“As far as making people uncomfortable

…Sorry, I feel uncomfortable all day.”

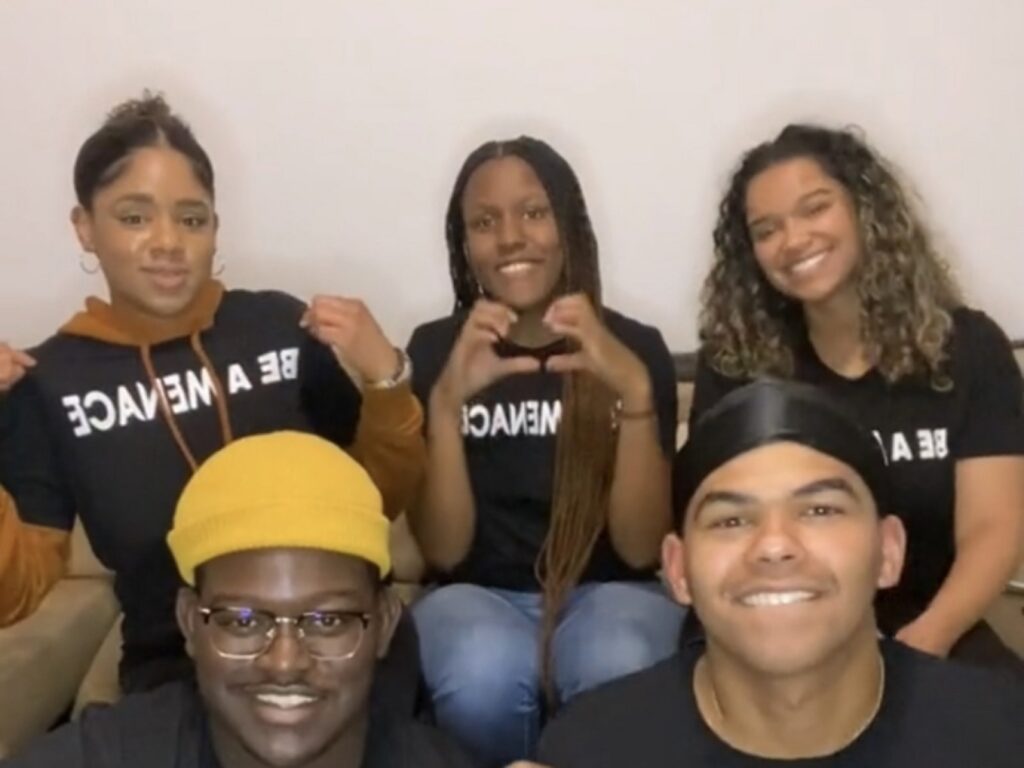

Today I’m thrilled to be joined by Sebastian Stuart-Johnson and Kylee Shepherd, two members of The Black Menaces.

The Black Menaces formed a couple of months ago when members of the Black Student Union at BYU started taking a microphone around the campus of Brigham Young University to ask questions to students and faculty. They ask a simple question each time and let the person answer honestly, without arguing or making much comment at all. They later posted these videos on TikToK and they almost instantly went viral with many videos, getting millions and millions of views since.

Our Guests

The Black Menaces

The Black Menaces started in February, 2022. The group made a reaction video to a BYU professor’s insensitive comments about black people in the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, and the video instantly went viral on TikTok. The Black Menaces are a group of five friends; Sebastian, Kylee, Rachel, Nate, and Kennethia. Rachel and Nate are recent BYU alumni, Kylee and Kennethia are entering their senior years, and Sebastian is finishing his junior year. The goal of the Black Menaces is to shine light on the problems and issues that happen at predominantly white institutions and enact change. They hope for a better future for any and all minorities that are mistreated and underrepresented.

The Interview

Amy Allebest: I’m going to start out with a question that you sometimes ask on your videos, which is if you can think of a favorite thing about BYU? It doesn’t have to be your definitive favorite, but something that you do like about BYU, and then something that’s been challenging at BYU.

Kylee Shepherd: I think my favorite thing, honestly — especially with being a psychology major… I know a lot of people struggle with having a faith in God and psychology because there’s ‘nature versus nurture’ and ‘do we really have a choice in things?’ I think I kind of like the connection that BYU gives us a church school, but in my psychology classes we never really talk about the church. It’s a really weird balance of things, but I think having the option to like relate it back to God and kind of making those connections makes it easier for me to have faith and learn about psychology.

I think a hard thing…obviously just being a black woman, trying to navigate who I am on campus and kind of coming into my Black identity continuously, it’s almost like an everyday thing for me

Sebastian Stuart-Johnson: Yeah. I would say my favorite thing at BYU or my friends, the people that do Black Menaces with us, and then also the primarily there are actually the Black students at BYU that I’m really close to. It’s a good handful or a few handfuls I’m super, super close to. They make it worthwhile for me. They help me continue on every day.

One of the things that is harder for me, I would say, is having the ideologies that I do like (and that can be in regard to like political things or societal issue) and then being at BYU where I know most of my peers do not agree with me. Especially since I’m a political science major, we talk about it very often. So hearing things that in my opinion can contradict the human rights of a person or whether that…that can spend so many issues. But that’s difficult because I can go with issues regarding the Black community or with women or the queer community and a lot of things I’m very passionate about.

AA: Thanks so much. Okay, really quick, tell us how Black Menaces started?

SS: Yeah. So I had got the idea originally… it was really just to showcase what we live through at BYU. Most people don’t know. And we constantly have been telling the administration for years our story, hopefully, and they would ask like ‘oh, we want to hear you.’ but they wouldn’t make any changes in regards to what we tell them about the racism and the sexism or whatever it is.

It was really a combination of all those feelings and we came up with it and I said, we should make a TikTok to highlight what we go through, but kind of in a satirical way. But then it formed into something much greater than we ever thought it could be, something that we can really highlight on a mass scale and you can laugh with it, but also, you know these are pressing issues. So it really was like the culmination of all their pains and feelings in a way that we wanted to highlight and how the whole world somehow has seen it.

AA: Another question kind of about the formation: who’s your intended audience? And were you really clear about that when you started it?

KS: I don’t think so. I think it was more (I still even think it is this) it’s more just anyone who’s willing to listen. And I think we all have something to learn, even if you are Black or even if you are part of a minority, there is something you can learn. So I would say that’s our target audience.

…we constantly have been telling the administration for years our story, hopefully, and they would ask ‘Oh, we want to hear you.’ But they wouldn’t make any changes in regards to what we tell them about the racism and the sexism…

SS: Yeah. I think like she said, echoing what she said, everybody we’ll listen. And then specifically, now we’re focusing a lot on like predominantly white institutions and universities are majority white, so most of them.

And so we’re focusing on those to make those spaces more equitable and equal and inclusive, much more than they are right now because there’s millions of marginalized students at and included in a lack equity, etc… And so that is kind of what we want to change. Our target audience is if you’re going to listen, please listen and get ready to push a little bit harder so we can make some real change.

AA: Awesome. Two questions: The first is how has this project impacted you personally? And then what impact do you think it has had on BYU maybe as an institution, or you could think of like personally on students at BYU? You can answer that however you want, but first you personally, and then BYU.

KS: I think for me, it’s kind of showed me that I can speak out more. I’m not a very frontline protestor, I guess. I don’t like confrontation if I can avoid it and I’d rather just roll my eyes and walk away, which isn’t the best at times. So I think it’s kind of showed me that it’s okay to be who I am and then be confident about it and then talk about the issues that I face on campus.

Or even just outside of campus in Utah, even I think for the students, I think it’s kind of started a conversation. Even if they don’t like us, at least they’re talking about us. I think it makes people realize some of the biases or….I don’t know how else to phrase it, biases that they may have or questions that they don’t think about.

I mean, they always are like ‘Hmm I’ve never thought about that.’ Like, yeah, that’s called privilege and that’s great that you’ve never had to think about it, but it’s okay for you to start thinking about it now and accept that you don’t have to think about that because of the color of your skin or because of your sexual orientation. Like the little things like that.

SS: Yeah. I super agree with what she said. I love it, but something that I felt a lot these last few months is gratitude. I felt a lot of gratitude for the way that we’ve been able to vocalize ourselves and show people, for the people at BYU who have spoken up in support of us. And then also the ability that we have to show the experience of so many students across the nation. It’s crazy how many students that go to different PWI’s (predominantly white institutions) across the nation who said ‘Wow, like this exactly what I feel’. And I think that’s very beautiful and I’m very grateful to be able to highlight that for them.

AA: So we talked a little bit about how it impacted you. How has it impacted BYU? Have you heard anything from the administration at all?

SS: We haven’t heard anything directly from the administration as of yet. We’ve heard like little things from through the grapevine, more rumors than like solid truth, but we haven’t heard anything directly.

We’re hoping to start meeting with them, like as The Black Menaces to hope, to work, to make some change on campus: systemic change, real change, and use the platform that we have in the ability to use the awareness that we’ve highlighted to push that change a little bit further, but we haven’t heard anything from them.

AA: What has been the reaction of the broader public? What are some positive things you’ve heard? Maybe if you can think of some specific examples, one or two, and then if you’ve had any negative reception, what does that look like specifically?

KS: Let’s start with the negative, cause we can end on a positive. Somebody just made a video of us recently comparing us to ‘the adversary’, which is basically Satan, the bad things in your life. And that kind of hurt my feelings, but we have a lot of people who, I mean…we don’t even ever say our opinion, which is my favorite part. And people assume they know exactly what we think or if we, or they just assume that we didn’t have to think about the questions we were asking.

Like a lot of the questions we ask, we might not all agree, or we might have to take a step back and think about it and really reflect on why we think the way we do or what our answer is and all of those things. But we definitely have our fair share of haters who love to post about us on Instagram and Twitter. And they just say…I think I just saw a comment recently that we asked racist questions and I thought that was hilarious because it’s a simple question. The questions we ask are racist. It’s the responses. But then you have these…usually it’s white men. not to throw down white men, but usually it’s white men…who are like ‘these are racist questions.’ And it’s like, ‘if you think that’s a racist question, then you’re agreeing that the response that was given is racist’. So they just kind of flip it and they’re like almost there, but they’re not. And I think it’s kind of funny.

SS: Yeah, honestly, I think all the hate is funny almost. And I posted about it actually, because I’m like, ‘okay, you want to, you want to talk? I can talk’. You know what I mean? Like I do read some of them. It depends on what mental strength for the day, but I don’t argue back to them cause I, most of the time I don’t really have the energy.

I’m going to go to the positive (you can read our comments if you want to see the negative). On some positive, one time this girl came up to me and another Black Menace and started crying basically because she was so grateful for what we were doing on campus and how we were able to like push her story and things like that. So there’s a lot of beautiful moments with people when they come up to us, because people are bold when they come to us, it’s hard to come up to random people that you don’t know that you are TikTok famous. And they come up to us very openly and talk about what they think and feel and their gratitude and that’s something that I am forever grateful for. So that’s awesome.

KS: I think I positive for me is kind of within my own personal life. So I’m biracial — my mom is white and like my grandparents and everything — and I think like I have been talking about my experiences at BYU since I’ve gotten to BYU. So like a freshmen and, obviously because they’re white, they just have a different life experience than me. And so it was kind of hard for them to understand exactly what I was trying to describe to them. They were just kind of confused because like, I’m going to a church school, like it’s supposed to be great…which is understandable. I mean, if I didn’t go here, I probably would think the same thing too. But with kind of this movement that we have started and the things we’ve talked about and all the interviews we’ve gotten, I think it kind of finally clicked. And like my mom posted just like of how proud of me, how proud of me she was. And it just really, it made me feel warm inside, I guess. She has always raised me to be strong and independent and that’s exactly what she said, ‘keep doing it Kylee, raise your voice’. And it just made me feel like, ‘oh, like I am doing something. I finally have gotten through’, I guess, is the way to put it to my family. And like, my grandma reached out to me too and these are like two important women in my life. So hearing that they were proud of me kind of just made me like giggle inside.

AA: I love your emphasis on the positive and I honor that and I think it’s so beautiful. So Kylee, you and I were able to have a conversation yesterday about some of these responses. And you mentioned that there was a YouTube video where the person compared you with the biblical figure of Cain. Would you mind talking about that a little bit? I don’t know if all listeners know, but in broader Christian theology, but very much accepted and adopted and promoted by Mormon theology, was this idea that people of African descent descended from the biblical figure of Cain and that when God cursed Cain, it was a curse of dark skin. And that’s where, you know, that the dark skin comes from. So the church has recently made attempt to disavow that doctrine. So when I heard you say that that was still being thrown and thrown at you, I was really shocked. And maybe that just demonstrates, again, my own privilege of still learning how bad it is, because I did not know that…I just was surprised to hear that that can still be happening. Do you have a comment on that?

KS: Yeah, I think, and from listening to like the man’s video, I think it was more of like ‘Cain betrayed his brother’ and all of that context where it was more just like, oh, we’re evil and we betray everybody. I think that’s kind of more what he was saying. That’s kind of what I’m going to go with because I think it’s a little bit better, but I think it still kind of stems from the idea that Black people…it’s a curse to have dark skin or brown skin.

And I mean, that’s where it comes from. And so it did kind of hurt and which is, that’s why I said earlier that those comments hurt our feelings because our purpose isn’t to make people look bad or to turn people against the Church. Like not at all. Like that is not our goal. Our goal is to just raise awareness of the things that we face every single day. And that’s why I want to be vulnerable and say that it does hurt my feelings. And I can’t speak for the other Black Menaces, but we are human. And this is every single day for us. And if I could have people know anything it’s that it does hurt. And for people to say that like my skin is a curse or even have ideologies that stem from that idea is so hateful.

I mean, you wouldn’t look at a little child or at least I hope, and say like, ‘Hey, sorry, that’s a curse that you’re brown’. And I am a child, my inner child. And so for that man to even just to allude to that idea is awful. And we just hope, and that’s the awareness that we’re raising. That’s what we hope to change. So even we’ll give him the benefit of the doubt and let him make that one mistake. But moving forward that you can’t say stuff like that to us, because I am a human and I mean something and you don’t necessarily have to know that, but I know it. And so I’m going to speak out about it.

…there’s a lot of beautiful moments with people when they come up to us, because people are bold when they come to us…and they come up to us very openly and talk about what they think and feel and their gratitude and that’s something that I am forever grateful for.

SS: Can I add something to that too? I was just thinking with the real experiences that she’s mentioning, like there is something that has happened within every year for the last three years. Something at BYU has happened that has perpetuated racism in doctrine or racism at BYU or in the church. Like this year, that was Brad Wilcox. Last year, there was a panel of Black women and a ton of like the questions that were submitted to them anonymously that were racist and race baiting and all of these different things. And then year before that, in the Come Follow Me handbook it’s specifically mentioned in the book of Mormon section that the curse was dark skin and it was like the stem of Cane and it was written out in the Come Follow Me book. And so I think if we think that it no longer exists within us, then we should look a little deeper. Because we face it a lot. And it’s crazy to see those ideas that were pushed and created in the early 1900, late 1800s, to justify the priesthood and temple ban still exists today on a wide scale.

KS: And what we actually talked about this yesterday, Amy, like you said, ‘if you breathe in racism, it’s you’re bound to have racist ideas’ and that’s fine, but you have to change those ideas because you can only control your environment so much. I mean, I have my own biases of things that I probably shouldn’t that I’m working on. And I think that’s the part that’s important: that we have to notice those things. And if we don’t notice them right away, if someone points it out, be willing to take in that constructive criticism and change. And like, that’s the whole purpose. We’re supposed to make mistakes, but we have to learn from them. And it’s almost like we can’t learn from slavery and the civil rights movement and lynchings and all of these like horrible things. It’s like, ‘oh, it’s in the past’. And it’s yeah, it was in the past ut sometimes it’s okay to look back so things don’t continue to happen.

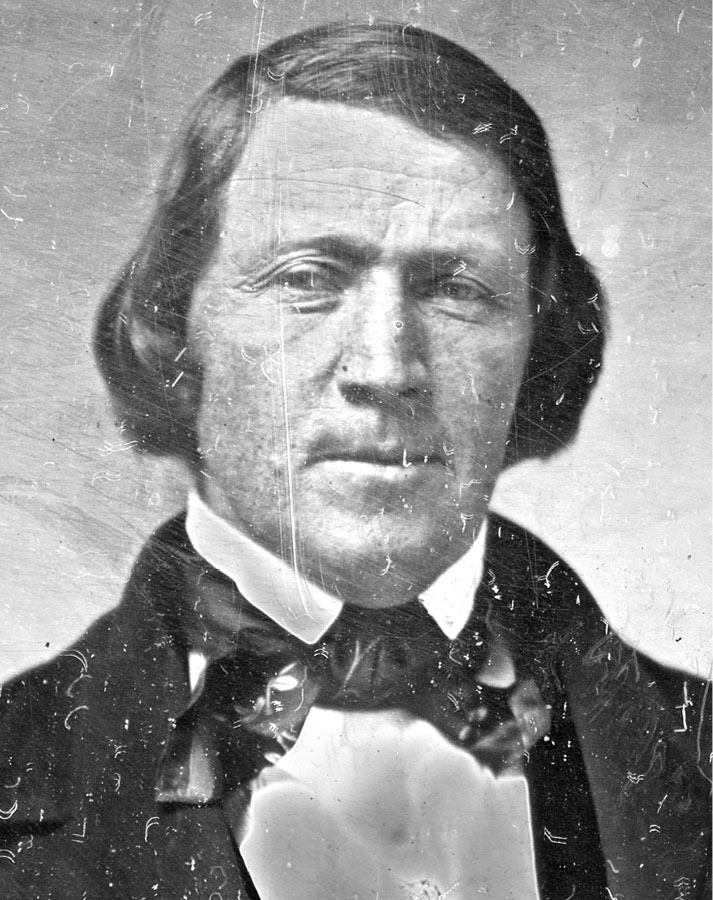

AA: Continuing along this line of thinking, the Church published online on its website, an essay several years ago, about the ban on anyone of African descent. Any man could not hold the priesthood, and no one of African descent could enter the LDS temple. And for listeners who don’t really know the context of that, it’s different from a priesthood ban, like in the Catholic Church where there’s a tiny little percentage of men who would even want to be priests. And so it’s still an unjust practice, but it only affects a few people in the LDS church. Every man is expected to hold the priesthood and that impacts everything in that man’s family, right? Like blessing a baby, performing a baptism, lots and lots of daily things that were denied to Black men. And the temple is the place where in LDS theology where you go to receive saving ordinances so you can live in heaven with your family, and Black women and men, all Black people were denied those saving ordinances until 1978, which is in my lifetime. So listeners just need to understand what that really meant… But the church did publish an essay talking about the ban and I felt like some people really celebrated it because it acknowledged that it came from racist ideas. For example, the quote that we started with Brigham Young, he believed in slavery, he said horrible things, which I will not subject you to, but you can look it up. But anyway, the essay said basically those early church leaders had racist ideas, like everybody at the time. And so a lot of people felt like, ‘yay, all better’. Do you think it’s sufficient? Do you feel like they’ve done sufficient apologizing in order to be able to heal?

KS: No, I don’t think they have. I think the essay is like the bare minimum of a start. Like it does put out the idea and it’s like, ‘Hey, this is what happened’. But I think the problem is we expect the bare minimum from church leaders and they think like, ‘okay, here’s this essay that if you happen to read it’, like then, you know, but if you don’t like… I’m only 21, so I was really young. I wasn’t old enough to process really what was being read.

Yes. I think an apology needs to happen and I think they need to come out and just flat out say. Like we do not support racism. And I think if that was said, yeah, I would have said a lot of people, you know, certain types of people, but that’s fine because Black people and most minorities have been upset for years. So like we please the white man and we need to move away from that idea that in order to have peace, that the white man needs to be made to feel good about themselves because that’s what we’ve done for years. And we need to move past that. I think if the church came out and apologized, I think it would make a lot of people happy and I think we could move forward.

And I think a lot of, a lot of Black people would probably join the church. I mean, I know like my dad, isn’t a member and I know part of his reasons are that, I can’t ask a strong Black man who is very confident in his identity to join a church that didn’t like him within his lifetime. Like, just like you said, Amy, like, why would I do that? It doesn’t even make sense because he’s like, ‘why can’t I have all the power or the priesthood power?’ Like how can we say I wouldn’t have been able to have that. So if the church apologized, I think it would ease a lot of hearts and it would just show a vulnerable vulnerability that it’s okay to make mistakes. And yes, it was part of the time, we can’t change that, but we can fix it.

SS: Yeah, for sure agreed. And I don’t think the church has done nearly enough at all. I think there’s so many things. We’ve met people, I’ve met so many people that still believe that the priesthood and temple band was of God. And that says a lot, like, you can have a letter online, but if a ton of members still believe that it was of God, then obviously we haven’t done nearly enough. Right. Like we need to disavow…they had a lot of racism inside of it. We need to be disavowing that the priest did the temple band was not of God. We also need to be speaking against factions in our church, like DezNat within the LDS Church.

AA: Can you explain what that is for listeners who don’t know?

SS: DezNat is Deseret Nation. They’re an alt-right group inside of the LDS Church. And in my opinion, they’re despicable because they’re very like…imagine if like you were stuck in like 1935, that’s kind of how they are. They have all of the beliefs, like racism and a ton of sexism in a ton of homophobia. And so there’s so many things that Kylee was saying, like, we leave the people who perpetuate so much violence, you know, both mental, emotional, sometimes physical, to be comfortable and happy, but strengthen those that have never been comfortable. And so I think so much has to be done and I’m not, you know, an apostle, but I can tell you, I don’t think that was…my God didn’t do that. So I don’t know who’s did.

AA: Thanks Sebastian. Thanks Kylee. Another question that I wanted to ask is I had a conversation with somebody just a couple of days ago about The Black Menaces — this is a white man, my age, really progressive thinker, really good guy. And he said, ‘yeah, I really like the work they’re doing. I really value it. But. I feel like it is pretty aggressive. It feels aggressive to me because they’re cornering people and asking them these questions. And then they’re just catching these poor young, 19-year-olds off guard.’

And when the conversation turned into him having a lot of opinions about how you should conduct your work. So aside from whether we think any of his points have merit or not, one of my feelings as he was talking was just the tone policing that he was doing. I don’t know if you’ve encountered this before, like ‘I want to hear what you have to say… Oh, but not like that. Oh, you’re getting kind of angry. Oh, tsk tsk now you’re sounding kind of shrill…’ and this is something women get of all races get also too, like when, even as a white woman who has a lot of privilege in some arenas and others, like don’t raise your voice, don’t get angry. And one thing that came to my mind is that a lot of Americans are so proud of our white ancestors who started a revolution against England and literally picked up guns to kill people because of the stamp act. Right? Like they, they killed people over England infringing on their rights. In the meantime, they were in slaving people in chains, forced labor, raping women, treating human beings like cattle, like animals. And so now as, as their descendants for us to be like, we’re so proud of our ancestors that started a revolt over something relatively so small that we would have the nerve to say like, ‘oh no, no, no. You’re getting a little angry. Watch your tone now.’

Anyway. Yeah. I just told him I’m like, I just don’t think it’s our place, honestly, at all, to be like, this is how you should do anti-racism work for someone who experiences the pain of racism on a daily basis. That’s my thought on his opining on how you’re doing your work.

KS: I have a comment kind of what you were saying. I mean, this whole podcast is about patriarchy. As a woman, I have been told so many times that I’m getting an attitude or, I mean, even as a black woman, like just like those two big things about my identity. I have countless countless amounts of experience of when I have been upset, or simple things: like if I’m upset about something and I want to talk about it, I’m told that I’m being aggressive or that I’m angry or that I’m loud. And then I’m yelling. And I come from like…my mom is she top 10 on level of aggressiveness on just like how she presents herself. Everything she does is just like, wow. And I love that about her, but she gets away with it more than I ever have. I have seen my mom be upset about something and she gets to express those emotions. But when I do it, it’s the angry Black girl or like coming to BYU.

I had the worst freshmen experience, as an 18-year-old little girl, like freshmen, from California where it’s like super diverse and everybody loves each other. And I was told to not be Black. And I took a deep breath before I responded, because I knew in that moment, like this could make or break how I’m perceived in my freshman year. Like right now, as I took a deep breath and I looked at the girl and I responded the way I wanted to, but I like whispered almost and I got up and walked away and I just like, my comment back to her was ‘can you not be ignorant for a day?’ And I walked away and that was it, which is like still really aggressive in a passive aggressive tone, because then it turned into my roommate telling me I needed to apologize to this girl because my response was rude. And I was like, do you guys not understand what she just said to me? And then I like called my mom and like went off and it turned into a huge thing. And there’s more to that story, but not important. I think it’s just more of this idea that…back to pleasing the white man. I mean, as a woman, we walk around eggshells to not say anything that’s too loud or too this or too that. I mean, I’ve done it. So guys would like me, like I have whispered and, even on campus, I’ve been told ‘your friend material, Kylee, not like girlfriend material’. Like my personality is so much in like I walk into a room and like, yes, I’m overpowering sometimes, but that’s something I love about myself. And I can’t like, we can’t continue to lessen who we are to please someone else.

If you’ve never experienced racism, you can’t talk about it. Like you can’t tell me how I should go about talking about it because we’ve picked this quiet nonviolent side and we didn’t get anywhere, and we’ve picked the aggressive side and we don’t get anywhere. So like, whatever works for us is how we should go about.

SS: I think like I was just having this conversation like three days ago so it’s funny that you brought it up. Cause we were talking about so much and I would go.. I can go on history tangent. I love history. Even the March on Washington, President Kennedy made John Lewis change his message and his speech because it was too much. And so like John Lewis is the best. And so it’s been happening forever, right? Like we want to change the message of Black folk because it’s too aggressive, too overpowering. But we, as Black people always have to think about, ‘okay, how are we doing this?’

Martin Luther King was completely non-violent and also the most Hated man in the United States and murdered. No matter what we do, let’s be real, you’re going to think we’re aggressive. And that’s the reason we don’t argue back to people. And that’s why we don’t respond because we have to be very focused on our messaging because we know that we are Black and we know the stereotypes around us.

And so it’s funny when people say we’re aggressive because we have so purposefully not been aggressive with people when we could have been. And we try to really create that messaging on purpose.

KS: And kind of like the comment of, you said, like we’re cornering them. I wish you guys could see the approach: we are very happy smiling people, 99% of the time. So like here we are with our little cheap Amazon microphone walking up with fat smiles, walking up to people and we’re like, ‘Hey, wanna be in a TikTok for us?’ Like we approached them and leave them with the same amount of positivity, regardless of what they say. I think kind of at least like, here’s my idea of where this man’s thought comes from, where it’s like, ‘oh, we’re cornering these like young, innocent people, these 19-year-old kids’. I’m a young, innocent 21-year-old girl, like I’m still learning. So the same way he feels that we’re cornering them and asking these questions that are hard. This is my life. Like I don’t get the option of answering this question because I have been asked these questions since I was a little kid. I have been called out of my name for being a woman. I think we all can relate to those. I’ve been called out for being Black. And so if so, the sympathy and the grace that we were wanting to extend to these young white kids is not extended to us. And so I get what he is saying and, yes, it’s a protectiveness, but who’s going to protect me? Who is going to make my life easier and create this lovely world of ignorance that they get to live in?

AA: And I do have to say for listeners who haven’t seen the videos, just watch them. Cause you can see and you do. I mean, you ask the person if they want to be interviewed. So no one’s being cornered. No one’s being coerced. I feel like you do go, like you bend over backwards to be respectful and kind, and, and really, I think it is so powerful because you just let it stand. You don’t overly praise answers you like you don’t argue with answers that you don’t, you’re just positive.

Okay. I never read comment sections ever. Like I can feel my blood pressure just rising to dangerous levels when I do. But I imagine since people are horrible that there are, I mean, people are wonderful, but they can be horrible. I imagine you guys get a lot of hate in the comment sections, but…I’m just trying to think, like as the devil’s advocate for this one point that my friend was making…are there do these young kids who give answers, do they get bullied in the comment sections?

KS: If we ask you the question and you don’t want to answer it, if they take a second, we say like, ‘Hey, you don’t have to answer it.’ Like, as if you’ve noticed like most of the videos. So every person has asked the question and then there is like a delay. Like, it might just be like, the next person is just their response. Like the question is not asked again. So they have time to think. They have time to ask. They have time to answer the question and then turn around and be like, actually don’t post that.

And we respect that. However, once our videos are posted. It is a hard balance because we can’t control what people say on the internet. Most of the comments, because we do kind of scan them for that purpose. Like, we don’t want anyone to be bullied or like, I mean, bullying in general is awful and we don’t condone that. And so we scan the comments to make sure that nothing is like super direct, like not telling people to analyze themselves or like anything that could affect that person to the point of not a good place. But we also, the purpose is to create awareness. So if we filter everything, then nothing’s going to change. So it is a hard balance. I mean, we’ve had people reach out and ask for things to be removed. And we do kind of have like a way of going about that because we don’t want people to hate themselves because of the answer they gave. Like, we just hope that it creates awareness.

SS: It is hard. One thing I wanted to add is very quickly. Because we knew that it can be a problem potentially in, and like, we would do some of the comments that I like, people definitely talk about it. That’s for sure. But we did, we made a video that talked about like, we don’t like cyber bullying, like et cetera… has like 3 million views. So a lot of people have seen it. And we that’s our second video that you’ll see on our page. So we try to like show that like, you know, idea, whatever your idea might be. A belief might be like, we don’t want to be as harmful as those who hurt us.

KS: I know we have deleted because like, because it’s our video, we have control over the comments. So like there has been a few comments that have been deleted if they’re like super like, okay, that’s a no, regardless, like we exactly what Sebastian saying, like, we don’t want to extend the same hate that we receive, even if it’s not coming from our mouth and even if we don’t agree with it. So like, if it’s something like super not, okay, we delete it. TikTok obviously has guidelines so you can’t say certain things, we kind of just try to go off that. And we are more than willing to like talk to the people in the videos, which is why we don’t say their names. We walk away not even knowing their names most of the time, unless they say it, we don’t tag them. So we try to protect them as much as possible. But there’s obviously so much to that.

AA: Well, there’s so much to that. And what I’m thinking too is like no one could expect you to spend the time it would take. You would need to take that on as a job and be paid for it to, to moderate all of those comments. And I’m just thinking too for listeners who are kind of wrestling with this, I’m just thinking of things that, and, and for people who have listened to my podcast all the way through…I did an episode on LGBTQ history and the way that I was raised and the homophobia that I inhaled from the environment around me, that became a part of me without my challenging it, or examining it until a point in my life where I was like, oh my gosh, what have I imbibed from my environment and knew it’s really hard to make a reckoning with that and to realize like I have caused harm. Like I’m not at fault for what I inherited, but I do have a responsibility for what I do going forward. And I’m just thinking like any one of those people who was interviewed had been taught by their parents and their church and their environment, a certain thing. They say that thing that had been taught, then they have the opportunity and the responsibility to be like, oh my gosh, I said this thing in this TikTok video and then it made me think, and now I think this thing is different than I did before. I learned. I can grow. I can become better. And then that could be a really awesome opportunity for them to go forward as a changed person.

I just know that I’m grateful for those experiences. It might be tricky for them if it was super public and lots of people saw it cause that’s humbling, but then they could post their own video on TikTok and be like, ‘I’m the girl in the video and listen to what I learned.’ You know what I mean? That could be an opportunity anyway. It’s not what I’m saying. In my opinion, it can’t be your responsibility to do all of that work of like the behind the scenes.

Okay. One other question I had was I noticed that one of your very first videos was not about race. It was about the LGBTQ community. And then I noticed that you’re currently doing a fundraiser in preparation for Pride month. So I just want you to talk for a second about how your work is connected to the LGBTQ community?

…the sympathy and the grace that we were wanting to extend to these young white kids is not extended to us. And so I get what he is saying and, yes, it’s a protectiveness, but who’s going to protect me? Who is going to make my life easier and create this lovely world of ignorance that they get to live in?

KS: So kind of back to what you were saying, like we all have our own like bad idea biases, just because of how we were raised. There were a few that I had, I have a uncle who’s gay and I’ve been like, my family is very accepting of the LGBTQ plus community. However, there are certain things that I have learned and inherited that weren’t the best that I had to take time to reflect on and kind of reevaluate why I thought that way and move past that. And I’ll be vulnerable and say that because we all have. As far as the LGBTQ+ community, I think one thing I’ve realized is yes, BYU can be an unsafe place for Black students. However, I don’t fear for my life and…I think when we say unsafe, it’s more like, it’s not like a mentally safe place, it can be really taxing. However, for the queer community, it is an unsafe space as in fearing for your life because we…most people can kind of agree that like racism is not okay and like hating someone for the color of their skin is not okay. However, the agreement on sexuality is like, we can still, people still get away with saying homophobic things or calling people…I mean, even like saying the ‘queer community’, like that’s something that they have taken back. And so that’s okay to say, but even then like being called names that like that aren’t safe and that make people feel like they’re less than. And so I think kind of, because I don’t think I’ve really thought about it until now.

I think our first question was about them because we want to raise awareness that people can cause like physical harm to these people just being themselves. And so kind of like part of like why we’re fundraising for them is because we want to continue to create safe places for them because they don’t always have that and BYU isn’t that place. And so our fundraiser is to have like, to support places in Utah that are close to BYU so they can go there and feel like I can be a hundred percent of who I am. And even in the church, like that’s such a big issue. I think people should be able to love who they want to love regardless of what I think, because it doesn’t affect me and like.

I took psychology agenda and that class really made me think. And my professor just said, if we’re asking people to take away, like one of the most basic human necessities, which is like touch and compassion and love, that love needs to be extended to them. And you better be kind and you better, I don’t care what you believe in you need to do whatever it takes to love them because that’s not fair. And that’s our whole purpose is treat fairness and equality for everyone. This one makes me like, want to cry and like be angry at the same time.

SS: Yeah. The queer community is one of the most hated, I think they received so much hate, especially at BYU. It’s like one of the most unsafe campuses as rated by different websites for that community. And I think the reason that we talk about them rather frequently is because us five individuals care a lot about them, and we care about equality for all groups of people, and so we’re not only here to make Black lives better. We want to make every life that suffers from marginalization and ostracization and of any kind better. And whether that’s one little percent or whether that’s feeling seen or whatever it is like, we’re going to do our best to show that. Okay. You also are seeing now, because I know a lot of people, a part of that community who have reached out and are like, wow, like ‘thank you for making me feel seen. Thank you for showing how it is for me here.’ To me, like that is a huge step because they haven’t been seen. They have, they only can have one authorized, like authorized by BYU club for the LGBTQ+ community. They’re so restricted. The same way, like lack people were like tone police or whatever.

KS: Like, we can’t wear a rainbow on campus.

SS: Like literally, they got people got kicked off of campus for wearing rainbow colors as part of like a small demonstration to support the LGBTQ+ community kick off a campus, physically removed off of the campus because of that, like that that’s unsafe that like, if there’s unsafe, that’s unsafe.

AA: Wow. So speaking of intersecting systems of oppression, this podcast is called Breaking Down Patriarchy so we’re just going to shift gears really quick at the end and talk about how patriarchy and white supremacy intersect. And I just want to ask each of you about. Ways that you’ve experienced patriarchy. And I’m actually going to read a quote by my hero, bell hooks. She said this, she said “white women and Black men have it both ways they can act as a presser or be oppressed. Black men may be victimized by racism, but sexism allows them to act as exploiters and oppressors of women. White women may be victimized by sexism, but racism enables them to act as exploiters and oppressors of black people. Both groups have led liberation movements that favor their interests and support the continued oppression of other groups.” And yeah, I mean, I have read that quote so many times and done so a lot of introspection about it. And for listeners, just thinking about, if you’re trying to wrap your head around, it just think of in 2020 that incident in Central Park, in New York, right? Amy Cooper, this white woman, all she has to do is call the police and say, there’s a Black man threatening me. And maybe she’s a woman with not much power in some context, but she can marshal the forces of white supremacy because they pedestalize a white woman. And so she can just be like, ‘it’s a Black man’ and she has a lot of power over him.

And then conversely, if I were to be married to a Black man, then in my marriage, if it were prior to some changes that happened in the temple recently, he would still have what he thought of as patriarchal, righteous, dominion over me. And so in that context, I mean, before 1990 in the temple, a woman had to promise to obey her husband when she got married, obey. And so in that context, it, you know, then he would have power. And in all marriages, that’s really tricky in a patriarchal tradition that there are a lot of men who think they have the right to tell their wives. Well, anyway, I want to hear your thoughts about that first from Kylee and then from Sebastian.

KS: I don’t know who said it, but the most hated person is a Black woman. This is something that’s like been an issue more recently in my life because I come from a very independent mother, someone who, I mean, she is white, but she is very strong in her independence and like her and my dad’s relationship…Like my dad does not tell her what to do. Nothing. He has no control over that, of how my mom dresses or whatever. I think kind of like my most recent experience with like, where I really realized those things. I’ll get into this a little bit…So my previous relationship was very toxic, but one thing I did notice wore like the comments about me being Black from like friends and like would be times where I was like, ‘does it bother you?’ Or like his family, like a Hispanic family were like, ‘oh, she’s Black.’ And I was like, yeah, what’s the point? And just kind of like the control he had over me or that he felt that he had over me…

The queer community is one of the most hated, I think they received so much hate, especially at BYU. It’s one of the most unsafe campuses as rated by different websites for that community. And I think the reason that we talk about them rather frequently is because us five individuals care a lot about them, and we care about equality for all groups of people, and so we’re not only here to make Black lives better

I wasn’t ‘allowed’ to wear certain things. And like, I wasn’t ‘allowed’ to say certain things or to speak over him. And like, like I said, I’m from like a very independent mother so for a man to tell me that I couldn’t do something, I was like, oh my gosh, like, I don’t know who you think you are. And it just like, but eventually I submitted very quickly and it became very mentally taxing to me. And like I was raised in the LDS church and I’m still very involved. And so like, I dress modestly give or take a few things. And so for someone to tell me that I wasn’t allowed to wear something, made me feel very uncomfortable with myself. And I already had to grow into loving my body so to be told that I wasn’t allowed to wear certain things because of the body that I have, because I am Black. So like naturally Black women have a little bit more curves, and so my curves were an issue because people looked at me and like, I can’t help that. I mean, I can just be confident in who I am. And so learning kind of coming out of that and like, re-evaluating like, oh, like that the oppression I faced because I was a woman. And then on top of that, because I was a Black woman.

So then I was naturally certain stereotypical things, I guess, like loud and curvy and I have this and I have that. Or my hair. Like my hair was an issue because I wear my hair natural and it wasn’t fancy enough for certain things. And he would ask me to do certain things. Things that my dad never even asked me to do. So it’s like, if you’re not my dad, you have no…I just wasn’t raised that way. And so it made me so uncomfortable and kind of lose my identity. And like, that’s kind of something I’ve been working on these last like few months is to really reevaluate who I am and to come into like a new confidence, like I was confident before, and then I lost it. And so being confident in the fact that a man can’t tell me who I am and what I should act and if he wants to, that’s fine, but I’m gonna go over here and you can stay on the other side.

I think it’s hard as like Black women where everything about us is sexualized. I grew up in a very predominantly white area for the Church. So certain things that I wore were inappropriate, but my friend could wear something more revealing and get away with it because she didn’t have my chest, my boobs, she was allowed to wear stuff that I wasn’t and…it just never, it never fully made sense to me. And so, and then realizing that like my Black friends had the same issues, like shorts, like the length of our shorts was always a problem. Or like, just everything you could possibly imagine that you could pick out about a woman is talked about for a Black woman, every single thing we do or white women do the same exact thing and it’s cute and it’s trendy. Like the new trend of like wearing bandanas or head wraps. I couldn’t tell you how many girls on BYU campus that I see do that. And it’s so cute and it’s so stylish, but I was nervous. To wear a head wrap, to a wrap my hair and then like wear hoops. So terrified of the looks that I got that day. Or I have like one of my favorite shirts, I actually wore it yesterday. It says ‘Black Girl Magic’. And the stares that I get from that are like, it’s so demeaning and it hurts a little bit, but like, I have to just push through, I guess, and like walk in some confidence that sometimes I fake, but I think every Black woman who’s listening or just everywhere can relate to like, anything we do is wrong. And it’s hard because it shouldn’t be that way.

AA: Thanks Kylee. Thanks for highlighting that. I mean it’s encapsulated in the title from Francis Beal, the Double Jeopardy to be Black and female. Both layers. So thank you. I’m so sorry. And it’s discouraging too. Cause you know, we did that episode on double jeopardy with Raina who was at BYU with me and to hear how little it’s improved since then is really disheartening. I’m really grateful for you sharing that so that people have to confront that and realize how hard it still is.

KS: I think it is a conversation that continuously needs to happen and as far as making people uncomfortable…sorry, I feel uncomfortable all day.

SS: As a man, as a Back man, I’ve been advocating for people for a long, long, long time and that’s kinda like my personality, but I’ve also had an introspective. They look at myself a lot and be like, okay, why do I feel weird if like I’m spoken over, right? Or like, why do I feel weird if XYZ, you can continually.

That’s something that I’ve had to work with myself inside of like, okay, let’s look at this. Are you continuously speaking over women? Are you mansplaining? There’s a lot of things. And like, as a loud person, I do a lot of things. And so I have to look at myself a little bit more. I feel like, cause I’m like, okay, I like to talk a lot. So like take a back seat, stop talking. Cause I’m going to talk regardless. So I like wait a little bit more sometimes like little stuff that I know, like has like a longer, a bigger effect than I may realize. Cause I think too much, we think about intention and not like output. And that’s what we need to think about. We can’t think about the intention behind our actions because our intentions don’t matter if you’re still hurting people the same.

So as a man, I really try to think about, okay, like how will this affect the woman next to me, white or Black? As a Black man, I really try to advocate a ton for Black women in every arena that I’m in. Speaking up if I’m around pure men and they say something, I’m like, ‘okay, let’s talk’. I’m like, wait, okay, don’t talk about women or Black women. Don’t like call them out of their names. I’m maybe a guy with you, but I’m like…I’m not a very like masculine man. Like I don’t subscribe to a lot of masculinity because it is not me. I wear pink Crocs. Like that’s just me. It’s like toxic. I just like Sebastian and my top two personality traits are the least common for men. And so like I’m happy being who I am. I’m very like very myself. And so I think the more you can advocate for women as a man in spaces, they’re not at the better that, you know, and that is because men will say things, horrible things when women aren’t there and also horrible things, women.

You have to catch them at all times and fight against all kinds of patriarchy and sexism that exists. So when people say stuff or like when they like, oh, this woman is, this girl is this or that, or this I’m like, okay, bro, look at yourself first. Let’s look at yourself and then come back to me and we can talk more. So, yes, like I know times when I have been the oppressor, like I can remember very vividly times when I’ve made so many mistakes. I’m like a bad time for myself. But like I use those themes constantly to reflect on how I was versus like how I need to be better. And sometimes I try to humble myself because I know I can be very prideful and I know I’m also know-it-all; two bad combinations. But I try to like ask like, okay, like how can I phrase that? And so I feel like until use the experiences, look at yourself and really look at like what you’ve done wrong, because I have so many of them specifically with sexism and see how you’re holding up patriarchy, and then determine how you can be better from that.

AA: That’s great. I really specifically appreciated hearing you say like realizing how much power you have that you don’t even know you have. That’s been something for me as even in my marriage, talking with my husband and him not realizing….and him kind of almost thinking that we were regarding each other as equals. And even though intellectually, I always did in this, maybe you relate to Kylee, cause you said you were surprised at yourself in that past relationship at how fast you actually submitted to it, even though you wouldn’t have thought that you would have done that. I don’t know if I’m understanding you correctly, but yeah, exactly that though. But the I’ve felt that too, like in some ways I’m so strong, but then these dynamics that would happen in the marriage where I, and people know my husband do, they, everybody knows he’s awesome and wonderful. And this is part of like how I’ve internalized sexism and I’ve internalized patriarchy where he’d given opinion pretty forcefully cause he’s a forceful guy expecting that because I’m a super strong woman. I would offer my opinion equally, strongly not realizing that I had been so socialized to make him happy as a man I’d been so conditioned to make peace and just go along with stuff and, and to regard a man as my superior, he didn’t realize like, He could help me out by stepping back and giving me more space and being like, is that really what you think?

Anyway, I could relate very much to that, and I’m really grateful. And I think, and this has a parallel, I think also in issues of race, in all kinds of unjust structures, where people who value being colorblind, for example, and they’ll be like, what’s the problem, I’m not a racist. First of all, like they don’t think of themselves as being racist and they don’t realize that the way that they’re behaving is the life that they’ve lived is different. It’s not the same in that somebody might have internalized.

KS: I do it with Sebastian all the time. I mean, Sebastian is a very loud, confident person and I am most of the time and we’ll start talking about things and we might disagree. And there’s times where I’m like, ‘okay’. And he’s like ‘talk’. And I’m like, ‘no’. That’s internalized patriarchy. Cause it’s been my whole life. So even if I wasn’t raised that way, I see it on TV and I hear about it and it’s constantly, I mean, like even commercials and billboards, it’s everywhere.

AA: Well, that’s all I have. And I just want to thank you so much. I’m so grateful you were here.

if I could have people know anything

it’s that it does hurt.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!

I really loved this interview and getting to know more about these amazing young people, what they face every day and what they are doing to try to inform people. I’ve started following them and can’t wait to see what they do next! One comment regarding the church not apologizing for the racist things done in the past. The church NEVER apologizes. NEVER. If you read through the speeches from the Mountain Meadows dedication, they did not apologize for the murders of those people at all, which many people believe were sanctioned by Brigham Young, they expressed ‘profound regret’ not ‘we are sorry.’ I’m sure their legal team went over it very carefully. Regret means: 1 : sadness or disappointment caused especially by something beyond a person’s control I recall my harsh words with much regret. 2 : an expression of sorrow or disappointment. 3 regrets plural : a note politely refusing to accept an invitation I send my regrets.

The church and BYU administration may ‘regret’ what is happening to these brilliant and brave kids, but they will never be sorry for it.