“there are such things as enlightenment; the courage to change; emotional, mental and spiritual evolution; and, therefore, hope for the future.”

From the very beginning on this project it has been our belief that the unjust construct of patriarchy causes harm to people of all genders, including men. On today’s episode we’re joined by a deep and generous thinker, Bob Rees, who interrogates that belief and unpacks some specifics of both how patriarchy can painfully impact men as well as some of the ways men, and patriarchs even, can act as our allies in this work of dismantling oppressive structures. Along the way, Bob recites poetry, offers thoughtful insight, and reflects on his personal history surrounding trauma and abuse.

As a note to listeners, be aware that this episode contains discussion of sexual harassment and abuse. Please be kind to yourselves and take care accordingly.

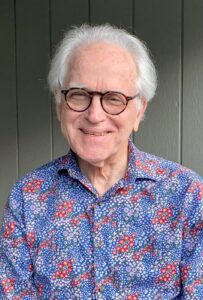

Our Guest

Bob Rees

Bob Rees (he/him), is an activist scholar, poet and humanitarian. He is a Visiting Professor and Director of Mormon Studies at Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Previously, he taught at UCLA, UC Santa Cruz, and UC Berkeley. He is the co-founder of the Bountiful Children’s Foundation, which addresses malnutrition among Latter-day Saint children in the Developing world.

To learn more about Bob and his work to wipe out childhood malnutrition, be sure to visit the Bountiful Children Foundation.

Patriarchy & Me: A Personal Perspective

Even before I was born, my life was shaped by patriarchy in both general and specific ways. In a general sense, it began millennia ago when, recognizing their superior physical strength and freedom from childbearing, men began to lord it over and dominate women, exercise control over property and capital, and, when they were threatened by the mystery and power of feminine deities, began to insist on the exclusivity and superiority of masculine deities. This heritage was influenced by the generations of men from primitive times to the present who continued those ancient enmities, inequities and imbalances between men and women.

In a specific sense, patriarchy in my life began during my infancy, gained prominence during my formative years and left a shadow that as an adult I have had to recognize and address. Let me explain: My mother, Ona Marie Hardin, was always something of an enigma to me. Growing up, I witnessed her being abused and bullied by the men in her life, including my father and a series of stepfathers. While she wanted to be a good mother, poverty, alcoholism, and depression inhibited her from being so. She abandoned my brother and me when I was still an infant and again when I was eight. I never lived with her again and only saw her infrequently.

It wasn’t until after her death that, at age fifty, I learned the reason for her brokenness. On a visit to Colorado to visit my grandmother and my aunt, I learned that my mother had been sexually abused by her father, starting when she was a young girl and lasting into her teenage years. Thus, before she even had a chance to fully develop emotionally, her psyche was deeply damaged. With that revelation, my mother’s life suddenly made sense to me for the first time. Later, after seeing a photograph of her with her high school class, I wrote the following poem.

Ona

That’s her, standing somewhat stiffly

with the others in Rye, Colorado,

the year of the Great Depression.

Her cousin Mavis is there too,

third girl from the left.

She looks more poised

than my mother, who stands

in a corner, her passive face

lit like a cameo.

By this time, her father was already fondling

her breasts, which are just beginning to

show beneath the cotton middy she wears

with the sailor collar. He caught her

in the barn where they milked the cows

and in the creamery when she made butter.

At fourteen she was sent to live

with her Aunt Ida in Cortez, making

the trip over Wolf Creek Pass

on the darkest day of the year.

Two years later she and my father ran

away to Monticello to get married.

When she was seven months pregnant

with me, her second child,

she drank a bottle of blue poison.

Her second husband shot a woman

then cut his own throat with a razor.

Her third husband died in a fire

a year after he raped her. For

a while she lived with an ex-

convict and then married a guy

named Birchell O. Eden.

Her fifth marriage was to her

own daughter’s third husband.

Not long before she died of heart

failure and he was killed by a car

while crossing the street in Delta,

the old man was still pressing her.

The other boys and girls in the picture

look innocent, expectant, dreaming

of girlfriends, boyfriends, basketball

and dresses for the school prom.

My mother alone casts a shadow

on the pastoral backdrop hung clumsily

by the photographer, who cannot see

what she knows and can never tell

anyone, especially her classmates

standing so full of promise before

the black, one-eyed box.

My grandfather’s unforgivable and violent abuse of his role as father, nurturer and protector deeply wounded my mother and therefore wounded me.

The absence of a mother left me feeling at times like a motherless child. That feeling was deepened by having three stepmothers, none of whom was nurturing in the way I needed, and one of whom was both physically and emotionally abusive. I later came to understand that she also had been abused by her first husband.

The men in my family were typical of the sexist culture in which they were raised. As a boy I saw both my father and other men verbally and sometimes physically abuse their wives and other women. There was almost no sense of equality in the marriages which led to men wielding authority like the weapon it was.

…patriarchy in my life began during my infancy, gained prominence during my formative years and left a shadow that as an adult I have had to recognize and address.

Whereas my stepmothers were either abusive or indifferent, my stepfathers were often violent–with both my mother and her children. My mother’s second husband was an abusive man. While still married to my mother he either murdered a woman and committed suicide or, more likely, was a victim of a double murder. My mother’s third husband raped her while her three children (ages four, six and eight) were in an adjacent room. Later, as a seven-year-old, I witnessed the woman next door pounding on our door to escape her husband’s wrath. Before we could respond, he sprang onto the porch and hit her in the face, knocking her onto a huge rock, where she hit her head.

Alcohol troubled the lives of all these people and because of it they troubled the lives of one another and of the children in their care.

The best thing that could be said of my childhood is that what I experienced caused me to turn away from and against it, although it has taken years and much conscious effort to shed the negative masculine modeling I witnessed and its effect on my development. Ironically, it was also a patriarch who helped me in doing so.

In the Mormon church there is an ordinance called a Patriarchal Blessing. In this practice, a high priest who has been specifically called and set apart as a Patriarch, gives special individual blessings to members of the Church, somewhat in the way that Abraham, Isaac and Jacob gave blessings to their sons (although not their daughters). Latter-day Saints believe patriarchs have unique gifts that allow them to look into the souls of those they bless and even see into their futures.

When I was fifteen, my father and his second wife divorced, and because my father was estranged from the Church, some friends from my local congregation took me to Mesa to meet a patriarch, Alma Davis, who was a complete stranger. After a few minutes of getting acquainted, he laid his hands on my head and said the following words:

“The Lord has blessed you with very sensitive feelings. Be thankful for these sensitive feelings, dear brother, and at times when you have been sorely hurt and have wished you were not so easily touched and hurt in your feelings, be thankful be for them. These sensitive feelings will lead you into paths of truth and righteousness. In seeking after the finer and better things of life, great will be your joy and happiness. . . .

Dear brother, let your experiences of the past be as a teacher to you, to teach you those things that are worthwhile. Those things that are worthy, and the finer and better things of life as contrasted against those things which confuse, those things which tear down, those things which take the joy out of life. Dear brother, put these things behind you. The Lord blesses you to go forward.”

I saw both my father and other men verbally and sometimes physically abuse their wives and other women. There was almost no sense of equality in the marriages which led to men wielding authority like the weapon it was.

There was certainly nothing in my family culture or experience that could have been classified as the “finer and better things of life.” The Patriarch’s blessing went even further: he admonished me to “develop these beautiful gifts and talents with which he has blessed you, the beautiful in music, the beautiful in thought, the beautiful in literature and the higher and finer things of life,” all of which were as foreign to me as Greek or Latin, and yet, as it turns out, the very things that have defined and characterized my life, both personally and professionally for the past sixty-five years.

As I look back on my life, I can see that the most important turning point happened when I was ten and my father, just returned from the Second World War, rescued my brother and me from the foster home where we had been placed when our mother abandoned us. Related to that was my father’s recent conversion to Christianity, specifically Mormonism, which led to my learning for the first time about God and Christ and what Latter-day Saints refer to as the Restoration, a series of theophanies, revelations and other experiences that led to the establishment of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or the Mormon Church. That gave me, for the first time in my life, both a stable grounding and a safe and nurturing place. It also gave me the conviction for the first time in my life that I was loved unconditionally. That conviction, which has never left me, has been enormously grounding.

Although I was only ten when all these new ideas and possibilities poured into my young mind, they constituted, as I look back, an awareness that they were good and true and beautiful, and that they were like roses blossoming in the Sahara of my spiritual awareness and awakening. As I have grown in my spiritual understanding and as I have sought to become a true disciple of Jesus, I have become increasingly aware of two important things relating to patriarchy: 1) I am a privileged white American male, and 2) as such, I have a responsibility to make the world both more equal and more equitable, including in relation to the imbalances between men and women.

I recognize that my Latter-day Saint maleness has given me special privilege. As a holder of an all-male priesthood, I have held many positions of power and authority and been given many rich opportunities and experiences not available to women. That, in turn, has led me to be increasingly aware of the imbalance of power between Latter-day Saint men and other men, and Latter-day Saint men and women.

Religious institutions, especially those with a dominant or predominant male ecclesiastical authority structure, may be particularly vulnerable to the abuses of patriarchy. I have certainly experienced that in my own faith tradition where bishops, stake presidents and other leaders at times invoke their authority to silence opinions or positions with which they disagree or of which they disapprove. At times this can lead, as it has on occasion with me, to ecclesiastical abuse, including censure and sanctions. Such actions can be injurious to those subject to them.

…it has taken years and much conscious effort to shed the negative masculine modeling I witnessed

I have also been negatively impacted by patriarchy in society. In the academic world, where I have spent my entire professional life, I have encountered superiors (and some not so) who took an inappropriate superior and sometimes arbitrary, discriminatory and punitive position in regard to me. That is also true in other arenas such as health care and business. I also recognize that at times I have suffered from the same patriarchal proclivity!

The second most important influence in my life after Jesus and my religious community has been my good fortune in being married to two extraordinary women, Ruth Stanfield and Gloria Gardner, both of whom have challenged my patriarchal past, attitudes and behavior, been generous in forgiving my chauvinism, have taught me how to see the world through their eyes (to whatever extent that is possible), and, most importantly, have taught me how better to love God, them, others and myself, an on-going work I expect to last to the end of my life.

When Ruth Stanfield and I got married in 1961 we were both in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin. As a newly married couple, we were warned about using contraception or otherwise delaying having children. One leading Church apostle, warned, “Those who practice birth control . . . are running counter to the foreordained plan of the Almighty. They are in rebellion against God and are guilty of gross wickedness”; and “Those who practice birth control will reap disappointment by and by.” Given today’s cultural and social values, it is hard to imagine a church leader giving similar counsel.

Since Ruth and I both strove to be obedient, we followed this counsel, which resulted in Ruth’s getting pregnant on our honeymoon! As it turned out, we had three children by the time I finished my graduate studies. Ruth, who was a brilliant scholar and who had a prestigious graduate scholarship, never finished her Ph.D. Although we had been eager to begin our family, we both regretted that we didn’t stay until she had completed her degree. Later, when our children were in school, Ruth enrolled in the Doctor of Musical Arts program at USC, but then interrupted her studies once more, this time to care for her and my elderly parents. That decision too was influenced by patriarchy.

One of the unfortunate results of what in retrospect were the effects of a patriarchal system was Ruth’s struggle with depression. I believe Ruth’s emotional and mental state would have been much happier and healthier had we exercised the common sense in relation to family planning and other matters that many Latter-day Saint couples do today.

After fifty-one years of marriage, Ruth passed away in 2012. Six years later, I had the good fortune of marrying Gloria Gardner. Like all women, Gloria too has been negatively affected by patriarchy, and like many women she has transformed such experiences with courage, humility, and the persistence to awaken within her authentic self. Gloria has been a forthright and loving wife, teaching me with calm practicality how better to relate to her and to other women–as well as to men and children.

One of the beautiful blessings in my life are the two daughters Ruth and I raised, Jenny and Anna. I see in them many of the same gifts and strengths their mother possessed. They are strong, independent, competent women and each has taught and continues to teach me to recognize my privilege and to be less patriarchal. I see these same gifts and virtues in Gloria’s two daughters, Ari and Zoe, and in our granddaughters. Gloria and I are both grateful that our sons and grandsons belong to a generation more enlightened in relation to patriarchy than our own was. Thankfully, there are such things as enlightenment; the courage to change; emotional, mental and spiritual evolution; and, therefore, hope for the future.

I recognize that I still have important work to do with regard to patriarchy. What I have come to believe in is the possibility that we can all work toward seeing one another as God sees us— as alike and undifferentiated in terms of our potential, value and worth, yet distinctive in our paths and talents. That is our shared work as human beings. As long as one man feels superior to one woman or one boy feels smarter than one girl; as long as one woman feels she must seek shelter from an abusive male; as long as one girl or woman is sold into sexual slavery; as long as one father of an infant girl is disappointed in her not being a boy; as long as one woman is paid less for doing the same work as a man; as long as women are valued for their sexual characteristics, rather than revered for all of their characteristics; and as long as we fail to see deity as being both feminine and masculine – in other words, until “patriarchy” becomes an obsolete and antiquated word — we all, especially men of privilege and power, have essential work to do. The really good news is that such work can be done in, with, and through love. Love can guide, sustain, refresh and renew us; it can help us overcome our own ignorance, surrender our pride and shed our outmoded destructive cultural overlays. Ultimately, it can nourish us as we find ourselves moving closer to one another and therefore toward the oneness we were created to achieve.

in, with, and through

love

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!