“I ended up face to face with a conflict between my sexual identity and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders”

Dr. Nanette Gartrell and Dr. Dee Mosbacher have been pioneers in the struggle for LGBTQIA+ civil rights for over forty years, contributing essential research, political action, and groundbreaking documentaries on gay and lesbian experiences. On today’s episode, I’m honored to sit down with these personal heroes for a conversation about their lives, their activism, and their love.

Our Guests

Nanette Gartrell

Nanette Gartrell, M.D., is a Visiting Distinguished Scholar at the Williams Institute and holds a Guest Appointment at the University of Amsterdam. Previously on the faculties at Harvard and UCSF medical schools, she is the principal investigator of the U.S. National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study (NLLFS), which since the 1980s has been following a cohort of planned lesbian families with children conceived through donor insemination. She has published extensively on this topic, including in the New England Journal of Medicine. Her investigations provide information to specialists in healthcare, family services, education, and public policy on matters pertaining to sexual minority parent families. Dr. Gartrell graduated from Stanford University (B.A.), University of California (M.D.), and completed a psychiatry residency and fellowship at Harvard Medical School.

Dee Mosbacher

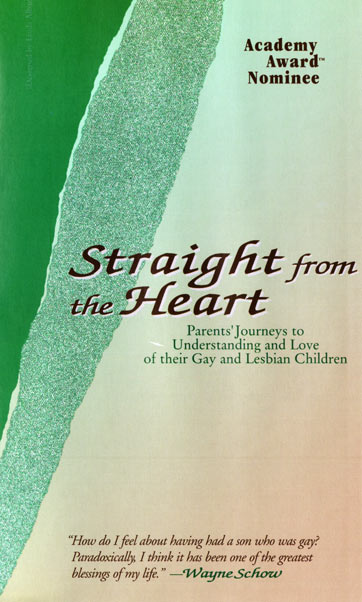

Dee Mosbacher, M.D., Ph.D., is a psychiatrist and documentary filmmaker. She was a producer/director of the Academy Award-nominated “Straight from the Heart” and eight other award-winning documentaries. As a public sector psychiatrist, Dr. Mosbacher specialized in the treatment of the severely mentally ill, including many who were homeless. Dr. Mosbacher served as San Mateo County’s Medical Director for Mental Health, on the board of California Pacific Medical Center, and on the faculty at UCSF. She has received many awards, including a NOW Women of Power Award and a John E. Fryer Award from the American Psychiatric Association.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Nanette, you have such an impressive bio, such an amazing life that you’ve lived; I’m really excited to have you tell us a little bit more about what it felt like from beginning to end. Can you start with your background? Where you grew up, and your family and education? Help us get to know you a little.

Nanette Gartrell: Sure. I was born and raised in Santa Barbara, California USA. I was the oldest of three children. Sadly, both of my parents suffered from significant mental illness, which created major emotional struggles for all of us and also economic hardship for our family as a result. Although my parents hoped that I would stay in Santa Barbara to take care of them and be close to them, it had already been a crushing responsibility when I was a teenager and I felt that really, in order to survive, I needed to move out and be in another city once I finished high school. So I realized —I think I was about 11 years old — that my ticket out of there was to be very successful academically and ultimately earn a full academic scholarship to college in another city, and I set my sights on Stanford and I worked very hard and got in.

AA: Amazing. Wow. When you got to Stanford, did you know what you wanted to study already? And were you there on scholarship? Did you have to work while you were in school? What was that chapter like?

NG: Well, I think neither I nor my parents at the time were politically conservative. I mean, many people were politically conservative back then, but neither I nor they could have predicted my future career path when they dropped me off to begin my pre-med studies in the Fall of 1967. However, within a couple months I fell in love with a woman, I came out as lesbian, and I ended up face to face with a conflict between my sexual identity and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (which is the handbook of diagnoses that all mental health professionals use and its abbreviated DSM).

I was aiming for a career as a psychiatrist, probably not surprisingly having grown up in a family with some significant mental illness because I wanted to understand it better. But according to the DSM, I was mentally ill. According to our legal system, I was a criminal and according to the faith community, a sinner. Yet somehow there I was at 18 years of age, I was convinced that these entities had it all wrong and I set out to do something about it.

So, I was there on a full academic scholarship. I did have to work as well to have spending money, of course. And after coming out I went to the medical library and I wanted to see what I could find about LGBTQ people. There was practically nothing there that was not focused on sexual minority people who were in psychiatric hospitals or prisons. Finding that out gave me a mission: I decided that I would become a researcher with a goal of learning how to conduct scientific investigations that would provide a much more accurate picture of LGBTQ people than observations of psychiatric inpatients or prison inmates who were forced into experiments that were attempting to change their sexual orientation to heterosexual.

I was very fortunate that human biology was created as an undergraduate major in 1970. Especially, because I hadn’t been able to decide what to major in and I made it all the way to my senior year without a major, and they didn’t catch me! One of the requirements was to conduct an internship under a faculty member. I approached Dr. Keith Brodie, who was then an assistant professor of psychiatry who had recently been hired from NIH (National Institutes of Health) to see if he would be willing to have a student working under him. He agreed and he became my mentor, and he began to teach me how to do research. Little did I know then that he would later become president of the American Psychiatric Association and then later still, president of Duke University.

One of the things that was a huge surprise was that he was delighted to find out that I was a lesbian who wanted to do research on LGBTQ people. This was an era at Stanford where people weren’t talking about it very much, and the way they were talking about it was in quite homophobic terms. So in 1971, under his auspices, I designed my first research project, which was a survey of psychiatrists’ attitudes concerning lesbianism, and then basically launched, from there, my research career.

AA: That’s incredible. I’m just astounded that you had the confidence, first of all, to be able to come out as soon as you realized that you were a lesbian in that environment. It was, you know, between ‘67 and ‘72, I guess. Tell me a little bit more about that Nanette, and the homophobia that you encountered at Stanford as you were heading into grad school. Can you talk about that a bit?

NG: Sure. The process of coming out for me was very similar to that of many people, which was figuring out who it was safe to tell first, telling those people, going through the process of dealing with their reactions—some of which were okay, some were shocked, some well…the more people I told, the more I heard things like, well, you just couldn’t possibly know if you haven’t had a relationship with a man that you are lesbian. And from my perspective, I had known that I was attracted to girls from the time I was three years old. My attractions were to my peers, same age peers, and those attractions grew up as I grew up. And so it just wasn’t a surprise to me.

It felt very central to who I am. And the process of telling other people was really about finding those who had their reactions either positive or negative, and then could get past them and see me for the same person that they knew before with just different information about whom I was attracted to. And also finding others who were just frankly homophobic and awful and very sexist, and dealing with the pain of that. It hurts anybody who goes through that process.

AA: Mhmm, I can imagine. So it’s also just amazing that you were able to work with Dr. Brodie. I mean, what an amazing opportunity. And it sounds like he was a pioneer in the field as well, is that right?

NG: He certainly was a rockstar very rapidly. I mean, he was teaching us neuroscience. His lectures were on neurosciences and human biology and I just found it fascinating. And so that was the reason that I chose him, but he was really a very, very junior person who had been hired by Stanford, and then he just shot from there into the stratosphere in the field.

But the truly amazing thing was that I think he was really in a very tiny minority of people to whom I came out in that era who was just completely fine. I mean, not only was he completely fine, he was thrilled because he thought, oh, wow, here’s an opportunity for somebody to do research who knows something about this community, because we need this kind of research. And this was before homosexuality was taken out of the DSM, so I was considered mentally ill, and it was already well known that that was not based on any science. It was based on bias and very antiquated beliefs that were religious and legal precedent, then the Psychiatric Association packaging that all up and calling it a mental illness. I’ll never forget the moment that he said, that’s fantastic. Oh my gosh, you can study this group of people from the perspective of being an insider.

….after coming out I went to the medical library and I wanted to see what I could find about LGBTQ people. There was practically nothing there that was not focused on sexual minority people who were in psychiatric hospitals or prisons

I’ll jump way ahead to just say that it’s so curious to me at this stage of my life, when I’m 73 years of age, still doing research, that people say to me Well, aren’t you biased, studying LGBTQ people. I have a lot of responses to that these days, but one of them is, So you’re saying that nobody who’s a parent should ever study children? I mean, there’s just so many groups; nobody who’s a member of any group can study other members of that group? I mean, really not much research could be done if that were the case.

AA: Absolutely. Okay, if I’m recalling correctly, you didn’t have a similarly fantastic experience after you left Stanford and you were applying, I believe, for psychiatric residency at Columbia. Can you tell us what happened there?

NG: Yes. Well one of the biggest opponents of taking homosexuality out of the DSM for a period of time was Dr. Robert Spitzer. When in 1974 I applied for psychiatric residency at Columbia, I thought I really wanted to go to the big cities, and I’d never been to New York so I applied at Columbia. I applied at Duke because Dr. Brodie was there and he said, you’ve got to apply because you’ll love it here. It really wasn’t where I wanted to go. And [I also applied at] Harvard because Harvard was also a big city.

So my interview at Columbia; they assigned me to Dr. Spitzer, who was for most of his life a prominent advocate for reparative therapy to “cure” homosexuality. But right before that he had agreed to removing homosexuality in part from the DSM through a lot of pressure from advocacy groups and a lot of other psychiatrists who had been investigating the whole topic and thinking about it very carefully and scientifically. When I went in for my interview, he just hammered me with questions about my sexuality.

There was nothing about me walking in the room…I didn’t have a t-shirt that said ‘I Am A Lesbian’ on it. I dressed appropriately for the interview; I had a skirt on, and I had very long hair and stuff. But he just hammered me with questions about my sexuality, which he got to by virtue of the fact that I’d done the research that I’d done, and he deduced that I had an interest in it and probably a personal interest. And then asked, literally.

Other than saying, Yes, I am a lesbian, I refused to answer his questions because they were very, very homophobic. They were invasive questions about my sexual behavior, for instance, and roles, his assumed assumptions about roles that I and my lover had in our relationships and so on that were very biased and homophobic.

The chair of the department had already told me that I was going to be accepted in the program because I had led these research projects as an undergraduate, which was very rare then (it’s very common now because all kids who go into these very elite schools have a lot of accomplishments, but back then it was very rare). Then it turned out that he blocked my admission because I refused to see my lesbianism as a problem.

Dr. Brodie actually knew the chair of the department and asked him after I got my rejection letter, Hey, what happened with Nanette and you? She told me you said she was going to be admitted. And they, they said, well, she just doesn’t see her lesbianism as a problem. So I ended up at Harvard, where I was for the next 11 years.

AA: Wow. That’s unbelievable. I mean, you could sue them now, right?

NG: Who knows? You could try, I’m sure.

AA: I guess it makes me…it does make me feel grateful. I suppose that things have changed because when you tell the story that way, I am so appalled and heartbroken and I’m grateful that something that explicit—I know people encounter all kinds of bias and microaggressions, but to deny your admission and be unapologetic about it is really unbelievable.

So you ended up at Harvard, now it was around this time that you met Dee, right?

NG: Yes.

AA: Should we take a side road and talk about the relationship? Maybe you can both talk about how you met.

NG: Sure. I’ll start because my path to meeting Dee was a little longer than hers to meeting me. Or at least I knew much more about her before I met her than she did about me. We met in 1975, the year before I began my residency at Harvard. I moved to Washington DC to do an externship at National Institutes of Health (NIH) and I found a place to live in a house with a group of lesbians I’d never met.

I had a friend who was from DC and I wrote her a letter in the US postal service and asked if she knew of any place that I might live while I was there. And she found this place for me and I was ecstatic because I was going to be moving into this sort of lesbian collective household.

I drove my little VW bug across the country, and when I arrived Dee was out of town and my new roommates asked if I’d pick her up from the airport and I asked them how I would recognize her. Now, these were the days before airport security, when you could just walk into an airport and wait at the gate for people with signs and balloons and all that sort of stuff. And what they did is they pulled out a record album, the album of a lesbian singer-songwriter, that had a photo on the cover of the local lesbian softball team on it, and they pointed out Dee who was the team’s manager. It was about an inch by an inch, but that was the person I was supposed to go meet at the airport.

I tried to sort of memorize the picture and when her plane landed from Texas off walks this woman with frosted blonde hair and a dazzling smile, and that turned out to be Dee.

AA: Wow.

Dee Mosbacher: And the rest, as they say, is herstory. We fell in love, and we’ve been happily together for 47 years. We’re the only couple we know of though who moved in together before we’d even met.

AA: That is amazing!

DM: Whenever we could, we legalized our relationship; first through domestic partnership, and then through marriage in 2004. We were married an hour after the first same sex marriage ceremony was performed for Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon at San Francisco City Hall.

When the Supreme Court of California annulled these marriages, we married again the following year in Victoria, British Columbia.

AA: My goodness. And that one stuck. Is that right?

DM: Oh that one stuck for sure. That one stuck.

AA: That’s so beautiful. I have a couple more questions about that—were you supported by family and friends when you announced that you were dating or that you were going to get married?

DM: We didn’t have any family members at the wedding. In retrospect, I think they were kind of upset about that, but we had an hour to do it.

NG: Yeah. When we got the call that Del and Phyllis had been married at city hall, I had just been playing tennis and Dee, I don’t remember what you’d been doing. You told me, and we just went, let’s go because they might shut it down. We just jumped in the car. I had my tennis sweats on, I only had one little pinky ring on, so I didn’t have jewelry even to exchange or anything. We just ran down there to do it.

DM: That is true. It was very spontaneous.

AA: How long had you been dating at that point and wanting to get married and had not been able to because it wasn’t legal?

We’d been together by then 29 years, but before that there were other steps along the way. We were able to register as domestic partners in the 1990s. In any way that we could, we tried to legalize our relationship and certainly did very complicated wills that took into account the fact that we weren’t legally married because we couldn’t be.

Most LGBTQ people in partnerships, with or without children, who wanted to have a legal relationship that would withstand whatever might be coming at us, paid for legal services to get ourselves as solidified as possible legally.

AA: You really love each other. That’s really beautiful. And if I can throw in something personal too—I know I told you this and my listeners know about the faith tradition that I grew up in—I told Nanette and Dee on the trip that when I noticed them holding hands and I thought, oh, they’re a couple because some people were there (I was there with a friend on the study trip and there were various relationships on the trip or some people were just there by themselves) and I thought, oh, they’re a couple. I just noticed how affectionate and joyful your relationship was, and it was so beautiful to see it.

I really reflected that growing up in the Mormon community…and of course other religious communities too that really suppress and push underground same-sex partnerships, how devastating it is for the partners involved. And hearing your story, my heart’s breaking that you weren’t able to get married when you found the love of your life.

Also how it impoverishes that community because they don’t know. They can go through their whole lives, heterosexual people, cisgender people can sometimes go their whole lives not knowing that people they know and love are gay if those partners aren’t able to hold hands in public, to kiss each other in public, to let alone get married and have a beautiful celebration of their love. It just impoverishes everyone and harms those people so very much. It’s kind of this tragedy just below the surface and I guess my point in saying that is thank you for living your authentic, beautiful life out loud, like all human beings should have the right to do. For someone who grew up in a very conservative community…that’s still new to me to be able to see that. And I have people I love very, very much who are LGBTQIA+ and to be able to see you on—I was going to say the cutting edge, which sounds maybe silly to you living in San Francisco, but in Utah it is still the cutting edge of people living their authentic lives out loud. So thank you so much for the example.

NG: Thank you very much.

DM: That’s really kind of you, and we do know that we’re very privileged to live in a bubble, but it’s always been clear to both of us, I think, the importance of knowing someone in your family constellation, in your friendship constellation, anywhere in your community, who is out because it makes a difference. It brings it to such a human level.

I remember when Ellen came out and that started happening on television. That even that was something that was really wonderful and I think an effective way to start encouraging other people to come out. We’ve always known that’s such an important piece is to be able to be visible.

AA: That’s beautiful and courageous, so thank you. Jumping back to your career path, Nanette, I wanted to ask you about a really important research project that you did. I’m wondering if you can tell us about the US National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study?

NG: Yes. In 1986, this is a study that I launched. The word ‘longitudinal’ is in the study title and it indeed has been longitudinal, it’s still going on. I began the study at a time when lesbian mothers were losing custody of their children because judges believed that growing up with sexual minority parents would be harmful. So they were removing custody from lesbians who had conceived children in heterosexual relationships or marriages. The parents were divorcing, and the mothers were losing custody because it was assumed that the children would be harmed.

I realized that we really needed data, longitudinal data, especially because the judges in their imminent wisdom were saying that, yes, there are a couple studies that show that kids who have been raised in lesbian homes or being raised in lesbian households seem to be doing okay, but they’re young and we have no idea how they’re going to be when they’re 25 and 30 years old.

25-30 years, that was a long time, but I had a lot of energy because I was young. I thought, well, we can do that. We’ll just start. Our study is the largest, longest running investigation of sexual minority parent families in the world. We still have 92% of the families participating after all these years. In very brief summary, I can say that the kids are doing just fine. We’ve been following them since conception and they’re now in their early thirties and the findings have been a resource for people really all over the world. And they were instrumental in the American Academy of Pediatrics endorsing same-sex marriage, and also they were filed in numerous briefs with the Supreme Court in support of Marriage Equality.

I have a fabulous research team; it’s an international research team. I’m just very, very privileged to be working with the top scholars, and I’m so grateful to our participants who have stuck with us through thick and thin and are still with us today.

it’s always been clear to both of us…the importance of knowing someone in your family constellation, in your friendship constellation, anywhere in your community, who is out because it makes a difference

AA: Amazing. I have to throw in another personal comment there—my listeners will remember that I talked on one episode about Prop 8 when we were living in California and we were hearing just so many, very loud voices telling us to oppose same-sex marriage and my husband and I were talking about it all the time. And Andy Dunn (our dear friend from Stanford, who’s been on the podcast) I remember him coming over to our house and we had heard from everyone we knew that the reason that that same-sex couples couldn’t get married is because it was bad for children. It was destructive to the family. And Andy Dunn…I remember what I was wearing, where I was sitting, I remember him sitting there in our family room and saying, I just read this study on the children of lesbian couples and actually it seems like they fare really well. They fare sometimes even better than children of heterosexual families. That was the only data point that I heard on the other side and it stuck with me and I’ve remembered it ever since. And I’ve thought I need to read that study, so then when I read that was you, that’s really amazing! It was slow for my husband and me—my listeners know this, I’ve talked about this a lot—the process of deconstructing everything that we had been taught prior, but your study made a difference in my life. It was a little seed that got planted. It gave credence and validity to this opposite side that I wasn’t getting exposure to and it made a difference.

NG: Thank you. Thank you for telling me. Thank you.

AA: Nanette, okay you’re not averse to tackling tough issues because one of the next things I wanted to ask you about was: you are leading investigations into sexual misconduct by physicians. Can you tell us about that?

NG: Yes, I can. One of the things I think that’s characteristic of the research that I’ve done is that I only tackle the tough topics, especially at the time that I begin the studies. The more opposition to the project that I want to undertake, that I encounter, the more motivated I become to do it and the higher the walls in my way, the more motivated I am to carry on. Also that means I’m never bored with what I do because there’s so many people often trying to stop me from doing what I’m doing.

When I was a young Harvard professor, I was appointed to lead the National Committee on Women of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and I was responsible for advocating women’s mental health issues nationally in that role. I soon learned that there were many, many malpractice claims being filed against psychiatrists for sexual misconduct, primarily between male psychiatrists and female patients. And so I spent with my colleagues about two years trying to get the APA to let us investigate the problem, officially gather data about it so we could do something about it, because you can’t ever do anything in an institution like the APA without data, but we were stonewalled.

And so we gave them a deadline and they still stonewalled us. And so I gathered some Harvard colleagues together and I led a series of investigations that resulted in over a dozen scientific publications, documenting sexual abuse of patients by psychiatrists, by psychiatric residents, and by physicians in other specialties. Ultimately based on our research, in part, the American Psychiatric Association and American Medical Association amended their ethics codes to rule sexual conduct with current or former patients unacceptable. And that was a huge change. It’s also a felony in many states now, which is also a huge change. As you can probably imagine it still happens, but not as frequently as before.

AA: Wow. Amazing. Well, again, I’m just astounded and so grateful. A lot of times, like I mentioned before, we learn about how bad things used to be, and then we think, oh, good, it’s better. And so often we don’t hear the stories of how the battering ram knocked down the door of the fortress and this is why I introduced you both as being heroes, because that’s often thankless work. You do it. And then everyone’s like, great and then moves on. They don’t realize how hard it is to get those things changed. So kudos and congratulations to you and gratitude to you.

One more thing I wanted to ask about is on the home front, you and Dee both volunteered as psychiatrists treating chronically, mentally ill people in San Francisco, specifically in the Tenderloin district, which is a part of San Francisco that really struggles with poverty and people with mental health struggles and all kinds of difficulties. I’d love you to say something about that if you can.

DM: Yeah. It really breaks our hearts to witness the suffering of homeless folks, especially knowing that so many suffer from chronic mental illness. I think that not addressing this properly is one of the most heartbreaking failings of our country. As we witnessed this phenomenon in San Francisco and really all over the country, one day it dawned on me that we had unique skills to offer. We connected with a woman who had gone out under the bridges and into the camps to feed people, and then tried to bring people inside to see if she could help them get social services. We started volunteering at a place she created in the Tenderloin, not a clinic, just a space. And for the next 13 years, until it closed, we evaluated and provided psychiatric medication to anyone who showed up on Tuesday nights. To our knowledge, we were the only psychiatrists in San Francisco who were volunteering this way.

AA: Wow. That’s really beautiful. I mean, I imagine that would’ve been a really difficult, but really moving experience. Well, thank you so much Nanette, for sharing your story and feel free to jump in as we shift gears, but I’d like to now start at the beginning with Dee.

Again, I’m just astounded at what you’ve accomplished so far in your life. I’ll throw in here too, that I was able to watch one of the films that you made and was deeply moved and I’m hoping we can talk about it a little bit later on. But let’s have you start at the very beginning too and tell us about your family of origin and some relevant details about growing up.

DM: Well, as you mentioned, I was born and raised in Houston, Texas. My parents were Robert and Jane Pennybacker-Mosbacher. My father was an oil producer and my mother was a stay-at-home mom. I think it’s really important, Amy, to acknowledge class, which is such a profound determinant of the opportunities that we get. I came from a privileged background. My family and the Bush family were friends. We played football together, my dad and me against W. and H.W. I think we beat them, but that could be a revisionist recollection.

AA: Oh, that’s funny. Like you played football against them, just throwing the football around because you lived near each other?

DM: No, we played games against him.

AA: Oh my goodness. Really?

DM: Yeah, they were close friends and particularly the dads. I was a total tomboy when I was a kid.

AA: I love that. Tell me a little bit, I mean we’re going to want to know more about the Bushes and I know that comes up later in your life, but maybe we can pause for a second and ask you when you came out and how your family responded to that? I imagine if they were friends with the Bushes and knowing a little bit about your family, they were a very conservative family. Is that right?

DM: True. I went to one of the Claremont Colleges, Pitzer. When my mother became ill in my junior year, I moved home to be near her. After mom died, I moved to DC to finish up my degree from Pitzer and to take some pre-med classes.

In DC, I was very active in the anti-war movement and I went to one of the huge demos in Harrisburg. After I got home dad called and said, I bet you were in Harrisburg, demonstrating with those communists and socialists. Well guilty as charged. And then he said, Why can’t you just become a doctor and leave politics to the men in the family?

It seems like I had inherited the Mosbacher gene for politics, but definitely not the Republican gene. It was a rich time when many of us thought we were fighting the good fight, but at the same time, I was struggling with my sexual orientation, everything I had read pathologized and or criminalized homosexuality.

Don’t forget, Amy, we are talking about the early seventies here. One day I saw a notice about a pro-abortion speak out. It said there would be a doctor, a lawyer, and a lesbian speaker. Well, I jumped at the chance to see a real-life lesbian. I went to the meeting where I saw three very articulate speakers, but none identified herself as a lesbian.

Several months later, I discovered all three speakers were lesbians and that’s all it took. I jumped out of the closet. Once I realized these were normal successful people, not at all the women I had been led to believe they would be. But the most important thing that happened in DC was falling in love with Nanette. When she finished med school, we moved to Boston together. She for her psychiatry residency at Harvard and I to get my PhD in social psychology at the Union Institute. That was really a great time and I was really happily out while I was there.

AA: So, did you come out to your family at that time as well? And how did they respond?

DM: Well, dad kind of figured it out on his own. And when I got together with Nanette, we had dinner together and that was the start of a really wonderful lifelong relationship between Nanette and my father. He loved her and even more than that, we went to see my grandfather (who we called Pop), we went to see Pop in New York City, Nanette and I. He was great. He was thrilled that she was a doctor, and from when he met her, he called her the doc. So he was really happy to know that he was going to have two doctors in the family. It was really wonderful in that regard.

AA: That is wonderful. Was that a surprise to you that they responded so well?

DM: Yes, it was. And it was as a result of probably a fair amount of sturm und drang on their behalf. Again, we’re talking in the seventies, so it was kind of difficult, but dad was always wonderful once he accepted my being a lesbian. He was always really wonderful and very supportive.

…everything I had read pathologized and or criminalized homosexuality.

AA: Wow. That’s wonderful. I’m so glad to hear that. So then let’s see what happened next. You went to medical school back in Houston. How was that for you?

DM: Yeah, I went to Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, which was a totally different experience. I knew medical school would be a challenge because of my difficulty concentrating so I had decided to retreat to the closet as I did my time at this conservative school, but I couldn’t stay there. Especially when my friend Gary found a message on his locker saying ‘kill the queers’. We faced obvious as well as more subtle signs of homophobia in what we were subjected to and taught. So I decided to act.

In 1980, I made a slide tape presentation called “Closets are Health Hazards: Gay and Lesbian Physicians Come Out ” that could be used in schools all over the country, by anyone wanting to educate about homophobia. Through the distribution of this slideshow, the efficacy of educating about homophobia without having to travel to each school, stayed with me until I began to make videos. The magic of connecting an audience with LGBTQ people, even in slides or on film serve two purposes: one, to give courage and community to closeted individuals and two, to eliminate stereotypes harbored by straight people. My first video itself was filmed at the fifth lesbian physician conference in 1989 with my friend Joan Byron, who had helped make closets.

AA: I’m seeing some ways that you are similar to each other and probably connect so well. When Nanette talked about how if someone says you can’t do something, it makes her want to do it even more. And I’m seeing that, and I’m just reflecting that some might have retreated in that circumstance at Baylor in Texas, and then having that horrible, horrible homophobic threat. I mean, that’s just violent and awful. I might be really scared to come out of the closet and to be vocal, and I so admire your courage.

Did you have any doubts about that or were you just galvanized?

DM: I was just galvanized. I was really pissed off actually. Yeah. I was just angry and I had to do something about it.

AA: That’s amazing. Did you go to Harvard after that? Remind me what the progression was?

DM: After I completed my psychiatric training at Cambridge Hospital (which was one of the Harvard hospitals).

AA: Okay, and then after that, you were with Nanette and then you moved to San Francisco?

DM: Absolutely.

AA: Tell me about that, because I believe that was in the eighties, which was when the AIDS epidemic was happening. Is that right?

DM: Right, exactly. I became medical director for mental health for San Mateo County, which is for those who don’t know is the county just south of San Francisco. And there I treated people with severe mental illness. I also raised funds for The Shanti Project, which provided compassionate care to the dying, particularly those with AIDS. In the early nineties, I began to take on Karl Rove and the Republican party.

Rove was moving the party ever rightward and had decided that promoting fear about LGBTQ people would be just such a fantastic fundraising tool. So as daughter of President Bush’s commerce secretary, I joined the battle against the Republican party.

AA: Repeat that, Dee? What was your dad’s job at the time?

DM: He was the commerce secretary, Bush’s secretary of commerce in Bush’s cabinet.

AA: Working for President Bush, the sitting president, correct?

DM: Yes. And as I’d said earlier, they were very close friends and he had supported President H.W. Bush and all of his campaigns.

AA: Tell us about this. You’re taking on the Republican party as your dad is in the Bush administration. Can you tell us some more about that Dee?

DM: Yeah. In May of ‘92, I was invited to be the first alum to give the commencement address at my alma mater, Pitzer college, which as I said earlier, was one of the Claremont colleges. Coincidentally or not, my dad was the commencement speaker right across the street at what was then called Claremont Men’s College. I opened my address with “my father and I had breakfast this morning and we took a look at each other’s speeches. He could have given mine, but he’s not a lesbian. I could have given his, but I’m not a Republican.” Dad and I, we both laughed about the press coverage of my remarks, but our relationship got very tense as the election approached and I continued to confront the Republican campaign as it egregiously distorted the concept of family values.

The intra-family atmosphere became even more turbulent when I was the subject of a Washington Post feature, labeling me “the lesbian and the GOP family.” I was also the only Democrat in the Mosbacher family.

AA: That sounds really difficult. I mean, your dad’s raising funds for president Bush’s re-election campaign and in the meantime you’re becoming a spokesperson for LGBTQ+ civil rights, right?

DM: Correct.

AA: I mean, that would cause tremendous strain, I would imagine.

DM: Yeah, it was actually a very difficult time. My family was supposed to come out and celebrate Thanksgiving with us right after the election and that didn’t happen that year. You know, that part of our relationship was always a big challenge.

AA: Were you able to stay close with your dad in other ways? I picture you being young and playing football with him and being close to him when you were young. Were you able to stay close in some ways despite your political differences?

DM: Absolutely. He was a wonderful father. I mean, he really was a mensch in that regard, but we just had this disagreement about politics and a couple of other things that we sort of agreed to disagree. So we were able to able to stay close.

AA: To tell you the truth, of course it would’ve been wonderful to be able to soften his heart and then he has a big conversion experience to see things the way you would hope, and we would hope, but I also think it’s really beautiful that you were able to stay close. Because I see, especially right now, how polarized our country is. And within family relationships and friend relationships, I see people who are just unwilling to speak to each other because of their political differences. I personally think it’s really inspiring that you were both willing to maintain your relationship and put those differences to the side so you could love each other still.

DM: Yeah, you know, Amy, it was a different time in that regard too. And I feel very lucky that dad and I aren’t going through this today. I feel like the Republicans of that era, you know, of the eighties, nineties, et cetera, well into the mid 2000s were opponents and we could actually talk to them. I mean, we could argue with them, and we could take turns putting our arguments forth. Today they’re enemies; they’re not opponents. And we don’t listen to each other. I think none of us listen to each other in the way that it used to be. It’s very clear in the Congress that that’s the case, there’s no listening to each other anymore. And so this is a particularly challenging time in that regard.

AA: I will say too, just for listeners, I do want to remind listeners because of what I just said, that Dee, your dad was respectful to you, right?

DM: Yes.

AA: You came out to him, he loved your partner, your wife. He was a safe person for you. And it’s one thing to have political differences. It’s another to come out to someone if you are LGBTQ and have them say, I don’t support you. They can create an unsafe environment where it wouldn’t be the right approach to say, oh, we’ll just respect each other’s differences. That wouldn’t be a healthy relationship.

DM: Absolutely not. And that’s really one of the cornerstones or one of the motivators for my getting into making documentary films about homophobia. I realize very, very clearly that not everyone has had the experience that I have and I’m really lucky in that regard. And that’s one of the reasons I’ve made the films that I’ve made.

AA: Please tell us more about that. I’d love you to talk about specifically Woman Vision and the documentaries that you’ve made.

DM: Sure. As the nineties continued, our opponents developed crasser but also more sophisticated tools to battle our attempts to obtain LGBTQ rights in various states around the country. Gay bashing videos were developed and distributed in states where LGBTQ measures were on the ballot. A widely distributed video called ‘Gay Rights Special Rights’ sought to drive a wedge between the African American and LGBTQ communities by alleging that we wanted “special rights, not civil rights.” The gay agenda video claimed that we could and should be converted from homosexuals to heterosexuals. In response to those videos, I founded Woman Vision, a nonprofit with the goal of making educational videos about the LGBTQ community.

…the Republicans of that era, of the eighties, nineties, et cetera…were opponents and we could actually talk to them…Today they’re enemies.

I took a different approach. I didn’t want to use the fear mongering methods of the Christian right. As a psychiatrist, I had learned to interview and listen well, skills that are highly desirable for both psychiatry and filmmaking. I had seen the possibilities of changing minds and hearts through education delivered at a very emotional level.

My goal with these films was to model transformation. That is to show how Christian parents, whose religion and cultures had taught them to be homophobic, came to a new understanding of this kind of prejudice as they synthesized the fact of having a gay child of their own, Straight from the Heart. The first film was nominated for an academy award in 1995, All God’s Children and De Colores followed and became the Unlearning Homophobia series.

So in my next series of films, I began to examine discrimination in other parts of our culture. When I was a kid, I loved sports as I alluded to in terms of playing football and I played a lot of sports as a kid. When I grew up, I continued to follow women’s college basketball, and as an adult, as I followed it, I was really distressed that I never heard of a single coach or player who was out. I made Out For A Change, the first ever film on homophobia in sports. In 1994, Training Rules examined homophobia in women’s sports through the prism of Penn State University, which allowed its women’s basketball coach Rene Portland to bully lesbian players throughout her 27-year tenure at the university. Portland was forced to retire as a result of the film. I was the first documentarian to examine the toxic environment in Penn State’s athletic department, which blew apart two years later over the Sandusky case.

AA: I’m just astounded and inspired to know about the work that you were doing. Again, you don’t see it in the front page but those are the actions that actually move the needle. It’s so inspiring.

NG: I also wanted to add something about the Bushes related to Straight from the Heart, if I may. There was a birthday, sometime in the late nineties or early 2000s of Dee’s that her father forgot, and he never forgot birthdays.

Actually, he had assistants who were supposed to remind him and that’s one of the reasons that he didn’t forget, but somehow that chain didn’t happen. And so he asked Dee how he could possibly make it up to her. She said, please show Straight from the Heart to the Bushes. Actually, after Straight From The Heart came out, he arranged for a joint session for it to be shown to Congress, which was really incredible. Anyone who wanted to come from Congress attended. He thought he couldn’t say no to this because he had missed her birthday. So he sat down with them and asked if they would watch the film. And we have still—which the Smithsonian wants from us and we are at some point when we go to Washington will take them—we have the card that Barbara Bush and that H.W. Bush each wrote to Dee’s dad saying how much the film moved them and that they both cried when they watched it. He said that the film made him want to be a better, more tolerant person.

AA: That’s amazing. Wow.

DM: That was one of the best birthday presents I ever got if not the best.

AA: Good for you for being quick on your feet and thinking to ask for something so impactful. I have to say I watched Straight from the Heart as well, and you said it came out in 1995, I think. That’s the year I graduated from high school and there was a Mormon family [in the documentary] as you well know, Dee.

DM: Oh, how could I forget them?

AA: Yeah, I mean, it was so moving. And I thought, I so wish that I had seen that movie and that people I knew in my community had seen that movie, a Mormon family from Idaho who had a gay son. Is that right?

DM: [The son] had HIV and they cared for him as he was dying and they talked about what other people said about them and thought about them. And you know, it was, it was a very difficult experience and they were so moving, talking about it and how in such adverse circumstances they had taken their son in and cared for him lovingly until he died.

AA: Just hearing how their hearts had changed once it was their son that was gay. It was so moving and the whole documentary is different versions of that story: people discovering their prejudices and the ways that they had been taught and then realizing, this isn’t right, this isn’t true, and opening their hearts. I really recommend listeners to look it up again. It’s called Straight from the Heart and All God’s Children. Is that right, Dee?

DM: Yes, Straight from the Heart was the first one that I did and its focus is the white church-going audience. All God’s Children was the next one and the target audience for that was African American or Black church-going audiences. And the third one is De Colores and it focuses on Latino/Latina church-going audiences and the Catholic church. It became a series and as I said, they’ve been used all over the country. If anybody wants to watch them or look them up, they can be found on the website womanvision.org.

AA: That’s how I found them; easy to find and wonderful. Just highly recommended.

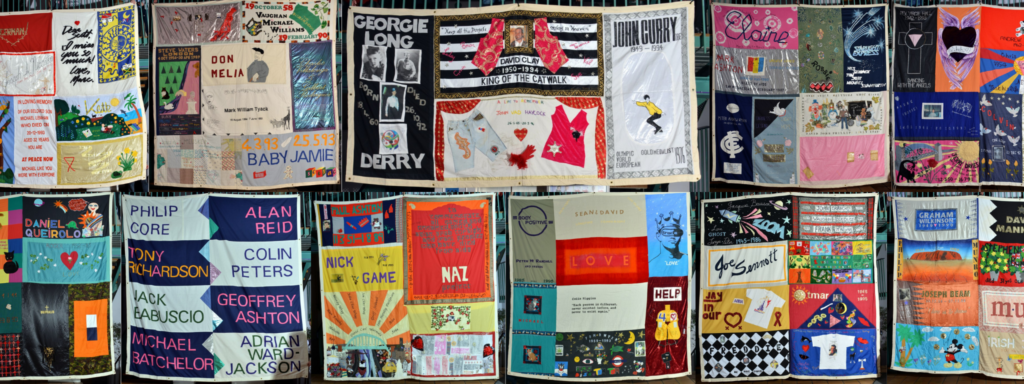

I want to ask you quickly about one more highlight for me, which was learning that you were at the mall in Washington, DC, and along with Nancy Pelosi and HIV-AIDS activist, Mary Fisher, you read names of people who had died from AIDS when the Memorial Quilt was laid out on the mall. Is that right, Dee?

DM: Yes, it was one of the most moving experiences to be there and to see the quilt laid out in that way. I mean, it was really terribly sad, but also really beautiful to see people recognized in that way. It was, in a way, like our Vietnam War Memorial to acknowledge some of the people who had died of AIDS and many of whom had actually fought to get recognition for the illness and fought to get treatment for the illness.

AA: Yeah. What an honor, and kind of a once in a lifetime experience, but also terribly sad, like you said. Okay, one last question for both of you to answer, yet another thing that kind of trickled down and impacted my life and then when I met you, I thought those two are behind that too. I can’t believe it!

In November 2016, after Trump was elected, there was an article that was going viral where psychiatrists were calling for Trump to be evaluated because it was clear that he had some sort of diagnosable psychiatric condition, that he wasn’t fit to be president. That was going viral, everybody was talking about it. You two had a hand in that so I want you to tell that story too.

It was, in a way, like our Vietnam War Memorial to acknowledge some of the people who had died of AIDS and many of whom had actually fought to get recognition for the illness and fought to get treatment for the illness.

NG: Well, absolutely. I’ll just say a few words and wrap it up, but a colleague of ours whom we had been good friends with since we were at Harvard called shortly after the election and said, Do you want to co-author a letter to President Obama calling for an immediate neuropsychiatric evaluation of Donald Trump? And we said, We’re there. And so we wrote the letter and sent it off. Nothing happened. Shortly afterwards, a prominent journalist for a major publication contacted Dee and me and said, Would you go on record and talk about your thoughts as psychiatrists about the incoming president? And we said, well, actually we have this letter that our colleague and the two of us co-authored, and would you like to see that letter? And so we got that to her. She passed it off to somebody at Huffington Post who published it, and that’s how it went viral.

We heard about it from everywhere. And then people were trying to get us to speak about it, but what it did was it spawned a movement of mental health professionals who came forward to speak out about his psychopathology, but also because of it, so many people saw it. Among those people were Gloria Steinem and Robin Morgan who became involved in guiding us about how to direct that letter and specifically referring back to things that had happened in the Nixon administration and the concerns that Nixon needed to be contained as he was being ushered out of office. [Robin] strongly urged us to get our letter to the joint chiefs of staff and Dee and I all of a sudden realized that we had a way of potentially doing that.

We won’t ever say how we did, but we managed to do it. And then Dee you can tell the rest of the story.

DM: Yeah, just parenthetically, we were kind of blown away when our neighbors, who we are crazy about, had been traveling in India at the time and they saw our letter on the front page of a news article in a small town in India.

We also were very humbled by the fact that Gloria Steinem read part of our letter at the Women’s March in DC after Trump was being inaugurated. And we also co-authored a chapter in the New York Times bestselling book, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump. Our chapter was about, among other things, invoking the 25th amendment to remove the dangerous president from office.

AA: Amazing. As we wrap up, I just again—and listeners now will see why I introduced you in the way that I did—but again, I just want to tell you how grateful I am for all of your work. You inspire me to be a better and busier person, because I don’t know how you fit in everything you’ve done. But boy, am I grateful that people like you exist and I’m so grateful to have met you. I also have to mention too, this episode airs on the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots and also on Nanette’s birthday, is that right?

NG: Yes I was born and then the Stonewall riots happened on my birthday 20 years later.

AA: As we close, could I get you to say a word about the Stonewall Riots? Do you remember those happening and how you felt when it happened?

NG: I personally was actually at Stanford’s overseas program in Vienna, so I heard about it there, but I was just thrilled that members of our community were fighting back.

The police had a long history of going in, arresting them and assaulting them and then publishing their names and having them lose their jobs and their livelihoods and everything and family exposure. Finally they were fighting back and they were stopping this kind of abusive behavior and so I felt hopeful about our future.

…good friends…called shortly after the election and said, Do you want to co-author a letter to President Obama calling for an immediate neuropsychiatric evaluation of Donald Trump? And we said, We’re there.

DM: Mm, beautiful. I was at Pitzer at the time, and I wasn’t really out yet. I hadn’t even completely allowed myself to know my sexual orientation.

I do remember that time because those years were the years in which Martin Luther King was murdered and Bobby Kennedy was murdered. It was a very tempestuous time and I was more focused at that point on the anti-war movement.

AA: Also incredibly important. Well, thank you. This wraps up our month on Pride-themed episodes, and I have learned so much and again, I’m so grateful to you, Nanette Gartrell and Dee Mosbacher. It’s just been a real honor to interview you today. Thank you so much for being here.

NG: Thanks very much.

DM: Thanks very much for having us.

And the rest, as they say

is herstory.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!