“you can’t be what you can’t see”

Amy is joined by Former Representative Mary Chung Hayashi to discuss her book, Women in Politics, and the barriers which dissuade women from entering the political sphere including ambition gaps, the imagination barrier, perceptions of motherhood, and the challenge of fundraising.

Our Guest

Mary Chung Hayashi

Mary Chung Hayashi is an award-winning author, national healthcare leader, and former California State Assembly member. With a distinguished career in public service, Mary has spearheaded substantial reforms in mental health services, championed gender equality, and forged powerful, unprecedented partnerships for social causes that previously had no financial or public backing. Recognized as Legislator of the Year by the American Red Cross and the California Medical Association, Mary has also been featured on Red Book’s Mothers and Shakers list and Ladies Home Journal’s Women to Watch. As principal of public policy and advocacy solutions, she has successfully advised business and policy leaders on some of today’s most complex public policy matters. Mary remains a steadfast proponent of social justice expansion and the rights of underrepresented communities.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: One of my favorite quotes from Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is: “Women belong in all the places where decisions are being made.” This quote really inspires me and I am passionate about women participating fully in our democracy. But at the same time, when I think about getting involved in politics beyond voting and the occasional fundraiser, I kind of want to hide in my closet. So I was intrigued by the book Women in Politics: Breaking Down the Barriers to Achieve True Representation by Mary Chung Hayashi. I just finished reading this book, I loved it, and I’m so excited to discuss it today with the author. Welcome, Mary!

Mary Chung Hayashi: Thank you, Amy! I am so happy to be here. And everything you just said kind of summarized what I wanted to say, so I can see that this is going to be an awesome podcast. Thank you so much.

AA: I’m so excited to have you here and I really did love your book. I’ll just start by reading your professional biography so listeners get acquainted with you professionally, and then I’ll ask you to share your personal story afterwards.

MCH: Perfect.

AA: Mary Chung Hayashi is an award-winning author, national healthcare leader, and former California State Assembly member. With a distinguished career in public service, Mary has spearheaded substantial reforms in mental health services, championed gender equality, and forged powerful, unprecedented partnerships for social causes that previously had no financial or public backing. Recognized as Legislator of the Year by the American Red Cross and the California Medical Association, Mary has also been featured on Red Book’s Mothers and Shakers list and Ladies Home Journal’s Women to Watch. As principal of public policy and advocacy solutions, she has successfully advised business and policy leaders on some of today’s most complex public policy matters. Mary remains a steadfast proponent of social justice expansion and the rights of underrepresented communities.

Well, Mary, that’s a very impressive biography. I’m so excited to hear more about those details and I wondered if you could start us from the beginning. Where you’re from, your origins, your education, what makes you you, and what brought you to the work that you do today.

MCH: Thank you. That bio was written by us so of course it’s going to be good. It’s always embarrassing when I hear it, you know, but I appreciate the shout out. I tell people that I’m not a professional author, but this is my second book that I published. And I realized that I really love to publish because when I came to this country and I was so lost because I was 12 years old, my parents were very conservative, traditional parents. They expected girls to get married and have kids and that was kind of what their expectation was. And I went to Cal State Long Beach and during my second year, I was 19 years old, I took a women’s studies class. And I initially thought that it was about how to be a good mom or a good woman to a spouse or something like that, like a home economics class. And when I took this class, I started reading about women, feminist literature, and that really changed my life. So I keep wanting to write because just thinking about what that did for me, what the class and the literature did for me, I want to offer women and girls the same thing.

And so I find I keep publishing because one of my goals in writing this book is to inspire other women to write their own life path and to see that they don’t have to be controlled by their ethnicity or family or background. And that’s really the goal. And I lost my sister to suicide when she was 17, I was 12. That was the same year that my family immigrated from Korea to California, and I didn’t speak any English. I grew up in Orange County where very few, I mean it’s very different now, but at the time there were very few Asian American families or any minorities, really. I just grew up with people who used to call me Connie because they only knew one Asian person, who was Connie Chung on television. And I didn’t mind it because I thought, “Wow, that’s really cool. There’s this successful Asian woman on TV and that’s my nickname.”

And so when I got to go to college, I just didn’t really have any expectations from myself. I didn’t know what I was supposed to be doing, I didn’t know what my parents expected of me. But after taking that class, I realized that I could do something with my life. So I moved up to the San Francisco Bay Area and finished school here. And when I was 26, I started a national nonprofit organization dedicated to addressing Asian American women’s health issues. Just thinking back to what happened to my sister, now it’s decades later and I feel like I’ve spent my whole life thinking about her. And that organization that I started, I mean, I didn’t know what I was doing. I was 26 and I’d only been in the country for 10 plus years. But I really wanted to do something about the stigma and discrimination and why a lot of Asian families don’t want to talk about mental illness. And as long as we don’t talk about it, and as long as there’s stigma, people aren’t going to ask for help like my sister.

It’s been a great journey and I wanted to document that in this book and also through my own political experience. My parents were always like, “Don’t ask money from strangers.” And what do you do as a politician? You have to call strangers for money and votes, you know? And so I had to overcome a lot of cultural barriers to run for office and win and serve. And I just wanted to offer something out there that says, you know, you can kind of do whatever you want. Because if I can do it, you really don’t have to be controlled by your background or your family history. So that’s, I think, the best way to introduce the book and myself. Is that it’s really for everyone. I often read books about very famous women leaders and they’re very inspiring, but I also feel like many women I have worked with aren’t going to get to that level. They’re not going to be Michelle Obama. And running for city council takes just as much courage as running for president, you know? And so this book is a collection of different journeys taken by women from all different backgrounds.

AA: Well, I very much felt that as I read the book too. There were so many things that were new to me in your particular experience, but I related very much all the way through. Like, “Oh, I felt that,” or even though that’s a slightly different variation, it was relatable enough that I thought, “Okay, well then maybe I could try this other thing, too.” So yes, that very much came through.

MCH: Really? You want to run for office, Amy?

AA: I do not want to run for office, no! Not that. Haha. But maybe one small thing or a couple of things in there like, okay, I could maybe do those things. So yeah, definitely some smaller increments. But one thing I want to maybe start with, as we dig into the book, is something that you just mentioned. And those are some specific gender norms in Korea and in your family of origin that shaped your gendered consciousness as you grew up. What were some of those factors?

MCH: Right. We were raised to be good girls, and I think that’s something that you could probably relate to as well. Especially us, we weren’t allowed to really voice our opinion or talk about any family or personal problems. And in fact, silence was viewed as a strength, you know, if you don’t say anything then that’s really good. And so we were raised to keep our thoughts to ourselves. We don’t really share our opinions, we’re just more of a supportive role. And my parents supported my brothers through college, they were expected to go to college and they paid for them to go to college, whereas they weren’t really doing that with the girls. We were more encouraged to be good girls and then become a mom, and that was really the expectation.

And when I think about my sister who passed, she couldn’t ask for help because you don’t ever talk about those things. You don’t shame the family by talking about any kind of struggles or problems that you’re dealing with. So it was a rough transition when we moved here, because I have friends who were the complete opposite of that. And I’m thinking, you know, “What? You can’t wear makeup when you’re a teenager!” I still don’t have my ears pierced because I was not allowed. So growing up in Orange County, I think I just wanted to fit in, I wanted to belong. But that was very challenging as well because I didn’t speak the language. So I perfected that invisibility, just being a good girl, being quiet, being under the radar, and just kind of keeping my thoughts to myself. And that’s what I did and I was really good at it. I was very much invisible for a long time.

AA: You include a quote in the book, and I think it’s Ernest Hemingway. And the quote is:

“You are so brave and quiet, I forget you are suffering.” That really, really hit home for me. Such a powerful quote. I think you used it in relation to your sister specifically, but I think that has broad relevance for people.

MCH: Yes, yes. I get asked a lot, “This is about women in politics. How come Mariel Hemmingway wrote the Forward?” She’s not in politics, but we worked together on a mental health ballot measure back in 2004. And she’s such a powerful person because she’s able to articulate, you know, all the suicides that happened in her family, but using that painful experience to help other people and lift them up. And so I really wanted her to write it because this book is about women and their journeys toward leadership. And yes, I’m in politics, and so we have a lot of focus on women in politics, but it’s really more than that. It’s about lifting women up.

And that quote, when I used it in the book, Mariel was like, “Oh, wow. Your book kind of summed it up.” And I was really thinking of my sister. Because we were taught to be good girls and to be quiet, and silence is seen as a sign of strength. It’s seen as something positive so what else was she supposed to do? And I often think about how, as a 12 year old, could I have helped her in any way? But it’s just so hard because I’m like, well, I’m trained not to say anything about any problem. And so I think when I read that quote it just reminded me of her. Because she was such a strong person, but at the same time, when you’re quiet and when you don’t have a voice, people can forget that they need help. So I really appreciate you pointing that out because even though it’s titled Women in Politics, it’s really about women and lifting women up. And we all have our collective journeys, individual journeys and collective journeys toward leadership and what we go through. And everyone that I interviewed brings this level of personal cause and passion to what they do. So that’s what that quote’s about, and I’m glad that you were able to relate to that as well. Thank you.

I perfected that invisibility, just being a good girl, being quiet, being under the radar, and just kind of keeping my thoughts to myself. And that’s what I did and I was really good at it. I was very much invisible for a long time.

AA: Yeah. One thing also that you write about, and that definitely resonates and tracks in my life experience too, is that a lot of people, but I think specifically more women say “don’t like politics” or they’re “not political.” Right?

MCH: Right.

AA: And so I just wanted to ask you, why are more women needed in politics? And then we’ll talk about some of the barriers that keep women out. But why are more women needed in politics?

MCH: Right. You know, I dedicate like six chapters to talking about very specific barriers, but in all of those chapters I talk about why women are needed and what they do and what the studies show. And it’s not just the interviews, but research that I’ve cited has shown that significant advancement in healthcare access, educational opportunities, and women’s rights correlate with more women serving in government. And one example that I give is late Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder. She had a part in the Family Leave Act, which is a groundbreaking federal law. She was an attorney and had kids, and she was the first woman to serve on the House Armed Services Committee. And she questioned why women weren’t allowed to fly in combat. And she literally single-handedly changed that for the whole country, allowing women to participate in that space. And so those are the specific examples of what women legislators do.

And multiple studies that I use talk about how women run for office to solve problems. It’s not that men don’t solve problems, but they’re raised to seek leadership positions. They’re encouraged to be ambitious. And women don’t really run for public office because they want to seek fame and fortune, that’s not who we are. We’re supposed to be good girls and build coalition and get along with everybody. And so we sort of bring that to this line of work as well. So more women serving in government has resulted in increased reproductive rights for women. Obviously a lot of women elected officials come out of school boards because we become active in PTA, then we run for school board, and then we run for higher office. And so education systems are better. Some of the larger studies on a global scale also show that getting more women elected actually helped bring clean water in India. I mean, there’s just all these specific examples. And so not having that 50 percent of the brain power and talent participate in our government is a big loss.

AA: Okay, so let’s dig into those barriers that keep women from participating. What are some of the major factors that the data shows?

MCH: Well, I always like to talk about three top cultural barriers and I give names to them. But I think a lot of people, not just in politics, but everyone who’s ever applied for a job would relate to this, and that’s the ambition gap, qualification gap, and likeability double standards. And those are the big themes that I talk about. There was a study that looked at the qualification gap for women, where more women were likely to assess themselves as not qualified for public office when men and women had identical qualifications. More men said, “I’m qualified to run.” Fewer women said “I’m qualified to run.” Well, men who said they were not qualified to run said they would run anyway, and that’s the ambition gap. So you see the qualification gap is that women don’t apply for jobs unless they hit every qualification mark on the job announcement. Like, “Oh, I don’t have that experience, I’m not going to apply.” Whereas men will apply if they meet 60 percent of the qualification list, like, “Oh, I can do this,” whereas women are like, “No, no, no, I’m not ready yet.”

And then that is a direct result of this ambition gap, which is that from when we were young, we’re not encouraged to seek leadership. My God, if I show any ambition I get penalized for that because I’m not supposed to be. And studies show that. Voters don’t really like women who are ambitious. And so the minute you announce you’re running for public office, the voters are already suspicious of you. Like, why is she doing this? Why isn’t she doing a nonprofit instead? You know? And so that gender bias is there and they’re very much related. Men would still run for office even if they’re not qualified, whereas women who are qualified wouldn’t run. So that’s some of the challenges that we deal with.

And then there’s also the likeability double standards. I mean, it’s not really our fault because there are institutional barriers, systemic discrimination against women no matter how hard I try. I told another woman who was county party chair at the time that I wanted to run for office and she discouraged me. So it’s not always like the women who are assessing themselves as less qualified, and there’s this likeability double standard where women not only have to prove that we’re qualified, but we also have to be liked. Meaning voters will vote for Donald Trump even if they don’t like him, but they will not vote for Hillary Clinton if they don’t like her, even though she is more qualified. And so that likability double standard is a real issue for many women, not just in politics, but I think even in the workplace. Women are often told they’re too aggressive, too ambitious, and men employees aren’t hardly told that.

And so I think we’ve got a lot of work to do within ourselves, but also just as a society I think we need to start thinking about that differently. Why do we need to be liked and qualified to succeed in politics or in the workplace when we don’t hold the same standard of men? So those are the three big things that I highlight in the book. And I think that from a young age, girls are taught to diminish their skills and their achievements whereas boys are taught to value those characteristics. And so what happens is that a lot of times people view men on their potential, not what their qualifications are, but what they could potentially do. Whereas women aren’t really given that leeway. And I think in politics that has contributed to women succeeding in that space.

AA: Another part of likability that you talk about in the book is the appearance double standard. In order to like a woman she has to look a certain way, and men aren’t held to that standard. Do you want to talk about that for a second?

MCH: Well, how many times do you hear people criticize Bernie Sanders’ clothes, right?

AA: Or his hair or his wrinkles.

MCH: Right. I mean, they can look like anything and people just sort of accept them. I don’t know if you recall, but right after Joe Biden won, his first State of the Union address it was just all about what Kamala Harris wore that night. And some of the bloggers were like, “Oh God, we need a fashion police and she’s wearing a UPS outfit” because she wore some brown suit and it blends in with the chair. I mean, seriously, that’s what we’re talking about. And this is a very accomplished vice president of the United States. And it’s not just men who engage in that kind of conversation, it’s also women. And so we have a long way to go. And I think when the press talks about women candidates in any way, whether it’s good or bad or neutral, her likability will decline. And that is just a fact. That’s based on a real study. And so when you start thinking about that, well, that’s not fair. We need less of that, we need less of style and more substance conversation. What does she bring? What are the issues? What’s the platform? And less about what she’s wearing, just like the way we give Bernie Sanders and all other male candidates and politicians the benefit of the doubt. And we don’t talk about what they’re wearing. We need to do the same with women.

AA: Yeah. And I like that you said that this is something women do to ourselves and each other also. So that’s something that for any women who are listening, to really notice. And even gently, I would say give the benefit of the doubt but call it out in a comment section or call it out in conversation among friends if women start to do that to other women. Just to steer it away and say, “Let’s talk about the substance.” Or, “Oh, would we be talking for this many minutes that I just clocked about what the guy is wearing?” If we wouldn’t, then let’s steer it in a better direction. So that’s something women can do too.

MCH: Exactly. And this is such a sensitive topic because I really like to talk about problems at more of a systemic level, institutional level, because I don’t want to put that burden on women themselves. But in my mentoring chapter, I decided to interview a man – so I’ve interviewed 17 women and one man in the book – and that man is my mentor, somebody who really helped me. And one of the things that was very prominent from all the interviews is that almost every woman that I’ve interviewed had a very strong man who was there for them and mentored them and helped them succeed. And it doesn’t mean that there aren’t women, but we need men to also participate in gender parity.

And framing it that way, like, we all want to educate men. But it’s also women sometimes who don’t support us and that does happen. My first boss, like at my real job that I had, not working for a nonprofit in San Francisco, the executive director was so inspiring and amazing until I wanted to start my own organization. She did everything she could to undermine my efforts. So it does happen. And I’m sure a lot of listeners can relate to that experience, and I don’t know if you have had that happen. A lot of feminists and women leaders did support me and I’m very grateful, but not all women are going to support you. I mean, that’s just a fact. My own former boss endorsed my opponent when I ran for assembly. So, it just happens.

when the press talks about women candidates in any way, whether it’s good or bad or neutral, her likability will decline

AA: Yeah, that’s true. And that’s good to keep in mind and to not take it personally or let it bog us down, but to just make sure that we’re supporting others and doing the best we can.

MCH: Exactly.

AA: One other topic that I want to have you talk about is the imagination barrier. And maybe I’ll share what came up for me when I read about this in your book. You write about, and you mentioned this a few minutes ago too, how young men are more likely than young women to be socialized by their parents to think about politics as a career path. And when I read that, Mary, I suddenly stopped and was like, Oh my gosh. I have a daughter who loves debate and ethics. She’s super, super bright and intelligent and digs into issues, really cares about social justice. She’s a senior in high school. Never, ever in her life did it ever occur to me to ask her if she was interested in politics. I’ve suggested like, “Oh, would you want to be a teacher? Maybe a college professor, get a PhD.” So I have high aspirations for her, but in terms of what field she would go into, she has all of these interests and passions and talents that would be great in politics but it never occurred to me.

So I went out from my room where I was reading the book and I was like, “Sophie, have you ever thought about politics before?” She’s like, “Oh yeah, totally.” I said, “I’ve never thought to ask you about that.” She’s like, “Yeah, you’re right. You haven’t.” Haha! And so anyway, it played out even for me and my own family and we had a really rich conversation about it. I was like, “You should start thinking about that, because we need people like you to be participating in leadership in the country. Would you ever consider that?” So, thank you for bringing that to my attention. As a mom I totally played into that gender stereotype and norm. So anyway, you label this the imagination barrier.

MCH: I so appreciate you sharing that personal story. I feel like my job is done! I love that, thank you. And all of us have experienced bias and sometimes we’re limited by our own imagination. And I have the same thing going on all the time. And even though I ran for office and went through that whole process and served in government, to this day I still ask myself, right before I speak in front of a group or whatever, I’m like, “Should I really say this? Is this worth saying something about? Can I disagree with them?” And so that good girl training really works because I still struggle with that even to this day.

But one of the women that I interviewed for the book, Amanda Hunter from Barbara Lee Family Foundation, they do some amazing research and she gave that name, “imagination barrier,” and I use her quote too in the book. But the foundation did this focus group and asked people to envision a governor, and most of them envisioned a white male. And I thought that was very powerful because as Jennifer Newsom said, you can’t be what you can’t see. It’s very powerful. And so I think that imagination barrier is really on an individual level, that is something that all of us need to be aware of. Sort of like that process you went through with your daughter, and it’s not like a magic moment thing where you are going to be able to catch that every time.

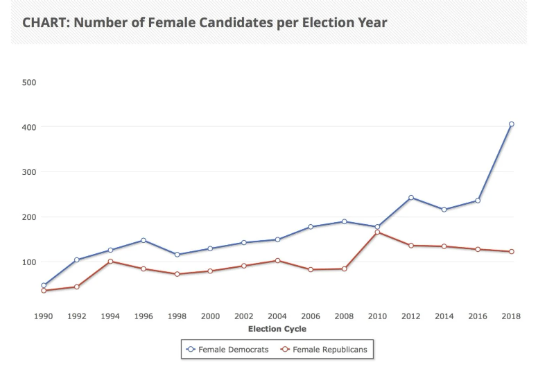

But if all of us are aware of it, I think we can start envisioning different leadership and different types of people who run for office. And every time somebody runs for office, even if you’re not successful, that really helps to break down the imagination barrier. I don’t know if you noticed that Hillary Clinton ran and she was the first woman nominee of a major party. After she lost, how many women announced they were running for president? Amy Klobuchar, Elizabeth Warren, a Senator out of New York. I mean, there were so many women, Nikki Haley on the other side. So then when the voters see Hillary, or people see a woman running, just them running for office makes it possible for voters to envision a different leader. Just incredible. And it doesn’t sound very complicated, but it is. It’s going to take a long time.

AA: Yeah, that’s really true though. That’s really powerful just having the visual image of like, “Oh, now I can imagine that kind of person in that role.” Where if you’ve never seen it, you can’t. Another thing that you talk about under the umbrella of the imagination barrier and a gender double standard is the motherhood imagination barrier and how we can certainly imagine men who have children having leadership positions, but not women who have children. Could you talk about that?

MCH: Well, yeah, because nobody asked men like, “Oh hey, how are your kids? Who’s taking care of your kids while you’re at this debate?” Nobody even thinks about that. But when I was writing the book, I pulled together a lot of research materials that existed. I found a New York Times article and I read it and I thought, “Oh, this is so great. I’m going to use it in my book. I’m going to reference it.” I printed it out and I looked at the date and it was 1972. And I thought to myself, wow, things haven’t changed much in some ways, because everything in this article I can relate to. And one of the women I interviewed, Cathleen Galgiani, when she ran for assembly, her male opponent said, “My opponent has no family values because she doesn’t have children.” So, voters are critical of women candidates. They’re very suspicious if you don’t have kids because they worry that women candidates won’t understand the issues concerning children or families.

But voters are also suspicious when women candidates have smaller children and they run for office. And they critique women politicians with young kids. In the book I quote Congresswoman Grace Meng, who took her small child to a weekend community event. And somebody said to her, “I didn’t vote for you so you could be a babysitter.” So voters will question women’s ability to balance the task of being a good mother with the requirements and the demand of being an elected official. And so if you have kids, they will scrutinize you. If you don’t have kids, then they think, “Oh gosh, she doesn’t get it.” And so it’s tough. So the chapter that I have in my book is called “The Politics of Motherhood” because so many women in the book are strong leaders because they have a family, they tend to be a caregiver, and they have some role in being a mom to somebody. So I try to see that as a strength, but at the same time, it’s like you can’t win in politics.

And I’m sure it’s very similar in the corporate world. I read a study that said that men start their own business because they want to be leaders and they want to be the president of their own company, whereas women start their own business so that they can be available to their family members and their kids and have flexibility. So they start their business because they want to serve others whereas men tend to start their own business because they want to be their own boss. It’s a very complex one to this day. And you would think, you know, from the time that Barbara Boxer first ran for office, she often talks about how at the Sierra Club interview this older lady asked her, “If you’re here, who’s making dinner for your kids?” Somebody asked that, and this was decades ago, but in some ways we really haven’t… I mean, we’ve accepted women with kids to run for office, but it’s still kind of a work in progress. You have to explain yourself. So if Amy wanted to run for office, you would have to explain your kids’ situation. And get this, the voters tend to be more understanding if your kids are older, so they’re like, “Okay, she doesn’t have to balance the responsibilities, she’s going to be able to dedicate herself to the job.” Whereas a man, you don’t have that going on and they’re not that interested in his family and kids responsibilities.

If you read the first chapter, Lauren Book, the Senate Florida minority leader superstar in her mid thirties, who I think is going to be the governor of Florida someday, I hope, somebody recruited her to run for the leadership position within her caucus. And her male opponents said to her, “You just had a baby. You have twins, you have little babies. How are you going to do this?” And when she heard that, she decided to run for the position because she was like, “I’m going to prove it to you. I’m going to show you how it’s done.” And she won. And this is still happening today. And so while we have accepted different variations of women candidates and politicians, we still have ways to go, I think.

AA: Yeah, for sure. And I think, maybe it’s obvious, but I think we still have it so baked into our culture that when we see a man who has a family, we don’t need to ask who’s making dinner for the kids because we assume his wife, their mother, is making dinner for the kids. And like you said, it’s changing so that women can do both, but the piece that needs to change, to catch up, is that then that woman’s partner does need to step in more because somebody does need to make dinner for those kids. Somebody does need to be reading them a bedtime story or whatever, and people want to make sure that children are taken care of, but we just assume that that’s the woman’s job. And so the other piece is now that women are working more, that means that fathers get the joy and the privilege and the burden sometimes, but get that experience of being the parent for their kids too. We don’t just assume that it’s always going to be the woman. I mean, I guess that goes without saying, but it’s not changing fast enough to keep up.

MCH: Yeah. And I don’t know if you followed Sarah Palin when she was a vice presidential candidate. Her husband was mocked and shamed and people were really mean to him, you know, because he was a family man taking care of the kids while the wife was out there campaigning. And they had the reverse roles. And I think that’s, again, like the imagination barrier. Like, what’s wrong with that? But people had a hard time with that. And now, when you look at Kamala Harris, her husband seems to be really enjoying the job and he’s just so happy as a white male to support his spouse, who’s a woman of color. And I think that is so important when we talk about the imagination barrier, because it’s the same for men too. They can’t be what they can’t see. And I think it’s important to see that we have a second gentleman who just loves that job of supporting the powerful women of color spouse, you know? And so, I do feel that we are making progress. It’s slow, but it’s happening. We’re kind of in this transition time, like, okay, now we’re going to have a female president and that’s a concept that people can embrace now. And in California we still haven’t had a female governor. Can you believe that?

AA: Wow, you’re right! That’s crazy.

MCH: Yeah. And everybody thinks California is super progressive and all of that, but we still haven’t had a female governor. And when I got elected, I think there were 28 women out of 120 in the state legislature.

AA: Wow.

MCH: So we’re getting there, but we still have a long way to go, I think.

AA: Yeah, for sure. The next thing that I wanted to ask you about is the fundraising gap. And this was so, so interesting to me to see the numbers and how that works. And I do have to say, like you said at the beginning of the episode, I think it is way more uncomfortable for women to ask people for money and to be seen as seeking that power or wanting money and being self-promoting. There are a lot of cultural barriers that make that really uncomfortable for women. But if you can talk about fundraising, that would be great.

MCH: Yes. I was raised never to ask for money from anybody under any circumstance. And in my first real job interview I had in San Francisco, I didn’t even ask how much the position paid because, you know, you don’t make eye contact and you just accept whatever they give you. I mean, that was kind of how I was raised. So I was very uncomfortable. And the HR person’s like, “Do you want to know what it pays?” And I was like, “Okay, thank you.” And then you just leave it at that and you move on. You don’t want to be ungrateful, you’re just grateful for everything. I mean, that’s kind of how Asian culture is. And you are nodding your head, like you relate to some of the things that I’m talking about.

And so women look at politics and think, “Would I be able to have the money?” And so in the past wealthy people have entered politics and they would bring their own resources and that’s fine. But what I wanted to point out was that the greatest amount of money doesn’t always guarantee that you win. When I was campaigning for my assembly race I had raised like 10 million for my nonprofit, but that’s different because that’s for a cause, that’s for public good. It was a really difficult transition because I was going from somebody who didn’t even ask how much the job pays to making cold calls to mostly male leaders and asking for money. Oh my God, it was interesting. But I really had to do it and I got good at it eventually, but the point that I want to make is that if somebody like me can do it, so can you, honestly. Because you find out that so many good people want to contribute and want to help you. And so you just have to do it, and you just have to get over that.

And Jean Fuller, she was the Senate Republican leader in California who had never thought about running, she was a school superintendent. And her mentor, a congressman, called her and said, “You should run for the assembly.” And she’s like, “How do I do this?” And one day she received a box of papers with names of people and their phone numbers. And he said, “Just call these people.” And so she’s like, “What do I say?” So it took her a while to figure out her script, and she organized the list on her ironing board and started making those calls and she said she had nobody who told her “This is what you do,” you know, she just kind of had to figure it out. And she’s said she was really lost but she ended up becoming California Senate Republican leader.

And so, I try to show those examples in the book to say to people that seriously, if you want to do it, you could do it because I did it. But money and fundraising is a big deal. Women are just as competitive but our contributions tend to be smaller, unfortunately. People write bigger checks to men because they think that men have better chances of winning. There’s like a viability issue and stereotyping women as a weaker candidate, like, can she win? You get that comment a lot. But there are so many examples that I cite in my book where women are competitive. They raise smaller dollars, but they’re good fundraisers and they sometimes get outspent a lot by their opponent, but they still win. I mean, look at AOC. Alexandria raised I think virtually nothing. And she unseated an incumbent with the right messaging. And Karen Bass, I worked on her campaign, and her opponent put in a hundred million dollars of his own money. He just wrote a check to his campaign committee because he’s like a billionaire. And we went out and raised like 20 dollars, a hundred dollars, those checks, and raised 8 million. Which is a lot, but not against a hundred million. But she won comfortably. So there are just so many inspiring examples of how you can overcome those barriers. So it can be done. It shouldn’t be something that your daughter should be afraid to do. And if you’re really good with social media, although I talk a lot about the dark side of social media, it allows women to be competitive. You can use those platforms without spending a lot of money and reach a lot of people, and that is really a positive thing for women.

AA: Yeah. One takeaway for me, something that I remembered from this section, is that like you said, women raise smaller dollar amounts. Am I remembering correctly that they get roughly the same number of donors? So they’ll get the same number of people contributing, but each contribution is bigger for a man and smaller for a woman. I thought that was really interesting. So women basically have to do many times the number of the phone calls or they have to recruit more in order to compete dollar for dollar. That was really interesting to me. And yeah, I just love those examples of even your own example of just being nervous and not knowing what to say and feeling like, “Oh, I hate this. I hate this. I hate this.” And just for anybody who’s listening, thinking if that’s what’s stopping you is just not feeling qualified or I hate making cold calls, or I hate asking for money. Just hearing that that’s how everybody feels. You just have to toughen up and get over it. What did you do when you were sitting there on the phone with butterflies in your stomach feeling sick, and then you hang up, maybe you didn’t do a good job and you feel stupid. How do you psych yourself up to do the next one?

MCH: Well, you just got to move on to the next one.

AA: Okay, I love it. Just do it.

MCH: Yeah. I love to beat myself up every minute, and I think all of us have a little bit of that, right? We’re our own critics. And I’ve had very harsh conversations with my own performance, but I started the campaign with like Tipper Gore’s endorsement and had some pretty high-power women backers. I went to the local party chair and I said, “I want to run for this. I raised all this money from my family and friends, and I’m ready.” And she said, “No, you’re not because you don’t have any experience running a campaign.” And so I think you need to understand that yes, no matter how much you raise or how well you do or how pumped up you feel, there’s always going to be that other opinion that reminds you that they’re going to be critical of you no matter what. And so I couldn’t even impress my own party chair with a Tipper Gore endorsement. And I think I had a lot of congressional support too, because I’ve done so much work in Washington DC, including Nancy Pelosi, who was backing me. And nobody was impressed. They’re like, “No, you’re not ready.”

People write bigger checks to men because they think that men have better chances of winning.

So, yes, I think being your own cheerleader, understanding that you are going to make mistakes and it’s not going to be perfect, but you just have to keep going. And one of the interviews that I love, and I usually end my interviews with this quote from Laphonza Butler, who was president of the EMILY’s List and now she’s in the US Senate. She’s one of our California senators. She said to me, because I asked her, I was like, “Do you have any advice for people?” She was in a very powerful position to help candidates raise a lot of money. And she said, “Do it anyway! Okay, so maybe you’re not 100 percent qualified, maybe you’re not 100 percent ready, but do it anyway.” And I just love that because when I was 26 years old and started that nonprofit organization, I had a lot of support and I’m very grateful for that, but I had no idea what I was doing. I was just a kid, but I did it anyway. And it was hugely successful. It doesn’t mean everything you take on will be a success, of course not. I have failed just as many times as I’ve succeeded, but I did it anyway.

And I was so glad I did because I was able to make a difference for people and it was amazing. We raised 10 million for a nonprofit organization that nobody’s ever heard of or thought of. You know, Asian American women? I mean, it wasn’t really on everybody’s high list of priorities. Same thing with the assembly. I wanted to do it, I thought I had some good role models, I was very inspired. I thought, “I’m going to go to the state legislature and really shake things up and do some stuff around mental health.” That was my passion. And people discouraged me, they didn’t endorse me, they told me not to do it. The fundraising was difficult, I have my own personal cultural challenges, but I did it anyway and I won.

And so I just love Laphonza’s quote because often as women we don’t think about what we bring to the table. Okay, I was 26 years old, but certainly I had skills and I had things that I could do. And people will remind you of what you don’t have and what you don’t bring to the table. What I’m asking you is to think about what you do bring and what you can do. And I think I live that advice that she gives to other women. I think I’ve taken chances and I did it anyway and had an enormous amount of success. And I think that if I can do it, my goodness, just about anybody could. And that’s the purpose of the book, is to show that the United States senator who was born and raised in Mississippi, lived on public assistance, raised by a single mom with multiple jobs, somebody like her isn’t supposed to be a United States senator, but she is. And through these examples of women, I think anybody who wants to pursue politics can.

AA: Well that’s a powerful and beautiful way to wrap up the episode. Mary Chung Hayashi, thank you so much for being here today. Again, I learned so much from your book, I’m so glad I read it. Again, the title is Women in Politics: Breaking Down the Barriers to Achieve True Representation. Thank you for your book, and thanks so much for your time today.

MCH: Thank you, Amy. I loved this. I want to come back.

AA: Please, please do, I’ll make it happen!

MCH: Thank you.

we’re going to have a female president…

that’s a concept that people can embrace now

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!