“don’t presume to tell us how we should go about our own liberation”

Amy is joined by Dr. Maile Arvin to discuss her book, Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania and the intersections between settler colonialism and patriarchy on the Hawai’ian islands.

Our Guest

Dr. Maile Arvin

Dr. Maile Arvin is an associate professor of History and Gender Studies at the University of Utah. She is a Native Hawaiian feminist scholar who works on issues of race, gender, science and colonialism in Hawai‘i and the broader Pacific. At the University of Utah, she is part of the leadership of the Pacific Islands Studies Initiative, which was awarded a Mellon Foundation grant to support ongoing efforts to develop Pacific Islands Studies curriculum, programming and student recruitment and support.

Arvin’s first book, Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawaiʻi and Oceania, was published with Duke University Press in 2019. In that book, she analyzes the nineteenth and early twentieth century history of social scientists declaring Polynesians “almost white.” The book argues that such scientific studies contributed to a settler colonial logic of possession through whiteness. In this logic, Indigenous Polynesians (the people) and Polynesia (the place) became the natural possessions of white settlers, since they reasoned that Europeans and Polynesians shared an ancient ancestry. The book also examines how Polynesians have long challenged this logic in ways that regenerate Indigenous ways of relating to each other. Her work has also been published in the journals Meridians, American Quarterly, Native American and Indigenous Studies, Critical Ethnic Studies, The Scholar & Feminist, and Feminist Formations, as well as on the nonprofit independent news site Truthout.

From 2015-17, Arvin was an assistant professor at the University of California, Riverside, in Ethnic Studies. She earned her PhD in Ethnic Studies from the University of California, San Diego. Her dissertation won the American Studies Association’s Ralph Henry Gabriel prize. She is also a former University of California President’s Postdoctoral Fellow, Charles Eastman Fellow in Native American Studies at Dartmouth College, and Ford Foundation Pre-doctoral Fellow.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: When I say Hawai’i, what comes to your mind? Beautiful beaches, amazing food, relaxation and escape, perhaps kind-hearted people and a slower pace of life? All of these are true for me, but how much do we know about the history of Hawai’i? I was lucky enough personally to have a Hawaiian roommate my freshman year of college, and we actually roomed together after freshman year because we loved each other so much, she’s one of my dearest friends. And she would teach me Hawaiian history and she would quiz me on each of the islands as we fell asleep at night. She also brought me to Polynesian Club meetings with her, and she would practice traditional dances in our room at night and share those with me. And she even taught me some phrases in the Hawaiian pidgin language that some of her friends used. And so I feel a deeper connection to Hawai’i than I would have if I had not known Kelly. But even with that personal connection to Hawai’i, I never dug deeper into history or asked any difficult questions about colonialism that are right under the surface of the US’ relationship with Hawai’i and that happy vacation feeling that we all have when we think about the islands. So we’re going to ask some of those difficult questions today, specifically about Hawai’i and more broadly about colonization. And to guide us through this discussion is University of Utah professor Dr. Maile Arvin. Welcome, Maile!

Maile Arvin: Mahalo. Thanks so much for having me.

AA: So thrilled that you’ll be here with us. I’ll just read your professional bio and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourself a little bit more personally. Dr. Maile Arvin is an associate professor of history and gender studies at the University of Utah. She is a Native Hawaiian feminist scholar who works on issues of race, gender, science, and colonialism in Hawai’i and the broader Pacific. At the University of Utah she is part of the leadership of the Pacific Island Studies Initiative, which was awarded a Mellon Foundation grant to support ongoing efforts to develop Pacific Island Studies curriculum. Arvin’s first book, Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania was published with Duke University Press in 2019.

So, it’s an impressive bio and actually what I didn’t mention is another article that you wrote that we’re going to be basing our discussion on today, and we’ll talk about that in a minute. But I just have to tell you, Maile, after reading your article I’ve seen it referenced in two or three other articles and books afterwards, and I was like, I know that article and I’m going to meet her! It seems like a really foundational piece of scholarship that you put out into the world, so congratulations on that.

MA: Oh, thanks! Yeah, it’s been great to see so many people find it useful.

AA: It was really useful to me, and I can’t wait to discuss it. But first, could you introduce us to you a little bit more personally? Where you’re from, your family, and a little bit about what brought you to the work that you do now.

MA: Sure. So, I grew up partly in Kentucky and partly in Hawai’i. My dad was from Kentucky and my mom’s from Hawai’i. Specifically, my mom’s from Waimānalo on the island of O’ahu, which is a small Hawaiian homestead town. And so I’m Native Hawaiian through my mom’s side and grew up having a strong sense of Native Hawaiian identity from my mom, even though I grew up a lot in Kentucky. And so I think growing up I always had a lot of questions about how things got to be the way that they were in Hawai’i. And particularly, my mom grew up on what is called a homestead, which has a really long and complicated history. And after doing this for so long, I still am not good at explaining it in a few sentences, but in general, for folks who have no background, Native Hawaiians don’t have any kind of thing that’s like a reservation, the closest thing in the American Indian context. But Hawaiians have what are called homesteads, that were set up in the 1920s, and you have to prove that you have no less than one half part Hawaiian blood in order to be eligible to lease a homestead. Hawaiians can never own the land. It’s owned by the state and leased through the Department of Hawaiian Homeland. Anyway, as you can guess, there’s a lot of history and politics with that.

But what it meant and continues to mean for my family is that the house that my mom grew up in is owned by the state, and it could only be passed on through my family to those with no less than one half part Hawaiian blood. Technically the rest, everyone in my family can get on a waitlist for their own homestead, but the waitlist is notoriously really long. People usually die before, they’ve been on the waitlist their whole life and they still aren’t called up for it. So anyway, all of that is to say that I always grew up knowing, or just having a lot of questions about how that got to be that way and questions about race in Hawai’i more broadly. Because of some of the ideas that your listeners will probably be familiar with, that Hawai’i has a really high rate of mixed-race people and is often seen as kind of a racial paradise or a place where racism doesn’t exist, and ideas like that. I grew up hearing things like that as well as seeing in practice that racism did exist against Native Hawaiian people. So I think all of that brought me to my research and wanting to know more about how to talk about issues of race and also gender in Hawai’i and more broadly.

AA: That was completely new information for me when I read about it. And one thing that struck me as you were talking about Hawai’i as this haven of not much racism, was that maybe people can get that impression and it’s so friendly and warm and open and there’s so much diversity. But then there are these structures, like people can be nice but still maintain really unjust structures, right?

MA: Yeah, exactly.

AA: Although I’m sure there are also cases of overt, unkind, terrible racism as well, I would imagine. Well, thank you for sharing that background. And I would actually love to invite you to share just a really quick history of Hawai’i too, just to set the stage for the specifics that we’re going to talk about. Would you mind giving us a bird’s eye view of the Hawaiian Islands?

MA: Yeah, I teach a whole class about the history of Hawai’i at the University of Utah. I just taught it last semester and I really enjoy teaching that class. And in that class we start by talking about genealogy, actually. Because genealogy is a really important form of knowledge and a way that history gets passed down in Hawaiian culture. And so for Hawaiians as a people, there are many different traditional genealogies, but one of them is called the Kumulipo. And in that story, that genealogy, we’re descended from the god Wākea, the sky father, and Papa, who is known as the earth mother. And from those two, some of their first descendants were Hoʻohokukalani. And then she gave birth to a stillborn who was named Hāloa, Haloanaka. And Haloa was buried in the ground and became the first kalo plant, or taro plant. And kalo, as some people might know, is the basis of our staple food, poi. And so all of that genealogy teaches us that Native Hawaiian people are the younger siblings of kalo, this plant that sustains us. And I say all of this partly just to help orient people towards how Hawaiians understand their relationships to the land in Hawai’i, which is a familial, ancestral relationship.

But kind of zooming out, or incorporating the history as it might be told in more Western ways, Hawaiians are related to other Polynesian peoples and other Pacific Islander peoples. The first Hawaiians we know voyaged from somewhere in the Western Pacific to Hawai’i and settled the islands around 400 CE. And there are these really important traditions of long distance sea voyaging that are important to Hawaiians, as well as all other Pacific Islander peoples. And a lot of those traditions have been subject to revitalization in the last few decades, which is really exciting. As the Hawaiian Islands became more populated and Polynesian people settled there permanently, eventually a society grew up around chiefs having certain powers and responsibilities. And then common people generally worked the land or trained in some specific kind of art or trade. There are estimates that about 800,000 to one million people lived in Hawai’i before Western contact. And a lot of our society was based on fish ponds and the kalo terraces or lo’i kalo that grew taro in large amounts. And that was then made into poi or other kinds of foods that sustained people.

And so each island had a chief and was divided into districts that also had chiefs. And for a lot of Hawaiian history, each island was kind of separate from each other until Kamehameha I went to war with different islands and conquered them, and then united all of the islands. I believe that was in 1810. And so from that time is really when we can talk about Hawai’i as being one nation, although people spoke the same language and generally had shared culture. But it was only united under Kamehameha I, and then Western contact began before the islands were united. James Cook arrived in Hawai’i in 1778, and there’s a lot to be said about Cook, but he actually came to Hawai’i twice. The first time he landed on the island of Kauaʻi and met with some people there and then continued on to Alaska or the northwest territories area and then came back. And when he came back to Hawai’i, he landed on the Big Island, the island that’s also just called Hawai’i. And his conduct there, or the conduct of his men, was such that they got into a battle and he was killed. And there’s been a lot written in Western historiography about if Hawaiians were really savage and that at first they thought that Cook was a Hawaiian god that had come. And then there are a lot of stories about how maybe Hawaiians ate Cook, like in a cannibalistic way. So there’s all this mythology around Cook and his death in Hawai’i. There’s a lot to say about that, but I think that kind of gives you a sense of how for a lot of time, until the last few decades really, when there’s been more Native Hawaiians writing histories in a way that’s legible to Western audiences, that our history has been told in fairly racist and problematic ways.

AA: I’m so, so grateful that you were the one to share the history because I looked up Hawaiian history on lots of different sites and the one that I found, that I thought if I were to share an outline, had like two sentences about Hawai’i prior to European contact. And it’s still presented in the way like “Hawai’i was discovered”, you know what I mean? “This is the date that it became a real place” is kind of what the implication of that is, right? So to ask you to introduce it and have such a rich, and I mean, I know you were condensing it down to the bare minimum of what you could talk about, but I just sat here feeling so grateful that you were able to share such a beautiful, beautiful history.

MA: Thanks so much.

AA: Yeah, really that was so wonderful and so important. Because obviously that’s the original and most important context, like that is the context for that place. I’d love you to talk just briefly about how did Hawai’i become a US state?

MA: So Cook came in the late 1700s, and after Cook many other Europeans started to come to Hawai’i. I think at first it was mostly the whaling ships. And at some point sandalwood began to be traded between Hawai’i and China in particular. So Western folks started to come to Hawai’i for the resources that it offered. And then in 1820 American missionaries first arrived, and then many waves of missionaries from all different denominations followed. The first missionaries were Protestant missionaries from New England. Then the children of those missionaries that came in the early 1800s came of age in Hawai’i, and because of their somewhat elite status they were able to own large pieces of land in Hawai’i. And many of those missionaries’ children became sugar plantation owners in the mid- to late 1800s. And so it was really the power of the sugar plantations that caused the Hawaiian kingdom to be overthrown.

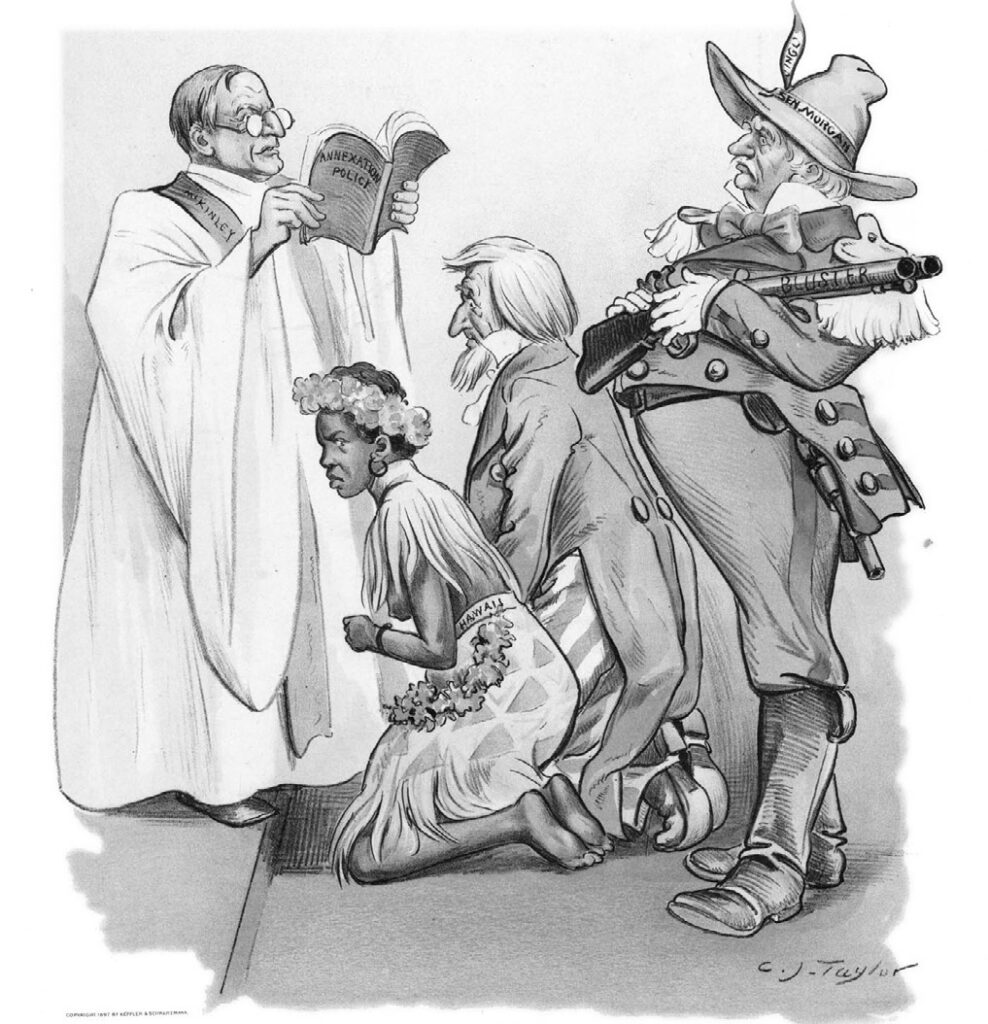

In 1893 a group of white, mostly American, I think one British businessman in Hawai’i at the time, had become increasingly upset that the Hawaiian kingdom wasn’t giving them enough breaks on taxes or whatever they needed to continue to make huge profits off the sugar that they were growing. And so with the implicit backing of the US Navy, who also was beginning to have some presence in Hawai’i, the US military also saw Hawai’i as a really important place to have a stake in because of its so-called strategic position between the US and Asia which is still still the case. So the US Navy was there and they were implicitly backing these American businessmen, and so they, with that threat of force from the US Navy, overthrew the queen at the time, Queen Liliʻuokalani. She wrote a lot about this and said that they forced her hand and she abdicated the throne mostly because she didn’t want to cause bloodshed of her people, who likely would’ve fought to keep Hawai’i independent. And so that’s how Hawai’i first lost its independence.

For a few years between that overthrow and 1900, the US Congress was debating about whether to annex Hawai’i as a territory or not. And at the time the debates were a lot about white Americans who didn’t want more people of color added to the United States. But also at the same time, Native Hawaiians were organizing to say “we don’t want to be part of the United States. We want our kingdom back, the US should restore our kingdom’s sovereignty because some of your citizens overthrew our kingdom.” And so for a couple years, it was kind of unclear what was going to happen. But in 1898, during the Spanish-American War, the US decided it needed to annex Hawai’i as a territory in order for its Navy ships to have a place to stop and refuel on its way to fight in the Philippines. Anyway, that’s how Hawai’i became a territory officially. And after that Act, the Newlands Resolution was passed in 1898 and it took until 1900 for it to be officially incorporated as a territory. And then from 1900 to 1959, Hawai’i was a US territory, which is the status that Puerto Rico has today. Hawai’i became a state after years and decades of debate about its status. World War II and the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 really changed some people’s ideas about Hawai’i in the sense that maybe before that, Hawai’i wasn’t seen as really, really part of the United States. But after Pearl Harbor was bombed and the famous quotes about it being the first foreign attack on US soil, it just hammered home the importance of Hawai’i to the US military. And that along with many other reasons, but that really changed how people living on the continental US saw Hawai’i, and eventually Hawai’i became a state in 1959.

“we don’t want to be part of the United States. We want our kingdom back, the US should restore our kingdom’s sovereignty because some of your citizens overthrew our kingdom.”

AA: My heart is so heavy hearing that history, and I have so many more questions for you that I didn’t plan and didn’t alert you to, and I guess I won’t ask them. But what I will say is I now feel even more motivated to do more digging about the history. And I hope that listeners, if you have had questions come up and some sadness come up hearing about this history, do some research, learn more about it, and we will talk a lot about a lot more issues going on. But again, I’m just so grateful that you shared this history, Maile, because that’s not how we learn about it.

Well for the rest of our discussion, which I’m so excited to get to, because again, I was just underlining and underlining your article, I learned so much from it. The article is called “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy”. And I’m wondering if you can tell us really quickly who your co-authors were and a little about the article, and then I’ll ask you a bunch of questions.

MA: I had the pleasure of writing that article in 2013 with two of my friends and colleagues.

One is Angie Morrill, who was a grad student with me in the same program. She’s Klamath–Modoc, a native tribe in Oregon. And our other colleague, Eve Tuck, who is Alaska Native, and she’s now a professor at the University of Toronto and does a lot of really wonderful work around land education and lots of cool collaborations with Black and Native youth. They’re both so wonderful and it was so great to work on this article with them. Originally, we had been asked to write something together for an introductory women’s studies or gender studies textbook. And we wrote the first draft of this article and we sent it into the textbook and they said, “oh, this is not what we had expected.” I think they really wanted us to write something that was more, I don’t know, like personal testimony about our oppression or something. Which, you know, I think Angie and I when we got that feedback, we weren’t really sure what to do with that. But luckily Eve was farther along than us and could say “yeah, this is wrong and we don’t have to do this.” And we just said, okay no. And then Eve immediately helped us find another place to publish what we had written. So it’s just interesting to think about what gender studies or women’s studies expects or wants sometimes when they’re asking for contributions from Native scholars. So anyway, I think what that helped us clarify in our minds was that it’s not that personal testimony is not important, but we really wanted people in gender studies to grapple more structurally with issues of settler colonialism and the ways that feminism, when it’s only attentive to the needs of white women, it can participate in settler colonialism. And so that’s the history of that article.

AA: I’m so glad I asked that question to get that background. That was fascinating. And so relevant to what we’re talking about, even the process of publishing it. That’s so interesting. Well, let’s talk about some of the themes from the article. The first question I wanted to ask you is pretty basic, but for listeners who haven’t really heard this term before, the article explores two intertwined ideas: that the United States is a settler colonial nation-state, and that settler colonialism has been and continues to be a gendered process. So the first question is, can you define settler colonialism?

MA: Settler colonialism is a specific form of imperialism or colonialism. What it means is that the colonial power comes to a new place and stays, and takes it over and changes existing society so that it’s more what the settlers prefer. And often that involves, or has involved, the various forms of elimination or repression of Native people, of Native societies, and forced efforts of assimilation or just war and genocide. And when we talk about settler colonialism and not just colonialism, it’s not to say that settler colonialism is a worse version of colonialism or a better form, it’s just to specify that it’s the form in which the colonizer comes to stay. And so I think that kind of distinction is important to make. And that distinction began to be made more from the 1980s and 1990s and onwards. Because I think some discussions of colonialism and postcolonialism were always in reference to places like India or other places where the British had taken over, but it wasn’t a site of large-scale British citizens moving to India and imagining that they would be permanently living in India, if that makes sense. And sometimes people in the United States understand that there was a history of white settlers who fought with Native American people. But then often the idea is that it was a long time ago, that colonialism is part of the US past, but that doesn’t happen anymore. Or ideas like that. And so I think when we talk about settler colonialism as a structure, or talk about the US as a settler colonial nation today, what we’re trying to point out is that these processes are ongoing, right? That Native people are still here, but their societies, their cultures, their ways of life are still often under enormous pressures to assimilate or otherwise capitulate to white American ideas about how we should be living.

AA: We’ll have a lot of episodes throughout this season on the settler colonialist state of the United States, and for some listeners, this might be hard to learn about. I know that I’ve cried a lot as I’ve read these things and as it’s described, those are literally my ancestors doing those things. And to talk about that it’s an ongoing issue, the fact that I live where I live, it’s hard not to feel like I don’t have any right to live on this land. I don’t know. It’s really hard once you see it for what it is. My goal in highlighting this and learning all of this, the first step is to know what really happened and then to take action. So we’ll highlight some things that we can do to try to make reparations and try to improve the situation. Because our ancestors aren’t alive anymore, you know, if we have ancestors who did colonize places, they’re not here to make things right. But we are. So anyway, thanks for that, Maile. And then can you introduce some of the other terms? One of them that comes up a lot in the article is heteropatriarchy, so can you talk about that? And heteropaternalism. Those two.

MA: I know you talk a lot about patriarchy on your podcast, so some of your listeners probably understand that patriarchy is a social system in which people have ideas about men being the natural leaders of society, of families. And there are ideas that go along with patriarchy that men are naturally stronger, smarter, better in various ways. And specifically talking about cisgender men. And so patriarchy is basically a society in which the power kind of accumulates to men and not to women, or that there are certain rigidly defined ideas about gender and gender roles that place men above women. And we added in the “hetero-” part to patriarchy to make more clear that the system is dependent on heteronormative ideas, which just means that the assumption is that everyone is heterosexual. That they form nuclear family relationships in which there’s a man and a wife and a family. And so that “hetero-” part of the patriarchy is trying to more consciously recognize that it’s about male domination, but also particularly heterosexual ideas about who men are and cisgender ideas about who men are. The other term that we use is heteropaternalism, which is very much related to heteropatriarchy, but paternalism gets more at the idea that men know best, right? Or that heterosexual men are the ones that define how things go. And it’s very much the same system as patriarchy, but I think paternalism calls attention to how sometimes the ideologies that go along with patriarchy can present it in a way that it’s supposed to be for everyone’s best interests.

AA: Yep, totally. That makes sense. One quote that I wanted to ask you about from the article says that “there are rampant misrepresentations of indigenous peoples in their lives, in school curricula, the media, and the sociological imagination.” So I wanted to ask you, what are some of those misrepresentations and what are the impacts of those misrepresentations on indigenous peoples? How does it feel personally and how does it affect systems in society?

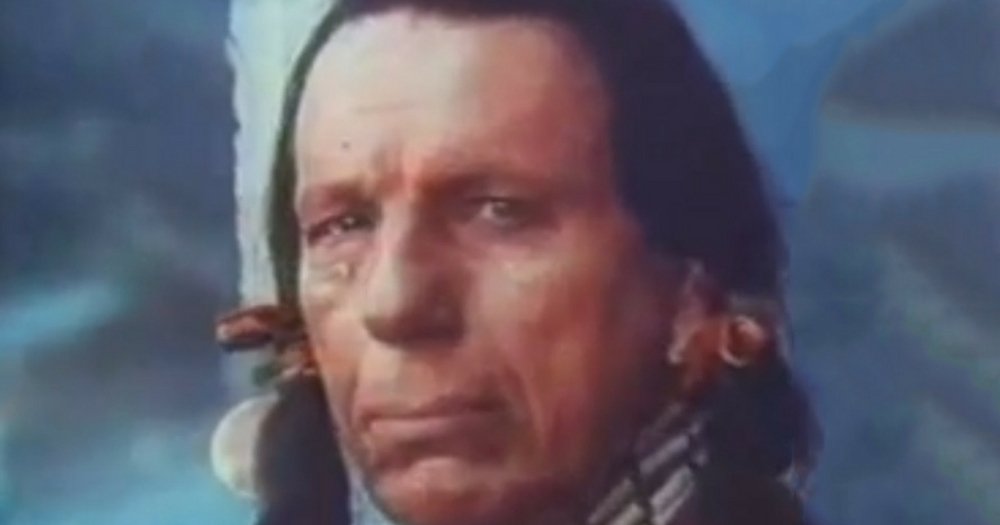

MA: Yeah, thanks for that question. I mean, I think many people are familiar with those misrepresentations. I think I mentioned before that often in the US, mainstream media presents Native people as mostly existing in the past. That they aren’t really full members of contemporary society. Or if they are, that somehow they’re not authentic or something. So one example that I use a lot in my teaching when I’m teaching about these kinds of issues is that in the 1970s there was this public service commercial on TV where it was trying to raise awareness about littering and taking care of the environment. And in the commercial, there’s a Native, or an actor who’s made to represent a Native American person, and he’s canoeing around a river and crying at the site of all the trash in the river. And so on the one hand, that representation has a good intent in the sense that it’s trying to raise awareness about environmental issues and that people shouldn’t litter. But it’s using this really stereotypical idea of a Native person as existing outside of time. And as a native person, this could only ever be tragic, and that they’re passive, right? That they’re not able to do anything about saving the environment. The only thing that they can do is cry or pick up some trash.

There are representations that are maybe more explicitly racist, like some of the sports mascots who are Native people or caricatures of Native people. And there’s been a lot of folks who write about those and try to get Native mascots changed. But I think that maybe sometimes the more insidious and common misrepresentations are ones that kind of see Native people as noble savages. Like noble in the sense that they’re more connected to the Earth or that they represent a better society that existed before, but is unattainable now. And that’s just so problematic in many ways. But you know, it really ignores the ways that Native people today are still alive and are very active in resisting environmental injustices around the world.

AA: The next quote I want to read, if anybody’s seen Season 1 of The White Lotus, this might remind you of a character in it, but we’re not going to talk about that. But this was so interesting because there was this dynamic in the show that really puzzled me and I was just chewing on it for days and days after the season ended. And then when I read this, I was like, that’s what happened, that’s what it was. Here’s the quote: “Whiteness is made to seem neutral and inviting or inclusive of racial, sexual, and other minorities by being included, whether by choice, coercion, or force, in whiteness. A wide array of indigenous peoples, people of color, and queer communities are given the ‘opportunity’ to take part in the settling process that dispossesses just such othered peoples globally.” This is one of the key points of the essay, at least as I thought of it, and it’s one of the key points I’m hoping to highlight on this season of the whole podcast. So can you expound on this idea, Maile?

MA: Yeah, I think this can be kind of a hard concept to get. And the discourse today about how to be anti-racist or how to promote diversity, the idea is often to just be more inclusive of others, right? But I think what we’re trying to say in the article is that often those attempts at being more inclusive are just like inviting more people of color into situations that are still fundamentally structured by white ideas and white assumptions about how things should be.

So when that happens, then it’s all on the people of color or whoever is “othered” being brought into the white space to fix it, and that’s a really unfair expectation to put on people. And so in the article we’re talking about how that happens with feminism, right? And when white feminists try to engage with feminists of color, indigenous feminists, sometimes it’s the same kind of disconnect or struggle. Because white feminists are wanting to invite indigenous feminists into white feminism. But indigenous feminists or Native feminists or Black feminists are saying no, there are some assumptions that you have as feminists that assume that the problems are only about things that impact white women. But we’re saying that these larger structures of settler colonialism and white supremacy set up our society in such a way that we can’t just talk about how things impact white women. But these larger issues that encompass heteropatriarchy are really implicated in white supremacy and settler colonialism. And therefore we have to push white feminists who think of things in a narrow way to expand the scope of what they think has to be changed in society in order to be a more just society.

AA: Yeah, Maile, that’s actually the perfect bridge to talk about one of the big themes in the article that I learned so much from, where you write about five challenges that Native feminism brings to “whitestream”. Like white, mainstream feminism. So what if I just read the title sentence of each of the five points and then could you explain each one to us?

MA: Sure.

AA: Okay. So the first challenge of these five is it says “problematize settler colonialism and its intersections.”

those attempts at being more inclusive are just like inviting more people of color into situations that are still fundamentally structured by white ideas and white assumptions

MA: It’s really to try to understand the ways that settler colonialism is a gendered process. And I think one example that I talk about in that section of the article is the issue of blood quantum. I mentioned the Hawaiian Homestead Acts earlier and how Hawaiians have to prove that they have so-called 50% Hawaiian blood to qualify. And the impact of that policy on Native Hawaiian people has been that Native Hawaiian women face certain kinds of pressure to marry Native Hawaiian men with high blood quantum so that they can have children who have a high enough blood quantum to meet this requirement. To allow their kids to qualify for Hawaiian homesteads.

AA: That’s crazy.

MA: Yeah. And this blood quantum idea is tied to very heteronormative ideas of a family, and the ways that race gets passed down, and Western understandings. And that places a lot of pressure on women, right? So that’s just one example of the ways that settler colonialism is gendered. And the idea with that challenge is to try to get other people who might be interested in feminism to see how that works, I guess.

AA: Can I throw in one thing too, I was thinking about it when you talked about the homesteads at the very beginning just to drive that home for listeners if this is new to you. I looked it up more, I was like, what is this system? I’d never heard of it before. And a lot of the articles that I read framed this like, “oh, this is so cool. Native Hawaiians can get free land, they’re so lucky.” And it’s so important that you point out that they can never own that land. Basically you borrow it, and I was like, “wait, from whom?” From the colonizer! They take the land and say, “oh, if you’re lucky and you have this much blood and blah blah blah, we get to decide what all the rules are and then if you’re lucky and your name comes up on the waitlist, then you can borrow back land that we stole.” It just makes me so furious, I can’t even process it. It’s like they’re so benevolent for letting you borrow the land they stole from your ancestors.

MA: Right, yeah. It’s such a mess.

AA: A mess! Okay, there’s another quote in this section that I really wanted to bring up. Would you mind reading it for us, Maile?

MA: Sure. We wrote: “Native Hawaiian women, like other indigenous women, do not need to be saved from the ways heteropatriarchy and heteropaternalism have taken root within indigenous communities. They are already and have long been working toward decolonization within and beyond their own community’s boundaries. Many indigenous women activists have refused the false binary between fighting for ‘women’s issues’ and fighting for so-called Native issues, which for indigenous women are always coiled together”.

I think that’s another thing that Native women often face with white feminists who haven’t thought critically about these things, is that white feminists are saying, “oh, it’s the Native men in your community who are oppressing you.” And what Native feminists are saying is that that’s not quite right because our traditional Native culture was not patriarchal. And so it’s true that many Native men have internalized these patriarchal ideas, but that came from colonialism, not from our own culture. And therefore we don’t need to be saved from our own culture if we need you to work with us to dismantle colonialism.

AA: Thank you. As an aside, that’s what I wrote my master’s thesis on, but in the Black context of the civil rights movement.

MA: Awesome.

AA: Yes, things for white feminists to learn from, from doing that. Okay, the second challenge was summed up by the sentence “refuse erasure, but do more than include”. And you talked about this just a minute ago, but is there something else that you could add to that?

MA: Like I was saying earlier, inclusion is not enough.

AA: The third challenge to whitestream feminism that Native feminism supplies is it says “craft alliances that directly address differences”.

MA: Yeah, we wrote, “One component of this challenge will be for allies who are settlers to become more familiar and more proactive in their critiques of settler colonialism, and to not rely on indigenous people to teach them how to become effective allies.”

AA: I’ll throw in there that many, many books have been written on this topic, so if you want recommendations, contact us or look back to past episodes on the podcast. And I just have to say how grateful I am for scholars who do this work. They go through years of research, and it’s a personal process too, and put the information out there. So instead of bothering people who have lives and are busy to explain it for their thousandth time, we can just read a book so we can educate ourselves. That’s my plug there.

MA: Yeah. And I think it goes along with what we’ve been saying, but I think sometimes people want to integrate indigenous issues or indigenous people into their projects or events but in ways that are always on their terms of the group that’s not indigenous. And so the idea with this challenge is to directly address that indigenous peoples and other groups might have different goals or different needs at the time. And if people want to have partnerships with Native communities, those that Native communities’ needs and wants should be part of the structures, whatever project you’re doing, not just added in when it’s convenient.

AA: This section also brought out some of the appropriation that happens. And I wanted to ask you about that. I was particularly struck by what you wrote about the version of Thanksgiving, where it’s from the point of view of the colonizers. And then you also talk about the Boston Tea Party and how Native Americans are depicted there. Could you talk about that and talk about appropriation a little bit using those stories in particular ways?

MA: Sure. So I think Thanksgiving is this foundational American myth about our country’s origins as being one where Native people and the white settlers were friends, right? That they had this nice feel together. And I think a lot has been written on the actual historical accuracy of the first Thanksgiving, but which I won’t get into, but even as I like pumpkin pie and having dinner with my family on Thanksgiving, I think we have to be really critical of that vision of Thanksgiving and this vision of us as being founded and Native Americans and white settlers being friends. What does that do in terms of erasing the actual violent history of colonialism in our country? And so I think what we’re trying to get at in the article is that so much of the mythology of America has been built up around the idea that the Native people and white people are friends, or that there’s some kind of benevolent relationship there.

And in certain individual cases that’s true, but the point is that structurally that’s such a lie. And that it covers up the violence of the conquest of this land.

And I think from there we were trying to get people to think about other forms of appropriation, like when people dress up as Natives for Halloween or something. What is that about? It seems like it’s partly enabled by the sense that some white people think that Native people and white people are historically friends or that there’s some kind of historic connection there or relationship there that allows them to play Indian sometimes. And I think what we’re trying to say is that that’s not true, right? That Native people are not costumes. And the fact that we even have to say that is kind of evidence of the ways that colonialism is so naturalized in our country.

AA: I have to say too, I mean, I was blind to that my whole life until recently, honestly. And I’m so grateful when that was pointed out to me and I sat with it for a while and thought, how would I feel if I knew that my people, my ancestors, that there had been a genocide against my people and then the people who had committed that genocide… If I saw them dressed up in the traditional costume of I don’t know, my grandparents, like if they were dressing up like the people that they had tried to exterminate and I was there looking at it, I don’t know. For any listeners who haven’t walked yourselves through that mental exercise, that was really useful for me to imagine how that would feel. I don’t know how that feels to you, Maile, for me to say that, but that is what my thought process was and it became so repugnant to me. I couldn’t even believe that anybody couldn’t see that. But I had not been able to see it before, honestly. Just because of the air that I breathed my whole life. I just had that position of privilege of never having had to look at it like that before.

MA: Right, it makes sense. It’s not that you are a bad person or that necessarily people are just meaning to be cruel. But it just shows how deeply structural these things are, right? And that we’re not taught that that’s wrong, we’re taught that that’s something that’s acceptable. I know that when I was in first grade, I think we had some kind of Thanksgiving play where some people dressed up as the pilgrims and some people dressed up as Native people. And very stereotypical, wrong ideas of what that looked like too. So, it’s just so pervasive that it does take a lot to overcome it.

AA: Yeah, I mean as a first grader, if the adults hand it to you and say “we’re making this construction paper craft here, wear this now, say this, now say this,” and we’re being indoctrinated into this thing that we didn’t choose and we don’t even know how to question. Can I ask you two quick questions? So one thing that came to mind that wasn’t in the article, but as we’re talking about appropriation, suddenly I was like, what about luau parties? What about white people wearing grass skirts? Suddenly I was like, oh, I feel uncomfortable with that. I don’t think that’s a good idea now that I’m thinking about it.

MA: Yeah, because it might not be as obvious, but it is a way that people kind of play Native Hawaiian, right?

AA: Yes, exactly.

MA: In ways that are really stereotypical and wrongheaded, and it ignores the ways that Hawaiian culture– In some ways, since missionaries arrived in Hawai’i, but especially after the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown, Hawaiian hula was really repressed and at some points it wasn’t able to be performed in public because it was understood to be rude and savage and too sexual in some missionaries’ eyes. And then after the overthrow, the white people that took over Hawai’i banned Hawaiian language from being the language of instruction in schools. And so that quickly eradicated the number of people who spoke Hawaiian or could be fluent in the Hawaiian language. And that didn’t change, I mean it’s still the subject of a lot of revitalization efforts today to get children to be able to learn Hawaiian again in schools. So I just think, again, it’s not that people who have luau themed parties are trying to be cruel, but just those forms of appropriation really do erase the actual history. Not only Hawaiian people, but particularly Hawaiian culture was repressed for many years. But then it’s okay for white people to play at it in a silly way. Yeah, it’s not great.

AA: Yeah, thank you. Okay, number four. The fourth challenge is to “recognize indigenous ways of knowing”.

MA: I think this one is related to what I was saying before, about how originally the people that we wrote the article for wanted us to just give personal testimonies about our experiences. But we wanted to get people to understand that indigenous studies is a field with its own theories and really extensive scholarship about certain ideas that people can learn from, not just Native people. So under this section we summarize some of the biggest concepts or theories in indigenous studies and try to show how these theories are relevant and could be really interesting to other feminist scholars. We talked about indigenous ideas about land being a form of knowledge in itself, not just property that should be owned. And also how land, I think I mentioned before how for Hawaiians, land is our ancestor, right? And that we’re really intimately tied to particular pieces of land in Hawai’i and have certain responsibilities that are understood really as familial obligations. And so I think it’s not that we’re seeing that white people or other non-Native people should therefore start to think about land as their ancestor, because that would be a weird appropriative thing, right? But there are different ways to think about land. We don’t have to think of land only as property to be sold.

it’s not that people who have luau themed parties are trying to be cruel, but just those forms of appropriation really do erase the actual history

AA: I have a question about land, actually, that I wanted to ask you because a few years ago, my oldest daughter brought to our attention – and we aren’t a family that goes to Hawai’i a lot, I think we’ve just gone once with our kids before we thought of this. But she said that there’s an issue that Native Hawaiians have been priced out of their own homeland by non-Hawaiians, and that the islands have become so overrun by tourists and by people who come and buy second homes that there are people saying, first of all, please don’t purchase land in Hawai’i. And also maybe don’t even come as tourists. But then I know that the economy is also kind of dependent on the tourism industry. So what is your take on those issues? So that we can be responsible if it’s appropriate to go to Hawai’i as a tourist, and if it is appropriate, how would we do that responsibly?

MA: Yeah, I think there’s so much that could be said on this point. In the nineties, one of the really important Native Hawaiian scholars, her name was Haunani-Kay Trask, she wrote this piece and she was trying to inform people about the history of Hawai’i and some of the ill effects of tourism on Hawai’i. And at the end she wrote very clearly and provocatively, that if you want to help my people, don’t come to Hawai’i. And so I think today some people still really believe that and some people understand that it can be a little more complicated in practice, but there’s a book called Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i that talks about some of those issues in the Hawaiian context. It’s edited by my former colleague, Hokulani K. Aikau, and another colleague, Vernadette Gonzalez. And I think that book has a lot of really great ideas about how people could start to answer those questions for themselves. But yeah, it’s true that land in Hawai’i is so incredibly expensive that I think there are more Native Hawaiians that live outside of Hawai’i than in Hawai’i because of the cost of living there.

AA: I will get that book. And again, it’s called Detours. We’ll put it on the website and we’ll highlight it on our social media so that listeners can pick it up and do more research. Okay, we’re to the final challenge. The fifth challenge is to “question academic participation in indigenous dispossession”.

MA: I think with this challenge we’re trying to get people to think more concretely about what they might do in terms of, for example, if we’re talking to other professors who are putting together syllabi on US History, we were asking them to think, what are the readings that you have on your syllabus that address Native people? Are there any, and if there are, what are those readings teaching your students about Native people? Is it teaching them that Native people were here before white people came but now they’re not really that much part of contemporary society? Then we are challenging them to update your syllabus. For a gender studies or women’s studies class, often Native Americans might be included in one reading on Sacagawea or one reading on Pocahontas. But again, if that’s the only thing you’re including in your syllabus, then what we’re saying is that that’s really a tokenized kind of inclusion that might actually do more harm than good. Because it teaches that there are just these individual exceptional Native women, and the ways that those women are talked about in mainstream media is really disconnected from their larger society and the historical context in which they lived. And so I think we had some suggestions about other ways to approach things like teaching about Pocahontas. There’s a really important article by a Native scholar, Rayna Green, who talks about the so-called Pocahontas Perplex, where she argues that Native women often get represented as either this heroic, saintly Indian princess, like Pocahontas or I think what she refers to as the “squaw”, which is like the dark-skinned, more “primitive” representation of Native women. And she’s pointing out that the Pocahontas image is kind of the noble savage image. And the other image is the ignoble savage image. And they’re part of the same problematic and colonial mindset. And it’s not just about not including the images of the ignoble savage, but also the questioning and being more critical of images of the noble savage as well.

AA: So to wrap up this section on the challenges to white feminists, would you be willing to read this quote that you included in your article by Janet McCloud? I thought it was really powerful.

MA: Sure. She writes, “So let me toss out a different kind of progression to all of you feminists out there. You join us in liberating our land and lives, lose the privilege you acquire at our expense by occupying our land. Make that your first priority for as long as it takes to make that happen. But if you’re not willing to do that, then don’t presume to tell us how we should go about our own liberation, what priorities and values we should have. Since you’re standing on our land, we’ve got to view you as another oppressor trying to hang on to what’s ours.”

AA: Oof. Yeah. That’s powerful. Well, thank you, Maile. Again, I learned so much from you, from your written work and then from our conversation today. Are there any last thoughts that you’d like to share as we wrap up? And if not, I don’t have to ask you that question. It’s up to, totally up to you!

MA: Well, thank you so much, Amy, for all of your really thoughtful engagement of my work and for having me on the podcast. And I think maybe for you and your listeners who might be really troubled by confronting some of these issues, I think sometimes when people first learn about how Native Americans still face a lot of oppression and that the land that we live on is still Native land that was unjustly taken from Native people, the idea is, “then where are we supposed to go? There’s nowhere else for us to go.” And I think the thing is that I don’t think any Native people are saying that everyone has to go. And actually that’s more indicative of a Western society’s ideas about land, right? That would be the assumption that everyone has to go. It’s not necessarily about that, but it is about learning more about Native struggles wherever you live and trying to learn how to support those efforts in a good way.

AA: Well, thank you for that. And again, listeners, we will provide book titles, article titles, including Dr. Arvin’s work, but also including others. And just start googling, just start looking stuff up and do some deeper digging so that we can all keep growing and learning and live intentionally and with integrity and with compassion. So again, thank you so much, Dr. Maile Arvin for being with us today. I really enjoyed it.

MA: Sure, my pleasure. Thank you.

Native people today are still alive

and are very active in resisting injustices

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!