“I wasn’t so much scared that he would shoot me as that my children would not have anything to eat”

Amy is joined by Dr. Srimati Basu to discuss her book The Trouble With Marriage: Feminists Confront Law and Violence in India and explore the complicated gender politics behind divorce.

Our Guest

Dr. Srimati Basu

Srimati Basu is a Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies and Anthropology, and a member of the Committee on Social Theory. She serves as the President of the Association for Feminist Anthropology, 2021-2023. Srimati has an Interdisciplinary Ph.D. from Ohio State University in Cultural Studies/ Anthropology/ Women’s Studies, and her teaching, research and community work interests include Global Feminisms, Law, Gender-Based Violence, Social Movements, Feminist Methodologies, and Masculinities. At present, she is writing a monograph on anti-feminist men’s rights groups, following a 2013-14 Fulbright Fellowship to conduct fieldwork with MRAs across Indian cities. She has recently begun a research project on Indian women private detectives with fellowships from National Endowment for Humanities/ American Institute of Indian Studies and from Sisters in Crime.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: For the past couple of weeks on the podcast, we’ve been learning about India. First through a study of the Hindu religion, and then through an examination of the caste system. Today we will shift to another important and fascinating topic as we highlight the book, The Trouble with Marriage: Feminists Confront Law and Violence in India by Dr. Srimati Basu, and I am so happy to welcome Dr. Basu to the podcast today. Welcome, Dr. Basu!

Srimati Basu: Hi, it’s so good to talk to you, Amy! I am so happy to hear the books that have been preceding this, because I think maybe if someone listens to them in order, it’s up a certain conversation.

AA: Yes, that’s the goal is to have the foundations taken care of first, and then we have context for what we’re hearing for the rest of the podcast. So yes, this is going to be a really exciting series on South Asia. Maybe I’ll introduce you first just with your professional bio, and then you can introduce yourself with some more personal details.

Dr. Basu is a professor of gender and women’s studies and anthropology at the University of Kentucky. She is the president of the Association for Feminist Anthropology from 2021 through 2023, and she has an interdisciplinary PhD from Ohio State University in cultural studies, anthropology, and women’s studies. And her teaching research and community work interests include global feminisms, law, gender-based violence, social movements, feminist methodologies, and masculinities. She has written extensively on these subjects and she’s the author of the book we’ll be discussing today, which I mentioned before, The Trouble With Marriage: Feminists Confront Law and Violence in India. Dr. Basu has also participated as subject expert in the UN expert group meeting on family policy development, achievements and challenges, and she has written for the Ms. Magazine blog, India Today, Times of India and Kafila.

So again, thank you so much for being here and now I’d love it if you could just introduce yourself. Tell us where you’re from and some personal details about your life and what brings you to the work that you do today.

SB: I grew up in India, in Kolkata. I’m one of those people who was an English Literature major who then took a slightly sideways turn into being probably primarily now an ethnographer and someone who’s interested in policy and law. You know, like many people, it was a class in grad school which made me think like, I just wanna do something that’s dealing with the ability to look at how the everyday world is functioning when you study law and its effects that really spoke to me. So I’ve been working on that. You know, you mentioned The Trouble With Marriage. I started out actually working on property law and now, following this book and in ways that when you hear the podcast you will understand, I’m writing about anti-feminist men’s rights groups who oppose these laws we are gonna talk about. So stay tuned for some years from now!

And this is my more personal occupation, I have decided that I’m now going to work on this project on women private detectives in India, or more broadly private detectives in India. So there’s that.

AA: Wow!

SB: Yeah, and I’ve lived in Kentucky for 16 years, so Lexington is a really very lovely town, I must say.

AA: That sounds like a really big change.

SB: You know, I lived in Indiana so I moved one state over.

AA: Oh, I got it. Okay. So it’s been kind of gradual for you.

SB: I mean, I lived in Indiana for a long time. I went to, as you said, I went to grad school in Ohio. I’ve always been in the Midwest until I moved here and I was like, oh the South, it’s just over there. But Kentucky is a place with a really strong sense of its history and culture.

AA: Yeah. That’s so interesting and I am very interested to read the work that you do on men’s groups resisting. I feel like that’s something that’s happening all over the world right now as kind of a backlash. And it’s really scary and disturbing. So yeah, I’ll definitely stay tuned for that.

Okay, so I wanted to ask a little bit more about what specifically prompted you to write this book, and then how did you conduct your research?

SB: For my dissertation, I had worked on basically inheriting women and inheritance in India. And that book is called She Comes to Take Her Rights: Indian Women, Property, and Propriety. And I had really wanted to find out what it is that takes people to the law. You know, we use this word “legal pluralism” sometimes, which means many things. One of the things it means is what are the kinds of laws for which people go to court, and what are the kinds of laws which you refrain from fighting a case because of whatever cultural reason or legal reason or whatever. So only to find out when I began studying property that actually women rarely took any family property that were disinherited from to a legal mediation. I mean they were routinely disinherited from their legal shares of family property by the logic of “do it for your brothers”, et cetera. Hence the name, the sort of animosity towards the woman who would seek her rights, so that’s why the book is called She Comes to Take Her Rights. And so I never quite got my fill off seeing what a courtroom did.

So I started this project because I was really intrigued to read that a particular style of family courts had started in India, which were lawyer-free courts. Now, the idea was coming out of a lot of alternative dispute resolution work in the ‘80s and ‘90s, that going to court is an intimidating experience, people feel really distant from it. And so women would go to court and say their piece, right? That’s the kind of founding logic of that. So I was just very curious about what it means to have a legal court without lawyers. That is where I started on the core of the project. I found it very generative in terms of knowing about how law works, you know, to be in a courtroom. Because typically, like I did for my first book, and like many, many legal scholars do, we often read cases off from the books. But you understand when you sit in a courtroom that so much happens through the little interactions between judges, other court officials, the atmosphere of the court shades some things, people bring different kinds of emotions that we don’t see in the written text of cases. So it was really instrumental to see that divorce, it’ll not surprise you to know, is a highly charged topic.

And anyway when I started that, I was just going to do an ethnography of the court, and I realized as I was sitting there that every few minutes there would be a contested case that would involve allegations of violence in some form. Let me add before we start, talking about some of those details, that it makes it seem from what I said that everybody’s getting divorced because there’s domestic violence. So I’m not saying those things. I think one of the essential things I was looking for is that neither divorce courts nor police courts are a good way to measure the amount of domestic violence there is. Because of the ways in which laws work, divorce courts are really not very good at giving Indian women a livable income based on the amount of labor and time they have put into marriages.

So like states in the US that don’t have community property laws, India has no matrimony property laws. So essentially you get a form of alimony, which is sort of living wage level. You might get some money for child custody. This is not to say that middle class or elite women have not been, you know, tough negotiators and got themselves some good deals. But overall, alimony is a really poor way to get a fair share of what resources you have put into marriage. But it is commonly believed that many forms of deprivation that wives might feel themselves facing in households, not just that they have been physically beaten up on a regular basis – though that does happen and that is brought up – but that if you frame your grievances through criminal case law, because criminal case law involves so much more potential loss to the person being accused, sometimes in terms of the law that exists, their families might be also arrested along with husbands, which is a long trajectory of Indian law.

But, you know, it’s complicated with their jobs, it’s complicated with things they might apply for. So that criminal law accusation, whether or not it goes forward, has some kind of legal leverage against the divorce cases. So it’s common that people file cases in criminal court and civil court simultaneously. Now, as you saw, this all sounds super advantageous, but that puts women and men in very tricky positions. You don’t know where to start. You don’t know what is supposed to come afterwards. You don’t know what the exact correct behavior is. And it also puts judges in this family court that I was sitting in, it just irritates them to know that the divorce case is complicated by criminal cases. So I found that actually judges and counselors in this new style court, who I think are actually quite sincere about wanting to help women economically, they want them to have as good a solution as possible, they find themselves focusing on that. All of their attention is: let’s get her a living, let’s get her to be able to live on her own. You know, sometimes the families they were born into might be supportive, might be not. Sometimes they may have paying jobs, sometimes they may not. So there’s a lot of focus on getting them a living, but that sometimes means that you have to turn away from some manifestly oppressive situation that the person is in.

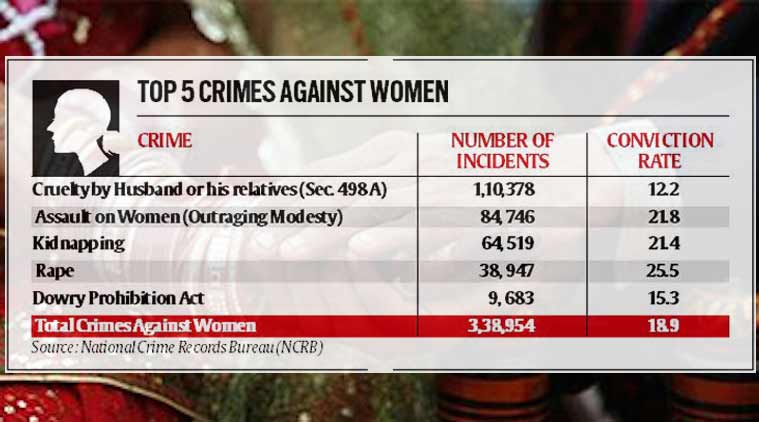

And I recount a mediation in a feminist organization, and this is not an organization whose feminist creds are in any dispute, but when your client comes to you and says, “I’m not ready to live life as a divorced person,” then all you can do is strategize how best to live with violence. Part of why the book is called The Trouble with Marriage has to do with the fact that we see, like, it’s all about putting all one’s eggs in the basket of marriage, as it were. As in preserving the economic and social rewards of marriage becomes the focus rather than autonomy. All the focus falls on keeping marriages going as a social fabric, no matter how many problems we might see. And whether those problems are physical violence or not, we don’t know. It’s not always clear. These domestic violence cases are often filed but dismissed. And even when they go through the courts, the conviction rate itself is very low. So the conversation between these different bodies of law is what really interested me.

AA: Mm-hmm. And it is complicated, and that comes through in the book for sure. I wonder if we can start off as a foundation by having you quickly tell us some of the defining features of marriage in India. And I know we talked about this before where I said “throughout history” and you laughed and said you want me to talk about this marriage for 5,000 years of history! So, no, not through all of Indian history, but just some of the defining features so we have kind of some context.

there’s a lot of focus on getting them a living, but that sometimes means that you have to turn away from some manifestly oppressive situation that the person is in

SB: I won’t, in fact I can’t do 5,000 years of history. I can barely do almost 300 years of colonial relations. But we know that in India, like many other countries that had European colonizers, made a very concerted effort to try to institute laws. Sometimes by looking to the laws of the country where the colonizers were from, in this case, England. But also to hire so-called legal experts to frame and codify these laws. Now, what happened there is that across a country that’s so diverse in terms of ethnicities, language, etc., there were a variety of marriage practices.

To take one small example, you have a lot of matrilineal communities where women have the foremost property rights of all. That doesn’t mean they control it and it’s all a utopia, but they had very strong rights to the property of the family they were born into. So there’s that. Even in more patrilocal cultures, there would be systems through which people could petition to get out of marriage. There are marriage systems where marriage payments are in the form of dowry. In many of those, we saw that there were negotiating systems where people could make a case for themselves, make a case for livelihood. There were many large kinship structures where you can sort of claim lifelong maintenance in a family unit if something happens to you.

So one of the main things in colonial law is that this affected codification, since you were just talking about caste, was to hire a bunch of high caste scholars in order to make a code which heavily favors a Brahminical, Hindu, more northern Indian bias in what happened to all of those laws. The other thing, as soon as I said Hindu, I realized that I have to go back and explain that it was part of colonial laws in not just India, and not just in South Asia, but in all over the world that colonizers maintained this illusion that they were not at all interfering in anything to do with family law. That they were only interfering in the laws of revenues of business, you know, or criminal law. Even in civil law, the illusion is that they were not interfering. And one of the ways they tried to preserve this illusion is that they often saw a place like India through a religious lens. So they separated the laws of Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Zoroastrians, among others. Those are the four main big bodies. And there was a kind of a dream around the time of independence in the ‘40s and ‘50s of having what is called a uniformed civil court, in which people would just have a court across these things.

Now, that has not happened. The best we have been able to do is to try for at least even alimony, custody, etc., across things but it’s a complicated process.

AA: Well, that’s one thing that keeps coming up over and over again as we are studying different places through this season of the podcast, is how much European colonizers changed the structure of families and the legal system. And usually it was a change toward patriarchy. It created systems that were far more patriarchal than they had been prior to European colonization. I guess I knew that happened, but the extent and the universality of that happening all over the world, everywhere that England touched basically, really surprised me.

SB: I mean, the US is a really good example, right? There was this obsession with having them dress in blouses so that they would be civilized instead of whatever clothing they wore. To have a male head of household and the moral authority of doing a particular thing…

AA: Yeah. So, two really striking anecdotes and examples from the book, maybe I’ll share them really quickly and then ask for you to respond to them, were of young wives who had just gotten married. And the first one was a young wife who had gone to live with her husband’s family, which is the tradition in a patrilocal society structure. So she went to live with her husband’s family, and she kept making mistakes like you do when you’re first married and you’re adulting for the first time. But she kept making mistakes, like forgetting how many cups of tea she was supposed to make, and her own father was worried about her. So he came over to her husband’s family’s house to help his daughter because he knew she was struggling. And first of all, this was just so touching to me to think of this dad who loves his daughter and he’s coming over to try to help because she’s having a hard time. But the in-laws perceived her connection to her own family as a threat, and they kicked her out and they ended up in family court.

And then the second example I wanted to share was a young wife named Priya, and she was adjusting to life with her in-laws. And her mother-in-law constantly criticized the way she cooked, the way she did household tasks, and then one time in the middle of an argument her mother-in-law told her, “One day, I’ll burn you to death.” And Priya also mentioned that her father-in-law made sexual overtures and so she felt very unsafe, understandably, in this environment. And one thought I had was something that we’ve talked about before on the podcast, which is how a patrilocal system really does disadvantage a young bride who’s been far away from her family of origin, far away from her community of origin, and that can be dangerous for women.

So I wanted to know if you wanted to talk about that. And then my second question is, what legal protections exist for young women in these situations?

SB: There is something about this form of patrilocality that was seen to be like you are essentially at the mercy of these people. In terms of how much food you get, in terms of whether someone’s being nice to you or not, where are your relatives, it’s all of that, right? But I think it’s crucial to not let women’s parents off the hook in the system. So in these cases, It’s not like her family is necessarily going to have her back. They’re not ready to share their resources with her either. This is core to The Trouble with Marriage that they have married her off and here we go. Sink or swim. So that is what subjects people to balance.

So in the first case that you talked about, which really was a very poignant case, it’s in a chapter where I’m looking at what happens in cases of mental illness. So in that case, both families, her natal family and her in-laws, her affinal family are unwilling to support her. I mean, the dad is irritating the in-laws by showing up and making tea because he feels tender towards her, as you pointed out. But really he doesn’t want to be responsible for bringing her back to his household. So I think the real poignancy lies in this person not having a support system that is either of those things, or not having resources to count on that system. And, you know, state systems of support are not really a good source. I mean, they’re very meager and they’re very random and not good.

So then what happens to someone who is unable to do that, but even in the best of circumstances, what happens to someone if they are living in a patrilineal household if they don’t have a job? In effect, same thing, right? Or you have not been raised to be in the labor market in a particular kind of way. But you know, there are lots of cases of really well-known murders actually, where the women had perfectly good jobs, but they brought much of that money they were supposed to give to the in-laws or something. So Pauline Kolenda many years ago did, since you mentioned that word “patrilocality”, she looked in Southern India at places where there were patrilocal systems. They were technically patrilocal systems, but the women didn’t marry very far away from their households. You know, if your family doesn’t live very far away, then at the very least they can pop in, they can keep an eye on you. Sometimes women in her study had a plot of land that they could have, so they had some source of support that was not like that.

So I think the point here is more about what your sources of support are. Can you count on your family? Let me just say about the other case since you mentioned it, I think part of that joint household and part of why Indian family law very often, when there is a case of domestic violence, very often the parents-in-law are implicated, is that there is kind of a lot of unwelcome labor put on this daughter-in-law that comes into the household. In this case, you know, they are modern women just like the rest of us. They’re looking forward to being new brides and to leading their new life, and a lot of this doesn’t sit well with them.

I think the point of the example that you picked is the counselor telling me how good her skills were in dealing with this. And her skills were to convince the woman to make a home for herself in that house first. This is a very seasoned counselor in the court. She was a seasoned political counselor before the court started. I don’t see her as a person who necessarily supports people beating other people up, but she’s speaking as this seasoned auntie who wants her to just be happy where she is. But to go back to her, this is a person who has walked into this household where she doesn’t like all the things. She’s unhappy because she finds her father-in-law creepy. She finds her mother-in-law really ornery, and I think we could take the “one day I’m going to burn you to death” as a rhetorical move rather than a murder threat. But the fact of someone constantly complaining about the million tasks is not pleasant nonetheless.

AA: Right. So yeah, even if it’s not a real threat to have someone say that to you…

SB: It’s just not a good thing to live with, right? And if you remember, I cite Amita Dhanda’s work on appellate cases where people bring all sorts of cases as insanity cases, such as serving the wrong bread, or expressing the wrong affect, not knowing how to behave this. So anything to get rid of this person who’s in trouble.

AA: Okay. Do you wanna talk about the legal protections that exist for women?

SB: Yeah, okay. So what could a woman such as Priya do in those circumstances? It would be the same things I said. She could just leave, she could get a legal separation. She could go to divorce court, she could go to the local police station and file a so-called “first information report” alleging that there had been a threat or there had been a sexual threat. She could bring a sexual harassment case against him. I mean I’m just telling you, all of these laws exist. Laws are plentiful.

Now, who is going to support her, including her parents in all of those processes, that’s the question. Is she going to have a place to move out to and live? Is she just gonna go rent a room somewhere? The sort of shelter system that we think of here is not at all well established, partly because kin take you in rather than an organized shelter. So, I think there are legal protections a-plenty of various, various forms of gender-based violence and also against divorce. But who and how you access it is the question.

AA: Mm-hmm. And am I understanding correctly then that it would not necessarily be common for the bride’s natal family to take her back in?

SB: I optimistically think – and I not just optimistically think, I just saw a study where there was a little bit more hope to that – that sometimes now families do feel more like maybe they should pony up to it, maybe because there is more in the air about women claiming more of their inheritance. I mean, there’s not any observable large movement on it. So people are unwilling because, back to patrilocality, you think bringing your daughter back to the household means that when the parents passed away, she will be living in her brother’s household. And neither the brother nor the brother’s spouse, who has been told that is her only home, is all that happy about it.

So actually you are setting up your daughter to be kind of a hanger-on in a household but she might not be very welcome either. I mean, that’s the problem. To not have given her an equal share of the resources you had and/or to have brought her up to be autonomous through the labor market, you know?

AA: She’ll be a dependent of her brother eventually.

SB: Yeah. Unless she can have a job good enough for that.

AA: Got it. Yeah, that’s really interesting. Okay, let’s talk about the history of divorce law. So there were a few questions, and my first one is the role of religion in India’s marriage laws.

they are modern women just like the rest of us. They’re looking forward to being new brides and to leading their new life, and a lot of this doesn’t sit well with them

SB: The role of religion, I think, is that there are separate personal laws, as they’re called codes, for different religions. Personal law includes laws of adoption, divorce, inheritance, and custody and guardianship, as it’s called. So these are slightly different codes for Hindus – Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains are actually counted as Hindus – the second for Muslims, third for Christians, and fourth for Zoroastrians. These are legal codes. You would go to a judge of whatever religion, and it doesn’t matter what your religion is and what the judge’s religion is, she or he would judge it according to the code of the books. I think that’s something people don’t often understand.

Now, certain religions actually allow for, notably Islam is really one of the most flexible religions for negotiating marriage rights. So there’s been lots of Muslim women’s groups in India that have actually wanted to negotiate really good contracts for women who are leading that marriage. Now, it’s slowly, maybe hopefully percolating, but one of the legal provisions that Islam has allowed and that exists within the Indian system is these Darul Qaza codes, that are sort of informal dispute resolution courts where there is a qazi who will hear your cases and give a solution.

So that’s a way in which a Muslim woman might choose not to go to a legal court and to get this kind of arbitrated judgment that has legal standing as far as I know. None of the other religions allow for that. Your average Catholic priest might be able to mediate some agreement, but it would still have to go through other kinds of courts. So because Islam has it mandated within the court, it’s an established kind of practice.

AA: Well, I’m gonna reveal my ignorance because now I am thinking, as I was reading the book, I remember thinking wait, what are the laws here in the United States? Like if you have a fundamentalist religion, it could be any of the fundamentalist Christian or Jewish or Muslim or something here…

SB: I mean, if you’re a Hasidic person, you consider yourself to fall under a certain kind– I mean, just to take kind of a mainstream community, let alone small Protestant communities that might exist, right?

AA: But US law will accommodate religious law and will uphold that?

SB: Not necessarily. For example, I wouldn’t be polygynous in the streets.

AA: Right, right, exactly. So I mean, I’m coming from a Mormon context and that is an example that came to my mind that they won’t uphold your religious belief if you’re polygamous.

SB: But that’s because Utah gave that up, right? So I mean, in effect plenty of people are polygynous, but the state doesn’t recognize that. Canada has toyed with trying to work that out, I don’t know the details though.

So you can avail of a divorce, whichever religion you are under those provisions, but there is a fifth thing that is called a Special Marriage Act. It was also founded or established shortly after these marriage courts. So the Special Marriage Act is for people of different religions, sometimes different castes, and so it is the only provision of a secular marriage act.

AA: Another question is what the role has been of women’s rights activists in India, in marriage law and divorce law. What role have they played?

SB: We should just note that India has a very old and robust women’s movement. Since the early 20th century, but certainly since the UN decade, in the ‘70s that really got people together. I think that they have had a voice in the writing of a lot of policy, in the writing of a lot of laws. And you know, India’s known for having a lot of non-governmental organizations that deal with gender. So it’s not just that it’s a few powerful people at the levels of government. It’s percolated through all sorts of levels. You know, there’s a lot of local level work across the country.

But one of the highlights of the women’s movement was in the ‘80s. To have a say, I mean, the family courts come out of something that the women’s movement wanted, so that’d be easier for women. And this freedom from violence is probably the biggest issue around which the women’s movement organized. So they influenced and have continued to influence since the eighties, the shaping of rape law. This whole apparatus of criminal law for prosecuting domestic violence. So many of the cases I looked at, which in India are 498A, so there are particular clauses of cases that can be brought under that. So all of that came about in connection with the women’s movement, objecting to how just normal gift-giving dowry practices had become extortion. Not that dowry itself had been illegal, but the way it was being exercised led to a bunch of legislation that affected how these dowry laws sat with domestic violence laws, all of that.

So now, we are in a different phase in feminism also, that we are looking for the ways in which gender is written into those laws. So for example, this case that criminalized sex between specifically gay people – in the last few years there has been a lot of movement around what trans rights should look like. So the government recognizes it in a way, but in a way that’s felt to be totally inadequate. I think there’s a long history of protest and struggle around gender, around the question of women, but also more recently around sexuality.

AA: Since you mentioned the code 498A, I’d love it if you would talk about that a little bit more. What it is, and then one really interesting section of the book to me was men’s complaints of its misuse.

SB: Let me just say to start out that section 498A is the law under which domestic violence is prosecuted. It’s a very stern act on domestic violence that can include all sorts of behavior. It can include your usual recognized forms of physical violence of being beaten up, but it also includes verbal violence, also economic violence, all of these. And framed in a way that it’s not supposed to be negotiated away. But of course that’s not true. It is all the time. I mean, that’s one of the main ways in which it is used.

The thing that is seen as most crucial, and the thing that men’s rights activists probably most object to, is that husbands and their entire families can be put into prison for– I mean, some gigantic number of women who are in prison are there on 498A related charges. So that’s one of the main ways you can actually put a woman behind bars is through that case. And also, I mean this all has been modified. They’ve been going on at it about the law for so long, that’s how this has been modified, but it used to be that because it was seen as such a critical intervention, that you didn’t need preliminary investigation to file that. Now, some of the corruption around this then involved the cops. They could say to a particular family, “There is an order against you. I could take you off to prison. What’s it gonna take to not do that?”

AA: Oh, and bribe them, or extort them kind of.

SB: Or they might say to the woman’s family, “What are you going to do to make me have that happen?” It leaves a lot of power in the hands of the police. I don’t have to tell you for people in the US that you know it is best to be wary of the kind of arbitrary power that the police hold over you.

But because it is such a heavy law, it’s also seen to have a lot of effective power in negotiating these things. As I was telling you about, people really fear that it can mess up their lives. It’s a proper criminal act, right? In many government jobs, which are pretty lucrative jobs in India, it’s a mark on you. You can’t be a government servant who’s convicted of domestic violence. So it’s a big thing. So for many years people worked to establish the Domestic Violence Act, which was passed in 2005. Lots of women’s organizations have found it to be a pretty advantageous law in helping, like judges have helped them in getting protection orders and in getting certain kinds of recourse. But the men’s groups thought the criminal intent was the bad thing in domestic violence cases, but they are not any happier with the civil act. Because I think they see it also as a way in which they are deprived of homes, possibly, that the burden of proof for accusation is quite low, etc.

So I’m not seeing that it has eased any tensions. It’s kind of seen as one more case that can be brought against husbands. Hence there is this whole aggrieved thing about it. It’s about the force of criminal law being used supposedly to push against unhappiness in marriage. They would say unfair unhappiness in marriage, in their accusation sometimes just a way to get out of marriage and have the husband pay for it for the next 10 years. Those we can take with more of a grain of salt, but yeah.

AA: Sorry, I hadn’t thought to ask this before, but do you see a better solution than 498A? Is there something that would protect women and that would have more societal buy-in?

SB: If you ask me, I think we should go back to the point where men and women are both raised to be in the labor force, to be autonomous as they want, men and women to be raised to have laws of equal inheritance from their families so they can fall back on that. And if you are married, if you are divorced, then matrimonial property, as you know in community property states in the US, should ideally measure the amount of time you were married and the amount of labor you put in and how much human capital you lost as part of it. If you worked out of the labor force, how much of your work potential was lost? How much have you contributed to this person’s business? How much have you put into it?

That would be a fair way to split the division of assets, right? Then it gives us room to look to bring domestic violence cases to court. In cases that have a clear line of whether it’s physical violence, whether it’s certain kinds of verbal violence. In the US, in India, everywhere cases are convicted not on some slight that somebody said, cases often have a kind of sustained weight to them. So people bring a lot of pain and hurt and disaffection to this, but that doesn’t often rise to the level of a case that’s a conviction anyway. So I think criminal convictions should have a criminal drought, and distribution of resources in marriage should have a fair matrimonial property law under it.

AA: I’m gonna say something that I guess is really obvious, but it just struck me again how when I asked about what you would change, and I’m thinking in terms of gender-based violence, that your first answer was kind of about economics. And about women being able to earn their own money and women being able to inherit, and that provides autonomy and it took me a second to make the jump and remember that that often is why women do have to stay in abusive, violent marriages is because they can’t support themselves outside of it. And so that’s why those things are so connected. And I guess, again, I know that’s really basic and elementary, but it just drove it home for me.

SB: You know, just to bring it back to the US for a second, I’ve worked in three shelters in different states, and you can see that clearly the reasons that people stay – I’m not saying love, affect, wanting a family aren’t a big part of it – but economic exigencies are really heavy in why people cannot leave their households. I remember a person who’s a law professor now, a really well-known person who writes on domestic violence law, I heard her say at a talk that when she was living in this really dire situation, like every form of violence you can think of, scared of all of that. She said, “I wasn’t so much scared that he would shoot me as that my children would not have anything to eat.”

I think we should go back to the point where men and women are both raised to be in the labor force, to be autonomous as they want

So, I always think that the solution to domestic violence has to lie in economic autonomy. So in the US it is theoretically easier to find. I’ve watched this many times in shelters I’ve worked at. People come in and they’ve thrown away a bunch of things. They have to go back to school, which they abandoned because this man told them it was a great idea. They have to establish credit, they have to find housing. I mean it’s possible, but it’s hard. They face a completely different kind of life than what they have been used to. So, yeah, it’s all of those things.

AA: Yeah. And everywhere.

SB: Everywhere.

AA: So the last question I wanted to ask you about is Chapter Six, and the title of that chapter is ‘Sexual Property, Rape and Marriage Conjoined’. And there are a lot of really interesting topics in this chapter, but one of the ones that I thought was really interesting was this concept that men would be accused of tricking women into having sex with them, with the promise that they would marry them later. And then women claiming that this was rape in these circumstances. I thought that was so interesting. Do you wanna talk about that a little bit?

SB: So to start out, rape law in India, not just in the US but just globally, there is an understanding that rape is fundamentally about a violation of bodily integrity and a violation of consent. It is tied, as you know, to sex. It is tied to a moment of sex. So that is not necessarily how courts and judges who have grown up here, I mean the US is no better at this. It often takes a lot to get the discussion away from “Was there force? Did she resist?” But its intersections with marriage are a different thing altogether. There is this trajectory of rape law where it’s believed that the good woman only has sex under conditions of marriage. Otherwise, the unmanaged woman who is having sex therefore is… Why would she do that? She would be throwing away her future, in the logic of patriarchy, right? Her womb belongs to the patriarchal family.

So why would she be having sex with this guy when she was not married, unless he had promised to marry her already. Now, it turns out, if you look at the case law there are a certain number of people who actually believe in this who have indeed lured someone by saying, “oh yes, my wife is going to leave me any minute.” Or not even that they’re married, “I’m just waiting for my mother to come around to this” or you know, I mean maybe they pretend to be a lover that they’re not. So it’s not that there are not those people. The question is, are those cases breach of promise cases? Are they some kind of violation of contract cases? Or are there rape cases? Because do they involve non-consensual sex? Depends on, that’s a thorny question of what constitutes consent. I mean, was that person’s consent to sex having nothing to do with it? Barely not, right? In those cases, it has nothing to do with her pleasure, nothing to do with her body, nothing to do with her autonomy, but just about whether it was under the promise of marriage or not. That is a lot for a feminist reckoning to deal with.

But so that right there, is it non-consensual sex? If she was raised to believe that she was never going to have sex unless there was marriage on the table, then is that rape? My question is what happens to your consent and your pleasure and your sexuality in there? But it’s an interesting debate. When I began looking at these cases, they would be like, “Oh, she was agreeable once,” you know, it also uses problematic logic that does not sit well with how you might think about consent.

But I came across this case where a man who was an actor had the police come to his play as it was closing down, this really well-known actor, and the police were waiting for him because his partner at the time had filed rape charges under these promise to marry cases. Now, they had been living together for 10 years. There were no allegations that any sex in that relationship was not consensual. When they got together, she had been going through a divorce, so they couldn’t get married when they first got together. I mean, she was also an actor, so they lived together for a long time. Then she was divorced and said they should get married. And he didn’t say “I’m gonna be done with the relationship.” He didn’t say “I don’t love you anymore.” He just said, “Why don’t we not get married?”

And so that was prosecuted as a Consent of Marriage case, which seems to be, I mean, I have a problem with consent having no relationship to the body and only to everything that is implied in marriage. And so when I began looking into that, I saw that there were a number of cases, very often of young couples like my students’ age, who were in relationships as you know, it’s part of life. I would say teens, twenties, and later, you’ll be with someone and break up with someone. And if sex is non-consensual, there are ways to go about it. But sex in a relationship is not tantamount to a promise to marriage. So, all of this law, this implication of rape and its shadow of marriage has always seemed to me to be very problematic place how we think about consent. And this is not helped by the fact that the whole legal thing, as you have read– It’s not some medieval idea a person has to marry their rapist. But there is a steady stream of accused rapists who will go to court and say now he’s going to agree to marry her. And once in a while, there is a judge who goes along with it.

So you were struck by this case in which this nurse was raped by another staff person at the hospital who left her horribly injured, almost blinded, stuffed in a closet. She basically survived by pure fluke. Then when he went to court, he was like, “I could offer to marry her.” And she said, “You should enhance his sentence just for saying that.” So there’s this way in which this idea of marriage being seen as a prize in sex is the problem on both sides of it. On both sides if marriage should be an offer from rapists. Like, what is that? And the price of sex should be marriage.

So all of this drew me into a sort of parallel thinking about it because it was about how marriage is seen as sort of women’s economic harbor. And it is always around this sort of, the shelter that marriage provides, the economic haven that marriage provides, that comes to shape even rape law. So that was my foray.

AA: Yeah, so, so interesting. Well, and then again to your point, it just seems like the solution to this problem is further down at the root, and it’s to make it so that marriage doesn’t have to be the harbor for women. That people can enter into marriage as peers and equals to form a partnership, and not because the woman needs to be taken care of.

SB: And then you can like sex or not, on its own terms.

AA: Right, exactly! Well, this has been a fascinating conversation. I learned so much from your book and from talking to you today. So Dr. Srimati Basu, thank you so much for being with us on Breaking Down Patriarchy today.

SB: Thank you so much, Amy! It’s been such a pleasure to talk and I look forward to reading this and more over there.

AA: Yes, thanks so much.

All the focus falls on keeping marriages going as a social fabric,

no matter how many problems we might see.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!