“Every once in a while – even if you think that your male buddies are going to make fun of you – stick up for the woman.”

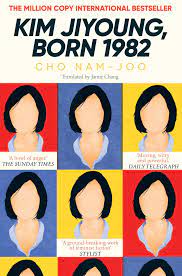

Amy is joined by translator Jaime Chang to discuss the novel Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo and explore the stories of contemporary Korean women.

Our Guest

Jamie Chang

Jamie Chang is an award-winning translator and teaches at the Ewha Womans University in Seoul, South Korea.

The Discussion

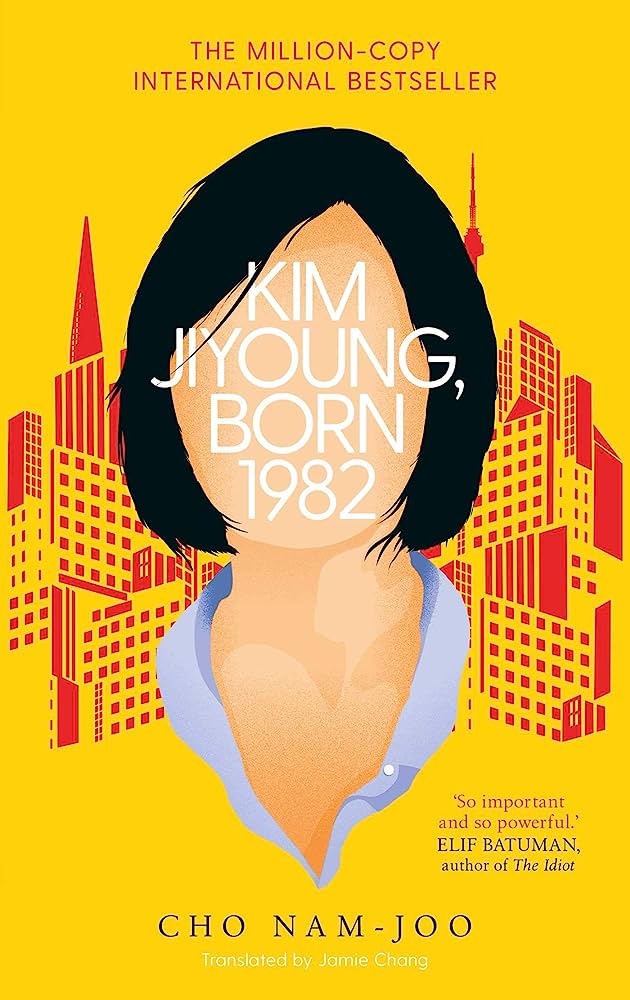

Amy McPhie Allebest: In October, 2016, South Korean script writer Cho Nam-Joo published her first novel called Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982, based largely on the author’s own life. The book sold 1 million copies within the first two years and was read by political leaders, including then-President Moon Jae-in. Numerous K-pop stars also embraced the book, and Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 was credited with influencing a feminist movement in South Korea. One passage from the book reads:

“Kim Jiyoung is a girl born to a mother whose in-laws wanted a boy. Kim Jiyoung is a sister made to share a room while her brother gets one of his own. Kim Jiyoung is a daughter whose father blames her when she is harassed late at night. Kim Jiyoung is a model employee who gets overlooked for promotion. Kim Jiyoung is a wife who gives up her career and independence for a life of domesticity. Kim Jiyoung has started acting strangely. Kim Jiyoung is depressed. Kim Jiyoung is mad. Kim Jiyoung is her own woman. Kim Jiyoung is every woman.”

I am so glad I discovered this novel and I highly, highly recommend it to readers. And to discuss it today, I’m so excited to welcome to the podcast the books translator, Jamie Chang. Hi, Jamie!

Jamie Chang: Hello, Amy! Thank you so much for having me. It’s good to be here.

AA: I’m super excited to have this conversation. I enjoyed this book so much, and particularly I noticed as I was reading it how phenomenal the translation was.

JC: Aw, thank you.

AA: I would never have guessed that it wasn’t written in English, honestly, as a non-Korean speaker. It was fluid and relatable and absolutely wonderful. I’m really excited to dig into this, but first before we dive into the book, I’d love to have you introduce yourself to listeners. Tell a little bit about where you’re from, what your story is, and what brought you to do the work you do, including how you became the translator of this book.

JC: I was born in Seoul, also in 1982. I think that was part of the reason why the Korean publisher, Minumsa, asked me to translate this book. And there was a small part of me that felt reluctant because I thought maybe this will hit a little too close to home. Maybe this will open my eyes to things that I don’t really want to see. Because you know how there are certain books in your life that are so eye-opening that you can’t unread them, that it kind of changes your life, that changes your perspective. I had this premonition that this was going to be one of those books and I wanted to avoid it. And I was right!

But anyway, I was born in 1982. I was raised in a family that moved around and my upbringing was very different from Kim Jiyoung’s upbringing. And I think that was maybe good and bad as a translator because part of me was able to see Kim Jiyoung’s life through fresh eyes because her experience was so different from mine. And then there was another small part of me that had to really work to understand some aspects of Kim Jiyoung’s thinking. For instance, her need to conform or her need to be, I guess, a “nice girl” or a model student, a good daughter and so forth. But anyway I went to nine schools across three countries between K-12. So unlike Kim Jiyoung, I didn’t really have a community that I needed to fit into. And I think I ended up becoming a translator because interpreting and translating came very naturally to me due to my parents who moved around a lot and they weren’t able to speak the local language all the time. So I sometimes had to interpret for them. From an early age I had kind of like a translating mechanism just working constantly in my head. So it came very naturally to me and I think I started translating right out of college because I thought, okay, this is my skill set. Are you familiar with the musical Avenue Q, by the way?

AA: Yeah, yeah.

JC: You know that song “What Do You Do With a B.A. in English?”

AA: Hahaha! I do, yes.

JC: Yes, that was me.

AA: I do have a BA in English.

JC: Yeah, me too, yay! I was a double major in English and Drama, so two very, very useful degrees that will prepare me for the world. So I thought, I have this skill set, I can read and write and in two languages. What is the best way to use the skill set to pay off my massive student loans as quickly as possible? That was sort of, you know, my goal, I want to pay off my student loans. That was it, that was my driving force in life. So that’s how I ended up translating.

Because of my upbringing, I can’t say that I’m able to speak for the average Korean heterosexual woman because I’m not a heterosexual woman. And I was also raised as an only child, like Kim Jiyoung has a sister and a brother. The brother is the youngest and sort of like the treasured child of the family. But I was raised an only child in a family where you were able to be sort of discreetly and passively sexist and racist and all these things but, you know, saying things overtly was frowned upon. So I didn’t encounter a lot of discrimination based on my gender growing up, but I can tell you what I have been able to observe in my time here. I’ve been living in Korea for the last seven years and I did go to middle school in Korea.

AA: One other thing I wanted to ask you about before we talk about the book itself is the impact that the book had when it was published. I mentioned at the beginning of the episode that celebrities were reading it, the president himself read it, apparently. But I know it was controversial as well. Could you talk about the book’s reception a little bit?

JC: I think even the writer herself did not expect this book to make such a huge impact, because she felt like she wasn’t telling a story that would be particularly surprising to anyone because everybody lived through this. Every Korean woman knows that this was their reality. So she herself was very surprised that the books did really well. It certainly helped, the South Korean president read this book. And because it was publicized so much in Korea at a time when digital feminism was on the rise, I think because this book was publicized so much, it ended up getting a lot of backlash from the more conservative male reader, sometimes the more conservative female readers. They would say, this is not the experience of every woman in Korea. Not every woman is this docile, they would say. But I would say the most lasting impact of this book was that it paved the way for a very big wave of feminist-minded literature in Korea as well as queer literature in Korea. So this book that she wasn’t sure was going to get published changed the course of literary history. I think it was a combination of the press, the attention, the controversy, and of course, good writing.

AA: Fantastic. And it probably just opened up conversations, whether it was people who hated it or loved it or anything in between. Maybe it got people talking in a new way. Wonderful, let’s dive into the book. I wanted to focus on some ways that Kim Jiyoung represents a kind of Korean every-woman. Maybe we’ll organize the conversation chronologically, like through a woman’s life, because that’s kind of how the story is told in the book, right? She starts out as a child and it goes through her life.

I wrote down some questions for you and you can elaborate on the book itself or your own life and your observations of women that you know. So we’ll start with conception. One of the most striking themes, I guess, that I picked up from the book is this pressure to have boys. So I wanted to ask you, is that something that you still observe in Korean society?

JC: I don’t know how things have changed, if things have changed in the last decade, but I have an acquaintance who’s around my age, who when she was pregnant, she has three daughters. And when she was pregnant with her third daughter, she found out that it was going to be a girl, and then she started telling her friends, “we’re having a girl!” People did not even hesitate to tell her, “I know a good doctor who can perform an abortion.” Because at that time, 10 years ago, abortion was illegal in Korea.

AA: Wow.

JC: So, you know, I know somebody who can take care of that for you if you want. It certainly, I think to this day, creates friction with the in-laws if you as a woman are not able to give your husband a son. Not that anyone needs heirs anymore…

AA: It’s just like this relic from the past, right?

JC: Mm-hmm. And oh, it also has to do with family rites. R-I-T-E-S. So when somebody dies, they have this thing called “chief mourner”. Sangju. Literally translated it means the owner of the grief or something. Sangju has to be a man. So if someone died and did not leave any male heirs, like no sons, a male cousin would step in.

AA: Oh, wow.

JC: As opposed to the eldest daughter.

she found out that it was going to be a girl, and then she started telling her friends, “we’re having a girl!” People did not even hesitate to tell her, “I know a good doctor who can perform an abortion.”

AA: And that’s a really important role in the family?

JC: Mm-hmm.

AA: Oh, interesting.

JC: And also it’s up to the male descendant to perform the family memorial rites every year. I’m probably going to end up talking about my wife’s family a lot on this podcast. I have her permission, I did get her permission.

AA: Wonderful!

JC: I think she would be a better point of reference because she was also born somewhere around 1980 and she actually, unlike me, did not leave the country until she was 29. So she has that continuous exposure to one culture, one language. But my wife is the middle daughter of three girls. And when her younger sister was born her father was so disappointed that he didn’t even come to the hospital to see her. I mean, that’s fairly common in Korea. But the thing is, 25 years later, we went down to the city hall to get some family registry documents issued, and then we discovered a fourth name on the family registry. So, my wife discovered that she had an extra sibling that she did not know about. So she called her mom, she asked, and she said, after your younger sister was born, your father had an extramarital affair and sired a child hoping to have a son. And guess what? It happened to be another girl. So, he didn’t raise her, the woman raised her. But because of the hoju system, if you didn’t have a male guardian you weren’t able to belong to any family registry. So if you’re a single mother, you can’t put your child on your family registry. So that’s how the fourth daughter, the fourth secret daughter, ended up on my wife’s family’s family registry.

AA: Wow.

JC: That’s how we found out about her.

AA: That’s tragic.

JC: It is tragic.

AA: That’s really hard.

JC: But because of the pressure to have boys, there was a time in Korea when sex-elective abortion was a big problem. To this day, it is illegal in Korea for the doctor to let the expectant mothers know outright the sex of the baby before week 32.

AA: For that reason?

JC: Mm-hmm.

AA: Wow. Oh my goodness.

JC: Sometimes they will hint at things like if you really beg, they’ll say “you should buy blue clothes.”

AA: Wow.

JC: Yeah. But they can’t tell them outright.

AA: But they can’t tell them. The next stage of life that I wanted to ask about is childhood. So the gender dynamics between brothers and sisters and sons and daughters in a family. And some that stood out to me from the book were that parents would give the best food to the boys in the family, to the sons. Boys getting their own bedrooms and girls had to share. And then there’s a quote that I wrote down that said “People believed it was up to the sons to bring honor and prosperity to the family, and that the family’s wealth and happiness hinged upon male success. The daughters gladly supported the male siblings.”

That was interesting in terms of the structure of the family, but the word “gladly” really stood out to me too, that the daughters were happy to support the system. And I wanted to see if you wanted to dig into that a little bit also.

JC: Just because you’re wearing a smile on your face doesn’t mean you are not dead inside.

AA: Haha, yeah.

JC: I’m sure they resented it a lot. And I don’t know anyone in my generation, but maybe 10 years older than me who actually had to give up on school and university and having the career they want so they could support their younger male siblings or older male siblings. So in the past, people would work at factories instead of going to universities or even high school in order to support the male siblings through high school and university and so on.

AA: One thing that came to my mind is just how I was as a kid. Well, how I still am as an adult, too. I love making people happy. I really, really like doing nice things for people. And I was also such a, kind of a pleaser. So I can see myself, if I were in that situation, really gladly supporting and being like, “no, no, no, let me do this for you. I’ll do this for you.” And then not realizing, like you said, that I was dead inside maybe in those ways until later. And feeling genuinely happy at the time, and then later going like, oh my gosh, I’m so angry. And I guess this is what happens with Kim Jiyoung, right? She gets to a point in her life where suddenly she’s having a mental breakdown and doesn’t even know why, because of all of these little drops into the bucket one at a time all through her life.

JC: But would you have been willing to give up your college education for a male sibling?

AA: Maybe…

JC: If your parents told you outright– Actually this is an episode that comes up in one of the more recent Kim Jiyoung stories. So the female character has just one sibling, a male, and the mother tells her on the morning of her college entrance exam, “I don’t have tuition for you too.” And she gives her the seaweed soup. So I didn’t know that seaweed soup had that hidden meaning, but apparently in Korea, if you give seaweed soup to somebody who is about to go to an interview or a big test or something, that means you want them to fail. Because seaweed is slippery and you’re slipping.

AA: Oh, wow.

JC: It’s so mean, isn’t it?

AA: It’s so mean! Yeah, that’s terrible.

JC: But going back to that question, would you have been willing to give up your college education for a male sibling?

AA: I mean, I guess it depends on my surrounding culture, because if that’s what every other person, young woman my age was doing, just for me personally, if you’re asking me, I was at that age starting to wake up in certain ways and in other ways I was not awake yet. And I did just kind of go along on the conveyor belt of what everyone around me and my community was doing. I might not have noticed. Maybe I would have, I’d like to think maybe I would have, but sometimes if it’s really homogenous and you don’t see anyone rebelling against it or saying it could be different, sometimes you can’t even see it until it’s too late.

JC: It’s very brave but it’s also really exhausting sticking out like a sore thumb.

AA: Totally. And dangerous.

JC: Mm-hmm. Yes. You know, risk of being ostracized and attacked.

AA: And it’s just so painful for human beings to be ostracized and to be alone. One other part from childhood was boys bullying girls. And I was like, “Oh my gosh, I didn’t know this happened everywhere!” But it seems like it happens everywhere. Where boys would be really mean to girls and then adults would excuse that behavior because “it means he likes you”. That totally happened to me all the time. And I remember the first time one of my friend’s moms said that to me.

JC: Did you kick her?

AA: No! Because I didn’t know! Because I was like, ok, you’re an adult, I guess. But it felt scary. That’s what it felt to me. Scary. And so I did not know what to make of it.

JC: I think it sends the wrong message to little girls.

AA: Yes.

JC: That this is what love feels like, when somebody hits you. This is what love feels like.

AA: It’s really awful. But that happened several times in the book, I’m remembering. Where there’s violence, violence or just meanness. You know, meanness of boys and just doing annoying things. And the adults would just excuse it.

JC: When you heard the mom say that, “oh, he likes you.” Did you genuinely believe that the boy liked you?

AA: Here’s the thing, I think he did. And I think he was taught that that was the way– He didn’t know how to get attention.

JC: Literally hit on a girl.

AA: Yes! Exactly. I think sometimes boys do do that if they have a crush on a girl. Boys, all the way through high school. I had a boy who I remember one time we were coming up to each other in a hall and I didn’t know if he was going to say something nice, something sexual harass-y, or what he was going to do. And he just looked at me and then shoved me as hard as he could and I hit my head on the wall and then he kept walking. And I knew, all his friends told me like, “oh, he’s in love with you.”

JC: Oh, that’s horrible.

AA: Yeah, this happened to me a lot! All while I was growing up. So every time it came up in the book I was like, oh yep, I relate. And then people would just be like, “yeah, well, he likes you.” That’s what it looks like to have a crush, I guess. Anyway, it was quite validating for me to read this. But anyway, I also wanted to talk about gender roles in terms of housework and what boys and girls were expected to do in the home as they were growing up. Could you talk about that for a minute?

JC: One of the examples of how boys are spoiled rotten and how people make inappropriate remarks is there’s this very– like grandmothers like to say, if a little boy wanders into the kitchen looking for food or wanting to help or just, you know, bored, wanting to hang out with their mom, grandmothers will say, “if you go into the kitchen, your pepper will fall off.” Pepper as in penis. Can I say ‘penis’?

AA: Yes. Haha! Are you serious? Like, “stay out of the kitchen because that’s the women’s space”?

JC: Mm-hmm.

AA: Oh, that’s funny. I mean, not really funny, but kind of funny. Whoa.

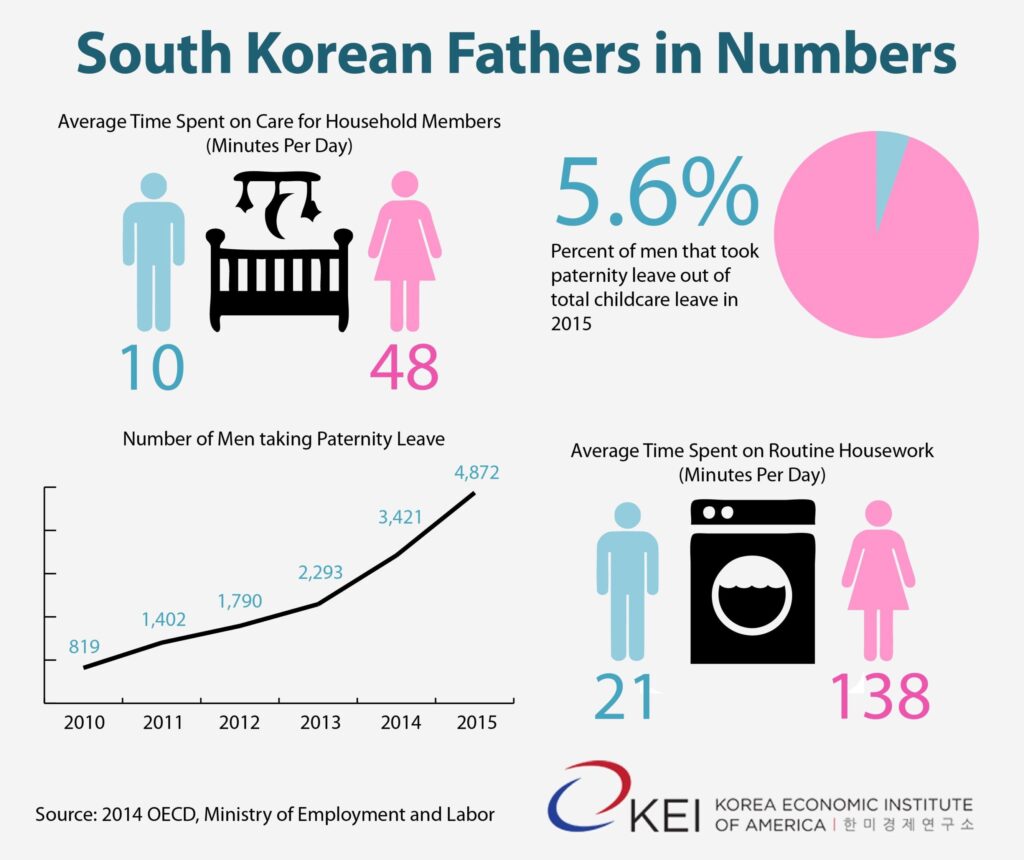

JC: But I don’t know how it is for boys who are growing up now, but this is a pretty common saying. Because of the grandparents’ influence, boys are still discouraged from learning how to cook and do laundry, do the dishes, and generally take care of themselves. But I think because of this culture, even today, a mother is considered very forward thinking and feminist if she forces her boys to vacuum, to take out the trash, and just generally help out around the house.

AA: Interesting.

JC: Which, once again, I think it’s a huge disservice to boys in general because how are you going to become a good partner if you don’t know how to do the laundry?

AA: Totally.

JC: Basic life skills.

AA: Basic life skills, I agree. Okay, let’s move on to the school context. There were some examples in the book of boys getting preferential treatment from teachers, and I wondered if you could talk about some examples of that from the book and from your own life that you noticed as you were growing up?

JC: Boys back then came first in the roster, so it was alphabetical but boys first and then later girls. I had completely blocked this out. And when I was translating this again, I thought, oh my goodness, you know, it all came flooding back. I thought, oh my goodness, this is true. This was true.

AA: There’s this policy in the book where the boys were first on the roster, which means their names were called to eat first, and so they would eat really fast and have the remainder of the time to play, and the girls had to eat after the boys, which cut into their time to play and they would get in trouble for being late, right?

JC: Mm-hmm.

AA: So it was like this thing on the roster wouldn’t matter, except that it did have a practical implication in that it cut the girls’ playtime shorter.

JC: I guess I was oblivious to it when I was in the system because that was such a norm. Boys came first on the roster. But when I think about it now, I think how strange. And also on the social security system, so the Korean social security number or citizen registration number is set up so that the first six digits is your birthday, and then there’s another, I think six or seven digits. And the first number of the second part indicates your sex. So 1 for men and 2 for women.

AA: Oh. Ew.

JC: Ew is right. But anyway, 1 for men, 2 for women. I didn’t really think about that until I read this book. And like I said, you know, it’s one of those books that once it opens your eyes to these things, you just cannot start seeing it everywhere and, you know, start remembering things from your childhood. I remember the thing that really bothered me more than anything else was hair regulations. So at my middle school, everybody had to have a bob. It was a bob for girls, short hair for guys. And they wanted the bob to be very short. So they actually, at the school gate, teachers would measure the hair. They would be holding a tape measure to measure the girl’s hair. They would pull the hair down behind the ear and see how far it came down the chin. And it had to be one centimeter. If it’s longer than one centimeter, some of the more scary teachers would cut your hair with a pair of scissors.

AA: Right there?

JC: On the spot.

AA: Wow, crazy.

JC: Yes. And I actually had a teacher who would go around the classroom with a dustpan and a tape measure and just do all the girls’ hair. And we’re like, oh, okay, this is spring. We don’t have to go to the hairdressers, we’ll just have her do our hair. You know, not everyone can pull off a bob. Also, girls weren’t allowed to have boy haircuts.

AA: Oh, interesting. Yeah, boy haircuts.

JC: Mm-hmm. You have to be unmistakably… girl. Even today, Seoul Pride was on the news at the hair salon where I was getting my hair cut. And the hairdresser started shaking her head and saying something very homophobic while cutting my hair and complaining about how short my hair is, like why I didn’t dye my hair. She’s like, “You’re going gray. You really ought to dye your hair.” And I said, “Why?” And she said, “It doesn’t look good.” I’m like, “Who do I have to look good for?”

AA: Wow.

JC: Anyway, I don’t think she knows that I’m gay. I don’t think she’s able to make that connection. But people comment on my hair all the time. The older people comment on my hair all the time. Cab drivers comment on my hair. And I’m like, come on, short-haired women have been around for a very long time. It’s not even like a gay rights thing, it’s just short-haired women.

AA: Yeah. Well that is interesting because I do feel like there must be a broader spectrum of what’s considered feminine where I live. Because my mom has short, short hair, but she wears makeup and she dresses extremely femininely. But in terms of just hair, I think there’s a broader spectrum of ways that you–

JC: My wife says it’s my caveman eyebrows.

AA: Oh, for heaven’s sake.

JC: She’s like, “You’ve got to do something about your eyebrows; you’re scaring them with your eyebrows.”

AA: Oh, that is so funny. That’s so interesting. That’s hard though. That’s hard, Jamie.

JC: But it doesn’t even have to be like that physically– Like, I don’t think I look very masculine. But when I was in middle school with the bob, with the school-sanctioned bob. I’ve always had this very loud laugh that carries across classrooms. And when I find something funny, it’s really difficult for me to stifle a laugh. So somebody would say something funny in class and I would just laugh. And I remember, I think I was in the eighth grade or something and this boy said, “Boys don’t like girls who laugh like that.”

AA: Oooh.

JC: And I thought, well, I don’t need boys.

AA: Yeah, good thing I don’t need boys to like me. But what a terrible thing to say.

JC: It wasn’t even considered such a terrible thing to say to another person. I mean, you know, they’re like “girls aren’t supposed to laugh like that… girls aren’t supposed to do this… girls are supposed to…” I don’t know, insert gender stereotype here.

AA: Well, just the presumption too, that your job is to be liked by boys. And so that would be the motivating thing that he would think to say, oh, you’re not going to want to do that because that’s not going to get you liked by boys. That’s a really interesting assumption to even start from, you know what I mean?

The next topic that I wanted to talk about is the sexual double standard. And there were lots of incidents of sexual misbehavior where then girls would get blamed when a man did something inappropriate or dangerous. So there was this incident with a flasher at school where a bunch of girls– I love that you’re laughing. But it was really sad though because the girls got in a lot of trouble and it was 100%, like they were not asking for it. They were actually victimized by this guy and then they got in trouble for it at school.

JC: Right. Because, you know, girls aren’t supposed to defend themselves or exact revenge on flashers. They’re just supposed to scream and run. And let the flashers be, because flashers will be flashers.

AA: That’s right. And then one of the scenes that we were just talking about, scenes that haunted us afterwards, and one of them for me was the incident with the almost sexual assault at night, right? She was on the bus.

JC: The boy who comes out, follows her off the bus and then comes after her, right?

AA: Exactly. And she’s terrified, like she knows she is in danger. All by herself at night with this young man. And I think she rebuffs him and he’s super angry and really abusive and horrible. But she goes home, tells her dad about it, and her dad just basically victim-blames her and shames her. Well, what were you wearing? What were you doing? Why were you alone at night? She got no support from her dad. And she really loved her dad, which was so awful. Her dad wasn’t a monster or anything, it just reflected the culture at the time.

Another one that stood out from this chapter that I really related to was when she overhears some guy friends of hers, she’s dating someone and she overhears these guy friends of hers saying that she is gum that someone spat out. That she’s been chewed up and spat out. Because she’s had some beginnings of sexual– or were they sleeping together? I don’t remember if they actually slept together.

girls aren’t supposed to defend themselves or exact revenge…They’re just supposed to scream and run.

JC: No, they were just dating.

AA: They were just dating. So she’s been used. And I was like, oh! I have literally heard that exact same metaphor. Oh yeah, yeah. That’s a common one in conservative American religion.

JC: Really?

AA: Oh yeah. There’s all these metaphors, like you’re the cupcake that somebody else licked. So who would want that cupcake? You are the flower that somebody else tore all the petals off and mauled it and so it’s all wilted. Who would want that flower? Boys, would you want to chew a piece of gum that someone else has chewed? The metaphors go on and on. That’s one I grew up with.

JC: Why food?

AA: Yeah, that’s true, that’s funny. There’s also a board, like a board that someone hammered nails in. And you can pull the nails out, but the board will never be the same. Yeah, that’s very common in America. There was a mention in an article about the book that maybe the author didn’t know whether it would be relatable to women outside of Korea or whether it would be very Korean specific. And it was very relatable to me, like even specific phrases.

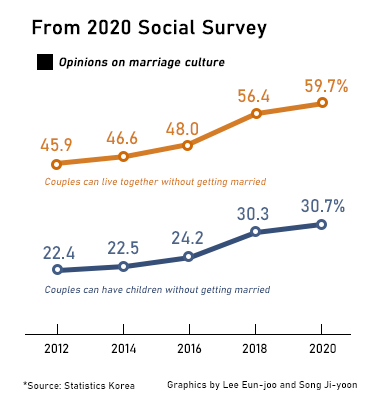

JC: To this day, it is scandalous for unmarried couples to live together.

AA: Really?

JC: You know how in the States it is considered good common sense for the average couple to date a little bit and then moving in is a big step? And then you see how you get on together, sharing a living space and then if everything goes well, you get married. That is frowned upon. Hugely, hugely frowned upon.

AA: Assuming it’s a heterosexual couple, is it equally stigmatizing for the man and the woman when they break up, if they go back out into the dating pool? Is one person’s reputation marred more than the other?

JC: She would be considered chewed gum. Yeah.

AA: But would he? Would he be considered chewed gum too, or no?

JC: No.

AA: Because it seems like in the book that only the woman was.

JC: Yeah, no.

AA: Yeah, that’s what I thought. There’s still, it depends on the community here, that’s for sure true in religious communities in the US, not so much in secular communities. And that’s a perfect segue to the next topic, which is the dynamics in marriage. Again, this is assuming heterosexual marriage because the main character, the title character is heterosexual in the book. But I wonder if you could start this section with that quote that we selected. Would you mind reading that?

JC: “Each time a big family decision had to be made, the mother advised with caution intact and the father generally took her advice. Yes, the woman may chime in, but it’s the man who makes the final decision.” Which also can be very scary for the woman because women in especially Kim Jiyoung’s mother’s generation often had to rely on their husband’s income. And so if he decided to blow the family savings on an ill-advised investment, she could tell him that it’s a bad idea, but she would have no way of stopping him. The thing that I always found interesting was that Korean women never take their husband’s last names.

AA: Oh!

JC: Nobody does that, it’s not a thing that’s done. But then it’s, you know, obviously not an indicator of women’s rights.

AA: Can you talk a little bit about the tradition of a wife, let’s say a new wife, and she’s marrying and her new husband’s family, her job is to take care of his parents, right? Her in-laws as they age, to shoulder that burden. Whatever burden comes, she becomes the person who takes care of them. Even though they’re not her biological parents. Can you talk about that a little bit?

JC: So in the past, traditionally women joined the man’s family. So she was an outsider coming into the man’s family, and the man’s family meant parents and son and sometimes the son’s siblings. So she would have to sort of be the new maid of the family that takes care of all the members of the husband’s family. Which is, I guess it’s different from Judeo-Christian– Is it different from Judeo-Christian traditions?

AA: Yeah.

JC: You know that passage in the Bible, man grows up, leaves his family, starts his own… wildly paraphrasing.

AA: Yeah, cleaves onto his wife. But no, I think that really, really strong tradition of patrilocality where you move in with the husband’s family is not, is not the tradition necessarily. I mean it happens sometimes, but it’s not the expectation in the West. In fact, in our family, my husband is one of three boys and his mom would talk about how she was worried as her boys were growing up that she would lose them because if it does tip one way or the other, that the daughter would stay closer to her family of origin and the husband would kind of go off with the daughter more. But I wouldn’t say there’s one way or the other necessarily.

JC: These days, because of the housing crisis, the children absolutely cannot afford their own place and need to rely on the parents’ money. It’s like, we will let you live with us if you let us live in your house. And we’re going to inherit all of your money and maybe take care of our children so we can go out and work and have a free babysitter at home.

AA: Oh wow.

JC: So that is a very common arrangement in Korea. But in-laws continue to be a big source of conflict among couples. I think, once again, because this is a very small country and you can’t move to the other coast to get away from your in-laws.

AA: Mm-hmm. That’s interesting.

JC: Yeah. And because Korean parents are so possessive of their sons, they end up being very controlling. And that creates a lot of friction within the family. And because the sons are so dependent on their mothers, it is difficult for them to put their foot down, draw the line, and say this new family that I have formed with my wife comes first. It’s very difficult for them.

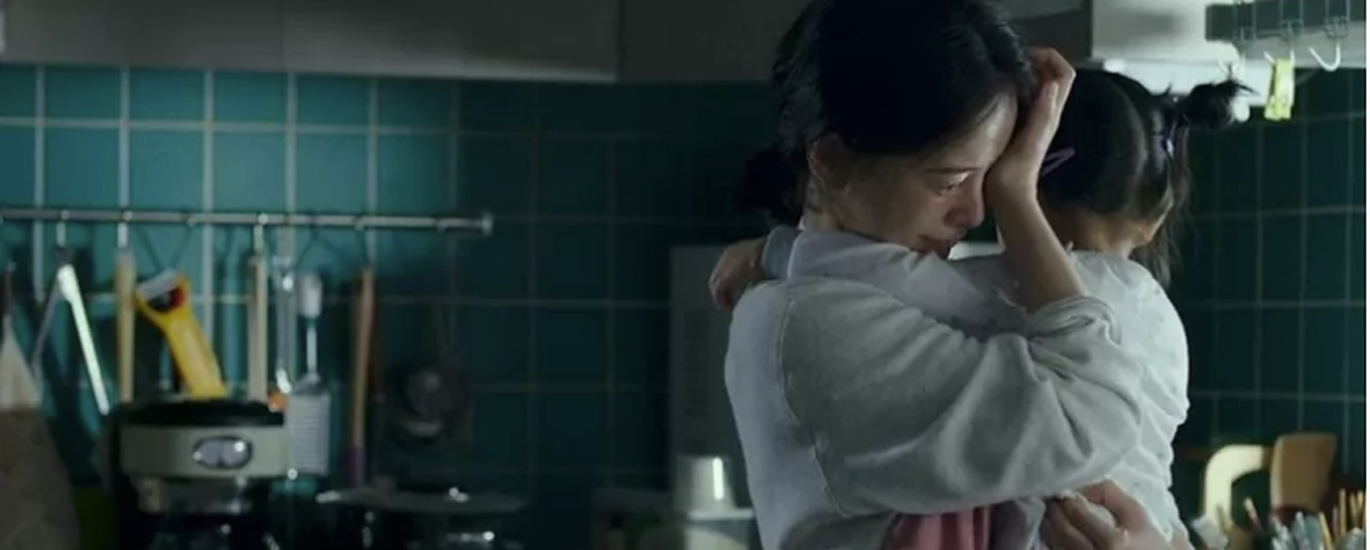

AA: The next topic was women as mothers. And this is, I would say, one of the main themes of the book too. I mean, she spends a lot of time on this topic and she points out all that is lost for women when they give up their careers to stay home and become the full-time caregiver. And then there was this scene where, I mean, she’s made these sacrifices to stay home with their child and then she overhears somebody calling her a roach for mooching off of her husband and just living like a freeloader, when she feels like she didn’t even have an option to do anything else. And it’s making her really depressed and she’s having such a hard time and then she’s vilified for it. Oh, I was so upset. That was so infuriating when I read that part. And then the other thing is in the book, you have a lot of conversations between Kim Jiyoung and her husband. And this is classic. I feel like this conversation happens all over the world and people are trying to move it forward. And I think progress is really being made, at least for sure in the United States. This is a conversation that’s happening a lot in the public, like public conversation is happening where women are saying, again in heterosexual relationships where there’s these entrenched gender roles. We’ve in the past thought of the children’s father as babysitting the kids or helping out like they’re doing a favor. Like they’re pitching in.

JC: It’s not his kids. It’s not his responsibility. He’s just the roommate.

AA: Right? And so he’s doing a huge favor and being like the world’s greatest guy if he takes care of his own child. And this comes up in the book a lot. And I’m wondering if that also, again, provoked conversation in Korea that was like wait a second, why have I been– because we’re all complicit in this system if we haven’t noticed it yet, right? Like, oh, I’ve really been giving myself 80% of the domestic work in the household without even noticing it. You know? It just is something that we fall into those patterns sometimes, sometimes accidentally.

JC: Do you ever, when you go to the supermarket, do you ever see a dad alone with his kids?

AA: It’s rare, but sometimes yes.

JC: Okay. So that’s very rare. That’s a very, very rare site in Korea as well. You would think that because men are supposedly stronger that they will be able to carry children and bags and everything and multitask, but why is it always women with the grocery cart and the screaming children?

AA: Haha, yeah.

JC: I think this idea that men play sort of a secondary role in running the house and raising children is still very, very prevalent in Korea. And you’re dad of the year if you are able to, like, if your wife goes away over the weekend and you watch the kids, you’re dad of the year. It’s just amazing. Also, I think it’s very difficult for women even today.

Birth rate in Korea has plummeted to 0.77 babies per woman. Like three quarters of a baby. So even though the problem’s really serious, it’s very difficult for women to go back to the workplace after giving birth. It’s frowned upon still for dads to take maternity leave to help out with raising their kid. Because, you know, it’s still considered a woman’s job. And I think because of that, companies tend to blatantly favor men over women because they assume that women, once they get married, are going to quit their jobs and go be mothers instead of coming back to work. So they don’t want to invest any sort of time and training and resources on the women. And what I found really heartbreaking was when Kim Jiyoung’s husband tells her “I don’t want you working at an ice cream store. I want you to get a job that you find fulfilling.” And the implication is to get a job that you find fulfilling so I don’t feel embarrassed or guilty that you are working at an ice cream store. Even though you received the same education, you probably worked harder than me to get to where you are. You’re throwing away nine years of your experience in, I think she was in advertising. So nine years of experience in advertising. And so I want you to, you know, get a respectable job. Something that I can tell my friends about, and raise our kid, and do everything else. I thought it was just so infuriating that he was expecting her to do that.

AA: This is a tangent, but I’m going to bring it up right now because I wanted to mention it at some point during the conversation. I thought the book was so effective, one of the reasons I found the book so effective is that none of the men, with the exception of the sexual predators, but none of the men like the dad and the brother and the husband, they’re not monsters. They’re actually real, relatable, and lovable people. And so it came to my mind as you were talking because it reminded me how the husband, he’s not some domineering, authoritarian, horrible guy. He’s not someone who’s like, “don’t you dare work out of the home and you’re my slave” or whatever. He’s like, “Sure, get a job!” But the sexism is very subtle and that’s I think partly why there’s this sense of being gaslit the whole time. Like she just doesn’t even know what this malaise is inside of her, because the men aren’t being horrible. They’re not mean. And I really appreciated that because sometimes if there is just a villain as a character, then the whole thing can be written off as like, “well, not all men are like that.” Because they’re not, because most men aren’t villains.

And so I thought the book did a really good job of pointing out the systemic problems and the structural problems that everybody in society perpetuates. Because it’s nice guys who are doing it too. So I just wanted to throw that out there, because you’re right, the husband is, in some ways it sounds like he is being supportive, actually.

JC: Mm-hmm. That’s something that this book does beautifully. There are all of these things that are just not spelled out explicitly that men could read and have reactions that are so different from the women’s.

AA: The last topic that we wanted to talk about is women in the workplace. Can you talk a bit about some of the examples of structural sexism in the book, and maybe from your own observation?

JC: So, from my own observation, because translation is such a female dominated field, we hardly ever have male colleagues in the room.

AA: Oh, wow.

JC: But I had this very strange experience where I went to a conference and we were doing this round table. It was like four women and one guy. And every time a woman spoke, she would reference something that the man said and go off on that. And I just sat there looking around going, this is fascinating, wow. But if there’s a guy present, they would always sort of acknowledge the guy. I don’t know why they do this, but that’s something that happens at least in academia. Especially if the guy is older.

AA: Were there some examples from the book that you wanted to mention?

JC: Oh, definitely the camera. Definitely the camera, the spy cam incident. It’s not just in the workplace, it’s in public bathrooms everywhere.

AA: Please explain, because this was something that made my jaw drop when I read this part.

JC: Internet porn is out of control in Korea and a lot of the material comes from people who are taking photos of women’s body parts. Sometimes it’s on buses, on the subway, going up and down stairs. Recently there was an article about a student in class taking pictures of their skirt-wearing teachers. So a teacher walks by, students snap a photo. The spy cams these days, like the technology is so advanced that it looks like nothing more than just a pinhead. And it’s so easy to install. They installed them in public bathrooms, university bathrooms, bathrooms in the workplace everywhere. And what happens in Kim Jiyoung is that a spy cam is installed in the office bathroom so they know the people. I’m not saying that it’s okay if you’re preying on people you don’t know, but these are people that you work with. How, who, like what kind of mindset do you have to be in to do something like that? To take pictures of people you actually know and work with every day, like you see them every day. So because of that, in order to raise awareness so that women can look out for cameras, these days, every time I go to a public bathroom, at eye level there’s this public safety message saying “If you see something, say something.”

AA: And that’s what it’s referring to? Oh my gosh.

JC: “If you see a camera, if you see a suspicious looking bolt in the bathroom stall, report it. Say something for the sake of your women who are trying to go to the bathroom.” And so instead of going to the bathroom to do your business and, you know, relieve yourself, you have to nervously look around the stall for suspicious looking bolts or things like when there’s caulk in places where there shouldn’t be caulk. There was this thing going around on the internet about how to spot a spy cam installation in the bathroom. So there was this phase in my life where every time we went into a public bathroom, I would do a quick scan. Even if I’m hopping on one leg, I would do a quick scan.

AA: Wow, that’s a big problem then. Well, that brings us to the end of the episode. And I wanted to wrap up by asking you if you had a takeaway or a scene that really stood out to you from the book.

JC: Well, before I answer my question, what was yours? I’m curious to find out yours because I very rarely get to speak with people who have read the book because I’m not the author, I’m the translator. I’m in the shadows.

every time I go to a public bathroom, at eye level there’s this public safety message saying “If you see something, say something.”

AA: Haha, yeah. So one thing that I did not pick up on until the very end of the book is it seems to change perspectives. And suddenly I’m like, oh wait, who’s talking? This is a man. And it turns out it’s a therapist talking to a psychologist. It’s like this huge grand reveal at the end.

JC: Yes, yes. Because in the beginning, you become so immersed in her story and you never hear from him, it’s not like he pops up every now and then and reminds you of his presence as the narrator. So you don’t even know that he’s there until you get to the end and then you flip to the front and you’re like, oh my goodness. He said in the beginning that this is his report of Kim Jiyoung’s life, based on their sessions.

AA: But I had forgotten that completely. I totally forgot that.

JC: I think that’s one of the brilliant points of this focus is that you don’t realize that and then you get to the end and you’re like, oh my goodness. I have been duped. What else has he been screening?

AA: Yes, exactly. It’s from his perspective all along. And then at the end, the whole book ends by this therapist talking about, I think maybe a secretary that he has or an office assistant.

JC: Yes, yes. Quitting.

AA: Yes. She’s quitting and he’s so annoyed because she’s going to need maternity leave. He’s super annoyed. And then he says “Even the best female employees can cause many problems if they don’t have the childcare issue taken care of. I’ll have to make sure her replacement is unmarried.” The end. And that was just really shocking. And really awesome.

JC: So that was something, like when he says it causes many problems if the childcare issue is not taken care of, you know, as someone with status and resources and his own practice and the psychiatrist who is supposedly sympathetic to the plight of the Kim Jiyoungs, instead of saying, I should help them out, or figure out a way to provide childcare for the women who work for me so I don’t have to keep training new people so I can keep– Isn’t it easier to just keep working with the same people?

AA: Totally.

JC: For years instead of trying to train new people. Like economically I think it doesn’t make sense to just keep hiring new people and training them and losing them. But instead of taking that route, he says I should hire somebody who’s not married.

AA: I should hire someone who’s not married. And I think he even phrases it, “Even the best female employees can cause many problems if they don’t have the childcare issue taken care of.” They have to figure it out. Not a couple together who created that child, and not him as an employer. It’s one hundred percent on the woman to figure it out or she won’t have a job. Okay, what was yours? What was a big takeaway for you?

JC: For me, I have to say it was going back to the spy cam thing. I translated this book in 2018. It was definitely after I finished the first draft and it was in the editing process that I looked back and realized that Kim Jiyoung started working at the advertising firm straight out of college and she had two male colleagues and one female colleague who all started at the same time at the same company. And then after she leaves, the spy cam incident happens and her female colleague is still working there. So that means the female colleague and the two male colleagues, the three of them have been working together at the same company for nine years. So your coworker of nine years is being photographed in the bathroom and you don’t tell her.

AA: Wow, I missed that detail. That’s true.

JC: See, that’s why I had to go back and read the book again to see what else the male psychiatrist left out. Because these are very, very salient details. How can you work with someone day after day in an advertising firm, so they do late nights, they help each other out, they practically live together for nine years and you have so little respect for your colleague that you don’t tell her that this is happening in the bathroom? That was just horrifying. But I’m sure it’s actually happening somewhere that there are people who know that horrible things are happening to their female colleagues but they don’t want to speak up.

It is exhausting to be the person who speaks up. But just every once in a while. I mean, taking care of your mental health is very important and maintaining good relationships, making nice is also important as a social being. But every once in a while, stick up for somebody, especially if you’re a male listener and a person of great privilege. Every once in a while, even if you think that your male buddies are going to make fun of you. Stick up for the woman.

AA: Hear, hear. Well, Jamie Chang, thank you so much for joining us today. I immensely enjoyed our conversation. I love your translation of this book, I highly recommend the book to listeners. Again, it’s Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo and translated by Jamie Chang. Thanks again, Jamie.

JC: My pleasure. It was great talking to you.

this book that she wasn’t sure was going to get published

changed the course of literary history

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!