“these men were dangerous and not to be trusted“

Amy is joined by journalist Elle Reeve to discuss her book, Black Pill: How I Witnessed the Darkest Corners of the Internet Come to Life, Poison Society, and Capture American Politics. This conversation establishes the histories and intersections of incels, the alt right, and white supremacy movements, plus these subcultures’ plans to strip away women’s rights and what we can actually do about it.

Our Guest

Elle Reeve

Elle Reeve is a CNN correspondent whose work has won numerous awards, including the Emmy, the Peabody, and more. Her writing has appeared in VICE, The New Republic, New York magazine, Elle, The Atlantic, and The Daily Beast. She lives in New York.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: If you are listening to this episode on the day of its release, then it’s the day after the 2025 presidential inauguration. Donald Trump has just been sworn in as the 47th president of the United States, and as we enter into this second term of divisive leadership, many of us are apprehensive of what lies ahead. After all, it was the last Trump presidency under which we saw more and more white supremacists and aspiring fascists marching brazenly through the streets. Many of us might have been surprised to see open racism and misogyny, which seemed to be creeping out of the woodwork, and our entire country was rattled by the worst of these occurrences, like the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville and the insurrection at our nation’s capital on January 6, 2021. These events and other acts of alt-right terrorism have left permanent scars on our national identity and will likely have consequences spanning far beyond what we can presently see. And so, with that in mind, I am so grateful to be joined today by a woman who’s been studying the alt-right, white supremacists, and other extremist movements longer than most of us have even been aware of them. She was a boots-on-the-ground journalist in Charlottesville as well as on January 6th, and she is the author of the book Black Pill: How I Witnessed the Darkest Corners of the Internet Come to Life, Poison Society, and Capture American Politics. Please join me in welcoming to the podcast, Elle Reeve. Welcome, Elle!

Elle Reeve: Thank you so much for having me.

AA: I’m really, really interested in the work that you’re doing and I’m so excited to talk about it with you today. First, I’ll introduce listeners to you through a quick professional bio, and I’ll ask you to introduce yourself more personally after that. Elle Reeve is a CNN correspondent whose work has won numerous awards, including the Emmy, the Peabody, and more. Her writing has appeared in Vice, The New Republic, New York Magazine, Elle, The Atlantic, and The Daily Beast. She lives in New York. That is a very, very brief bio. I’d love for you to talk a little bit about who you are, what brought you to the work that you do today, and a little bit about what makes you you.

ER: Oh, sure. I actually have an easy answer for that. I was born in downtown Atlanta in the ‘80s at a time when there was this panic around the inner city. Most of my neighbors were Black and most of my classmates were Black, and we grew up studying the Civil Rights Movement as sort of the pinnacle of American history. The history classes would sort of peak there. Then when I was 13, I moved to a very white town, a small town in Tennessee, and it was very evangelical, very conservative. It was the ‘90s, Rush Limbaugh was really a big, powerful, cultural– not just political, but a cultural movement. And history classes would peak with the Civil War. And that’s just something I noticed as an eighth- or ninth-grader, just the differences in the narrative of American history. I saw two very different sides of the South, and that’s what’s really been important to how I see the world now.

AA: Hmm. That’s really fascinating. Just side by side, your actual history curriculum, and that’s informing young Americans’ civic engagement and how they relate to each other for the rest of their lives.

ER: Yeah, history class is just one example, of course, there were these vast differences in the ways people talked about political and cultural issues, but it gave me an ability to be a little bit outside of my own experience. I didn’t grow up around families that were exactly like mine. There were a lot of immigrants in our neighborhood as well, and it just gave me a really interesting perspective.

AA: Yeah, that’s really fascinating. How did you become a journalist? How and why?

ER: My family, we had to move to Missouri for healthcare, is the short story, and the University of Missouri had a very good journalism program. So I was like, “Well, I’ll try that.” I was kind of interested in politics, but once I saw politics close up, I didn’t want to be on that side of it. And George W. Bush had been reelected as president, and there was this, kind of like today, this cultural conversation on what the elite miss on the coast. And at that time it was “values voters” instead of Trump supporters, that was the big buzzword. And I was like, “Hire me, I will explain middle America to you. I’m your girl.” And that’s how I got my first job.

AA: Wow. Oh, that’s so interesting. Amazing. Well, let’s skip forward to now and talk about your book. But before we dive into the book itself, I’d love you to define some terms. First of all, let’s talk about your book’s title, “Black Pill”. What does that mean when you refer to that within the book?

ER: Sure. The short answer is it’s a dark and gleeful nihilism that the world is going to burn and you’re going to enjoy watching that. The longer version is that it’s a spinoff from a term from the Matrix, the “Red Pill”, which I’m sure most people are familiar with now. It generally means taking right or very far right views. It’s important to remember that in the Matrix, the Blue Pill is where you go back to the illusions and the Red Pill is where you go back to the harsh reality. So it symbolizes not taking on a new set of ideas, but that you’ve been stripped away of your illusions and your ideology and you’re just seeing the truth. “Pilled” became very popular, like you can be crypto-pilled or Russia-pilled or whatever. You hear it on the left now, too. Like this 4chan, you know, message board culture has spread all across the country, it’s just infected everything. But the Black Pill I think is the most relevant because it’s a way that people give themselves permission to make moral and ethical decisions they wouldn’t have otherwise. Why adhere to the morality of a corrupt and bankrupt society? You shouldn’t. You’re above that. You don’t have to play by those rules.

AA: Got it. Okay. A couple of key groups that come up a lot throughout the book are incels and the alt-right, and I think probably most listeners have at least like some familiarity with those terms, but I’d actually love you to dig in and give us a crash course on who those groups are, what they believe, and how they relate to each other.

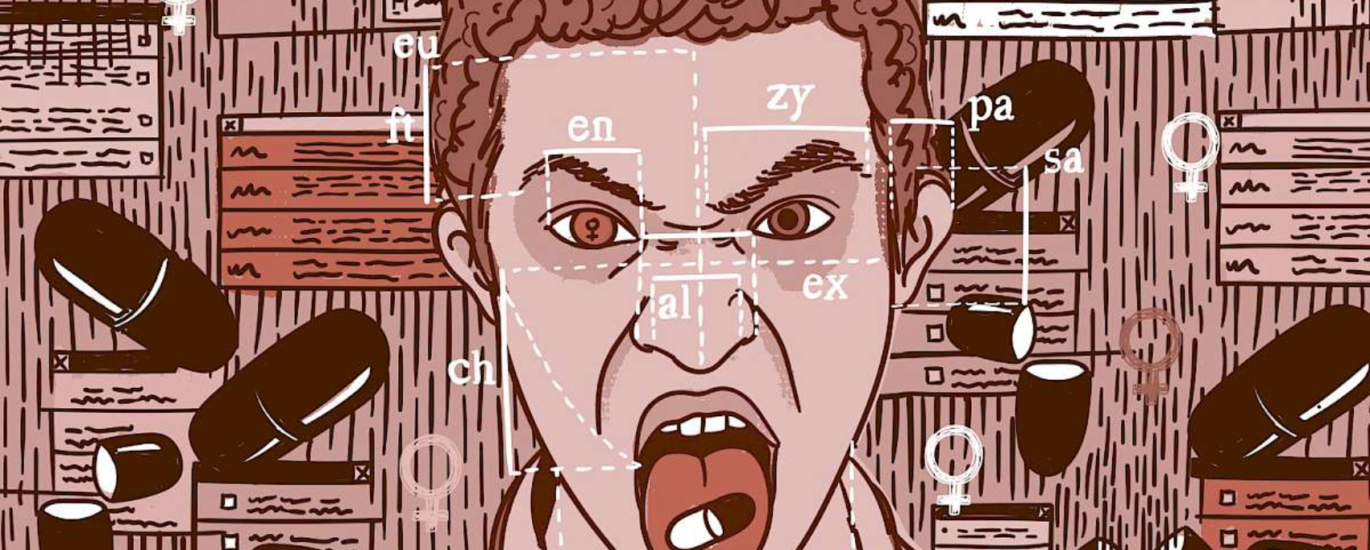

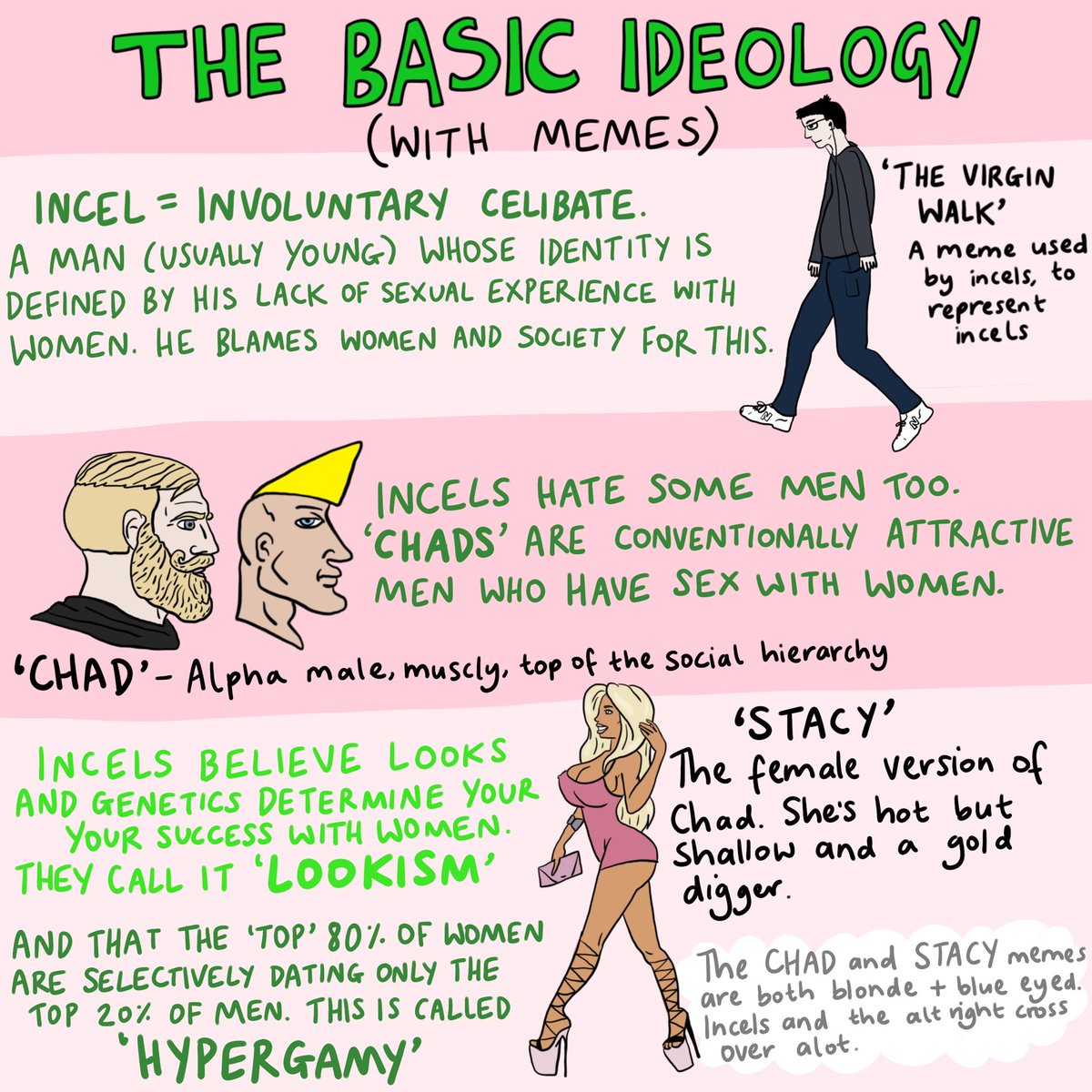

ER: Incel stands for “involuntarily celibate.” It started in the ‘90s, but it really got going in the early 2010s. It’s mostly young men who are politicized virgins. They believe that because of feminism, they are doomed to never have sex because they’re ugly, or they’re awkward, or maybe they’re autistic, or there are even men of color in those groups, so they think being Asian or Indian means they won’t be able to get the girls that they want. It is filled with all this slang that is absurd and easy to laugh at, and it’s important to understand that they know that. They view themselves as pathetic, losers, lowly, like there’s a real self-awareness in this culture, but you do have to take it seriously because it has produced several mass murderers.

The alt-right is a sort of section of white nationalism that existed from, let’s say, 2008 to about 2019. It really got going when Trump started running for office in 2015. Obviously racism has been around a long time, but what separates the alt-right from that is that it was not geographically based. There aren’t local Klan meetups or citizens councils. It was internet based, it’s younger. It was mostly atheistic at that time and heavily influenced by the incels, extremely misogynistic to the point where old-school neo-Nazis were really put off by it.

AA: Wow, I didn’t realize that. Interesting. Okay. And both of these groups, incels and alt-right, I do picture there being a lot of overlap in who’s involved in these movements, and it seems like a lot of the discourse happens on online forums. You just mentioned like 8chan. I’m wondering though, because to write this book you met with these people, not with their online persona in front but actually as human beings, so I’m wondering from your experience firsthand, do these men act with as much misogyny in real life as they do online? And do you get the sense that they really practice and believe what they preach, or is it kind of like a macho persona that they project?

ER: Well, a line I heard over and over in different contexts was “it started as a joke and then became real.” For example, two white nationalists who were very heavily involved in Charlottesville, their internal communications were made public as part of a trial over their actions in Charlottesville. And they’re objecting to the close reading of their jokes, their racist jokes, their glibness about violence and all that. And they’re telling me, “Oh, we’re just doing that to troll the media. We’re just doing that to get your attention, to make people think we’re crazy and then we’ll draw more people to the movement.” And I’m like, “But you were saying this to each other in a private chat room for what, like you thought that in five years I’d be sitting here asking you about it being on trial?” If you’re doing the bit alone and in the shower, it’s not a bit anymore. So mostly I met people along different parts of the path in that process of those ideas hardening and becoming more and more of their personality.

Fred Brennan, who created 8chan and later tried to destroy it, the way he put it was that you can sort of anonymously try on these ideas if you’re curious and see if they fit and then you practice it over time and eventually you become this thing that you were just joking about. Some of them would be polite to me in person, some would be trying to be polite and still say really bizarre misogynistic things to me, an incel I interviewed in person in particular. And then I definitely had people just scream racial slurs at me.

AA: Racial slurs at you? You’re white. That’s interesting.

ER: Right, I’m white, but they knew I would be offended. And they see the media as liberal media, they see me as a tool of all that opposes them and they hate women. So, you know, they know that that would offend me to hear the N-word even though I’m not Black.

AA: And they would be right that it would offend, right?

ER: I mean, this was very early on. This is a thing that actually happened to me on a phone call, and I was shocked. I’d never heard a white man screaming the N-word at the top of his lungs over and over and over to me. And I’m like, “Oh my gosh.” I didn’t say anything because it’s not just that he’s saying this thing to offend me, he’s debasing himself so much in order to get to me. And that is also kind of horrific to observe.

AA: Yeah. So who are these people, Elle? What is the process? Because you said that they’re at different points in the process and they can try on these personas, and then sometimes it hardens and calcifies and becomes who they really are. Why would a person even be attracted to try on some of those ideas in the first place?

ER: Yeah, I mean they can come from all different places, but there are common themes. Usually it’s younger men who think of themselves as smart and funny, but have some struggles socially. A lot of them identify with autism. Now, two important ones that I have interviewed actually were diagnosed with Asperger’s in the ‘90s, so in some cases this is genuine, but in others it’s a self-diagnosis or just an affinity. And a really big piece of slang in this world is “autist,” as in someone who seems to have the characteristics of autism. And you can use it as a term of derision, like when someone is acting ridiculously and you want to put them down as sort of not in control of their emotions. Or it can be a term of endearment, you know, like during Pizzagate, there was a Reddit post called like, “this is weaponized autism.” Now, of course, I know that many people would find that offensive. They know that and that’s what they like about it.

If you’re doing the bit alone and in the shower, it’s not a bit anymore.

AA: Interesting. And then I’m curious also about the ideology itself. Let’s say there is a young man who does feel maybe alone and alienated and like, “I’m seeing other guys get the girls. That’s something I want. I’m feeling left out.” And then they find a group online and they’re trying on these ideas. Who are the originators of these ideologies who’ve established kind of the narrative that these people would find? Because it seems like these young people are kind of vulnerable, maybe in some ways, and being indoctrinated by these bigger ideas, these more powerful entities. Who are those power players that started this?

ER: That’s really interesting. It’s kind of a complex question. So, 4chan on these message boards, it’s completely anonymous and that is the draw because the person’s position in society cannot be used against them to argue that their ideas are not credible, right? There are many documentaries in the ‘90s about Klan members or whatever, and the cliché is a trailer park in Alabama. They very much didn’t want to be portrayed that way and they’re self-conscious about being portrayed as trash. They said this to me. So, this is a world where it doesn’t matter who you are and you can be a different person every day because it’s so completely anonymous. More broadly, there’s long been a kind of intellectual wing of racism. I mean, people who have done scientific research purporting to show that white people are smarter than everyone else or white people are more altruistic have testified before Congress, like in the ‘70s. And that was funded by the Pioneer Fund, which is a racist, anti-immigrant group. So there’s a long sort of infrastructure, like intellectual infrastructure for scientific racism.

So what you’ll see on 4chan is that these kids will make collages of different charts purporting to show that, say, Black people commit crime at a higher rate. Or they’ll show maps of genes, and if you show a specialist in that area, it doesn’t really make sense, but what it shows is that Black people being here and white people being over here and how they’re not actually connected, like they’re not genetically closely related, which isn’t true.

AA: No, of course.

ER: There’s more genetic diversity in between two tribes of orangutans who live on opposite sides of a river in Cameroon than there is in the entire human race. We’re just not that different from each other. So they will find these old-fashioned sort of Tweety racists, I mean, they have conferences, they have book publishing companies, and they’ll put these maps together and those will go viral and you see them pop up again and again. For example, a collage I had seen before was in the manifesto of the Buffalo shooter, so that’s one place, but it’s also kind of self-generating. I mean, the message boards are like a market testing ground and they see what ideas bubble up to the top. The first person who ever texted me a picture of Drag Queen Story Hour was a teenage fascist troll in 2017, a long time before it became a big part of the national discourse.

AA: And he just made it up to see if it would get a lot of traction or if it would be inflammatory?

ER: It was an image that was going viral in that world.

AA: Wow. And they just love, it seems like– I mean, this whole concept of watching the world burn. And what I’m hearing a lot from what you’re saying is, well, I guess I’m trying to get a sense of how much is real conviction inside, this is what they really believe versus just wanting to be controversial, wanting to pick a fight with the “liberals” just for the reaction of it. I guess it’s kind of hard to know what people are actually feeling inside.

ER: Well, it starts one way and ends up the other way. I actually brought this question to Richard Spencer in 2016, right after Trump was elected. I thought this really diminished his movement that the vast majority of his followers were these teenage trolls who were just trying to get a rise out of people online. And they’d posted so much racist stuff, they started believing it. And he was like, “Yeah, there’ve been lots of guys who’ve come up to me and said, ‘Hey, I just started researching anti-Semitism or racism in order to offend people better, but then I red-pilled myself, and now I believe it.’”

AA: Oh, I see.

ER: And I think a really important takeaway, generally in all of politics in this digital age, is that just because it’s stupid doesn’t mean it’s not powerful. I even had conversations with people who helped organize Charlottesville who were like, “Well, James Alex Fields,” he’s the man who drove his car into a crowd and murdered a woman, “Did he really believe it? Was he really one of us? He didn’t really get all the ideas.” And I’m like, he drove halfway across the country all night. He wore the polo shirt, he wore the shield, he drove. He believed it enough. How much more does he need to truly believe it?

AA: Yeah. Well, that brings us to the next question I wanted to ask, because I know you were present in Charlottesville during the Unite the Right rally, and I know you’ve spoken about those experiences both in the book and in other interviews. I don’t want to ask you to relive it if you don’t want to, because I know it must have been really traumatizing, but I’m wondering what experience you had, and maybe some knowledge and takeaways that you’ve taken with you from that event, and what you wouldn’t mind sharing with us.

ER: Charlottesville kind of happened over three days. The first night was a Friday night. I knew that there was going to be some kind of event, but I didn’t know what it would be, and we figured out it was going to be at this one field on the UVA campus. So we park and we’re kind of staking it out and we see these vans unloading a bunch of guys in polo shirts, over and over and over. And it’s like, “Oh, this is actually organized.” So we’d go out across the field, we’d get up on a road above it so we could look out, and they’re lining people up and handing out tiki torches and stuff. Then they all light the torches at the same time and that’s when boom, you can see that it’s a crowd of hundreds of people snaking through the yard. And that’s when I really realized the risk, that this was really big, that it had drawn real numbers of people who are willing to show their faces. Not a Klan rally, no one was wearing hoods. That was a real moment for me.

So they started marching through the UVA campus and they went the wrong way. They had intended to march to a Thomas Jefferson statue that was only five minutes away, but they totally got lost. So they’re winding all the way through and they’re just amping themselves up along the way. And this is when I sort of came to start understanding mob mentality, because you really can feel the human emotion conducting through the crowd like it’s electric. It really is electric. And they were just howling like animals and they had planned to say, “You will not replace us,” which was sort of their PR version of portraying themselves as sober young men just standing up for the existence of white people. Like, “It’s okay to be white” was another one of their slogans. “Why should white people be erased off the face of the earth? We just want to keep existing.” That’s the idea they wanted to promote. But they got too hyped up and they said, “Jews will not replace us,” alluding to their conspiracy theory of the Great Replacement, that Jews are intentionally importing people of color in order to dilute the white race. And then it ended at the Thomas Jefferson statue where there were a couple, I think maybe two dozen at the most, college kids standing around, sort of saying, “No, this doesn’t represent us.” And it was a total melee. These guys encircled them and beat them up, and it was crazy. We lost our camera guys for a moment in the crowd. I mean, they were fine, but it was just so insane. And then it dispersed.

AA: Oh my gosh. And you watched this happen. You were there watching people get beaten up and yelling these racist things.

ER: Yeah, it was a total dog pile. It was so insane. I climbed on a sort of chest-high mini column, I climbed on top of that just to try to see in the crowd to see our guys and I couldn’t find them because there were too many people finding each other. And then it dissipated. And a white nationalist I had interviewed earlier that day, Chris Cantwell, is there almost crying because he’s been maced and like how terrible it is that he’s been maced. And he really felt like the victim. And in my subsequent conversations with him, he would come back to that over and over how he had been so horribly attacked and maced. And I’m like, “But you encircled those people, you outnumbered them 10 to 1” and he corrected me, “No, probably like 20 to 1.” And I’m like, “You still feel like the victim?” He’s like, “Yes. We were the ones who were attacked.”

AA: Wow. Who maced him? Who did they claim was attacking them?

ER: They claimed Antifa. I don’t know if they know for sure. I mean, the cameraman I was working with also got maced a little bit but, you know, they kept doing their job.

AA: Wow. For listeners who can’t see me, I have my hands over my face. I just can’t imagine what that actually would have felt like to be in the presence, like you said, well, I mean, a Klan rally would have been its own horror as well, seeing the hoods. But to see people so brazen and to be saying those things out loud, I think what is so terrifying about this movement and the alt-right getting more power is, like we said in the intro, people coming out of the woodwork and realizing how many people actually may have been harboring these horrible racist and misogynistic views the whole time, and now they’re not scared to say them in public anymore and to take action. It’s just absolutely terrifying. But you’ve talked about how Charlottesville was mostly a group of white men, but then you describe how the people storming the Capitol on January 6th were more diverse, a more diverse gathering of people, including significantly more women. That’s really interesting, and maybe we can shift our attention to that day, because you were there too. Is there anything that you’d like our listeners to know about what happened that day and why there were more women present on the 6th?

ER: Yeah. So, QAnon was the animating idea for a lot of people there. In QAnon, there is a nefarious cabal that’s manipulating the world to do bad things, but it is Democrats and liberals and Hollywood, and they are hurting children for their own enjoyment. That is a much more palatable idea than like, “Jews are trying to hurt the white race.” Most Americans are not cool with Nazis. In the American mythology, we beat Nazis. These Nazis are weird creeps, losers.

AA: Yeah, they’re the bad guys.

ER: They’re the bad guys and it’s always going to be that way. So QAnon had a much larger potential audience. Who doesn’t want to protect children? It also wasn’t explicitly racist, it was not explicitly misogynist. I met a Black woman there who said she was stopping socialism. I met immigrants there. Many more people also were motivated by the shutdowns during COVID. People were very, very, very angry about that and they were angry about the George Floyd protests, that those protests were allowed, in their terms, to happen, whereas they weren’t allowed to have their small business. And of course, there were some contradictions in what could remain open and what was closed, but those things combined to have really intense, bottled-up rage. And the other thing that I see in common with these two things is that it was a big online community where you feel like you’re talking to your best friends in the world even though you’ve never met them. That was all building towards one event, one day in real life where you’d get to meet those people in person and you’d all get to do the thing you believed in. And that’s why I think violence spilled over on both those days.

AA: Very interesting. So you’re saying that there’s a lot more of a broad appeal and that’s why you’re saying there were more women there. Because it wasn’t specifically narrowly focused on race and gender, it was a host of issues that were grievances for a lot of different people.

ER: There were women who were spokespeople for QAnon. Crunchy moms, we heard about that in the last election, but there was a significant crunchy mom presence.

AA: Mad about vaccines, probably, and stuff like that. That makes sense. Digging more into this gender question, in general, aside from January 6th, are there women in the alt-right? Because it does have such a strain of misogyny, I think of it being way more masculine and much more dominated by men, but I’m sure there are women in the alt-right movement. If so, who are they and what holds them there?

ER: Yes. There were a small number of women there who were very dedicated. Most of them in conversations with me, you know, I talked to several who left. It was funny, if I was at an alt-right event, sometimes it would be the one woman there who’d say the most misogynist thing to me. And I’d wonder, like, “Why are you like that?” So later, the women I talked to, many of them had some kind of trauma in their past and they came in through YouTube, often with videos of Richard Spencer or people like him giving a kind of professorial talk, you know, they didn’t come in with the slurs. They liked the idea of strong, traditional families. Some of them were looking for stability. The outside pitch is that women’s feminine virtues are going to be elevated and respected. That you can care for the home and that won’t be seen as silly or superficial or not serious, right? That the girly stuff will be taken seriously and you’ll have a man protector.

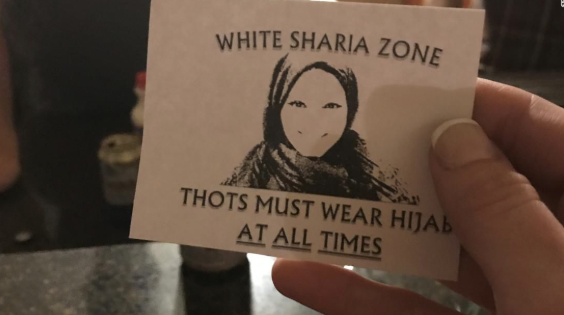

But in real life, that’s not what happened. In real life, the joke was made real. Many of these women were treated very poorly. Multiple have said in court documents that they were physically or emotionally abused. There was this concept of “white Sharia,” their idea of Sharia law that because women vote for more liberal candidates, that because they believe in social equality, the only way to make America what they wanted it to be was to prevent women from voting, holding credit cards, holding jobs, you know, they wanted to lower the age of consent, all of that. And it was just a joke. Other people in the alt-right thought it was just a joke until a woman started showing up wearing a burqa to these parties and they would pass out these cards that said “white Sharia” and all of that. And publicly, these women would present as though they were having a great time, but privately they’d be complaining to each other of their horrible mistreatment, about how these men were dangerous and not to be trusted, how the movement hated women. The one who was wearing the burqa often talked about feeling debased, dehumanized, that she would never respect herself again, do not trust these men, but then the next day she’d be right back out there posting about white Sharia.

the alt-right thought it was just a joke until a woman started showing up wearing a burqa

AA: Wow. I guess it surprises me a little, but then as I reflect on the very conservative, patriarchal, religious tradition that I come from, and having heard women I love, women I’m close to, defend patriarchy… And sometimes it does come from women who felt like they weren’t taken care of or maybe were abused as children, so what they then hang their hopes on is like, “Maybe my dad didn’t take care of me as a child, so I want a man who will take care of me.” And they want to align themselves with that power to feel protected instead of realizing that there’s another choice, which is a man who takes you seriously as his equal, right? It’s not just those two options: a man who doesn’t take care of you or a man who does because the default is that the man is going to be the protector and the leader. They don’t realize that there are more options than that. I can have compassion for them for that. If you do feel like you have been abused or you’ve been neglected and you feel weak, aligning yourself with power kind of makes sense, right? You can see from their point of view why they may do that and then why they may double down on like, “No, this is what I want,” even while they’re privately in pain about it. I know versions of these women, is what I’m saying, and it’s so frustrating seeing why they might be vulnerable and susceptible to that kind of indoctrination and internalized misogyny, but it breaks my heart.

ER: No, it’s very true. You see it over and over again. One woman who liked to troll incel forums, she told me that, one, she would depersonalize and not think of herself as a woman so that when they would say terrible comments, it wasn’t about her. She told me that she had been abused and so she really was drawn to the incel idea of ugliness and said she had this feeling like if she had been ugly, then maybe she wouldn’t have been abused.

AA: Oh, jeez.

ER: She talked about understanding eventually that these spaces reward cruelty and that the men were mimicking men they’d seen dominate women, you know, they were just trying to replicate that. They wanted to be that alpha male. What better way to display that to the other men than by dominating a woman?

AA: Yeah. Well, that leads us to the next question, which was: what are the factors that make boys and men susceptible to this? You write about how in all these alt-right factions, these are men who share feelings of frustration being ostracized and having their lives ruined for various reasons. But it’s interesting that from your writing it also seems that they’re angry and specifically angry with their fathers and other men. They’re angry at women and they’re angry at people of color, but they’re also mad at their fathers. The white supremacist Matthew Heimbach said, long story short, “Why do we become fascists? Because f*** our dads.” That was really interesting to me. Can you talk about that a little bit more?

ER: Yeah, Matt Heimbach, he was kind of a rising star in white nationalism in 2013. As a 19 year old, he started a White Students Union at his college. He grew up in a relatively affluent suburb in Maryland, and he felt that his dad didn’t pay any attention to the family because he was always seeking these external rewards for his work. He worked in public schools. And he felt like his dad didn’t have any of these traditional masculine skills, that his father couldn’t teach him how to train a dog or to fish, so he hated what his dad represented, which he felt was the destruction of the family while pursuing sort of capitalist success and ultimately an empty and hollow existence in suburbia. A lot of these guys, like one of the incels I talked to, had a distant dad and then his mom sort of took care of him, paid for his studio apartment, paid his rent, and he resented her for it.

AA: Wow. All these people, maybe we should just invest in therapy for these people because honestly there’s just so much pain! There’s so much pain that is not resolved and then it gets warped and twisted into these incredibly dangerous and harmful behaviors externally. Oh, these people just need inner healing, to be honest, is what I’m hearing.

ER: Yes, yes. That doesn’t diminish their responsibility for what they’ve done, but yes. Matt Parrott, who was sort of Matt Heimbach’s partner in crime and racism, he grew up without a lot of money and very not gifted athletically. He had a humiliating moment after playing two years of Little League that he actually hit the ball and he didn’t even get on base. He was still out at first base, but because he actually hit the ball, everyone cheered so much and they signed the ball and gave it to him. And he hated it. But he did have one thing, which was that he was very, very smart. He scored really high on an IQ test, he did very well on his SATs. And he now rejects this way of thinking, or says he does, but he said at the time that he turned into a cult of self-worship because this was cold hard evidence that he was smarter than everyone else around him. And people would say to him, “Matt, you’re so smart. If you just put effort into it, if you tried a little harder, you could do so much.” And he’s like, “Well, why would I put an effort in when I get praise for doing nothing?”

AA: Crazy. This just shows how inane, just utterly ridiculous it is in that baseball story. These people blame feminism and blame women for their pain when it’s patriarchy that’s causing their pain. That measuring stick that “I’m not measuring up to the other men, I don’t measure up as an athlete,” that’s not women’s fault. That’s patriarchy’s fault that you are in terrible pain and that you’re not respected for meeting those standards of masculinism. They’re misattributing a problem.

ER: They have always thought of it like the nerds have gotten their revenge. The meek have inherited the earth. The top of our society is not gladiators or like physical strength, it’s nerds like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. And yet, they’re still mad about it. They’re still mad that they’re not that archetype of masculinity. I’m like, “You won! You’re good at computers, like, be happy.”

AA: Haha.

ER: But they’re not. They would rant, incels in particular would rant– there are alpha males and beta males, and they would say that women would pursue alpha F*** sex, right? Meaning that women would date all the sexy alpha males through their entire twenties, and then when they’re becoming ugly and used-up and no longer valuable to society, they’d find a nice little beta who’d been spending all his time working hard, building a career, saving money, and marry him, stick around for a couple of years and then divorce him and take half his money.

AA: Hm, perfect.

ER: Yeah, I don’t know. They’re not able to conceive of a masculinity where they get to be the good guys. Does that make sense? Their only idea of masculinity is like, I don’t know, a fireman calendar or something.

AA: Yeah.

ER: They can’t conceive of being proud and strong and stable because they have a good job and have a good relationship and take care of their children. They just didn’t see it that way.

AA: Which is why we so need, I mean, one of the biggest takeaways for me throughout this project that I’ve done in Breaking Down Patriarchy is what a need there is for men like that. Men who are fully developed as human beings with all of the positive traits that we consider masculine and feminine. That these men speak out more and that boys can see good examples of present dads, kind men who are also strong. Maybe they like to lift weights, but they also love to read to their kids at night. They’re not mutually exclusive. We need more of these men, and for these men to be loud and talk about the joys of doing all of these things and that it doesn’t disempower or emasculate you to have a rich emotional life, for example, and vulnerability. Anyway, yes, it’s patriarchy that’s created this problem in the first place.

ER: Did you see on Twitter where Vivek Ramaswamy said, as part of this debate over H-1B visas, that there was something wrong with American culture because it doesn’t encourage excellence and therefore has fewer engineers and scientists because it values the jock over the nerd. And Ramaswamy obviously is not alt-right, but he has said some things that are from the online right world, and I’m just like, “There it is again.” You can graduate from high school, like, intellectually, this doesn’t have to follow you for the rest of your life.

AA: Yeah, that insecurity. Oh man, that is fascinating. No, I hadn’t heard that. Another question. You’ve been mentioning Richard Spencer a few times, and When you’re writing about Richard Spencer and the alt-right, you say: “Whatever the alt-right wanted to do to Black people, immigrants, Jews, Muslims, gay people, race traitors, all that would have to wait till after the fascist revolution. What they wanted to do to women, they could do right away.” So that bigger racial agenda that required scale, but the woman question started at home. That kind of blew my mind and was really distressing to read. So, let’s get into this. What do they want to do with women and how’s that project going?

ER: I mean, some of them would have them like slaves. Some of them, not all of them would joke that way. And again, as the alt-right later kind of fell apart, that has dissipated a little bit. But yeah, they wanted women to not have choices about how to live their lives. They wanted doting, submissive women who did not have jobs. Someone said that racism is a bigotry of separation, but misogyny is a bigotry of integration, like, you live with the person who feels this way about you. So, they could treat the women in their lives horribly. One woman said that she had run the women’s section of a large white nationalist fraternity. She said that when she left her boyfriend, they were like a power couple, at first he wanted her to publicly pretend to still be dating him because he wanted to project that image to other men. Squared away on top of his game. She claimed that he threatened to break her legs if she left, that he would do horrible things to her, that he could marshal this army of trolls against her. If you mistreat a stranger on the street, whether it’s for racism, homophobia, or anything, you could get punched in the face. But it’s easier over time to abuse the person you’re in a romantic relationship with.

AA: Mm-hm. It is. And we see that because of how domestic violence affects every country, every nationality, every religion, every socioeconomic bracket. That abuse of women is pervasive throughout all sectors of society to that point.

They’re not able to conceive of a masculinity where they get to be the good guys.

ER: I got the cell phone of that woman who ran the women’s part of what was called Identity Evropa. And it had not been connected to the internet since she quit, so I got the screen fixed, it had been all cracked, and I started going through it. I’m going through all these different threads, and when the women are even in groups of just women, they’re still publicly defending what these guys are doing, saying, “Oh, it’s just a joke. I didn’t get the jokes at first, but now I understand that they’re just doing their memes.” There was such an intense degree of rationalization and justification of their own mistreatment. And it was in a one-on-one that they would begin to confess to each other, “I went on three dates with this man and I am scared of him. He should not be around other women.” Another one finally was like, “I can no longer make propaganda encouraging women to join this movement because it hates them.”

And of course there was the woman who participated in white Sharia. I had heard that it takes many, many tries for a woman in a domestic violence situation to leave her partner, but I never understood it from the inside that way. Even just interviewing someone face to face, they’re going to be giving me a different sort of image, they’re putting up a front, but these raw texts between saying she loves this guy and then maybe he’s not capable of love, and then he’s treating her horribly, spitting on her in front of other people, and then back again. You see the degree to which people will over time believe that they deserve their mistreatment, believe that they’re stupid, believe that they deserve to be abused.

AA: Oh, that’s awful. But you have also mentioned a couple of women who got out, right? Who got out of it and are speaking out about it, and that’s really inspiring. Do you have any stories that you could share about that?

ER: Samantha Froelich, she’s the woman who had the phone. For most people, it’s not a big, immediate epiphany that they’re racists, or that they’re assholes. There’s something bad that happens to them that starts to be the beginning instigation, this nagging feeling that things aren’t right. And then they leave, and then over time they’re like, “Oh yeah, the Holocaust probably really did happen.” They lose the beliefs that they had adopted. Samantha was dating Elliot Kline, who was running Identity Evropa, a big part of the Charlottesville organization, and they broke up. She was afraid of him and she didn’t want to be around him anymore, and she kind of fled. She told me that she lived in a cabin in the woods for a while before moving in with some relatives. And I talked to this person for years now, and it has been a slow process in gradually letting go of those beliefs. And also I felt like letting go of a lot of internalized misogyny, just in the way she would speak to me. As a woman journalist, my perspective in interviewing these women, often I get the projected misogyny, I get the projected self-hate. It comes to me and it can be really unsettling. Yeah, so Samantha has been speaking out. Some have left quietly, some have just gone quietly without saying explicitly that they’re against this stuff, but they’re no longer active.

AA: Yeah. Well, that’s heartening to know that that happens too. And it strikes me too, you talked about how in domestic violence situations it often takes years sometimes and multiple attempts to get out, and that just means that maybe your body’s safe, but the deprogramming of the mind can take years. Your entire lifetime, honestly. That can be so hard to extract when it’s become so internalized in your psyche, in your emotions, in your habits of thinking, right? And the way you see the world, it just can be so, so, so hard to deconstruct inside. But it can be done. It can be done.

Well, as we’re nearing the end of our discussion time, I want to shift to one last subject. I know you were in Portland and Seattle in the summer of 2020. You were kind of everywhere. It’s amazing, Elle, and at all of these really important moments. My sister lived in Portland at the time, and she said it was terrifying. And I know for a lot of people, what they saw that summer was footage of riots and street brawls, but I’m curious because it kind of depended where you got your news what you were seeing, and that’s been a theme for the last few years, too. Americans are getting vastly different pictures of what’s going on. As someone who was there personally, what’s your perspective on that summer of 2020 specifically, and maybe in Portland?

ER: Yeah, with the two different kinds of news, we’d be taking an Uber to a protest site where I knew that I would be seeing mostly kids who had just come to this, you know, that summer, and the woman who was driving the Uber was telling us all about how her husband was watching all these YouTube videos about Antifa training camps and how they were coming in bands to cities to attack people. And that just wasn’t true. But I did find that early in June, there were very violent clashes between police and protesters, and many of the people who joined the protests had not been expecting that and were kind of traumatized by that. And that really bonded them together, not always in a healthy way, in my opinion. They hadn’t been anarchists or super leftists before then, but over time this groupthink came, took over to where they really would kit out in full on protective gear, bulletproof vests, helmets, reinforced gloves. And there were many people who didn’t want to participate in acts of violence or direct protesting and they would be medics. So that gave them some protection from police violence but they still got to be there, and I felt like some were almost addicted to it. I’m not saying that to disparage what they’re protesting for, which when I was talking to them was largely police reform and systemic racism.

But a real groupthink did take over. And they also had these online networks where they’d be chatting with each other and they’d feel this immense trust in each other, but they didn’t actually know each other. Anyone could make essentially a flyer for a poster. You put an image, you say the date and the time and one of the little slogans and it would get forwarded around like crazy and then people would all show up and sometimes they’d be angry at it. Like, “Who’s leading this?” And it wasn’t clear who actually organized it. I was accused of collaborating with some organizers that other organizers didn’t like, just out of nowhere on Twitter. I was like, “No, I don’t know them.” There was this paranoia. There was a group in Portland and they were just tweeting constantly about it. And I would ask people like, “Is this group of kids? They’re purportedly teenagers. Are they legit?” And people will be like, “Oh yeah, they’re really legit. They’re really legit.” I’m like, “Have you ever met them?” “No.” “Do you know anyone who has?” “No.” “Do you know what they look like?” “No, I have no idea.” They could have been anyone.

AA: Ghosts.

ER: Yeah. Likewise, there was a woman involved in the online protesting around the CHAZ in Seattle, the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, and it started as a meme and then it became a real thing, this small area where cops weren’t in. And at first it was like a fun little party, but there were constant rumors that Proud Boys were coming. So some antifascists started securing the perimeter, openly carrying assault rifles, like AR-15s and stuff. And then it created this paranoia and over time it stopped being a fun party and the violence escalated until two kids stole a car and were driving into the area and someone allegedly mistook them for right wingers and shot them and killed one of them. And they were actually just unarmed Black teenagers. So it took a month to replicate the thing they were protesting. I did go back there, I mean, there are people who are sort of grappling with that reality. Anyway, it’s just a lesson in the bad things that social media can do. It’s not committed to the right wing. And the right wing gets a lot more of the focus, but it is completely value neutral and moral neutral. And any group of activists are vulnerable to this kind of groupthink and infiltration by bad actors and ghosts and people you have no idea if they’re real or not.

AA: Yeah, that’s really important. I’m really glad you mentioned that. Maybe the last question I’d like to ask you, we’re ending all of our episodes this season with action items and specific things that people can do to deconstruct patriarchy and racism and these oppressive systems, maybe in our own communities starting with where we are, and things that people can really do. Based on your journalism and the things that you’ve been studying and in writing this book, what would you say are some action items that you’d like to leave with listeners?

ER: Run for school board. I mean, being up in very evangelical Tennessee, that’s where it all began. That’s where the evangelical group started building their base of power politically. Even a white nationalist had said to me that the misogyny of the alt-right was unfortunate because women were often better at getting what white nationalists wanted. Now, he’s talking favorably about segregation, anti-busing policies, et cetera, but I think the lesson is an interesting one, which is that when women are working on behalf of their children, they are very highly motivated to take concrete action to do good things. I definitely would say do not cut off the people in your family who are believing things that you think are extreme or off the deep end, because it doesn’t work, it doesn’t change their mind. You have to engage with them in a way that respects their intelligence. Even if you think they’re believing something really, really stupid. It just does not work to say that it’s stupid. It just doesn’t. So you have to be willing to engage in long, slow conversations. In talking to extremists, I was often able to kind of crack some of their ideas after hours and hours of conversations, but I can’t do that at scale. People want to take care of their own family. Those are two of the big ones.

AA: I love that you said both of those. The school board, that means like really truly in your community and that feels small, but if you scale it, that grassroots impact can be huge. And likewise, the other one too, I’m so interested to hear you say that. Because as you know, in this moment, especially right now, there’s a lot of debate about whether it’s better to, in the name of accountability, cut people off and draw a really hard line. “I will not tolerate this in my life” versus being willing to keep engaging in hopes that there will be a change of hearts and minds. And I tend to agree with you, Elle, and also based on my own experience, as I said, having grown up in an ideology where I was taught and I absorbed messages that then later I realized like, “Oh, no, I don’t believe that anymore.” But I was able to make changes in my own life, in my own mind and heart, because people were patient with me and people didn’t give up on me, and people didn’t write me off. And I do know that anytime someone, for example, I come from the Mormon tradition and when I would encounter people who would make me feel like they thought I was stupid or they thought I was a bigot, all it would make me want to do is just dig my heels in harder and defend, right? So having been on the other side, it does make me think that actually I believe we have to play the long game and see the humanity in people, if only because strategically, that’s what I have seen work.

do not cut off the people in your family who are believing things that you think are extreme or off the deep end, because it doesn’t work, it doesn’t change their mind.

ER: It’s easier said. Even for me, this is difficult. I can sit and listen to a stranger say all kinds of stuff to me for hours. This is the skill I bring to my work. In real life it is so much harder for me to hear it from someone close to me because it makes it so much more real. If it’s gotten close to me, I have a hard time controlling my emotions and not just getting angry. I was hanging out with people over the holidays who were voicing some anti-vax stuff and I felt myself wanting to have a big confrontation that would feel good in the moment, but it doesn’t work. You can try doing charts and statistics and stuff, but in the digital age, anyone can have access to that and they’ll be able to find something to prove their side. I found that in arguing more in terms of logic and common sense, I got a lot further.

AA: Okay, that’s good. I was going to ask you what you did do, and what are some of your tactics and strategies in those conversations that you’ve seen crack people open? You’re saying not going to data because anyone can find data that supports their opinion.

ER: I mean, I can give a few examples. They’re not like grand slams or something or someone suddenly becoming reasonable, but with one white nationalist, he was saying all this misogynist shit to me about how I was like bad and a woman, et cetera, going on and on about my voice that I was like doing a voice. And I was like, “Wait, wait, no, I am a woman. I have a higher voice than you. I have a woman’s voice. It is higher. That’s just how it is.” And that was one moment where he was like, “Oh, yeah. Okay. I guess that’s true.”

AA: Wow.

ER: Another time, and I apologize for this example, but they were talking about supposedly white people evolving to be smarter. They believed it’s because we had winter in Europe and had to plan for the winter.

AA: Oh, I’ve heard of this. They had to work harder and be more innovative, yeah, I’ve heard this.

ER: Long-term planning, all that stuff. I’m like, okay, well, language was invented in what’s now Iraq. It’s pretty hot there. They think of themselves as so scientific, and I’m like, Africa is an enormous continent. Why would every single person who had origins there be the same? It doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t work that way for animals, why would that be for people? Just things like that.

AA: Even engaging in a conversation like that, I can just feel my blood pressure rising. You just want to be like, “You’re a racist asshole.” It’s good actually that you’re describing this because I’m feeling so furious hearing it and thinking of engaging with a person who has those beliefs is actually really hard. As much as I’m like, “Yeah, engage with them, have an open heart, that’s the way you’ll reach them,” that’s rough, actually, if they’re saying stuff that is that bad.

ER: It’s been anti-Semitism that has been one of the hardest ones. I don’t think I’ve ever actually made much headway on that. I’m just like, “Have you ever met any Jews?” They’re like, “No.” “Okay, well, it’s just not what you think it’s like. It’s just not that big a deal. I don’t know how else to explain it to you.” It’s difficult because for some of them, for example, they say all these terrible things about women being bad at math. Let’s use that example. I would be talking to this white nationalist, and I’d be like, “Well, I’m really good at math. I’ve actually always been good at math, spatial reasoning skills, I have an amazing throwing arm,” and some will kind of listen, but he would be like, “How can you not understand the difference between group averages and individual cases?” He’s really interesting, that’s Chris Cantwell, he was later known as the Crying Nazi. He went to jail for several years over an extortion case, the details are kind of darkly amusing, but I won’t get into it. But he was in a place where the media he consumed and the amount he was able to talk to the rest of the world was very tightly controlled. And he went on this podcast and he said that once you’re in there, you can’t consume racist propaganda every single day, and you start to realize how limited your worldview is, and that there’s other stuff going on. And I talked to him about it, and he’s like, “Yeah, I just started to realize that race being the only thing, that’s boring. It’s just the same stuff over and over again.”

AA: Wow, that’s really interesting. I think as I’m hearing you talk, it’s really striking me how important it is sometimes, even if you’re not going to ever change the person’s heart and mind and they don’t have the experience of going to jail so they have their media restricted, we don’t have control ultimately over whether someone changes, but we do have control over who we want to be in life. And maintaining our own integrity and saying, “That’s not true,” or phrasing it in a way that might have the highest chance of positive impact and saying, “You might want to read this book or take a look at this YouTube video or this podcast as a different point of view,” but saying something. But then sometimes not getting sucked into long, pointless conversations that drain our energy and actually aren’t going to make any difference. I don’t know. That’s just maybe something that we can feel out as we go. It’ll be different for different people.

But wow, good for you for fighting the good fight, Elle. And having conversations in really, really difficult and sometimes dangerous circumstances. I admire your work so, so much and I have learned so much even just from this conversation. It’s been really, really great. Again, Elle Reeve, thank you so much for being here. I enjoyed this conversation and admire your work tremendously. And for listeners, again, Elle’s book is Black Pill: How I Witnessed the Darkest Corners of the Internet Come to Life, Poison Society, and Capture American Politics. Thank you for this book. And really quick, can you tell us where people can find your work, maybe on social media or other places?

ER: Sure. I’m on Twitter and Blue Sky. If you just search Elle Reeve, I’m the one that pops up. And I’m on CNN.

AA: Awesome. Thank you so much for being here. This has been just awesome. Thank you, Elle.

ER: Thanks for having me.

They wanted to be that alpha male.

What better way to display that to the other men than by dominating a woman?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!