a son, and the mother-in-law wants to see the grandson, and after she was able to adjust her status she reported “My sister-in-law wants to be my best friend now.” What changed? The only thing that changed is that she had “proven” herself by starting a master’s degree program, giving them a grandchild, and also adjusting her papers. Those are some different varying examples, right? You have day to day comments that are laced with racism and it’s very apparent white women’s lack of experience. And then you have the long-term like “You’ve been in my family for years and I still don’t know anything about your culture and I refuse to learn.” And then you have more overt forms of violence like “I refuse to interact with you because of legal status or perceptions of race.”

Then we have Rosa, and she’s indigenous Mexican. She describes herself as having very strong, prominent indigenous features. She married her white husband and they have a 22 year old now, so they’ve been married about 24-25 years. And she told me during our interview that they were at a family dinner with her in-laws one night and her white sister-in-law had mentioned at the table she had been dating a Black member of the church, a Black man. And her father-in-law at the table, in front of everyone, said, “I wouldn’t be comfortable with this relationship continuing.” And Rosa said at that moment, “What do you mean? No other races?” And then that’s when her father-in-law said, “Didn’t your husband tell you the talk we had with him?” Again, we see here that “it’s better not to marry outside of different cultures.” That’s what they had told Rosa’s husband before they got married. And of course they got married anyway.

But Rosa said that that dinner was a starting point for really understanding and seeing the racism and xenophobia happening in her family. And that her mother-in-law, especially when Trump was running for president, everyone in that family was identified as politically conservative and posting about how Mexicans shouldn’t be in the country and all these things. Anti-immigrant rhetoric and reposting things that Trump had said that were very degrading towards Mexican-origin people. And then her mother-in-law would show up at their house and come play with the kids and bring them gifts like it was nothing. And it really started to, in her words, destroy the relationship. Because all of a sudden she had this realization, “I’ve been in this family for almost 20 years and my in-laws didn’t want me here. I’m the mother of their grandchildren, so of course they love me in that way, but they don’t love who I am and they don’t love people who look like me.” I had a lot of emotional interviews like that.

And when I present on this, the most pushback I get is from white LDS women. Because when I share these experiences, there’s a very visceral reaction of like, “I need to defend myself” or “I need to show that I’m not racist and I’m not doing these things.” But the data is the data. All of the women married to white men are having these very gendered and racialized interactions with white Mormon women. And sometimes for decades. These prolonged interactions where they’re feeling like it’s not that you don’t have the opportunity to understand me or know me, it’s that you don’t want to and you’re reducing me to my immigrant status or to my race or ethnic background.

AA: And you’re saying that when you present this that you find that white Mormon women, instead of being humble about it and wanting to be introspective and interrogate their attitudes, that they react defensively. And, I mean, nobody wants to be labeled a “racist”. But is this a situation where we’re seeing the proverbial white tears where the women are like, “How dare you say this about me? I love all God’s children!” Or what does that look like?

BR: Yeah, I think it’s very uncomfortable, and I think you and I have talked about this before, and numerous Black feminist scholars and Latinx scholars have discussed how white Americans specifically view racism as a moral failing. Which is right, but there is a focus on it being an individual problem and “decision” to be racist rather than it being rooted in the structure of our very society. For example I have a term I use called the “white familial gaze”, and it’s based off of the “white gaze”, which Black and ethnic studies scholars have talked about the white gaze as people of color or people of the global majority are often subjected to surveillance from white citizens and from white people. Whether they’re cops or agents of the state or just existing in a grocery store. I hear a lot, “Well, you’re never really alone because a white person is always watching you and watching what you do.”

And I use this concept when talking about the family. The white gaze is part of our structure as an American society. Monitoring, surveying, and policing non-white bodies has been part of the history of this country since its inception. That was built into the Constitution, of who was considered fully human, who was considered a citizen, and who wasn’t. And then when you talk about the family, the white familial gaze in this case is the way that white women, who are products of this structural racism, are policing, surveying, and criticizing the Latina, Afro-Latina, or indigenous women who have married into their families. So that violence that people of color are experiencing in the public sphere now has become a more intimate violence that they’re experiencing in the family.

Now I say all that because when I’m presenting this, a lot of white women aren’t hearing that. They aren’t hearing about how this is a structural problem. They’re hearing, “Well, I’m supposed to love all of God’s children, and you’re telling me that I’m not because I’m racist, and that’s a moral failing.” People hear, “You did a racism. You did something. This action was racist.” And they equate it to “I’m a bad person. You’re calling me as a person racist and that’s not accurate and I’m offended. I’m offended by that and I need to let you know here’s all the X,Y,Z things that I do to serve people of color or immigrants in the church here. I have a friend who comes over sometimes who’s Mexican.” There’s all these caveats that women specifically feel the need to use. Or I hear a lot of my friends say the whole “I have a black friend” thing. That’s what I equate it to. They’re bringing up these instances in which they have a lot of times very superficial interactions with people as “proof” that they’re not racist. And they’re completely missing the point that this is structural.

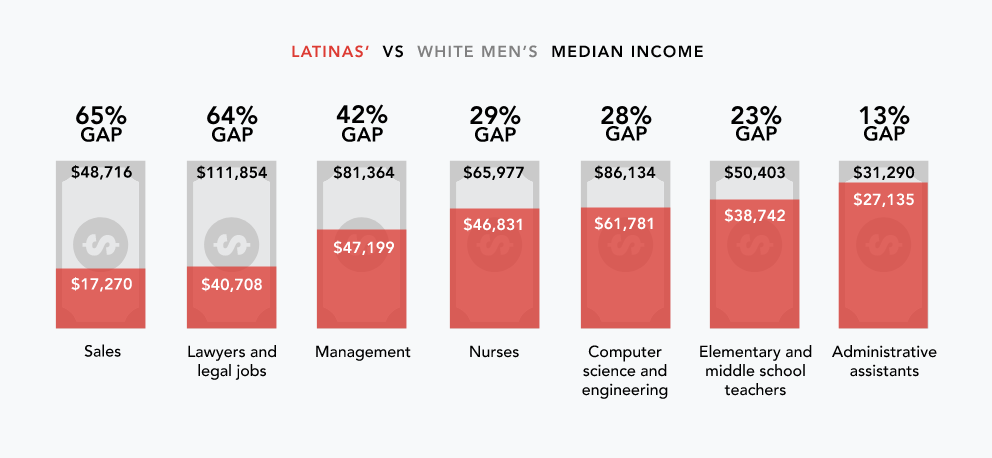

As white people in this country, as white women in this country, who are benefiting from white supremacy, we are always going to be active recipients of what white nationalism is doing for us. And while many of us can try, I know people like you and I are doing our best to practice anti-racism and to hold ourselves accountable, I think that there’s a deep discomfort with interrogating the fact that as living in white female bodies, we can’t escape the structural racism that benefits us. And when you bring up religion and being all God’s children, and you have this colorblind narrative that’s being pushed, and a correlated history that talks about race in a romanticized way, taking out the violence, it’s very hard for women to have these conversations. Because if we start talking about structural racism and how that impacts socioeconomic mobility, how it affects our ideals as Mormons, women being stay-at-home mothers, that’s not possible for most immigrant families. Latina women, if they’re citizens, make 50 to 60 cents per the white man’s one dollar. Undocumented women make even less than that. Latino men experience a downward mobilization when they come to the U.S. because unlike Latina women, who are often able to find stable work in domestic care or cleaning houses or a lot of these things that white women were stereotyping, Latino men are subject to a more unstable job market. And so their income is also less.

So if you’re thinking about the LDS gender ideal of women staying at home, that’s often not possible for immigrant families because they need two incomes to make a white man’s dollar. It doesn’t mean white families don’t struggle, right? But that’s what a lot of white women are hearing when I talk about structural inequity. When I talk about racial inequity that’s built into the very frames of the house that is the U.S. nation-state. So it’s very difficult for people, especially women in the church who are maybe more progressive or feminist, who understand the gender dynamics and inequality that women face as women in the church, to also think about race and to think about their part in that. It’s very hard for them.

AA: Very hard. Well, hopefully people listening, if you can think of someone who might benefit from hearing this conversation, pass the episode along. This is really, really important inner work to do. As kind of a tangent, I did think it was important that you just mentioned, I guess, a patriarchal norm that is oppressive to Latino families too. Could we say maybe a couple more words about that pressure to have the single income family where the man protects, provides, and presides. That’s what the Mormon ideal family is, and that’s not feasible. So this is a hardship where patriarchy then intersects with racism.

BR: Yeah, absolutely. I can tell you just anecdotally most active LDS families that I know who are within my age range, millennial mid-twenties to late-thirties, both the man and the woman work to some degree. Now, a lot of women, and this was true among some of the Latina immigrant women I interviewed, a lot of women until recent years – I would say the culture is changing – have been discouraged from seeking more education than was necessary. And that’s something I was told growing up by Young Women’s leaders, by Stake Presidency leaders, people who would come and talk at Girls Camp. Yes, being educated is important, but it’s so you can support your husband. It’s so if something happens to your husband, if he becomes unable to physically work, if he passes away, you have a way to provide for your family. It was never like the way it was marketed to men, which is that this is to help you develop as a person and reach your potential and your divine spirituality so you can serve others.

The patriarchal nature of the Church and the way we view gender absolutely affects everyone who is considered female. So a lot of women experience this regardless. But then you also have the economic disadvantages, and the racial disadvantages, and the discrimination because of legal status. A triple marginalization that Latina Mormon women are facing on top of being a woman in the Church. There have been other studies showing that Latina first generation immigrants or 1.5, which means you came as a child to the U.S. but you grew up mostly in a U.S. cultural context, that’s 1.5 generation. That women in other religious groups like Catholic or Evangelical and their children, and specifically their daughters, are more likely to graduate high school and more likely to complete a bachelor’s degree or even higher education like a master’s and to be working full time and making more money than their immigrant parents. But in my study, Latina Mormon women experienced a downward mobilization because of the pressure to get married, because of the pressure to prioritize family, which I would argue if you’re a member of the church, you already have in your mind the need to prioritize family. And then a lot of women in their cultural backgrounds, family is the most important. So it’s not a matter of not valuing family. It’s a matter of physically being in the house and physically reproducing these ideas about where you belong.

And so a lot of women I interviewed had graduated from high school, especially if they were 1.5 generation and came here as a child. And some of them, I’d say three or four had been able to get bachelor’s degrees or beyond, like a master’s degree. Two women I interviewed have master’s degrees. But by and far, a lot of them did not complete school even though they had the chance to. Especially women who are married to white men, because white in-laws were giving a narrative like “I was a stay at home mom, we lived off a single income. This is what you should be doing. To listen to the prophets, to listen to the leaders.” And on the other hand, women are experiencing the narrative from their families, “We sacrificed so much for you to come here. This is your opportunity to get an education. Why aren’t you doing it?” And so that’s another thing that existed in interracial relationships.

And even among women who had married U.S.-born Latino men, so Chicanos or Tejanos, there was this embodied ideal that men need to have a certain role in the home and women can have leadership and have education, but only to the point in which it serves you being a good wife and mother. So a lot of women never finished their degrees or they faced immense pressure from their in-laws, especially white in-laws, to live an ideal that was not possible for a lot of them. And so for the women that did finish their masters, it was not without a lot of conflict within their families. It was not seen as a good thing to get more education.

there was this embodied ideal that…women can have leadership and have education, but only to the point in which it serves you being a good wife and mother

AA: Wow. Well, my last question that I’d like to talk about is, how can this culture change?

BR: I talk a lot in the article about, first of all, men. I know that there might be some feminist scholars or feminists who don’t agree with me with this comment, but I will say there’s a lot of academic literature emphasizing this: that people with intersections of privilege and power need to use their voice to intervene with the oppression and the violence that we’re seeing. So my recommendation, in a lot of my work, is that white men, and men in general in LDS spaces, in highly conservative or religious spaces as well, not just Mormon but on a broader scale, need to intervene with the sexist, and racist, and classist, and anti-immigrant things that they’re seeing.

A huge problem that I saw in my work was the way that men somehow lived this dual experience of like, “I’m a leader, I have authority, I have priesthood authority, and I’m meant to lead this home.” But when they’re seeing their wives or other women in the family be treated disrespectfully based on the case of race or gender, there was not a lot of pushback from men. I did have some instances where Latina women described their white husbands saying something to the family, but women were often left to battle long-term discrimination and prejudice and isolation on their own. And I do think that men need to intervene. And the constant choice of men to not intervene, to not say anything because they’re men and they hold this position, and women are just dealing with this among themselves. There was a lot of that attitude, if that makes sense. Like, “But that’s my mom” or “That’s my sister.” And it’s like, well, that’s your wife. And a lot of women were like, “How can you prioritize marriage and obey the proclamation to the family? But you’re letting me get bullied at every opportunity and suffer these microaggressions and macroaggressions.” And men would not intervene.

And so my number one recommendation is that if there are men listening who want to know how they can make a difference, you need to say something. Because whether you want to admit it or not, if you are living as a man in the Mormon societal structure, your opinion is going to have more weight because your gender is given more weight and respect in social circles.

Secondly, white women are a huge bridge between this. And so I always recommend to white women, let’s start discussing your testimony of the religion as something different and separate from your testimony of the institution of Mormonism. We can recognize that you have an individual testimony, as we talked about earlier, the pure love and service and things that you can be doing because of your love for Jesus Christ or your love for other people as something separate from the historical violence and marginalization that’s happened in the institution. But we often get the message that the institution and Jesus are one in the same. So if you criticize one, you’re degrading your good standing with the other.

And white women have a very important role to play in this. They exist as people who are being actively oppressed in this power structure but who also carry a lot of privilege to make a difference. There were so many instances that women reported to me and that I also witnessed in my field work where white women could have been the bridge to solving misunderstandings, to building a longer table instead of cutting Latina women’s voices off. But because there’s such a scarcity mentality for women’s voices to be heard within the institution, I think that it’s almost like a game of musical chairs. Women are grasping for whatever opportunities they have to be heard and to be taken seriously. And often if you are at a double or triple marginalization in U.S. society, the way Latina immigrant women often are, they often get left behind because white women are not thinking outside of themselves and their own personal problems.

And again, as I mentioned many times already, it’s deeply painful for them to sit in the space of like, I am oppressed because of gender, but I’m also an oppressor in the ways I’m actively choosing to not engage with difficult subjects or engage with my own bias and how I’m treating other women. I’ve heard so many stories of white women not sharing the kitchen space in the church with Latina women, or all these micro/macro aggressions I’ve talked to you about like, is it hard to Google? Is it hard for you to Google and find out that there’s different countries? Is it hard for you to sit down and have a conversation with your daughter-in-law or with a woman in your ward? Is it really that hard in a religion that’s so focused on service to find a translator for your activity? It does require effort, and I’m not going to minimize the fact that women are doing all of the unpaid labor in the church. Men are doing it in sanctified leadership positions, but women are doing the unrecognized, unpaid, unvalidated labor. And I don’t want to give the impression that I’m glorifying that women are doing this. I don’t think it’s fair and I don’t think it’s right. But white women do have it easier. I am going to be very blunt and say it in that way. It doesn’t mean your problems are less. Your problems just aren’t amplified because of race or immigration status.

So recognizing that and using that and bartering that in your positions of power, and in your spheres of influence, is a really great way to start having honest reciprocal discussions about inequity and about bias and about the structure of institutional racism. But it starts with being okay with being uncomfortable. And I think that because white women in particular do not have to engage with that discomfort, they have the privilege of not having to engage with that discomfort, it often isn’t addressed.

AA: I couldn’t agree more. I’m so grateful for all of that. I just want to thank you so much, Dr. Brittany Romanello, thank you so much for being here today.

BR: Thank you.

I am oppressed because of gender,

but I’m also an oppressor in how I’m treating other women.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!