“the best way that my descendants could honor me is to put right the things that I did wrong”

Amy is joined by artist J. Kirk Richards to discuss challenging themes in his artwork, responses from the LDS Church and community, and how an artistic vision can push our culture to become more equitable, inclusive, and loving.

Our Guest

J. Kirk Richards

J. Kirk Richards is a contemporary artist whose work engages with themes of antiquity, religion, spirituality, equality, and love. His work asks questions about the modern application and implementation of religion relating to historical narratives and mythologies. His work often prioritizes the poetry of religious text over dogma or historical accuracy. Stylistically it often bridges or walks a tightrope between classical and abstract expression. In 2020, Richards founded a mixed-use art space, including studio rentals, a gallery that hosts monthly themed exhibits by living professional and semi-professionals, and a continued education art academy.

The Discussion

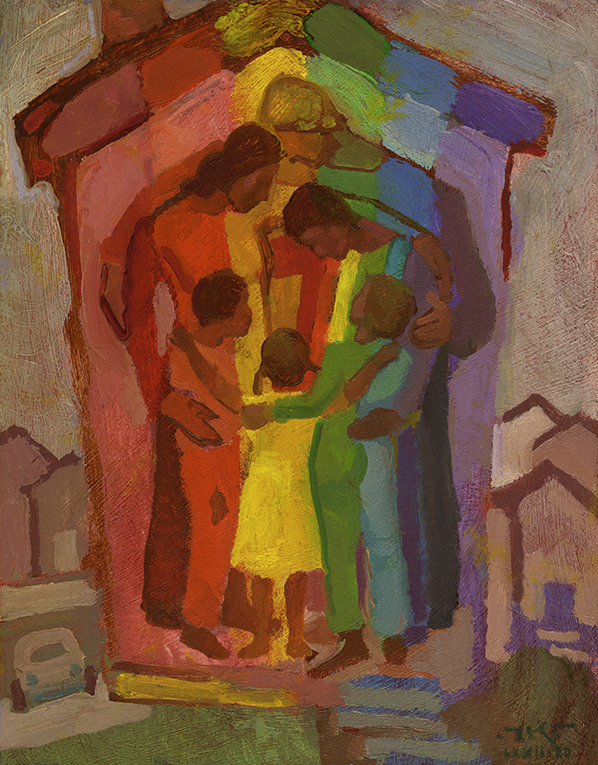

Amy Allebest: One time I was at a friend’s home and as we walked past her mantle, I saw a framed print of a family. There were two parents and four kids embracing each other in love and safety. And the whole home and all the people in it were painted in rainbow stripes amidst a neighborhood that wasn’t in rainbow.

I stopped in my tracks and immediately got tears in my eyes. The painting is called, We Have a Rainbow House, and it’s by the artist J. Kirk Richards. I later learned that Kirk has created an entire universe of profoundly moving and visually stunning artwork, a lot of which deals with themes that I would call egalitarian and perhaps somewhat controversially egalitarian.

He currently has an exhibit in Provo, Utah called Apology, but we’ll get into that a little bit later in the episode. For now, I’d like to extend the warmest welcome to my friend, J. Kirk Richards. Welcome Kirk.

J. Kirk Richards: Thank you. I’m so happy to be here.

AA: I’m so excited to have you here. We have a really rich and really fascinating discussion planned, but first, as always, I’d love to introduce you with a bio, but as you and I were talking before we started the episode, you said maybe you’d rather just introduce yourself. So maybe you can just tell us a little about you, where you’re from and how you started into the art world and the things that have made you who you are today.

JKR: Yeah. So I was born in Provo, Utah, in the shadow of Brigham Young University, just right up the street. And I grew up in a family of musicians. My mom is a violin teacher. All of the kids took music lessons. I had French horn lessons; I was a little kid carrying around this big French horn. And oftentimes my lessons were in the Fine Arts building. So I would walk through the galleries and I would see paintings on the walls and lithography prints, and just all kinds of artwork that really got me excited. I loved seeing them. I thought, wow, I’d love to be able to do this or participate in this or have a piece of this somehow.

And when I was about 14, I saw the movie Dead Poets Society and I dramatically begged my parents to let me trade in my music lessons for art lessons. And they did eventually a year later and so I took art lessons from then on. I studied art in school, out of school, ended up getting a Bachelor of Arts degree in Visual Arts. And since then I have been a career artist, so from the moment of graduation we just hit the road trying to make art and sell it. And that was 25 years ago. So I’ve been a studio artist for 25 years. I also, in the last five years, established a community art gallery. So we do lots of shows with lots of artists in the community. And then I also have an art academy where I teach, every week, a great group of artists.

AA: Amazing. Okay. I want to double click on what you said about Dead Poets Society, cause that I saw that as a teenager too and it was life changing. But as I’ve seen it subsequently, as I’ve gotten older, I realized kind of the limitations of my understanding of it when I was a teenager, but it sounds like you got it when you first saw it?

JKR: Well, you know, just being able to make the most of your time and do the thing that you love. That was a big takeaway from that movie. It’s funny because the movie champions the arts, even if in the face of practical life decisions—and I was trying to escape one of the arts and move into another one of the arts.

I just couldn’t imagine myself sitting through…when you play the French horn, you have basically a life of, if you’re in band, playing the upbeats and, if you’re in orchestra, counting lots of measures. And then coming in for a glorious two measure solo and hoping you don’t blurt it out.

I just wasn’t meant to sit; it was hard for me. And so being able to make things from a very early age—I loved drawing, playing even in the sandbox when I was very young, just moving dirt around. And that’s kind of what I do when I’m sculpting today.

AA: I love that. And then it’s so cool that you were able to make that work. And I want to kind of dig into the gendered implications of what you said too, because I know that a lot of men in patriarchal structures feel a lot of pressure to provide for their families.

And I think it’s one thing when I think about some of the women friends that I had in college and as adults who chose to major in the fine arts, but I know that at least in our context, an LDS context, they didn’t have the same pressure of, you know…

JKR: Absolutely. I remember when I first declared my major. I decided I was going to study art in college. One of my best friend’s mothers confronted me in the hallway in church and said, “What are you doing? How are you going to provide for a family?” And I’m sure my parents had a little bit of worry about it, but they were generally quite supportive. So I appreciate that.

But yeah, I do think even just once I declared my major, my art teachers told me if I can do anything else, I should choose the other thing.

AA: Your art teachers told you that? Wow.

JKR: Yes. And then one of the biggest goals of being a college student at BYU is to find a partner, right? To get married. And even just dating women…I think many women were not keen to date somebody who was studying art. They were looking for a doctor, somebody with prospects ultimately, and I don’t blame them, but that is definitely a component of those decisions.

AA: Did you ever struggle with it or did you just have enough faith in yourself? And then your girlfriend turned to fiancé turned to wife, your life partner—did she ever worry about that, and did you ever worry? Or were you just like “Nope, we’re doing this and let the chips fall where they may.”

JKR: Yeah, so as a freshman in college I hadn’t declared my major, but there was one day that I came home from after a figure drawing class and was just so fired up about it and loved it, you know, loved it so much. I prayed about it and I talked to my parents and I made a promise that if I could figure out how to make a living as an artist that I would help other aspiring artists to do the same. And I’ve drawn strength from that promise over the years.

most of your time and do the thing that you love

And so I’ve really never looked back at that since that time. And that was before I met Amy, my wife. So has it affected her? It’s not easy. It’s a lot like other small businesses; there’s risk and there are up times and down times in terms of income. And so we’ve had to weather those and I’m so grateful to her and give her all the kudos for having done that with me.

But yeah, it’s not all easy. It was hard for her to watch her friends in those early years and their partners in nice cushy jobs, you know, when we were still kind of at the beginning of building momentum in our career. And so she sacrificed and I appreciate that. And she’s always been a partner with me and making art and making our art career move forward.

AA: So great. I love that. Okay, let’s dive into the art that you make. And I’d love it if you could describe your creative process and how you decide what you want to create?

JKR: I love approaching things through multiple processes. And so there’s no one way that I do it.

These days I’m committed to so many shows that I’m painting or sculpting specifically with a theme in mind. So sometimes I will begin with that theme and then list out ideas that I have associated with that theme. Other times I just sit in front of an empty panel or canvas and just start putting paint on it. And as I move the paint around, you know, it will be a person and maybe that person has a certain gesture and that gesture begins to tell a story. And then I can build meaning into that story and make adjustments and further develop the painting to fill out that story and to clarify it or to make it more emotional or impactful to me and hopefully to the people who will view it.

So, I approach it from both ways. And hopefully, however I approach it, I get to a point where, again, I have the emotional underpinning or that it evokes the feeling that I want it to feel and communicates the message that I want it to communicate.

AA: Yeah, that’s really interesting. I know, like I said in the introduction, my first exposure to your work was through that We Have a Rainbow House painting.

JKR: We Have a Rainbow House, yes. And that painting is about the house. It’s about the family, but it’s also about the larger community because we have a rainbow community, right? We have acquaintances, loved ones in the LGBTQIA+ community or having those experiences. And to me, the painting is about how this is the reality, so we should embrace it and we should be inclusive and we should come to terms with that reality if we haven’t, and put love out there.

AA: What has been the response to that specific theme? We’re going to get to women in a minute, but first of all, let’s talk about like…you have a lot of paintings with rainbows that are specifically, to me, it seems radically inclusive, explicitly, like the message is love for queer folks, inclusion…actually even beyond love and inclusion, but radical inclusion and acceptance. And I’m just wondering in the context of the LDS church—which most listeners know has a really fraught history and even current relationship with that topic—how has it been received by LDS folks? And do you know about the institutional church’s response to your work?

JKR: Yeah, that’s a great question. I have had a spectrum of responses and I’ve grown in my own understanding and development. And so it was a little bit easier in the early years to post something that has a rainbow in it or to create something that has a rainbow in it. It took a little while for me to get to a point where I would make a painting that actually showed a same sex couple in it. So I’ve had to learn and grow and develop.

In terms of responses, I think most of the responses that actually reach me directly are positive. People aren’t usually confronting me if they disagree, but there is some pushback. I engaged in conversation with somebody this week who was upset with me for my rainbow work and said that I didn’t understand the long-term consequences of this imagery that I’m creating.

So there’s a variety there. I have not received direct feedback from the institutional church. I think there are certain leaders who love what I’m doing and certain leaders who don’t. There’s a leader who I think I disagree with on many things that once, and kudos to him, said with perhaps a wavering tone in his voice that I should continue to do my work about inclusion.

And so I think that there are leaders who see the value in voices and the development of the community, even when it is scary to them or goes against the official current stance of the institution because the institution, I think many of them know that it is a living institution.

AA: I just have to tell you how I see that work, like it makes me really emotional when I see it. And when I think about it too, it’s like you are in the company of artists through history that I see as making incredibly important change. And I know as I’ve talked to other artists, including my daughter, we talk a lot about like, what is art and if it has a political message? Do artists paint with a political message? At what point does it become propaganda to say a certain thing rather than just like the aesthetic value? There’s so many interesting philosophical paths that we could go down, but I think of other art that I’ve seen that moved the needle societally because it included, for example, the poor as like a subject that is worthy to be studied and that that was radical at the time and that egalitarian vision of painting people farming or eating potatoes just in their homes, just regular people that was radical at the time.

And we’ll talk about gender, but I just think the work that you do is so beautiful. It gives me chills to just kind of place you on a historical timeline with other great artists who have improved the world with their art too. So I want to thank you and I really honor you for that.

JKR: That is a wonderful compliment and I thank you. That would be my highest hope for the art just from an art standpoint, is that it would have historical significance, that it would be worth looking back at and thinking about the context and about the impact that the artwork had.

Oh, I didn’t mention this when you were talking about the feedback that I’ve gotten from my artwork. Probably the best feedback, the feedback that I love to hear about the most is when I hear about a bishop or a seminary teacher or class or something that has put one of my images on their wall in order to help kids feel like they’re safe in that space. Somebody that I know from the LGBTQ community—that texts me on occasion because they do a drag show in my gallery—I received a text from them and it said I had to meet with this professor I was very nervous about it. And as soon as I saw that he had one of your images on his wall I felt at ease and I felt like it was going to be okay. So that kind of impact is more than I could hope for in terms of a piece of art, a picture…

AA: That’s so beautiful. And I can just see future doctoral dissertations being written on this moment in the LDS church…in the broader American culture in these decades, but I feel like the past 10 years in the LDS church will be studied in the future and your work will be studied, will 100 percent absolutely be part of this massive sea change that we’ve seen in people’s attitudes, which actually translates into people’s civil rights and ability to thrive and have relationships with their families and not be cut off. It’s meaningful change that’s happening for real human beings and I think it’s just incredibly powerful.

JKR: Thank you.

AA: Okay, let’s pivot. It’s kind of still under the same umbrella, but let’s talk about women in your work. You paint a lot of women, and some of the paintings, I think, again, have overtly egalitarian themes. One that comes to mind is called On Equal Pedestals, and it shows a man and a woman, and they are on equal pedestals. So when did you first start thinking about gender equity and when did it start showing up in your art?

JKR: Yeah, you sent me questions in advance, and I’ve been trying to figure out the answer to this one. First of all, let me just get it out of the way that I make art and I love the beauty of art and oftentimes I choose to communicate that through the female face figure, and I’m okay if people don’t like that if they have an issue with that. I just love it. I love the beauty of the female form. And in the early years, one of my first great paintings, the first year that I was finishing college, was Cherubim and a Flaming Sword. And according to my understanding of LDS theology at the time, angels would have been male or are male.

And all of the depictions of LDS angels that I’d seen in official correlated materials were male angels. But I did love the work of James Christensen and others that depicted a more feminine angel. And so from that first year of painting paintings, I did Cherubim and a Flaming Sword and they were three women angels.

And at that point I realized if I’m going to do what I want to do and kind of depict the divine feminine, I’m going to have to break from a slavish being in line with what my understanding of doctrine was. I decided that my paintings were going to be less about dogma and more about the poetry and beauty of scriptural phrases or things like that. And that really, the divine feminine was going to be more interesting to me and more important to depict in artwork rather than dogma.

AA: Was that uncomfortable for you, or how did that feel? That was hard for me, for sure, to follow my own voice when it departed from dogma was very scary and hard for me at first.

JKR: Yeah, I think there’s probably a little bit of discomfort just wondering how people would think about me and my artwork and whether I was stepping beyond the boundaries. But I think pretty quickly pushing the boundary outward a little bit became an important part of my art practice. I think that art plays a part in reopening doors or opening new doors, whereas there seems to be this kind of dogmatic drift in religion.

There’s always this force that wants to ossify our understanding of what’s right and wrong and how things should be. And I think our art stretches that out. It’s a force that works against that to continue to expand the possibilities. So that’s one of the things that I see as my job as an artist is to do that on a regular basis.

AA: Okay. On women, especially in your religious artwork, my guess is that the church, as I’m thinking about the institutional LDS church, they would very much support those paintings because they elevate women and they definitely want to be seen as an institution that does support and elevate women and they want to think that they treat women equitably, although whether they actually do or not is up for debate.

JKR: A hundred percent…well, I don’t know if I can say a hundred percent, but I remember meeting with a very good-hearted church leader once and the phrase that came out of his mouth, which may have been a slip of the tongue or maybe wasn’t phrased the way he wanted to, but it was basically. He said that we want women to feel like they have an important role or a voice or a greater influence in church.

And I’m like, yeah…I just kind of nodded at that time, but yes, it’s more than a feeling, right? That feeling is coming from somewhere. But yeah, sorry, I didn’t mean to take over where you’re going with that.

AA: That was exactly what I was talking about. Yeah, they do want women to feel that they’re treated fairly. But as we know, equality isn’t a feeling. You can measure it. You can see it in policy. So it’s interesting. But how do you feel about that? That’s kind of an interesting question in terms of using whatever type of art it is or selectively using scriptures and saying like, look, see, we value women, we love women and almost using people’s art to show that they actually are treated equitably when actually they’re not.

JKR: Yeah, I mean, I don’t have an issue with using art to convey that message. I mean just being involved in images being used by the church in various departments and things. There are people who absolutely believe that and are pushing for more equality and the art committees are pushing for better art, you know, and so all of these committees at the ground level are working for these improvements. And then they have to go through a bunch of additional committee approval processes, which involve people who are less educated in those specific specialties.

And so I don’t think it’s hypocritical or wrong for the church to put forward those images because there’s no univocality, right? There are so many people in the church with their own ideas about how things should be, how the gospels should function. But in the end, the only official policy comes through the handbook and over the pulpit at a general conference.

Even then we have a lot of conflicting message. So I don’t see it as hypocritical, I just see it as a house that’s trying to be in order but failing a lot, that’s struggling to grow, is going through those growing pains. And a lot of times the growth gets cut off and it’s one step forward, one step back—but hopefully I do hope that we can grow. And we have grown and it’s not as fast as some of us want. It can be very frustrating. And you know, if I’m honest, I’ve had to work myself out of despair several times just because of that very fact. It hasn’t been the growth that I’ve wanted to see.

the divine feminine was going to be more interesting to me and more important to depict in artwork rather than dogma

AA: Okay. Well, on that topic actually, I do want to talk about your current exhibit that’s being shown in Provo right now. I think I misspoke in the introduction. What is the name of the exhibit, Kirk?

JKR: Yeah, the title of the show is First Be Reconciled. But I actually sent three titles to the gallery director and two of them had an apology in the title. And the third, the third one was First Be Reconciled.

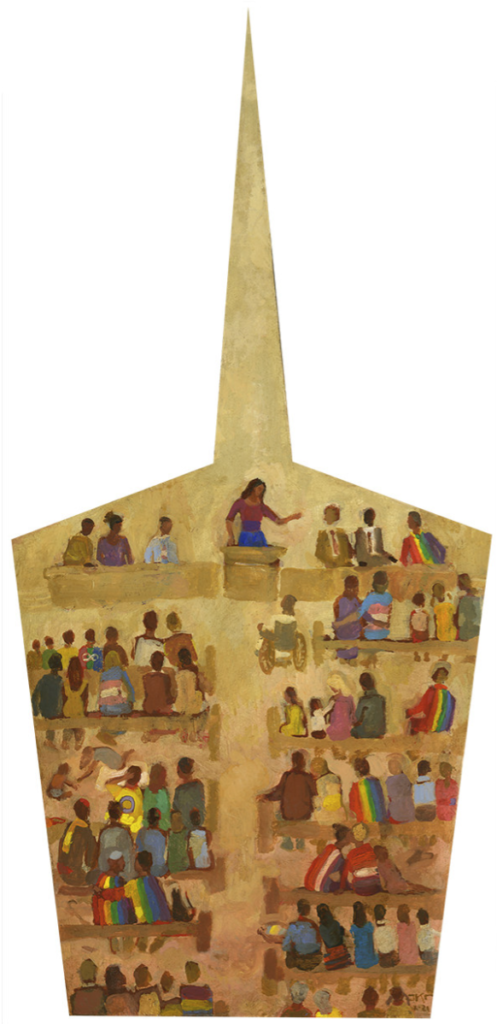

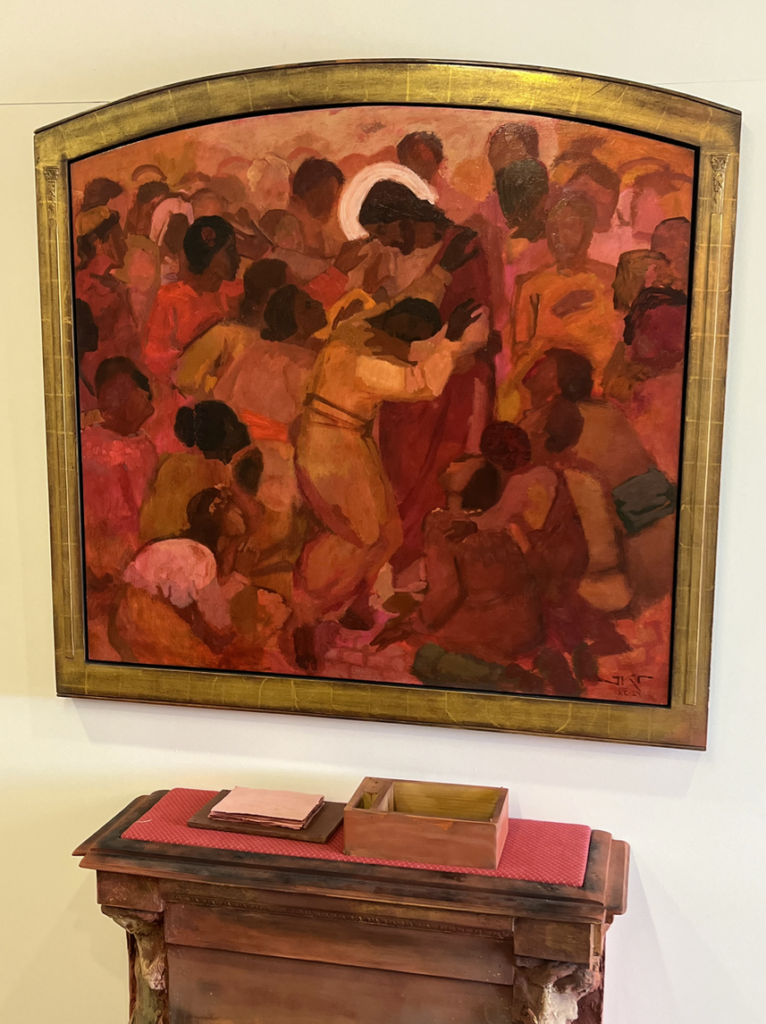

And that’s the one that we kind of decided on together, but First Be Reconciled comes from the Sermon on the Mount when Jesus talks says, if you are coming to the altar to give your gift, but you remember that your brother or sister has thought against you, has something against you, that you have conflict there, first go be reconciled to your brother or sister and then come back and offer your gift at the altar.

So there’s a big painting in that show that depicts Jesus teaching this idea and then there are…do you want me to keep talking about what’s this?

AA: Tell us all about it. I was able to go see it last week and I thought it was absolutely incredible. So yeah, I want to talk a lot about it. Tell us, what’s in it and what your thoughts were as you were making it.

JKR: So there’s the big painting about being reconciled and then bringing your gift to the altar. Additionally, there are seven kind of medium large paintings with seven altars, and each of those is about a certain topic. For example, the priesthood and temple ban on race. And I tried to make most of the paintings fairly positive, something that people would appreciate seeing while still being able to contemplate this thing that might be apologized for.

So a certain church leader has mentioned that the church doesn’t give apologies, that the word ‘apology’ isn’t in the scriptures. My show is not to really undercut that, but just to say that if the institution won’t do it, maybe some of our individual apologies will hold weight with time. Our loved ones that would love to hear an apology, like Amy, my wife has stopped going to church. She’s not participating. It’s been about four years and she would just love to hear apologies about some of these things. I know she’s not alone. It’s not the messy history of the church that bothers her as much as just the fact that we don’t apologize about anything that we don’t own up to some of the messiness. And so that’s partly what the show is about. You can actually, if you go to the art show, you can write out your own apology about a certain topic in church history or policy or whatever and place it on the altar.

So there are seven altars. The altars are altars that I built from wood and in the corners of the altars are sculpted caryatids and telamons, which are figures that hold up the weight of the architecture. Those are symbolic of the weight that we bear of these conflicts or wrongdoings or problems of the past and the present, frankly. And then also the altars have fabrics on them. The kneelers and the top of the altars have fabrics that are repurposed from used pillows that I got at Desert Industries, and that’s symbolic to me also; these are fabrics where people have laid their heads. They’ve put their burdens down and so on top of the altars are boxes with papers that are dyed. You can see that my apologies are written on yellow paper, and everybody else’s are on kind of pink paper. I wanted to dye them a tint of red because of just the idea of sin, sacrifice of passion, all of those things. So the show overall has a red tint to it.

Then there are also a grouping of probably what, 30 or so smaller paintings, maybe 25. And each of those has its own theme as well. Even though there’s not an altar for those, there is kind of a trough below those paintings where you can place your apologies. So just grab a piece of paper, write your thoughts and place them either on the altar or in the troughs underneath the paintings.

AA: Yeah, I did that when I was visiting the exhibit, and it was really amazing to have that kind of interactive piece to participate in the idea of apology in being reconciled and like reflecting on my own part.

My listeners know, because I’ve talked about it on other episodes, about my own kind of journey understanding LGBTQ issues and how Prop 8 affected me living in California at that time. And voting, actually going to the polls and voting against the right of same sex couples to get married…that’s something that I feel like I will be apologizing for and trying to make right for the rest of my life that I participated in that harm.

And so there was an opportunity for me to have an experience in the presence of this beautiful painting and with an altar there to take responsibility for my part in that. I thought that was really, really powerful to bring the viewer into the art that way was amazing. Can you talk about a couple, two or three paintings and altars, I guess topics that you chose to be included in this exhibit? How did you choose the topics and what are just a couple of them that you want to describe and tell us what they meant to you?

JKR: Yeah. You know, like I mentioned, one of them is the priesthood and temple ban.

AA: And can you talk about that for listeners who aren’t familiar with the church? What does that mean historically?

JKR: Yeah. Historically, in the very beginning of the church, the very early years of the church, the priesthood—or the authority to bless and to do certain ordinances and to do certain sacraments in the church—that was given to people regardless of race, but very quickly after the church’s founding that changed And so for decades and decades, people of African descent were not allowed to hold the priesthood or participate in temple blessings, temple ordinances. They weren’t allowed inside the temple.

AA: And I want to add, yes, a hundred percent. And just for people who aren’t familiar, absolutely. It’s true that that the priesthood qualifies you to participate in those certain ordinances, but when we talk about going to the temple, those in the LDS faith and doctrine, that is where you have an ordinance that enables a family to be bound together for eternity, meaning that you can go to heaven and be with your family forever. So being excluded from the temple, the priesthood ban isn’t like what you would think of in the Catholic church where it’s like, okay, well only a certain a small percentage of people are going to even want to be priests, right? So yeah, you’re excluding a small percentage.

In the LDS context, every single man is encouraged to the point of like…it’s necessary to go to heaven with your family. It’s necessary to be able to do daily things in your family’s life. Like I grew up with my dad giving me blessings when I would start the school year, or if one of us got really sick, he could give us a blessing.

So that ban on having the priesthood, again, is very different from other religions. It’s daily. It prohibits a man from acting in all the ways that it would mean in the religion to be a husband, to be a father, and to have your family be able to go to heaven. So there’s an additional many layers to it, I guess.

JKR: It’s not just the small percentage of people who want to go into the clergy being excluded from that. It’s ‘you don’t have an eternal family’, right? You don’t have exaltation. You’re not going to heaven the way that everybody else is.

So the painting above that altar depicts Jesus embracing a crowd of people of multiple colors and ethnicities, right? People with dark skin and light skin, they’re all coming into Jesus’s embrace. And under that, I wrote my own apology about the ban and my feeling that it was never from God, that God would not have asked for this and that I hope that we can have, in our institutions, diversity training—I think it would go a long way to make things right to have in our seminaries and institutes and our church schools. And even in Sunday school, some diversity training…and what’s the resistance to this?

I think a lot of people are worried that we don’t want to throw our earlier leaders under the bus. Right? We don’t want to call them racist. We don’t want to put a chink in their armor of prophetic infallibility. But we never believed in prophetic infallibility. First of all, as a church, that’s never been an official stance. And secondly, if I imagine looking down the road three, four, five generations, the best way that my descendants could honor me is to put right the things that I did wrong. Even if I didn’t feel like they were wrong at the time, even if I felt like I was doing the right thing in the here and now, if the repercussions of my current actions are a negative in five generations, there is no better way to honor me than to put those right. So that’s kind of the attitude shift or the idea that I want to spread with this art show.

AA: I love that. Yeah, that’s so powerful. I’m just thinking about like the genocide of Native Americans and that role our ancestors played in that, and that’s something that I’ve come to feel that my ancestors are depending on us to make right, right? I mean, if they didn’t know better at the time, and they do have some awareness of what’s going on in the world now…I just have to believe that they’re terribly grieved about what they did, and they’re no longer here to make it right, but we are, right? I mean, and that applies to all of these issues, all of these issues that we’re not responsible for the actions of people who came before us, but we are responsible for what we do with it now, and that’s not something to be afraid of, right?

JKR: Yeah. I mean, I think a lot of people read the commandment, honor thy father, thy mother, honor your ancestry in a way that means don’t speak ill of them. But really, in my mind, there’s no better way to honor them than to continue to improve our situation, our relationship, our equality, the way that we treat one another. And we honor the past by continuing to grow in the present and into the future. and making right the negative impact of the past.

AA: It’s so powerful. Okay, can you talk about a couple more of the altars and their accompanying paintings and maybe specifically some of the women that you represent?

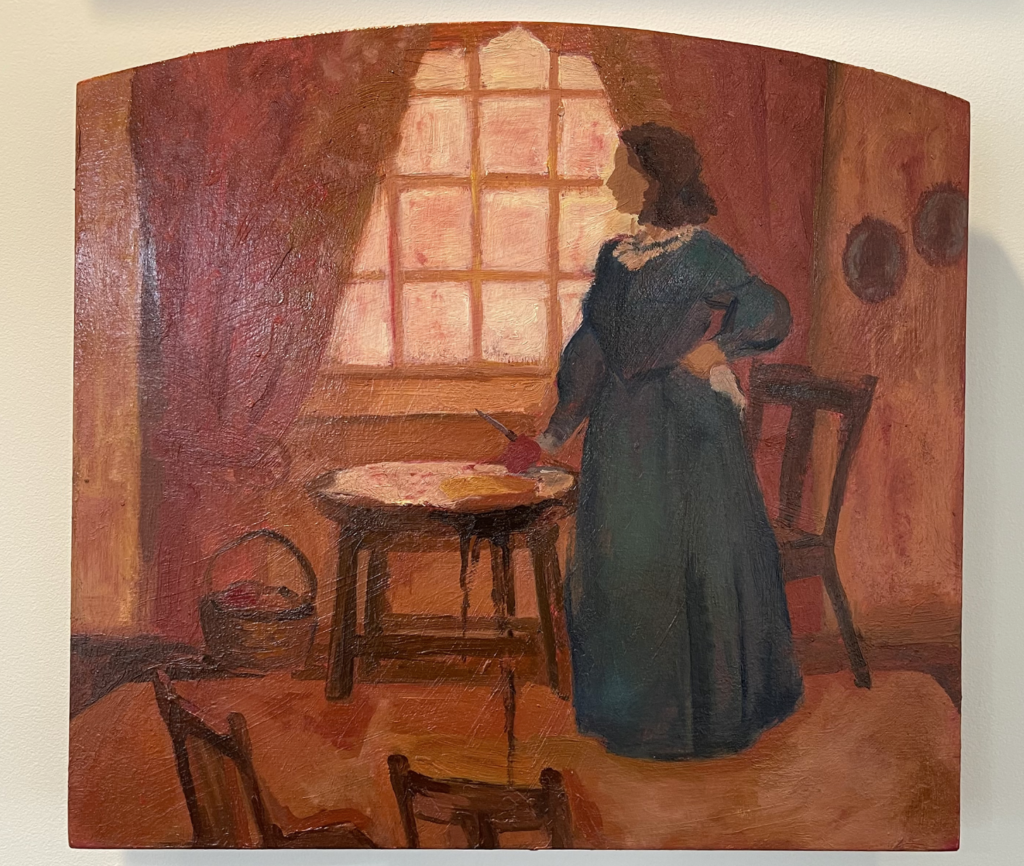

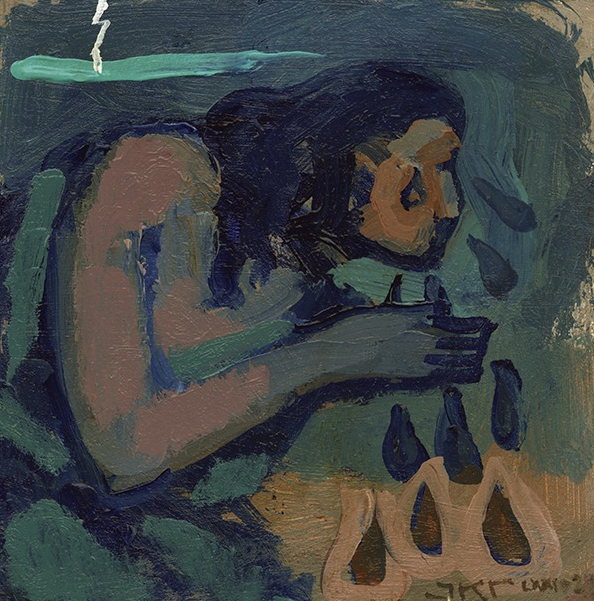

JKR: Yeah. And let me maybe jump right into the one that was probably the most biting, the darkest of the paintings, and that got a little bit of pushback on my Instagram. And that was The Happiness Letter.

So the happiness letter was…it may or may have not been written by Joseph Smith. I’ll just say that the founder of the religion ended up practicing polygamy. I would say that most historians find that an incontrovertible fact or find the evidence so overwhelming that it’s a given. So there is the story that you can take at face value or not, that Joseph asked a woman named Nancy Rigdon to be one of his plural wives, and she said no, and he sent her a letter.

Okay, so the reason we have a happiness letter is because it was published by somebody who was excommunicated. So it’s easy to dismiss and say, ‘well this guy was mad at Joseph and the church, and therefore he wrote this libel’, right? But something that I love is that the church is doing the Joseph Smith Papers. You can look up the happiness letter on the Joseph Smith papers. And there’s a commentary there that talks about arguments for or against that Joseph was the author of that letter. And whether or not he was, the Joseph Smith Papers project commentary says that Joseph wrote several similar letters advocating for polygamy.

So the painting may or may not have very sturdy historical grounding, but the message and my apology associated with that and with polygamy to me seems incontrovertible. There’s plenty of evidence. And the biggest thing that I said in my apology is that while we honor Joseph and I love doctrine—Covenants 1:21 is a gem of a scripture to me that talks about not coercing, not using your influence because you’re a church leader or whatever, not abusing that, right? And so I love those verses and I call them aspirational in my apology and say that the evidence is that Joseph, he did go too far. He abused his authority and his influence by pressuring people into marriages that they didn’t want to be in, by grooming young women and old, but also their families by pressuring them, promising them salvation if they did this thing.

We can reframe that as a community and say we honor Joseph for the revelations that he brought about, and also we can take lessons from those abuses. You know, similarly to how we would view King David from the Old Testament. He did wonderful things. He was beloved of God. And at the same time, he abused that power and we can learn from both of those things. So if we can do that with David, why can’t we do that with Joseph?

The painting itself depicts Nancy Rigdon standing at her table, reading a letter. In her hand is an apple, which I think harkens to Eve a little bit, and also a knife. And it’s just about the feeling, right? The feeling of coming to terms with the fact that there is fallibility in prophets. There is, even as Joseph said, once somebody feels like they get a little bit of power, they will exercise unrighteous dominion. And he warned us about that. And I think he saw it in himself, and that’s why he knew about it so intimately.

AA: Mmm, that’s an interesting take. And that there should be an apology for it, I do think it would be really meaningful. I was going to ask you about that painting specifically, because I noticed it’s really thick, black, almost looks like tar, kind of is what it reminded me of, and it very much conveyed that feeling that I have in my chest just thinking about what that would feel like, like this person that you trusted, the person that you trusted, not just interpersonally like a guy you know, but that you thought was speaking for God and then they asked you to do something that is just so deeply offensive and terrifying Yeah, I mean…first of all, I have to say too, like to say that the word ‘apology’ is not in the scriptures when the word ‘repent’ is like one million times all through the scripture, like to acknowledge what you’ve done wrong. And we even grow up as little kids in the LDS church learning this, the steps of repentance.

JKR: The steps of apology. And first, be reconciled. Yeah. How do you do that without an apology? You don’t go up to your brother or sister and say, I’m here to be reconciled and I’m not going to apologize.

AA: Right. No.

JKR: So, you know, I’ve received pushback about the show because some people don’t believe in collective apologies. They don’t believe that we should be apologizing on behalf of our community or on behalf of things that other people did. But the bottom line, well, there’s a couple of bottom lines to me…

One is that we do a lot of things vicariously as Latter-day Saints. We do. In fact, one of the other alternate titles that I would have had for the show would be Apology For, And On Behalf Of just to draw that parallel to other vicarious works. Like we do baptisms for the dead, you know, other things to be explicit about it.

But another thing is I tried in my own apologies…it’s a tricky needle I’m trying to thread, but part of it is I am trying to involve myself in the apology. For example, with this happiness letter apology, my apology was, ‘I’m sorry that. That we have pretended or that we have kind of swept this under the rug and just ignored that elephant in the room.’ This is such a glaring thing in Joseph Smith’s character that we would never talk about in a church meeting. Right? So that’s what I’m apologizing for, is for leading anybody to believe that I don’t know about this part of the history. This is something that I know about and I want you to know about and want you to know that I know and that if there’s any way that we can move beyond kind of sweeping things under the rug, I’d love to do that personally and collectively with whatever friends of mine are willing to do that with me.

if we can do that with David, why can’t we do that with Joseph?

AA: Yeah. It’s really, really, really powerful. Again, like I said before, I love the space that you’ve created. There’s something spiritual about it for me that like you have physically, like you said, you wrote your apology. I wrote some. There’s stacks of papers from people who have been able to come through the

Space, through the exhibit and participate, but there is something spiritual to me in creating an altar and creating a painting and inviting contemplation on the topic…that I don’t know.

I don’t know if it will prompt a deeper apology from the institution because like you said, it isn’t your job. It’s not your responsibility to apologize for the practice of plural marriage, that you didn’t do it. You don’t have the ability to make that right necessarily, but I will say—as a woman—hearing you acknowledge it, hearing you be a witness of it, and saying, I care, and especially in your case, I care enough to paint about it, I care enough to write about it, I care enough to invite people to think about it, is incredibly healing.

Even for me, because I do feel like collective harm is done, even though I wasn’t coerced to be a plural wife, the implications of that, like Carolyn Pearson calls it ‘the ghost of eternal polygamy’ that haunts all Mormon women from the time we’re girls and we learn about it, that that could happen to me. That happened to my ancestors. That’s what God thinks of me. I’m worthless. To have living men, even who didn’t do it themselves, to say ‘that was wrong, and I’m going to say that’.

So, yeah, you don’t need to apologize. You didn’t do it. But to acknowledge it and be a witness of it is incredibly powerful. And maybe that’s all we can do.

JKR: Thank you. When I think about one of the Latter-day Saints articles of faith is that we believe that people will be punished for their own sins and not for Adam’s transgression. And then we kind of extrapolate from that, that we won’t be punished for anybody else’s transgressions except our own.

But there are also verses in the Old Testament that talk about being punished unto the third and fourth generation for certain sins. And to be really frank about it, when I look at how we move in the world today, we are punished for certain sins of our forebears, and we also benefit from certain good things and sins of our forebears. So we can’t completely separate ourselves, whether or not in the final judgment day and in the eternal scheme of things, that judgment will fall upon us. There are judgments in this earth life that happened to us because of the systems that have been created around us, the way that we operate in those systems.

And so, I don’t feel like it’s out of the question or out of step or even out of the theology to offer an apology as part of a group, even if the group itself isn’t ready at the highest levels. If there’s a groundswell of interest in apologizing, that’s how maybe one day the sentiment will change on the institutional level.

And again, I didn’t try to frame it that way, like I think that the leaders need to apologize right now, but I am trying to frame it as in the way that there are people in our lives right here and now that apologies like this will mean a lot to, it will build bridges and mend and heal wounds, I think.

AA: Well, it meant a lot to me. I did find it really healing, and I was speaking with a gay friend of mine who saw the exhibit too, and she found it incredibly moving and incredibly healing also. So those are just two, and I know that it’s having a big impact.

Well, Kirk, that brings us kind of to the end of our discussion. I just want to thank you so much for your work, and thanks for joining us today. And before we wrap up, I’d love to have you tell listeners where they can find all of your work in person. If you have a website and what your social media handles are.

JKR: Yeah, I’m a bit scattered, but you can find a lot of what I’m working on now in my Instagram posts and my handle there and on Facebook is @jkirkrichards. My website is jkirkrichards.com. And I have the show at The Compass Gallery on Center Street and Provo through the end of September. And there’s always a lot going on. I own my own gallery, JKR Gallery in Provo. And I usually do a solo exhibit there in the spring. I think my next show will be March and April in the gallery there. So would love to have you come. We’d love to see you. We’d love to have you write an apology at The Compass Gallery if you get a chance to do so.

AA: Wonderful. Well, thank you so much again for joining us today.

JKR: It’s a pleasure.

make the most of your time

and do the thing that you love

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!