“Finding equity in as many ways as we possibly can.“

Amy is joined by advocate and influencer Paige Connell (@sheisapaigeturner) to discuss the slew of household work which women still disproportionally manage for our families, the mental load of motherhood, plus ways we can change the culture and make this invisible labor visible.

Our Guest

Paige Connell

Paige Connell (@sheisapaigeturner) a working mom of four, shares her insights about motherhood and careers, the mental load, and relationships. She’s a fierce advocate for affordable childcare and paid leave, she’s been featured in Scary Mommy, The Today Show, and more.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: What comes to your mind when you think of the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s? Maybe black-and-white photos of women’s marches led by Gloria Steinem, a battle to pass the Equal Rights Amendment. For me, what comes to mind is the backlash to the 1950s cult of domesticity, where so many women were kept financially dependent and infantilized by prohibiting them from working outside the home. The Women’s Liberation Movement promised women better lives through participation in the workforce and earning their own wages. And work they did! Droves of women began careers. Katharine Graham became the CEO of The Washington Post in 1972, the first woman to lead a Fortune 500 company. And then The Mary Tyler Moore Show portrayed a young working woman as its protagonist. And indeed, working outside the home did bring women more financial security, more independence, and more personal growth. But, soon women began to notice something. Once they got married, and for this conversation we’re going to talk about women married to men, and especially once women had children, they were exhausted, bone tired, and somehow not feeling all that liberated in their real daily lives.

Sociologist Arlie Hochschild decided to figure out what was going on, and she conducted research in the ‘70s and ‘80s that resulted in the classic text The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home, which was published in 1989. She identified that all across society, regardless of race or class or culture, women who worked outside the home came home to a whole other work shift, taking care of the house and the children nearly single-handedly while their husbands spent the evening hours in leisure. Only women were working the second shift, and it wasn’t fair. As I’m sure you’ve heard or possibly experienced in your own life, this problem has not been solved between 1989 and now, and in fact, it’s still a huge issue. One person that I turn to for information on this issue is Paige Connell, who runs an Instagram account called @sheisapaigeturner, where she seeks to make invisible labor visible. I’m so excited to welcome Paige to the podcast today. Welcome, Paige!

Paige Connell: Hi, thanks for having me!

AA: I’m so excited to talk to you today. I’d love you to first introduce yourself. Tell us where you’re from, what makes you you, and what has brought you to do this work that you do today.

PC: Sure. So I am from Massachusetts and I am a mom of four kids and I am married. I was working full time, and I came to this work just through personal experience. I was living what so many other women live, which is doing that second shift, taking on the invisible labor of the home and the child care, and I reached a breaking point pretty quickly. And transparently, I think I reached it faster than I would have if we had not had a global pandemic. I think that really sped up the process for me, but I have never been one to sit by quietly. And when I started experiencing this, I just couldn’t stop talking about it because, to your point, it felt so incredibly unfair. And through talking about it, I’ve also been able to learn about it and learn about all these systemic issues that really play into this issue. And that’s really what brought me to creating my social media channels and talking about what I talk about, which is not just invisible labor, but it’s all the things tied to it and the systemic influences that impact our lives as specifically from my experience, mothers and wives and employees and everything else that comes from that.

Learning about it just taught me that so much of what I was personally experiencing was not an individual failure, but was the reflection of a system and society that really places women and men in particular in very specific boxes and really limits our abilities, right? It really limited my ability as a wife and mother to have a life outside of those things, to thrive in my career, to have a social life, to have hobbies or leisure or any of those things. Because not only was there societal pressure for me as a mother to be exceptional, there was not a lot of support for me either. Lack of childcare, lack of paid leave, lack of a partner who understood the mental load of invisible labor. So, once I started talking about these things and learning about them, I found that I felt less isolated in them. I realized it wasn’t my fault, right? This is actually not my fault. This is not something my husband and I did wrong. This is the result of growing up in this society, in this structure. And unfortunately, in order to change that, so much has to change, which is why I think so many people are talking about it right now.

AA: Mm-hm. For sure. That’s a perfect bridge into the next topic, which is what has to change? What are some issues that you see popping up for people that you are learning about and talking about a lot?

PC: Sure. I think there are so many things, but they’re all very intertwined. I think we can start way back when we’re children. How are we conditioned to show up in the world? How are women conditioned versus men? What’s expected of us? I even think of this: when I was little I had a younger brother, three years younger than me, there were four of us, and he was the youngest. And people used to call me Mommy Paige. “Oh, you’re gonna be such a great mommy. You do such a good job taking care of your brother.” And I listened to that, and I was like, “Oh, it’s good to be a mom, and it’s important to be a mom, and these things are things that I should strive for,” right? I took babysitting lessons and I was encouraged to babysit, and then I worked at a daycare in high school, I took child development courses, and I didn’t think twice about it. My boyfriend, who’s now my husband, was definitely not taking child development courses, thinking about babysitting, or being told what it would look like to be a good father. So there’s that part of it, which is how we speak to boys and girls and young women and young men about what it looks like to be a person in the world, how we contribute, how we bring value to our families and our homes and our world, really.

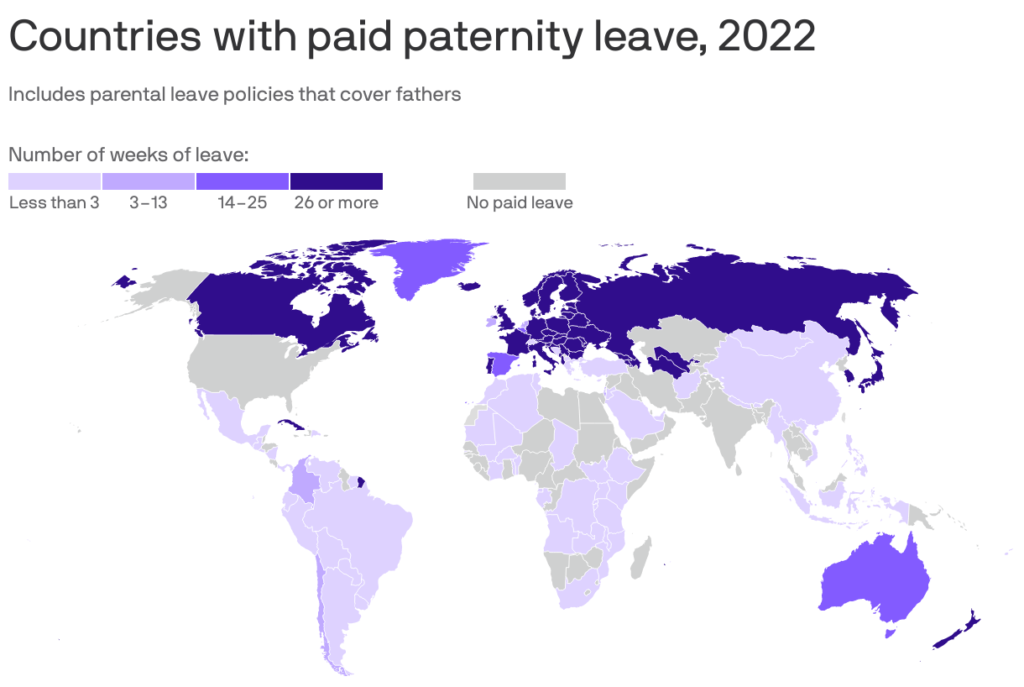

So there’s that, that really needs to change, like a huge societal shift and gender norms, but there are also actual structures and systems that need to change. We have very little paid leave available to families, and I say families because it’s not just parents, it’s caring for your aging loved ones, it’s caring for your sick partner, right? We have very little in the way of paid leave and support there, but also parental leave. And even when we have parental leave, men don’t always take it, right? So there’s that, there’s the lack of affordable, safe childcare that you can actually access. That is a huge issue. And then I think about things like how the inequities that exist in our homes with domestic labor, invisible labor, that second shift play into the inequities that also exist in our workplaces and every other aspect of our lives and our health, right? Women’s health suffers because of the second shift and the expectations placed on them. So all of these things are so tied together, you really can’t have one in a silo and expect it to really change the overall dynamics of how we operate as a society and as parents and partners. But I think these are the things that would make massive, massive differences in the lives of everyday people.

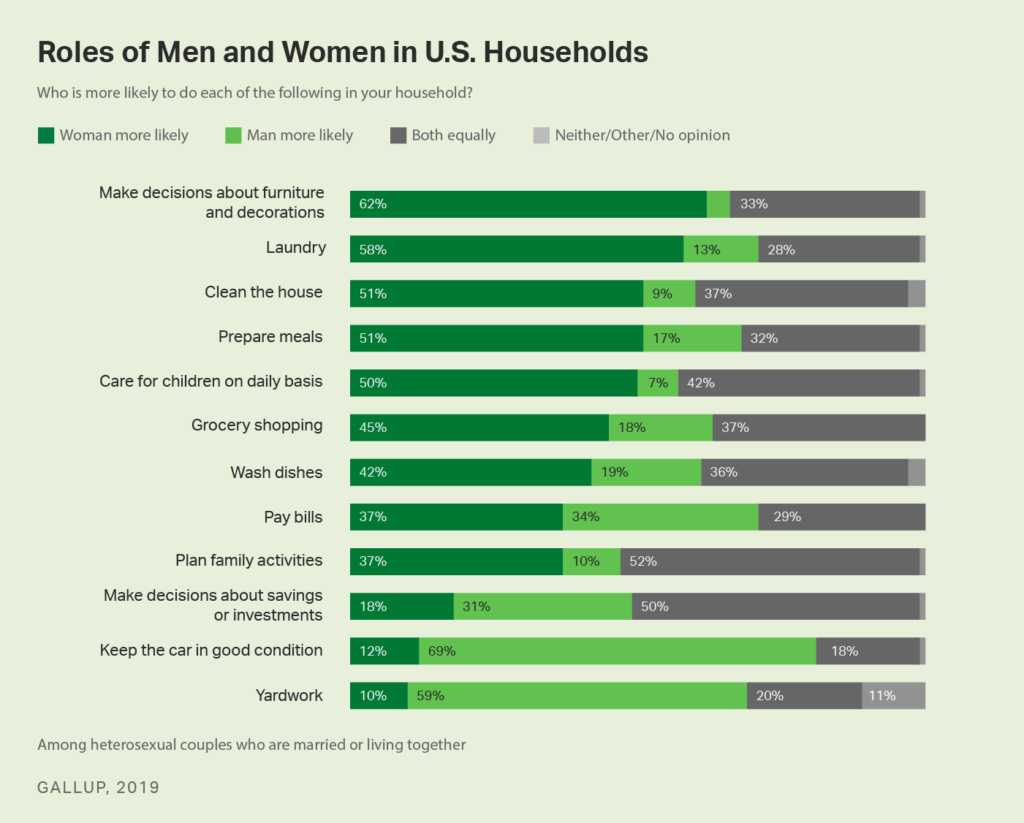

AA: One thing that you talk about a lot on your Instagram is you identify all these different aspects of the work that women do. And I love your videos. You’ll just be talking and explaining issues while you show yourself packing your kids’ lunches and starting the washer and taking a work meeting and driving a carpool and filling out paperwork, all that stuff. That does tend to be, or historically has been invisible and seen as women’s work. Can you talk about some of those individual things that come up in families that are categorized that way as invisible and women’s jobs?

PC: Sure. When I think about them, I think the laundry is always a really interesting one to talk about because people have a lot of feelings whenever I talk about the laundry. Oftentimes women do the laundry, right? I don’t do my husband’s laundry, and I’ve talked about that. And people are like, “That’s crazy. She clearly doesn’t love him.” And I’m like, “What does laundry have to do with love?” We do eight to ten loads of laundry a week and I don’t do one of those loads of laundry. That’s not about love, that’s just about work, right? Laundry is work. And one of the reasons I show this work is because people say, “How hard is the laundry?” It’s like, okay, no, one load of laundry is not hard. Eight loads of laundry is hard. And when you do the laundry, it’s not just swapping it, putting it in, folding it, putting it away. It’s also, “Oh, actually this pair of pants my kid has grown out of. So I’m going to pull this pair of pants out of the laundry, I’m going to put them in the donation bin or the hand-me-down bin, and now I have to get her new pants because now she doesn’t have pants because I just took those pants.”

So it’s this idea that it’s not just folding one load of laundry, it’s the neverending to-do list of the laundry and the cooking and the cleaning, and those tasks specifically often fall to women. It’s these repetitive tasks that always need to get done daily and often multiply with children. People will say, “Well, do you mow the lawn?” No, but the lawn is the lawn. And if you have four kids, your lawn doesn’t grow faster. But there is more laundry with four kids, right? So things have to shift in that scenario. Before you had kids maybe it was fine that your wife did all the laundry and you mowed the lawn, but now there are kids and there’s more laundry and there’s more work. And the expectation these days is that women not only provide financially for the family, because 70 plus percent of women do, but they’re also still doing a disproportionate amount of this work. So I like to show those things that do add up, the making of the lunches, the folding of the laundry, the unloading of the dishwasher, because they’re never done. It’s just never done. That work is always happening.

AA: And it also interrupts anything else you’re doing, and that’s another thing that even Virginia Woolf was talking about in the ‘20s and ‘30s. To sustain the mental exertion that you need to do creative work, to do intellectual work, that’s why she said you need a room of your own and you need uninterrupted time. And all of those things just chop your day and chop your attention into little bits and it really does, I think, keep women, historically, from reaching their potential in other areas because it’s always interrupted. It’s constant all day long.

PC: Yeah, and I also think that if you zoom out, like when we say everything is connected, if you think about workplaces, I got this feedback a lot. I’d be interested if you did, but I know a lot of my girlfriends have too, which is, “You’re just not a high-level thinker. You’re really good, and you get everything done, you check off the boxes, you never miss a deadline, you’re on it, but you don’t zoom out. You don’t think big picture. You don’t strategize enough. We need you to be more strategy, less doing.” And I think it’s so interesting, right? Because women often don’t have that same time, space, and luxury to zoom out. Because even in the context of work, who gets to go to happy hour after work and go play nine holes of golf midday? Men. But women are expected to, on their lunch break, take the call with the school or to run to a kid’s doctor’s appointment, pick up dry cleaning. They are having to do all these things whereas men also have this space, this time to zoom out, to be creative, to network. Even networking in the context of work. Networking requires a lot of time and effort. Who has that time when you also have this whole second shift of work to do when you get home? It’s impossible!

AA: Another one in this topic, people who are watching this on YouTube will see that you have a Christmas tree in the background. We’re recording this in the weeks coming up until Christmas, so I want to talk about the holidays because that’s a big one, too. Can you talk about that?

PC: Gosh, we think about the holidays as a day, I think, right? There’s the holiday season, and then there’s the day. I think a lot of times there’s this messaging to women in particular, which is like, “Don’t make such a big deal of this. The holidays don’t have to be a big deal. You make them out to be more than they are.” But I jokingly say that the holiday season starts in October because that’s Halloween, right? And we’ve got costumes and trunk or treats and school volunteering and donating to the school party. And then immediately after that, we’re rushing into November and it’s Thanksgiving and all those things. And if you’re anything like my town, they basically had no school in November. And then in December it’s holiday parties and the book fair and all these things, right? It’s all this stuff happening around the idea of the holidays. But oftentimes there’s this ongoing joke that women are overspending at the holidays, they’re over decorating, they’re doing all these things. And what we fail to recognize in these conversations, oftentimes, is the value of this work and how hard it is to navigate and how much goes into it.

the making of the lunches, the folding of the laundry, the unloading of the dishwasher…It’s just never done. That work is always happening.

Even if you pare back your holidays completely and all you’re doing is gift giving, gift giving is a ton of work. Thinking about what your kids want, knowing what they need, budgeting, scouring the internet for the best deals, checking to see if things shipped and actually arrived. Like, there’s a gift right now that’s lost somewhere, but I’m tracking that, right? I know that. And I know that it’s lost, and I know that it hasn’t arrived. And we even had one gift that was cancelled, and I never got the cancelled email. And I’m calling all the department stores nearby, like, “We need this special LEGO set!” My son will be devastated, right? And it’s sold out at LEGO.com and I’m scouring the internet. That is the work that is so often happening behind the scenes. And to the general public it’s like, “Look at all these women. They have thousands of packages, they’re spending so much money.” And nobody ever stops to think, “Well, how much work goes into all of these things and how do men benefit from this work?” They get to wake up on Christmas morning and their kids have presents to open and joy on their faces and memories that they will have well into adulthood. Their parents even have gifts that they didn’t buy, but their wife did. It’s all this work that does have value.

And it’s not that it has to happen, right? We could pare back our holidays and there’s no real harm. But if you often ask the people who make light of these things, “What do you remember about the holidays from when you were a kid?” “Oh, my mom, she always did this really fun X, Y, and Z,” or, “My mom always gave us this personalized Christmas ornament,” or, “I loved spending the holidays with my cousins.” Okay, well, somebody made that happen for you. Chances are it was your mom, right? Chances are it was your mom. And you look back on that fondly. And that is what we’re trying to do for our children and for our families. The holidays have so much work that goes into them, whether it’s Christmas cards or prepping and cooking and cleaning and all the things, and it adds up to a ton of work, which again, often falls to wives and mothers to do, or sisters, just women in general.

AA: Yep, for sure. And I’m glad you brought up that emotional component, too. Because yes, there’s the economic thing and you can pare back and you can even skip some of the parties and skip some of the events.

PC: Of course.

AA: Sure, we can. But those events too, it’s the emotional things that if you choose to have children and you love your children, you don’t want your first grader scanning the crowd at the Christmas concert and a parent isn’t there to support them, because we’ve all been that kid. And then the other thing, I learned the term “kinkeeper” just this last year, that women tend to be the kinkeepers. And a lot of things around holidays, whether it’s Christmas or Hanukkah or whatever holiday, are family traditions that get passed on, making sure you’re telling the stories or the songs. Bringing the ancestors into the family to make sure they’re connecting to your kids. That’s also beautiful, important human work that tends to be invisible and tends to be women’s work. And it is meaningful, and you’re not going to drop that stuff, right?

PC: No. And I was jokingly talking about all the gifts you have to buy, right? You got the nieces and the nephews and the teachers and the bus driver and somebody’s like, “Who was buying gifts for teachers?” And I’m like, “I am!” Because teachers are underpaid. They are underpaid and they’re doing incredibly hard work. And again, that’s a women-dominated industry. I’m buying them a $50 gift card to Target or wherever. I’m doing that because it is valuable and it is important. And oftentimes people will say this is consumerism, right? “Ugh, consumerism, the holidays.” Actually though, giving gifts to a teacher, to a person like a teacher, has value. It has impact. It says, “I recognize your work and the importance you play in my child’s life, and this is a token of thanks.” I think we can all agree that those things are important. And when people have done those things for us we go, “Wow, that was so nice. That was so thoughtful. I so appreciate that.” So we joke, people are like, “Who’s doing that?” And it’s like, well, I am because I believe that it has value and because I believe that it’s important. And if I’m capable of doing it, not everybody’s privileged enough to be able to give to all the teachers and I totally understand that. Economically, it’s difficult. But even when you can’t afford to give a gift, to write them a really nice thank-you note, that is still work. That is still mental labor. That is still emotional labor. That is still somebody thinking about that.

Oftentimes these things get so tied, specifically with the holidays, to consumerism and overconsumption, when even if we scale it back to a simple handwritten note, somebody still had to think about that and do that work and remember it, add it to their mental to-do list of things to do at the holidays. So I just think it’s important to try and separate those two parts of it, because yes, there’s overconsumption and all those things. Yes, for sure. But the actual work of gifting and showing thanks and your gratitude at the holidays, that’s still really, really important for so many reasons. As are traditions, right? Those are so special for many, many reasons and they have so much value.

AA: Yeah, for sure. I want to ask a question that is still a foundational question and you mentioned it earlier in the conversation, and that is where the expectations come from. Because for me that messaging of, you know, men work outside the home and women in the home, that’s because I grew up in the LDS context. I grew up very, very devoutly Mormon, and Mormon culture is a couple decades behind the rest of the world. So I didn’t work outside the home when my kids were growing up. And if you know any Mormons, it might surprise you to learn that a lot of LDS people have framed documents on their walls that designate that men provide and preside and women are responsible for nurture. So we have this whole narrative around women being innately more nurturing. Women are innately, by divine design, supposed to be the one to do all of the homework, the housework and the care work. So it kind of surprises me sometimes when I talk to other people or learning all of this and reading The Second Shift, I’m like, “Oh, it’s not just us.” It’s not just very conservative religious families that grow up with these expectations. So I’m curious to ask you where that came from for you or for your friends. Is this based in religion or other social customs?

PC: You know, I also think it’s not just religion. It’s also where you live, like geographically in our country. So I grew up in the Northeast, which is known for being a highly educated area of our country where most homes are dual income homes. And my grandparents, both people always worked. My grandmother, my grandfather, my parents, they both always worked. They both went to college, they both provided, they both traveled for work. My mom traveled just as much as my dad did for work. So I grew up in a home where it was like, “Yeah, of course I’m going to have a job like that.” I would never be a “homemaker.” That wasn’t even something I ever once considered. Never. Not once. And none of my friends’ moms stayed home. That was such a foreign concept to me, like a stay-at-home mom. I’m like, “Who has that? That’s made up for TV. That’s not real.” And I think that’s interesting because I was raised Catholic. Irish, Italian, you know, Massachusetts girl, raised Catholic, but that wasn’t the messaging I got. I did not get the messaging that it was my absolute goal to become a mother and to care for my husband. If anything, my mom was like, “You will always have your own income. Never depend on a man. Don’t even think about it.” I had the complete opposite messaging and I still ended up in a marriage where these gender roles existed.

AA: That’s crazy! It blows my mind. Why? Where’d it come from?

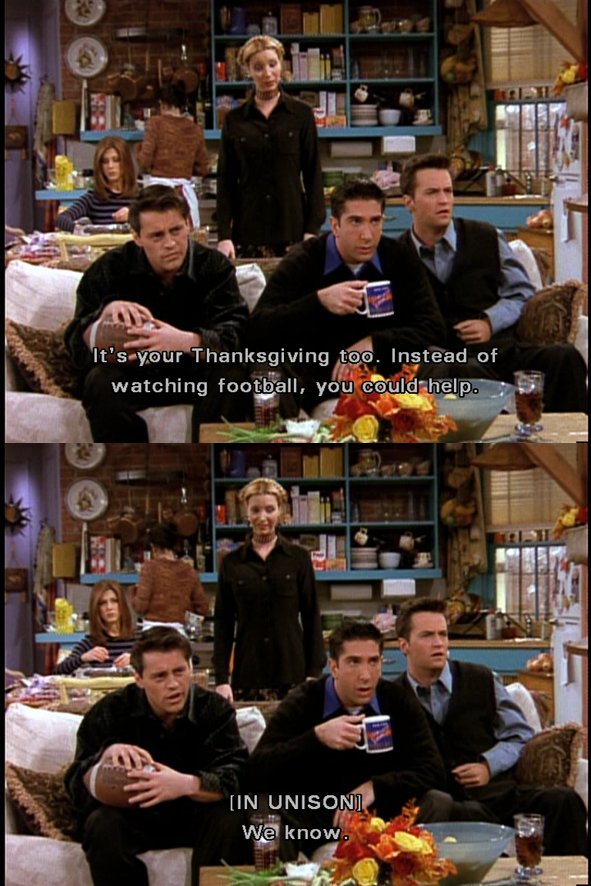

PC: My husband did “a lot,” right? He was very present, very hands on, very active with our children. But he was not doing nearly as much as I was doing. I still took on the bulk of that work, and maybe not the physical tasks, but the mental labor, the emotional labor, all of that was really mine. And I honestly think a lot of this conditioning comes from society at large, like the messaging we get from TV shows, the way that we’re spoken to even as young girls and women. The fact that people asked me if I wanted to be a mom in my 20s. Like, “Oh, when do you want to have kids?” Nobody was asking my husband when he wanted to have kids. That’s not even something they’re asking him and they’re not giving him advice about when to do it or what kind of childcare, nobody’s saying any of those things to him. So the burden fell to me, but I don’t even know that it was solely societal conditioning. I think there was a lot of pressure, and we live in the age of information overload, especially for women. It’s like, “Here’s another toddler expert. Here’s another sleep expert. Here’s another feeding expert.” And it’s all targeted towards women on the apps. If you open my husband’s phone it’s like golf videos, woodworking videos, I’m like, “What the heck is this? Why is your algorithm this and my algorithm is like ‘10 ways to feed your picky toddler.’ Why is that my feed?” So I think there’s that. There’s all this pressure.

But as I became an adult, I also realized that the system wasn’t set up for women to have it any other way. We are the ones with, if you have it, “maternity leave,” paid or unpaid, and it’s expected that we take it. And by doing so, we tend to take on that work very early on caring for the children. And then even if we go back to work, at that point, you go, “Hey, I’m back at work now. We can split these overnights.” Well, I don’t know why I’m doing them by myself, which never should be the case anyways. But like, “Why am I doing these by myself? We’re both at work.” And then the husband goes, “Well, the baby doesn’t want me in the middle of the night. They want you.” And it’s like, “Well, of course they want me. I’ve been with them for three months and you haven’t been.” It’s a no-brainer, right? So there’s that societal conditioning and those expectations placed on us by what we see in TV and magazines and the way people speak to us. And then there’s also the systems that we operate in, which is, it’s assumed that we should compare a mother’s salary to the cost of childcare. Everybody says, “Does your salary cover child care?” And it’s like, what do you mean my salary? Do you ask that about a mortgage? No, you ask about both of our salaries. Why are we talking about childcare as if it’s only my responsibility? And so I think it’s all of these systems intertwined. And so for me it had nothing to do with religion or the way that my parents raised me, it had everything to do with all these outside messages and pressure, and then the actual systems that we exist within that make it incredibly difficult for it to really be any other way for women without a lot of breaking down of these gender norms with our partners. And it’s hard to do that work in your home, too, when things like childcare and paid leave don’t always exist or aren’t accessible.

AA: That’s so interesting, Paige. Because like I said, growing up Mormon does show how things were a couple of decades ago, so you can see the historical through line really clearly. But it’s so interesting that different communities, and like you said, geographically, first there were laws that prohibited women from working or owning their own money. And then we changed the laws and then gradually the culture changed in little bits and pieces differently for different people. But you can see the vestiges of all those old systems because they exist in our own minds and our own customs in our own families. It’s hard to identify them and change things, even once the laws change. It can take hundreds of years to change culture, which is why we’re doing what we’re doing, right?

the system wasn’t set up for women to have it any other way

PC: Yeah, exactly. And I think everything is colored by our own personal experiences, right? I’m talking to you as a privileged white woman who grew up in a middle class family, whereas my mom would tell you a very different story about her life. She grew up sharing a bed with her sisters, living in the inner city, a very different experience to me. And yet somehow we still ended up in a very similar position because, to your point, change takes a really long time. And I think we’ve all heard that from a woman older than us. “Oh, I get it, I’ve been there. That’s just the way it is.” And it’s like, I don’t know though. I don’t know that it has to be like this. And I think we have the privilege of living in a time where we can shout from the rooftops on social media or wherever and say, “Actually, I’m not doing it.”

AA: It doesn’t have to be this way.

PC: Yeah, exactly.

AA: No, it doesn’t. Okay, this is going to seem like an obvious question, but I want to just unpack a little bit this unfair work balance, the second shift that is still falling disproportionately to women. How does that affect women, how does it affect men, and how does it affect children?

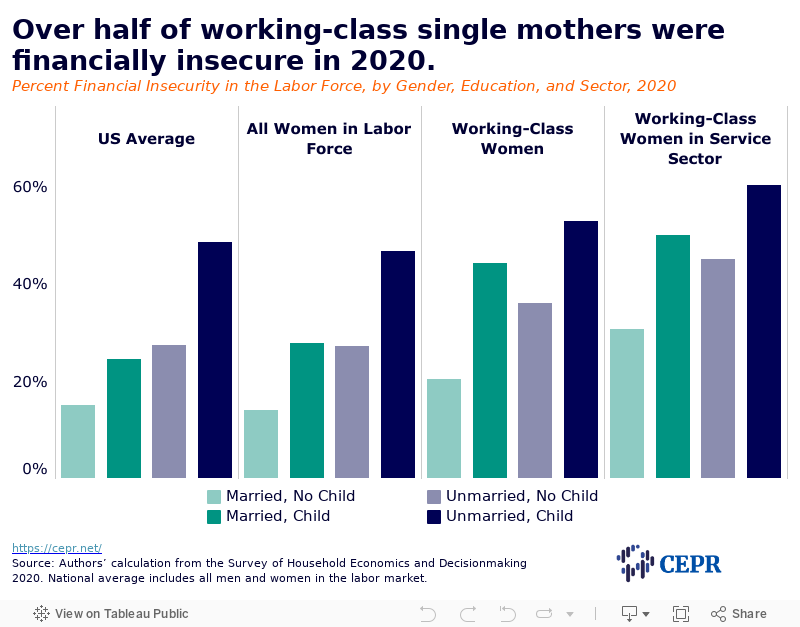

PC: I’ll start with women because I have lived it, you’ve lived this, we’ve lived this, we can talk about this for days. I think it affects women in different ways. There are financial implications. There’s information that shows that women are more likely to end up in a place of financial insecurity simply because they have kids. The fact that they just have kids puts them at greater risk of having financial trouble in the future. We can talk about the motherhood penalty and how financially that will impact women. So there’s a financial component, and that’s an easy one to break down and there’s data to show it. The wage gap is smaller for people without children, but for people with children, it gets very big so there’s the “motherhood penalty.” So there’s that. There’s mental health, right? There’s straight up burnout and exhaustion. And I know personally, I wasn’t depressed but I was unhappy, incredibly unhappy and stressed. And that stress can be harmful to your health as well. Not just your mental health, but your physical wellbeing. We know that it impacts women’s mental health, physical health, emotional health, and their overall wellbeing. And there’s also data to show that single women live longer than women who are married with children. It does impact us negatively to be in partnership with men in particular and to have children because it creates more work for us. There’s so much that impacts women and I think that there’s so much information on this.

For men in particular, I feel like there’s a little bit less data to say how it negatively impacts them. Like tangible things to say that financially it hurts them. Because it doesn’t. It doesn’t hurt them financially. But I do believe that we really stunt men’s ability to be more than a “provider” and a protector. E. Rothsky I think says like, you put them in this little box and you tell them who they are and they live in this box and they can’t get out of that. So it creates this environment, I think, where I know my husband in particular wanted to be a great dad and a great partner, and when I would come to him and tell him the ways that I needed him to change, he’d be like, “Wait, but that’s not what I was told my whole life.” And then he would feel a lot of shame and defensiveness. So we had this relationship where I was unhappy and resentful and angry, he was feeling shame and defensiveness and he was hurt. He felt like he was not enough. He felt invalidated. Some men are going to say that his masculinity was being questioned. My husband didn’t say those things, he’s not that kind of guy, but that is a thing a lot of men feel, right? That their masculinity is being questioned and like everything they thought about being a real man actually maybe isn’t what they were told.

So it leaves men in this position where they don’t believe they can be both. Women, we were told we could be both. We could provide and we could have children. We could provide and we could be a partner. We could do all these things. And men have very specifically been told to be a provider and a protector, and that’s really all you have to be to be considered good. But I also think it puts them in a position where they have less strength in their relationships and in community. We know that they don’t have as many friendships or as strong of friendships. They don’t have as close of bonds sometimes with their children. And it’s interesting because men will often point to, “Well, the data shows that men are supposed to play with their kids and they don’t need to do the other stuff. That’s a mom’s job. Dad’s job is to play with them and teach them as adults, but we’re not important for bonding.” And it’s like, no, no, no, you absolutely are. You are incredibly important for bonding. And you’ll often hear new dads like, “Oh, she always just wants mom, she never wants me.” And I’m like, “How are you involving yourself in this process to make your child feel more comfortable with you and to want to come to you with those things?”

For children it’s so hard because I think, one, if you’re growing up in a home that’s unhappy and full of resentment and defensiveness and shame, emotionally, that’s not healthy. But we continue cycles when we don’t change this behavior, so our children are just going to end up in the same position we are if we don’t make changes to these things. So when I say to my son, “Go put your dish in the sink,” and he says, “Why?” I’m like, “Well, it’s about teamwork here. We’re all part of this home. We’re all part of this family. We all work together, and it’s not just mom’s job to do these things. I’m not just here in service of everybody else, right? We’re all part of this family.” So, I think the harm for them, I think it very much varies on what the home life is like. But long term, we’re just going to continue these cycles where women are incredibly unsatisfied and upset with their partners and men continue to feel like they can never meet that benchmark if they’re not willing to change.

AA: For sure. Okay, I want to ask you really quickly about two big social movements right now. First is the tradwife, or even more distressingly to me, the stay-at-home girlfriend movement, and then the 4B movement which is like one side of the spectrum and the other side of the spectrum. What are your thoughts?

PC: So the tradwife thing in the context of social media, tradwives, it really just feels like propaganda. It just feels like propaganda. It feels like a marketing tactic. I don’t even believe these creators really live this life. They live this life for the greater purpose of convincing other women of their purpose, right? So it has this larger meaning and it’s really not just about Ballerina Farm or Nara Smith or whoever. It’s so interesting, this tradwife thing, because I think what they’re trying to do and how they’re trying to position this, it’s really a phenomenon, it’s really blown up. And some people are like, “Yeah, I don’t believe those traditional values but her content’s kind of fun. It’s kind of funny when she makes homemade Cheerios” and I’m like, “Yes, but there’s a deeper layer to this.” If we just look below the surface, the content will change and the message does change with it. But when I think about it, I think what they’re trying to do is they’re trying to provide a solution to the problem that women claim to have, which is burnout, frustration, exhaustion, resentment, they’re saying, “Hey, you’re right. It doesn’t have to be like that. You don’t have to be burned out. You don’t have to be exhausted. You don’t have to be burning the candle at both ends. You could be like us. You could homestead. You could stay at home. You could submit to your husband. Who cares about silly work emails? Don’t bother yourself with that stuff. Take care of your children. You’re going to feel so much more fulfilled. This is the solution to the problem.”

And as a woman who’s been recently laid off and has taken a slight step back career wise, I still work, but much less than I was before because I was doing two full-time jobs, I can tell you firsthand that the corporate job going away has not made my day-to-day life much easier. I am still just as tired and exhausted and burned out because I’m still managing this home with four children, running to appointments, taking them to school, making lunches, doing laundry. And yes, I don’t have those emails at the end of the day, but my desire to have a life outside of my children hasn’t gone away. The issues are still there. The issues still remain that there is a lack of support for parents. And what I think often happens in these situations too, like when we think about a general stay-at-home mom, not a tradwife, just a woman who stays at home with her children, which is totally, totally valuable and a valid choice. It’s difficult for her to go to a doctor’s appointment because oftentimes doctors don’t let you go with your children. And so if she doesn’t have affordable childcare, if she doesn’t have the support system to watch her children, she can’t go to the doctor. So, I’m a stay-at-home mom, but I still need things like childcare and I still need time to rest and relax and recover. And I still deserve time to get dinner with my girlfriends, but I can’t do those things if I don’t have a supportive partner. I can’t do those things without childcare. I can’t do those things without a village, right? Even if we take out the tradwife of it all, these systemic issues still impact us, regardless of if we’re in a dual income house, a single income house, whatever that might look like.

And I think it’s overly simplified and it ignores the fact that it puts women in an incredibly difficult position, which is that if they’re in a position where they would like to leave that marriage, they can’t. They don’t have money, they don’t have support systems, they don’t have the means to do so. And I think for me, that’s like my biggest fear as a woman, is being put in a position where I don’t have choice. And I think that’s what a bit of the tradwife movement is, is limiting women’s choice. “Hey, look how lovely it is over here. Grass is greener. You’re going to be so much less stressed. We’re not going to talk about the fact that you’re not going to have access to any of your own money, you’re not going to have a credit card, you’re going to have no means to afford a different lifestyle should you ever choose one. And if your husband were to die tomorrow, best of luck. We’re not going to talk about that. We’re just going to focus on the fact that you no longer have that stressful job that is also burning you out.” So I think the tradwife conversation is not nuanced enough. It lacks so much context when we talk about it in the context of social media, at least. I haven’t seen as much, maybe it’s my algorithm, I have not seen as much the stay-at-home girlfriend.

AA: Oh, yeah, that’s a thing too. And I even saw one the other day that was even in Sweden, where they have so much more gender equity than we do, that’s growing in Sweden. Where women are opting out of the workforce when they’re like 20, 21, and they’re staying in these apartments, their boyfriends’ fancy apartments, and they do all of the home care and then they go pamper themselves. They’ll have a massage and then they’ll make sure he has dinner and they clean the apartment and he makes all the money and she makes sure his life is cushy and comfy. And I just look at that… I have four kids, three of them are daughters who are launching into the adult world right now. Thank goodness all of them know better than that, but can you imagine the risk that you’re putting yourself in in the prime of your life to not be building your own value and worth and savings and experience and networking, everything you’re going to need for the rest of your life? Oh my gosh, I’m so distressed by this trend and I don’t know how to combat it, actually.

PC: Yeah. And again, when we talk about these conversations, like acknowledging privilege, these women probably have a certain level of privilege and their partner has a certain level of financial contribution that allows them to do this, allows them to go get that massage, whatever it might be. Same thing with the tradwives. There’s a level of privilege and being able to live on one income in the way that they are doing it. So it lacks that context, but I think that’s the other thing that’s missing from these conversations. You can absolutely be a stay-at-home mom. Hey, you can be a stay-at-home girlfriend. I don’t care. Do what works for your family, for your partnership. But are there protections in place? Do you have a retirement account? Do you have your own savings account? Do you have full access to all of the money? Do you have a prenup or a postnup? What do you have? How are you protecting yourself in that situation? Because, yeah, all of these choices are valid. Hey, you’re married to a billionaire and you don’t want to work? Go for it. Totally fine.

And I think people often think that because I preach so much about financial independence and protecting yourself that I don’t believe that women should ever leave the workforce. And that’s really not the case. What I wish though, is that we had a society that valued the work women do at home so when they look to reenter the workforce, they actually can do so. And they can do so at a livable wage that honors the work that they did prior to children, if they were working prior to children. And that doesn’t exist. That is why it is so, I’m sure for you too, but that’s why it’s so scary for me. We don’t live in a world that views you as valuable if you left the workforce even for six months. Sometimes they’re like, “What’s this gap?” and it’s like, “Well, I got laid off and it’s a terrible economy, I don’t know. I didn’t know I had to justify myself so much for this six-month gap, but I do.” And I think both of these trends, because they’re trends, ultimately, don’t paint the full picture. I think it tricks women into thinking it’s this idealized version of motherhood or being a wife or a partner, but it really lacks so much of the context needed.

AA: Yeah, agreed. How about the 4B movement? Because again, that’s the other end of the spectrum where women are opting out of family and partnership completely. What do you think of that?

PC: This is a tricky one because people will be like, “Don’t you think it’s harmful?” and “Is that really the answer?” And here’s the thing. If it’s the answer for you, it’s the answer for you. If you choose not to have children with a partner, totally fine. I am all in favor of somebody who wants to be child-free by choice, who doesn’t want children, for whatever reason. If you don’t want kids, you definitely shouldn’t be doing this. That is for sure. If you don’t want it, don’t do it. It’s way too hard to be doing this against your will. Don’t do it. Even if you’re wishy-washy, probably don’t do it. Don’t do it. But the 4B movement, it’s so hard because I think, again, in the greater context, in the greater scheme of things, is it going to have the impact that we want it to have? I think on a personal level, yes. You can protect yourself from that situation. You can say, “Yeah, I’m actually not partnering with men. I’m not having children with men. I’m not doing any of those things with men because I don’t feel safe in that environment or that relationship.” And I think it’s a completely valid choice. We already know women are making this choice even without a movement attached to it. The birth rate is declining, women are having children later and later, if at all. They’re having fewer and fewer children if they’re having children. Women are already consciously making this choice. They’re having children on their own without partners, right? This is not new. The 4B movement has, I think, kind of given people something to look to to say, “This is an example of how we can make an impact,” so I’m very much in support of any woman who wants to do it.

Do what works for your family, for your partnership. But are there protections in place?

I just worry for our country that we’re already in this red pill era where these two things are just going to keep smashing up against each other. And at some point, some things got to give, something’s going to break. And I’m not saying it’s not a worthwhile effort, I just think there’s still so much to unpack in our country that I don’t know that it’s going to have the impact that people want it to. It doesn’t mean it’s not valuable, I just worry that there’s so many competing efforts in our country where there are the tradwives and the 4B movement and the red pill and all the things. All of it feels a bit marketing-y and not actually going to generate the change that we’re hoping for. I could be wrong, though, and I’d be happy to be wrong.

AA: It remains to be seen, right? Because it’s just starting out. On one hand, I think that’s a really compelling message that women are giving men. Like, “No, we’re actually not going to do this. We see how it was for our moms, we’re not going to do this.” On the other hand, it can provoke backlash, and then the conversation can stall. So, I don’t know. We’ll see how it goes.

PC: Yeah, because I think at the end of the day we all want the same thing. I only have one boy. I have three girls. I hope one day my son can grow up and find a partner, whoever that is, and be a dad if he wants to be, and show up in a really meaningful way and have beautiful relationships with his children. I want that for him. I do. So I want us to find ways to achieve that, not just for women, but for men too. I want us to raise boys who get to live in that world where we all get to benefit from these amazing relationships and experiences. And unfortunately right now, it just feels very much like a battle. And to your point, it didn’t happen overnight. This has been happening for decades, and unfortunately we’re kind of at this pressure point right where there are these really big movements happening and I think the question is, what are the end goals? What are we looking to achieve with them, and will it get us there? I hope something will, I really do. Too late for me, I’ve already got four kids and a husband. But I think it’s yet to be seen, to your point, who knows what this will look like in 50 years?

AA: Yeah. Well, my last question for you, Paige, is kind of on an optimistic note because we are making changes and it is important to acknowledge that things are better. Generally, the culture has made progress in terms of gender equity, but I wanted to ask you what you think the next steps are. What are some steps that we can take in our families right now to get toward gender equity?

PC: Sure. I really do think starting at home is a huge thing to do. Because if we can make these small changes in our homes, that will flow out into the world. It might not change everyone’s life, but it’ll change someone’s life. When I think about the things that we’ve tried to do, at least in our home, is first and foremost within our marriage, my husband and I finding equity. Equity, not just in the sense of who does what chore, equity when it comes to our time. I want free time, I want to go to yoga, I want to see my friends, I want to spend six hours on a Saturday doing whatever the heck I want and not telling you when I’m going to come home. I want to do that too. Finding equity in as many ways as we possibly can. And when I say equity, somebody asked me this the other day, “Why don’t you say equal?” Because equal is just not possible, ever. Especially as parents, our lives ebb and flow, our kids need different things, our jobs need different things, life is always evolving. So we just want to be fair and to work at home on those things in whatever way works best for you. And therapy, all these things, can help here. I think we work on our partnerships and from there we trickle down to our kids.

But also outside of our own homes. Yes, we need to be working on this with our sons just as much as we do with our daughters. We need to be giving them similar messaging, which wasn’t always the case. What’s that thing that everybody says? We prepared our millennial daughters to do anything they wanted but we didn’t prepare our sons for women who are doing this. So, doing that work, right? Preparing our sons, teaching them the value of care work, right? We just wrapped gifts. My son was wrapping gifts with me because he’s also a part of this home and he can wrap gifts and he buys gifts for his sisters. He does that work too. It’s not just my daughters doing that. So there’s that, but then there’s the conversations we’re having with other people outside of our home, which is half the reason I’m on social media, which is before I started talking about it, I felt really alone and I felt like there was really no solution. And once I started talking about it, thousands of women were like, “Oh my God, me too!” And men, I have men who message me and they’re like, “Thank you so much. I couldn’t understand it. I didn’t know what she was talking about, and now I feel like I have a better idea of it.” And talk to your friends, talk to your mom, talk to your sister, talk to your brother, talk to people at work about these things, bring it up. If you have HR and you feel like there are biases against women, talk about these things. And I know that’s hard to do for a lot of us. And again, privilege plays into some of this, but you can make change at home. You can make change in your community. You can make changes in your schools. You can make change in your workplace. You can make change, you just have to be loud about it. And that can be tricky, but I do think simply being willing to have a conversation with someone goes a very, very long way and recognizing that this is not an individual failure of any one person helps us navigate these conversations more easily when we can say, “Hey, none of us did this to ourselves. This happened. This is how we can go forward.”

AA: Mm-hm. Hear, hear. Well, thank you so much, Paige. This has been a fantastic conversation, and I’d love you to end by telling listeners where they can find your work, your social media and any other website or anything else you have.

PC: Thank you, yes. You can find me pretty much on all social media, Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, Instagram @sheisapaigeturner. I have a newsletter on Substack, again, @sheisapaigeturner and sheisapaigeturner.com. You can find me all over the place, where I talk about all of these things every single day. So if you want more, please do come follow me there.

AA: Awesome. Highly recommended. And again, thank you so much, Paige. I so enjoyed having you here.

PC: Yeah, so much fun. Thank you.

talk to your friends, talk to your mom, talk to your sister, talk to your brother,

talk to people at work about these things – bring it up.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!