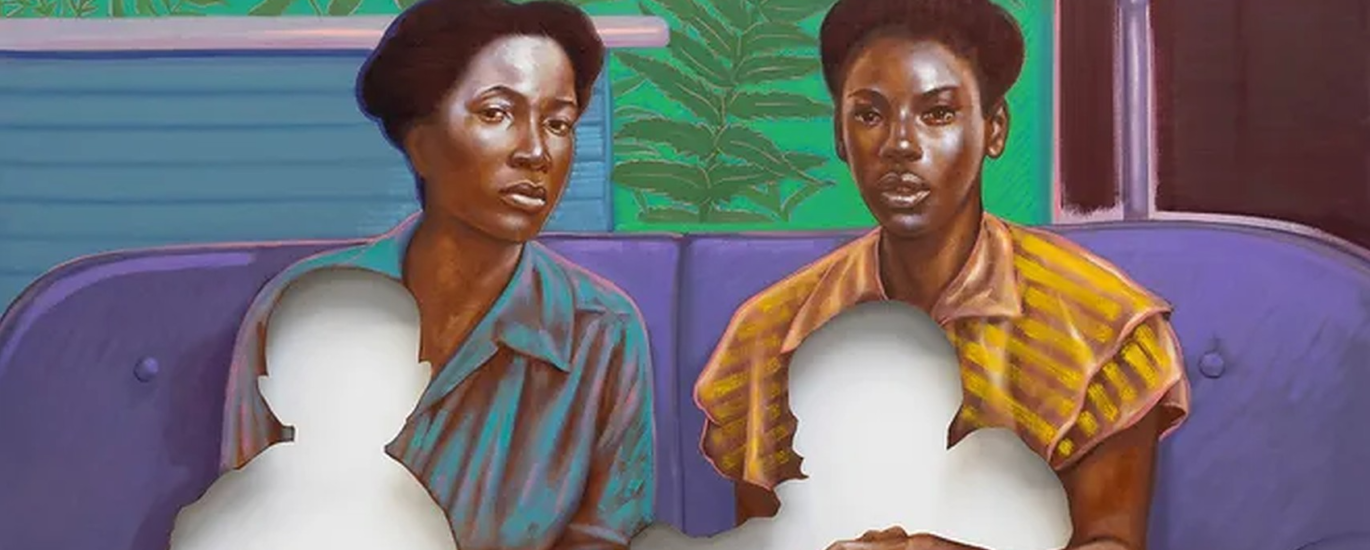

“Women are enough.”

~

In her landmark book, Of Woman Born, Adrienne Rich writes that “At certain points in history, and in certain cultures, the idea of woman-as-mother has worked to endow all women with respect, even with awe, and to give women some say in the life of a people or a clan. But for most of what we know was the “mainstream’ of recorded history, motherhood as institution has ghettoized and degraded female potentialities.” In this quote, Rich highlights the stark difference between the way our cultural thinks it respects women and the way it actually regards them. It can be a wonderful thing to praise mothers — to celebrate the women around us who channel their love, energy, and resources into the art and the work of raising children — but too often we forget that our cultural ideal of a ‘mother’ is not always accessible nor is it the ideal motherhood for all women. So what happens when a mother doesn’t match up to our institutional expectations? And what happens when a woman decides she doesn’t want to be a mother at all?

On today’s episode, we’re digging into these questions as we’re joined by two spectacular guests each trusting us with her own story of how motherhood as an institution has haunted their lives: an Anonymous Contributor who speaks about the realities of unwed motherhood, and returning friend of the podcast, Lane Anderson, who shares her own experiences of having the mantle of motherhood assumed and foisted upon her.

Our Guests

An Anonymous Contributor

&

Lane Anderson

Lane Anderson (she/her) was raised in Salt Lake City, Utah. She has an undergraduate degree from BYU, and a graduate degree from Columbia University. She has spent much of her career as a full-time journalist, publishing hundreds of articles on inequality, human rights, gender, and social and family issues. She has received several Society of Professional Journalists Awards, and a fellowship from the USC Annenberg School of Journalism for her writing on human trafficking. She lives in New York City with her partner and young daughter, and she is full-time faculty at New York University where she is a Clinical Associate Professor teaching writing. She co-writes Matriarchy Report, a newsletter about family issues from a feminist perspective on Substack, and on Instagram @matriarchyreport

PART ONE.

Anonymous

My first experience with patriarchy begins at pre-birth. I was born to unwed kids, a white girl and Polynesian boy, in the murky stage between adolescence and young adulthood. Both were unprepared for the reality and responsibilities that came with parenthood. But one of them bore the sole responsibility.

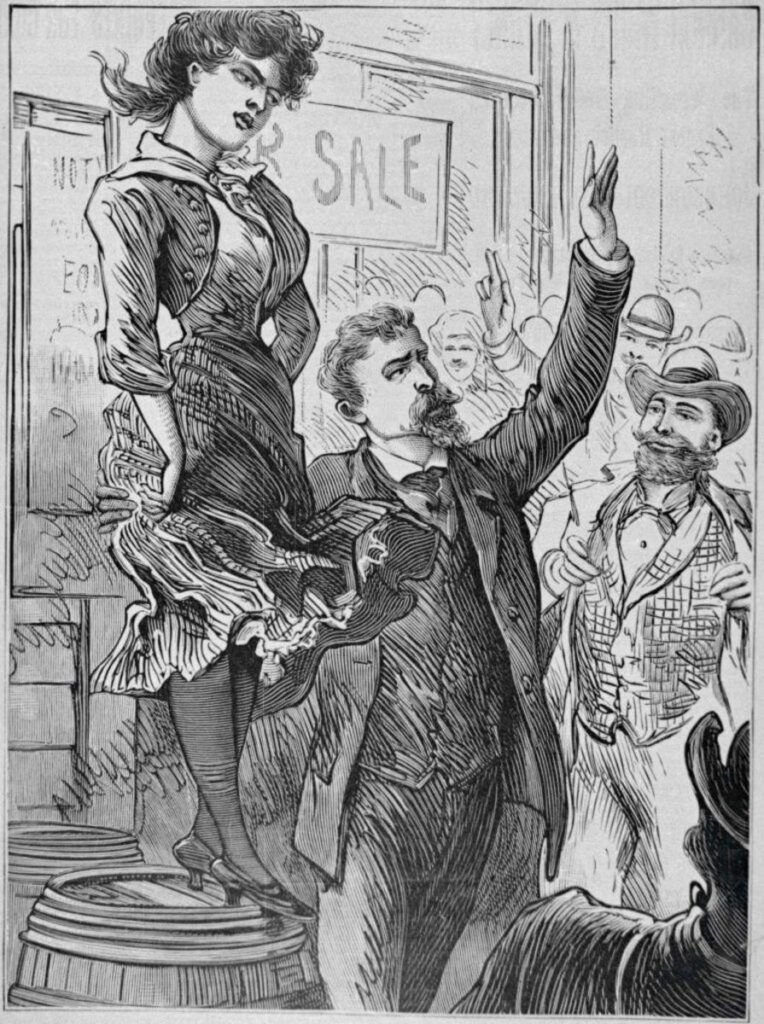

For the past 35 years, the stories about my birth have always been framed around my mother’s actions—getting pregnant was her naïve, youthful attempt at getting my father to commit long term. The primary blame was placed on her. If there is any power in words, then framing a teenage girl as responsible for the actions of two condemns her to a lifetime of social ostracization.

There isn’t a part of my life unaffected by the story of my conception. I will always be, “one of those,” the bastard, the child born out of wedlock, a phrase I loathe. It’s the years of people whispering disdainfully about others’ unwed pregnancies, not realizing I too was the consequence of such a pregnancy. Many times I’ve heard people say, “Did you hear SHE got pregnant?” and my rephrased response, “How dare HE impregnate her!” That response will stop people in their tracks. Truthfully, people don’t recognize the folly of their snap judgements. Afterall, they are simply echoing the environment we are all steeped in. They might not mean to say harmful things, but they do. And those words hurt everyone touched by this issue.

If there is any power in words, then framing a teenage girl as responsible for the actions of two condemns her to a lifetime of social ostracization.

Growing up, I was smothered by the consequences of sex. I was the living embodiment of consequences, making it impossible to forget. There are tender stories, many too difficult to detail here, of the instances where the island community my mother lived in blamed her for her pregnancy. The stories of being accosted publicly. The painful moment in a church meeting where a woman gave a pointed rebuke to my grandmother, stating that her own children would never make the same sinful choices.

My mom was disciplined by her church leaders for getting pregnant. My grandparents moved her away from their small island community because they received word she could potentially be excommunicated from their church.

But where was my father in all this? My father remained in the same small island community and did not receive the same intense condemnation. However, his mother was publicly shamed for his actions. Ironically in some instances, he was celebrated for getting a white girl pregnant. Most damning, he wasn’t threatened with the same religious sanctions my mother was despite belonging to the same church. He was, as they believed, just a knucklehead boy who got caught up in the moment.

I don’t think those community members realized that they were not only laying the blame at my mother’s feet, but they were also putting the blame on my grandmothers as well. They saw my maternal grandmother as responsible for my mother’s mistake and my paternal grandmother also hid in shame. Because, after all, this is a woman’s issue, right?

…people don’t recognize the folly of their snap judgements. Afterall, they are simply echoing the environment we are all steeped in…

Growing up as a mixed-race child of a single mother in a predominantly white community, you realize you are different. After my birth, the responsibility of childcare fell on my mother. My father was absent. When my mother couldn’t care for me, that responsibility fell on my maternal grandmother.

Thankfully, my maternal family, who raised me, never made me feel like a mistake. But because of the general upset with my mother’s actions as an unwed mother, I couldn’t help but feel responsible.

I remember my mom recalling, “Other girls were having sex—I just got caught.” She was wrong. We both got caught. It was years of glances and whispered comments about my parentage. It was strangers stopping us in grocery stores asking my mother which adoption agency she got me from and the awkward conversations that ensued. It’s the funny and sometimes painful conversations correcting assumptions that your parents were married or how uncomfortable people are discussing teen pregnancy, regardless of how seemingly accepting they are. Funnily, I‘ve always related to stories like the ones in Jane Austen’s novels with characters who were born under unseemly circumstances.

My mother’s statement about getting caught has stayed with me all these years later.

In adolescence, I decided I’d never get caught because I was going to be a paragon of sexual virtue. I fell deep into purity culture as a way to keep me safe from any sexual impulse.

When I began dating in high school and later seriously in college, I vacillated between wanting to kiss and feeling shame for wanting it. In the back of my mind I worried, “But what if we kiss and then we have sex and I get pregnant?!”

Logically I knew how a woman gets pregnant. But I didn’t know the stepping-stones that led from A to B. Does it start with casual kissing? Will it happen if I touch him a certain way or if we lie down together? What if I, the guardian and gatekeeper of life, accidently were to make the same situational errors my mom and several of my teenage girlfriends had made?

And then, if I did suddenly find myself skipping dangerously down the path to sex—what does it mean for me? Does it make me a harlot, less worthy, less desirable?

In my mind, having sex and falling pregnant was the worst possible outcome of adolescence. Maybe the most damaging belief was that if it happens, it’s because you weren’t strong enough to avoid it. If, like me, you were raised in a religious environment that taught you that you were responsible for a boy’s thoughts depending on how you dressed or behaved, you felt doubly responsible for carrying both of your virtues. And because I was the consequence of unwed teen pregnancy, I already felt unclean. I felt like I needed to prove to everyone I wasn’t going to be like my mom. I’d be better. I’d be a mountain fortress, so unscalable that no one would breach my walls. But it turns out that that solution doesn’t work long term or facilitate healthy relationships. At some point, my walls had to come down in order to trust that kissing wasn’t a slippery slope to pregnancy.

I’m not here to blame anyone because a lifetime of mulling over blame has not solved the core problem. I’m interested in challenging our deep biases about sex and the institutions that distort our attitudes towards women and sex.

Birth control is one example of how we place the burden of sex on women. The belief is that for men, sex is a diversion and for women, it’s an experience laden with duty. Research shows people generally believe women are primarily responsible for obtaining birth control. When birth control became available in the United States in the 1960s, public health campaigns focused on women getting oral birth control, despite the fact that condoms are readily available without a doctor’s visit or prescription, are widely used, and can be purchased by anyone.

More current research, conducted in 2018 in the peer reviewed journal Culture, Health and Sexuality, showed that men find it difficult to reconcile the idea that women should have control over their own bodies with the idea that men should take equal responsibility for contraception. According to the authors, there is a disconnect between men supporting egalitarian sexual decisions but ultimately defaulting to not participating equally to obtain contraceptives. Somewhere along the way, a woman’s right to access birth control became translated into a woman’s responsibility towards contraception. And many contemporary men are left bereft, trying to support a woman’s right to use birth control while not stepping on their toes. It’s created an awkward dance where men don’t want to get involved or overstep and women feel that they don’t have adequate support in making decisions around contraceptives. We’ve failed both women and men in this regard.

How do I know that our general attitudes blame women? Look no further than the media that frames women as homewreckers in consensual adulterous affairs. Or at rape culture that asks what a woman was wearing or if she fought back hard enough. Then there are religious leaders who urge women to keep men’s thoughts pure by not dressing provocatively. It’s the opening phrase in Hamilton that refers to his father as a Scotsman and his mother as a whore. It’s all around us. I too have blamed women.

…for men, sex is a diversion and for women, it’s an experience laden with duty.

I blamed my mom for all the issues around my birth. I blamed her because everyone else did and my birth father was absent, so she was an easy target. If only she had tried harder, like my religious leaders taught us. If only she had been better, it wouldn’t have happened.

How can we create a culture that includes men more in contraceptives, family planning, and sexual education? How do we encourage men to see themselves as equally responsible for planning and actions around sex? How can we challenge conventions evidenced in Dua Lipa’s song, “Boys will be boys, but girls will be women”? How do we challenge conventions that lay blame on women? How do we empower girls and boys to be equally engaged in the process?

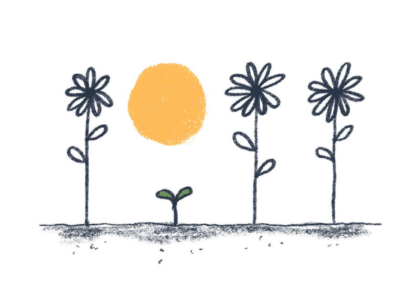

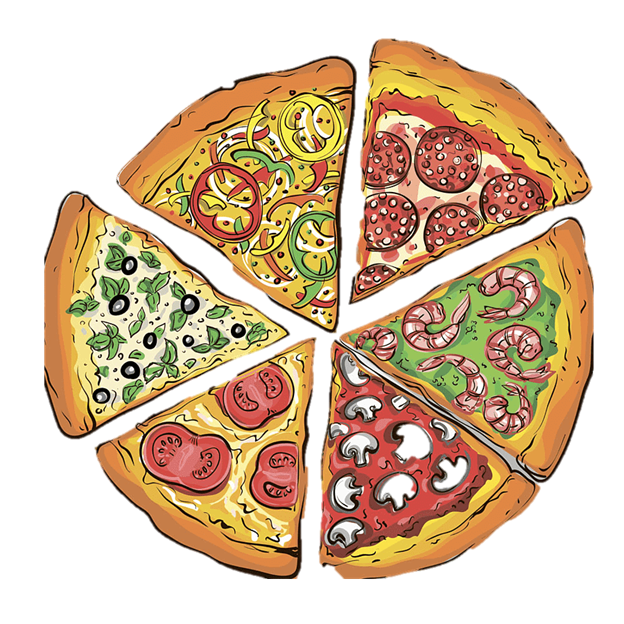

I love the part in Peggy Orenstein’s book, Girls and Sex, that quotes educator Al Vernacchio on sex being like ordering pizza; both partners mutually agree on which pizza parlor, what time, which crust to order, what toppings they’ll have, if the pizza should be half and half toppings, how much cheese, what sauce, etc… This suggests a model beyond the typical baseball analogy of men hitting bases with women, a model that empowers all partners of all sexual orientations to be equally responsible for consent, birth control and safety.

In my home, we teach our children that our collaborative duty is to protect one another equally. It has created a deep sense of justice in our home—to the point that if one of my kids is teased by a neighbor kid and the other one is there but doesn’t say anything or joins in, they know they’ll get an earful from me about how we protect one another.

I hope that my husband and I will have instilled in them the message that safe sex is the responsibility of all participating parties. I don’t want them to fear sex like I did. I want them to be so overstuffed with education, awareness, and empowerment that conversations about consent and condoms will be as commonplace as discussing their day.

In the end, there was no single victim in my story. We all were victims. My mom was a victim of a system that blamed her, and consequently had to live with the fallout. My father was a victim of a system that downplayed his actions, so he didn’t believe he had equal responsibility. My grandmothers were victims of association. My aunt was sexually harassed repeatedly by older men who leered and asked if she was easy like my mom. My grandfathers were victims of a culture that told them ‘this is a women’s issue’. And I was a victim, because I would forever be the living embodiment of their mistake.

But I am not a mistake like my culture made me believe.

You may disagree with my opinions. You may have experiences that contradict mine. I’ll hold space for you. Can you hold space for my story too? I’ll also shine a light on the many women who have walked this lonely road and have experiences so similar to mine. Our stories are too numerous to discredit as anecdotal.

I am a woman committed to asking hard questions, even of myself. A woman who is committed to challenging the social conventions that women are the guardians of men’s virtue, that men are incapable of being collaborative in birth control, that virtue is tied solely to one’s so-called sexual purity, and to challenge the belief that women are responsible for unwanted pregnancy. If we have a loved one with an unplanned pregnancy, our first question needs to be “How can I support you?” We need to focus on support rather than shame. These kids born to these pregnancies should not grow up in the heavy shadow cast by their birth. They are not mistakes.

I am not a mistake.

PART TWO.

Lane Anderson

I used to hate Mother’s Day. I dreaded it. I dreaded it so much that I started planning ahead for Mother’s Day so that I could deal with it. Usually I planned to get brunch, get my nails done, and turn off my phone.

It was important to turn off my phone because I would inevitably get pinged with messages that said things like:

Happy Mother’s Day! You are a wonderful nurturer in your own way. Or, Happy Mother’s Day, our kids think you’re great.

Some women who don’t have kids like getting messages like this. I did not like it. There’s no reason to message someone on Mother’s Day, after all, if they are not a mom. Unless you think of all women as moms, or would-be moms.

I mean, people haven’t sent me messages on Boss’s Day, or Secretary Day, or Father’s Day, or any other role-specific holiday that doesn’t apply to me. Only on Mother’s Day. If you think this isn’t that odd, ask yourself if you would text a guy who doesn’t have kids and wish him a Happy Father’s Day. No? It’s weird, right? I have polled men without children to see if they are similarly pinged with messages on Father’s Day, and they are not.

So why is this happening? This is happening because we have conflated the identity and worth of women with motherhood. I say we, because I was roped into this idea too, from the time I was very young.

I was raised Mormon, and on Mother’s Day, the leader of the congregation would ask not only all the mothers to stand, but all the little girls to stand, too. Then, men and boys in the congregation would distribute a token gift — usually a single rose or some chocolates — to all the girls and women standing in the pews–all the mothers and “future mothers” in the congregation.

There’s no reason to message someone on Mother’s Day, after all, if they are not a mom. Unless you think of all women as moms, or would-be moms.

This gesture, which now strikes me as a cross between a scene from “The Bachelor” and “The Handmaid’s Tale,” left me fuming in my pew, even when I was 12. It presumed the role of mother was what I wished for, and that it defined my future. The boys didn’t get the same treatment on Father’s Day; they got to keep sitting in their seats just being boys, or I presume, “future men.” The implication was that there were no women, or future women— only mothers.

The message that women’s worth lies not in their personhood, but in their childbearing and child-caring, is reiterated in a million ways, and not just in religious circles. We also see this in public discourse. When leaders respond to sexual harassment and assault allegations—from the Trump tapes to the Kavanaugh hearings—they often make statements about protecting “mothers and daughters.”

“We should always honor and respect the dignity of our mothers, sisters and daughters,” Ben Carson stated in regards to the Trump tapes.

Mitt Romney decried Trump’s words as “vile degradations [that] demean our wives and daughters.”

But do you see what’s happening here? These statements position women’s worth in relation to men and children — instead of as people who are deserving of respect and rights as individuals. This can make women, as individuals, undervalued or invisible.

The implication was that there were no women, or future women— only mothers.

I’m reminded of a time, when I was in my early 30s, when I attended a yoga class with a friend. When she went to introduce me to a group of moms she knew through her kids’ school, she said, “This is Lane, another mom from the neighborhood…” Then she caught herself and said, “I mean, she’s a future mom from our neighborhood.”

There was an awkward pause; then I corrected her: “Uh, I’m a woman from the neighborhood,” I said. Then we all laughed, and she apologized. But how interesting that the word “woman” simply didn’t come to her!

I’m also reminded of the time when one of my close male friends mentioned to me, unprompted, how nice it was that I nurtured my university students as a professor, which, he noted was a kind of “mothering” of its own. Never mind that my university students were adults who did not require mothering. he had also forgotten that at the time I was no longer teaching but was working as a full-time journalist. I was not performing “nurturing” in my day-to-day journalism life at all, unless you counted my succulent garden.

But the underlying assumption in these comments, as with the Mother’s Day messages, is that for women to feel good about themselves and their place in the world, and for others to feel good about women and their place in the world, they must be nurturers or “mothers” in some sense. Even if that sense is entirely fabricated.

It should go without saying that this should not be the case. Mothers are female-identifying parents. Women are female-identifying people. Both are equally worthy because they are humans. But too often being a woman is deemed not enough.

In my early thirties I got married, and the marriage ended a few years later. When I moved out, I rented a tiny but lovely Carrie Bradshaw studio apartment, which was the first place I had ever had all to myself. One morning, a few months after I moved in, I woke up with a familiar crushing weight of failure and disappointment. I had never imagined this life for myself—alone, without a husband or children, where had I gone wrong?

And then, that morning, something shifted, and I almost laughed out loud. I was a woman with a graduate degree, a job, her own apartment, living on her own in New York City, lying in her own bed and living her own life. This was failure? My life was beyond what I had imagined for myself as a little girl. Where had this idea that I was failure come from?

The idea that we are failing without men or children attached to us—or that we are worthless if we are not spending our adult lives serving men and children–comes from our upbringing, our conditioning, our churches, it even sometimes comes from the people who love us but received the same bad ideas.

It’s also actually ingrained in our history in ways that most of us aren’t aware of. I recently learned about the legal term “coverture.” Coverture is a legal concept that American colonists brought over from England, that held that no female person had a legal identity.

At birth, a female baby was “covered” by her father’s identity, and then, when she married, “covered” by her husband’s. This is why women held their father’s names, and then as a transfer of identity, took their husband’s. Because they did not legally exist, married women could not make contracts or be sued, so they could not own or work in businesses. “The ghost of coverture has always haunted women’s lives and continues to do so,” writes women’s historian Catherine Allgor.

Coverture was allowed to stand in the drafting of the U.S. Constitution and is why women weren’t regularly allowed on juries until the 1960s and weren’t allowed to own property or have a bank account. Today coverture has been chipped away at, but women still encounter coverture in real estate transactions, which nearly always name the male as the borrower and woman as co-borrower, even if she has more wealth. They encounter it in tax matters, employment, housing, healthcare, and multiple other systems that were built to assume that women had no legal standing of their own.

No wonder “women” don’t seem to exist in so many of our institutions and conversations. When our country was founded, legally, they literally didn’t exist. There were girls—property of their fathers, and wives—property of their husbands, but freestanding women were not part of the collective and legal imagination.

My life was beyond what I had imagined for myself as a little girl. Where had this idea that I was failure come from?

Over the years, I have had to fight for my self-worth as a woman without a man or children attached. I have had dozens of exemplars to aid me in this, mostly peers, mostly other women without children. They have taught me how to rely on my own self-regard, how to enjoy the singular pleasures of earning and spending my own time and spending my own money. How to struggle and fail and rely on myself. How to build my own life full of adventures, and fulfilling relationships, and how to build my own Ikea furniture. How to make a home filled with my own books, and art, and if I felt like it, mermaid decor.

Three years ago, after forty years of being child free, I got pregnant. Although my partner and I had hoped for the pregnancy, I found myself struggling with a profound loss of myself as a woman. The title of mother, I feared, would erase what I had fought for and grown to cherish — my womanhood. My hard-won autonomy and self-regard as a woman, and nothing more.

Now on Mother’s Day I get different messages on my phone, ones that congratulate me and celebrate my long-delayed motherhood. But for many years, Mother’s Day was a day when it was indicated to me that being “just a woman” left me lacking, incomplete.

So now on Mother’s Day I remind myself to be grateful for my womanhood, something that I wasn’t taught about and had to discover for myself. And this is something that I will pass on to my daughter — teaching her the joy and challenges that await her as a woman, whether or not she chooses to become a mother.

Mother’s Day will always be a day that I remember to tell her what was seldom said to me on any day of the year: Women are enough all on their own. Women are enough. Women are enough.

Women are enough.

*Note: A version of this essay appeared previously in The Salt Lake Tribune

Boys will be boys

but girls will be women

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!