“it is ultimately a business”

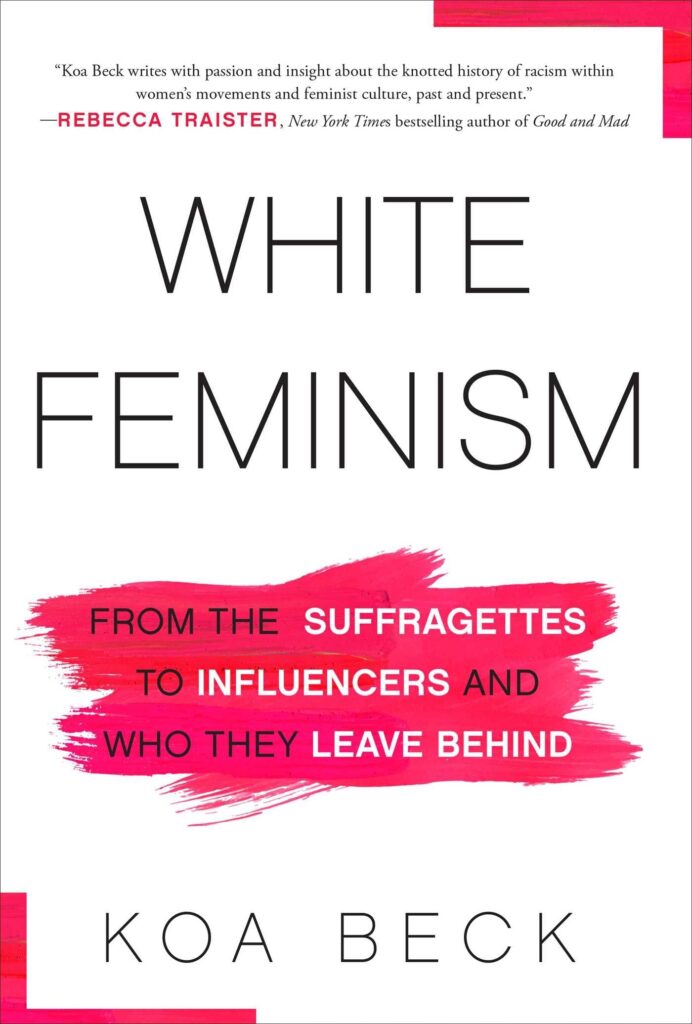

Amy is joined by author Koa Beck to discuss her book, White Feminism: From the Suffragettes to Influencers and Who They Leave Behind. This conversation defines white feminism, explains why it can’t overcome patriarchy, and offers practical alternatives for white feminists to change tactics and make more meaningful change.

Our Guest

Koa Beck

Koa Beck is the author of White Feminism: From the Suffragettes to Influencers and Who They Leave Behind. Previously, she was the editor-in-chief of Jezebel, the executive editor of Vogue.com, and the senior features editor at MarieClaire.com. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The New York Observer, The Guardian, and Esquire, among others. For her reporting prowess, she has been interviewed by the BBC and has appeared on many panels about gender and identity at the Harvard Kennedy School at Harvard University, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Historical Society, and Columbia Journalism School to name a few. She lives in Los Angeles.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: This season, we’re centering action, taking time to assess where we are now, and what we can do about the patriarchal culture in which we find ourselves. But to determine what actions we take, we need to take stock of the ways we’ve been engaging in anti-patriarchal work so far. What’s been working well in the feminist movement, and what hasn’t? As longtime listeners know, after four seasons of exploring our feminist history, there have been plenty of mistakes along the way. One of the most powerful concepts that I’ve been learning during the past few years has been that of white feminism, wherein white women have tended to focus on winning within oppressive systems rather than dismantling oppressive systems. One thinker I’ve learned this from is the amazing Koa Beck. In 2022, I read her book White Feminism: From the Suffragettes to Influencers and Who They Leave Behind, and I still think of that book as foundational in my learning on that topic. The book shows how the legacy of exclusion that we’ve inherited still lingers. And above all, the book is an invitation for white feminists to get educated and do better. It’s a book filled with fascinating history, incisive insights, and hope for a more diverse and more impactful feminist movement in the future. I am super grateful and so excited to be discussing this book, White Feminism, today with the book’s author, Koa Beck. Welcome, Koa!

Koa Beck: Hello, thank you so much for having me.

AA: Koa Beck is the author of the acclaimed nonfiction book, White Feminism: From the Suffragettes to Influencers and Who They Leave Behind. Previously, she was the editor in chief of Jezebel, the executive editor of Vogue.com, and the senior features editor at marieclaire.com. Her reporting and analysis on gender, identity, race, and culture have been published widely, and she has spoken at Harvard Law School, Columbia Journalism School, The New York Times, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among other institutions. She lives in Los Angeles, California with her wife and daughter. That is the professional bio that we like to start with, but before we get started digging into the book, I’d love it if you could introduce listeners to yourself a little more personally. Tell us where you’re from and what brought you to do the work that you do now.

KB: Of course, and thank you for that really contextual intro, not just with me, but your own avenue towards understanding white feminism and its limitations. As an author and writer on this topic, I appreciate that. I appreciate hearing how people come to this concept, whether it’s my book or something else. So, thank you for including that. I am a journalist and a writer, as you just read. I worked for a lot of my adult life in mainstream women’s media. The timing of that is very important, which I get into in the book, in terms of being at these really mainstream publications at a time when “feminism,” however you want to think about that or quantify that, but the word was actually being addressed within mainstream pop culture. So much so that a magazine like Cosmo or Marie Claire would put “feminist” in a headline, address a female pop star about her “feminism.” It seems very, in some ways, dated to say that now, because that’s just part of the talking points of a very visible, famous, influential person. But in the book I get into how when I was growing up, to be a feminist, this was a dirty word. This is something that you did not want to be called either in an intimate setting or any sort of public setting, definitely not a work setting. There were a lot of stigmas around who a feminist is, a lot of homophobic digs about what types of women support feminist politics. It was considered a way of basically declaring yourself completely undesirable. And there are a lot of reasons as to why that is.

I went to, and this is also documented in the book, I went to a private women’s college in Northern California, and prior to that, I had gone to a public co-ed high school in Los Angeles, where I was raised and where I live now. Going into a private school that at the time was single sex and was very, we used to say that everybody kind of minors in gender studies regardless of what your focus is, because the school would bring a lot of feminist and gender critique into everything, whether it was art history or chemistry, in my case, English. So I really learned about feminist theory and gender theory in both a pretty sanitized way because it was a classroom, but in a kind of informal way, you know, sitting on my professor’s floors, very small class size, I got a lot of attention in terms of mentorship, and a lot of professors who were able to really get me to think critically about gender and feminism. And I read Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble, or at least an excerpt of it, when I was 18 and I had to take that apart in a way that would be challenging for any 18, 19 year-old, especially living in a Western country like America. But that’s all to say that when I graduated and then when I started working and wanting to write as a profession, all of a sudden you could use the word “feminist,” suddenly these different mainstream outlets that I wouldn’t have thought to apply to given the school I went to, the politics that I was raised in, they were explicitly hiring “feminist editors.” This was well known in New York at the time, somebody with some sort of gender consciousness. And I really didn’t see that coming, but I was happy to accept a job, especially with health insurance, as a very young person. And that I would be able to address a lot of these concepts that I did learn in school but were also very important to me politically.

As I got more into my mid to late 20s, though, and this is also documented, I started to realize in these newsrooms where I was working with other women who did identify as feminists and did use that word, when we would talk about “feminist pitches” or “feminist ideas,” “feminist packages,” I started to realize in real time that we were actually talking about very different things. For a lot of these women I worked with, women who I reported to, “feminism” had to align with earning capital, building a business, going to an elite college, getting an elite job, really a lot of middle to upper class markers. And me being a very earnest 27 year-old, I was trying to pitch stories on affordable housing and poor women not being able to afford diapers. To me, this was a feminist cause. And for a lot of the institutions and bodies that I worked under, those realities were simply not recognized.

The more I started to watch this happen, I started to ask myself but also look out across the landscape of the gender dialogues that were happening at this time. The Women’s March happened around this time. There did seem to be an increased feminist identified response to Donald Trump and his first presidency, and I started to see also the word “white feminist” being kicked around on the internet as response pieces to these really declarative, very privileged women, either expressing a strategy or a need. But what I was struck by when I saw this was that nobody seemed to be operating from the same definition. So even me, as somebody who was trying to find one, I couldn’t. And I also wanted to not only answer that question for myself, but also to quantify and provide some historical context as to why there were a lot of women who did not feel comfortable at the women’s march. Why is that? That is a historical pattern that is not unique to that time period. That exact dynamic has happened again and again. So I came to white feminism, I think, from a very earnest place, but also I think that contextualizing a lot of what happened at that time and now continues to happen within history is imperative for actually understanding the mechanics of white feminism.

AA: Yeah, thank you for that intro. Maybe we’ll keep going with that and start talking about the book with the title and really nail down what that means. I’ll share a little bit more context for me. I actually remember where I was standing and the very moment that I heard the term “white feminism” and it was from my 15 year-old daughter. All three of my daughters have pushed me in such beautiful, glorious ways and introduced concepts to me that I’m so grateful for. I grew up in the LDS church and was married young, had kids super young, and kind of grew up my whole life in a bubble. So I was really, really late to feminism and had my own organic feminist awakening in my adult life, kind of like it had, you know, it was a hundred years ago, you know what I mean? The whole second wave of feminism missed my community completely. So I was discovering these things in real time as I had teenage daughters. And I remember it was in our family room and she was criticizing someone for displaying “white feminism,” and I felt a little bit of defensiveness just hearing that term. Because I was like, “Well wait, what does that mean? I’m white. There’s nothing I can do about being white.” And I was discovering feminism and this is like blowing my world open and this is so important to me, so I was like, “Oh no, what’s wrong with white feminism?” And of course I’ve learned a lot since then, but I wondered if you could speak to listeners who aren’t familiar with the term or may have heard it used in a negative sense, and they may be feeling similarly, either defensive or confused, and if you can highlight what that term specifically means.

KB: Mhm. And I want to also address that defensiveness that you felt from your daughter and hearing that term, I hope you know that’s not unique to you. There is, I think, a real reason that white feminism as an ideology and a practice evokes that from either practitioners or supporters or a variety of people who are feminist identified or not. I think a really good question, perhaps, for listeners is: why does white feminism get to you emotionally like that? What about that practice and that way of thinking has defenders feel like they might be discomforted by what they’re feeling, and therefore that must be the paramount of where the conversation goes or what have you. In terms of white feminism and how I define it, I define it very early in the book because I think it’s important for readers to know what I’m tracking. I think there’s a big difference between a white feminist and a feminist who happens to be white, and this is explored later in the book. For instance, and to be very clear, she blurbed my book, but Gloria Steinem, for instance, is not somebody who I would think of as being a white feminist just based on her politics, what she has prioritized throughout her activism, who she works with, what she’s tried to push for. However, white feminists love Gloria Steinem. That’s a complex relationship that I think she has spoken to throughout her career in very specific ways.

I define white feminism as an ideology and a practice. It can be followed by anybody. I cite a number of women of color who I think exhibit a very white feminist understanding. I define white feminism as a way of viewing gender equality that is anchored very deeply in capitalism, in labor exploitation, in greed, and obviously white supremacy. What I mean when I say that is gender equality within these harmful structures that already exist, so getting ahead within them as opposed to thinking critically against them. Which, for many other feminisms that I track in the book, just to give the reader some helpful contrast, Black feminists, Chicana feminists, a number of queer and trans movements, Native movements, obviously, fat politics, a lot of working class feminisms, a lot of disability justice activists, they are not necessarily looking to get ahead in what has been constructed in front of them. That is a main difference between white feminist ideology and literally everybody else.

When I’ve had to speak, I often say that when I was doing research for this book and really trying to analyze and break down how these different activists were thinking, and I had a number of white feminist thinkers who I was looking at and looking at a lot of their writings historically and now, a big consistency with white feminism is that they will often look to a woman in their community, whether it’s in their industry, in their workplace, in their neighborhood, at their kids school, white feminism looks at that singular woman and says, “How do we all be like her?” She has a well-funded home. She has a partner. She has kids and a functioning career. She’s able to bring in income to her family. She has all the markers of upward mobility. And many other feminist thoughts that I cite, when they are put in that exact scenario, the question they ask is, “How do we all have what she has? How do we all have access to clean water? How do we all have access to affordable housing? How do we all have access to healthcare? How are we food secure? How do we get access to education?” Things like that. So it’s a major point of divergence in thought.

Also, I document, and it was very important for me to show this in the book, a number of white women, mostly from the South, who were not white feminists in their politics. My favorite is Anne Braden, who is an incredible thinker and civil rights activist that I talk about a lot in the book, but there’s a lot you should read about her and the way that she thinks. And I think it says a lot that in her lifetime, she could not really find a place in the mainstream feminist movement because of her racial literacy and because of her devotion to civil rights. A lot of mainstream, what some people call second-wave feminist movements, would not be amenable to somebody like her, even though she was a white woman and she was from a “respectable” white Southern family. Her political world was not really amenable to those white feminist movements, and she’s not alone. There’s a documented history of these women and I think they’re really important for setting templates, specifically for white women who do not want to be white feminists in their politics.

AA: That’s fantastic. So clear and super helpful. I also wonder if you can share your brilliant analogy about a computer game or a video game. Can you share that really quickly? I think it’s so effective.

KB: Of course. What’s so funny is that hearing you say that, when I gave that initial talk, I didn’t plan that. That was just me. It was just my notes and putting it together and trying to condense something very quickly for an audience. But no, I will absolutely share it. So, if you think about the video game of patriarchy, let’s use that metaphor. There’s sexual harassment over here, there is the glass ceiling over here, there is the fact that once you enter a field you will most likely be paid less than your cis male coworkers. Then also consider the fact that as you continue to go along, if you decide to have a child, you will be hit with the motherhood penalty. The fact that wherever you work, there may not be paid parental leave, all of these obstacles that are very gendered. White feminism as an ideology and a practice encourages you to excel at the video game at whatever cost. For instance, if you are on an upward career track and you are able to get ahead in that career track, despite being in perhaps a workplace where you are disrespected or sexually harassed, the fact that you are the only woman who gets to sit at the table, a white feminist approach to your scenario and life is that you won. However, in the video game, you have to ask yourself, “Who did I exploit to get there?” Who are the undocumented workers who are perhaps cleaning up the office after all the white feminists leave and go home? Do they have union protection? Do they have healthcare? If they had an emergency with a family member or a child, would they be able to leave and still have their job secure to do that? What about the women who are potentially looking after your children so that you can be there? Who’s getting them from school? Who’s making their dinner? Who cleans your bathroom so that you don’t have to do that and you can go be in this fancy office? White feminism does not interrogate that or ask any of those questions.

white feminism looks at that singular woman and says, “How do we all be like her?”

White feminism historically and now has always been about personal gain, even if that cost is other women. And traditionally speaking, those other women are of color, they don’t make as much money as you, sometimes they’re immigrants, sometimes they’re queer and trans, sometimes they’re disabled, sometimes they do not have straight sized bodies. There are a lot of dynamics that go into who “wins,” and white feminism as an approach to gender equality has never really interrogated labor, has never really interrogated labor that is not economized. Any sort of childcare or domestic work, white feminism has never interrogated low wage labor. Anything that needs doing, any sort of junior people, even in a white collar office setting, white feminism is about winning at all costs.

AA: Whereas a more inclusive feminism would be about entering that video game, and instead of just trying to jump over the obstacles, not looking backwards or to the side to see how other people are experiencing the game, they’re trying to dismantle the obstacles for others, right?

KB: Yes, and dismantle the game.

AA: And dismantle the game.

KB: That is a thread that is through, again, Black feminist thought. It’s foundational to a lot of Native movements, it’s foundational to a lot of queer movements. This video game pits us against each other, it asks us to exploit each other, it incentivizes us to abuse each other, even from a privileged position. I use this example a lot, it’s like if you’re in a white collar setting, like a workplace, and let’s say you have been sexually harassed at your job. The white feminist response for a long time, and I document this in the book, is go straight to HR, negotiate something for yourself in terms of having messages that are inappropriate. Really going inward and thinking only of yourself and what you need to be protected in this company. However, statistically speaking, and I say this with the sort of post #MeToo data that has emerged, if you have been sexually harassed in your workplace, you’re probably not the only one, especially if you’re a woman. I’m sure there have been others that have come before you, and there are more that will come after you. That’s how abuse works in a lot of these powerful bodies. So, really, if you look outside of white feminism into other feminist thoughts, the more strategic response is I need to band together with other people who have experienced this and we will all collectively go up against this powerful body to challenge how we’re being treated because we’re women, because we’re of color, because we’re gender non-conforming, because we have a disability. There are a lot of examples of that that I cite. And the thing is, historically, it works.

AA: Okay, that’s so important and such a great analogy. I thought it was so, so helpful when I heard it. Thanks for sharing that. Okay, let’s dig into the book. I read the book about three years ago, maybe even a little more than that, and I’ve remembered so many specific parts of the book. We won’t have time to cover everything, and I do want listeners to go out and buy the book and read it yourselves, too. So we’ll just get the tip of the iceberg, but I wanted to start out with the relationship, dating all the way back to suffrage, between white feminism and brand partnerships. That was so interesting. So, if you could talk about the history of how those brand partnerships got started.

KB: Of course. And isn’t that fascinating? I genuinely, when I was researching white feminism, just to give listeners some context, I wanted to do this project in a very historically based way because I thought it would be important for people to see the long view. But also I was awarded a fellowship to do a lot of foundational research for this book. And when I found this exact anecdote I was so surprised, but also not, right? It’s so consistent!

AA: Yeah, that’s true.

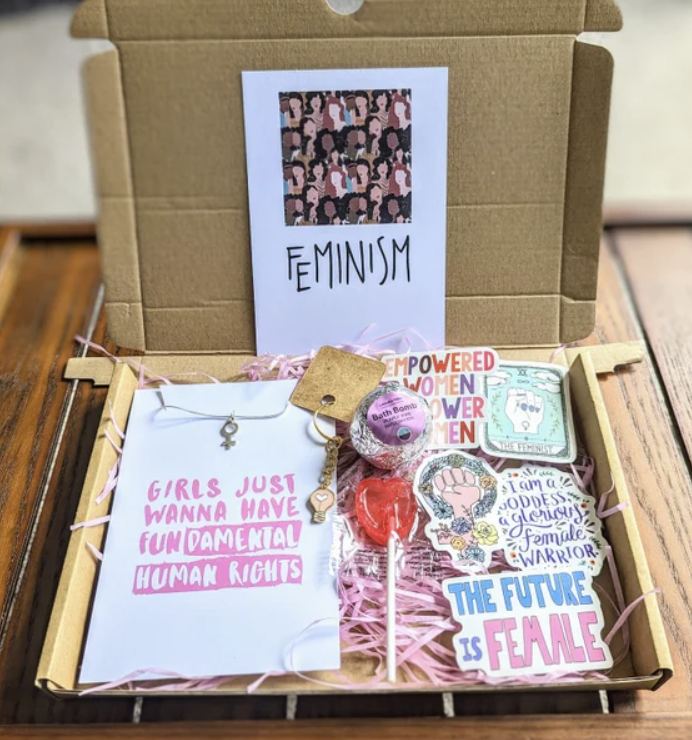

KB: I really thought that a lot of the sort of resistance wear was new to my time. There’s nothing new under the sun, right? So what we’re talking about, sorry for the long lead in, is that what some people call the first wave of, let’s say, white feminism specifically. So we’re thinking suffragists, Alice Paul, those people, if you’re more familiar, the women who wore the sashes with the bobbed haircuts who marched. I go into a lot of detail about them and particularly how they came together politically to envision a movement to obtain the right to vote for white women. And that was very specific, it was the right to vote for white women, and that’s a separate podcast. But specifically what you’re referencing is that this first wave of suffragists, they really wanted to, from a place of just strong marketing, wanted to get out in front of the public’s idea of what a suffragist is. There are a lot of parallels to this now, and especially what I was saying earlier in the episode about who a feminist is. They literally designed in-house images of a suffragist because this idea that a woman would speak publicly about her opinion, politics, things that she needs, things that she wants, that was not received well, and those women were denigrated, harassed, catcalled. The parallel I always draw is that it’s not really dissimilar to being a woman on social media now. If you have an opinion on something that is controversial or is challenging to your immediate community, whether that’s the neighborhood you live in or even the digital sphere that you’re operating in, you will be harassed and receive threats. And suffragists were coming up against the same dynamics.

So they designed in-house who this woman was, like who the American public was supposed to think of when they thought about a suffragist. And not surprisingly, they drafted this really homogenized type of woman who was young, she was white, she was skinny, she wore her hat a certain way to indicate class status. She was either a mother clutching a child, or this idea that she was your daughter and she wanted to be a mother at some point. Like, “Don’t worry, she’ll still get married, she’ll still have kids.” And a lot of this sort of respectability crafting went hand-in-hand with the brands you just spoke of. For one of the first big political demonstrations, one really well known suffrage organization partnered with Macy’s. And I found these incredible archives of, you know, like today or more like five years ago, “Nevertheless, she persisted” and these sweatshirts like “Feminist AF” and “Grab him by the–” fill in some other derogatory word, that’s not what was initially said. All of these like “feminist swag” white suffragists, and I use this word very pointedly, pioneered that practice with Macy’s in terms of pre-suffrage, you could walk past a Macy’s window and you could see a suffrage outfit. There were a lot of accessories and flags you could buy. And when you think about the desk accessories that have come out in just the last 10 years, it was really the 1920s version of that. Things you could buy that would communicate that you were for the right of white women to vote.

And for my work and my research, when I found that, and I found other instances of it as well, that’s the most direct example, but that particular lane of white suffragists were really game to partner with brands to get a political message out. And I consider that to be really foundational to how white feminism has continued to operate, even a hundred years later. And that, much like crafting this image of who the suffragist is, the type of woman you’re supposed to think of, white feminism made it very clear that they were looking to get in with power. They were looking to be pleasing to the eye. They weren’t trying to upset or challenge the idea of who a woman even is, who you’re supposed to think of when you think of these rights, you’re supposed to think of this person. You’re not supposed to think of really anyone else. And also really pushing this idea that you could buy your politics. That was really new in this particular time period. And part of the incentive was that because of the industrial revolution, middle class women were spending more and more time in department stores. They suddenly were going out to buy things for their families or themselves, so it was seen as a way to access women in a way that, say, in the late 1800s was not as pervasive.

So if you see a middle class woman who’s at the perfume counter, her eyes might drift to the right and she would see a suffrage flag and she could buy that for herself or her daughter. There were also, like I said earlier, suffrage outfits that you could buy that were front and center. And for white feminism, it really anchored this idea that politics could be transactional with money, particularly feminism. That you could buy one of these flags, just as you could buy one of these “Nevertheless, she persisted” t-shirts or “Feminist AF” mugs, and that in itself was a political action. And again, that is unique to white feminism. Other feminist ideologies are not out trying to either partner with Macy’s or even get you to buy to access feminism. I became very aware of that in my tenure in newsrooms, watching these very elite feminist spaces in the form of conferences or meet-and-greets and the fact that you have to pay all of this money to get in the door, whereas so many other forms of feminist thought work in public spaces very intentionally. This idea that you don’t pay for feminism, feminism is not a commercial that you watch and a good that you buy. But white feminism was really almost instructional in that and it’s carried through a hundred years later.

AA: Mm-hm. That was my next question for you, is how do we see it carrying through and how does kind of the business of feminism keep feminism white, even today?

KB: Mm-hm. Definitely through, whether it’s intentional or not– and I found out in a lot of my research that a lot of times it’s not. The idea that you need to pay for feminism automatically cuts out so many people. That’s what’s so powerful about libraries and parks and public spaces where you don’t have to buy something to be there. They are open to anybody, or at least anybody who lives in the neighboring community, which brings about bigger conversations about redlining and who lives where and who can even afford to live there. But asking for admission, asking you to buy something, asking you to have to pay to be in a place for many forms of thought, that in and of itself is not a feminist practice, right? It limits the class of who can be there, it limits the race of who can be there, it limits the gender identity, a lot of times, of who can be there. And that’s just to get in the door. We’re not even talking necessarily about buying additional goods or anything like that.

But again, this is where white feminism is so different in its executions and strategies because they, traditionally and today, are about the business of feminism. A lot of the retorts that you’ll hear when this has been critiqued is like, “Oh, but we’re a business. We have overhead, and we have to pay employees, and we need to be able to restore paint on the walls,” stuff like that. And that gets to the intersection of how white feminism operates, and that it is ultimately a business. And therefore, in 2015-16-17, you saw a lot of these “feminist businesses” ascending in the mainstream press and really being vocal about their “feminist politics.” And yet if you actually chipped away at any of this stuff or asked them anything about unions or labor politics, it was really obvious that a “feminist business” was actually just a business and that there wasn’t really much interrogation. And feminism was also a marketing strategy that was a way to position themselves much like the suffragists of a hundred years ago. It’s very consistent that it’s about optics. Which again, white feminism has always been very skilled. I think it’s because of the ingratiation with business and also marketing that optics have always been very important to white feminism and how it operates in terms of who’s in the front, who’s in the center. Again, drafting this sort of sketch in-house of who you’re supposed to think of. Other feminist thoughts do not do this.

AA: Mm-hm. You’ve touched on this already, but I want to dig a little deeper, partly for me, honestly, Koa, because I’ve read so much and am still learning so much. And we’ve talked about it on the podcast about intersections of patriarchy with, for example, white supremacy, we’ve talked about a lot and really addressed a lot on the podcast, intersections with homophobia. But one thing that comes up a lot is capitalism. In my Ph.D. program, in the books I read, even in other guests that I’ve had on the podcast, they’ll say, like, “the oppressive systems of patriarchy, white supremacy, heteronormativity or homophobia, and capitalism.” And we haven’t dug into the capitalism part as much yet as I would like to, so I’m wondering if you can take us to the next level deeper and talk about capitalism philosophically, kind of at a foundational level, because that’s something that I almost think of as being so baked in to how our country operates. I mean, as you just talked about just now, why is it exploitative? Why is it not compatible with the values of feminism? And can we even envision something else instead? This might be something that listeners are wondering, too.

KB: Yeah, I wholeheartedly, absolutely, you can envision something else. And there are so many thinkers I cite in my book, who have. And they have for years, this is not new information. These are not new writings. So many people across the feminist spectrum from different parts of the world, from different parts of our country, different races, have answered this question. And they have many theories, which I’ve included. In terms of how capitalism prohibits feminism, many thinkers before me have been very explicit and have almost done, I would argue, like the long division of this to show you how a profits-based landscape really limits our ability to fully respect and fully connect with each other. In that the biggest go-to, which I think is perhaps like the most accessible to people, is American slavery. This idea that an entire race of people who were taken from one continent and brought here and enslaved specifically for profits, limited and continues to limit an entire demographic from having any sort of equal rights or even equal standing in a society. And Angela Davis has spoken about this and written very extensively about how corrosive this is. To give you an example, of course there were well-intentioned white people in America at this time who looked over and thought that was wrong to denigrate and enslave people, to take their children away from them and sell them, to abuse them physically. And yet the justification at the time was, “But this makes so much money. How would we even begin to dismantle this? Because our entire society at present is built on this greed. So if these people are freed…” and these were arguments people made at the time.

The profits matrix, in a way, limits the imagination. And I see that now with a lot of other versions of exactly what we’re talking about, and even against feminist arguments that I’ve made, other thinkers have made, in terms of, for instance, paid parental leave on a federal level. Republicans have been saying for years that that’s too expensive, that it will not work for the cost analysis of this country to actually protect parents’ ability to fully care for and be present with children without worrying about earning an income as well. So, this continues to limit rights because in a profits-oriented landscape, profits will always come first. And in a lot of ways, money and greed, I have found in a lot of work that I have done, they can be more sinister in the sense that you can have a conversation with a body or bodies of people, even an institution, in which they will look you in the face and say, “Yes, we know this is wrong. We know it’s wrong that parents should be back here two weeks after giving birth. We know it’s wrong that you’re only going to get a week to care for your mother who just had a stroke. We know it’s wrong, but this is what makes money.” And it’s not really a surprise that misogyny, racism, ableism, all these things are deeply embedded in capitalism, because capitalism is about generating money above all else, so a lot of people who will not be recognized in that system as being “profitable,” whether it’s because of their assigned sex or because of their capabilities or because of their race or what have you, it will be justified because of money, and money works against disenfranchised people.

I’ll give you one more example, and this is in the book. A number of magazines that I used to work for, they were critiqued all the time for having really white, skinny, cis, straight women on their covers. The staffs knew this. This was not something that was new to bring to the table. And yet the defense from the much higher-ups was, again, a capitalistic response. It was like, “Well, white women sell the magazines. If we put a consistent number of Black women on the covers, our magazines would not sell.” So that was considered the justification to continue the racism in a lot of these workplaces. “Well, it’s not our fault, this is what people want to buy and we’re a business.” So a lot of these threads run not only in continuum, but are deeply braided together. And within white feminism specifically, that’s why it’s so head-scratchy that capitalism is so foundational to how they think about equality, because capitalism from the jump impoverishes and also denigrates so many people on a daily basis. Capitalism is not going to save us. But if you look back through a white feminist canon, as I have, they advocate that it will. They are very clear that what we all need to do is to go to Vassar and make a lot of money and have our two kids and live a very middle class existence. And the reason I think they’re able to be so wholeheartedly ardent in that theory is that, again, they just don’t consider people outside themselves. So again, the women who come and clean their home, the women who take care of their elders, any special needs kids that they have, even the teachers who don’t make very much who teach their kids in a public school, these people are not considered and they’re not seen.

This makes so much money. How would we even begin to dismantle this?

AA: Thank you for that. I’d like to now look at another group, and you’ve mentioned this already, but let’s dig deeper on this. Another group that white feminism leaves out, there’s a racial component, obviously, our definition to white feminism. You also talk about how white feminism excludes queer, transgender folks. So when we talk about white feminism, we’re really discussing cisgendered, heterosexual white feminism. What’s the history about how white feminism has excluded our queer siblings, and why is it set up this way?

KB: Well, there are a few ways, depending on where you want to operate from. I think it’s important to note that a number of queer organizations, for instance, that I’ve gone back in their archives and pulled notes and quoted a lot of their thinkers, these are, for instance, a number of radical lesbian feminist groups have historically been so exclusionary. I mean, exclusionary doesn’t even fit it, they denigrate trans women. They really do. And there’s a huge respectability politics there in terms of, again, these self-identified radical lesbian feminist thinkers were very forthcoming in that they didn’t want to be associated with trans women because trans women were not going to “pass” or going to achieve the type of visibility in society that in some ways they wanted. And this has continued to play out in the queer rights landscape. You see it now, there’s a number of spaces still to this day and there will continue to be more, unfortunately, in which trans women are not allowed into queer women’s spaces. All sorts of really complex politics there. But the really white feminist bedrock of that is, again, for these specific thinkers who I cite in the book, they’re seeing a pathway to acceptability. They’re seeing a pathway to basically be recognized and to have a certain right from a power holder that incentivizes them to distance themselves from trans people, historically, and that is a very white feminist principle. As radical and queer as they like to think that they are, that is a white feminist principle.

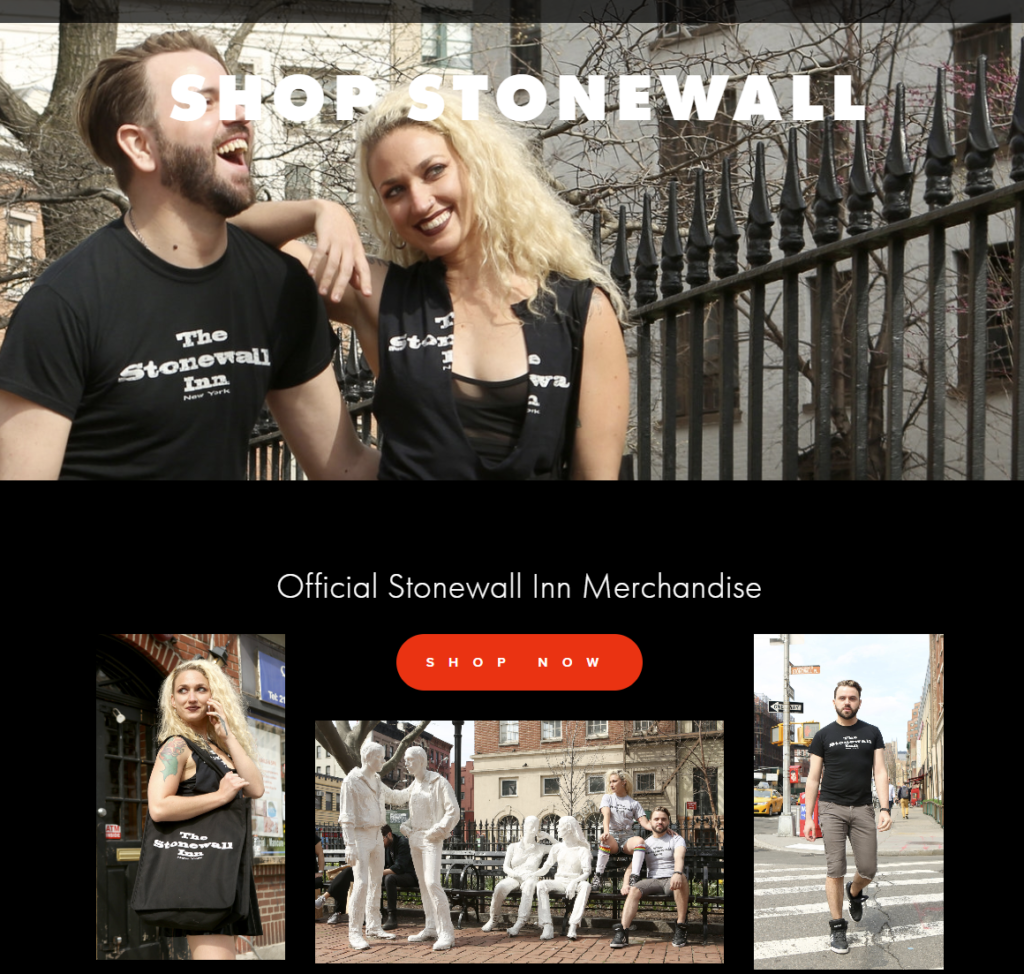

And you see versions of that now with J. K. Rowling, in a lot of her arguments that she makes, which are very white feminist, I’m talking, like, a script. I mean, you could do an entire white feminist book just on things that she has said publicly about trans people and especially trans women. So that’s one way in. Another way in that I document in the book is particularly with the Stonewall riots, for instance. If you’re unfamiliar, Stonewall is a very important historical queer bar that’s in New York. It has incredible history with not just the riots, but also in general. And there is a marked history within the space of that bar of more white, middle class queers really distancing themselves from the queer kids who perhaps ran away from a home, who were living on the streets, who were unhoused, who were from immigrant families, who, again, were not going to be in close proximity to this sort of bougie, gay, like Fire Island sort of life. And it continues to be a pattern in oppressed circles in which the oppressed figures out ways to oppress others. And unfortunately, queer and trans rights are a case study of that in terms of class and gender identity really scattering queer people, but also at the same point, being a platform for them to then disenfranchise others and say, “Well, they’re not like us and we are better because we are cisgendered” or “we are middle class” or “we do have access to these things because we’re cisgendered and we’re not complicating anybody’s ideas of who a woman is or who a man is, for that matter.”

So, it’s to be expected, unfortunately, it’s a pattern in history. But I think also it underscores a lot of how intersectional identities really frazzle the oppressors. Where, you know, somebody who shares a version of your experience but who is also Dominican and an immigrant and maybe also trans, therefore does not fit into this ascension towards whiteness and can’t for a variety of reasons, and therefore cannot be a part of what you’re envisioning. I think a big, important piece to understanding white feminism as white feminism, even across queer and trans movements, which, you know, are very multi-gendered, and are also arguably post-gender, is this aspiration to whiteness. That’s why I wanted to call it white feminism, as opposed to other people calling it like “bougie feminism” or “feminism lite” or “commercial feminism.” I think maintaining white feminism is very important because what you’re actually asking people to do, across marginalization, is to aspire to whiteness. And an immigrant trans woman in the Stonewall riots era cannot aspire to whiteness, and frankly, probably doesn’t want to. And therefore, the mainstream gay rights movement does not know what to do with her. And therefore, because she complicates a lot of their understanding of rights and rights specifically for queer people, she is to be denigrated. She is not to be included.

AA: Mm-hm. Wow. Again, hearing you talk about it is really crystallizing that theme, it is kind of amazing how each group, and it must just be human nature that we’re kind of focused on ourselves, but that we wake up to our own oppression and then don’t look around for how we’re still participating in that game that is suppressing other people. That’s just the theme again and again. I want to talk about a couple other things that you bring up in your book that, again, are not addressed in a lot of other works that I’ve found, Koa. And again, I just value your book so much. You talk about older women, you talk about ageism, and I’d love for you to talk about that for a minute, because that’s something, I mean, case in point, that older women are just invisiblized in our culture. Even within feminism, we just don’t talk about it often enough. Can you tell us more about that?

KB: Of course, and happily. And like you, I’ve been kind of disappointed to not see that elsewhere, because I feel like it’s such an obvious critique, especially with white feminism. But essentially, white feminism of 100 years ago and now, I document many examples, is extremely ageist in terms of who is centralized as the face of these movements, much like that image I talked about earlier of white suffragists drafting this woman in-house who you’re supposed to think of. She was always young. And that was intentional because you weren’t supposed to think of like old, disgruntled crones who were complaining, you’re supposed to think about young, attractive women who either could be your daughter or a nice, respectable middle class woman who lived in your neighborhood who you might see with her children. And again, that was a strategy on the white feminist part to not necessarily complicate who you were thinking about. They were playing to a bias that was already there. And even five, six years ago, maybe even more, when there was this white feminist discussion and concentration of the lean-in crowd, so a feminist is this corporate person who works really hard at a white collar job and answers lots of emails and is very productive. Again, that was always a young woman, like, 40 was pushing it.

AA: Haha, totally.

KB: She was generally around 27 years old and she played to a lot of ageist practices within marketing and media anyway. But again, white feminism isn’t rethinking these things, and you see this even in white feminist organizing. An example I cite is like, yes, reproductive health has always been central to a lot of white feminist organizing and also non-white feminist organizing. But if you look at other feminist thoughts, they’re also pushing for things that have to do with biological women that are post-menopause. They’re having to do with health, they’re having to do with the push for hysterectomies, they’re having to do with all sorts of things that happen when you’re assigned a female body that are currently not regarded by Western medicine or, frankly, healthcare in general. And yet, white feminism has always, always, always been very centralized in young women’s ability to get pregnant. And any efforts to either think beyond that or think more holistically or consider the health needs of women that aren’t of childbearing age anymore have been swatted away very politically. So it’s really, I would argue, a cornerstone of white feminism to both be very ageist in its optics in terms of, again, you’re supposed to think of this woman, but then also in their strategies, who they’re concerned about, who needs the most resources in the room, who will get resources and people to show up for her. It will be a young woman. It will not be a woman in her sixties who is a domestic worker and might need increased job protection so that she can be present with her grandchildren. These are very evident.

AA: Yeah, I’m just thinking of how we can change this culturally. This could be a whole episode on its own. But just to any listeners listening right now who are advanced in age, I would just say that I personally, and I’m in midlife now, I know how much it means to me, I’m so grateful anytime I see women in their later years who own the way they look, that walk around and participate in conversation, that put themselves out there publicly. And I know there’s a lot of pressure to not, there’s a pressure to just be quiet and kind of fade into the background. So I just want to say for anyone who’s listening, please, we appreciate it so much when you are authentically who you are, when you aren’t afraid to look your age and to lead and try to change that for our generation and then our daughters who are growing up too, to be excited about growing older and excited about participating in the public conversation and having a role. So systemically, but I also see, I just look at my mom and my mother in law, for example, and just the way they feel this pressure to shrink and be embarrassed about even looking older. And I just want us to fight back against that.

KB: Well, and that’s a patriarchal concept–

AA: A hundred percent.

KB: –That white feminism has internalized and then built again into the groundwork that you are not of childbearing age and therefore are irrelevant. I don’t want to look at you, you don’t bring me any sort of erotic pleasure, and therefore you shouldn’t exist. These are patriarchal concepts, a hundred percent.

AA: Yeah, that then women perpetuate and participate in. Listeners, there are so many other topics in this book. I will mention this one, and we’re not going to talk about it, Koa, but the first time I really read data about the missing and murdered Indigenous women was in your book. We’ve since covered it on the podcast, we’ve had Native scholars on to cover it elsewhere, and we have a YouTube episode on it, but I just want to say that that’s a part of your book that moved me, I had to set the book down and put my head down and cry while reading that chapter. I was very, very grateful that you included it. It kind of planted a seed that then became an area of focus for me academically and personally. So, thank you for that. But the last thing I’d like to ask you as we wrap up the episode is about your pillars. Your pillars of change, which I really loved. I don’t want to, again, have too many spoilers, but for everyone who hasn’t read the book yet, could you share a couple of those pillars so that we can end on action items that people can take into our real lives?

KB: Would it be helpful for you if I actually read the pillars, or do you want me to just condense it?

AA: Sure! Either way.

white feminism has internalized and then built again into the groundwork that you are not of childbearing age and therefore are irrelevant

KB: Okay. Yes, I do have very actionable items in the book that I hope are not just checklist items, like these aren’t things you post and then you’re done. These are things to take with you in your life and your activism, the way you think about other people, the way you think about public spaces, the way you think about media conversations. I would like to think that what I am leaving you with and what I’m asking you to think about are things that you can take with you many years from now, and also continue to apply in how you go to your job, how you think about organization, both if there is a circumstance that comes down in your job that is unfair and inhumane for a number of people who you work with. In the last part of the book, I cite that the first pillar of change is basically to stop acknowledging privilege, but to fight for visibility instead. What I mean when I say that, and again, there’s a whole chapter to give you proper context, is that I have found a lot, not just in my research and the type of writing I do, but even in feminist identified environments that I’ve passed through, worked in, volunteered for. I’ve noticed this consistent pattern in which a cisgendered woman who’s from a middle class home, who went to a lovely private school, will tell me and other women who are present that she’s so privileged and she’s aware of that. And it’s almost like a non-starting point, the way it’s consistently presented. I mean this both in meetings I’ve been in professionally, it’s like she’s aware that she’s privileged and you don’t need to remind her and the conversation stops there. She’s aware and she is therefore inoculated against any sort of further critique, or even, I would argue, strategic accounts for that.

So it’s like, okay, you’re the head organizer for this project we’re working on, you’re very privileged, which you’ve said eight times, how do we maybe rethink this project so that you’re not leading it unilaterally? Can we get some sort of complimentary voices? But I have found that in my life, and then when I’ve gone back through history and archives and different women speaking, this is a pattern of saying that, yes, you come from this background, you got to go to college, and that is the beginning and end. Whereas if you’re actually talking about something that’s constructive, that’s the beginning of the conversation. That is an open door to people who don’t share your background to then either join you in discussion or join you in effort. But I’ve witnessed, and I analyze this in the book further, if you’re curious, I’ve witnessed these instances where that is actually used as a way to maintain power, it’s not really used as an idea to question it. So when I make a reference towards visibility, it’s like, I’m not really interested, nor would many of the other thinkers I cite be interested in the fact that you’re so privileged, or I’m so privileged, or our neighbor is so privileged. How can we rethink this so that people who are not can actually participate in the panel discussion, the fundraising effort, the PTA meeting, the soup drive, the political campaign, the union efforts that are happening at our job? That’s what I mean.

The second pillar of change that I’m very adamant about is fighting the systems that hold marginalized genders back. And what I mean when I say this, and again, I go into a lot more detail about it in the book, is that I’m not an advocate for, nor have I ever been, of when one person who’s very public says something that is extremely racist or deeply misogynistic or whatever, and then the internet spends like 48 hours denigrating that person. I don’t really find that to be helpful, especially if you’re looking at this as, you know, that person was a part of a system probably that treats people that way. But a lot of the powerful bodies that I analyze in the book, whether we’re talking about studios or government bodies or tech companies, a lot of times they will position that singular person as the problem. For instance, “We fired that person. This isn’t going to be an issue anymore because we fired that one person.” A lot of these companies, from a PR standpoint, rely on a “fall guy,” and it’s a way to minimize a problem and then make a problem go away in the press.

But politically speaking, one person, even a very high-up person who’s extremely powerful, they are part of a system or a culture or a company that facilitated this on a broad level. I talk about in the book how some of the best reporting I remember reading at the height of #MeToo was the reporting that obviously detailed an abuser who has a lot of influence, a lot of money, who violates people, but the best reporting I felt analyzed in detail the layers in these companies or organizational bodies of assistance, admin, executive leadership, all these layers that knew and facilitated this abuse on a structural level. So, consumer activism has its place. I don’t purchase a number of things from people who I think have really horrible politics, and that is my right as a consumer. Consumer activism has a very important feminist legacy in the United States, but that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about harassment, which is very different and I don’t feel like it ultimately achieves a lot of these goals. I think it’s important to think in terms of these systems rather than this individual person. It’s much more holistic, but also just gives a more accurate portrayal of abuse and harassment and low pay and exploitation, and ways in which you can challenge those with a group. If a lot of people in your company who are not white are not making a certain amount of money, being able to organize with a union to challenge that system in that way of thinking in your workplace is much more effective and also ensures a lot for the people who are going to come after you. A lot of political organizing, I find, is a lot of legacy work. Thinking a lot not just of you sitting there with your colleagues. What about the people who are going to be at this company or this place in five years? What about the people who are interning, setting precedents, things like that? Thinking in terms of systems and not so much individual people for lasting change.

And then my last pillar of change that I advocate for is holding women accountable for abuse. A big dimension of white feminism and a line of thinking and a talking point that really protects and upholds white feminism as an ideology and a practice is this idea that I’m sure you and your listeners have heard versions of this before, like, “Well, I’m not doing anything that men don’t do.”

AA: Oh boy.

KB: I’ve heard this a lot in my life, to basically defend ambition or ostensibly greed, to be honest. And there are so many examples through history that I found, even if you think about the summer of 2020, when a lot of very prominent women were asked to leave companies based on abusing their employees. Not conceiving of gender is necessarily being preventative against abuse. There are so many examples of women abusing other women and exploiting other women to a really personal end. And being very clear headed about that, I think can really make activism, and also just political organizing, much more robust in terms of how you’re thinking about power in the first place and what a person in power is able to do to another human being. So, understanding that not only are women capable of this, but again, the capitalistic structure is such that if a particular person from a specific background happens to have this role, that might not necessarily mean much for the entry-level employees, for the interns, for the assistants, for the people who do a lot of low wage work. It’s really the structure of power that is inhumane, and that is permissive, and that allows people to be treated so poorly, regardless of the identity of the person who is sitting up there.

AA: Yes. Yes. Hear, hear. Well, that was fantastic. And again, I just want to thank you so much, Koa Beck, for being here today. Lastly, before we sign off, I’d just love for you to tell listeners where we can find your work, if you have a social media handle and any place that we can find all the stuff that you’re doing.

KB: Sure. So I do have some social media, albeit as much as I care to have. I have an X account that I’m admittedly not very active on anymore these days. I post a fair amount to Instagram, and that’s just my name @koabeck, and I have a Threads account too. There’s a Koa Beck author page on Facebook that, again, I’m a lot more removed on. But you can also be very vintage and you can come to my website.

AA: Very vintage, I love it.

KB: Haha, koabeck.com. I like to keep a lot of my writing in one place that’s really centralized for people to find. So you can find things that I’ve written there and then also other interviews that I’ve done if you’re interested in these talking points or anything else. I’m also somebody that likes to step away for long periods of time to work on other things, so you might not be able to access me that immediately, but I think that’s for the best.

AA: Yeah, for sure. That’s a great example of healthy living. Again, for listeners, the book title is White Feminism: From Suffragettes to Influencers and Who They Leave Behind.

KB: Thank you so much. And I also want to share with your listeners, I am a big proponent of public libraries. It’s because of public libraries that I got to do a lot of this incredible research, so you can get White Feminism at the library, I empower you to do that. Also, if you are not a big reader or if you have any sort of neurodivergence, I read the audiobook as well. I am a relatively new mother, so I’m really getting more into audiobooks these days so I can keep abreast with my interests. And I loved working on the audiobook, I had never really done anything like that before. So, I always encourage people to access the book that way if it’s more realistic.

AA: I’m glad you mentioned that. I actually listened to the second half of it. I read the first half and then for the second half, I think I was just driving a lot during that time and I listened and it was fabulous. You did a great job. Yeah, I’m glad you mentioned it.

KB: Thank you!

AA: And again, thanks so much for being here, Koa. I learned so much from you.

KB: Oh, thank you so much for the invitation.

stop acknowledging privilege

fight for visibility instead.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!