“Becoming fully human is the antidote”

Amy is joined by Levi Murray to explore the damage which patriarchy causes to men, how systems of oppression cultivate emotional immaturity and psychopathy, and discuss the ways we can heal the harms of patriarchy and become more fully ourselves.

Our Guest

Levi Murray

Levi Murray is a native of New Mexico and has been living in Colorado for almost 20 years. Murray works as the community health dentist, practicing in Southern Colorado. He and his wife Barbara have four kids. His hobbies include running and engaging int he work of preaching anti-patriarchal theology, a work he says feels like a necessary part of becoming more fully human.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: One question I sometimes have as I’m doing this work is how to recruit men. Breaking Down Patriarchy is a title that can seem a little scary to some men, and many male friends actually have let me know how wary or defensive, and honestly sometimes even hostile, they can feel when they’re asked to engage on the topic of sexism. I feel that one of my core strengths is my ability to empathize with and see the good in almost any human being, so I tend to approach men gently and reassuringly.

But on the other hand, I have to ask myself, at least in some cases, “Am I going too easy on men?” I want to be hard on systems and soft on people. But in trying to thread that needle in a way that doesn’t scare men away, am I going too soft on the system of patriarchy? Well, one conversation that helped me recently was a conversation with one of my favorite past podcast guests from season three, Levi Murray. In a nutshell, he told me that there is really no reason I should be treating patriarchy with kid gloves, and that one of the reasons for that is because patriarchy actually hurts men so much too. I have been wanting to dive into that topic more deeply, how patriarchy affects men, and as Levi and I conversed, I realized that he had some insights that were completely new to me and totally fascinating. So, I am very excited to welcome back to the podcast, Levi Murray. Welcome, Levi!

Levi Murray: Thank you, Amy. I’m so happy to be back with you and honored to be invited back for another episode to join you and your listeners. Thank you for the invitation to come back.

AA: I’m really excited about this. Like I said, you’ve been on the show before. And on your first episode, you coined the term, at least for me, “anti-patriarchist”, which I have incorporated into my vocabulary. I loved that term. But for listeners who missed your incredible first episode, which was actually on female archetypes in Mexican history, can you tell us a little bit about who you are and how you arrived at the work that you do today?

LM: Yes, thank you. I am a native New Mexican, I’ve been living in Colorado for almost 20 years, and I am a community health dentist practicing in Southern Colorado. I’ve got an amazing family consisting of four kids and an incredible partner named Barbara, who is actually the reason we connected in the first place, so, my gratitude to her for that. My hobbies include preaching anti-patriarchal theology and running, and I started engaging in this work a few years ago really out of necessity in my pursuit of becoming fully human. I think anyone who wants to fully become what we can be as humans has to engage in this work.

AA: Well, that’s fantastic. Hopefully we’ll get to a little bit more about your work later in our conversation, too. And I’ll just point out, I had forgotten that you and I have a lot in common, Levi, because I grew up in Colorado and I’m also a runner. But let’s just dive right into this topic because we’ve got a lot to discuss. And actually, I’m not even going to give you more of an introduction than that. I’d love it for you to just take it away and we’ll talk about stuff in real time as we go.

LM: That sounds great. I’m really excited to talk about hierarchical systems of control and how they impact the hearts and minds of humanity. Before I dive into that, I just wanted to say how I’m such a big fan of your work. And I definitely was not criticizing you when I said to not treat this topic with kid gloves, because I fully understand the dynamic and the position that women like yourself find yourselves in, where if you come on direct, honest to engage the topic, many men will not engage you. It’s kind of a catch-22, where if you don’t treat many men with kid gloves, they won’t listen, and if you do, they don’t get the importance of the topic. So, I completely understand that. I just wanted to name that that’s the thing that I understand, and I really admire the work that you do and the way you navigate that dynamic.

AA: Oh, thank you.

LM: For today, I’d like to invite your listeners to take a wide view of the world and the experiences they’ve had, consider the ideas that we’ll talk about today, and consider how these ideas show up across the spectrum of systems and institutions that they inhabit. From education to religion, business, philanthropy, science, medicine, art, and beyond. The things we’re going to explore today show up in all those arenas. What I’m going to propose to your listeners today is that hierarchical systems of dominance intentionally and systematically malform, stunt, and oppress human development.

So, as your listeners already know, the flavor of our current hierarchy is patriarchy. In patriarchy, males are centered and put in a position of dominance over females. More specifically, a single group of males are put in a position of dominance over all other males and females. I think it’s natural to consider how those in the position of subjugation are harmed by systems of dominance, but it’s much less common to consider what happens to those in the position of dominance. I believe that the reality of patriarchy is that all humans that exist under its ideology and systems are prevented from becoming fully human. Today I’d love to focus our conversation on the ways in which men are impacted by patriarchy.

AA: I can’t wait. Really quickly, one thing I wanted to ask you before you start diving into the data is, I’m really curious how you started thinking about this in this way. Was it from your personal life or through reading about it and actually researching?

LM: Both. A combination of reflecting on my own experiences as I started to understand what patriarchy is and wondering, “How has this impacted me? How have I been socialized by this system in ways that I don’t even understand?” in combination with my educational pursuits of seeking to better understand the dynamics of hierarchies and how these systems impact the earth and all the humans that inhabit it. As I was in the midst of that, I noticed that certain traits and behaviors were consistent, whether it was in the context of a high-demand religious leader, in business or a financial leader, a politician, a media personality or Hollywood portrayal of men, and I also noticed them in men in my circle of friends or family. And like I mentioned, self-reflecting and noticing some of these things in myself as well. In the midst of trying to make sense of all these things, I discovered this fantastic book by clinical psychologist Dr. Lindsay C. Gibson, who recently published Disentangling from Emotionally Immature People, and it is a game changer.

AA: For me, too. I actually just discovered Dr. Gibson’s work on the podcast We Can Do Hard Things. I think it was Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents that was featured, and a lot of my friends and even my siblings have been reading her work. And it’s really mind-opening for me, too. What were your thoughts on this? I hadn’t thought of it in terms of how it related to patriarchy at all.

LM: Well, as I was reading Dr. Gibson’s books about these traits and behaviors of emotionally immature people, specifically in the context of family relationships, I immediately connected the dots between those traits and the traits of these men that I’d been observing who had been heavily socialized by patriarchy. They were a mirror image of each other. I was flabbergasted. And I found it so interesting that we condemn these traits in the context of emotional immaturity, but then we’ll turn around and praise the same traits in politics and religion and business and finance. That parallel is what I’d love to dive into with you.

hierarchical systems of dominance intentionally and systematically malform, stunt, and oppress human development

AA: Take it away. I’m so excited.

LM: So, when I say patriarchy as we go through these traits, I’m talking specifically about men who have been socialized by patriarchy to some degree. And that exists on a spectrum, some more heavily and some less. And when I talk about emotional immaturity, I’m talking about people who have been diagnosed with or struggle with these traits and behaviors of emotional immaturity. We’re talking about these as generalities. In patriarchy, we often see varying degrees of male centeredness, from egocentrism all the way to diagnosable narcissism. In emotional immaturity, this is also one of the core tenets or the foundation of the disorder: egocentrism or narcissism. In patriarchy, we often observe in these men decreased empathy. Empathy is not something that’s encouraged or cultivated in men in positions of dominance. Equally, in emotional immaturity, we see this lack of empathy. There’s very little interest in the lived experience of other people. In patriarchy, because of the foundational nature of male centeredness and egocentrism, combined with this lack of empathy in the patriarchal ideology, these men are perfectly conditioned to understand and express reality as one single viewpoint or one single experience, and that’s often expressed as white, cisgendered, heterosexual, and Judeo-Christian male.

In emotional immaturity, there is an interesting phenomenon called effective realism. That’s where these individuals define reality by how they feel at the moment, not by historical assessments or verifiable facts or objective observations. Denying things, dismissing things, or distorting things are the go-to tactics for any realities or experiences that EIPs – emotionally immature people – do not like. An ahistorical approach to situations as preferred. We see this same behavior amongst men socialized by patriarchy and people struggling with emotional maturity where they’ll often say things like, “Why do you keep bringing up the past?” Or they’ll completely ignore the past and say things like “DEI work is divisive and discriminatory,” which only makes sense in the context of there never having been any oppressions in the past at all.

Interestingly, in patriarchy we see self-reflection and emotional work are not encouraged for men. And often, it doesn’t even make sense to men why you would do that. When your position is the only real or the only right position, critiquing it or considering how it affects others is irrelevant. Everyone else is the problem that needs to conform to that central position, not the one in the center. In the same way, for emotional immaturity, we see self-reflection and emotional work avoided at all costs. They’re actually perceived as real existential threats to the emotionally immature person. From their view, all other people need to do the work of adapting and changing, not them.

AA: I do have to just jump in here, Levi. I have bells ringing in my head like, “Yes, this is what I see!” I’ve seen this play out over and over and over again with men that I know. Men in my life who are not bad, evil men, but I see these symptoms. And we’ll talk in a minute about the correlation or causal relationship between these things, but I just had to jump in and say how revelatory this is for me, but keep going.

LM: Yes, me too. In patriarchy, the worldview of these men is largely transactional. Patriarchy is concerned with two factors: gaining control of resources and maintaining control over those resources. Productivity, consumption, and permanence are guiding principles in the economy of patriarchy. This conditions these men to be very poorly equipped for reciprocal relational dynamics. Equity and mutualism are really difficult concepts to grasp when that’s your worldview. On the side of emotional immaturity, superficiality is often the flavor of relationships for these individuals. Reality is also viewed through a lens of resources, and relationships become transactional in the pursuit of those resources. We see the same mirroring here.

In patriarchy, men suffering from this stunted ability to empathize, a truncated capacity for mutualism in relationships, and the commoditization of everything puts these men in a position of really poor receptive capacity. It means that they struggle to accept and internalize love because that concept doesn’t really make sense. On the EIP side, we see the same struggle: poor receptive capacity for all the same reasons.

AA: Can you pause just for a second because that’s a lot of big words in a row and I just want to make sure for people who are catching up and processing it. When you talk about a truncated capacity for mutualism in relationships, what does that mean?

LM: Yeah. When I think of the word “truncated” I think of a tree that’s been cut down. You just have that trunk left, and a truncated tree is not a full tree. So, men who have been stopped in their ability to develop into a tree, to develop that trait for reciprocal engagement in a relationship, that’s what I’m thinking of when I say truncated capacity for mutualism. It’s just a sort of a fundamental immaturity in their ability to relate to other people.

AA: Mm-hm. And that poor receptive capacity also, like you just said, they struggle to internalize love. They almost are uncomfortable with intimacy. Is that another way of saying it? There’s something blocking or stunting their ability to be vulnerable and receive love. Am I understanding that correctly?

LM: Yeah, definitely. And we’ll get into that a little bit more, shortly. But I would say that men struggling with intimacy is a symptom of this poor receptive capacity. That’s one of the ways that it shows up. In patriarchy, we see that these men that have been heavily socialized by it are often poor listeners, owing largely to the decreased empathy and the single perspective reality that they experience. Because what someone else has to say is ultimately irrelevant unless they’re saying back to you what you just said to them. On the emotional immaturity side, same thing. Poor listening because of that single-perspective reality that they experience. In patriarchy, communication often takes on this one-way dynamic because of all these same factors. Men, heavily conditioned by patriarchy, often relate to others through pronouncements, controls, or demands. How many times have you heard a strongly patriarchally socialized male say something like, “This is what we’re going to do,” or, “I’ve made a decision,” or, “From now on, we will do this.” EIPs struggle in the same way. Because mutual relationships are not a part of their framework, declarations and demands are typical communication styles.

In patriarchy, a single-perspective reality that’s combined with decreased empathy and the transactional worldview make prime conditions for these men to subscribe to rigid binary thought patterns. You’re either in or you’re out. You’re either a supporter or you’re an enemy. You’re right or you’re wrong. These are all foundational postures to hierarchical systems of power. On the EIP side, we see the same thing. Individuals struggling with emotional maturity also function comfortably with rigid binaries inside transactional, single-perspective frameworks. You either love me or you hate me.

AA: That makes sense. If you think about emotional immaturity, I mean, even just watching my kids grow up, you can kind of see at the beginning that they do think in black and white. Their brains aren’t developed enough to hold space for nuance, to hold space for situations where two seemingly opposing things can be true at the same time. It’s striking me that people who don’t develop that skill at a certain point… it is childish to stay that way throughout your life, to not be able to hold nuance. Very immature.

LM: A code phrase that my wife and I have developed that we’ll just whisper to each other sometimes when we see these dynamics is “Toddler Man”.

AA: Haha. Yes, totally!

LM: Occasionally, when she’s having a conversation with someone and a man will walk up and start to talk over them to express what they want to say at that moment, even though it might be a generous thing they want to say, we just say “Toddler Man” and then we both know what’s going on.

AA: Yep. So good. That’s another one I’m going to put in my pocket. You’re giving me so many good phrases. I love it.

LM: Well, finishing up our list, back on the patriarchal side, there is a pattern of moral exceptionalism in men strongly socialized by patriarchy. When you think about the male experience being centered as ideal, in order for it to maintain its worth and its value and stay at the center, it has to be beyond critique. There can’t be anything wrong with it. So if it is ever wrong, it’s going to lose value. Combined with avoiding self-reflection and avoiding emotional work, patriarchy works to release men from accountability whenever possible, and hold all others to rigid standards of accountability as a way to support the power imbalance. This also makes it very difficult for men conditioned in this way to truly ever apologize for having caused harm to others. There is a lot of cognitive dissonance for these men about if there actually was harm in the first place, in addition to apologizing, feeling like an existential threat to these men because it means they’re wrong or they’re bad. I think a really great example of this is the four dog defense. Have you heard of that?

AA: I haven’t. What is that?

LM: It’s a tactic employed in this system where the example usually used is a dog bite. If I had a dog and it bit you, Amy, and you came to my door and said, “Hey, your dog bit me,” my first defense would be to say, “That’s not my dog.” And then when you provide the burden of proof to say that it is my dog, then I would say, “Well, my dog didn’t bite you.” Then when you provide the burden of proof to prove that my dog did bite you, I would say, “But it didn’t hurt you.” Then when you provide the burden of proof to prove to me that my dog did bite you and it did cause injury, then I would say, “Well, you provoked it. You brought this on yourself, it was your fault.” So it’s just deflection, deflection, deflection and reorientation so that I can stay beyond critique and so can my dog, and whatever issue you’re having is ultimately because of you.

AA: Wow. That’s so familiar and so helpful. You see it everywhere, right? You see it on the micro level in individual men all the way to governments not taking responsibility, and church institutions. I have wondered that so many times, and we’ll get to this in a minute, but there are also plenty of women who have a hard time apologizing and being humble enough to take responsibility for harm they’ve done. But boy, in my experience it has seemed to be very much a feature of patriarchal ideology. And that makes so much sense when you say that it is an existential threat because they feel that then they are bad. And you just think, “Just admit you made a mistake, it’s fine!” And men struggle with it so much in my experience, and presidents of countries.

LM: Absolutely. And as long as our identities stay conflated with the system, we will struggle with it. So part of my goal with our conversation today is to help equip men and women to see how we separate that so we don’t have to feel threatened by it anymore. On that point, flipping back over to the emotional maturity side, EIPs operate the same way. Rules and standards and morality do not apply to them, but they will apply it rigorously to everyone else.

On the side of patriarchy, when we combine all these aforementioned traits and behaviors, we see this crushing impact on the male capacity to be healthfully, psychologically integrated. Men are having personal experiences that do not always line up with the standard that they’ve been given, and so they’re faced with an option: they must either dismiss it and deny their own experiences, or they have to risk being expelled from the centralized group. This can lead to living a life of hypocrisy, where they are unable to align their inherited beliefs and their outward expressions with their personal experiences and actions. Further, the entitlement that men receive to commoditize everyone and everything, combined with the inbred narcissism that tells us that all things are for our consumption and we can do no wrong, creates disastrous conditions when we interact with vulnerable populations. Think about slavery, femicide, indigenous extermination, homophobia, ecological extinctions, and on and on. On the emotional maturity side, this is another one of these foundational characteristics. They are often poorly psychologically integrated and have hypocritical behaviors and single-sided moral rubrics, meaning that “they don’t apply to me, they only apply to everyone else.”

Finally, a foundational indicator of value and worth for these men is status and role. These ideas are also often narrowly defined and very rigid in their expression, as they are key to maintaining a hierarchical power dynamic, whether we’re talking about rigidity in role definitions of what men and women can do, or very narrow expressions of statuses like what a real man looks like. Due to the poor psychological integration and the stunted development of a real self, the identity of men inside patriarchal systems and institutions becomes conflated with those roles and positions of status. Same thing on the emotional immaturity side. These individuals often prioritize status and roles inside hierarchies and rigid dichotomies. They expect everyone else to keep to their assigned role and not to question authority, especially if they’re the one in authority, though they have no problem going against authority when they’re not.

AA: Wow.

LM: That list kind of took my breath away the more I expanded it and dove into it, and I found examples of it everywhere I looked. And it’s heavy. It’s a little heavy to run through all those examples.

AA: It is, but stunning. Again, those bells are going off. I hadn’t thought of this even though I had read your notes and we’ve talked about this a little bit, but when you say that both in patriarchal systems and a feature of emotionally immature people they have these hierarchies, rigid dichotomies, and they expect others to keep the roles and not question their authority, but then they have the right to question authority in a way that will maybe elevate them, I thought– It frustrates me, I mean, it’s almost comical. The very patriotic American, like the American revolutionary ethos with the “don’t tread on me” and how up-in-arms people still get about the British system and no taxation without representation, like, “How dare you tell me what to do?” And then these same men withhold rights from other people, like you said, cause an entire genocide on the continent. Like, “No one can tell me what to do, but we reserve the right to tell everyone else what to do, and we will fight with arms to defend our own selves, but how dare anyone else have an uprising against us when we oppress them?” I don’t know. The macro level was really obvious to me as you were talking about that.

LM: Yeah, it’s a main ingredient of the current flavor of patriotism in our country, I think. And it’s made it hard for me. We fly the international flag of the planet earth outside of our house. I don’t know if you’ve seen that flag, but our neighborhood is full of American flags, and I don’t mean to be anti-American or anti-patriotic, but for me, until we as a nation are able to grapple with these ideas and be honest about these dynamics… The Fourth of July has become really hard for me.

AA: Yeah, our family’s the same. It’s nationalism that is really, really scary. I’m sure we’re on the same page about this. I so appreciate all the good that America has done and continues to do, but there are some big, big problems, and the growing nationalism in the country is something that is really scary. And yes, it is inextricably a part of patriarchy. It really is. That white Christian nationalism and patriarchy are one in the same ideology.

LM: I agree, I agree.

AA: Anyway, let’s get back to the bigger overarching things. I’d love to hear your analysis of this list of features of patriarchy and features of emotionally immature people. How do you interpret that?

LM: Yeah. The question is, what’s our takeaway now that we see this mirroring effect between these two? What’s our takeaway? Well, here’s one thing I’ll propose to your listeners. I think it’s telling us that patriarchy intentionally promotes emotional immaturity in men. And as I realized this, it actually made me sick to realize that the system that I was born into, that I inherited, was systematically working against me, against my full development as a human. It was intentionally stunting my ability to relate to others in mutual and equitable ways. That doesn’t feel good when that’s your takeaway as you consider your world. In addition to recognizing all the harms that patriarchy brings onto everyone who’s not a part of that centered male category.

patriarchy intentionally promotes emotional immaturity in men

AA: For sure. I’m thinking of specific people, and of course, I won’t say who they are. But people who really do defend patriarchal systems, they would never admit that they were emotionally immature. So you’re saying that it is intentionally working against men’s full development, though it doesn’t know that that’s what it’s doing, right? It thinks it’s empowering men and actually it’s the best for everybody, but the result of what it’s actually doing is stunting men, is what I hear you saying, right? Though they would never admit that that’s what they’re doing.

LM: Well, all these traits that we’re talking about are sort of the quintessential man who’s stoic and strong and invincible, always has the right answer, and is the ultimate provider for everyone else. And those are cast in a positive light for us all the time. But when I think we dig underneath that and see what are the foundational things inspiring these fantasized or romanticized ideas about men, we see that it’s the same thing that the patriarchy actually is cultivating in men. So, we’ll talk in a little bit about how I think it’s an intentional move in order to keep it going.

AA: Yeah. I do want you to talk about that. First, could I ask you, what are some specific patriarchal norms that you were born into and then how you felt those effects in your life?

LM: Yeah. Thank you for asking about that, and I also won’t mention people specifically by name. But generally speaking, growing up, I often observed things in male leadership figures, whether at church or in business or in scouts or in relatives or family members, that now looking back, I recognize these same traits and behaviors. But at the time, like I mentioned, they were presented as what a good leader looks like, or how men are supposed to be. Things like freely critiquing others – that, from the male’s perspective, feels like helpfulness – but being beyond critique yourself. Always posturing like you have the right answer, whether you know what you’re talking about or not; relating to others through pronouncements and declarations even though, like I mentioned, they can often be benevolent or generous, they’re still controlling.

My wife told me about a friend of hers who recently said that she was struggling with this man in the family dynamic who would often do things like show up and say, “I booked tickets for all of us to go on this vacation” without talking to anyone about if they want to go. Do they feel safe going? Are they available to go? It’s just, “This is what I did as an act of generosity and benevolence, and if you reject it or are unhappy with it, you’re nasty or you’re being mean to me.” That type of pronouncement, sort of subtle demand, was the common feature of male behavior that I observed growing up in all these different circles. I could go on, but those are a few.

AA: Yeah, thanks for sharing those. I can think of lots of examples for me, too. But let’s get more into the literature and the analysis of the relationship between these two lists that you shared. What did you find in your research about their relationship?

LM: Yeah. Very interestingly, research is showing that the effects of being in a position of hierarchical power over others are eerily similar to the ways in which patriarchy socializes men and these traits and behaviors of emotional immaturity. What I’ve come to call “power brain damage” reveals itself in the development of these same traits. This is the list of traits and behaviors of people who have been in positions of power. We see the same egocentrism or narcissism, we see the same decrease in empathy for others, we see the loss of something called the mirroring effect, which is really interesting. When we observe someone doing an activity or describing having done an activity, like if I watch someone play the piano, whether it be in real life or in a video, the areas of their brain that light up to be able to play the piano also light up in my brain, even though I’m not playing the piano.

AA: Wow.

LM: It’s this fundamental neurological pathway for relatability between humans, and we see a loss of that when people occupy positions of power. We see decreased willingness to compromise, which leads to loss of relational equity, a loss of mutualism, and their interactions with others. We see reality being narrowed to a single perspective or experience, which is their own. People who are in positions of power also often exhibit something called illusory control, which is where they have an exaggerated belief about their own ability to influence outcomes that are actually out of their control. For example, if I were to run for office and say, “If you elect me, I will end the Ukrainian-Russian conflict in 24 hours.” That would be a good example of illusory control.

AA: If only. If only that would work.

LM: Yeah. People in positions of power also often exhibit decreased interest in feedback from others. That’s a direct parallel to avoiding self-reflection. They tend to rely on stereotypes for decision making, which is parallel to avoiding emotional work and not being interested in the lived experience of other people. They often adopt rigid binaries, and they do all these things to facilitate large-scale, rapid decision-making. Because if I’m going to think about everyone’s experience, it’s going to take me a long time to make a decision on a large scale.

They also often exhibit moral exceptionalism and self-righteousness or hypocrisy in what they say and then what they do or how they behave. And again, status and role are highly prioritized, often for the sake of efficiency and productivity in these systems of power. Maybe not surprisingly, we see an almost identical list of these traits and behaviors by humans that are put into positions of hierarchical power over other humans, as we’ve seen in the behaviors of men socialized by patriarchy and people struggling with emotional immaturity.

AA: I have to say, I mean, I laughed when you said “power brain damage”. It’s funny to say it that way, but as it sank in for a minute, I was like, “Oh no, that’s actually really what it is.” What you just listed, like you said, prevents people from becoming the fullest version of themselves, and from becoming fully realized adults. It is damaging people’s brains to have to be in that position of power. It’s crazy.

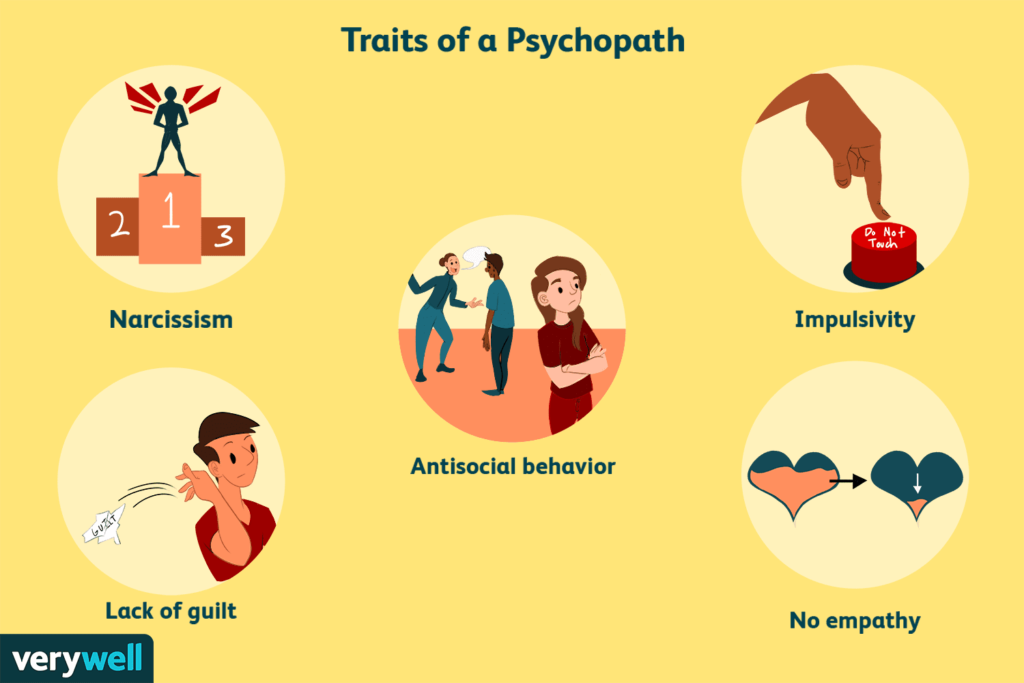

LM: Yeah. And obviously men are the prime target for this particular type of brain damage inside a patriarchal system. And I sort of jokingly use the term “brain damage”, but research actually shows that the brains of people in power respond in similar ways to social cues that the brains of patients who have suffered traumatic frontal brain injuries or people suffering from psychopathy do. So it’s not actually very funny, but it’s a real phenomenon.

And I just mentioned the similarities between the ways power affects our brains and the brains of individuals diagnosed with psychopathy, sometimes called antisocial personality disorder, and that leads to one more interesting dimension of this conversation. Incredibly, we see the same list of traits and behaviors in psychopathy that we have already seen in our conversation so far. People diagnosed with psychopathy often exhibit egocentrism or narcissism, a lack of empathy with little or no interest in the lived experience of others, moral exceptionalism, where they are immune to societal or cultural moral guidelines, and pathological lying and interpersonal manipulation are often hallmarks of psychopathy. In that we see that there’s no commitment to historical facts or accountability, and the perception of reality is based on how they feel at the moment, similar to that effective realism we talked about on the emotional maturity side.

People struggling with psychopathy also often suffer from delusions of grandeur and illusory control about thinking about how much they can control. There’s an avoidance of self-reflection, an avoidance of emotional work, and superficiality and transactional relationships are often the norm. Again, it’s the same list. The ways in which men are socialized by patriarchy, and the ways in which human hearts and the minds are affected by power, are the same as the traits and behaviors of individuals struggling with emotional immaturity and individuals diagnosed with psychopathy. Patriarchy and other systems of hierarchical dominance literally cultivate the traits of emotional immaturity and psychopathy in the world.

AA: Wow. This is kind of mind-blowing. And like I said before, it makes sense to me on all levels. At a macro scale with military leaders and a micro scale with people I have actually known. I also do want to bring up that, of course, I have known many men who have grown up in patriarchal environments who don’t end up reflecting those traits. And I’ve also known women who have grown up in patriarchy and they end up exhibiting those traits of emotional immaturity, though they haven’t been privileged with the patriarchal power. How do we make sense of the exceptions?

LM: Right, yes. The last thing I want is for someone to listen to this episode and then leave saying, “See? All men are psychopaths. I already knew that.” That’s not what I’m saying. Emotional immaturity and psychopathy exist on a spectrum, like everything does. Just like the traits and behaviors of men in power and men in patriarchy exist on a spectrum. Some men exhibit very strong traits and some are more subtle, just like the spectrum of emotional immaturity to psychopathy can range from an annoying coworker to a serial killer. There’s a wide range of ways to be there.

As you mentioned, equally true is the fact that emotional immaturity and psychopathy can exist outside of positions of power, and they can exist outside of maleness as well. Women can exhibit these traits and behaviors, too. And sometimes they’re the result of personality disorders, or other times they’re the result of having been socialized in similar ways that men have been socialized. Interestingly, I think, conversely, some of these traits and behaviors can also manifest from the ways in which women are socialized to enable these traits and behaviors in men. It’s a complicated web of dysfunction that we see patriarchy weaving for us.

I think the overarching idea is that all of these things have the same foundation. They are all growing out of the same ideological garden. Hierarchical systems of dominance grow relationally truncated, emotionally stunted, psychologically disjointed humans. And perhaps equally fascinating to me is that I believe, like I mentioned earlier, that it’s actually a reproductive strategy of these systems and ideologies to do so.

AA: Hmm. Yeah, what do you mean by that? It’s a reproductive strategy of the systems.

LM: I believe that because systems of hierarchy require those in power to commoditize and objectify everyone and everything, it necessarily requires a decrease in empathy. It requires egocentrism and it requires the avoidance of emotional work. Otherwise, the group at the top of the system will struggle to center their own experience above all other experiences. So these systems demand that we be unable to imagine a different reality than the one that’s been created by the system so that it can endure. It sounds so obvious when we say it out loud, but when humans empathize with one another and do not center a single experience above all others, systems of hierarchy dissolve. When humans take a posture of equity, relationality, and mutualism, power imbalances disintegrate. Becoming fully human is the antidote, I think, to the malformed socialization of patriarchy.

AA: This is reminding me of Nazism and actually in other ideologies in environments of enslavement, where there’s actually a systematic and intentional indoctrination that dehumanizes other people. That’s kind of what it’s reminding me of, that this whole thing will fall apart if we have empathy for the person that we’re persecuting, enslaving, murdering, right? So in order to reach the goal of domination, whatever the goal is, you do have to shut that part of yourself off that would look at the person and say, “Wait, would I want to be treated like that? Would I want my child to be treated like that?” Is that what you’re saying? It requires it.

LM: Absolutely. I agree one hundred percent. I think you got it exactly right. And interestingly, in recent years there has been sort of a counterargument to the position that I’ve been presenting today. Books and articles often explore what’s called “the wisdom of psychopathy” and they discuss the advantages and the positive effects of some of the traits and behaviors we looked at. They argue that in order to navigate the world of business or finance or politics and get big things done efficiently, these traits are actually an advantage. Decreased empathy, status and role prioritization, and being rigid or unwilling to compromise. Those things are necessary if you’re going to establish an empire or if you’re going to build a billion-dollar net worth or a trillion-dollar company. And I agree that these traits are encouraged and actually selected in those spheres and they are necessary to accomplish such things.

My question is, are any of those things good for humanity or for the planet? Can anything truly good come out of having less empathy for other people? Instead of isolating emotional immaturity and psychopathy as individual problems that need rehabilitation, and then turning around and extolling the virtues of power brain damage and psychopathy in business and in politics, I don’t understand why we struggle to recognize that the system is the problem.

Why can’t we see that the things that we classify as bad on relationship and crime podcasts and the things we classify as good on leadership and manliness podcasts are the same thing?

AA: Wow. Wow! So, why? Why can’t we see that? What do you think?

LM: Well, I think it’s because we have a love-hate relationship with hierarchy. And here’s some interesting information that I think is evidence of this. A study was done in 2012 where researchers had 121 experts use a standardized psychological assessment tool to rate the personalities of past U.S. presidents, and they based it on their biographical information from before they were elected. Then these evaluations compared with ratings of job performance compiled in two surveys of presidential historians of these same presidents. Interestingly, the presidents who came out with the highest rating, meaning they had the most psychopathic traits and behaviors, were some of our most beloved and biographed presidents in our history: Theodore Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton. These are the presidents that topped the list. Now, of course, this was done before Donald Trump was elected in 2016. Who knows where he would have landed on that list? I feel pretty confident saying that he would have been near or at the top.

So, what does this mean? Well, I think, I think that we recognize the problems that emotional immaturity and psychopathy cause on an individual level, and, at the same time, we’re conditioned to believe that the things that can be accomplished by those traits and behaviors on a large scale are good things, they’re necessary things. But my question is, are they? That’s what I would like your listeners to take away today, if nothing else, that they could make some space to consider and critique the things that hierarchical systems create and then decide if they’re truly good for us and the planet, or not.

AA: Hmm. This is a big question, and this one actually has been on my mind since the beginning of the podcast. I remember seeing a quote by Jordan Peterson, who was like, “Western civilization is patriarchal, get over it.” Like, “We wouldn’t have gotten to where we are, which is all of these exalted things, if it hadn’t been for these systems.” It was his way of justifying it, and I have asked myself that question, too. I mean, two questions. Sometimes it seems like the question and the answer is, “Is that even a good goal?” Like you’ve been talking about the commoditization of everything and this destruction of our planet, the literal destruction of the land so we can’t even grow anything out of it anymore. Was that a good goal to begin with? That’s one question.

But then another question I have is, is there a way to get the good things without having to do it in such an oppressive way? So is there a way to take the useful traits and behaviors in leadership, is there a good kind of leadership where you’re maintaining empathy and humility and egalitarian thinking? And I know that people are talking a lot about that right now, about how leaders can use their position to elevate other people and nurture their talents and help their organizations to thrive. I know that even when my husband was in business school, they talked about that a lot. And he’s a CEO, that’s something he thinks about a lot as a leader in the business world.

From my life, I was thinking, where is there an example of hierarchy that’s appropriate? And one example that came to my mind is the earned hierarchy of a professor and a student. When I sign up for a class in my PhD program, I go into that knowing that my professor has earned a PhD. They have years and years and years of experience that I don’t have, so I have respect for them and it’s their job to impart the knowledge that they earned, right? Comparing two professors that I’ve had recently, both are good people, no one was like just an absolute jerk. They were both men, but one had just a teaching style of making proclamations. I remember there was one class period where he asked a question and I was pretty sure I knew the answer, it was about civil rights amendments, I ventured my answer, and he literally was like, “Ugh, no!” And I just shrank like I was a little kid again. This happened like a couple months ago. I’m an adult, but you could feel the whole class just shrink. And I looked it up later and I was one year off. I was not even that far off, but he made me feel so stupid. And it was interesting because the next question he asked, the student to my side, kind of under her breath said, “Well, yeah, nobody’s going to want to answer the question now,” because we were all made to feel really small. He kind of established this unhealthy relationship in the class.

Contrast that to another teacher I’ve had where he cultivated this environment of support and safety. People felt very comfortable taking risks in asking questions and didn’t feel like they were going to be shamed for seeming like they didn’t know something. So I felt like in both of those situations, there was a clear hierarchy of teacher to student, but in one case the teacher kind of squashed students’ potential, and in the other case the teacher really nurtured student potential. That’s one example I thought of. Yes, you can have a hierarchy sometimes, but it has to be based on things that are earned, not on some biological trait. And there are ways to do it that elevate everybody versus ways that just put other people down and elevate only yourself. What are your thoughts on that, Levi?

LM: Yeah, I think it’s a good question you ask and I think I get a little hung up on the semantics of the word “leader” or “leadership” or “hierarchy” because I immediately go to power and control. For example, in my role as a dentist in community health and in public health, it’s often a landing place for dentists when they leave the military. They come, having been socialized very strongly in hierarchical ways of practicing medicine, and I often will have conversations with the dentists that I work with to encourage them to adopt a more equitable way of practice. We had an instance where one of our dentists looked at an x-ray and decided what was going to happen before they even met the patient, so then they went in and tried to make the declaration to the patient and the patient was completely uncomfortable with that recommendation. It wasn’t even specifically the recommendation, but it was the approach.

So I had a conversation with them and said, “We shouldn’t be making decisions about patients before we’ve even met them.” X-rays are helpful for us to gather diagnostic information and to get a piece of the picture of what’s going on, but until I sit down with a patient and talk to them, find out what their goals are, find out what their experience has been, find out what direction they would like to go, I can’t make any decisions. It’s not my job to make a decision for them. It’s my job to facilitate a conversation, to provide them with information that they need, and then help them get the care that they want, which may or may not be the care that I would seek for myself. That can be a little hard for some. I think just generally medical practitioners in America, because of the hierarchical nature of medicine and the patriarchal nature of medicine. It happened to be a female patient, so the dynamic was even stronger, where a male dentist knew what was best for her. So for me, instead of using the word “leader”, I prefer the word “facilitator” or “guide” or “companion”. I understand that you could argue that for reasons of efficiency and advancement and survival, our society’s compartmentalized information. Like, some dental information has been put into your brain, Levi, so that everyone else doesn’t have to have it in their brain. They can have engineering, mechanics, cooking, and whatever, and that way I don’t have to have all those things in my brain. I can go to them when I need it and they can come to me when they need it.

I think, first of all, letting go of the idea that you know what’s best for other people is key. And then from there saying, “Here’s the information I can provide to you. These are possible outcomes you might experience. What are you trying to do? How can I help you get there?” Because ultimately, I just have to believe you that you know what’s best for you and I will help you get there, even if it’s not what I feel like is best for me. And that’s okay. I don’t know if that’s helpful.

consider and critique the things that hierarchical systems create

AA: It totally is. I love that. Yeah, and I think you’re right that different words carry different weight to them and different meanings. Totally. I would be comfortable saying, “You may be the leader of my teeth.” And you might say, “I don’t want to be the leader, I’ll just be the guide or the facilitator.” And I’ll say, “Okay, that’s fine.” But yes, I like that. And here’s the thing too, is how you described the efficiency where you have dedicated your professional life and your education to diving deep in this one area so that I can study history and another person can study whatever it is, car mechanics and food science and whatever. So then it kind of all shakes out in an egalitarian society as a consensual, mutually beneficial system where we can benefit from each other, give to each other, and no one has a permanent birthright status to be above anyone else. But in different contexts we can take turns helping each other. I think that’s a beautiful vision of taking turns with leadership, or we can call it guidance. Which I get, and I think that’s really valuable to question even the word “leader”. I really liked that, actually.

LM: Yeah.

AA: Well, Levi, thank you so much for this totally illuminating episode. I really learned so much from you, and I hope that listeners and viewers will share this widely with people because I think these ideas are actually really, really helpful and could be world-changing, to be honest. I’m wondering, as we close, if there are any final thoughts that you’d like to share or resources that you could point us to so that we can learn more.

LM: Yes. Like I mentioned before, I definitely would recommend that people check out Dr. Gibson’s book, Disentangling from Emotionally Immature People. That’s a huge resource and you’ll just be highlighting and underlining and saying “yes” the whole time you read that book, like I was. Also, I want to sort of reiterate to your listeners that my goal for today was to try to help illuminate the idea that humans have all sorts of tendencies naturally, and it’s hard for me to say what would biologic males and biologic females be like if they developed in a vacuum, if they weren’t exposed to any sort of systems that were trying to influence their development. At the same time, I definitely see evidence that inside the system of patriarchy, men specifically are targeted with the amplification of traits that might already be there, or the cultivation of traits that wouldn’t naturally be there, all these traits and behaviors we’ve discussed today.

Equally, those traits and behaviors could exist naturally in women. They may be suppressed by patriarchy or in a reverse way amplified as they become enablers of those behaviors in men. So, considering that this is a possibility that humans in general are damaged by any hierarchy, whether they be in the position of dominance or the position of disempowerment, it’s a reality that we should grapple with and consider: do we want to participate in the hierarchy if those are the fruits?

AA: The fruits being literally brain damage, that was one of my huge aha moments. Brain damage and social stunting that’s actually demonstrable in evidence.

LM: Yeah, absolutely. And then if I could just close with one other thought, because as we discussed this, by no means am I done, but I’ve done a significant amount of emotional and therapeutic work trying to shed these traits and behaviors and to understand the ways in which I have been affected by these systems and institutions. And people who, though lovingly guiding me, were actually supporting me in these different ways of being deformed by patriarchy. And it’s something that I’m passionate about and talk about in sort of an objective way like this. And I recognize that it can be sensitive for men because it’s so isolating to be in that position. I read a book last year by the amazing bell hooks, it’s called The Will to Change, which I highly, highly recommend for everyone. Men specifically, I think that if they read this book they will find that so much of it, what she writes and observes, resonates with their experience. I just wanted to share a few lines from her book as my closing thought.

She says, “The unhappiness of men in relationships, the grief men feel about the failure of love, often goes unnoticed in our society, precisely because the patriarchal culture doesn’t really care if men are unhappy. Patriarchal morays teach a form of emotional stoicism to men that says they’re more manly if they do not feel, but if by chance they should feel, and the feelings hurt, the manly is to stuff them down to forget about them, to hope they go away. The reality is that men are hurting and that the whole culture responds to them by saying, ‘Please do not tell us what you feel.’”

She goes on and says, “In patriarchal culture, males are not allowed to simply be who they are and to glory in their unique identity. Their value is always determined by what they do. In an anti-patriarchal culture, males do not have to prove their worth. No male successfully measures up to patriarchal standards without engaging in an ongoing practice of self-betrayal.”

Finally, bell says, “Loving maleness is different from praising and rewarding males for living up to sexist defined notions of male identity. Caring about men because of what they do for us is not the same as loving males for simply being.”

AA: Just beautiful. I think the full title is The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love. Oh, that’s just beautiful and the perfect way to wrap up the conversation, to talk about love. And that’s what bell hooks always did. Well, again, thank you. Thank you, Levi, for those really profound insights. I’m so grateful that you joined us again for this episode.

LM: It was my pleasure. Thank you for the work you do and for the space to have these conversations.

when humans empathize with one another and do not center a single experience above all others

systems of hierarchy dissolve

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!