“Look at the different stories and see which one really makes the most sense.”

Amy is joined by Dr. Elora Shehabuddin to discuss her book, Sisters in the Mirror: A History of Muslim Women and the Global Politics of Feminism, exploring historical and contemporary misunderstandings of Muslim women, how Western and Muslim feminisms influence one another, and what each of us can do to live as better allies.

Our Guest

Dr. Elora Shehabuddin

Dr. Elora Shehabuddin is a professor of gender and women’s studies and global studies at UC Berkeley. Previously, she was a professor of transnational Asian studies and core faculty in the Center for Study of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Rice University. Before that, she was an assistant professor of women’s studies and political science at UC Irvine. She received her BA in social studies from Harvard and her PhD in politics from Princeton. Shehabuddin is the author of many, many articles and multiple books, including the award-winning Sisters in the Mirror: A History of Muslin Women and the Politics of Global Feminism, which was published in 2021.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: When I was a little girl in Seattle, our across-the-street neighbors were a South Asian Muslim family named the Chaudhrys. They were our emergency contacts, and I remember a few times coming home from school to find that my mom wasn’t home, so I just trotted across the street where Mrs. Chaudhry would have cookies and lemonade for me. And their teenage daughters were my first babysitters. I remember that when we moved to Denver from Seattle, they came over to say goodbye to our family and we all cried because they were like our family. Later, in college, I studied abroad for five months in Palestine, Jordan, and Egypt, and I took many classes on Islamic religion and history. Throughout my adult life, I’ve had many, many Muslim friends for whom I have a very strong sense of sisterhood and kinship, based partly on a lot of similarities in our faith traditions.

But it has only been in the past few years that I’ve developed a feminist consciousness of my own in my own context. Now I so badly wish that I could go back and talk with the Chaudhry women and with the women I knew in the Near East because I would have so many more questions for them now. So you can imagine that when I saw the book titled Sisters in the Mirror: A History of Muslim Women and the Global Politics of Feminism, I bought it immediately. I was delighted to find that it was not only an incredibly informative work of scholarship, it was also so easy to read and so relatable. I highly recommend this book to listeners who are interested in understanding their Muslim sisters better, and I am so honored to welcome to the podcast the author of this book, Dr. Elora Shehabuddin. Welcome, Elora!

Dr. Elora Shehabuddin: Thank you so much! Thank you for having me, Amy.

AA: I’m so excited for this conversation. Again, I just have to tell you how much I enjoyed the book. I’m willing to put myself through very dense academic writing, I do that all the time. I’m in a PhD program and some of the books that I’ve read on the podcast are dense. And yours was just riveting, it was a page-turner. I couldn’t wait to read it.

ES: Oh my goodness! Thank you so, so much.

AA: Thank you for your research and thank you for writing in a way that was just a joy to read. I’ll start out, as I always do on the podcast, by introducing you professionally, and then we’ll have you tell your story yourself afterwards.

Dr. Elora Shehabuddin is a professor of gender and women’s studies and global studies at UC Berkeley. Prior to moving to Berkeley in 2022, she was professor of transnational Asian studies and core faculty in the Center for Study of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Rice University. Before that, she was an assistant professor of women’s studies and political science at UC Irvine. She received her BA in social studies from Harvard and her PhD in politics from Princeton. She is the author of many, many articles and multiple books, including the award-winning Sisters in the Mirror: A History of Muslim Women and the Global Politics of Feminism, which was published in 2021 and which, like I mentioned, we’ll be discussing today. And, exciting news, the paperback is available! Is it available quite yet, Elora?

ES: I think it is, they said early March. So yeah, I think so.

AA: Okay, fabulous. I had the hardcover and it was wonderful, but now the paperback is out. Again, welcome. I wonder if you could start us off by telling us a little bit more about you, where you’re from, and the factors in your personal life that brought you to the work that you do today.

ES: Of course, thank you. I consider myself to be from Bangladesh, even though I’ve been in the US for many years now. The interesting part about that is that growing up, I spent very little time in Bangladesh. My father’s job took us all over, so I was actually born in what was then West Pakistan. East and West Pakistan were one country until 1971, when East Pakistan became Bangladesh after a war of independence. So I was born in what was then West Pakistan. My parents are both from East Pakistan and Bangladesh, and because of my father’s job, we moved around. So I actually grew up in India, France, Lebanon, a few years in Bangladesh, and England. I finished high school when my parents were in Poland, but I had to go to school in England because there were no English schools in the 1980s in Poland beyond the eighth grade. And then I came to the US for college.

My family background is Muslim, from what is now Bangladesh, so Bengali Muslim. I’m the oldest of four sisters, and they’re always there for me, but no brothers. And then I came to the US for college and I studied the special major at Harvard called social studies, where you draw on all the different social sciences. You put together your own course of study, even though there are some required courses you do every year, and then you have to write a senior thesis. And I loved the process of writing a senior thesis. I said, “Okay, I don’t see myself doing a nine-to-five job. I’ll just go to grad school,” even though that hadn’t necessarily been the plan before. And I like my life choice in terms of the professional path, I like doing research, reading, and writing. So that’s where it ended up. I never got a formal degree of any kind in women’s studies, it was around even when I was in college, but I focused on women and gender issues, even for my senior thesis. And then I continued to do that in graduate school. I just never got around to doing anything formal like a diploma or a certificate in it.

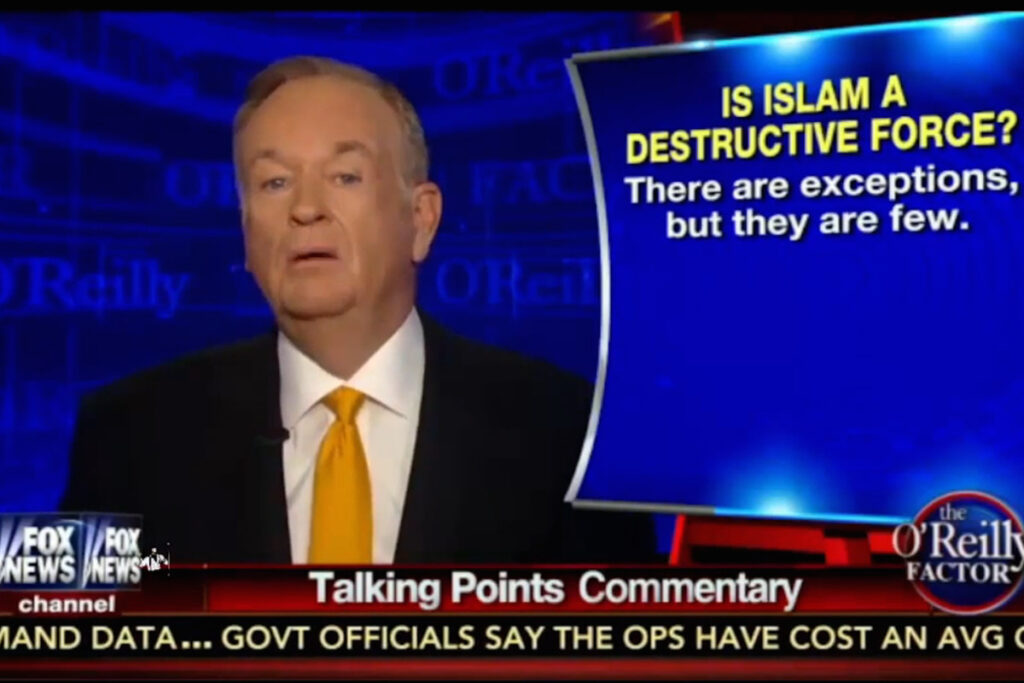

So, right after 9/11 there was a lot of attention on Afghan women, on women and the blue burqas, and many people have written about this and how Laura Bush’s address was the first time that a first lady addressed the nation through a radio address. Laura Bush, as the Americans were going into Afghanistan to find Al Qaeda, the way she pitched it was that it was to save the women of Afghanistan. After the Americans go in, they will be able to finally sing and dance and get an education, et cetera, and throw off those blue burqas. So that was at the level of the government, and there were a lot of Muslim and ex-Muslim, very prominently ex-Muslim, women writing in the US at the time, saying, “Yes, we have to go find these terrorists. Islam is a terrible religion for women and we need to save these women.” So this idea that Muslim women were oppressed became very commonplace in a new way post-September 2001. And those women in particular, I have in mind Irshad Manji and Ayaan Hirsi Ali. Those were the two most prominent ones. They were celebrated in The New York Times as, you know, “these are the true feminists of Islam, let’s celebrate what they’re doing because they’re finally speaking out against the injustices of Islam.”

So that’s when I and many others sort of sat back and thought about this. For me, my interest was, surely, of course there are problems in Muslim communities facing Muslim women, just as there are problems facing women in all communities. Surely these are not the first women to have spoken up about this. I’d heard stories, I knew of people, but I wanted to do a more in-depth study. I decided to look in a systematic and academic way how feminists, and feminism is a relatively recent term, so how men and women in Muslim communities had spoken out about problems facing women in Muslim societies, without colluding with the colonial power, or in this case post-9/11 American power. How do you make these criticisms without necessarily falling into this trap of saying “all of Islam is terrible”? So I decided to do a more historical study to see how things had changed over time. But also, to look at it in relation to how feminism was evolving in the West at the same time in non-Muslim contexts.

I see it as a sort of historical depth and transnational breadth. So that’s how the project began. It was a much longer book and I had to fix it for what became the book, but that’s how it began. I started just reading stuff, but it’s way outside my historical comfort zone. And it was interesting, a lot of this work has been done by other people. I mean, I will not say that I discovered this author or that author, some I may have along the way, but there’s been a great deal of scholarship. What was interesting for me was to create this genealogy, drawing on the work that other people have done so brilliantly, but putting them in this longer history. People who write about the early 18th century just focus on that. So I wanted to see, okay, what happened before? What happened after? What happened a hundred years later? So, that’s where I saw myself coming in.

AA: I’m a sucker for a chronological timeline, so I loved it. I thought that it was so well done in that very sense of showing the context of what came before. And then some causal through lines, but it made so much sense. I wonder, as we dive into the book now, if you can set the stage by telling us about the population that you focus on in the book. It might be news to a lot of listeners that South Asian Muslims outnumber Muslims in the Arab world. Is that right?

ES: Oh yeah, absolutely. And Muslims in Southeast Asia are an even bigger population. It’s what we keep telling our students in class, that not all Arabs are Muslims and not all Muslims are Arabs. So we can start from there. I focus on the South Asian Muslim population partly as a way to add to the literature that’s out there on Muslims. Of course, there’s been scholarship on South Asian Muslims, but a lot of the scholarship on Muslims has been about the Arab world and the Middle East more generally, which would then include Turkey and Iran, which are not Arab. So I wanted to focus on using the language that I know best, Bengali. Using the Bengali language to understand and to get to material from that part of the world. Part of the argument is that there are so many Muslims there, so why aren’t we paying more attention to it? Part of it is the demographic argument, but also it’s just a very different history. If all our ideas about Muslim women are based on how things emerged historically in the Arab world, you’re missing out on many other things.

South Asia, Bengal specifically, is interesting because it was colonized by the English for almost two hundred years. Islam came to Bengal quite early but in a very different way, mostly through Sufi teachers. So it spread not by conquest but through these holy men who set up mosques and brought in communities. So the history of how it evolved is different, the way it evolved is different, and the interactions. For me what is important in every aspect of the book is who they were interacting with. Bengal has a very large Hindu community, and Buddhists and Christians. So in that sense, it’s obviously different from Arab Muslims, who don’t interact with Hindus and Buddhists on a regular basis, right? So for me, there are all these reasons, even beyond the demographic argument, for why to focus on Bengal. And as I said, I know Bengali, so that’s where I felt I could make a contribution. That’s the main argument for why there.

not all Arabs are Muslims and not all Muslims are Arabs

AA: Perfect. Well, let’s dive into the book. I have some specific questions for you. The first one is about a short quote that I’ll read. You write that “feminist movements in the West and in Muslim societies have developed in tandem rather than in isolation, even helping to construct one another.” That was a big a-ha moment for me. Can you tell us how feminist movements in the West and feminist movements in Muslim societies have constructed one another?

ES: I begin by saying how we tend to talk about these different feminist movements. One story is that feminism developed in the West and then spread to the rest of the world, right? Like sharing the good news of feminism, it begins here and then it goes everywhere and people then tweak it to suit their needs. And then the other story that we often hear is that, no, we’ve all had our indigenous feminism, our local versions of feminism. There’s been a Bengali feminism, a Malaysian feminism, a Russian feminism, etc., and these have all developed separately. What I’ve tried to do here is to show that that may be the case, but they’ve always been connected. By that I don’t mean that they’ve always cooperated and gotten along, absolutely not. That becomes very clear. I mean that it is in relationships of power between different countries. It cannot be that feminism in one place emerged in a vacuum, isolated from what’s happening elsewhere. So what I tried to do, the main contact that I pay attention to through all these periods, is ask what the power relation was between Britain, South Asia, and then after the second World War, the US, because it became much more powerful than Britain after the second World War.

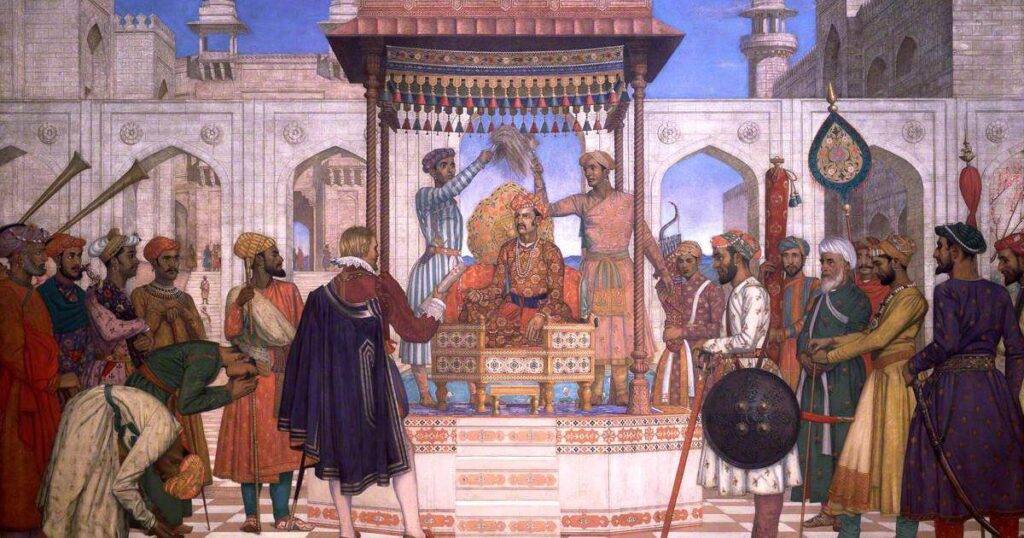

So, what is the power relation between Britain and South Asia? Initially, the British were actually in an almost inferior position. If you imagine the English Queen Elizabeth I and King James I, in the 16th and 17th centuries, sending emissaries to the court of the great Mughal emperor, saying, “Please give us permission to trade here and to set up factories.” So in a sense, they were the ones who were supplicants to the Mughal court, which did not cover all of India, but was still an enormous, awe-inspiring court. But in 1757, the British started controlling India politically. It started in Bengal and then spread to most of the rest of India, and the power dynamic switched. So I’m interested in seeing how ideas about women on the other side, I mean it’s very simplistic, but it’s easier to think about it as sides even though it’s much more complicated than that. But how ideas about women on the other side were shaped by this larger power relationship, which was unequal.

One of the things with inequality is that the more powerful side is aware of what’s happening on the other side, but is not as affected by it as the weaker side is. So by the time feminism becomes a thing, you know, in the past people thought “This is not fair but there’s not much we can do about it.” But by the late 19th century, in both the West and in the Muslim world, people were organizing, men and women were fighting to change things. But by then the West was very much in a position of dominance over most of these Muslim regions. So then they can say “they’re not as good of feminists as we are, because we know what feminism is.” So, colonialism, tied with this feminist arrogance, if you will, shapes how they think about the other side. And then on the other side, the way Muslims experience feminism is sometimes with the efforts to impose a Western kind of feminism on them. And because it’s often coming as the handmaiden of colonialism it’s rejected, because it’s seen as alien and not tied to local conditions and local demands. On the other side, it also means that when they are fighting for women’s rights, it’s very hard to separate it from the fight against colonialism. It becomes tied to anti-colonial nationalism, and then in other contexts, the fight against racism within the Americas, for example. So, feminism looks different and it also allows people on the Muslim side to say, “We don’t like the look of that. That’s not the kind of feminism we want,” just on the matter of the issues.

AA: Mm-hm. Yeah, that’s great. Okay. Let’s talk about a specific topic that was pretty consistent through the book that was so interesting to me, and that is the harem. If we go back to what you were just talking about in terms of these European powers coming into a great civilization that’s completely foreign to them, that they don’t really understand, and they observe these cultural practices and then they have their ideas about what they mean. Can you explain what a harem really was in its own context and how was it perceived in the West?

ES: A harem is basically the private quarters of a Muslim home, or any elite home in that part of the world, it wouldn’t necessarily have to be Muslim, but it had more rules associated with it when it was in a Muslim home. It’s a private quarters where women and children would spend most of their time. So if a man had to receive guests, there would be a separate area to do that, like a front room or a more public room. The fact that it’s only in elite homes or in the homes of the wealthy is important because most homes can’t afford to have all these separate areas. For travelers to the East to encounter this, in places like Syria or the Ottoman Empire, the men– it’s mostly male travelers who go or at least who leave us records. So the male European travelers going to these places went with this arrogance that we’re here to see. It’s sort of like travelers today. Americans will go and say, “What do you mean I can’t see everything that I want to see?”

So they expected to gain entrance, and when they weren’t allowed, at least in the elite homes, they sort of sat back and came up with fantastical ideas about what happens in this place that they’re not allowed to see. So they imagined that there’s a great deal of same-sex activity going on in there, that they were all lying around waiting for the master to come so that they could all have sex. And that they were all lying around naked, too. And you see that in a lot of the great art of the 19th century in the big museums. Like Turkish Women Bathing by Delacroix and all these people. These European artists have lots of big famous paintings of naked women sitting around. We know for a fact that no man would have been allowed in to see these places, so we know that this is their imagination. And for the painters themselves, I think most of the big ones didn’t actually travel, so even those paintings were based on writings by men who had never seen these places. So it’s like male fantasy on male fantasy on male fantasy.

In reality, these quarters were for the women and children of the household. Even boys would be there until they were old enough to hang out with adult men. That’s where they did their housework, that’s where they did their studying, and again, depending on the wealth of the house, that’s where they would read to one another. They would recite poetry and they would sew and do whatever. It was just a private space. And what’s interesting is that from the early 17th century, English writers like Mary Astell, who was called the first English feminist, a hundred years before Mary Wollstonecraft but not as well known, she wrote this text where she laid out a plan for an all female academy. She was a theologian, so she was interested in this all female place where women could devote themselves to studying and devote themselves to God and such things. Mary Montagu, who was the first English woman to actually travel to the Ottoman Empire and to actually gain access to the harem, the women’s private quarters, was really impressed with what she saw. She was really impressed and really surprised because she, too, had read all those male fantasies about what happens there. She thought it was so boring what they did, it was so mundane, in a sense. She had lots of good stories that many people have written about, and I draw on some of that for the book. But because the idea was so well entrenched in Europe and in England at the time, what Montagu said didn’t really make any dent in that idea. Astell is interesting because she had all these misconceptions about Muslim women, but she didn’t see the value of an all female space mapped on quite accurately to the private quarters that did exist for women in that part of the world.

AA: Yeah. So, so interesting. I wanted to bring up too, because you mentioned the Ottoman Empire, you write about how the Ottoman Empire was kind of a symbol or a stand-in for the entire Muslim world in the 17th and 18th centuries. And you wrote, and this made me so sad and it was really shocking to me, you wrote that in the 1699 dictionary, a “Turk” was described as “any cruel, hard-hearted man.” And the Oxford English Dictionary still defines “Turk” as “a cruel, rigorous, or tyrannical person, one who behaves barbarically or savagely.” Or, also, “a man who treats his wife harshly.” I did not know that!

ES: Just to be clear and to be a little fair to the Oxford English Dictionary, I think it’s one of the later meanings. I don’t remember if it said it’s obsolete, but you know there are one, two, three, four, several meanings, but it’s still there. You can actually find it. But yeah, the word “Turk” became synonymous with all these traits: tyrannical, treats their wife badly, et cetera, et cetera. So that in writings at the time, you find people using the term without having to explain it, and that’s the understood meaning of it. So if someone says, “Oh, you Turk,” they’re not necessarily saying you’re from the Ottoman Empire. They’re saying you’re a tyrannical man. You see this in Jane Eyre, you see this in a lot of the literature of the period.

AA: Yeah. I did not know those roots of Western Islamophobia are right there in that word, so that was really interesting. And this period of time, again, was so fascinating and eye-opening to me. These English people going to the East, congratulating themselves, and reminding women that they were much better men than those men in the East who had those harems, which again, you said they hadn’t even seen. They were using their imaginations about what that even meant. So I wanted to ask you how Western women used the notion of the harem and the “oppressed” Muslim woman in their feminism. You talked about Mary Astell, but then even Mary Wollstonecraft employed the trope of the seraglio or the harem to say, “Look, we’re so much better,” right? Can you talk about that a bit?

ES: Yeah. I talked about a few steps, I guess. The first is, as you said, the English men who go over there and then come back. One was William Biddulph, who went to Aleppo, which is now in present-day Syria. He went as a preacher and a tradesman, those jobs are combined somehow. And he comes back and writes a memoir of the trip, a travel log, and he says that English women have a great deal to learn from the women there who are so simple, stand up when their husband comes into the room and they kiss their hand. And I think his point was that English women should learn from the women over there and how simple they are and how subservient they are to their husbands. And then from that it followed that they should appreciate what they have because we could be like those men there. So William Biddulph, in his 1609 account as a preacher to the company of English merchants in Aleppo, expresses his hope that English women will read his book and realize how fortunate they are compared to women elsewhere.

The quote is: “Here in England, the wives may learn to love their husbands when they shall read in what slavery women live in other countries, and in what awe and subjection to their husbands, and what liberty and freedom they themselves enjoy.” He called Islam a “devilish religion” and said the men enjoy all these liberties and the women don’t, so English women could learn a thing or two and appreciate what they have here. He talked about the Muslim woman having to rise to greet her husband when he returns from a trip, and she bows herself to her husband and kisses his hand, and then, having offered him her own seat, stands so long as he is in presence. Such deference, Biddulph believed, was worthy of emulation. He goes on to say: “If the like order were in England, women would be much more faithful and dutiful to their husbands than many of them are.”

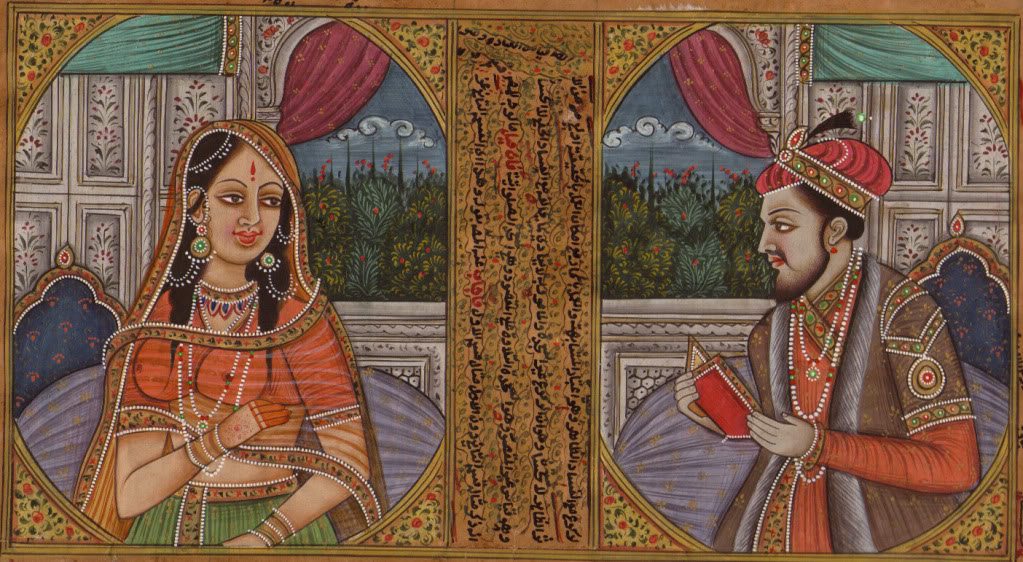

So, this is one take on women of the East. The other one I had in mind is Thomas Roe, who went to the Mughal court as an ambassador of King James I of England, who succeeded Queen Elizabeth I, as an emissary from King James and really from the East India Company, which has been described as one of the first multinational corporations in the world. He went there and was trying to get those trading privileges I mentioned earlier, from the Mughal emperor, Jahangir. But Jahangir, it turns out, was not the decision maker. It was his wife, Nur Jahan, who was behind and who didn’t interact with men she’s not related to. He knows that she is responsible for making the final decision to give him trading privileges or not. Roe is upset because here’s this woman who has the right to make this decision, and she’s a Muslim woman but this was not what he’d heard about Muslim women. They’re not supposed to be these decision makers.

It’s also weird because he was 22 when Queen Elizabeth died, so he was familiar with the idea of a female monarch. And Queen Elizabeth was a formidable character. But then when he went to India, he didn’t expect to find a powerful queen. So he’s upset that she surprises him in her behavior and he’s irritated that, you know, “I thought I would come and get these privileges and now all this lies in the hands of this woman who I can’t even see.” These are two images which show how men were dealing with the idea of the Muslim woman, and we’ve talked about the harem already.

Women like Mary Astell and Wollstonecraft, but even in between, they used the figure of the Muslim woman, and for me this is an example of how Muslim women figure in the global politics of feminism. It’s not that they were, as I said, working together or anything like that, but the idea of the Muslim woman was pretty important to the idea of feminism, as was slavery and other issues like that. But I only touch on that briefly. Others have written about that. Astell talks about ideas like that Muslim women have no souls. This is very central to how Wollstonecraft, Astell, and others thought about Muslim women, that they’re all concubines or even that whether they’re a wife or a concubine, they have no rights. So there’s one lady, Sarah Cowper, who left a 2,300 page journal about her married life to Sir William Cowper. And there’s a passage where she complains when he treats her badly, I think he complains about dinner or linens or something. And she says, “he’s treating me like an Eastern concubine.” So that’s an example, you know, it’s the way the word “Turk” took on a certain meaning. The word concubine took on a certain meaning. And what’s interesting is that you didn’t need to explain it, right? If you say concubines, “oh yeah, yeah, those Muslim women who are all concubines and have no rights within their household.” So Astell uses several terms like this, and Cowper is another example.

And then Wollstonecraft, who is called the foremother of Anglo-American feminism, does it very clearly numerous times. And again, many scholars have written about this. For me, it was about how I could fit it into my longer genealogy. So the way she uses it is to demand rights for English women. By saying things like, “We English women are not like the women in the harem or the seraglio. We have souls, unlike them,” et cetera, et cetera. “So you can’t treat us like them,” right? So they became a foil against which English women were to be measured and compared. “Don’t treat us like them, give us rights, because otherwise you’re reducing us to being like those caged, uneducated, soulless women. And you’re making yourselves like the tyrannical Turk.” So this language is throughout A Vindication of the Rights of Women, which is her famous text from 1792. Muslim women feature in this bizarre way throughout this founding text.

“Don’t treat us like them, give us rights, because otherwise you’re reducing us to being like those caged, uneducated, soulless women.”

AA: One of the really interesting and important things that you point out are the ironies that existed. Because while these Western, or specifically British, women are saying these things, they themselves don’t have certain rights that the women in Muslim countries already had. Can you talk about a few of those ironies?

ES: In Muslim countries, they had these rights in theory but they didn’t always have them in reality. We know the gap between law and reality here today, but Islam in the 7th century gave women the right to contract, the right to own property, all of these rights. Whereas in Europe at the same time you could be an independently wealthy, unmarried woman, but as soon as you got married you’d be covered by the law of coverture. This meant that a man and woman would get married and become one, and the one is the man. The man would control the woman’s property. Whereas in Islam, a woman would retain control over her property. So, they didn’t know this or chose not to know this. Mary Montagu, who was of noble background but had no property of her own once she was married, felt this in a very visceral way when she went to Constantinople in the mid-18th century, because she saw how independent the women were. She went as the spouse of an English aristocrat, so she’s operating at a very elite level, she’s going to elite homes, she’s interacting with elite women. So we need to be mindful of which class level we’re talking about. She sees these independently wealthy women, and she feels the pain in a visceral way that, you know, “I don’t have access to this kind of wealth even though I’m supposedly an aristocratic woman, because the laws of my land don’t allow me these freedoms.” But again, she wrote a lot of things that should have challenged the ideas about Muslim men and women in her time. But she was up against a very powerful narrative about what Muslims were like, so it gets ignored.

And there were others, like the playwright Delarivier Manley, who wrote a play about polygamy. She had been cheated herself by being tricked into a bigamous marriage. And her point, again, it wasn’t to reform Muslim societies, there wasn’t a savior mentality. But she was using these ideas about the Muslim world to criticize English society, saying that they have such things happening here that shouldn’t happen here. But she also portrayed the Ottoman Emperor Suleiman’s wife, Roxelana, in a more positive way than others had, because any smart woman would have been seen as a threat by a man in many ways and they always depicted her as this cunning, scheming woman. And Manley depicted her in a more positive way. So, there were these positive depictions of life and women and men and relationships in the Muslim world. But the bulk of the narrative was going in a different direction, so it was very hard to make a dent in that.

AA: Two other things that, to my understanding, are protected rights in the Qur’an are divorce and, I don’t know exactly how it’s written, but it seems like more of an integrated and normalized sexuality for women. At least more than Western women enjoyed at the time.

ES: Right.

AA: Those seem to be really, really significant things that benefited Muslim women at the time too, that these British women just didn’t even know about, or like you said, chose not to know about. There was no way for them to have known about it, I guess.

ES: It’s similar to now. I mean, there’s a dominant discourse about what’s happening around the world, including in Palestine. And so anything that’s contrary to that, it’s very hard for people to say, “Wait, but everyone else is saying something else, so why should I believe the other narrative?” Similarly, yes, marriage in Islam is a contract, not a sacrament. There’s no “‘til death do us part.” Yeah, it’s a contract. And in theory, both sides can write whatever they want into that contract, including that if you marry another woman, we’re automatically divorced. Women can do that. Again, in reality, even Muslim women aren’t always aware of this. Muslim men may choose not to be aware, but you know, it’s a contract. In practice all kinds of things go wrong, but in theory, it’s a contract and you can write anything reasonable into it, which has always meant that divorce is definitely far easier among Muslims than it is in Christianity. Even Catholicism, of course, is more complicated, but even easier than among Protestants. I mean, there are stipulations and things that have to be met very often, so it’s not super easy. And the Qur’an does say that it’s not something one should undertake lightly, I think it’s even described as abominable, but it’s there as needed, right? Because sometimes you just need to end a relationship. So that provision is there. I’m sorry, what was the other thing?

AA: Just a more normalized sexuality for women, like enjoyment of it.

ES: Yeah, there is no idea of nuns and monks and monasteries. You do not show your devotion to God by being celibate, by renouncing sexuality. I don’t know that I spent too much time in the book on this, but there are hadith sayings of the prophet. One famous one that’s often cited is where someone asks about coitus interruptus, and the prophet says, “well, make sure you’re mindful of your female partner when you do this because it can be very abrupt.” So, you know, shower her with kisses, et cetera. There’s all this discussion, but the main point is that Islam talks a great deal about the significance of family and healthy sexual relations, all that stuff. So, celibacy, chastity, all these things are not how you show devotion to God. But on the other hand, sexuality, it’s very clear, should be within marriage. Sexuality is healthy, but it doesn’t mean you can go have sex with anyone, anytime, anyhow. Marriage is really important in Islam because it’s a way to regulate and to provide a legal place for sexuality.

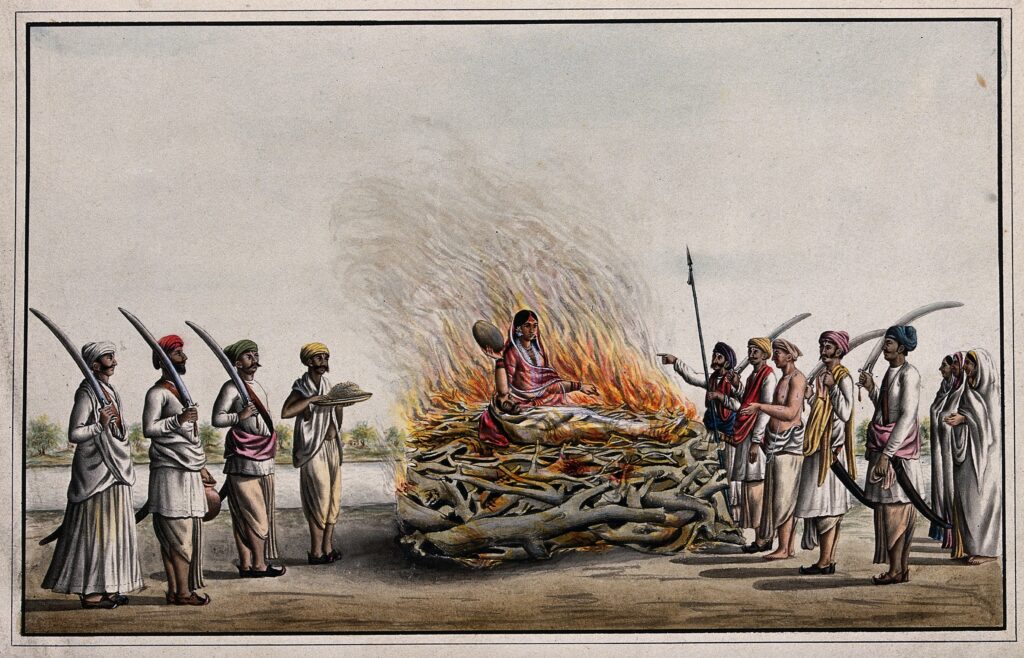

AA: Mm-hm, that makes sense. Okay, I wanted to see if you could talk about a few other customs that Europeans judged very harshly when they came to the subcontinent, and how they used these practices as an excuse for colonization. Which, as you mentioned before, happened all the way until the recent past with Laura Bush and our invasion of Afghanistan. But in the context that you were talking about, could we talk quickly about sati, about polygamy, and about purdah?

ES: So, sati is a practice of widow immolation, and it was practiced by a fraction of upper caste Hindus. So, it’s not a Muslim thing. Because it was so sensational to British eyes, they made it one of their big reasons for intervention, similar to the blue burqas they saw in Afghanistan. They were there for the riches of South Asia, but sati was something that they honed in on, zeroed in on, as something we needed to put a stop to. It became a big issue, but there were also local reformers who were very interested in putting an end to it because it made them look more modern. Scholars have written about how this is played out on the bodies of Indian women, again, Hindu women. It was not a widespread practice, but in size and because it’s such a dramatic thing, it features in Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne, the French writer. It was something like the harem. It became this obsession when talking about the women of India. That’s sati.

And then polygamy, I don’t think I detailed this in the book, it doesn’t come up in quite the same way, but polygamy was also fascinating because it’s so different from what’s happening here. And I just told you about Delarivier Manley writing in the 17th century, an English playwright who said, “You know, it happens here too. I’ve been tricked into polygamy.” In Islam, the Qur’an is very clear: “You may take up to four wives, but you have to treat them all equally.” And then it says, “Because it’s impossible to treat four wives equally, we suggest you take just one.” Since most interpretations of the Qur’an have been done by men, historically, they chose to read it in a way that sort of ignores the last part, or they claim that they can treat women equally.

One way that many Muslim scholars, and even modernist male scholars of the Qur’an, made sense of this is that before Islam, men in Arabia could actually inherit the women of their father’s household as chattel, basically, like you inherit possessions and you inherit the women. So you could have hundreds of women, depending on the wealth of the household, and I think maybe even officially married wives. So to say four was actually to limit the previous practice. Another thing happening in this time was that many men were dying in a war, so there was an imbalance in the numbers of men and women. And many women then were economically dependent on men, so one reason for this permission, scholars have argued, is that it allows its women who are left without a provider to be brought into a household in a legal way. So what you’re doing is taking someone in so that you can provide for them. Today, many Muslim feminist scholars are arguing that you don’t need that if you can ensure that women are not financially dependent on men. You don’t need this provision, right? So that’s the justification for these reform movements to very severely limit polygamy or to even ban it altogether. I think Tunisia, for example, has banned polygamy even though it’s a Muslim majority country. That’s where polygamy is now. I’m sorry, what was your third?

AA: Purdah.

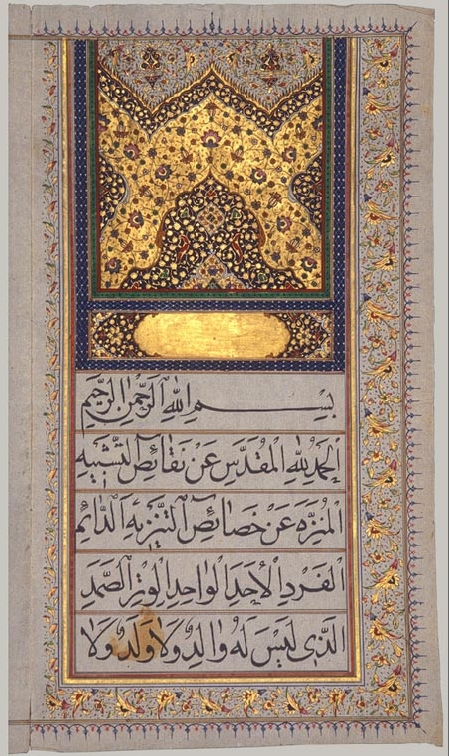

ES: Oh, purdah. Purdah comes from the Persian word “pardeh”, and it’s used in South Asia because Persian was the main language of the imperial court and the legal courtrooms until the 19th century. So it was the language of the elite, in that sense. Purdah just means curtain, so it’s tied to the idea of the harem and seclusion, the idea that men and women have separate quarters in the homes that can afford it. Or the burqa has been described as a form of portable seclusion. If women stay within the home, then they operate in different parts of the house from men who are not part of the family, men who come in from outside. But if you leave the house, then you take your seclusion with you. So that’s when you cover up and act modest. And there’s a great deal of discussion about what exactly is prescribed in the Qur’an. Some people say it’s to have a fully covered face and everything, others say that’s not it. Yet others will say the Quranic verses about modesty of a particular kind were directed to the wives of the Prophet only because they were recognizable. Obviously, as prominent figures in the community, it doesn’t mean that all women have to veil to this day. So there’s a great deal of discussion, which is as it should be, you know, there’s no bad answer on this.

AA: Yeah. And a great deal of variety, even in the Muslim women that I know. Like every religion, right? Like every group of people, you’re going to see lots of different interpretations and personalities.

ES: Absolutely.

AA: Those were all really interesting issues to hear you talk about again. And thank you for emphasizing again that sati was a Hindu practice, not a Muslim practice. It just strikes me in all of these examples that no one’s defending that and saying that that was a great practice. But the point that I took away in the book, and that I’m taking away now, again, is it’s just not the business, it’s not the responsibility, and it’s not appropriate for an outside person to come in. And it’s not necessary. It’s just so patronizing to come in and say, “We know better and we’re going to tell you what is and isn’t okay,” with all of these issues that you’re bringing up. Because you’re now describing indigenous movements to decide what they want to do, what feels appropriate to them. And just the patronizing outsiders coming in and saying, “This is bad, we’re going to tell you how to do it.”

ES: What’s interesting is that when they come in and say something is bad, people who might have been critical of it before go on the defensive. So it actually makes it much harder for local reformers, because then they’ll say, “Oh, you’re telling us that’s bad? No, we’re going to double down and say that this is part of our culture.” That’s happened time and again in Muslim countries and even with sati. There have been Hindu leaders who said, “This is our custom, it’s our culture. Don’t intervene.” And so they ended up defending it in a way that they might not have if outsiders hadn’t come in and made an issue of it.

People have made a similar argument about the veil. The veil, whatever that means, as you say, there are so many different ways of covering your hair or of being modest. But it was just the way people dressed in that part of the world, you protect yourself from the sun. And non-Muslim women also covered their hair, like Catholic women going to mass in the Mediterranean. And Leila Ahmed, a scholar of Islam, has argued that it was very commonplace in pre-Islamic Arabia and it was adopted by Muslims because it was already out there being practiced by elite women of other communities. The veil, in the 19th century, when the British came to India and to Egypt, they said, “Oh, what is this weird thing?” And that’s when the veil became a symbol to rally Muslims around, and so it’s the one that has to be defended against all onslaught. Whereas before it was just what people wore. Social convention has an effect on this.

AA: Yeah, for sure. And just the arbitrariness of people’s different dress standards strikes me too. Because for Victorian women to make a criticism about covering your body when you couldn’t show your wrists or your ankles… England is just so silly. Anyway.

ES: Also, all these men went out to save women in other parts of the world. Leila Ahmed has written about Lord Cromer, who went to Egypt and shut down a medical school for women because he thought women had no business being doctors. But then talked about the veil, and back home he was the head of the men’s league opposed to female suffrage. So there are all these inconsistencies, down to George Bush, and more recent people who talk about women in other parts of the world as being oppressed while they’re cutting back on reproductive rights here. Men who would not be considered feminists here, and they’re the ones going overseas and being “feminists” overseas.

AA: Yes. And like you talked about, too, in some of these situations their aim in being there in the first place is for wealth. It’s for control and power, and then they use it as an excuse. They use saving people as an excuse. It just seems like that’s happened over and over. If we have time for a couple more things, Elora, I want to move forward on the timeline. You recount the white supremacy in American feminists, the white feminism that has plagued us for generations. You write specifically about Germaine Greer, who, if listeners don’t know, was a very prominent feminist in the ‘70s. She had gone to India, as I think was fashionable in the ‘60s and ‘70s. She had spent a few months in India, and then she spoke at a conference about the Indian problems while Indian women themselves sat there listening to her. So she kind of supposed herself as an authority. I wonder if we could use that anecdote as a springboard to talk about this issue in general.

ES: Yeah, that’s a good one. She was born in Australia, but she’s presented there before.

AA: Oh, thank you.

ES: The 1960s and ‘70s were what has been called second-wave feminism, but has also been criticized because there are many problems with the idea of the waves. It takes off, and at some point there’s this new arrogance, like the arrogance of the 19th-century feminists I mentioned, like, “We have arrived. And yet look at the women over there,” right? So it gives a sense of superiority to feminists here. What we think of, the Gloria Steinem’s and Betty Friedan’s and Germaine Greer’s, is of course elite white feminism. They were heavily criticized by women of color, even within this country, for only talking about their issues. The best way to think about the relationships between these different movements in the last quarter of the 20th century coming into the 21st, is that when these classic names of second-wave feminism were talking, they were focused on issues that they considered to be women’s issues, very narrowly defined. Because as white women, they were seen as un-raced, right? They don’t have a race, and so they can just focus on what they see as women’s issues. Whereas women of color in this country, and Muslim women, and women all over the world, whatever their background, had to combine their fight for women’s rights with, as I said before, the fight against colonialism, the fight against occupation, the fight against racism in this country. So for them there was no such thing as a women’s issue that is divorced from everything else.

So the Germaine Greer example I give, she shows up a few times in different events in the book, is that she’d been to India and had come back, so she could speak about it. For me it’s a great example of the relationship between knowledge and power. So much of the writing in feminism, initially, is about other parts of the world. What we get from Edward Said’s Orientalism, for example, is that people in the West are able to travel to other parts of the world much more easily. And then they come back and they write, they get published, they get circulated, and so they get heard. So Germaine can go to India for a few weeks or months, I forget, come back, and be invited by whoever organized the conference. “Why don’t you tell us about Indian women?” when there were Indian women there. And I think there were actual Indian scholars in the audience. It’s not about identity, but about people who have experience and expertise about these other parts of the world. They’re not taken as seriously. Or even worse, they are taken as biased. The worry is that they wouldn’t be able to be objective about India or Islam or Muslims, whereas someone who is white is automatically assumed to be scientific and objective. So I think that’s a lot of what’s going on.

A lot of the writings published here about Muslims or about any other part of the world have been done originally by white men, and then increasingly white women, but they didn’t recognize their privileges. They enjoyed the fact that they could afford to go to other parts of the world, they have funding to go there, they have the passport that allows them to visit other parts of the world in a way that people from other parts of the world can’t come here as easily and do the same thing. And when they do, they don’t get the same kind of circulation. “What university do you teach in? Where are you from?” It’s hard to break into the publishing world to get your words out. I talk about Nawal El Saadawi, who is this very famous Egyptian feminist, going to conference after conference where these white women were talking about parts of the world that they had very flimsy and superficial knowledge of, when there are real experts that could have been brought in, or were actually sitting in the audience having to listen to, you know, Germaine Greer’s knowledge of India based on a quick visit.

white women were talking about parts of the world that they had very flimsy and superficial knowledge of, when there are real experts…sitting in the audience having to listen

AA: Yeah. That leads us to the last question that I wanted to ask you. And that is, what are some takeaways for listeners who want to be better allies to their Muslim sisters, and specifically listeners who aren’t Muslim? How can we be better allies?

ES: One of the things I try to do throughout the book, I think there have been lots of studies on anti-Muslim racism or Islamophobic practices, or going back to the Middle Ages and Early Modern era, anti-Islam hostility. I didn’t want to focus just on those. I mean, those things are there, so they come up. I was much more interested, or as interested, in bringing out people who are willing to challenge the dominant narrative.

Like Delarivier Manley and Mary Montagu fighting against what Mary Astell and Wollstonecraft and others were saying at the same time. Throughout and all the way down to the present, there are people, non-Muslim travelers from Europe and North America, who go and really try to understand and go beyond the narratives that they had been immersed in before.

I think even to this day, it’s the same idea. We know that there is a dominant narrative out there. In fact, I was thinking when you were talking about the Turk, it’s the same now, right? Palestinian equals terrorist. There are these associations that are out there. So, to go beyond these dominant narratives. Part of it is education, part of it is media. You’ll probably get a better sense of the different narratives in social media now, which is scary, than in the mainstream media, which is fairly homogeneous. But of course there are a lot of books and articles. You don’t have to be an academic person or a scholar to read some of this material. I have colleagues and friends who write for the popular press. It’s easy to find those to educate yourself. Because it’s very easy to let the mainstream ideas come in and say, “Oh, well, that’s what I’m hearing everywhere. I’m immersed in that, so that must be true.” No, we question those narratives and dig beyond to find alternative ideas and then make up your own mind, right? I’m not saying “believe this and don’t believe that.” Look at the different stories and see which one really makes the most sense.

And then meet people who are not like yourself. Meet people who are Muslim or Indigenous, or on any issue, talk to the people from those communities and talk to more than one person so that you can see the differences among them. Because there’s variety within these communities. Not all Black people, not all Indigenous people, not all Muslim people are the same. So, go beyond your comfort zone. I talk to students here at Berkeley, and many of them have come from small towns where they didn’t know people who are different from themselves. And then coming here, meeting other students was different. Even here they could stay in their bubble, and many of them do, they stay in their familiar bubbles, but many reach out beyond that and they talk about how eye-opening that’s been. It takes effort. And then once you meet these people, what do they say about a particular issue, whether it’s the veil or Palestine or the environment, right? How do they see it? What are their thoughts on it? I think it just takes effort, and some effort is easier than others, but I think that’s where it has to happen. How do they understand feminism?

AA: Thank you for that. And I will say again to listeners, your very first step should be to buy this book. I’m serious, it was just so wonderful. It’s called Sisters in the Mirror: A History of Muslim Women and the Global Politics of Feminism. And again, Dr. Elora Shehabuddin, thank you so much for being here. I learned so much from you and I’m really grateful for your time. Thank you.

ES: Amy, thank you! I really enjoyed our conversation and thank you for your kind words about the book.

people talk about women in other parts of the world being oppressed

while they’re cutting back reproductive rights here.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!