“I want you to feel angry that a woman in your community

doesn’t have the same basic privilege that you have”

Amy is joined by author and educator, Dr. Michael Kaufman, to discuss the manosphere, loneliness, hatred, and other risks to today’s men and boys, plus practical advice for men who want to help themselves and others by getting involved in the work of gender equity.

Our Guest

Dr. Michael Kaufman

Michael Kaufman, PhD, is a writer of both fiction and non-fiction books. As an advisor, activist, and keynote speaker, he has developed innovative approaches to engage men and boys in promoting gender equality and positively transforming men’s lives. Over the past four decades his work with the United Nations, governments, non-governmental organizations, corporations, trade unions, and universities has taken him to fifty countries.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: A little while ago, one of my listeners messaged me to ask, “Why are you having so many men on the podcast? I thought this was about telling women’s stories.” I understood her concerns. Sometimes women really do need our own spaces to tell our stories and to feel understood and validated, but that’s not this podcast. Breaking Down Patriarchy is a project for everyone. All listeners and viewers of every gender, age, race, physical ability, social situation, religion, all people have something to learn here, and all people have to be involved to break down patriarchy and other unjust, harmful systems. We need everybody. In some ways, you know what? We especially need men. There are still, sadly, many environments where women are either not invited or where our voices are not heard or heeded. We need men’s allyship and involvement in breaking down patriarchy because men have access to levers of power that women still don’t have. So I am extremely grateful to men who are engaging in this work side-by-side with us and leading the way in educating other men, reaching men’s hearts and minds in ways that perhaps women still cannot. One of these men who is doing the work is Dr. Michael Kaufman, who joined us for season four of Breaking Down Patriarchy, and I am so excited to have him back. Welcome, Michael!

Michael Kaufman: I’m really pleased to be with you once again.

AA: Michael Kaufman, PhD, is an advisor, educator, activist, and writer focused on engaging men to promote women’s rights, end gender-based violence, and positively transform men’s lives. He’s worked in fifty countries with the United Nations, governments, unions, companies, universities, and NGOs. He’s been named one of the hundred most influential people on gender policies in the world, and today we’ll be discussing issues that he raises in his book Men and the Gender Equality Revolution: Essays, Articles, Manifestos, & Rants From Forty Years of Scholarship & Activism. And actually, we’ll be drawing issues from all of your books, Michael, I think we’ll be pulling from a lot of different things you’ve done. And again, it’s so great to have you back on the show. I’m really excited to dig into these issues. But first, for listeners who didn’t get a chance to hear you last year when you were on the show, can you start by telling us a little bit about yourself, where you’re from, and the life circumstances and choices that led you to do the work that you’re doing today?

MK: Well, I grew up in the US. I was born in Ohio, and around 1960 we moved to Durham, North Carolina in the midst of racial segregation. And that changed my life, and I’ll tell you one way it did. My parents had a rule and that was that we didn’t go to any restaurants, any movie theaters that were racially segregated. Now, as a little kid, you just want to do what all your friends are doing. And so I said, “Well, why can’t we?” And they said to me, “As long as everyone can’t go there, we don’t go there.” So, at a really early age, they taught me, “You’ve got to take sides. You’ve got to decide whose side you’re on. Even if it doesn’t get you everything you want, you’ve got to choose which side you’re on.” When I reached university and my women friends were feminists and they were active in the early women’s rights movement, I was one of the men who said, “Yeah, this makes sense to me. I’m on your side.” Particularly because I had four wonderful sisters and I had wonderful parents and it just made sense to support women’s rights. But here’s the thing. I thought I was doing a great job, but it wasn’t until about 1980, so years after I thought I was right onside, that I really started to think about my life as a man. I really started to think about the ideas that I had internalized and my self-conception and why I was trying to live up to these ideas of manhood. And I realized that not only might those ideas, ideals, and practices be harmful to women, but also harmful to men. And that started a long project over the past more than four decades, oh gosh, of thinking, not only working actively as a writer, as a consultant, as a speaker, as an activist in support of women’s rights, but also to positively transform the lives of men. And that’s what I’ve been up to. I guess I should say that I also write fiction. That brings me a huge amount of joy. If you want to talk about fiction, we can do that too.

AA: Awesome, yes. And I know that even your fiction has some of these themes present, right?

MK: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

AA: That’s so great. Well, I want to narrow in on a story that you tell in this particular book, Men in the Gender Equality Revolution, where you had an experience at the University of Toronto in the women’s studies class, I think it was the first women’s studies class at the university, and you showed up as an ally and what happened, Michael?

MK: Yeah, so this is a good example of what I was talking about when I thought I was onside, but I just didn’t get it. Here we were, this is the early 1970s, the first women’s studies class, the room was just packed, there were women like hanging off the ceiling. And myself and another male friend went and we were the only men in this big campus, University of Toronto, who were there. And as I like to tell the story, we were brilliant, talking about this and talking about that. So smart. And at the end of the class, the professor came up to us and she said, “Thank you for your support. Please don’t come back.” I thought, “How could this be happening? I mean, here we are in support.” And I didn’t understand until years later that in spite of being well intentioned, we had reproduced all the patterns of men taking over conversations. And anyway, it was a learning experience, shall we say. But I think it’s a good example.

I tell the story a bit to tease myself, but also to illustrate what I think is a key point for men who want to be allies, and this is one of the themes in the Male Ally Handbook, which is my other new book. And one of the themes is the importance of listening, of thoughtful listening, and not just of men rushing in to show, you know, how smart we are, how onside we are. And I think that not only around men and women, but any allyship. If I, as a white person wanting to support anti-racist causes and work for equality, as a straight person supporting LGBTQ rights, whatever it is, it’s going to start with listening. And there’s a reason for that. It’s not out of some sort of collective blame or guilt or anything like that. It’s just being thoughtful. It’s saying that there are people whose life experience is very different from mine, and if I want to understand it, I just have to listen. It doesn’t mean I have to agree with everything I hear. It doesn’t matter that this one person or that person has four corners of the truth, but it just means I have to step back, try not to get defensive, just take it in and learn from that. I think that a lot of the work as allies, and certainly as a man working as a male ally for women’s rights, has to start with thoughtful listening. Just be willing to hear some things that might make me squirm a bit, but just say, “Okay, I’m here.”

AA: That’s awesome. I love that story. I’m so grateful that you include it in the book, because it does introduce the tone of like, “I don’t take myself too seriously.” But it’s also super helpful to have that modeled and to say, “Listen, this was me. And then I learned from it.” And I agree definitely on those other positions of privilege. Even for me, I had an experience recently watching a video on Instagram by a woman of color that I really respect, and she said some things that even I was like, “Oh, I’m sitting uncomfortably with that” and felt a little bit defensive. And as I thought about it more and just let it sit there, I actually did the exercise of like, how do I feel when I speak from my experience to men and they respond by saying, “Well, I’ve never done that.” I just think, “You’re not willing to learn then,” and it shuts the conversation down. I thought, “Am I doing that here?” And it was really useful. Once I flipped that, I was like, “Oh, I think I have more to learn.” So listening, starting by listening and then continuing to keep listening, I think throughout our whole lives probably, because we still have so much to learn.

MK: Well, it’s so much to learn, but it’s also the result of privilege. When we’re in a group that has had, as a group, social privilege, if we’re in a group that enjoys privilege because of our sex or the color of our skin, or our nationality or what our first language is, or physical or mental differences, sexual orientation, whatever it might be. What privilege does is it gives you only one slice of the world that you see the world through that lens. And so to appreciate other people’s realities, it requires that listening. We just don’t know. I remember when I first started learning, a number of years ago, about the impact of “casual” forms of sexual harassment, and it was from a good friend who told me about walking in the park one day. We were talking on the phone and I was going on about this beautiful autumn day we had here in Toronto and this beautiful walk I took. And she was just stony in her silence. And finally she said, “Michael, let me tell you about my walk yesterday.” She was walking in a park and some guy started following her this way, that way, made her feel really uncomfortable. She passed a park bench where two men had been talking, they stopped talking, they started making some sounds or something. In other words, what for me had just been a beautiful day, and that’s part of that male privilege, for her had been an experience of harassment and fear.

Here’s what I learned, though. I know I learned about her experience, but I learned about how I might react to that. I started apologizing to her on behalf of mankind, you know? And she said, “Michael, why are you apologizing? You didn’t harass anyone yesterday. You didn’t harass me.” And I said, “Yeah, but–” she said, “No buts. I don’t want you to feel guilty for something you didn’t do, I want you to feel angry. I want you to feel angry that a woman in your community doesn’t have the same basic privilege that you have to walk in that park without harassment.” And that taught me a big lesson. It taught me, again, that lesson about listening, but also about the impact of privilege. Things that I don’t even see because of my experiences. And it’s not to say I should be guilty that I was born with this skin color, or this sexual orientation, or this sex or whatever. But it just means I have to be aware of the impact of that. I have to be aware of what comes with that.

AA: That’s so helpful. And I have to say, too, when I talk to friends of color we’ve really dug in in several different conversations to white guilt. And what they’ve said is that it’s not helpful, actually, you feeling guilty. Especially for things that you haven’t done, it doesn’t do any good for anybody. But what we do need is for you to validate and care about our experience, which is different from guilt. And then if there are things to do to help, instead of spending your energy feeling guilty, spend your energy trying to change the world. Work within your community to make it less racist, work within your community to make it less sexist, which is what you do, Michael. So I appreciate your friend saying, “I don’t need you, Michael, to feel guilty. You didn’t do anything wrong.” But just sitting with it and being like, “That sucks. Oh my gosh, I’m so upset that that happened to you. Tell me more about it. I care that that happened to you. It’s real, and then let’s try to keep changing things.” That was awesome. Thank you for sharing that.

what for me had just been a beautiful day, and that’s part of that male privilege, for her had been an experience of harassment and fear.

I’d love to start with one of my biggest questions for you. It’s been on my mind constantly, I think it’s been on a lot of people’s minds for the last few years, especially. We’ll start with establishing, first of all, we both know patriarchy is a system where men inherit privilege and power relative to women, and all of our societal structures have historically been organized around patriarchy. Our government, religion, law, commerce, all this stuff historically has been patriarchal. And I’m going to quote you in your book Men and the Gender Equality Revolution. You write: “Though men hold power and reap the privileges that come with our sex, that power is tainted. There is, in the lives of men, a strange combination of power and privilege, pain and powerlessness.” And I’m really trying to understand this on a deeper level how men do experience structural privilege, but at the same time, so many men truly do feel– I truly feel like it’s not a gimmick. Maybe in some cases it is, but in a lot of cases, men do not feel this sense of power and privilege that feminists are telling them they have. They’re actually really struggling. So I would love you to unpack that for us. Tell us about some of men’s legitimate struggles, and then we’ll talk about how we can help men face those challenges and heal from their own pain. And then I’ll have more questions for you after that.

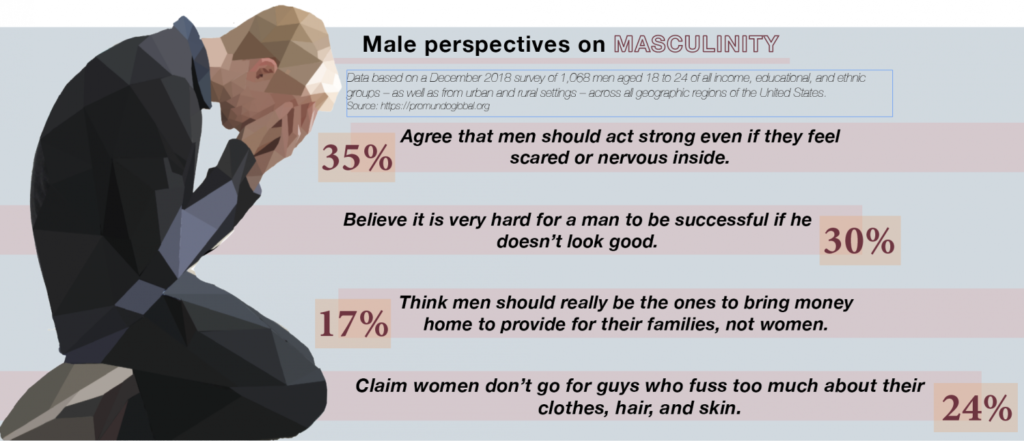

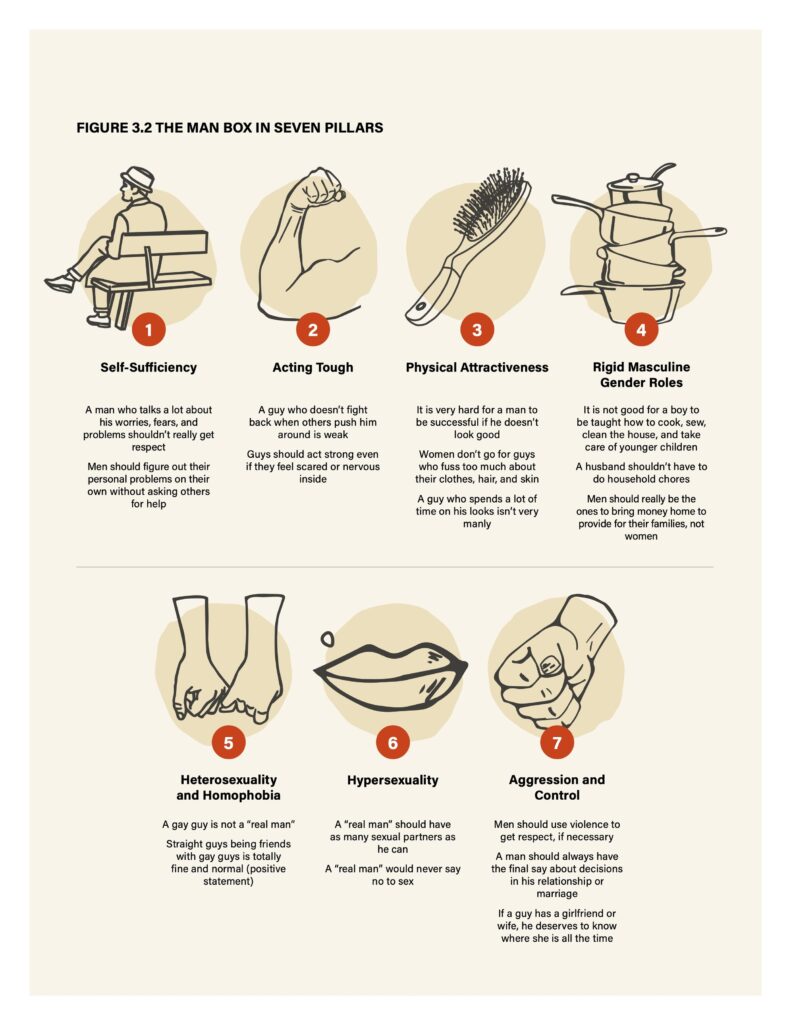

MK: So let’s think about this paradox of men’s power on two different levels. One level, you could say, is the psychological level with how we act or try to act. From birth, almost, we’re taught that to be a “real” man, you have to be strong and powerful and in control and not show or even have too many feelings, that you don’t back down, you make a lot of money, you’re great at sports, you drink, whatever it might be. And these things can vary a bit from one social group to another, but the common denominator is that you will be powerful. As a little kid, of course you don’t feel powerful at all. You’re told you don’t have any power. But then you look at the world of men and this man seems really powerful and this one does too, and perhaps you have your father act in some ways that are powerful. You see those men in the movies or on the sports field, “Oh, those are the real men.” You’re just this little boy. And so finally, you reach puberty and your friends are around you, everyone’s acting tough and learning to fight and drink or whatever it might be. And inside you’re still maybe learning those things too. But you still feel the same, you still feel sad sometimes, and you feel scared sometimes, you might feel just happy and goofy sometimes, you have this whole range of human emotions that you learned are inconsistent with being a real man. And you look around and you see, “Well, he doesn’t seem to have those feelings. He’s never scared.” He’s this, he’s that. In other words, we just see what all the other boys and men are projecting onto the world, the suit of armor of “I’m a real man.”

But inside there’s this dialogue of self-doubt about making the masculine grade. And that’s why we see, particularly among teens and young men, this is one of the most dangerous times for engaging in risk-taking behavior to prove you’re a real man, committing violence, whether it’s against other boys and men as you get older or against women and girls. This idea of having to prove to others and yourself and your friends that “I’m a real man.” And, of course, it’s impossible. Because we’ve set up a set of expectations that no man can live up to. I mean, I do personally, of course.

AA: Haha.

MK: But that sort of softens for most of us as we get older. We start realizing that a lot of this is nonsense, but not totally. It’s still there in different ways. So that’s one level. But the other level is this. We say that men have relative power and privilege as a group in relation to women. But the thing about a patriarchal society is that it’s not only a society of men’s power over women, it’s also the power of some groups of men over other men. So when we think about it, imagine going up to that man and, you know, he works in a factory, he’s being paid just crap, he can’t afford the things that he and his family would love to have. He has a boardman telling him what to do all day long, and I go up to say, “Hey, you’re awfully powerful. You must feel powerful.” Or a Black man who’s experiencing racism, “You must have a lot of power and privilege,” and we could go on with example after example. But the truth is that we exist not only as men with power and patriarchy, but also as humans who have other experiences and other relations to the world of power whether it’s because of our socioeconomic class, our nationality, our ethnicity, our religion, our sexuality, our physical or mental differences. All these things confer not just those emotional doubts, but constantly our experiences of not having power, of not having privilege. And so we have to be really careful.

It’s no surprise that right now in the US, if we look at how people voted among those with less education, so more likely to be in lower paid jobs, were more likely to support a right-wing candidate who’s, well, we won’t get into that. Well, we could, but we don’t need to. But acting out of pain I would say, out of a lack of privilege and feeling the need to assert that. That gets very complicated. So maybe we should just leave all that out. I don’t know, but it gets extremely complicated. The point I’m trying to make here is this: that men have what I call a contradictory experience of power. That’s both the result of not being able to live up to the expectations of manhood, but also having lives that are not just about power, but also about insecurity. We know there’s an epidemic of loneliness particularly among young men right now in many countries. Young men who live in fear of being exposed as not being real men, but also are cut off not just from their own emotions and the emotions of those around them, but are relating to the world through their computer screen or their telephone. And not to say that that’s the cause of the problem, but this lack of connections, lack of connectivity, I think, is making young men in particular very susceptible to hate messaging and to misogynistic messaging and so forth.

AA: Can I throw in one more observation? Sometimes, as I’m thinking about men that I know, they’ve also sometimes had really painful experiences with women, like women being really mean. Or if they have a mom who is emotionally abusive, that is an example, like a formative experience, a core experience of a woman having power over him as a little boy and abusing that. So I’m really trying to get inside the heads of these men that may have thought, like, “What are you talking about? The people who have been meanest to me in my life have been women.” I can see how it would prohibit them from being able to see the structural issues if the personal experiences have been like, “I have felt powerless with my mom,” or “I felt powerless with my girlfriend,” or “my wife left me and it wasn’t fair.” Or heaven forbid this happens, it does happen though sometimes, being wrongfully accused of something by a woman, just feeling like “I actually truly have less power than women.” That does happen, and that’s a factor for a lot of people. Don’t you think Michael?

MK: Feminism and feminists never said women are the font of all perfection and niceness. Relationships are difficult. They can be totally screwed up. There are certainly many men who’ve gone through relationships and didn’t feel they were treated well. Sometimes it was their own doing, other times it was not. So I think that we do have to be real here and just say, yes, some men have had experiences in relationships or in their home. We know that boys are more likely to experience violence at the hands of a father, but many boys grew up experiencing it from their mother. It’s not good enough to say, “Well, maybe that mother was experiencing violence from her husband or boyfriend.” That’s not an excuse. Certainly there are many boys who become men who experience violence at the hands of women as well as men, of course, and that can lead to some real confusion. It can lead to hatred, it can lead to blaming all women for their problems.

I think with all these things, it’s what we do with those experiences of trauma or of hurt or of pain. And this is where the problem comes in. Do we learn to process the hurt and process the feelings to get support, whether it’s professional support or support from friends, or do we just stew on them? And here’s the problem we get if we’ve taught men from a young age, you know, “Don’t show feelings, you’re tough. You just tough it out” and so forth, men aren’t going to get help. Men don’t go to doctors as much, we don’t go to therapists as much as women do. And strangely, we pay a price for that. Men are more likely to be addicted to alcohol and other drugs, we’re more likely to take our lives by suicide, we’re more likely to engage in risk-taking behavior to prove ourselves and numb our pain. So there’s a real consequence to this pressure to be a real man, to fit into the so-called man box. So yes, men have these experiences with women and with men. The question is, what do we do with those experiences? And if we can’t find good ways to process those emotions, to deal with them, to let go of them, we’re doomed to be trapped by them.

AA: So how do people help men? And I do care about this a lot. I think it’s really important philosophically and personally. I have a son who’s growing up in this world, I have nephews that I adore, I care deeply about all human beings and men’s emotional and physical and social health too. So how do we help men face those challenges and heal from that pain?

MK: Well, I think there are several things. One is that, just like I said, that I as a man should be listening to the voices of women, I think we need to listen to the voices of men. Now, I don’t mean listen to the abuse. If a woman or a man is in a relationship with an abusive man who’s using what we now call coercive control, no, I am not saying, “Stick around, be supportive. He’s having a hard time, he had a hard childhood.” No way. Those are situations where I just say to that person, “Get out of there. Protect yourself, get support, go to the police, whatever it’s going to take.” But day in, day out, if we know, as we do know, there are a lot of men who are really hurting, we need an authentic discussion with boys and men about our experiences as men. So we have to create safe spaces. And one of the things I say, I’m going to reach back here and pull out one of my good books, one of the things I say in my Male Ally Handbook, which is really focused around building better workplaces for quality and change, just a little skinny little book. One of the things that we talk about in here is that acting as an ally, in this case at work, but it could be in the community, is building a community of allies. It’s not about, you know, “I’m going to be the male hero. I’m going to rush in there and save women” or whatever you’re doing. But to build that support community.

For example, at the workplace, to speak about these issues we’re talking about, whether it’s about violence against women or the promotion of women at work, or women’s rights overall, to speak to the other men about it and to try to find others who agree and to get together to maybe form a group. One thing to do is to take a page from the women’s movement, which began to form groups of women to talk about these issues. And they’re called consciousness raising groups or support groups. And you know if you’re at an auto plant you’re not going to form a consciousness raising group, but you might form a male ally group. And it’s not only supporting women, but supporting other men who are concerned about sexual harassment at work or parental leave or whatever the issues may be. So that’s one way.

The other way is in our schools. We have to do a much better job of bringing these issues of diversity into our schools, and sadly, the opposite is happening. We need sexuality education, not just sex ed that does plumbing and diseases, but sexuality education that talks about relationships, that talks about consent, that talks about love, that talks about pleasure, and that does acknowledge different ways that different people experience the world and their bodies and each other and who we’re attracted to or not. We need much more affirmative, open, positive ways of dealing with human beings. And we have to bring those into school. We have to bring into our schools discussions around computer literacy, internet literacy, so that boys aren’t being attracted to this absolute crap that’s being peddled at them, so that they can learn to break down the myths of what they’re seeing. But what’s key here is to set up situations of safety so that boys or men realize they’re not alone. Let me tell you what often happens and the way I do it. Yes, in my writings and my books I tell personal stories. It’s not that my stories are so– you know, some of them are pretty good, actually.

AA: They’re pretty good.

MK: It’s just that I want to tell stories, within a book or when I’m speaking, to hold up a mirror to men to say, “I want you to see yourself in what I’m saying.” Even if we’ve had different experiences and different lives, there are things in common. I use a lot of humor, or, as my wife would say, I try to use humor. And here’s what often happens. I’ll be invited to speak in a community, in a company, conference in a school or university, and I’ll start speaking. People in the audience, particularly men in the audience, will say, “Oh, he’s here to talk about women’s rights. I’m going to be crapped on for the next hour.” And those men are sitting leaning way back in their chairs. They just know it’s going to be awful, but they have to be there. An awful experience, but they have to be there. Instead, they hear me talking about the impossibility of living up to the expectations that have been placed on us. I talk with care, with humor about not just things I’ve experienced, but things that I hear from other men. I talk about the ways that we experience pain in our lives, and I watch those men, they’re my barometers. I watch as they start leaning forward, and then very carefully so their buddy doesn’t notice, they start nodding.

And I realize that what’s happening is that for some of them, for the first time in their whole life, they’re hearing, or in a case of reading, that they’re not alone. They’re not the only one who wants connection and wants love in their life, and wants joy in their life, and doesn’t want to have to be the tough guy. It’s starting a conversation. I love it at the end of these talks, sometimes some men or boys will walk by the front where I’m standing and they’ll just, without breaking their stride, they’ll go, “Great talk.” Because there’s still fear there about, you know, what will the other boys or men say? But it’s just an example. The other thing I would say on that is to encourage people to rely on their own strengths and abilities. I remember a number of years ago, my wife and I had a place in the country, an old farmhouse, and a neighbor came to me, this 75, 80-year-old neighbor, a farmer, I think with a grade four education. And he knew the work I did and he said, “Michael, I need you to help me. I just found out that one of my friends has been abusing his wife. What should I say?” And I thought this: “I’ve got my PhD, I’ve got my books and my big vocabulary and I’ve got this and that. But who’s going to be more effective in figuring out what to say to this man? Me or this man’s peer, the fellow talking to me?” And it was clear, it was obvious. And I said, “Jack, I think you’ve got the answer. You know what to say. Here are some ideas, but ultimately you are the one who’s going to be able to connect with that person.”

So this is what I say, that certainly when it comes to abuse, men have got to learn to, with care, thoughtfulness, but also with real strength, challenge those around us, whether it’s our fathers, our brothers, our sons, our friends at work. To say, “Whatever you just said or what you’re doing, I don’t accept it. It’s just not right.” And not to say it as, “That joke would offend some of the women working here.” To say, “No, that joke offends me. I don’t want to hear that in my workplace.” Whether it’s a racist joke, a sexist joke, a homophobic joke. Don’t put it on someone else. Just say, “That offends me.” Take responsibility. It is totally scary to do that the first time, let me tell you. But once we begin to do it, we find out that there are others around who agree and we have to find our own style. I don’t do too many workshops anymore, but when I was doing a lot of training, we sometimes practiced, how do you answer the difficult questions? How do you respond to a certain situation you hear? Practice your response, because we each have our own style. For some people it’s to use humor, some you just go right at them. Sometimes you can’t say anything because it’s your supervisor, so you get help from HR or from another supervisor or from a friend. But figure out your style and what resources you have. The main thing is, and this is what I say, the basic message in the Male Ally Handbook is that being an ally is not what I think, it is what I do. It is my capacity to take action, whatever the action might be. And I don’t mean action so I feel like I’m the hero, but action to make a real difference based on care, not just for those I’m in solidarity with, but care for those I’m challenging.

AA: Hi everyone, I hope you’re enjoying this fascinating conversation and I’ll let you get back to it in just a moment. But first, I have a question for you. Have you noticed that Breaking Down Patriarchy is totally ad-free? That’s really rare for a podcast, and our team is determined to keep it that way, sharing deep conversations and critical information about patriarchy without charging you a dime or trying to sell you a thing. But we need your help. I know what you’re thinking, and don’t worry, I’m still not going to ask you for money, although we do accept donations if you’d like to support us that way. But no, what I’m here to ask of you is to help us get the word out about this incredible ad-free podcast. If you’ll do just three things really quickly, it would be a huge help. First, like and follow the show. Second, leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. And third, recommend the podcast to a friend. These little things really do make a huge difference and they’re the easiest, most actionable ways that you can support this project. Thank you so much. And now let’s get back to the show.

I think it would be especially effective for these men who are not feeling empowered, perhaps feeling a lot of pain in their lives and so they are vulnerable to being pulled into this toxic masculine kind of manosphere on the internet with these very, very problematic and harmful figures that pull men in and make them feel strong again and make them feel powerful, right? In order to try to reach that demographic and save them from the clutches of the Andrew Tates of the world, I’m thinking that in many ways the most effective people to reach men in that situation are other men, right? Like you said about the man who is abusing his wife, the most effective person to reach his heart is going to be his own friend because he knows that that friend cares about him and knows him as a whole human being. So men need to speak up. I love how you said, too, that it doesn’t matter that much what you know if you don’t do anything about it. So what can women do? Maybe women family members, or even a woman educator like me that’s putting work out into the world. What are some ways that are more effective and less effective for women to talk to men, to try to help the men, but also to help the men become allies and care about women’s rights too?

Just say, “That offends me.” Take responsibility.

MK: Can I back up for one second? When we’re talking about so many men feeling powerless and that yes, it’s about our expectations of manhood, it’s also about our social reality. We’re living in a period of growing inequality where we have a few people who are becoming absurdly not just rich, but rich and powerful. And more and more, the middle has disappeared. The thing that so many men and women assumed would be the course of their life, it’s just vanishing away. People should feel empowered, they should feel powerful. Unfortunately, the whole society is ripping power away from people. And what that does is set people to look for, grabbing on this ephemera of power. I will have power as a white person if I have more power than someone of another color, and as a man or a woman, on and on. And what I think we need to do is to take a really holistic response and say that we need to challenge the growing inequality in society, which is not just around talking about these gender issues. It means things like turning things around in terms of the marginalization of trade unions. We’ve got to turn things around in terms of social programs. We’ve got to fight for universal health access, this big agenda to allow people healthier, happier, stronger lives. So this becomes a big picture and not just something that we’re talking about as this issue versus that issue. These things all come together. So what can women do, you’re asking, in terms of engaging men. I think there’s a number of things.

One is to challenge the men around them. A campaign that I co-founded decades ago now, called the White Ribbon Campaign, which worked to engage men to speak out against violence against women that had spread to about 90 countries that’s without any budget, it was an idea that spread, it started because some women challenged a couple of men. So one thing is to challenge men, whether in your life, family members, a work partner, to say, “You know, Michael, it’s really important to me that you speak out” or “You know how at that dinner we just went to Bob was going on about such and such, I thought I was the only one that was saying anything. Michael, I need you to say something.” I think that challenge is really important, and to say to men not “Why didn’t you say anything?” but “I need you to say something.” If you haven’t spoken up before, this is your chance to make a difference. I think that’s it.

In our relationships it’s really important to have that challenge for equality. That sometimes means very practical things. If we want to, and as we should be, dividing our housework and parenting 50/50, sometimes it takes an audit in the home to figure out, “You spend how many hours doing this a week.” It’s miserable. If you happen to be someone who enjoys a glass of wine, make sure you grab some lubrication for this exercise. It’s tough. It’s tough, but taking responsibility to build equality within our relationships is really important. So the challenge has to be there. But also saying to men, you know, men still have power and control in the world. And unless you’re speaking out in favor of different forms of rights, including women’s rights, it’s not going to happen. There is going to be too much pushback against it. So men, we need you. And that’s part of the steer to the Male Ally Handbook and my other writings. My book The Time Has Come: Why Men Must Join the Gender Equality Revolution, which is coming out now in paperback, finally, I’m happy to say, has been encouraged by women who said, “Michael, we can talk all we want, but we really need men’s voices speaking out.”

AA: Yeah, for sure. Let’s continue this conversation about men’s violence against women, because that was also something I was going to ask you about and the White Ribbon initiative that was started. I actually want to ask a foundational question that you write about a lot in the book. I know your answer to this, but I was very interested in it. One foundational question is whether men are biologically, naturally just violent beings. Because gender-based violence, men’s violence against other men, against all people, has been a problem throughout time and no area of the world has been safe from it. It’s always been an issue. So are men just more violent? How should we view that?

MK: I get so angry when you ask that question– No. Anyway, I think a lot of people assume that humans in general, men in particular, are prone to violence. Here’s the reality. First of all, humans, unlike some animals, do have the biological capacity to be violent against our own species. Not all species of animals do. We, sadly, are one species that has that capacity. That is true. The thing is, most of us, most of the time, don’t use violence in our lives. Even that man who was using violence in the home, he didn’t attack anyone at work, most likely, or on the way home. He is selectively choosing to use violence against certain targets. And this begins to tell us something that this isn’t just some sort of biological thing that’s just happening. I mean, biologically we have to drink and we have to breathe, so you can’t control whether you breathe or not. Well, you can try, but it won’t last long. You just do it. With violence, there is control there. Even when people say, “I’m out of control,” take it with a grain of salt. Here’s the other thing. We have actually good anthropological evidence that tells us that we haven’t had violence in all human societies. And where this evidence comes from, it’s fascinating. Anthropologists over the past 150 years observed many so-called tribal societies. Some of this research was good and some was not so good. But what they discovered, and some sociologists and anthropologists over recent years sifted through this data from many societies, and what this data showed is that just in the societies observed over the past 150 years, these tribal societies, they found that just as many that had violence against women, violence among men, violence against children, just as many with the violence as those with little or no violence. Human possibility, but it wasn’t inevitable.

So then they said, what distinguished the societies with the violence from those with little or no violence? And what they found out was this: in each and every case, the societies with violence were societies based on what we call patriarchy, men’s power, and the societies with little or no violence were societies based on a high degree of equality between women and men. In other words, the origin of violence, yes, there’s a biological substrate to it, but what brings it to adults, in particular, as opposed to a baby who’s just biting or scratching. But for an adult, it hinges on a society that’s based on inequality and based on violence. And remember what I said, that a patriarchal society, I don’t have to tell you this given the work that you do, so let me just say to a pedestrian member that a patriarchal society is one of both men’s power of women and the power of some men over others, but also the attempt to have power of humans over nature. And we can see what’s happening now with that. It gets into a whole new topic, but that’s there.

AA: But they’re all connected. They are all connected. And one thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot too, as I observe people in my own life, but also I’ve been reading about it, is how patriarchal structures enable men to not develop tools to deal with feelings of anger. Like you said, it puts men in a box where they’re not in touch with their own emotions, they’re not able to get help. But also men who do have more of a propensity toward violent anger, oftentimes patriarchy trains all of the people around them to do all the work to not confront that man. So he can grow up his whole life never feeling consequences for that anger. And I think that happens a lot in patriarchal societies, that we don’t require men to develop those tools of like, “What do I do when I do feel super angry? Well, I certainly couldn’t just scream at everybody or hit somebody.” You know what I mean? So I think that’s also part of this, that in an egalitarian society, little boys look around their whole life as they grow up and they just learn “Well, I certainly couldn’t act like that. I would need to learn how to talk and how to deal with feelings in healthy ways.” Yes, go ahead.

MK: And that goes back to the importance of change on so many levels. Here’s one example. One of the things that we know is that the more that men take on equal responsibility as fathers, as parents, we’re going to see a reduction in the use of violence. Why? The main skill that you need to look after a baby or a young child is empathy. Changing diapers, feeding, those are easy to learn. All humans have the capacity for empathy. Empathy is our ability to feel what someone else feels. We need that in order to look after children because they can’t talk. And even when they learn to talk, they’re not very good at expressing their feelings. So to be a parent, you have to develop incredible empathy. If you have more empathy, you’re less likely to use violence because you can feel the pain you’re causing. So if generation to generation men are taking on our share of parenting, what it will mean, and that’s part of equality, what it will mean is that we’ll see less violence because there will be greater empathy. So you can see how all these things get connected. You say, “Well, what’s the solution?” Part of the solution to the problem of violence is a transformation of fatherhood. Of men not just helping out or babysitting, oh boy, I used to hate when someone would say that when I was looking after my kids. But just being an equal parent. And to do that, you need changes in the workplace and in society. I mean, think of it. Of all the countries in the world, there are three countries that don’t have federally mandated parental leave. They are Papua New Guinea, the tiny African country Lesotho, and the United States.

My goodness. So we can’t just say to individual men, “You should be taking time off.” I remember when I was in the midst of writing The Time Has Come, I was walking along and I saw some guy working in someone’s garden, and I was pushing a stroller because I had my grandkids, and we started talking about kids because he had just had a kid. And I said, “Did you take some time off?” And he just looked at me like, “Well, I took off a day, but I wouldn’t get paid.” So we can’t just say to individual men, “Do this, do that,” but we need the social support, we need the legislative changes, we need the changes in training in companies and policies. So you can see how these agendas to build equality, we’re not just foisting it on the individual, but we’re saying that we need a social responsibility to bring about change. And there’s a cascading effect. There’s a cascading effect. We’re bringing parental leave at the federal level, the state level, at the company level, and that leads to more men participating more as parents, which leads to reduction of violence. And it also leads to the reduction of violence because it leads to greater pay equality between women and men, and these women become less trapped in abuse. You can see all these things start knitting together in fantastic ways.

AA: This has actually been a unique epiphany in all of the reading and conversations that I’ve had in the last few years, all of this interconnectedness. But one specific connection, I’ve always thought that of course there needs to be a more equitable division of labor at home, and that benefits the woman specifically and also I’ve thought of how it benefits the man. Even watching my own husband and how much joy he has gotten from being so attached to the children, just witnessing that in our lives, it’s this immense source of joy for him and for our family. But I had never thought about, like, I do hear people say, “Well, men are just going to be more violent because of testosterone.” And I’ve read studies, when you were talking about men caring for babies and developing empathy, your hormone levels change, actually. No matter the gender, whatever gender of person is taking care of an infant, testing their hormone levels afterwards, and I don’t remember because I’m not an endocrinologist, but it changes hormone levels. So the argument that men just are more violent by nature, if men are more violent, and the statistics show that they do behave more violently, even the hormonal levels can be changed by our behavior, by our society. So if men are able to take care of their babies, that could change their biology, actually.

MK: It’s incredible stuff. And it just shows that our ideas of these two fixed categories, male and female, it’s not so simple. There’s a certain group in the middle that has some characteristics of the other sex. But we’re not opposite sexes. 99.8% of our bodies are exactly the same. There are some small– well, they’re not small if you’re a real man. There are some differences which are absolutely wonderful, but we exaggerate the differences and lose sight of the commonalities. But we also lose sight of the malleability, as you mentioned there, about hormones and so on. It’s pretty incredible when you start, even as non-scientists who read that stuff. In both Men and the Gender Equality Revolution and in my book The Time Has Come, I have the same chapter on fatherhood. It has some of that research cited in it, and it talks about the challenge and the hard work of becoming an equal parent, but also the total joy and the benefits for women, the benefits for men, and the benefits for children. The evidence is so clear.

And there are also benefits for leadership. I remember one of the stories I think I tell in there is that I was giving a talk in Singapore– I’m a lucky guy, my work has taken me to some amazing places. And I’m giving a talk to a group of bankers. Singapore is this international banking center, so these are the heads of some of the big European banks and US banks, the heads for all of Asia are there. This one British guy, he’s a big deal in the banking world, he gets up and I’m speaking particularly about fatherhood at this particular event. And he says, “Here’s what I’ve been doing. In my family, I’m the one now who gets the kids up in the morning and I make them breakfast and I drive them to school and I get to work around 9:30.” And this whole room of bankers laughs because, you know, bankers’ hours, you don’t start at 9:30. So they laugh and he says, “But hang on a second. This is really important to my wife, who’s at a stage of her career where she has to get to work early.” And people go, “Oh, okay, fine. Support your wife.” And then he says, “And it has also been good for my kids because they actually know me and get to spend time with me in a way that I didn’t get to with my dad.” And they go, “Yeah, okay, I get that.” And then he said, “It’s been good for me as a leader.” And they all start scratching their heads and say, “What do you mean it’s been good for you as a leader?” He said, “Well, to be a good parent, you have to listen, you have to become a good listener.” And he said, “This has taught me to become a better listener, which has made me a better leader because I can listen both to what people who report to me are saying, but also listen to what they’re not saying and to understand things better.” He said, “This has made me a much better leader.”

So, we think there are winners and losers if you fight for equality, which is not true. This is what is so amazing about feminism. This is what’s so amazing about fighting for equal rights for all, for challenging forms of discrimination. It’s not about some people losing out and others gaining. It’s pushing us all up. It’s raising the level for all of us. And I think that’s good news. It also points to why our work, I think, ultimately has to be based on love. It has to be based on connection. I don’t normally quote the scripture, but the word is love. And the more I think we can live by that precept and not by, you know, “the word is I’m better than you,” or “you’re wrong for that,” or “I hate you because of.” But to really start with an assumption and a practice and a dedication to fostering connection and love and mutual support and mutual respect, it pushes all of us higher and higher.

we’re not opposite sexes. 99.8% of our bodies are exactly the same

AA: Well, that really comes through in all of your work, everything I’ve ever read from you and speaking to you during both of these episodes. I’m so inspired by that and I think it’s really the only approach that’s going to work. Because at the end of the day, these are big systems, but big systems are made of individual people, right? And people need to feel that safety and that love and like, listen, we’re all on the same team. We want everybody to be healthy. We want people to flourish. So having that energy of love is really the only thing that’s going to change hearts and minds and enable us to move forward together.

MK: That’s so true, and I think it’s particularly true now where there’s so much hate being mobilized around us. And yes, we have to change structures– it’s not whether you change the structure or change people, it all goes together. And even though I’ve tried to bring these messages in my nonfiction writing, I also try to do it in my fiction writing. For example, I just recently under a pseudonym wrote this young adult novel about this teenage girl who happens to discover that there are centaurs living on the horse farm where she’s working. She then has to struggle both to save these centaurs but also to save her community, so to try to find ways to communicate. And in my mysteries, my series set in Washington, DC 10 years in the future, The Last Exit and The Last Resort, again, talking about our ability as citizens to engage those around us to, you know, we use the word struggle, but to struggle for a better future for everyone.

AA: Mm-hmm. I love that you write fiction as well, and that they have these themes in there. I think I’ve said this before, but as I think of the worldview that I developed along the course of my life as an adult, I think it was influenced probably more than I even know by the books that I read as a kid. The books that I read as a middle schooler and as a high schooler, too, that influenced me. Whether it’s historical fiction that’s set in Nazi Germany or it’s historical fiction set in the Middle East. I remember one that I read, and I don’t think I had any Muslim friends at the age that I read it, and I was like, “Whoa.” It opened up this world. Talk about empathy, right? It’s a way of building empathy to see from a different person’s point of view. And I’m sure that’s not the only reason why you write these books, is to embed a social message in there to get to the minds of the young readers, but it is one effect that reading a wide variety of books expands our worldview and helps us see humanity with more empathy.

MK: I think that’s really true. I write both, in this case, a young adult book, but my mysteries for adults to entertain. If I wanted to lecture I would give a talk or write my nonfiction. I want to write stories that are page-turning and fun, and you going “That was so much fun.” But I also feel like let’s be real, you know? Yes, on one level you’re escaping, but let’s escape into a world that really allows us to think about our lives and think about things maybe a bit differently. To learn from it at the same time as escaping. And what you point out is one more reason why it’s so sad when we see this book banning going on. Because reading that book from the Middle East by someone who’s a Muslim didn’t make you a Muslim, it just made you aware of the world. It made you appreciative of differences. And the thing is, different cultures look at things differently, just like different languages. For anyone lucky enough to know a second language, you know that there are certain things you say better in one language than the other. It’s because words cut up reality in different ways. So by reading broadly, we see the world in its complexities and beauties. So we want to welcome children into that sort of thinking and being creative and learning critical skills. And it’s so sad when you see parents pressing and pushing their schools and school boards to actually cut what kids are exposed to, rather than saying, “Gosh, the more they get exposed to more things, the smarter they’ll be, the more aware they’ll be, the better citizens they’ll be, the better leaders they’ll be, the more successful they’ll be in their jobs.” We’re pushing people in the opposite direction, and that is so sad.

AA: Mm-hmm. I agree. Well, I am so sad that this conversation is almost over. I’ve learned so much from you and I so value and appreciate your work and your point of view. I’d love it if we could end the episode by sharing a couple of action items. That’s the theme of this season of the podcast. There is a lot in the world that is beyond our control, sadly, but there are always things that we can do. So what would be a couple of bullet points of things that listeners could do right now to make a change toward gender equality?

MK: There are several things that I would encourage listeners to do to really help build greater gender quality. One is to speak out in our families and our workplaces, to go to those places that might feel a bit uncomfortable, but learn to, find your words to speak out for the rights of all people. If you’re a man, learn to listen. Learn to listen without getting defensive, without having to prove that you’re different. You don’t have to agree with everything you hear, but just listen with respect. For all of us these days, to develop our listening skills, to try to learn to hear people’s pain, there’s a lot of it coming out, sometimes in very ugly ways, and to try to get beyond the ugliness and learn to listen. And listen, if not with respect to all the ideas you’re hearing, but respect for the humanity of that person you’re listening to.

Support women’s rights groups in your community. Many of them are under attack in many different ways. They’re going to have increased funding problems. Supporting them by giving money and donations, by doing fundraising, by coming to their activities is really important. To think about the choices you’re making. Next time you go to the ballot box, maybe not immediately right now, but to really be thinking about the consequences beyond this small issue that you believe in or that even that big issue you believe in. But for the totality of the wellbeing. What sorts of leaders are we supporting? Are we supporting leaders who are spiriting hatred or ones that are trying to foster connection? Not to say that they’re perfect or have all the answers either. I think part of it is just making that individual commitment to take action, to learn more. Go through your podcast episodes, they’re absolutely amazing. There’s so much to learn there. To learn more, to study, to realize that none of us have all the answers. There’s so much to learn about. So to keep learning, to keep listening, to keep thinking, keep challenging ourselves. I did this and it’s not that I’m going to, you know, flagellate myself because of what I did or said, but to learn from that and try to, if we need to make amends, make amends.

To take action, but also to celebrate where possible. If in our work we’ve been doing a better job at hiring and investing in women or supporting parents, celebrate that to say, “Look what a good job we’re doing.” If you’re in a relationship with somebody and you have kids and you’ve done a pretty good job of dividing up the work equally, let people know, celebrate that. Raise a glass, toast, I don’t know, whatever it takes. But to really celebrate our accomplishments. I think we should be proud of where we bring in change. I think we are in for some tough times ahead. I think we should be serious about that and recognize that and be supportive of each other, which means one big thing. The type of internal nastiness that can go on in progressive movements and among those who support change, I think is so destructive. “I’m going to criticize you because, oh my goodness, I see a book on your bookshelf behind you, Amy, that I think is this and that, and how could you support that?” Come on. Just be more thoughtful about how we go after those who we agree with on many things and learn to support each other.

AA: Same team. Yeah, that’s wonderful. Yes, yes, yes. Well, that was wonderful. I appreciate all of those suggestions, and particularly thank you for your reminder to celebrate the wins and celebrate the progress too, because I think that’s so important in our work to have that optimism and to have gratitude and to feel proud of ourselves when we do make changes. Thank you for that reminder.

MK: Absolutely. The progress here and around the world. At the time we’re talking, a few days ago in Afghanistan, the Taliban was about to bring in a new law that further restricts women’s education. The men’s national cricket team came up publicly and criticized their government. It takes enormous courage to do something like that. So I think we’re seeing around the world, in spite of a million bad things happening, we’re also seeing in the case of men, an allyship, more and more men who are coming forward and speaking out for women’s rights. I am so excited by that. I’m so excited and so proud of the men everywhere who are supporting those rights.

AA: Wonderful. Well, Michael Kaufman, thank you again so much for being here, and we will list the complete list of all of the work that you’ve written and done on our website, and also we’ll be featuring it on our social media. So listeners, make sure to check that out and check out Michael’s work. Thanks again, Michael.

MK: Lovely speaking with you. What you’re doing is just amazing, so thank you so much.

We exist not only as men with power and patriarchy,

but also as humans.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!