“It is an amazing time to be sharing books with kids”

Amy is joined by school librarian, Casey O’Leary, to confront the alarming increase of book bans and challenges in recent years, exploring where these challenges are coming from, why parents are concerned, and how librarians and authors are pushing back again censorship.

Our Guest

Casey O’Leary

Casey O’Leary is a K-12 school media specialist in Indianapolis, Indiana. She has a bachelor of science in elementary education and a master of library science, both from Indiana University. O’Leary served as a public children’s librarian and manager for 10 years prior to moving into school librarianship. She is active in the American Library Association and recently served on the Children’s Literature Legacy Award Committee and is also a reviewer for School Library Journal.

The Discussion

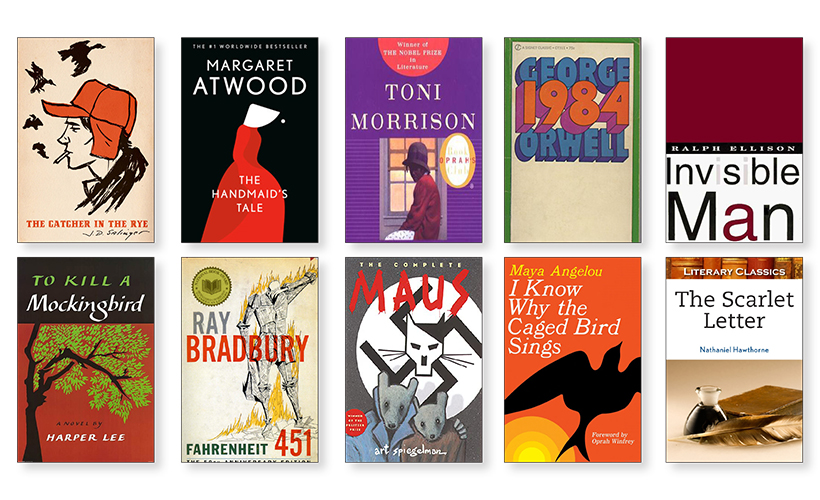

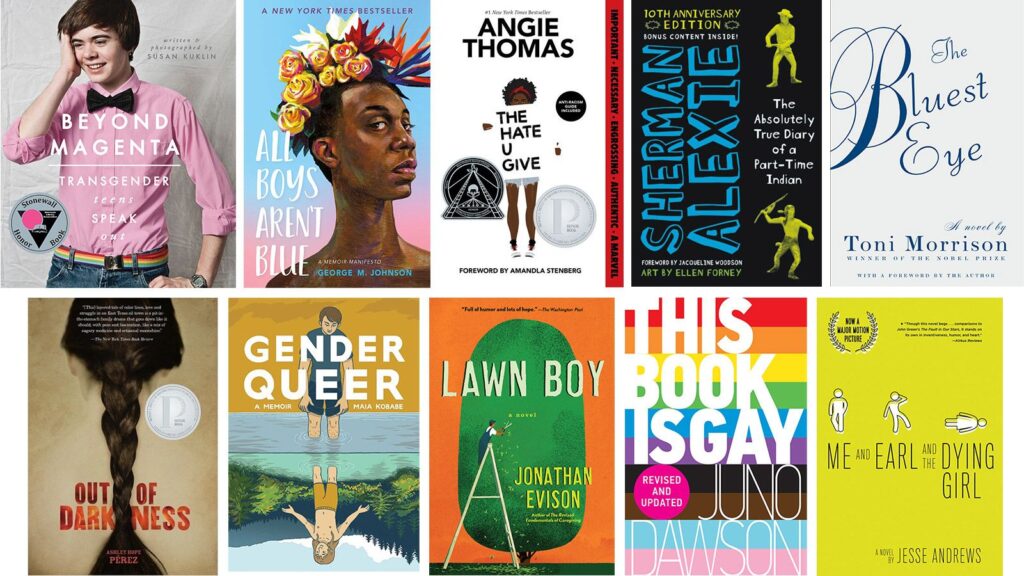

Amy Allebest: One common feature of repressive systems is the suppression of education. And it makes sense. If the masses start learning about the structures that are keeping them down, if they start having empathy and solidarity with other people who are experiencing similar injustices, then they may start demanding better treatment. So, repressive systems are famous for restricting information and specifically for banning books. Here are some book titles in the U.S. that have been banned in the last couple of decades: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros, Maus by Art Spiegelman, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Patterson, Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret by Judy Blume, Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, The Glass Castle by Jeanette Walls, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon, The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien, The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman, Beloved by Toni Morrison, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, The Color Purple by Alice Walker, and The Giver by Lois Lowry. This is really just the tip of the iceberg! There are so many books that have been banned over the course of the last few decades in the United States, and the book titles that I just read are ones that I consider an absolutely essential reading list. I am really excited to talk about this issue today, the politics of book censorship, with teacher and librarian Casey O’Leary. Welcome, Casey!

Casey O’Leary: Thank you so much! Thank you for having me. I’m a big fan of the podcast, so this is very exciting for me.

AA: It’s very exciting for me, too. This is such an important topic and I’m so glad that this topic got brought to my attention. I’m really, really eager to hear your thoughts and your personal experience. First, I’ll read your professional bio, and then you can tell us a little bit more about you. Casey O’Leary is a K-12 school media specialist in Indianapolis, Indiana. She has a Bachelor of Science in Elementary Education and a Master of Library Science, both from Indiana University. Casey served as a public children’s librarian and manager for ten years prior to moving into school librarianship. She is active in the American Library Association and recently served on the Children’s Literature Legacy Award committee. Casey is also a reviewer for School Library Journal. What a great and really important job. I’d love it if you could tell us a little bit more about how you got into this career, but first start out by telling us a little bit about where you’re from and the different factors that have made you who you are today.

CO: Sure. I was actually born in Connecticut and went to elementary school there. And when I was 12, my dad decided that he would prefer the warmer weather and packed us all up and we moved to Thousand Oaks, California, which is just north of Los Angeles. And it was a huge culture shock for me. We lived in California for about a year and then moved to Michigan, that’s where I went to middle school and high school. I wanted to go anywhere but a university in Michigan, because everyone I graduated with was going to one of the many wonderful colleges and universities in Michigan and I wanted to be different. So I applied to Indiana University to study music, got there, realized that I was passionate about music but maybe not at the level that you need to be to succeed. It’s one of the top music schools in the country, so I switched my major to elementary education. I loved my elementary school experience. I can name off all of my elementary school teachers by name, still. It had a profound effect on me as a person, as a learner, and as a reader. I had a wonderful school library in Connecticut when I was growing up.

So, I graduated from Indiana University with a degree in elementary education. I got married and raised two children when they were little. And when they were back in school I went back to work, and I worked as a teaching assistant for a while, a Title I reading assistant, and eventually got my own classroom. It was a first-grade classroom and I was not good at it. Classroom teaching is one of the hardest jobs there is. I believe it’s the most important job in the school building right up there with the school secretary and the school custodial staff. The classroom teacher is responsible not just for their students, but for the expectations of the parents, of the administrators, of the district, of the state, there are federal expectations, and it’s a real balancing act. It’s a really incredibly difficult job, so I have huge respect for classroom teaching but I knew that it was not a good fit for me.

And when I was trying to decide what to do next I thought about what was my favorite part of the day, and it was right after lunch, reading aloud to my students. I enjoyed it, they enjoyed it. I felt really confident and I thought, “I wonder if I can do something with that. Maybe I could be a school librarian.” And I found out that if you took one extra class, you got the Master in Library Science, so that’s what I did. I left teaching, I went back full-time and started in public libraries rather than school. Even being in library school, I felt like I had found my people. Everybody else was quiet, everybody else was well-read, and it was a really joyous learning experience for me.

AA: Oh, that’s so great. I love it. Thanks for all of that. Let’s dive into the topics that we want to discuss today. I started the episode by listing all of these books that have been banned. And that’s been in the news a lot. I feel like lately there are a lot of book bans going on, especially in certain parts of the country. Could you walk us through what’s happening in various states across the U.S. right now?

CO: Sure. I want to start by saying that I was actually listening to a podcast called Those Who Can’t Teach Anymore, and it’s by a teacher, his wife is also a teacher, and he’s talking about the challenges of being a teacher right now in the world of education. And one of the podcast episodes talks about censorship of books and materials as far back as, for example, the American Indian education programs where American Indian children were taken away from their families and put in Christian boarding schools, and the prevailing statement was “Kill the Indian, save the man.” That’s the quote that’s most often attributed to it. And this podcast host is talking about how deculturalization was the method of educating children at that time. That if they collectively removed all of the different cultural beliefs and practices and everyone learned the same thing, you would end up with a higher quality of life and with a population that could be controlled.

So to me, this isn’t anything new. It’s a cyclical process and it’s almost always about political power and control. I think it’s resurging now for some very obvious reasons, certainly what’s going on in the United States politically, and a desire to focus away from being a global society and into a deculturalized central society where we only speak one language and we only believe certain things. And that education is this constant battle between that deculturalized idea of society and the idea that the more we expose ourselves to different cultures and ideas, the more defined of a human we become and the better able we are to be empathetic and compassionate members of a global society. Right now, it’s sort of historically cyclical. I would say that right now it’s gained a lot of attention, mostly because of it being covered in the media, and also because the efforts are so blatant by specific groups who are formed specifically for this purpose.

I also want to point out the difference between a book challenge and a book ban. A book challenge means that there has been a request to have a specific title or a series of titles removed from a school or library, basically a request to deny access to certain materials. In most places, my school is one of them, most public libraries and school libraries will have specific policies in place. They’ll have a form that has to be filled out that does ask if the person filling out the request has read the book, and the specific reasons for removal. Then that request is reviewed by a committee, usually of people within the library or school and then community members, and a decision is made whether or not to remove the title completely, to move it to another part of the library, maybe from the children’s department to the adult department or teen department to the adult department. And there have been a lot of challenges recently. The actual process of getting items banned, meaning that they have been removed and there is no longer access to them, is less common, I think, than the challenges. But it kind of gets looped under this umbrella of book banning. So the challenge is sort of the beginning of the process and the ban is the ultimate result.

AA: Okay, that’s really helpful. Thanks for walking us through that process. One question I have is, does a typical school or public library get challenges often? And I imagine it’s mostly coming from parents, is that right?

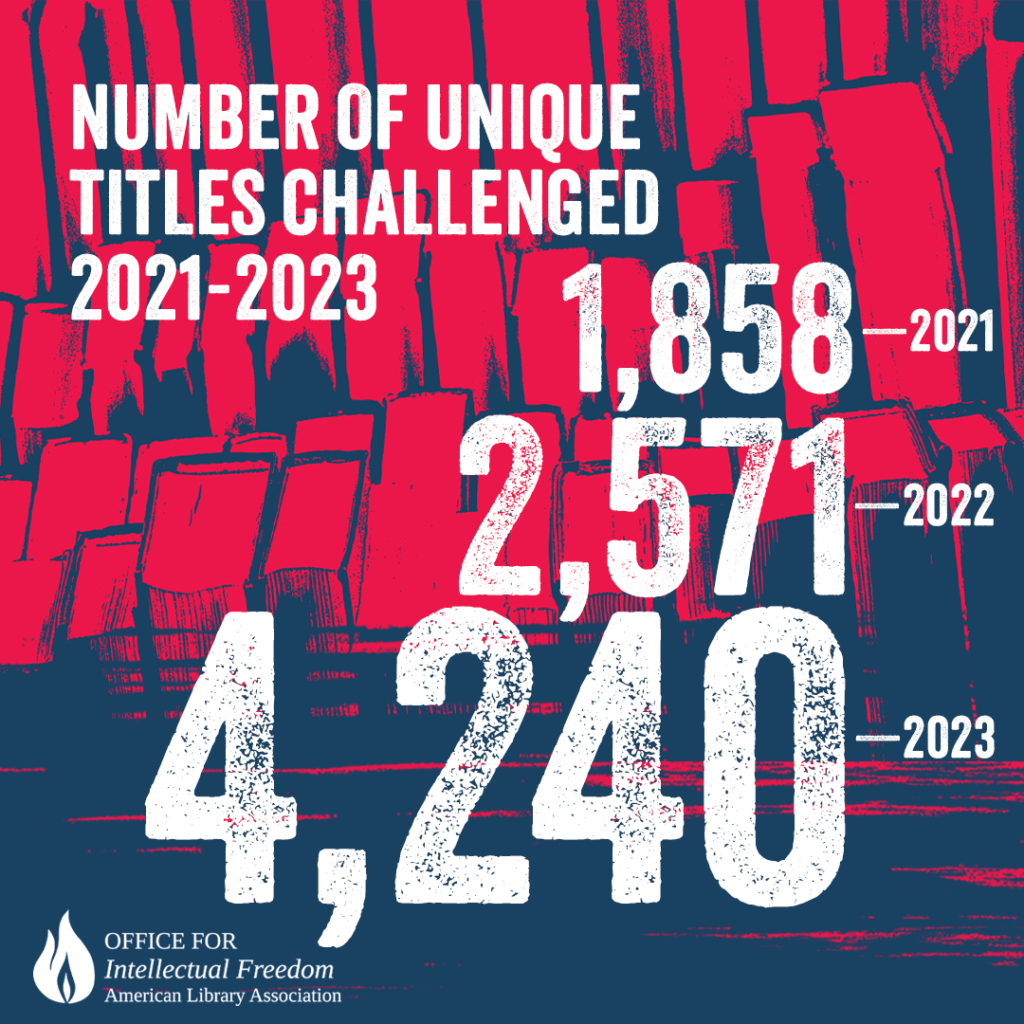

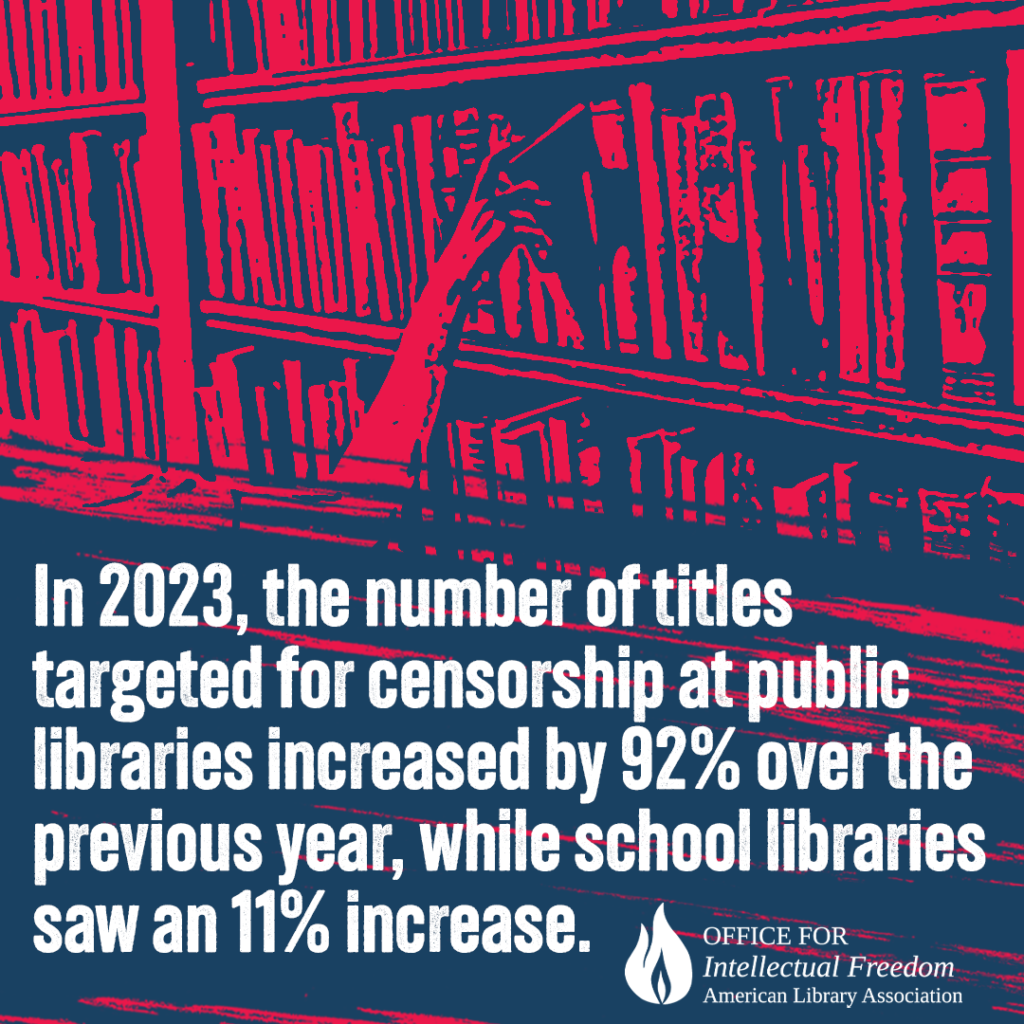

CO: Yes. It depends on the community perception of the library within it. In my experience, many public library directors are extremely familiar with the needs of their community. I have worked in public libraries in what I would say are very politically conservative areas and I have worked for public library directors who are very much a part of their community. They live in that community and they have good relationships with people in that community. But both directors and staff tend to walk a very fine line, where they want to make books and materials available without angering people in their community who might object. I would say that it happens more often than we hear about. The American Library Association Office of Intellectual Freedom actually releases a report every year on the number of individual or unique titles that have been challenged and the top 10 list of titles that have been challenged or banned. In 2023, which is the most recent report, there were 4,240 unique titles that had been challenged. That’s up almost 2,000 titles from 2022.

AA: And that was going to be my question. Is that normal?

CO: No.

AA: Wow.

CO: I have personally been hearing from more public librarian colleagues that not only have there been more challenges by community groups, there have been more efforts to dox public librarians, to shame them on social media, to troll their internet social media accounts. Some public librarians and school librarians have been threatened. Several of them have tried or are trying to legally fight back against groups that are attacking them personally, and it’s just a very difficult fight within the laws that we currently have in our states and in the United States. So I think it’s more common because the Office of Intellectual Freedom can only report on what’s reported to them. From my personal experience, it’s not too many people but I think in certain pockets of the country it’s a real problem. And one of the issues is that groups are emboldened to challenge hundreds if not thousands of books at one time.

If you think about the processes for each individual title, a person has to fill out a form and submit it. If I am making a political statement and I try to ban 700 books, those librarians then have to find the time to discuss and research each individual title. That takes an enormous amount of time. And some policies require it be done within five days of the request, sometimes it’s 60 days, it just depends. I think the prevailing assumption is that if these groups like Purple for Parents or Moms for Liberty, if they flood librarians with requests, we’ll take the books off the shelf because we won’t want to deal with the issue or we won’t have time or won’t be able to meet the needs. I think it’s happening more than it is being reported.

In 2023, which is the most recent report, there were 4,240 unique titles that had been challenged. That’s up almost 2,000 titles from 2022.

AA: That’s crazy. Okay, two questions. You just mentioned two organizations. Who are these groups and other groups that are doing so many challenges? And what are the titles that are being challenged? If you could kind of categorize certain types of books. I mean, I have guesses, but I’d love to hear from you who’s being challenged and who’s doing the challenging.

CO: Yes, so Purple for Parents and Moms for Liberty are both groups that I think are national organizations and have groups in the state of Indiana, that I’m aware of. I will acknowledge that I think about them as little as I can because I get so angry and frustrated and I end up feeling kind of helpless when I look too much into the behavior of groups like this and the misinformation that is being spread. So to protect my own mental health, I don’t have a lot of background knowledge on either group. My understanding is that they are groups that are attempting to protect children from obscene material being shared in school and public libraries.

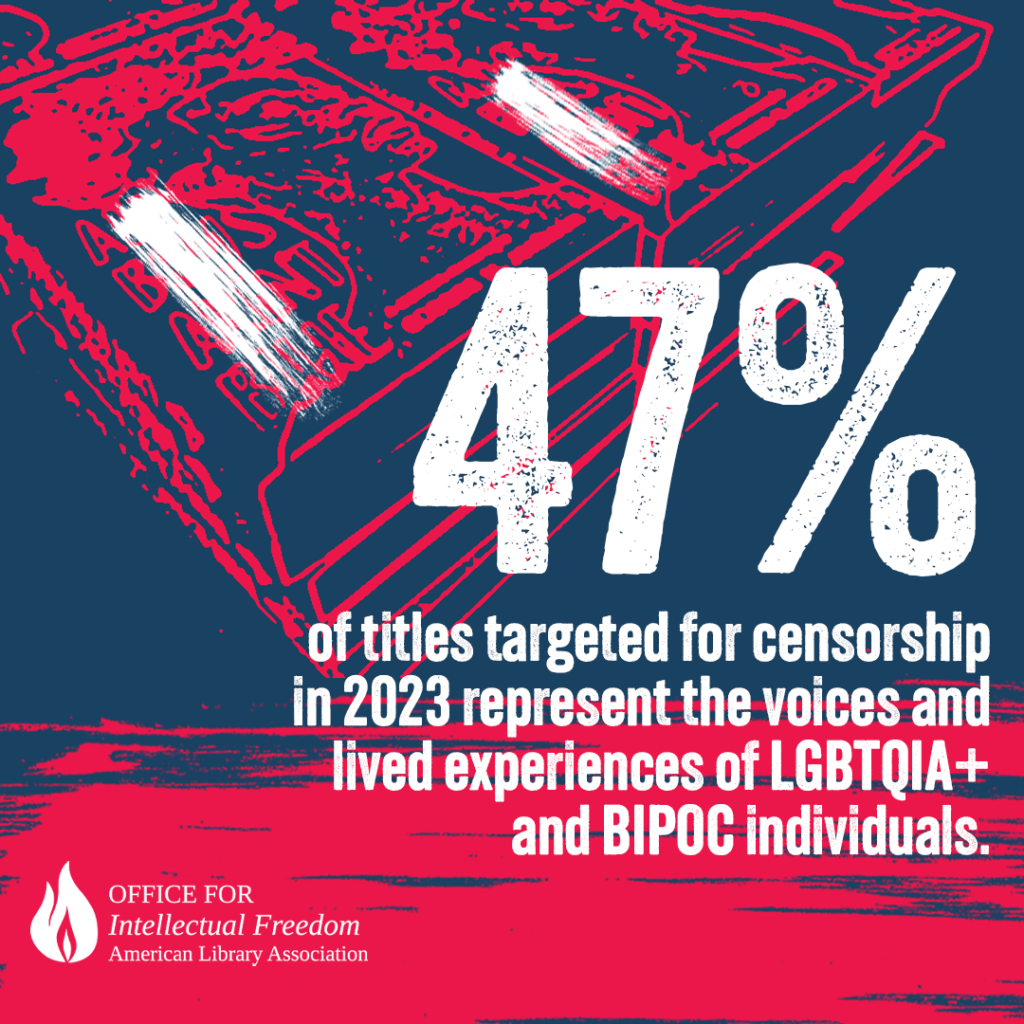

Forty-seven percent of the material mentioned in the American Library Association report about banned and challenged books are books representing LGBTQ authors, illustrators, and content, and/or BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) authors, illustrators, and content. So almost half are books about gay, lesbian, transgender, bisexual, questioning people or Black, Indigenous, and people of color. And those are the books that overwhelmingly are brought up by these groups. There’s a Facebook group called “Mary in the Library” and this group just lists books that they find obscene and then encourages their followers to find out if their local library or school library has that book and encourages them to fill out a request for reconsideration without having read the book and with no understanding of its literary merit.

AA: Wow, okay. Well, I’m just pausing to consider that you said these are people who are concerned about obscenity for children. And one thing that I notice so often is that often there’s a seed of truth and of good principles in just about any thinking person, right? Or in an organization, there’s going to be something there that has merit. And I would say that any decent person wants to protect children from real obscenity, right? Nobody wants harmful or explicitly sexual material to be available to kindergartners, right, Casey?

CO: Correct! Yes, I don’t know any librarian that went into librarianship hoping to corrupt children. We work in children’s librarianship because we love working with children. I am one of the luckiest people ever to get to work with so many amazing, intelligent, intuitive, curious children. It really is the best. No one goes into this work wanting to harm a child at all.

AA: Of course. And you’re a mom!

CO: Yes.

AA: What is your philosophy, then, on children’s access to books, and how do you make those choices about what’s appropriate for which ages?

CO: Yes. My personal philosophy is that access to books is central in a free society. That a society that is democratic, founded on democratic principles, and that lauds itself as a place of freedom for all, provides free and open access to materials.

AA: Can I pause right there and just say… Because the alternative to that is what? Let’s just mention that for a second. Because if you don’t have free access to materials, that means somebody is deciding what we can have access to and that sounds like other countries that I’m thinking of like North Korea or Nazi Germany.

CO: Yes, and book burning and book banning were central to those types of government philosophies. I just got back from Washington D.C., I was chaperoning the eighth-grade trip, which was a hoot. And we visited the Holocaust Museum and there was a huge display of photographs of books being burned. They were trying to destroy a culture by destroying anything that represented that lived experience, and that is part of what happens in societies that suppress free thinking and free ideas. It does mean that lots of different ideas end up being accessible in the library. There are libraries that have Mein Kampf in the library collection because it is a book and it has, if not literary merit, it certainly has historical significance. We have Bibles in the library, we have a specific section with religious texts because it is a book that has historical significance. I don’t have to agree, and I often don’t agree, with every idea in my library or any library. The idea is that all of those ideas should be available so that people can freely choose what kind of human being they want to be in the world and how they want to engage in society. So it isn’t open access to everything I believe in, it’s open access to all of it.

Now, the access does have to be developmentally appropriate. And, it’s funny, when I worked in the public library we had a program, which many libraries have, which is wonderful, called “1,000 Books Before Kindergarten” and parents are encouraged to read to their children 1,000 books before they get into kindergarten to set them up for success once they reach kindergarten and begin learning how to read. And I would say to parents, “You don’t have to read Shakespeare. Your child will be just as happy with the side of a cereal box or a billboard or The Cat in the Hat 75 times or The Very Hungry Caterpillar 50 times.” The content should be developmentally appropriate for the child. So access is also affected by what’s developmentally appropriate based on what children can understand. And I think that children deserve to learn about the world around them in a developmentally appropriate way. What is being censored is the content itself, the ideas behind it, not whether or not it’s appropriate. So I think that open access should be developmentally appropriate and all ideas are welcome and children ultimately get to decide what they’re interested in and what they’re not interested in. And they have very strong opinions about that, definitely. Even little ones have very strong opinions about what they like and what they don’t. I don’t think we give children enough credit for their ability to discern what is right for them.

AA: So who decides what is developmentally appropriate? I know that even among my friends who are parents, the age at which they chose to tell them about reproduction and introducing that topic, there’s a huge variety and spectrum. Some parents just tell the kids when they’re little, tiny, so they grow up knowing it their whole lives, and some people make it a big rite of passage when they get a lot older and they don’t think it’s appropriate for young kids. Who determines what is appropriate for, let’s say, a kindergartner? A five year-old goes into the library and their parent takes them to the young children’s section. Who decides what’s going to be in that section? Does it depend on the location so whoever the librarian is at that location gets to choose, or is there a national standard of which content goes with this age? How does that work?

CO: Yeah, that’s a great question. It actually begins with the publishers. If you go on Amazon and you look up a children’s book, in the description it will say what ages it is intended for. A lot of times, that will depend on, if you’re talking about very young children, how many words are on the page. Is it designed to help teach them how to read or is it designed as a story and picture book is the format that the author and illustrator use to tell that story? There are picture books that content-wise are not young-child appropriate that I have read that I’ve loved. That’s when a librarian can be helpful to walk through, “This does look like a really engaging picture book, but the content or the language is really for a 3rd through 5th grader.” I think it starts with the publisher and when the books end up in the library, it just depends. I worked in a small public library and I did all of the ordering as the manager for children and teens. And I worked with my colleagues to make sure, because we had a teen librarian so she would give me suggestions, and we had an early literacy librarian who would give me suggestions. And then we would place orders and put the books out in the school.

Some schools have a budget to purchase materials, some schools do not. One of the issues of inequity is that school libraries that don’t have resources will oftentimes have collections that, in terms of publication, the average age of the collection is 1991-1994. That’s very common, particularly in school districts that don’t have extra funds for new books. So the content, if it’s delivered in a developmentally appropriate way, oftentimes will just be an introduction to something. For example, there’s a wonderful picture book called Bathe the Cat and it’s by Alice B. McGinty. I just saw it on the list the other day for next year for our school. It is a family that is getting ready for grandma to come visit and somebody is supposed to bathe the cat, and the cat keeps moving the magnets on the to-do list so they don’t have to be bathed and so all of the to-do list gets messed up. So, somebody’s vacuuming the lawn, it’s very Amelia Bedelia and the kids love it.

And there are two dads in the family. Now, the words “gay” or “homosexual” never come up. It’s never even mentioned. It’s just that the two parents happen to be two dads. So that concept is part of the story, but it’s not the focus of the story. And books like that can open up conversations. I’ve read that book before and I’ll have a kid that says, “Oh, that’s two dads. I have two dads!” Or I will have a student say, “What happened to the mom? Where’s the mom?” And then we talk about how in some families there isn’t a mom. Maybe there was a mom and now there’s a dad. “Maybe mom lives down the street like my family.” And it actually triggers conversations which then can also be discussed with the parent. So a lot of it is concepts and ideas put forth. And again, kids are so intelligent. They’re so receptive and curious, and they want to understand the world around them. And again, all of this is reality. It’s things that people are already seeing when you go to the grocery store, when you go to school. You’re seeing people who don’t look like you, or whose parents are not like yours, or whose home or culture is not like yours. It’s not that anything’s being brought up that isn’t already there.

For example, with reproduction, you may have a story about a child who’s getting ready for a new sibling. Ezra Jack Keats has the book Peter’s Chair, and I think Peter is the little boy from A Snowy Day. I believe that’s the one where he’s getting ready for a sibling and he doesn’t want to give away his chair to his sibling. I believe that’s what happens. So there’s the idea of a new baby without necessarily breaking down how the baby is made. It can trigger a conversation about how things happen, and then parents are allowed to choose how they want those conversations to go. All librarians, I usually don’t speak for all of us, but I will say that children’s librarians want to work in partnership with parents. They want to support what the parents are doing at home with their kids. We want to talk to parents about what is right for their child.

We actually celebrate Banned Books Week at the end of September every year, and one of the things I tell the children, even as young as first grade, is, “If your parent tells you that you can’t read a book, is that censorship?” And they’ll all say, “Yes.” And I’ll say, “No, that’s parenting. Your parent knows what’s best for you. But if your parent decides that no kid can read the book, that’s censorship. Your parent’s decision for you is parenting. Your parent knows what’s best for you.” And I have had wonderful conversations with parents who were very clear about the boundaries they had for their child and what they wanted their child to read, but came to me respectfully, kindly, in a friendly way. And we’ve had great conversations and I wholeheartedly support what those children are learning in conjunction with their families. It’s morals and beliefs and ethics. I certainly don’t want to overstep parents in any way.

It’s when people are unwilling to have that conversation that things get really difficult. And the fear that some of these groups foster in parents… I watched a video once on Instagram or TikTok and it was a parent crying because she truly believed that a specific book was going to harm her kid and she was adamant that she was not going to allow it and she would see it through to the end. I mean, she was crying over a book! The thought that this book would be in the library was devastating to her because of the fear that it was harmful to children. And someone in that level of fear, it’s very hard to have any kind of rational conversation when one person is so afraid. And these groups foster that kind of fear. They stir the pot and make having rational conversations extraordinarily difficult. And that’s a shame because I think librarians can go a long way in reassuring parents that we are here to work with you and not to harm you or your child or your relationship with your child.

AA: One thing that comes to my mind is that I so appreciate hearing you articulate that a parent’s decision of whether the child is allowed to read a certain book is parenting. That’s so validating and reassuring. It should be reassuring for that mom who is crying, saying, “No one is going to make your kid read this book. You can do that parenting, but you can’t decide that my child can’t read that book.” Growing up as an LDS person, Mormon, there were tons of things that I was exposed to out in the world that my parents said like, “Yeah, all your friends might drink alcohol, but we don’t.” My parents instilled that in me. So I would see it all the time and I’m like, “Oh yeah, that’s fine for them to do, it’s not fine for me to do.”

And teaching our children to have those – whatever they are, whether it comes from religion or just their own family’s moral code. To say “That’s not for me, but I get it that other people do it.” When my son was little he had a Hindu friend, he had lots of Hindu friends actually, but this one particular one was so, so, so devoutly vegetarian and would cry at lunch when other kids ate meat. You know, I felt really tender for him and it’s very hard at that age to say that this thing that means so much to me means something different to other people, but we need to learn that in a pluralistic, democratic society it’s important to differentiate and allow other people to have different beliefs. And kids need to learn how to do that for themselves.

we are here to work with you and not to harm you or your child or your relationship with your child

CO: Yes, in order to get along with other people. Absolutely. And I think you bring up an excellent point in that parents can say, “Other people may do this but we don’t.” Or, “Other children may do this and we choose not to.” I think the challenge and where my frustration comes in is with groups that are trying to challenge these wide swaths of really incredible materials. Titles, to me, are works of art. And they are doing so in order to avoid acknowledging the ideas or the topics altogether. And we cannot continue, especially in this culture where children can see everything on their phones all the time, things that are way not developmentally appropriate, I would argue, where they can watch it without any kind of supervision. We cannot continue as a society to pretend that certain things aren’t happening, or pretend that certain people don’t exist, or certain philosophies or ideas don’t exist, because that’s not reassuring to children. In my opinion, children want to be seen and heard and want their reality acknowledged. Maybe not confirmed, but at least acknowledged. For one family to say, “We don’t talk about families that aren’t a mother and a father,” and then to go to school and see a family that has two fathers or two mothers or one mother or one father, to tell a child that what they’re experiencing isn’t valid is incredibly traumatizing. And that’s why books are so important, because sometimes a child just needs validation that what they are seeing or experiencing is accurate.

One book that got a lot of pushback several years ago now is an amazing graphic novel, it’s a series now, by Jennifer Holm. The main character’s name is Sunny, and in the first book, her brother has a significant drug problem. He’s an older brother in high school and she’s younger, and she is sent to be with her grandfather in Florida while her parents try to figure out how to help her brother. And there was a lot of pushback within the librarian community. Why are we sharing books with kids with siblings who have drug problems? They’re too young. They should be innocent for as long as possible. And yet, there are so many children for whom that is their lived reality, or children who have a friend or a relative where that is their lived reality. So if you’re denying kids access to protect their innocence by basically denying that things that are actually happening to children are not happening… I will never understand that as long as I live. I’m not saying your child has to read it, but that book is going to help somebody. They’re not the only one. So to limit access based on a perception of protecting children is just maddening because to deny reality is harmful to children and to adults.

AA: What are the actual rules or laws? You kind of talked about how different designations are made for age appropriateness, but what are the laws when a parent says “I’m going to challenge this”? What’s the legal structure around that?

CO: Yes. So, it depends. It actually varies by state, sometimes by county, sometimes by school district. In Indiana, a law was passed in 2023 that schools and public libraries are required to have policies and procedures in place when a parent or a patron wants a request for reconsideration. So my school district has a form and the public library where I worked has a form. The form must be filled out and then there is a specific procedure that kicks into place. And that is across the state. Every school and public library is required by law to have such a policy, which many advocates for freedom to access, including myself, believe in. Because without a policy, it is much more difficult to fight back. The policy gives a structure that actually can protect the library and the librarians because it makes it very clear what will happen and what will be followed and how everything will be handled. That’s actually a good thing, in my opinion.

We are also required to make our library catalog publicly available. Our school library works in partnership with the Indianapolis Public Library and their catalog is online, so any parent can look up a book title, check where it is available, and see if our school has a copy. Again, that’s not anything that is new or bad. I encourage people if they are interested, if a specific book is in a school or public library, look it up, go get it, check it out, read it. Look up the professional reviews regarding the book in order to make a decision. And then the one thing that sort of got everybody’s attention is that the law also says that we are not allowed to share material that is “obscene”. And there are guidelines for distinguishing what is considered legally obscene, but as we’ve seen throughout history, the definition, particularly the legal definition of obscenity, is a bit ambiguous. And that ambiguity opens the door for people to say all sorts of things are obscene when they do not meet the legal standard of obscenity. For example, a book with a pregnant woman in it, someone could say that’s obscene. On television, you used to not be able to even say the word “pregnant” because it was unacceptable. Lucille Ball was “with child” in I Love Lucy.

AA: Wow.

CO: It really is a standard that in its ambiguity can cause a lot of problems for everyone. The other thing that was a big deal when the law was passed last year is that they removed any protection for librarians for sharing material in an educational manner. So, if I read a book aloud that has two dads and a parent complains that it’s obscene, if the book has educational and literary merit, I am protected as an educator. That was removed and it was replaced with language saying that if it was within the scope of my employment, then I’m protected. But originally in the bill, if the district chose not to remove the book, a parent could go to the police department and file charges against me for providing obscene material to minors, which is a felony in the state of Indiana. And in the state of Florida, there are people, and you can look it up, you can see videos of them in the police station, talking to officers about filing charges against public librarians for books they’re reading during story time. So this idea that there was a lot of pushback in Indiana of, “Well, that’s not actually going to happen,” you never know. Once it’s enshrined in law, that’s a scary thing. A lot of librarians I know are really questioning whether or not they want to continue in a profession where their livelihood and their personal freedom could be at risk because somebody has an opinion about what’s appropriate.

AA: Crazy.

CO: It is! It’s maddening. There are stories everywhere. I just came across one about a tiny little library in a log cabin in Idaho that serves a community of 250 people. And Idaho just passed a law, or it will go into effect on July 1st, 2024, that says that any community member can ask to have a book moved from the children’s section to another section of the library where the child can’t access it because they deem it inappropriate. And because this library is so small and the staff is so small, they literally don’t have a shelf far enough away from the children’s shelves. You can stand at the children’s shelves, reach out your arm, and touch the adult section. And because they also don’t have the funding to have a lawyer on retainer to deal with objections, they are putting into place a policy that this library will no longer be open to patrons under the age of 18.

AA: Wow.

CO: So children, unless they are with a parent, are not allowed to go in their own public library because the library is trying to protect themselves against the legal ramifications of somebody trying to get books moved out of the children’s section. Also in the state of Indiana, one of the other beautiful, lovely – and I’m being sarcastic – things about this law is that any member of a community can file a request for reconsideration of a book in a school library, regardless of whether or not they have children in that school, children in the school system, or children full stop. So anyone in the community around my school can request that something be removed from the library regardless of whether or not they have children in my school or in any school, or have children at all.

AA: Oh my word. So someone curmudgeonly– or someone of a different generation who grew up not being able to say the word “pregnant” and thinks it is obscene to show a pregnant character can just, at the very best, it sounds like, create a ton of paperwork and headache for you having to deal with it, or even worse.

CO: Yes.

AA: Have you ever been challenged by a parent? Have you had someone come after you?

CO: I had my first experience this past school year. I’d never gone through it before and I hope to never go through it again. But I did have a parent that was new to our building. We were a K-8 school and next year we’re transitioning into being a pre-K through 5 school. But as a K-8 building, we had a teen section that was separate from the school but not limited from the books for younger kids. So younger kids could go into the teen section, and did occasionally, and a student borrowed some books. It wasn’t a student I knew well because they were new to the building. And generally if they want to check out a teen book, I will err on the preferences of the kid. And again, if there’s an issue, the parent can always come talk to me. And that happened on a Wednesday. On Friday I was paged to the office and went in and there was an extremely angry parent who had four books stacked up next to her on an end table. And I looked at the spines and I knew instantly that three of the four were teen books and all four had gay male characters. And I immediately thought, “This is not going to be good.” I didn’t even know whose parent it was, because, again, it was a family that was relatively new to the building. And I have 450 students, so I don’t get to meet all the parents.

And she wanted to talk. I was actually covering a class because we were short staffed, and I told her that I would have to cover the class for at least 20 more minutes. She didn’t want to wait. I gave her my email and she sent an email with her concerns and screenshots. All four books were graphic novels so she had issues with both the artwork and the language. I responded and actually said, “I’m so glad that your child was able to come to you and talk to you about these books and that you had an open conversation. Thank you so much for letting me know, and I’ll be sure to direct your child to more appropriate material in the future.” And I got an almost immediate response suggesting, not requesting, but suggesting that the books be removed from the library. That they weren’t appropriate for an elementary library, which we aren’t because we’re for K-8. And I chose not to respond. She was very clear about how she felt, and I didn’t think that responding after that would be helpful in any way. And so I left it alone.

And about a week later, I got another email saying that because she and her husband could not be in the building to monitor what her children were checking out, they were not allowed to check out books anymore. And as I was reading the email a staff person came in, one of my colleagues, and said, “Are you okay?” And I was thinking about the email and I said, “Well, not really.” And my coworker said, “I was wondering after that Facebook page thing.” And our school has a private parent and staff Facebook page. I’m not on it because I find that Facebook does not bring out the best in anyone, and I don’t ever want my feelings about anyone to be impacted by stuff I read on social media. Often when it’s written in the heat of the moment it’s just not something I’m interested in. So I’m not on the Facebook page, but many staff members are, and she showed me that the parent had gone on Facebook and talked about how unhappy she was about how her child had been able to access these books. She said something to the effect of that I wasn’t doing my job because her child had access to these books. And that was really hard.

Fortunately, my colleagues and many of the parents were extremely supportive of me, of the library, of the freedom to choose, and that felt great. But it was a really awful experience. It was embarrassing. It’s embarrassing to have someone say publicly that I’m bad at my job. I take a lot of pride in that. I had shame because I didn’t know if I handled it the correct way. I was angry and yet I knew that if I joined the Facebook group and started typing in responses, it wasn’t going to make anything better. I also was very frustrated because none of the emails or the Facebook post acknowledged anything about the books being about gay characters. The complaint about the books was that one page showed two young men in bed together, not doing anything, just laying next to each other. And the parents said that because one of them said they were depressed, there were concerns about mental health concepts being shared with kids.

AA: Oh boy.

CO: Nobody ever said “gay”. Nobody ever said it. And I just got so frustrated that someone couldn’t talk about the book and not be honest about the fears or the concerns or anything else. Because the discussion changes when a person says, “I don’t want my kids reading books with gay characters in them.” It’s sort of like how groups don’t want to acknowledge fighting against books with BIPOC characters in them. And they say, you know, “The Civil War is inappropriate for kids because it was such a horrible event” instead of saying, “I don’t want my child to learn that white people owned human beings legally. I don’t want my child to learn about what white people have done.” And so it’s couched in something else.

AA: Yep.

CO: And that is infuriating and discouraging. Even talking about it now I’m a little bit calmer, but for a while every time I would talk about it I would shake and cry. It is a terrible feeling to have someone think that I’m not doing my job and that I’m openly trying to harm children. It is a terrible thing and I don’t want to go through it again. And yet I am not backing down from my belief that if there is an issue that a parent can come talk to me, but I’m going to defer to the child’s interest and curiosity first. Even though it is really scary because it does not feel good to be the recipient of the kind of anger and fear that some parents have.

AA: That would be so awful and like an impossible job for you to guess what different kids’ parents would be okay with. I can just imagine that if you did interfere, I mean, you’re just between a rock and a hard place, right? If you did interfere, then a parent would be like, “What are you doing saying that my kid can’t check out a Bible?” if you were to say no. Or “Why did you say no to my child doing this?” I just feel like you have to, again, unless it’s a really egregious breach of like “Whoa, where’d you get this book? That’s maybe for an older kid.” I imagine that if it’s very very obvious then you would say, “Uh oh, go put that back, honey.” But especially if you’ve got 450 kids, like you said, I just don’t think that’s your job. This is just me opining. This is just my opinion after hearing about it.

But again, it has to be an open democracy with freedom of ideas that are there. And I guess I really don’t have that much sympathy for parents like this because, like I said, with my own experience, I grew up as a kid knowing that I was going to have to use my own moral compass, my own critical thinking skills, because I would confront all kinds of stuff that would go against my family’s values. I just knew that, and it was up to me. And if I secretly went and read every Judy Blume book in the library, which I totally did, that’s not the librarian’s fault! That’s because I was really curious about those topics. And like you said, kids are smart. Now this boy that checked out those four books about gay characters, he’s just going to do it in secret now. But that’s not your problem!

CO: It’s an opportunity for a conversation.

AA: Yes.

CO: And so many parents are able to have those conversations, but the ones who can’t, that anger and fear is difficult. You can’t come to any kind of consensus.

AA: Yeah, that would be really hard. One more topic that I wanted to ask about, which you did mention and I was hoping we would circle back to, is the BIPOC issue. Because at least I can understand if it’s material that is in any way sexual. It is understandable to me that a parent could have a different definition of what obscenity is than another parent. But what on earth? With characters of color or authors of color, I guess you did touch on a little bit, it’s basically critical race theory, right? CRT. Why would a parent object to a book that has to do with people of color?

they say “The Civil War is inappropriate for kids…” instead of saying, “I don’t want my child to learn that white people owned human beings”

CO: Yes. I think that critical race theory, in my very limited need-for-more-education opinion, is a talking point that says that the way that history has been taught, the way that society has treated people of color was okay then, even if we know different now. And there is a desire not to change any of that or to chalk things up to, “Well, that’s just how people used to think.” There’s a great example from when I served on the Children’s Literature Legacy Award committee this year. That award used to be named the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award. I was a huge fan of Laura Ingalls Wilder. I read all the books, I have all the books. I gave them to my daughter, I love the TV show, all of it. Huge fan. And years ago, maybe 2015 or 2016, maybe even earlier, the American Library Association began to have discussions about naming an award. And that award specifically honors a children’s author or illustrator who has been publishing for at least 20 years and who has had a significant positive impact on the lives of children, so it is a huge honor. And to name that award after Laura Ingalls Wilder, knowing that now as we look back on her books, there are very derogatory terms and scenes that involve Black people, indigenous Native Americans, women… I mean, if you go back and you look at the books and appreciate what we know now, she is not an example of someone we would give the award to now because her books contain this content. It doesn’t diminish her ability as a writer or the success of those books, but it is saying we want the award to have a name that fully represents an author or illustrator that wins it now.

So there was a vote, lots of contentious discussion, and then they renamed the award the Children’s Literature Legacy Award. As a fan of Laura Ingalls Wilder, it breaks my heart because I loved her books growing up. And as an adult who can think critically, who can appreciate and have compassion for a child from one of those groups being read aloud to and seeing Pa and his friends dancing in blackface, which is illustrated in one of the books, I can appreciate that it’s no longer representative of the kind of literature that speaks to the society we want to live in, that we aspire to be as human beings, which is honoring all children, all cultures, all lived experiences. But the pushback, of course, was “woke librarians throw Laura Ingalls Wilder to the side in honor of new critical race theory,” you know, all this baloney. All these things were thrown out at the time. I think the argument is, “Why can’t we just keep things the same way?” And I think that BIPOC authors, particularly BIPOC female authors and illustrators are the ones in the front lines saying “This is my lived experience and it deserves to be a part of the conversation.”

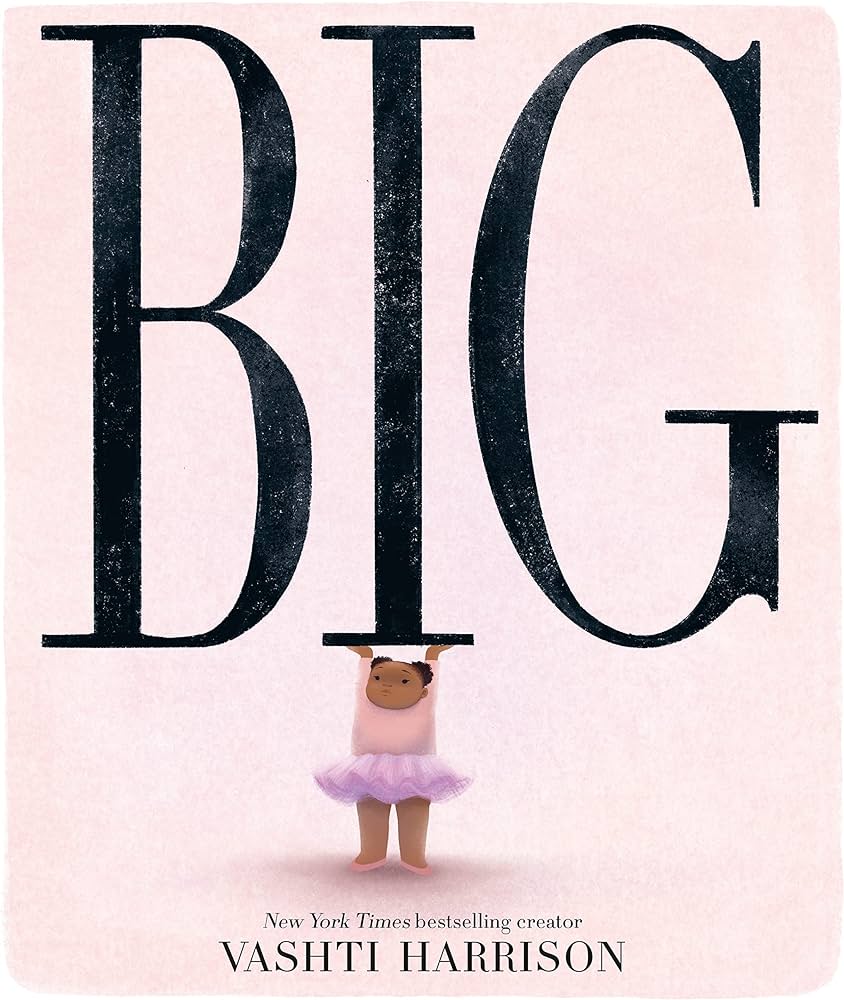

The first book that ever had a Black child on the cover was The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats, who was Jewish. He was not Black. He saw a photograph of a little Black boy playing in the water of a fire hydrant in New York City and he put it on his bulletin board and said, “I want to write a book for that boy,” recognizing that that had never been done. But it took an author that was not Black to even get that published in the 1960s. And that one was the first. We now have, in 2024, the Caldecott winner, which is the medal for the most distinguished illustrations in a picture book for children from the previous year, and the winner is Vashti Harrison. She’s an amazing illustrator. This is the first book she’s both authored and illustrated. It’s called Big and it’s about a little girl who as a baby and toddler is always told, “You’re such a big girl.” And as she grows up and she’s bigger than her peers, “big girl” takes on a different connotation. The book is incredible. I read it to every grade at my school because of how amazing it is. But she’s the first African American female, in almost a hundred years of that medal being issued, to win that award.

AA: Oh my word. That’s insane to me.

CO: Yes. So for society to say, “Yeah, yeah, we know about all of this stuff. Why do we have to talk about it? Why do we have to read books with BIPOC characters?” Because we’re still not achieving equal representation in books for children about children of color and about cultures other than white, Christian, cisgender, heteronormative family structures. That is still the default. So there are some amazing BIPOC female authors and illustrators, Vashti Harrison included, who are really leading the way. We have Ellen Oh and Malinda Lo, who created We Need Diverse Books. They were tweeting about not being invited to speak on a panel of authors where all the authors on the panel were children’s authors and they were all white and male in 2014. And they created a hashtag that then became this organization and you can go to diversebooks.org and find lesson plans and book lists and suggestions and publishing opportunities, and all of these things for BIPOC children’s authors and illustrators.

Carole Boston Weatherford is another one. She is single-handedly redoing children’s biography collections by writing books about Black history, picture books, and poetry books. She’s this incredible poet. She wrote We Can Fly about the Tuskegee Airmen, which is – oh my gosh – there are a million things I learned and then I have to Google everything to look up pictures of everybody. She recently published a picture book called How Do You Spell Unfair? about the first black participant in the National Spelling Bee. And it has this beautiful author’s note about how this young teenage girl got all of this attention, but it never turned into money for college. Her family didn’t have money and she became a maid in a white household and died in her fifties. Because even though she had this opportunity, there was never any follow-through to help her achieve anything beyond that. She works with all of these incredible illustrators. You can go to a current picture book biography collection and her work is everywhere about all of these unsung heroes and all of these moments in Black American history that are never talked about, which is amazing.

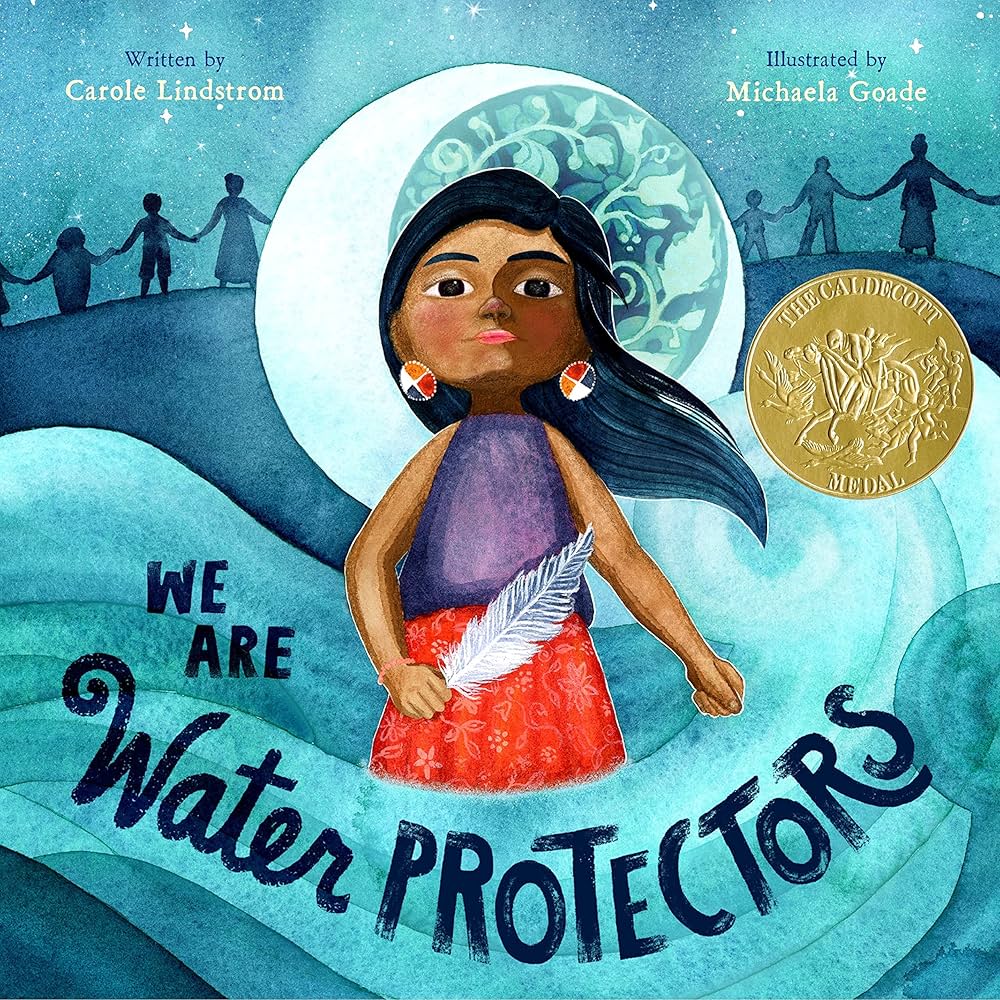

And then there’s been a real influx of indigenous authors as well. We Are Water Protectors, which is by Carole Lindstrom, who is Native American, and illustrated by Michaela Goade, who is also Native American. It’s a beautiful story about protecting the water, the Standing Rock protests, and it’s written in such a developmentally appropriate way. The oil is depicted as a snake and the kids have this incredible connection with standing up for what they believe in and wanting clean water and how it benefits everyone. Again, it’s a very big concept that is shared in such an appropriate and engaging way. But if I said, “We’re talking about the Standing Rock protests with kindergartners,” parents might think I’ve lost my mind. That was the Caldecott winner two years ago, I think. There are so many voices that are wanting to be heard, and publishers just now are making the effort to publish those stories because people want them and will buy them.

It’s sort of like when Barbie came out and everyone said that no one’s going to go see a movie produced by a woman and directed by a woman about a doll. And everyone went to see it. It’s this idea that stories by marginalized groups do sell, they do win awards, they do get attention, they are a financially viable way to bring these voices into children’s literature in a way that’s not happening, in my opinion, in any other genre. It is an amazing time to be sharing books with kids. The problem is that I don’t have enough weeks in the school year to share them all! I have to really limit it. When we have a day off for a holiday, I think, “Oh, I was going to share that book!” So yeah, it’s really a remarkable profession to be a part of. The amount of work that’s being done to make our society a better place through this art is extraordinary, and people are not backing down, which I’m really thrilled about.

AA: One quick thing that I wanted to hit on, Casey, is other instances of inequities in libraries. We talked about this a little bit before we started the episode and I thought this was a really important one to bring up.

CO: Yeah. Money is a huge issue when it comes to equity in libraries. Communities that have access to more financial resources have more diverse collections and they have more current collections. Again, in the district where I work, which is a large urban school district, the average publication year of the books in the collections is 1994. So the quality of materials and access to more current materials that do bring in different perspectives and philosophies and ideas, those opportunities are limited if communities do not have the funding for a decent collection and a safe building. And I can travel north from Indianapolis and come to communities whose libraries are stunning. I mean, they look like a shopping mall. And then I can travel to a community, again, I think about that library in Idaho that’s in a log cabin where everything is shoved into one place. The idea is the same, the quality of services– that library in Idaho is ranked 98th out of 100 in size, but is in the 50th percentile for quality of services. Librarians will always do their best with what they have, but it creates inequity when there’s not the same amount of money dispersed. And that goes for school libraries and public libraries.

Also, publishing and librarianship is primarily female still. I think the last percentage I saw was something like 85%. Both publishing and librarianship are primarily white, female, cisgender, abled, and heterosexual. So if the people making the decisions about what is available all fall into a specific category, it is less likely that varying viewpoints will be represented in the collections, in the quality of services, and in the staff. Staffing is a huge issue right now in librarianship when it comes to including more perspectives. I would say that libraries are trying to diversify their hiring, but it’s not just getting people of color or people from different cultural groups or people of different genders and orientations in the door. It’s what happens to them once they’re there. And if you are a library that does not have policies and procedures in place to help people who are not white, female, cisgender, abled, and heterosexual to thrive, those people are not going to last very long in your library. There are definitely issues in librarianship about equity that are still being addressed on the librarian side in order to make services and materials more equitable for everyone.

AA: Is there an issue with late fees for books, too?

CO: Yes. Many libraries are getting rid of that because the late fees are punitive primarily for people who have economic challenges. For example, our public library and our school library don’t do late fees. I will often waive fines, if I can, for lost materials. It’s part of doing business. I’d rather have a book in somebody’s home where the kid can read it than sitting on a shelf in the library. We want the library to be free and accessible for all, and the more fines we pile onto children and families, the less likely they are to use library services. And there are parents who run up fines checking out DVDs on their child’s library card. It does happen, but I would say that’s the exception and not the rule. We want people to have access to library services as much as possible.

AA: Well, Casey, I’ve learned so much from you today. I’m really, really grateful for all of this wisdom and life experience and all of your expertise from your career that you brought to this conversation. Thank you so much for the work you do in the world, and thanks for being with us today. I really enjoyed our conversation.

CO: Me too! Thank you so much for asking me and for asking such great questions. It’s not a job that gets a lot of attention, but it’s a job that’s very close to my heart and I’m very passionate about it. So to get to talk about that passion for an hour plus is wonderful for me, so thank you.

AA: Well, it’s hugely important in breaking down patriarchy because the books that children read will affect the adults that they become, which will determine the society that we will all live in. So, you are doing a tremendously important job, and thanks again.

CO: Thank you.

all of those ideas should be available so that people can freely choose

what kind of human being they want to be in the world

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!