“we’re with the Earth now, we need the Earth, so let’s take care of her”

Amy and Dr. Gina Colvin discuss Māori history, culture, and why feminism may not be necessary in a Māori context.

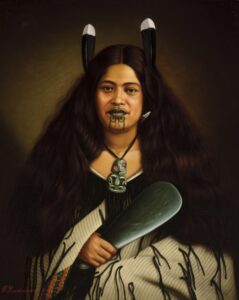

Our Guest

Dr. Gina Colvin

Gina Colvin is a New Zealander of Māori, English, Irish, Welsh, German and French descent. Until the July of 2016, she was in the permanent position of Lecturer at the University of Canterbury. Dr. Colvin served UC for 12 years across Political Science and Communication, School of Māori and Cultural Development, and more recently the School of Educational Studies and Leadership. She currently serves as the Māori Cultural Advisor at the Salvation Army New Zealand.

Gina’s primary academic interest is in the history and future of ideas. Whether faith, belief, ideologies, symbols, representations or discourses, all communicate powerful ideas that at the same time express hope for, or hope in some kind of social action. Whether expressed in educational, religious, or political contexts my research interests are in understanding how and why particular ideas flower, change, get disrupted, are silenced, or become dogmas, and how these same ideas translate into social, political, and cultural realities.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Some time between the year 1280 and 1350, a group of seafaring Polynesian people reached the shores of an uninhabited island group that was the last remaining landmass on Earth to be settled by humans. The people called themselves Māori and they named their home Aotearoa. Four hundred years later, Europeans would arrive and call the islands New Zealand. Using mitochondrial DNA evidence, scientists have traced current Māori people back to between 50 and 100 women who were among the original settlers of the islands. And I would give anything to know what their lives were like as they traveled across the ocean and made a new home. And I’m so grateful to have learned more about Māori history for this episode, and I’m super excited to be able to discuss it with someone I admire so very much, Gina Colvin. Welcome to the podcast, Gina!

Gina Colvin: Tēnā rā koe, he mihi nui ki a koe, Amy.

AA: Thank you so much for being here. I’d like to start the episode by asking you to introduce yourself. Tell us where you’re from, a little bit about your family of origin and your education, your work, and some things that make you who you are and have led you to the work you do.

GC: Kia ora, Amy! I think in these situations I feel a little awkward because I would usually do this in Māori. But I’m going to give you a bit of a translation. If you take the North Island of New Zealand and you look at it as if it were an upside down skate, an upside down stingray, my people come from the tail of the stingray, that’s Northland. And then if you look to the right there’s a flap like on the stingray and that is where the other side of my people come from. And the people associated with Northland are Ngāpuhi and the people associated with the east coast we call Te Tairāwhiti as Ngāti Porou. And “ngāti” just means “descended from”. So I’m descended from people from the Puhi, and there’s a big story about that, Porourangi, who was a descendant of the original whale rider, Paikea, who by legend made his way on the back of a whale to New Zealand.

AA: Wow.

GC: So that’s kind of my history, and currently I live in Christchurch in the South Island, in the “canoe of Māui” we call it, Te Waka a Māui. And here I live with my husband Nathan and we have six boys, four still at home, unfortunately! I’d like them to move out.

AA: Hahaha! I love that. I love the honesty, that’s so great. Well, I hadn’t planned to ask you this question but your introduction was so beautiful in Māori, and that leads me to the question, did you grow up speaking Māori? And is that an introduction you would do any time you meet a new person?

GC: In a New Zealand context, absolutely. And I would give it all in Māori because people here are reasonably used to the format, it’s called a mihi. So we’re used to the format. And some people don’t know exactly what’s going on, well they know what’s going on but not necessarily word for word. But I didn’t grow up with Te Reo, Te Reo is our word for the language.

AA: Oh, thank you.

GC: I grew up around a lot of Māori aunties, particularly in the LDS Church. I don’t think that you’d find many Māori that weren’t associated in some way with the LDS Church in New Zealand. But I did grow up around the tikanga, the culture and the customs, not so much the language because there was a concerted effort by the New Zealand government to eradicate the use of Māori. And so people in my father’s generation were punished at school for speaking the language. And I remember listening to an older lady, we call them kuia, she said, “I only spoke Māori at home, and then when I went to school I wasn’t allowed to speak Māori.” And she said, “I had no thought. No language, no thought.” And from that, people of that generation were considered dumb.

But coming into the 1970s and 1980s there was an uptick in the Māori renaissance and resurgence. People looked at the state of affairs and thought, if we don’t do something we’re going to lose our language. And so now Māori is an official language in New Zealand, children receive instruction – not compulsory – but mostly instruction in the Māori language. And if you want to be any part of the public service, a teacher, you need to have been trained in understanding original documents like the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand history, and to have some facility with the language. That’s just the way of it now.

AA: That’s fantastic, what a great change. And so it’s optional in school, like you can enroll your kids in the language if you want to?

GC: That’s a good question, so we have a standard curriculum across the country. And I’m speaking because I used to be in education, I used to teach teachers. So part of our curriculum and our expectations for teachers is that they have some kind of competency. I don’t know that it’s policed particularly well. But, you know, there’s a kind of an agreement, a gentlewoman’s agreement, that people are going to be using the language and incorporating it into the daily life of the classroom.

AA: Got it.

GC: And the tikanga, and the customs.

AA: That’s awesome. Okay I do have to come back to one other thing you said, Gina, because that was so surprising to me. Why such a huge presence of the LDS Church in New Zealand?

GC: Okay, can I also say that I’m no longer LDS. And I always say this: my hands and feet are Christian, my head is Buddhist, and my heart is Māori. So I love working in Christian spaces, I’m formerly a member- I’m an Anglican in New Zealand and Community of Christ across the world. So internationally I’m Community of Christ. So, you know, I make it up as I wish to. But the question is a good one, and I think Mormons came, the LDS Church came to New Zealand in the 1870s. By that stage, we’d had a long history, a few generations of Christianity. And so Māori didn’t necessarily begin to join any particular church. I don’t think the concept of joining a church was of any particular interest, but they were building a relationship with missionaries. And so the Anglican Church in New Zealand, which is of course the Church of England, became the Hāhi Mihinare which is the “Missionaries Church”. And so it was very, very relational. When the Anglican Church proper came and began to establish an institution here and started building churches and brought their priesthood over, things changed considerably. Because as things are wont to go, the Church kind of grease the wheel of colonization.

So by the time the LDS Church decided to come and missionize or evangelize New Zealand, Māori had gone through a long history with the Anglicans, the Wesleyans, the Catholics in particular. And they had often sided with the settlers, the incoming settlers. And so because they’re mostly associated with England, a fresh American face on Christianity was actually really powerful. Because they have rotating missionary activity, they came and didn’t establish houses or try and buy land as such, and they learnt the language very, very quickly. They gave people the whole baptism for the dead, the gathering of names that we call whakapapa, and that part of the LDS tradition really resonated with Māori. The LDS eschatologies and theologies really synchronized well with Māori, or there was more room, I think, for syncretizing Māori and Mormonism. It gradually tightened up, as things do, that’s the pattern. Like okay, we have this kind of really liminal sharing of space, this really intercultural encounter. But now we need to get to the real business of establishing a church. And so the LDS Church didn’t respond particularly well to the renaissance. Māori wanted to be able to speak their own language in churches and there were a number of people who were told that that’s not acceptable. Only now in 2023 do you have Māori language branches and that’s in the North. But, you know, a lot of the damage has already been done.

AA: Yeah, that’s really interesting. I actually wasn’t aware of that, so that’s really fascinating. So, as we discussed, Gina, before we started this, we really want to focus on Māori custom and culture regarding gender. And this was really all new to me and I found it so beautiful and so powerful. So I thought maybe we could get into that by starting at the very beginning and having you share the Māori creation narrative with us.

GC: Okay, can I also say that I don’t speak for all Māori. In fact, the word Māori only came about when the non-Māori arrived. The word for non-Māori is pākehā. And they arrived and they were fair skinned and one story is that the patupaiarehe were a light-skinned mythical people and so the white people were called pākehā like haole in Hawai’i, pālagi in Samoa. And I can only give my story. And there really isn’t as such Māori, there are people from Ngāti Porou and there are people from Ngāpuhi and Tūwharetoa and Ngāi Tahu and there are lots and lots of tribes. And also, an urban Māori. So I’m going to give it a generic story and I say that because I don’t want an auntie going, “Ae, kua rongo ahau i a koe e korero ana mo Amerika. Kei te korero ahau mo Amerika. Kei te he koe.” which is “I heard you talking to that American lady and you are wrong.” Which is all very well. So I think you can only think about creation in terms of phases or stages of things coming into being. And we start with a creation period of potentiation which is called Te Kore, and then to night which is Te Pō, and then Te Ao Mārama which is the daylight. And somewhere in that creative period, that potentiation produced a masculine and a feminine. So a feminine came about and her name was Papatūānuku and the masculine was Ranginui. And in creation they were tightly woven together in this profoundly loving embrace. And within this small space between them they produced all these children. And it came about that the children were getting restless because they couldn’t move, they couldn’t be who they needed to be, they needed that freedom. And some of the children wanted to stay all tucked up inside the belly space of their parents. But one god called Tāne, who’s the god of living things up on the Earth, he pried the parents apart. Put his head to the belly of his mother and his feet to the belly of his father and pried them apart. So Ranginui shot up and became the sky, so he’s the sky father, and Papatūānuku is the Earth Mother. His brothers and sisters were Tangaroa, who’s the god of the sea, Tūmatauenga is the god of war, so everything sort of shot into their place, including the stars when this kind of creative thing happened. So that’s the story.

AA: I love the story. Did you grow up knowing that story or when did you learn it?

GC: Yeah, I can’t remember a time where I didn’t know the story.

AA: Which you learned in your family?

GC: Now I need to say I didn’t grow up with my father. In Māori I would say that my father liked to go around planting his seed into pākehā gardens. So he produced lots of different families.

AA: Understood.

GC: But my mother was always really, really supportive, but ignorant but quite supportive. But, I mean, I grew up in New Zealand so you just sort of know these things and I grew up really close to my Māori church family and many of them were my own kin. So yeah.

AA: Wonderful. Okay, the next question I was going to ask you is about the term mana wahine and then a linked term– just for listeners, Gina gave me articles to read and some podcasts to listen to so that we would have kind of a common vocabulary and common point of reference for the episode. And this term mana wahine was really interesting to me. Can you talk about that?

GC: Well, we’ve got to come back to the idea of mana. And mana is our inheritance from the gods, which gives one a sense of continuing worth. It gives one a sense of that potentiation, that you have spiritual quality and you have spiritual essence. So that’s what mana is. Now mana can come through your birth, it can be a birthright kind of mana. But mana is something that anybody can grow. They can live in their mana. And wahine is the feminine.

AA: So all human beings would have the mana and then the feminine-presenting would be the mana wahine, is that right?

GC: Yeah, it’s a particular kind of mana that belongs to the wahine, which is the female essence.

a feminine came about and her name was Papatūānuku and the masculine was Ranginui. And in creation they were tightly woven together in this profoundly loving embrace

AA: Okay, so one of the articles that you shared with me described the term feminist, and said that it could be translated in a certain way. And she unpacked the meanings of those three Māori words. Could you talk about those terms? And I don’t know how to pronounce them.

GC: Was it the kaikōkiri mana wāhine?

AA: Yes.

GC: Yeah, I think it was just kind of a translation thing, kaikōkiri. So kai is a prefix you use when you’re talking about somebody who does something, so if I’m teaching I’m ako and if I’m kaiako I’m a teacher. So it’s really an activist. Kōkiri is to activate something or to challenge something.

AA: Got it. So is this a term that’s common and is that a term that you would describe yourself with?

GC: No, well not a Māori context, I don’t really need to.

AA: Ooh, why?

GC: It’s not necessary because it’s all just there, you know? Feminism is really a white lady thing. And I understand it and I’m sympathetic to it, but it’s not actually that necessary to push myself as a woman in Māori contexts. Because the structures and the thinking is already there that give women their place.

AA: Hm. Even with the influence of European colonizers and the churches that you just listed, like the Christian churches? Did it not infiltrate into Māori culture or did it infiltrate for a time but there’s been a course correction? Because I have to be honest with you, this is one of the last podcasts that I’ve recorded for this year of women all over the world, this is the first time I’ve heard someone say something so incredibly hopeful. That gives me so much hope, that a woman’s like “yeah, I kind of don’t need feminism because the structure’s already equitable.” Never have I heard that. So I want you to talk about that a bit more.

GC: In Ao Māori, in the Māori World, we have rituals of approach and encounter. And if we start with the way people are welcomed into a tribal space, and you go with the structure of that, the masculine and the feminine weave together really, really beautifully. If you go out of that structure and you do something else, then that’s cause for concern. So, let me explain. On numerous occasions I’ve gone as a visitor to another tribal area, or another hapū, which is a smaller version of a tribe. And the ritual of approach is that you go through the gate and you arrive into a space where conversation happens to establish who the people are, and the feminine has a very important part. Nothing happens until the women begin to do their work. And their work is called the karanga, and the karanga just means a call. So I will stand at the gate with my group of people or visitors going into another tribe’s space, and I’ll wait to hear the woman who is standing on the porch and they begin to call. And so their first call is to open the heavens, and I respond to that call and acknowledge. So she calls and I call. And we’re to imagine that our call forms a spiritual bond that kind of weaves around each other, forms a rope, and that call hauls up the visitors onto the marae. The marae is that meeting space. And so we’re doing that really important spiritual work.

We acknowledge the heavens and all of its bounties, we acknowledge the dead and we bring them into that space, we acknowledge Papatūānuku and Ranginui. And so we’re doing this all acknowledging every sort of strand weaving and weaving and weaving. And everybody slowly comes up, slowly comes up, and then we take our places. The people who are the haukāinga, the people who belong to that place on one side, and then the visitors on the other side. And once that work is done, everybody settles and then the men begin to speak. Now the feminists will say “oh how terrible that the men get to speak and the women don’t get to speak!” We’ve already done our business. We did our business. And nobody gets to get into that space until the women have done their business. Now what will have happened in the background is that the aunties will have spoken to those who are speaking and will have given them direction. These are the things that you need to say on our behalf. This is not about you, this is about us. This is about us as a group of people. So very collective, our identity is very, very collective. All the parts need to be sitting together very well. So if at any stage he doesn’t represent us particularly well, the women will stand up and they’ll say “here’s your song” and they’ll sing very loudly and that man will know they have to sit down. So you can kind of see the balance there, right? So always a balance between the masculine and the feminine.

Now if anybody did that differently then there would be… things to say. Do you know what I mean? So you’re very, very safe as a woman. As a Māori woman in a Māori context. Very safe. Colonization has created some disruption in that because their overemphasis on the patriarchy and the disappearance of the feminine was really counter to our whole culture.

AA: I mean, that’s why I wanted you to start with the Māori creation narrative, to be honest, is just the foundational story about a people understanding who they are and why they’re in the world. And I think a creation narrative says a lot about a person’s psyche as a people, collectively and then individually, how do I understand myself. And so to contrast the story you told with the Judeo-Christian narrative, where there’s not even a mother god involved in creation, and Eve sins, we all know the story, right? And so I would think it would have been a terrible disruption. And just hearing you describe that ceremony that you just did too, I felt actually grief that anyone would convert to a different religion that would have denigrated women so much. You know, that seems like a really far fall, to be honest, for a woman to go from something that was so egalitarian to something so patriarchal. It seems kind of tragic, to be honest.

GC: It is. And I think indigenous people everywhere, those who are really caught in the vices of colonization, I mean we understand the irā tāne, or the male essence, to have a particular kind of necessary protective factor about it. You know, an aggressive factor. I’m not saying that women don’t, but we also understand the necessity of the feminine to balance that. And so we always talk about balance. Balance between the masculine and the feminine, balance between the sitting and the standing, balance between the sacred and the everyday and the ordinary. So you always have to get what we call that tau. That balance between all things. If you don’t get the balance then you get problems, right? And European patriarchy created an imbalance, and we’re still suffering from the consequences of that imbalance because the masculine doesn’t know what to do with itself, the feminine doesn’t know what place it has. And so there are a lot of social consequences to that imbalance.

AA: Okay, one topic that you had brought up, Gina, that you wanted to talk about and then I got hooked on, I was so moved by the podcast episode that you sent. And will you pronounce her name for us?

GC: Ngahuia Murphy.

AA: Ngahuia Murphy. And you wanted to talk about the Māori conceptualization of menstruation. Can you tell us about Ngahuia Murphy’s research on menstruation?

GC: So, menstruation of course in the pākehā worldview is something to be hidden. It’s dirty, it’s impure. But in the Māori context… I need to give you a bit of a Māori lesson.

AA: Please.

GC: So the word for menstruation more recently has become ikura, which is from the blood or the redness or the flowing of the red. But when I was growing up, we used to call it our mate, which is death.

AA: Oh!

GC: Yeah, yeah, it’s quite cool. You know, because it’s kind of like a death. In your whare tangata, your womb, a little death happened.

AA: Oh, but it wasn’t seen as something bad, it was just like ah, that’s what happens?

GC: That’s just what it is. And so women used to be able to go off to the equivalent of the red tent, because when their blood was flowing they were very tāpu, which was very restricted. The activities were restricted, but not in a bad way, but that’s why we’re sad. We’re sad during our ikura and our mate because that’s a little death that happened.

AA: So it meant you should take care of yourself and kind of give yourself a little break for a couple days?

GC: Yes. Yeah, you couldn’t cook or do anything when you had your ikura.

AA: Oh, wow.

GC: Yeah, so you just didn’t keep going right? It’s like okay, it’s come so now I’m tāpu, now I’m sacred.

AA: Oh.

GC: So you can’t touch me and I can’t do anything for you. Because I’m tāpu.

AA: Oh, I didn’t realize tāpu meant sacred.

GC: Yeah, so it’s your sacred time. It’s your sacred time of being in your kare-a-roto, being in your feelings. Now, some women collected their menstrual blood because it was good for cursing things.

AA: Haha.

GC: But always, you know, your ikura went back to Papatūānuku. Your menstrual blood went back to Mother Earth. And that’s that connection between the feminine of the Earth and the feminine of the self. So our bodies are like extensions of Papatūānuku and the feminine is to be understood as an extension of the Earth Mother. So we treat our body the way that we would treat the Earth, which should be nicely and kindly.

AA: Beautiful.

GC: Yeah, so Ngahuia Murphy was really about decolonizing our understanding of menstruation which has been great in terms of… Instead of using tampons and pads that just get thrown away, a lot of women have innovated using traditional technologies for capturing menstrual blood and disposing of our blood properly and sustainably rather than just chucking out in the rubbish because it’s very, very sacred.

AA: Wow. I’m just processing how that would feel differently from the time you’re a young teen or a preteen, and saving it because you think it’s sacred. First of all, what that would do to your attitude toward your body and toward the blood and not thinking of it as gross and that something’s coming from you that’s gross, I mean that’s a total mind shift for me. But then also what you just said about sustainability, and I’ve recently just been feeling a little sick to my stomach about all the plastics of tampons and pads and it just goes to the landfill in our culture.

GC: Yeah, and it’s not necessary. I mean, if you use things like Diva cups or if you rinse your panties because we have a thing where if you use menstrual underwear and you soak them in water then you can use that water and you can put it back into the garden.

AA: Yeah, that’s probably great for plants, right?

GC: Yeah

AA: One phrase that struck me from the podcast episode was that she mentioned just the phrase “whose womb waters do you come from”. Is that a common greeting? Or, I didn’t know if that was something that was asked when you meet someone, like who’s your family, who are your people? She said “whose womb waters do you come from?”

GC: Yes, I like the way that she said that, and that’s something I hadn’t thought about before. When we ask where are you from, and that’s always the first question, I would never ask somebody their name.

AA: Oh.

GC: So if I met them in a Māori context, the first thing I would say is “from whose ancestor?” or “where do you descend from?” And then I might ask, kind of sheepishly, what’s your family name, and then maybe their name. That’s less important than where somebody is from. But the word wai is used for water but it’s also used for who. So if I say “ko wai tou ingoa?” which translated into English is “what’s your name?” but the word wai is also used as water so “whose water is your name from?”

AA: Oh, so that’s what she meant by womb. It’s “whose water are you from,” you would imagine that’s like the amniotic fluid.

GC: Yeah, yeah, and the water is always very important. So in a traditional context when I introduce myself, I’ll basically say that my ancestors’ waka, or their canoe, landed on the shore. And then the waters came from that mountain and they came down to feed my ancestral village. So you take the word for wai, which is used in the introduction of self, but it also means water. If you look at the word hapū, which is a village, a village community, a hapū, it also means pregnant.

AA: Wow.

GC: If you look at the word whenua is land, but it’s also placenta. The word pito is your umbilicus and it’s also the word for the end of something in a building. So children’s pito, the umbilicus, is buried at the end of a house of a carved meeting ancestral house. And then the whenua, the placenta, is buried back into ancestral land. So we say the whenua to the whenua. The pito to the pito. So you’ve got all of this language which binds us into a larger schema. Language that we would use on an everyday level but also language on a higher spiritual level. Does that make sense?

AA: It does. It’s just so lovely. It’s so beautiful to bind people to their ancestors and to their land. And I’m just thinking, like you said about the blood, I’m just thinking about my own life and my own self as a little teenager all the way ‘til now I’ve actually done some work in my own life reframing menstruation and reframing just the female body, my own body, and recognizing how much internalized misogyny I have accumulated throughout my lifetime. And doing some different self-talk for myself. Like I do notice when I get my period that I’m completely disgusted and grossed out, and maybe a couple years ago I noticed that that’s what my brain did and then I stopped myself and I said thank you to my body instead. And I actually cried a lot when I realized that every month for the past however many decades that I’ve been going through this, I didn’t even notice that I have such negative self-talk. And I just thanked my womb for giving me my four children and acknowledged that it was doing what it was supposed to do and that that whole process was necessary for me to be able to have children. And that even for women who don’t have children that this is not a gross thing, it’s just a natural part of being human and being female. And I’m just considering what that would have been like to have been raised in a culture where that was just native to me, that that was just the default way of looking at a girl and a woman instead of this like “ew, don’t talk about it” and seeing ourselves so negatively. It makes me really sad, and really happy that it does exist in a better way in other places.

GC: It’s infinitely healthier.

AA: Yep.

GC: I mean, how can you hate something that’s supposed to happen, right?

AA: Right. And that’s a part of you.

GC: How can you be disgusted?

AA: Yeah, it’s so sad.

GC: And it’s always a beautiful indication of the activity of your whare tangata, your uterus. And so your mate, your period, your ikura, is an indication of activity in the whare tangata which is beautiful! Well, that’s people. Just beautiful. That’s not to say that your job is just to have babies.

AA: Right, right.

GC: But something creative is happening and you are like Papatūānuku. In the womb of Papatūānuku– you know, we say that when there’s an earthquake, Papatūānuku still has this baby in her womb called Rūaumoko, who is getting kind of agitated and moving around. But Papatūānuku the land is always producing, the land is the ultimate kōpū, the ultimate whare tangata, the ultimate womb. And so in that stage, and that’s why we take our ikura, our toto, our blood, and we take it back to Papatūānuku. Because that’s our connection. Because that’s that feminine activity that affirms our divinity.

AA: And I love, not just for people who begin menstruating but for boys, I mean, if you have those words that like you said, the land is the same word as placenta. And to just acknowledge that the land feeds us and the placenta fed you when you were in your mom’s belly, and just to normalize all of that. It’s just natural. That’s the way humans come into the world, and so to have it represented in the language is really powerful for all people regardless of gender to just not kind of hide it and stigmatize it.

GC: Yeah, and Māori men who are very secure in their cultural identity don’t need that explained. They just exude respect for the feminine.

AA: You said you have six sons, right? You live in a house of men.

GC: Yup.

AA: Haha. Can I ask you, did you talk to your boys about what menstruation is?

GC: Yeah, yeah.

AA: Yeah okay, that’s so great.

GC: Yeah, so their sexuality education also involved watching birth on YouTube. Lots of births.

AA: Fabulous! That you just showed to them so they would be educated.

GC: I’m like, “Come on, gather around boys, time to watch a baby being born, ko whanau mai.”

AA: Wow.

GC: Just so they understand the whole process.

gather around boys, time to watch a baby being born, ko whanau mai

AA: Good for you. That’s so awesome. Okay, I know we talked about this a little bit but I’d love to dig into it a little bit more. I’m curious how Māori traditions and ceremonies survived colonization. And specifically what were the receptacles that kept them safe so that you have the traditional stories survived and the language survived and didn’t go extinct? So, if you can talk about those receptacles that kept them safe during colonization, and then talk about the renaissance that you referred to earlier that I guess started during your lifetime. Can you talk about that a bit?

GC: Yeah, you know, Māori are very gritty, very hearty. Language is the most important thing because they are the receptacles. And I explain to people if I’m teaching the language, it’s not just a word-for-word transfer. It’s not just knowing vocabulary. It’s operating within a realm that is offered by Māori thinking. Your thinking is structured in a Māori way. Very, very difficult. If I’ve been in a context in which we’re only speaking Māori, I don’t want to speak English, honestly. I don’t really want to speak English. I wish I lived in a world in which I only ever spoke Māori, because that’s much more intuitive to me. It’s beautiful. It’s constantly compelling. And it’s who I am at my very core. And so the language holds everything.

And my husband and I were coming back from Southland, where my oldest sister, my tuakana, that’s the oldest sister in Māori, was receiving a moko kauae. This is just last weekend. And a moko kauae is a tattooing of the chin area. It’s a Māori aesthetic and it’s an interesting conversation that we have, you know, all of our sisters we’re Ruwhius. That’s our family name, Ruwhiu. The Ruwhiu sisters married pākehā men. And my older sister and I have raised with our pākehā husbands that we would like to get a moko kauae at some stage because that’s just a marking that’s part of our life transition. And it’s been a really interesting conversation about aesthetics, because the Māori men in my life are like “when are you getting your moko kauae?” And I’m like, “ah you know, Nathan isn’t that keen” and they’re like “oh, kaua ki taua tangata pākehā.” Like “don’t worry about that pākehā man, it’ll make you beautiful.” But when Nathan’s concerned it doesn’t make you beautiful. So we’re talking about different aesthetics for a Māori woman to have a moko kauae that’s an adornment, it’s a cosmetic as well as an assertion of her mana wahine. And to have a bigger body is also valuable because they’re sturdy, haha, and they won’t get cold quite as quickly. So there’s all of these aesthetic things that we kind of wrangle with in our family.

But back to your question, I was thinking about the language and as we were driving north back to Christchurch where we live, I was thinking in Māori. And I turned to Nathan and I thought, because he speaks a little Māori but not a lot. And what I was thinking in Māori was “he aha te roa?”, which is “how long is this going to take?” or “how much longer have we got to go?” And I turned to him and I said, “what’s the long? What’s the long?”

AA: Hahaha. That’s funny. You’re translating back to English. I love it, that’s cute. I wanted to ask, at what stage of life do you get the chin tattoo, the marking?

GC: Any stage.

AA: Oh, any stage. Just when you feel like you want to.

GC: Yeah, I mean there’s a lot of debate about that happening in our community, in the Māori community. It used to be that young girls would get it. This would be kind of a pubescent thing because it would enhance her looks so that she would be more attractive to possible suitors. The last person in our family to have it was my great-great-grandmother, she was the last one to be marked on the chin. So it’s been a while, you know, so my sister bringing that back to our family has been lovely. And a lot of women are, like it would be unusual for you to come to this country and not see women marked.

AA: It’s taken a break since your great-great-grandmother had it, and so is that fact that more women are doing it now, does that indicate a resurgence of traditions like that?

GC: Yeah, I think it has to do, because there was a lot of racism about facial markings. And so New Zealand as a bicultural nation has gone through its own journey. And we’re kind of at a stage where we have a whole education system in Māori language, we have television stations, radio stations. Anybody who’s anybody needs to be bicultural and bilingual, it’s just kind of a nationwide thing. So that’s offered space for Māori women to assert themselves, that identity. But your question was about when, so that was usually a pubescent thing. And it’s really up to women to decide when it’s the right time.

AA: Okay yeah, so you said the receptacle that kept Māori traditions safe and alive even though there was cultural oppression and you said even your dad was told he couldn’t speak the language. But it was kept alive and I’m sure in certain families, so I guess my remaining question was who was it that started this renaissance of culture and fighting back against those oppressive rules?

GC: There’s always been a fight. Always. So Māori resistance has never not been a thing. It’s gone through different phases. There were a lot of land confiscations in the nineteenth century, there was resistance there. There was resistance to the kind of ongoing court system that alienated Māori from their culture and their language. So look, the story of Māori in a colonized territory is a story of resistance and resilience. And I go back to what I said before, when it looked like in the 1970s that the language was on the way out and that something needed to be done, many people recognized this. You know, we’re a collective people. So we go from tribe to tribe as groups and we have that conversation. There’s no one savior person. That’s very much a different outlook. We don’t have a president of all the Māoris, you know. We’ve got a king and we pay respect to him, but he’s not over all the Māori because you couldn’t do that because there is no one group of Māori. There are a number of different tribes of Māori who share collective concerns, but sit in their own identity of their own tribe and their own character of their tribe, their own law, and even to a certain degree, their own language. Dialectically, we can be quite different. But we have the same base language. And I would say that it was really women who got together and said if we don’t do something about this, we’re gonna lose this language. And so in the early 1980s they put together what they call Kōhanga Reo which are language nests, and these are early childhood centers. They did that voluntarily, the government didn’t pay them. But they would go around in their communities and they would knock on doors and say, “we can see that you’re hapū, you’re pregnant, so you need to bring your baby to us.” So there was a real sense of “oh, okay!” You know, you have to deal with some of the resistance to the colonial thinking of a lot of our people at that time. And so a group of children grow up immersed in the Māori language supported by the grandmothers and the aunties.

And then there was the question of “what do we do now?” They’ve got an early childhood education, so now we need to have schools. And so they started schools, they’re called kura kaupapa. And then from the schools they were like oh okay, so what do we do with our kids once they reach 12? Let’s make high schools for them. And by this stage the government was getting on board. There would be petitions to the government to formalize Māori and to make it an official language of New Zealand. That was passed in ‘92, I believe. And then schools became kind of entrenched, and then the success of those Māori schools was phenomenal. So if you secure cultural identity with people then they can fly. And that’s what the research has discovered. That these schools for our young, where they’re immersed in the culture and the language, they’re coming out very secure with fewer of those deleterious kinds of antisocial activity going on in their life. They go on to university, they get PhDs, they become doctors, and they perform at a level that’s equivalent to our independent schools. So there’s that. And so that language holds a lot of that wisdom. And that was really a transmission of grandparent to child because there was a whole generation that was lost in there, who were the first urbanized ones who were told “you don’t speak the language” and were made to feel embarrassed about being Māori.

AA: Wow.

GC: What we say is tikanga, which is ‘culture is always in motion, but the principles that hold it there are firm.’ The principles of hospitality, of ancestry, ancestry is really important to us and where you come from, whapapa. The principle of the taiao, the environment. What’s our relationship with the environment, because there’s this beautiful saying which says “ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au.” It comes from a certain tribal district, but it’s saying “I am the river and the river is me” and that goes through all of our thinking. I am the land, the land is me. And if you understand that you are the land, the land is you, you’re not some corporeal object that’s eventually going to go off to heaven and be celestialized and live in another kingdom so you can just, you know, you can dirty up the Earth as much as you like. Which is really, really terrible. One of the terrible aspects of Christianity is to kind of displace responsibility for the Earth to something else, to kind of another realm. But Māori are very grounded in that. We’re here, we’re with the Earth now, we need the Earth, so let’s take care of her. Let’s take care of the sky because there’s no distinction between what we are and what that is.

AA: Beautiful. Okay, I have two more questions for you. The first one is that New Zealand was famously the first country in the world to grant women the right to vote in 1893. Is that something you grew up knowing and were proud of? And then my second question about that was whether Māori and women of European descent, white women, did they work together for the right to vote? Or, I know that in America and in Europe actually it was a very fraught process of white women kind of throwing women of color under the bus and not being able to work, not including them in the process of suffrage. And I wondered if it went differently in New Zealand?

GC: We had a suffrage movement for sure. And our country’s most famous suffragist was a woman called Kate Sheppard. She appears on one of our notes, I think. And she was English and she came to New Zealand in about 1868. Yeah, so she organized women’s suffrage and so she was working really hard in the urban areas. Now, Māori women got the vote as well, so you have this suffragist movement being a really important part of our history. But I don’t know, I mean, I’ve always known it. I mean, I grew up in the 1970s and ‘80s and my mother counted herself as a feminist. And the big question was about women’s liberation. And New Zealand is very progressive and I think it comes back to the fact that there were not very many white women here. And so when they did arrive, it’s like “oh we’re so grateful that you’re here, we’ll just give you your rights.” Haha!

AA: Oh that’s funny! That’s interesting. So it was mostly men for a long time? European colonizers came to the island and didn’t bring wives with them for a while. Is that how it worked?

GC: Yeah, and you’ve got to think about New Zealand in terms of being, I mean, it looks like a small place but we’ve always had a small-ish population. And here’s the issue with living in rural areas where both the masculine and the feminine are really important, even in pākehā contexts. So you have men often that came out first to cut down forests and ruin our landscapes but, you know, there’s another story. Begin the process of farming and then bringing their wives over and they played a balanced role. So I think males and females in New Zealand, by nature of the landscape, were forced into cooperation with each other.

But also I think the pull of Christianity hasn’t been quite as much. Like right from the outset, if we had a state religion it would be the Church of England because we’re still a constitutional monarchy and currently we have a king. But it’s been quite secular. So yeah, Christianity’s been important but quite secular. And so that has kind of greased the wheels of LGBT rights, also the wheels of women’s rights. If you look at our current parliament we’re at 50/50 in terms of females and males, I think maybe for the Labour Party, the current government. We’ve got like this kind of outsized proportion of LGBT members of parliament representing us. And I’m not saying that it’s all idyllic, because we do have that whole sector of kind of pale, male, and stale and Christian, who get mouthy about things. But generally you wouldn’t last here. It would be very difficult to last here if you weren’t progressive in your politics.

males and females in New Zealand, by nature of the landscape, were forced into cooperation with each other

AA: Yeah, well that leads to the last question which was about Jacinda Ardern. You know this, I’m sure, but I feel like the whole world, at least the people I know in my world, just look at New Zealand as this beacon of hope. And we look at Jacinda Ardern as this incredibly inspiring figure. Can you talk about her a bit?

GC: Yes, phenomenal woman. I have such huge admiration for her. As you know, she grew up LDS in a very strong LDS family. Her uncle was the principal of Church College, which is the school’s college. She grew up in a place called Morrinsville and participated in the church right up until she was a young woman. She went to Wellington to do her degree in politics and there was kind of exposed to the progressive politics that had really had her heart. She was very much a Democratic Socialist, very much left-leaning in her formative years. And she was in a house living with LGBT people. And when she realized the reality of that, she knew at that point that she couldn’t reconcile the LGBT issue with her own growing self, her own sort of spiritual and personal development. She also says that tithing was a problem because she’s got a heart for the poor and she realized what a burden tithing is on those who are poor.

AA: And we should say here that the LDS Church requires you to pay 10% of your income to the Church, for those listeners who don’t know that. It is a tremendous thing to ask of people who are struggling.

GC: It’s huge. And she, like me, grew up in New Zealand where the church is largely brown and largely Pacifica Māori. And so, it’s poor. And for Pacifica people who desperately want to stay, who desperately want to be part of the community, are working a couple of jobs, paying ten percent of the income, and that just doesn’t make sense in terms of social justice. So for Jacinda Ardern, she’s a social justice warrior. And so growing up in the church I think has made her reasonably competent in the Māori world and in the Pacifica world as well. I think growing up LDS in New Zealand in particular meant that she was exposed to a lot of cultural trajectories that normal people wouldn’t be exposed to. That’s why she’s so competent with diversity.

AA: Yeah, well also the way she handled the shooting that you had a few years ago just with so much compassion and grace and empathy, I just was so moved by that. One last question about her, when she resigned recently she talked about her mental health and her personal life and bringing that into play and not just being in politics for ambitious reasons. I thought that she was being a tremendous role model there too. Is that the feeling in New Zealand as well?

GC: Yeah, and I will say she really came under the pump over Covid. So you would know that she’d had a series of things. I don’t know of a more tragic period in New Zealand’s history where one prime minister had to deal with it. We had the volcanic explosion on White Island where I think nineteen people were killed. And they were mostly tourists so then she had to deal with that. And she had to deal with the shooting, in which 51 people died just around the corner from where I am now. Just down the road. And then she had Covid. And I think that there is a very noisy and horrid sector of our community which is very patriarchal, very white, very fascist, and wholly uninformed. And has not a social justice bone in their body. And they sent her death threats and, I mean, they really made her life hell. She was very, very resilient about that. But I think she was tired. I could tell it. Like before Christmas I’d said to Nathan I heard her at a press conference and I thought “well, she’s tired, she’s sick of this.” And then she came back after Christmas and said “I’m done!”

AA: Well yeah, she’ll go down in history as such a role model for people and it was wonderful to watch even from afar. And it’s just one more reason to be jealous of people who live in New Zealand, especially in the last little while living in America. But anyway, are there any final thoughts that you’d like to share, Gina?

GC: I would just like to say, and I know kind of the struggles of the feminine and I’ve been involved and coming backwards and forwards to America so I’m somewhat familiar with the discourse. I’m not a native. But just from a Māori woman to an American woman, just to say to never undermine or degrade the feminine in you. That is a gift from the gods and the goddesses. And to be mindful of that. That patriarchy is a sin for any cultural system. And not to be apprehended by that but to assert, be like the aunties. Like what’s at risk here, organize collectively, and assert your right to be a woman. Assert your right to be teaching your particular relationship with the whenua, with the land, and Papatūānuku. This world has gone very topsy-turvy when that balance is out so we need some strong women to reassert that balance.

AA: Thank you so much, Gina Colvin. I so appreciate all of your wisdom and so appreciate you talking with me today. Thanks so much.

GC: Kia ora, he mihi māhana ki a koe me te hunga e whakarongoana. Kia ora, Amy.

culture is always in motion,

but the principles that hold it there are firm.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!