“rethink the ways in which we use the word and the concept and the category of ‘woman'”

Amy is joined by Dr. Setsu Shigematsu to discuss xer book Scream from the Shadows and the history of women’s liberation in Japan.

Our Guest

Dr. Setsu Shigematsu

Setsu Shigematsu is a mother of two children and an Associate Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at UC Riverside. Xer intellectual and scholarly concerns include the relationship of US and Japanese imperialism, gendered state violence, transnational liberation movements, comparative feminist theory and cultural studies. Xe is the author of Scream from the Shadows: the Women’s Liberation Movement in Japan, and the director of Re-Visions of Abolition (2011/2021), a documentary film about the prison industrial complex and the prison abolition movement. Xe is also co-editor of Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: As a white woman who was born and raised in the United States, I have learned so much during the past few months as I’ve studied patriarchy all over the world, and one of the most valuable new things that I’ve encountered through all of these books and conversations is the concept of Orientalism. We heard a lot about Orientalist tropes during our series on the Muslim world, but Orientalism is a Western attitude toward women in the “East” that affects a huge geographical region from Morocco to Japan. And one Orientalist trope that is quite common is the idea of the quiet and submissive woman who is a passive victim of patriarchy.

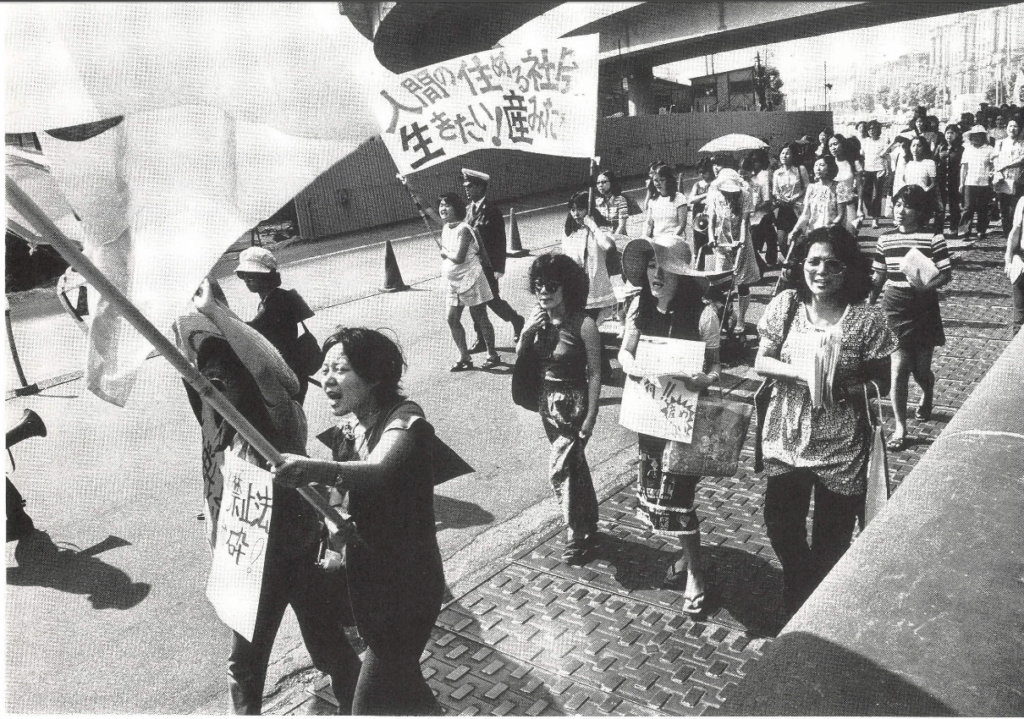

So this week’s book was perhaps one of the most striking challenges to Orientalist thinking that I have read so far. The book is called Scream From the Shadows: The Women’s Liberation Movement in Japan by Dr. Setsu Shigematsu. And from the very first page, I felt surprised and even sometimes shocked. The book describes some of the most radical feminist activism that I have ever read about, and it was going on in the 1970s at the same time as the women’s liberation movement in the United States, but I had never heard of it! This was so new to me and it stopped me in my tracks and made me examine why I felt so surprised at these Japanese women’s radicalism. And this was a process that I was really, really grateful for. So not only did I learn a lot of content, it really helped me develop as a feminist. And I am really, really grateful to have read this book and highly recommend it to listeners. I found it fascinating, and I am so excited to have Dr. Setsu Shigematsu here today to discuss her book. Welcome, Setsu!

Dr. Setsu Shigematsu: Thank you so much, Amy, for that wonderful introduction. I’m thrilled to be here and I’m thrilled to be on this podcast discussing with you about the history of radical feminism in Japan and how it intersects with Orientalism, and really is talking back, if not screaming back, to these long histories of Orientalism and patriarchy.

AA: Wonderful. Well, I can’t wait to dig into all of this stuff, which again was totally new to me and I found it just so intriguing. First, we’ll do a little professional introduction of you and then I’ll have you introduce yourself more personally.

Dr. Setsu Shigematsu is a mother of two children and an associate professor of Media and Cultural Studies at UC Riverside. Her intellectual and scholarly concerns include the relationship of US and Japanese imperialism, gendered state violence, transnational liberation movements, comparative feminist theory, and cultural studies. She is the author of Scream From the Shadows: The Women’s Liberation Movement in Japan, and the director of Three Visions of Abolition: 2011 and 2021, a documentary film about the prison industrial complex and the prison abolition movement. She is also co-editor of Militarized Currents Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific.

Setsu, I’m really intrigued by all of these titles and want to look into all of the work you do. I will say, again, a plug for this book. And I mentioned this before we started the conversation, but I always so appreciate a book that tackles really complex ideas but in clear language that’s accessible. And even though I spend all day every day in academic texts, it still is so refreshing when I read a book that is easy to understand and has vivid stories. So I want to congratulate you on such a fantastic book and your other projects that just sound amazing as well.

SS: Thank you so much for saying that, Amy. I also really appreciate those feminist writers out there like Sara Ahmed, who I was just discussing in a senior seminar yesterday. She doesn’t purposely try to use right jargony, obtuse language just to make herself look smart. And I really feel like we need to, in academia, kind of get over this elitist use of unnecessary jargon if we really do want to change the world. Then we do need to know how to communicate in various registers and not be unnecessarily complex if the topic doesn’t require it. So thank you for saying that.

Just to further situate myself, I was born in Tokyo, Japan, but before I turned one, my family moved to London, England. And so I grew up in Canada, England, and then moved to the United States for graduate school. But while I was in graduate school I decided to do my work on the history and philosophy of the radical feminist movement very much in part because as someone of Japanese heritage, I definitely felt caged by the stereotypes of the Orientalist trope of the Asian woman being submissive. And not only that, I even shared with my students recently that a white guy had said to me that based on the movies that he’d seen, he thought that all Asian women were prostitutes. Because of their representation in Hollywood media.

AA: Oh wow.

SS: Yes. So kind of thinking about that level of sexualized, racialized, gendered representation that was so common through Hollywood and Western media. Not only are we working against these centuries of Orientalist literature and representation, but that trope or the stereotype of the geisha as being so prominent as well in people’s imaginations of what Japanese society is like. I was growing up in a predominantly white society, and while my mother was a highly educated woman, she graduated from Berkeley in 1960, she would tell me things like, “Yes, in Japanese society women were required to walk three steps behind the man.” And all of these kinds of understandings of how Japanese patriarchy were also constraining her life and her grandmother’s life. I grew up with these stories so when I had the opportunity to start reading about radical Japanese feminism, I was immediately hooked and decided this needed to be my area of research. Because not only did I want to know what these radical Japanese feminists were saying and doing, but I was hungry to learn about the history of revolutionary women in Japan.

AA: Fabulous. Well, let’s dive right into that topic and maybe how we can start is for you to set the stage and talk about some of the historical context of what came before this book. This book highlights a specific movement in Japan in the 1970s, but if you could give us kind of a bird’s eye view of the systemic patriarchy that existed at the time, then maybe we can use that as a jumping off point.

SS: Sure. So, I’m sure as the listeners know, Japan and the United States were in what was called World War II, but I like to refer to it as an inter-imperialist conflict. They were late imperial powers clashing with each other about territorial domination in Asia and across Asia. And after the defeat of Japan in 1945, the United States was occupying Japan until 1952 and they did create this new constitution which was considered very progressive at the time, but because they were offering these ideals of democracy and equality in the new education system in the post-war, there was such a deep contradiction between what the post-war generations were learning about and their lived reality.

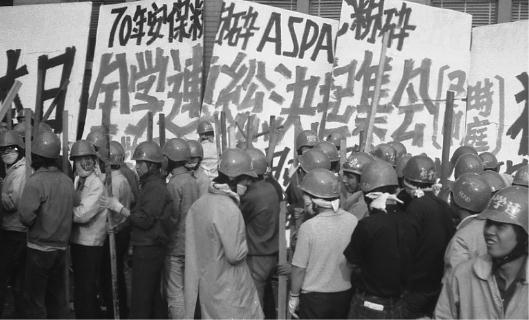

And so in 1960, there was a huge protest across the nation to try to end the military alliance between the United States and Japan that was known as the Security Treaty. And despite the fact that millions of Japanese were in the streets protesting against the Japanese government, there was definitely a kind of still authoritarian practice in the time of these protests. There were many women who became involved in student activism, there were women who became involved in Communist and Marxist and revolutionary groups, and this kind of activism continued and was quite robust across college campuses.

And so leading into the next renewal of the treaty in 1970. As there was radicalism happening all around the world, you know, in the United States, in Europe, the anti-Vietnam War movement was catalyzing so much anti-war activism as well. In Japan, many students also became involved in anti-Vietnam war activism. They became involved in various kinds of New Left movements. And through women’s experience in these political spaces, they also began to criticize the sexism that they were experiencing from the leftist men, from the activist men. And it was the sexism that they decided that they no longer wanted to put up with that led them to create the separatist radical feminist movements that became the beginning of “ūman ribu” which is a kind of Japanese alliteration of Woman Lib. So they called themselves “Woman Lib” and the Japanese pronunciation of it is ūman ribu. This is the name that they decided to raise as their new banner of this radical women’s liberation movement that was very much tackling concepts like women’s sexual liberation and sexuality in new forms that had never yet transpired in Japanese society in the kind of language and militancy and the kind of rejection of Japanese patriarchy. It had hitherto not been seen even in various socialist, communist, and Marxist formations among women.

AA: I can recognize patterns that were happening in many places all over the world at that time, and that’s so interesting to hear about how it was happening in Japan. One concept that came up in a book that I read prior that we talked about in the podcast earlier on patriarchy in East Asia was the concept of “good wives and wise mothers”. Could you talk about that just a little bit?

SS: Absolutely. So there was a state propagated concept of ideal womanhood. And in this slogan, “good wives, wise mothers,” it encapsulated this prescription of heteronormativity for women to become a good wife to a man and then a wise mother of his children. And this concept in Japanese was called “ryősai-kenbo” but it was very much a norming cage in which women were required to be married and then reproduce children for their husbands, for the nation, and then all of this concept of the nuclear family of patriarchy would then be recorded in this family registry system in which you would have to designate one head of household. And in about 98% of cases, that one head of household would be the man, hence the patriarchy. And so there was definitely a very clear system in which a state-enforced family system is very much at the core of Japanese society. And that very much took on this patriarchal form and pre-modern Japan also had a longer history of patrilineal property transfer.

they were offering these ideals of democracy and equality… there was such a deep contradiction between what the post-war generations were learning about and their lived reality.

AA: So in this context of “good wives, wise mothers”, patriarchal, husband-led families that comprise the kind of patriarchal state, it was in this context that the women’s lib movement in Japan rose up because women were being trained in other civil issues and they’re saying we’re rejecting sexism across the board. Am I understanding this right as I’m summarizing it?

SS: Though women who were rejecting the sexism were women who were already politically active for the most part. And many of them were single, but not all of them were single.

AA: So what would you say their main objectives were? If there are bullet points, here are the patriarchal systems that we want to dismantle in Japan.

SS: So to summarize their key concepts, definitely one was the liberation of sex. It was the liberation of Eros. They also launched this major critique of the family marriage system. And I’m putting those two things together because obviously the family was supposed to be properly reproduced within the heteropatriarchal marriage system. And so along with that was linked, as we understand, the kind of control of women’s sexuality to be at the core of the patriarchal family marriage institution. And so they were rebelling against this institution because the way in which marriage laws historically and social norms additionally were reproduced was that women were to be monogamous and men had the right to do whatever they could afford to do sexually. And there was a long tradition of what we would refer to as a Red Light District, but there was a whole name for it and a concept in Japanese called “mizu-shōbai”, the water industry. And this double standard of one wife-one man marriage system even though there is this concept of monogamy in Japan, these radical feminists were saying that monogamy is only enforced for men. And so hence at the core of their critique of the marriage family system was a critique of one-way double standard monogamy as well. And hence, this concept of the liberation of sex was very much core to their cry for how women needed it to be liberated.

AA: So was birth control widely available at the time? Because that’s the risk for women that men don’t necessarily take on, right? That women are stuck with the pregnancy and men can just walk away. Did birth control play a part in that?

SS: I’m glad you brought up the question of birth control because that, I think, is one of the most significant distinctions between how the women’s lib feminists approached the right to use the pill compared to that of what was happening in the US feminist scene. Because actually many of the activists who, and I would say the majority of the radical feminist activists in the movement were not necessarily pro-pill and were actually wary of the pill because they feared that because the government ultimately controlled the pharmaceutical corporate, basically distribution of the pill, they worried that it would be another way in which the state would control women’s sexuality.

So they were not involved for the most part, except for one particular very well-known radical feminist sect called Chūpiren, and actually the P in that refers to “free the pill”. And this group was very much covered in the media because they did a lot of high visibility protests. They would don pink helmets and they got a lot of media attention. And this was the one group that was trying to demand for greater access to the pill. And they were calling out things like, you know, they would go to men’s companies and do direct action protests against men who were having affairs. But this was just one of the sects in the entire movement. And many of the other women activists were very critical of this sect because they said, we actually don’t care that much about using the pill and we don’t care if men are necessarily having affairs in marriage because we disagree with the marriage system. So they were having a larger systemic critique of the way in which the state was trying to control women’s reproduction even by regulating access to the pill. So they were very wary of focusing too much on the pill or focusing on something like men who were having affairs because they did launch a larger critique of marriage and monogamy.

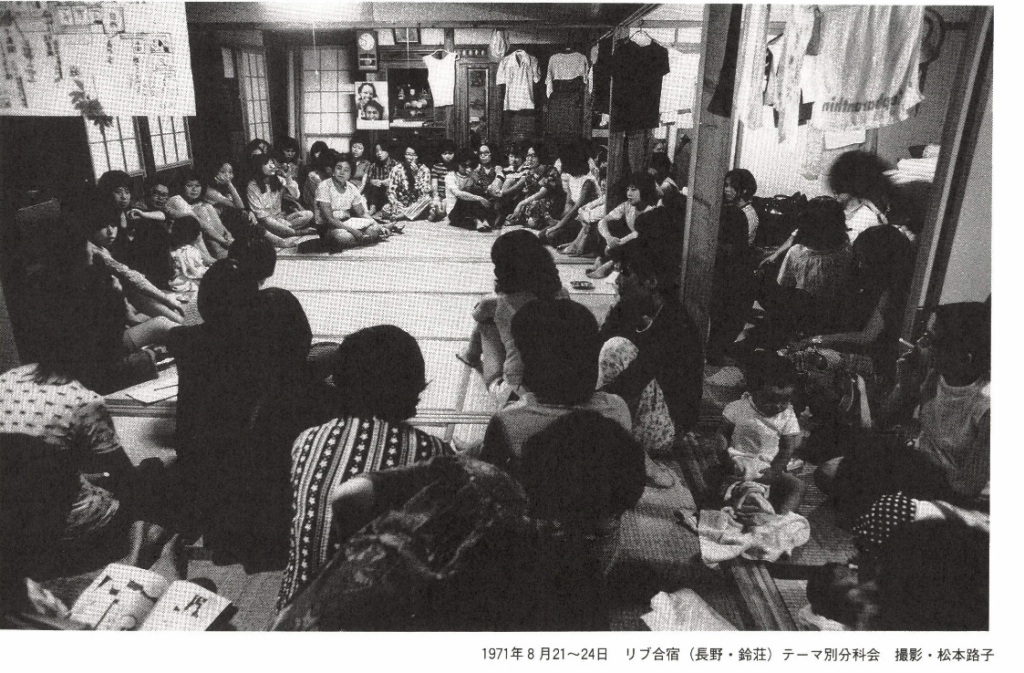

AA: One of the photographs that I remember most from the book was a photograph of a commune with mothers and children where they raised their children communally. So that was one of the adaptations, I guess, that they employed in rejecting patriarchal, monogamous marriage. Just like, if we get pregnant, we’ll raise our kids together. Is that right? That was such an interesting part to me.

SS: Yes, yes. And so, part of their various experiments in rejecting patriarchy was to form these communes, which as you described, were women and their babies. And they would be raising them as opposed to sticking to the nuclear, heteronormative, patriarchal model. And so these communes were popping up in different cities, in different parts of Japan, and that was one of the radical ways in which women were rejecting the patriarchal model.

And then other women who were partnered with men would oftentimes just refuse to comply with the normative registration procedures of, you know, registering themselves as part of a man’s household registry and whatnot. So there were various kinds of resistance, but that was definitely a really excellent example of how they were all about trying to live and embody their politics.

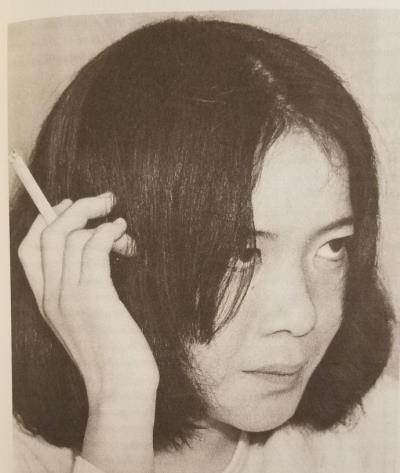

AA: Mm-hmm. The next question I wanted to ask you was about Tanaka Mitsu. And you write that you can’t even talk about the movement without talking about Tanaka Mitsu. So can you tell us who she was?

SS: Yes. Tanaka Mitsu was, we might understand her as one of the charismatic figures of the movement who was self-educated and didn’t necessarily bring the same kind of discourse as many of the other activists were bringing to the space. And she was also someone who had a way with words and was a very talented speaker and writer, and definitely someone who thinks and moves way outside of the box. And so she wrote what were, and are remembered as probably the most famous or well-known manifestos of the movement. And one of them was called “Liberation from the Toilet,” if we were to give it a kind of western translation. And she wrote other important manifestos like the “Liberation of Eros”, and she oftentimes became the spokesperson who talked to the media. And so her name was definitely out there, even though there was no formal designated leader of the movement. But she definitely had very unusual ways of articulating a kind of feminism in that moment.

One other way to characterize Tanaka Mitsu, which other people would use to describe her, is a reporter from this newspaper called Asahi Shimbun said she was kind of a medium and there’s a concept of like the kind of shaman medium of the movement. And that word in Japanese is “miko”. So I think that other people also kind of understood her to be the kind of spirit, the person who articulated the spirit of the movement in a public facing way. And I think that that’s a helpful way to think about her role in the movement because we know that oftentimes movements have de facto leaders, even though they don’t necessarily have that formalized title or structure.

AA: The next question I have for you is about the Women’s Lib stance on violence. And these were some of the passages that were the most surprising to me. I’ve said before on the podcast many times that technically the definition of radical feminism, radical just means from the root, right? So it just means you are not trying to reform things on the surface, we’re trying to dig at the roots and uproot the system and then plant something completely new. But when people hear “radical feminism” they sometimes think of violence. And so I really enjoyed these sections and learned so much from these sections where these feminists were not only radical in the true definition of the sense in their uprooting things, but they are really trying to figure out whether they want to use violence or not. And so some of the subtopics and under this topic of violence were the feminists’ stance on abortion. And then a very evocatively titled section called “Mothers Who Kill Their Children”. And then you write how some of these feminists were practicing martial arts training, and there was this concept of “the choice of whether or not to strike”, so whether or not to use violence. I know that’s a lot to throw at you, but maybe if you could just choose some of those topics to talk about…

SS: Definitely. Thank you for that question because this is one of my longstanding obsessions, is women’s relationship with violence. And to think about how ūman ribu is very different from what we commonly understand to be radical feminism in the US context, interestingly enough, speaking of Tanaka Mitsu, she had a very unusual approach to abortion. Insofar as Tanaka Mitsu actually admitted that abortion was violence. And in that sense, the discourse of ūman ribu and Tanika’s discourse as well did not emphasize women’s right to abortion. And I understand that at the moment that we’re currently in, this is a really difficult way to think about how the current abortion wars are playing out in the US. But Tanaka Mitsu did speak about women aborting their children as a type of violence towards that potential new life.

But this was also consistent with her overall very unusual feminist approach to violence, because Tanaka Mitsu described this concept of a transhistorical grudge that women carry in their wombs due to all of the sexist oppression women have experienced over the years. And she actually encouraged women to acknowledge this transhistorical grudge that they carry in their wombs as a force for revolutionary change that women could tap into. And the way in which she linked this concept of this grudge that women actually carried in their wombs was the example of the very tragic way in which there was, at the time of the movement, media coverage of this new phenomena of women who were living in urban centers who couldn’t handle motherhood on their own. And because they were so isolated from their extended families and isolated in these new urban apartment buildings, there were a spate of cases where women were leaving their children in lockers, in train stations, and even putting them in trash cans. And so the media was doing this sensational coverage of this new phenomena of what’s called in Japanese “kogoroshi onna”, women who kill their children.

a transhistorical grudge that women carry in their wombs due to all of the sexist oppression

This was to me one of the fascinating campaigns that these radical feminists engaged in by trying to produce a discourse around these women who were doing violence towards their children by trying to say that this is symptomatic of the society at large, as opposed to just falling into the criminalizing discourse of these are terrible, sick, crazy women, we need to condemn them. So what I loved about this attempt to intervene on this phenomena of women killing their children was their way in which they said that we need to understand what you were talking about, what are the root causes of this happening. And in that sense, to me it was a proto-abolitionist feminist response because rather than going to the default criminalization of individuals, they really wanted to understand the conditions for each of these women. And they began to study the conditions that these women were experiencing that led them to harm their own children.

And then some of the activists would even go visit them in jail to see and to try to talk to these women and through the conversations they would learn about why they became that desperate to harm their own children, which Tanaka still understood to be almost against the nature of what mothering was about.

AA: It’s such an interesting and complicated discussion. And her stance, again, was kind of… I guess maybe not intuitive for me, but the deeper I got into it the more I understood it and it was so interesting. I’m glad you brought that up, because I’d actually forgotten about that part with the grudge that the womb carries. A book and a concept that is in a lot of my conversations with friends lately is that book, The Body Keeps the Score. That we have trauma in our bodies and that intergenerational trauma that gets passed down in our DNA from prior generations of violence that’s such an important and interesting concept that they were already talking about in the ‘70s, long before that was in the general discourse, at least to my knowledge.

SS: Right, right. And I like that book too, so thanks for mentioning it.

AA: The next question I wanted to ask is about the New Left, and that phrase might be new to listeners. So can you tell us what is the New Left? And you referred to it a little bit earlier in the episode where you say that there was a lot of sexism among the men who were doing other kinds of activism. But if you can just talk about that a little bit more, and specifically Zenkyōtō.

SS: Thank you. Sure. So the New Left is a term that is used both in Japan as well as the United States. In the Japanese context, it refers specifically to these Marxist groups that emerged throughout the 1950s that had broken off from the formal organization of the Communist Party and the Socialist Party. The Communist Party and the Socialist Party were both very top-down authoritative leftist political parties, and they wanted to maintain control over the student activists. But because the student activists wanted to reject their authoritarian, top-down approach, they broke away from them deliberately among the student movements. And there was this major organization called Bund, which was a formation of various Communist, Marxist, leftist, socialist students who formally rejected the Communist Party.

And then the New Left basically became a bunch of various sects of Marxist, Leninist, socialist student activists, primarily. Although students who had graduated, students who had quit being students and become professional organizers, they were parts of these various New Left sects and some of the women activists who started ūman ribu had experiences in these New Left sects.

AA: I do have to throw in here too, I did some research on the iteration that happened in the United States of sexism within the New Left for my master’s thesis, actually. And it was so interesting to see how these things were going on in parallel at the same time. So can you talk a little bit about Zenkyōtō?

SS: Yes, I just realized that I forgot to answer that part of the question. Zenkyōtō was a student organization that crossed campuses and these leftist students rejected the New Left. So there were like these layers whereby the New Left is rejecting the Communist party and the Socialist party, and then the Zenkyōtō activists were, for the most part, rejecting the dogma that became characteristic of the New Left sects. Because even among the New Left sects, some of them became very hierarchical and very authoritarian and top heavy or top-down. And some even became quite even militaristic in their organizing style, especially as the militancy increased. And the Zenkyōtō activists were the ones who were saying, we do not want to follow anyone’s dogma. Zenkyōtō was a much looser network of students across multiple campuses that were taking over campuses, occupying campuses. So much so that by 1968 there were student occupations across over a hundred campuses in Japan.

AA: Speaking of student movements, one of the sections that I thought was interesting was the section on women’s theory and some of these intellectual strains that were coming out of the movement. You give some really interesting examples of radical feminism, including rejecting masculine structures of work ethic and science and linear thinking, and kind of examining things that we take for granted as we go through school and we go through life the way it’s structured. And they were kind of rethinking everything at the time, right?

SS: Yes, absolutely. And thank you for bringing up the concept of women’s theory. As someone who’s been in the academy for a few decades now, I think that it’s another way to describe feminist philosophy. And one of the key, and I think enduring concepts that this thinker Tokoro Mitsuko critiqued, and she was actually part of the pre-Zenkyōtō movement, she was a graduate student in the sciences at the University of Tokyo. And she launched this critique of the logic of productivity as well as part of this notion of women’s theory. And by rejecting this kind of capitalist form of productivity, which we can now understand is also critiquing things like ableism and the way in which the logic of productivity can infect not only workspaces and corporate kinds of labor conditions, but actually can also infect the way we go about our activism. So I think that her critique of the logic of productivity and the ideas of western science and western rationality was also important.

In terms of core philosophical rejections of the way in which we think about knowledge, I think that at the outset of the movement they were able to tap into the writings of these Japanese feminist thinkers who were providing these pretty comprehensive critiques of what we would understand to be as masculine as thought, as masculinist concepts of rationality. And how those were being idealized as high value forms of knowledge and encouraging other kinds of concepts that we might appreciate as centering the body and coming from the body and not excluding the body according to the kind of mind-body Cartesian split of subjectivity.

AA: One thing that really impressed me from the book is, as I was comparing my own experience with a feminist awakening in a Western context and reading all of the Western essential texts of feminism as I did, one thing that Western and white feminists still struggle with is not including an intersectional awareness, not realizing ways that we as white women oppress other groups. And I was really impressed that the Japanese women’s liberation movement seems to possess, right from the very beginning, an anti-imperialist consciousness. Where it seems that they were more aware of ways that they had privilege and that they might be oppressors as well as the oppressed. So I’d love for you to talk about that a little bit.

What are those dynamics in Japan and what are those intersectional aspects of feminism that they were aware of?

SS: Well, thank you for asking that question and for also speaking directly to and owning white feminine privilege. I appreciated very much learning about how these radical feminists were also inheriting a concept of the duality of their positionality as both the oppressed and oppressors. And I think that that’s a really important point of departure because Japanese women had benefited from the albeit short imperial history, conquest, domination of the Japanese empire over other Asian nations. So I think that in the wake of the defeat and the post-colonial structure that Japan was in, vis-a-vis these other Asian nations, the Japanese feminists in this movement were taking stock maybe more akin to German radical feminists of the violence that had taken place under the umbrella of Japanese national imperialism.

And so I think that that history allowed for and encouraged this level of reflection of how once a nation-state engages in state violence and how citizens of that nation state can be complicit. In those forms of violence, whether it was in the present or in past history. So I think that that’s an important lesson that white American women and feminists can really learn from is this example of these Japanese women understanding their identity as being always potentially oppressors and the oppressed. And in that sense there was a kind of element of intersectionality there in terms of their awareness of ableism as well for some of them. But at the same time, I do think that they were not as rigorous as we could ideally be on issues of racism and classism. And I think that that’s something that middle class and class-privileged feminists here and everywhere still must continually struggle with.

AA: Absolutely. I know that this is a little bit of a tangent, but because we aren’t going to be able to have a chance to talk about it elsewhere, I’m wondering if you could talk about a couple of the specific examples of women who were oppressed, or ways that Japanese women did find themselves in positions of privilege. In the book, it talks about Korean comfort women and the oppression of Okinawans, and that was completely new to me. I had no idea that Okinawans were considered kind of a different class in Japan. Could you talk about that just a little bit?

SS: Absolutely. To take up the subject of comfort women, actually this is still an ongoing, raging debate across the Pacific where you even currently have Japanese right-wingers who are trying to remove comfort women’s statues in the United States. So it’s even a transnational issue that other authors like Lisa Yoneyama talks about in her book.

The comfort women, even though it became much more prominent in the 1990s, I appreciated the fact that the activists of the 1970s were talking about their positionality as Japanese women towards the sexual violence that happened to the comfort women. And so even though the women activists of the 1970s were not directly complicit in the system of sexual slavery that the Japanese Imperial Army set up during their imperial and colonial domination of the rest of Asia, as women who had the privilege of being Japanese, they were actively taking stock of how their relative privilege as Japanese women had an effect of continuing to potentially oppress Korean women. Because there were many ways in which the comfort women system was reformed in the postwar period by women in Korea who were still in the sex industry and doing that out of conditions of economic violence. And there were protests that these activists engaged in against Japanese businessmen who were going, for example, to Korea to engage in these sex tours. And they saw that there was a kind of parallel between the sexual violence against the Korean comfort women and the ongoing forms of sexual exploitation that they saw Japanese businessmen continuing to engage in. And so although the military wasn’t necessarily directly involved in the case of these sex tours in the post-war period, Japanese women definitely still wanted to take stock of their complicity and their privilege vis-a-vis Korean women, whether it was the comfort women or sex workers in Korea who were being kind of coerced into such conditions due to structural economic violence.

So Japanese women have an ethnic distinction from Okinawan women who would be indigenous to Okinawa. And Japanese women from what’s considered mainland have a racialized understanding of Okinawan women. And Okinawan women in that sense comprise a distinct ethnicity within the larger, let’s say nation-state formation of Japan. And Okinawan women on a day-to-day basis have to live with the enormous colonial presence of the US military in the post-war period. Because 70% of the US military bases are concentrated in the smaller territory of Okinawa. And as a result of that ongoing military colonization of Okinawa, Okinawan women face the threat of sexual and violence from US soldiers who are based there and the kinds of dangers that are a result of having such a huge concentration of tens of thousands of US personnel who are based in Okinawa. And as a result it’s a much more intensified kind of colonialism that they are forced to live under as opposed to Japanese women. So in that sense, the ongoing forms of sexual and gendered and racialized violence that Okinawan women are subjected to because of these larger conditions of imperial colonialism and militarism are ways in which the Japanese women as a whole don’t have to deal with on that day-to-day lived basis and the structural conditions in which they’re placed.

AA: Hmm. Well as I said, that was totally new to me, so I’m really grateful that you wrote about it and then spoke about it just now. So, thank you. Back to the Women’s lib movement, one of my questions was how it was covered in the media. Did mainstream Japanese citizens know about the movement that was going on, and how was it perceived in the broader culture?

SS: The ūman ribu movement was definitely covered in the largest newspapers in Japan and the weekly magazines. And for the most part it was dominantly covered in this kind of mocking, sensationalized, sexist manner. And so it was very frustrating for the activists to often engage with journalists and the mocking headlines that the magazines would put out there. It would be the ‘70s equivalent of clickbait. And so they would put, for example, headlines like, “this activist is trying to liberate everyone without her shirt on” because there were moments when the radical activists would go to the mountains and they would have summer camp up there, and as part of their liberation practice, they might have been dancing in the nude outside. And then the journalists would capture some of these photos and then spread them and say, “oh, look at these crazy women doing these crazy things.” So it would kind of be the equivalent of the bra burning kind of stereotype that the media created in the United States. But in the case of Japan, it was in some sense even potentially more “extreme” because in the US you didn’t necessarily have these images of topless women revolting against patriarchy. But then you have that in Japan and then it’s completely sensational because while you might have images of topless women like in pornography, the fact that these were women were claiming to be feminists, or they weren’t necessarily using the word feminist to describe themselves, but you could see how how that could so easily be twisted and misrepresented or used as a source of mocking the movement.

AA: Yeah, definitely. So was there a backlash against it then? Was there a backlash against the women’s lib movement?

SS: I think that the backlash was even more sustained against the feminist movement writ large in the eighties. Tomomi Yamaguchi writes about that at Montana State. So there definitely was a backlash against feminism writ large and perhaps the backlash against these radical feminists may have been taking place at the time directly through the apparatus of the mass media, I would say.

AA: Well, that brings me to one of the last questions, and I know this is a huge question to just throw at you at the end, but because the book mostly just talks about the movement in the 1970s, I’m left wondering, exactly to your point of maybe the backlash in the 1980s, but what happened after that even, and what would you say is the state of gender dynamics in Japan today?

Okinawan women on a day-to-day basis have to live with the enormous colonial presence of the US military…

SS: Yes, that is a pretty huge question. And for me, still a kind of resounding question mark because it’s so hard to, in a sense, generalize across the generations in terms of where we’re at with women’s liberation in Japan. I could make a few comments in terms of this phenomena during the Abe regime and some journalists would come and ask me about the fact that this, to my mind, conservative, right-wing, pro-military administration was using slogans like “Womenomics” to try to say “we’re trying to push for women’s equality in the business and workplace.” But that was the most cynical appropriation of using a conservative logic to incorporate women back into the labor force as opposed to actually creating gender equality in society. In terms of making a comment about gender conditions in Japan today, again it’s hard to generalize, but I do think that thanks to social media being a force in which people can access various kinds of information, including feminist content, I think that that is still a hopeful arena whereby younger generations of feminists in Japan can tap into these kinds of feminist media, feminist discourses if they’re not getting access to that kind of education in classrooms at the college level.

I still think that there is a dearth of feminist and gender studies and women’s studies content offered widely in campus settings in Japan. But I do think that there is this, as is everywhere, this ongoing struggle over gender, politics and, and gender liberation especially as well with the emergence with the continued struggle over LGBTQ+ politics. And so I think that the challenge in the present is also how feminists of previous generations can then engage with ongoing issues of, let’s say trans politics and how we need to even rethink the ways in which we use the word and the concept and the category of “woman” as opposed to constantly rethinking what is our praxis for gender liberation for all.

AA: One other thing that I wanted to follow up on is that earlier, just a couple questions ago, you mentioned that some of the activists wouldn’t necessarily have identified as feminists. I’m wondering if you could talk about how the word feminism is perceived in Japan, was perceived then, or is perceived now, or however you want to take that.

SS: Thank you. Thanks for that question. At the time of the ūman ribu movement, the women’s lib movement in Japan in the 1970s, feminism was not a word used to describe the movement or the activists. Feminism was introduced in Japan in the late 1970s and it became linked to, adopted by, and taken up by feminists who were primarily in the academy or definitely feminists who were more associated with a kind of middle class respectability politics. So definitely in the case of Japan, feminism is linked to academic feminism and it is definitely a source of identity for many women in the current context. But I do want to make that distinction of the fact that it is not necessarily the term used by this particular movement. And there was actually in some sense a kind of tension between the women lib activists who were very direct action and considered militant in contrast with many women who later came to identify as feminists and were involved in kinds of activism, but were not necessarily thought of as militant direct action, but were more into a kind of reformist, even liberal feminism.

AA: Okay. Yeah, that makes sense. That’s so interesting. And that’s, again, one thing that I’ve learned so much as we’ve studied all these different regions of the world is that this word is so loaded and means so many different things and carries so many connotations in different places. So it’s really useful and helpful to understand that. Is there anything else that you’d like to share?

SS: As a teacher on a college campus, I’ve been working with more transgender students on campus, more students who identify as non-binary. And through my work with them and ongoing LGBTQ politics, I’ve also been challenged to think more about my own cisgender privilege. And in terms of self-introduction I know now it’s a much more common practice to introduce your preferred pronouns. And a few years ago I decided to use very unusual pronouns following a fellow Asian, a feminist scientist on my campus using the x-pronouns: xe/xer/xem. And I use those just as a signal for folks, you know, because they’re very unusual and it sometimes becomes a conversation starter.

But just in line with the theme of your podcast, for me, they are a way to on a very day-to-day basis, just F the patriarchy. So in that sense, that’s how I kind of write, it’s kind of like my little signal card to basically say that I think we can try to disrupt that kind of patriarchal binary, gendered binary, in whatever creative ways we can in our day-to-day lives. So that’s where I’m coming from in terms of my current preferred pronouns.

AA: Oh, I absolutely love that. Okay, so it’s x-e for xe, x-e-r and x-e-m.

SS: And I mean, I don’t think that they’re very common, but I’m just kind of being, I suppose, experimental with refusing because I present as very traditionally feminine. And I am legally married to a man so because I get that kind of heteronormative treatment and privilege, I’m trying to resist that by just kind of rejecting the gender binary by adopting those. And that’s one of the things that I’ve been doing in recent years.

AA: I love it. Well, I think that’s fabulous and what a wonderful way to wrap up this episode because I feel like that is kind of what the legacy is of these 1970s feminists in Japan, is their experimentalism and their radicalism and they’re questioning everything. I think that’s a beautiful, practical thing to do in the personal life is to say, well, what am I gonna do? I have this one life and what are some ways that I can disrupt this and lead people to think and to question? So that’s awesome. Thank you so much for sharing that. And thank you again so much for being here. Thank you for your book and for all the work that you do, and thank you for this illuminating conversation today.

SS: I’ve enjoyed it so much. Thank you so much, Amy. So glad to share with you on your show.

I think we can try to disrupt that kind of patriarchal binary, gendered binary, in whatever creative ways we can

in whatever creative ways we can

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!