“it’s really a staple in our culture today to honor the women in our families”

Amy is joined by Meleseini Lotoaniu for Part 1 of their discussion about the history of gender constructs in Tonga.

Our Guest

Meleseini Lotoaniu

Meleseini Lotoaniu is a third-year student at University of California, Davis with an interest in literature and writing.

The Discussion

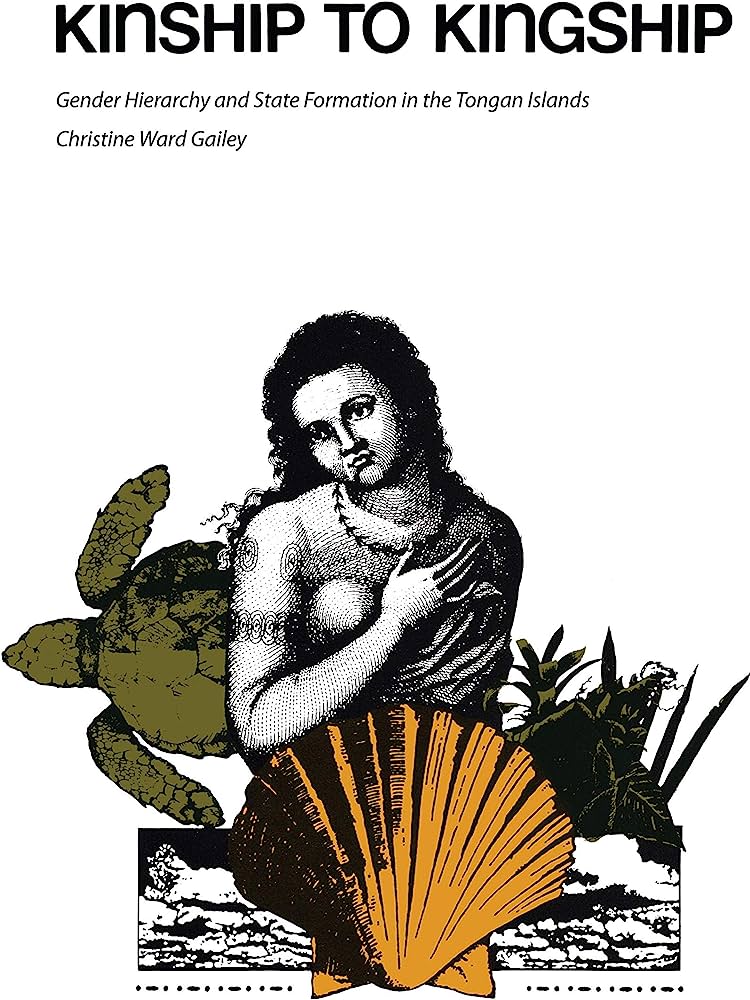

Amy Allebest: Today I was talking with my friend Malia, whom listeners will remember from past episodes of the podcast. And we were talking about important family events like funerals, and she mentioned how beautiful it was to see her Tongan side of the family where her aunt had presided as the fahu, or the oldest sister in the family. And she mentioned that at these funerals or other family events that the family members of lower status than the fahu would kneel on the ground beside her. And they had these beautiful, traditional, finely woven mats over their heads. And I was so excited as she was talking because I actually knew what she was talking about because I had just read the book called From Kinship to Kingship: Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands by Christine Ward Gailey.

And I also found it fascinating as I was talking with Malia, that she said that every time there’s a family event like a funeral, there’s this big family discussion of “should we do it the Tongan way or the church way?” And the church way means that they do it the white, European-American way, and she felt so sad that her relatives were placed in this position of having to choose between their cultural heritage and their faith. So I was really struck by this conversation because the book that I had read covered Tonga from its earliest settlement through the 19th century. But Malia was experiencing the very themes of that Tongan history in her real life today.

So, I’m really excited to talk about Tonga, to talk about Tongan history, and to talk about the resonances that still impact life in Tonga and in the diaspora. And my guest today also relates to this story on an intellectual level as well as a personal level. I’m so happy to welcome Meleseini Lotoaniu to our episode today. Hi Meleseini!

Meleseini Lotoaniu: Hi, Amy, I’m so happy to be here.

AA: So happy to have you here. I’m wondering if you could start us off by telling us a little bit about yourself.

ML: Yeah, sure. So, my family and I reside in the Bay Area where there is a prominent Tongan population in the diaspora over there. I have a younger sister who just started at UC Riverside, but I am the first in my family to attend an American four-year university. I attend UC Davis, I am an English major. And growing up I went with my dad a lot to the public library, so I’ve always been exposed to books and literature growing up and I think that early exposure really helped me to figure out what I want do in life. It made me wonder if I could be a writer in the future, or something. I read so many novels and works especially about other ethnic cultures and lifestyles written by people of color. And I remember not seeing a lot about Pacific Islanders, about Tongan people, so I’ve always thought maybe I could be that voice. Maybe I could be that writer that could write Pacific Islander focused stories. And I would love to share those stories. I’ve heard a lot of stories about people in my culture, so I would love to be that voice and be that person that other Pacific Islanders in schools could grow up reading.

AA: Well, I hope you’ll be willing to share some of those stories with us today on the episode, Meleseini. And as someone also who has read your writing, I am really excited to see what you contribute to the literature of Pacific Islander stories. I’m just thrilled to hear that about your goals.

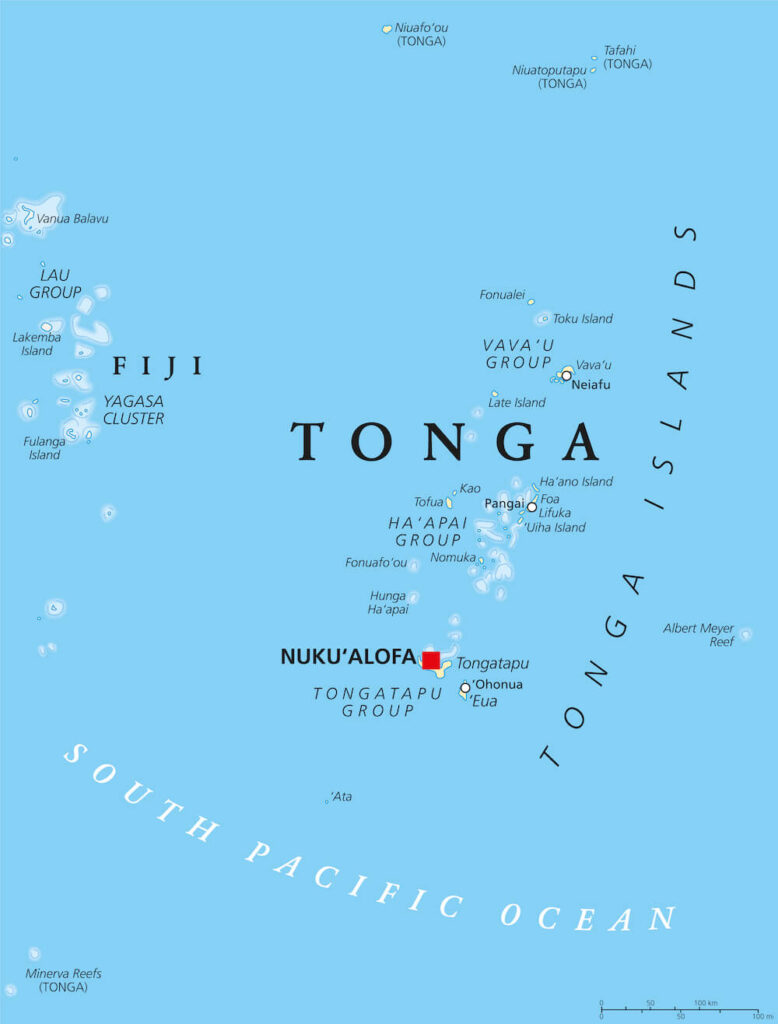

ML: Yeah, growing up I heard a lot of stories from my families and my relatives. A little bit more about my family, my mother grew up on the main island of Tonga. It’s called Tongatapu. She grew up in a village called Kolofo’ou, and this is where my grandmother was from, my mother’s mother. And my mother’s father grew up in one of the outer islands of Tonga, in one of the other island groups, which I guess you could say is like our “provinces” for an island nation of Tonga that’s made up of so many other little islands. My grandfather is from an island there called Ha’apai and then my father actually is not from the main island, he’s from another island group called the Vava’u group. He was born and raised in the capital Neiafu but he grew up attending boarding school in the main island of Tongatapu, and he also ended up living there and that’s how he met my mother. And they immigrated separately to America in the early 2000s, and they got married and they began our family here.

AA: Wow. And so have you been back to Tonga very many times, Meleseini?

ML: I’ve been to Tonga only a few times in my life. I wish I could have gone more. It’s just one of the things, it’s just very expensive to fly all the way out there. It’s a lot of connecting flights and it’s just so remote, you know, it takes a lot of transportation really to get all the way over there. But I went once as a baby, and that first time it was just with my mother. Just so she could tour me around to our other family members and to our other relatives too. And so I met other relatives that have unfortunately passed on already, but I hear stories about them growing up, too. I’m just happy that I met them as a baby. The second time I went, I think I was in elementary school and that was probably the longest amount of time I spent there. I basically spent my whole summer of third grade in Tonga. And so I got to see how it was to live as a child in Tonga and the typical island life. I remember running around my grandparents’ house chasing the dogs. And another thing in Tonga that you get to do, my favorite thing to do in Tonga was to ride on the back boots of the trucks.

AA: Whoa.

ML: Yeah, that was really fun. I remember the wind in my hair and everything passing by. Everyone in Tonga– and it’s such a small nation, everyone knows everybody. So I remember riding in the back of the truck and waving to all the people that I had met or waving to my other relatives that I had met on that trip. So that was a really fun memory. And then the last time I went, I think it was in my sophomore year of high school. And so that’s my most recent trip back to Tonga. And back then it was like coming back to my childhood. And I remember my previous trip when I went as an elementary school kid, and now going back as a high school student, now going back fully grown, I got to experience Tonga in a new way. I understood the culture more and I got to meet more of my relatives and learn more about them. And so, yeah, all my trips to Tonga have been so wonderful and so exciting for me. I would love to go back and relive those memories that I had when I was younger.

AA: Mm, that’s beautiful. Thanks for sharing that. So, let’s dive into the history of Tonga! We did so much research and we learned so much that we decided to break up into two episodes, today being Part 1. And Meleseini, maybe you can start us off by telling us about the Kingdom of Tonga today.

ML: The Kingdom of Tonga today is the only kingdom in the Pacific because it was never directly colonized by a foreign power. The Tongan monarchy has been retained for a long time, since the ancient times. Tonga was never directly colonized by a foreign power though it did become a British protectorate in 1900 and then it became a member of the Commonwealth in 1970. It still is a member of the Commonwealth, so it wasn’t directly colonized but definitely has had colonial and Western influences. More about the monarchy, the king today is King Tupou VI. In Tonga, there is a significant nobility class. Each village has a noble and there are also talking chiefs for major events that speak for those people of higher class. Many of the islands in Tonga are uninhabited, but most of the islands that people live on are broken into main island groups.

The major religion in Tonga is Christianity, and religion is a huge part of Tonga, really. It’s one of its defining qualities. One thing in Tonga is it strictly observes the Sabbath. So on Sundays, all the shops, all the workplaces, banks, really any public convenience spots are closed for the day. Except for churches on Sundays, you know, you’re supposed to go to church and there are a bunch of serious rules to follow, like no loud music. I’m not even sure if Tonga allows flights to come in on Sundays too, so I guess the airports are closed as well. Because it’s really supposed to be a day of rest and a day to go to church and just unwind and dedicate the whole day to God.

AA: Perfect. Thanks, Meleseini. So, let’s go back to the beginnings of what we know about gender dynamics in Tonga. And we’re going to start from the very beginning and just work through the history, mainly focusing on patriarchal constructs. And most of the information, as I mentioned, comes from the book that we read called From Kinship to Kingship: Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands by Christine Ward Gailey. Do you want to talk about some of the very earliest things that we know about in Tonga?

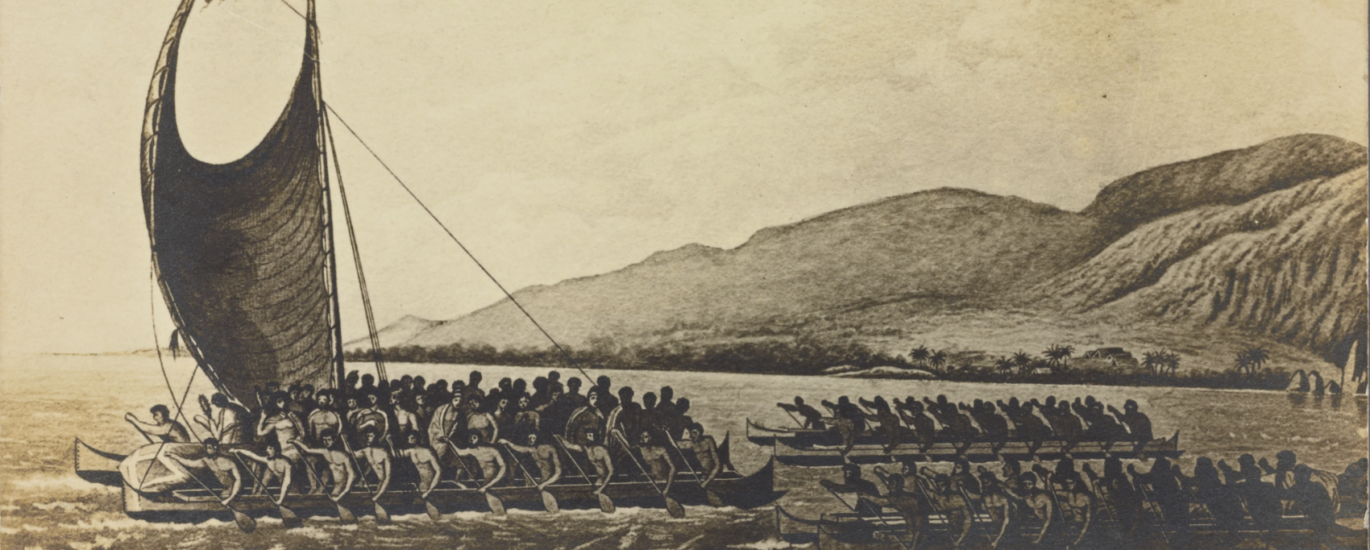

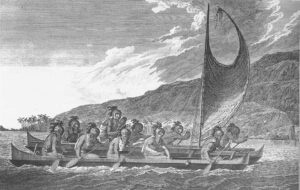

ML: What is known about Tonga before European contact, comes from myths, stories, songs, and poems that were handed down orally from generation to generation. There was no writing system, so anthropologists rely on this oral history for information as well as on archeological excavations. But what we do know, that in around 900 BCE, the Lapita people came from Papua New Guinea. They went exploring in their boats and they reached Tonga. And so the Lapita people made a specific kind of pottery that helps archeologists trace them in different places.

The Lapita people then traveled over in small wooden boats over open ocean to invisible destinations, and archeologists wonder what might have compelled them to embark on these missions where it was so likely that they would die before reaching their destination or getting back home. One hypothesis is that Lapitan culture encouraged immigration by younger sons. But not just in Tonga but throughout the South Pacific, there was a tradition of passing down lands to eldest sons. To obtain their own land, younger sons needed to explore. And according to Tongan tradition, the chief Tongan god, Tangaloa, was a younger sibling who created Tonga while searching for land from a canoe. His fish hook accidentally caught on a rock on the ocean floor, and he was able to pull Tonga to the surface.

If the hypothesis is correct, then there must have been some strong sibling rivalry to make someone take a boat to places as far away as New Zealand, Hawai’i, and Rapa Nui, which today is known as Easter Island. But that’s what they did. There are people in New Zealand, Hawai’i, and Rapa Nui that have similar languages and similar traditions, and they all trace ancestry to a few original settlers in Tonga. The main time during which Tongan younger brothers were sailing away to other islands was between 700 BCE to 400 CE, and that time is known as the Polynesian Era.

AA: That’s so interesting. One thing I thought when I learned that too is that that’s what happened with the Vikings. The Vikings had a tradition of handing down land just to the eldest son and so the younger sons, in order to get land, got in boats and went and found their own land. So that must be kind of a common human driving force, behind those seafaring people going to other places. I thought that was interesting.

So, there were a couple of mysteries from history that I thought were really interesting in this part of the book. One was that by 400 BCE, people in Tonga had stopped producing that pottery that you talked about, Meleseini, from the Lapita people that was so distinctive. And at first when I read that, I thought, okay, that’s interesting they stopped making pottery, but why does that matter? And then I realized that pottery was the only human-made thing that lasted until now. So if there’s no pottery, then archeologists are left without any clues about the civilization during that period that they were no longer making pottery, there’s nothing to find. And so that was really interesting. No one knows why they stopped making pottery, they must have just used naturally occurring dishes like coconut shells after that. But nothing can be said with certainty except that the same disappearance of that pottery also occurred in Fiji and Samoa. So if anybody listening wants to solve that mystery, that’d be great!

And then another mystery was something called the “Long Pause”. And that was when after generations of sailing and exploring, people in Polynesia stopped leaving their islands. They stopped sailing. And for close to 2,000 years they didn’t sail anymore. But then suddenly they started sailing again. And that’s the setting of the movie Moana!

the chief Tongan god, Tangaloa, was a younger sibling who created Tonga while searching for land from a canoe. His fish hook accidentally caught on a rock on the ocean floor, and he was able to pull Tonga to the surface.

ML: Yeah, yeah!

AA: That was so cool. Did you know that already, Meleseini?

ML: It’s really interesting that that’s the setting of the movie Moana. It actually makes me happy, too, because I guess the producers of Disney really did their research. And that really represented our stories of Polynesia really well. Going back to the timeline, by around 1200 CE Tongans were sailing again and they created a rich oral tradition of voyaging. And some important facts about their government and social structure, the Tu’i Tonga is a line of Tongan kings which originated in the 10th century. And the story of that is that the creator of the universe was named Tangaloa and he was the father and the chief of all the other gods. And he had a son named ʻAhoʻeitu and his sons became the Tu’i Tongas. And so that line of the Tu’i Tonga ended with the last Tonga in 1865, but the all-male line still follows a system where only descendants of Tonga’s first king can ascend to the throne. And male successors are given preference over female successors. But there was Queen Sālote Tupou III who reigned from 1918 to 1965 and she has been Tonga’s only queen so far. And an interesting fact about her is that she granted women the right to vote in 1950, which is really groundbreaking.

AA: And it makes me wonder how long women would’ve had to go without the right to vote if there hadn’t been a queen. It’s just really interesting that there was one female leader and thank goodness she chose to do it. But I don’t know if a male leader ever would do it, you know? Interesting.

ML: Ancient Tonga was patrilineal, which means they traced descent from father to son. And ancient Tonga was also patrilocal, which means that when a couple married, the women went to live with the husband’s family, which I would also say is still relatable in modern times in Tonga today. Husbands outranked wives and chiefly men were also polygynous, which means they had multiple wives, though non-chiefly people were monogamous.

AA: Yes, isn’t that interesting too? And typical. Yeah, I’m at the top and I think I’m going to allow myself to have many wives, but that’s not a privilege for everybody. Yeah, that’s pretty common. So those are some of the male-centered or androcentric features of the culture. But at the same time, there were a lot of matrifocal elements as well, and here are some examples of those. In the royal family, the daughter of the Tu’i Tonga, and like Meleseini just explained, the Tu’i Tonga was what they called the king. So the daughter of the king was called the Tamahā, and she was the highest ranking person in all of Tonga. Now that didn’t mean that she could make laws, it’s unclear to me actually what she could do. I was kind of looking through the book like, that is so cool that she had the highest rank… What could she do? Yeah, she couldn’t really make laws, but she had that status of being the most important person in the whole society. And while maleness was superior to femaleness, like husbands did outrank wives, it was a really complex system of who had status over whom. Because older was always superior to younger, and sisterhood was always superior to brotherhood.

This is really different from a Western concept of status. I had to sit with it for a minute. I feel like in American culture that I was raised in, the rank you are, or especially like in other countries where there’s a very fixed caste system, in Tonga there were no equal statuses. Everybody’s rank was relative to whomever they were with at the time. And so my rank in relation to my husband is that I’m lower than him, but my rank with my brother, even though he’s a guy, my rank is higher than him because I’m an older sister. There’s just this web of rank. And this is really interesting, a higher ranking person had the right to the labor and products of a lower ranking person. And we’re gonna talk about that in just a minute.

But yeah, it was very complex and those first two chapters were hard for me to understand to be honest, because it was so complicated. But one other fact that I thought was interesting because it gave me a great visual, was that in a Tongan canoe there’s a male side and a female side. And the male side was considered superior to the female side of the canoe. But the high ranking females, I’m assuming like the older sisters or maybe the chiefly females, sat on the male side of the canoe. So it’s a patriarchy, but it’s complicated. That’s the takeaway! So Meleseini, I think one of the most prevalent features, and this is what we opened the episode with today, was Malia talking about the fahu system. So Meleseini, I would love you to explain what the fahu means.

ML: Yes. One of my favorite things about Tongan culture is the fahu system. Your fahu is your father’s oldest sister. And so your father’s oldest sister is called the fahu, and your fahu is technically supposed to be the most important person in regards to you in the family. Fahus, your father’s older sisters, have the highest rank in your family, meaning that she always must be treated with honor and respect all the time. Your fahu has so many duties over the family. Sometimes, she can arrange your marriages or name your first child, or sometimes she can adopt children from her brother’s side.

AA: So I’m the oldest sister in my family, so I would preside over my brother and his wife. And then would all of us preside over him? Or just the oldest one? Sisters have precedence over all brothers, right?

ML: Yeah, but technically the eldest sister is supposed to be like the main fahu. But his other sisters could also preside over him too. But the eldest sister is the most important one.

AA: Okay. Well my poor brother, he has four sisters, haha. I was just thinking, okay so in my family my husband doesn’t have any sisters. Right? Or no.

ML: Oh, yes yes yes. Technically since your husband doesn’t have any sisters, your children wouldn’t have a fahu technically. They wouldn’t have a fahu who’s their father’s sisters. But if your children’s father has female paternal cousins, they could also be considered fahu to your children. Since in traditional Tongan culture, cousins are considered your siblings, there’s not even a word for cousin in Tonga because you would describe your cousins as your brother or sister.

AA: That is so interesting! Well I would be lucky because his paternal first cousins are really cool. I would be totally fine letting Jessica and Tara and Holland and Kelly be my bosses, so that’s great. And being the fahus for my kids! Oh, I didn’t know that. That’s really cool.

Okay, so again, it’s like this complex interplay of rank, right? Because at the same time, even though I would be fahu in my nephew’s lives, like my brother’s kids, my husband would still outrank me. And so that’s really interesting. I wonder how that would feel for girls to go from having high status in childhood, knowing like, “I’m a sister, I have status.” But then when they get married, they have lower status than their husbands. And especially if they’re plural wives, because we talked about how some of the chiefs had many wives. I wonder if that would be hard to, like, you would almost feel like you lost rank as you got older in some circumstances, but I don’t know. But some of the things that we thought were interesting, the ways that sisters presided over their brother’s families were really interesting to me.

ML: Yes. So, the fahu is the father’s eldest sister, but if your father has multiple sisters, the other sisters would be called the Mehikitanga. And so the other Mehikitanga could also arrange and veto their brother’s children’s marriages.

AA: So, I or any of my three sisters could arrange the marriages of our brother’s kids. Or if our brother and his wife were like, “we want our son to marry this person” we could be like, “eh no, we veto.” Right? That’s a lot of power. And I think that’s really interesting because I was remembering from The Creation of Patriarchy, Gerda Lerner said that one of the most powerful controls in a society is the power to decide who marries whom. And that’s a big feature of patriarchal societies is that men always arrange the marriages. And in the fahu system, it sounds like women could not be as easily used as pawns in marriage contracts to increase the men’s power, like by forming alliances with other men. There’s checks and balances against that.

ML: I would say women were a lot more involved with the arranged marriage. If there were any arranged marriages in the village, in the families.

Fahus, your father’s older sisters, have the highest rank in your family, meaning that she always must be treated with honor and respect all the time.

AA: Yeah, that’s so interesting. And I’m just going to read a couple of things from the book that talk more about what power the fahu has. The fahu could curse her brother’s wife or wives with infertility. She could adopt her brother’s kids if she wanted to. She could command the labor and products of her brother’s spouses. So like, “I want that food” then they have to give it to me, or “I want a blanket”, they have to give it to me if I’m the fahu. So the fahu system was, again, a successful counterbalance to all the patrifocal parts of the culture. A son who was set to inherit his father’s status and his father’s title could be challenged by his sister. But at the same time, a wife, again, was supposed to defer to her husband no matter how high her personal rank was or whether she outranked her husband, like if she was from a chiefly family, she would still be presided over by a husband. And it was even said that “The husband was fahu to the wife.” And this again, I should point out, this is all pre-Christian Tongan culture. So this is a long time ago, so it may have evolved since then.

ML: Yeah. In modern life, the fahu system is still a pretty big staple in Tongan culture. At the end of the day, it all comes down to love and respect between all the family members. And also uphold the culture because it’s really a staple in our culture today to honor the women in our families.

AA: Yeah. That’s so beautiful, I love that. So the next thing we wanted to share in the pre-European Tongan culture is the division of labor before Europeans arrived. So one interesting thing that’s different from my lived and observed experience in my life is that it was a person’s rank that was the primary dimension of the division of labor. And again, rank was determined by a lot of things, age and place in the family. So it wasn’t just men do this and women do this. And another thing that was interesting is that all specializations were part-time. So if you cooked, if that was your specialization, or if you farmed the yams, which was a really important crop, if you were a fishing person, if you were a builder. All of those specializations were part-time in your daily life. And one quote from the book said that “everybody knew how to cook and everybody knew how to till the ground to a tolerable degree.” I thought, wow, that’s so practical and important, right? That everybody could be self-sustaining and keep themselves alive if they needed to, of all genders.

Another interesting thing was that there was what was called the Tu’a class, which Europeans would’ve translated as peasants. That was kind of the lower class in the society. Their jobs were fishing and horticulture and craft production. Like crafts that you would just use for practical purposes. And in times of war, the Tu’a men, so again the peasants, they would fight, that was their job. If there was a war, then the men would fight. But sometimes women went along to care for their husbands or brothers, or the women would guard the war canoes when they weren’t being used. And there’s a record of one war that listed 5,000 men who were fighting and 1,000 women who were also fighting. So it wasn’t unheard of for women to fight as well.

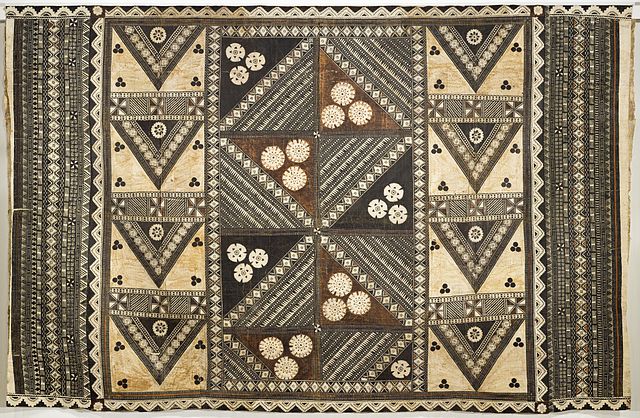

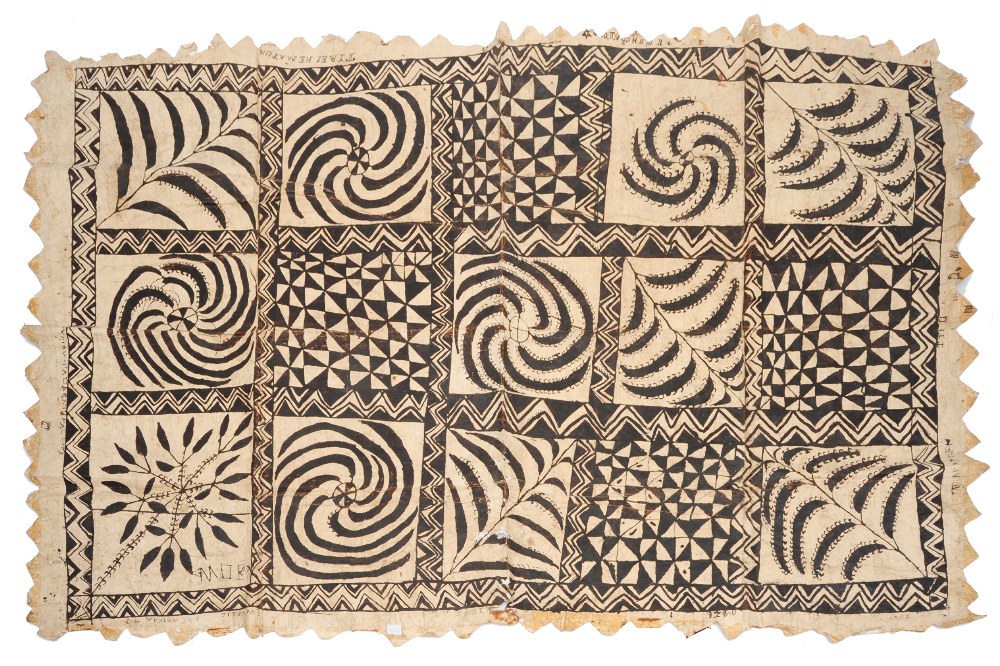

Another feature was that men of the chiefly caste didn’t work. So I thought that was again, like humans must just be like that. They get to the top of the chain and they’re like, “I think I want a lot of women, and I think I don’t want to work.” That, again, must be just a human thing. But this was one of the coolest things that I thought that I learned in this book, is that women’s jobs, especially of the chiefly caste, was that they made ceremonial and meaningful objects, and these were called the koloa, these objects. These were valuables. And the way the book stated it was that “All things made by women were considered koloa.”

ML: Yeah the word koloa now it’s used to describe the gifts that you would give, the Tongan gifts that you would give to people. Usually the koloa, well now it refers to blankets and mats that you would give to families and people you’re respecting. Or people you’re celebrating.

AA: Oh, that’s so beautiful! Wow, that is really beautiful.

ML: Yeah, that’s what it means nowadays.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to love and respect between all the family members.

AA: Okay. Well then, the way the book described it was that “All things made by women were considered koloa. Valuables, wealth objects. So in birth ceremonies, the newborn actually was called koloa. Koloa were always superior to things made by men. Men’s objects and women’s objects formed separate and unequal spheres.” So things made by women were sacred. Things made by men, products that were made by men were considered just work. They were considered non-chiefly. And the peasant class, so the Tu’a men did all the cooking, that was a task that lower class men would do. It had low status partly because food was so plentiful on the islands, it wasn’t hard to get food. So it was like, oh, that’s easy, that kind of has low status to do that. So non-chiefly men did virtually all the farming, all the deep-sea fishing and they also did the canoe making. Men crafted all the weapons as well. And men of that lower caste of the Tu’a were supposed to carry water and collect firewood, which are two activities associated in most of anthropological literature with women. I thought that was interesting. It was the men who were carrying water and collecting wood. And then childcare was assumed by both men and women.

ML: The Tu’a class, back then it referred to the peasant like the low class, nowadays Tu’a means outside. So it’s interesting to see how it’s evolved to mean outside, and it’s interesting to see the origins of where the word Tu’a came from since back then it meant the people who were always doing the outside work. It seems like fishing, and horticulture, and craft production. But now it means generally being outside.

AA: Woah! So the highest value objects in all of society were of course made by women, and they were these finely braided mats, which were worn around the waist. The most valuable of these mats were the ones that were old and that were made by an elderly Tamahā, because like we said at the beginning, the Tamahā was the highest ranking person in all of society. And because age had higher rank than youth, and a crafted object had higher rank than a natural object, and an object made by a woman had higher rank than an object made by a man, all of those things infused each object with the rank of the person who made it. And so the highest ranking object was infused by these elderly high-ranking women. And these heirloom mats that were made by the elderly Tamahā are considered national treasures, equivalent in value to what the crown jewels would be in England. And in fact, one time a British official in the 20th century made a statement that Tongans had no history, and Queen Sālote replied, “Our history is not written in books but in our mats.” So we’ll provide photographs of these beautiful works of art on our website so you can see them.

Just a couple more facts about gender roles and divisions of labor. Some specializations were open to both genders, so doctors could be men or women. And healing expertise passed from parent to child, whether men or women, they would just pass it on to their kids. This was really interesting too. Midwifery, so delivering babies obviously, was distinguished from other forms of medicine. Midwives received valuable objects or koloa for their services.

So that’s really highly valued in the culture. And a colonial administrator remarked one time in the late 19th century, he said “Nearly all the old women are medical practitioners. Heavy fees are paid for their services.” And this skill was hereditary and it was passed down from mother to daughter, but if the midwife didn’t have a daughter then she would train her son to do that job.

ML: Wow.

AA: Which I thought was super interesting and cool. And that actually brings us to the end of our episode today. We’ve covered thousands of years of history, honestly all of which was entirely new to me. So I’m really grateful for this opportunity to learn all of this. And then in our next episode, we’ll pick back up at the point when European boats landed on the Tongan islands. Thank you so much for being here, Meleseini, I can’t wait to talk more with you next week!

ML: Thank you so much!

The Lapita people traveled in small wooden boats over open ocean to invisible destinations,

and archeologists wonder what might have compelled them

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!