“my value is more than being a mother and nurturer”

In recent centuries our world has only deepened its relationship with the sciences and technology – we celebrate life-saving medical advances, continue to develop faster and faster methods of computing, and many of us were recently staring into our screens with wonder, admiring stunning images from the James Webb Telescope. We depend upon Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (or STEM fields) to bring ease, entertainment, and wonder to our lives, so it’s no surprise that many of the fastest-growing and highest-paying careers are within these fields of study. And yet, if we apply a lens of gender to STEM fields, what we find is that alarmingly only 28% of the STEM workforce is made up of women. Why’s this? Well, studies have shown a number of factors discouraging girls and women from exploring STEM fields, including pervasive gender stereotypes about ‘male’ and ‘female’ jobs, an absence of role models, hurtful and inaccurate beliefs that women are inferior at mathematics, and finally there are the male-dominated cultures within these fields where women historically haven’t been allowed. Taken all together, it’s no wonder that so many girls find themselves pushed away from studying math, science, or engineering – our patriarchal institutions have done everything to dissuade them short of posting a ‘no girls allowed’ sign on the door.

Okay, you might think then “Well, if not the left brain, then the right. If women are still discouraged and discriminated against in STEM fields, at least we’ll thrive in creative fields and the arts.” I’m guessing you know where this is going….if you were to go to Google right now and type in ‘most famous portraits’ you’ll find that among the top 10 results, 8 of the images depict women and yet all 10 were painted by men. In fact, out of Google’s top 50 portraits there are only 2 works by female artists included – and yet nearly every single one of these paintings uses the female body as its subject. It seems that historically, and still too often to this day, women in the arts are told to look pretty, sit still, and be silent while the male artists create their work.

On today’s episode we’re going to be exploring both sides of this double-edged sword, hearing from two special guests – computer engineer JoCee Holladay Porter & artist Shannon Christie – as they help us unpack the impacts of patriarchy on women in the arts and sciences.

Our Guests

Shannon Christie

Shannon Christie (she/her) is a social worker, artist and writer, and the founder of Ragtag Magazine, a web publication focused on creativity and community in the Pacific Northwest. When she has any amount of free time, she loves trying new Thai restaurants, doting on her houseplants, and collecting shiny rocks.

.

JoCee Porter (she/her) is a computer engineer and a wannabe science communicator. She runs a book club highlighting female authors in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM).

JoCee Holladay Porter

PART ONE.

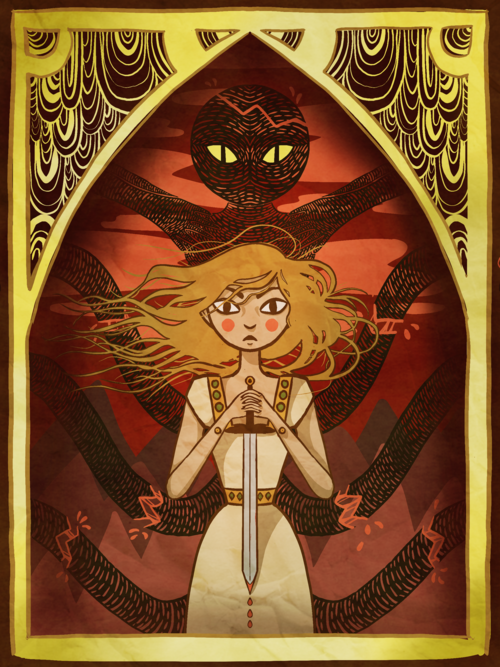

Shannon Christie

For those of us who have lived experience as feminine, in all its beautiful and brilliant and terrifying forms, many if not all of us have developed a rough and perhaps violent escape in our minds. A mechanism for those moments when—uniquely trapped by the rampant societal belief that all we are boils down to emotional creatures to tame—our anger boils over and goes to have its way. For me, this escape has involved taking a bat to some mythical and conveniently contained establishment called “The Establishment,” and releasing a fury that swallows everyone who’s ever underestimated my intelligence and undersold my worth. I’d let shrapnel rain like glitter and stand unflinching in it.

Then I awake from these righteously angry daydreams, swallow glass, and make art with the aftermath.

See, in a creative space I am the only driver. When pencil or brush is on paper, when hands are on clay or sewing needles, the world is quiet and limitless. No matter what goes on with the rest of the planet, no one can take my mind; that is a comfort relived again and again when I sit down to create.

My experiences, both personal and professional, deeply inform the work I make. Psychology is deeply woven with creativity; what resonates with us? What makes us feel things deeply with just a look or a read? What is the right formula of visual and written elements that can accurately convey this anger I feel- how can I make others get as close as possible to what I, and many other women, experience, in a container that allows for safe exploration of these thoughts and emotions?

I often try to pull this off through reclamation of symbolism that embraces femininity, while placing it in an empowering light. I want to take the things that have been used as fodder to cause harm, and weaponize it back against the people who used it to cause said harm. I’m fascinated by witchcraft and all things deemed magical, for example, especially being a descendant of women who were accused and hanged for it in centuries past. A delve into the history of witchcraft, a topic that could take hours all on its own, shows how independent women were vilified, how easy it was for gossip to threaten lives, and how the experience of womanhood was pathologized into demonic possession and hysteria. If you want to know more about witchcraft and womanhood, I highly recommend the book American Witches by Susan Fair.

While I exist, gratefully, in my safe haven when I create, makers in general can unanimously relate to the intimidation factor that comes with finishing a piece, and sending it out to the world. Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic was the first piece of literature to introduce the concept to me that, when your book is published, your painting is unveiled, or your music is released, your work isn’t just yours anymore. It’s there for people to cherish forever or tear apart bit by bit.

For that, and for many other reasons, it’s a brave thing to create. It’s a labor of love with hearts on rolled-up sleeves. For me, it’s taking all the sh*tstorms that planet earth throws at me and transmuting said sh*tstorms into visual art that I want people to connect with. The purpose of my work is to drag all my shadowy parts into the light and let them become a force for good; people need to see that there are others who are saddled with similar battles, including and especially feminine folks who search for solidarity. I want people to find themselves amongst my colors and linework, because I want people to feel less alone. This mission informs every creative venture I move forward with.

In the face of my purpose for creating, I must discuss some melancholy statistics about how works by different demographics are received: worldwide, works created by women are priced lower than men (1). Many museums are featuring more depictions of naked women than they are featuring work from actual women artists (2). In fact, women artists are barely getting featured at all; in 2018 a survey of 18 museums showed that 87% of featured works were by men- 85% of which were white (6). Lastly, while creative fields do not experience the “motherhood penalty,” in which women lose or stagnate with their income, men are shown to get an income bump when they become fathers. Same thing happens when they get married, too, which only deepens an already-prominent wage gap, notably in galleries and auctions (9).

Art is inherently about expressions of emotion, opinions, things that can’t always be spoken but are felt so deeply regardless. But what all of this shows is the sad truth that expressions of emotion are hailed as heroism for men, yet dime-a-dozened for everyone else.

A small yet poignantly particular time that comes to mind for me personally is an Instagram post a male-identifying artist connection made to their feed stating that they haven’t been happy lately and could use support. The outpouring of admiration that spilled from people’s fingers was endless. “I love you, you’re so brave for connecting to your feelings, I see myself in this, you’re inspirational, if you need help please reach out,” et cetera on and on.

Years back I’d done the same thing on my own art page; I’d bore no details about what I was going through, just that I wasn’t happy. I was met with a private message saying “are you sure you want to post that? You’ll make people worried.” I took the post down.

It’s worth mentioning that there is an unfair expectation placed on men to be cold and steely; to bottle their feelings up, “take it like a man.” I don’t want to have this issue I’m discussing be blanketed as telling anyone to shut themselves off, or that there is a lack of cognizance around the unfair expectation that masculine people should be devoid of vulnerability.

However, moments like those in my life rearranged what it meant to be to express creativity, specifically, in this body. I became painfully aware of what has historically been “allowed” for others in a different type of body, and what wasn’t for bodies like me. It should go without saying that women and nonbinary folks feel all the same things men do; of course all humans feel joy and sadness, anger and trauma, elation and pleasure and all the other beautiful and terrible things that come with this experience. So why is art by feminine people garden variety, and art by masculine people the diamond in the rough?

Worse yet, some of the most famous works of art by men depict women as their subject matter and once again are championed for it, while the souls in the bodies being featured are ignored. Think about Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, Manet’s Olympia, Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Courbet’s The Origin of the World, on and on. An exhibit curated by Alisa McCusker at the Museum of Art and Archaeology at the University of Missouri dragged this double-standard into the light in 2019. It was titled Objectified: The Female Form and the Male Gaze, and featured works by men in which female nudity and assault were center stage. A quote from the summary of this exhibition asks: “How do we reconcile the heroic personae of artists with their mistreatment and abuse of women in their lives, whether models, muses, lovers, or wives?” (3)

What a thing to ponder, and what a message to send. Use our bodies as your muse, channel your feelings through our skin and bones, say you’re putting us on a pedestal while you lock us in towers instead. When we’re that high up, you can’t hear us no matter how loud we scream. Be pretty, never speak. You’re better off naked than talking; yet on top of all of this we societally demonize real, actual women made of skin and muscle and bone who are intimate, who are sex workers, who are survivors and mothers and partners and pretty much anyone in between and beyond.

And this demonization isn’t limited to the visual arts. Let’s talk about Taylor Swift for example. In an ongoing quest to gain the rights to her own music, she is re-recording her entire catalog prior to her signing with Universal Music Group in 2018- a label that actually allows her to own her masters, unlike her prior label Big Machine. Her re-release of her fourth album Red has been at the forefront of musical news for weeks now. In each re-release, she includes several tracks she’s dubbed as “From The Vault” songs- tunes that she originally wanted to have on the record but were cut for one reason or another. It’s a delve into the past, and through it the Red of 2021 is telling a far different story than the Red of 2012, one that paints a more realistic and emotional picture of a woman in her twenties than the polished image of before. She sings about feeling depressed, drinking her feelings, having sex, and giving us a “f*ck the patriarchy” in the process.

…in 2018 a survey of 18 museums showed that 87% of featured works were by men- 85% of which were white

I can’t help but wonder why the songs that didn’t make the cut are songs that make her more human than ever. I can’t help but think about a 22-year-old woman bringing her work to Big Machine, a label founded and chaired by men, and being tsk-tsked out of her vulnerability in favor of a purer, more restrained visage to send to the world. Yet Rascal Flatts, a band composed of men, released Changed that same year, under Big Machine, an album that croons about feeling depressed, drinking their feelings, and having sex. (4) Or how about The Cadillac Three, another band of men, and their LP of the same name, also released under Big Machine and also released the same year, were able to sing about, once again, feeling depressed, drinking their feelings, and having sex (5).

This double-standard story has repeated itself throughout history, where women’s creative expression is regarded as lower-caliber or held to standards so high that it becomes impossible to maintain any semblance of a good name. In either case, it results in a stifling, like ropes around our ankles on a racetrack and an expectation to hop, while we watch men run unhindered across the finish line; then they turn and wonder why we can’t keep up.

In another case of double standards and stifled art, we can look at the film industry. Actress Tippi Hedren was relentlessly harassed verbally, emotionally, and sexually, by the famous filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock. In her autobiography she details multiple instances in which he advanced on her without consent, controlled her time, and pushed her to the brink mentally. She was psychologically traumatized after having live birds tied to her body that pecked at her during the filming of The Birds, when she’d been promised they’d be mechanical. During the filming of Marnie, his behavior toward her finally pushed her over the edge and she told him she would no longer make films with him. As a result, he destroyed her ability to find work for the next two years (7). Recently, Hedren’s granddaughter Dakota Johnson went as far as to say Hitchcock destroyed Tippi’s career entirely over her finally implementing boundaries (8).

Of course, Hitchcock got to continue making more films and remains acclaimed to this day. I had to write essays about Psycho and Vertigo in college and heard nothing of his behavior until I did my own research.

Meanwhile, Hedren got blocked from making more films. One must wonder what work Tippi could have made in those lost years. She would’ve made for a better f*cking essay, that’s for sure.

And in our wonder, we must ask: What kind of message do we send when even the biggest women in the arts aren’t celebrated for their true expression? What are women to do when advocating for their worthiness to be treated with respect in creative fields is met with a blackball? When we’re invalidated, blocked, cheapened, or given so many walls that the thing that was supposed to set us free the most has suddenly been caged?

And what a disservice the world does to women by making this entire issue an automatic wound to each of our works. None of us want to be saddled with this, and yet we’re saddled with it. We could sing and paint and sculpt about our subjective experiences, connecting deeply on the basis of the things we all uniquely love and hate and experience; what a shame it is that a core connector has to be the infliction of sexism. No feminine person wants it, but all of us have it no matter where we are in our creative journeys.

I think of all the women and gender non-conforming folks throughout history who have suffered this wound. Whose work has been discounted, whose emotional outpourings of poetry and performance have been dismissed as fluff, who have had to claw forward as they watched men walk. I’d spend an eternity naming all our names.

I celebrate that my male artist friend felt safe enough to express vulnerability. We need more of that. It’s not my goal to say everyone should paint still life flowers and gray skyscrapers only. It’s my goal instead to say that everyone in artistic spheres should be uplifted, that emotion conveyed by all bodies is sacred. Creative expression on the same playing field, without the violent objectification of women to further men’s quest for their own authenticity, sounds like a beautiful dream.

And until that dream becomes reality, we must do something with our rage.

In my own reflections on rage, there hasn’t been a single point in my life where it hasn’t come from a place of hurt. Anger is the armor of hurt. My baseball bat fantasy generated from gender inequity is that armor, the chosen weapon swinging about a defense from the hurt of invalidation, prejudice, and unfairness. When I developed a relationship with my anger, peeling back the layers and really seeing their hurt, that is when the work could begin. And in seeing the hurt, I realized what a fierce place of love it was melded with. I have a deep love for my existence, and love for the brilliant people who exist in bodies like mine, who align with my identity, who embody the powerful experience of femininity despite any obstacles thrown their way.

It is that love that led me to create a new place where these voices would have a definitive place at the table, no matter what, as the founder and Executive Director of Ragtag Magazine. We are over 80% women-led and 100% LGBTQIA+-led, with over 60% of our team overall identifying as LGBTQIA+ as well. We’ve featured women and gender non-conforming artists, activists, musicians, environmental experts and more in the year we’ve been in business.

What kind of message do we send when even the biggest women in the arts aren’t celebrated for their true expression?

Our lived experience informs everything we do, since day one. We had hours and hours of roundtable discussions on how to make Ragtag inclusive before our launch, exploring how we could make our organization the best possible place it can be, without reinforcement of patriarchal norms. In this, we developed an internal manifesto that places emphasis on elevating voices from all walks of life, equitably; that adapts to community need; that commits to transparency and readily admits when we are wrong or could have done better. We adopt humility in our practices and hold each other accountable; we don’t let pride or the need to be “right” get in the way of learning how to be better about equitability, because there’s always room to become better. We only bring people onto this project if they’re on board with that.

At the same time, we acknowledge that we live in a system that has built its bricks for hundreds of years, and for that reason we can work to minimize harm but will not be martyrizing ourselves as the people that will eliminate it.

What I want to strongly emphasize to listeners is that you are capable of enacting change in small ways every single day. Your small actions have the capability of rippling out to the people around you, who ripple out themselves, then to others, on and on. No matter your identity, you can vote with your dollar and support with your voice. Support living female and gender non-conforming creators- the more local the better. Place an even greater emphasis on supporting your friends and family- you will change their lives if you do. If you aren’t in a place to give financially, then spread the word about them. Advocate for your painter friend at cafes and galleries looking for new work to hang. Share your musician friend’s Tiktok to your pages. Show up to poetry open mics and cheer as loud as you possibly can for the people you love. Be a community member for us.

For any women and gender non-confirming artists out there, please be gentle with yourself. You are fighting setbacks set in place for hundreds of years and the reality is that it won’t change tomorrow. When it comes to this issue, you’re not doing anything to deserve prejudice. That is not your fault. It is never your fault. Dismantling misogyny is a marathon, not a sprint. Check in on yourself and your peers regularly, and seek out and accept support wherever you can.

I’d like to think that the version of me that lives in my mind clutching her baseball bat like it’s the last thing she’ll ever own will one day permanently lay it down, cover it with earth and let the wood that once made a weapon compost into the flowers that grow for her children and her children’s children and her children’s children’s children. Perhaps the need for it will never die. So while we inevitably exist together in this unknown, I will hold her hands in mine, and I will validate her fury. I will ask her to trade the bat for a hammer so we can build a better future together.

References

(1) https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-work-female-artists-valued-work-male-artists

(2) https://www.themalegraze.com/gg/museumcount

(3) https://maa.missouri.edu/exhibit/objectified-female-form-and-male-gaze

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Changed_(album)

(5) https://www.discogs.com/master/1099946-The-Cadillac-Three-The-Cadillac-Three

(6) https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0212852

(7) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tippi_Hedren

(8) https://www.buzzfeed.com/larryfitzmaurice/dakota-johnson-tippi-hedren

PART TWO.

JoCee Holladay Porter

My name is JoCee Porter, and I’m a computer engineer. I love anything STEM—Science Technology, Engineering, or Math! Even with my love for engineering though, the patriarchal systems that we live in have been a real barrier for me getting my engineering degree. Despite always being the “nerdy” girl, I was never encouraged to go to college (other than as a backup plan if my husband died). It was assumed I would grow up and get married and have children. That I didn’t want a career in engineering What did I need college for? And still today, as a professional engineer, the patriarchy and incorrect gender assumptions continue to impact my life. So, I’m going to share with you all my story of what I had to overcome to become an engineer, and the challenges I continue to face.

I grew up in Utah. Utah is unique in its focus on family and the culture to have many children. Mothers stay at home and raise children, fathers go to work and provide for these children, and everyone is “happy”. As a result, I didn’t know a single women engineer growing up. Not one.

The Utah culture is largely driven by the Latter Day Saints faith (LDS), otherwise known as “Mormons”, who make up 50% of the population. The LDS church is an unapologetic patriarchy with a focus on families and distinct gender roles. These gender roles are spelled out in black and white in a Proclamation to the World that the 15 prophets wrote, quote: “Mothers are primarily responsible for the nurture of their children“. While, on the other hand, quote: “By divine design, fathers are to preside over their families in love and righteousness and are responsible to provide the necessities of life and protection for their families“. You heard that right: by divine design, gender roles are established. Men provide and preside, women nurture. These prophets were inspired by God when creating these gender roles, and when something comes from God, you can’t fight it. So if you believe in the church and in prophets (like I did, wholeheartedly), you believe in these gender roles.

This letter laying out the gender roles for members of my faith is part of a system called Complementarianism. Complementarianism is the thought process that men and women have distinct roles that, though different, are complementary (sounds familiar 🤔)…but I want to point out that women were left out in deciding these roles for the LDS church. And that even though the roles are supposedly fair and complementary—the final say on household decisions ultimately goes to the male as the leader of the household. I also want to point out that the prophets who conceived, wrote, and signed this proclamation happened to also be 15 wealthy white men. Shocking.

To give an example of how seriously this (American-based) religion takes these “divine gender roles”, let’s take one look at the employment policies for LDS religious teachers (also known as seminary or institute teachers). For decades, every female teacher was let go when she had a child, “allowing” her to focus on raising that child. Divorced women were also let go. Remarried women couldn’t even apply to become an LDS religious teacher at all. Unsurprisingly, men have never been under such restrictions.

These rules have since been revoked, but were in effect my entire adolescence. In my 6 years of religious studies, I never had a female religion teacher.

The focus on family and the distinction of gender roles is engrained in the LDS culture and as a result, almost every woman I knew was a stay-at-home mother. Mine included. And if women did work, they weren’t engineers or scientists. They were teachers (not religious ones), secretaries, or nurses—jobs that have flexible hours for raising children.

Growing up, this lens of “fathers provide while women nurture” was always shaping the way I could view myself. My worth was in having children and being a wife. It was what I WANTED. I mean, I love children! I also didn’t know any better. I didn’t know all the possibilities for my future. I didn’t know you could have a career AND be a mother. But I did know one thing, I have always loved math and science. I mean, I really love math and science. I know in some religious families, fathers prevent their daughters from exploring these interests, but I was lucky enough not to be born into such a family.

My interest in math and science has always been encouraged by my parents. Despite the ambient misogyny around us, both of my parents were great at supporting my ambitions and teaching me to think independently. They also encouraged my mathematical and scientific interests. For example, when I got into an argument with my 5th-grade science teacher about how the direction that water swirls when emptying a container does NOT change when you cross the equator (the body of water isn’t large enough to be affected by gravity. Gravity is a REALLY weak force after all!). My dad was cheering me on and together, he and I drafted a research essay citing scientific journals, explaining that she didn’t witness this phenomenon firsthand, she was just duped by a tourist scheme. When I got in trouble for “back talking” her, my dad rewarded me with ice cream.

In high school, when I was accepted into a University Chemistry Program (yes, I was the kind of girl who wanted to attend school during summer vacation), my dad dropped me off at the local university every single morning. My parents attended all my science fairs and we celebrated, with more ice cream, when I competed in the state competition (eventually scoring the highest in my entire school!).

Whatever it was, my parents were always supportive of my pursuits. Whenever I decided to do something, they were the first people there to cheer me on. But despite this, and even though I was never discouraged from my interest in math and science, I also wasn’t ever encouraged to take my fascination with math and science and make it into a career. I didn’t need a career; I was a girl. My younger brother, meanwhile, was being raised with some very different messages.

I only have one brother (and he is so gifted and talented). We’re 18 months apart age-wise, and that interest in math and science I’ve mentioned—he has it too. But despite the similarities in our situations growing up, despite coming from the same home with the same interests, my brother and I have gone through very different paths when it comes to getting our degrees. His path took him across the country to the prestigious, West Point Military Academy (one of the top schools in the country), while my path took me to the local state school. And, while there are plenty of reason our paths are so different, I believe the patriarchal culture we grew up in is a big one. The biggest reason, really.

I didn’t know you could have a career AND be a mother.

Since I was a child, education for the girls in my neighborhood wasn’t nearly as high of a priority as it was for the boys. I was expected to go to college, find a husband, and then quit my job once I started having children, this is known as the Mrs. degree. Again, I was told that I only needed to go to college so that I’d have a “backup plan” in case something happened to my husband. College is expensive. Why pay tuition if you’re not going to use it?

The idea that I get an education for the betterment of myself and intellectual pursuits wasn’t even part of the conversation. Women don’t need education to “nurture”.

My brother, on the other hand, was getting ready to go to college since childhood. He was encouraged to build forts, and Santa brought him math books, tech, and tool sets each year. Now, Santa was very good to me too. I had probably 100 dolls from Santa—all of which I loved. And I know I was so lucky to get presents on Christmas at all. But what Santa brought me was different than what Santa brough my brother. I was given toys and pink fluffy things. Remember my love for sudoku I mentioned? Sudoku is not something my brother also loves. He has probably only completed a handful of sudoku puzzles in his life, while I do hundreds of sudokus each year. But despite my love of sudoku, Santa got my BROTHER a sudoku book for Christmas. If I were to guess, my brother doesn’t even remember this gift because it was so unimportant to him. A year or so later, I saw this book unopened on his bookshelf and stole it. In fact, I still have this book to this day, it sits completely filled out on my bookshelf. I doubt my brother has even noticed it’s gone.

And remember that University Chemistry summer class I mentioned? Once I discovered, applied, and got in, my parents decided my brother should also attend a university program, so they went searching for a university summer program FOR HIM. Notice that no one went searching for a university program for me, I had to find it myself. My brother wasn’t even interested in summer school, yet my parents looked for a STEM program for him because it was a great opportunity. The same pattern follows with college. No one helped me with college applications, and I only ended up applying to the local state schools nearby. When it was my brother’s turn to apply for college, my parents encouraged him to apply to amazing colleges all over the country, and the Bishop even wrote him a letter of recommendation to get into West Point. The community looked out for my brother and not for me.

Remember: my brother and I are only 18 months apart, and I mention this again to emphasize that there wasn’t a big difference at all between our situations growing up. Yet the response to our ACT scores was starkly different.

When I took the ACT, I took it once, without any prep or study material (I didn’t know the importance of the test back then 😱) and my parents were proud of my score: 25. We celebrated with (you guessed it) ice cream! I felt great until….my brother took the ACT and got a 28, but there was no celebration to be had. Instead, my parents said that he was smarter than that and spent hundreds of dollars on private tutors until he scored a 35.

I want to be clear: I don’t think it was malicious that my parents paid for private tutors so my brother could get a higher ACT score and didn’t do the same thing for me. Maybe they were just ignorant about the importance of ACT scores when I was in high school, but figured it out 18 months later when my brother took the test. Or maybe they honestly thought that my brother was much smarter than his score and didn’t think I was capable of getting a higher score than a 25, so a private tutor would be a waste of money. Or maybe it was truly an oversight on their part. Regardless of the reason, the message was clear—my brother’s college application was worth investing in, while mine was not.

So naturally, I have complex feelings towards my parents and their support of my interest in science and math. They fully supported these “hobbies” of mine, but their involvement stopped short of encouragement. On one hand, they were helping me write papers to my science teacher’s correcting them. While on the other hand, they were also saying things like:

“There is no better time to be a woman, they get all the scholarships (and they still don’t want to be engineers).”

or

“She only made partner because she is a girl, she didn’t deserve to become partner so young.”

or

“Girls just don’t like math and science, and that’s okay. You are the exception, JoCee, and that’s so cool!”

Or

“She’s just going to college to get a MRS degree, she will dropout once she gets married.”

Maybe now is when I should mention that my mother doesn’t have a middle name. She and her sisters weren’t given middle names by their parents because a women’s last name would become her middle name when she got married (in the LDS faith it’s just assumed you’ll get married and take on your husband’s last name). This is all my mother knew, so following tradition, she also didn’t give my sister and I middle names either. My brother on the other hand was given a middle name. In fact, his middle name is my father’s name, also following tradition.

All of this is to say that my parents raised me with love and opportunity. They raised me the best that they are able. But they made mistakes. In their defense they were also both raised by the patriarchal model of the LDS church. They believe that men should protect and preside, while women should nurture. They were happy in their designated gender roles, and isn’t happy all you want for your children? They knew that this church, including these strict gender roles, made them happy, so that’s how they raised their children, in hopes that their children would also be happy.

Years later, when I told my parents that I don’t feel like they encouraged me to go to college, they fought back against this adamantly. It was always assumed I would go to college, and it was also assumed that they would even help pay for college. This is true, I do think that THEY assumed all of their kids would go to college, but—because it was assumed—they didn’t talk about college at all. And since my parents weren’t actively encouraging my education, the voices from my community, church leaders, and other family members discouraging me from attending college (especially for engineering) were louder.

Afterall, it takes a village to raise a child, especially in Utah. My parents weren’t the only adults in my life. Growing up LDS, you spend a lot of time with church leaders. You go camping with them, do weekly activities together, and play on the same sports teams. It is a very tight-knit, loving, and supportive community. I knew I could always count on my church youth leaders to give me a ride if I got stranded, or a place to stay when I accidentally locked myself out of the house. Many of them were like second parents to me!

They believe that men should protect and preside, while women should nurture. They were happy in their designated gender roles, and isn’t happy all you want for your children?

And even though I didn’t know any women engineers growing up, there were plenty of male church youth leaders who were engineers and who I got to spend a lot of time. In fact, the richest, most successful, and highest acclaimed engineer was my BISHOP. An LDS bishop is the highest local church leader (LDS church leaders are always male. Females aren’t allowed to be church leaders). The bishop’s primary responsibility is to take care of the youth as an untrained volunteer. What a great potential role model for a teenager like me, with a love of science and math: an engineer who can help her find her way into a career! And I was twice as lucky: not only was this engineer my bishop, but he was also my basketball coach! Score 🏀, right?!?

Plus, I got plenty of 1-on-1 time with this amazing engineer because… I was a sinner. The LDS religion expects complete abstinence before marriage. If you have any kind of sexual relations these sins must be confessed to your bishop. I was never taught any form of sex education besides abstinence, so all forms of sex were sins to me—including assault (I suppose this is my #meToo moment). My first sexual experience was at the young age of 14 (with a guy who was 18). I won’t be going into the details of this, but it’s sufficient to say I was having sexual relations as a young teenager; some consensual, some not. And since I was having sex, I needed to tell my bishop about it.

One of the beliefs of LDS members is you MUST confess any major sins to the male bishop who will help you find forgiveness from God. You can’t confess to your parents. You can’t confess to any other adult you trust. You must confess to your bishop (God has proclaimed this, so don’t even try to argue it). I met with my bishop monthly for three years as a sinner.

When you “confess your sins” to this bishop, the door is closed and it is a private conversation. Just you and the bishop. Bishops aren’t given background checks. They also aren’t trained for these situations when they’re appointed leaders of the local church. I am not sure why anyone would think it’s a good idea for an adolescent girl to talk about sex with a much older man (who is not trained in dealing with adolescents) in a private room. But this is the doctrine and it’s the ONLY way to be forgiven. So for three years, every month, I would sit in the hallway reading a book until my bishop called me into his office, where we would talk about my sex life.

During these conversations, my bishop would give me advice like: “Pray for your future husband that he is strong enough to withstand the temptations you are experiencing”, and “Pray to become clean enough to be married in the temple”, and “Pray that you can become strong enough to avoid these temptations”—putting the full blame of sexual intercourse (including assault) purely on my shoulders.

Despite meeting with this amazing engineer every month for over three years, we only talked about engineering ONCE… when he asked me if I thought I could become an engineer while still having a family. A question I can guarantee he never asked the boys in the church. And likely not a question he encountered when he was pursuing HIS engineering career. I can’t help but feel remorse for the wasted opportunity here! An amazing engineer had monthly 1-on-1 time with a young teenager who loved math and science, what an easy opportunity for positive mentorship, for providing career advice or even book recommendations. But instead of talking about our shared interest in math, science, and engineering, he chose to focus the conversation on my sex life.

The conversations were not good, and nine years later I can look back and see just how abusive they were. But as a young teenage girl, I didn’t know any better. My parents, all of my religious leaders, and everyone in the neighborhood encouraged me to continue talking to him. The alternative was Hell, literally.

Quick tangent—the LDS church still teaches that everyone — including children and teenagers—must confess their sins to the bishop. The potential for abuse here is too great. As long as this practice is taught and encouraged by parents, this abuse will continue to happen. If you are a parent, I plead with you to encourage them to come to you or a professional about their personal life and “sins”. The bishop is NOT who they should be talking to.

Okay, back to me. The three years I was talking with my bishop as a “sinner” were the darkest time in my life. I was struggling with my self-confidence. I struggled to find friends who had the same passions and interests as me (i.e. math and science). It also didn’t help that I was a sinner and that all the youth in my neighborhood knew I was “confessing my sins” to the bishop.

Eventually, I ended friendships with nonchurch members, I quit the basketball team (my bishop was no longer my coach at this time, but it was still a triggering to play basketball), and I dropped almost all of my classes to instead do an elementary education internship by the request of one of my church leaders. That’s right, I dropped out of most of my high school classes. Goodbye, any Ivy League colleges!

Although I loved my time spent teaching second graders, this decision to limit my high school education would eventually have downstream negative effects on my college applications. This is a choice I regret today, but at the time I didn’t know any better. My church leaders encouraged this choice. My parents encouraged this choice. Society encouraged this choice since being a teacher was a “safe” career to have with children. Could I have known any better?

I didn’t completely change during this time, though—I still loved math and science. So the ONLY class I took by my own choosing was AP Calculus. Buckets of fun, I know.

My calculus teacher was an amazing woman who had a gift for teaching math. She was also getting her Ph.D. in mathematics and teaching at the local university, while also raising two young children. I am not exaggerating even slightly when I say that she was my first real role model. She was so smart, well-read, had an impressive career, AND WAS A MOTHER. The first mom I knew who made a career out of math and science! She came from Cornell, so it became my dream to go to Cornell (I didn’t even know where Cornell was at the time, I only knew I wanted to be JUST like her).

You could often find me hanging out in her classroom before school and during lunch. We talked about books, math theories, her career, and college. She helped me think critically about college as more than a means to find a husband, or a backup plan if my husband couldn’t work. To treat college as a way to satisfy my intellectual curiosity and create meaning in my own life. That maybe I should consider other career options besides elementary education, maybe even something as preposterous as engineering. She showed me it was possible to be a mother and have a career. It took one positive role model who looked like me to show me that my life could be so much more than I had envisioned for myself.

She eventually wrote me a letter of recommendation for a Women in Math and Science Scholarship at the University of Utah, which I received and where I ended up attending. It’s not Cornell, but my decision to drop all my classes in high school ruined any real chance I had at going to anything more than a state school, so University of Utah it was.

Part of this scholarship included a research placement in the lab of my choice. Doing research as a freshman at a university is very impressive. I could pick any lab to do research in. And I narrowed down my selection of research positions after taking one glance at the paper with all the research department heads. Of the dozens of department heads in the college of engineering, only one face was female. So I joined her lab.

I look back at these early years of my adult life and want to give my younger self a hug. I was clearly just searching for any women role models I could find. I was looking for someone who looked like me and was still considered intelligent and was respected.

In college, life started becoming less dark. I was still talking with my bishop (since I was still a sinner). But, at least, I was surrounded by people with similar interests, AND I had two female role models helping me navigate a career in ways that my parents and neighbors weren’t able to. I was also receiving plenty of scholarships and awards and was doing what I loved every day—math and science!

But being a woman while pursuing an engineering degree is very difficult. For every scholarship, recognition, or award I received, I also received accusations and snide remarks that I’d only won as “the token women” instead of from my own engineering abilities. It was also a lonely endeavor to get my degree. Women make up less than 18% of Computer Science degrees. In my graduating class, I think I was 1 of 15 females in a class of over 100 people. More than one TA made unwelcomed advances towards me. Because of my gender, I was the brunt of many jokes about how I was sleeping with professors to receive my good grades. I also had to constantly fight the remarks, memos, and news articles that stated females just aren’t naturally as capable at math as men, and that women don’t deserve to be in engineering since we just drop out anyways.

One of the hardest parts about being a woman in engineering is that despite it being so difficult to get there, men continue to claim that it is EASIER for women to get a degree than men because there are a handful of scholarships meant to close the very wide gender gap in engineering. These biases are known and yet I constantly felt like I needed to defend my intellect. Something I’m sure my male classmates weren’t worrying about.

Six years later, I graduated with a degree in computer engineering. I didn’t graduate with honors, but I did graduate with a job offer and a large salary! I have now been in the professional engineering world for four years, and I am facing another uniquely female engineer problem… In a sick twist of fate, I am afraid to leave engineering.

50% of women in engineering will leave engineering by the age of 35. Not because they aren’t smart enough, not because they aren’t capable of doing the work. They leave because they don’t see career growth for themselves if they were to stay in engineering. For example, only 20% of Chief Technology Officers are female. Chief Technology Officers are the highest technical role in a company and they lead a company’s entire engineering efforts. And only 1 out of 5 of them are female. It’s hard to envision a future in engineering if there isn’t anyone else like you on top.

Of course, there are also a few other things holding women back in engineering. It’s only been 100 years since the first-ever Women’s Engineering Society was created. Before this time, women weren’t allowed in unions, weren’t allowed to wear pants, and couldn’t receive college degrees—all of which were prerequisites for being an engineer. Women weren’t even universally allowed into universities, so I think it’s fair to say that men have had a couple thousand years head start in the engineering field. The first male engineer appeared in the 27th century BCE: Imhotep, who designed the first Pyramid in Egypt. The first female engineer, Pandrosion, didn’t appear until the late 4th century CE, and she was mistaken as a male at first! You heard me: the first female engineer didn’t appear in history until 3100 years after the first known male engineer!

Another barrier for women in engineering is that women are still expected to do the majority of unpaid household work. In the United states, the average women performs 150 minutes more unpaid labor than their husbands…even if they are a breadwinner in the family.

I can’t help but be angry when I read these statistics. I want to encourage other women to go into engineering. I don’t want girls to grow up like I did, thinking that college should just be a “backup plan”, and that their full worth in life only comes from raising a family.

If a man leaves engineering to pursue something different, people don’t think of that as anything more than what it is—a man interested in doing something different with his career. If I leave engineering, then it is sure to be interpreted to mean that I wasn’t able to make it as an engineer, and that my failure reflects on how ALL women can’t make it as engineers. I don’t want me leaving engineering to be used against future women thinking of pursuing the field.

But even though I currently feel trapped in a patriarchal system and afraid to leave engineering, I know that I’ll overcome this. I want to further my education. I have passions I want to explore. I’ve already fought against the gender stereotypes of my childhood religion, I’ve fought the social stigmas, and I’ve fought the restrictive, internalized view I had of myself.

I’ve also realized that my value is more than being a mother and nurturer. That an education and career make me happy, so they’re worth investing in. I know that my career choices aren’t limited to stereotypical women’s careers. I’ve come to know that I can do anything with my life, like becoming an engineer, or like changing careers into a whole new field. Because my career is what I choose my career should be, not what these patriarchal systems says it should be.

I awake from these righteously angry daydreams, swallow glass,

and make art with the aftermath.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!