“Allow these people dignity. Women are smart.”

Amy is joined by Lindsay Hansen Park of Year of Polygamy and The Sunstone History Podcast to shine a light on the painful history of Mormon polygamy, communities who still practice it, and the best ways to uplift and empower plural wives.

Our Guest

Lindsay Hansen Park

Lindsay Hansen Park is a women’s rights activist, a feminist writer, and an advocate against gender violence. She was recently the cultural and historical consultant for Hulu’s limited series, Under the Banner of Heaven and is currently heavily involved in the Mormon Feminist movement. Lindsay is the Executive Director for the Sunstone Education Foundation and the founder of the Year of Polygamy podcast. She wrote for six years at FeministMormonHousewives.org about women’s issues and now podcasts for the Sunstone Mormon History podcast. Her work has been referenced by the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, NPR, Quartz Magazine, and many other Utah publications. She and her family live in Utah where she raises three beautiful kiddos, gardens, and rages against the machine.

The Discussion

AA: How do you feel when I say the word polygamy? My guess is that if you don’t have any connection to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, aka the Mormons, you feel a sense of fascination with the other, a person who is completely foreign to you. My guess is that if you do have a connection to Mormonism, you also feel fascination. But added to that is a fear of knowing that polygamists are not the foreign other to you. If you’re Mormon or have been Mormon, it’s likely that you have polygamy in your very own family.

I remember the first time that this hit me. I was sitting with my family at the dinner table when I was about 10 years old, and we had invited over another Mormon family in our neighborhood in Denver, and my parents and the neighbor parents had recently discovered that they were distantly related and they were laughing at the dinner table because our families were descended from two different plural wives of the same husband. The adults in the room were laughing, but I remember feeling shocked. I had gone on a tour with my family of Brigham Young’s house in Salt Lake City, and so I had seen the living quarters of his dozens of wives, and I had also occasionally glimpsed children wearing long pioneer dresses when we drove to Utah in the summers. And honestly, I thought those people were weirdos. I had no idea that plural marriage had happened in my family, and I remember I kind of laughed because everyone else at the table was laughing, but inside I was reeling. My parents were acting like this was super normal, and for me it was very, very not normal.

From that moment, I would say that every time I thought about polygamy, I felt a lot of anxiety. I was afraid of the polygamy among my ancestors. I was embarrassed of polygamist Mormons, whom the mainstream church vehemently disavowed, but made their way into the news every once in a while. Those women with the puffy French braids would occasionally be there talking on the news, and I would feel mortified to be associated with them. I was afraid because I knew my own grandfather was sealed, which means married in heaven to two different women because my grandma had died and he had remarried. But most of all, I remember I felt afraid that one day I might die and Eric could remarry and I would end up sharing him in heaven consigned to an eternity of patriarchal subjugation and huge bangs.

This is a common experience for Mormon women, so it’s really no wonder that when Lindsay Hansen Park launched her podcast, Year of Polygamy, it exploded. Lindsay researched the stories of plural wives that had been hidden away in archives and brushed aside by religious authorities and left out of official histories, and she brought the history of LDS polygamy out into the light where we could see it clearly. The podcast now has over 170 episodes and more than 15 million downloads, and I am so excited to have the one and only iconic Mormon feminist historian and dear friend of mine, Lindsay Hansen Park on the podcast. Welcome, Lindsay.

LHP: Hi–thanks for having me. I’m a fan of your podcast, so it’s really fun to be on it.

AA: Oh, thank you. This is so fun. And I actually have to say too, Lindsay, I listened to Year of Polygamy, to a few episodes when it first came out along with everybody else, and it triggered so much fear and anxiety for me that I had to stop listening. So I have to say like as we have this conversation and you’re telling the stories, this is a subject that I have avoided because of that pain and that discomfort and fear. So for any listeners who are listening to this, like, oh, I’m embarrassed. I don’t know this stuff yet. I kind of don’t either. So anyway, I’m excited to get into it.

But first, if we can start with you telling your personal story, that would be awesome. Just tell a little bit about where you’re from and what are some big factors in your growing up that made you who you are today.

LHP: Sure. I’m born and raised in Salt Lake City, so I’ve spent most of my life in Utah, in the belly of the beast, or in Zion, depending on where you situate in the story. And my whole world was Mormon and I loved it. It actually worked really well for me. I was a white lady in Utah…it worked for me for a long time until it didn’t, and we can talk about that.

But I come from seven generations of Mormons on both sides of my parents to go all the way back to Nauvoo. It’s everywhere I know. It’s everyone I know. I thought the whole world was Mormon. I remember being in fifth grade when I found out my best friend was a Methodist, and you might as well have said she was an adulterer. Like it just sounded like such a dirty word. I didn’t know what it meant. I was so betrayed by that. Like, wait, what? Everyone I know in love is Mormon. Why aren’t you? That poor girl. You know, I’ve apologized to her years later, but that’s kind of how insulated I was.

I didn’t come from any sort of Mormon connection or leadership. My dad had only risen to the rink of the Aaronic priesthood, and he’s deeply, deeply introverted and shy. So the thought of giving a prayer was terrifying to him. The apocryphal story in our home is that he never blessed any of the babies. He never did any of the things, but he did bless me and he was so nervous that he threw up for days beforehand because of anxiety that his voice was so hoarse he could barely bless me. So I grew up with that, a dad that sort of didn’t fit even though he went to church, but like he avoided it. And I hate to say this now cause I love my dad so much, but I was kind of embarrassed by that. You know, I saw all these other families whose fathers were like doing all the things and sort of vying for power and status and my dad was very opposite of that. And so in some ways I think that I overcorrected in our family, I was like, well if he’s not going to do it, I’m going to be the one that’s going to go extra hard.

But another component to our family is, you know, we came from poor Danish farmers that immigrated to the church. While we did have some from Nauvoo, a lot of my dad’s family was Danish. In fact, my Grandpa Hansen grew up speaking the language. His own father and mother never learned English, even though they had immigrated here as Mormon pioneers. And so for me there’s a real rural component to my life. My mom’s side grew up pheasant hunting every year. My uncles all worship John Wayne, you know, and like all of that sort of white American ethos. And so I always was teased by my cousins and friends for being a city girl cause I lived in Murray, Utah, but I always felt like a country girl at heart.

AA: Huh. And that does just show also, if you don’t know Utah; Murray’s not a big city. So just for perspective, that’s just so interesting. That’s so telling.

LHP: You know it’s growing, now it’s closer to Salt Lake City, but in my world, it was like the big city. I’m a spoiled city girl. I mean, we didn’t grow up wealthy. We grew up sort of lower middle class. My dad worked for the gas company here as an accountant and he provided really well for us. But we grew up on the west side, which is like not the rich side. And so I think right away I sort of understood that the world was divided, that there were rich people and poor people. There were city girls and country girls. There were people in the church that were meant for power and those who were meant to work hard. And that was our family. We were meant to work hard, and so we tried to find joy in it.

My family was very devoted to the church. My mom is very active. I always tell this story, but she was very historically-minded and she loved to read and I credit her for helping me because I didn’t have a lot of academic or intellectual encouragement in my life. But she did read and she liked history. And so she would go to what we call the DUP, the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers Museum in Utah–it’s sort of like the Daughters of the Revolutionary War. It’s an organization where if you have pioneer ancestors you can join and then you can have your own little chapters. And so my grandmother was huge into the DUP. She ran one of her chapters, and you have to prepare lessons and histories from your family to present to people. And so my mom and my grandma and I would go to the DUP, we would research our ancestors, and then we would go to the church-owned department store called ZCMI, and we would go down to the little cafeteria and have egg salad sandwiches.

And I get nostalgic about it because it was just such a beautiful maternal memory for me–the way that we connected, we connected with our ancestors. And my mom would dress as a pioneer and go to youth conferences for the church, schools, all kinds of like local events and historical events and tell pioneer stories. And she was really good at it. So I grew up sort of at her skirts, learning the stories of my ancestors, teaching fifth graders to churn butter, to make taffy and all of that kind of stuff. I had my 8-year-old birthday at the Lion House, which was one of Brigham Young’s homes. We had a little tea party, but it wasn’t tea because tea is against the word of wisdom. It was…gosh, what do we drink? Punch. And I got a little porcelain doll.

So to me, I have a lot of beautiful nostalgia about the way that I grew up. Even though it was mainstream LDS, when we went to Brigham Young’s house we always knew the joke that he had, plural wives. Right? Like he lived polygamy. Ha ha ha. Funny, funny joke. And that’s all it ever was. And so I knew polygamy existed. I knew it existed in my lineage because some of my ancestors were that. But we never talked about it. And like you said in your beautiful introduction, I was probably in third grade when I met my first polygamous family and I didn’t know what to make of it. We were having a sleepover at one of my friend’s houses and there was this neighbor, this house across the street that looked really rural. They had tractors everywhere that a lot of property. And there was a little girl our age and we said, let’s invite her over. She looks fun, she’s got blonde hair, she’s wearing a dress…that’s weird. But we all wore dresses sometimes. So we tried to invite her over and she would run away from us. And it became kind of this mystery, like, why won’t she talk to us? What’s going on over there? And it wasn’t until years later that I was like, oh, that’s what it was. She was FLDS. And of course it took me years to get there…

AA: Tell listeners who don’t know, what does FLDS mean?

LHP: We’ll talk about it, but FLDS are probably the most prominently known polygamists in the world because they’re very easy to identify. They’re the women with the braids and the big hair bump and the prairie dresses, and in all the horrible true crime documentaries that you’ll see about polygamy and underage marriages. They’re called the Fundamentalist Latter-Day Saints, and it used to be an actual incorporated church. A lot of people will say FLDS to mean all polygamists fundamental of slaughter saints, but when I say FLDS I’m talking about the Warren Jeffs prairie dress group, and we can get into all of those distinctions a little bit later.

AA: Yeah, thank you for walking us through that. That’s really so relatable. I mean, you and I did grow up differently in that, like I said, there were enough Mormons that people had heard of Mormons where I lived and some people knew them. But yeah, it is really different to grow up in Utah. But then some things are so similar and I think it is interesting that you and I had such similar experiences in terms of like, we knew polygamy existed, but never talked about it really. So connect the dots for us, Lindsay, between that moment with the girl that you’re like, Hmm, prairie dress and also polygamy exists, and I had my birthday party at the Lion House…Connect that to you deciding to start Year of Polygamy. How did you evolve in your relationship toward polygamy and what made you want to research it in depth?

LHP: Sure. I don’t know how it was for you, but for me, polygamy was brought up throughout my life, but it was a joke. It was always sort of in a joking context. Most often I heard boys joking about it. I grew up in a neighborhood that was all mostly Mormon. There were 26 kids my age in my grade alone. We just ran around like little misfits. I mean, it was all very innocent, but those boys would sometimes joke that they would get to have multiple wives someday. And I always loved to laugh at their jokes, but not that one…And I didn’t know why. I just thought, that’s not really funny. Like, I don’t get that.

I was always very concerned with fairness too. That was a huge part of it. And so the fun fact about me is I was part of one of the very first only girls basketball teams in Utah, in the rec leagues. Because when I was young, they didn’t let you play basketball with the boys. And so they said, okay, if the girls want to play. Murray City established an all-girls team and they made us play the boys’ teams to prove that like we really wanted it, I guess. And we just got crushed every time. But like we didn’t care. We were like, we’re at least going to make it hard for you.

AA: Love that.

LHP: And so I took that attitude with the neighbor boys. I would sort of challenge them on it and whatever, but I remember I had another story…which is I had an aunt live downtown in Salt Lake City. She was getting dementia. And she would call my mom and my grandma and my aunt up and be like, the polygamists are going to kidnap me. They’re going to kidnap me. And we’re all like, oh, she’s getting old. But I remember thinking Polygamists were scary, you know? That’s kind of what I got. I remember the little girl running away. There was just something scary about it. And it wasn’t until I got married and I married into a more, I would say, conservative family. They’re definitely rural, southeastern Idaho, so they live a very rural life. They have very rural values, very rural interpretations. I would say that their views were more aligned with fundamentalist views when it came to priesthood and race and issues of gender. It was very, very conservative. And so that was my first like, oh, there’s a different kind of Mormonism here that’s even more extreme.

And when I would push back on any doctrine, first of all…women don’t push back on doctrines. You’re not supposed to do that. So that wasn’t always well received. And second of all, I think that there is this element of…I would say, I remember there was a discussion of if Black people and white people could get married in an LDS temple. And I was like, well, of course they can cause I’ve seen it. And their family was like, no, and here’s the doctrine and here’s what Brigham Young said. And it was kind of like, what do you do when your feelings or experiences are trumped by a prophet and it’s irrefutable? So that was my first like, oh, I don’t like this. This is starting to bother me, but there’s nothing I can do about it.

And my husband at the time, we’re now divorced, but at the time he would make some jokes about polygamy every once in a while. And famously it was a time when I was having a really bad day, the kids were. Having a hard time. I was just feeling, you know, as a young mom, you just feel gross, not pretty, and just sort of worthless. And I burned the dinner. I was making dinner and I burned it and my husband made a joke and he said, that’s okay. I’ll find someone in the next life who won’t burn their dinner. It was a joke. It’s a joke that I’ve heard a hundred iterations of that growing up, but something about it really pierced my heart and wounded me. And later on, I remember watching a PBS documentary on the Mormons. My baby is laid out on a blanket on the floor. I’m getting stuff ready for our church women’s group called Relief Society. And I see a quote about Brigham Young’s polygamy, and I’m just like, wait, that’s not what I thought. That can’t be right.

So I started researching and I started to get angry because all of these things that I’d bumped up against that you sort of laugh off and then it gets worse, then it gets less funny, and then you know, it starts to canker inside of you. It was laid bare in this information. I knew how to research because my mom’s a good researcher, right? But my mom’s stories never talked about that kind of stuff. They always had a faith-affirming punchline at the end, right? We went through all this suffering. Your ancestor did all these hard things, but in the end, it brought her closer to God. But when I started researching, it was opposite. The stories were opposite of that, and I was really, really angry and I just kept thinking, this is so unfair. I have to be a polygamist in heaven even if I do everything right. So in modern LDS doctrine, it’s basically, we don’t talk about polygamy, we don’t like it, we don’t believe in it, we don’t practice it anymore, however—big, however—you will live it in heaven if you do everything right, like that will be your great reward. And if you’re like me, I’m like, explain the reward part again, I don’t understand.

And it was compounded by another issue, which I’ve talked about before, which….it seems so silly an adolescent at the time, but it was such a huge deal to me, especially like in my twenties when I got engaged to my husband, I was actually in love with someone else, a missionary that I had waited for. So LDS missionaries at the time, it was mostly men that were encouraged to go. Women like me were encouraged to stay back, write and support these missionaries, get ourselves in shape to become a good wife; don’t gain weight because they don’t want to come home and marry an uggo, and keep yourself spiritually fit and physically fit. And so I was committed to that. I wrote this guy every week, I developed an eating disorder (big surprise). I was really stressed about him not wanting me because I wasn’t spiritually fit. I started only reading church books. And so when he got home I had met my husband and I had two of them and I didn’t know what to do.

It was really this two-week time period, everyone in my ward getting involved. They’re putting pressure, which one are you going to choose? You have to choose one. And you know, looking back, if I could have just like ran away for a year to get away from that… but I prayed and the answer I got was to marry my husband even though I was in love with someone else. And I really thought that because it was a prayer that it meant that it would be okay. But it wasn’t okay. And you know, my poor husband, there was nothing wrong with him. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time, living out the lessons he had grown up with. But I struggled because I kept thinking about this other person. I broke his heart; he was confused about it. And it was about six years into my marriage, I had still had these lingering feelings and questions for this other person who now I realize it wasn’t even about him. It was just—he represented choice to me.

my husband made a joke and he said, that’s okay. I’ll find someone in the next life who won’t burn their dinner

I went into my clergy, to my leadership, because they were asking me for a calling. And a calling is like a job they give you in the church. But to do a calling in the Church, you have to be worthy. And I felt unworthy because I had feelings for another man. And so I confess this, I say, “I’ll take this calling, but you should know, like I have this feeling.” And it was a stake president, counselor, cause it was a stake calling at the time which is higher level, he carries more authority. And the guy just got like…his eyes lit up, his face lit up. He got really excited and he was like, oh, that’s all it is? Oh, you’re fine, you’re fine. And all of a sudden that shame that I’d like bolster for six years starts to dissipate. And he was like, I have been in the same situation. I went through it too. And he was like, it’s very common. You have no idea how common it is. And I said, “oh really?” And he was like, oh yeah, you’re fine. And I said, “well, how did you make sense of it? Tell me something that will make me feel better cause it feels awful.” And he said, I was in a lot of pain about it too, Lindsay. But then I prayed and God told me that this is just God preparing me to take on more wives someday. And so my feelings aren’t bad. They’re natural because they’re preparing me for that. And he smiled like See? I fixed it. I fixed it. And this such a powerful moment in my life. It was this like inciting event for me. I remember seeing the picture of Jesus with the red robe, you know?

AA: Mm-hmm.

LHP: Sitting behind him, just staring at the red as he’s looking at me like, I’m cool, right? I fixed this for you. And I just remember thinking, how does this help me? Like, wait a minute. You get to do that as a man. How does it help me? And it just shattered everything in my soul. I had so much faith in this man and in his authority and in this story, and he just couldn’t see it, that it was so inequitable and my pain was so real and so profound for me at the time. And so that kind of was just like, what do I do with that?

And so eventually I found a blog called Feminist Mormon Housewives. It had been around I think less than a year. And my husband and I, we were camping and we were coming into town for supplies and the radio was on. And there was an interview with Tresa Edmunds, my co-blogger. She was one of the bloggers, and she was talking about being a Mormon feminist and how it’s not incompatible with religion. And my husband’s like, let’s turn this garbage off. And I was like, no, no, no. Wait, wait, what? Wait, what? And I made him stop down on the mountain so I could hear the interview. And he got too uncomfortable with it and turned it off when we went camping and finished our trip. But I remembered the name. So I went home after and I asked my non-Mormon friend who I’d grown up with—she had grown up in the church with me, but she had left when she was 18—I was like, “Hey, will you Google something for me? If I do it, it’s bad, but if you do it maybe it’s not.” And she Googled it and she was like, oh yeah, it’s a blog and here’s what they’re talking about. And she’s like, you’ve got to look. I don’t think it’s bad, Lindsay. I don’t think it’s bad. I think that they’re all faithful members.

So I get online and just for the first time in my whole life, someone was talking about something real. You know, I tried to talk to my mom about polygamy and these questions, I tried to talk about it with my sister-in-law’s, the connections of women around me at church…and it was always the same. Don’t talk about it. The fact that you’re talking about it is making me uncomfortable. And if you make me uncomfortable, we’re going to distance ourselves from you. So this was different. It was women talking and talking openly and you know what they were talking about? They were complaining about motherhood. That’s what I remember reading. I had one child at this point and I was having fertility issues and I was really struggling. I had had horrible postpartum depression. A lot of women I knew had that. We were not talking about it, but everyone was suffering. And so to hear women be like, you know what sucks? Waking up at 3:00 AM and then at 4:00 AM and then at 6:00 AM and being covered in milk. I just couldn’t do that with the women that I knew in my lived life. And so I started commenting and it wasn’t long before they asked me to start guest posting, and then I became very quickly after a blogger, I went by the name of Winterbuzz. And that cracked open my world in ways that we did not anticipate.

We started blogging for a while and we all had pseudonyms. We really felt like there were maybe 400 of us reading, and I didn’t realize how many people were reading it at the time, but it felt very small and very safe. And then Mitt Romney, when he ran for president, it became this Mormon moment and all of a sudden The New York Times wants to talk to us. The BBC is coming into my living room. It blew up. Mormon activism blew up. It was actually 11 years ago yesterday, I think that the wear pants to church movement happened… Do you remember that?

AA: Of course, I wore pants to church. I was terrified. My nervous system was so activated. But yeah, I did that in my California ward at the time.

LHP: It’s still to this day probably the most heretical thing I’ve ever done, and I’ve done a lot of heretical things. And so for those who don’t know, Mormon women are expected to wear church dresses, right?

AA: Mm-hmm. Sunday best.

LHP: Which means dresses! I mean, okay. So it’s changed recently, thank goodness to good Mormon feminist women who have pushed this through. But at the time, for me, you just didn’t do that. You didn’t do that at all. And we were talking about, well that’s kind of dumb. Like you can buy designer pants suits now that are way more expensive and nice than a church dress.

So if we’re talking ‘best’, what does ‘best’ mean? If you’re in a nursery—which is where the babies are that you’re supposed to take care of during church—you’re bending down, you’re opening your legs, doing stuff that would be immodest in our doctrine. So why can’t we just wear pants?

And we were just talking about it and it turned into a movement because the pushback when mostly Mormon men at first found out that we were talking about it, got online…and that was the first time I’d ever gotten a death threat. You know, like that’s the first time our blog, the women got death threats. Some of the organizers, Steph Gary, she was one of the main organizers, and her life was shredded at that time. And she’s the sweetest person ever, you know? So it was kind of like all of a sudden that’s when my bishop finds out about me, and that’s when my family finds out what I’m doing. And that’s kind of when everything fell apart for me. But it was also such a beautiful time because if you’ve ever spent, I don’t know, 30 years of your life feeling like you’re surrounded by people, but you can’t talk to anyone about anything. To have that lifted was the biggest gift, I think, of my life. And those women from Feminist Mormon Housewives will always be my family in some sense, because they lifted me from these like gallows that I was living in.

AA: Mm-hmm. Well you impacted my life in a big way too, Lindsay cause it was about, around that time, 2012, 2013, 2014…That’s when I discovered the Exponent and Feminist Mormon Housewives. And it was a similar feeling for me. You had already been doing the work for a while. I had been in agony all by myself, trying to puzzle through it, reinventing the wheel for the first time, not knowing that other people had thought about it and done all this work. Anyway, that’s when I discovered the work that you were doing. So take us from Feminist Mormon Housewives to then specifically deciding to research polygamy and start the podcast. What was the impetus for that?

LHP: Yeah, so polygamy had always bothered me ever since I was married because of these issues. And so when I first joined, I don’t think we were talking about polygamy, but the exponent was. And so I started reading their archives and this is when I learned that Joseph Smith had multiple wives. I found this out through my research. I think I was in my late twenties when I found out, and I was like, wait, what? Which people laugh about now! They’re like, well, you knew another Mormon prophet had multiple wives, but not Joseph Smith? My generation grew up with Joseph Smith, the founding prophet of Mormonism, and his beloved wife, Emma. There are statues of them downtown. We would go there at least twice a year for youth activities, stand gaze at their beautiful love story. It’s depicted in a movie that we saw often as kids. It was upheld as a perfect love story. So to find out…that was just so confusing to me. I didn’t understand, and then I started to get angry. I was like, wait a minute, okay, if the doctrine is true and it’s this important and it’s this foundational, and that our foundational prophet was bringing it to the world and he suffered and died for it. Why don’t we know about the women who are with them? That’s weird. Why are we so shameful about it? And I’m kind of mad at like my own mom and my own family, and I’m like, you talk about these women and all these stories, but not these other ones because they were doing what they were supposed to do, what God commanded them. That’s wrong.

It just didn’t make sense. And so someone said, well, have you heard of Todd Compton, who’s a historian, Todd Compton’s book In Sacred Loneliness. He’s written a short bio about all the wives of Joseph Smith. And I was like, what? That exists? So I read it. And it changed my life. There are a few books in this world that have absolutely changed my life and that was one of them. And so I was like, people need to know about this. So I started doing an adaptation of his book for the blog with his permission. He’s such a lovely person. I give him credit for really helping me get started. Cause I dropped out of school to have my babies. I quit my job to have my babies. I felt like a dumb bumpkin, like I wasn’t a scholar. I didn’t think like a scholar. I knew my mom’s history. I knew how to prepare a faith-promoting story for Relief Society. I did not know how to deal with real histories. And it became clear very early on as I was writing about it that my intelligence was constantly attacked because I’m dyslexic. I spell words wrong, I read things backwards, kind of out of order. And so people would come and that was their first thing. This girl is dumb. We don’t have to listen to her. And it was mostly faithful Mormons, just saying, look how dumb she is. She can’t be trusted. And you know, I had women mentor me on that. They became sort of my midwives into like, here’s how to talk about it better.

When I started the podcast—which followed the series, the series became really popular—and at this time we have a few Mormon men who started podcasts. So John Larsen was one of the first. And John Dehlin followed after, and I think Dan Wotherspoon had one at a time. There were a few, but they were all men. And our whole thing at Feminist Mormon Housewives were women’s voices. And we had already dealt with the male blogs, a lot of Mormon scholars from Mormon men blogging. And they would be like, we’re talking about the serious big kid stuff, doctrine and priesthood, and the women are over there at Feminist Moron Housewives talking about diapers. Like that’s not important.

And so it just triggers that sense of fairness. Like me being a kid playing the basketball team. Like okay, the game is rigged but we’re going to make it hard for you. So we were kind of like competitive about it. Like, oh, you think we’re not important? And so when Mormon historians who are male who would criticize how dumb I was, I was like, I’m going to learn this and I’m going to learn it well because you and I both know that the point of what I’m saying isn’t wrong. All you can do is attack what I’m saying. And it’s just, it’s so inefficient. It’s getting in the way of like…come at me. Hate me. Come at me all you want. But what I’m saying, you can’t argue with.

And so it took me a long time. I’m still learning. The field is always changing the leveling up. But it took me a while to realize how to tell the story in a way that people would listen. The very first thing I learned was that you need to use faithful sources if you use an antagonistic source against the LDS church. So, an example would be, if I’m writing about polyamory in the 1850s, I’m not going to use a newspaper from an outsider, I’m going to use Brigham Young’s own sermons.

AA: Yeah.

LHP: And so I started the podcast, cause I was like, we’re going to do a women’s podcast, we’re going to do this and I’m going to do a series. It first started out with a podcast about Feminist Mormon Housewives. We would just talk about exactly what we’re talking about on the blog. And it was getting really, really popular. And so I was like, I’m going to turn the polygamy, the wives of Joseph Smith thing, into a series and I’m going to call it a Year of Polygamy and it’s going to be called that, not because I’m practicing it…everyone always asked me that, like, did you try it for a year? But I blogged about it. The intent was to blog about it for year as a series and then continue on. And I only used faithful sources, which now that I know what I know about history and the breadth of my work, I’m like, wow, Lindsay. Like, good job little Lindsay. Back then that was pretty clever because there’s so much more to pull from, but I was able to write such a compelling case using our prophets own words….that’s pretty cool. Like I wish I could go back and tell Lindsay like, you’re not dumb. Don’t listen to them.

But I did. I felt dumb. And that sort of motivated me to be less dumb. So we did the podcast. The podcast blows up and I think it’s because you can hear me lose my faith in the podcast. I start it out very, very naive. You said in your introduction you avoided things that were hard. You avoided this topic. I have a different impulse and it’s not a good one. It’s just kind of like go towards the things that scare you, but like go hard. And I think part of it, the reason why I wanted to tackle it was all this repression pent up and I was just kind of like, okay, we can face this. And Mormon feminists had taught me something else, which was if these women chose it—freely of their own accord—if there was consent involved, then we have to respect that.

And I hated that argument cause I was just like, man, I don’t want that to be true. You’re all telling me that these early plural wives chose it? Why would you choose that as a smart thinking woman? But I really had adopted that feminist ethos, which was women’s choice. And women can choose differently than I do.

And so I was really naive with that, not because the foundations of that belief are wrong, but because my data was wrong. But when I started the podcast, I was just kind of optimistic about it. I was like, well, if they liked it and they chose it and they thought it was good, cool. I don’t need to stress about them anymore, but let’s just get into the history and we’ll figure it out.

AA: Mm-hmm.

LHP: And so I opened with this really naive, like, Hey guys, we’re going to figure this out together and it’s not going to be that bad. I think it’s really like episode 28 in the late twenties that I start to go, oh, no. Like, oh no, they hated it. These women that said that they loved it. They hated it. I remember I was doing an episode about women’s suffrage, and for those who don’t know, Mormon polygamy got women, white women, the right to vote in the United States. Now it’s complicated. What had happened was polygamy was linked to slavery, so the modern Republican party also got its start linking to Mormon polygamy because they ran on a platform: the twin relics of barbarism, slavery and polygamy, and they saw Mormons were a scandal at this point in the 1850s, 1860s. They were a national scandal. They were tabloid fodder, and everybody was talking about them. So suffragists over on the East Coast, were like, Hey, we’re not getting the traction we want. What if we test the vote in the territories over in the west? And you know what? Those poor Mormon women over there, we can help them. And if we help them, if we show that the vote can help women, it’ll convince everybody that, Hey, we’ve solved the Republicans’ problem with the vote.

So they give women the vote in Utah territory and they collaborate with Mormon plural wives like Emmeline Wells and Martha Hughes Cannon. And they get this vote passed. And then Mormon women don’t vote the way that they want. They vote to support the Church’s interests. And so the vote is taken away. Mormons get disenfranchised because of polygamy, and the vote is given to women in Wyoming.

AA: Mm-hmm.

LHP: And then when I say women, of course I’m talking white women. But people don’t know that. And so I’m reading about Emmeline Wells, Martha Hughes Cannon—Martha Hughes Cannon is baller. She’s the first female senator in the country ever in the United States. And she was a polygamist. She was a plural wife. She actually ran against her own husband in the campaign and one, which is amazing. And she becomes a senator. And when you read her writings, when you read Emmeline Wells’s writings and other contemporaries, they’re pro polygamy. They’re talking about the virtues of it. They make what I would consider feminist arguments. Feminism is postmodern, you know? But for them it was like, it’s built in childcare. It allows me to become senator.

That’s hard to argue with, and so I’m talking about this on the podcast. Look, these women are saying that it’s empowering to them. We have to believe them. Then I got Martha Hughes Cannon’s diary and started reading that her personal letters and that was another moment where something shattered for me. I’m sorry, I get emotional about it. Like I could read her pain in the paper. You become so attached to these women, they’re like your community, because I spent every day with them and with their voices and their internal dialogues. So Martha Hughes Cannon hated polygamy. It hurt her often. And I was reading letters between her and her husband. And one of the letters specifically, I’ll never forget, he was in a carriage taking on a new prospective plural wife—or he had just married her. I can’t remember—and Martha Hughes Cannon sees it, and she’s trying to get time and attention and the little resources from her husband to help her and her kids. And he’s just busy courting his new wife and she writes, “how do you think I feel when I see you with her?”

She loved her husband and Emmeline Wells, who was her other contemporary and a suffragette, she would say “the key to polygamy, the key to successful polygamy is to not love your husband. If you handle that, you’re good.” And I remember thinking, well, that’s messed up, but okay. I know a lot of Mormon women that don’t love their husband. I didn’t have to confront that yet, but it was Martha Hughes Cannon. She loved her husband and it broke her heart. And so then I have to go, Wait. Publicly they would say one thing, but privately… it sort of opens up this whole discourse of 200 years of tradition of my Church saying one thing publicly and doing something else privately. And the razor-sharp edge of that is cutting up the hearts and souls of women and they’re writing about it in their diaries.

And so that’s really when you hear me go, I’ve made a terrible mistake. And so then the rest of it is me confronting that. And then eventually I get into…it’s chronological, it’s designed to start with Joseph’s wives and then move forward. And I get into modern day stuff. And that was its own adventure that I spent the whole decade of my thirties in this mess of meeting with and engaging with and talking with fundamentals, going to compounds. I have access to some of the most isolated compounds, cults, groups, whatever you want to call them in the American West because of this. Because as I researched it, I think the pain in the questions were so deep and so acute inside me that I thought, I have to find every angle of this to make sense, because when you’re as faithful as I was and your whole world is this, it’s not just easy to walk away from it. You can’t just rocket yourself into space. To build that rocket for some people takes a long time. And for me, I had to get every piece and component. It took a long, long time, and in some ways I’m still unpacking it. But yeah, that’s Year of Polygamy.

200 years of tradition of my Church saying one thing publicly and doing something else privately

AA: Amazing. Yeah, I’m still unpacking it too. And as you know, Lindsay and I talk about it occasionally on the podcast. For me, we’re only doing this episode right now because of what we talked about it a minute ago; that it’s just too painful for me. And I have taken kind of the bird’s eye approach. Like I just want to understand patriarchy broadly. I want to understand it everywhere. And there are these pockets of personal pain that have been just again…yeah, it’s just too painful for me to like shine the light there. But that’s what we’re doing today is like, okay. I think I can confront Mormon polygamy now a lot more easily just because I have tools to process that pain. And that is, I think, the most extreme overt manifestation of patriarchy that exists, again like I said in the intro, in my own family, in my own ancestry.

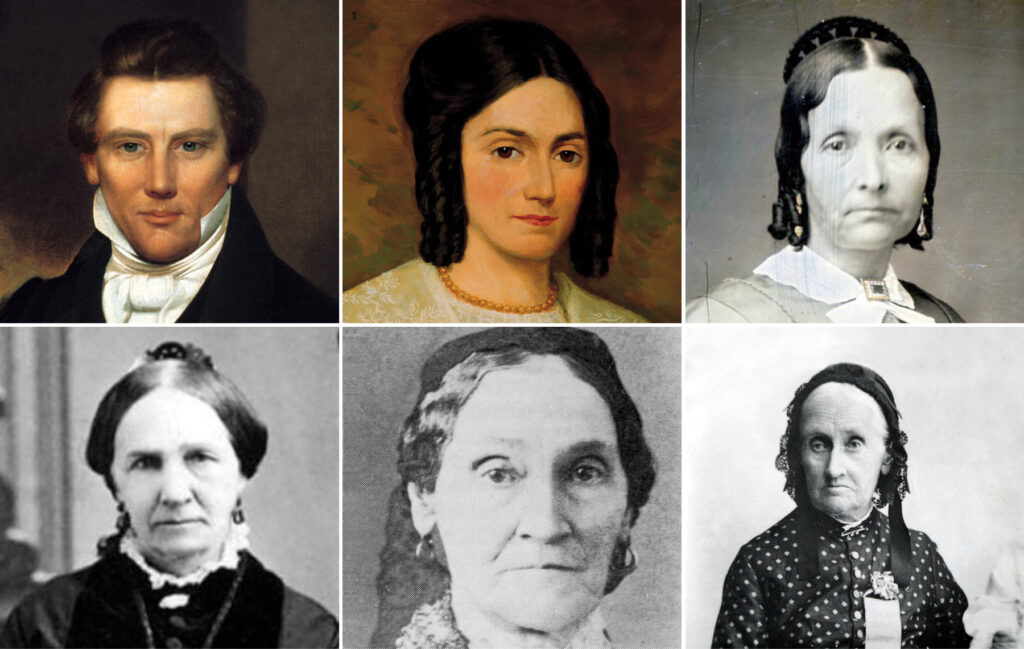

I would love to have you just briefly, you talked about, and I’m so glad you did, Martha Hughes Cannon, Emmeline Wells, and the connection to the vote. Such an interesting history, so listeners should dive into that more. If we can back up and have you just introduce how polygamy was instated by Joseph Smith and maybe a couple of stories of his first wives. Let’s go to those beginning stories and then we’ll kind of leapfrog over the middle and have you talk about more of what you just mentioned, which is your work with communities who still practice plural marriage, cause there’s some really interesting and important insights that I know you’ve gained through that work. So can we do beginning and end?

LHP: Well, it’s complicated. The origins of polygamy are hotly debated within Mormonism, and so it’s tricky because usually I give the answer that I would give to Mormons, which is very nuanced and complex. It gives a lot of context so they understand.

AA: Mm-hmm.

LHP: What I’ve learned now that I do a lot of work consulting and film and working with outsiders…they don’t care about any of that. Like the assumption that Mormonism is false or Joseph Smith is, you know, a charlatan or whatever. So you don’t have to do any of that. So I’m going to kind of go in the middle and tell you just a quick version.

Joseph Smith claims that he was approached by God in at least as early as 1831 to bring in what he saw as a biblical reinterpretation of polygamy. He claimed ancient prophets did it. A lot of Christians get mad when I say that. I’m just telling you what Joseph Smith believed, and that it was his job to restore it. Joseph Smith is a restorationist. He believes he’s restoring old things back onto the earth, and polygamy was one of them. In 1831, he allegedly has a revelation that says that his men, his counselors, would be okay to marry what they call Lamanite women, which was indigenous Native Americans, as a way to colonize them and convert them to whiteness. Which is one of the, the goals of Mormon Scripture, the Book of Mormon; convert Lamanites, who Mormons see as indigenous Americans, most Mormons see that, and convert them to God and bring their curse, the darkness of their skin to ‘white and delightsome’ as the term that we use.

So he has this revelation. And then in the late 1830s, he has a 16-year-old housemaid. Her name is Fanny Alger. She worked for him, and at the time, his contemporaries saw this as an affair with the young girl, but a lot of faithful Mormons see it as the first instance that Joseph Smith took a wife, a plural wife. People have retroactively tried to mess with certain ceremonies that would make that legitimate, but as far as I’m concerned, it was an affair. I think the evidence shows that it was an affair. His friends, certainly his close friends, Oliver Cowdery, for example, who was faithful at the time, called it a “dirty, nasty, filthy scrape” or “affair” depending on the source that you’re looking at.

And then, you know, he practices it. Secretly, he gets involved with masonry in some ways. He gets involved with…there was a famous anti-mason…so the Masonic lodges were a big deal in the post-Revolutionary War. It gave men a sense of power and control in like secret societies. And so there was a big Masonic lodge in Nauvoo where Joseph Smith was setting up town. He knew an anti-mason who was trying to expose the masons. He gets murdered and Joseph Smith secretly, allegedly marries his wife. He starts marrying women that are close to him or close to the men in his community. And it’s all very secret. When he marries, his–who Mormons at the time would’ve seen as the first plural wife—Louisa Beaman, she dresses as a man and he dresses as a man, and they have her brother go and secretly marry them under a tree, which is such an interesting gendered idea.

So yeah, so he starts doing that. He acquires…we don’t have good numbers. We really don’t. It’s hotly debated in Mormonism, anywhere from 29 to 50 women. I like Todd Compton’s, number 32 or 33. They’re women who self-identified and we have pretty decent documentation on those marriages. And so he does that. And he’s married about a dozen wives when his wife Emma finds out. So I should mention she didn’t know it was a secret to her as well. And one of the patterns that Joseph Smith had was bringing women into his house. At this point in time, he’s living in what’s called the Nauvoo Mansion. It’s sort of a big estate in the city that Mormons have established in Illinois. Nauvoo, Illinois. It’s a Mormon city. It’s rivaling numbers of Chicago. It’s about 10,000 people. So it’s a big bustling metropolis. And anytime a girl was orphaned or in a dire situation, Joseph Smith would volunteer to have her come work in the house and be an assistant. He has children with his own wife, they can help with children. And we see a pretty consistent pattern with several of those women that Joseph Smith chooses them as, plural wives. They were underage, meaning under the age of 18. There are the Partridge Sisters most famously as part of this, they had money and they were sort of displaced from their parents’ situation and death. And so Joseph Smith puts them in his house, offers to marry them both. They don’t want to do it, but he convinces them. And then Emma Smith finds out about polygamy.

Joseph Smith allegedly has a revelation that he gives Emma Smith that he says comes from God. So he says he prays to God. God tells him that he’s going to send an angel with a flaming sword to kill him if he doesn’t do this hard thing. Joseph claims like, I don’t want to do this. And the hard part about that is Joseph Smith…the idea of him not wanting to be with other woman is interesting because as early as I think 1828 or ‘29, after he marries Emma Smith, it’s like within a year or two, her best friend, Emma Smith’s best friend is accusing Joseph Smith of trying to get with her. And he’s dragged into court over impropriety with women. And if you believe Grant Palmer’s research, he has had dalliances with prostitutes over the course of his life. Sarah Pratt famously says that there was a steamboat madam that was very acquainted with Joseph Smith, and so this idea that he was the reluctant polygamist is kind of offensive actually, but that’s what LDS people hold to; He didn’t want to do it. It was hard, but an angel said he had to or he would die. And an angel also says that his wife, Emma has to accept it or she’ll die.

And when we’re talking about death, we’re not just talking about spiritual death. In Nauvoo, there was a secret society of men called the Danites. A lot of LDS people were like, no, there’s not. But you can’t prove that you can. We can. We have. We have all these people that were involved, including Porter Rockwell, one of Joseph Smith’s most beloved hitman, if you will. They were going around and they were called the Whistling Whittling Elders. They would threaten you and they would whittle their knives and whistle until you got out of town. And if you didn’t, they did horrible stuff to you. I mean, we have examples. In my new podcast, we talk about this; the Sunstone Mormon History podcast. We talk about what they called ‘privy dirt’. So a privy is a bathroom. Privy dirt is what goes in to the bathroom. Mormons would to apostates, they would take and bathe you in privy dirt. They’d put it in your mouth. And that was the nice thing that they would do to you. Hosea Stout was known for poisoning people. And John D. Lee talks about how they have a bishop, Bishop George Miller, who they think he’s going off the deep end and they’re plotting to off him.

I mean, these were frontier guys breaking the law, living outside the law. And it’s taken me…Amy, it’s taken me a decade to even admit that I can add all this nuance to it, but to say that our founding prophets and my grandpas were outlaws. It’s really hard. They were counterfeiting. They were having all kinds of problems. It was kind of an organized crime. And so they get this revelation, they bring it to Emma, Emma says, No, no. But she’s threatened with the penalty of death. And I think that that penalty was pretty tangible, more tangible than we realize. A lot of faithful historians will hate that I say this, they’ll disagree with me. I think I can make a very good case historically that that threat was pretty prominent for her. She waffles back and forth. He says, okay, I’ll let you choose who my wives can be. And she chooses the two Partridge sisters that live with them in the Nauvoo house, not knowing that they’re already secretly married to him, as are some of her best friends.

So he actually marries a lot of her best friends in the Relief Society. She starts the women’s organization, the Relief Society. He is secretly married to some of her counselors, including Eliza R. Snow at the time. So they perform the sham marriage with Emma there. He remarries these sisters. The idea is that she allowed it because she could have better control over it because she was sort of their boss. But the girls will talk about how Emma, the minute that that ceremony was over, she hated those girls and made their life really hard for them, and they say it was sort of some resentment.

So there are over 33 stories like that, and that’s what we sort of talk about in the podcast. So that’s how it gets started. There is an overwhelming amount of evidence that it was practiced, even though it was secret because Joseph wasn’t the only one. He got his contemporaries involved and so his own scribe, William Clayton, where we get a lot of the contemporary evidence; Joseph Smith often told him to burn things that he did not burn. Thank goodness. William Clayton was also a polygamist, and so were most of the top men in Nauvoo. And so it formed a secret society that would remain kind of a bad kept secret until 1852 when Utah Territory gets involved and the Mormons are forced to leave Nauvoo because they want to live outside the law.

AA: Yeah, and that’s the beginning. Oh, and yes, people should just go listen to the podcast, but where my mind is going also is like…yes, thank you for that amazing introduction and then all of those middle years that we’re not going to really talk about. You talked about suffrage and some of the prominent names, but I’m just thinking, am I ready to go back through my like family history chart, to look at where my ancestors fit into this story? And another moment for me as I was growing up where I was like, oh no, was my great-grandmother whom I knew really well, she didn’t die until I was in high school. I remember at one point me probably when she died, and I was maybe looking at the program at her funeral, said that she was born in Mexico and I knew she had like lived in New York City and she had lived in Salt Lake City. And I was like, wait, why was she born in Mexico?

And I don’t know if it was my dad or somebody else was like, oh, well yeah, when polygamy was outlawed in Utah, a lot of people went to Canada and a lot of people went to Mexico so that they could continue practicing polygamy. And I was like, do you know what? Please don’t tell me anymore. I don’t want to know about that. And I still have never looked into it. My own great-grandmother, and I know that her parents were not polygamists, but I’m guessing our grandparents were. I don’t even know. I haven’t looked at it yet.

LHP: I can do that research for you pretty easy. I host a podcast now, Sunstone History Podcast. And my cohort, Brian and I…Brian’s got like a photographic memory and so he can tell you, literally, you can tell him the name and he can tell you how they’re related. But I can tell you like if you, do you know what colony she was born in?

AA: Was it Juarez? Was Ciudad Juarez one of them?

LHP: That was the biggest one.

AA: That was where she was born then, yeah.

LHP: I want to look into it too, because if she’s that age born in Mexico she could be a daughter of a post-manifesto marriage, which is really exciting for historians like me. So, post-manifesto…in 1890, the church comes out with a manifesto saying, we’re not going to practice polygamy, we’re letting it go.

And then they continued to marry in secret. Those are post-manifesto marriages.

AA: Well, after this is over, I’ll text you her name and with my hands over my eyes, like, I want to know but I don’t want to know! It’s so, it’s so hard.

Okay, so let’s end by talking about current communities where plural marriage is still practiced. And I have to say, like opening the episode by even saying like, I thought that those, you know, plural wives were weirdos and like those communities. I felt a lot of kind of revulsion, honestly, like disgust mixed with pity. And I think it came from fear. Cause again, it’s like, oh, does that mean I am going to have to do that? It’s too close to me. And so I reacted with disgust instead of just curiosity. And it’s honestly been through you, Lindsay, that you’ve kind of held up a mirror to that in me a little bit. Not intentionally, I think, but just the way you handle it and the things you say.

You actually introduced me to some women that practiced plural marriage. That was the first time in my life I’ve ever talked to anybody. I don’t even know if I told you that at that event, where I talked with this woman for a long time and my brain just kept almost like short circuiting, cause I’m like, oh, she’s normal and she’s so nice. And we’re just talking. And then it’s like, she’s a plural wife. And, and my brain would be like, oh, I could feel the process of othering, humanizing, othering, humanizing. And it was actually really, really important I think, for me. But anyway, I’d love you to talk a little bit about those communities, the work you’ve done with them and what you’ve learned as you’ve done that work.

LHP: Sure. So as I got into the podcast when we got into more modern times, I started doing the background of post-manifesto, the church moves away from it. The people start going rogue and doing their own thing. And we get these schisms, these splinter groups, if you will. And so diving into the history, I like you, I had this sort of revulsion, I thought there was something wrong with them. But then when you hear the history, and it’s actually a pretty strong case for like, if I knew about the history, it would’ve made me believe like they did because they actually have a pretty good lineage for why they practice it. And when I say that, I mean historically, like…I don’t think any reason is good enough for that. You know, I don’t like polygamy. I’m not a fan of it clearly. But because I was honest and fair with their history, I think that it was the first time they’re like, okay, there’s an LDS woman who’s being honest about it and she’s being fair and they don’t agree with my harsh critiques of religion or Mormonism or Joseph Smith or my interpretations, but I think I was one of the first voices they had heard ever just telling their story and giving a logical like explanation for why they believe what they believe. And I think that that appreciation has bought me some lifelong friendships with people.

our founding prophets and my grandpas were outlaws

And I will say that I have found that fundamentalist people are way better at disagreeing with me about my faith positions than my own community. And I think it’s because they’ve been marginalized, right? They know what it’s like to be as a weirdos. And so in some ways they’re a lot more open-minded than our community is. And that was really refreshing to me. So, yeah, I got invited into their homes, their houses. I spent a lot of time in these communities. One of the things I did early on was realize, especially in Short Creek, I was in there before all the transitions, I was in there around the time that Warren Jeffs was imprisoned.

So 2008 is when he was in in prison in Texas after two years of trials. And so they were still largely run by the church. They didn’t have resources. I met a man down there that was talking about how the church was controlling who got to eat and who didn’t get to eat based on their righteousness. And so we heard some stories of some children, the little boys that had been sent away because they were swearing and I was as horrified as a mother. So we started sneaking in, we helped run an underground food bank for people in FLDS for about two years. That got a lot of attention, and so people started giving resources.

So we used to go down and do service projects where we would just fix whatever they needed fixed in town. Warren Jeffs sort of decimated the town, didn’t let them fix their homes. They were a lot of them were living in squalor and extreme poverty. And so we were able to go do some work down there. And I found out that, you know, there were advocates that had been there for a while. Sam Brower is one of them who legally is in large part responsible for helping get Warren Jeffs put in prison. Of course, it’s Elissa Wall and the other brave victims that testified that really like, get the credit for that.

But anyways, so I started doing stuff like that. One of our first things we ever did was we helped the town, the police were being run by the FLDS by the church. We did a rally against the police and everyone in town was too scared. So we brought proxy people from Salt Lake City. We let folks in the town write what they wanted on the signs and we went and held it up for them and started this effort with the community to decertify the police that allowed them to get a free and fair election. They elected a female mayor and of course there’s just been so, so much beautiful stuff. So I got to be there and witness that and walk with people who were making those changes. I felt really lucky, like to be there and to help and the role that I saw was not anything other than I was able to get resources because of my platform. So they would say, “Hey, we want to do this thing, we need money for it.” And so we would find that.

So I spent a lot of time doing that and then now there are so many good advocates on the ground that come from the community who I really think should be leading it. And so now I support them. One of them is called Cherish Families. So if you really want to support people transitioning out of those communities and getting resources, that’s a good one. It’s run by Shirlee Draper, who grew up FLDS and was a plural wife and sort of escapes and then goes to BYU and gets her social work degree. She’s amazing. So I’ve been doing that.

Also I have been invited to all kinds of different communities. The thing that I realize is that they want understanding, they really crave that understanding. And it’s tricky. It’s like you sometimes see things that just bump up against you. And because of where I come from, I think that I made some mistakes early on. First of all, I had no formal training, like I was doing work that I had no business doing. I just didn’t know enough. I was just curious and wanted to help. And I also had this Mormon like ethos of like, you can’t say no if someone asks for help. So that put me in some dangerous situations. I look back and I’m like, wow, I can’t believe that I was there and I did that because it gets confusing. I’ll give you an example. When you’re down in Short Creek, at least when I was down there, we would see 8-year-olds driving tractor, driving truck. And if I saw an 8-year-old driving tractor or truck in Salt Lake, I would be like calling highway patrol or something for everyone’s safety. You see sort of red flags, but because the real problems are so severe, you kind of ignore the red flags.

And you know, I’ve been criticized by some advocates for like being a little too soft on that kind of stuff. And at the time I was like, come on guys. Like we’ll get there. But you can’t just like shame people and change them. But I actually understand that criticism. I think it’s kind of fair because I didn’t know enough because I was still processing my own stuff to know what was really dangerous. And so I don’t think I saw the danger in some of these communities. And the danger exists. There are a lot of men in these communities that grew up with really toxic, patriarchal narratives. And so that’s my caution. Like, I want to humanize these communities, but that doesn’t always mean that they’re safe. You know what I mean?

I think that that was the overcorrection that I did early on. I was like, well, the church told me a lie about them, so they must be great. It’s just there’s so many great people, but there’s also some really traumatized people. I mean, that doctrine, that history with that doctrine has made them live underground. And when you live underground, a lot of organized crime goes with that. And so there are a lot of ancillary problems just as bad as polygamy, like human trafficking, labor trafficking, rates of sexual abuse within the communities and in our own community too are astronomically high. And so it’s tricky. Like I also think that we don’t change people by judging them. And I think that there’s a smugness, especially from people who come from our community because we were wounded by it too, Amy. That’s the thing; we we’re not polygamists, but we kind of had to live it in our hearts. Brigham Young always said, if you’re not going to be a polygamist, be one in your heart. And that’s the spirit that we were given, which is, we know it’s weird and wrong and gross, but someday it’s your heaven.

AA: Mm-hmm.

LHP: And I don’t even know how to articulate that to people who don’t know what that feels like. Even plural, wives that I meet in the modern church don’t have to deal with that.

AA: Yeah.

LHP: You’re wounded, but just in a different way, you know? And so there’s still a wound there for us. And so I think that it’s hard to not be smug about something because we feel invested in hurt in it as well. But I just really have that feminist tool in my toolkit that lets women choose. And there are women, and I have met them that were not born into this. They were not coerced into this. They actively chose that. That’s the one that I’m like, ah, does not compute, you know? Because I have a lot of compassion. Most of the people we’re talking about men and women were born and raised in this as their whole worldview. And I know what that feels like because I live that it is so suffocatingly pervasive around you that it’s not like you can just be like, this feels wrong, so I shouldn’t do it. It’s more like, this feels wrong, therefore I am wrong.

AA: Mm-hmm.

LHP: Because everybody else seems to be on board with this, and especially in these isolated communities, it’s not a choice for most of these people. So I have a lot of compassion for that, but I also have a lot of civility towards people who do choose it. The men less so. You know, I’ve met a lot of men in my lifetime who found this doctrine and have used it to abuse people. I think that that’s quite common. But I will also say it’s not fair too, to say that all polygamist men are predators. And I think that that’s the national discourse too, and that’s the one that’s tricky because when you say stuff like that, it just compounds the problems in the community. It makes the stake so high that there’s no redemptive arc.

I know some really good men who were groomed to believe that this is what being a good man looked like, and so that’s what they did. And yeah, it’s such a complicated thing and it’s hard to hold space. I think living in the world is hard. It’s traumatizing, it bruises you. We know trauma makes your brain go black and white. And I think with issues like this, we want to make it black and white. And in some theoretical plane, it is black and white, right? We know the impacts, the numbers, the data that we do have doesn’t look good for women. But that said, there’s also the reality of like, this is a generation’s old practice, at least in our community. And women have found ways to negotiate their power and to make it a feminist choice, as feminist as the sort of patriarchal confines allows it. And so it’s complex. People live complexity. They don’t live black and white. And if you truly want to understand it, you have to allow for some complexity in the story.

AA: Yeah, for sure. You’re bringing up so many really thorny philosophical issues in terms of consent, right? Can you consent? Can you make choice if you are indoctrinated your whole life or within the construct of patriarchy? Sure, you can pull some levers of power, but if the whole structure is what it is at the end of the day, I do just really…I’m really inspired by your approach, and I think it is the only way that when people feel judged, like you said, when people feel negatively judged, othered, they will not feel comfortable reaching out for help if they need it, they won’t. They’ll double down, they’ll retrench, they’ll pull back.

So, you know, maybe women who want to leave polygamy won’t because it will validate that criticism of their families, or people who want to stay and you want to help empower them to live better lives where they are if they can’t or are not ready to leave strategically. I think really the only way is through compassion and through humanizing and through education. What it really means. What that lived experience really feels like and looks like to them in their context, not as an outsider coming in with all of our judgments.

LHP: I was invited to the Cambridge Union debate and the topic was: is feminism compatible with religion? And I argued that it was, which is against the house’s position that it wasn’t compatible. And you know, I was a scandal there when they announced Mormon feminist, the room like was like, ooh, and they had to gavel the room and I was like, this feels like I’m in 1830s. But what I argued there is what I believe, which is when you make it a choice like that, like good/bad, feminist/not feminist, like you choose religion or feminism, you force some women in the most isolated areas to choose because that’s how they’re taught to see those things as a black and white choice.

And especially as liberals we get like pure in our…like it has to be perfect and this is what a feminist looks like and it has to do all these things. We can’t afford purity in activism. So I always say, do you want to be mad about polygamy? You can be. You should be. It’s horrible. It’s historically horrible, be mad, but do you want to be effective? Because those are like different roads to go down, right? Anger can drive you, but it doesn’t change other people’s minds. So I’m interested in efficacy. I do think it’s okay to also hold space for, especially people who lived it, like they get to assign it however they want. If they lived it and they hate it and they think, you know, it’s very black and white for them. Like, I support you. I can afford a little bit of flexibility on that, but we can’t afford purity. I think the thing I used in Cambridge was basically: religion is a human institution. It’s infected by the disease of patriarchy, and then here’s the medicine of feminism. And if it can encounter feminism even just a little bit, it’ll do its work. Women are not dumb in these oppressive situations and part of them knows that it sucks. Part of them knows it. It’s that loneliness that I talked about in Stansberry. They know that feeling and so when you give them a little shot of something different, then they can decide.

There are different approaches to this. People think like if you just rescue them away, like if you just take them out, you can do that. I’ve seen a lot of activists, not just in this space, but like in faith spaces too, think if they can shock you out of your face. It’s effective, it’ll get people to wake up. But it causes a lot of, in my opinion, unnecessary harm. It’s always better I think, if people choose it for themselves, because I don’t like to recapitulate the things that harmed me and to go in and colonize someone with my new idea…And there’s also this smugness that like we have it all figured out and our lives are somehow better than what they’ve got. Like there are benefits to their life. Allow these people dignity. Women are smart. They figure out ways to find joy, and even though it’s scarce, don’t assume that your way of doing things is somehow as superior as you think it is. I think that there’s a sort of hubris in that, and I’m a very Audre Lorde, like the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.

So are there sometimes cases where that works? Yes, fine. And I actually think we need to be testing out all strategies for liberation, but for me, the most effective I’ve seen, and arguably like… I’m not proud of this, but I think it’s just data. I’ve brought many, many, many people out of orthodoxy, out of their faith. I think I have a good track record, and so I think my approach is effective because if you meet people where they’re at, give them a different way to look at the world and then see where that goes, then there’s not the violence of dissociating from your entire world, which that’s a real hard, bumpy way to go, and I don’t want that on anyone either.

AA: Yeah, it can do a lot of damage. Well, Lindsay, this has been just a revelatory conversation. I am so grateful for your time, grateful for your research, and grateful for all your work. And if you can just close out by telling listeners where they can find this work on polygamy, but also all the other stuff that you’re doing, that’d be great.

LHP: Sure – yearofpolygamy.com. It’s the podcast. You can find it on Spotify as well. Year of Polygamy. I would say start at the beginning. It’s humiliating for me to think about that girl back then you can hear my little baby in my lap…

AA: It’s wonderful. You keep calling it naive and it’s not as bad as you think, Lindsay. I think it’s beautiful. And the purity of your heart and the intention that you said, I think legitimizes it, right? Because you’re not setting out with like a preconceived notion. You’re like, let’s explore this together. Sunlight is the best disinfectant. Let’s figure this out. I think it’s awesome. So I don’t think you need to do that…

LHP: I think it’s like years of trauma from my motives being questioned by just every troll on the internet. You know, you’re like, ah. But yes, Year of Polygamy, and then I have the Sunstone History podcast that you can find on any podcast app with Brian Buchanan. He’s a bigger nerd than I am about it, and I’m a big nerd about it. So we, it’s kind of more lighthearted. It’s like “our ancestors did what??Like “privy dirt, what??”, and so that’s the history in chronological order. And then, yeah, I’m doing a lot of writing and film work and that’s my biggest passion right now. And we’re making a movie and you’re involved, I don’t know what you want to say, but you’ve been a big help in that. I helped consult for Under the Banner of Heaven. I would suggest watching that so you can kind of see a reflection of my work. I said I’ve done heretical things, but that—depicting the temple—it’s something that I’m the most proud of and is probably the most heretical, but I think we did a good job there.

We have a new show coming out on January 9th called American Primeval, which I’m so nervous about because it’s complete fiction and so it’s not historically accurate. So this is the first time I got to really dabble in fiction, historical fiction. But my community is not going to like that. We want everything to be pure. I’m actually nervous about that and I’ve done countless documentaries. You can see me in Daughters of the Cult. I’m producing one for Netflix this year that won’t be out until 2026. So doing some cool stuff there. And you can also find me blogging at The Sunstone Review at sunstone.org.

AA: Awesome. Highly recommend all of those that you just listed. And again, thank you Lindsay, so much. This was just awesome.

LHP: Thank you.

the game is rigged

but we’re going to make it hard for you

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!