“Colonialism demands the extraction of value from women as a commodity”

Amy is joined by Levi Murray to discuss the tricky intersections between patriarchy and colonialism in Mexico, plus a deep dive into the female archetypes of La Malinche, La Llorona, and La Virgen de Guadalupe.

Our Guest

Levi Murray

Levi Murray is a half-white, half Mexican-American anti-patriarchist. A dentist by trade, he is currently pursuing a Masters of Theology with a focus on Feminist Theology. Levi has the fortunate of being married to his best friend, Barbara, and together raising four beautiful children.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In March of 2022, my daughters and I decided to go to Mexico City for their spring break. We all speak Spanish in our family, and we’ve spent lots of time in Latin America. And Mexico City is one of my favorite cities for the art, architecture, museums, and food. It’s an amazing city. So I knew the girls would love it, and they did! And one thing we noticed right off the bat as we arrived was that there were these huge plastic barricades around museums and around the presidential palace, and we noticed lots of graffiti with slogans about sexual assault and murders that had happened in Mexico. And one day we were talking with an architecture student about the current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and we asked this architecture student what he thought of the president. And he said, “Well, the president is a champion of the poor, so we like him for that reason. But he is not supportive of women and that’s why there are so many violent protests.” And he said, “That’s why you have to be careful in the capital during the next couple of days.” And we’re like, “Ohh, okay.” So we started putting the puzzle pieces together, and as we talked with more people, we learned that the previous year on International Women’s Day of 2021, there had been massive protests, among the biggest in the world, in Mexico City. And that there had been violent confrontations between Mexican women and police, and many, many people had been hurt. So, hence the big barriers on the iconic buildings that signified presidential power.

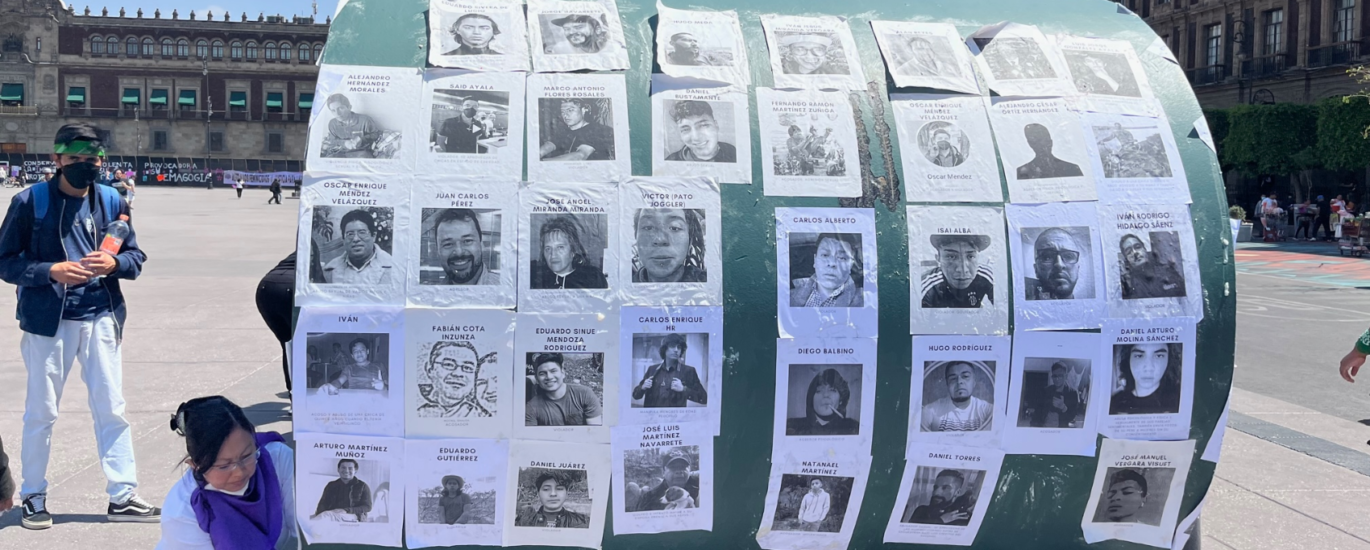

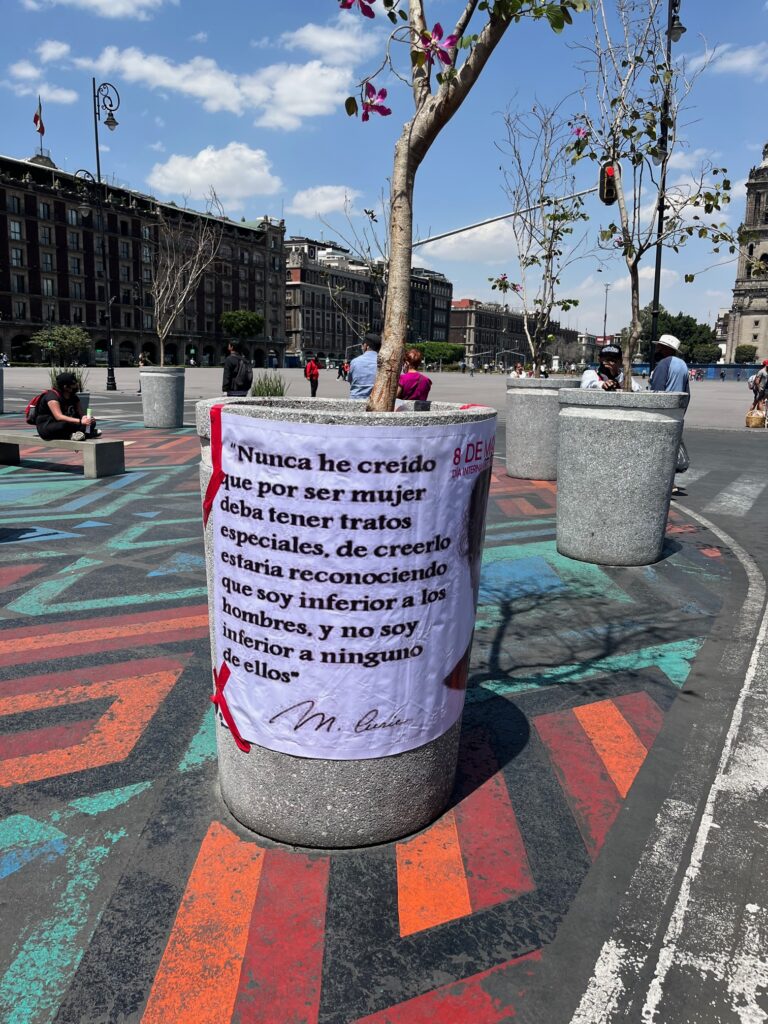

Well, International Women’s Day was the very next day. Just by coincidence we were there for that exact date and our hotel was literally on the same square as the presidential palace. So I took my phone around to take pictures and to take video as thousands of people streamed into the capital to protest. And hundreds of police showed up with a really ambivalent presence in the city. It felt half like “we are here to protect you” and half like “we may attack you” and you’re just not sure which way it’ll go. Those videos and photos that I took in 2022 are on the website this week, if you want to take a look at them. And I’ll just say it was one of the most moving experiences of my life as a feminist to see so many people, and particularly so many men, in the zócalo, the square in the middle of the capital. So many men that day supported women. There were men there putting up posters, setting up microphones and speakers and holding signs, and holding the hands of their wives and sisters and their moms, and holding their daughters on their shoulders. It was a beautiful sight to see Mexican families, all people, regardless of gender, coming together in condemnation of misogyny. And in condemnation of gender-based violence and calling for gender equity. And that is an experience that will inform today’s episode. And in that spirit, I want to welcome our guest today, Levi Murray. Welcome, Levi!

Levi Murray: Thank you so much, Amy. I am so pleased to be with you. I’m a big fan of the podcast and the journey you’re on, and I’m excited to accompany you and the listeners today for this episode.

AA: I’m so, so happy to have you here with us. It’s been really an amazing experience to be in correspondence as we’ve prepared this episode and to hear your point of view. I’m always really grateful and excited when we have men participate in this process. So, thanks so much. And I’m wondering if we can start the episode today by having you tell us about yourself and what brought you to this topic?

LM: Absolutely. I consider myself a person in process. I was born and raised in New Mexico, raised by two loving parents along with my three sisters. I’m half Hispanic and half white, and my home was a mix of those two cultures. My mother’s parents are first generation Mexican-Americans and they lived in the Houston, Texas area. And I also had an opportunity to live in Mexico for a couple of years, where I was able to more fully appreciate the culture and the language and even serve in some areas where some of my ancestors were from. So that was a neat opportunity for me. I’m a dentist by trade, but theology is really my passion and my hobby. And I am fortunate to be married to my best friend, Barbara, who actually I have to thank for connecting me with you, Amy, and your podcast. And we’ve got four beautiful kids.

AA: Awesome, thanks so much. Yeah, thanks to Barbara, too. That’s really great. I sometimes hear from people who have listened to the podcast or participated in it as whole families, and it makes me so, so happy. Can you tell us a little bit about what brought you to a podcast called Breaking Down Patriarchy?

LM: Absolutely. I was immediately intrigued by the title because I consider myself an anti-patriarchist. So when my wife referred me to your podcast, I was immediately interested to know what this is all about. And ultimately, the way I came to identify as an anti-patriarchist is a bit of a long story, but it came down to some experiences I had where I was able to recognize that I had inherited some blinders that invalidated the lived experience of people whose experience didn’t resonate with mine or with the rubric that I’d been given by which to evaluate truth. So to open myself up to everyone’s lived experience as equally valid and valuable was incredibly liberating and really life-giving. For me it really took all the pressure off of needing to be right as it shifted the definition of right away from moral finality and towards relationality. And for me, that really is the Jesus way.

AA: Hmm. Can you explain just a little bit more about that concept of shifting away from moral finality toward relationality?

LM: Yeah, so historically, if we look at the history of Christianity, the periods in time where the Church really centered on moral finality – who’s right, who’s wrong – which inevitably becomes a discussion of who’s in and who’s out, the Church ended up making really terrible decisions. Things like conquests and inquisitions and banning specific groups from being able to participate in different ways. And we don’t see that when we look at the life of Jesus. Jesus didn’t seem to care about those boundaries and was more centered on relationality. Being in relationships always overruled what would’ve been considered morally wrong or people who were outside. We see it over and over with the tax collectors and the sinners that Jesus hung out with, and he equally spent time with the Pharisees. And so when we center the relationship over needing to be right, I think we’re actually being more like Jesus than if we were trying to enforce a specific moral code.

AA: That’s beautiful. Well, I’d love it if we could talk about the meat of our conversation today by having you give us the lay of the land and talk about some key issues in gender dynamics in Mexico and/or Latin America more generally.

LM: Yes, thanks for asking about that. Patriarchy is the same animal, but it just has a different name in Mexico and in Latin America. It’s called machismo. And unfortunately, there’s frequent violence that is the fruit of that ideology. UN studies estimate that 50% of women living in Latin America will experience violence as a result of that ideology. To give you an idea of what the mindset is like for many people, in 2014 there was a survey of Brazilian men and women that revealed that 65% of people believe that women wearing revealing clothing deserve to be raped. Also, you mentioned a minute ago the current president of Mexico. He was recently quoted as having said that 90% of calls to abuse hotlines are fake. So it’s just in the water, where there is a mentality of male dominance over women as being appropriate and women’s submissiveness also being expected.

There’s a spectrum of violence against women, as you know, that ranges from passive microaggressions all the way to gender-based murder, known as femicide. Femicide is defined as murder by an individual or individuals of a woman that is motivated by her sex and tolerated because of her sex. This is in conjunction with an idea called feminicide, which is state supported murder of women, whether it’s through active perpetration tolerance or omissive practices. And this is really a big problem in Latin America. There’s an exceptionally high concentration of femicide. Of the top 25 femicidal countries in the world, ten of them are in Latin America, and this is only what gets reported. Many nations don’t compile gender statistics for murders, and many don’t report murders of migrant people as murders. So it’s much likely worse than what we can currently quantify. Specifically in Mexico, data ranging from 2018 to 2020 reports an average rate of femicide of ten per day. Ten women per day are being murdered. And these cases are often downplayed or ignored by the media and local authorities. They’re treated like isolated incidents, it’s minimized, and it’s not viewed as a systemic issue. And unfortunately, the most common outcome for these murders are that they remain unsolved, which ultimately means no action was taken. So it’s a real problem.

It’s easy to sort of be tricked into thinking that there’s been progress. There’s a mirage of progress because there have been some advances for women in the political arena in recent years in Mexico and in Latin America. But even with this advent of female political leadership, the femicide and the violence hasn’t stopped. I think the reason for this is because there’s been no ideological change away from patriarchy. They simply started filling spots in a patriarchal system with women instead of men. And even though women are occupying those seats, men continue to have all the power which lies in economics, as far as the pay gap and access to jobs. Men definitely are still favored in those areas. When pressured, the government will take action. Like recently in Mexico, they enacted a campaign called “Count to 10”, which was urging men to count to ten before taking violent action against a woman.

Patriarchy is the same animal, but it just has a different name in Mexico and in Latin America. It’s called machismo.

AA: Oh my gosh.

LM: But these campaigns are ultimately futile. They’re just empty tactics when there’s no ideological change to accompany it. So instead of being violent immediately, if they take the campaign’s advice, they’ll wait ten seconds and then be violent. Religion, unfortunately, also plays a big role in propping up patriarchy in Latin American countries. Patriarchal theologies are heavily enmeshed with cultural power structures. Historically, Catholicism was the major player there, but as America exports more and more evangelicalism, patriarchy is shifting in Mexico. So that instead of looking like a priest in a black robe, it looks more like a megachurch pastor in ripped skinny jeans with a designer t-shirt. But it’s the same beast.

AA: I wanted to mention too, one thing that I saw in Mexico City on that trip that I mentioned was a bunch of women gathered around this big sculpture, and they were gluing black and white photos of men to this sculpture. And it was a really haunting image, just seeing all of those faces. And I thought, “oh, I think I have an idea of what this is.” But I went over and asked, and they confirmed what I had thought, which was that each of these was a photo of a man who had admitted to or it was obvious that he had beaten and killed a woman. And that each of these men had never had charges filed against them, or they had just gotten off with no punishment. And so these were men who had committed femicide and were out in public with absolutely no consequences. And so these women, because they couldn’t trust their judicial system to take any action, or when they reported it to the police, no action was taken. They were just taking the matter into their own hands to speak up and say, “We know who you are.” And they’re putting their faces out in the capital for people to see. But it was just devastating and really upsetting to see that.

LM: Absolutely. Like you mentioned, there’s been a lot of valiant pushback by women in Latin America and by Mexican women as well. The thing that’s really interesting beneath all these statistics is that femicide and gender-based violence really reveal patriarchy to be a public health issue. If a specific disease process was identified that was killing men at a disproportionate rate, we would immediately throw resources at it to stop it. We do that even with things that are not pathological, like baldness or erectile dysfunction. The amount of money that goes into research for those things is ridiculous. Patriarchy is a woman killer, and if it’s killing half of us, it will ultimately be the death of all of us. There are those who would argue and say, well, statistically 80% of the murders worldwide are of men actually, not women. But when we look through the lens of relationship ideology, of the murders that happen by an intimate partner or a family member, 82% of those victims are women. Only 18% of the murders committed in relationships are of men. 82% are of women. So that’s a clear link between the ideology behind relationship dynamics and the outcome of female murder.

So a place where we can start to try and push back against this would be to identify femicide as a hate crime that is targeting a specific vulnerable population. But again, the criminalization of femicide has to occur simultaneously with anti-patriarchal ideological work, or ultimately it’s going to be futile. When the system is pushed on by the populace to change, it can tolerate a certain amount of change. But ultimately it will revert back to its original programming, which in these cases is patriarchy. And we’ve seen that happen in the United States with the election of Donald Trump, the January 6th insurrection. The system can only tolerate so much pushback before it has to reassert itself and produce the fruit of its original programming. So in this case, without that ideological change, unfortunately our efforts are not going to result in any lasting difference in the long term.

There are a few rays of hope, though. I know I’m painting sort of a dismal picture here. Rays of hope in the world are found in Colombia and in Mexico. In Colombia, the European Union created a school called the National School for the Unlearning of Machismo, and there’s a related program in Mexico called GENDES that’s working to do the same thing. So there is some movement, thankfully, to try and teach a new ideology and bring some fresh perspective to the situation. In my research though, as I looked at a lot of these topics and did a lot of reading, the question would come up frequently: Who’s responsible for protecting the lives and rights of women? Whose problem is this? And typically the government is identified as the one who needs to take responsibility and act. But again, when they fail to be able to enact real change, women resort to things like the posters that you mentioned a minute ago. Ultimately though, I believe that patriarchy is a men’s problem. And this is a fairly recent realization for me, as I was doing anti-racism work and came to understand that racism is a white people problem. I immediately saw the parallel between patriarchy being a men’s problem. The group that’s being oppressed didn’t create the system, and they largely do not perpetuate the system. So just like racism, white people have all the power to make the change. And in patriarchy, it’s men who occupy the position of power to be able to make changes. Don’t get me wrong, women make incredible warriors in this fight, and I am so grateful for my female family members and the female theologians that have helped me see what I’ve come to see so far. But ultimately, it’s my problem. I inherited it. I have been complicit in perpetuating it, and I occupy the position to be able to do something about it.

It’s hard, though, for men to see this because of the concept of victim-blaming or victim-shaming that is so prevalent in our culture. The focus is put on the woman’s appearance and her behavior and not on the system that is creating the demand or the circumstance for that appearance and behavior. This is supported by a lie that we believe, a lie that women are acting with full agency or that they are giving full consent. And there is a book that was published recently by an amazing organization. The organization is called Christians for Biblical Equality, and they published a book called Created to Thrive. And one of the main concepts in that book is that truly free consent can only be a concept applied in a healthy relationship of equals.

AA: Wow. That’s powerful. And that’s from a Christian organization?

LM: Mh-hmm.

AA: Amazing.

LM: Yeah, they identify as egalitarian, so they’re working for women to have equal status within Christian traditions. The book focuses specifically on sexual abuse and other types of abusive behaviors within Christian culture and how to root them out and eliminate them. The idea of consent is an important one when you’re talking about whether it’s even possible to fully consent when you occupy a lower position in a hierarchy.

AA: Totally. Well, that’s what I was going to ask you next, because you read that quote, “truly free consent can only be a concept applied in a healthy relationship of equals,” and I thought, “I want that printed on billboards.” But, I mean, this is your point, I guess. In a relationship of any woman with a man in a patriarchal society, is it even possible to have a relationship of equals? Because if one party is conditioned from the time she’s born to please men, then she may find herself doing things to make the man happy without even realizing it. She might think that what she’s doing is of her own volition and what she wants, but that might be because she’s been conditioned to want to be a helpmeet instead of a sovereign human being. So is that even possible?

LM: I don’t think it is. And I think I would flip it around the other way and look at it and say that men also are not actually able to do what they want. Because we are boxed into a specific sex role that we’re socialized to, and it doesn’t even occur to us that we could be different. And so, yeah, I think it’s just poisoning everyone.

AA: I am so happy that you brought up those initiatives that are trying to educate men and to change things at the root. Because we’ve talked about this so many times on other episodes about the term radical change, meaning from the root, let’s get at the foundations of what’s happening. And I’m so happy to hear about these organizations that are trying to get at the root and reeducate all of us, so that we can create more equity in our society. I’d love to hear some more about the main themes that you’ve researched about how patriarchy and colonialism intersect, especially in Mexico or more broadly in Latin America.

LM: Yes. This is a really interesting area to dig into, specifically when you’re looking at the differences between Spanish colonizers and English colonizers. The Spanish didn’t seem to have the racial anxiety that English colonizers brought with them, and I think that’s at least in part due to the fact that the conquistadores were not trying to start a new nation. They were merely an extension of their existing fatherland, which they were on good terms with, and just seeking more resources for. Versus the English colonizers who came and had a different situation with the nation that they were leaving, and were looking to essentially build a new nation as America sort of took shape. And so racial purity became paramount in the building of this new nation. The thing they had in common was that both of them saw nature and indigenous peoples as resources that needed to be captured, commoditized, and fully extracted for the service of the empire. The Spaniards didn’t have a problem intermingling with the indigenous people and reproducing with them and bringing the descendants of those relationships up and down into cultural circles of power when it was convenient for the consolidation and maintenance of power. Whereas in America, the English colonizers did not do that. And we had things like the ‘One-drop rule’ come into existence where if it was deemed that you even had one drop of African or indigenous blood, then you were not allowed in any of those power circles. So, an interesting difference there.

An area where I was able to identify with, specifically in my research, was that as the Spanish took advantage of the indigenous people and were able to bring them up or down in these cultural circles of power, they fed the indigenous people this lie of individualism and effectively broke them off from the herd of the indigenous masses. And therefore separated them from their plight as well. And in my experience growing up in a largely white culture, I recognize in retrospect that I was disconnected from the plight of Hispanic people in my community. Because like during this period of Spanish colonization, if you were complected fairly enough, if you spoke well enough, if you were resourced well enough, and if it was advantageous to have you in the circle of power, then you were brought in. And if you weren’t, then you weren’t. And that was my experience largely growing up, where I felt disconnected from my Hispanic heritage often because of the predominance of the white culture that was in my area and the circles of influence that I lived in.

With regard to how colonialism affected patriarchy, some scholars differentiate between ancestral patriarchy and colonial patriarchy. Ancestral patriarchy was sort of characterized as low intensity, where it was patriarchal but there were still female images of God, and there was at least a partly ecological belief system where the earth played an important role or was even worshiped. Colonial patriarchy is considered higher intensity, where women, indigenous populations, and nature are all seen as something that must be controlled, dominated, commoditized, and extracted as a resource. And the God image is strictly controlled as male. So when these two forces come together, the patriarchy that’s embedded in Christianity and the patriarchy that’s embedded in colonialism, the result is that the bodies of Latin American women become disputed territory between these two monsters. Patriarchal Christianity demands the subjugation and control of women. Colonialism demands the extraction of value from women as a commodity. So in both ideologies, the bodies of women are controlled, one through containment and the other through exploitation. So if we had a Venn diagram of these two, there’d be an area of overlap in the middle, and I think that’s where we get things like Church sex abuse scandals, and tolerance of predatory behaviors and abusive practices in Church cultures, where the underlying colonial mentality and the Christian patriarchal mentality bleed together, and they both come out.

AA: That is so important. Thank you for bringing those issues to light. And we’re finding, as we do research all over the globe, that so many of these phenomena are common among colonialism, whether it’s in the South Pacific or whether it’s on the African continent, no matter where it has happened. But you’re articulating these threads in such a concise and illuminating way, Levi, this is really fantastic stuff. I also want to ask you specifically about your Mexican heritage. I know that you’ve been digging into that more and looking at some of the feminine icons or archetypes from the Mexican traditions. Can you introduce us to the three Mexican women that you’re going to talk about today?

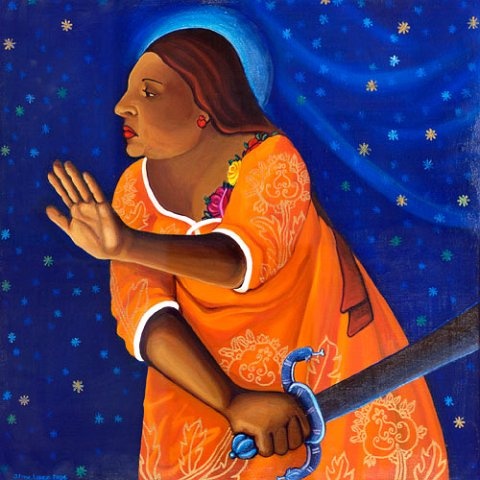

LM: Yes, I would love to. Today we’ll be looking at three female archetypes from Mexican culture. It’s so fascinating to me that all three emerged from or were deposited into the Mexican psyche during the same century. During and immediately after the period of active colonization by the Spanish. I think this is so important to note that these three stories all emerged from the same century because I think it gives us justification to draw a direct link from colonization and patriarchy and the fruit of those actions. These three have so many things in common and so many interesting points that we’ll contrast today. It’s just really interesting to me that they all came out within five decades of each other. One is an actual historical person who was later transformed into sort of a mythical person, her name is Malinche. One is a legend born from the countless experiences of indigenous women, she is known as La Llorona. And one is a religious figure, perhaps the religious figure in Mexico, and that’s La Virgen de Guadalupe.

So the first one to look at is La Malinche, and she’s the archetype of a traitorous seductress. Malinche is the most commonly used name for her, like I said, she was an actual indigenous woman who lived during the period of Spanish colonization in Mexico. It’s thought that her birth name might have been Mali Nali and Spanish variations of that name may have been Malintzin and Malinche. And when she was basically conscripted into service through human trafficking by the Spanish, the name she was given by them was Doña Marina. So she’s known by all those names, but Malinche seems to be the most commonly used. She was born between 1500 and 1505, and she suffered the loss of her father at a young age. She lived in what would be considered the upper class of her community, which was part of the Aztec Empire. She seemed to have access to education and some privilege. After her father died, her mother remarried and had a son, and in an attempt to facilitate his inheritance of their land and possessions, Malinche was sold into slavery and then declared dead to cover up that sale. And that initial trafficking happened to her when she was only 8 or 12 years old, somewhere in that window of time.

As I mentioned, she was part of the Aztec Empire, so she grew up speaking Nahuatl, but she also spoke Tecpillahtolli, which is the courtly dialect of nobility within that empire. Her initial trafficking was to other Aztecs, and then in time she was trafficked again to a group of Mayans. And while with the Mayans, she learned both dialects, Mayan Chontal and Yucatec Mayan. When Cortés arrived in Mexico in 1519 and first encountered the Mayans, he rescued a shipwrecked friar who had been captured by the Mayans. Several years earlier, the friar, named Gerónimo de Aguilar, had learned the Mayan language and acted as an interpreter for Cortés. After realizing that their weapons were no match for the Spanish invaders, the Mayans sought peace with Cortés, and they brought gifts of food, gold, and twenty slave women to Cortés as a peace offering. And among those twenty women, Malinche was one of them. So her third trafficking was into the hands of the Spanish invaders. Cortés had the women baptized and then distributed them to his men as objects for sexual use. This just blows my mind how that demonstrates when colonialism and patriarchal Christianity crash into each other, we have things like this. Where he felt compelled to baptize them, to perhaps save them, and then distribute them as a resource to be exploited. How you can do those two things in conjunction, it blows my mind. But that’s the kind of activity we see when these two ideologies crash into each other.

Soon Cortés and his crew encountered the Aztecs, and that’s when Malinche’s language skills were noticed and she was conscripted into service as a translator. So Malinche translated Aztec to Mayan, and then Aguilar translated Mayan into Spanish. But Malinche was so bright that she soon learned to speak Spanish as well. And she sort of became Cortés’s all-in-one package with language and nobility skills, which in my opinion is a brilliant survival strategy on her part. To make herself indispensable so that she could at least to some degree, protect herself because she was so invaluable to him. As I mentioned earlier, Malechi is considered to be a traitor. And the initial traitorous act that she committed was allegedly discovering a plot to ambush and massacre the Spanish by the Mayans. And when she found out about it, she allegedly told Cortés right away. So Cortés gathered the Mayans and preemptively massacred them instead. Many historians now believe that this story is actually completely fabricated to justify Cortés’s actions, which were more likely an act of proving solidarity with the Tlaxcalans, a warring Mayan faction that would later help him in his conquest of the Aztecs. So we see a classic move by Cortés to divide and conquer and then lay the blame on someone else.

Another reason for maligning Malinche as a traitor and as a seductress was the birth of Cortés’s son by Malinche in 1522. His name was Martín, and he sort of symbolically held up as the beginning of the Mestizo people. And Malinche’s pregnancy with him is seen as a cooperative act. So if we just take a second and remember that there’s no such thing as full consent in any hierarchy, let alone slavery, we can see how ridiculous it is to consider this a cooperative act on Malinche’s part. Cortés and Malinche’s son Martín was later deemed legitimate by papal decree so that he could inherit Cortés’s estate and title. So there we see that when it’s convenient, race isn’t an issue. Malinche died around 1529. At the time, she was married to Juan Jaramillo and she had a daughter named María in 1526. Malinche’s reputation has really gone from one end of the spectrum to another. During the Spanish occupation, she was honored and often portrayed as the ideal Christian woman. She was given basically virgin status. She was a heroine to the Spanish and was described in writings in really praiseworthy ways. Bernal Díaz del Castillo was a soldier during the conquest of Mexico. He wrote, “Without the help of Doña Marina, we would not have understood the language of the New Spain and Mexico.” Rodríguez de Ocaña was a conquistador and he wrote that “After God, Marina was the main reason for Cortés’s success.” And the Aztecs even for several centuries portrayed her in artwork as larger than life, often in extravagant clothing. And she was even portrayed as the one to which the Tlaxcala alliance was made and not Cortés. She was held in pretty high regard during those centuries after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. And conquistadores on several occasions noted that her greatest skill was her ability to convince other natives of what she could already perceive, that it was useless in the long run to stand against Spanish weapons and Spanish ships.

After Malinche was conscripted into the service of Cortés, the Spanish were only forced into combat one more time. So some historians even make the argument that she actually saved a lot of lives. Interestingly though, after 1821 when Mexico won its independence from Spain, Malinche began to be seen very negatively in Mexican culture. Her story transformed into myth over time and has been at times conflated with the story of La Llorona, which we’ll cover next. For many Mexicans, Malinche is seen as the Eve figure of Mexico, the perpetrator of original sin. Which again, if we just pause for a moment and recognize that she’s the one being condemned, and Cortés is not the one considered the original sinner. It’s really revealing of the mentality. Malinchista and malinchismo are derogatory terms based on her name to describe a traitor. Like I mentioned, this is a classic instance of scapegoating when the culture can’t afford to hold a real perpetrator accountable so it condemns someone else for the crime. And as the case is so often, the one scapegoated is the actual victim of the crime.

the culture can’t afford to hold a real perpetrator accountable so it condemns someone else for the crime. And as the case is so often, the one scapegoated is the actual victim of the crime.

One historian summed it up beautifully with his statement. He said, “If there is one villainess in Mexican history, she is Malintzin. She was to become the ethnic traitress supreme.” But for this to happen, we have to fully ignore the context of Malinche’s life. She was betrayed by her family when sold into slavery by her mother, trafficked by her own people into slavery with another people, and then trafficked again into slavery a third time with the Spanish before being conscripted into political service by the empire. And surely her performance is the thing that kept her alive. So this dramatic shift in perspective happened after Mexico won its independence from Spain. She went from being la gran conquistadora who brought Christian enlightenment and salvation to the heathens, to suddenly being Cortés’s traitorous mistress who used her seductive skills to achieve her own ends. And her depictions after the 1820s are often hypersexualized, and the concept of malinchismo is a tool that serves Mexican nationalism and perpetuates patriarchy.

Today in popular media her portrayals range from a cursed woman in horror movies, to a Christian protector of Mexicans, to a duplicitous traitor. In 1997, there was even a spaceship named after her in the Star Trek franchise, Deep Space Nine. Interestingly, there is a home that Malinche actually lived in during her time under Cortés’s domination, and it still exists in the suburb of modern-day Mexico City. It’s located at 57 Higuera Street but there are no markings to identify the home as a historical landmark. One of the current residents of the home was quoted in a recent article about this lack of memorialization, and she said, “For Mexico to make this house into a museum would be like the people of Hiroshima creating a monument for the man who dropped the atomic bomb.” My jaw just dropped open when I read that, how that is so revealing of the incredible cultural disdain heaped on Malinche instead of Cortés.

AA: Oh my gosh, yeah. And you’re right it’s so revealing of the mindset of the people at each period of time that we’re seeing this story through different lenses. And one memorable thing you said that I’ll take with me is that so often the person who’s scapegoated is actually the victim of the crime. Thank you for that. I’ve been wondering on a larger scale about the psyche of the, you mentioned the mestizo people, which for listeners means mixed. So biracial people, when Europeans came and married indigenous people and then produced offspring. And we saw a play in Mexico one time that depicted the indigenous peoples and their religions and their culture, and it was very immersive so you kind of get into this mindset of what life was like pre-contact with Europeans. And then it shows the Spanish conquest in this play and it was so horrifying to watch. Our whole family cried. And I remember the scene closes and then in the very next scene you see Spanish and indigenous people are getting married and having children. And pretty much everyone was Catholic, you know, in the next generation. And we talked so much about this afterwards, after the play was over and just said, I wonder what that does feel like for modern Latin Americans that have that mixed ancestry and that knowledge of their own ancestors? That on one side there were the oppressed and on the other side in their own family were the oppressors. Can you speak to that at all, Levi?

LM: I agree with you. It seems that there is a significant amount of dissonance in the psyche of the Mexican people. One of the ways that this shows up is that monuments depicting Cortés, Malinche, and their son Martín have been destroyed by mob violence when erected. There’s such a visceral reaction to that image. Some historians identify Cortés and Malinche as an allegory for modern Mexico, where they say the Mexican people are the offspring of violent Spanish domination and indigenous collaboration. And this internal dissonance leaves people unsure of how to feel about their heritage, perhaps even about themselves. I would put a footnote on that and say, I don’t think we can say collaboration. I think we would have to say Spanish violent domination and indigenous suppression. But even so, I think there’s a lingering belief of Spanish superiority and indigenous inferiority. And when your only alternative is to idolize the oppressor and disdain the indigenous part of yourself, you’re not left with a part that you can love. So it’s a tough spot.

AA: Is anyone currently trying to redeem La Malinche from being so misunderstood?

LM: Yes. Like so many women from history, none of her records were written by her own hand. They’re written mostly by Spanish invaders. So the work of reinterpretation of her life requires us to enter into our imaginations and seek the voices of the oppressed and marginalized to find insight into her lived experience. Thankfully, feminist intervention started happening in the ‘60s and she began to be understood as a victim who was forced to navigate oppressive systems and make incredibly complex decisions as a survival strategy.

AA: Okay, that’s good to know that the narrative is becoming more informed by these power dynamics that I think people haven’t given enough thought to until recently. So I’m happy to hear that. So, what’s the second archetype that you wanted to talk about today?

LM: Yes, the second archetypal examine is the mythical figure known as La Llorona. Amy, would you mind reading a version of that story for us?

AA: Yes, I’m happy to read it. When you brought it up, I thought, oh I’ve heard that story, and then I remembered it was because I read it in the book Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estés. And I’ll read it from her book.

“A rich hidalgo, nobleman, courts a beautiful but poor woman and wins her affections. She bears him two sons, but he deigns not to marry her. One day he announces that he’s returning to Spain where he will marry a rich woman chosen by his family, and that he will take his sons with him. The young woman is crazed and acts in the manner of the great shrieking madwoman throughout time. She claws his face, she claws her own face. She tears at him, she tears at herself. She picks up the two small sons and runs to the river with them, and there throws them into the torrent. The children drown and La Llorona falls to the riverbank in grief and dies. The hidalgo returns to Spain and marries the rich woman. The soul of La Llorona ascends to heaven. There the master of the gate tells her she may come to heaven, for she has suffered, but that she may not enter until she recovers the souls of her children from the river. And that is why it is said today that La Llorona, the weeping woman, sweeps the river banks with her long hair, puts her long stick fingers into the water to drag the bottom for her children. It is also why living children must not go near the river after dark, for La Llorona may mistake them for her own children and take them away forever.”

LM: Thank you for reading that, Amy. La Llorona is the archetype of a monstrous mother. The earliest documentation of this legend is from 1550 in Mexico City, and it is a cautionary tale for women, for children, and for men about women. Early colonial text provides some evidence that some form of this legend existed prior to the Spanish invasion, but it is most commonly accepted to have distilled out of the dynamic between Spanish conquistadores and indigenous women during the colonial era.

AA: Okay, so what are some important themes from the story?

LM: Well, in all versions of the story María is initially very beautiful. She’s dressed in white, she’s emotionally volatile. She kills her children and is forever a damned, monstrous, murdering ghost. Also, in all the story variations La Llorona is created by some circumstance that arises. Ultimately, the variations always have this in common: María is a danger to her kids, to herself, and to men. So on all levels, females are dangerous and must be controlled. La Llorona is ultimately irredeemable no matter what. She’s abandoned and ashamed if she accepts her circumstance, or she becomes a murderous monster if she rejects it.

Other points of interest to me are that initially her name in many of the stories is María and she’s dressed in white. This shows her starting out as a virginal archetype. In the end, she’s known as La Llorona and her dress is now dirty and ripped and wet, and she failed to maintain her virgin status. The version you read for us made explicit that the Spaniard is physically attracted to María but despises her indigenous blood, and therefore decides to use her as an object of sexual pleasure without marrying her. He then marries a Spanish woman of high social status instead. And that feels like the coalescence of the experiences of countless indigenous women in Mexico during that period of colonization.

Ultimately, La Llorona is created by patriarchy and is used by the patriarchy to perpetuate itself. She is a justification of colonialism and a condemnation of women who stray from gender roles. She demonstrates that women must be controlled because they’re emotionally volatile, they’re childish, they can’t be trusted with their own bodies. Additionally, it’s all her fault. The father’s accountability is never mentioned. María was expected to be passive about her husband’s infidelity and her reaction to her husband and the murder of her children; those are both violations of her prescribed gender role. So because La Llorona did not maintain her virginal mother status, her situation became irredeemable. By “giving in” to the sexual advances of the Spaniard, her fate is sealed as either an abandoned woman or a monster. The punishment is her fault either way.

So here we see the same individualization that we see in colonial feminism that I mentioned earlier. The individual is interrogated apart from the oppressive system that they inhabit, and the blame is placed on the individual as an irredeemable monster rather than acknowledging the violence that created the monster in the first place. Just like Malinche, the harm that was done to her is ignored. Reinterpretations of the story has La Llorona killing her kids because she had no other option, or that she was driven mad by the abuse that she suffered. Modern reinterpretations are finding value in María’s plight as they seek to interpret the experiences of women who are forced to seek abortions. And other modern feminist interpretations also present La Llorona as a companion in lament about the evils of patriarchal oppression.

AA: Hmm. I’m so grateful for that pushback. That helps flip the script, right? We’ve talked in past episodes about the importance of language, how we frame things, and how saying “gender-based violence” or “violence against women” removes the agent of the violence. We’ve talked about a lot of feminist philosophers pointing out that women in other oppressed groups are not allowed to do things, but then they’re blamed for not being able to do them. And then they’re accused and denigrated for being angry, right? “You’re so emotional, you’re so volatile.” And it’s just always so infuriating to see that happen and then heartening to see people call out those injustices and place the blame where it ought to be placed.

LM: Mm-hmm. I agree.

AA: Will you tell us about the third and final female archetype that we’re going to talk about today?

LM: Yes. The third female archetype we’re looking at is la Virgen de Guadalupe. She’s the archetype of ideal femininity and motherhood. Submissive, reproductive yet non-sexual, docile, and her value is imbued by men. I want to just take a second and acknowledge that we’re crossing over into theological territory here, and that my analysis of the Virgen as an archetype is a critique from the perspective of anti-patriarchy work. We’ll be discussing La Virgen as a symbol and not as a specific theological critique of Catholic doctrine. La Virgen de Guadalupe is perhaps the most loved Catholic icon in the world. The basilica of the Virgen in Mexico City is the most visited Catholic shrine in the world, with 20 million visitors each year. Half of those visitors come on December 11th and 12th, the days that she was reported to have appeared. So there’s something about La Virgen that really resonates with people, and perhaps we’ll get into that a little more as we carry our discussion forward.

The story is that La Virgen de Guadalupe was reported to have appeared during the period of Spanish colonization in 1531. According to the story, she appeared to an indigenous peasant named Juan Diego four times on December 11th and 12th in 1531. She also reportedly appeared to Juan’s uncle, Juan Bernardino, once on the 12th. The initial appearance took place on a hill called Tepeyac in modern Mexico City. Interestingly, this was the site of a temple to an Aztec goddess named Tonantzin, and it had been destroyed by the Spanish conquerors. The Virgen spoke to Juan Diego in his native language of Nahuatl and told him that she wanted a shrine to be built for her on that spot and revealed her name to be La Virgen de Guadalupe. Juan Diego reported the apparitions to the local bishop and was told to get a verifiable sign from the Virgen to prove that he was telling the truth. So Juan told this to the Virgen at their third encounter and he was told to return the next day where she would give him a sign. That evening, Juan’s uncle was taken deathly ill and the next morning Juan missed his appointment with La Virgen because he was going to get a priest to administer last rites to his uncle.

La Virgen intercepted him on his way and asked why he had not returned as instructed. When he explained the situation, La Virgen said, “¿No estoy yo aquí que soy tu madre?” Which means “Am I not here, I, who am your mother?” and gently chided him for not petitioning her for intercession. She told him that his uncle was now well and instructed him to go to the top of the hill Tepeyac for the sign. At the top of the hill, Juan reportedly found Castilian roses, which are not indigenous to Mexico and are not in season in December. The Virgen arranged the roses in Juan’s cloak and he took them to the local bishop. When he opened his cloak to show the roses, they fell to the ground and revealed a miraculous image of which is to this day on display at the basilica in Mexico City.

So that’s the story, and there are some interesting points to consider in this story as we evaluate it from an anti-colonial and anti-patriarchal position. First, the location of the appearance and the instruction to build a new religious shrine. Syncretism was the common method used by missionaries during colonial invasions. Syncretism is when colonizers use pre-existing indigenous religious beliefs or practices and conflate them with new ones to make them easier to swallow. The main mother goddess figure for the Aztec empire had been destroyed and was now being replaced by another mother figure in the same spot. Only now, she’s Spanish and she’s without powers. This religious replacement technique is also often used to validate the action of oppressors, and we see this in the sign and in the name of the new mother figure. The miraculous sign to prove that this apparition was from God was Castilian roses, roses that are from Spain. So a non-indigenous flower that miraculously appeared to testify of the Virgen. Ultimately, it’s saying that if God is going to give a sign to prove divinity, it’s a Spanish sign.

AA: Oof.

LM: And the name that the Virgen revealed has a specific meaning also. Guadalupe is a city in Spain where there was a religious tradition that venerated the Virgin Mother Mary. Many of the conquistadores who invaded Mexico were from Guadalupe, including Cortés. So between the Spanish roses as the divine testimony of the virgin, and the name of the virgin being Guadalupe, and the appearance being to an indigenous person in their native language, I see a pretty direct witness to the divine mandate of Spanish colonization by God.

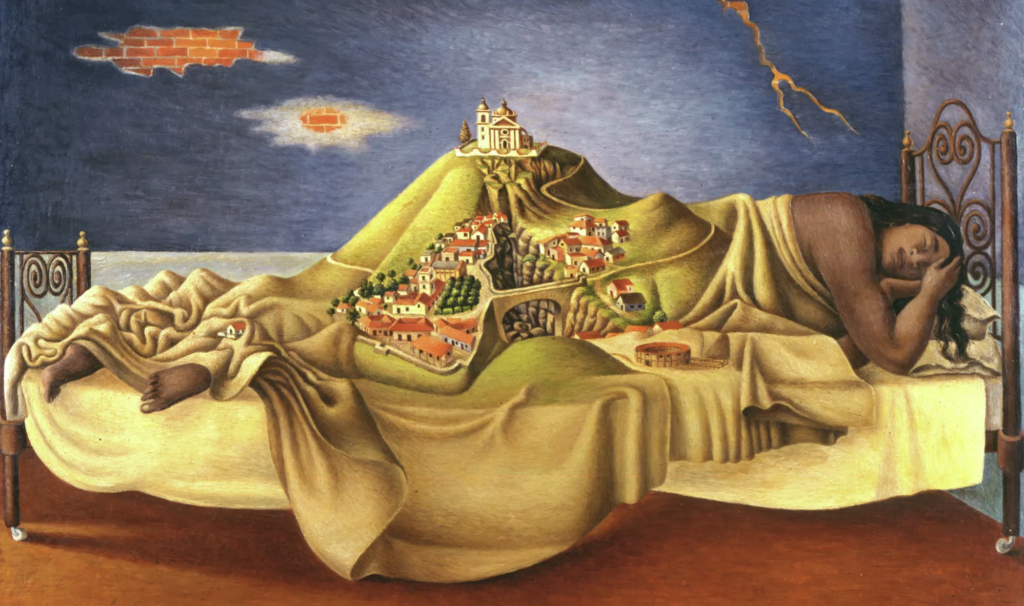

AA: Ugh, I feel gutted. And I also feel like this is in direct conversation with texts from Season One that talked about the figure of the Virgin Mary being a puppet for men to promote whatever agenda they had for women, which was usually to idealize traits that men valued in women like weakness and selfless service. But I had never heard of her being used as a tool for colonialism, and this image kept coming to my mind of Mary statues that are weeping. And I feel like now every time when I see a Virgin Mary statue weeping, especially in Latin America, I’m going to think that that’s why she’s crying. It just makes me so upset. It’s really angering.

LM: Absolutely. I mean, I think you’re reinterpreting the tradition right there in a feminist way, just like modern feminists reinterpret La Llorona as a companion in lament crying about the oppression of patriarchy. So I think that’s totally appropriate. To fully reveal how the apparition of the version was used as justification for the colonization of Spain, we can go straight to the oppressor’s own words. Miguel Sanchez, who wrote the first published account of the apparition in 1684, said: “This new world has been won and conquered by the hand of the Virgin Mary who had prepared, disposed, and contrived her exquisite likeness in this her Mexican land, which was conquered for such a glorious purpose, one that there should appear so Mexican an image.” So basically saying that the invasion and oppression of Mexico was so that Mary could appear, which then validates the invasion and oppression. So it’s this cyclical, oppressive logic that justifies itself.

If we look at the image specifically, we see some really interesting things. Mary is pregnant, she’s covered from head to toe, her eyes are downcast, and her hands are clasped. Interestingly, the image originally had a crown on Mary’s head, but the crown disappeared in the late 1800s. A painter confessed on his deathbed that a clergyman instructed him to remove it, and then the frame was adjusted down to leave no space above her head for the crown. So many didn’t notice that it was gone. Interestingly, an actual crown was later granted by the Pope’s office to La Virgen de Guadalupe, but it’s kept in a lockbox and it’s not displayed. The image emphasizes all the traits that are identified with the ideal woman, like you mentioned. Her pregnancy represents her value as a womb, her title and her doctrinal position emphasized her nonsexual nature, I’m referring to her perpetual virginity. Her downcast eyes and her clasped hands reveal her subservience and obedience. Virginal purity and subservience, those are the two enduring traits through all the variations of La virgen over time that continue, that endure as she’s been co-opted by various groups and agendas.

Interestingly, when we look at the glory that’s bestowed and the value that she has in the tradition, it’s a bestowed glory and value. They’re not inherent or intrinsic to her, but rather given to her by men. Her glory lies in her handmaid status, and that is inextricably tied to her role as a submissive reproductive vessel. So Guadalupe’s value comes from having been sanctified by God because she was used by God as a place of procreation. She would have no inherent value otherwise. Likewise, females in general are starting from a zero value place in this culture, and they must achieve and then maintain that value. Ultimately, maybe the saddest part, is that La Virgen has been described as a Trojan horse for the perpetuation of androcentrism in the Catholic Church.

AA: Wow. Will you say that again? Because that hits hard.

LM: Yeah. La Virgen has been described as a Trojan horse for the perpetuation of androcentrism, or male-centeredness in the Catholic Church. So the irony of using the ideal female figure to perpetuate male dominance. It’s just wicked.

AA: It’s wicked. It’s really savvy marketing. But yeah, it makes sense. And I mean, I hear so often in conversation men will kind of justify patriarchal attitudes and practices by saying that women don’t seem upset by it and women like it this way. And I think that’s partly why it works, especially if you have a female figure as an icon, as a mother figure who seems to accept that status, that we’re supposed to model ourselves after. Then of course a lot of women are going to adopt that and really be so completely immersed in that, in their second class status in society, that they’ll never question it if it’s modeled as an archetype.

LM: Yeah. And that sort of fidelity to this archetype by women actually has a name in Mexico, it’s called marianismo. And this philosophy supports women’s subordinate position in Latin America and the culture’s idealized belief about Latina gender role expectations. To be submissive to the demands of men, to withstand extreme sacrifice, to suffer for the sake of the family, to be virtually pure and nonsexual. This is the other side of the machismo coin. And it fits together the way that we see in American patriarchal evangelicalism, how biblical manhood and biblical womanhood are touted in the same way as being complementary, the male in dominance and the female in submission. Unfortunately, embodiment of these virtues is required for women initially just to obtain that virginal status, and then they have to keep it to remain that way. Non-conformance to this norm leaves only the alternatives of whore or monster. Think about Malinche, La Llorona, those are the two alternatives to La Virgen. And obviously it’s an impossibility to obtain and survive in that virginal archetypal status. So the options are limited, unfortunately, when we rely on those three.

AA: So kind of like I asked with the other two figures, is anyone drawing attention to the way that La virgen has been used to justify oppression?

LM: Yeah, in this scenario where there’s actually a lot of controversy that we don’t really see in the other two, I think it’s because La Virgen is such an endeared image for so many. And as modern feminists reinterpret the image and the meaning of La Virgen, it really causes a lot of outrage among some populations. When she’s used as a symbol of female empowerment, it goes directly against this original programming. So we see that reaction as a system asserts itself. Image reinterpretations include uncovering the Virgen so that she has skin showing, showering her doing daily tasks of women like sewing or running, and also reinterpretations have shown her as a superhero. And these artists receive hate mail and death threats, and there have been bombing threats made against venues that display the art. Critics call the new Virgen depictions a “tart” or a “street woman”, and this is just because she looks like an actual woman, like she looks like a normal human woman. What really seems hypocritical in the outrage and cries against these images is that it’s happening against the backdrop of the endless sexual abuse scandals in the Catholic church, which seemed to have provoked much less outrage. Ultimately, the story of the appearance of La Virgen converted millions of natives to Catholicism, and the religion was used by the oppressors to justify the oppression itself.

To be submissive to the demands of men, to withstand extreme sacrifice, to suffer for the sake of the family, to be virtually pure and nonsexual. This is the other side of the machismo coin.

AA: This is such a tricky one for Catholics all over the world, I think, right? You get a role model, but she’s both a mother and a virgin, which not only glorifies maternity and vilifies sexuality, but is also literally physically impossible to be both. You can’t live up to the standard that you’re presented with. Wow, Levi, well, tell me what some important takeaways are from these three stories for you.

LM: My main takeaway was having my eyes opened to how these types of images of stories are baked into the culture, and we inherit them without consenting to it. It’s just in the water from the moment we’re born. In the case of these three archetypes, they severely damage both men and women as they dehumanize and dominate women, and they brainwash men. And the losses to humanity are just staggering when this happens. All three archetypes are judged within the context of motherhood, which actually first limits the scope of female existence to the role of mother. So Malinche was the traitorous seductress who collaborated with the oppressor and spawned an illegitimate nation. La Llorona is the unintelligent and emotionally volatile mother who makes rash decisions and is forever damned for it. And La Virgen de Guadalupe is the mother of the people, the mother of God, and she’s subservient and submissive, obedient, and pure. So there are three ways you can be a mother: perfectly submissive, non-sexual yet reproductive; sexually seductive, traitorous whore; or emotionally volatile, murderous monster.

I think it’s important to understand that myths and legends are created by us. They’re reflections of our values and our beliefs, and they’re used as explanations first and then legitimation of reality. But they don’t reflect reality at all, actually. They’re self-fulfilling and create self-policing populations as we internalize them. In contrast to the Virgen, both Malinche and La Llorona refused to conform to their prescribed role. Malinche as a sex object servant, La Llorona as a submissive womb, where La Virgen was both. Submissive servant and reproductive. But the reduction of women to the options of whore, monster, or virgin eliminates the complex human nature of women and makes them a symbol instead of a being. We see that females are asked to aspire to La Virgen and avoid at all costs Malinche and La Llorona. And this made me think, “well, what about the men?” There isn’t really a way for men to lose their value other than in a limited way within the patriarchy if we’re not dominant enough, or we are not productive enough, or we’re not aggressive enough. But it’s really impossible for a male to lose his value the way that a female can inside the paradigm of these archetypes.

As a final thought, we can turn to the wisdom of Gloria Anzaldúa, a Chicana writer and activist that I think you’ve discussed before. She wrote, “La gente chicana tiene tres madres.” The Chicana people have three mothers. “All three are mediators. Guadalupe, the Virgin Mother, who has not abandoned us. La Malinche, the raped mother who we have abandoned. And La Llorona, the mother who seeks her lost children and is a combination of the other two. Guadalupe makes us docile and enduring, La Malinche makes us ashamed of our Indian side, and La Llorona makes us long-suffering.”

AA: Oh, that breaks my heart. Can you think of an antidote to that? Maybe I have two questions for you.

LM: For me when I think about these issues, I’m a pretty big-picture thinker, so I often think about patriarchy as a global issue and that all the other -isms are spawned from patriarchy. Racism, colonialism, ecological oppressive practices, everything else is the fruit of patriarchy ultimately, in my view. So it can become overwhelming to think, how do I fix this? I can’t. I just need to burn the whole thing down and start with a new planet and new people. So once I get past the initial overwhelm of that thought, then I think a lot of it just comes down to implicit bias. I need to look at myself and see which of these biases have I inherited, where I have maybe three convenient boxes to categorize women in. Either you are ideal, or you are emotionally volatile, or you’re slutty. Those are the three options. So I can evaluate myself. Do I internally have any of those biases that I use to categorize women? Do I pass any of those on to my children in the way that I’m raising them? And to talk about them. My sisters and I had like a three-hour conversation in preparation for this podcast as I was seeking to understand their experience as half Hispanic, half white women growing up in the culture we did. And so those conversations can be really fruitful just to name things and make ourselves aware of them.

For those people without a specific connection to Hispanic heritage who are listening and interested in participating in the work, I think it’s ultimately the same thing. Do you have any implicit bias? We have to just evaluate ourselves, no matter where we land in the system. What are the implicit biases that I have internalized that I’m perpetuating? And once I’m aware of them, I can start to change them and recognize that you may have parallel archetypes in your culture. You know, maybe it’s not La Virgen or it’s not La Llorona, but there may be one in your culture that is parallel that you can now identify and start to dig up these interesting aspects about, and start to turn them around.

AA: Fantastic. Well, Levi, thank you so much. I learned so much from you today, and one of the terms that I’ll take with me is anti-patriarchist, which you said at the beginning. I love that term. I’ve never heard it, and I’ll be adopting that for sure. Again, I’m so grateful for all the research that you’ve done. I’m amazed that this is just your passion project on the side and that you are a dentist by trade. I’ve never considered driving out of state for my dental care, but I might need you to be my dentist now so you can talk to me while you work on my teeth! I’m just so impressed and so grateful. Thank you so much, Levi.

LM: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me, and thank you for the work you do. It’s really important.

The irony of using the ideal female figure to perpetuate male dominance…

It’s just wicked.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!