“One day you’ll learn that feelings aren’t facts. And also, that equality isn’t a feeling.”

On today’s episode, we’re going to be exploring this concept of the feminist awakening with three extraordinary guests–Monica Rodgers, Shelbey Neil, and an Anonymous Contributor–who help us unpack the trance of patriarchy, the challenges of a new perspective, and the need to confront our former beliefs.

Our Guests

Monica Rodgers

Monica Rodgers (she/her) is a tireless advocate for the full actualization of women, inspiring women everywhere that saying “YES to the MESS” is the missing link to self-love and personal awakening. Through her podcast and group coaching programs, Monica guides women through their inner evolution, from trance to transcendence, revealing the toxic myths of social conditioning and self-doubt. Monica is a Mother, a Beloved Life Partner, a Certified Co-active Coach, Sacred Feminine Archetype Practitioner, Host of The Revelation Project Podcast, and she’s the Author of the upcoming: Book of Revelation.

Learn more by visit jointherevelation.com.

Shelbey Neil (she/her) hails from the mountains of Utah but has lived in swamps of New Orleans for the past 5.5 years. She likes dipping her toes into many interesting subjects and moving quickly onto the next—but feminism has sucked her in for a total immersion. Her life motto is horrendously cheesy, but you really do miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.

Shelbey Neil

PART ONE.

Disrupting The Patriarchal Trance Of Unworthiness

Monica Rodgers

As a child, I loved to play dress-up with my younger brother Joe. I still have a photograph of the two of us standing side by side circa mid-1970’s in front of our fireplace in our childhood home in Michigan. I am dressed in my father’s red blazer and tie, grinning wildly with my arm slung over my brother’s shoulder and my chest puffed out with pride. My brother’s eyes are squinting in merriment as he stands beside me, looking his most alluring in my mother’s gauzy, dusty-blue negligee while he teeters precariously on a pair of her high-heeled shoes. We are approximately five and six years old.

On another Sunday afternoon shortly after this photo was taken, I bounded down the stairs dressed in a similar fashion to impress my parents and their friends using the last stair as my platform: “One day when I grow up, I’ll be The President of The United States of America!” I declared to the cocktail-wielding guests.

As a little girl, I believed I could be anything. I was confident, creative, embodied, and fully self-expressed. The response was an uproar of patronizing and laughter.

After a few moments, the room hushed in volume and murmured remarks followed:

“Isn’t she precious!” and “she’s got spirit though, I’ll give her that!”

But it was actually my brother— sitting on the floor in front of in his jaunty yellow construction hat playing with his trucks—who ultimately and innocently broke the devastating news. “You can’t be President, silly! You’re a girl!”

Although I was still very young, this moment is etched in time as the first of many messages that would ultimately cast a cumulative spell regarding my sense of self-worth.

Until then, the many messages that tried to relegate me to my place in the world as a girl hadn’t managed to permeate my psyche, but on this day, for whatever reason, those words from my brother made their mark, wounding me with a first painful cut.

I didn’t scoff in response to my brother’s comment, nor did it spark what would later develop as a quick-tempered resolve to show them all how wrong they were. Instead, upon learning that there truly had never before been a female president, I went quiet.

It was as if the fact that I didn’t know this made me into a silly little fool, further proving the ineptness of my sex. It was one of my first powerful experiences of dissociation from an uncomfortable reality in which I felt I had no power, and even worse, was unworthy of having any.

As soon as this fact settled within me, it grew until I became enraged at the sheer injustice of it. The hot sting of shame began to settle within me, cutting as I encountered other places, books, professions, fashions, clubs, and sports where females were relegated to certain roles, omitted from stories, or barred from entering or participating due to what I came to believe was the lowly status of my gender.

I believed I could be anything…The response was an uproar of patronizing and laughter.

I understood, then, that the world was different for me and my people—but the most shocking thing of all was that no one around me seemed the least bit phased by the news. But of the many derogatory cultural messages consistently micro-dosed to me in the earliest years of my life at home and school, none were as captivating or as destructive as those from my very own church.

Sitting between my siblings and parents in a pew each Sunday, I would often feel my skin crawl and my face grow hot as the priest read passages and stories from the Bible.

This holy book seemed to sanction and seal my permanent and pitiful station as a daughter of Eve, the first woman who it seemed had single-handedly caused the downfall of humanity by eating an apple from the tree of knowledge in the garden of Eden thereby cementing the fate of myself and my sisters as permanently wanton, sinful, and in need of constant guidance and oversight.

I understood these teachings as having come from “the word of God” himself, and in many religions, I would learn, it was only priests or men who were worthy of communing with God. It wasn’t until I was in my late 30’s that I would learn that historically, there had once been a reference to God’s other half and that societies had once revered the Goddess. Before Roman rule, women were seen in her image, honored for their ability to bring new life into the world, and celebrated for their embodied connection to Mother Earth and her cycles.

We never learned about the Goddess Archetype in school, or anywhere else. The feminine face of the divine was hidden from us, as was the overreaching patriarchal system of oppression and male supremacy that causes undue harm forcing girls and boys to conform to gender roles that do incalculable damage. Gender roles that project the message that to be feminine is to be weak, and that to be female is to be inferior and incomplete.

These messages were both spoken and covert and sent confusing distress signals which taxed my already dysregulated nervous system. As I went from childhood to pubescent adolescence, the distress signals intensified as my developing body brought new sources of input and hyper-awareness. The pressure to conform to impossible beauty standards was compounded by the sudden sexualization of my body from the outside world. My outer appearance seemed to dictate whether I would one day be married and have children, and this was somehow mysteriously linked to any future happiness I might hope to expect. This beauty myth immersed me in a persistent and unconscious obsession with my appearance and pitted me in competition with other girls my age as I vied for position and rank, equating my value through outside consensus and allowing others to determine my worth through their judgment of me.

Simultaneously, the denigration of any seemingly “feminine” traits was omnipresent, inferring that to be feminine was to be weak, unreliable, and frivolous. This denigration only increased my sense of dis-ease and upset.

The growing pressure left me feeling trapped, alone, and terminally insufficient. I was caught in the impossible double-bind of too much or not enough, but—without the language or knowledge to make sense of what I was experiencing—I opted for the strategy of being what they wanted: pretty, pleasing, and polite.

Inside, I felt like a pressure cooker without a release valve. I imagine a silent implosion as my psyche finally gave way to fracturing in parallel with what would become my tragic, but useful habit of self-abandonment. Betraying myself in favor of the approval and validation from others—disassociation at will—a talent that did not bode well for future decision making nor my ability to confidently navigate the world. In abandoning my body, so too was I disconnecting from my inner GPS, my true north, and my way-finding device.

Like death by a thousand tiny papercuts, each message made its mark, leaving my body less and less inhabitable.

As the second sex, fashioned from the rib of Adam, my people represented the descendants of decisions made by the queen-mother of bad choices. In my growing despair, I remember hating Eve as an extension of myself and looking to my mother and the women around me as allies and witnesses to this terrible reality. To my horror, I realized that even though these adult women were standing, facing the front with their eyes wide open, they were fast asleep, in a trance-like state in the pews surrounding me.

It occurred to me then that they had vacated themselves. Evacuating their bodies to leave a representative in their place so that they no longer had to endure the emotional pain of being embodied in a world hellbent on shaming, blaming, undermining, and making women the scapegoat in the enforcement of male supremacy.

A trance is an interesting, albeit apt, term that describes a half-conscious state characterized by an absence of response to external stimuli. In Middle English the word hails from Old French transir, “to depart”, to fall into trance, and from Latin, the word, transire, “to go across.”

When I started to numb, I separated from my body and in doing so, departed from my body’s innate wisdom to escape the pain of feeling judged, blamed, misunderstood, and less than.

It’s as if these messages, both overt and explicit, work as a form of cumulative neurological programming that slowly but effectively erodes our sense of self-worth. If these messages go uninterrupted, they lay the foundation upon which is built a baseline of evidence inevitably formulating a world we then internalize as true.

By the time most girls have reached adolescence, they have disassociated from the pain of hundreds and thousands of microaggressions. In essence, we vacate the place which causes us the most pain by refusing to inhabit what is an emotionally uninhabitable place: our bodies.

We no longer respond to “external stimuli” because we have learned that to go numb, is to survive. To separate is to escape from our bodies, and so, we “go across”—up into our heads—and instead of living from the body’s innate wisdom, the place that contains our access to our feminine power through intuition, instinct, emotion, and inner knowing, we instead hyper masculinize ourselves in a world of doing, logic, and pragmatism leaving us in a trance of unworthiness, compliant and compromised.

I am reminded of one of my favorite cartoons from MGM as I was growing up called Tom and Jerry. Tom is a big tomcat, who is always trying to get the little mouse, Jerry. But the little mouse always outsmarts him, and in most episodes always has the upper hand making Tom the butt of most jokes. In one episode, Tom has been put into a hypnotic trance and is sleep-walking while Jerry the mouse takes advantage of his compromised state, putting things in his path to bridge the gaps between one place to another, making him step from heights, only to save him at the last minute from falling to his demise; and yet nothing seems to wake Tom, no matter what.

At some point, I could see the parallel, that boys were treated as one species and girls another, and each with their own set of rules for roles. Just like the cartoon, everything was positioned in such a way that the girls were like Tom—sleepwalking in a trance, unaware of the fact that everything was set up to keep them compromised, compliant, and asleep. And in case it’s not obvious, patriarchy is Jerry, silently sabotaging women yet simultaneously placing them on pedestals, making sure to save them when they fall. A man is always there to save an entranced woman—a father, a husband, a priest or a male god.

By the time most girls have reached adolescence, they have disassociated from the pain of hundreds and thousands of microaggressions

Symptoms of this disembodied trance become entrenched in patterns of dis-ease, dis-connection, and disempowerment including a myriad of sophisticated coping mechanisms that look “normal” in our world.

Normalizing a culture that consistently prioritizes and amplifies the values of the masculine over the feminine is akin to the trauma of living in a toxic relationship with its gaslighting and projection. This makes for a powerful cocktail of disempowerment, inner misogyny, and self-loathing in girls who grow up to become women who not only don’t believe in their own value but then unconsciously repeat the devastating generational cycle with their own children.

However, once a woman has returned to the body and recovered from this dissociative habit, recovering her sense of self, and reclaiming her right to fully express herself, she is able to realize that her former state was anything but normal.

When I began using the term “the trance,” women could not at first see it, and seemed disconnected from its weight or relevance in relation to their own life. However, as I described its many forms, it’s spell-like nature becomes painfully clear and, once realized, becomes almost impossible to unsee.

Most women today can relate to putting everyone else’s happiness and well-being before their own. So too can they relate to minimizing one’s self, and shrinking, or staying small and uncomplicated so as not to appear needy or burdensome. These and many more are all symptoms of the trance.

Girls and women learn to self-sacrifice as a badge of honor. We contort ourselves in a myriad of ways to appear sufficient and to keep time with a patriarchal pace that encourages us to achieve at the expense of our own well-being. We make our lives look perfect on the outside while hiding deep feelings of confusion, unfulfillment, and exhaustion on the inside, and we often feel guilty and ungrateful for feeling trapped in lives that we “should” be grateful for. Most women secretly search for something to fill the void, not realizing that the source of our pain is hiding in plain sight within an invisible system of oppression and control that’s been eroding our sense of self without our awareness for the majority of our existence.

When a girl can not feel safe in her own body, and continually gets the message that she is only good for some things deemed and dictated “worthy” by men, there comes a time when she too eventually rejects the worthiness of even her most basic needs, translating the external stimuli into the incessant inner question “what is wrong with me?” which then becomes the tragic internalized unconscious belief:

“I am not worthy.”

The trance also impacts high-achieving women who are perpetually plagued by self-doubt, chronic over-apologizing, a compulsive need to seek permission or outside validation and have little or no confidence when it comes to claiming their talents and gifts. While most women believe that their struggle is personal, it’s far more universal.

In her book, Patriarchy Stress Disorder, author Dr. Valerie Rein posits another theory:

After working with hundreds of high-achieving women she discovered that the issues women all struggle with are not just personal—but in fact, rooted in the ancestral and collective trauma experienced by living in the patriarchal world for millennia. In Patriarchy Stress Disorder, Dr. Rein describes how this trauma creates an invisible inner prison, that holds women back from stepping into the full power of authentic presence, unbridled joy, outrageous success, freedom, and fulfillment.

In short, the trance of unworthiness is an unconscious disassociated state caused by unrealized trauma. Women in a patriarchal society are unable to fully function or fully express themselves because they are deeply absorbed in the false belief that they are undeserving and lacking value due to their contextualized experience. This can only be revealed, healed, and integrated through the body when we are able to see and process what has formerly been hidden from us.

As a young child, there was a period of time when I lived my life in total alignment with the truth of who I was. I knew that I was special and valuable for who I was, and I believed in myself with my whole heart. I was fully embodied and intoxicated by the possibility that I could be anything I desired, without limitation. I was not defined by my gender, or limited by nature. I could feel the world and its paradoxical answers through my body, and in its stillness I knew that I, too, was divine.

That child still exists and continues to call out to be heard and remembered. But as I grew into an adult woman with all of my strivings and achievements, I never stopped long enough to listen to what it was she wanted from me, and I had never allowed myself to feel the grief that comes from realizing that it wasn’t my fault. That as a little girl, I had done the best I could to survive. I had been consumed with lies that kept me hustling for my worth and busking for crumbs of love, believing that I could one day find the person or thing that could fill the void inside of me. But as a wise person once said, you can never get enough of the wrong thing. What my inner child wanted was for me to return to myself, and in doing so, come back for her. She wanted me to start taking care of her, to stop abandoning her, and to tell her that there was never anything wrong with her and that I love her, just the way she is.

The body knows the way and has a beautiful way of showing us when we have strayed too far from home. Mine became as sick as the secrets I believed I was hiding about my own inadequacies and shortcomings. For years I had been hiding my flaws while holding it all together for everyone, and in doing so, I was resisting the very thing that would continue persisting until I let it fall apart.

And so, I let it fall apart, I stopped hiding behind masks of perfection and having it all handled and, in doing so, was given the opportunity to experience myself from a different perspective as I descended into a dark night of the soul where I discovered my own humanity, and an imperfect me, who was perfectly capable, worthy and beautiful, just the way she was. There was nothing for me to numb, hide, or prove. In the mess of my humanity, I was divine, flaws and all.

The body is our gateway to liberation and, when we women allow things to fall apart that are not working, what we come to see is that the world does not work in the way that it’s meant to until we are full of ourselves, and by full of ourselves I mean attending to our needs and attuning to ourselves as the first step to tapping into the source of our endless well of being. That by re-sourcing ourselves first, we then become a resource for others, able to give not from our lack, but from our overflow.

I was resisting the very thing that would continue persisting until I let it fall apart.

Today I believe that masculine and feminine energies exist in all of us, and none is more relevant or important than the other. To create is to integrate and honor both and to flow between them, and regardless of what we have been taught, women are natural creators. We make things work, and without us, the world is far-sighted, nearsighted, and lopsided. When women are tuned in, fully embodied, and fully present in our lives, we naturally make things happen for ourselves and everyone around us.

Our unworthiness and inadequacy is the great lie that keeps the structure of patriarchy in place. When we hold it all together, fearful of looking messy and imperfect, we become complicit in our own oppression. We don’t have to hold it all together, nor do we need to tolerate being excluded from positions of leadership in churches, governments, or anywhere else. To be awakened to the lies of our own inadequacy is to finally recognize the trance for what it is, and to realize that the world is deeply out of balance without the fully expressed voices, ideas, and energies of women.

This is “The Sophia Century”, a term coined by Lynne Twist as the century of wisdom.

As the feminine returns, so too does the healthy masculine rise, and as women work in co-partnership with awakened men, we re-solve what’s been ailing our world. To disrupt the trance is to allow the world as we have known it to fall apart so that something better can be reborn in its place. It’s time for women to reinhabit ourselves, to love ourselves, and remember the truth of who we are as powerful, sovereign beings that are the wayshowers of this world.

In my mind’s eye, I still see the little girl I was, dressed in her father’s jacket and exclaiming her vision to be president. Across the years, I whisper to her, “no”, I proclaim to her that she does not need to clothe herself in the masculine to find her power, nor does she need to abandon herself, ever again. Her way will flow to her and through her as she remains fully rooted in her body, knowing that she is worthy, exactly as she is. She is sovereignly embodied, and whether another soul ever votes for her or not, she presides over her own life, in service to her own soul.

She is more than enough and never ever too much.

PART TWO.

My Breaking Down Patriarchy Glasses

Anonymous

In the middle of Covid lockdown, around February of 2021, I started following the Breaking Down Patriarchy podcast. I’m not sure how I found it, but I’m guessing someone I know on Instagram re-posted something or other, and I clicked. I was hooked from the first listen. Copies of the podcast’s essential feminist texts took over my personal library, and I became a podcast “guest” (at least remotely, since I usually listened in my car), and I commented on every episode.

As I’ve listened, I’ve gained a new understanding of the word “patriarchy.” There is a depth and breadth to it I didn’t realize before. Listening to the podcast has given me a new perspective. It’s like I’ve put on a pair of Breaking Down Patriarchy glasses, and I can’t take them off. I now see that our approach to understanding history and religion; the way we organize power structures in society; and the prescriptive gender roles we enforce on one another, are all based in patriarchal influence. I see the way feminism tries to illuminate and change disparities that patriarchy causes. I also often see patriarchal influences in my conversations with others, and have discovered that sometimes “patriarchy” is a word people are uncomfortable discussing. But perhaps the most striking thing I see through my new glasses is myself.

I’ll give you a few examples.

Not long ago, I went to a dermatology appointment. Now, my dermatologist and I have enjoyed chatting outside the normal doctor-patient dialogue in the past, and I was excited to share what I had been reading in Riane Eisler’s book, The Chalice and the Blade. It was my favorite book from season one of this podcast, so I took it with me to the appointment. It was an old edition with an earth-colored image of a goddess artifact imposed upon a bright red background. The doctor noticed it right away when she came in.

“What are you reading?” she asked.

“Oh,” I said, “it’s this amazing book about patriarchy and feminism…”

“Feminism.”

“Yes, it’s amazing, it talks about…”

She interrupted. “You know I’m from another country, right? I have a perspective you may not have regarding women and opportunity. Women in this country have more opportunity than any other in the world.”

Her usually friendly tone had changed. She curtly informed me that American women didn’t know how good we have it, and if we don’t take opportunity when it comes, it’s because we’re expecting government hand-outs.

My mind raced as I tried to form a reply. I think I blurted out something like, “This book is about more than that; it is about identity, about political systems, about economics, about history and archaeology, and illustrates the reason we have so much power disparity in our world today…”

She nodded, and that was the end of it.

After that appointment, through my new “‘Breaking Down Patriarchy” glasses, I realized that the words “feminism” and “patriarchy” sometimes elicit strong opinions, that they can shut doors rather than open them. Riane Eisler’s description of patriarchy as a domination system came to mind, and I considered using that word as an ice breaker into conversations about patriarchy in the future.

Let’s do another example though. Before picking up those patriarchy glasses, I had regularly gone to lunch with some older women I knew from my church. We would meet monthly to reconnect and see how each of us was doing. Usually our conversations centered on kids, housekeeping, good movies or an interesting book. At this time, I was the only person with children still at home; the other women had grown children and grandchildren.

One woman began the conversation by talking about how tired she felt from getting up early to make breakfast in bed for her husband. Another shared that she felt quite lonely since her husband was still traveling for work while she filled her time at home with crafts and decorating her house. We talked about the importance of motherhood, the way it has been the focus of our church’s teachings, the way the phrase “fulfill the purpose of your creation” had been used to convince us of the importance of homemaking in combination with child rearing.

They asked me about my children, emphasizing how much I should relish my time with them, “Because,” they said, “when they grow up, life pretty much stops.”

Then someone remarked, “The church seemed a lot more interested in me when I was pregnant or having babies. Now that I’m older, they don’t seem to care as much about what I do. They don’t talk about my purpose anymore.”

Her usually friendly tone had changed. She curtly informed me that American women didn’t know how good we have it

But the next remark made me pause.

“Have you seen the movie My Octopus Teacher?” she asked. “Remember, after the octopus laid her eggs, she turned white and died?”

Everyone laughed, and someone said, “That’s pretty dramatic, but yeah, it’s kind of like that.”

I was stunned. To me, these were talented and intelligent women. I knew that they struggled with loneliness, and I often wondered why they didn’t pursue education or get a job outside of their homes. It struck me how deeply they had accepted their identity as being homemakers, even after their children had grown. They mentioned feeling secondary to their husbands’ jobs, and how vulnerable they felt since they couldn’t financially support themselves. They spoke of their love of being mothers. “But kids grow up,” one of my friends lamented. “And then what?”

I remembered the movie as I continued listening to the Breaking Down Patriarchy podcast. It was a powerful image – the limp, white body of the octopus in the mouths of its predators as it floated away. I realized there could be another future for my friends, and for me. I texted them and asked if they would like to participate in a book club, hoping that reading some of the essential feminist texts from the podcast could help them. They were interested until I mentioned I had a bunch of books discussing patriarchy and feminism. After that, I got no response.

So if you’re still with me, let’s do one last example, and this is an old one. This was a conversation I had a few years ago, and it left me unsettled for quite a while, but it’s only now—with my new perspective and understanding of patriarchy—that I finally understand why.

It happened after my husband had worked as a pastor for our church for over a decade. Initially he ran our local congregation, eventually changing positions to overseeing up to eight different congregations in four different counties. This was volunteer work; he had a full-time job as well. His time and energy were consumed with church and his employment.

I stayed home with my three young children and cared for them on my own most of the time. Since our extended families lived in different states, I didn’t have a lot of help. Finances were tight as we lived on one income, so paying babysitters wasn’t an option (though I occasionally traded babysitting with other mothers). I experienced intense loneliness and hopelessness and fought with postpartum depression. As the pastor’s wife I felt so much pressure to be supportive and quiet – to sacrifice my needs so my husband could serve the church. The last thing I wanted to do was ask him to be home more to help. His job was so important to the church. My job (supporting him as I raised my children) felt small in comparison.

When my husband finally finished his work for the church, an upper-level director came from our church’s headquarters to appoint someone to fill the now empty position. During his visit, the director invited us to dinner, along with some other regional leaders. That included my husband’s immediate supervisor and his wife, who I will call Beth.

During the dinner, Beth addressed the group and began talking about a pastor in another area:

“His wife,” she said, “has blue hair. She acts erratically and is not a good example of a pastor’s wife. What should we do about her?”

The conversation turned abruptly to the idea that so many men in the church could move up the leadership ladder if only they had wives who knew how to sacrifice, who were a good “helpmeet,” who quietly lived the exemplary life of wife, mother, and home-maker.

Because of my own lonely experience as I tried to support my husband for so many years, my heart broke. I saw myself in this stranger with blue hair. I asked if anyone had gotten to know her, had talked with her, or listened to her.

But my concerns were dismissed. Getting to know her wasn’t the point, apparently. Her experiences, whatever they might be, were second to the importance of her husband’s church leadership.

Back then I didn’t have the language of feminism and patriarchy. I knew I felt upset by the conversation, but I couldn’t put my finger on why. But since listening to Breaking Down Patriarchy, I understand better. I wish I would have known how to speak up for the woman with the blue hair. I wish I would have known how to speak up for myself. I would have liked to have said something like, “What does it say about us that we can talk so negatively about this woman? Isn’t her happiness as important as her husband’s success at church? Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we emphasized the importance of nurturing to men as much as women? If we emphasized that men’s purpose is to be fathers and husbands over moving up a church-corporate ladder? What if we let women have more of a voice in the church, showing that women and men can be leaders and nurturers? What would that do for our families?”

To me, it is easy to see the way patriarchy impacted my church experience and identity, the way it impacts women. But as my husband and I have reviewed his time working for the church, he has mentioned how lonely he felt, how he missed his kids and being their father during that time. He felt, and feels, disconnected from our children, and now says, “Those are years I can’t get back.” Because of his experience, I’ve tried to use my Breaking Down Patriarchy glasses to see the impact patriarchy has on men as well. And let me tell you: it has been illuminating. I see patriarchy punishing men constantly now. I see it in arguments about family and paternity leave. I see it when men want to teach preschool and are discouraged since “men just don’t do that.” But most of all I have seen it in the way people in my community approach raising boys.

A few months ago, I chatted with a counselor at our local elementary school about the parenting styles she saw in the community. Her report wasn’t promising:

“I would call it authoritarian. Dominating,” she told me. “The kids are expected to jump when the parents say jump, and there is shame involved if that doesn’t happen. The boys get it the worst.”

Conversations I’ve had with other parents seem to confirm this, as I hear things like,

“Boys are just rougher.”

“They are troublemakers. They tend to lie more than girls.”

“Boys need a heavier hand when they do things wrong.”

Her experiences, whatever they might be, were second to the importance of her husband’s church leadership.

I thought about the word “dominating” that the school counselor used as she talked about parenting. Riane Eisler wrote about dominator culture in the home, with a hierarchy of men over women, leading to domination over children. The detrimental effect of dominator parenting is clear in books like Raising Cain: Protecting the Emotional Life of Boys by Dan Kindlon, PhD., and For Your Own Good by Alice Miller. I’ve seen it as I’ve watched documentaries about men in prison and the trauma they suffer because they were raised without nurturing. To put it really simply though: patriarchy doesn’t encourage boys to have their emotional needs met, and because of this boys often fail to learn the skills they need to keep healthy relationships.

Basically, this system isn’t working well for any of us, or at least very few of us.

Now, I know many women perceive patriarchy as favoring men—and there’s validity to that perspective—but reading the feminist texts has broadened my understanding of the breadth and depth of patriarchy beyond this. Patriarchy and domination include the power disparity between men and women, but patriarchy spills over into class, into race, into economics, and government, and well…everything.

I’ve tried taking my Breaking Down Patriarchy glasses off as I look at my life, giving in to the temptation to go back to accepting myself as a woman under the definition of patriarchy. In a sad way, it feels comfortable and familiar, and sometimes I’m scared to step out of it. But those glasses have illuminated my unhealthy belief that quietly standing behind my husband, sacrificing my talents and opportunities in the name of womanhood, was the right thing to do. I feel sad and embarrassed that I fell for that narrative, but I don’t want to feel small anymore. My identity has changed, and I keep reaching for the glasses to help me see a new way forward.

In my life, I have raised three beautiful children, one of whom has had cancer twice. I was able to be there for him at every moment: when he was sick, when he was scared, when he was left alone by his friends and overwhelmed with his uncertain future. As I have chauffeured kids to all the places they need to be, I’ve listened to my daughter’s hopes and dreams for a PhD, and my youngest son’s worries about meeting friends at his new school. I’ve made birthday cakes and cleaned throw-up. I wouldn’t trade it for the world. When I look through my glasses, I see myself as the goddess in Riane Eisler’s books; a powerful nurturer who holds a chalice for those around me, lifting them up and supporting their well-being.

But I also see that white, listless, octopus from the conversation with the church women. I can’t help it. I sometimes feel like I’m drifting and forgotten. I’ve had to work hard to come to grips with that. And when my kids go off on their own, who will I be? I have been so wrapped up in home-making that laundry and cleaning are a huge part of my identity. Do I shrivel up like an octopus and die when they leave home?

Short answer: I don’t think so.

I’ve been applying for masters programs at local universities. I’m ready to realize my own value in the world. Patriarchy doesn’t make it easy, of course—the responses from academics when I tell them I have been at home with my kids for the past twenty years have been comments like “I didn’t realize women still did that,” and “oh, well, maybe starting over would be an option.” That’s fine. Whatever they say, it isn’t going to stop me anymore.

Besides, we’ve got more important things to address, like the patriarchy entrenched in our economic systems; in the way we treat mother earth; in oligarchies and powerful corporate greed.

Recently I’ve seen social media posts blaring the words “smash the patriarchy,” and “dude, the patriarchy messed up my life, and yours too.” I appreciate them, but to truly break down patriarchy we’re going to need more than catchy memes. We’re going to need to put on our glasses and get to work. We’re going to need to speak up with understanding, learning from the words of women who have done the work before us. We’ll need to stand in our confidence and discover the power we have in our own lives.

PART THREE.

I Take Back Everything I Said in 2015

Shelbey Neil

“I love being a woman. That word, woman, can mean pretty different things to every person. All the women out there probably have their own ideas. The one idea I can’t stand, though, is that women are inferior.

And—despite what is paraded on the internet—the people who have been telling me this are feminist women.

For some reason, feminists are simultaneously the greatest advocates of women’s rights and the greatest advocates of women’s inferiority. They assert that women are powerful, smart, and capable. But they do it in the context of the following message: ‘Men don’t think you’re powerful, smart, and capable. You don’t get paid as much. People don’t value your opinion. Your religion doesn’t like you as much as it likes its men. People don’t expect you to do anything except stay home and raise kids. Isn’t it HORRIBLE how they treat us??’ Women have been the first (and only) ones to tell me that other people think I suck because of my gender.

As an innocent child, I knew I could do anything I wanted, because that’s what my parents made me feel like. I realize that makes me pretty darn lucky. And I’m sure not all parents do that. I am a woman who feels and has always felt that anything I want to do is completely in my power.”

Those foregoing passages were written by a woman in her early twenties, recently married and even more recently pregnant. I imagine hearing those words will make more than a few feminists bristle at the blatant ignorance mixed with privilege and good fortune. Do you have a few choice words you’d like to say to that woman?

Do you mind if I go first? Seeing as that woman . . . was me. It has only been 6 years, but I have a few words I’d like to say to myself.

Dearest Shelbey,

You mention it, but you don’t fully understand that your upbringing is extremely unique. You and your sisters were treated the exact same as your older brother—every. single. thing. that was expected of him was expected of you. Do you know why that is? I have a secret: your parents are closeted feminists. They have a lot of traditional beliefs and behaviors but, as far as the actual raising of you and your siblings goes, they’ve created an alternate universe where you believe that you can really do just about anything.

But what you don’t know is that other parents aren’t feminists. I heard today from an Anglo-Indian man that in his home country it’s normal for fathers to make their daughters take “virginity tests” to prove to their future husbands (who suffer no such test) that the girls are virginally pure for them. You don’t know that around the world girls are restricted from going to school. Or that they have to drop out because they’ve missed too many days while they were on their periods. Even girls in your own country suffer from period poverty. You don’t know that your very own peers are being told that their education doesn’t matter because their husband will be the one with the job.

You don’t realize that around the world, women aren’t free like you have been to decide what “being a woman” means to them. For roughly 810 women every day, being female means dying in childbirth from preventable causes. For others, it means a rigid box of nice, happy, helpful, and pretty—no matter what. For still others it means having to have sex with their partner whenever he wants it, because he doesn’t just want it: he needs it. Your privileges of time, money, safety, health, education, and heterosexuality free you up for this level of self-determination.

And what you don’t realize yet, is that feminists are the ones you have to thank for almost every single privilege that you have, from being able to earn your own money to being able to spout your opinions so freely. So take that bitterness out of your mouth when you say, “feminist.” That word is sacred.

But I’m curious at what else you’ll say.

“During my senior year of college, I realized that what I wanted to do more than anything was to be a full-time volunteer for the rest of my life. I wanted to give my everything—my body, heart, mind, and soul—and to receive absolutely NO monetary compensation or worldly recognition for my dedication. You know where this is going: I wanted to be a mother.

‘Just’ a mother. One who ‘stays at home’ (what a nice phrase to make the hardest job in the world sound easier). I wanted to create, carry, deliver, and raise human spirits and try to teach them EVERYTHING they need to know to be successful in life. I really don’t understand what in the world could be more important than that. And I really don’t understand what about that doesn’t appeal to feminists. After all, ‘The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world.’

Talk about gender inequality.”

Well, Shelbey, in a cruel twist of irony you will soon discover that being a parent truly is the hardest job in the world—or at least the hardest one you’ll ever have. And it is really, really important. You’re absolutely right.

But I know you inside and out, and YOU want to be a mother because you have finally realized you can’t commit to any career path—though you’ve pre-bragged about so many—so you’ve gone back and adopted the attitude of dead, misogynistic prophets to give you a purpose. Some women really do want to be mothers. Not you. You’re just looking for the safety of certainty. Why else would you voluntarily give up your independence and spontaneous solitude?

I hate to say this, but you’ll also one day regret sacrificing your body. It ain’t as noble as it sounds when you have to live with the effects. And I don’t mean your sexual appeal; you’ve still got it. I mean something more like nearly hemorrhaging and dying in the labor and delivery wing and having to wear a silicone disc inside your vaginal canal for the rest of your life because your organs don’t stay where they’re supposed to. Cute, huh?

You think the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world, but do you think it will only ever be your hand? You claim to be an advocate for fathers—then be one for the father of your children. His hands rock their cradles too. Because as long as that is seen as a mother’s exclusive work, many of the baby girls in those cradles will grow up feeling destined to enter the endless cycle of sacrifice. Where does it end?

…you’ve gone back and adopted the attitude of dead, misogynistic prophets to give you a purpose

Speaking of fathers, 2015 me, why don’t you tell me about your incredible husband. Spoiler alert: in six years you’re still crazy about him, though you eventually figured out how to stop needing his validation for every facet of your existence.

And then I finally met the guy who would one day give me that gift of motherhood. Who will one day slave away at a job just to pay the bills while I get to live out my dream. Who tells me all-too-often that I’m better than him. Who maybe doesn’t worship me in the Phantom of the Opera and Christine kind of way (probably a good thing), but who does love the crap out of me with his huge, kind heart.

You know, you bring up a great point. In the classic arrangement of a working father and stay-at-home mother, the husband’s end of the deal has some downsides. Do you remember a conversation where your husband admitted to you that he had some regrets about not pursuing his dream of becoming a pilot? The conversation came down to a few different points: you were both scared out of your mind of student debt, and you weren’t sure how you could possibly live without him for days at a time (that was actually good foresight for you, because the work of parenting nearly swallowed you whole). But ultimately, in a polite way, you said, “I’m sorry you have this dream but you have to provide for us, so too bad.” You wanted him to hold up his end of the gender bargain.

You live in a patriarchal system, both culturally and nationally. (I know, the word patriarchy triggers eye rolls for you.) Now, most of the downsides of patriarchy fall on the shoulders of women and the LGBTQ+ community, but there are also some real negatives for men. And this is one of them. You married your husband because you loved him, yes, but also because he was willing to fit into a certain slot—that of a financial provider. Do you really think that’s fair to demand of him purely because of his gender? It’s fine to make arrangements for financial dependence between two consenting adults, but does it have to be him? If so, why?

Another downside of patriarchy is that it teaches us that men are hardly able (if at all) to control their basest instincts regarding violence, sexuality, and power. That without women, they would be lazy and given wholly to debauchery (which is heteronormative in addition to sexist, but you’re not ready for that conversation yet). Your husband isn’t like that at all. You may be very lucky with your choice of spouse, but he’s not completely unique. You also believe that no one is doomed unalterably to be any certain way. When men insist that women are better than them, this is what they’re hinting at. Do you really want to be better than your spouse? Or wouldn’t you rather respect him?

You haven’t talked about religion yet, though, and I know that’s important to you. You’ve dedicated your entire life to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“Some women in the LDS (Mormon) Church feel inferior because they are a woman. But again, let me offer a different choice: I feel like a rockstar as an LDS woman. I have never felt more love than when talking to a bishop. I feel so important when I get set apart for a new calling that was hand-picked (by God) for me. The Church leaders make me feel like my miniscule contribution is making a difference.

A lot of the negativity with the Church focuses on the fact that women can’t hold the priesthood and the equivalent leadership/service roles, but can I just remind y’all that I would not have been able to have my most favorite calling in the whole world if I were a man? Does anyone ever talk about that? And don’t you dare give me some crap about how being the secretary of the Young Women’s organization is not as important as being the bishop (or pastor), so it’s not the same thing. There you go again with the feminist-driven inferiority complex. Does the whole argument come down to what your definition of important is?

Do you really want to be better than your spouse? Or wouldn’t you rather respect him?

Shelbey, you’re talking a lot about feelings. One day you’ll learn that feelings aren’t facts. And also, that equality isn’t a feeling.

You ARE right about one thing—it’s not about the importance of different kinds of labor. It’s about being systematically restricted from service and leadership opportunities ONLY because of your gender identity—and being told that’s how God wants it.

I have to disagree that women are just as needed institutionally—a group of 1,000 women would need one man there just to take the sacrament. Although, they DO need you at home providing childcare so that fathers can perform their religious duties.

I know this one will be particularly hard to believe, so let’s take a break from this Christmas Carol-y inner monologue and bring in an expert. This is Dr. Meg Wheatley, specialist in organizational behavior and formerly the Associate Professor of Management at Brigham Young University, your alma mater. She wrote:

“[S]tructure communicates values…. What people learn about themselves and their value to the organization is not what the organization says to them or about them but what they experience while members of that organization. What they experience is structure.

Messages communicated by structure are far more powerful than any statements issued by a [corporation]. . . People can hear that everyone’s contribution is of equal value, but they will not believe it when only certain contributions are recognized in public forums or are rewarded with other, more desirable assignments . . . We need to ask what the present structure of priesthood communicates to both women and men about their abilities and potential . . .

Although theologically we feel secure in stating that God created men and women as equals, structurally we communicate inequality. Women are cited as the backbone of the church and extolled for the many hours of service they contribute. Yet the range of contributions, especially leadership, open to them is quite limited compared to that of men simply because of the priesthood requirement. No matter what church role they serve, women are further circumscribed by organizational rules which require that most decisions be approved by priesthood authority.” (Women and Authority, 1992)

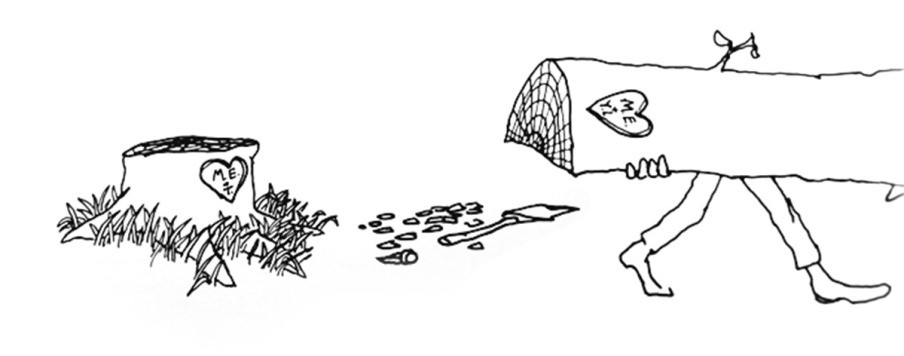

Perhaps this will help you understand, my friend, that you are a sucker for compliments. The compliments gushing out from the pulpit about how incredible you are—are fool’s gold. As Dr. Wheatley put it, structure speaks. Actions speak. Notice that the people praising mothers for their sacrifices aren’t generally lifting a finger to help. You’ve read their talks. They’re not avoiding helping young mothers for lack of awareness of what a mother does (when you cut the labor across traditional lines) —it’s simply because that is her place. How noble that she must figuratively die. Your church leaders are following the plot of The Giving Tree and convincing you to let your children sit on your dead stump. Please start questioning why the tree had to be cut down in the first place. When male leaders praise you for all you are doing, but disappear in the moment of need—be wary. When they insist that they see how you are overwhelmed and overloaded but also insist that it must be women to do this—push back.

You don’t really notice it now, but the discrepancy will become abundantly clear when you move away from Utah to a place where priesthood holders are scarcer. They need priesthood leaders desperately. There you are, faithful for three decades and more than willing to do something besides parenting, unable to fill those untrained, unpaid volunteer positions because of one little thing called gender.

One day, your bishop will be not a grandfatherly figure of eternal wisdom, but about the same age as you. You’ll have experiences that show just how much more he matters to the church organization than you. In fact, his opinion of you determines the ways you’re allowed to serve (which, of course, are already limited compared to men of your same age and faithfulness). You’ll work hard to get back into his good graces just so maybe they’ll let you teach Sunday School again.

All right, closing arguments.

“I just want to put a different voice out there—for the girls who actually feel totally empowered RIGHT NOW because they are women. For the girls who don’t really get what everyone is talking about, because they’ve never had a problem finding a job or achieving their goals. For the girls who don’t understand why being a woman who literally teaches other humans how to eat, walk, talk, read, make friends, do homework, jump rope, play instruments, and so forth is the most undervalued position in the eyes of other women.

For the girls who are pretty much okay just doing what they want to do, because they want to do it. Not because other women made them feel like they had to in order to be worth something. To you girls, who already know your own worth, don’t buy into the backhanded compliments of the feminist agenda. Though, if we’re talking the dictionary definition of feminist, you can’t find a bigger one than me. But you also can’t find a bigger defender of men, either. Because, guess what? Both genders are equally important and loved equally by a perfect, omniscient God.”

You’re right, you truly don’t get what everyone is talking about. You don’t know what it feels like to be denied a job because a male candidate was preferred—thanks to both your feminist foremothers and the fact that you’ve only ever applied for “women’s work.” You don’t know what it’s like to have institutional powers limit you reaching your goals because you’ve never actually striven for anything above your rank and station. You also don’t understand that feminism relies on freeing men from arbitrary cultural rules as well. Intersectional feminism is one of the best ways to empower and defend men, to empower and defend everybody.

You’re right that childcare and unpaid labor are undervalued. In fact, you don’t yet understand just how right you are. When you learn more about history, you’ll realize that it’s patriarchy and capitalism that have stripped caretaking of its economic value while voraciously consuming it to survive. The only reason your husband will be able to do his job is because of the work you do at home—and one day, that idea will change from a tender caress to a slap in the face.

You may not be doing things to impress other women but you are doing them to impress the misogynistic, self-absorbed, over-reactionary God delivered in a small box to you by men. I wish I could say you were acting out of a deep sense of your own worth, but that will come later, because you will change.

See you in six years.

There was never anything wrong with her

I love her, just the way she is.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!