“the revolution got louder and louder and louder until it was felt everywhere”

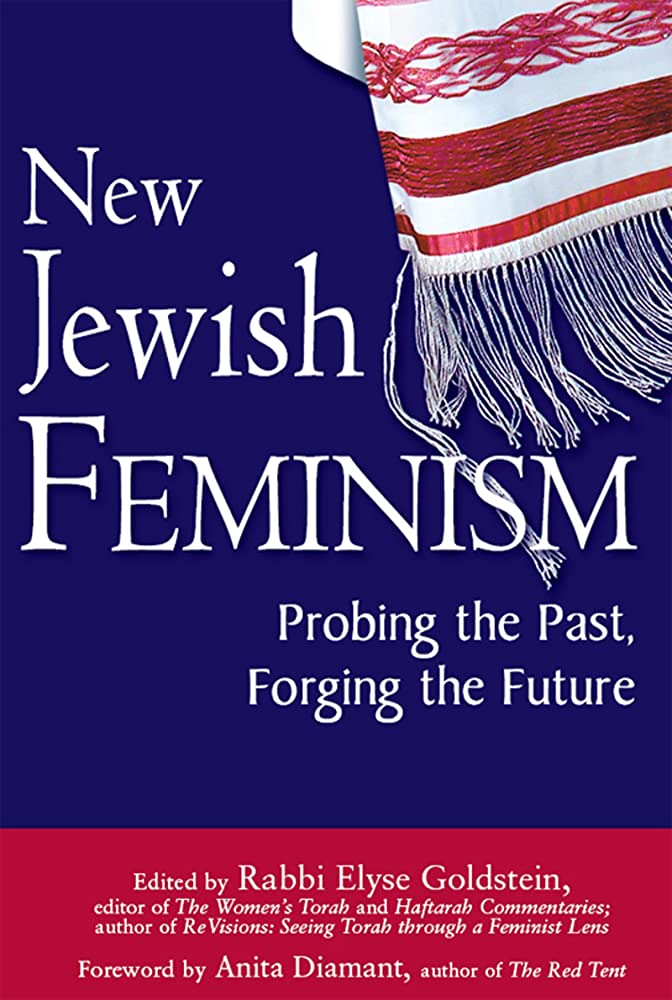

Amy is joined by Rabbi Elyse Goldstein to discuss her book New Jewish Feminism: Probing the Past, Forging the Future and learn about the legacy of feminism in the Jewish tradition.

Our Guest

Rabbi Elyse Goldstein

As one of the first woman rabbis in Canada, Elyse Goldstein has broken down barriers by founding inclusive communities for learning and prayer. Goldstein graduated from Brandeis University in 1978 and was ordained by the Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion in 1983. After ordination, she became assistant rabbi at Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto. Then sole rabbi of Temple Beth David in Canton, Massachusetts in 1986 before returning to Canada in 1991 to become founding director of Kolel, the Adult Center for Liberal Jewish Learning, a major center for a Jewish adult education. Goldstein served as the first female president of both Reform Rabbis of Toronto and the Interdenominational Toronto Board of Rabbis.

She retired from Kolel in 2011 and founded the Inclusive City Shul in Toronto, where she still serves as rabbi. Her first book, ReVisions: Seeing Torah through a Feminist Lens, won the Canadian National Jewish Book Award in 1998. And her 2000 book Women’s Torah Commentary, which wove together insights from dozens of women’s scholars, has left an indelible mark on Jewish thought. And her book, New Jewish Feminism: Probing the Past, Forging the Future, was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award in 2008.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: When I was eight years old, my family moved from Seattle, Washington to a suburb of Denver, Colorado. And one of the very first friends I made in Denver was a Jewish girl named Laura. I remember jumping on her bed with her at her house. I remember this very clearly because I think it was one of my very first memories in Denver and one of my very first friends. So I really, really loved her. And as we were jumping on the bed, I don’t know how it came up, but we started talking about religion, and I remember very clearly her telling me all about the Torah and all about the Book of Life. And I actually have very vivid memories of what that seemed like to me in my mind, all the way back from when I was eight years old. And thus began my lifelong love and sense of kinship with the religion of Judaism.

Many of my closest friends throughout my life have been Jewish, and during college I chose to study abroad in Jerusalem for five months, where I studied Judaism, Jewish civilization, and the Hebrew language alongside Islam, Arab civilization, and the history of Palestine. I was also lucky to have several beloved Israeli American neighbors in Northern California. And finally, as I open with my personal connection to our topic today, I have to point out once again how many of the authors we’ve read on this podcast have been Jewish. From our very first authors that we read, Rianne Eisler and Gerda Lerner, through Betty Friedan, and Gloria Steinem, and Judith Plaskow, and others. I have been astounded at the contributions of Jewish women to the field of feminism and gender studies.

So it is with great enthusiasm and excitement that I introduced today’s book, New Jewish Feminism: Probing the Past, Forging the Future, and welcome to the podcast the editor of this book, Rabbi Elyse Goldstein. Welcome, Rabbi Goldstein!

Rabbi Elyse Goldstein: Thank you! Thank you so much.

AA: I’m so excited to have you here today, and I just want to thank you for this book. You wrote some essays in the book and then edited the whole thing, and I’m excited to hear about the process of how you put this work together. But first, I’ll just introduce you with your professional biography.

As one of the first woman rabbis in Canada, Elyse Goldstein has broken down barriers by founding inclusive communities for learning and prayer. Goldstein graduated from Brandeis University in 1978 and was ordained by the Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion in 1983. After ordination, she became assistant rabbi at Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto. Then sole rabbi of Temple Beth David in Canton, Massachusetts in 1986 before returning to Canada in 1991 to become founding director of Kolel, the Adult Center for Liberal Jewish Learning, a major center for a Jewish adult education. Goldstein served as the first female president of both Reform Rabbis of Toronto and the Interdenominational Toronto Board of Rabbis.

She retired from Kolel in 2011 and founded the Inclusive City Shul in Toronto, where she still serves as rabbi. Her first book, ReVisions: Seeing Torah through a Feminist Lens, won the Canadian National Jewish Book Award in 1998. And her 2000 book Women’s Torah Commentary, which wove together insights from dozens of women’s scholars, has left an indelible mark on Jewish thought. And her book, New Jewish Feminism: Probing the Past, Forging the Future, was a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award in 2008. And that’s the book we’ll be discussing today.

So again, welcome Rabbi Goldstein. And now I’d love it if you could introduce yourself a little more personally. Tell us where you’re from, a little bit about your background, and what brought you to do the work that you do today.

EG: Sure, thanks. It’s wonderful to be here with you, and it’s wonderful to be talking about this book, which I think is still so relevant, even though it was nominated in 2008. I feel like with modern politics a lot of us are saying, “are we still talking about this stuff?” But we still are, and it’s still very, very necessary.

So I’m originally from New York, so that listeners who are trying to place an accent can now place it, but I’ve lived in Canada most of my adult life. And I always make a joke that I converted to be Canadian. So I took out Canadian citizenship and feel very, very proud to be a Canadian and to be one of the first and I hope leading female liberal religious voices in this country.

What led me here obviously was my first job at Holy Blossom. But I felt at that moment in history, 1983 when I came to Toronto – and Toronto wasn’t quite ready for having a very public female rabbi with a very clear feminist agenda pro-choice agenda and a liberal agenda – I felt like that was my work. That was going to be my work. My work was going to be breaking that, I call it the stained glass ceiling, you know, breaking that stained glass ceiling. And I stayed! I did five years in Boston, as you mentioned, at Temple Beth David, and those were wonderful years. And I took a part-time congregation and turned it into a full-time congregation. But I came back in ‘91 because I still felt that this town and this country was giving me a great opportunity to advance a feminist agenda in the religious world as much as it was advancing it in the political world and in the secular world. So that’s, you know, that’s sort of what’s kept me here.

And I raised three Canadian kids, my husband’s Canadian, and I feel very comfortable here even though I retain a lot of my New Yorker sensitivities and also, you know, a little bit of that New York Jewish pushiness, which I think is very necessary here, to get things moving and to be seen as a little bit of a disturber of the status quo. It’s good to just lean back and say, “well, I’m from New York, what do you expect?”

AA: Love it. Hilarious.

EG: So, you know what got me to the rabbinate is really, I think, the most interesting part of my life story. So I was raised in a very, very active Jewish home. My mother was a very, very spiritual person, and in many ways, Amy, she should have been a rabbi. Of course, that wasn’t an opportunity that was open to her, but she worked for the Reform Movement, the national reform movement. She was the highest woman in her rank without being a rabbi. So she was the director of the National Youth Movement for all reformed synagogues. That was a huge job. She was the only non-rabbi in that area. And so she worked with hundreds of rabbis. So as a young kid growing up, my Sabbath table was populated by reform rabbis. You know, growing up they were the normative company in my house. And my mom would schlep me to marches on Washington against the Vietnam War that were being sponsored by this Jewish youth movement. So I thought, you know, to be Jewish meant to be active in the world and to change the world. And I saw these rabbis doing it, so it was only natural for me to say, I want to be a rabbi, I want to do this too. Nobody bothered to tell me in 1968 at my bat mitzvah that women weren’t rabbis yet. You know?

AA: You really literally didn’t know?

EG: I literally thought I want to be a rabbi. And at that moment, I learned the hard way that this was not an opportunity open to women. At my bat mitzvah, I ceremonially announced that I planned to be a rabbi. And it was just an unbelievable story. The rabbi fell off his chair and then got on his microphone. I was on the cantor’s microphone on the other side of the bimah, the altar. And he got on the microphone and he said, “no, no, no, everybody knows that what she means is she wants to be the rebbetzin,” which is the Yiddish word for the rabbi’s wife! And everybody laughed and I was on the cantor’s microphone so I said, “no, no, no what I mean is I’m going to be the rabbi and my husband be the rebbetzin.” Ha haha, everybody laughed. My parents were so proud, because as I say, I think my mother thought of herself as a rabbi, and to have a rabbi in the family and to have your young daughter say she wants to break this barrier.

So I just stuck by my guns there… and that was it! That was my public declaration of my desire to change history. And then I went on to high school, and I’ll tell you a very quick story. In our yearbook, my high school yearbook in New York, you had your picture, the most important club that you belonged to, and your future professional desire. So it would be like “Jason Goldberg, Basketball, Accountant”, whatever. So I sent in my picture, my name, and I was in choir so I wrote choir, and then I wrote rabbi. And the editor of the yearbook sent it back with the word “rabbi” crossed out in red ink and underneath handwritten, “No jokes allowed in the yearbook.”

AA: Wow.

EG: You know, this was still very raw, very new, very exotic. And I sent it back saying, no, no, no, this isn’t a joke. And they ended up printing it. I have that yearbook where it says “rabbi”. And the first female in the reform movement had been ordained in ‘73. So I knew about her, but I never met her. And she was just an image, she was an idea, she was a concept, she wasn’t real.

But it was later in high school, before I graduated high school, that I met Rabbi Laura Geller. She was in rabbinical school at the time, and she came to speak to one of my youth group kind of things. And that was it, I saw her in the flesh and I was like, “okay, this is not going to be hard.” Haha! This is not going to be hard, I thought. And then I went straight ahead. I went to Brandeis, I majored in Jewish studies, and then I went on to seminary and discovered that it was hard indeed.

AA: Why was it hard? Were you admitted easily or was that a process that you had to fight against some bureaucracy?

EG: Look, the interview process was the same for everybody except for women. So we were all asked the same questions as our male colleagues, but then we were asked the extra questions like: What happens if you get married? What happens if you have children? How are you going to be a rabbi with little babies?

Now of course they can’t ask that anymore, it’s against the law now. But I remember leaving the interview and going outside and seeing two of my male friends from youth group who were coming up next for their interviews, and knowing that they would not be asked that question. So they asked me, “oh, you’re single,” they said, “what’s going to happen if you meet a man in the middle of rabbinical school? Are you going to drop out?” Like, those assumptions were made. There were no women on the interview committee, by the way. It was all male rabbis on the interview committee and male professors. There were no female professors in school when I was there in the eighties. There are now, thank god. But it was a very male way of looking at the text all the time.

…to be Jewish meant to be active in the world and to change the world. And I saw these rabbis doing it, so it was only natural for me to say “I want to be a rabbi“

But you know, they asked you that question and it trips you up. That question trips you up and you have to either say, “no, I don’t care if I meet anybody, I want to stay single.” Or “yes, if I meet someone they’re going to have to deal with my being a rabbi.” You don’t want to talk about that, it’s very personal. You’re trying to become a rabbi and not talking about your personal life. By the time I interviewed for my first job at Holy Blossom, things had improved already, that was 1983. And so I remember the senior rabbi, Rabbi Dow Marmur of Blessed Memory, who was a great mentor to me, and a great support, and an advocate for me in a time when this town wasn’t quite ready. I remember him during the interview noting that I was single at the time, and saying to me – and I spoke to him many, many years later and thanked him so profusely for this and told him this is why I took the job – he said to me, you’re single. He said, “I’m not going to be your father nor your confidant, I’m your colleague. I don’t care who you date, when you date, how you date. I don’t want to hear about it. I don’t want to discuss it in staff meetings. And whatever you do in your private life is private.” That was it.

I walked out of that interview, it was like, please, please, please give me this. And when I was offered the job, I jumped at it. And for those years that I was at Holy Blossom, Rabbi Marmur was a great advocate for my feminist work, for my pro-choice work, for my political work. And when people would say to him, “oh, she’s very feminist” or “she talks about women too much” or “she shouldn’t talk about that,” he would say, “this is her passion, and I hired her for her passion.” So he was a great advocate. I miss him very much since his passing. I visited him every year in Israel when he moved to Israel after retirement. And he really in many ways cleared the path in Toronto for people to get used to the idea that I was a rabbi among rabbis. I was not a female exotic specimen in a zoo. I was a rabbi among rabbis. He worked very hard on that.

AA: Wow, that’s really beautiful. I’m really grateful you told that story. That’s incredibly inspiring. So, you talk a little bit about some of your process in the introduction of the book, but I wondered before we move more into the introduction, if you can tell us about why you wrote the book. What was that process like?

EG: I had written Seeing Torah through a Feminist Lens. It’s a very good primer, let’s say, to the ideas on concepts of Jewish feminism. I had felt that that was necessary. I was very moved by Judith Plaskow’s book, of course, Standing Again at Sinai, and Rachel Adler’s book, Engendering Judaism. And I just felt like I needed to take what I was teaching about Jewish feminism and make it available to a universal audience. By the way, for those listeners who are from Toronto, one of the great influences on me for writing the book was Michelle Landsberg, who I still am involved with. She was a great journalist and a great author, and a very important political figure in the eighties and nineties here. And she said, you need to take what you’re doing here as a feminist and you need to write it and get it out there. And then I wrote the Women’s Commentary and the Women’s Haftarah Commentary, which were for a more scholarly audience and for people that knew the Bible and wanted to do feminist analysis of Torah stories. And then my publisher came to me and said, we need one more, and we need you to cover all the changes in the Jewish world. Let’s call it “The Disruptions of Jewish Feminism”. And that’s why I wrote that fourth book.

AA: Okay, yeah. Well, I mean, I come from a Christian tradition, but I found it incredibly relevant for me too. And just fascinating. Every single article in the book was so, so interesting and illuminating. But yeah, let’s start with the essays that you wrote and contributed to the anthology. And so if it’s okay, I’ll just ask you some of my questions that I had as I read those essays.

So for the introduction, you talk about what you call a “quiet revolution” within Judaism that you say “grew louder and would eventually echo into the pages of the prayer book, the boardrooms of major Jewish organizations, the seminaries, the Yeshivas, and the Israeli government, all within the next twenty years.” I wondered if you can talk about that quiet revolution. You already talked about what the revolution was like in your personal life, but what was going on in Judaism more broadly at the time?

EG: So I can answer that by even talking about the changes I saw in seminary in the five years I was there. When I started in seminary, as I said, there were no female scholars, no female teachers. I still had a Bible professor who started every class with “Gentlemen, please open the text to Ezekiel” or Isaiah… Like, look right at the class. A third of my class was women. So, what I mean by a quiet revolution is just our being there. The very fact that we were in the room made people stop, look up, listen, and figure out that we need to change our language. In almost every class I took in seminary, the paper I would choose to write would be about women and whatever the topic was, right? And that made our professors start to notice that we were there, and that we had something to say, and that our voice was a different voice than had been heard before. That’s what I mean. But it was sort of quiet and then it got louder and louder. So, you know, we would start having more demands and we would start saying, we need to study women in history, or women in the Talmud, women in Jewish law. And we started to talk about this from our student pulpits. And so as it used to be– and by the way, I was still told when I was graduating in ‘83 to tone down the feminist references in my résumé. Not told by the congregations looking for rabbis, but told by the seminary. That doesn’t happen anymore. We had a special meeting just with the female students about what to wear to interviews. The male students did not have the same meeting with the dean. So that doesn’t happen anymore. And we protested. You know, we went to that meeting, but we complained! We said, this is ridiculous, we don’t want to be here and we don’t want to be told by male professors what to wear for interviews.

So the quiet revolution started to get louder and louder, and we began to understand that our voices were really critical to the Jewish project to hear. And as we took our jobs, we started to preach from the bimah about, for example, domestic violence against women being a Jewish issue, not a women’s issue. We started to preach about abortion and pro-choice as a Jewish issue, not a women’s issue. We started to move into the mainstream, what had been sisterhood events, or the Ladies Auxiliary. Women’s health, women’s mental health, we started to talk about parental leave instead of maternal leave. And we started to push onto the agenda of major Jewish organizations and our synagogues pay equity, not only for female rabbis, but for female executives of Jewish organizations. So that’s what I mean by the revolution got louder and louder and louder until it was felt everywhere.

And, I say even up into the boardrooms of Jewish organizations, JCCs, federations, but also we started to push this agenda in Israel. First of all, we started to have female colleagues ordained in Israel who spoke Hebrew fluently. And they started to change the whole scene in Israel in terms of the patriarchy, in terms of legislation that hurt women, religious legislation that in Israel became civil legislation. And so we felt that our influence could now be seen, felt, and heard across borders. And I want to say one other thing, Amy. It also started to be felt across denominational borders. Because even though we were Reform most of us, and then of course Reconstructionist, when Amy Eilberg was ordained as the first conservative female rabbi, she joined our ranks as, you know, disturbing the status quo. I think she was ordained in ‘85. She was ordained while I was at Holy Blossom, and I wrote articles about it in the Canadian Jewish newspapers about how thrilling it was. So then all of a sudden there were conservative women rabbis, so it wasn’t just a small phenomena of one movement. Today there’s already Orthodox women taking these titles.

AA: Wow!

EG: Yeah, of course! And so there’s Orthodox women who take the title rabba, you know, which is the feminine for “rav”, which is Hebrew for rabbi. And there are different places in the Orthodox world that are “ordaining” women. They might not call it ordaining, but certifying women to serve in rabbinic capacities. Who would’ve guessed that when I was ordained in ‘83? I felt that we were so alone in the world in a way, the few of us that were already in the rav. And today I think there’s between 850 and 900 female identifying rabbis in the reform movement. So from a third of my class being female to hundreds of us coming together for conventions, plus you have to add the female identifying rabbis from other movements, it’s a revolution. It’s a total revolution.

AA: That’s incredible. And I’ll just share one more quote to wrap up that topic. You wrote: “No Jewish woman today, even the most isolated or right-wing religious one, is free from the influence of feminism, even if just to have to justify her religious position.” So to me, when I read that I thought, okay you’ve moved it from the margins to the center. It has to be reckoned with. It’s not just a fringe issue anymore, is what I hear you saying.

EG: Exactly. It has to be reckoned with so much so, that I’ll suggest that although they would deny it, bat mitzvah is normative in the Orthodox community in its most right-wing factions even. Okay, the girl doesn’t go up to the Torah. Okay, the girl doesn’t read from the Torah. It might just be that she gives a speech at her home on a Saturday afternoon. But no one is free of the influence of Jewish feminism.

There’s not a Jewish organization or synagogue or denomination or movement in the world that doesn’t relate to Jewish feminism in one way or another. If only to say, “our women are happy exactly in the position they have, they don’t want any more. Those feminists are wrong!” But when you have to say those feminists are wrong, when you have to write articles defending your women against feminism, you know that feminism has won as a major force in the universe.

AA: Okay the next essay that I’d love to talk about is your essay that’s entitled ‘The Pink Tallit: Women’s Rituals as Imitative or Inventive’. So let’s start by having you acquaint listeners who might not know what the tallit is. Tell us about the vestments of a rabbi.

EG: Sure. And I’ll talk about all the rituals that have been “assigned” as male. So tallit is one of them. So, when Jews pray, they cover their heads. That article, by the way, called or kippah a yarmulka was also “assigned” as male, meaning only men wore it. That’s changed radically. Now, in the Orthodox world, women cover their heads for a different reason. They cover their hair to show that they’re married. But in the liberal world, women cover their heads for the same reason as men cover their heads, to show respect for the place that you’re at and also to say that there’s something above you, that you end at your head. You’re not the whole universe. And that’s why men wear it. So women have taken that on, and there are now women’s kippah, women’s fashion for the well-dressed attendee at synagogue. So it’s not just rabbis who wear these vestments.

And all Jews over the age of 13 are welcome to wear a prayer shawl called a tallit. It has four corners, and on the four corners are fringes that are knotted and tied in a special way to equal the number 613, which is the number of commandments in the Torah. Again, this vestment was “assigned” as male, meaning only men wore it. Women started wearing the tallit, I would say in the eighties. I already wore a tallit in the eighties. But today it’s common in reformed, conservative, reconstructionist. And I will tell you that even in Orthodox synagogues, there are women who wear the tallit. It is not something that people have never seen in their lives. So yeah, it’s one of those rituals that has moved into a space where people of all gender expressions, by the way, I should say, not just women and men, people of all gender expressions who are Jewish may choose to wear the tallit. It wraps you in the 613 commandments, and it changes you from wearing your “street clothes” to your “prayer clothes”. So those are not just rabbinic garments, but Jewish garments.

AA: Hmm, okay. In the essay you talk about feminine versions of what were traditionally masculine tallit. Do you want to tell us about the pink tallit? And I believe there was a really embellished tallit that you said reminded you of what a high priestess would’ve worn.

people of all gender expressions who are Jewish may choose to wear the tallit

EG: Right. So my experience with the pink tallit, I was once in Jerusalem and I was walking into a very religious Jewish vestment store, clearly a run-by-men-for-men. And in the window was a tallit with pink stripes. Now the traditional tallit has blue stripes or black stripes. Here’s a tallit with pink stripes, and maybe it had a little sequin work, I don’t know. It was very feminine looking, or let’s say traditionally feminine looking. And I walked in and I asked the very Orthodox male salesperson, “Who in the world would buy that pink tallit in your window?” And he said, “Oh no, that’s for girls having a bat mitzvah.” I looked at him and he said, “Not in my community, of course, just in yours.” So that really moved me. That moment really moved me to start thinking about what we do with these traditionally masculine garments to make them feel like they belong to us, to make them feel like we’re not honorary men wearing male garments. And I recognize, by the way, this is a binary way of looking at it, and I acknowledge that. But at the time, I really wanted to create a prayer garment for myself that would be something that I would feel was imagined as a traditionally feminine garment.

So I made an all lace tallit, so the tallit looks like what my grandmother’s tablecloth might have looked like. And then I put the fringes on it and a silver sequin crown, or atarah, the band on the top. And it’s great, and people stop me whenever I wear it and say it’s just beautiful. And then for my rabbinic tallit, for the high holidays, it’s a tradition for the rabbi to wear a white robe, or white garments. Especially on Yom Kippur when we try and identify as pure, right? And so I commissioned a Judaic artist in town named Temma Gentles to imagine with me if there had been a high priestess, instead of Kohen Gadol, what would she have worn? I’m talking about the biblical high priest. And we just created this flowing white thing with purple and blue, which were the high priest colors on the top, and bells that tinkled when I walked. And I love it. I wear it every Yom Kippur, it’s very special to me.

But I remember wearing it to a reformed Jewish congregational convention, it must have been in the mid eighties or late eighties, and the woman behind me poked me very aggressively on the shoulder and said, “What the heck are you wearing?” So it’s like, “I’m wearing a tallit that the high priestess would’ve worn.” And then you have to have that whole conversation.

AA: Yeah. Well, that’s fantastic too, right? Having the whole conversation is probably exhausting sometimes, but that’s the way culture changes is through those conversations sometimes, right? Being willing to have them.

EG: And the question is raised, do we want to imitate men? And this is a very important question. Do I want to wear a traditionally male-looking tallit and say to the world: This is what it looks like when it’s on me. This is normative. I am taking a normative Jewish practice, or a normative Jewish ritual or mainstream, or call it what you want, and I am putting it on myself as a female identifying person and you had better deal with that juxtaposition that you see in your mind’s eye. Or do I take this formerly masculine appearing garment and feminize it so that I say, “Hey, this is what a tallit would’ve looked like if women had been the voices designing it in the 16th and 15th and 14th centuries.” And I don’t have the answer to that. It’s a question I ask in the book. Should we be imitating or should we be inventing? And what’s the problem with each of those?

AA: Yeah. That was my main takeaway from that essay, too. And I thought it was really illuminating the way you presented the pros and cons of each one. One of the things that you said about the cons of this imitation is that, the quote that really stuck with me is you said, “They wrap us in male imagery making us honorary men for the moment.” That really hit me. I thought, yeah, I guess we get access to that male power, but it doesn’t dismantle the system as much to make clear the way for women to come into the system. It’s still a male system.

EG: Exactly. In a way, the pink tallit or the lace tallit or the high priests tallit dismantles the system and dismantles the assumption that a tallit looks like this white fabric with black stripes, because that’s the only tallit we’ve seen through our Jewish history as normative. On the one hand.

On the other hand, it still is a powerful moment to take on this formerly male understood garment, right? And wear it as a female identifying person, and say to the world, “Deal with it. This is what a Jew looks like.” Right? It’s the same thing as what we do as female rabbis all the time, right? On the one hand, we want to be identified as female and say this is part of our persona and part of our rabbinate. On the other hand, I want to be a rabbi among rabbis. So for example, when people constantly say “she’s a female rabbi” or “I’d like you to meet my rabbi, she’s female,” I ask them, when you introduce a male rabbi, do you say the same thing? Do you say “my rabbi’s male”? Oh, my doctor’s a man. Oh, my car mechanic’s a man. No, we only point it out when that unexpected surprise is that the person is female identifying. And that doesn’t dismantle the system.

I need for us to start saying “my car mechanic, you know, he’s male, right?” To make people surprised at the fact that we even notice that. Why do we notice gender only when it’s female identifying? We still say, oh, there’s a female bus driver, right? Or whatever. It continues to problematize the constant attention to gender in a binary sense, for sure. But now I think also in a non-binary sense, people are constantly talking about a person’s gender expression or a person’s gender identity. It does affect you after a while. From just doing your job, just doing what you want to do when you’re constantly explaining your gender identity to the world.

AA: Mhmm. So another question that I had from this essay was about inventive ritual. And I was very moved by this moment that you talk about where you took a woman to the mikvah, which is a ritual bath, after a rape. And you were confronting this very new situation and asking, you know, what ritual shall we do? What prayers will we say? Can you talk about that a little bit?

EG: Sure. I think that what has kept Judaism alive, against all odds – since the destruction of the temple when really everything we knew about Judaism had to change, we had no more animal sacrifice, no more high priests, and no more temple. So every other ancient religion faced with that crisis disappeared. And we in our brilliance said, you know what? We’re just going to readjust. We’re going to readjust Judaism to live in a diaspora and to have no temple and to not do animal sacrifices. What are we going to do instead? We’re going to do prayer instead of animal sacrifices. Instead of the one temple in Jerusalem, we’re going to have local synagogues. Instead of the high priests, we’re going to have rabbis. That’s how we survived. So, I truly believe that what has kept Judaism vibrant, not only alive, but really, really vibrant, is its adaptation to the feminist way of perceiving the universe. And the gender conversation altogether. And so through this feminist revolution we’ve come to recognize that not only the voices of women have been missing, but the lived experience of women, menstruation, lactation, childbirth, menopause has been missing from our canon of liturgical and experiential possibilities.

So yes, I think being inventive is what has kept Judaism alive. And I’ll give you the best example of this, I think. The modern state of Israel, let’s not talk about its politics right now at this moment, let’s just talk about what it means to have a Jewish homeland again, which has to readapt to not being a diaspora. Has to readapt its Judaism to being a 21st-century Judaism that works for everybody. And so it’s a very vibrant Judaism that we have now. And even the denominations, by the way, they all invent. They all invent ways– even though I said the Orthodox bat mitzvah is a kind of an invention. And all these inventions are answering the feminists’ critique, which is: Hello! We’re here! You need to draw us in.

Because I can tell you the truth, more women have said to me over the 36 years of my rabbinate, “I came back to Judaism because of feminism. I had left, I had felt unwelcome. I had felt unheard. I had felt invisible.” And look, that’s 50% of the Jewish people, and what an enrichment it is for us to have those women back.

AA: Can you tell us a little bit, because you had mentioned the rites of passage and the landmarks in a biologically female person’s body of menstruation and lactation and menopause and all of those things. And I loved that conversation in your essay. And then you also point out that as women invent new rituals, there’s some cautions that you have for women about not just assuming heterosexuality, for example, and childbearing as the norm. So can you talk about some of the dangers that you point out in creating rituals that are based on those?

EG: Absolutely. Look, I say in the book and I’ve said this before: Biology should not be spiritual destiny. So when I first started this enterprise of being a rabbi, I believed that a woman’s body or a man’s body shouldn’t dictate what they can and cannot do religiously. That’s true now of people who gender identify differently than male or female. That we are all spiritual beings, right? First and foremost, we are spiritual beings that are housed in a body, okay? If we are spiritual beings that are housed in bodies, then our bodies are secondary to the spiritual endeavor. So we have to be careful if we invent rituals. And I don’t care if we invent them for women, or whether we invent them for people who are trans, whether we invent them for people who are non-binary, we have to be careful not to neglect the soul on behalf of the body. And say your body determines what your spirituality is going to be. It’s a tightrope because on the other hand, your body does in many ways determine your spiritual life and your soul. So I don’t want to negate that, but I also don’t want to make it so primary that someone who doesn’t feel embodied in their spirituality feels left out.

So when we started to do rituals for lactation and childbirth, for example, or menopause, we became aware that we were excluding a lot of women who were either by choice childless, or childless by circumstance, or not married, or not partnered, or didn’t want children, or whose life with their children was not the joy that they had expected, or who lost children, or who miscarried, we realized that they were not resonating with this universally assumed ritual. So then we had to think about rituals for miscarriage, right? Rituals for separation, those kinds of things. And then you get to a point where you need a ritual for every moment in your life, basically. And it can become overwhelming where your life becomes so ritualized that it feels a little bit over the top.

AA: So I do have this question now that I hadn’t thought of before, but would a congregant, let’s say if someone does have a miscarriage in your congregation, would she come to you and say: I feel a need for a ritual to mark this event in my life and process it in a spiritual way? Could you help me come up with something? Or how does that happen?

EG: Well, I would offer. If somebody tells me that they’ve had a miscarriage, I would say, is there something we can do together spiritually? That’ll make you feel grounded, give you some spiritual strength. But she’d have to come to me and tell me she had a miscarriage. But this is what I do. This is how the person who was raped got to the mikvah. We said together, what’s a traditional Jewish ritual that can help give you spiritual strength? And we thought, well, the cleansing waters of the mikvah could be used. And it was a very inventive ritual. Subsequently I’ve brought many people to the mikvah for spiritual cleansing rituals, like after infidelity in a monogamous relationship, or after the death of a loved one. The mikvah is an amazing ritual. So, I think the more open we are to using traditional rubrics for modern reasons, the more we’ll find ways to be inclusive. So yes, congregants have come to me for all sorts of things and said, “is there something we can do Jewishly to mark this?”

AA: Wow, what a beautiful way to spend a life. It’s just striking to me, to be in that role in a community, I just admire and think it’s really inspiring.

EG: Thank you so much.

AA: Okay, my last topic that I wanted to ask you about is an essay that you didn’t write, but it’s in the anthology. It’s called ‘A Thirty Year Perspective on Women and Israeli Feminism’ by Rabbi Naamah Kelman. Can you talk a little bit, especially since this season is kind of a geographical study of patriarchy, I’d love it if you could mention some of the topics in that essay and talk about gender in Israel a bit.

EG: Sure. I think Israel plays a unique role in Jewish consciousness. I’m very aware of the very profound political tension that right now exists as we’re speaking. But with all that, Israel still plays a central role in Jewish consciousness. And I think we can start from the very basic perspective that women serve in the Israeli army. And that’s going to change the perception, or the machismo perception, of the Israeli soldier altogether. And women have fought very hard to climb the ranks in the Israeli army, which is very important. And so you get your first female pilot, you get your first female fighter, and women are now in combat units in the Israeli army. And I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing, you know, because we want to fight militarism, and especially as a feminist see its origins in male domineering and the male way of looking at the world, which is: it’s my team or your team, and only one team can win. But being a country which needs a military for its own protection, it was clear from the get-go that women were going to join the military and be drafted alongside men as an obligation.

So Naamah in her essay talks about how having women in the army changes the whole army structure and calls to question some machismo assumption in the country. That’s number one. Number two, I think reform rabbis are a bit of a novelty in Israel. The Orthodox hegemony is very strong, although they are not the numerical majority, Orthodox Jews wield a lot of political power in Israel. That is something the reform movement fights day and night and actively and passionately. But having female rabbis has changed the landscape in Israel as much as it’s changed the landscape here in the diaspora. Meaning that when you have an assumption in a country that orthodoxy is the norm, that assumption is questioned every day by having female rabbis on television, by having female rabbis perform bar/bat/b mitzvahs, by having reform female rabbis perform weddings. Everybody including the most orthodox Jew in Israel has now seen or heard of a female rabbi. And it’s really important that they’re not rabbis in the diaspora. Because it’s easy to dismiss and say, oh, that’s a fad in Canada. That’s a fad in America. No, no, these are Israeli-born, Hebrew speaking, native Israeli female rabbis. So no one can say, “oh, they were raised in the United States, they saw a different kind–” No, no, no, they were raised in Israel. And so they’ve changed the landscape very much.

And of course, women in the Supreme Court of Israel… What happens is when you have a country that still sees its rulers as religious leaders, you’re going to have to change your assumption about the way the country is run once women take high roles in all of that. And that’s what Naamah was talking about, and that’s what’s happened in Israel as well as here.

AA: So one thing that I observed even just when I studied there when I was in college, and then when I would read different things in the decades since, is observing a really wide variety, to be honest, and almost diametrically opposed forces it seems to me. So, correct me if I’m wrong, but we did some volunteer work on a kibbutz when we were there, and the egalitarian tradition of the kibbutzim was really striking. Men and women doing all the same stuff like working on the farm together, doing all of the housework together, that seemed extremely progressive. And that comes from the founding of Israel. But at the same time, then you have the more traditional Orthodox communities that are very gender segregated and very, very patriarchal and insulated. And so does that tension and those two kinds of influences, they still exist in Israel, right? And how do they interplay with each other?

EG: Oh, listen, it’s very alive. For example, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem are almost like two different countries. Secular Tel Aviv is, I would say the rest of the country except for Jerusalem, is kind of based on that founding ideology. The founding ideology which was socialist, egalitarian, democratic, liberal. There’s no question that Israel’s founding ideology was all of those things: liberal, democratic, egalitarian, striving for democracy, striving for equal rights for all of its citizens. And within the gender question, equal rights for women was a given! It was a total given, long before women had the right to vote in the United States, the first Zionist Congress gave women the right to vote at the first Zionist Congress in Basel in 1890-something. So there’s no question that the founding principles of the state of Israel were egalitarian.

As the religious right gained not only power, but also demographic power – they have more children – those values began to be questioned. The truth of the matter is the vast majority of the Israeli population holds strongly and passionately those values and sees the religious hegemony as not mainstream and fights it. You know, the question is, can we fight on all fronts while we’re also fighting our own security? So it’s a very complicated country because of that, because it’s got all these political issues, economic issues, and it’s got its own internal issues about citizenship, about the rights of Palestinians, the rights of minorities, Palestinian Israeli Arab citizens. It’s got a wide variety of the kind of people that call themselves people who live in Israel. The vast majority of people who identify themselves as Israeli also identify themselves as democratic, liberal, and egalitarian. And you can see this, by the way, in the way the courts run. You can see the amount of women judges, women supreme court judges, women in the court system, women doctors, female-identified members of Knesset. You can see this very clearly. It’s a work in progress. I always say to people, and this doesn’t excuse any political events that are troubling to everybody including me, but I always say to people, this is a country that was founded only 75 years ago by a traumatized group of Holocaust survivors. It’s going to take some time. It’s a work in progress. So egalitarianism is also a work in progress that we’re all watching carefully and working toward.

there’s no question that the founding principles of the state of Israel were egalitarian

AA: Yeah, well that was one of the really interesting things in this essay for me, was that back and forth of more Orthodox forces gaining strength for a little while and then feminist forces fighting, for example, to have a non-orthodox wedding ceremony. That was one of the things that was contested.

EG: Even since Naamah’s essay, by the way, even since her essay women have been pressing in the Orthodox world to be named as authorities for religious institutions in towns in Israel. So there are now Orthodox women, they might not be called rabbis, but there are Orthodox women in charge of, for example, kashrut or the mikvah, or things that normally would only be allowed to be controlled, certifications by men. There are now women. So even within the Orthodox community in Israel, as I said to you, feminism touches everybody eventually. Even in the Orthodox community in Israel, women are starting to take what I would call religious leadership roles, and you start to see that as normative.

AA: The last question about that though, is even with the shifting to the right that’s happening right now, are feminists worried about that? Is that going to now create some backsliding in terms of women’s rights in Israel? Are people bracing for that?

EG: Nobody’s bracing for it because liberal forces will not allow it to happen. And I feel a hundred percent confident about that. And I have to feel a hundred percent confident about the rest of the world which is sliding to the right. The entire world. I look at the United States to the south of us and it scares me. With the rise of the fundamentalist evangelical religious right that also has some issues around women’s roles and the right of women to control their own destinies. So I look at the whole world right now moving very fast towards the right, which is always bad for women. I don’t care what the religion is. The entire world moving right is going to be bad for women. Fundamentalism, I don’t care whether it’s Christian or Muslim or Jewish. Fundamentalism is bad for women. Many people might disagree with me, but that is as clear as a bell to me. And so all of us need to be active voices for liberalism against the push to make fundamentalist voices the religious voice that everybody hears.

AA: Hear, hear. Well, that brings us to the end of the episode, Rabbi Goldstein. And again, I’m just so grateful to have you here. And I’d like to ask if there’s anything that you’d like to leave with listeners before we wrap up.

EG: Thank you, thank you for that. It’s been a pleasure. Yes, I do. I always end my talks and my books and my presentations about the disruptions or the revolution of feminism by saying the following: It’s like pushing an iceberg. If you push an iceberg, you have no idea how far it’s gone until you go back to the shore and you look at it from a distance. So in 1983, if you had told me how far the iceberg will have moved in 2023, I never would’ve believed you. I would’ve thought, “I am pushing this thing so hard. I’m alone pushing this thing. It’s so big it’ll never move.” Now maybe iceberg isn’t a good metaphor anymore because of climate change, so say tremendous boulder, whatever it is. And then you step back on the shore, and first of all, you see how many people have been pushing it with you. You thought all along that you were pushing it by yourself, but you didn’t realize it’s moving way faster than you thought it was moving because people have been pushing it with you. So that’s the first thing you see when you go back to the shore.

And the second thing you see is, you are astonished and grateful. You say to yourself, look at how far it’s gone. So it’ll just keep moving because there’ll be people with me and after me that continue to push it. So I’m extraordinarily grateful to know that since I decided in 1968 to be a rabbi and everybody thought it was a big joke, ‘til today when there’s like hundreds and hundreds and hundreds– and any young girl listening to this podcast will say, “of course, I can be a rabbi, who would ever think otherwise?” That is a miracle, and I’m very grateful to be living in this time when it happened.

AA: I’m sure all of those girls and women within Judaism, and honestly even from outside it, are grateful for the work that you did pushing that iceberg so that the changes have happened. I’m just so inspired. I’ll also recommend to listeners, if you’re interested in Jewish feminism, your book was fantastic. Again, it’s called New Jewish Feminism: Probing the Past, Forging the Future. I highly recommend purchasing it or checking it out from the library and reading it. And again, Rabbi Elyse Goldstein, thank you so much for being here today.

EG: Thank you so much. It was wonderful.

I was not a female exotic specimen in a zoo.

I was a rabbi among rabbis.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!