“How do you say “patriarchy” in your own language?”

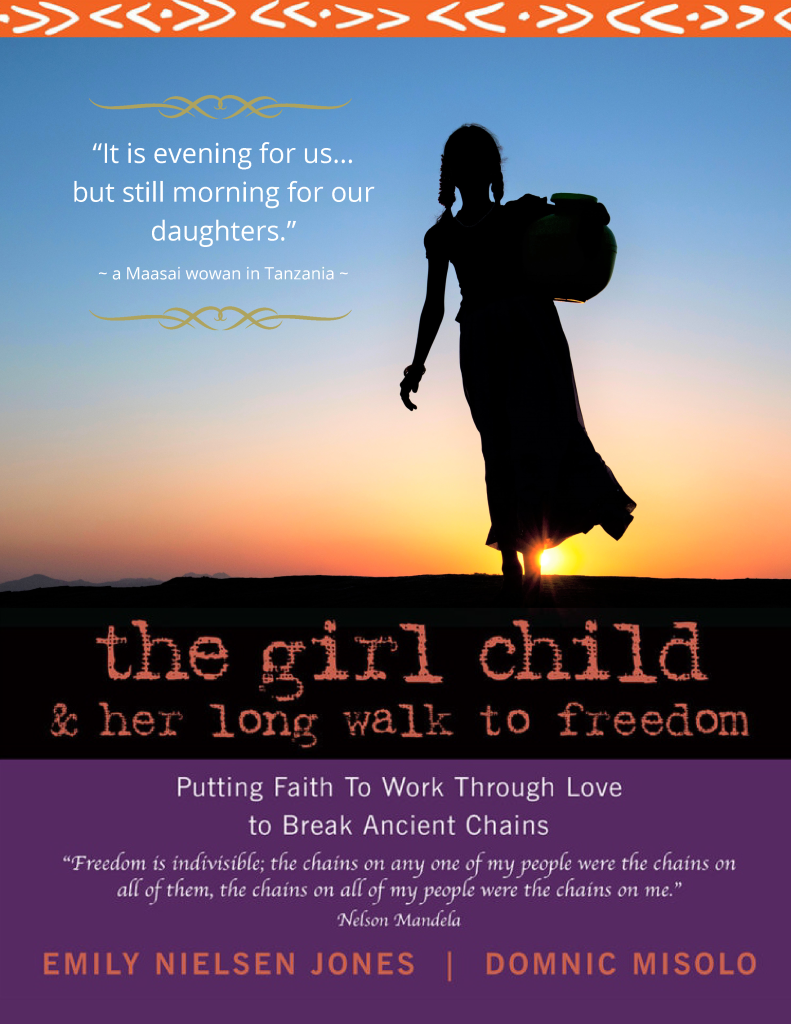

Amy is joined by Emily Nielsen Jones & Kazi Mghendi to discuss their project — The Girl Child and Her Long Walk to Freedom — a faith-based organization seeking to spread awareness, share resources, and organize women and allies to push back against global patriarchy.

Our Guests

Emily Nielsen Jones

Emily Nielsen Jones is a donor-activist engaged in promoting human equality, justice, and peace around the world. She is particularly passionate and engaged in the nexus of faith, gender, and development and working to mobilize our faith traditions to more fully and unambiguously embrace gender equality. In her role at the Imago Dei Fund, Emily has helped the foundation to adopt a “gender-lens” in its grantmaking with a particular focus on partnering with inspired female change agents, locally and around the world, to build bridges of peace and create a world where girls and women can thrive and achieve their full human potential. Emily brings a contemplative posture to both faith and philanthropy and is passionate about supporting the inner lives of change agents to lead with love and be their best selves in the challenging work they do.

Emily is actively engaged in the women-led philanthropy movement, and is the author of numerous articles. She is the recipient of the Christians for Biblical Equality 2013 Micah Award and was named a 2014 Women’s eNews “21 Leaders of the 21st Century” honoree. Emily has served on various boards including the Boston Women’s Fund, Women Thrive, New England International Donor Network, Girl Rising, Union Theological Seminary, Nomi Network Campaign Leaders Council, and Sojourners Founders’ Circle. Emily has a BA in Government from Dartmouth College and a Master’s in Educational Policy from Boston University. She is a trained Spiritual Director through both the Selah Spiritual Direction Certificate Program and the Still Harbor Spiritual Direction Practicum.

Kazi Mghendi

Kazi Mghendi is passionate about leadership development at all levels and uses her experience and expertise to identify and support community-led solutions to ending injustices caused by poverty and inequalities. With over 12 years of experience in humanitarian, leadership training, social development, community development, and financial inclusion, she leverages her expertise to solve some of the world’s challenging and complex issues, including improving education standards in rural communities in Kenya. Kazi joins The Girl Child & Her Long Walk to Freedom team as a Project Manager to support the project and its mission to liberate our societies from patriarchal beliefs, values, and cultures that have seen girls and women as lesser humans in society for generations. Her focus and passion is in international development, leadership coaching, fundraising, partnerships/relationship management, project/program management, systems design, and strategic thinking to solve community challenges.

Kazi founded Elimu Fanaka, a non-profit organization impacting public primary schools in rural underserved communities in Kenya through improving access to quality education and using systems change to create sustainable communities. She previously worked at Acumen, managing their East Africa Fellows Program and Academy, at Ongoza Institute as Stakeholder Engagement Manager, and at Adaptive Change Advisors as a Project Manager. She holds a bachelor’s degree in International Development with a concentration in Integrated Community Development from Daystar University and a Master’s in International Relations – Diplomacy and Foreign Affairs at the United States International University.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: When I first decided to launch a YouTube channel on the history of patriarchy, I started by researching all of the videos that already existed on YouTube. I soon found a short, animated, explainer-type video that was called “The Girl Child and Her Long Walk to Freedom”. After five seconds, I was completely hooked and drawn into this beautiful, powerful narrative on the history of global patriarchal oppression. I actually forwarded this video to a lot of people, and I am so excited to welcome the creators of this video to our podcast today, Emily Nielsen Jones and Kazi Mghendi and The Girl Child Long Walk Project. Welcome, Emily and Kazi!

Kazi Mghendi: Thank you, Amy, for having us. We’re super excited to be here.

Emily Nielsen Jones: Hello, Amy. I am a big fan of yours and your work. I’m so grateful to be here with Kazi and I’m so grateful you found our video.

AA: I’m so grateful too. I really, truly was so moved by it. And, like I said, I’ve watched it multiple times and sent it to lots of people in my life. I’m so, so grateful for the work that you’re doing and I’m really happy to be sharing it with our audience. We’ll actually watch this short video together, or listen to it if you’re listening on a podcast, and then we’ll discuss it afterwards. But before we get to that, I’d love to know some of the backstory behind the video, which has nearly 80,000 views as of right now, and that’s just the English version. It was launched on July 10th, 2020, and since then the video has been translated into 12 other languages with a couple more in the works. That is so exciting, too. You’re having a global reach and I’m just thrilled about it. But before we even get to the background of the video, I’d like to have you two introduce yourselves as well. And as I usually do, I’ll read your professional bios first to introduce you professionally and then you can tell your stories after that.

So, Emily, your professional bio: Emily Nielsen Jones is a writer and donor activist engaged in promoting human equality, justice, and peace around the world. In her role at the Imago Dei Fund, Emily has helped the foundation to adopt a gender lens in its grant making with a particular focus on partnering with inspired female change agents locally and around the world to build bridges of peace and create a world where girls and women can thrive and achieve their full human potential. Emily is the co-author and convener of a project called The Girl Child Long Walk, which invites participants to better understand the historic and religious roots of patriarchal oppression that persist in our world today. She’s also a trained spiritual director and enjoys having spiritual dialogue with people on a journey to reclaim their own consciousness from authoritarian patriarchal expressions of religion.

Kazi’s professional bio: Kazi Mghendi is passionate about leadership development at all levels and utilizes her experience and expertise to support community-led solutions aimed at ending injustices caused by poverty and inequalities. With nearly fifteen years of experience in humanitarian work, leadership training, social development, community development, and financial inclusion, Kazi addresses some of the world’s most complex issues, including enhancing education standards in rural communities in Kenya. She joins The Girl Child Long Walk team as a project manager dedicated to advancing the project’s mission to dismantle patriarchal beliefs, values, and cultures that have historically marginalized girls and women. Additionally, Kazi founded Elimu Fanaka, a non-profit organization focused on improving public primary education in rural, underserved communities in Kenya.

Both of you have incredibly impressive credentials and I’m sure have a really interesting and vibrant work experience of doing so much good in the world. I’m so impressed. I’d love it now if you could tell us a little bit about yourself, each of you, more personally. Tell us where you’re from, a little bit about your education, and what brought you to be the person you are today and do the work that you do. I’ll have you start first, Kazi, since your bio is freshest in our mind. Does that sound good?

KM: Alright! Thank you so much, again, for having us on this podcast. We are thrilled and we are excited to discuss the work we do. I just want to say about myself that I’m in Kenya right now, I’m in Nairobi. I was born here, I grew up in rural Kenya, and perhaps that’s why I love working with rural communities. Why I do the work I do, perhaps it’s also inspired by my own journey and experience. As a young girl growing up in rural Kenya, excited about life, I had to meet certain hurdles in the way that really could interfere with how the path could have been. I stayed out of school for around seven years before I went to high school, after elementary, and that really changed my trajectory and desire for who I wanted to become. If you had asked me when I was young, I’d tell you that I want to be an international relations person doing trade in my country or in another country. But then because of the challenges that I went through, I decided to focus on community development and community issues. I wanted to see how we could inspire change through working with the communities in participatory systems to see transformation.

Education was one way, and it felt like the best tool to use. And starting with children at a young age really is the best way to bring the change, because most of us adults have already developed behaviors and habits that can be hard to break and change. But working with children helps to mold a culture and cultivate that behavior and habits that you want to bring that are sustainable to life development. That’s how I got into this work. And when I saw this amazing opportunity at The Girl Child, I was like, “I love what I’m seeing.” I loved the video, it really moved me, and I was like, “I want to be part of this movement and I want to be among the voices that will bring change in this world through faith-inspired communities.” And that’s why I ended up meeting Emily and working with her.

AA: That’s amazing. And I have to say, too, one thing that I didn’t mention is that I found that the women that I forwarded the video to, so many of them got back to me and said, “Oh my gosh, I’ve been looking for something that I can watch with my kids.” So, to your point, Kazi, I so agree with that. The younger we can reach people in all the different ways in intervening, in good healthcare and education and expectations of life in their faith tradition if it’s got some problematic elements, and to not have to do all of that deconstructing work once they’re older, to be able to reach them sooner can prevent so many problems. And that’s how the world will change, right? Through reaching the young people. I am really inspired by that vision.

ENJ: Well, amen to that.

AA: Emily, why don’t you take it away from here to tell us where you’re from and a little bit about your story?

starting with children at a young age really is the best way to bring the change

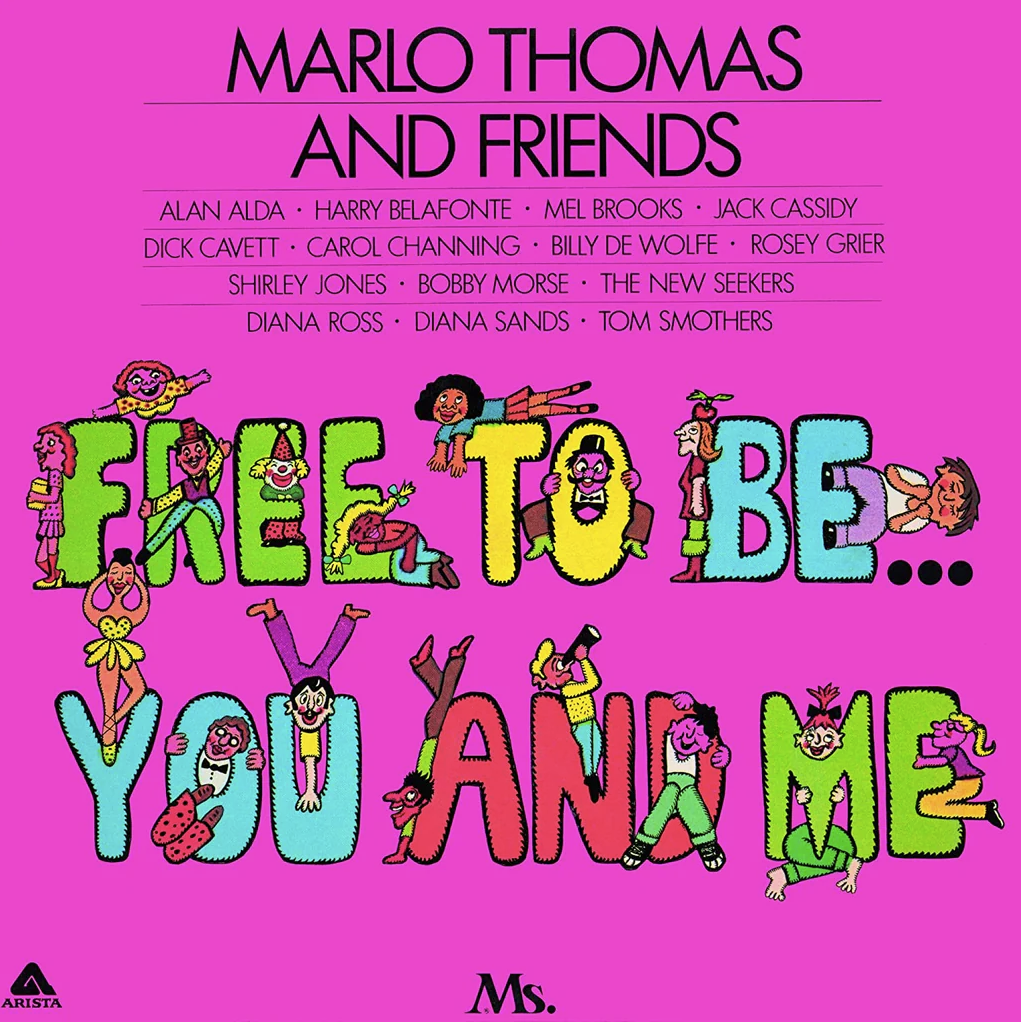

ENJ: Sure. I am so glad that you are starting with this question about our backstory and our childhood, because the protagonist of our video, as you know, is a girl child who represents the inner child within each of us, which comes into the world with this knowingness inside. My own girl child story began in the 1970s in upstate New York in the US in a very loving, secure, middle-class, Christian, and I’ll add, a very girl-centric family. Two iconic ‘70s symbols loomed large in the backdrop of my childhood. Number one, the wood paneled station wagon sitting in the driveway, and number two, the very iconic record album called Free to Be You and Me. It was a real jam with all of these classic voices from the ‘70s singing songs and reading stories, all of which had one simple message: regardless of whether you are a boy or a girl or where you come from, you can do anything. And I would say that my childhood had that hopeful, forward-looking, and free-spirited quality about it. I didn’t realize it then, but the ‘70s was a really great time to grow up as a girl. I really loved being a girl. I had a poster in my bedroom that said, “Girls can do anything better than boys” with a picture of Smurfette walking into a door that said “President” over it.

AA: Wow.

ENJ: I’ll just say that my childhood shaped the ground floor of my personhood and gave me a wired-in presumption of equality and fairness, which has always been there as far as I can remember. Overall, the world mirrored this back to me, except in one place: the church. And this has been the story of my life, as I have been formed within an assortment of evangelical churches, ministries, and camps. And yes, there were many soul-puncturing moments as I awakened to patriarchy. The earliest childhood moment of both awakening to patriarchy and dissent that I can remember was in my fourth grade Sunday school class in the Southern Baptist Church we went to. It was when the Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher, Brother Dan, would only ask boys to pray and read scripture. This angered my sisters and me, and we’d go home and complain to our Free to Be You and Me-mother who rotated in with him as our Sunday school teacher. She validated our concern and would complain to him, but he persisted. Looking back, that was really the first moment when my presumption of equality was punctured. And I want to just say, thank you, Brother Dan, for awakening my early feminism. And there were other moments in adolescence.

Then in my early thirties, I had something of an existential crisis, which led to what I would call a spiritual awakening. While I was having babies, I kind of reclaimed my own quest as a human being, my own journey to live freely from within my own personhood, my own soul, and allow myself to be curious. Right on the heels of this early 30s existential crisis was kind of another existential crisis when I started engaging around the world and beginning to see how heavy the patriarchy is, and how hard it is to grow up as a girl in so many places which had the same patriarchal beliefs that I was raised around, but these beliefs were used to sanction and justify a more blatant and subjugating treatment of women and girls than the softer patriarchy I had been around in the US. This wrecked me to the core and exposed me to an intolerable status quo of normalized sexual violence, devaluation, overwork, and myriad patriarchal traditions, which steal childhood from too many of our world’s girls.

At this time, my youngest childhood girl, named Lexi, was about nine, and this is the age that lots of bad things happen to girls. And basically a mother bear crawled out of her cage. “How could this be,” I was asking myself, “that everywhere in the world the bar is still so low for women’s and girls’ human rights, and that it is moving backwards?” Anyway, I’m going on a little too long, but basically this mother bear crawling out of her cage could not accept watching the needle go backwards for my daughter’s generation and all of our daughters’ generations around the world, and our sons too. Not on my watch. This mother bear has been the genesis for all the work I have been doing, both funding and supporting faith-inspired change agents around the world to navigate these authoritarian, liberating contradictions that we see within religion. To make a long story short, in many ways, I am the girl child of our video, as is Kazi, probably as are you, Amy, and everyone listening to this. Thank you.

AA: Oh, thanks, Emily. Yeah, I for sure could relate to a lot of what you talked about. Although, personally, I was definitely more under a bubble of the patriarchal religion that I grew up in. I didn’t have a Free to Be You and Me childhood, haha. Everything I learned, everything I heard was through the lens of a very patriarchal religion.

ENJ: I do look back and I really do appreciate many things about the ‘70s and Free to Be You and Me. A lot of the things that shape your childhood imagination really form the ground floor of your soul. But then what you do with that– and many people have varying degrees of, I guess, we’ve all been deeply indoctrinated by patriarchy. And I was as well, I don’t want to minimize that. It took some deconstructing, but there were offsetting influences.

AA: Yeah. Well, now I feel like I want to go back to Kazi because I’m loving this framework of introducing yourself, Emily, as like, what is your girl child story? So, Kazi, I’d love it if you are willing to dive into that a little bit more and tell us about those influencing factors in your own childhood growing up.

KM: Yeah, sure. Mine might not be as beautiful and long and fluffy as Emily’s, haha. But I mentioned earlier that I grew up in rural Kenya, so life was very reserved. I was born in a family of three girls and two boys, and my dad and mom. I grew up in a family where we did not define a boy and a girl, everyone was just a child of the family. In my household, we did not have gender roles, so when I was growing up I saw my dad doing the chores, cooking for us, taking us to school, and things that would be done outside our home done by women. And my mom was the one who used to go early to work and come home late. And my dad, because of his time, he would be the one taking care of the family. We also had some people who helped us. So because of that, I had my own kind of bubble thinking that there’s that freedom. I didn’t know about the Free to Be You and Me album, haha.

ENJ: You’re a little younger than I am, Kazi.

KM: Yeah, that’s right.

AA: What gave your parents that egalitarian ethos?

KM: Yeah, I wouldn’t know exactly, but what I know for sure is that my dad does not ascribe to any religion. I don’t know if he was born Christian or Muslim or whatever, but I know that he’s never gone to church unless it was for a friend’s funeral. Perhaps growing up as just a human being created that understanding of “we are all humans, so we should treat each other with respect.” And then for my mom, I think also it’s just values. One of the things that I would say for sure is that if you read the Bible, you can choose to believe what you want to believe. She was born in a family where her mom was a church leader and she made a lot of mistakes. As a young girl, she got pregnant out of wedlock and she was secluded by her mom and her family because of that, and she went through so much pain. I think that because of that, perhaps she thought that she would lead a different life and not really ascribe to some of the things that are hurtful because her mom could have accepted her even when she had made those mistakes, but she was forced to be alone and outside. Not outside completely, but she had to find her own space and take care of this child that was not a legitimate child, or something like that. So, perhaps that created a different value for her and how she would bring up her children. And I’m super grateful for that because I see the world in a different lens.

AA: Yeah. Amazing.

KM: My dad created such a beautiful home environment, and then, I told you that I couldn’t go to school for seven years. That was caused by the IMF and World Bank adjustments that they put on the developing countries. So in the mid ‘90s to late ‘90s, my government went through their structural adjustments by the IMF and World Bank, which is happening right now in this year. And that’s why there are a lot of riots and protests in my country. And more and more of the young generation, the generation that is after me, Generation Z, is angry. Because the parents are not doing anything, perhaps they’re just used to being in oppression. But these people are like, “We’ve seen our grandparents, we’ve seen our parents, we’ve seen our aunties who have gone through these challenges and we’re not going to allow that.” So, both of my parents lost their jobs because of that structural adjustment. Because of that, now I understand it was depression. My dad went into depression and he just woke up one morning and packed his clothes and left. He left my mom with a one-year-old baby, my last born sister, and my mom was confused. She didn’t know what to do. So she at some point left the house that we lived in, and by the time she came back, we had lost everything and we had nothing.

That was also the beginning and awakening of me experiencing the patriarchal things like women who experienced rape. I have never been raped, but I have experienced those attempts three times in my life from the age of, I think I was around 11 to 15. There was a time that I was with my mom and we’re going to the farm and there were two men, one ran after my mom, the other one ran after me. I was young and I screamed and ran and that helped both of us and we were not assaulted. But I have seen things that I didn’t know about when I was growing up. So even as I was navigating life, those seven years were really difficult for a young girl of 13. I started living alone because my mom, because of the challenges, had to get married to another person that I didn’t really link with very well. I didn’t like his values. He was the kind of man who had to be macho, so the opposite of my dad completely. He wanted girls to be home at this time, he wanted women to be the ones cleaning the house and doing all those things. I did not grow up seeing those things, so I became a little bit of a pig-headed or hard-headed girl. And I was like, “You know what? I’m going to leave the house. I can make my own money. I’m not going to school anyway.”

So I left home when I was 13. My uncle was so angry at me, but there was nothing he could do. From the age of 13 I started working and I experienced a lot of those gender imbalances. Because I’m a girl, I’m supposed to do some things. Because I’m a girl, I’m supposed to give free sex to people, and I’m just like, “What?” Or, “I can make you rich, you can get out of this poverty cycle. You have talent so just do this and that.” I remember challenging a man, I think I was 15 and he was trying to approach me and I think he was in his forties. I was like, “I’m just like your daughter, you know?” And I said something that really hit him hard because I was like, let me say Amy, “If you heard that there’s a man your age talking to Amy in the way you’re talking to me, how would you feel?” And immediately he was so angry and he kicked me and hit me so hard. Because one, I’ve mentioned his daughter, and two, I should not bring his family into this conversation. And I was like, “Wow, so that’s how you feel. Then I would like you to treat every woman you see as your daughter.” And of course we didn’t talk from that point, and then later we did, but I started realizing that men don’t treat other women outside their homes the way they would treat their daughters. And sometimes, not all men, some men also assault their own children. It was a community where I was growing and realizing that it’s not as beautiful as I’d thought as a child. And you see these challenges everywhere, so you realize that there’s so much work to be done. So doing this work with Emily and other organizations that are doing this work to change the norms is so exciting, and I’m hoping that we will move the needle, Emily. And even using the tool that has been the tool of oppression, the Bible, I believe in the Bible. I read the Bible and I see God’s different forms and I believe that there’s a lot of healing within it, but it’s about how we use this tool. I’m excited to see how we can use faith in the intersection of gender to actually change this culture. So, that’s a little bit of my snippet of the story.

ENJ: An amazing Girl Child Long Walk story, truly.

AA: Yeah, thank you, Kazi. Wonderful. Well, thank you both so much for those stories. I do want to get into the background of this video. You both caught us up to the point where you’re doing work in the world to prevent girls from being treated in this oppressive way and to empower them. What hatched the idea in your mind? What was the impetus for creating this video? And then I’d love to know also, to set the scene for the video, if there’s a specific cultural context or time period to the Girl Child.

ENJ: Sure. Well, why don’t I answer first and then, Kazi, you can add anything. As I shared, there are layers to the backstory and impetus as I shared. For me, encountering this intolerable status quo of normalized gender based violence around the world, seeing that it’s basically a global pandemic but it’s kind of shrouded in traditions and holy beliefs that seem so proud, and putting my own story in context of the world and history is a backdrop on my own learning curve. And as I shared, seeing the needle go backwards everywhere, I wouldn’t be doing this if I felt like things are slowly moving forward. But as I was engaging in the philanthropic humanitarian way, I was getting around the world and I met all sorts of amazing women’s rights leaders, leaders of NGOs, and many described that the needle was moving forward for women and girls, like in the seventies, like I was describing. But, dot dot dot, the needle has been going backwards, not only for women’s rights, but also for democracy and freedom. So, that’s the backdrop of the whole project, Girl Child Long Walk, and we couched the project in “the long walk to freedom”, Nelson Mandela used that phrase, and many have, that as a human family we’re still walking this long walk to freedom and we have a lot of work to do. There are a lot of mountains that we still need to move. That’s the backdrop for the Girl Child Long Walk project.

I partnered with Reverend Domnic Misolo, an Anglican priest from Kenya, to write what became an ebook, The Girl Child and Her Long Walk to Freedom: Putting Faith to Work Through Love to Break Ancient Chains. It was first released in 2017 as kind of a reading journey that began on International Day of the Girl in October and ended on International Women’s Day in March, and the whole idea was to walk in the shoes of the girl child, really to walk the Exodus path. The Exodus path in the Bible is kind of the meta narrative of the reading journey. And we use a lot of images and quotes to make it more bearable to go on this journey, because, as you know, Amy, it’s soul-wrecking to turn the page back and to see how the human family, which once lived more in partnership, began to treat women and girls basically like slaves in their own family. For me, I kind of fell into a black hole as I was doing the research for this writing, and I wish I had your podcast then, Amy. But I basically began to see, as I’ve heard you say, my own story in the 1970s in the US in the context of this very ancient oppression, which lives on like those Russian dolls within all other oppressions. And it’s so ancient, it goes back to pre-civilization, so it’s a very hard story to tell. It’s not accessible to your average person. And I tried, with Domnic, to write this story to gain awareness and to look even at our own faith traditions that the Exodus path that we see in the Bible, women were not fully included in that. There’s a lot of reckoning we need to do.

Then, in the throes of writing this and getting it out, I think we had about five cohorts do the reading journey and we turned it into a fellowship, and now we have some side projects. But as I was writing this, like I said, I fell into a black hole. And I thought, “This is so hard. This is such an ancient story, it’s so hard to tell.” I had tons of feminist books, archaeology, sociology, books about Eve, the church fathers and how misogynistic they were and how they shaped our theology that we now have today in our theology books. And I really was just frustrated because it’s not that accessible. And the people who did the reading journey are amazing. It’s a deep dive. I had been seeing these explainer videos online and I said to one of my colleagues, “What if we were to try to create an explainer video that explained the origins of patriarchy and how patriarchy is still encoded in all of our cultural and faith traditions?” And the person liked the idea and one thing led to another. We found an animation artist, we formed an advisory board, and voila, we have this beautiful video, which we really see as a tool for families to use, for NGOs to use, nonprofits, churches, anyone who wants to examine how all these traditions came to be, which are still very present around the world and in the US as well. Some places you see a more hardened patriarchy than the softer patriarchy we see in the US where we try to say, “We believe in equality, however, the man’s role is to make all the decisions in the family,” and such things like that.

It was a really rewarding process with this advisory board. We tried to come up with, and I think we did come up with, an arc of this story of how patriarchy arose without wading into all the academic minutiae. We wanted to tell a story that was accessible to your average listener. So that was one challenge. There are so many historical theories that when you turn back the page of any social structure you can get lost in “No, it’s because of this or that.” So we landed on what we hope is a very accurate and accessible story to tell. And another challenge was coming up with a girl child that was cross-cultural and that anyone could relate to. I think we did that pretty well. And as you said, we have all these new translations. Do you have anything else to add, Kazi? She wasn’t there when we created the video, but she’s playing a very important role now in getting the video out into the world in all these new translations.

AA: Yes, I’m excited to hear about those new translations. Can you talk about how this has happened, and then your hopes for the reach of the video, Kazi?

KM: Yeah, sure. With the ebook, one of our fellows from Brazil was excited to see how they could translate this. But let me start from where it started. The video was created and it started moving around, and one of the ladies, I think she’s from East Africa, went to see this video with some girls. And these girls were like, “It would be beautiful for this girl child to speak Swahili, our own language.” I think it hits home when someone is speaking your own language. And I would add something here that is not about the girl child, but it was easy for the colonizers to colonize communities because they came and learned the language. And they also transferred their languages to us. I’m speaking English today, but I wasn’t born in English. I think one of the biggest things that you could do in life is to allow cultural transformation, and one of the things that everybody did so well with this project is to translate this video into different languages, to really allow people to take this and own it and make it their own by translating into different languages. From the Kiswahili translation, this started just flowing from one language to another. People started approaching us, so what we did on the website is we placed this amazing form, if you’re out there listening, you can actually access it. And if you want to translate the video into Chinese, Mandarin, into Hindi, into any language that you speak, you are welcome to go on our website and click that form if you would love to translate this video.

We already have 12 languages across the world and we’re in the process of translating it in Kinyarwanda, which is super exciting. The reason why we’re doing this is because we started this initiative with the watch parties and we invited some of the partners from Malawi, Congo, Honduras, Tanzania, and other countries, and one of them is from Rwanda. He realized, even though in Rwanda they speak French, not everyone actually speaks it because it’s the language for the elite and those who are educated. So translating this video into a common language, the mother tongue, would be much easier for interaction and learning. So here it comes, Kinyarwanda, because of the watch parties. We’re super excited to see children in Rwanda, women in Rwanda, men in Rwanda interacting with this video and learning, but also making it something that can spark conversations.

the church fathers and how misogynistic they were…shaped our theology that we now have today

Through this watch party, we have an amazing campaign that we are calling “How do you say ‘patriarchy’? How do you see it, and how do we change it?” It’s an amazing three questions that provoke conversation. How do you say “patriarchy” in your own language? Perhaps they don’t have the word, so that would be an aha moment for them. And it’s there, it’s a thing that we’re experiencing, so, how do we see it? And from the video, I think it enlightens people’s eyes and they’re able to see this culture talking about, like, “I go to church and I’m not able to speak,” like the case of Emily. When it comes to me doing chores like Kazi, this girl is experiencing the gender imbalance where their brothers are playing outside, and you hear the one who is cooking and doing dishes. That has been the story of many girl children in the world. It’s a very beautiful interactive space for conversation. So, how do they see it? They see themselves in the story. And how do we change this ingrained culture that has been with us for so many centuries? I’m super excited to see what people have in mind. And if you’re there listening, please join the campaign. Let’s hear how they say “patriarchy”, how you see it in your own community, and how we can change it together as a collective.

ENJ: I just wanted to add on that the second translation into Portuguese was by this woman, Ligia, who found our video, like you, by searching online. She was doing some editing and she kept encountering this word “patriarchy” and she didn’t know what it was. So she Googled “what is patriarchy?” and she found our video. And at that point we didn’t even have a way for anyone to reply to us online to translate it, but she sent us a long video about her own story. I think now she’s in her fifties or sixties, but she described how discovering the word gave her something to make sense of all these norms and traditions that impacted her childhood, her adolescence, her marriages. She had been through a few marriages because she couldn’t accept the patriarchal norms, and now she’s doing this really awesome work.

It was so heartwarming that she found us and, you know, if you don’t have a name for something, you can’t really understand what it is. And a big purpose of the video and the reading journey, the whole project is to see all of these branches of patriarchal oppression as part of a living system with deep roots that live on in our own faith traditions and in our imaginations and our hearts and minds. I think the sad thing is that we all have been so indoctrinated by patriarchy because it’s thousands of years old and really coded in the very traditions and faith communities where we find our own belonging. For girls, for women, for human beings, there’s a sense of betrayal that these very traditions that we love in many ways, have this underbelly. And it’s very hard to work within a faith tradition that many people leave, which I totally get, but if you’re staying within your faith community, there are a lot of contradictions we’re all navigating and it’s very sensitive and brave work.

AA: I’m excited to actually watch the video. Again, it’s very short, so for those of you listening, you can just listen to it. And those of you watching will have the video right now, but Emily, would you like to tee it up for us and kind of set the theme?

ENJ: Sure, thank you. In everything we do, we often start with this opening prayer or meditation, so I invite you now to just close your eyes and breathe a few deep breaths to quiet your mind and your heart. Feel the breath of life breathing you into being, and be grateful for your life journey. Now I invite you to hold a girl child you know and love in your heart. Feel her presumption of equality, her free-spirited sense of exploration and curiosity, and her quest to spread her wings and fly. I invite you to hold your own life journey in your heart, your childhood presumption of equality, and all the obstacles you’ve encountered and the opportunities to create change and create a world which we all deserve as a human family. I invite you to keep this girl child you know and love in your heart, and your own journey in your mind and heart as you watch this video.

AA: I’m ready for the journey! Oh, I love it. I love that video. It gives me chills every time. Amazing. It’s such a powerful, powerful film. I love watching it. And there are so many important points featured in the film that resonate every time. I just wondered if you could choose a couple that you’d like to highlight, maybe each of you could choose a couple and share why they stand out to you and how they resonate with your own experience.

ENJ: There are so many points for me. When I started engaging, after we started our foundation, and was in the black hole of my heart trying to make sense of how the world could be this way, I found myself having offline conversations with women working in NGOs. Many of them were really impressive, had advanced degrees, and were doing incredible work. I remember one, on a bus, it was a young woman who worked for World Vision in Tanzania. And I asked her what it was like for her to grow up as a girl, and the theme that I got from that story and multiple others was just how hard girls work. The overwork of girls, it doesn’t sound as bad as sexual violence by older men, blah, blah, blah, but it really impacts the day-to-day life as a child. This woman named Esther shared how in her family, the girls woke up early, they made all the food, got the house ready, and they went to school – luckily, their father let them go to school – but they had to be back early to make the food with their mother, serve the food, and they were up until really late while the boys and the men went to sleep. And I’ve heard that story over and over again.

A woman named Annette in Uganda, I just asked her, “What was it like growing up as a girl where you live?” And she said very simply and kind of in a chilling way, “Growing up as a girl means you work from morning till night making everyone else comfortable.” You know, stories like that. You see this everywhere, like the video shows boys going to school and playing soccer on the street and girls being invisible and having to carry a huge load that is invisible. And that steals childhood from them. That’s one that, whenever I watch it, I feel that very deeply.

AA: Kazi, what about you?

KM: Yeah, I’ll bring the story of my mom. She’s such a great mom, the big icon in my life. For me, when I was listening and watching this video, I liked the phrase where it says that she finds that women are treated differently and you find that the women are carrying the heavier burden. When my dad left, I saw that from my mom. She had to bear the whole burden of bringing up five children. And one big instance is when she went to her family to seek help from her elder brother, and I was a little girl seated there listening to their conversations, because I grew up in a family where you’re not told to run away when adults are speaking. I heard my mom talking to my uncle and saying, “I need help to see how I can organize my life again.” And my uncle was like, “You were married and you decided to not be married. So, as a woman, you’re supposed to be in your family with your husband taking care of you and not coming back to your father’s home to seek help.”

And I was super surprised. I was like, “Uh, when do women get the support they need in their homes and in their families? Does it mean that if you don’t have a husband at home then your life is just doomed?” I think that was the reason why my mom ended up getting married to another person. One, to hide that shame that you are unmarried. So you should bring another man because then people will not call you a prostitute when you’re working so hard to take care of your family. And also, people will not invade your home because then you’re vulnerable and you don’t have a man to protect you. While my father was a very amazing person, I feel that his leaving our home really opened my eyes to see how vulnerable women in our society are.

AA: Would you each like to share one more? Does that work? Emily, how about you? What’s another one that stuck out to you?

ENJ: Again, we could delve into so many of these points and I encourage all of your listeners to slow down the video and just ask, “Where do I see this in my own context?” The pervasive theme of the video is that girls are less valued than boys. So in the Girl Child Long Walk project, we like to talk about the honor gap that we see. In a lot of churches that I’ve been in there are women in leadership, but I still remember this one woman saying, “There’s still something in the air that we need to let out of the windows, out of the vents.” I think it’s really this ethic of male honor that, you know, we masculinize God, and what you value is what you deify.

And around the world there are so many traditions which still shame and blame women for problems that are created by men. You see widow stigma, maybe I’ll highlight that as exemplifying this. Widows in so many places are still blamed for their husband’s death, when, often, during the ‘90s men were dying of AIDS and women were blamed for this. And then they’re sort of tossed aside and seen as almost like orphans and not having any value because they’re not part of a patriarchal family unit. One thing that I see in the video, still in all the manifestations of patriarchy, is a fundamental dishonor of the image of God in the female path of the human family. That’s a big part of the reclamation that the video is inviting people to go on.

KM: And perhaps I’ll just add, not really an example, but it will come with an example. It’s just realizing that we’re in 2024 and you would think that with all the learning and technology and the open space, you’re in the US and we’re speaking right now on Zoom, so that means that I have access to a lot of knowledge from different countries and cultures. The world will change, but these things are not changing. They’re still somehow backward, you know? The realization when Emily woke up one day and was like, “Oh no, we’re still moving backward instead of forward.” For me, it was just recently when I witnessed a really distressing event. A woman was assaulted right outside my compound, and what I saw is how the response to help her was so slow. We waited for her to be supported for an hour, for the police to come and the medics to come, and I was like, “Could this be so if it was a man or if it was a man of importance?” And people there were like, “Oh, it’s this crazy woman who walks around–” No, no, no, it is a woman. It is a human being. I was so angry. And at that point, I was like, “Wow, when do we change this culture where we should see human beings as human and not as a woman or a man first, and then help them and give them that response that they need immediately?” Even though we’re seeing some changes in some areas, there is still a lot that is not changing.

there are so many traditions which still shame and blame women for problems that are created by men

I’ll bring it home to you who are in the US right now. One thing that we’ve seen in these political rallies right now is how, because there’s a woman running to be president, she’s being bashed and being brought down. One disturbing word that I heard Kamala being called is a “childless cat woman” because she does not have children of her own. So my question is, do you become a woman because you have children? Those are questions that we all should ask, and I think this video gives us an opportunity, a multitude of opportunities, to do that.

AA: Yeah, for sure. There’s one phrase in the film that I’d love to hear you both talk about, which is where, kind of toward the end, the girl says, “But I don’t want to turn my back on my family or my faith.” And that was so poignant for me, that resonated with me personally because as I started waking up and seeing the patriarchy in my religion and in my family and in my community as well as broadly all over the world. I think that one of the most painful parts for people is sometimes the choices that you make as you say, “I’m going to do things differently.” Whether you choose to leave your faith tradition or stay, those different choices and points of differentiation can hurt those relationships that you cherish, and it’s all bound up together and very hard to separate out. So I wonder, both of you mentioned still being women of faith and you’ve stayed in the Christian tradition, and I wonder if you could talk about that a little bit.

ENJ: Sure. That’s a lovely way to end our conversation. As I described, I do feel like I had something at the ground floor of my soul personhood that enabled me to dissent from the beginning. And it still impacted me, I don’t want to minimize that, but I see many others who maybe don’t have as strong of a foundation in their own consciousness. I just wanted to share this as an example of it. My daughter is 22 and we’ve been to some weddings of young adults that are getting married, and of the four we’ve been to recently, two of the four had very patriarchal vows. One had the word “obey” in the woman’s vow. In the other, the groom and the bride were invited to share one Bible verse almost as their vow, and, not surprisingly, the woman chose “Wives, submit to your husbands as unto the Lord” as her main vow.

With the younger generation, I think many don’t really know what these words are attached to, but I was sitting at this wedding under this beautiful tree and I felt like she doesn’t know what she’s saying. She was part of this group at her college that was led by someone in one of these patriarchal church plants, and all her friends were in the bridal party. But from what I know of her as a child, I would not have imagined that, so I just felt compassion for her. And she’s kind of symbolic of other young women who grow up in a faith community. It’s not easy being a dissenter. And with women’s issues you get stigmatized, and some of us haven’t minded getting stigmatized, but I feel like that mother bear wanting to protect young women at the prime of their lives, when they should be spreading their wings. And she still is, but there are all these contradictions that we’re all tangled up in.

I feel that for many of us, faith is very emancipatory and it’s at the core of our personhood. I personally think that the way we define faith is a little off. I don’t think it’s the set of beliefs or the shell of beliefs around it. I think it’s more of this existential connection with life. Anyway, we deliberately created the video in that spirit to encourage people to have faith and be curious. You can ask questions. I think that many people are doing that, but it’s not easy, so I feel a protective soft spot. And for anyone listening, some of the things in the video can be a little like, you know, raise your dander, but continue to listen to your own consciousness, give yourself permission to be curious, like the girl child, and go on a journey. Follow your own intuition, your own curiosity. It looks different for everyone, but by doing that, know that there are many dividends for the next generation and others around you, and for all these really intractable humanitarian problems we’re all working on, faith is a powerful lever of change and that’s why I still have faith in faith.

KM: Right. For me, I look at the world and my faith and I think I still believe so much in the Bible as knowing something. Because when you know the truth, it’s kind of like finding light. I would say that the Girl Child and Her Long Walk video represents the beginning of a much larger journey. A journey towards equality, freedom, and empowerment for every girl. I think this path is one of the ways that we could move forward together. And as Emily has shared earlier, this project was born from a deep desire to see real change in the world that we live in. I would say that it’s not just about the video, it’s about the entire reading journey that we have on our website that accompanies it. And the journey is also a resource that is available for anyone who is curious like myself and Emily and passionate about making a difference, to come and join the community and share the stories and use these resources and tools to challenge and break patriarchal tradition. I think that would be an amazing start or continuation of this journey, and our hope is that people will watch this video in their own languages that resonates with them. And also that they will consider hosting watch parties in their communities and gathering communities, whether in schools or churches, and then engage and invite others on our social media.

Follow us on X, Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and explore these various spaces where we can learn together. You can find us on Instagram @girlchildlw and on LinkedIn you can find us at The Girl Child & Her Long Walk to Freedom. Our website is girlchildlongwalk.org, and then lastly on X we’re @GirlChildLW. I think we perhaps are the only ones who are called Girl Child Long Walk. And we look forward to sharing this wonderful video with you. Again, I want to mention that if you’re interested and inspired to translate this video in your own language, please don’t hesitate to reach out. People can send us a direct email at info@girlchildlongwalk.org. If you’re inspired by the work we do, we also have a Long Walk fellowship that we invite people of all traditions, faiths, genders, and from all across the world to go on our website and look and learn, and then perhaps you can apply for the next cohort that is coming up in 2025 and 2026. Join us and let’s explore how we can change patriarchy. Ultimately this path is to move forward together so that we can build and change the world as women. But also, I hope and I believe that not only women are listening to this podcast, but also men, because it’s not our work as women, it is our work as humans.

ENJ: I want to acknowledge that if you’re on this journey already, it is painful, and there are times when you just want to close the books and not keep asking what’s going on here. So for those who are already on this journey, make sure to take care of yourself and to find a community where you can really navigate and wrestle with all these contradictions with others who are on the same journey. We try to do that in the Girl Child Long Walk community, and we invite you to reach out. There are many ways to plug in. Another point I’d love to make in closing is to just keep digging deeper. You might be on this journey and you counter one layer of patriarchy, and for many evangelicals it’s learning to read their Bible in a way that supports women’s equality, but then as you keep digging, there are more traditions and more beliefs. And for me what has been really emancipatory has been digging into my own soul, the inner path of faith, which you can find in all of our world’s faith traditions, I believe. And it’s a more internal faith that doesn’t rely so much on externalized false certitudes. It’s a little bit more murky. It’s also more connected with the natural world, it’s called the wisdom traditions. So if you’re on this journey, keep digging and look for what is truly emancipatory within your own tradition and allow yourself to be curious and look outside of that tradition as well. There’s a lot in our shared human journey that we can all benefit from.

It’s an amazing story that we’re all a part of, and the long walk to freedom is not done yet. We need to keep bravely navigating the contradictions and asking, “What is mine to do?” And if you do that, it will be a joyful process that will have dividends really intergenerationally. Because we have to work not only for ourselves but for the younger generation and in honor of the older generation, our mothers and our foremothers who have done a lot of work for us, including within the Christian tradition and within all our faith traditions. These pioneering women don’t appear in our history books or religious books, but they have paved the way for us, so let’s just keep walking by faith and looking for the light, like you say, Kazi, and there is a path we can all walk together. I’m really grateful to be here with you, Amy, and I feel such collegiality with your work. Thank you.

AA: Thank you again, Emily and Kazi. This was just a joy doing this interview and learning more about your work. Again, I would direct listeners and viewers to girlchildlongwalk.org to see all of these videos and, like you said, the reading resources. You’re doing such wonderful work in the world. Thanks for being here today.

KM: Thank you so much for having us, and we are super excited to be part of this conversation.

ENJ: It was a real joy and honor to be here with you today, Amy. Thank you so much.

find a community where you can really navigate

and wrestle with all these contradictions

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!