On this episode we feature two different women on the topic of redefining our relationships.

Dr. Jennifer Finlayson-Fife who talks to us about selfhood, sexuality, and faith, delving deep into her research about how women are taught (or not taught) about their powerful capacity for pleasure in patriarchal societies.

Monette Chilson, who educates us about the divine feminine

and the goddess Sophia, exploring how we relate to the ideal

of sacredness, and what words that we use when

we discuss divinity.

Our Guests

Dr. Jennifer

Finlayson-Fife

Dr. Jennifer Finlayson-Fife (she/her) is a relationship and sexuality educator and coach, as well as a licensed clinical professional counselor in Illinois with a PhD in Counseling Psychology from Boston College. She is a frequent contributor on the subjects of sexuality, relationships, and spirituality to blogs, magazines, and podcasts, and she maintains a private coaching and counseling practice in Chicago, where she lives with her husband and three children. She is an active member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

Monette

Chilson

Monette Chilson (she/her) is a writer, creatrix and excavator of our sacred feminine lineage. She leads WomanSpirit Reclamation from the ancient mountains of North Carolina. She enjoys reading, yoga and travel.

PART ONE.

Let’s Talk About Sex

Dr. Jennifer Finlayson Fife

I think a lot about sex…although maybe not in the way that some people do. In particular, I think a lot about why people like and don’t like to have sex, what ignites desire, and what suffocates it. As a therapist I meet with people almost daily who are trying to figure out why they don’t like to have sex, why their spouse doesn’t like to have sex, or why their spouse does like to have it. It’s an elusive question sometimes, as well as a painful one for many couples. My dissertation research focused on the question of LDS women’s sexual agency, that is LDS women’s capacity to be actors in the sexual realm, to act on their own behalf in a context of sexual conservatism and patriarchy. While some LDS women thrived in my research, most of the women were undermined in their relationship to their own sexuality as they’d internalized a message that eroticism and desire are unfeminine and risky to their desirability, a trait essential to femininity. According to radical feminism —which was a primary framework in my research — patriarchies oppress women through gender role ideology, that is notions of proper female comportment undermine women’s relationship to their sexuality and to themselves. For example, in patriarchy men are constructed as naturally dominant, assertive, strong, and inherently sexual, while women are constructed as nurturing, selfless, deferential, and virtuous. That is to say women are taught that they are naturally less sexual than men, inherently lacking hedonistic desire and even morally superior to the supposed depravity of male sexuality. While superficially approving of women’s nature, this cultural prescription leaves women little room to legitimately experience express or integrate their own eroticism. To be feminine is to suppress or disconnect from sexual desire, or feel ashamed of its presence.

…women are taught that they are naturally less sexual than men, inherently lacking hedonistic desire and even morally superior to the supposed depravity of male sexuality. While superficially approving of women’s nature, this cultural prescription leaves women little room to legitimately experience express or integrate their own eroticism.

This suppression of sexual desire and knowledge, theorized by The Radical Feminist Critique, aligned with the experiences of most LDS women in my research. It also fits with much of my LDS clientele. In my experience many, if not most, LDS women struggle premaritally and in marriage to integrate a sense of legitimate sexuality and desire. Many women are naïve about their own capacity for pleasure, and allow themselves little room to explore and take ownership of this part of themselves even when their husbands are encouraging and openly long for more sexual connection. This sexual immaturity can, of course, cause deep frustration with a higher desire marital partner, but a bigger problem in my mind is that it represents a fractured relationship with oneself; an unwillingness to be in a mature relationship with one’s own body, one’s own sexuality, and an important source of strength. While many LDS women struggle to claim and integrate their sexuality because of the cultural invalidation of female eroticism, other LDS women know their capacity for pleasure and may even know what they long for sexually, but nonetheless lack desire for their souse. What I want to talk about is the issue of women’s selfhood — also deeply affected by patriarchy — as an additional factor in sexual desire.

According to author and clinician Dr. David Schnarch, selfhood is a stronger determinant in sexual desire than biological drive, for men and women. In Schnarch’s thinking, it doesn’t matter how much physical desire we feel if we believe the act of wanting another person or having sex with them will diminish us in some way, we won’t let ourselves want. Or, conversely, if we believe having sex or wanting will add to our sense of self, we will desire. For example, it’s easy to desire when we’re dating because, in addition to the libido increasing factors of novelty and uncertainty that are inherent to an early relationship, we also perceive that merger with the other will add to our sense of self; the validation of our beloved’s reciprocated desire makes us feel more whole, more significant, so we’ll want. In marriage, however, sexual merger with a higher desire spouse can quickly make us feel like we’re losing ourselves through having sex, like one is capitulating to the desires and expectations of the other, folding into their reality and affirming them at our own expense. It isn’t exciting.

Many women are naïve about their own capacity for pleasure, and allow themselves little room to explore

A man is no more willing to lose himself in chronic accommodation of his wife’s sexual desire than a woman is to a man. This is why some men prefer objectified forms of sex, such as pornography, over sexual intimacy with their spouse; there’s less vulnerability, less perceived loss of self. That said, LDS women — in a context of patriarchy and robust gender role ideology — in my experience are more likely to feel like the partner with less power in the marriage. Many Mormon women have not only less economic and social power relative to their husbands (who function as providers and leaders) they are also more likely to feel pressured to forsake their desires to comply with what others want from them. This is part of women’s prescribed goodness in church cultural thinking, her “inherent feminine selflessness.” As elder Richard G Scott said in reference to the many sacrifices that wives and mothers make for their husbands and children, “you do all these things willingly, because you are a woman.”

While this accommodating role may give women status for being what is expected and may offer some security through pleasing those around them, women cannot earn through systematic deference to the desires of others a robust sense of self. Deferring to others’ wishes in order to fend off criticism or scrutiny is not an act of generosity or strength, it is instead a reflection of one’s inability to validate her own legitimacy and it breeds resentment and stabilizes immaturity in marriage. At a minimum, plenty of women in this position have sex with their higher desire spouse. They are dutiful and accommodate, but they are not passionate. It’s very difficult to make love to, open your heart up to, or desire someone whom you believe is above you or stronger than you, or that you perceive takes from you because you are unwilling to challenge them. Feeling like one exists for someone else’s pleasure seldom inspires women to explore or discover their own eroticism and desire. It’s too costly.

If I come to discover or expose this part of myself, will I then be more obligated to you sexually?

Will I be even more possessed by you because now I’ll no longer have the excuse of a non-existent sex drive to fend you off?

And if I reveal this part of myself, doesn’t it just validate you as the stronger more able one? The one who always knew I was sexually immature or repressed?

Many women in the face of these questions would rather hold a sense of self by stripping themselves of their relationship to their sexuality, a very costly act of defiance to the loss of self that patriarchy demands. As much as many marriages have modernized in the church and function in more egalitarian ways relative to a generation ago, I’m still struck by how much the dynamic of inequality persists in many LDS marriages. While immaturity in marriage and the challenges to selfhood that marriage evokes are not problems specific to Latter-Day Saints, the institutionalized support for glorified under-functioning in women is indeed a cultural problem of our own. We need to stop acting like real strength in women undermines marriages and mothering. We need to stop embracing impotence in women as a kind of goodness, much in the way that we regard children as good, innocent, powerless, and harmless. We stri[ women of their strength and autonomy in the gender narrative and then ask men to take care of them. This may create an ethic of dependency and deference in women and, therefore, potentially less overt conflict in marriages, however, it does not — in my experience — create strong people, strong families, or passionate stable marriages.

You can learn more about Dr. Finlayson-Fife and her services by visiting her website.

PART TWO.

Sophia Rising

Monette Chilson

She is the light that shines forth from everlasting light,

the flawless mirror of the dynamism of God

and the perfect image of the Holy One’s goodness.

Though alone of Her kind, She can do all things;

though unchanging, She renews all things;

generation after generation She enters into holy souls

and makes them friends of God and prophets,

for God loves the one

who finds a home in Wisdom [Sophia].

She is more beautiful than the sun

and more magnificent than all the stars in the sky.

When compared with daylight,

She excels in every way,

for the day always gives way to night,

but Wisdom [Sophia] never gives way to evil.

She stretches forth Her power

form one end of the earth to the other

and gently puts all things in their proper place.

(Wisdom of Solomon 7:26-8:1, The Inclusive Bible)

I would have stopped doodling mermaids and fallen off the worn oak pew in awed wonder had someone read me these verses when I was a child, growing up in a Southern Baptist Church, in my small South Texas town. Especially so if they had invoked the name of Sophia (Greek for Wisdom). Desperate to see myself reflected in my religion, I longed for someone to look beneath the patriarchal doctrine and dogma and show me that I was a part of the grand epic woven in the pages of the Bible. Someone to assure me that God wasn’t the exclusively masculine being described from every pulpit I’d encountered in my young life.

I stumbled through my formative years, grasping at the good in my faith tradition, while grappling with the parts that didn’t make sense to me. I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was missing. I just didn’t know where to find it. Often, I found myself going back to the same dry well, looking for water. I faithfully played the part of Mary every year in the church Christmas pageant, joined Girls in Action (like Baptist Girl Scouts), memorized famous women missionaries and studied their lives, looking for clues to what inspired their faith. My freshman year in college, I frequented the Baptist Student Union, and even got baptized again thinking maybe this time it would take. I know now that doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results is the definition of insanity. But this was the only way I knew to live back then. I was searching for the spiritual essence of my faith, but I kept coming up empty-handed—or worse, disillusioned and dejected.

Luckily, Goddess’s ways are always more expansive than mine. I was slowly drawn along a path that makes sense in retrospect, one that honored some inner wisdom regarding my physical and spiritual self. I was the oddball that asked for a juicer for Christmas one year in high school. Then I stopped eating meat after writing a paper on vegetarianism my sophomore year in college. I was always intrigued by yoga and finally began practicing a few years out of school. Through this progression, I learned to be true to myself—the person Goddess was calling me to be—even when it went against the grain of my Southern upbringing.

I didn’t know that my yoga practice would be the antidote to the unrest I felt with my religious life. I had no idea the missing piece of practical spiritual wisdom I’d been seeking would appear as I sat on a mat in an incense-filled room listening to unfamiliar words chanted in Eastern tongues. How strange it felt to have finally found my spiritual home while simultaneously fearing that I was betraying my faith tradition.

…I longed for someone to look beneath the patriarchal doctrine and dogma and show me that I was a part of the grand epic woven in the pages of the Bible. Someone to assure me that God wasn’t the exclusively masculine being described from every pulpit…

There on my mat, I felt a sacred presence that had eluded me for years. Goddess flowed into me on my breath, moved through my limbs and settled into my heart center at the end of my practice. Suddenly God was free to be God, or rather I was freed to experience God without the inferences of maleness—as Goddess. She’d been waiting for me inside myself all along—an inner wisdom with which to flow, rather than a God “up there” who required me to sacrifice my own sacred knowing. It took me a while to recognize divinity in this new guise. There were no robes, crosses or religious icons to tip me off. I could see myself reflected in this new divine vision.

While today I intuitively interpret that feeling as Goddess at work in me, back then I didn’t know what to make of it. I knew it felt spiritual, but I had no way to explain this newfound spirituality or to integrate it into my religious beliefs. For a while, it worked because I had put religion on hold during my post-college twenty-something years. I simply buried my fears about yoga being contrary to the Christianity of my youth that I had temporarily disavowed. My yogic spirituality sustained me, while I pointedly avoided organized religion. When my husband and I became parents and decided to go back to church in our thirties, I began the process of reconciling the two.

Goddess flowed into me on my breath, moved through my limbs and settled into my heart center at the end of my practice. Suddenly God was free to be God, or rather I was freed to experience God without the inferences of maleness…

First, I tried making my yoga Christian. I thought it quite clever to find Bible verses to accompany my favorite poses. For example, I used Psalm 45:3-4, “Strap your sword to your side, warrior! Accept praise! Accept due honor! Ride majestically! Ride triumphantly! Ride on the side of truth! Ride for the righteous meek!” (The Message) to sanctify warrior pose. I had corresponding verses for bow pose, child’s pose, mountain pose and others. I convinced myself that if I read Bible verses with my poses, they would be redeemed. That my faith and my practice would become one. I was bridging the chasm with holy words.

I developed and taught a class using this approach. We opened by meditating to a folksy version of the classic Christian hymn Be Thou My Vision and ended by listening to my friend Robbie Seay’s Breathe Peace in savasana (still a favorite of mine). In between, we did yoga poses to a litany of Bible verses I had carefully chosen as the soundtrack to our practice. While this Christianized yoga was a valuable steppingstone for me, it ultimately felt contrived—like I was trying to make both yoga and Christianity something they weren’t. I had yet to realize that attempting to bridge a perceived chasm created an unnecessary duality. The two weren’t as spiritually incompatible as I had been led to believe. I was living proof that they could, indeed, coexist.

I knew that the sacred source I encountered on my yoga mat was not male. In fact, it felt distinctly feminine to me. Was it because I was finally seeing myself mirrored in Her? Or was there, legitimately, a female side of God that existed in my faith tradition? How could this have been overlooked or ignored by so many? And why did I find her here in my yoga practice instead of in church? Did I dare to explore this unorthodox view I was beginning to espouse?

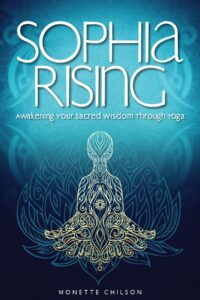

It was these questions that ultimately set in motion the research that culminated in writing my first book, Sophia Rising: Awakening Your Sacred Wisdom Through Yoga. It was this quest that led me to Sophia and enabled me to practice both yoga and Christianity without internal conflict or angst. And it was the continuation of this quest that led me to realize that my vision of the divine is too big for any religious container. To understand that to me—for now—the language I use for divinity is Goddess. I discovered I could leave formal religion behind and hold onto the sacred self that I had excavated.

I now believe that there are as many paths to Spirit as there are humans on this earth. Because Sophia was divinity in female form that sprang from the particular religious tradition that I was wrestling with, Sophia was the key to my spiritual reconciliation. Her role in your journey may be significant, peripheral or non-existent. I am not here to evangelize—a practice that assumes the evangelizer has the answer for another—but merely to suggest you consider that all of our conceptualizations of the divine were formed within the patriarchal worldview into which we were born.

Greek for wisdom, Sophia surfaces repeatedly in both the Christian and Hebrew* scriptures, yet her identity remains unclear, making her all the more compelling to me. Some see Sophia as a deity in her own right, others see her as representing the Bride of Christ (Revelation 19), others as a feminine aspect of God representing wisdom (Proverbs 8 and 9), and still others as a theological concept regarding the wisdom of God. Sophia, by her very nature, defies definition, allowing us to revel in the mystery that surrounds her.

*The Jewish faith would, obviously, use the Hebrew translation of Wisdom rather than the Greek word Sophia. Because of its nuances, you might find Wisdom expressed as khokhma (wisdom) חכמה, bina (understanding) בינה, da’at (knowledge) דעת or tvuna (another word for understanding) תבונה.

Sophia is not someone women dreamed up to feel better about being left out of all the starring roles in the Bible. The truth is, we weren’t left out. Sophia was there all along, beckoning—right along with Jesus. And it’s not just women who were short-changed in the masculinization of God. Many men, too, long to be able to experience God holistically, to acknowledge and rest in the feminine side of God.

Most people will pay lip service to the fact that God transcends gender, but my experience—because of the stigma associated with the feminine divine in Western religions—does not include prayers, images, or words that express this truth. Whether the aversion to referring to God in feminine terms stems from patriarchal roots, a desire by early Christians to separate themselves from Goddess worship or to differentiate themselves from Gnostic communities, the result has been a severing of the sacred feminine that has silenced voices that would pray to God our Mother. Sophia embodies those missing pieces, giving me the prayers, images, and words that complete my limited human perspective on divinity.

When I sit in a church pew (regardless of the religion), I am surrounded by others’ perceptions of God (rarely Goddess), both visual and spoken. When I sit on my yoga mat, I am carving out space for my own spiritual life to coalesce. Creating an inner sanctuary and opening myself up to a divine presence untainted and unfiltered by religious precepts. Yoga doesn’t create the sacred. It merely reveals it in many beautiful ways.

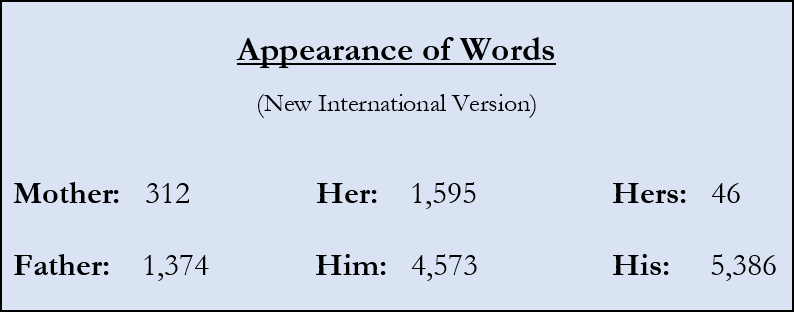

For years, I tried to live out my faith in a Christian tradition in which even the most enlightened churches are built on a foundational text which was translated by men for a society which validated men’s roles. Women’s roles have been relegated to the sidebars of history, to the margins of the Biblical stories. I say that not to diminish the sacredness of the Bible, but to put its journey from God’s unblemished wellspring of wisdom into the book that sits in church pews today into perspective. This assertion may sound subjective, but let’s look at a simple linguistic analysis of the Bible’s New International Version, often cited as the most popular translation.

More than seventy-five percent of all references to parental roles are paternal, rather than maternal. Similarly, in a broader context, the male pronoun “him” is used nearly three times as often as its female counterpart “her.” In the most staggering contrast, when the concept of possession is brought into the picture, “hers” is used a mere forty-six times in the entire Bible. This includes forms of the word like “herself,” while “his”—the equivalent male possessive form and its variations—is used 5,386 times. Linguistically speaking, more than ninety-nine percent of the Bible’s ownership is rooted in masculine language, thus in masculine imagery. For every one time we read about something being “hers” in the Bible, we will read 117 references to “his” possessions, “his” attributes, “his” desires—in essence, to “his” story (also known as “history”). How much more difficult does that language make it for women to own their own faith?

I discovered I could leave formal religion behind and hold onto the sacred self that I had excavated. I now believe that there are as many paths to Spirit as there are humans on this earth.

It made it impossible for me to own mine. The truth is that when the language, the rituals, the divinity, and the authority are all exclusively masculine, there is no room for a woman like me. No room for a woman more interested in plumbing her soul’s depths than fitting herself into the patriarchal version of Godly womanhood.

Finding Sophia was a bridge for me. She carried me across the vast sea of the patriarchal view of divinity I grew up with to the ground on which my spirituality is planted today. On this rich soil of Mother Earth upon which I now stand, I listen to my body, heeding her wisdom. I trust my knowing above any outside teaching. I welcome all the goddesses to visit me, giving life to their stories so long repressed. I listen to them. They are my sisters, and they remind me of the goddess within me, countering the creation story that blames women for the downfall of humanity.

It once seemed ironic that I should find my soul’s rest in yoga, a practice outside of my understanding of sacred. Today I trust holiness wherever I find it—on my mat, yes, but also in the woods, in a book, or by a roaring fire. In Gerda Lerner’s words, “I have the the supreme hubris which asserts to itself the right to reorder the world. The hubris of the god-makers, the hubris of the male system-builders.”

I am not longer constrained by patriarchy’s limited understanding of divinity, history, literature, philosophy, psychology, or any other field which systematically excluded female thought and leadership for most of its existence. I am crafting words, images and practices that align with the divinity within me. That is my birthright, and I am claiming it unapologetically.

You can learn more about Monette Chilson at her website, or join her for a workshop by visiting Sovereign Sisterhood.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!