“I realized I shouldn’t be shocked – this is more prevalent than I knew.”

Amy is joined by advocate Mariya Taher to learn more about Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting and discuss firsthand accounts from those affected.

Our Guest

Mariya Taher

Mariya Taher has worked in gender-based violence for over a decade in the areas of teaching, research, policy, program development, and direct service.

In 2015, she cofounded Sahiyo, an award-winning, transnational organization with the mission to empower Asian and other communities to end FGC. The Manhattan Young Democrats honored her as a 2017 Engendering Progress honoree and in 2018, Mariya received the Human Rights Storytellers Award from the Muslim American Leadership Alliance. In 2020, she was recognized as one of the six inaugural grant recipients for the Crave Foundation for Women. Since 2015, she has collaborated with the Massachusetts Women’s Bar Association to pass legislation to protect girls from FGC. After starting a Change.org petition and gathering over 400,000 signatures, Massachusetts became the 39th state in the U.S. to do so.

Mariya is also an extensive writer in fiction and nonfiction and has contributed articles and stories to NPR’s Code Switch, HuffPost, The Fair Observer, Brown Girl Magazine, Solstice Literary Magazine, The Express Tribune, The San Francisco Examiner, and more.

She graduated with her MFA in Creative Writing from Lesley University, where she received the Graduate School of Arts & Social Sciences Dean’s Merit Scholarship and the Lesley University Graduate Student Leadership Award. She also holds a Master in Social Work from San Francisco State University and a B.A. from UC Santa Barbara in Religious Studies.

Learn more at sahiyo.org

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy, I’m Amy McPhie Allebest. One topic that I had hoped to cover on Season 3 is the very tender and difficult topic of female genital cutting, also known as female genital mutilation and sometimes referred to as female circumcision. I had done quite a bit of reading on this subject in my class on international women’s health and human rights. But I always felt uncomfortable in our class discussions because no one in our class came from a culture where this tradition was practiced. And so we were attempting to understand it from the outside.

So I am honored to welcome to the podcast today, Mariya Taher, who is an expert on this topic, both on a personal and academic level, and is a longtime activist against the practice of FGC. I want to welcome to the podcast today, Mariya Taher. Thank you so much for being here with us, Mariya.

Mariya Taher: Yeah, thank you so much for inviting me. Happy to be here.

AA: So I’ll read your professional bio first, and then I’ll invite you to share some more of your personal story after that, if that’s okay.

MT: Sounds good.

AA: Mariya Taher has worked in gender-based violence for over a decade in the areas of teaching, research, policy, program development, and direct service. In 2018, Mariya received the Human Rights Storytellers Award from the Muslim American Leadership Alliance. In 2020, she was recognized as one of the six inaugural grant recipients for the Crave Foundation for Women. Since 2015, she has collaborated with the Massachusetts Women’s Bar Association to pass legislation to protect girls from FGC.

After starting a change.org petition and gathering over 400,000 signatures, Massachusetts became the 39th state in the United States to pass this legislation. As of 2021, Mariya serves as an expert consultant for the Department of Justice Addressing Female Genital Cutting Technical Assistance Project. She’s also the program strategist for SOAR’s Transformative Storytelling Project for South Asian survivors of gender-based violence.

Mariya is also a writer and has contributed articles and stories to many publications, including NPR, Huffington Post and Brown Girl Magazine. She graduated with an MFA in Creative Writing from Lesley University, and she also holds a Master’s in Social Work from San Francisco State University and a BA from UC Santa Barbara in Religious Studies.

So, so happy for all that you’re bringing to this conversation. And I’m wondering if you can share some more about your background, where you grew up and your family of origin, and what brought you to this work.

MT: Yeah, happy to do that. So, again, my name is Mariya and I was born actually in Iowa, but my family moved from there to California when I was nine. So I was raised in California and grew up there. And my parents are immigrants from India. My dad came over in his twenties, so they’ve been here for the majority of their life, so very well situated in the US now. And yeah, I grew up in a very multicultural, multilingual household in California. And throughout my upbringing, I have a very global family, so I was very privileged in that sense of being able to be witness to many different cultures and many different traditions. And I think that that really contributed to what led me into the work that I did. I saw the beauty in this multicultural world that we have, but I also saw how particular traditions can cause harm too. And all cultures, all communities have harm. So it was something that I recognized, just the power of culture and what that means over a person, over a gender as well, too.

And I went to school for Religious Studies. Ironically, the more I studied religion the more I decided I was agnostic. But the more I actually fell into loving religion and recognizing that it’s very influential and has a lot of power over people too. And I then slowly at some point realized I was very interested in gender-based violence work, and started my social work degree, and kept just getting drawn into gender-based violence issues, gender equity. And over time I decided to do some field work with the Department on the Status of Women in San Francisco, which is a city government department there. And they funded a lot of “violence against women initiative programs” as they were known then. And I also just wanted to pursue research on female genital mutilation or cutting at the time too.

So for my thesis in grad school, I decided to do a study on female genital mutilation cutting, or FGM. I tend to call it FGM/C or FGC. In particular I wanted to do it because that is one of the issues that I’ve known about my entire life and it’s because I come from a community that practices it, and so I was very well aware that it continued. And it was something though that wasn’t really talked about in terms of it happening to people born in the US and/or people outside of the African context or African diaspora context. And even when I started to understand, which was in high school, I remember doing research at that time or even just kind of trying to find something on the internet and there really wasn’t anything out there.

So it felt like even though I knew about this I didn’t really, because my experience was not shared in the public realm. And that really led me to do more work on this issue. I went into gender-based violence work, well, I am still in gender-based violence work, but I went into domestic violence work for a while. I did a lot of policy work too, and community-based outreach and education. And when I went back to do my MFA, my Creative Writing degree, that’s the other part of my brain, I just love creative writing too, and I feel like it’s a way to express yourself and really heal and tell stories and relate to other people.

And as I was doing that, other women read some of the work that I did on my FGC study. So after I finished my thesis, I decided to write an article about it. And I really wanted to highlight that this is not something that is done only by… There’s a lot of misconceptions about it and I know we’ll talk about it more, but it’s not done just by uneducated folks. It’s something that’s highly educated. Women might continue too. It’s something that has no discrimination in terms of who it could have happened to. It’s a much more complicated form of gender-based violence than people recognize.

And that led to the other co-founders of Sahiyo finding me and eventually we started this organization Sahiyo, and really recognizing that there was a need for that to create this space where people could share their stories because it just didn’t exist. And now I’m here essentially. The biggest thing about me is that I’ve always been interested in people and understanding how they think, how they operate, how culture and religion really interact with that in our identities too. And I’ve been doing that my entire life.

AA: Wow, that’s really wonderful. And I do want to highlight for listeners too as I was preparing for this episode, I read a lot. There’s a blog on this Sahiyo website so you can read different people’s stories and learn more about female genital cutting in terms of data and stuff, but also people’s stories. So, could you tell or share that website? It’s just sahiyo.org?

MT: Yes. sahiyo.org.

AA: And what does that word mean, Sahiyo?

I come from a community that practices it, and so I was very well aware that it continued.

MT: So Sahiyo is a Bohra Gujarati, so the community I grew up in is known as the Dawoodi Bohras, and Gujarati is a language from South Asia. The actual word is “saheliyo” which means friends. So that’s why I say it’s a Bohra Gujarati word, Sahiyo. It means female friends. And it really reflects the way that our organization, the co-founders, wanted to approach our work is really thinking about it being community-based and approachable and really about us coming together to share.

AA: That’s beautiful. I didn’t know that this whole time as I’ve been reading on there, I somehow missed that! That’s really, really lovely. Well, let’s dive into the content of female genital cutting. And I want to start with just the basics in case listeners have not heard of this, or maybe have heard of it with different terminology; it used to be referred to as female circumcision, I think.

I’ll just ask you the most basic question, of what is it? What is female genital cutting? And maybe you can explain the different types, there are different levels that happen. And just a content warning for listeners, you can see from the title that this is not a particularly easy topic to talk about, and this will involve discussions of violence. So take care of yourselves accordingly, and it might not be the best episode for very young listeners.

But don’t hold back, Mariya, just tell us exactly what it is and we can talk about all of the implications of it too.

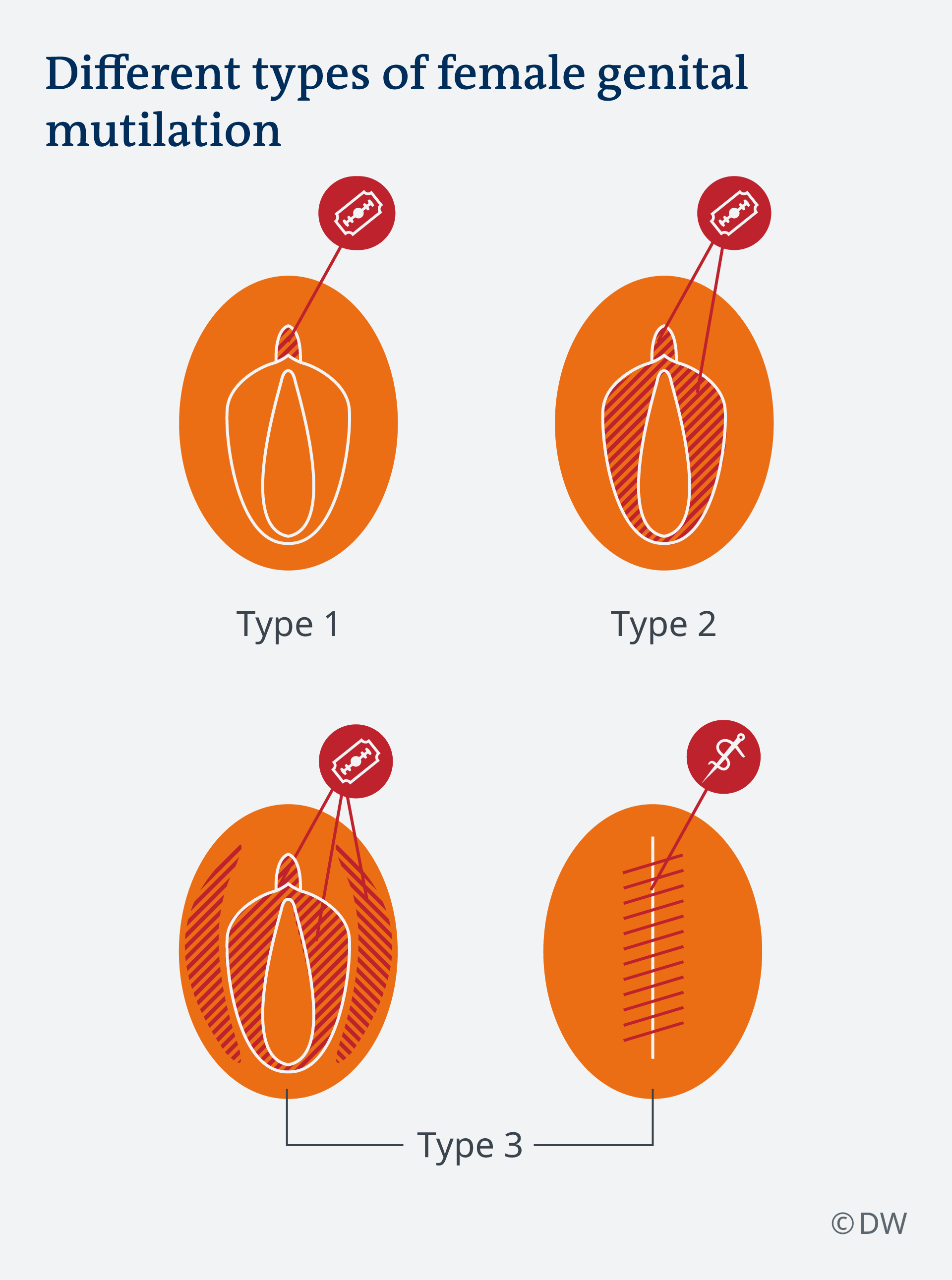

MT: Yeah, definitely. So, female genital cutting is basically any alteration to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes. And there are various forms of female genital cutting. The WHO (World Health Organization) has essentially classified it into four categories. These categories are very broad in themselves, and they range from Type One, which is considered one of the least physically severe – does not mean it doesn’t have any negative impacts, but it just means in terms of what is actually done to the female genitalia. So anything from part or all of the clitoral hood to part of the clitoris can be removed and that is considered Type One. Then Type Two becomes more physically severe, meaning that again anything in Type One can happen, so part or all of the clitoris can be removed, and then also part or all of the labia minora. And then Type Three can be the most severe, which essentially can include Types One and Two, and then it also can be essentially all of the external genitalia can be removed and then it’s stitched back up to leave one hole for menstruation, urination, and sexual intercourse. And that is oftentimes known as infibulation, too.

So again, they range in severity. And then there is a Type Four. Type Four, though, is in another category, so anything that essentially doesn’t fit into the first three types. So this can include piercing, cauterizing, pricking, any other type of genital modification as well for non-medical purposes. And they’re very broad. So I think what’s important to know and acknowledge is that female general cutting is not one particular procedure. It is a whole range of different physical alterations that can happen to a woman. And then the type that has happened depends on that culture, the community, the geographical region that the person is in, the person that is performing it on that girl. So there are a whole host of reasons for how it occurs and why a person might get a specific one.

I also want to say that most people when they have heard of FGM/C, they think of infibulation, so Type Three. But from the research we know at this point it actually only counts about 10%. So most cases are Type One or Type Two. So that’s also important to recognize and acknowledge.

AA: Okay. So speaking of the different regions of the world where it’s practiced and how that determines the different types, could you talk about some of the differences based on location and maybe talk about how old the girl is usually when she has this done, and then who is the person who performs the procedure?

MT: So FGM/C can happen to anybody who is identified as a girl and is anywhere from birth to adolescence, although it can happen to adult women as well. And it’s something that depends on the region, again, in terms of who you see it happening to. Typically, you’ll see it happening from ages five to seven. And in the Bohra community that I grew up in, the age was seven that you always heard about it happening when it was performed. In Indonesia, it oftentimes comes along with a birthing package. So it’s actually something that is legally sanctioned and something in hospitals. And so it happens in infancy. And then–

AA: Woah, wait. Sorry, I’ve never heard of this before. So just like a circumcision on a boy happens in the hospital, they will perform it in the hospital on a girl? Like if the parents want them to, or what?

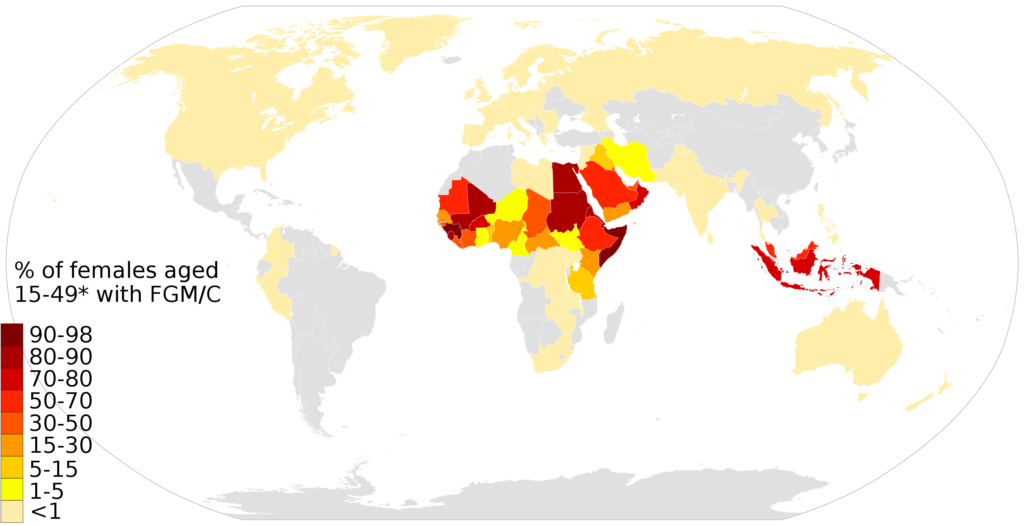

MT: Yeah. Indonesia has a really high prevalence rate, too. And some interesting thing is that again, misconceptions around who it happens to, and we do know it happens in Asia. I’m gonna jump a little bit into statistics. I just want to bring this up though. So there is a global statistic that FGM/C, the global figure is 200 million. That 200 million women and girls are impacted by FGM/C. However, this statistic is only based on 32 countries in the world. And these are 32 countries where FGM/C has been measured by national level survey data, mostly within Africa and the Middle East.

Before the number was 200 million, it was 140 million and that was within 30 countries. There were no Asian countries. Indonesia was added and the number jumped to 200 million. And that’s the addition of just one country within Asia where there was recognition. And this happened in the last 10 years that that country was added and we realized that it is actually a huge issue. And it is very prevalent in Indonesia as well. But I share that because FGM/C has been hidden in so many ways, on so many levels, and one of those ways is even the data that we have out there, and at some of the highest institutions, thinking about the UN.

We had another study that was done a couple years ago from three organizations, and they found that FGM/C has been reported in 92 countries around the world. So there’s a huge gap in terms of the data collected by the UN and what we actually know in terms of where it happens. It’s just that in some countries, the only source of information might be anecdotally from those survivors or maybe media reports. There’s no national survey so it hasn’t been counted towards a global figure. So I do want to bring that up because I think, again, when we talk about FGM/C and the prevalence, there’s this notion that it happens only in Africa or in small villages. And not to say it doesn’t happen in those places, but it also is much more broad than that. And it’s something that’s been hidden, and that silence has worked in many different ways, including who acknowledges that it happens.

AA: So tell us a little bit more about, again those questions of who performs these procedures. And like you’re saying, that’s going to vary a lot depending on where you are. Because I had never heard of it practiced in a hospital, for example, until this very moment. So yeah, tell us a little bit about that variety.

MT: Yeah, so for a very long time and traditionally the way it happened was by midwives or traditional cutters within a community. And it could be that it was passed down generation by generation, but they were the ones that actually did it. So it could be in unhygienic circumstances, and different tools could be used from razor blades to other sharp materials as well.

However, we’ve seen a change, and I believe in the US we actually see more of it this way. And in Indonesia, as I mentioned, it can happen in hospitals. It’s been medicalized, meaning that healthcare providers are performing it, and typically healthcare providers that are belonging to a community that practices it. It’ll be done in secret depending on where it’s happening. So in Indonesia there is no law against it, but here in the US there are laws against it. And actually in 2017, there was a doctor that was charged with performing it in Michigan. And that broke a lot of stereotypes when that happened because it was a doctor. So that just shattered a lot of people’s illusions around who performs it. Not people who are in those communities, people who are in the communities or advocates, we’re aware of it. But it also was somebody who was born and educated in the US, it was somebody who was from a South Asian background, or her ancestors were. And very educated too. So again, it broke a lot of stereotypes around who can happen to, and it was slowly revealed that hundreds of girls across the years had been cut too.

And that’s just of somebody we’re aware of. It was the first ever federal case, under the federal law that somebody was brought up on those charges. But I do believe that we’re seeing more and more medicalization of FGM/C. Almost in a way to try to make it safer, that’s kind of the thinking behind it: if a medical professional does it, it’s safer. But it’s still not safe. It’s happening to girls that are too young to consent to what’s happening to them. And also you can’t know the impact that it has. The nerves in your genital area and your clitoris are so sensitive. And I’ve had other doctors tell me this too, that you can have much more extensive damage than even is seen with the naked eye. So there are survivors out there who, if they have some of the least severe forms, might go to a doctor and they don’t see any harm, but that doesn’t mean there hasn’t been harm there physically too.

AA: And you’re saying with these cases in the US like the one in 2017, this will be a doctor who has a medical license to practice whatever field they’re in, right? And then secretly a family will approach them and say, “hey, you’re a doctor, can you do the procedure?” And they’ll secretly perform it in somebody’s home?

MT: No, it was in a health clinic.

AA: Even in the US?

that’s kind of the thinking behind it: if a medical professional does it, it’s safer. But it’s still not safe.

MT: But it was done after hours, so it’s all done secretly. I mean, it could be in somebody’s home, but in this particular case it was in another physician’s health clinic after hours. But I want to add something, that FGM/C is not new to the US either. Meaning that it’s not something that other communities have brought from other countries. There’s this history that’s just been forgotten in the US. Clitoredectomies, which is generally Type One, so it’s a form of FGM/C, have been performed in the US and in many countries in Europe up until the 1960s to treat women for hysteria, lesbianism, and to stop masturbation. And we’ve had a survivor who is a huge advocate, she’s amazing, she has come out and shared her story.

And it’s something that, again, it was in medical textbooks. Actually Blue Cross Blue Shield covered it by insurance too. So, this is such a hidden practice in so many ways, but when you dive deeper you start to kind of understand this idea of controlling your own body or a woman’s body through modification of their genitalia. It has this long history and it’s kind of shocking.

AA: I’m shocked. Yeah, I had no idea. Oh my gosh. Well, I was going to ask you a different historical question, but I’m so glad you brought that up first. Because I’ve done a bit of reading on this, I took a Women’s Health and Human Rights class a few years ago in grad school and did a lot of deep reading and I did not know this, so I’m so glad you brought that out.

But I was going to ask more about the roots of FGC. One thing that I’ve learned, and you can correct me if I’m wrong, but I did learn about it mostly in an African and Middle Eastern context, but what I learned was that it’s practiced within Islam, but it predates Islam. That these were traditions that happened before Islam came to these areas.

MT: Oh yeah, for sure.

AA: Do we know where it came from and then how it got to all the different regions where it’s practiced today?

MT: Yeah. FGC is something that predates all the major Abrahamic religions, so it predates Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. And there are various theories around how it emerged, there is evidence that it’s been done in Egypt on mummies actually, so we’ve seen it there. There have been theories that the Romans practiced it on their slaves as a way to control not just sexuality, but the idea of pregnancy, particularly in the slave trade. There also, though, were ideas around it being something that was done to the elites. The thought was that the elites were doing it, the royals, and then it was something that the common lay people started emulating as a way that was like a social standing type of ritual. And so that was one way it might have been passed down to the general population as well.

But there are various theories, very old customs. So again, it is something that even though maybe today it might be associated with certain– And I want to really emphasize that another misconception is that it’s an Islamic practice. And the thing is that it might be justified in a few different Islamic communities or cultures or some religions, but it doesn’t mean it’s an Islamic practice. Also the same thing, there are Christian communities that we know practice it, even here in the US. That’s another thing I didn’t mention, was we actually know it’s happening in some fundamentalist Christian communities, white communities here too. And that was something that even shocked me a few years ago and then I realized I shouldn’t be shocked. I’m realizing this is more prevalent than I knew. So I just want to emphasize that religion can be used as a justification within a community, but it’s not connected to the origins of why this started. So hopefully that makes sense.

AA: Yeah, yeah, definitely. So, one more question about the technical parts of how this is done and kind of the medical, well not medical, but the physical aspect of it. Like you mentioned before, it’s done to control women’s sexuality and obviously if they’re cutting out the clitoris it’s to keep this girl or woman from experiencing sexual pleasure, meaning that then she won’t have a sexual drive, right? So what are some of the physical effects, like you mentioned a little bit that obviously those nerve endings are so, so sensitive. Can you talk about some of the physical and then the psychological and emotional effects that this has on girls and women?

MT: Yeah, so it really depends on the type that happens and then the environment. But some of the health impacts can be severe bleeding, infection, frequent UTIs, actually I remember there was a urologist a few years ago who reached out because she wanted to do a study. Seeing that maybe even folks who get Type One might be having a lot of health issues around UTIs. Because I think a lot of times there’s a thought process that Type One might not have as many physical impacts, depending on the type you get done and if it looks like nothing’s been done.

But even amongst those types, there can be physical impacts, difficulties in childbirth, difficulties having sexual intercourse. I’ve heard many survivors talk about menstruation issues even though we don’t know for sure the connection impact with that. But yes, unfortunately– I mean, all of those things are unfortunate, but also there have been cases where it’s led to death, too. And emotionally, mental health, that I hear about all the time. Again, regardless of type there are many survivors who will tell me it’s the emotional, psychological impact that lasts so much longer for them. Even if they have lifelong health complications because of their FGM/C, it’s the fact that if you’re old enough to remember, you have trusted individuals, maybe in your family. that have come and taken you to have this done. And that sense of betrayal, that fear that, that trust that’s being broken, those can have these long lasting impacts on a survivor as well too. So I’ve heard about PTSD, I’ve heard about depression, anxiety, trouble sleeping, generalized body aches and pain, psychosomatic types of impacts as well. So it’s a whole range of different issues that can occur.

AA: Yeah, it makes sense. I know that some of the anecdotes, kind of the cases that I read about, where sometimes it’s presented to this young girl like “we’re gonna have a party for you!” And she’s like seven and she shows up and the party is that then she’s held down by her grandma while someone else she trusted in her family cuts her, and it wasn’t explained to her what was happening. Would you be comfortable sharing any stories?

MT: Yeah, they range so much. What you just shared is definitely one of the stories that I’ve heard. I also want to say there are survivors out there that don’t have any memories of what has happened to them. And if you think about trauma, one of the ways we cope with trauma is blocking out painful memories. So it’s not unusual to hear that as well. And I’ve heard survivors who have talked about how they don’t remember what happened but in learning about it, have had to deal with that realization and that impact and have had almost PTSD because everything they perceived was different. I’ve also had other people who suddenly, you know, this story comes up often particularly in college. A lot of students that have been in anthropology classes where they might learn about this practice recognize that it happened to them. I’ve had that story multiple times and then everything kind of comes back and floods over them. And maybe it’s not just an anthropology class, but that’s what I’m remembering, is a couple of people who have shared those stories.

But I’ve often heard people say things like, “oh we didn’t learn about it until college,” or “that’s when I started thinking about it,” or “when I was sitting in this class and…” You just never know where you’re going to learn about or hear about it, or if there’s a survivor. And no one really in that classroom probably realized that they were talking about it as an abstract thought, because again, it was being taught as this tradition that happens in this far away culture, religion.

I’ve had stories where people have talked about going to a health clinic or being told that they had to get a worm or an insect removed. There have been, it depends on the culture and community too, but some instances where it’s celebrated and other instances where it’s not really celebrated and just kind of hurried along but you’re supposed to grunt through the pain. And it just varies. They’re all connected but they also are just so different. The stories, one from the next.

AA: Could I ask what the stories were that you heard growing up in your community of origin? Like you said you kind of grew up knowing that it was a part of your culture. What did that sound like to you as you grew up?

MT: Well, for me it was very normalized. I mean, I actually underwent it too, but I didn’t really think much of it until I was in high school. It was just so normal. Everybody underwent it. So it wasn’t something that I questioned. And it wasn’t until another person who was really negatively impacted, and I remember they used the word “female general mutilation” and that was the first time I was starting to think about it more and then learning more about it. And I think it just depends, again, for some people it’s easy to remember every single detail and relive it and its impact. Part of the reason we created Sahiyo is so people could share their various stories and connect. But then there are other people, like I said, that maybe hadn’t really thought about it and have said that they didn’t want it to continue, but they don’t know if it’s impacted them or not. And how can you know if it impacts your sexuality if you– particularly I hear this all the time, like I was seven, I don’t know if it impacted my sexuality at seven or anything. So it’s just a lot of not knowing what has happened to you. I think a lot of questions.

But the thing is, you don’t talk about it really in communities. In the community I grew up in, you were told it was a woman’s issue or you were told you needed to keep it quiet. And that was drilled into you. And so that’s part of the reason it continues generation after generation, this idea of silence. And it was very common for men not to know that it happened. And it’s changing now I think really with social media and more survivors coming out and sharing their stories, but it was not unusual to hear men say, “I had no idea this happened in the Bohra community.” So in our work, we engage the entire community so that means also engaging men too. And I remember one person wrote a story on our blog about how they had no idea about this and then once things in the news started happening with this Michigan case, they one day had a conversation with their mom who was pretty devout, but the mom very much disagreed with this practice and told her son about the practice because he was asking. And it ended up being kind of a bonding moment for them too, but it was something he did not know at all about and only learned about in his adult life.

Even if you haven’t had it done, because there are people that are deciding not to and that’s really amazing. But there’s a lot of pressure that can happen and it’s not uncommon to hear mothers, and not just mothers but maybe others in the family tell their daughters to just pretend you’ve had it done if anybody asks.

AA: Oh wow.

MT: So there’s silence there too. This idea that like you can’t even acknowledge you haven’t had it done because of repercussions, maybe someone would force you to have it done or maybe you’d be looked at differently. And so you keep it quiet in that way. And that silence also reinforces it, continues it. Because there’s a belief, there’s actually a term, it’s called “pluralistic ignorance” and it’s the belief that everyone’s having it done so that’s why we need to do it. But in reality, maybe nobody wants to have it done.

AA: Mm-hmm. And so this is a way that a mother could protect her own daughter, but then it doesn’t challenge the system.

MT: Exactly.

AA: I get it. I came from a very high-demand religion where there’s a lot of conformity and a lot of everybody looking at others for the signals and that everybody’s kind of in the club. And it is very, very hard to make any departures from that.

That leads me to ask you what that was like for you to speak out against it. If you come from a family that practices it, has that been hard for you in your own family and community?

MT: It has at times. I’m in a very different place now than I was probably six years ago, even. I’m in a much more comfortable place now, but there have been moments where there were arguments. And my parents are against it. And there was no federal law in the US when it happened to me either, and there was no internet, there was no awareness. It was very much that you did what your family members told you. And so my mom had it done because she had heard from her family members. And my mom told me later on that she had to have another female relative come with us because she was afraid of seeing me in pain and didn’t want to see me and couldn’t have it done. And I actually remember her holding me and trying to comfort me, too. I don’t have a lot of memories, but I do remember that.

And I get it, too. It was because, you know, she was coming from women who were telling her “yeah, you have to have it done.” And she wasn’t hearing any opposition to that idea that you can’t have it done. And again, there were no laws, there was no survivor movement really at that time. And it’s a very different context now than it was for her. It happened and my dad had no idea about it, and he has many sisters, and some of his sisters decided not to have it done to their kids. But my dad had no idea until he learned about this from my mom. And it was something that felt like, “oh, okay, I guess if it’s a tradition or culture.” Even the idea, even that question hadn’t come up yet.

But now it depends on who it is. But I have had instances where there are family members who… in the Bohra community, in the Bohra context, it’s viewed like if you’re attacking it, you’re attacking the entire community. And so those who are really devout in the community, who are the ones that don’t question anything, very much following everything, they will oftentimes be upset that you’re sharing, like you’re airing out your community’s dirty laundry, or like you’re giving us a bad reputation. And so we have seen that happen and there’s often a dismissal of trying to say that what happens in the Bohra community, khatna, because it’s Type One and it’s just a piece of the clitoral hood – at least this is what is explained is what happens even though I’ve actually heard stories of it ranging – that it’s not that severe and it’s not mutilation. And oftentimes the mutilation they’re referring to is, again, that stereotype that I mentioned that it’s always infibulation. And there is actually almost– not almost, it is racism that’s underlying it too. Where it’s like, “We’re not doing what they’re doing there, so we’re civilized. We’re okay. We would never harm our girls. How could you even say that this is the same as mutilation?”

And actually, can I share a story? I was thinking about when you were talking about opposition and the story just came up in my head. I think for me, one of the biggest challenges in this work is the emotional toll it has when those who I refer to as pro-FGC folks come out at you, and there are pro-FGC folks. And one of the projects that we do at Sahiyo is a digital storytelling project where we have survivors come together and they get to tell their stories. They get to create a little script, they get to learn some video editing, and they make a three minute video about any story related to FGC that they want to tell.

And we’ve done seven cohorts, but the first cohort we did was in Berkeley, California, and then we did a small screening at a public library of those videos that came out of that workshop. And we advertised the video, the screening, and that was gonna happen. And we did a panel after the videos were all shown, and I was on the panel too and then two partner organizations that were working with us. And then I suddenly remembered, I finished answering a question and the Bohra community has specific clothing that they’ll wear and it’s a kind of sign, particularly those who are really, really devout will wear it all the time, it’s become kind of a required outfit. It wasn’t required when I was growing up, but now it is. So they walked in and I immediately recognized them as being Bohra because they were wearing the outfits and they came and suddenly sat in the back. And this was during the panel, the question and answer. So they had missed all the videos, and they were listening, and then I remember that the man raised his hand first and he asked me, “My question to you is, if this is so harmful, then where is the data? Where’s the research proving that this is harmful?” And there isn’t a ton of data and research, but that’s kind of an approach that’s been taken, it’s just like there’s no data showing that it’s harmful, so it’s not harmful. You guys are just making it up, basically.

And I just froze, actually. And I could not talk and luckily like my colleagues that were also my friends, they took over and they were able to talk, but I did not know that this was going to happen. And I was just triggered in that moment and really could not speak and was feeling myself getting angry. Because I knew they were there to rile me up and to not be supportive in this environment but to basically disavow all the survivors that had shared their stories, and they didn’t even see the stories. And then the woman, she was from the Bohra community, she had been cut as well and she raised her hand too and was talking, and they knew who I was. That’s the thing too, is that a lot of advocates who come from communities can be sort of tracked or followed. And so I remember her being like, “You’re Bohra, right?” And I was not wearing the Bohra outfit or anything, but I knew she knew specifically who I was. And then she’s like, “You know, I’ve been cut and my friends have, and we’re all fine.” But basically like, saying it’s the same thing as domestic violence just puts it in such a bad light. And she couldn’t believe that we would be doing that.

So this happened and I was just frozen. And I was scared they were going to come talk to me directly and I was like, I can’t handle this. And even though I’m an advocate and I’ve had conversations, in that moment I was so caught off guard and was so angry that this was happening. And luckily afterwards, all the other people in that crowd, everyone was witnessing this interaction. And there were quite a few folks that went up to them and kind of ensured that they didn’t come to talk to me, and kind of helped protect me in a way. And I was very supportive of that. And they left eventually. So it wasn’t a violent interaction, but it was combative, you know, verbally. So talking about opposition, I just remembered that that had happened.

AA: That’s awful. I’m so sorry that that happened to you. And I can totally imagine it, that you would just freeze and almost like your brain doesn’t even, at least when that’s happened to me, like it’s offline. Like I have no access to words or data, even if I know it. And then afterwards I’m like, why didn’t I say this? Why didn’t I say this? It just can catch you off guard like that. I’m so sorry. It’s awful.

MT: Yeah. Thanks.

AA: Well, one of the other questions that I wanted to ask, and it keeps coming up through the whole thing. So you just talked about a couple where the man and the woman were both defending the practice, but you’ve mentioned several times that sometimes men didn’t even know that this happened. And I mean, this episode is part of a series of Breaking Down Patriarchy, right? So how is this a patriarchal issue if it’s women who practice it almost one hundred percent of the time, is my understanding. It’s women who do it to women, and sometimes men don’t even know. Then how does it have roots in patriarchy? Or does it?

MT: That’s a very good question. Yeah, I mean, it varies from community to community in terms of how aware men are. And some other communities, for instance, like I know within I believe it’s the Somali community, I’ve had survivors who have told me stories where it impacts who they marry. And you’re brought up to believe not to marry an uncut woman because they aren’t considered clean, or they’ll be promiscuous and they’ll run around and they might be called a certain name. And I can’t remember the word for it, if they’re not cut. So there can be a shaming and stigma for not being cut as well. And that that is, again, even though it’s something women are carrying on to women, it is rooted in this idea of controlling your bodily integrity and the idea that your sexuality is done for the pleasure of men. Right? So this idea that you have to be virginal, chaste, pure. And that FGC helps you so that you’re ready, or it increases your marriageability rate, your odds, so that you’re considered more eligible, too. It’s a social standing type of thing.

Like I mentioned, there might be other reasons given for it, culture or tradition, religion. But there is this idea of control around it that you often hear about. And I think it’s important to recognize that control is coming and it’s being enforced because of this certain stereotype around how a woman is supposed to be or behave, or this is the identity. This is how you achieve that. And it’s happening to children who are too young to consent or fully understand what’s happening to you. And it’s really, again, even if you think about how before the cutting is happening, this girl is exposing her genitals to strangers, and that’s something that you’re typically taught you’re not supposed to do. And before any of the cutting is happening, that is occurring. And I think if we even think about it that way, that would be considered abusive if you explain it in that type of context.

it is racism that’s underlying it too. Where it’s like, “We’re not doing what they’re doing there, so we’re civilized. “

AA: So yeah, that’s sexual abuse, just that moment. I had not thought of that either. Yeah, totally.

So one quote that I wanted to share from a blog post on the website was a woman who said that the messaging she got throughout her life were things like this: “This will help your marriage.” And “This is to make sure women’s urges are controlled,” or “These things are done to make sure you are loyal to your husband,” or “Women need to appease their husband.” And she said that these messages went along with the cutting but weren’t even necessarily present at the moment she was cut. But it was the messaging that went along with it that did, she said, even more psychological harm than the cutting itself. And so just to this point, this topic of how it comes from patriarchy, sometimes it is women who keep the ball rolling and it’s not even necessarily the men in the moment who are actually doing it anymore.

One thing that comes to my mind is even with beauty standards around the world, like we’re going to have an episode on foot binding in China. And I even think about plastic surgery, for example, in the United States, in the community where I live. Or women starving themselves to be super skinny. And then if I talk to the actual men in my life, like my husband or my brother or my dad, they’re like, “Oh my gosh, I feel so sad. Why do women do this to themselves?” It comes from patriarchal beauty standards, from hundreds of years of women needing to be beautiful so they would be selected by a man to be taken care of by that man because they had no other option in this world. And so the practices have exceeded their expiration date socially, where it literally doesn’t even make sense anymore. And we now do it to ourselves and each other regardless of whether the men in our lives actually require it.

MT: Yeah, it’s become a social norm. Social norms are powerful, tradition is powerful. And it’s something that I’m always saying. There can be beautiful traditions, but traditions are also something we stick to fiercely, and it’s not easy to end a harmful tradition. And that’s what FGC is, a harmful tradition.

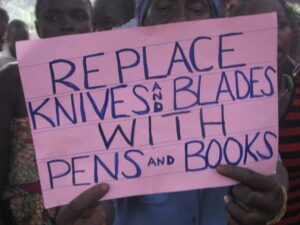

AA: Yeah. I so appreciate this episode, and you’re helping to bring so much nuance and so much variety to it and helping us understand and have compassion for people who practice it while still wanting to end the practice. And to recognize how it feels from the point of view of the people who engage in these practices and how complicated it can feel. So can you tell us about some initiatives to end this practice?

MT: Yeah, sure. So Sahiyo, like I mentioned, we do a lot of digital storytelling type of work. And that is something that we’re constantly looking for support to be able to host more workshops and forums for impacted community members to come together so that they can have safe spaces. Creating safe spaces is huge. Every single time we have an event, somebody will come up, if not more than one person, and just tell me, “I’ve never been able to talk like this with other people that I’ve been related to.” They’ve just never had that opportunity because they had to be quiet. They couldn’t rock the boat in their community. So it’s amazing how much that can do for healing.

But we also have a male engagement program which is called Bhaiyo, which is kind of a play on Sahiyo but for brothers. And we do a lot of research too, but there are also other organizations. I think what folks don’t realize is that there is a growing movement in the US when it comes to FGM/C. So for the first time, a couple years ago, the Department of Justice Office of Victims of Crime gave out some funding to a few organizations across the US to do work around prevention and intervention. So prevention meaning education, outreach. How do we reach out to these communities? Sahiyo does a lot of prevention work, too. We run some digital media campaigns and try to get community voices, but other organizations are doing that too.

There is research going on and we also do some trainings, but around how to educate healthcare providers, for instance, who might come in contact with survivors or other frontline professionals, social workers, midwives, other folks that might come in contact. And that’s huge because for a very long time there wasn’t recognition that FGC occurred in the US. And then when there was recognition, a lot of the funding that the US government gave was for international programs, so the fact that we actually have funding domestically now is a huge, huge thing. And it is kind of amazing to see that there’s actually an inter-agency group of a few different federal government departments that are really thinking about this issue and trying to integrate it into some of their existing programs around gender-based violence.

And I just want to mention that there’s a lot more work to be done, but I wanted to help highlight that there’s a shift that’s occurring and it’s very new, but it’s like in the last 10 years overall. We are seeing more work there, and there is a US network to end FGM/C. So if anyone’s interested in really trying to understand what’s going on across the US, I definitely recommend Googling them. If you Google US network to end FGM/C, you can find the page and see what resources exist, and then also learn some of the latest news. Always check out Sahiyo’s website, of course, but if you are curious about the broader movement in the United States, that’s a great resource.

AA: Fabulous. And I’m sure it’s on Sahiyo’s website too, but as I was preparing for this episode I was looking at the UNICEF website and the United Nations. I know they made February 6th the day of Zero Tolerance Toward Female Genital Cutting. And there are these international organizations too, that are working to end it. And so that’s a place to look as well. Is there anything else you’d like to share, Mariya, that we haven’t gotten to yet?

MT: Yeah, one thing I want to share, and this is really I have to say because survivors have come to us and have really helped us to understand this better, but there are survivors out there who identify as non-binary and they have undergone FGC. And they underwent FGC because they were looked at as being a girl. And it’s something that helped me to realize, and it’s helped my organization too, to realize that another impact of FGC is that it takes away a person’s ability to really identify with their gender identity. And that’s a whole other consequence of FGC that I think we need to bring more attention to and recognize. And so I’m very thankful for those survivors that have come up and really talked to us and how they’ve said that even in the literature that’s out there on FGC, it’s always referring to girls and women and sometimes they feel out of place in that recognition. So I do want to uplift that point when we think about FGC, recognizing that there are many that are undergoing it. And because they were identified as a girl, they were forced to have this done to them.

AA: Ah, thank you for sharing that. I want to thank you so much for being here today, Mariya, and I so admire your work. I admire your courage in breaking the chain in your own family, your own community. That is incredibly hard to do and I just have so much respect for you. So, thank you for your work and thanks again so much for being here and sharing your expertise with us today.

MT: Thank you! I’m so glad I was able to have this conversation with you.

It’s not easy to end a harmful tradition.

And that’s what FGC is, a harmful tradition.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!