“There’s such a severe under-diagnosis of girls with autism

and it’s definitely because of patriarchy”

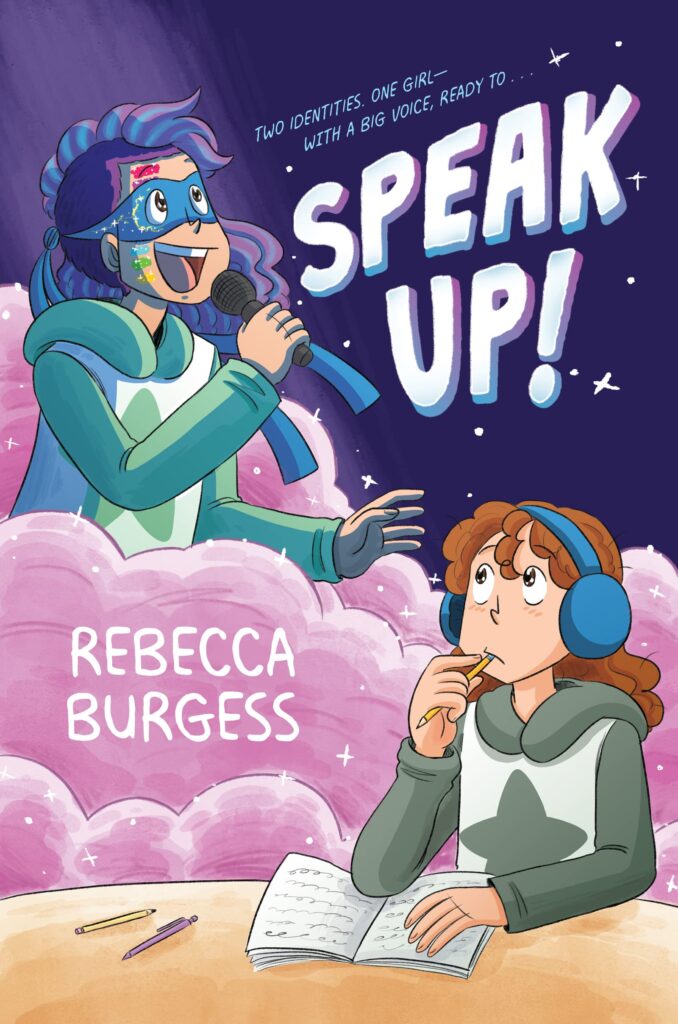

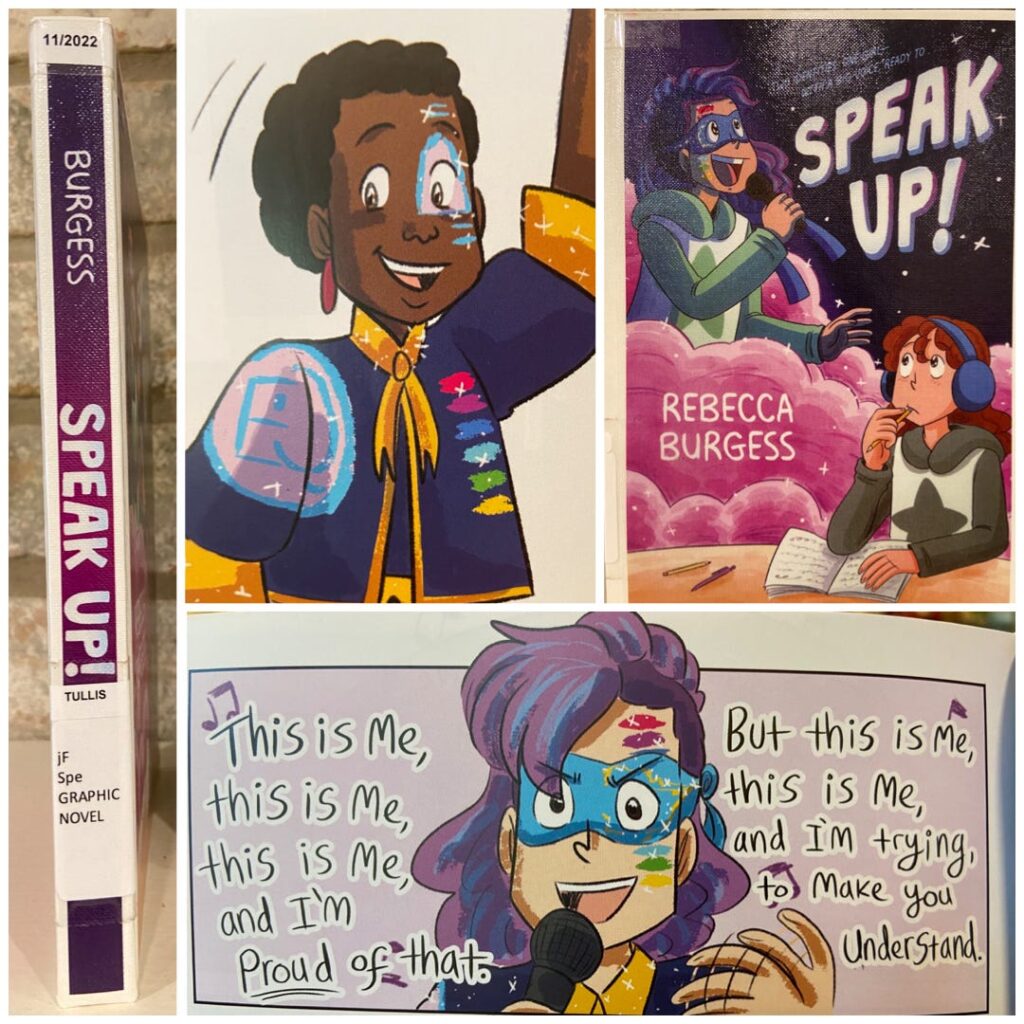

Amy is joined by author & illustrator Rebecca Burgess to discuss their graphic novel, Speak Up!, and explore the impacts of patriarchy on the neurodivergent community. Rebecca shares their personal stories of growing up with autism, discusses the importance of representation, and shares invaluable advice for parents and peers of autistic children.

Our Guest

Rebecca Burgess

Rebecca Burgess a freelance illustrator currently living in Bristol. Their favorite things are nature, history, comics, psychology, and cuddling their girlfriend.

Burgess is most well known for their various long and short comics that explore and explain autism. Their comics are also known for showing big feelings and loveable characters that people can connect to on a personal level. They have both written and illustrated several award winning YA and children’s books/comics, including Speak Up! and How to be Ace.

The Discussion

AA: Today, I’d like to start by reading some song lyrics, which say

“I’m creative, strong-headed, inventive, and honest too. My senses have made me stronger. I’m a fighter who can push right through. Pushing forward, seeing things that no one else can see. My passion knows no bounds. Yes, this is me. This is me. This is me. I’m creative. Hard to see. I freak out, but I’m brave and I’m proud of that. They say my autism gives me chains. They say it hurts my family, but my autism sets me free ’cause this is me.”

These inspirational lines which challenge us to rethink our understanding of autism are sung by a young woman named Mia, who is the protagonist of the book Speak Up!

This amazing, encouraging, and joyful graphic novel follows Mia, a middle school girl with autism as she and her best friend invent an alter ego, the music sensation LQ, and we get to follow what happens when their make-believe musician finds very real success. It’s a story about friendship and family, and about finding pride in yourself, and I’m so, so excited to be discussing it today with the author and illustrator of Speak Up!, Rebecca Burgess. Welcome Rebecca.

RB: Hi. Hello.

AA: It’s so great to have you today, and I’ll just start with kind of like a professional bio so listeners can get to know who you are and then you can tell your own story after that. Rebecca Burgess is a freelance illustrator, currently living in Bristol, England. Their favorite things are nature, history, comics, psychology, and cuddling their girlfriend. Rebecca is most well known for their various long and short comics that explore and explain autism. Their comics are known for showing big feelings and lovable characters that people can connect to on a personal level. And today we’ll be discussing their most recent book, which Rebecca both wrote and illustrated Speak Up!

So Rebecca, could you tell us a bit more about yourself and your personal background, like where you’re from and what brought you to do the work that you do now?

RB: I’m from the UK, Bristol, and I got into comics just because loved drawing. Like literally since I was tiny, probably three years old or something. And I mainly got into comics through manga because comics aren’t really a big thing in the UK. Like even now, they’re not a huge thing. Like my comics are bigger in America than they are here. Really like shelves and shelves of comics. But in the UK if you go to a big bookshop, you get like one little shelf of maybe like 20 comics on it, but we have huge shelves of manga. So I grew up reading Japanese comics and the great thing about Japanese comics is that you get such a wide range of genres, all kinds of people. So growing up as a girl, manga was very appealing. Because we had a lot of comics that were aimed at teenage girls, and I feel like that’s my main influence.

And then I started making comics when I was 13 and then selling them at comic conventions. Where comics are big in the UK is at small press comic conventions where everyone just makes it themselves ’cause publishers won’t do it. And I’ve just been doing that for years and years. And then I finally got an agent at some point in America and now, yeah…now I can do it full time.

AA: So I wonder if we can start really basic, if we’re talking specifically about Speak Up!, this book, start really, really basic and establish some definitions for listeners who might have heard these terms before, but maybe they aren’t sure exactly what they mean. So could you start by defining three words: first Autism, second Neurotypical, and then third Neurodivergent.

And of course, if there’s any other vocabulary that you’d like listeners to know, we can include that as well. But first, autism, neurotypical, and neurodivergent.

RB: So autism is quite hard to define because it encompasses a lot of different things. But it’s basically the label that you put on someone whose brain kind of functions differently. With autism, it’s categorized generally by how well you socialize (your talking skills, especially when you’re younger), sensory issues (which is kind of like if you are very sensitive to things like light and touch and taste) and also the other way around, like on the opposite end as well (if you’re very un-sensitive and just can’t even feel if you’ve hurt yourself) things like that.

There’s loads of different aspects and you kind of tie them together into the term ‘autism spectrum’. Which is why it’s a spectrum–which people normally get mixed up about where people think it’s sort of like you’re either very autistic or not autistic. But spectrum more refers to the fact that people who are autistic might have some of the stuff I’ve talked about and then no experience other stuff like a neurotypical person. So, yeah, that’s my very complicated way to say it. I should probably say the stereotypical…but I know it too well, so I can’t describe it the way that maybe people would expect it to be described.

And then neurotypical kind of refers to basically the majority of the population, you could say. So the typical way in which people operate, like the way that your brain operates basically. And then if you think about neurodivergent, in contrast to that, neurodivergent is basically all the various kinds of people that operate in a different way. There’s lots of things that fall into that. A nice easy one to think about is probably dyslexia would be considered neurodivergent in the sense that the majority of the population can learn to read and write in the standardized way that we teach people in school. And then there’ll be a small amount of people that have to learn different ways to read and write. Therefore, they are neuro-divergent. And then you have various things under that scope such as ADHD, autism, dyspraxia, dyscalculia. It’s just different ways that your brain works that impacts how you interact with the world and how you interact with other people.

AA: That’s great. Thanks so much.

Okay, so my next question for you, and this is kind of combining…you know, I first asked you kind of your life story, where you’re from and what brought you to the work you do, and then you defined some of these terms. And then obviously the story that you’re telling in your book is about a main character with autism. And I’d love to start by hearing you tell what your own experiences have been with autism, and especially like while you were growing up. I’d love to know when you discovered your own autism and what that experience was like, did that inform the character of Mia in the book?

RB: Yeah, it definitely informed the book a lot. She’s mostly just like me when I was 13. I didn’t know I was autistic until I was older because I’m just old enough that it was kind of underdiagnosed when I was growing up. I think the majority of people that were diagnosed were nonverbal so that it was picked up when you were tiny. But yeah, I wasn’t diagnosed until I was in my twenties. I always kind of knew I was different, but I didn’t really understand why and I felt quite embarrassed about how I experienced stuff. I generally felt like I was too sensitive, getting everything wrong, and that the hurdles that I faced were my problem and not something that I couldn’t help.

I had a lot of problems growing up. I think the main problems I had were maybe a lot of bullying when I was a kid, ’cause I just really wasn’t… I just operate on a different level socially. Maybe I take people too literally, I think. And people, I think don’t take me literally enough. So I would say exactly what I’m thinking, but some people will want to look into it more than there is and then take things the wrong way.

And also when you’re a kid in school, if you’re a bit different, then I think kids just don’t know what to do with that and then they’d start bullying you ’cause they’re not quite sure what else to do. I don’t think it generally comes from a bad place ‘because children are just children. They’re not being mean on purpose rarely, but you become an easy target if you are very different.

I always kind of knew I was different, but I didn’t really understand why and I felt quite embarrassed

I wrote Speak Up! because I wanted to see characters like me, main characters that were like me, and I wanted autistic kids to read it and kind of feel okay with being too sensitive or finding situations that everyone else seems to find so easy and they find them hard. I want them to see that in a book; in a fun, entertaining book. And then it will kind of make them feel better about themselves rather than feel really self-conscious about it. I feel like that was the name driver for the book and it’s that it’s achieved because loads of kids and parents have written me about this. It’s definitely achieved its purpose.

AA: That’s wonderful. Two things occurred to me as you were talking about that, first of all, how powerful and inspiring it is that you said you didn’t see main characters in books that would’ve benefited you as you were growing up. And so you created it, right? Like you saw this lack and so you decided to do something about it. You created it yourself. That’s just really beautiful and empowering for anybody hearing this. And then the other thing is how important it is that a person with autism is the one writing the book with the main character with autism. Can you speak to that a little bit? Like have you read any books where it’s a person who isn’t autistic writing about people who are autistic, and does that feel a little off to you? I imagine that it is a really powerful thing to have someone be writing from their real lived experience.

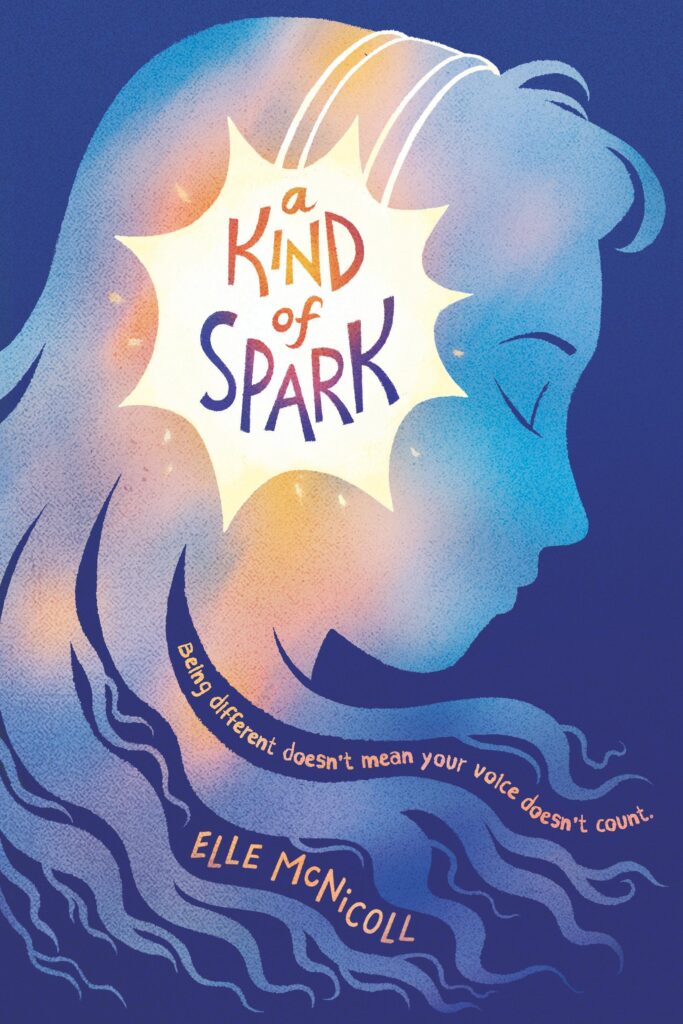

RB: Yeah, I definitely feel like my favorite books with autistic characters are ones that have been written by autistic people. Like, A Kind of Spark. When I read that, it just kind of felt like…I don’t know if you know that. It’s kind of quite a big kids’ book over here, a children’s book with an autistic main character. That just felt like therapy reading that. But I’ve also read The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. It is quite a famous one from quite a long time ago now, and that maybe… not so much. Because I find this, especially with, I’ve seen a lot of TV series with autistic characters who…

I think if you’re not autistic you tend to misunderstand some of our behaviors, which is totally understandable. I can see why you would. You can’t climb inside someone’s brain and figure it out, but it gets really misconstrued. I feel like the most common thing maybe is just this idea that we don’t have any feelings, which I find really strange, but that’s a really common one. Even in things like The Good Doctor, which like…I enjoyed it, but it did have this common problem where the main character was like, Hmm, I don’t know how to feel things. I am a robot, and I haven’t met a single autistic person like that.

I’ve met some people who take a little while to recognize what they’re feeling, but that’s very different to I don’t have any feelings, which is very much how I come across it lot of the time and like… just because someone has an odd way of speaking or isn’t very good at navigating relationships, it’s normally just because the way that our brain works means that our tone of voice is different and we have difficulty navigating relationships normally just cause it’s almost like you’re speaking a different language to each other. So there’s lots of misunderstanding, but you still feel everything inside. We’ve still got feelings. That’s just one example, but there’s a few things like that.

AA: Thank you for that. I learned a phrase and maybe I’m kind of late to learn this, but I heard a phrase just in the last year from a person who actually runs a big center and specifically works with people with autism, and the phrase is “nothing about us without us.” And that really, really struck me; like how important it is to make sure that people are able to speak for themselves and not have an outside group come in and assume that they know and speak for them.

So I imagine that goes in everything from literature like you’re describing like stories, like The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time or the media that you said, and I’m guessing even in like the medical and scientific community of people going in and speaking for people.

RB: Yeah, the phrase has very much been coined for medical situations. I mean, I still hear some awful stuff like people who are restrained for no reason and they’re restrained because they’re misinterpreted. If you have a meltdown, say, it’s misinterpreted to someone that’s going to be dangerous. But it’s almost like the worst thing you could do…I’m not sure about restraining people anyway, but the worst thing you could do is restrain someone who…the reason that you’re having a meltdown is normally because you are overstimulated. Restraining isn’t going to stop them or calm them down. It’s just gonna make it worse and just make the whole situation more stressful. Yeah, but “nothing without us”. That phrase is very much like, stop treating us like animals. You know? Just because you communicate in a different way doesn’t mean it’s like you are not a human being. You need to listen to us.

AA: Yeah. Well, tell us about this book, Rebecca, and how it came to be. Why did you feel compelled to write and draw this novel? And then I’d love to hear what the responses have been like since its release.

RB: Yeah. I mainly wrote it because I didn’t see anything like this when I was a kid. I just wanted something really fun. I wrote previously a lot of depressing stuff about autism where it’s sort of like a sob story, like, oh, how, how terrible it is to have this disease called autism. And I wanted something that was really fun and lighthearted. I mean, obviously Speak Up! gets quite emotional and it tackles some stuff and it creates some talking points, but it’s kind of wrapped up in like a fun Hannah Montana kind of story and an addictive drama kind of story. Like twists and turns of a normal kid story where you just want to keep going…that was the point of it. And yeah, like I said before, just to kind of make autistic kids just feel good about themselves.

I’ve got really good responses. I get emails all the time from parents and kids just saying how much they loved it, how much they saw themselves in it. I know I went to a comic convention this weekend and literally the second person that I saw that morning, like the convention opened at 10 o’clock in the morning, and then at 10:15 this mom came over who was from Canada and she told me that her daughter was autistic and like read it within an hour, like just read it in one setting and then immediately came up to her and was like, this is amazing. I see myself in these pages; we need to read this together. And then they were reading it together and it made her mom think about whether she was autistic as well. And then she kind of made her own discoveries through that as well. It was very touching.

AA: Oh, that’s awesome. That’s so great.

RB: Yeah, that happens sometimes. That’s what I want. Just wanna help people.

AA: So throughout the book, Mia is regularly at odds with her mother, who is a very well-meaning, but kind of a misunderstanding character. She tries her best to help Mia fit in, and she encourages her to socialize and to act like the other kids. But that requires her hiding pieces of who she really is, right? So the mother, even though she’s trying really hard probably to protect Mia, she does see Mia’s autism as a burden.

It’s really heartbreaking to watch this. She’s a single mother and she just has nothing but the best intentions for her daughter and is trying to keep her safe, but it’s very clearly causing harm. So I’m wondering if you can talk about what guidance you would have for parents who maybe have recently learned that their child is autistic or suspect that they might be. How can we avoid the mistakes of the mother in your story?

RB: I think probably the first thing is to probably be careful what information you read online. I think it is probably better to get information from books and buy books that are by autistic authors. ’cause there’s loads of informational books now, both aimed towards kids and adults that have been written by autistic people, and they have that childhood experience. They just have the hindsight to know what really works for children and what doesn’t. And there’s really good books out there now about this. So definitely look at that rather than the internet. ’cause obviously the internet kind of siphons itself off into different extremes and you can get really confusing advice, like different advice depending on just which area you happen to stumble upon when you’re looking at the stuff. And then both sides can be a bit extreme and then you can’t find a good middle ground that’s maybe a little less scary or confusing. So get some books.

I’ve illustrated a book for kids recently called Being Autistic (And What That Actually Means). That’s literally the title, written by someone that writes a guidebook for autistic people. And we made this one specifically for primary school age–so the kind of age where you might find out from your parents that you are autistic or will be recently diagnosed. And apparently it’s been really helpful so far. So that’s a good start.

And then I think from this academic kind of advice, I think maybe just be patient. Don’t push your kids because sometimes you’re in a situation when you parent where you know that a kid will benefit from doing something, but they’re just not doing it. I mean, situations like social situations, like going out more or doing something new or trying more healthy food…things like that, that could be really difficult if you are autistic. And parents get into a situation where like…you’re really worried about the kids and so you’re really trying to push them to do it. And I think unfortunately when you’re autistic, it just stresses you out more. It just really stresses you out and you just dig your heels in. Like we’re too stubborn unfortunately, and pushing doesn’t really work and it just makes sort of these traumatic situations and something like trying to eat more healthy can turn into an eating disorder.

So it’s better to not worry too much and let them go at their own pace. They will get to the point that you want most of the time, but you really need to let them go at their own pace basically, even if it’s not at the same pace that other kids are going at, just let them take the path their own way. And they will find their way.

let them go at their own pace…and they will find their way

AA: That’s reassuring, I’m sure for parents to hear. That’s really hard as parents. It really is. But it reminds me of the next question that I was gonna ask, which is just, especially if it’s a parent who is not autistic and then has an autistic child. You referred to this earlier in our conversation too, of just misunderstanding what the autistic person is trying to communicate to you. And I know in your book a lot of Mia’s struggles also seem to stem from misunderstandings, like with her classmates who would interpret things like not making eye contact or being quiet as being rude. So I guess my next question would be what could we be teaching our children who aren’t autistic to help them be more supportive of their autistic peers and classmates?

RB: Yeah, I think maybe just approach kids that you think are strange and then maybe teach kids to react to it in a different way. Because I think kids’ automatic reaction is to basically shy away from a kid that’s different to them. But I feel like something you could teach is to just be curious. If you don’t understand a kid, ask them questions or just try and play with them in a different way. Be creative and be curious. I feel like that’s a nice sensible way to approach it with a kid. Because everyone is different in different ways, so it can be quite complicated. But if you are those two things–creative and curious–then I think you can kind of make friends with people that you maybe weren’t expecting to make friends with. And that’s the best you could do is just make friends with each other.

AA: I love that. And that’s great advice across the board for any differences that we encounter, and actually, not just for children, but all the way through adulthood, right?

RB: Yeah, that’s true.

AA: Curiosity and compassion and empathy. Yeah. That’s such good advice. And it occurs to me too, again, just thinking about little kids, and you were so lovely at the beginning, even talking about your own experience with bullying, which is so hard and so painful, and you were so gracious in your willingness to give the benefit of the doubt to children and just say, you know, I think most of the time children are not meaning to be cruel. They just don’t know; they’re just kids. That was very gracious of you. But one thing that I thought of is how important it is also for the autistic child to have a vocabulary to explain like, oh, I’m autistic. You might notice this. And I think your book and all of the literature that is being produced helps everybody to have a common vocabulary as soon as possible so that people grow up being able to describe themselves. People then come to a conversation and think, oh, I’ve heard of that. Oh yeah, tell me more about it. And people can talk about it more easily.

RB: I never thought about it that way, but it’s a very good point. That’s a really good point.

AA: Well, I was gonna ask you too, like you said, oftentimes we only hear negative stories about autism or kind of cast it in this tragic light, and I’d like to have you continue to challenge that and you have already in the conversation, but I’d love to hear a few of your favorite things about autism and being autistic.

RB: I feel like my favorite thing about it is maybe… yeah, quite a lot of things, but probably the biggest thing is maybe like I’m very passionate. I’m absolutely obsessed with some stuff. They call it hyper-fixations, and it really does go quite a bit beyond normal, I think, because life can be so stressful for me that if you find something that you really love, you kind of really attach yourself to it in a different way because it just makes everything better. And thankfully the thing that I love is drawing. It means that; I’m very productive. I’m prolific compared to some people I know. I make a lot of stuff. I do this full time, which means I’m very self-motivated. It is quite hard to be a freelancer if you don’t have the motivation, which is totally fine, like I think that’s understandable. But yeah, I feel like I have that on my side.

And also just because I’m quite hypersensitive to stuff, I think I notice a lot of stuff that other people don’t seem to notice. Nice things. Like I notice not nice things, but I notice lots of lovely things as well. Like the way that the trees are moving in the light or something like that. You know, like nice little things that make everyday life more magical.

AA: That’s beautiful. Wow. Thank you for sharing that. That’s really amazing.

Okay. Another question that might not be as obvious, but that I’m really curious to hear your answer to. I’d love to hear how patriarchy uniquely affects the autistic community. What would be some challenges that you see most often with people with autism kind of butting up against that have to do with patriarchy?

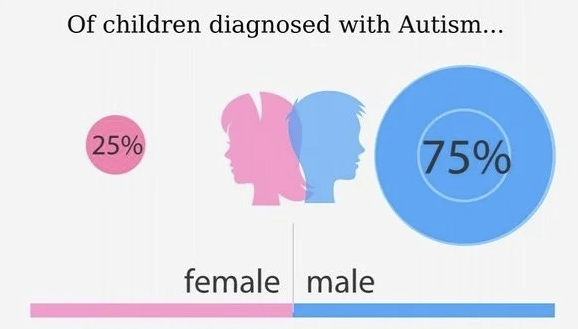

RB: Yeah, I mean, I think this is widely talked about in the autistic community. There’s such a severe under-diagnosis of girls with autism and it’s definitely because of patriarchy. I mean, we’ve got these other problems, like medical issues around the reproductive system, right? A thing completely under looked because when men are running it, the medical system is just sort of like we don’t care. And it’s kind of the same thing with autism, where for a very long time it was only really looked at in boys. And it’s weird because like I think most of us can see how it’s happened, but for some reason the medical community continues to ignore it. Basically, if you’re raised a boy, you’re raised to kind of be more vocal, put yourself out there, not worry so much about consequences. Don’t be meek, don’t hide yourself, things like that. So, of course naturally, if you are autistic, and then at the same time raise to just do whatever you want and don’t worry about the consequences, then the problems that you might face are gonna be more out in the open.

But if you’re socialized to be a girl then it tends to be like, sit down, be quiet, don’t ask questions, all this kind of stuff… and it gets interpreted in a very different way. And then it means that if you are autistic and raised a girl, then first of all, you are already from a really early age learning to hide who you are and you are learning these skills that all girls I think are taught literally from the age of two and a half; to just hide yourself. So then you learn much more easily how to hide problems that you’re having and how to navigate social problems in a more subtle way because girls are also–from a ridiculous early age–taught social language, like emotional language. But boys from a very early age aren’t taught…If you’re socialized one way or the other then it comes out in all these ways so that for a long time autism was considered only a male thing.

The main person studying autism in the UK for quite a long time, he had this theory that… it’s a really stupid theory in my opinion, but this theory that if you have a male brain then you are more likely to get autism. And if you have a female brain, then you are less likely to get it. But I think all of that is bullshit anyway. All this gender stuff; it doesn’t really make any sense when you take apart gender. But because he was running the show for a very long time, the way that he diagnosed people was completely built around male stereotypes and even the screening tool even now that you get for autism–the sort of main screening tool that you might find online if you’re trying to decide whether you’re autistic–will have these really silly questions that are very male orientated. As in like “when you’re a child were you really interested in trains?” or “did you really like math?” And the problem with those kind of questions obviously is that…I mean, it already kind of cuts out literally anyone that doesn’t like math or trains. But even more so like cuts out someone who’s socialized to be a girl because again, if you’re socialized to be a girl at the moment, you have this problem now where you’re kind of discouraged from doing things like math or being interested in trains, and then it would just like completely go under the radar. An autistic girl might have an absolute obsession with boy bands, like a really undying obsession with boy bands. But because it’s boy bands and not math people will be like, well, that’s not autism. You like boy bands, but you’re not obsessed with dinosaurs or trains or math. So you couldn’t be autistic.

So that’s how you got this misdiagnosis for a long time. It’s changing more recently because people have started talking about it, but I think that’s quite a good example of how patriarchy has affected that. That’s probably the biggest problem.

AA: Thank you for that. I’m curious if that played a part in your own path. Because you mentioned that you went quite a while without being diagnosed. Do you think that was at play at all for you personally?

RB: Yeah, I would assume so. And also because my mom’s a therapist and a psychologist, so I was equipped very early with understanding my feelings and emotions and the language for that. And that’s another thing that for quite a long time, up until recently, people would say like, I can’t diagnose you with autism because you understand your feelings too much or like, you know, you have feelings. And I probably, more than the average person, am quite good at that. Literally just because I’ve been brought up in a family environment…But that also comes into the girl thing, you know?

AA: Yeah, I was gonna say, I wonder if that also skews because boys are socialized to not have as much facility identifying their emotions and expressing their emotions, and so that might kind of artificially reinforce that conception. It would get more boys diagnosed. I would think if they have that misperception of autistic kids not having feelings and then boys aren’t raised to articulate their feelings, that would kind of create kind of a cycle of more diagnosis for boys than girl.

RB: Yeah. And then any boys that are on the opposite side of it. Because obviously autism sort of works in extremes. So if there are boys that feel very sensitive and feel things very strongly, that might be because of autism, but they’ll be equally going under the radar ’cause they’re not fitting that stereotype that has been set up in the medical system for a long time.

AA: That’s really, really fascinating. Well, hopefully it’s starting to change and will just continue to change as it’s being talked about more and brought to people’s attention, I hope.

RB: Yeah, it’s definitely like, I’d say in like the last six, seven years, like definitely changing

for a long time autism was considered only a male thing

AA: Okay, well let’s shift gears. I was made aware that you are the proud author of not one, but I believe at least two books which have been banned in many schools, and that is crazy to me. So I’d love to hear about the other book that you wrote. What is it about? And then how does that happen? We did an episode on how books are banned here in the United States, but how does that happen where you are and why were your books put on the banned list in some places?

RB: God, I don’t know. I made a book called How to Be Ace. It’s about asexuality. It’s sort of like a autobiographical book about asexuality and my experiences with that. I think it’s just because it goes against the norm.

It’s funny, some people when I’ve told them that it’s been banned, a lot of people laugh, which I get a bit annoyed about ’cause it’s not a funny topic, it’s a scary topic. But people do find it funny because… for anyone that doesn’t know, if you are asexual, then it generally means that you’re not interested in sex. So the idea that a book about not being interested in sex would get banned is very strange. Because people assume that the reason that books are banned is because they’re super sexual or pornographic or dangerous to children in some kind of way.

We all have different opinions about that, but I think probably my book is quite a good example of how the reasons that people are banning books isn’t maybe for the reason that they might be saying to the public. You know, this narrative of like, “it’s dangerous for children and they’re gonna be hypersexualized very early when they look at all this LGBT stuff. That’s gonna rock their minds and they’re gonna see it too soon” and this kind of rhetoric that I’m seeing. But the fact that they’re banning books about not having sex. It sort of goes against the dangers that they’re warning against because if you ban a book that’s letting people know basically that it’s okay to not have sex, if you feel very uncomfortable with that, if you ban books like that, then you’re kind of doing the opposite of what you say you want to protect. And I think it says a lot about the real reasons that people want to ban these books.

AA: Why was Speak Up! banned? Because that I was kind of baffled by that. What are the reasons that you’ve heard?

RB: I am going to assume because I haven’t looked into it, I’ve just seen it on lists and libraries. But I think maybe it’s because one of the characters in it is nonbinary. But it’s not talked about, like it’s just sort of there, they’re just there as part of that story and it’s not really addressed. So I think some people don’t notice it, and then probably the odd person has noticed it and then got angry about it and thought that it’s dangerous for children.

AA: Just the existence of the character?

RB: Yeah. It doesn’t even address the issue.

AA: Okay. I have a couple more questions for you, Rebecca, before we wrap up. One thing that struck me was in the introduction to the book and you wrote that you want autistic children to feel proud of themselves and all of their “good and bad experiences”, and I thought that was really interesting and wonder if you could tell us a little bit more about that. Why does pride in bad experiences matter also as well as being proud of good experiences?

RB: I think with everyone–not just autistic people, but with everybody–if you can be okay with the fact that sometimes you have negative feelings, I think it just makes everything easier.

I think shame was quite a big issue when I was a kid, especially whenever I had a meltdown. I would feel so bad about it afterwards and, and that carried on into adult life where I still apologize for asking for help and I’m not very good at asking for help from people showing my feelings. So I think it’s important to show things like meltdowns, but rather than frame that as something that’s inconveniencing everybody else, in Speak Up! I’ve kind of framed it as how you experience it, which is like, this is something that’s completely out of my control and it’s scary and horrible and it makes you feel really sick and then you feel really embarrassed afterwards. So like I’ve kind of gone through the process of even showing the embarrassment, but then…I kind of hope from that then I could come read it and be like this is a thing that other people experience and I’m not alone in experiencing it. And the main character that experiences this, she feels scared and anxious and has meltdowns, but then at the same time she does all this really cool stuff and achieves all these things that suddenly they’re able to achieve. And she ends up being really proud of herself and she’s kind of like a special person in her own kind of way.

I don’t know if that makes sense, but I just wanna show all of it so that kids can just be okay with not being okay sometimes. Because you know, it’s not all great, but that’s just part of life and it is not stuff you have to be ashamed of, I guess.

AA: Awesome. Well, that kind of is a great segue into the last question I wanted to ask you, which is the theme of this season on our podcast is The Serenity Prayer of thinking about how we can have the strength to make the changes that we can, to do the things that we can, and then the serenity to accept things that we can’t change, and the wisdom to know the difference. I wondered if you could maybe speak to a change that you would like to see in the world. Maybe it could be in the autistic community or outside the autistic community. What are some things that we could do to make the world a better place?

RB: Ooh, I’ve got a long list. Ha.

AA: Yeah, for me too.

RB: It’s just the times at the moment, everywhere.

I think maybe the main thing is just like we were talking about, like you said compassion earlier. I think compassion for me is a very big, big thing that leads my life as well. You could probably tell the way that I describe things, I’m quite balanced. I like to look at all the different points of view. I’d quite like it if other people did that as well. Like when you’d see something that gives you a visceral reaction, rather than feel scared or angry or standoffish, just put it down for a minute and try to step into other person’s shoes and be compassionate. And then maybe if everyone’s like that, then you can start having calmer conversations and finding a middle ground in like a very divisive, very divisive landscape at the moment.

AA: Yeah, that’s definitely the world I wanna live in, so thank you for that.

Well, Rebecca Burgess, this has been such a delight. I learned so much from you. And as my final question, I’d just love you to tell listeners and viewers where we can find your work. How can we find Speak Up!, and anyone who’s listening who might be specifically interested in this topic of autism, where can we find everything that you’re doing?

RB: Yeah, you go to rebeccaburgess.co.uk. That’s the easiest ’cause my social media accounts have a weird name that I can barely pronounce because it’s just like a name I came up with years ago that I don’t have to add numbers to.

AA: I love it. Well, we’ll have those on our social media so people can find it.

RB: Yeah. I’ve got loads of stuff I like. I do more comics as well, like I do web comics with autistic characters. So if anyone’s interested in exploring those themes, then I’ve got a history comic about someone from history who’s autistic. I’ve got like a romantic regency romance comic with an autistic person. I’ve got all sorts of stuff.

AA: Amazing. Okay. Tell us one more time your website so people can find it.

RB: rebeccaburgess.co.uk.

AA: Perfect. Well thank you again so much. I so enjoyed this conversation.

RB: Yeah, it was fun.

the best you could do

is just make friends with each other.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!