“this super secret dialogue in a windowless basement…about abortion”

Amy is joined by filmmaker Sarah Perkins to discuss her documentary, The Basement Talks, hearing a powerful and pertinent story about women coming together in the wake of violence, recognizing the humanity in our political rivals, and what we talk about when we talk about abortion.

Our Guest

Sarah Perkins

Sarah Perkins is a filmmaker and PhD student at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, though she currently resides in rural southeast Idaho with her family. Together with her husband, she is the co-director of The Basement Talks. Previously, she worked as production manager on American Tragedy, which won Best Documentary at the Boston Film Festival and as the editor for the Herbe Nassour story. In her graduate work, she studies 20th-century literature and theology around the question of theodicy.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: As longtime listeners might know, I have a complicated history when it comes to abortion rights and reproductive justice. I was born and raised in an extremely conservative religion and family where a pro-life position was an absolute given. It was unthinkable to even consider anything else. And because my life experiences never confronted me with a reason to reconsider, I never did, until I took a class on women’s health and human rights, and I saw data and I learned the stories of women’s lives, and I understood the patriarchal power dynamics. This created a massive change in my perspective, and now I unequivocally support women’s right to choose. But I am actually really grateful that I have gotten to experience both sides of this debate, and I want to challenge listeners to remember next time you interact with someone arguing a pro-life side, that was Amy 10 years ago. And I wasn’t stupid or evil 10 years ago, I just had a different way of seeing the issue. Today’s episode is about the abortion debate, and specifically some events in the 1990s that may surprise and horrify and ultimately inspire you. I had not known about this story until recently, and I think it’s critically important to note this story right now as America continues to reckon with one of the most divisive and contentious issues of our time. I learned about this event through a documentary series called The Basement Talks by documentarian Sarah Perkins, and I am thrilled to welcome Sarah to the podcast today. Welcome, Sarah.

Sarah Perkins: Thank you so much for having me.

AA: Sarah Perkins is a filmmaker and PhD student at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, though she currently resides in rural southeast Idaho with her family. Together with her husband, she is the co-director of The Basement Talks. Previously, she worked as production manager on American Tragedy, which won Best Documentary at the Boston Film Festival and as the editor for the Herbe Nassour story. In her graduate work, she studies 20th-century literature and theology around the question of theodicy. This is so fascinating, Sarah. Can you tell us a little bit more about yourself, where you’re from, and how you came to be a documentarian and do the work that you do now?

SP: Yeah, absolutely. I grew up in suburban Texas and then I went to school, where I met my husband, and we both graduated in English Literature. And I continued to pursue secondary education and literature. I’m still finishing up my doctorate, which I will hopefully graduate next year. And my husband started doing freelance writing projects, which anybody familiar with freelance writing will know that it’s just the worst, starting out. There are a lot of essays about tires and plastic surgery and stuff. So he had the opportunity to potentially get involved in a documentary, so he bought a camera. And really since that time, we’ve collaborated on pretty much every film project that has come our way. It’s something that he just sort of fell into, totally happenstance, but it’s been an incredible opportunity. One of the great delights of my life has been sitting with people’s stories and really trying to understand them and present them in a way that grants dignity and curiosity for viewers. It was never my plan for my life, but I’ve loved it.

AA: Amazing. And then what even tipped you off that there was this thing that happened in the ‘90s? What drew you to this story? How’d you even learn about it and then decide to document it?

SP: Well, we had just finished this documentary called American Tragedy. And then we had this heart project of making a film that grappled with polarization. And we wanted a story that would reach people who weren’t already concerned about polarization, right? And that’s a big ask, because either you’re really concerned about it or you don’t want to talk about it. And the reason we were really drawn to that is because we saw polarization impacting all of these spaces. We’re religious people and we saw in our church congregations good men and women who were self-censoring and who were being censored, and who were not able to have these productive conversations that require a fully present human in all of their perspectives and complexity because they felt like they couldn’t bring that to church.

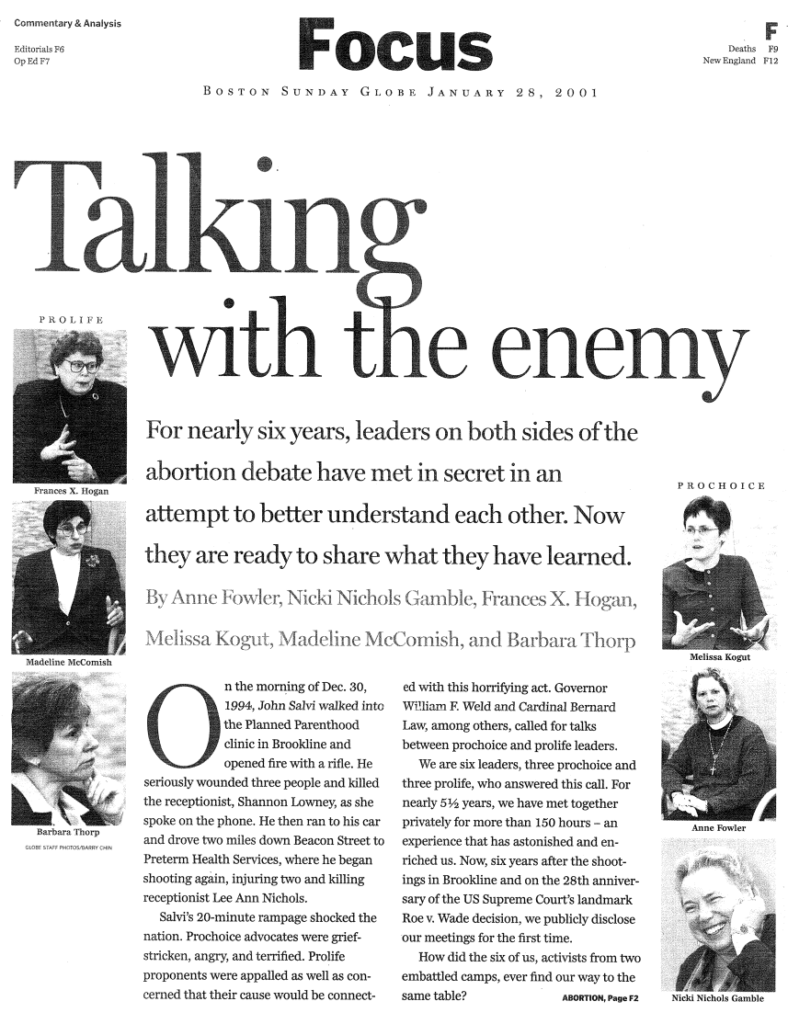

And then conversely, I was in my doctoral program by this time, and there was this wildly intelligent woman in my cohort who was thoughtful and widely read and informed who held really deep pro-life convictions, and she was terrified that people in our cohort would find out, or that our professors would find out because she thought that she would be punished in some way for having these sincere convictions. And I think both of those struck us as so tragic and wrong that these were spaces where ideas are meant to come to the surface and be tested and challenged and explored. Increasingly, they were being sort of pruned away in favor of this sort of larger narrative that didn’t fit everybody. So we were searching for a story that we thought could reach a wide audience. For a while, we were looking at climate change and how polarization impacts our ability to meaningfully address climate change. But then when we were living in Massachusetts for my doctoral program we found this article in The Boston Globe from 2001, which the women in the Basement Talks had co-authored, and we knew that we had our story. It was this incredible, incredible story we had never heard about, and that felt so unique and so unexpected that we thought it had the legs to reach a wide audience.

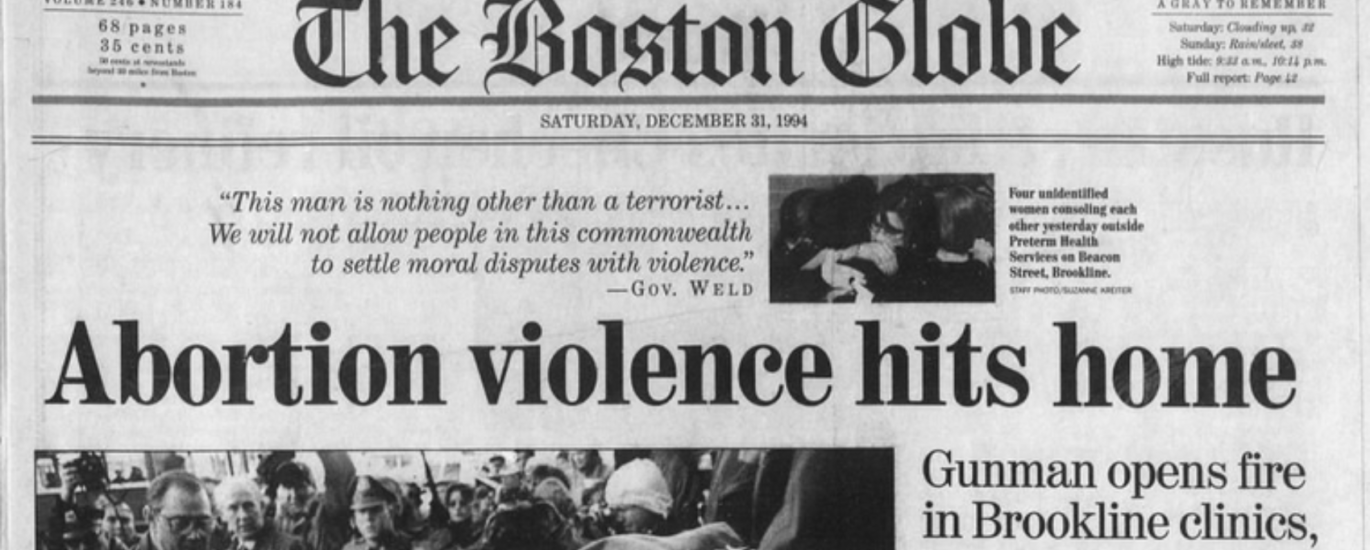

AA: I agree. Watching the documentary, I couldn’t believe that I had never heard of that, that I hadn’t known about it. And we’ll talk about that later, why we hadn’t heard about it, but I wonder, Sarah, if you could just tell us the story and the details of it. Don’t just gloss over it, I want to know the whole story. We, of course, want listeners to watch the documentary also, so you can save the spoilers, but tell us what happened. Maybe we can start on December 30th, 1994.

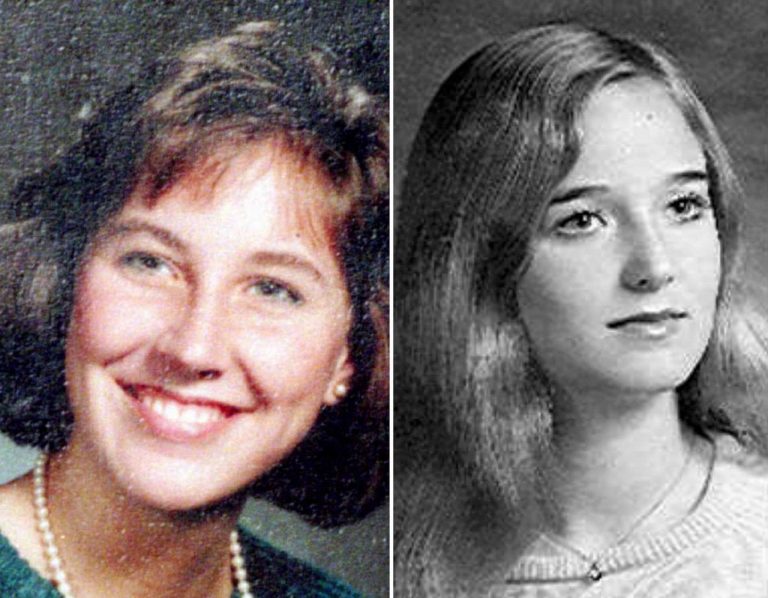

SP: Yeah, so December 30th, 1994 was a day marked by tragedy for the Boston Metro area. There is a man who is deeply schizophrenic, deeply unwell, named John Salvi, and he bought a gun and he drove to a Planned Parenthood clinic in Brookline, Massachusetts. He entered the clinic and without saying anything, he opened fire and injured five or six people there and killed, immediately, the receptionist, her name was Shannon Lowney. She was 26 years old, I think. And then he got back in his car and he drove about a mile and a half down the road, down Beacon Street, to a clinic called Preterm Women’s Health Clinic, where they also provide abortions. And he went into the clinic and he asked if it was Preterm, somebody said that it was, and then he opened fire again, injuring several other people and again killing at point blank range the receptionist there, her name was Leanne Nichols and she was 38 years old. And then he got in his car again and was able to escape Massachusetts. He drove out of Massachusetts and he was apprehended the next day in Virginia, where he was trying to shoot up a clinic in Virginia, but it had been closed, there was nobody there, he just shot out the windows.

And the wreckage, the incredible violence of the act was such a scarring event for the entire community. I think people were deeply, deeply traumatized by the event of the shooting itself, but then also the emotional fallout of that as people were trying to grapple with what happened and how to make sense of it. Boston is a really complex place because you have all of these, I would say sort of liberal bastion universities, right? There’s Harvard right there and Boston University and all of these different colleges. But then there’s also a highly, highly Catholic population. So the divisiveness that this shooting revealed that was already present in the community, but exacerbated, was really, really painful. So then this led to a whole trial, and we cover the trial in the documentary, but then underneath all of that, underneath this really divisive, horrible, painful public discourse, six women who were all leaders in the abortion debate on different sides, three pro-life and three pro-choice leaders, agreed to meet in this super secret dialogue in a windowless basement and talk about abortion, talk about the very thing that they disagreed about. They initially agreed to meet four times. In the end, they met for six years. There are 150 hours of recorded dialogues between these women on cassette tapes, and that is a story of the Basement Talks.

AA: Amazing. I have so many questions. One of the questions, if we’re just talking about the story, can you tell us a little bit about– there’s this literally underground conversation going on, but what was the public discourse like? In the media, how were people talking about the shooting and how was that revealing the greater issue of abortion rights?

SP: Yeah, unsurprisingly, there was this scramble to control optics around the shooting, and everybody had different stakes in it, right? The prosecutor really pushed for this to be purely a political shooting. This was a pro-life activist, an extremist in the pro-life movement, and he went and shot up these clinics because he hates abortion, and that just makes for a really clean prosecutorial angle. The defense attorneys on the case were really trying to emphasize how deeply unwell this person was and that the pro-life arguments were actually just a small part of the many, many, many conspiracy theories that this individual carried. And then the pro-choice movement was trying to fundraise around the trial, understandably very, very upset about the shootings. And they kept going to the trial and speaking at the stairs of the trial about how this event manifests the need for more funding and more protection for these clinics, and for women attending them and working in them. And then the pro-life movement was doing everything that they could to distance themselves from the shooter to argue, you know, “We’re a pro-life movement. We value human life at every stage. Violence is never our messaging, this is not who we are.”

I think what you see in the news media is actually really fascinating as we were going through archival footage from the ‘90s around this event. We watched this documentary that Frontline put on called ‘Murder on Abortion Row’ and they interviewed several different people from the pro-choice movement and then they interviewed several different people from the pro-life movement, including most of the women who were involved in the basement talks. But when the program actually came out, the only pro-life speakers that you see in the documentary are these very frightening white men who are big advocates of just terrible, abhorrent philosophies like justifiable homicide, where it’s okay to shoot an abortion clinic provider because they’re killing other people, just absolutely abhorrent philosophies. And they’re the people who were given the microphone, who were given media time. So you see how soundbites and camera time became really prioritized in the above-ground conversations in a way that was never going to provide any sort of meaningful healing discourse for the community.

AA: This is so interesting to me too, your process of discovering. So you get all of these archival materials. What did that feel like to you as you were listening to the tapes and as you were watching the footage? What was that experience like for you and your husband, your co-director?

SP: Yeah, it was totally fascinating to see how divisive this rhetoric was. And also the ‘90s was the time when doctors were being killed pretty regularly, abortion providers were being killed with some regularity, and that’s not something that we’re seeing as much anymore. So that was surprising, because I think of abortion as this really, really divisive issue, but I think clinics provide better protection than they used to and I think we’ve moved to a different phase of what this debate looks like. And that’s maybe hopeful.

AA: Yeah, for sure. It was for me too. Returning to the story, what happened to the shooter? They caught him in Virginia and then there was a trial, and that’s like a media circus around the trial. What happened to this individual? And having watched the documentary, he was schizophrenic, right? It seems like it was less, honestly, less about abortion for him personally, right? What was the trial like and what was the outcome?

soundbites and camera time became really prioritized…in a way that was never going to provide any sort of meaningful healing discourse for the community.

SP: Yeah. When we were making the film we went to Norfolk Superior Court in Dedham, Massachusetts, and they brought out, I think, 17 boxes of evidence and they let us go through all of it and scan documents. So we saw his writings and they were just not well, you know? He had all these conspiracy theories about the KKK and the conspiracy to eliminate all Catholic babies so that Catholics have less influence in the world. Just a strange, strange person who got into these really unhealthy thought patterns. And ultimately in the trial he is found guilty. He’s found competent to stand trial, which was really controversial, and then he’s found guilty and he goes to prison rather than to a state healthcare facility. And there it seems pretty likely that he was killed in prison, though officially his death is ruled a suicide. So it’s this really unfinished, unresolved thing. The trial provided the guilty verdict, but because it was in appeals when he died, the verdict was actually dropped. So there’s this complete lack of resolution around the shooting that the trial supposedly promised. This promise of justice that completely falls through.

AA: Yeah. And like you said earlier, there was this tragic, tragic event, and one thing that the documentary does so well is making you sit with this 26-year-old, so young, that’s only a little bit older than my own kids are right now, and a 30-year-old, and the grief of those families, of these young women being murdered. And with that said, then it turns out that the actual crime was not so much about abortion, but then it brought up this huge, huge debate within Boston and then global.

SP: The wider nation as well.

AA: Yeah, the whole nation. I’m wondering how the Basement Talks got started. Whose idea was it? How did they find, like, “Let’s have these three people on this side, these three people on this side”? Who reached out to whom, and what were their talking points? What were they trying to accomplish in reaching out to each other?

SP: Yeah, so the Basement Talks is this extraordinary project that took so much chutzpah on the part of the organizer. It was a woman named Laura Chasin, who was unfortunately the only person who was deceased at the time that we were working on the film. But she was really the heart and soul behind this project. She saw this deep wound in the society of Boston, and she felt like there was a different way to go about finding resolution for it in a way that didn’t require people to change their positions or even find common ground, but just sit with each other and sit through this tragedy together and try in a much realer way than they ever had before to actually understand each other.

So she founded an organization called The Public Conversations Project. It’s now been renamed to Essential Partners, it still exists in Boston, it’s still doing great work. They’re headquartered, I believe, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She and Susan Podziba, who was the other moderator for the conversations, interviewed about 20 to 30 people who were all really involved in the abortion debate. And they said that these six women naturally rose up to the top of the list. They were all leaders of the movement, the people writing the op-eds, people who had the most impact on what sort of rhetoric their organizations were putting out into the public sphere. So they interviewed these women and they invited them to participate in this dialogue with their political enemies, right? With people who they had debated in talk shows, people who they were honestly pretty afraid of, actually. And most of the women talk about each other prior to the dialogue saying, “I thought that they were a little bit evil… I thought that they were probably not very smart… I thought that they probably had really controlling husbands,” all of these stereotypes and misapprehensions of who these women were.

The women who participated were Nicki Nichols Gamble, she was the head of the Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts, a really, really big personality, wonderful woman. And then Barbara Thorp, she was the first layperson ever to be put in charge of the Pro-life Office of Massachusetts. And then Anne Fowler, she was a pro-choice Episcopal priest who was on the board of Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice. And then Madeline McComish, she was a chemist and she was really, really involved in cancer research in Massachusetts and she really feels like her scientific mind brought her to pro-life advocacy. And then there was Melissa Kogut. She was the brand new, like 20-something year-old executive director for NARAL Pro-Choice Massachusetts. And then there was Fran Hogan who was a lawyer and had been involved in every single pro-life organization that ever existed. Anyway, all wildly intelligent women. They all came and they sat down in this room together and they talked about these first few conversations being really, really tense and rough because they realized that the words that they used to talk about the issue of abortion already inhabited their position. Pro-life women really wanted to use the word “unborn child” when they’re talking about the thing which is removed from a woman during an abortion. And that obviously implies something about what’s being removed. Whereas the pro-choice women wanted to use the word “fetus” because that feels a little more sanitized, a little more like a biological, clean process. Neither of them liked either of those words. They both rejected them outright as like, what are we willing to use to talk about what’s happening?

So the first four conversations or so were all about trying to figure out a language that they could use to talk about the issue of abortion in a way that didn’t actually shut down conversations right away. There was like a list of, I think, more than 300 words that they couldn’t use, and then a list of 200 words that they could use that felt really unnatural but palatable to the other side in terms of what’s taken out of a woman during abortion. They used the word “human fetus” because it acknowledged the humanity of the fetus while also avoiding the sort of charged implications of “unborn child.”

AA: Oh, I think it’s so important. We did two episodes on Roe v. Wade in our first season of the podcast. I did this episode with my sister, who’s a labor and delivery nurse, and that was the very first thing we talked about was the language. I think on the Planned Parenthood website it’s not even “fetus”, they say something like “material” or the “pregnancy matter” or something like that. And yes, that conveys a lot versus calling it a “baby”. I’m so happy that you pointed this out. For any charged emotional conversation, agreeing on definitions of words, implications of words, I think you have to do that at the beginning or you’re just going to talk past each other and never get anywhere. Thanks for highlighting that importance of vocabulary.

Madeline McComish (top row, center)

Nicki Nichols Gamble (top row, right)

Barbara Thorp (bottom row, left)

Melissa Kogut (bottom row, center)

Frances X. Hogan (bottom row, right)

SP: Yeah, absolutely. I think pretty much anytime you move from a dialogue to a debate, what almost always happens is that you’re talking about something and the other person is talking about something totally different and neither of you are talking to each other.

AA: Yeah, and that leads me to my next question about these conversations. So they agreed on terminology, they were really committed to try to make it work. I can imagine the tension in the room, especially at the beginning. What happened over the course of the conversations?

SP: Yeah. So, a few things. I want to mention this really remarkable essay that I found while we were working on this film. It’s from the ‘90s, so around the same time that this conversation is happening, and it’s called ‘Beyond Literary Darwinism’ and it’s by Olivia Frey, and I just loved this essay. In this essay she talks about how so much of academic discourse and public discourse is really competitive. It’s really Darwinian, sort of survival of the fittest, and it’s really, she says, masculine. This sort of muscular, pummeling everybody else down in order to get your point across. And she advocates for something that she knows will be dismissed as sophistry, but she calls it a “womanist discourse” where emotions matter, relationships matter, and sitting and talking and conversing in an emotional, relational way matters and actually can be really useful to arriving at some sort of truth and understanding in a way that a more Darwinian, masculine mode of engagement misses.

And I think that’s exactly what was happening in these Basement Talks. You have these six women who are sitting down together talking about this most difficult issue that they all care very, very deeply about and trying to do it in an emotional, relational, and they even use the word “loving” way. And I think because of that, they actually get to a point where they’re able to understand each other in a way that I think they actually hadn’t before. They get to a point where they’re able to be friends and that, in turn, I think, changes everything else. Nobody changes their mind. They all actually report becoming “firmer in their convictions and clearer in heart and mind about their advocacy,” those are the words that they use in the article. They are able more than they ever had been before to actually hear what the other woman is saying and respond directly to it, and that hadn’t been a possibility before because they only heard their own coded language about what she was saying rather than what she was saying.

So, as I was going through articles in The Boston Globe when we were making this film, there was this article and the headline was titled ‘Has Anybody’s Mind Changed on Abortion? It Seems Not, But the Rhetoric Has.’ The whole article was about how we’re not sure why, but the rhetoric seems to have been changed, people are talking to each other differently than they had before. It mentions how Madeline McComish was using the word “pro-choice”, whereas before she would only use “pro-abortion” and it talks about how they were responding more directly to each other and how they were acknowledging the strong points that the other person was making and they had never done that before.

I think the big question of this film is what do you gain by sitting and talking with somebody who will never agree with you, who you will never persuade to come over to your side? I think a lot of people feel like that’s a really weak position, to just be a peacemaker or to be soothing other people or talking with people who are the enemy or platforming bad people or people with wrong perspectives. And I think it’s a good question. The suggestion of this movie and what these women I think really came to believe is that you learn something about yourself, you learn more about what you actually believe because you have to articulate it to people who disagree with you. And I think more importantly, you are better able to produce an environment where you can articulate those beliefs and other people can articulate beliefs opposite of yours in a way that doesn’t perpetuate violence. And I think that’s something we struggle with and that we really need to practice right now.

a “womanist discourse” where emotions matter, relationships matter, and sitting and talking and conversing in an emotional, relational way matters

AA: Yeah, I think humans always struggle with it. And the culture is changing in the opposite direction, I think we can all agree with that, right? The divisiveness and like actual– I feel like it’s hatred. It’s becoming hatred for each other, and that is one of the scariest things that I’m seeing in America. Because in order for a democracy to survive, I think people need to have respect and compassion and empathy for each other. Again, even if they disagree with each other. This is such an important model for that, just incredibly important.

SP: Right. And I think one of the big surprises for all of the women in the documentary is that the enemy that they had supposed was actually way more similar to them than they had ever imagined. That they could have polar opposite viewpoints and be people of really profound goodwill. You actually hear a section from the Basement Talks themselves, a little clip from the cassette tape recordings of them, and it’s Madeline McComish talking and she’s saying, like, “I really think that abortion is evil, that’s a core conviction that I have. And I think that you sincerely believe that you’re helping women and that you’re coming from a place of trying to do good in the world and that you’re people of goodwill. And separating, making that distinction is just really difficult for me, and I think I can do it now. It’s been work but I think I can do it now, but I don’t know that people in my organization are able to do that yet.” And I think that’s such an important point of just how much work it actually takes to recognize that the people sitting across from you, the people that you perceive as your enemy, are usually also trying to do good in the world. And making that connection takes time and takes effort.

AA: So much effort. Because again, it’s really not human nature a lot of the time. And then once you get narratives that inflame the worst side of our human nature, when it inflames like that and then we use words that further inflame it, it can be almost impossible. This is so inspiring.

I want to now talk about how they’re meeting in a basement, they’re doing this incredibly powerful work that could benefit their entire organizations and the nation at large, right? Why were they in a basement instead of having this be a public debate and say, “Listen, watch everybody. We’re going to do this and we’re going to heal together.” Why were they in a basement? And then did they ever take it public, and what happened?

SP: Yeah, great questions. There are a few reasons why they did it in a basement. One was that there were threats of violence for anyone who participated in the dialogue. Word had gotten out that the dialogue might be happening. There was an organization called Operation Rescue, which was a lot more militant in its pro-life advocacy. They were the people who were chaining themselves to the clinic and often using even more violent techniques to promote pro-life perspectives. The Operation Rescue of Massachusetts had left some really, really frightening voicemails about anybody who participated in this cross-party dialogue effort. So that was part of it, it was just for the physical safety of the participants. Also I think most of them were afraid of what would happen if word did get out about their participation. Madeline McComish told us about how somebody in her organization had said something to the effect of “Mass Citizens for Life had better not be participating in this dialogue.” And she responded, “Mass Citizens for Life is not.” She was participating as an individual, not as a representative of the organization. But you can see how there was a lot of tension and it took a lot of bravery for these women to come into the room, not just because it was going to be tense and awkward and painful, but also the real disapproval from the public that could and sometimes did occur.

AA: And people had just been killed, also.

SP: Yeah, there was already a sense of unsafety around the issue itself. And it actually reminds me a lot of social media, where anytime you’re posting in a comments section, you’re responding to the person but you’re also responding to everybody else who’s watching the comments section. So there’s always an audience and that changes the mode of interacting, the mode of conversation. And I think that’s actually why a lot of debate is the way that it is, because you’re sort of responding to the person across from you, but you’re also responding to the audience watching. So I think that was a really, really important factor in these dialogues being successful, is the fact that they were able to sit and respond to the people around them rather than to everybody else as well. In that sense, the privacy of the conversations was really, really key to the conversations being successful, or even happening at all. I don’t think they would’ve done them if people had been watching.

They did eventually go public with the conversation. They debated a couple ways that they might be able to do that, and they eventually agreed to write an article together. And that seems maybe a little blasé or like whoop-dee-doo you wrote an article. But actually I think it was a monumental undertaking because these were six women who had polar opposite worldviews who had to create something where everyone agreed to every single word that was in the article. And they described the process taking more than two years to create this article and they sent it off to The Globe. We interviewed the Globe editor, who was Matt Storin at the time, and he was totally astounded that it had happened. He was really excited to have it in his newspaper, but the article didn’t meet The Globe‘s style guide at the time. The Globe used the term “abortion foes” or “anti-abortion advocates” rather than “pro-life advocates”. And again, going to language, that was a really important part of this conversation, that the women would use the terms that they preferred. Pro-life and pro-choice were the preferred terms. So they responded and said, “We will only publish this article with The Globe if you use our preferred language.” And they went back and forth and then eventually they threatened to go to The Boston Herald, and that’s when The Globe relented and allowed them to publish it using the terms “pro-life”, but with a little editor’s note that those are not the terms that The Globe supports.

And the immediate impact was quite large. They got onto all of these cable shows and they were invited to this big women’s meeting in Rhinebeck, New York, where there were thousands and thousands of women in attendance. Sally Field also spoke there. Then it sort of tapered out, and there are a few reasons for that. I think one of the biggest ones is, again, when we were looking through the archival footage, you would see them talking about the abortion talks – that’s what they called it at the time – and then in the next new sequence, you would see them talking about the scandal in the Catholic Church with pedophilia and the ‘Spotlight’. So the scandal in the Catholic Church totally buried this story. It was all coming out at the same time and it attracted public attention, it was this new, big, controversial thing and so that’s what everybody started talking about again, and this story sort of died in a whimper.

AA: Yeah, that was one of the really surprising things to me, too. But I guess it shouldn’t be surprising because, as I said at the beginning of the episode, I had never heard about the Basement Talks. But I do remember, of course, the scandal in the Catholic Church about priest abuse, and that’s important, too, to highlight. But I was really, really sad that this story got lost in that big media attention.

SP: Right. And I think for the women, too, it was this whole new thing because all of the pro-life women who participated in this conversation were very devout, committed, wonderful Catholics. And I think it was this whole new thing that they found that they couldn’t talk about because the pro-choice women really wanted to talk about it and try to understand them, and I think the pro-life women were still totally in the thick of things and felt like they couldn’t. And so it was another challenge, another difficult conversation that they couldn’t have yet.

AA: Yeah. Well, I’m so grateful that you found this story and have brought it to light. And honestly bringing it to light when you did, maybe there are benefits to that too, that this is a story for our time, truly, and this is a new, fresh story for us that we didn’t hear about at the time. I wanted to ask you one more question about this event that happened and talk a little bit about how to keep abortion clinics safe. As you said, shootings are rarer now than they used to be, but having studied the history of these tragedies, is there anything that you’d recommend to keep healthcare workers safe while the debate continues?

SP: Yeah, absolutely. In terms of the physical safety of clinics, I think they’re actually doing a lot of work in that regard. There are all kinds of safety measures in place that weren’t in place in the ‘90s. Certainly you can volunteer as an escort and there are those sorts of opportunities that you can do. But I think also there’s the really underplayed reality that actually modulating the rhetoric does a lot to keep these clinics safe. I’ll explain what I mean by that. In working on this documentary and in interviewing people about political violence and what political violence typically looks like, I learned that in the vast majority of cases, the people who actually enact political violence tend to be “lone wolves”, which are people who are usually mentally unstable, mentally unwell. Like John Salvi had schizophrenia, I think also the person who was involved in the Trump assassination attempt seemed like a very clear lone wolf figure. Someone who is mentally unwell and who gets sort of swept up in these tidal waves of really, really toxic rhetoric. So I think just keeping a pulse on how violent our rhetoric is, on how violent the tone with which we discuss the people on the other side, is really, really important for preventing violence. Because you might not actually be advocating for violence or doing anything violent yourself, but if the tenor of the rhetoric amps up to really dangerous levels, then political violence is much more likely to happen. So I think just being cautious and being aware of the tenor of the rhetoric in the public sphere at all times is really, really important. Both for the safety of our democracy, the safety of our emotional security with one another as Americans, but also actually for our physical security as well.

AA: Thank you so much for that. Speaking of that, I’m wondering if we can now talk about the status of reproductive rights in America today. What’s changed since the 1990s and what has stayed the same?

SP: I feel like there’s actually a lot of both. The biggest change, obviously, is the overturning of the Roe v Wade decision in the Dobbs case. For the documentary we interviewed Catherine Colbert, who argued the Casey case, which was a really similar case where Roe v Wade could have easily been overturned. It was just before the 1994 shootings, and she says that in terms of people’s perspectives on abortion, those have remained really, really stable, actually for more than 50 years. About the same number of people self-identify as pro-life, about the same number of people self-identify as pro-choice. If you’re looking for where most Americans are concentrated, most people can be basically summarized by President Clinton’s articulation of “safe, legal, and rare,” which is not really what either party advocates for in the mainstream, which is interesting. So people’s perspectives are relatively unchanged.

The landscape is really quite changed, where I think the bulk of the debate and the advocacy work for abortion and reproductive rights has moved from the federal level to the state level. So it’s a lot more patchwork state to state, different sorts of debates. I will say, we actually screened the series with the women for the first time a week after the Dobbs decision came down. As filmmakers, that was very frightening because the polls had switched. And we had no idea how these women were going to react to each other because it would be the first time that they would be in the room together, watching our film. And we wanted them to like the film but also we recognized that this was a very, very tense moment. I remember we screened it at this hotel apartment thing in downtown Boston and we were sitting in the room with some of the women who were already there, and Madeline McComish came in, and she’s probably not quite five feet tall, she’s this very little, sweet Catholic lady. And she came into the room and she walked straight up to Nicki, who’s six foot five at least, and she gave her a big hug and she said, “We recognize that this is not a moment to be exultant. You must be hurting.”

AA: Oh my gosh.

SP: And it was this huge impact on my life, actually, to recognize this woman who had been hoping and praying and actively working for this end exactly, recognizing how that might profoundly impact somebody who she deeply cared about. And being willing to set aside any sort of advocacy work in that moment to attend to this relationship that she really, really valued, and for both to be true at the same time. I think that’s complicated and hard, and I think incredibly hopeful that that’s possible. For myself, I was really deeply disappointed last week over the results of the election. I think literally every single person I voted for failed. Everyone I voted for lost. And we had a couple over the next day and I was kicking myself for it because I was like, I don’t actually want to talk to anybody, I don’t want anybody here. The people I had voted for failed in a big way, like 80/20 in almost every single race. And I felt really alone and really isolated. And I had a really similar experience, where somebody in my community who I care about, who cares about me, who voted differently than I did, hugged me and said, “You’re probably having a hard time. I’m sorry.” And for me, that was really helpful.

“safe, legal, and rare,” which is not really what either party advocates for…

AA: Well, I’m crying partly because it’s been so, so hard for me. We’re recording this at the end of November or mid-November, I guess, it feels like forever since the election already and it’s been like a week. One of the most distressing things to me, other than the outcome of the election, which was obviously devastating to me, is the tone that people are using, especially on social media. Just blame and anger and “I’m never trusting that group again” and “I can’t trust you” and “I hate men.” The tone that people are using with each other has been so discouraging to me and has really been hard for me to think how are we ever going to heal? How are we ever going to move forward? Even people who voted similarly, the blaming of each other, let alone the blatant animosity that is being expressed even in families. Anyway, this is giving me a lot of hope, and I’m grateful and so, so happy to be airing this episode as an example of what I really do believe is the only way forward for us.

And I have to respond to this, it was kind of surprising to me watching the documentary that the women didn’t change their minds. I really expected that some of them would. I kind of expected them to have the experience that I did once I looked at the data. Once I looked at the examples I was like, “Oh, okay. I trust women to make the choice. Somebody has to make the choice. It’s either male politicians or it’s the individual woman with her doctor.” That’s how I came to see it. But again, like I said at the top of the episode, a lot of people I love still feel a different way about it, and I myself used to. So I do have empathy for people who see it differently and I do find so much hope, actually, in the fact that the women didn’t change their minds and that they can hug each other even in the midst of that really despairing disappointment. It’s incredibly hopeful to me and something to work toward, I think.

SP: Yeah, absolutely. I’ve had a similar experience where it feels like so much rhetoric right now feels like peacemaking is for weak people or crossing the line, crossing the aisle is for people who are turncoats or weak or aren’t committed enough to these issues that matter. And in my experience, and certainly in the work of making this film, I’ve found that peacemaking is really gritty and it’s a long project of disappointment, often, and pain and grit and resilience. And the ability to persevere in that is a real sign of bravery and guts, and I think actually a commitment to a womanist form of reconciliation that provides real reconciliation in a way that I think our more masculine channels fail. The trial didn’t actually provide that much reconciliation for anybody. I think it probably deepened division. I think what this dialogue did is it provided an opportunity for healing and for a new way forward for an entire community generally, and for these women specifically. And they’re not still meeting, you know, they’re all octogenarians now and this dialogue hasn’t continued, but I think it could, actually. I think there’s hope that this type of conversation is still possible, and I think it’s certainly still necessary.

AA: Yeah. That’s so beautiful, and thank you for highlighting that too. I do agree. It’s way easier to stay in your own echo chamber. It’s way easier to cut off people that you disagree with. It takes much more strength to have difficult conversations, to dig deep for that empathy and compassion. I agree with you.

SP: Yeah, and if there’s anything that we can learn literally every election cycle is that the polls can switch. Your victory actually isn’t complete until you’ve turned enemies into friends, because things can change every single election. So whatever political victory you win is really temporary. I think that’s actually how I’ve begun to read the really famous scripture “Peacemakers will inherit the Earth.” Because it’s such a strange thing, the people who are out there making peace and bringing people together are the people who will win in the end? But I think that’s actually really true and really speaks to a fundamental human truth that political victories are almost always temporary. Things can change really easily, things can slip out from underneath you, and it’s ultimately the people who are out there building bridges and seeking peace and doing the really, really hard work of bringing together diverse people in a peaceable way that will actually win the day. It’s those communities that will survive the polarization and divisiveness and toxic rhetoric.

AA: Well, Sarah, this has been an absolutely, actually profoundly inspiring conversation today. As we wrap up, I’d love you to talk about your work. I would encourage everybody to follow you, learn about your work, and watch the documentary. Can you tell us where to find the documentary and where to find other work that you’re doing?

SP: Yeah, absolutely. You can find The Basement Talks for free on Tubi or on Amazon Prime if you don’t like ads. It’s available both places and I highly encourage you to watch it. And then you can see our other work, our theme for our production company is dealing with these really controversial, difficult issues in non-polar ways, trying to take a non-polar approach to talking about and thinking through these really difficult issues. So all of our other films are available through mattersmedia.com, and we have some really exciting projects coming down. We’re actually going to start working in February on a Global Peacemakers doc, people in really, really high conflict areas who were involved in peace negotiations there, including the Women’s Caucus at the Belfast Accords.

AA: Wow! I have thought about that during this conversation, I thought this reminds me of the Irish women. I’m so happy that you’re going to be talking about that. We’ll have to have you back on the podcast to talk about it, Sarah. That’s so exciting.

SP: Yep, it’s going to be wonderful. I’m so excited.

AA: Well, congratulations and best of luck with everything you do in the future. Sarah Perkins, thanks again so much for joining us today.

SP: Thank you for having me.

It’s either male politicians

or it’s the individual woman with her doctor.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!