“we are our own bullies”

Amy is joined by coach Sara Fisk to unpack people pleasing behaviors, learning how women are rewarded for losing ourselves, rethinking our resources, and making more purposeful choices about when and where we people please.

Our Guest

Sara Fisk

Sara Bybee Fisk is a master-certified coach and instructor who teaches women how to overcome people-pleasing, perfectionism, and codependency. She is known for her podcast, the Ex-Good Girl Podcast, and her work with the Life Coach School. Fisk is also a former scholars coach for the Life Coach School.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: A few days ago I got a text out of the blue from a guy friend who wanted to talk about some emotionally charged topics. I did not want to have the conversation. This guy had a history of not being a good listener, and I was also really stressed by some other things that were going on for me at the time, and I was not in a great head space. So when I saw his text, I took probably ten minutes carefully crafting a reply that affirmed our friendship, but told him that I wasn’t going to engage in the conversation at that time. I sent the text and then noticed that my whole body was shaking with anxiety about how he would respond to my very polite “No.” And you know what? That wasn’t entirely unfounded. This guy replied back immediately, no ten minutes of careful wordsmithing from him, and it was the rudest, most disrespectful communication I have received in a long time. So I went into a panic and ended up soothing his feelings, telling him everything was okay, that I cared about him so much, and that we could talk about it at a later time when we saw each other in person. I was so kind. And I was so mad afterward. I had fallen into the behavior pattern that I’ve been taught since before I can even remember: keep other people happy, especially men, at all costs. I am actively trying to rewire my brain to recover from this kind of people pleasing, but sometimes I don’t quite know how, and when something comes up in the moment that I’m not prepared for, I just revert to that prior training. So, I was thrilled to discover the work of therapist Sara Fisk, who is an expert specifically in helping women to stop people pleasing, and I’m so happy to have Sara with us today. Welcome, Sara!

Sara Fisk: It is totally an honor. I am a huge fan and just so great to be here.

AA: So excited for this conversation. I wonder if we can start by having you introduce yourself to listeners personally, tell us where you’re from, tell us some of the factors in your personal life that brought you to the place that you are today.

SF: Absolutely. I live in Arizona in a suburb of Phoenix. I am technically Latina, and I say that because I also was raised in the Mormon church. And it’s interesting to come to understand later that my culture growing up was not my Mexican heritage, it was really the church that was our culture. One of the things that I have worked on lately is really feeling into that cultural background. I have five kids, I am a wife and mom, and I love those roles most of the time. I am a coach, and I came to this work a hundred percent autobiographically. I was the most complete people pleaser and codependent, perfectionist, all of the things. I really struggled to do anything that I wanted to do for myself, I felt completely lost and consumed in my roles. And I will say that a lot of the time I felt like that was good and right, but when there were a lot of issues that I looked at inside of Mormonism that just didn’t feel good to me anymore, and when I decided to leave the church, that’s when all of it came up. I was a 42-year-old woman going to church because I was afraid to tell my parents that I didn’t want to go anymore, and just felt so hemmed in on every side by other people’s expectations, by God’s expectations. And really, if I am being completely honest, when I tried to feel into “Sara, who are you? What do you want?” it didn’t feel like there was anything there. I was really just fulfilling a bunch of roles for other people all day, every day, and that really obscured anything about me that I felt really deeply connected to.

AA: Wow. Well, yeah, I’m just thinking of listeners listening to this, like, “So what did you do? What did you do next? How did you learn this stuff?” But that’s going to be the conversation today, right? Or is there more that you want to share about your story and how you got from there to where you are now?

SF: No, that is the conversation I hope we have today, because as I have now worked, I’ve been coaching for almost six and a half years, that is the story of womanhood in general.

AA: For sure.

SF: I think high-demand religion puts a unique twist on some aspects of that, but universally, if you are a woman who is raised in a Western, patriarchal, capitalist society, you are rewarded for losing yourself, overgiving, overdoing. And that actually works for a little while. You feel very rewarded. I felt very rewarded inside of Mormonism and I had that proximity to some power and influence, which is really all that Mormon women get. It felt fulfilling for me, I felt like I was doing it right, I felt like God was happy with me. And that works until it doesn’t. And that process of feeling it not work anymore and really digging inside, “Who am I? What do I want?” I think that’s pretty universal for women, no matter where and how they grow up.

AA: Mm-hmm. I think you’re right. It’s why we both do the work we do, right? Well, let’s start with the most basic definition. How do you define people pleasing?

SF: I define people pleasing as having the internal experience of not having a choice. Not having a choice to do what I want to do. I have to do what you want. I should, I ought, I must. So when I don’t have the choice to do what I want, I abandon myself and I just do what other people want. It’s this internal experience of not having a choice.

AA: I was looking at your blog the other day, which is fabulous. I highly recommend it to listeners, and I’ll have you share all of the ways that listeners can find your work at the end of the conversation. But I was looking at your blog and I even just learned so much reading what you wrote there about people pleasing being a maladaptive tendency that you develop at a young age. I was like, “Yep, yep, yep.” So, where does it come from? How does it develop over time, and why does it feel good, like you said? Because it does, sometimes. And maybe there are appropriate times for it, to be doing something that somebody else hopes for or wants to is appropriate sometimes, but sometimes it’s not. So, how do you tease those things apart?

SF: Yeah, you’re exactly right. And I just want to say with a statement that I make all the time: the problem is not that we people please, because it’s actually a part of connected, loving, safe relationships. The problem is that we don’t know how to not people please, when that is what would better serve us. And so with that statement, let’s go back to the beginning. Babies come into this world completely dependent on the big people. That’s just how this existence has been set up. And so a baby has a biologically programmed cry. They cry and someone hopefully comes and changes them, cuddles them, feeds them, helps them go to sleep, and connects with them. So before they even understand that they’re a separate human, they get this idea that “I do something and there’s a response.” And it’s hopefully a good response. So as they grow up and all those mirror neurons come online and they’re constantly scanning around, watching the faces of the big people, they start to know, “Okay, there are some things that they like and some things that they don’t like.” If you’ve ever been in a room, when a baby smiles, what does everybody do?

AA: Smile back.

SF: “Oh my gosh, she’s smiling!” And the baby’s like, “They like that.” It lights them up, they get hugs, they get cuddles. And that is as much survival based as anything else. And so then baby grows, and then there are more people who like different things and who don’t like other things, and adults respond. I remember sitting in church with my daughter and she slapped my face, as babies do when they’re learning how limbs and hands work. And I grabbed her hand and I said, “No.” And I pushed her body away from me. And what did she start to do? She cried. She dissolved into tears because I had punished her. To me, it wasn’t a punishment, I was just being a good mom. But to her little baby body, that was a punishment. My voice, my eyebrows going down into a menacing stare, and then the separating. So that’s what babies pick up. “They like this and I get rewarded, they don’t like this and I get punished.” So then there are more and more people. There are church leaders and coaches and teachers, and the school lunch ladies, and all of these little mirror neurons that are meant to be there to facilitate safety and connection, they do what they do. They pick up all of this information about how I have to behave to be safe and to feel connected, to belong.

the problem is not that we people please, because it’s actually a part of connected, loving, safe relationships. The problem is that we don’t know how to not people please

AA: So if we have to do that for survival, then how does it become maladaptive?

SF: It becomes maladaptive in some kind of sneaky ways. Because these big people, who we want to connect with and feel loved by, they also prize their own comfort over ours sometimes. So you’re at a family party and the creepy uncle wants a hug and kiss, and your mom is embarrassed because you won’t just obey, and she says, “I don’t care what you think. You get over there and you give them a hug and a kiss.” So at young ages, all of us learn “I have to stuff down this feeling of discomfort or not wanting to, and I have to do what they say so I don’t get in trouble. I have to finish the food on my plate.” That was a big rule in my house. If you served it, you ate it. So my body is telling me I’m full, and my dad is saying, “You can’t get up until you finish your food.” There are hundreds of ways that we teach young children that they have to push down their own discomfort or their own feeling of “This isn’t right, I don’t like this,” to obey. And we separate children from the sensations in their body that are meant to give them the relevant information about how to be safe and how to feel connected, and they have to opt out of feeling to obey.

AA: Mm-hmm. Because obedience does mean safety and being liked, being approved of, especially by those people that keep you safe, but also the people that you genuinely love.

SF: Exactly.

AA: That’s parents, but that’s also, like you said, church leaders or all the people in your community. And especially we talk about patriarchy, like how this is specifically gendered. Because I know all humans can fall into the people pleasing trap, we all do, but I do want to talk about how gender plays into it. And I’ll ask an obvious question, but I want you to really dig in. How does patriarchy contribute to women specifically becoming people pleasers?

SF: I mean, part of the obvious answer to this is that humans who are socialized as boys, they have some off-ramps from the purely people pleasing experience. “Boys will be boys,” their risk-taking and their authority-challenging is seen as developmentally appropriate. They’re going to be good leaders, they’re going to be important men in their field. While for girls, the behavior that is rewarded over and over and over again is being quiet, not rocking the boat, going along, being nice. So, from a very young age, because of patriarchy, we reward behavior in boys that gives them access to more freedom and more choices, and we reward behavior in girls that keeps them compliant and keeps them nice and keeps them not rocking the boat. And when you think about the history of patriarchy, so much of which I learned from you– I was born in 1973. That was the year that women could get a loan without their husband co-signing on it. So my mom, until I was born, literally had no access to financial capital unless she could get a man to agree with her, so she had to be nice, she had to not rock the boat. Her whole financial ability to exist in the world was dependent on men. And there are hundreds of laws and ways that our social structure was set up that made women dependent on men. And that meant we had to be kind, we had to be good, we had to keep our marriage, and it was never the case that a woman could just decide to get a divorce and go find a different husband. I mean, it did happen, but that would be very difficult. Where women were the disposable, replaceable gender all the time because a man held all the power.

AA: For sure. Let’s dig in. You mentioned financially, and you gave one example of that and like in the home, and I do want to touch on religious patriarchy too, just because it’s so overt. It’s so obvious. So let’s explore some things that you can trace to scripture and culture that give women the very clear message that you need to please men. This is not a subtle thing. It’s right in the doctrine for a lot of religions. What pops into your mind in that category?

SF: In our shared religious tradition, there are songs that we sing about how obeying the prophets is what will keep you safe. Hearkening to the words of men who are “chosen by God,” air quotes there, is the way to be considered righteous and good. It is in so many religions. The degree of faithfulness that you have is measured by your obedience to the laws that come from God, that come from the scriptures, that come through, if you are in a religious tradition that believes that there are men on earth who speak for God, it’s by listening to and obeying them. In Mormonism, literally the number of children that you are willing to have, the things that you are willing to endorse or not endorse. I was at BYU when a religious leader named Boyd K. Packer talked about how the enemies of the church were homosexuals, feminists and intellectuals. And in my 19-year-old mind, I was like, “Oh, those are the worst things you can be.” So I put a lot of time and energy into not understanding and being deliberately ignorant because I thought it was the right thing to do. So religious patriarchy shapes what you are allowed to believe, the questions you are allowed to ask, the position you are allowed to have, and you are rewarded for upholding the structure and the system.

AA: Mm-hmm. And that’s why it feels good, too, because if you’re a baby and then a little kid and they’re like, “These are the rules and the rules will make you happy and the rules keep you safe,” then of course you’re going to feel good keeping the rules.

SF: That’s right.

AA: I’ll say too, even just under all of it, fundamentally, and this is in the entire Judeo-Christian and the Muslim tradition, the creation story– there is so much power in the stories that people tell about where humans come from, because it tells us who we are and what God expects us to be. So the fact that in that story women learn that they were created to help men, to please men, to be an assistant and a sidekick, and really secondary to men, women learn that and so we are handed that script and we’re like, “Okay, well that’s how I’m supposed to be a good woman.” And men learn it too! Even if it’s not explicitly connected like, “See how Adam is primary, see how Eve was created to please Adam, so therefore that’s your place in the world,” they just see it everywhere. I mean, I do have compassion for men growing up who do have this expectation, which feels innate, like, “Well, we’re supposed to move to where my job is. Didn’t we all agree on this?” And they don’t even know why they have that expectation or like, “Wait, why are you doing it that way? Why are you disagreeing with me? You’re making it so hard,” because the default has been absorbed into both parties their whole lives. You know what I mean? And in some families, in some communities, in some cultures it’s more explicit than in others, but we are all swimming in that water. And it sets everybody up for a lot of frustration, and sometimes they don’t even know why. It’s just because it’s just inherent in all of that messaging. And for me, going back to those fundamental scriptures of male primacy and women’s subservience, it doesn’t get more explicit than that, I feel.

SF: That’s so true. It’s so true, and all of the things that come out from that. I’m really trying to understand my own journey through perimenopause right now. And in doing research, just realizing that every religious tradition has the teaching that women are unclean when we are menstruating or when we have just given birth. So all of the little kinds of teachings that come out of that about women being one down all the time, no matter what are natural biological processes. Yeah, you’re absolutely right.

AA: I’m wondering too, since you mentioned natural biological processes, that has me thinking about our human nature. An image that just popped into my mind is that incident where the head of soccer in Spain kissed the woman soccer player completely with no warning and without her consent, just right on the mouth. Did you watch the video of it when it actually happened?

SF: I didn’t watch the video, but I’m familiar with the story.

AA: Yeah. I watched the video and you just watch her freeze, and then she moves along and it’s not until afterwards that she’s like, “What the F?” But I want to ask you about that too, the biological component of men being bigger and stronger and our intergenerational female trauma of being attacked and raped by men. How do you think that plays into the people pleasing too?

SF: One of the things that I wish I could just put in the water so that everybody understands, especially women, is that we are not in charge of how our nervous system responds to attack or surprise. So maybe that kiss didn’t feel like an attack, but certainly it was a surprise, and our nervous system is a complex, I think of it kind of like a system of buttons and levers where they really quickly calculate “what is my best chance of surviving this incident and with my dignity intact, not damaging relationships that I know are important to my success, to my financial future?” I mean, if he’s her coach, there’s some financial tie there. What is my best chance of surviving this? And then your nervous system just picks a response. Fight, flight, freeze, or fawn, or some combination. So she froze in the moment. She had no choice over that response. And we so often blame like, “Well, if you didn’t like it, why didn’t you say something in the moment?” That’s because her nervous system has gone into a freeze response and has to regulate again, even for the part of her brain that helps her understand and make sense of what happened. To come back online and be like, “Wait a second, I didn’t ask for that. That was inappropriate. I didn’t like that.” And because we misunderstand how the nervous system works, we blame victims for not having the appropriate response in the moment that it happened, when they didn’t have a choice.

AA: Hi, everyone. I hope you’re enjoying this fascinating conversation, and I’ll let you get back to it in just a moment. But first I have a question for you. Have you noticed that Breaking Down Patriarchy is totally ad-free? That’s really rare for a podcast, and our team is determined to keep it that way, sharing deep conversations and critical information about patriarchy without charging you a dime or trying to sell you a thing. But we need your help. I know what you’re thinking, and don’t worry, I’m still not going to ask you for money, although we do accept donations if you’d like to support us that way. But no. What I’m here to ask of you is to help us get the word out about this incredible ad-free podcast. If you’ll do just three things really quickly, it would be a huge help. First, like, and follow the show. Second, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. And third, recommend the podcast to a friend. These little things really do make a huge difference and they’re the easiest, most actionable ways that you can support this project. Thank you so much. And now let’s get back to the show.

How would you tell men, and I know there are lots of conversations around consent and making sure that boys and men are now trained. I think it’s partly for that reason too, because I think a lot of boys and men until recently have been quite ignorant of that imbalance of power, at least good boys and men. How do you coach boys and men to be aware of that? That women may have been– not, may have been, they have been. Any girl or woman you know has been trained to please you, whether you know that or not. Do you talk to men about this also?

SF: Yeah. It has been a big conversation, especially between my husband and I, because here’s something that needs to be said. When you stop people pleasing, there will be people who don’t like it. And those might be people who love you because they are used to this old dynamic where you defer or you are silent. And when you begin to stop those behaviors, it’s going to create, like, “Hey, what’s happening here?” And let me use a personal example. I have had a habit for a lot of years where if I have an opinion and my husband has an opinion about something, I defer to him. I have done a lot of deferring, even though in my mind I’m like, “That’s not going to work because of this or this or this.” I’m like, “Fine, we’ll try it your way,” and then I’m resentful later because I was like, “I knew it. I knew that wasn’t going to work.” And he’s like, “Why didn’t you say something?” And in the moment I’m like, “Why didn’t I?” And it’s because of this training. So I have said to him, “Listen. In the moment of decision making, my habit is to defer to you. So if you could ask me directly, ‘What do you think? What is your actual opinion here?’ That would help me feel more comfortable taking the focus off of you and putting the focus on me so that I can even ask myself, ‘What do I think here? What do I think would be best?’ Because I’m so used to the focus being on you. I’m still learning to do that.” We had that discussion a while ago. I’m still working through it. I still find myself feeling resentful because I wanted something and didn’t speak up because I deferred to him. And I think it’s a combination of asking for what you need, like, “I need you to help me slow the conversation down and ask me what I want and give me some time to think about it.” And then the rest of it is me learning what it feels like to connect to myself, to shut out all of the other voices and opinions and really be honest and connected to what I do want, and then to find the words to say it, however uncomfortable that is.

AA: That’s so relatable. That story, Sara, I’ve totally done the same thing in my marriage and have had such similar conversations where my husband is like, “What? Why didn’t you–” He doesn’t want me to just defer, he didn’t know I was doing that. I guess that’s what I was referring to when I said that especially within a very patriarchal context, a heterosexual couple can start a marriage without even realizing that they’re bringing those attitudes and expectations. Another question I have that’s in this vein, and I’d love you to share some more anecdotes too. What’s the difference between true kindness, where you’re like, “I want to do something thoughtful for you,” or “I know that’s important to you and I am going to be nice,” what’s the difference between that in a healthy way and people pleasing? And what you said before was feeling like you have to do what you don’t want to do is a big difference, but can you flesh that out a little bit more?

SF: Absolutely. Again, referencing that definition, it’s all about your internal experience, which is why I say you can’t tell if something is people pleasing on the outside. Because you and I could be in a friendship and I show up to your house with cookies and you have no idea what I’m feeling internally. Maybe I’m worried because you haven’t texted me back, and I’m like, “I have to do something so that Amy thinks I’m valuable, I make really good cookies, I better get over there so that I can see if we’re still friends because I’m anxious and worried all the time about losing her friendship.” Or I could be like, “Hey, I made these cookies, I know you like them, and I just wanted to share.” There is such an internal beauty to our emotional landscape and experience that so many women are not familiar with because we are rewarded for having our attention out all the time, these tentacles that are attached to everybody else, “What does he want? What does she need? What can I do for you?” So, taking some of that attention and turning it back in, you will know, with practice and attention to yourself, “Why am I doing this?” And I’m not even going to say that acting out of duty or obligation is wrong. Because number one, “What am I feeling?” The second part of that is, “Why am I doing this? What are my reasons?” And if I like my reasons for showing up, okay, here’s a great example. My parents, about every other week, something goes wrong on their computer. And they call and they’re like, “This thing used to work, it doesn’t work anymore.” Do I want to go over to my parents’ house and show them how to reset their password? No, but I like my reason for doing it. It’s a little obligation, maybe duty fueled, but I want to show up for them, I want them to have access to the information on their computer, and so I’m going to go do it. Do I love it? No, but I don’t have to love it as long as I know my reasons and I like them. And that’s the part of our internal experience that we often don’t have a lot of connection to when we are just stuck in people pleasing, because it’s about everybody else’s experience, everybody else’s emotions. So the difference is “what am I feeling when I do this and what are my reasons?”

what am I feeling when I do this and what are my reasons?

AA: Yeah. And I love how you said you can’t tell from the outside what a person’s reasons are and why they’re choosing them. So, correct me if I’m wrong, we’re just going to do this little exercise. If you have those reasons and you feel good about it and you’re like, “This is something I want to do for my parents as a daughter, even though it’s not fun, I still choose to.” The unhealthy people pleasing way or motivation might be “They won’t love me anymore if I don’t,” or “They will think I am selfish or they’ll think I’m ungrateful.” Because what you’re saying is that you’re then being motivated by what they will think and I have to do these actions in order for them to have these thoughts about me and for them to like me. Is that right?

SF: That’s exactly right. And because this programming is so deep, the last thing I would say is to just notice if you’re always choosing to go do things for other people. Because I think we can also subtly hide from ourselves like, “No, no, I just really like to do this. I just really want to.” Because most women, when I talk about like, “What would your life be like without people pleasing?” they think they’re going to be selfish and self-centered and mean, and that their needs and their wants are going to be the only ones that matter. And they’re so used to living in the reverse, that everybody else’s needs matter and they’re below everyone else. They think that the opposite is true when they don’t people please, that their needs are the only ones that matter. And what I really am after for every woman is just equal. Sometimes my needs matter, and sometimes yours do. Sometimes I pick me, sometimes I pick you. And if you’re always picking the other person and still doing things for them, I think that would just be something to take a look at. Because equity in relationships means that you matter too. You are deserving of your own time, energy, effort, exploration in creating the life that has you a part of it as well.

AA: This is so helpful and so relevant. Let’s say now that I just realized I’m a chronic people pleaser, let’s just use this as an example, I’ll be a proxy for anybody listening who’s relating to this. I’ve just realized, “Oh wow. I’ve been a chronic people pleaser my whole entire life. For decades. It’s been affecting my life negatively. But the habit is so entrenched, I don’t know how to stop.” And let’s say I tried out this thing, and you’ve already said that when you change the dynamic, it’s likely that the other person isn’t going to like it because neither person is used to it. So how do you coach people through that process and develop the distress tolerance that will inevitably come when I disappoint somebody? And let’s say it is somebody who’s really, really important to me, like my dad or my husband, a family member, a really close friend who is used to me deferring, soothing, doing all the work in the relationship, and I decide to rock the boat and I’m flooded with cortisol and all the chemicals that make us feel like we’re going to die. How do you coach people through that process, specifically so that they can stick it out and start forming new habits?

SF: Great question, and I want to go back to what you said. This is about distress tolerance. Here’s how I like to say it. When you are stuck in people pleasing, it is distressing. You’re saying yes to things you don’t want to say yes to, you’re overwhelmed, you’re overthinking, you’re beating yourself up, you’re worried about what other people are thinking of you, you’re overgiving. That is distress. But it is the distress that’s the wallpaper that we’re so used to. So the first thing I have women do is assess how much time, energy, effort, brain space, and resources are you spending people pleasing? And for most women it is three to five hours a day. And here’s what I mean by that. Their brain is replaying all of the instances where they didn’t say what they wanted to and now they’re worried about what somebody thinks of them. They’re rethinking and doubting themselves and criticizing and judging, or they’re overthinking decisions, not believing that they know how to make good decisions. There is a lot of time and energy and effort that is just leaking out all the time, and that amounts to thousands of hours of non-renewable resources: time, energy, and brain space. I mean, no wonder we’re so tired, right? Our brains are constantly going. That’s the distress of people pleasing.

And once we really understand that that is my actual life, that’s my time, those are the ingredients with which I create my life that is just being flushed down the toilet because I don’t get a return on that, because all that does is reinforce that I’m going to be the people pleaser, I’m going to defer, I’m going to soothe, I’m going to pretend or perform. And so really seeing that that is the state of this distress sometimes makes the distress of not people pleasing look a lot better, a lot more attractive. Because now what I have to do is I’m already distressed, I just have to learn how to tolerate a different kind of distress. I have to learn to tolerate the panic of saying no, or the discomfort of saying, “I don’t want to do that and I don’t have time for that.” Or the worry of expressing my true opinion and knowing that other people might think differently about me. I always suggest that you start with lower risk situations first. So maybe you’re not going to tell your dad. In my case, the conversation that took all of my skills was when I told my parents that if they continued to try and talk to my daughter about being gay in a way that signaled that they did not approve, that they were unhappy with her choices, that they would not be welcome in my home anymore. I would have never imagined being able to have that conversation in a very civil, what I thought was respectful way, had I not practiced on a hundred other lower risk conversations before. And lower risk is dependent on each person. I have worked with a client who went to the same Starbucks on her way to work every single day. Four out of five times, she got the wrong drink, and she’s like, “Well, I guess I’ll just take it.”

AA: Oh, no!

SF: And for her to push the drink back across the counter and say, “This isn’t what I ordered. Can we try that again?” It almost sent her into a panic. But that was a lower risk situation that she could take on first before talking to her dad. So, start with lower risk situations first, and I can go into that a little bit more if you’d like.

AA: I would, actually, keep going. This is so, so helpful.

SF: Okay. So the first thing that you have to do, there has to be a pause in the habituated behavior. For example, I go into Starbucks, I get the wrong drink, my habit is “Okay fine, I guess this is just what I’m getting today.” I take it and I leave, and then I feel bad. I feel resentful. I feel like I don’t matter. I feel like nobody sees me. That carried on into the day with her. I have to pause for a second and remember, “Okay, I’m trying a new skill.” What we worked on was that she would see the drink coming toward her, she would see that it was the wrong one, and she would go to the bathroom. She wouldn’t pick it up immediately. And she would take a little pause, go into the bathroom, connect with her body, physically put her hands on her body and say, “You are safe. It is safe to do this. I’m right here with you. We’re going to do this together.” Because inside each of us is that scared little person, that little girl or, you know, socialized as a girl, who’s like, “I am terrified about what is going to happen if I say no.” So she calms that part, she goes back out, and now she has interrupted the habit and she can make a different choice.

The other thing that is really helpful, and in that situation we were able to turn that around pretty quickly. But if after you pause and after you connect with yourself, you have to really be honest about what is going to happen. “If I take the drink, I’m going to feel terrible for the rest of the day and I’m going to reinforce this behavior. If I don’t take the drink, I’m going to feel panicked for a minute, but I choose to feel panicked on purpose because that’s the direction that I want to go in.” So you have to choose, after you do some predicting about “I could people please here, or I could not. What moves me in the direction that I want to be going”?” and then you choose on purpose because you like your reasons. And then it’s a matter of just practicing. Practicing, practicing, practicing. So, pausing, connecting with your body and helping yourself to feel safe, looking at your different options and predicting, that’s something that we never do, which is why so many of us people pleasers we’re volunteering to run the school carnival and we’re thinking, “How did this happen to me? How did I get here?” It’s because we didn’t pause and predict, “If I run the school carnival this year, it’s going to take five hours of my time, I’m going to… blah, blah, blah.” Once we really know the cost, that gives us a lot more reasons to say, “You know what? It’s not the year for me to do that. Thanks for thinking of me.” And then once we get into a habit of pausing, connecting, and predicting, knowing our reasons, then we just have to practice.

AA: Let’s use that example of the school carnival. Let’s say this person has planned the school carnival for years, or they’ve done other things at the school and they’re like, “We can count on her.” And that’s part of a pride of like, “I’m a person who contributes to my school and my community, and everybody really likes that about me, and I like it about myself. However, for reasons A, B, and C, this is going to have a huge cost for me this year.” Let’s say I try saying no and I get pushback, and so you prepare for it. “Okay, I’m going to panic when I say no.” And then let’s say the worst case scenario does happen and everybody is like, “Oh my gosh, that’s so selfish. You actually totally do have time. We all work full time and you don’t,” or whatever the reasons are. How do you, I mean, I guess these are just the tools of distress tolerance and self-soothing. Because you might lose relationships over it, it’s so hard!

SF: Right, right. Yeah, I totally understand. I feel that. Here’s what matters. Number one, I think it’s helpful to have at least some acceptance, possibly even compassion, when other people are upset. For example, if I have always been the one to do the carnival, it makes a lot of sense to me that people are going to be upset when I don’t. And when I am alone I can do some things with myself to be like, “You know what, it makes sense. I always do it, I’m pretty fabulous at this, I understand that not doing it is going to mean that somebody else has to. It makes sense.” So that I go into the conversation being able to have some capacity to understand, like, “I get why this is upsetting to you. I understand that.” And I have found that when I do that beforehand, I can say to whoever I’m disappointing, “I get it. I know being disappointed sucks. I appreciate you being willing to hear me out on this, but it’s not something I’m going to do.” I can actually have both things at the same time. Compassion for them, “I understand why this is disappointing and upsetting to you,” and I can still hold my ground. That was exactly the dynamic that I had with my parents in that conversation. I could say to them, “I understand why this is distressing to you, that you have a grandchild who is gay. I get that, and I will not be changing my mind about this.” That’s the first thing that I would say, is just to spend some time in a compassionate stance. Because compassion doesn’t mean you’re going to change your mind. Too often we conflate the two. “If I understand you, it means I have to give in to you.” Those are not the same.

And then number two, you might need to pause again, right? If it gets really heated, you might need to say, “This is getting really heated. I want to take some time and think about this. Why don’t we revisit this next Thursday?” Not because you’re going to change your mind, but because you’re going to spend some time strengthening and connecting. One of the most valuable tools that I teach in my work with clients is that I have a specific process for finding the exact words that you want to say and practicing them using mental rehearsal so that your body can feel the distress beforehand and practice it. So that’s what I would do, is practice the words you want to say, get really clear on them, memorize it like a little script, and then play the movie of you going back to the meeting on Thursday. You see yourself standing up. I value being kind, so I would probably say something like, “That you are all fans of how I run the carnival means a lot to me. And it’s not something I have time for.” And then watch yourself mentally doing that over and over and over again. That anxiety’s going to come into your body, that fear, and you’re going to watch yourself take good care of yourself, and then that prepares you to go back again for round two, if that’s what it takes.

AA: I love it, Sara. That’s so great. I’m just thinking, yes, kindness is so important to me too, and I think it should be. I think it should factor in.

SF: Me too.

AA: Something that is tricky and that I’m just learning now at this age is that, through experience, when I look at the relationships in which I have been a complete people pleaser, I feel like I’m being kind in the moment, but over time it has damaged the relationship to the point that I can start losing my compassion for the person. So in the long run, it’s actually not the kind thing to do because it can kill love. And you talked about resentment before, that you can build up so much resentment that it can, I mean, this is what can result in divorce or estrangement in families, from people cutting and just being like, “I can’t do it anymore. I cut you off.” It would’ve been much kinder to, with a nice and respectful and loving tone, set a boundary way, way earlier. Am I right about that? I’m seeing it play out in my own life. I’m like, okay, this is not the kind thing to do after all, actually, even though they’re not going to like it. They might think I’m mean in the moment, but I have to just be like, “Just trust me, this is the better option.” Right?

SF: Yeah. There is a quote that I heard a while ago by Friedrich Nietzsche, and I know he’s problematic and I’m certainly not endorsing everything he said, but this thing he said really felt like a bullseye for me. He said that most people prefer dishonest peace over honest conflict.

AA: Yes, true.

compassion doesn’t mean you’re going to change your mind

SF: I want to change that a little bit. I want to say we only know, or we are taught dishonest peace and we are not taught honest conflict. It’s this recipe for disaster, because I’m having to kiss the creepy uncle, I’m having to finish my food, and I’m totally disconnected from the sensations in my body, and I’m used to shoving all those down. And then I see the people around me who just want me to be nice and kind. Of course, I don’t know how to say, “Hey, I don’t like this. This doesn’t feel good. I don’t think I want to keep doing this.” And when all of that erupts because of resentment and anger, now I am the bitchy woman who is angry all the time. So we don’t get any teaching in how to be honest about what our internal experience is like. And I think one of the most interesting dichotomies about this is that if you ask people who are in relationships with people pleasers, they say things like, “It’s really hard to talk to Sara because she never wants to choose the restaurant we go to. She always defers to me. She always says, ‘I don’t care what we do,’ so I feel like I have to make all the decisions. I chose for us to go to see this movie, and then Sara later seemed irritated about it, and I was like, ‘but what happened?’”

So if you are not the people pleaser, you can’t trust that the person is showing up and being honest about their feelings because we don’t know how to, and we think we’ll be punished for having strong opinions or making everybody go to the restaurant we want to go to. We have all these really not helpful ways of thinking about taking up space and having an opinion, but there isn’t any training on how to be honest. And I will tell you that the friendships I have, the relationship that I now have with my husband where we can be very honest with each other, is the most safe and secure feeling in the world. Because I know that if I call my friend and I say, “Hey, do you want to go to this movie?” And she’s like, “You know what? I’m not really interested in it,” that is the honest truth and I don’t have to worry about it or think about it. Or if we go, I know that she really wants to be there. And it’s such a different way of thinking about it. But being able to be honest, and I will say this, I think one of the most unfair characterizations of people pleasers that I hear a lot is that we are liars and that it’s lying to be manipulative or controlling. It’s not. It’s lying because the truth is not yet safe to say. We’re not safe with ourselves to say it, we beat ourselves up, we criticize, we judge ourselves relentlessly, and we create that lack of safety within ourselves and in a lot of our relationships. People don’t like it when we don’t people please, and so we stay in those habits to keep the relationship.

AA: For sure. Especially if that was really strong in our families of origin and in our cultures of origin.

SF: Absolutely.

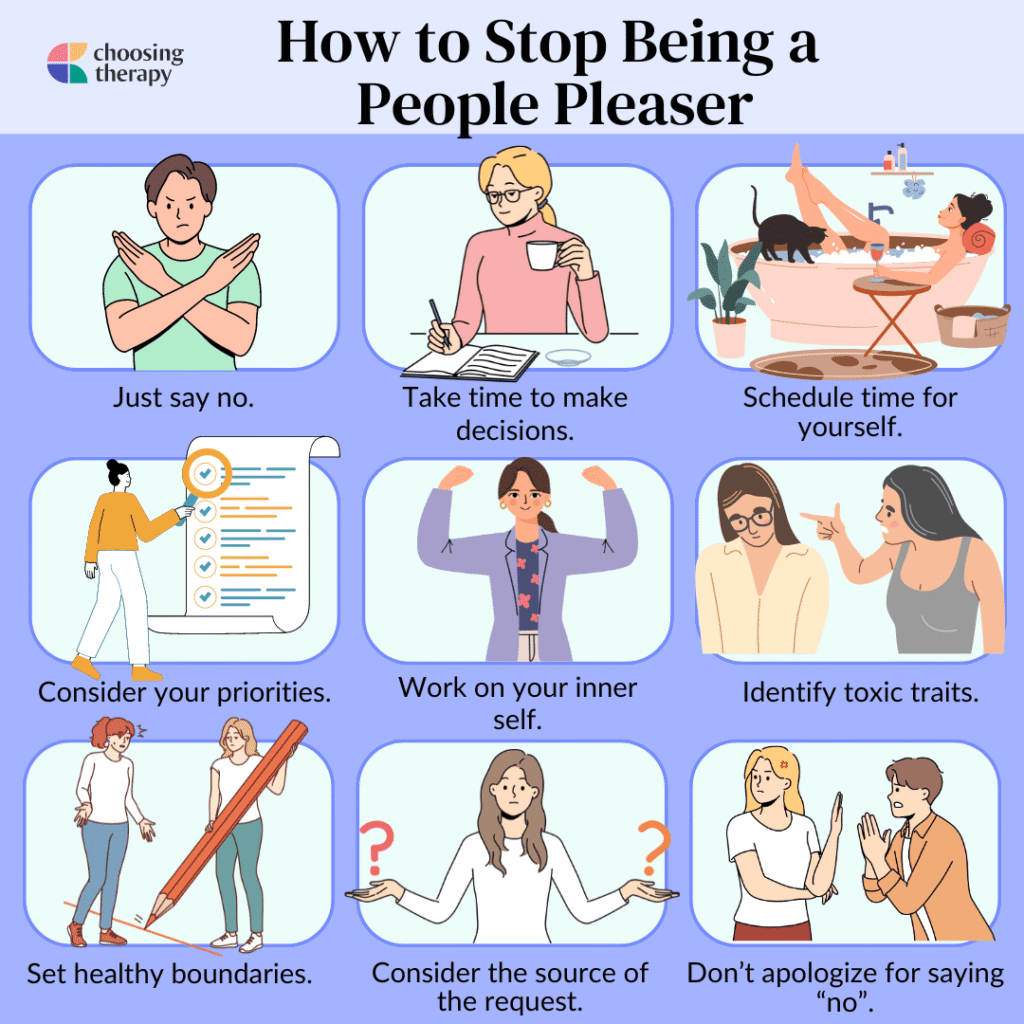

AA: And we don’t know that about the people that we’re in relationship with, sometimes we don’t know how their parents handled it. Well, Sara, this has been so, so helpful. I’m wondering if there are any action items or specific takeaways, even if it’s a summary of something that you’ve already said earlier. If you could leave listeners with just one or two things that would be good starting points, what would they be?

SF: My very favorite is to just take your hands, put them somewhere on your body that feels like loving, connected presence, and just say, “I’m here, I’m listening.” Whenever I say that, I feel this really beautiful, melting connection, and I do that multiple times a day. I didn’t use to have the practice of it at all. I was the master at ignoring my anxiety, ignoring my sadness. And the way that we begin to build that relationship of trust with our own bodies and our own souls is just by listening. So even if you can just do it here and there for a little minute, like, “I’m here. I’m right here with you. I’m listening. I’m interested in you. I want to hear what you have to say.” And I realize that sounds a little like there’s a “We” here, and I think there is.

AA: There is for me.

SF: There’s me of today, and then there’s all the little girls that I’ve been in the past who were really scared about what it would mean to make other people mad. And then the second thing is to notice how people pleasing shows up for you, without judgment. Because one of the saddest things, I get a lot of women in their late thirties, forties, even fifties and sixties, and they’re like, “What is wrong with me? Why can’t I stop this? I know I don’t want to do it. My brain says, ‘No,’ my mouth says ‘Yes.’ What is wrong with me?” And that is the number one thing that women do to undermine their own safety, is we are our own bullies. What that means is that we’re living with that bully 24/7, and if you’re not safe with you, you’re not safe anywhere. So, just notice, when people pleasing comes up, how do I talk to myself? And can I have some compassion for the programming that I’m acting out? And the fact that I’m not a bad person, I am a good person who has been programmed to please. You cannot beat yourself into not people pleasing, because that just piles discomfort on top of discomfort. The only way is to be compassionate and to be open-hearted and present with you as a good person who’s just living out some programming that doesn’t work for you anymore.

AA: Oh, that’s wonderful. Such great advice. I love that that’s actionable and I think so, so useful and relevant for people. Thank you so much for being here, and as we wrap up, can you tell listeners where they can find your work?

SF: Absolutely. My Instagram is @sarafiskcoach. I have a podcast myself, it’s called the Ex Good Girl Podcast.

AA: Love it.

SF: And it’s where I do a lot of sharing ideas. So those two places, I also have a free Facebook group for women to join if they just want some help along the way. So those are three good places.

AA: Wonderful. Well, again, thank you so much for being here today and helping us learn to stop people pleasing. Sara Fisk, thanks.

SF: Absolutely. It was such a pleasure.

we are taught dishonest peace

and we are not taught honest conflict

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!