“playing the patriarchy at its own game”

Amy is joined by author Kathy Iandoli to discuss her book, God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop, exploring the incredible history of female pioneers in hip-hop history from old school crews like The Mercedes Ladies to contemporary superstars like Lil’ Kim.

Our Guest

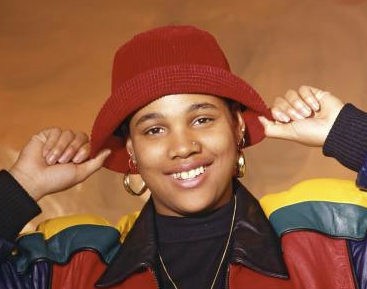

Kathy Iandoli

Kathy Iandoli is a critically acclaimed journalist, author, podcaster, media coach, and documentarian. She has nearly 25 years experience working in the music industry—from media, to publicity, radio, and artist management. Her first book, God Save The Queens: The Essential History of Women In Hip-Hop was named an NPR Best Book Of the Year. She is the author of the biography Baby Girl: Better Known As Aaliyah, as well as the co-author of rapper, Lil’ Kim’s memoir, The Queen Bee. Kathy has written about music and gender for two decades, with bylines in VIBE, The Source, XXL, Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Billboard, Pitchfork, BUST, Teen Vogue, PAPER, Playboy, i-D, Cosmopolitan, Maxim, The Guardian, VICE, and many others. Kathy was a professor-in-residence of Music Business at NYU for 7 years as well as an alum of Steinhardt’s Music Business Graduate Program and has served as a pundit (television, radio, and panels) for discussions on hip-hop and gender.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Since its invention in the 1990s, hip-hop has taken the music world by storm. In fact, according to an end-of-the-year Nielsen report, it was in 2017 that hip-hop officially overtook rock music to become the most popular genre in America, and it’s remained firmly in that top spot ever since, with hip-hop accounting for over a quarter of all music streaming each year for the past seven years. So whether you’re a diehard fan or have only heard a track or two on the radio, there is no denying that hip-hop has massive sway over our culture. And like so many of our cultural institutions, it’s had its history of sexism plus remarkable women who have fought against that sexism. In a 2024 Forbes article listing the 50 top rappers of all time, only eight women were included. That’s only 16%. And that is not because there aren’t women in hip-hop. There is no shortage of history-making female artists that they could have included. It seems that just like in other institutions, women’s history and accomplishments have been largely overlooked, which is why I am so happy to be discussing the book God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-hop by Kathy Iandoli. Iandoli’s book isn’t a dictionary of artists or a quick reference guide, it is a well-researched and thorough history. And more than anything, this book is a celebration of women in hip-hop, their talents and hardships and incredible achievements. I’m so excited to be discussing this book today with the author of God Save the Queens, Kathy Iandoli. Welcome, Kathy!

Kathy Iandoli: Thank you!

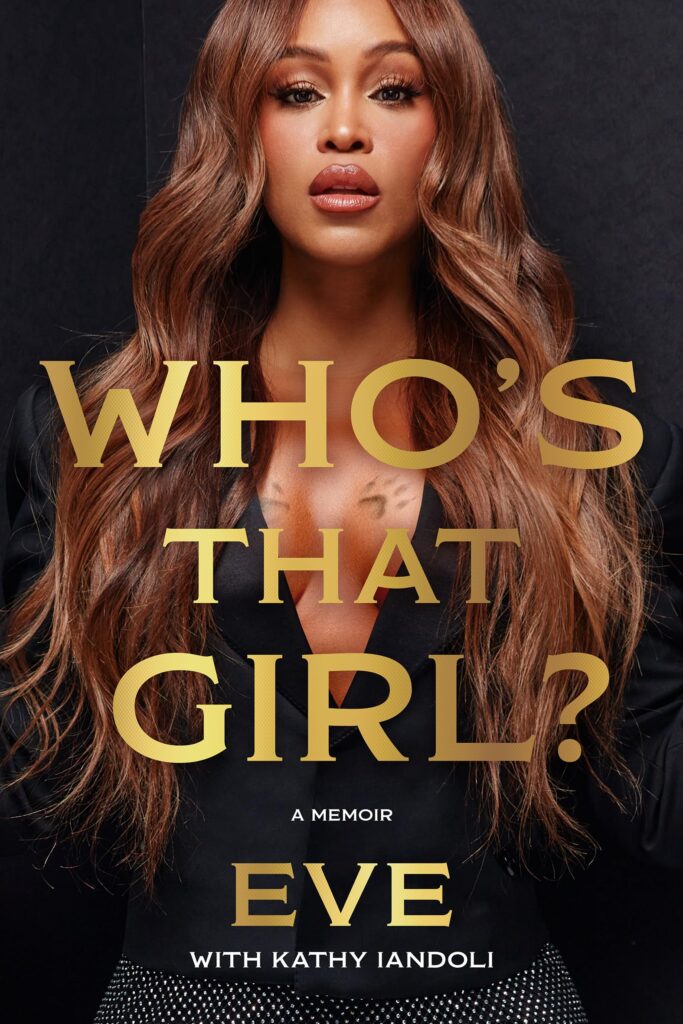

AA: I’m so excited for this conversation. Kathy Iandoli is a critically acclaimed journalist, author, podcaster, media coach, and documentarian. She has over 25 years of experience working in the music industry, from media to publicity to radio and artist management. Her first book, God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-hop was named an NPR Best Book of the Year. Huge congratulations on that, that’s awesome. She’s also the author of the biography Baby Girl: Better Known as Aaliyah, as well as the co-author of rapper Eve’s memoir, Who’s That Girl? and Lil’ Kim’s upcoming memoir The Queen Bee. Kathy has written about music and gender for two decades with bylines in Vibe, The Source, XXL, The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Billboard, Pitchfork, and many others. Kathy is a professor of Music Business at NYU, as well as an alum of the Steinhardt’s Music Business graduate program, and has served as a pundit for discussion on hip-hop and gender. That’s the tip of the iceberg, the professional bio, but I’d love you to talk a little bit more about where you’re from and what brought you into the industry and the work that you do today.

KI: I’m from New Jersey, and it’s interesting because when I think about how I ended up here specifically, like with the 15 different jobs that I do, I think that it most definitely boiled down to music. I come from a musical family. My mother was a pianist, my father plays the guitar, my grandfather played the mandolin, I had an uncle who was in a rock band, so I definitely had music all around me, but I wouldn’t necessarily call myself a musician. I mean, I could play some instruments by ear, I can play the piano by ear and I attempted to take guitar lessons for about five years, but it was always just me wanting to learn power chords, like, “Can I learn how to play Nirvana?” Ironically enough, I taught myself how to play Eve’s Gotta Man and Let Me Blow Ya Mind by ear, and that is my big hip-hop-meets-guitar achievement.

AA: I love it.

KI: I talk about this actually with my students, this is a funny story. I went to the bookstore, I was maybe, I don’t know, ten, and I found this book that was titled something to the effect of “Every Possible Job You Can Have in the Music Industry”. And I don’t know why I was thinking about this at ten years old, like, “All right, you need to think about your career path.” So the book begins with record store clerk and it ends with CEO. And I said, “Okay, that’s how I’ll get started.” So as soon as I got my working papers, I started working at a record store. And I think about this because I have so many students at NYU who are like, “What am I going to do?” And I’m like, “I wish that book still existed. Maybe I’ll rewrite it.” But the book showed you how much money you could make, and I remember back then it was like $5 an hour and I was like, “Whoa, that’s just banking!” So I started at a record store as soon as I got my license.

When I was in college, I started working with The Roots, hanging posters, handing out flyers, helping organize their Black Lily concert series. And it was during that time period where I was very much into this idea of “Okay, this is cool, but how are you going to do this full-time?” I knew I had no artistic ability, but I knew how to write and I loved writing, so I was like, “Maybe I’ll just start writing articles.” I still wanted to understand and learn about the major label system, too. I didn’t know how to be in the environment of music and still get a check. And the thing that became more obvious as I started to grow in the industry was what was the most effective way and what felt right to me to merge my love of hip-hop, culture, and music, and the idea of having it as an occupation. So what essentially brought me here in whatever weird career title I can give myself, it is really just fragments and bits and pieces of this journey of loving certain parts, completely hating certain parts, and figuring out now, after 25 years, what was the best case scenario for me. That’s my long-winded answer of how I came to where I’m at right now. But on the hip-hop side, it’s funny because when I said 10 years old, that was actually the year that I saw “Ladies First” the music video for the first time, so there may be a little overlap of being like, “Wow, I love hip-hop. How can I work in music?” So there’s a little bit of synergy that I actually didn’t even realize. But yeah, it’s been a long road and a pretty cool one and I’m thankful to still be on it.

AA: Amazing. How did you get interested in women specifically in hip-hop?

KI: Definitely “Ladies First” was my day one, you know, it was 1989 that I saw Queen Latifah and Monie Love. We used to have this channel called Video Music Box, and it would only play between the hours of 4-6pm or something, so I would race home from school and just catch those two hours. And I remember seeing that video and I was like, “Whoa.” I was knee-deep in the New Kids On The Block craze, all that stuff, and this just shifted my entire perspective. And from Queen Latifah and Monie Love came TLC, rest in peace Left Eye. I really wanted to be Left Eye, so it was pretty sad. Many Halloweens I thought I was Left Eye. But from there it was Lauryn Hill, and I think just having this utmost respect for the women on the mic and seeing the way that they expressed their love of hip-hop and also spoke about things that as I was getting older started to speak to me too. And from Lauryn Hill it was Lil’ Kim and then it was Eve and the journey just kept continuing to the point where, you know, you’re learning about women in hip-hop but then also I am growing up and I’m reading Gloria Steinem, Angela Davis, and bell hooks. So my world kind of collided in this beautiful way. I actually wanted to write this book 10 years before it came out, but the timing just, you know, the universe said 2018 was the year to actually get the book deal, but I tried to shop this book in 2008.

AA: Hmm. Why wasn’t it the right time? How much work had you done on it in 2008? And then did you just put it on pause and wait, or what happened?

KI: So, I had been talking to an agent and he had suggested I do something similar to Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon. And he was like, “Think of your three archetypal women in hip-hop” and I was like, “How do you do that?” And he is like, “Okay, you definitely want to include a Lauryn Hill, you want to include a Queen Latifah,” and I’m like, “Yeah, but how do you not include MC Lyte or Lil’ Kim? Okay, but what about Missy Elliot?” There were so many. What about Eve? What about Trina and what about Roxanne Shanté? There were too many examples whose careers and lives didn’t exactly intersect in the way that the actual Girls Like Us book had. And he was like, “Well, think of the three.” And I was like, “Who’s the third?” I couldn’t wrap my head around it, so I just put it to the side. And I had this column in i-D magazine where I was profiling women in hip-hop. I was like, “I’m just gonna sit and I’m gonna wait for the right moment.” And I remember it was around 2017-2018 where I was going to do the memoir of another female rapper that didn’t actually work out, but I had been putting together this kind of proposal for years. And my agent one day was like, “Do you have anything else that you’re thinking about?” And I was like, “Well, I’ve been sitting on this idea of a women hip-hop book.” And he’s like, “That’s the book.” That’s how it happened.

from Lauryn Hill it was Lil’ Kim and then it was Eve and the journey just kept continuing

And it was so funny because waiting 10 years and then bringing the book out into the publishing world took what felt like five minutes. It was like 10 years and then like five minutes. Because at the time, Cardi B had just come out. And what was interesting to me is that right after I had decided to table this book in 2008 was when we saw the rise of Nicki Minaj. And I was like, “Oh, something’s happening,” right? I should also say that at the time I was trying to sell this book, it was at a period of time that the industry regarded as a very dormant period for women in hip-hop because they weren’t investing in new talent. So the marketability of the book seemed a little slower than other works. So Nicki comes and I’m like, “Okay, all right, something’s happening.” But then there’s a 10-year stretch of Nicki, just Nicki, and then Cardi comes. And what’s so ironic is that in these meetings, I’m thinking that I’m selling this book on the strength of Nicki Minaj and they say to me, “This is perfect timing because of Cardi B” and I was like, “You already jumped.” It was so interesting. But yeah, it was fast when I finally did bring this book to publishing and they were like, “Okay, good. Let’s do it.”

AA: That’s so cool. I love knowing the process, partly because I’m inspired by it and listeners listening, sometimes you have this idea that you’re like, “Ooh, could that work?” And it’s awesome to hear other people’s path with creative endeavors and bringing to light the work that’s in us. That’s just awesome. I’d love to highlight a lot of stories in the book, this fabulous tribute to so many amazing women. Obviously we don’t have time to get to all of them, and we want listeners to go buy the book so we won’t do all the spoilers. But I wonder if you could introduce us briefly to a few key women in hip-hop’s history and their achievements. I’d love it if we could start with the story of the Mercedes Ladies.

KI: Oh my goodness. Yeah.

AA: Let’s start with them and then you can just work your way down the timeline however you want.

KI: First and foremost, I think that we collectively forget just how young the hip-hop pioneers are. We saw them as grownups if you grew up even in the ‘80s, ‘90s, you saw them as older than you, right? But in reality they were between the ages of like 13 and 16. I think Kool Herc was at most 17 years old or something like that when he DJ’d the party that his sister Cindy threw. So the Mercedes Ladies, if anyone’s ever watched Grease or Grease 2, they remind me of hip-hop’s Pink Ladies. They were this cool crew of women who DJ’d, MC’d, but also they were just like out in the Bronx, they were in the scene. And when the time came that they were out there performing, a lot of the guys– and when I say guys, we’re still talking about teenagers. So we’re talking about guys who now saw women as competition. And there’s a story in the book of how the guys at one of the jams, when the Mercedes Ladies were performing at an outdoor show or something, one of the guys unplugged the turntables and in order to plug them back in you had to hop a fence. Stuff that women just don’t want to do. Telling me to hop a fence, I’d just go home. I’d be like, “All right, nevermind.” Or helping carry the heavy equipment. Imagine being a girl and these guys are competing with you now and you need help carrying your turntables. And they’re just like, “Eh,” or your records, because remember, it wasn’t like they had a USB or anything like that.

In this one particular instance, the Mercedes Ladies were performing and a group of four of them, which included Lovebug Starski, they turned down the volume in a part of the turntables that I guess like you couldn’t really tell when you’re trying to set your vinyl up and it wasn’t working. It was one of those things where it’s like now you can’t perform. And in speaking with Baby D, who was one of the DJs of the Mercedes Ladies, she was like, “It was in that moment that I realized that you see me as competition. That’s what this is.” So it was kind of this reckoning because it’s like, wait a minute. First, it’s a different story when the guys are flirting with the girls. They’re all in grade school, elementary, some in high school. It’s a different story when it’s like, “Oh, they wanna date you,” but it was quite another when you’re performing after them. In the story they just kind of turned down the dial and they needed some help, there’s like this whole blowout that happens. But it was emblematic of what was happening, where recognizing that women had enough talent to compete with men, and I think that was the big takeaway. And that’s the thing. Each of the stories in the book have some sort of a takeaway. It’s more than just “This is what happened… And then I got out of it,” right?

I think about Monie Love, who came from the UK and when she got here, at the point in time that Monie got here, a lot of the guys were signing to Def Jam. They were feeling themselves and she got there, and she’s gorgeous and they were trying to date her and she wasn’t trying to think about that. She wanted to MC, she wanted to get on stage at these shows and the guys were too busy looking at her. So she went home, she shaved her head, she taped down her breasts, and then she came back and was like, “Okay, now you’re gonna have to hear me.” I mean, they were still looking at her, obviously, but it was one of those things where it was like, “No, now you can hear me.” But to feel like you had to do that is so wild. And then I think about Rah Digga, first lady of the Flipmode Squad and the Outsidaz and getting her record deal because they believe she looked a little bit like Lauryn Hill and then having her big label meeting when she’s eight and a half months pregnant and her having to hide her pregnancy because she was afraid that maybe they wouldn’t want to sign her. And that’s so reflective of corporate America. Remember years back when they used to ask during job interviews whether you planned on having a baby in the next three to five years?

AA: Oh, totally.

KI: Yep. It’s that same thing. Or even Trina talking about how she wanted to perform and they would tell her, “You’re too expensive.” And she’s like, “Well, I’ll get somebody to do my hair, I’ll get somebody to do my makeup, outfits, all that stuff.” And they’re like, “Yeah, but what about the pyrotechnics?” Why do you need pyrotechnics when a guy can walk on in a t-shirt and sweatpants and that’s considered the show? These collections of stories that I think we haven’t really heard from their mouths, from the women’s mouths, I think made it all the more impactful. And even getting to talk to Megan Thee Stallion and watching her documentary recently on Amazon Prime, watching her mother from the window of the studio, watching her mother rap. She’s the child of an MC. So the stories, getting to hear them from the women, but then also getting to go back into other pivotal moments in hip-hop history for women and to look at it all through a different lens. That’s the strength, in my opinion, of this book. Even years later when I think about it and I revisit it, we’ve heard some of these stories but we never got to take a really deep look into what these stories meant to the rest of the world and how they shaped history thereafter.

AA: Yeah. I love this, and this is why this is a great collab between your work and Breaking Down Patriarchy. Because even as you’re talking right now, I’m thinking of the systemic patriarchy. One thing that I hear from men sometimes is, “Men have hard lives too. It’s not just easy for men.” And I always say, “That’s definitely true.” Men do have hard lives and it is hard to succeed in the music industry. But I think the next step is like, it’s hard for everybody, hard for humans, and then on top of that, have you ever gone into a job and the people who are in charge are all women and they are objectifying you and you have to make tons of adjustments to your looks, like you said, shave your head, wear something different so that you will be taken seriously as an artist. No, that doesn’t happen to you. Or is it a big deal if you’re about to become a parent? Has that ever been a deal breaker in a job? All of these things highlight that there is a system there, that on top of it being hard for everybody it is harder for women and we just haven’t talked about it, partly because women are breaking into industries that they’ve never been in before. So your stories from a couple decades ago, these are the pioneers. There are going to be pain points as women enter and people figure out that they’re going to have to do things differently than they’ve ever done them before.

Why do [women] need pyrotechnics when a guy can walk on in a t-shirt and sweatpants and that’s considered the show?

KI: Yeah, and it’s also understanding that at the heart of it all, it was all fun and games when everybody was just having a good time. But the day hip-hop made a dollar, the gender divide began, right?

AA: Ah. Yeah.

KI: And it turned into, “Well, the men have to eat first and then whatever’s left, maybe we can give you some.” I think about the story in the book when Sparky D would get invited to these shows and they wouldn’t put her on the bill. They wouldn’t pay her, but they would ask her to come on stage and rap. So the point where it was almost a full set, but she didn’t get paid, but the guy got paid. Things like that. Or the concept of considering the title of First Lady as this ranking, but all that it did was make sure there was no Second Lady, you know? If you keep pushing the “first” narrative, you don’t allow generations after.

AA: Okay. Speaking of generations after, jumping forward to the present day, what sort of challenges do you see female hip-hop artists having to confront now, or even if you wanted to talk about your own experiences as a woman in the industry?

KI: You know, I have what I consider the coolest job in hip-hop, or in the world, because I get to help our legends tell their stories and then I work as a media coach to all of the new stars of the women in hip-hop and help them shape the story that’s still unfolding. So it gives me this very interesting perspective that I didn’t have even before I wrote this book. Because you hear about these journeys but you don’t hear about them in full, I guess you could say. But this new generation, they suffer from understanding the patriarchy and playing the patriarchy at its own game, which then becomes the gift and the curse. Because women of today understand that you can’t pit them against each other. There are so many women who are just on each other’s tracks and they’re friends, they hang out. It’s the coolest thing to see. Which for generations really pissed people off when that would happen. And it’s happening now. What we’re getting now, part of it is cyclical, right? But instead of being able to pit women against each other like they used to in the past, because the narrative was that “you are the next so-and-so” as opposed to “there’s you and then there’s her,” and then there’s her and her and her and her, all these other women. It’s always like this one slot just has to keep getting replaced. No, it’s in addition to. Now that we’ve settled that debate, we’ve settled the debate that there can be more than one and the women can get along. Now we’re gonna pick apart the music. “You’re too sexual. You talk about this, you talk about that,” and it’s so interesting how everything that men have said about women in their music, women have now flipped and reversed it and owned it, and now suddenly it’s gross.

AA: I was going to ask you about that. I want to make sure we dig into that. The sexualization and objectification of women in hip-hop is a big deal. And then, yeah, tell us a little bit more about how women have responded to that.

KI: Well, it’s interesting because I think in the ‘90s we had a similar phenomenon where there was kind of this split between women who rap more about sex and women who didn’t. They called it “hypersexuality”, which is not a word that we really use anymore. I think we now call it sex positivity, right? This idea now has been the subject of debate because there are so many women, that if there are this many women rapping and even 70% of them are talking about sex in some way, shape, or form, then the overarching theme is that all women are talking about is sex. But I think that we are ignoring the concept of how rebellion works in society. Where this all began in a post-Trump America. And if we’re allowed to sit here and have a person who was voted into office say “Grab her by the P-word,” the response is you’re not taking that lying down. And if your podium is music and rapping, you’re going to use that effectively. And I don’t know if it’s the sexism, also the racism of it, how you’re choosing to express what it’s like to be a woman in society right now, especially a Black woman in society right now, this is rebel music. These women are our riot grrrls now. And maybe the messaging is not what people want to hear, but sometimes it’s what they need to hear. Because if you were okay with certain things coming out of the mouth of a man, then you should be okay with certain things coming out of the mouths of identified women. That’s just the way it goes.

Because at least we’re rapping about ourselves. “We”, as if I’m rapping, but at least they’re rapping about themselves and their own bodies and their own bedroom behaviors as opposed to it being rapped about for them. But it is so ironic that when you literally echo what men say, the message somehow gets more grotesque. How? It’s so funny. And I wish it was just identified men who say these things to me. But as we know, the patriarchy is not necessarily just comprised of men. It’s women who have been conditioned to fall in line. I can’t tell you how many times I’ll sit in a women’s empowerment panel or be interviewed by women for the subject of empowerment and the first thing they talk about is “So, rap has really gone downhill and now the women keep talking about sex, huh?” And I was like, “Whoa, okay. So this is where we’re going with this.” This idea of self-expression goes against good values or it’s poor home training. No, actually, if you have the confidence and the gumption to get behind the mic and rage against the machine, then I think you have some really great home training. That’s how I was raised.

AA: That’s a fantastic take on that. I love that. It’s awesome. On a similar topic, you bring up the B-word in the book too. Can you talk about that word? I was just thinking about this actually a couple months ago, I was talking to a friend about it and whether it’s okay for men to ever use that word, should anybody use that word, and how the context is different when men use it and when women use it?

KI: I think originally in hip-hop, when we talk about the origin story of how the B-word is used, I wouldn’t necessarily say this is the first time, but it became more prevalent during the gangster rap era on the West Coast. And there’s a story of Yo-Yo, she talked to me about how when she was on a track with Ice Cube, he wanted to call her the B-word on it, and she said, “Hold up. No, no, no, no. That’s what we’re not doing. You’re not calling me that.” But I think over the years, the idea of owning that word became synonymous with the understanding of why it was being used. Because at first, as far as I can remember, it was used for women who had an attitude, like, “You’re being a B-word. You have an attitude. Are you hormonal?” And then when you break down what do they mean by having an attitude, it’s “I don’t like how you talk to me, I don’t like you making decisions for me, I don’t like you getting in my space, I don’t like you mistreating me. This is my response to that.” It’s going to be an attitude to which then you get called the B-word. So if what you’re doing is telling someone that the way they’re treating you is not okay, and that’s being perceived as the B-word, then I’m gonna be the B-word. Right?

And I think over the course of a couple decades since the time we theoretically first heard the B-word on a rap track, it then evolved into “You don’t like how I move? You don’t like what I’m doing? I’m going to do it ten times better than you. I’m gonna make money doing it. I’m gonna hustle doing it, and I’m going to take your place while I do it.” So now, not only am I the B-word, I’m the Queen B-word. I’m the baddest B-word. It now becomes this honorable ranking. It really originated from understanding why it was being used. It’s always been in response to women asking for what they wanted. It’s so interesting when you think about the mental gymnastics of it all. A man is cheating, he comes home, you scream at him, he calls you the B-word. Well yeah, but you were the one who did something wrong. It’s that whole idea. In the book what I do is I kind of travel along this journey of the B-word, from when it was being used by men as an insult to women learning how to own it. But when men use it, to this day it is still from a place of extreme insecurity and not feeling comfortable with women voicing their wants and needs. So while I’m not a fan of men using it, if they use it on you and it inspires you to go harder, then something good came out of it.

AA: Yeah. It can be reclaimed and made powerful for yourself. Another question I have. Near the end of your book you share an interview with the rapper Rah Digga, who talks about how she didn’t always get along with female rappers. But she says, and here’s a quote, “When it was time to rise to the occasion, we banded together.” And it seems like that unity, that collective front in the face of patriarchy maybe doesn’t exist today as much as it did before. Is that true? And what’s the state of women banding together?

KI: Now, I think Rah Digga said it and I believe Monie Love said it too, because the discussions of the replacements have come during that period of time of “You’re filling the spot,” what I think women today are doing that’s different from the past is that in the past it was more like, I don’t want to say swallowing your pride, but it was kind of like not even begrudgingly, but like, “Okay, I guess we’re doing this now.” We’re doing this with the understanding that there are systems in place that are still going to try to single one of us out. But while we have an understanding, we still gotta come together. That’s what was happening in the past. Now in the present, they can’t do that anymore. I think the banding together is a little more organic than having to kind of call a truce. Not to say that either one’s more authentic than the other one, is more impactful than the other. I think when women come together, amazing things happen. But I do think that the one thing that the women of today do not have to worry about is being duped by a marketing strategy or a major label rinse cycle that’s going to just play musical chairs with them. I think having that ability to know those systems, while they may still be in place, you don’t have to play the game. I think that gives you a different level of understanding of how this game works. And now they’re choosing and they want to band together, it’s not because they have to band together.

AA: Hmm. I love that. That’s really great news actually. That’s really great to hear.

KI: It’s actually a relief.

AA: Fantastic. I guess to wrap up talking about the book, and I have a couple more questions for you afterwards, but what would you say, as readers finish your book, what do you hope are a couple takeaways that they take with them after having read it?

when women come together, amazing things happen

KI: First and foremost, I hope they have a deeper appreciation and understanding of the women who have built this multi-billion dollar industry. That’s first and foremost, because without the women that are in this book, the ship would not still be running, the train, none of it. That’s first. Second of all, I really want people to understand that for every impactful moment in hip-hop history, there has been a woman present in some way, shape, or form. I think that is important because there’s a lot of this bravado as it pertains to the history of hip-hop now that we’re over 50 years into it. This idea of the forefathers, but there are so many mothers in this, and there continue to be. And another thing is that I really hope that people, just from my perspective as the person who wrote the book, I hope they see and they hear and they feel my heart in it. Because I’m not a Black woman, I’m not a rapper, but I have been a woman in hip-hop for 25 years. I so deeply love this culture, and I really want everyone to know that this was a labor of love. This was written at a very terrible time in my life, and I still finished it because I loved it and because I felt like I had no choice in the throes of my own grief and in losing my mother during the making of this book.

So, for me, this idea of still going and pushing forward. So many different times, I did push forward because of the strength of the stories that I was hearing and how they inspired me, but also the women in the book who I had spoken to, who honestly carried me. They didn’t have to do that. In talking to so many women, even getting to talk to Meg about my mother and hearing about her mother, we had both lost our mothers within a month of each other when we did the interview. We didn’t have to have that connection, we didn’t have to talk about those things. I think the other part of it is that there was something so therapeutic for me, and I was really reluctant to put any part of myself into the book. My editor had urged me to do it, and I was like, okay, but that’s why you kind of hear me check in and out, because I don’t want to make it about me. It’s not my story. But I think in doing so, oddly enough, a lot of people tell me that those are their favorite parts of the book. But for me, I really did want people to understand the impact that women in hip-hop can have on someone’s life. A profound impact. They had an impact on me as a kid, but then they had an impact on me as a 40-year-old woman who lost her mom. And being able to put words to that during one of the most trying times in my entire life, I hope people feel it, and I hope people understand that too and find strength in the women, but maybe find strength in me too.

AA: Yeah. That’s beautiful and I’m so glad you did that. I do think that’s so powerful when that authenticity of the author comes through and it’s just a human being. It’s storytelling, it’s in this beautiful human tradition of storytelling. And being a historian, I was going to say as you started to talk about women being there for all of the moments all the way through, it reminded me of one of the very first episodes we did on the podcast years ago when we were highlighting Gerda Lerner, who is this great women’s historian, and her talking about what we’ve always thought of as history has been just the stories of men, and that’s been labeled history when it’s only been about men, written by men, interpreted by men, and they’ve claimed universality for that history like that’s the history of humanity. And the women were, I don’t know, it doesn’t even matter what they were doing. And she talks about how women were there all along, doing everything all along. So it’s not like women’s history is this marginal thing. It was integrated. Women have been there from the beginning, we just haven’t been telling the story correctly. We’ve been only telling half the story forever. So it feels like this novel, marginal, special interest story to talk about women. I so appreciate you diving into this untold story and saying, yeah, this has not been a complete history yet. So kudos to you for doing it.

KI: Thank you. I really appreciate that.

AA: One of the last things I wanted to ask you about is the other projects that you’ve done. I know you’ve worked on a memoir about Eve and you have an upcoming memoir with Lil’ Kim. Can you talk about those projects and what those highlight?

KI: Yeah, definitely. Eve’s memoir was just released in the fall, it’s called, Who’s That Girl? And the cool part about Eve is that she has kept her story so tightlipped, and in this book she was just so transparent in talking to the reader about her journey as a multihyphenate. Because the one thing that I think Eve brings to the table that no other artist has is just a lot of the firsts that we don’t think about. She was I think the first artist who had her own sitcom, named Eve, where she was the executive producer. And within two years of being in the industry, she had already pivoted into television and in Hollywood film. She was the first woman in hip-hop to have her own fashion line. And her telling these stories, but then also opening up about, I used this phrase before, the mental gymnastics of being a woman in this industry and everything she had to endure, but then also understanding when things didn’t serve her. It’s a book that I’m so proud of. I’m so proud of her and the way she just taps in, and her honesty is just different. It’s a different book and I just love that. I love it so much.

And with The Queen Bee, I love that book so much too, but it’s more like a movie. Kim’s life is like a movie. I mean, Eve’s life is like a movie too, don’t get it twisted, but there were times that I would be working on this book with Kim and I’d be like, “That happened?” And she would just laugh. Because you’re talking about someone who started super young. Kim was a kid when she came out on the scene. And just the enduring impact of this artist who, you know, she was at the Barclays Center, she came out for a Latto show. I remember Latto was like, “I’m in Brooklyn, I have to bring out the queen” and Kim came out and it was like pandemonium. And to have that impact and to watch so many generations of fans gravitate toward her. And when we put this book together we knew there was something special, but it’s also giving you this panoramic view of not only Lil’ Kim, but Kimberly Denise Jones. And she tells her story about becoming a fashion icon too. I’m really, really excited for the world to finally get to read it. I’m fortunate because my two faves are Lil’ Kim and Eve. How did I get so lucky? I always say my top three are Kim, Eve, and Lauryn Hill, so somebody get Lauryn on the phone for number three.

AA: Awesome.

KI: Yeah, it’s exciting.

AA: That’s so great. I love it. It does sound like a dream job, honestly, but good for you for working so hard and getting yourself to where you’re able to do this. And like I said, to be telling these important, important stories and excavating this history that hadn’t been told yet. So, so great. Well, aside from picking up a copy of all of these books, including God Save the Queens, and I do encourage listeners to go and get these books and read them, where can we follow you? How can we learn more about your work? Do you have social media handles or anything that you want to share?

KI: The docuseries Ladies First, I was a producer on that. That’s on Netflix still streaming, and you will see my face on there, but, you know, don’t let that deter you. But on socials, you can find me @kath3000. I have two other gifting items, my Hip-hop Queen Oracle deck where I made inspirational messages and images that are reflective of women in hip-hop and also my mental health and hip-hop record journal called Get Your Mind Write. If you do follow me on those socials, you’ll see me bragging about everything because apparently now we have to be more forward-facing on these things and, you know, let’s end the imposter syndrome, so I guess I’ll plug it.

AA: Good for you. No, that’s so great. And the more people do it, the more we can just get over it and promote the work that we’re working so hard on. Good for you, and Kathy, what a great conversation and I am so grateful for your work. Thanks for joining us today.

KI: Thank you so much for having me!

everything that men have said about women in their music,

women have now flipped and reversed it and owned it.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!