“documents from hundreds and hundreds of years ago continue to dictate modern life”

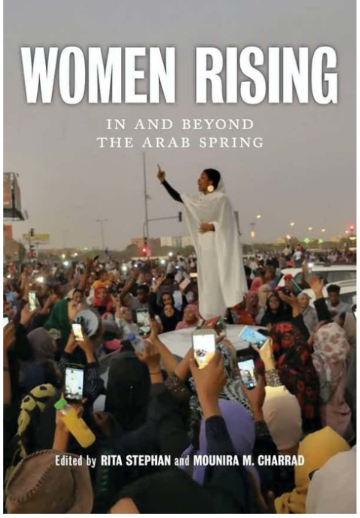

Amy is joined by Léa Namouni to discuss the anthology Women Rising: In and Beyond The Arab Spring and the work of women activists and organizers in the Arab World.

Our Guest

Léa Namouni

Léa Namouni was born in Paris, France and lived there until the age of five when her family relocated to the state of New Jersey. She holds a BA in International Relations from Boston University and will attending Columbia Law School as of September 2023 studying international law.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Can you remember a news story that stopped you in your tracks, and you’ll always remember where you were when you heard it? I remember a December day in 2010 when I pulled into a parking spot at Trader Joe’s and heard on the radio that a man in Tunisia had set himself on fire.

National Public Radio summarized the story this way: “Mohamed Bouazizi’s father had passed away when he was a child, so he had to start working at a young age. His mom worked at a farm making about $2 per day. Mohamed used to get up at 3:00 AM to fill up his cart with fresh fruit and station himself in front of the city hall to sell them. His job helped support the family. He sold bananas, strawberries, grapes, whatever was in season. According to his sister Leila, city officials constantly harassed Mohamed by confiscating his wares. They said he needed to get a vendor’s permit, which he couldn’t afford. He complained about this to his family, but pressed on because he needed to earn a living. On December 17th, 2010, the pressure became too much. After a municipal worker confiscated his weight scale, Mohamed Bouazizi got his hands on some gasoline and set himself on fire in front of City Hall. Witnesses captured the aftermath on their cell phones and the videos spread online. Shortly after his self immolation, protests erupted in Tunisia. People called for better living conditions, jobs, and dignity. Soon the movement spread to Egypt, where huge demonstrations led to the toppling of the government and all over the Arab world. This movement in 2011 became known as the Arab Spring.”

So, as we’ve discussed so many times before on this podcast, oppressive systems tend to interlock with one another. And the movement that began as a protest of untenable living conditions and government bullying in Tunisia soon included protests against gender inequity. This is the topic we’ll be highlighting today as we discuss the book Women Rising: In and Beyond The Arab Spring. It’s an anthology that’s edited by Rita Stephan and Mounira M. Charrad, and I’m so excited to be discussing it with my guest, Léa Namouni. Welcome, Léa!

Léa Namouni: Hi, thank you for having me!

AA: I’m so excited that you’re here. So, Léa, can you introduce yourself a little bit? Tell us where you’re from and what you do.

LN: Yeah, so I’m originally from Paris, France. I moved to New Jersey when I was five years old. Since then I’ve been in Boston, where I went to Boston University. I just graduated with a BA in IR. I specialized in Africa and the Middle East, and international world systems and world order. And I’m going to law school in September! So I’ve always been interested in international law, that’s kind of been my point of interest, and yeah, I’m really excited!

AA: Well congrats on graduating! That’s so exciting, that’s really awesome. And have you taken the LSAT? Are your law school applications in and you’re waiting to hear back, or what’s the status of your next step?

LN: So I actually just got into Columbia on Monday, so I’m set!

AA: Oh my gosh! So exciting! Good for you.

LN: Thank you! This is brand new information, but I’m really excited and I’m gonna be studying what I care about, so happy to be doing that.

AA: So exciting. Oh my gosh, Léa, congrats. Well, and I should mention to listeners that Léa is a good friend of my daughter Lindsay. So we have a personal connection too. So that’s super fun, that’s great. All of you guys are all graduating and I know Lindsay’s a little nervous about going out into the adult world and like, what are the next steps?

LN: I feel that a lot. We’ll get through it together, it’ll be okay.

AA: Well you going to Columbia, that is so awesome. Good for you. So this is really great too, because not only were you an International Relations major, that’s your degree, but you also have a personal connection to this topic too. Do you wanna tell us about your family background a little bit?

LN: Yeah, sure. So my mom’s side of the family is French, and my dad’s side of the family is actually from Algeria. Not a country I’m actually too familiar with. I wasn’t really exposed as a kid to the culture that much, which actually stimulated my curiosity a lot more cause I was like, I have family in this country that I don’t know much about. So that actually was one of the big reasons that I decided to study the Middle East and North Africa. Because I was like, I also have to discover this part of myself that I really don’t know. Which actually made learning about it a whole lot more. So yeah, I do have a personal connection.

AA: Yeah. That’s really, really great. Well, this was completely new to me, honestly. Like I shared, I followed what was happening in the Arab Spring, just honestly when I was in the car listening to NPR, and I cared a lot about it but I’ve never done any in-depth study of this topic. And so this book was so illuminating for me.

And maybe we’ll dive in just by talking a little bit about the book. It’s called Women Rising: In and Beyond the Arab Spring, and it was published by the New York University Press in 2020. And it brings together voices of women across the nations of the Arab region. And again, I’ll just admit my ignorance so listeners don’t feel like they’re the only ones if they don’t know this. But I don’t know that I could have actually given a correct list of which countries were Arab nations, right? Sometimes they get conflated, like wait, what’s Afghanistan? Or what’s Iran? And they’re actually not Arab nations. They’re Persian or they’re considered other classifications of Asian. So in the introduction, the editors give a list: there’s Libya, Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq, Morocco, Algeria, Bahrain, Yemen, Jordan, and Syria. And there are more, but those are the ones that I think the biggest articles are on in the book.

And each of these articles in the book represents one unique woman’s voice, and each woman’s voice represents a different point of view and highlights the immense diversity within the region, not only diversity of nations, but diversity of religion, and class, and urban versus rural areas, and sexual orientation, and life experience. And this is so important as we seek to expand our understanding, because the human brain is built to lump people into categories and make assumptions about them. And it takes work to resist that impulse and insist on complication, and contradiction, and nuance in our thinking. And in fact, on that topic, I want to start with just three passages from the introduction to start us off because I think they’re really important to have as a foundation. So I’m just gonna read three quotes from the introduction and then we’ll start talking about the chapters.

So, the first point. The introduction was written by the editors Rita Stephan, who is Lebanese, and Mounira Charrad, who is Tunisian. And they point out that the activism of Arab women for political transformation is over a century old. But, the representation of Arab women in Western news and popular culture perpetuates what’s called an orientalist trope of Arab women as silent victims. And Rita Stephan writes that, “This misrepresentation strips Arab women from their feminism and denies them agency and the ability to exercise their own approaches to local and global problem solving. Western scholars who claim expertise on global and Middle Eastern gender politics often misinterpret Arab women’s activism as lacking feminist consciousness or identification. Other Western feminists tend to believe that gender struggle is universal. In other words, women everywhere tend to face similar oppression merely by virtue of their sex or gender, and regardless of their cultural or geopolitical context. Therefore, these feminists assume that they can play a leadership role in saving and speaking on behalf of Arab women.”

Okay, that’s the first theme from the introduction that I thought was super important.

Here’s the second one. “Equally, misrepresentative of Arab women’s activism are transnational feminists who view gender inequality from a single global lens and assume that a unified identity exists among all victims of colonialism and imperialism. While colonial powers are indeed oppressive, past and present, Arabs’ relations with them have been complicated before and after the Arab Spring. Internal conflict and unusual alliances have made Western forces the lesser of two evils in some instances, and have aided Arab women’s resistance to their corrupt regimes, oppressive laws, and restrictive social norms.”

So the message I’m getting here is that it’s way more complicated than it looks. Again, it’s easier so our brains like to lump things together, right? If this is true in one place, it must be true in another place. And if this is a colonized area of the world, it must be like all these other colonized areas of the world.

They use the example of Iraq under Saddam Hussein in the introduction, and they say some outsiders might make the assumption that the United States was a liberator and a hero for Iraqi women. And then other Western outsiders might make the assumption that the United States was, oh, a Western invader and therefore they’re a villain for Iraqi women. And the introduction of the book says that both of those blanket statements are just too simplistic. It’s both and in some cases it’s neither, right? And so we need to just challenge all of those assumptions.

The third theme from the intro that I got was this quote. “Economically, one third of Arab countries are high income, and the rest are either high-middle or lower-middle income. Politically, Arab countries range among oil rich monarchies, dictatorships, and quasi-democracies. Socially, Arab norms vary between conservative Saudi Arabian and Westernized Lebanese.” Okay, so those are the themes that I got from the intro already. They’re challenging stereotypes that listeners may have absorbed from Western media. Did you have any thoughts on any of these quotes, Léa? I know it’s a lot there and I’m putting you on the spot.

LN: No, of course. I think what’s really difficult when you study these issues in the United States is figuring out what lens you’re putting on the issue. And what’s difficult is that these countries, a lot of them are put with this filter of Islam and we have this idea that women in Islam are only repressed, women in Islam do not have the same freedoms that we enjoy here. And I had a really great professor my sophomore year who had a whole lesson on fundamentalist religions and how when you take the extreme of a religion, how you can also view it as an economic investment. This is a very broad topic and I’m diving into it a little bit, but I do remember this lesson because it changed my perspective. You can’t ever view things as just too constricted. Like, you cannot view that these women are lacking freedoms that you have here because it’s a totally different context. And so what’s really difficult, I feel like when we study the Middle East is deciding you’re not an American. You have to be something else. You have to kind of figure out what lens you’re going to view these issues in, and you really have to push yourself to not immediately throw your ideas of your social, cultural context onto something else. And that’s way easier said than done. I do think that if I traveled and I lived in one of these countries, I’m sure my perspective would change even more. But I think it’s something that you really have to focus on when you’re not studying an area that surrounds you. It is more interesting of course to do that though, because you’re doing something different. But it’s something that in IR I notice really has to be done and that a lot of our professors push when they share these kinds of issues.

AA: I think that’s so great. And that’s why travel really is so important, and the longer you stay in a place and the less touristy you do your trip the better. But travel’s also expensive and is a real privilege, I mean, to take time off work and to go all around the world. And so that’s why we love books, right? .

LN: We love books, really helps expand the perspectives.

AA: Totally. Yeah, exactly. And hearing from the people that for whom it is their lived experience, right? Okay, well speaking of that, let’s dive in and you have the first chapter, Léa, do you want to orient us to chapter one?

LN: Yeah, of course. So it’s funny, as you told me I could choose any chapter of the book and there were so many, and I turned the page after the introduction, I was like, I’m gonna do this one. I thought the title was really interesting. And the more I read about it, the more I realized how complicated it must be to be a woman activist in this context, because it talked about education and how difficult it was to kind of push women who are interested in learning about feminism on a global scale to question their surroundings. And it talks about this almost five step process of learning to undo what you’ve been surrounded with your whole life. And so it also shows education as this powerful tool that doesn’t necessarily tell you what to think, that just gives you the tools to think about something new or think about something differently. And I was struck by the poem that was in this chapter because it just shows this like whirlwind of emotions that these women are feeling when it comes to questioning the patriarchal surroundings that they have. And it talks about panic and sadness and realizing, oh my God, there’s actually so much more to this world. And then all of a sudden realizing, oh, I can be an agent of change and I can really mobilize. And so I chose a little excerpt from the poem that really stuck out and I think it’s from the part of the poem entitled “Revelation” because they all have different little titles. And it says, “I am no longer a tenant of my body. I am no longer enthralled in snares of silences. I am me, birthing a new life into my soul, catalyzing change and becoming an agent of change.”

what’s really difficult when you study these issues in the United States is figuring out what lens you’re putting on the issue.

And I think what’s so beautiful is it shows that deciding to be a part of these movements in the context of these Middle Eastern countries – and I’m not trying to throw them all together because they’re all different in their own ways, of course – but when you’re surrounded by such oppressive forces, learning about these global topics, female liberation, I feel like the process can’t just be that simple. You really have to go through a lot of emotions to question everything that you were surrounded with for so long and what your reality was. So I thought that poem was a really great way of capturing the difficulty in doing that and the respect that we have to feel for women who have been doing this for so long, which is why it really stuck out to me.

AA: Yeah, thanks Léa. I loved that chapter too, and I loved the poem. Okay, one chapter that I wanted to highlight is chapter six, and the chapter title is in French, so I’m going to ask you to read it because you speak French and I don’t. Will you read it?

LN: “Ne Touché Pas Mes Enfants”

AA: And that means “don’t touch my children,” right? So this is a woman’s campaign against pedophilia in Morocco, and it’s a really hard chapter to read. It’s really hard to read accounts of sexual abuse against children but I thought it was so important. And something that I’d never thought about before, how patriarchal structures actually can sometimes enable pedophilia. I’ve just never thought of that topic before. So the chapter tells the story of a mother named Najia Adib, whose three-year-old son was abused at his preschool. And she proved through a DNA test that the abuser was the director of the school, and he confessed to molesting multiple children during his 18 years at the school.

And I’m just gonna read this quote in the chapter. It says, “Despite the director’s confession and the evidence against him, the judge sentenced him to only two years in prison. Angry at the lenient decision, Adib exposed the scandal in the media and knocked on many doors until the sentence was eventually increased to eight years. Adib was the only parent to speak out, and was shocked to learn that no national association existed in Morocco to defend the victims of child sexual abuse. Resolved to raise awareness of the problem of pedophilia, help victims pursue justice through the legal system, and advocate for tougher sentencing for predators, she founded Don’t Touch My Child in 2004. In 2010, the Arab League recognized Adib as the first Muslim Arab woman to speak out against child rape and appointed her as ‘ambassador of the Arab child’ for her efforts in the fight to end sexual violence against children at the national and international levels.”

So the next thing that the chapter points out is that speaking out against pedophilia has been taboo in Moroccan society. And the cases are frequently dismissed and in general, victims of sexual abuse are hesitant to come forward because there’s a taboo against it, right? So they feel like they will be the ones to be shamed, there might be reprisals and they feel guilty. And the chapter says, “Moroccans view the loss of virginity among unmarried girls, even in rape cases as a social stigma that dishonors the entire family. Although rape is a criminal offense with tough penalties, there was an escape clause for rapists because until 2014, it allowed families and judges to force girls to marry the accused rapist in order to restore the family honor. The ramifications of this law came to the forefront in 2012 with the case of Amina Filali. Amina was raped at 15 by a 23 year old assailant and was later forced to marry him. Continuing to be abused by her now husband, Amina took her own life by drinking rat poison and dying in the street. Public outrage and massive demonstrations over her suicide demanded a change to Article 475, and the article was amended to allow the victim greater voice in the decision of whether or not to marry the alleged rapist.”

Ah, it’s so hard to read. And this will remind listeners of our episode way back at the beginning of Season One when we talked about the code of Hammurabi in the Middle Assyrian Laws, which were written in 1500 BCE, and it’s the same. You can see it really hasn’t changed. Because if a woman is seen as the property of the man who owns her, then if she’s raped she’s damaged goods and she can’t be sold to a future husband. So she’s lost her value and brought shame on the whole family. Which is why there’s a taboo, no one wants to talk about it. So the rule is like, you break it, you buy it. You damage my goods, you have to purchase it because I’m not gonna be able to offload the girl to anybody else. And it’s just thought that the person who’s been wronged is the girl’s father and brother and not the girl herself. So there’s this through line to just ancient, ancient documents.

LN: It’s just crazy to me how they will never be, or in these situations, they’re never the agent of their own lives. And the other thing is how documents from hundreds and hundreds of years ago continue to dictate modern life, and I think we’re seeing that those contexts really just don’t apply anymore.

AA: So another aspect of this that the chapter points out is that pedophilia is a taboo topic because child sexual abuse is often a crime close to home, because it’s often perpetrated by family members, family friends, or neighbors. And in this case that we talked about at the beginning, it was the child’s teacher and again, he had been teaching at this preschool for a long time. The chapter includes some data from the World Health Organization, which estimates that 90% of child abusers are family members or family friends or mentors. In Morocco, 75% of child abuse cases are by family members. And so it makes sense, of course, families are hesitant to prosecute their own family members, and so often they don’t officially report the crime. And again, I get it, but it’s still protecting the criminal and the criminal almost always is a man. And in a culture where men have power and women are trained to be compliant and subdued, it’s not surprising that the system would protect the men and silence the women. In this case, the mother. And I’m sure this is what usually happens, right? A woman is either the victim or the mother of a victim when they find out about the children’s abuse.

So the chapter does point out– I was grateful to hear this, and again this book was written a few years ago so changes have happened since then, but it points out that Moroccan law does have articles that are aimed at protecting children. But another problem that comes up is that rape is narrowly defined in the 2003 Moroccan penal code as “the act by which a man has sex with a woman against the will of the latter,” like against the will of the woman. So this is obviously way too narrow of a definition for many, many reasons, but also the heteronormativity of this model fails to protect boys from sexual abuse. And this was the case with this woman whose son was the victim of sexual abuse. So the chapter talks about her becoming an activist fighting against sexual abuse and gender-based violence. She dedicated her life to it and advocated for many, many victims. She identified that there was an urgent need for overnight shelters and safe houses for victims who were trying to get away from abusers. It says that it was a criminal offense to harbor a married woman, even someone escaping abuse until 2013. And there are still many norms in Morocco that make it difficult for women and children to escape from abusive situations.

And the end of the chapter was actually so depressing because it ended by talking about this specific case, and it says that sadly, Adib learned that the pedophile who had molested her child was released in 2013 without rehab, without probation or monitoring. And he has opened a daycare center in another town under a slightly different name. So there’s just no structure to hold him accountable.

LN: That’s, that’s crazy. But also it makes you realize too that these systems aren’t just damaging towards women. Because his victims, it doesn’t matter what gender they are, they’re gonna grow up with that trauma. And that can’t be good. Of course, there’s no way that that’s good for anyone. It’s damaging towards everyone. It’s really wild to think about how there’s no change even after the years, you know, roll by with these continuing trends.

AA: Yeah, it’s so, so sad. But also inspiring because this woman is fighting so hard and she has saved so many people, helped so many people who have already experienced abuse and then prevented abuse in so many cases too. So she is doing really, really great work. Okay, Léa, what was another chapter that stood out to you?

LN: So, the next one that I read was incredible to me. It’s called “Two Non-violence Campaigns in Syria,” it’s chapter seven. And I was really interested in this chapter because I had not heard of any women-led movements in the context of the Syrian war. In international relations we learned about the agents being countries and governments. We never learn– Well, depending on what you focus on, I don’t focus on this that much. But we don’t ever really learn about individuals. I think one of the first times we actually learned about individuals was learning about the beginning of the Arab Spring because of Mohammed Bouazizi. And the other thing that I thought was interesting was we mostly only hear about women as victims rather than victors. And I think that’s a direct quote in the chapter. How these two movements really change that narrative.

They start out by talking about how both militarization and Islamic radicalization marginalize women activists, which is what makes these two campaigns particularly incredible, because that was when those two concepts were really on the rise. So the first campaign was the Stop the Killing Campaign, and it started in April, 2012 with 32 year old lawyer Rima Dali. And she decided to hold a banner in front of Parliament in Damascus, and it read “Stop the killing. We want to build a nation for all Syrians.” And so she’s standing in the middle and a guard comes up to her and asks her what side she’s on. And she says, “I am a Syrian.” And what’s interesting is that in Arabic, what she says not only means “I’m a Syrian,” but it means “I’m a Syrian woman.” And then after this movement, what’s really interesting is that 26 events followed. So she was able to mobilize a ground network through grassroots organizations. And it’s another really great example in the Arab Spring of one person really being able to create something huge.

I was curious to see if technology played a role in this at all, as well. That’s a big topic I feel like with the Arab Spring, of how things are filmed and then just diffused all over. But there wasn’t that much talk of that in this chapter, so that was something I was curious about. And then the second campaign, and this one I think I had heard of before but I wasn’t really sure, was the Brides of Freedom campaign. And so for this one, four women dressed up as brides in a market in Damascus and showed up holding a lot of different signs about not wanting violence and death, and then also about being 100% Syrian. They were filmed and then they were taken away by authorities, which was also filmed. And they were then imprisoned for 49 days in Syrian prisons, which were known to have particularly brutal conditions. And the chapter talks about how together these campaigns really show the creativity of women in their activism in Syria. They talk about all the different symbols and the meticulous planning that went into it. For example, I didn’t even think about this, the colors that were used in the signs and the dresses, everything that went into the visuals, avoided evoking any particular side. The goal was to keep everything neutral. So there couldn’t even be the colors of the Syrian flag. And another part that really shows to me how strong they were, was how impressive it was to keep their movements non-violent. One of the quotes from the chapter is, “the rise of militarized discourse within a social movement contributes to patronizing attitudes towards non-violent resistance.”

So while everyone around them in these other movements resorted to violence, these women were able to stick to a non-violent method. And I just think that’s so incredible, especially because they had so much negativity towards them for that.

And then another part that the chapter talks about that I thought was really impressive was the role of gender. So, Stop The Killing was a non-gender specific campaign and Brides of Freedom was gender specific. What’s interesting about Brides of Freedom being gender specific is they really used the symbol of the bride as this symbol of peace. In a New York Times video that I looked up about this campaign, the women who were dressed as the brides talked about how they wanted to look for something that in every culture around the world is a symbol of peace. And so I think it was their dad that said, “what about a wedding dress?” And so then they used a wedding dress as a symbol of peace, and I think that was really beautiful. And I just think between creativity, keeping the nonviolence, and thinking so meticulously about every single part of what this was going to look like, including the video. They made sure that the video captured the authorities taking them away. I just think it’s so impressive how these women were really able to push their narrative so far, even if it was just four of them or one of them at the beginning. That’s something that I love studying about the Arab Spring. It always starts with one small little thing and then it just explodes. And I thought they were really powerful for doing that, and I’m surprised that there hasn’t been more media coverage on specifically women mobilization movements in Syria.

AA: That was actually exactly what I was just gonna say, that I just wish during the whole Syrian war, again, I’m just a radio listener in the car. As I’m listening about the Syrian war and weeping as I’m hearing about the violence, or reading about it in the news or whatever, why did I never learn about this? Why did I never learn about the women who were resisting and fighting so bravely? I really wish that that had been covered more in the media. It’s so frustrating that it’s not.

LN: Yeah, definitely. Also, most times we talk about the Arab Spring, technology is always linked. Like there’s always talk about Facebook diffusing these images, Twitter, and then I’m here like, well, I use Facebook and Twitter still and I still feel like I’m missing things. Like the movements in Iran with regard to Mahsa Amini and the hijab, and people being just completely mistreated by the morality police. I learned about that through Instagram, Twitter, all of my social media. But even before that, I feel like I hadn’t had enough information diffused to me about these kinds of movements. Like you said, I read the news, but that’s about it. And so I think it’s interesting what reaches me and what doesn’t.

AA: Yeah, for sure. Well, thanks for highlighting that chapter because I loved that chapter too, and thought it was so important. And you chose the next chapter too. I think it’s chapter 14. Do you wanna dive into that one?

the rise of militarized discourse within a social movement contributes to patronizing attitudes towards non-violent resistance

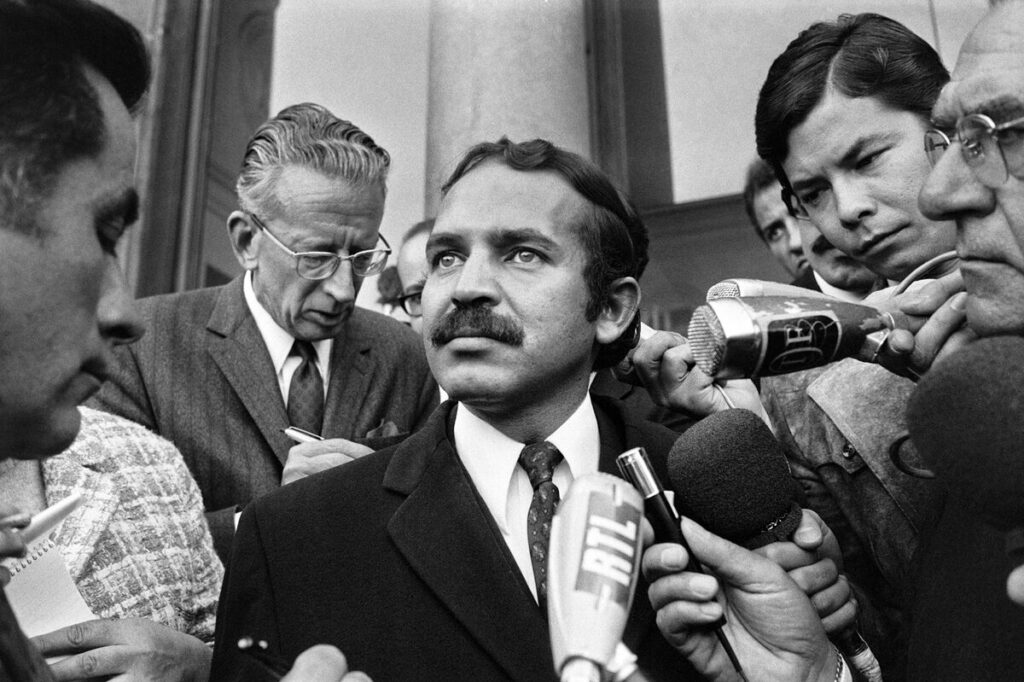

LN: Sure. I chose this one kind of selfishly because it talked about Algeria. And I’m always curious, you know, of course about Algerian politics. They basically talk about President Bouteflika and how women, feminists in Algeria were able to kind of bargain with him to tone down some incredibly repressive rights in Algeria that had been established by the 1984 Family Code. What’s interesting about Algeria is it hadn’t always been that way. When Algeria gained independence in 1962 there was a lot of different movements between presidents. So I think they had Ahmed Ben Bella and then he was taken down by a coup, and then you had Houari Boumédiène. And then you had different struggles between the FLN (National Liberation Front) to try and gather a constitution that was somewhat socialist and did actually protect women’s rights pretty well.

But I think you had another president hop in and I don’t remember his name. But you basically had huge movements of anger because the economy was totally broken down. I think the employment rate was around 70% because with French independence a lot of people left and so the economy was in shambles.

And then eventually, and I think the timeline is more towards the eighties, you have these Islamist activist movements rise out of that anger. And after a new president hopped in, Colonel Bendjedid, so after Colonel Bendjedid was appointed, he was a little bit more moderate, and so when the waves of Islamist movements came in, there was a new constitution approved by him in February of 1989 that dropped the word socialist and at the same time withdrew all guarantees of women’s rights that had appeared in the 1976 constitution that was sponsored by the FLN (the Front de libération nationale, the National Liberation Front). And so what’s interesting about this is when Bouteflika is elected, I think he was pretty popular. He had like a 70% support rate, was big on keeping that support, and so kind of sticking with that Islamist narrative because that’s where his support was coming from. But then he still kept this bargaining with feminists. And what was interesting is he did give them actually quite a few rights. For example, I think he got rid of the 1984 family code like they said. He brought back the right to divorce, for example. And so he changed a few laws because of these feminist grassroot movements.

It wasn’t the best of situations either, there were concerns over the lack of implementation, the lack of awareness over these rights, which I thought was really interesting. There was huge concern that women wouldn’t even know that these changes had happened. And so if they don’t know that they happened, has anything really changed is the question. And then there was also concern, in the chapter they mentioned about the lack of institutions. And so the chapter ends talking about how overall he was considered a champion for feminism, for women. And then actually really recently, he lost all support in 2019 which led to his resignation that had I think a little bit more to do with repression of freedom of voice. And COVID I think also had a lot to do with it when we got to 2020, and I think he actually recently passed away. So that’s kind of the end of that story.

But I thought it was really interesting to look at bargaining power in a patriarchal system, especially in one where the kind of extremes of a religion really take over the laws and there’s not that much room for bargaining space. But there was still that relationship there, which I thought was really, really interesting.

AA: Mm-hmm. That is really interesting and I’m so glad you brought out that last point too about, you know, if women don’t even know that their rights have changed, does it make any difference? And we’ve talked about that before on other episodes about how sometimes the United Nations will make some really beautiful, inspiring proclamation like, this is how the world should be, and these are our values as a world. And there’s no structure in place to implement or enforce those things. And so it’s still good, I mean it’s an aspiration and it does make a difference for people who read it. But that’s always a challenge. To publicize and then enforce is always really tricky and really important.

Good, I’m glad you’re going into law, Léa, because that’s one huge piece of it, right? Is the legal aspect. I mean even just thinking, not to go on too much of a tangent, but thinking about Brown v. The Board of Education in our own country. And that the Supreme Court saying we cannot segregate in the United States, that was critical. Nothing would’ve changed without it, without the law. So that’s so important. And then on top of that, there’s the implementation and the Attorney General needs to get involved and send down US Marshals to actually force the people to obey the law, right?

LN: And the media has to get involved, like people have to know about it.

AA: Yes!

LN: There has to be some kind of a press release, but then people have to talk about that press release, which I always think, how does the news actually get out there? I even think about it where I live now in Boston. I’m like, do people know that laws change in Boston? Will I ever be aware ? How do you know that these things happen? I think about this pretty often because I feel like I’m really unaware of our legal system sometimes.

But yeah, it really got me thinking, if they did all this work to bargain with a leader who wasn’t totally on their side, and then to have him change a law and then for people not necessarily to know that that law even changed… And I feel like all that hard work, was it for something? How do people get to know that information?

AA: That’s such a good question. I’m gonna be thinking about that more because, sorry again, this analogy to the civil rights movement. But as I’m sure people know, and we talked about this a little bit on a prior episode, the voting rights activism in the 1960s where they would go to rural communities especially and tell people and say, “You can vote! You are legally protected. We’ll walk you there. We’ll help.” And people didn’t even know they had a right to vote. So how does information reach the people who really need it? That’s such a good question that we’ve never really considered. Important question.

LN: Important question. Start for next time.

AA: Yes, exactly. Okay, what’s the next chapter that we were going to highlight? I think this one was about Egypt, right, Léa?

LN: Yes, yes, yes. So this chapter talked about three women’s sexual harassment campaigns in Egypt, and how impressive it was for them to take off considering how repressive the Egyptian government had been. So they start talking about this conversation around social media and Egyptian youth. And what was really interesting, and I think I’ve heard this before in a gender politics class, they talked about innovation and use of technology only being seen as male. And I thought that was super interesting because I was like, oh my God I had not thought about it that way. But it’s true that we only really associate new tech and new discoveries within that field as kind of a male thing.

And so their main argument was that many women’s movements in fact worked to engender the kinds of proactive, community-based, and even technology-facilitated activism that has come to be associated with the 2011 revolution. So their goal is to talk about how women actually can be innovators with tech and it can have real effects in places you really wouldn’t expect it to. They also start with talking about how this kind of activism is gonna focus on street harassment, particularly because it limits women’s mobility and they use the word “ghettoizes” women into private spheres.

So the first one that they talk about is HarassMap, and there’s an emphasis on it being completely separate from the government in any way for fears, of course, that it would be tampered with.

AA: Can you explain exactly what it was? What was HarassMap?

LN: So HarassMap was, I think it was an app. I wasn’t sure if it was an app or a website, where basically people in the streets or on the ground could write whether the area was risky or safe. And they could basically note where an act of harassment had happened. And so I believe that it was most used by not only women, but also by shopkeepers or people who were regularly in the area. To the point that the app itself or the website would use a safe zone sticker to constant users who had always diligently kept track of the area and whether it was safe for women or not.

They said that it was kind of like a social media app because it was used in that way, like to track where you were and how safe it was. And what was cool about it was that it had a really communal focus. It was a group effort and it really had to do with women – and also men who were allied, I guess, to women is the right word – to make the app work. And they also really wanted to stress that it is totally different from the work of organizations who work with the government and work with the law. Like this was something that really had to identify itself separately from the Egyptian government, which made it a riskier environment to work in.

And what was also really incredible about it was, I think a lot of the narrative on the Arab Spring has to do with Facebook and Twitter, like I said before, and this was a totally new medium that also served with that cyberspace innovation part of the Arab Spring. And it was created by women and it wasn’t created by men in other countries, you know what I mean? It was totally different and had a real effect. But another thing is we haven’t heard about it. That’s the other thing. This wasn’t publicized. At least to a point where I guess they didn’t really pick up that much media attention, even though I think this is technology that could help in multiple other countries.

Honestly, I would use this in a lot of cities in the US, I feel like. But they didn’t pick up a lot of media attention. Unlike the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights that actually used media to protect themselves from the government. So, they talk about this Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights in the context of a public assault that happened after a movie theater’s lack of tickets. So, legitimately men went to the movie theater, there weren’t enough tickets, and then they just publicly assaulted women on the street. Which I was like, I read that sentence, I was like, wait one second–

AA: I know, I did too! I was like, “wait, what’d I miss?”

LN: I feel like I missed a couple lines. I was like, really? It reminds me of, did you ever read the study that was done about the UK and how whenever a soccer game is lost, there’s an uptick in domestic violence rates?

AA: Oh my gosh.

LN: It really reminded me of that. And maybe we have to start taking our anger out in different, more healthy ways.

AA: Yes, absolutely.

LN: But they talk about how this incident was highly under covered in the press, which I thought was shocking because that, I feel like would get a lot of attention. And the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights had been working on a campaign that discussed these occurrences, and most notably, the government’s failure to address them and to just push them under the rug. And so after this incident, they were really, really smart and they went directly to local and international media help. And so the idea was that they could continue their campaign as long as they did it in a public light, because that way if the Egyptian government had ever gotten their hands on them, then it would be shown to the public and then they would be shamed. Which actually is a pretty common tactic used in international relations. Often we talk about in human rights “name and shame,” which a lot of organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International do. Their goal if the law can’t work to help them in their favor is to shame a country to the point that other countries go, “oh, that’s really bad,” and then they’ll be incentivized to change it.

So I thought it was really smart that they were doing that, especially because they talked about how the Egyptian government had been trying to stop their endeavors before, and tried to stop them from doing all of their anti-harassment work, especially their studies. So because of this, they were actually able to conduct proper field work because they had more access leading to a detailed study about harassment. And now they no longer really had to worry about the government because the media knew exactly what they were doing. And so the findings were really interesting. They weren’t exactly surprising, like when they said the results I was like, yeah, I kind of see that being the reality. But they basically said that there was a lack of legal channels for harassment response. That harassment, specifically the one we had been talking about, street harassment, was a pervasive issue. And most importantly, there was no public attention paid to it, no media attention paid to it, and the government also didn’t care.

street harassment, was a pervasive issue. And most importantly, there was no public attention paid to it, no media attention paid to it, and the government also didn’t care.

And there was a line that really stuck out to me, and it was: “The vast majority of women surveyed in the 2008 study did not seek police assistance because they did not think it was important or because no one would help.” That they didn’t think it was important shook me to my core. Because I can’t imagine living in a place, I mean I’m not gonna say the US is the best, but I feel at least I would consider it an important issue here. I don’t know if that’s my surroundings, but I would consider harassment to be a pretty big deal. And the fact that it isn’t considered important and that’s why someone would not call, they wouldn’t think of it as an important crime, really surprised me. I would feel so unsafe all the time. And that just really shocked me, which is why I thought this work was so important and I’m curious to see what this study ended up concretely leading to.

AA: One thing that I thought of as you were saying that, because I absolutely agree, is that I think different places are at different points in their progress on each different issue. And I just think even just two generations ago, even in the United States, harassment wouldn’t have been seen as a big deal. Right? I think that’s something that somebody said, “no, we’re changing this,” and then it’s gradually happened. I mean starting with second wave feminism in the sixties and seventies. Have you ever seen Mad Men? Have you seen that show?

LN: No, I haven’t.

AA: It’s really good. It’s a little slow, but it’s so interesting. You just see this unbelievable (to us now) sexual harassment of women, and it’s just life. You kind of don’t even bat an eye. They don’t like it, but it’s really striking to see that in that generation, which is just my mom’s generation, how different it was. And made me appreciate the changes that have happened, and then of course with the #MeToo movement, that’s why to us we’re like, how? What? People didn’t even care? And I think it was like that even here, not that long ago.

LN: Yeah. I realize I say that, but at the same time there’s still huge issues with actually condemning harassment. Like yes, if someone came to me and said something about it, I’d be like, oh my God that’s a huge problem. But will it be taken care of as a whole other question, which is definitely still something we’re very much dealing with in the US today. But I feel like at least what I’m surrounded with, if I told someone something about harassment, they would go, oh my God. You know, it’s still important. Whether it will be dealt with well, is a whole other question unfortunately. For sure.

AA: I was just thinking too, it wasn’t even just my mom’s generation. The stuff people would say to me, and I’m not really old yet, the stuff people would say to me specifically like in middle school and high school. My kids, I’ve told them a couple of things that boys would say to me and my friends all the time. It never even crossed my mind to tell an adult, to tell the principal, to tell the teacher. I would’ve been so embarrassed and felt guilty and like I was going to get in trouble or something. Never told my parents. Just like scary and really explicit and really offensive stuff got said to me all the time. So yeah, I’m grateful. I’m grateful because when I tell my kids that, they’re like “Mom! How?” They can’t even believe it. Hopefully things are changing all over the world.

LN: Yeah. I feel like awareness hopefully is getting better. But I wonder if you brought it up today, I hope something would come out, some kind of repercussion. I just feel like that’s not ensured, which is kind of sad. So I guess maybe we’re not that far off, but it’s really wild to think about.

So the third campaign that they talked about has to do with the El Nadeem, which is an anti-torture organization founded by four doctors, and they focus on those detained in 1977 during anti-state demonstrations per Egypt’s emergency law. And so what was really interesting about their study and the kind of work that they’re doing is that it really focuses on healthcare, particularly for people experiencing violence, which includes women. And so what they did is they looked to publish testimonies of women and victims of human rights violation, with a particular focus on torture. Which I always think is pretty powerful, because I feel like adding a testimony puts a voice to numbers. Like when you publish a study that says 50% of people this, 20% of people that, it’s really hard to visualize what that actually means. And I think putting words to that like really adds some emphasis that kind of humanizes it more.

AA: And just to be clear, Léa, so we’re talking about, like you said, 1977 people who are doing anti-state demonstrations. They’re detained, they’re taken to jail, and there’s testimony that women are being tortured while in custody, right?

LN: Yes, and not just women.

AA: Yes, lots of people are being tortured and so the El Nadeem Center is looking at these human rights violations while in custody.

LN: Yes. And they’re looking to publish testimonies specifically, that was their goal. And so they look to publish a study consisting of assessing the prevalence of violence that women were experiencing. And it’s the first study of its kind. This also being general, by the way, general violence.

They looked at women’s perceptions of gender violence and harassment, specifically attitudes women have towards their experiences. Which I thought was super interesting because I had never heard of any kind of article talking about how women saw their own experiences, how they genuinely felt about them. And what they found was that they rejected the violence happening to them. It wasn’t considered natural to them, and they all wanted anti-violence protection. And what I think is so, so important about the results of this study is that no, this is not natural to this community in a different country and another part of the world.

I feel like another narrative that pops up with human rights issues is that oh, we shouldn’t do this here or do that because it’s cultural, it’s religious. It’s normal for them. That kind of thing. But here we’re establishing this is not normal. This is a human rights violation. Even if we’re in this country, in this other part of the world, you should be paying attention to us because women want these protections and aren’t being granted them. So I thought it was really interesting what they did.

AA: One thing that came to my mind too, when you were talking about the importance of telling stories and getting actual witness statements, like “this happened to me,” thinking again about the Iranian revolution that’s happening right now. The fact that it’s being recorded on cell phones, and this was happening in the Arab Spring too, of course, which is why it spread so fast, was people recording on cell phones. And you can see like, you’re not making it up. It’s a person with their face bashed. It’s a person who’s being dragged by police. And it’s just so powerful and important to have the ability to record exactly what happened. And so you don’t have to guess if someone’s being honest or maybe stretching the truth a little bit.

Well, that brings us to the end of the conversation. It’s such a great book and I really recommend that listeners get it, or see if you have it at your local library. Again, it’s called Women Rising: In and Beyond the Arab Spring. And as we wrap up, I would love to ask you if you have any takeaways, Léa.

LN: Definitely. I think it was a very different perspective than I’ve received at school so far. Everything that I think I’ve learned about the Arab Spring has been more historical, like government level. When we talk about mobilization, it is not ever centered on women. It’s actually probably more violent things. You know, isn’t as enjoyable to talk about. And what I think is so powerful is individual testimonies and hearing these perspectives and actually realizing that this has been a trend for so long, is really eye-opening. And I hope that books like this and perspectives like this get more attention over the years. So we can help amplify these voices, because I think they’re doing such important work in places that are– it is so hard to do this kind of work. It was really eye-opening and I look forward to learning more about this. So, thank you so much for choosing this book.

AA: Yeah. Oh, thank you. I’m so grateful that you read it with me and that we could have this discussion. I agree with you. That was my takeaway too. Just wow, so many strong women and just their courage, like you mentioned at one point in our conversation today, sometimes alone, right? Speaking out alone. And then a couple of people would join them and then a couple more. But you know, when they acted in the beginning, they didn’t know if it was going to turn into a big movement, but they knew it was the right thing to do and they did it. And that really does challenge, like we said at the beginning, the trope of the woman in a Muslim majority country that she’s just a silent victim. No. These women are smart and brave and strong, and risking their lives and made a huge difference in their countries. And I’m just honored to have been able to learn about them and to talk about it with you today. So thanks again, Léa.

LN: Thank you!

It always starts with one small little thing

and then it just explodes.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!