“we are expected to bear pain”

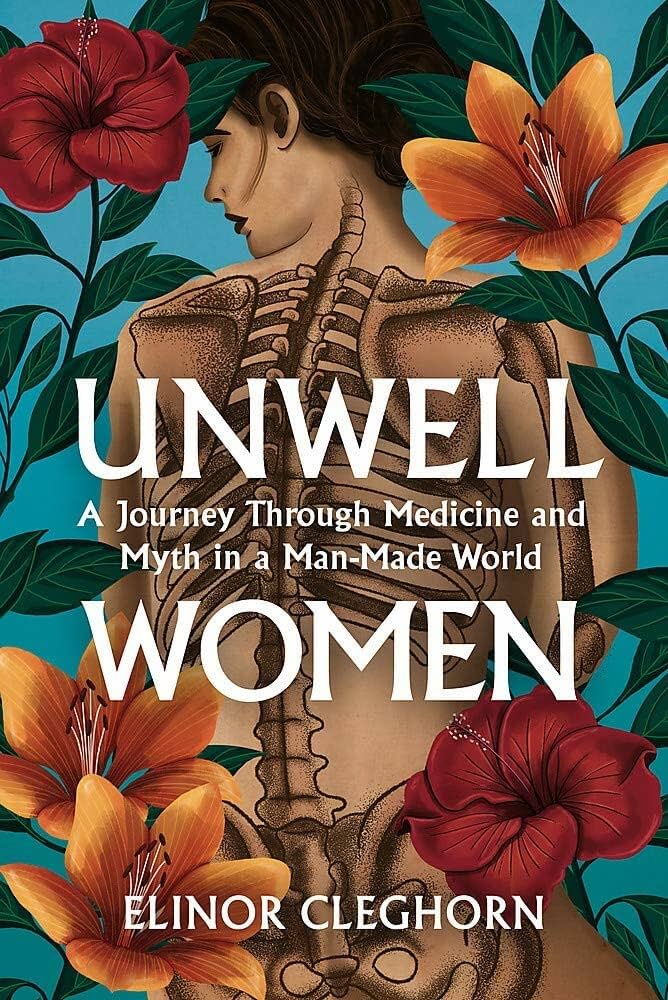

Amy returns to a book from Season One – Unwell Women – now joined by the author Dr. Elinor Cleghorn! This conversation unpacks the history of women’s healthcare, looks at medical myths and women’s pain, and explores the patriarchal shadow which still looms over our health outcomes.

Listen to the original episode about Unwell Women here.

Our Guest

Dr. Elinor Cleghorn

Dr Elinor Cleghorn has a background in feminist visual culture and history, and her critical writing has been published in several academic journals including Screen. After receiving her PhD in in 2012, Elinor spent three years as a post-doctoral researcher at the Ruskin School, University of Oxford, working on an interdisciplinary medical humanities project. She has given talks and lectures at the British Film Institute, where she has been a regular contributor to their education programme, Tate Modern, and ICA London, and she has appeared on the BBC Radio 4 discussion show The Forum. In 2017, she was shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Editions essay prize. She now works as a freelance writer and researcher. Her non-fiction debut, Unwell Women, was published in June 2021. She is currently working on her next book on intersectional feminist history of women and mother-led knowledge around reproduction, pregnancy, birth and mothering.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Every year on my birthday since about fourth grade, when my birthday cake is brought out and I blow out my candles, I have thought: “I wish for my mom to get better.” And all of these years later, that is still what I wish for every single year. My mom has dealt with chronic pain for her entire life, and there were some years as I was growing up that she would be in bed with the lights out with a violent migraine for half the week pretty much every week. According to the World Health Organization, migraines affect 20% of the world’s women and 8% of men. Sometimes my mom’s doctors have been compassionate but uninformed about her condition, and sometimes they’ve been arrogant and dismissive. Multiple times she’s been misdiagnosed for her pain. And after a fall in 2001, she received a misdiagnosis that led to permanent nerve damage in her back that has caused excruciating pain on top of her migraines. So in 2021, when I heard about a book called Unwell Women: Misdiagnosis and Myth in a Man-Made World, I knew I had to read it. I did read it, and I discussed it with a friend of mine on season one of the podcast. And it has turned out to be one of my very favorite and most highly recommended books of all the books that I’ve read for Breaking Down Patriarchy. Today I am so honored to welcome to the podcast, Dr. Elinor Cleghorn, the author of Unwell Women. Welcome, Elinor!

Elinor Cleghorn: Thank you so much for having me, Amy. It’s such a pleasure to be here.

AA: It is such a pleasure to have you. And I was just saying to Elinor, and I’ll repeat it here, I read a lot, a lot, lot, lot of books, especially in women’s studies, and some of the books I read are very dense and academic and I’ve learned a ton from them and they’re very, very useful. But I can’t really easily recommend them to people because they’re hard to get through, it’s difficult language and jargony sometimes, or they require some kind of niche amount of knowledge in a particular field. And I so appreciate when I get a book that is well researched, really, really smart and scholarly, but really accessible and enjoyable to read, and this is one of those books. So, thank you! Thank you for doing such high quality research, but also making it much more readable so that so many more people can benefit from it. I so appreciate this book.

EC: Well, thank you so much. That’s really the highest praise. And as we were talking about before we began recording, it was really, really important to me that this book was accessible to anybody with an interest in the topic. Anybody who had a personal connection, as you do, and I’m so sorry for what your mother has been through. Anybody with a personal connection to illness, anybody who identified as an unwell woman who knew or loved an unwell woman, or who themselves had been through difficult experience with negotiating their health needs within the medical establishment. This accessibility was very, very important to me. So I’m really thrilled to hear that. Thank you.

AA: Yes, yes. Thank you. And listeners, I’ll just repeat again, if you haven’t bought this book and read it, really do buy it and read it. And this is such a good one to give. I hear all the time like, “What’s a book that I could give to my dad? What’s a book that I could give to my husband that he would be interested in reading?” This is one of them.

Dr. Elinor Cleghorn is a feminist cultural historian. After receiving her PhD in 2012, Elinor spent three years as a postdoctoral researcher at the Ruskin School at the University of Oxford, working on an interdisciplinary medical humanities project. She now works as a writer and researcher and lives in Sussex. She is the author of the book Unwell Women: Misdiagnosis and Myth in a Man-Made World. And we’ll focus our conversation mostly on that book, but we’ll also branch out from there. Now if you could introduce us to you a little bit more personally and tell us where you’re from, some of the factors that made you who you are today and what brought you to become a feminist cultural historian, and then to write this book.

EC: Sure. So, I have a background in feminist cultural history. I did my PhD in Historical and Cultural studies at the University of London, and my focus was really on women’s contributions to early cinema. And it was a very specific field, but my background is in art history. After I did my PhD, I pursued an academic career for a few years, but it was exceptionally difficult because the university as a system in the UK is in a lot of crisis and it was very, very hard to get my foot into an academic career. And then I was lucky enough to get this position at the Ruskin School of Art at the University of Oxford, which was this interdisciplinary project looking at a neurological condition called mirror-touch synesthesia. Its relevances and resonances with art, with film, with other forms of media. So that experience really enabled me to pivot a bit from this straight art history, feminist art history, into the discipline that we call the medical humanities. So my interest in medicine, but more specifically in the lived experience of people with illness, really germinated during that experience. Those are the professional roots of how I got to write the book.

There’s also a really personal story in that I am myself an unwell woman. I have an autoimmune disease called lupus, that was diagnosed after my second son was born. I had a really difficult pregnancy. My son had a very slow heart rate while in utero, and this is a rare condition. One of the only causes is the antibodies part of the immune system that causes this disease called lupus. So my diagnosis came as a shock, but it also came as a vindication because for years I’d experienced chronic pain and many other symptoms, both physiological and mental. And every time I’d gone to the doctors to try and get some answers about what was happening in my body, I was not only dismissed, but dismissed with some sort of excuse that my pain and other symptoms were the fault of my femaleness. So I either got told that I was anxious, I was worrying too much about my body, that I was paying too much attention to myself. One doctor accused me of being pregnant, not accused me, but you know, said I must be pregnant and not realize. And after a while I just thought, “Okay, I am making this up. This is in my head.” So the diagnosis was a real vindication for this. Being a historian, my impulse was to look backwards to understand what was happening in the present. And that involved a combination of looking back into my own history of my body, my illness, my encounters with doctors and other health professionals, but also looking back into medicine’s history to find women like me who’d been through experiences like this. Some of the first case studies I found of young women with lupus from the 19th century, although worlds away in terms of the language and clinical explanations when it came to the dismissal, the misdiagnosis, the overlooking of women’s pain, it was so very present. And it occurred to me, why has medical science advanced exponentially over a century, yet these basic attitudes towards women’s pain and towards the validity and legitimacy of women’s pain are still with us? That was really what inspired me to expand this little bit of personally imposed investigation into the research that became Unwell Women.

AA: I feel like those are often the most powerful works of scholarship, when someone like you is academically trained and then also has an engine driving them in a particular area that is personal and it’s based in lived experience. Both of those things combine and come through really strongly in the book. Thank you so much for sharing that, and thank you for sharing those incredibly frustrating experiences too. I think it’s unfortunately so relatable for a lot of women. Well, I’d love to jump into the book itself and dig in on a few different topics that you write about. In your introduction you write: “Medicine has inherited a gender problem. Medical myths about gender roles and behaviors constructed as facts before medicine became an evidence-based science have resonated perniciously, and these myths about female bodies and illnesses have enormous cultural sticking power. Today, gender myths are ingrained as biases that negatively impact the care, treatment, and diagnosis of all people who identify as women.” Let’s start out with some of these gender-based myths. What are these myths about gender roles and behaviors? Where did they come from and how do they continue to show up today?

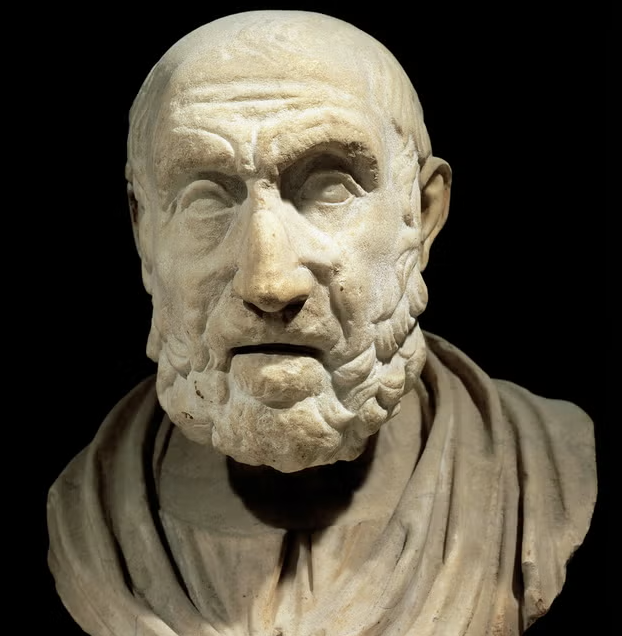

EC: In Unwell Women, I begin my history in ancient Greece. Specifically in Classical Greece, which for the western world set the seat and the beginnings of learning and knowledge. And medicine, of course, was no exception. During the fourth and fifth centuries BCE, there was a legendary physician by the name of Hippocrates, which many people would’ve heard of because his name is associated with the oath that medical practitioners used to take a form of, which is the sort of basic premise of ethical medicine. Hippocrates was, we think, a physician who taught many other physicians. And those physicians produced over the fourth and fifth centuries a body of work that’s known collectively today as the Hippocratic Corpus. This was made up of different tracks authored by different physicians about illnesses, diseases, body parts, body types, and a great number of these tracks were dedicated to the health and diseases of women.

Now, Classical Greece as this center and seat of learning and knowledge was also notoriously patriarchal. It was a society in which the social and biological difference between men and women was very ingrained. So when these doctors, these physicians, were writing about the female body, a lot of the way that they understood how the female body worked and how it needed to be treated when it was unwell, when it was dysfunctioning, was based on social understanding. These physicians weren’t performing autopsies on people, they didn’t have MRI machines, they were not able to look beneath the skin, so they were making certain assumptions based on what they could see and feel, but also based on what they knew to be true about the difference between men and women. And in a society where men are assumed to be dominant, superior, and authoritative and women assumed to be secondary subjects whose main purpose of existence is to bear children for men, to bear and raise the heirs of men, it makes sense to that society and to those physicians that the female body, the bodies that bear those children for men, would be understood as primarily reproductive.

So the understanding of the female body that comes from ancient Greece, which is full of some really fantastical ideas like the wandering womb, whereby if a woman’s uterus was not performing its social function, gestating a child, it was believed that it would become shriveled and dry and start creeping around the body in search of moisture. I mean, these are ideas that sound completely ridiculous, somewhere between a fairy story and a horror film. But it really made sense for these physicians as a way of figuring out how on earth the female body could attain an equilibrium of health. This is a body that bleeds every month. This is a body that grows, bears a child, and kind of shrinks back again. A body that goes through the most incredible, and to them inexplicable changes and transitions. But it’s also the body of the person who’s socially inferior, who exists for a particular male-serving purpose. So when this discourse was created, it was kind of imbued with prejudices, ideas, assumptions, biases that women’s bodies were naturally inferior, primarily reproductive, that all their health needs pivoted around this reproductive system, this organ, this unruly womb, and that because women menstruated and became pregnant and gave birth, that these processes must be integral to their health equilibrium. So the Hippocratic Corpus is positing, and this is a really authoritative document or set of documents, that what women are told they must do societally, which is marry young, have marital sex, bear children, is also what they need to do for the good of their own health. This is the fundamental concept that I think has echoed through the centuries, that the female body is primarily reproductive above anything else, so her value, her worth, and also her needs as a human all center around reproductive function.

AA: Yeah. You even share examples in this section that were so interesting to me that if something did go wrong, like if a teenage girl was experiencing a health problem, that sometimes the prescription would be like, “She’s getting too old. Get her married, get her having sex, put a baby in that girl, get her pregnant, and that would cure her,” right?

EC: Absolutely. Because they sort of understood the female body as a kind of system, so too much menstruation without the break of being pregnant was the kind of pathology. So there is this incredible, the tale that you are referencing there, is an incredible example from the Hippocratic Corpus, which talks about the diseases of virgins or the diseases of young girls. And it describes a teenage girl of about 14 who is having what we might describe as a form of psychosis or a breakdown, a sort of hysterical episode where she’s filled with melancholy and the desire to even end her life. And the diagnosis essentially is the sort of suffocation of menstrual blood, like having too much menstrual blood in one’s body drives the emotion, like too full of blood and the emotions are driven bananas and the womb as well, of course. So the cure is marital sex. Marry, have sex, procreate and give birth, because that is the process for which she exists and this is where the sort of loss of stability and her loss of her emotional state comes from. It’s always so fascinating to me, and also terrifying, that if this case was in fact based on real cases that the physicians at that time were seeing, imagine how fearful it would’ve been to be a young woman and to know that you would be married off at 13 or 14.

when this discourse was created, it was kind of imbued with prejudices, ideas, assumptions, biases that women’s bodies were naturally inferior, primarily reproductive, that all their health needs pivoted around this reproductive system

AA: Yeah. Even that itself might be enough to make a girl anxious and depressed and give her those symptoms in the first place, right?

EC: Especially because girls in this society, at least societally privileged girls who would be put into marriages in this way, were marrying men that they barely knew, were often complete strangers chosen for them by their fathers who could have been at least 30. You’re talking about marrying a man twice your age that you’ve never met. I mean, it happens. Child marriage is not something, sadly, that we have left in history.

AA: Yeah, true.

EC: But to read this description of this harrowing emotional experience in a young woman and to think that it was seen as a health pathology from delaying her basic female function is such an incredible insight, I think, into exactly this insistence from male doctors on, “Well, what must be wrong with you is all going on in the womb.” It can have nothing to do with societal factors, nothing to do with anything other than this kind of monstrous organ that you are kind of condemned to deal with.

AA: Yes. And for listeners who don’t know, I remember being in Latin class in high school and learning that the root of the word “hysteria” comes from– is it the word for uterus? And that’s why it’s called a hysterectomy, when you have the removal of the uterus.

EC: Yeah, “hystera” is one of the ancient Greek words for uterus, so it was precisely from that word that in the early modern period the word for hysteria and then from that hysterectomy was derived.

AA: Yes. It’s very telling. Maybe we can move forward a little bit historically and talk about the next step in the chronology that reinforced patriarchal control over medicine.

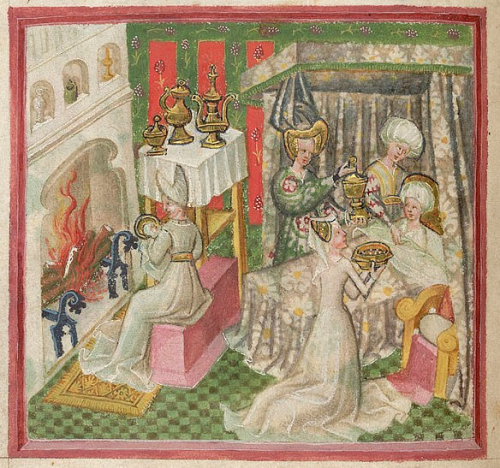

EC: Tracts like the Hippocratic Corpus, those were not the only ones that survived the sort of fall of the Classical world, but they remained some of the ones that did survive and were translated and were transmitted across the centuries. And as we have works like the Hippocratic Corpus being translated into Latin and then later into the vernacular, they’re of course translated not just in terms of what is there textually, but in terms of the new concerns as history has moved on about women and their bodies. And of course the basic premise that women were primarily reproductive didn’t dissipate as we moved out of the antiquity and into the Middle Ages. It was very much still there, but what we now had was the addition of another potent set of myths about men and women, which was Christianity. And a Christian religion and the biblical myths that defined the creation, especially of men and women, which we will know to be the famous myth of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Very specifically I think, one of the key myths that we have here, if we were to say the wandering womb myth really typifies medical attitudes towards women’s bodies during the antiquity, I think the story that really shapes them during medieval Christianity is that of Eve being created from one of Adam’s ribs, from a spare bit of a man.

So Eve, the first woman– well, not quite the first woman, the second woman, is created from a spare bit of man’s flesh. She’s not made from the earth, she’s not made in God’s image, she exists to be appendage to men. And because she wants to eat from the Tree of Knowledge because she desires independent intellectual existence, she and every other woman after her is punished by God with sorrow in childbearing and to be joined to men and be their helpmeets. And just as these ideas about the wandering room were assumed to be facts, so were these biblical stories assumed to be facts during medieval Christianity. And what we see in those early centuries, say around the 12th and 13th centuries, is that existing medical knowledge about bodies, about humors, about bleeding, is then infused with these new myths. There was a really potent and extremely popular little book called The Secrets of Women, which was written around the 13th century, and it’s easily the most misogynistic– it’s so misogynistic that it’s almost funny to read by today’s eyes. It is so ridiculous and so hateful that you can kind of read it as a parody, but unfortunately it wasn’t parodic for the time and it was a real example of how misogynistic church men, who were the people who housed medical knowledge, how their attitudes towards women being these deviant, dysfunctional, devilish creatures affected the way that understanding of their bodies and health needs developed. So in medieval Christianity, we see a lot of talking about wombs as sewers and menstruation as making women inherently deviant and women having this sort of irrepressible, insatiable appetite for sex that men just don’t have. And this is all informed by the fundamental gender stories that come through from the Bible myths of Christianity.

AA: Isn’t that weird, too? I remember when I learned that, just as an aside, that there was a time when women were thought of being kind of the sex fiends and the ones with the crazy libido who would be, the temptresses. They were devilish in their influence on getting men to think impure thoughts and do impure things. I thought that was so interesting.

EC: It’s especially interesting because the basis of that idea was that women lacked the reason and ration and self-control of men. And again and again in medieval Christianity we see these stories about how women always enjoy sex and enjoying sex is absolutely integral to getting pregnant. And in more recent years, this is a myth that’s evoked often against reproductive rights, often against abortion rights, which is that if a woman has got pregnant then she must have consented to a sexual encounter. So this idea about this voluminous, unwavering sexuality in women, again, it’s something that’s resonated really perniciously, not just medically, but legally.

AA: Yes. And I didn’t realize that anyone had believed that in the last few hundred years until there was a US Senator, I’m sure you heard about it, in the last couple of years that said something like that about rape victims. That getting pregnant meant that you consented to it and that you enjoyed it. It’s unbelievable how these things are still part of our consciousness.

EC: Completely. When you see a piece of writing from the 13th century talking about the reason that sex workers don’t get pregnant often is because they take no enjoyment in their work, it has nothing to do with the fact that they may know how to limit their fertility. It’s because they don’t enjoy what they do. And from this ridiculous and completely, utterly prejudiced and sort of crazy notion which denies women any agency around their bodies, we have something that, again, has this sticking power and really appeals to certain men in the present who would orchestrate to remove rights and reproductive care from people.

AA: Yeah. One other question I have about this period of time is that you mentioned before that people weren’t dissecting bodies for a long, long time, so they didn’t really understand anatomy, right? They didn’t understand the female body, not even the parts, let alone the function. But I’m wondering, as we move forward, who were actually practicing doctors? Were there any women doctors who were able to practice, and what did they know and what didn’t they know about women’s bodies? And we’re focusing mainly on Europe in the medieval period and moving into the Renaissance time period.

EC: What’s interesting is that women physicians do come up and women physicians come to us through the historical record. And of course during the antiquity, and in fact for all of human time, a lot of women’s healthcare has been in the hands of other women, of midwives, of women with healing knowledge, of their peers, relatives, and friends. Lots of what we’re talking about with everyday medical care, the birth of babies, caring for each other, caring for bodies, so much of that was done by women throughout history. But what comes to us and has survived down the centuries is sanctioned knowledge. And the problem isn’t that women didn’t practice medicine, it is that women were not allowed to study it and write about medicine. So even though a few figures do come to us through the archives, especially some really incredible midwives and birth caregivers, we know that what we end up knowing and what ends up being taken as canon are these very authoritative texts authored by men who were part of this genealogy beginning with Hippocrates coming up through the monasteries and libraries of medieval Europe, moving into the schools of anatomy in Italy during the Renaissance. This is the legacy. It’s one that represents the fact that it’s men who’ve been allowed to write, men who’ve been allowed to study.

So when we look at the midwives’ texts that come out from earlier in the Roman imperial period, for example, there was this brilliant, very insightful text written by a gynecologist called Soranus, and he wrote a lot about midwives’ practices. And from that you can really see the expertise and the extent of the medical knowledge that midwives held, but it’s not authored by a midwife, it’s authored by a man. So we have to quite often read these sources to look for the invisible women, to look for the hidden women or the hidden sources of women’s knowledge. And those women were not dissecting bodies either, but of course they have a certain amount of experiential knowledge that comes from existing in their own bodies. And medical expertise is by no means essentialist. So I’m not saying that only women who experienced birth themselves could be midwives, but there was a certain empathy, a certain kind of bodily empathy, and also the ability to share and to speak about one’s body, which was always something that sort of interrupted the medical encounter throughout history. And that’s the sort of propriety between men and women. The fact that women were not supposed to talk about their bodies, they were not supposed to reveal their bodies.

So it’s always this loss, you think about this sort of lost channel of history sitting underneath the major one that has survived and that we have followed as medical canon. And quite often that takes on, and I think sometimes not so usefully, a very mystical air, like it becomes witchy or sorceress-ly rather than what it really was, which is hard-won expertise gleaned over generations of women through practice and study and learning and understanding the natural world and understanding one’s body. And that probably brings us quite nicely onto witch trials, actually. I know we didn’t speak about them, but in the end of the Middle Ages and into the early modern period, we know that there was this horrifying epidemic of witch trials across Western Europe where some 45,000 people were tried and executed as witches, and about 80% of those, we think, were women. And there’s often a sort of myth associated with this, that one of the motivations for the witch trials was the need to stamp out women’s medical knowledge, because it also coincided with a time when medicine was becoming much more professionalized. I think that this is sometimes overblown, but it doesn’t stop this period of time from being an excruciatingly difficult period of our history, and also one that in some instances did target women who were medical practitioners, healers, and birth caregivers. There was a rank misogyny that was informed by the things we’ve just been talking about, around women’s sexuality, around women’s inherent deviancy, that also married with this fear of women’s bodies and women’s bodily knowledge.

what comes to us and has survived down the centuries is sanctioned knowledge

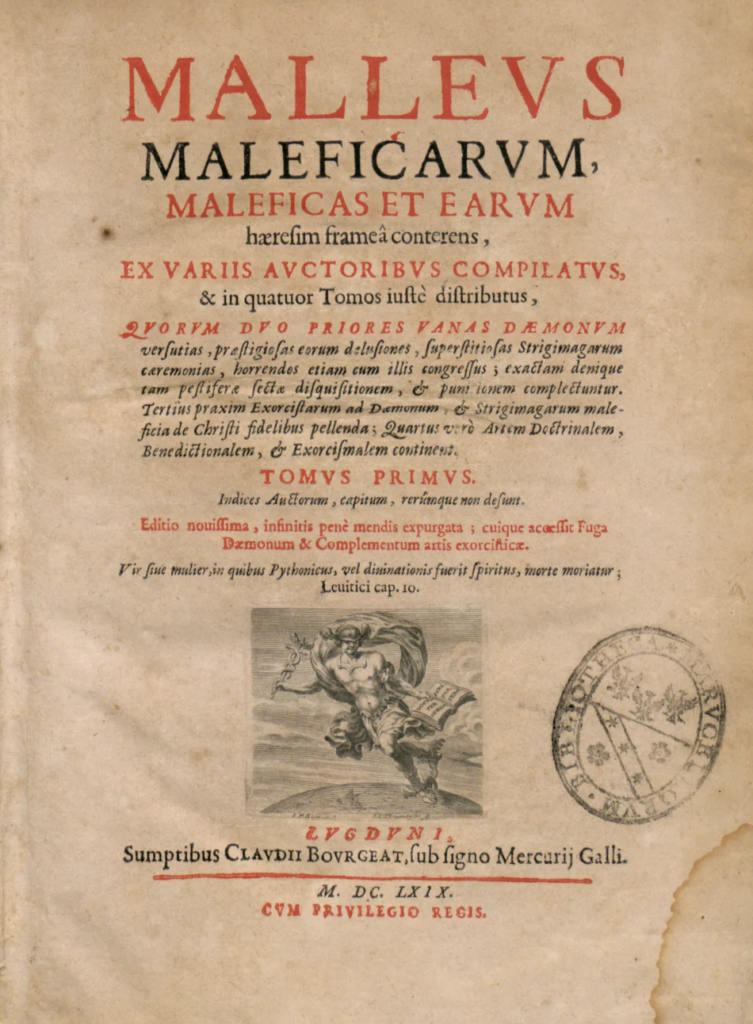

AA: Can you talk about some of the big actors, the perpetrators that were publishing about women and kind of started this movement to really vilify midwives and call them witches and then started these witch hunts? The one that I remember from the book is Heinrich Kramer.

EC: Mm-hmm. He was particularly disturbing to me. Kramer was a German monk who was also an inquisitor, so he was someone in the Catholic Church who had authority from the pope in the Middle Ages to prosecute and persecute people that he suspected of being enemies of the Catholic faith of being heretics. And witches were a great obsession of Kramer’s, more specifically women who may be practicing witchcraft were an obsession of Kramer’s. And he wrote this absolutely horrifying book called the Malleus Maleficarum, The Hammer of Witches, which explained in just exhausting detail how to identify, persecute, punish, and torture mainly women for suspected acts of witchcraft. And Kramer was certain that witches existed, that they had sex with the devil in the form of an incubus, and that they then did his awful bidding on earth. And one of the professions that Kramer hated above all others, and felt that witches were most endemic in, was midwifery. He believed that midwives, when they became witches, were capable of killing babies with a glance, of performing abortions with a mere touch, that they were stealing babies and dedicating them to the devil, that they were killing their own children. I mean, it’s really horrific stuff. It’s really awful. He was really convinced of this.

But what’s fascinating again is that when we talk about these myths, the image of this crone-like midwife witch that Kramer was conjuring up in that book was almost verbatim drawn from old Roman folklore and fairytales about these hideous female creatures who would devour infants in the womb. So he was not reinventing the wheel here, he was merely adding a new panic spin onto old myths about midwives’ terrible intentions and getting up to awful things behind closed doors in birthing spaces. And I think the root of this anxiety, one of the major roots of this anxiety, is that midwives represented a sphere of women’s activity that men were not privy to. For many centuries, it wasn’t proper for men to be in birthing spaces. Births were really social events that often were accompanied by rituals, were accompanied by women talking to each other, with gift-giving, with reading, with doing rituals with amulets, and reading from parchment. And it’s an incredibly rich culture but it’s a women’s culture. And the people in that room represented some of the most prized possessions of men: their wives. So I think it’s really natural that men who were misogynist, men who hated women and feared their knowledge and feared their power, would denigrate that profession.

AA: It’s striking me anew as you’re saying that that probably since the dawn of time, people– and I still feel that way, it’s miraculous, it’s almost too magical to really believe anytime that you witness the birth of your own baby or a baby that you love. It’s the most powerful thing there is to witness new life, and that that would happen in a space that men had no control over must have really caused them a lot of anxiety. And like you said, if they have a proclivity toward misogyny or they’ve been influenced by those Roman pamphlets, it’s just going to make it go wild. One thing that I took away from this section too that really struck me is how brave those midwives would’ve been, particularly in an environment like that, where if they had a stillbirth they could be blamed and accused of witchcraft. It would really make you take seriously and have to think about whether you’re willing to go into that line of work because it’s dangerous for you. Because that happened all the time. Mothers would die, babies would die, and you could be blamed for it. It’s absolutely appalling.

EC: Yeah, that’s something that is really shocking. There was this bull from the pope that gave people like Kramer this unhindered authority to prosecute people suspected of performing witchcraft. And within this papal bull from I think the 15th century, is a list of crimes, I guess, or things that witches were assumed to be capable of, which included causing male sterility, causing abortions, impeding fertility. So the idea that there were these women who would come along and were intent on disrupting the male control, the patriarchal reproductive order, you know, it was too much. It was far too threatening. And yeah, you do think, how could anyone want to undertake this work? Because for things so commonplace, the death of an infant, tragically common, a stillbirth, the death of a mother while giving birth, these are tragically common events, and any woman in proximity to them could be potentially accused of witchcraft. It was in an incredibly dangerous profession and an incredibly courageous one too, to be literally guardians of life.

AA: Mm-hmm. And how can you defend yourself, right? There’s no way you can prove that you didn’t. It’s an absurd accusation and you have no defense, and then you’re up against, like you said, the Catholic Church. You have the institutional might on one side, and if they choose to come at you, there’s just nothing you can do. Incredibly courageous, those women.

EC: When you have these myths, as well, about women being inherently deviant and lying and capable of falsehoods, yeah, it was a really a monstrous, monstrous bit of history, really.

AA: Yeah. Well, thank you for writing about it and talking about it. I thought that was a fascinating section of the book, as they all are. Okay, switching gears. One thing that I was also very interested in, I’ve had several people close to me suffer from endometriosis in my life, and you write that the way that the medical establishment has handled endometriosis is “an object lesson in male-dominated medicine’s historic failures.” Can you talk about that?

EC: Yeah. Endometriosis, as we understand it now, is a chronic inflammatory disease that causes tissue that is similar but not the same as endometrial tissue to grow in other places in the body. It has been something that you can spot being documented through medicine’s history since its very beginnings, but it wasn’t named and studied in a conducive way until the 1920s when a chap called Joe Vincent Meigs did studies on women who had some of the characteristic symptoms today that we associate with endometriosis, principally pain and excessively heavy menstrual bleeding. And he surmised that this was a disease that A) primarily affected privileged white women because of the women that he was studying, and B) that it was caused by women prolonging or postponing marriage and childbearing in favor of going to work and thinking and doing something other than procreating with their lives and bodies. He used the example that monkeys don’t wait to procreate, they just get on with it, and he claimed that it wasn’t natural to keep menstruating. He thought that women needed the cessation of pregnancy in order to be healthy. So essentially what Meigs was saying was that it was women’s own fault for not towing the domestic line and doing their principal social and biological duty.

And this is a really good example of what I said at the top of our recording about how these fictions resonate and they replicate and instead of being challenged and debunked, new learning gets layered upon old. And today we know that endometriosis, for many, many decades, has been thought of as a disease that only affects white women. In the mid-20th century it was referred to as a “career woman’s disease.” And the hypothesis of continuous menstruation being the cause of endometriosis has also led to the myth that getting pregnant will cure it, which is absolutely not true. I know that some people who have endometriosis have experienced a lessening of their symptoms if they were able to get pregnant, but we also know that endometriosis can make becoming pregnant really difficult. So what we have now is a disease that affects a startling number of people with a uterus but that is still incurable, frequently misunderstood, very often not properly explained, and we know that it’s one of the leading diseases where diagnosis is postponed for too long because its symptoms – pain, heavy menstrual bleeding, et cetera – are among those symptoms that are so often associated with diseases that are apparently in women’s heads rather than being in their bodies. I think that endometriosis is that object lesson. It’s social stigma, prejudice about who gets ill and why, ideas about what women’s bodies are for. And even with advances in medical science, these myths have stuck with us.

AA: Yeah. It strikes me hearing you describe it now, we’ve inherited it almost unchanged from ancient Greece. It’s the exact same language, it’s the exact same diagnosis and prescription, and it’s insane to me that so little has changed in literally thousands of years. And one big theme in the book, and I know sadly from your own experience, Elinor, is women not being believed when they say that they’re in terrible pain. And maybe just men being used to women’s pain, I don’t know if that’s also inherited culturally from the biblical passage that says “in pain you’ll bring forth children” and so we all have this expectation that women will be in pain all the time and we’re okay with it or maybe that they’re making too big a deal of it. But this is a huge problem that doctors don’t take women’s pain seriously.

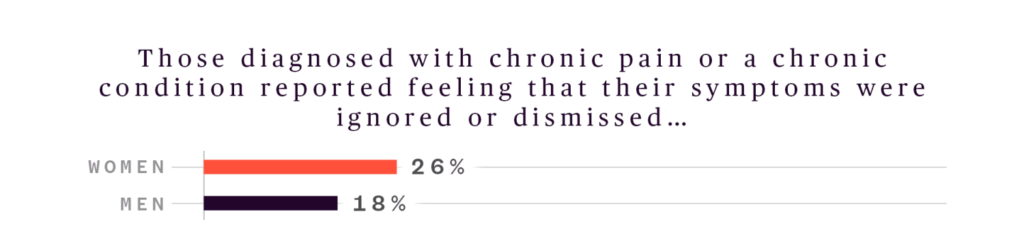

EC: Absolutely. And I think you’re right that it is something we’ve inherited wholesale from as long ago as ancient Greece. It’s something that I have read constantly across the centuries, that the basic condition of the existence of a woman is one of pain and that because we are primarily reproductive, because we’re menstruate, because that is our purpose, we have to bear that pain. We don’t just exist to be in pain, we exist to bear that pain. And it’s something that was articulated in ancient Greece when the female body was pathologized as a pain-feeling body, as a body that is plagued by pain because of its reproductive state, is something that also is then further entrenched, as you say, from the biblical myth that women are condemned through their own folly, their own deviance, to be in pain. And then it’s something that again is reiterated through the emerging scientific study of a disease like endometriosis. So this idea that we are expected to bear pain has stained the understanding of women throughout medicine’s history. And today we know that this bias is still so, so present. When a woman reports to an emergency room and says she is in pain, she’s statistically less likely than a man to be given further diagnostic tests, to be offered painkiller medication, to be offered opioid-based pain relief. She’s far more likely to be dismissed because it’s just perceived as the condition of her being.

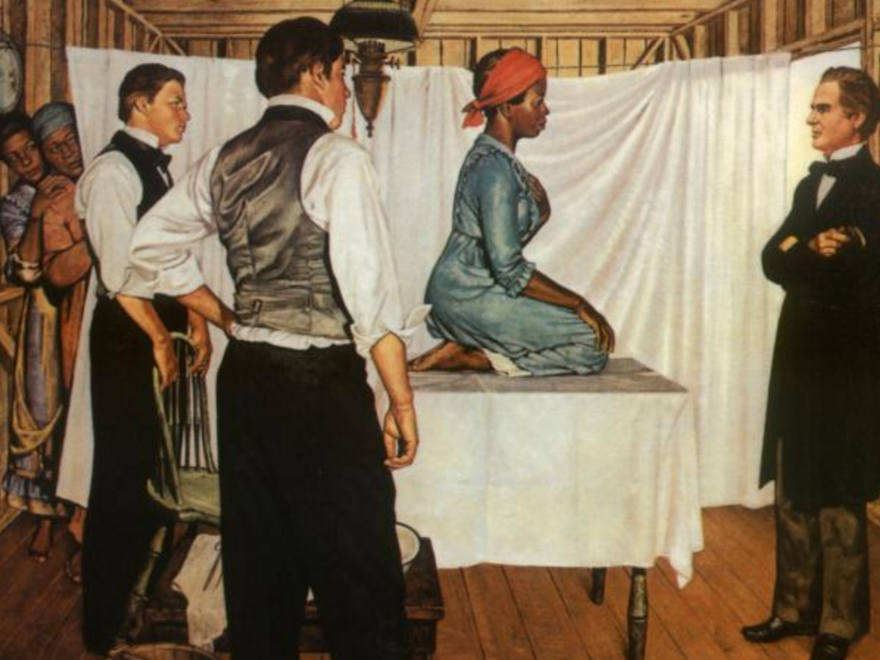

AA: Mm-hmm. This leads to the next topic that I wanted to ask you about Elinor, because we now are going to add a layer on top of that, that misogynistic expectation that women will bear pain, when we add a racist layer to that. We’ve seen some just horrific, terrible medical practice regarding women of color, and you write about this extensively. I’m wondering if you could talk about racism in the medical field and specifically about a man named Dr. Sims in the United States.

When a woman reports to an emergency room and says she is in pain, she’s statistically less likely than a man to be given further diagnostic tests, to be offered painkiller medication…

EC: So, Dr. James Marion Sims was an American doctor in the early-mid 19th century who for a long time was regarded as the father of American gynecology, so he was a pioneering gynecologist. And he had a practice in Montgomery, Alabama, where I think two thirds of the population were enslaved people. He would treat enslaved people working on the plantations in Montgomery, and oftentimes the enslaved people who needed medical attention were women who’d been forced to bear children for slave owners and been forced to bear children with other slaves for the purpose of increasing the yield of slaves. I mean, it is just horrifying. But sometimes Sims would purchase female slaves from their owners and use them as clinical specimens upon which to experiment and practice his gynecological surgeries. He perfected, in his words, a surgical procedure for a vesicovaginal fistula by experimenting on young enslaved women. I think there were about 11 young enslaved women, and there’s a posthumous biography of Sims where he talks about some of these procedures that is one of the most harrowing things I’ve ever read. Not just for the content, but for the fact that Sims is utterly disregarding of the humanity of these people and that he’s also vaingloriously convinced by the just nature of his mission. He’s convinced that he’s made a surgical procedure that can cure an otherwise incurable condition in white women by abusing the bodies of enslaved women who have no choice about what happened to them.

There is no justification for what he did, but the way he justified it to himself was through these beliefs at the time which came through anthropological colonialism, that people who were not white felt and experienced pain differently. That there was a sliding civility scale of pain where white people, because they were apparently refined and delicate, experienced the most amount of pain, and then Black people experienced the least amount of pain. We know now that these ideas, which are collectively called scientific racism, were put forward as apologies for the abuses of chattel slavery. So if you create a system of knowledge which says that certain kinds of people are less than human, then it justifies the treatment of them as less than human. And scientific racism, although now, of course, thoroughly debunked, we see its resonances today in the fact that Black women are far more likely to die of pregnancy and maternal health related causes than white women are. We know that where a white woman might be accused of being, say, hysterical or overly anxious in a doctor’s office, that a Black woman has to fight that much harder to have her pain recognized at all. And in terms of the biases, we know that it’s really important not just to talk about gender, but to talk about all the intersections and the double indignity of misogyny and racism that Black women continue to suffer today. It’s something that reaches into every aspect of a person’s life experience, right? Because it’s not just that conditions tend to be more overlooked in Black women such as endometriosis and certain kinds of heart disease, but also things like postpartum depression is something that is not as frequently diagnosed in Black women because there is this assumption that they’re not allowed to have the emotions that white women might have after giving birth.

And the absolutely tragic and harrowing shadow behind that is that throughout the centuries of chattel slavery, enslaved women were not treated as mothers, as human people, but as reproductive raw material. That section about Sims was the most difficult to write in the book. There used to be a statue of Sims that stood at the top end of Central Park and campaigners had for years wanted that statue to be taken down and it finally was a few years ago. I think that much more knowledge and awareness has been arising now, that we have to think about who enabled these advances in medical science to happen. Because for every advance in medical science, there is a human body, there’s a real person suffering beneath it. And what’s been really incredible to see is that Lucy, Betsey, Anarcha, and some of the enslaved women whose Sims experimented on, their stories are being told and they are being hailed as the mothers of gynecology. And I think that is how we do history. That is how we look again at who created this knowledge and we tell those stories. That is a real way to rescue these women to our history. Not just to focus on their pain and their victimhood, of course they were victims, but also on the fact that they are the makers of history and that in the present we can honor them and go some way to give them the humanity and dignity that they were not allowed in life.

AA: Yes. I have to tell you, I was in Montgomery, Alabama just a few years ago and we were seeing all of the civil rights history sites. I was with a group at Stanford and I didn’t know where we were going next, and we got off the bus and walked up and there were these giant, completely arresting statues made of all kinds of scrap metal from all different things and they were so beautiful and I just gasped. I had read your book maybe a year and a half prior and I knew immediately who they were. They were these beautiful sculptures of these Black women, I don’t know if you’ve seen them in person or have seen pictures of them–

EC: I would love to see them in person, I’ve just seen pictures, but yeah, they’re absolutely extraordinary.

AA: They are. And again, I didn’t even know that that’s what we were going to see, my head was in another spot, I was thinking about other things in the civil rights movement. We walked up and I gasped and got chills from head to toe, and I thought, that’s Lucy and Anarcha and Betsy, I knew it. The artist was there and took us around, so it was just beautiful. And we’ll have pictures of these sculptures on the website. But to your point, there’s a big movement and I know she was working to have especially those three women’s names known more, and especially to establish some other landmarks in Montgomery to bring that gynecological history to light. It was really amazing. But I was so happy that I knew about them because of your book! So, thank you so much for writing about it and bringing that important topic to light. I can only imagine how difficult it would’ve been to read those primary sources and have to do that, but I’m so glad you did. One last thing that I want to ask you about, Elinor, is that I understand you have a new book coming out in 2026, and it’s about motherhood, so I cannot wait to read it. Honestly, you could write about anything and I would read it, but I’m just thrilled to hear it’s about motherhood. If I’m allowed a sneak peek, I’d love to know a little bit about your next project.

EC: Thank you so much for asking me about it. It’s been a long time coming. I think that with one’s first book, it’s often something you’ve been sort of living with and it’s been germinating for years and years. The second book after that can be quite an undertaking, but it’s been a complete privilege to write about a huge topic of motherhood. It’s a book that focuses on maternal bodies, maternal mothering lives, and also mother’s rights. Again, following quite a similar historical trajectory. This one begins in the ninth century BCE and goes up to the present.

AA: Wow.

EC: What really fascinated me when writing Unwell Women was this idea that women are primarily reproductive, so I almost wanted to flip the story around and go, well, but what has that meant? What has that actually meant for women’s lives? And it’s been fantastic because this time around the men are really shelved and I focused as much as I can on the writings, lives, activism of women and people who mothered. Yeah, I’m really excited for it to come out. Got a little while yet, but it will be out in the spring of 2026.

AA: Oh, I can’t wait. I’ll definitely pre-order that and maybe if you’re able, we’d love to have you back on to talk about it once it comes out.

EC: That would be a total pleasure, I would love to.

AA: We’re getting to the end of the conversation, and I’m so sad about it. It has been so delightful to talk with you, but we’ll end with a couple of takeaways, maybe one from me and one from you. One of the passages that I have carried with me is where you write: “Speaking out about your own body is profoundly feminist. It is generous and courageous to revisit and recall the trauma of pain and a radical gesture in a culture skewed towards doubting and disbelieving women. It’s a risk, but at the same time, it’s an act of defiance against those power structures in the man-made world that would prefer us not to speak.” I was really moved earlier in our conversation when you talked about, I think it was in the context of the Middle Ages and how because of codes of modesty and propriety, women wouldn’t have felt comfortable sharing things about their bodies with male doctors. And only men were allowed to be doctors, so there’s this gap in knowledge because women couldn’t share what they were actually experiencing with male doctors. And I think that has persisted into today. I can even say that I feel that a little bit. There’s still this shamefulness in women’s bodies, women’s symptoms, especially our reproductive health. It’s really hard to speak out about our bodies because of shame, and especially if there’s religious shame, but also just not being believed, like you said. So it is a risk and it does require courage. I have remembered that sentence word for word, “speaking about your own body is profoundly feminist.” So that’s my takeaway that I would love to leave with listeners. Do you have any thoughts about that or some of your own thoughts that you’d like to leave with people?

EC: I still stand by it. Speaking out about one’s body is profoundly feminist. It’s something that people involved with the women’s liberation movements from the ‘60s and ‘70s, they were working really hard to create systems of knowledge and care by demystifying this medical understanding that had always been claimed and held by men, that had been annexed away by the white-coated gods, the authoritative men. And they were resisting this or breaking this down, dismantling this power structure by creating caregiving networks, self-health networks, but most of all by speaking out and creating communities and groups in which they could speak for the first time about what it was really like to exist in a female body in a patriarchal world. And I always seemed to come back to this moment in history as the moment when– not the moment when women began to speak, but the moment when women coming together to speak about their bodies and creating spaces for each other to do that became a form of political resistance.

I feel so honored to be the generation that I’m in, who has benefited from that incredible bravery of all kinds of different women, of all races, sexualities, gender identities, coming together to create a culture in which we can find the courage to speak out about what it means to exist in our bodies. Because all throughout history, silencing and shame has been forced upon us. We’ve been forced to wear and carry with us this burden of male shame, and it isn’t our shame and it isn’t our burden. So I always feel incredibly grateful to be part of this generation that’s benefited from that bravery and also to imagine what might be possible in the future. And I already see from social media something that I didn’t grow up with but that I have as an adult, networks, resource sharing, information sharing spaces where the identity of being a woman in pain isn’t a diminishing one, where it becomes a different way to connect, it becomes a different way to see the world. I think that is incredible. So I would always say that if you have the courage and you want to speak out, you will then enable someone else to find courage. And if you can’t, then there are people there who will hold space for you and hold your stories.

AA: Oh, that’s incredibly inspiring. Thank you for that. I love you ending with that, Elinor, that was incredibly inspiring and uplifting. And as listeners know, we’re ending each episode with action items, so I just love that that can be what listeners take away, is really being brave and courageous and speaking about your own lived experience, especially in the medical field where actually we need women to speak up about their actual experience. We need more women to go into the medical field and to close the gaps of knowledge that persist in medicine. So, speaking out is a feminist act and I’m so grateful to you for writing that because that is something that I’ve carried with me. Thank you, Elinor. The last thing I’ll ask is where we can find your work. Do you have a website or social media handles that you can share?

EC: I am @elinorcleghorn on Instagram and I’m also on Bluesky under the same handle. So yeah, do get in touch.

AA: Wonderful. Well, Dr. Elinor Cleghorn, thank you once again for being here today. I learned so much from you. Thank you.

EC: Thank you so much for having me.

her value, her worth, and also her needs as a human

all center around reproductive function

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!