“These things that we now get so agitated about and start saying are so controversial.

Go back 300 years and nobody would turn their hair.”

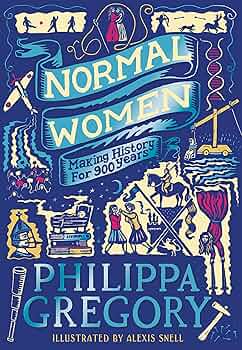

Amy is joined by historian and author, Dr. Philippa Gregory, to discuss her newest book, Normal Women, exploring 900 years of women’s stories including the origins of the gender wage gap, the history and normality of women loving women, where our abortion laws began, and much much more.

Our Guest

Philippa Gregory

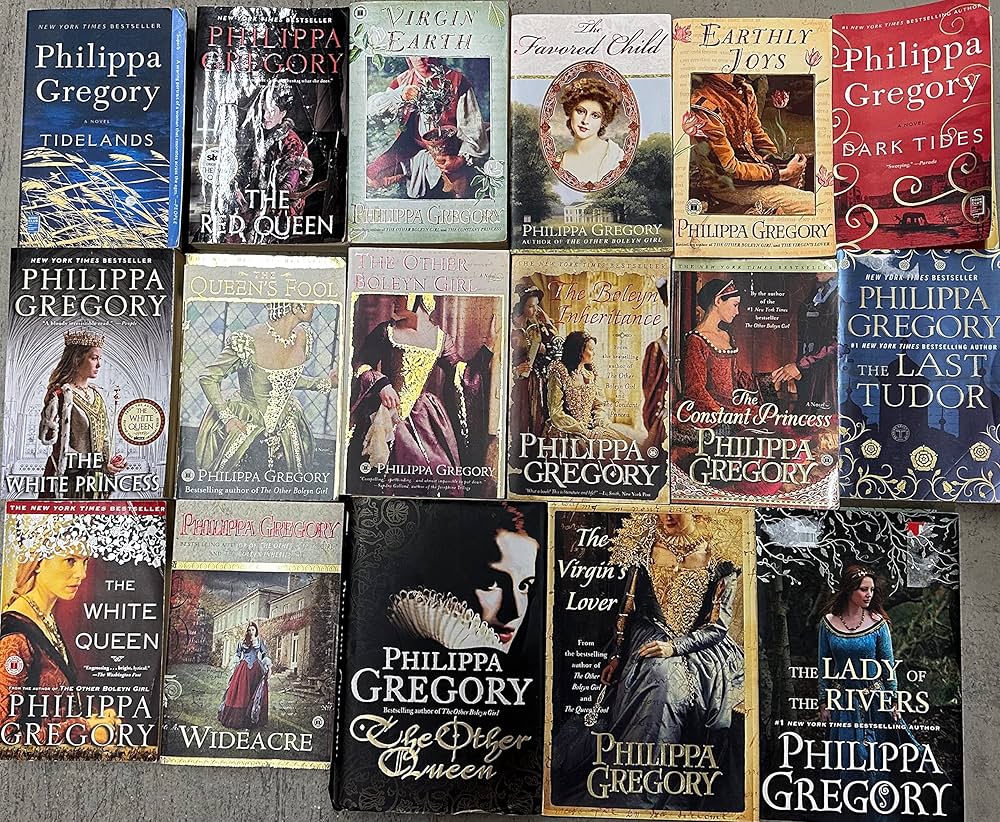

Philippa Gregory is one of the world’s foremost historical novelists and non-fiction writers. She wrote her first ever novel, Wideacre, when she was completing her PhD in eighteenth-century literature and it sold worldwide, heralding a new era for historical fiction. Her flair for blending history and imagination developed into a signature style and Philippa went on to write many bestselling novels, including The Other Boleyn Girl and The White Queen.

Now a recognized authority on women’s history, Philippa graduated from the University of Sussex and received a PhD from the University of Edinburgh, where she is a Regent and was made Alumna of the Year in 2009.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: I’d like to begin our episode today with a quote about women, about English women specifically, and the place that they’ve been relegated to in our popular history: “when we think of English women of the past, we mostly think of the women of the 1800s and 1900s: big dresses and stage coaches, bonnets and balls. These two centuries were when women’s lives were the MOST limited, women were the MOST inactive and – since they had to give all their wealth to husbands on marriage – the POOREST. It was the start of the modern world – and women had no place in it. But there is much more to history than those 200 years – and women were powerful, active and effective in ALL of it.”

This passage is from author Philippa Gregory’s book, Normal Women, and I find this quote distressingly true. Whether it’s Pride & Prejudice or Downton Abbey, our cultural concept of historical English women, especially here in America, is most often confined to “bonnets and balls”. But women have been, and always will be, so much more. As Philippa Gregory writes, “Women have been soldiers, spies, business owners, rulers, revolutionaries, scientists, and more. Women have been nearly everything.” And so in the spirit of rediscovering and reclaiming these forgotten stories, I am thrilled to welcome the incredible novelist and historian, Dr. Philippa Gregory! Welcome Philippa…

Philippa Gregory: Hello. Good to be with you. Thank you for asking me.

AA: Philippa Gregory is one of the world’s foremost historical novelists and non-fiction writers. She wrote her first ever novel, Wideacre, when she was completing her PhD in eighteenth-century literature and it sold worldwide, heralding a new era for historical fiction. Her flair for blending history and imagination developed into a signature style and Philippa went on to write many bestselling novels, including The Other Boleyn Girl and The White Queen.

Now a recognized authority on women’s history, Philippa graduated from the University of Sussex and received a PhD from the University of Edinburgh, where she is a Regent and was made Alumna of the Year in 2009.

So congratulations on all of your work; I’m a big fan and so thrilled to have you here today. And I wonder if we could start, before we dig into the book and into history, I’d love it if you could introduce yourself a little more personally, tell where you’re from and some of the major life events or factors that went into making you the person you are today and doing the work that you do.

PG: Well, probably the main thing I should say to you is I’m 71, so the main life events… there’s a lot of them. We won’t go into all of them. There’s too many. I think my inspiration for my work came from very, very early on a real love for history and a real sense that I feel that I know nothing unless I know what came before. Whether I’m looking at a building or whether I’m going for a walk or whether I’m talking to somebody, I always want to know what was happening before this event. So a building, how old is it? How far back does it go? And you know, with people, I always want to know what their parents did and their grandparents did. And that curiosity was what drove me, I think, first of all into journalism which was where I had my first career, and then took me absolutely naturally into history, which is always really asking the question: what was here before this moment and what was here before that?

And what has been so illuminating for me as a historian in my life is to find that the further back I go in time, the more extraordinary the lives of people are and the less they are recorded. So when you look at medieval women or you look, even if you go… I mean my book goes right back to the Invasion of England by William of Normandy in 1066. So we’re really going back to a time that very few people know very much about. And when you look at women’s lives then, you see very little differentiation between men’s lives and women’s lives and very little differentiation in the rewards and also the problems they faced. Because you have to be a very sophisticated society with a lot of surplus wealth and the need to make and spend a lot of surplus wealth to get a big differentiation between what men and women do in their everyday life, and that’s when you start seeing the development of women as consumers and men as producers. But before then, what you see is a real survival struggle in which nobody has any time for believing that women can’t do things or that they don’t want to do things. Everybody’s absolutely committed to doing everything.

AA: That really is fascinating. And I have to say, just as a personal note, as I told you a bit ago before we started our conversation, my journey into this and into this podcast was experiences of personal pain within patriarchy. But for me, as someone who studied history also, I had just this compulsion: I had to know how patriarchy started. In order to understand my life, I needed to know context. And so that’s what propelled me on this entire feminist awakening that I’ve had. And then my desire to share it with others is: I truly don’t think we can understand ourselves and the world in which we live unless we understand what came before and how we got to where we are.

So I very much relate to that and appreciate so much your work as a historian. I think it’s critically important. It’s not just fascinating—it is fascinating and it’s fun—it’s also critically important in an understanding ourselves. So thank you for that work.

PG: It’s my life’s work. It’s Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History. My history book is the most important book I think I’ve ever written. There are other books that are more fun to read. There are other books that were more enjoyable to write though for sure. Everything else was quicker to write, but this took 10 years and nobody, in a way, not many people are in a position to be able to write it. If you are in an academic university, if you’re in an institution, you cannot take 10 years out of your career to write a book that has, at that time, no publisher. You’ve got to be self-funded and very satisfactorily self-funded to start on something that’s going to take years and years of your life.

And the other thing about academic historians is that the way we organize the teaching and the learning of history these days in our universities is that you are in a period. So if you’re a medieval historian, you write about the medieval period and there are some wonderful books about the medieval period, but they don’t make the comparison between the medieval woman and the woman in the 1920. And if you want to know anything about how change happens and how women make change and how women progress through time and get pushed back, you’ve got to have a long view. And we long views are not fashionable in history studies today. So at one level, I always feel a bit uncomfortable that I’m writing history and saying, this is a history book and I’m not in place at a university. But if I was in place at a university, I would never have been allowed to write this book.

AA: Hmm, that’s so interesting. I mean, you earned the credentials, right? You have your place very well secured in the academy as well, and the skills probably that you acquired within the academy. Is that true? Or like even doing the research in primary sources? That would be hard for a person who hasn’t had any training to be able to know where to start and how to do that.

PG: Absolutely. That’s what my PhD taught me. So when I finished my PhD, I was planning on going into university and being a university lecturer, teacher, hopefully rising up through the ranks. But it happened to coincide with a moment when our Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, had cut the funding to universities so much that there were no new posts available for anyone at all. And it was at that point where I was trying to work out what I would do with my life that I wrote just for fun, my first novel. And when it was published after an auction of five publishers in the UK and three publishers in the US, I went “oh, I’ll do this for a bit.” I mean, it was never a career plan. I thought, I’ll do this for a bit and, you know, wait until the universities open up again. And by the time they did open up, I was absolutely committed to the life I have, which is completely satisfying to me in terms of half of my life is research and half of my life is writing and it’s a joy.

AA: Oh, that’s incredibly inspiring. Thank you for sharing kind of behind the scenes a little bit. That’s so fascinating to know. Let’s turn to the book now, and I think it’s, it’s so interesting to know also that the first edition came out in 2023. You wrote this book, Normal Women—and it’s a fabulous read for all genders in all ages—but now you’ve just released a brand-new version that is tailored for young adults and specifically young women. So can you tell us why you felt it was particularly important to be addressing young women? And then my second question is, why the pivot away from novels to write nonfiction?

PG: I’ve not really pivoted away from novels because I’m publishing a novel this year. I continued to write novels all the way through the time I was researching and writing the nonfiction. But it just seemed to me that nobody was going to write this book and that the book needed to be written. And then it seemed to me very, very powerfully that young women who in the UK certainly, and I believe in the States also, we are in the grip of a crisis of mental illness and I think unhappiness for young women. And that seems to me to entirely not come out of the usual bugbear—you know, social media or mobile phones. I think it comes out of the expectations that society is putting upon young women. And when society puts very, very demanding expectations on women, we see a high proportion of the women who cannot bear this, who cannot conform to this very, very narrow window of how they’re supposed to present themselves.

That leads very, very often to illness and to mental illness. And you see it in the 1850s when the demands of women to be ladylike and to be quiet and demure and modest, and the restrictions upon their movement, certainly upon their ability to earn a living, certainly upon their ability to enjoy sex, to even enjoy food. The restrictions are so strong by this very, very demanding patriarchal society that that is when women take to their bed and have fainting fits and have epileptic fits and become famous for hysteria. And I think we’re seeing a version of that in the world today where the requirements on women’s appearance and their manners and their decorum and their self-discipline—particularly around things like food and sexuality—it’s so relentless that I honestly think there’s a good proportion of young women who simply don’t want to grow up into be women, and they are starving themselves and they’re hurting themselves in the hopes of avoiding that.

AA: Wow. That’s really powerful. And again, I do have to say how it resonates with my own experience to be struggling in my personal life and the amount of comfort that I derived once I started studying women’s history from exactly what you’re saying. Like this is not new. It’s happened before. It’s structural. It meant that the problem wasn’t me, that I wasn’t crazy. And it also gave me this like access to other women throughout time who had struggled in similar ways. And that solidarity was incredibly heartening for me. And so I think like your strategy to combat this with a work of history, some people might not connect those two dots, but I sure do and I know our listeners really do as well.

PG: I think second wave feminists used to have the slogan, ‘the personal is political’. I knew that, but it’s never been as vivid for me as when I’ve been looking at how modern women are responding to the increased politicization of their lives and the increased demands made upon them. And then now when you find that how to be a woman is increasingly limited, increasingly structured again. So you know, women who want to love other women, they have to define themselves in…you can’t just go like: I like this person. You have to say, “I’m a lesbian.” You have to sort of declare yourself and identify yourself and to find yourself; and that’s an identity that you’re supposed to keep for the rest of your life. Or at any rate, acknowledge that experience for the rest of your life. There’s no freedom in it for experimentation. There’s no freedom in the way we say how women should be, which means that we aren’t free to try things and choose them or try them for a while or not choose them or go in a totally other different direction.

When I was a young woman, there was a phrase which described boyish girls. We were called ‘tomboys’. I was a tomboy. And now you’d be talking to somebody about whether they want to change their gender or you’d be telling them they’re not allowed to change their gender. The restriction upon what is considered normal behavior is, I think, increasingly overbearing. And that’s one of the reasons why I called the book Normal Women, because inside this book called Normal Women is a range, a complete range of all of the behaviors and all of the activities that I found in history done by people who called themselves women. And that’s good enough for me. They get into the book if they call themselves women.

There’s no freedom in the way we say how women should be, which means that we aren’t free to try things and choose them or try them for a while or not choose them or go in a totally other different direction.

AA: I love it. Well, that’s perfect because that was going to be my next question is what does the term ‘normal women’ mean? So you’ve answered it beautifully already. That’s lovely.

PG: It’s also a sort of campaigning term because it says that what you choose to do as a woman defines what normality is. You do not de-normalized yourself. Do not pathologize yourself. Do not say normal women are like this, but I am weird, or I am queer, or I am ill, or anything that doesn’t seem to fit with you. Your normality is your normality.

AA: Hmm. Powerful. Well, let’s start digging into the history. And again, this is just so incredibly fascinating and surprisingly relevant. It’s just unbelievable. But you start way back in 1066, which American listeners might not know what a significant date that is, but I’m pretty sure every British child grows up knowing the date 1066. It’s the Norman Invasion of England when, and I’ll quote your book: “a massive army of 7,000 soldiers sailed across the English Channel, landed near Hastings on the south coast of England, fought a battle under the command of William, Duke of Normandy, killed the English king, Harold, and defeated the English army.” And this led to what you refer to as a “doomsday”, not just for the English, but specifically for English women. And never in my life have I ever thought about the Battle of Hastings and the invasion in terms of what it meant for women. So could you tell us the whole story? What was life like for medieval English women before this invasion, and how did it change after?

PG: Well, English women before the invasion were living in the society which was determined by their tribe or their nation. There were Anglo-Saxons, and Anglo-Saxons were quite—it’s an anachronistic word, but they were quite democratic. There were kings, but they were advised by a council, and women were admitted to the council, and women could inherit the throne. So you could be a ruling queen in the Anglo-Saxon period. The law determined that women could divorce unsatisfactory husbands. They could inherit their lands. They could inherit from their mothers or from their sisters, so you could see lands being passed down the female line. And they could hold land and fortunes in their own right. So you had, relatively speaking, an egalitarian society between men and women.

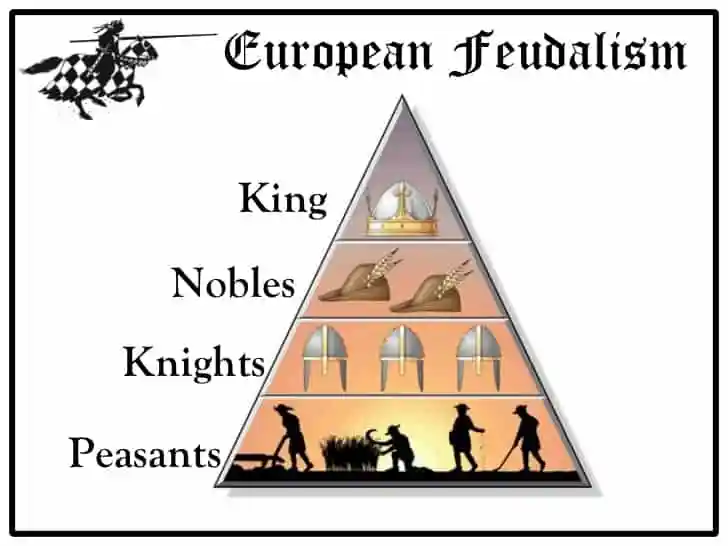

And then when you have the invasion of the Normans…Yes, every child in England knows, I hope every child knows that 1066, the Norman Army comes in. But what nobody has ever written about or thought about as far as I know, is the fact that what you put in, in this relatively egalitarian society is an upper class of invading men. They are soldiers. It’s a military invasion that is not a migration. They don’t come with wives and children. They just come in as men. And of course, the way they put their discipline on the country is to introduce feudalism in which the lower people become slaves, above them is serfs, above them is degrees of peasantry, then yeomen, then knights, then lords, then the king. And if you are religious, above the king, various orders of angels, and finally God.

So you’ve got this massive concept of a society, which is very, very pyramid, very, very structured. And nowhere on that pyramid will you ever see—if you look at a kid’s drawing of it in a history book—nowhere are there women. There is no law that covers women. Women are not mentioned in the law. Women have no rights. Now they can own nothing. If their father chooses to leave them something, it becomes their husband’s own marriage. And if they want to trade on their own, they have to get permission from the husband and they have to get permission from the council where they want to trade. They have to get a license to trade, and then they’re called a ‘feme sole’, and that’s a woman on her own.

So the only women who own anything in pure feudalism, strictly applied, is the women who have been given permission by their husbands or fathers. And that permission could be rescinded and the property taken off them at any time. Of course, I mean the great joy of why this book is I find very uplifting and not intensely depressing is that almost the moment that that law becomes to be applied, women start to find the loopholes in it and start to work around it. So because the country depends upon the skills and the labor and the fortunes of women, women just carry on owning things and carry on trading. And they only get into trouble when they come up against a man who chooses to exert his rights. And then they find that an abusive husband, for instance, literally owns everything and if they leave him, they have to leave their children and everything they’ve ever earned as well. And he has legal rights to beat them. He’s allowed to use what’s called ‘reasonable force’. And the laws about male sexual rights over wives are not repealed in Britain till the 1960s, and those are Norman laws and they go on for 900 years. It’s extraordinary.

AA: And we inherited those laws in the United States also through the laws of coverture, right? They became the English Common Law and then our laws. I am sure you know this, but state by state, our laws against domestic violence weren’t all repealed until the 1990s here, like seventies, eighties, and nineties. There was no such thing as marital rape in all 50 states until 1993. It’s absolutely appalling, but it’s so fascinating to know that that’s where it comes from, that it came from the Normans and that that’s where the English got it, and that it was egalitarian before. That is just mind blowing.

You write also specifically on this topic of domestic violence. You write that historians have found records of rape from 1208 to 1321, and they show that only 21% of men accused of rape were found guilty. So reading that or hearing it right now, 21% sounds really low to me, but you make a comparison to England today. Can you tell us about that comparison?

PG: I mean, unbelievably in England today of the men brought to court and accused of rape, 2% are successfully prosecuted and found guilty. And when you think that in Elizabethan England in the 1500s with no professional police force, with no detectives, with no forensics, with no rape centers where you can go and report, there was a higher conviction rate than there is today. I mean, it beggars belief.

Some of it is explained by the fact that a woman couldn’t take a man to court on her word alone. So she’d only get a man to court if she had witnesses very, very soon after the event, or witnesses at the time. So only the most extraordinary, strongest cases go to court. But then the difference between then and now, where it’s also true that only the strongest cases go to court, is that it was assumed that say a nun or a virgin would not have consented. Whereas in our society today, I’m sorry to say that the easiest and most successful defense for an accused rapist is to say that there was consent or miscommunication or that he thought that… and that’s when you get this whole phrase, which I absolutely hate, which is ‘he said, she said’. And like, it’s a complete lack of application of the words. Rape is never an argument. It’s never a question of the man says he didn’t rape and the woman says he did, and that those two statements are of equal worth.

AA: Mm-hmm.

PG: One is a victim statement and a witness statement, and one is a defendant’s statement. And we don’t normally say that a defendant’s word—”I did not steal that. It just fell into my pocket.”—is equal value to the person who says, “You just came into my bank and robbed me of that.” We don’t normally assume these are in any way equal, except when it’s a man’s word against a woman’s word in a rape case.

AA: Mm-hmm. Could you remind us also, were women even allowed to testify in court as witnesses? Were they able to be heard? Were they able to be on juries?

PG: No, they’re not on juries. This is an all-male court and extraordinarily, there are a lot of women judges because if you are an owner of land and a noble woman, then you often have your own court, which is your own private court where you would sit in judgment even after the Normans.

That’s the case, but women have no word in the law, so a woman cannot be a witness…except on the many, many occasions where they need a woman to be a witness and then they bring a woman in and they believe it for the occasion. And that’s what I mean, that you start with this really strict law which excludes women from all privilege and all opportunity, and immediately women squeeze in to the gaps because you can’t run a society without women.

AA: Yeah, true. True.

PG: Even if you don’t pay them, or you don’t give them equal opportunity or protection under the law, you cannot run a society legally, civilly, or a business without women working in it. And that becomes tremendously apparent. So with the best will in the world, they cannot exclude women from the law courts where women end up giving witnesses. But what they do and what we still do is discount women’s word.

AA: Mm-hmm. You also write that in the early 1300s, English women received equal pay for equal work. And that’s also something that has just backslid since through the centuries, right? So what are some of the factors that led to this regression and what did women do about it back then? And are there any applications that we could make today?

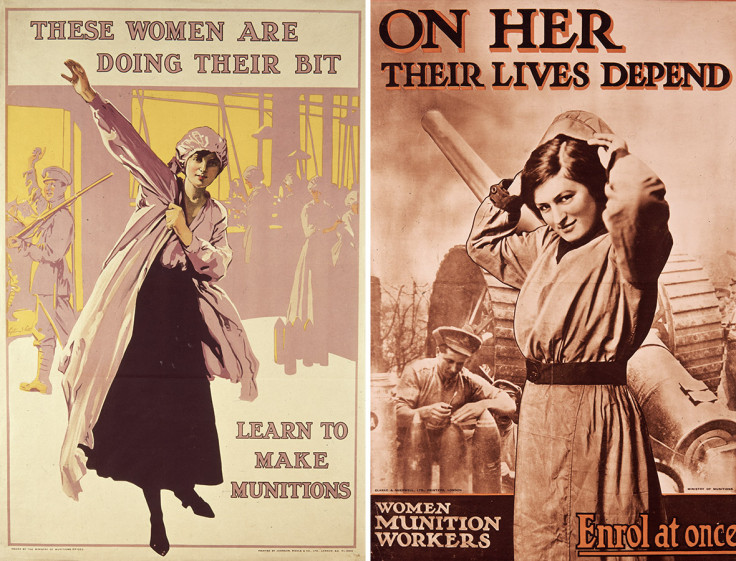

PG: The greatest lesson of it is that when a society is in crisis and it needs women to work, women’s wages improve, women’s opportunities improve, their education improves, and they get good jobs, and they get good pay. So when they’re needed, society pays them well. When they’re not essential or indeed, when society would like them to withdraw from the labor market in order to give the jobs to men, that’s when you see women’s pay really dive. So for example, at the 14-18 war, there’s a universal conscription of men. So men have to go to war, have to go into the services unless they have medical conditions which keeps them at home. And so you have a desperate demand for women, especially to work in munitions industries, which is a new industry of course, because the country is at war. So women literally answered the call mostly from patriotism. There’s no conscription then. And they go into these industries and they get paid quite well. And in some instances they get paid the equal of the men who are invalid and doing the jobs, or they get paid the equal of the rate, the men’s rate pre-war.

But when the war is over, the government literally says women have to leave the jobs because the returning soldiers have to come back into jobs to reward them for their service in the trenches. And there’s a real pressure on women to get out of work and to go back to the home and all of the advertising and all of the newspaper articles and a lot of letters by women about women say a decent woman wouldn’t work when her husband was home. No decent woman would take a man’s job when these are returning soldiers.

So what you see is that when society needs working women, it pays them. And the reason that in the 14th century there’s this sudden, glorious, brief moment where women are on equal pay is because there’d just been the Black Death. There’d just been this terrific plague, which killed so many laborers and so many workers that literally farms were standing empty. People say that there were cows in the fields mooing because they hadn’t been milked. Crops stood in the fields and nobody could get them in. So the country had already lost about, in some cases, 40%. In villages, you would have a 40% death rate. So literally the whole country just became a different place altogether and it became a place where absolutely everyone who could work had to work in order to survive.

And in those circumstances, the government didn’t collect tax, the landlords didn’t collect rent, and everybody paid the laborers to work or paid them in food because there was this desperate need to have people out in the fields making food for the rest of the country. That lasts about two generations. It’s been 50 years, it’s all over, and you start getting to the period of Elizabeth the First and a restrictive laws which rule that women will not be paid more than a maximum wage in an attempt to keep wages down.

AA: It’s fascinating. My only point of reference for this was after the World Wars, when the same thing happened, right? Women were recruited to do work and paid, and as soon as the men came home, they were kicked back to the home.

PG: And that happens at every time of crisis. So when there’s a massive slump, women are the first to be let go. And when there’s a boom, women are invited back to work. And not only do you see the difference in wages, but you see this especially in the modern world. So when society does not want or need women in the workplace, there’s a real sort of chorus of advice which says that children will be horribly neglected, will grow up really badly unless the mothers are home looking after them. And that only one parent can give a mother’s love and that’s a mother. And a father should be out there earning up the wages and the woman should be home.

So typically in the 1950s, you get this real elevation of the ‘nuclear family’ and all of the advertising and all of the propaganda about the family is basically to reassure women that they should be at home and that being out at work is actually bad for them, bad for their husband, and bad for their children. And then when you get a increasing boom in the economy, you get the reverse. So everybody’s then saying that women who stay home with their children are wasting their education. They’re not good mothers. They’re over mothering their, you know, damaging their children’s prospects because their children should be out there socializing and learning how to work. Because what we need is lots of eager workers.

It’s very transparent and, you know, good luck with dismantling the patriarchy but I think that to me, after this amount of reading and thinking, I think that capitalism is absolutely a joint project with patriarchy and the two depend upon each other, and that we are never going to free women from the demands that society puts on them until we put some controls over capitalism’s ability to tell us what to do.

AA: Yeah. That’s fascinating. Thank you for making that connection so clearly that’s something that I think is a more of an advanced concept. As you know, we’re kind of going through the history and figuring out how patriarchy was established and all of the religious factors and how it intersects with race and how it intersects with class. But the intersection with capitalism is something that can sometimes be harder to see. Or rather, I think we take it so for granted, we take capitalism so for granted, at least in the United States, that it’s taken me a longer time to see that link, even though I’ve read it in the literature. I’m starting to understand it now.

PG: I think the understanding of it being sort of accepted as almost biological that men be paid more than women, and that that is part of the nature of men and women. That’s where you really see capitalism and patriarchy coming together in a diabolical marriage of their interests, which mean that the poor are always with us and the poorest of the poor are always women.

AA: Okay, shifting gears. One other thing that stood out to me was from the 16th century, and this stood out to me because it was different from what I was expecting. You said that in the 16th century it started to be taught that women were weaker, with new translations of scripture suddenly claiming that women were the, the ‘weaker vessel’. And then this was an idea that men quickly adopted and began to teach and preach.

But for me, I had kind of pictured that women being considered the weaker vessel had just been an unbroken line straight from Adam and Eve for as long as there were Judeo-Christian people, that that had been the concept all the way through. So it was surprising to me to see that that was a relatively recent construct. Can you talk about that a little bit?

the poor are always with us and the poorest of the poor are always women

PG: Yeah. I mean, the phrase ‘weaker vessel’ is invented by William Tyndale in his translation of the Bible. The previous version by John Wycliffe talks about women’s ‘weakness of spirit’, but only in the sense that we are all that men and women are weak of spirit. The phrase ‘weaker vessel’ is entirely invented by Tyndale and it becomes central to religious teaching on women for the next…I mean, right the way up to the ordination of women.

And I think seeing it in a literary sense as a metaphor as well, is really, really interesting. It’s a weak vessel so I say in the book, I have an image in my mind of a sort of leaky watering pot. But you know, it is the idea of a woman as a vessel, that she holds the seed of a man and she holds the baby. That that is her, in a sense, function. That is her most important function. She is a vessel for the next generation, but she’s not a very good vessel. She’s a weak vessel, she’s a leaky vessel. And that really ties in with the sort of misogynistic descriptions of women as being moist and damp and leaky and prone to crying and prone to hysteria, and of course prone to menstruating. And fluid in the sense that you never quite know what state a woman is in. And that what is normal and right is a sort of completely waterproof man who is steady state. And the idea that normality should be a change in condition of hormones and physique and temperament that’s regarded as other.

So I think the weak vessel, it has extraordinary power as an image, as well as a phrase which gets taken up into the Bible and then becomes used without further question. In all subsequent translations of the Bible you will find weak vessel, and you will find ‘weak vessel’ in the dictionary today, meaning ‘a woman’. It just becomes a complete transposition of this completely invented phrase. Doesn’t come from the Greek, doesn’t come from the Latin. It’s Tyndale who invents it, and then it becomes a way of describing a woman, which is of course derogatory.

AA: Yeah, yeah.

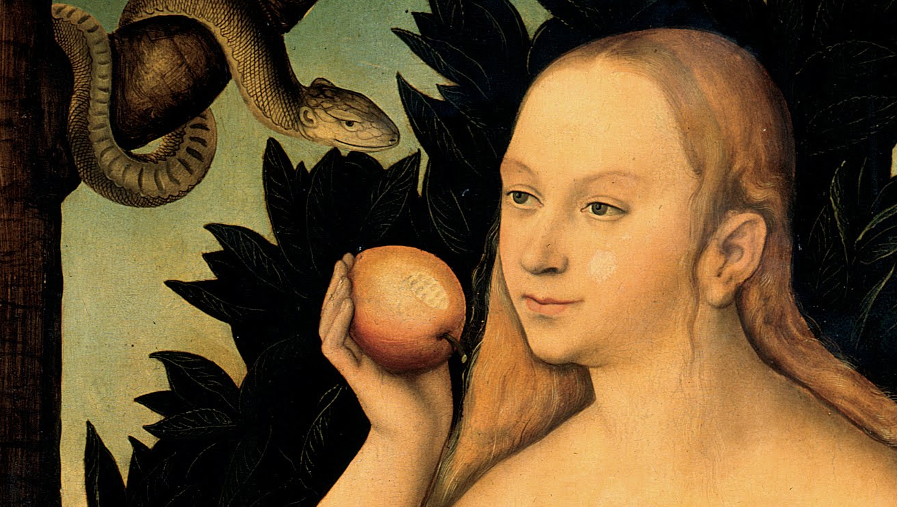

PG: Of course, you are absolutely right that you do have a tradition from Adam and Eve of the idea of a woman being… I mean, the thing I love the most about it is flawed in many ways, but one of the ways is gossipy. Her first mistake is being chatty with the serpent. So they’re there in the garden and like everyone else says, all these beasts and man has dominion over all of them. But Eve has this little conversation with the serpent, and that gives the serpent the chance to tempt her, and that gives Eve the idea of tempting Adam and Adam succumbing to temptation is blamed so thoroughly on Eve. She blames it on the serpent. And there you have the beginning of evil in the world altogether. And it starts with a woman not able to restrain her temptation to chatter.

And that absolutely goes forward to the present day. You know, we still have quite competent biologists and sociologists and child development people talking about girls greater fluency in language and boys greater ability in sports. And never do they stop and go, “Is this because people talk more to girls and encourage boys to run around after balls? Or is this innate?” And the question of innate or enabled is of interest. But all the reading I’ve done is of interest mainly to feminists who are saying, “Actually we are quite capable of judging spaces. We are quite capable of undergoing arduous training. We are quite capable intellectually.” It’s not that we are some chatty, ill-disciplined, uncontrolled, thoughtless woman in the garden of Eden. It’s a powerful image that extends to the present day, even in present day scientific studies.

AA: It does. I’ve read some studies even recently that say that if women and men in a group, if they track it, if scientists are studying this and they track it: women and men speak equally—50% of the time women speak—but that men perceive them as speaking a much, much higher percent of the time because that’s their expectation. Because of this misogynistic trope of like women that won’t shut up. Women talk too much. And so those are the lenses through which they see women talking is like, ‘oh, stop talking’. And then the men are shocked to look at the transcript and see that women were speaking exactly half the time.

So to your point, I mean, it’s just the expectations that we have and the culture that we’re raised in that has been there for… almost it seems time immemorial. But I did really appreciate you pointing that out, that that specific phrasing of the ‘weaker vessel’ didn’t come all the way from Bible, but just from one guy.

PG: It’s in the Bible now. Yeah, but it’s in there because William Tyndale thought of it.

AA: Yes. Fascinating. So interesting. Okay, this is a completely different topic, but you brought it up a little bit earlier. You talked about queer women, and in the book, if I’m not mistaken, it seems that across English history, really until the 20th century, women could more freely love whom they loved and even marry one another. And so I was wondering if you’d be willing to speak a bit about what we might today refer to as LGBTQ women across English history. What kind of lives did they lead? What rights did they have? And then for our American listeners, could you bring us up to speed on the rights of queer English women today?

PG: Okay, so I’m a historian. I’m not a sociologist. So with that preface, I mean, what’s fascinating to me was to discover that the idea both of sexual fluidity and of what I call in the book, ‘women loving women’—because it’s much easier to see women’s deep affection for each other and women’s spending time with each other and women preferring other women to the company of men—that’s easier to trace in the historical record than anything about women’s sexual practices, which we only know about when they’re forbidden because that’s the only time that they get written down because that’s when they enter the law. So we know a bit about women’s sexual practices in the medieval convents and nunneries because some sexual practices are explicitly forbidden by men and sometimes observed by inspecting bishops. And that’s the big feature of Henry the VIII’s Reformation when there are a lot of inspections, very critical inspections of nunneries, and one of the things they’re looking out for is for nuns being intimate together. But that would include sharing a bed, and in the medieval world, as in many instances in the modern world also, sharing a bed did not indicate a sexual relationship. It just indicated that there weren’t very many beds and people literally shared with each other.

So something like lesbian history… it’s very, very difficult to be sure what you are observing, even when you have a report of it. But what I am sure about is that there is a great deal of intimacy, physical and emotional between women who are single or married to men or widowed from male husbands. And in addition to that, it was widely known. It was commonplace throughout society that women would choose the company of other women in all sorts of circumstances. And in the 18th century, in fact, there is a phrase widely used in all the journalism, which is ‘female husband’, and that is a woman who marries another woman in church—because that’s the only place you can get married then. And so you have Protestant Clergymen and Vicars, consciously and aware, marrying women couples, female couples.

One of the women who we know was a sexually active lesbian, went by the name of Gentleman Jack. And there’s a BBC drama series based on her diaries, a fictionalized version, a dramatized version of her diaries. And she and her principal lover, they consider themselves married. They go into, I think, Yorkminster and they swear to each other and they take communion together, and they regard that as a binding marriage. But in addition to that, there were women of all classes going to their local church, having the bands called, having their marriage recorded in the register, and that went on widely up until the middle of the 19th century. And extraordinary to me, it’s only round about 1920, 1930 that there’s a real anxiety about what is now called lesbianism. And there’s a real desire to pass laws making it criminal and enhance the laws, make the laws more oppressive against male homosexuals. And that spills through into society generally.

And so thereafter—unless women are in such a financial state or in such a social state that they can manage the notoriety—the whole business of women loving and preferring women becomes very much more discreet. So discreet that you can’t now…up until I think last year a woman could not marry a woman in a Church of England church. And some years ago we invented a new form, which was the ‘civil partnership’ whereby a woman could marry but not in church. And we’ve just got to the point now that you can get your marriage blessed in church. And this is announced by the Church of England with a great deal of acclaim. And well done, I have to say rather patronizingly, well done. But clearly they have no idea of their own history, which is that they were marrying women in church for like 500 years and nobody minded about it at all.

AA: Yeah, that’s the crazy thing to me is it’s presented as if it’s this very, very recent development within society and everybody is all up in arms about it. And it’s like it’s never happened before. And that’s why it’s so important to know, again, the context. It’s almost silly when you see the context. You just think, ‘Oh, some of this could have been avoided if people had just understood sooner’.

PG: But this speaks to the title, that it’s the normality of these things that we now get so agitated about and start saying are so controversial. Go back 300 years and nobody would turn their hair.

AA: Yeah. Isn’t that so interesting? Okay, so shifting forward in history, you talk about the 1930s and you examine normal women’s role in the rise of European fascism, and you write that “10% of the British Union of Fascist Parliamentary candidates were women.” And then there’s this clever note in the margin—one of many throughout the book—but this one tells us that the number of candidates, 10%, was more than any other party until the 1980s. Can you tell us why fascism appealed to so many British women in the 1930s?

PG: Yes, I can, but before I do I’d have to say: we always have to be terribly careful to not fall into the trap of thinking that there is such a thing as women’s nature which is in any way unlike men’s nature. I believe that people exist, their consciousness exists across a spectrum of beliefs. So women are no more attuned to nature or intuitive or good mothers or loving or kind than they are murderous or criminal or psychopathic. Most of these characteristics are not gendered. Therefore, there is absolutely no reason why as a woman you shouldn’t be as keen on fascism as your neighborhood fascist man. I mean, I wish it were not the case, but I think it is the case that these are issues for human beings. They’re not issues particularly for one sex or another.

In the 1930s, the appeal of the British Union of Fascists to women—who were, I think, in the process of emerging from a very oppressive society. I know it’s just post-Edwardian, but we’re really talking about the long impact of Victorian oppression. So in the 1920s and the 1930s, you’ve got women starting…you know, they’re getting the vote. They’re starting to think about themselves as having ambitions for entering professions. They are starting to enter professions. They’re starting to go into higher education in substantial numbers. They’re starting to push back against the belief that women are physically incapable of political life or intellectual life. So there’s a big kind of opening up there on how are women to be and the British Union of Fascists… there’s this really, really brilliant appeal, which is that it offers two completely contradictory pictures of what women would be like under fascism. On the one hand, it really boosts the motherland and being a good mother and having dozens of children being what we’d now say as a ‘trad wife’. Go home. You will have a strong man in government to run your country. You will have a strong husband to look after you. And one of the timeless appeals of fascism is that the society will be so controlled that if you accept the control, if you are obedient, you’ll be safe.

So that’s one sort of thing, which means that a certain sort of woman goes like, “Yes, I’m voting for this.” And the other is also the timeless appeal of uniforms and dressing up a militaristic life. A lot of women entered the British Union of Fascists from their war work when they had been in uniform, and they had been auxiliary workers in the 14-18 war. And I mean, some of these women had awards of extraordinary courage and effectiveness. So Toupie Lowther famously ran her own ambulance unit behind the trenches of the 14-18 war. The British government did not want her service. The French government and the Belgian government accepted it. And so she was a very, very typical woman who—having been literally in a militaristic organization supporting an army at war, in the most extraordinary danger, in her own designed uniform in her own ambulance unit—post-war, the British Union of Fascists really spoke to her when they said, “We want women to fight our course. We want women as stormtroopers. We want women to be side to side with their comrades.” Really a profound appeal for women who wanted to be active and powerful and agents of their own lives.

So you get this complete contradiction, which is possible because fascists, then and now, are not strong on logic. So you get this complete contradiction of what is society going to be like, and apparently it’s going to be open to two completely opposing sorts of female behavior.

AA: Hmm. That’s so interesting. I mean, that for me the mark of a great historian also: you can see the nuance in it, right? And can see from the point of view of the person. ‘Well, why does it make sense to them?’ What is it that is appealing to them that’s leading a person toward an ideology that in… well, I was going to say in retrospect, sadly, that’s not the case, at least in America right now. We are heading straight into fascism right now. But in any case, it’s really important to understand what the appeal is. And that makes a lot of sense.

PG: And I think if you are, as I am, writing a history about women; I’m not writing a history about left-wing women. I’m not even writing a history about feminists. I’m writing a history about women who make different choices in different societies according to what makes sense to them. And it’s obligatory on me to be broad-minded about those choices. And it’s good if I can be compassionate as well. So I don’t just write about the women who I agree with. I try and write about them all.

AA: Yes. I appreciate that and respect that so very much. While we’re on this topic of fascism in the 1930s, I was so struck by the Battle of Cable Street, so I was wondering if you could tell us about that? Because it also was just this example of women being so courageous and fighting against the circumstances that they found themselves in.

Fascists, then and now, are not strong on logic.

PG: Yes. And you know, that’s part of a great tradition in England for sure, of women taking to the streets and being violent against mostly agents of change, and particularly people who are trying to change the rules of the marketplace. So there’s a long, long tradition—which goes back literally to the Norman Invasion—of landlords enclosing fields and enclosing forests and keeping working people out of where they grow their food and where they hunt. That’s very, very powerful for us in a relatively small country. I don’t know the comparison of your country, but certainly from the Norman Invasion onwards, the Norman lords define huge areas of territory as just for their hunting, and no one else is allowed to go and hunt there. And what you see constantly is women using the laws blindness to them.

So you can’t prosecute women really, up until about the 18th century. People don’t prosecute women because they’re under the control of their husbands. So if they do something really terrible, you prosecute the husband. What you don’t do is you don’t prosecute a whole village of men because the whole village of women have gone out and broken down fences, or they’ve had a riot in the marketplace and set the price of bread at a price that they can afford. So there’s a real pushback really, really powerfully powered by women. There’s a point in the book where I say, “if there is such a thing as women’s work, it is the food riot.” There’s real pushback against inflated prices for food, which is always led, always, always, always led and staffed by women fighting to keep prices at the level that they can afford. There’s a couple of reasons for that. One is that women are the big traders, food traders, they’re the ones in the marketplace. They know what the price of food ought to be. They know when someone isn’t bringing their crop to market because where they normally would be the guy’s selling it to London or he is selling it abroad. So they know that’s going on and they are there in large numbers because it’s market day.

So you have really price setting, price controlling riots, which happen in the 18th century. There’s one every day in somewhere England in one particular year. It’s a massive phenomenon. And I think Cable Street, which is a riot by the inhabitants of a poor area, very much a Jewish area of London, against the march of the British Union of Fascists who deliberately route their march through Cable Street in order to frighten and distress and, if there is resistance, in order to have a fight right in the heart of poor and working class people and immigrant people. And they don’t get through, I mean, the police to the shame of the government—a labor government at that—I think the police defend the march and agree the route through this very provocative area. And so it’s the police who end up doing the fighting because the fascists decide it’s too rough. Which is also not untypical of the right? The right wing who only want to put the uniform on at the weekend. They don’t really want to losing battle.

So there’s a small riot in Cable Street with old ladies chucking milk bottles from their windows on the first floors. And some very, very brave women who are literally in the front line. And there were more stories about it than I could quote, but there’s a wonderful story about a young Jewish woman who was taken into the police station and one of the guys they already arrested reports her looking out the police constable when he rips her shirt open and she says, “I’m not afraid of you.” I mean, I wish every woman in the world could say that.

AA: Mm-hmm. It brings tears to my eyes. Just that incredible, incredible courage. It’s so inspiring. Well, I am sad to see that the hour has already ticked by. I have one more topic to ask you about. If you could talk about one more thing quickly, and then I’ll have you share some takeaways as we close. But I was wondering if you could talk about abortion? You discussed the legality and the reality of abortions in the 1920s and thirties.

PG: I mean, the history of abortion is another history which we have lost and which the consequences of not knowing the history of it are very, very material in the present day.

So there was no objection by the church, and therefore no objection by any authorities for abortion up until the time of quickening. So when a woman felt a baby move, that was considered to be the moment at which the baby had a soul, and therefore abortion after that date was not allowed by the church; there would be a punishment for it. But it was a very, very minor punishment because firstly, you had to rely upon the woman to say when the baby had quickened or not. And so she could say, “No, it hadn’t.” So it was not regarded as really much of anybody else’s business. And also it was a minor offense. I mean, it was killing an embryo. They believed that a soul had come into it, but it wasn’t as bad, for instance, as infanticide.

And of course, in an earlier society, in a historical society with no reliable contraception, all the contraception was either abortifacients, taking herbs, or intruding into the womb with a knife or a needle. Or giving birth and then killing the baby. So you are on a spectrum, from our eyes, of something which we think of as having murder—infanticide—to what we think of as relatively un-criminal which is the killing of a baby before it has moved, before the mother even can be sure that she is pregnant or that she’s pregnant with a live baby. So what you have is a real vague sort of spectrum…

Up until the 19th century, no man is present at the birth of a child unless something terrible has happened. No man should be present at the birth of a child. It’s all done by women. Even the physicians are not in the birth chamber. This is all done by midwives and women physicians. So it’s very much a sort of private world and it very much runs to its own private rules. So the women who are midwives would be the women who supply abortifacients. There isn’t a medicalized concept of birth. There isn’t a real concept of birth, which goes like: at this point you can intervene, at this point you can’t. So infanticide is extremely common and in the 1920s you start getting, since men are involved in it, you can have a massive black market for all sorts of pills which cause abortions, but which are sold as bringing on bleeding. And everybody knows that means ending pregnancy and nobody has anything much to do about that.

And then you start to have the Royal College of Physicians and doctors consciously moving against women healers, women midwives, unlicensed midwives, and those women who are as part of their trade as midwives, supplying herbs and also performing surgical abortions. And that becomes very easy to prosecute because when it goes wrong and the woman is desperately ill after a surgical abortion that’s gone wrong, she turns up in the hospital and that’s when they try and save a life and then immediately prosecute her for murder straight after.

So in a sense, the problem is when what was regarded as a women’s health issue —dealt with entirely by women who knew what they were talking about—moves into the area of men’s doctors speaking about women’s health, and then lawyers, male lawyers, speaking about women’s health. And now we’re in a situation where we literally have a legal abortion in my country allowed by the House of Commons, Parliament, which is predominantly male. And you know, my feeling about it actually is that it is the mother’s issue. It’s her problem. We know that in this country abortion is very much related to poverty. It’s not about unsafe sex and young women. The most women who are going for abortion are married women who cannot afford another child. Often they’ve got two or three already and they cannot afford another child. That seems to me to be nothing about control of female sexuality. That seems to me everything about not providing well enough for our families.

AA: Mm-hmm. Yes. That’s a fascinating and such an important history. Thank you so much for writing about it and talking about it today.

Okay, the last question I want to ask you is this. In the final chapter of your book, you write with real confidence. You write, quote, “in the future there will be infinite ways to be a woman, all of them normal, and a greater acceptance of people identifying themselves as women or even rejecting all labels.” Can you tell us a little bit about what prompts that vision of the future and why you’re so optimistic about it?

PG: Well, this is the end of the book, which is designed for younger readers. It doesn’t have to be exclusively younger readers, but it’s the abridged version of the book. And I was really conscious that, given the difficulties that I think young people of all genders face, looking at the world that they are growing up in, I didn’t really want to do a doom and gloom thing. And also it is true that during my lifetime I have seen increasing restriction on how women are expected to particularly look, but also behave. Although that includes highly sexualized behavior, that in itself is a demand upon young women that they shouldn’t have to face. So I’ve seen increasing demands put upon, particularly, young women. I’ve seen those demands be increasingly broadcast. So social media is a great powerful vector for telling young women that this sort of look is okay, and this sort of look is not, and that’s not helpful.

But I’ve also seen this extraordinary rise of people choosing how to be, even in this world which is so prescriptive. I think that there is a massive increase among young women and young men and young people who do not regard the world as divided into binary categories, as I do. And I think there is a freedom there, and I think that’s going to be more powerful than all of the forces saying, “You have got to decide if you’re a boy or a girl, and once you’ve decided that you’ve got to look like this and act like this.” I think people’s desire for individuation and their individual happiness has never been stronger. And I think that’s going to bring us to individually more freedoms and collectively a better society. I really do.

AA: Wonderful. Okay. Well, for our last bit of wisdom from you, I like to ask each of my guests at the end of the episode if there’s an action item that you would like to leave with listeners, something that we can do to make the world a better and more just place. If there’s one or two things that you could think of, what would they be?

PG: I think I’ll only think of one thing in the current climate that we’re living in, and I would ask you to only read what you know to be well researched, solidly researched. It won’t be the truth because the truth is a very slippery concept, but only read what you trust and what you’ve checked out and only forward, like, tell other people about something that you know to be true. One of the great dangers, I think, to free speech, to democracy, to even peace is the way that we are in such a hurry to amplify lies and that some of our rulers are prepared to lie to us.

AA: Hmm. Hear hear. It’s unfortunate that that even needs to be said, but it really is so important.

PG: In all of my research, I spend all my time going like, “This is a great story. I wonder if it’s true.” And it becomes second nature to a good journalist or a historian to do that. And while we are all historians of our own past and all historians of our own future, we need to do that.

AA: Yeah, absolutely. Thank you.

Well, Philippa Gregory, what an absolute honor and joy to talk with you today. I cannot recommend your book highly enough to listeners. Again, it’s called Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History. I would say both versions are fabulous, right? Like the original 2023 version, which is longer, and then this new version. Can you tell us where people can find a copy of the book and how people can find your work?

PG: You can find a copy of the book at any good bookshop or any way you choose to get your books. It’s also available as an audiobook and I read it so you get it read by me, the long version, and read by an actor, the abridged version. And also there’s a podcast which I did linked to it. So there’s all sorts of places to get hold of it. And one of the things I did when I was preparing it was the abridging; the abridged version sits very nicely alongside the longer version. So if you want to read the short version and then look over and look something up, you can do that. And I know, and I’m so proud that I know that there are a lot of mothers and daughters, and mothers and sons, and fathers and sons, and fathers and daughters who are reading alongside each other and comparing notes as they go through.

AA: Ah, fabulous. I love it. Wonderful. Well, thank you again so much Philippa Gregory for being here today.

PG: My pleasure. Thank you for having me.

These are issues for human beings.

They’re not issues particularly for one sex or another.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!