“What kind of heaven does not include my baby?”

Amy is joined by advocate Allison Dayton, founder of Lift & Love, to discuss the god-sized holes left behind when LGBTQIA+ people are forced out of their faith traditions, plus how the LDS Church can be changed through love and role modelling to embrace its gay family.

Our Guest

Allison Dayton

Allison Dayton started the Lift & Love Foundation to support LGBTQ individuals and their families in the Church Of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Allison lost her brother, who was gay, to suicide at the same time her 17-year-old son was coming out. Looking for resources to help her family, she couldn’t find anything that embraced her religious beliefs and her son’s divine identity. Lift and Love has grown to fill that much-needed space supporting thousands of individuals and families as they navigate their unique journeys of protecting their identity or that of their precious children and integrating their new reality into their devotion to Jesus Christ. Allison is a writer, speaker, including at BYU Women’s Conferences. In 2022 she moderated an LGBTQ Conversation Circle at the UN Women’s Conference. Allison and her husband, Kenn, live in the foothills of Salt Lake City, Utah, have three grown children, a son-in-law and a granddaughter, Georgia, who rules their world.

You can read more about Allison’s experiences in her recent LDSLiving article here

You can watch Allison’s presentation at Gather Conference 2023 here

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: This week our family received a wedding announcement in the mail for a same sex couple, and one of the members of this couple getting married is very dear to our family. And I was so impressed and thought it was so beautiful, this wedding announcement was. Together with their families, these people announced their marriage and the way that it was worded was full of celebration and joy from the parents. And then there was a photo and I was so struck and thought: this would not have been possible in my faith community even a few years ago. I just cannot imagine that ever happening. And so I went, and these two women had written a blog about their story and how they met. As they shared their story, they talked about how they met and then started dating and they said, “and then we realized that we were in love and this was going to be very complicated with our membership in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. And then we realized, obviously we were meant to be together, so we were going to get married and obviously we were going to stay in the church.”

I was shocked and so moved—it moved me to tears—and so grateful, and I thought, wow, have things changed in a very short amount of time. And that is greatly to do with grassroots efforts to change communities, to change attitudes and to change culture on the ground. And one of the organizations that has been doing that critically important work is Lift & Love. It was started by Allison Dayton and I am thrilled to have Allison here as our guest today on Breaking Down Patriarchy. Welcome, Allison.

Allison Dayton: I’m so excited, and that is the best segue into this because I would say even five years ago that the wish of those women, to be married and to stay in the church, was unthinkable. And it’s still an uphill challenge, but it is much more the norm. And isn’t it great? Our kids want to stay active in faith and that’s exciting.

AA: It is exciting. Oh, I’m so excited to dive in.

For listeners who aren’t familiar with the doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, we’ll explain that as we go and kind of the, the nuance of what it means. But before we dig into that, I’d love it if you could just tell us about yourself, Allison. Tell us where you’re from, how you grew up, and then what brought you to do the work that you do at Lift & Love, and you can tell the whole story with as much detail as you want.

AD: Well, I was born in Palo Alto. My oldest siblings were born there. We moved to Salt Lake when I was little, and I have a brother who is nine years older than I am.

So my mom would tell you that even at five, she could tell there was something different about him. But when he was 13 in 1973, he came out to my parents. He was sort of forced out by the bishop. My parents knew that he was gay and my mom said she hardly knew what gay was. Nobody was openly gay in 1970. I mean, I always laugh like we never really even talked about Liberace, and if you’re old enough to know who Liberace is, he was this incredibly flamboyant piano player. Nobody talked about him being gay or even Elton John for a long time. So my parents were really totally on their own, and for my parents to know that he was gay at 13 is also really remarkable because most kids of that era didn’t come out until…actually, the studies say about 26, and by they were off. They’d been living in cities far away, and then they’d finally tell their parents, and their parents would be like, what’s happening?

But I think because my brother was young, my parents were really protective of him. The therapists and the pediatricians suggested shock treatment to try and cure him of being gay, which was a catastrophic failure, and I think really damaged his mental health from such a young age. My mom says….before she passed, she was talking about how sad she was, that she actually drove him. He was young enough that he couldn’t drive. She actually drove him to do that. She’s like, how could I, how could I do that? But they didn’t know. They had no idea.

And my brother tried everything. Oh, he loved and believed in the church and the gospel deeply. He was our family historian. He was just so deeply in love with the church, served a mission, thought it would cure him. Dated girls in high school. But by the time he got home, I think he was pretty sure, you know… and my parents were sure this was just who he was and there was no changing him. So at about 24, he came out to the world and moved away from Salt Lake. Never came back.

I think I skipped that, but we were raised in Salt Lake and in a really kind of open-minded neighborhood in Old Salt Lake. Lots of great people who loved and supported my family, but my parents just knew that this was part of him and kind of from the moment that they figured this out, he was accepted and loved in our family. In fact, when I graduated from high school. My parents sent me to go live with him and his boyfriend in DC for the summer to get me away from Salt Lake, and my mom said I was getting in trouble and probably on her last nerve. So I got to live with those two men for three months and realize how just sort of mundane their relationship was. And Peter, who lived with my brother Preston, was just a dear person to me. For the rest of his life, he’s gone as well.

AA: Wow.

AD: And when I moved in with my brother, he gave me Carol Lynn Pearson’s book, Goodbye, I Love You. And she was groundbreaking. The story is this beautiful story of her husband who she found out he was gay after they were married. He ended up leaving, had many relationships and contracted AIDS, and then moved home with her and she took care of him until he died. And that was sort of the first public, open commentary or story about a gay person in the Church. And it was heartbreaking.

So I read that in 1987. It came out in ‘86, and that was sort of my introduction to this bigger world. And living with Preston, he’d take me out with his friends and they all thought it was so fun to have an 18-year-old girl around, and they all treated me so well. So flash forward, Preston moved from Washington DC to San Francisco about the same time that Prop 8 and the propositions before that were there, and with those policies, with those legal actions, his mental health just started declining more and more…

AA: If you want to quickly describe, just for anyone who doesn’t know what those propositions were?

AD: Proposition 8 was meant to stop gay marriage and it was really highly publicized by the Church and funded. And you know, I have a lot of friends and family members even who were tasked to go door to door.

AA: We did. We were living there. We were told by our bishop from the pulpit that we had to donate and we were organized and went on Saturdays and went door.

AD: Gosh. You know, it’s amazing how many parents did that and then had children come out. And it’s really hard for them. It’s a hard reconciliation.

So as that went on, it just took a toll on him. It’s interesting, even though he was accepted and loved in our family—his boyfriends came on our vacations, we bought presents for Christmas. They were fully accepted—that idea that he wasn’t accepted by the Church, the Church that his ancestors really kind of forged through the plains and in Salt Lake was devastating. And in 2017, two years after the Church policy on baptisms where children of LGBTQ or gay couples were not allowed to get baptized and had to essentially call their parents apostate to be able to be baptized at 18, that one crushed him. And he really pushed me, and we weren’t together. He was really hurt that I hadn’t called him to talk about it, but I didn’t want to talk about it because it was such an explosive time in our relationship. He was so angry and I wasn’t mature enough in all of this to understand how badly he was hurting and to be able to kind of protect him or to support him. And he said to me, “if you don’t leave the Church, I’m done. I can’t have a relationship with you.” And I couldn’t see my way through that. I had these little kids and I actually had a son who I was really sure was gay, and I tried to make it work and he was just done. And then two years later, actually a year and a half later, he took his life and we didn’t get to talk in those years in between.

It’s interesting, I was the first one to realize that it had been a week since he’d been on Facebook. He was communicating with my mom about getting some help for something/ And I’d been helping my mom, she was not able to see the computer anymore, so I’d been helping her with these emails and talking to him and just this realization, you know…

When we went down to San Francisco to clean out his house there were these relics of the church. He had this really incredible photograph taken in the 1920s by a man named Anderson. It was his church calling his church to go take pictures of these sites. It was Joseph Smith in the Sacred Grove. It was a boy kind of planted in the sacred grove where Joseph Smith had his first encounter with Jesus and with God. And I realized he had these relics. He was really artistic and I was going through all this art he’d done and he’d painted the temple recently, and I just realized: this thing was so bone deep in him. As bone deep as being gay. And he chose to leave the church to try and save himself, but it didn’t work…He had to take such a big part of himself out that it left this God-sized hole in him that he never could fill.

I got to live with those two men for three months and realize how just sort of mundane their relationship was…

And the realization of that was so shocking to me. And here I have this son who I’m trying to kind of negotiate how to talk about this and how to deal with this suicide of this brother who’s gay and keep this son healthy. And really all I could say to people for a while is we cannot divorce our LGBTQ people from God. It just is catastrophic in their lives. You can leave the Church, but to be forced out or to have to leave is just devastating in ways that he could never recover from.

So after that experience, like a year later, our son came to us, and we had talked on and off about it. I’d maybe known since he was about three that he was gay. Or I guess I’ll be honest and tell you, I worried about it. I watched this life of my brothers and it was hard and painful and it got worse and worse between us, he and I and we had been the closest. It was a hard life. And my husband finally said to me “Jake’s life is not going to be like Preston’s.” And that was the thing that freed me from this worry about him. I didn’t worry that he was gay. I just… I didn’t want to watch this beautiful child of mine have to go through what Preston did.

So after he graduated from high school, he came into our room during the summer and said to us, “Hey, we got to talk.” And he shut the door. And this is the kind of kid that’s never does that stuff. And so we’re already in bed. You know, kids, especially boys, say they want to talk to at the weirdest time. It was probably 11 o’clock at night. And he’s like, “Hey, so… I’m gay.” And I was like, “Yeah.” And he’s like, “How did you know?” And I said, “Well, honey, there were signs, right?” He said to me, “How was it easier for you to see it than me?”

And that’s a really good question because it was very hard for him, even though we had talked about it on and off for about five years. It was hard for him to come to it. He really resisted it. But we just were like, “Hey, it’s going to be great.” And he came up and got in bed with us and we were talking, and my husband’s like, “I’m so proud of the way you’ve handled this,” because he was super prayerful and he wanted to know what the best thing for him was. And you know, we had talked about being healthy and that we’d figure this out together. And it’s funny, I tell people my husband fell asleep. I mean, it was that calm of a conversation. We weren’t worried we weren’t, it was just peaceful. Like, yeah, this has always been, and this is you and we’ll figure it out.

So a year later he brought a bunch of kids home from BYU to go to the Pride Festival in Salt Lake and they were all staying at our house and I made breakfast and I started like… I’m big into just getting right into the meat of things. And I was asking him about their parents and their lives and coming out and if they had support and none of them really did have any support from parents. So I had this overwhelming feeling of like, these kids need help. So I thought, well, I’ll start an Instagram account. My background is advertising. I graduated from advertising in BYU and I’ve been in advertising for years. I’ll start an Instagram account (this is in 2019) and I’ll just kind of speak from a positive place of having a gay child and having a gay brother and how this is actually really a positive. And then I thought, well, I’ll help the moms because the moms need support. But really quickly, within two years, I realized that it wasn’t the parents that needed support loving their children. They were in conflict with the Church.

AA: Hmm.

AD: And that’s where Lift & Love really started taking off, is when we started focusing on that conflict and that faith crisis that you go into as you’re like, wait a minute, this isn’t what I thought it was. How are we going to take care of this child and make sure they’re healthy? And that’s really what Lift & Love has become, is this space for LGBTQ people and their parents and allies to really come and sort of see things in a different light and be able to kind of balance that thing that my brother felt like he couldn’t balance, that he had to give up one or the other. So that’s sort of the long and the short, uh. I didn’t ever intend to do it, but I just felt really compelled.

AA: Well, thank you for sharing all of that. And I’m just so sorry about your brother. I am devastated to hear that.

AD: In fact, it’s been eight years this week, which is a hard milestone, but I was just in San Francisco with my son and he graduated from grad school and it’s just…it’s tender to be there with this boy who’s doing so much better. And is so comfortable with himself and in our family. I’m so grateful. It’s the gift I think that my brother gave to me kind of unknowingly.

AA: That’s really beautiful.

Before we move on to some of my other questions, I want to talk for a second about what it does mean. Like you were talking about not having to give up one part of yourself, that you have to choose between them. And one comment that I see on Instagram, especially on social media all the time if I ever talk about, for example, patriarchy or homophobia or racism or all the things in religion that—people will say like, “So leave.” Or I mean, not even just on social media, people will say that in person. They’ll be like, “What’s the big deal? Leave the religion. Why are you part of a homophobic, patriarchal, sexist, racist religion? Just leave.”

And for people who haven’t been in a religion like ours, I can understand from that point of view, like…what in the world? Why would you want to stay? So I was wondering if you can speak to that for a minute and just dig in a little bit more on what you said, which is….if people do want to leave, that’s fine

if they feel like that’s the best choice for them. But in speaking about your brother, it was clear that he didn’t want to go and that it was really a deep part of him. He wanted to maintain his faith. Can you talk about that just a little bit more and that context from what it feels like on the inside?

AD: I think it’s really complicated for any kind of high-demand religion. You’re putting a lot in and getting a lot out. The problem, it comes when you don’t fit in that space. And I think especially for families who have been in this…I mean, every single one of my grandparents came across the plains, left everything in England, left everything behind, left family, and came here. And they really were kind of Church builders. They were kingdom builders, as some people call it. And so it’s part of our lore, it’s part of our family history. The way we see God, I think, reflects relationships in our home. The way we see heavenly parents.

A lot of times I’ve found that people really have the same kind of relationship with deity that they do with their parents. If they have a good relationship with their dad, they’re more likely to have a good relationship with a father in heaven. If not, they might have a better relationship with a mother in heaven. But everything…it’s the language that you are taught from youth, it’s your value system. Everything is wrapped up in that belief system and there’s not a lot of separation. So to have to leave that…

In fact, I was talking to my sister who came with us this weekend who’s no longer active in the Church, and she’s like, “I’m still Mormon. The way I see the world, the way I interact,” and really the way she believes, even if she’s not participating or doesn’t believe in a lot of the things that I still kind of hold true or dear. It’s your first language. It is the way you see the world. And that is not an easy thing to untangle. You kind of can’t.

AA: I agree. To me, it does feel like a language and, for me, the closest analogy is like… we went and lived in Spain as a family for a little while and we could function fine in Spain and we all speak Spanish, but how it felt when we would be in a grocery store, for example, and hear Americans speaking English. That happened one time, because we were kind of a small town in Spain. And immediately you’re like, “Americans!” like “English!” And that’s how it feels, I think to leave the Church. It’s like moving to a different country, a very foreign country. You can learn a new language. You can learn different customs. You can learn customs, but you always will speak English with the accent you have and the foods that you grew up with and the songs you grew up with as a child. And.

AD: Well, think about all the traditions that are so important.

AA: Traditions. Everything.

AD: Everything, everything. The way we celebrate Christmas morning or… You know, and though those things come in conflict when you get married or you bring someone else into your life and you have to kind of negotiate your way through those things. But yeah, it’s deep. I mean, it is really bone deep. It’s the way you see yourself in this bigger world. And that’s really anchoring. And it can also be really damaging if you don’t fit. Or if you’re coming in conflict as like a strong woman and you’re hitting into this patriarchy thinking, what is the deal? Why can’t I move this problem?

Like, I’m capable of moving and changing things and I’m hitting into this, you know. So anytime you’re coming up against the hard things…and there are so many good things in all faith traditions, I mean really important things.

AA: And so to ask someone, to say, “Well, so just leave, just leave” would be like saying, “Pick up and move from America.”

AD: Right. Exactly. And you won’t know the language. So you’re going to have to learn the language, learn the customs, and you’re always going to ache for the thing that is bone deep in you.

AA: Yeah. For home.

AD: Right. It’s home. It’s home. And most people can agree there is really good stuff at home. Even if it’s painful in a lot of ways. And you know, that’s a little bit the tension that we teach, like we work through with Lift & Love and that’s the tension we have too, in politics and with people that we love, that make us furious sometimes. Like you have to be able to learn to manage the bad and protect yourself from the bad and kind of work through that so that you can accept the good.

AA: Mm-hmm. Well, and I mean, to continue this metaphor a little bit, like if your choice is like, “Oh, if you don’t like America, then go to a different country, then leave.” I mean, that’s one choice and some people do choose to do that. But there are a lot of people who say, “Actually no. I think that America could be a better version of itself and expand to be a more healthy home for the people who do want to stay, who are Americans who say, I love it here. And I am part of here and we could be doing better.

AD: And we will. And there’s this hopefulness that we will do better. We’ve got to get through this. And this is ugly and messy. I mean, I think everyone can relate to this right now. Like it’s ugly, it’s messy. We don’t love where it’s going. Nobody’s really that happy with things that are happening in America. Right? Especially if you’re paying attention. And even deeper than just, you know, news bites and whatnot. Nobody’s happy. But we’re all hopeful that we can do better and that we can be better than we were before, hopefully.

AA: So the difference though between a democracy where we get to vote and where it’s understood that the people will determine the policy in our country, as citizens in our country and then…I mean, this is where the metaphor doesn’t exactly translate because in the Church, we don’t have that democratic ideal of the people are going to be the ones to make the rules, right? Because it’s top down. The LDS Church does have a doctrine of policy and really, really doctrine comes from God through a very set chain of command, with the prophet—and it’s all male—and down and so there is a big tension in even just raising an issue and saying, “I think that the church needs to change in this certain way.” That’s seen as heretical by a lot of people.

AD: Totally, totally.

AA: So tell me, as you were starting, going back to your kind of like your narrative of how you started Lift & Love and you said, “sure, the parents do need support,” right? “The kids need support, the parents need support.” But then it sounds like you’re saying it started to become apparent that you were seeing ways that you wished the Church would actually change. I mean, how do you even go about that?

AD: So I can’t change the Church so much as… I’m always about like, let’s just change things. That’s so me. But what I’ve had to do and I’ve had to learn it myself really, and I’m kind of idealistic, like ‘this isn’t working, let’s just fix it.’ But we spend a lot of time. And I’ll be honest, the work of children and raising LGBTQ children largely falls on mothers. I think for fathers, you know, Brene Brown said that the worst thing a man can be called, like the deepest shame a man feels is when he’s called feminine. So this really runs into gay sons, right? That’s the worst thing you can be so. Men have struggled, especially with gay sons. I think it’s a little easier on some men to have a gay daughter, and then trans kids are complicated for everybody right now, especially in the light of the political conversations that’s so hurtful.

But the work of this falls on moms, and I found that if a mom is confident in her own self, in her beliefs in the gospel and that she’s able to say, “I don’t agree with that. I’ve thought through this, and I’ve studied it. I don’t agree with it and I’m okay with that.” The more confident they are not only in themselves, in their marriage and in the church, the better they do, they almost don’t need any help because they’ve already done that internal work of like, ‘okay, I don’t fit in this one belief system and that’s okay. I’m still going to show up because I believe in all this other…’ So those are the moms that really do well. They don’t need me. They’re there, they want to help or they don’t need the support.

Then there are the moms who haven’t done any of that work and all of a sudden they’ve been very black and white and all of a sudden they’re like, ‘this incredible child of mine does not fit. And not only that, but they’re being harmed in this system.’

One of the big problems is that…I’ll tell you, so my brother’s generation is sort of the first generation. They came out about 26 years old and people thought they had chosen it. They moved off to a big city, they’re not involved in the family, and they come home and they’re gay and it’s like, ‘wow. They just were out there living in sin. They don’t even have any respect for marriage or anything.’ And you know, it was easy to look at them and be disgusted or whatever. So then this next generation, which is roughly like kind of Gen Xers and a little bit younger, kind of early millennials, but mostly Gen Xers, we look at them like, ‘well, maybe you didn’t choose this, but you can certainly control it and don’t act on it’, is kind of a phrase that you hear a lot.

The problem is for a child and an adult to embrace that belief. They have to believe that there’s something really wrong with them. That the way they function is not acceptable, not only in the family and in society, but to God. And again, that causes immense damage. Like ‘I’m not okay and there’s nothing I can do about it until the next life. I either have to marry someone of the opposite sex or be celibate my whole life or just leave the whole system.’ And those were sort of the choices. And many kids, especially from my generation, tried to be married and tried to pray away the gay or to marry hoping that it would cure them, but the internal damage of, ‘I am so wrong. Just who I am. Even if people say it’s okay,’ it really damaged and it continues to damage people.

AA: Because I would say that’s the narrative that the church still espouses, right? And now they’re saying, “oh, it’s, it’s okay if you have those feelings. But you cannot act on them because acting on them is a sin. That’s still what they’re saying. Right?”

AD: That is what they’re saying. And the problem is we don’t support people who we ask to live that way. So what does that look like? Like do we have a group in our wards to take for LGBTQ people that’s every week? Because they don’t have the same community that we do when we’re married and have children and have our kids in soccer and you know…are we supporting them? Are we taking up the, you know, ‘I’ve got Jerry for lunch this week’ and ‘what are we doing to support them in their aloneness? What are we doing to help them?’ And we don’t. And what are we doing to help parents with these kids? We don’t have any structure. We just say, “This is on you. Fix it and don’t talk about it. And don’t show it.” In a monastic or a priest kind of situation, you are treated with great respect for giving all that up. But we don’t have that system.

The other problem is that, and I say like this Clayton Christensen disruptor happened…

AA: Okay, explain what that was.

AD: Okay, so for those of you who don’t know, Clayton Christensen is an LDS man. He was a authority, but he was at Harvard and he came up with this disruptive theory. So Uber disrupted the taxis, right? It changed the way people were getting around. What happened for our LGBTQ youth is that children, because of the internet, social media they could get information, they could find community, so they knew…like, in fact, Utah is the number one place for the Google question “Am I gay?”

This incredible child of mine does not fit. And not only that, but they’re being harmed in this system.

AA: Mm-hmm. I’ve heard that.

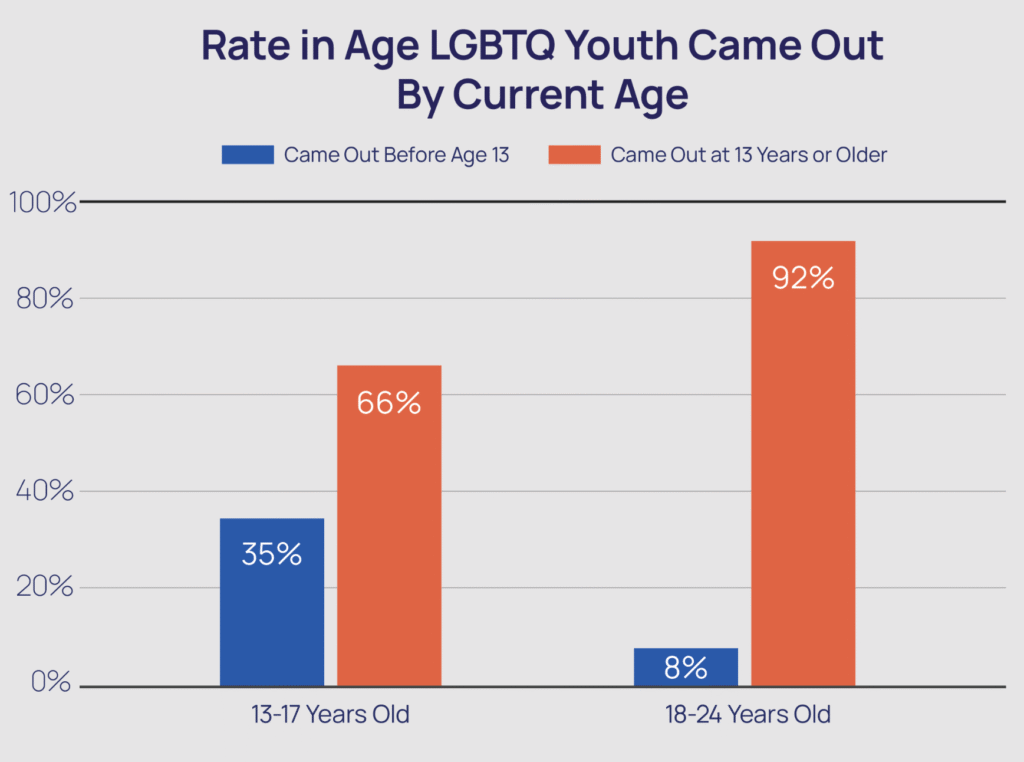

AD: And there came a real acceptance amongst kids at school and they, you know. My kids will be like, “That’s just who they are.” So this was the very first generation, and the study shows that kids—it’s about five years old, this study, —but kids came out at 16. For the first time ever LGBTQ children were coming out while they were still living with their parents. And that was the disruptive factor. I mean, I would say social media disrupted it, but the end result was we have children coming out, not when they’re out in the world living on their own and we’re just expecting them to handle it, but now that their parents are in charge.

And this study, I would say that the average is probably closer to 13 now, as they’re coming into puberty and they’re starting to understand their own attractions before…and it’s completely not sexual. Right? Because in the LDS Church, we really sort of suggest that kids don’t date till they’re 16. So even with this older study, it’s before they’re dating. But I would say it’s 13, 14 now.

AA: Wow. So you’re just saying it’s not sexual, meaning they’re not acting on it. It’s just like, as we know how it feels—you’re getting crushes. You’re getting crushes, you’re noticing…it’s super innocent.

AD: Yeah. I mean, I guess you could call it sexual, but it’s not lusty. It’s not all those things we thought about LGBTQ people or gay people back in the day. That’s not even… it’s just normal.

AA: It’s just starting to wake up. You’re starting to go online, right?

AD: Yeah. Like Jake was just a little different. It was a little like; he was more sensitive. There was just something about him. In fact, I ran into a dad and he said he knew his son was gay at two. And I said, “How’d you know?” And he said, “Well, he just wouldn’t leave the Barbies. He would not give up the Barbies.” So a lot of people are feeling this in their kids and not afraid of it like I was. So you’re looking at this child thinking, ‘Hmm, yeah, there’s something there. I’m going to watch out for that to protect this child.’

So they’re coming out at 16 and now the responsibility is on the parent and you’re supposed to say to your child, “There’s something wrong with you. Who you are isn’t right, and God doesn’t want you this way.” And you know… it doesn’t ring true. Not only that, as a parent, you would never do that to a 14-year-old and crush them. Like, there’s nothing wrong with you. You’ve developed differently. And I’m okay with that. I’ve seen really great LGBT or gay people or whatever grow up and be healthy, and I’m okay, and I want you to be healthy. I want you to be able to stay in this religious tradition and love God and know that you’re loved by heavenly parents, and that you can be guided as all the things that I wanted for you before. I

n fact, we’ve taught you to grow up and want marriage. We’ve taught you to grow up and date chastely like. You can still do those things. In fact, we just said to our son at the beginning, like, I expect the same things out of you that we’ve always taught you. And that was the end of that discussion because it’s the same thing, you know? I still hope that he finds a great guy to marry and has children. He really wants children. So it’s like your friend, right? This is what I want for you. This is how I grew up. This is how I became who I am; with sacrificing for my husband and having children. Which was not easy. And raising the kids and giving up the things that I wanted for the kids and my selfish desires, like…that’s the making of most of us, right?

AA: Mm-hmm.

AD: So we’ve got these parents and you’re supposed to sit down—you’ve got four kids, and you’re supposed to tell one of them they don’t get to go to prom. They don’t get to date, they don’t get to marry. Like…it doesn’t work.

What does work is sitting with that kid and saying, “What does your life look like? What do you want out of your life? And let’s talk about that.” Let’s talk about, you know, if you’re a gay kid, like let’s talk about you as a boy, you’re dating men. I need to raise my gay son the way I raised my daughters. Like, here’s some issues with dating men. You need to be careful. You need to protect yourself until you know them better. These are things we do with women that we don’t do with men, and we leave these poor kids, we leave them in this dangerous position.

So that’s kind of where most parents, especially the younger parents—so now we’ve got millennial parents having Gen Zs. And that is definitely where they’re going, is like: ‘I want this child to be healthy and strong and to find love and to be accepted.’ The problem comes when the narrative at Church is painful for these kids. So you’ve got this kid coming home from seminary saying, “Do you know what my seminary teacher said about me?”

AA: And tell people what seminary is?

AD: So seminary is our…we have like an instruction from the time they hit high school age. Depending on where you live, you might be instructed twice a week, early morning by someone who, you know, their volunteer church job is to teach you. Doctrine and study as part of your schoolwork in Utah and some other places. It’s release time, so you can go straight over across the street, but it’s really what it sounds like: it’s a seminary school. So to teach our kids not to be a priest or lifelong work, but just instruction in the school.

AA: It’s like Sunday school during the school week basically.

AD: Exactly. But oftentimes these kids will get messages from their seminary teachers or someone in the Sunday school on Sunday mornings that say there’s something wrong with you. They probably don’t know that this child’s LGBTQ. So then the kid comes home and they’re like, “I don’t want to go to seminary anymore,” or “I’m not going to Church. Did you hear what they said?” Or the parents felt the same thing. And so all of a sudden we have this doctrine that’s all about families except for not yours. And it doesn’t create a path for your child to have a family, and that’s when it starts to be not good for our families. And the parents have to really work through, like, ‘is this good for us?’

And people would say, “Oh, those parents, they just left to support their child.” And it isn’t that simple. They started looking at their family in the face of like, ‘are we a family forever like we’ve always been taught? As we’ve believed? Or is this child not going to be able to live with us?’ Which is what some people think.

AA: Mm-hmm.

AD: I mean, that’s ridiculous to me. What kind of heaven does not include my baby? He’s not a baby, he’s 25, but this child who I adore and my brother, like… what kind of heaven does not have those two in it? It’s no heaven for me. So it starts you thinking like ‘what is this?’ And that’s when really that work of like, ‘I’ve got to start thinking through.’ This happens and that’s where the division, where parents are likely to take their children, all of the family out of the church is when they feel like their child’s being harmed at church.

AA: And that’s the tragedy, right? And that’s what you do at Lift & Love is saying like, ‘this is for parents and for families who want to stay. That is a tragedy.’

AD: Yeah. I think it’s a tragedy too for the institutional church to lose all of those wonderful families if they want to stay, and it’s a tragedy for them.

AA: So what have you done at Lift & Love? And maybe you can share some stories of people that you’ve helped or some stories of people that you’ve worked with at Lift & Love and then what the results have been?

AD: Well, I think all of us, when we go into these new situations, we feel really lonely and there’s nothing worth than being alone, right? I mean, all the studies show that belonging is really the most important thing, what people find at Lift & Love or the Gather Conference that we have once a year, or the gatherings which are like—we have curriculum for once a month, we call it Come Follow Me in the Church, but it’s really just like home study. So we have a curriculum that you can use if your child is okay talking about the Church, if they’re sort of okay. Or if they’re not at all we’ve got these curriculums that we do and we’ve got support groups. But the most important thing is like, ‘I’m not alone. There are other people doing this and they’re doing it successfully.’

And so I would guess we model how to stay in this place, how to work through the tensions. And the tensions are: I’ve never experienced anything like having to just sort of work through this tension between this belief, the way I believe in God, and this tension of like, I know that this child is important. And they’re incredibly important in our family and they’re important to God. But it’s also sort of been the making of my relationship with the savior and with my heavenly parents, because I feel like they’re helping me. I go to them and say like, “What’s the deal? I need to understand this.” And it’s made me so close to them in ways that just regular worship was not doing. And I think a lot of families find that.

I mean, I have so many stories, but that’s the one like…I was at a pizza place in St. George. We were traveling home, my girlfriend and I were traveling home from painting outdoors in southern Utah. And this man, I was introduced to these people who were friends of a friend at a pizza joint. We grabbed pizza, we got back in the car and he came running out to the car and said, “You’re Lift & Love!” And he said. “You’ve saved us, you’ve saved me, you’ve helped me manage how to take care of my son.” And we just talked and how like he was deep in the throes of that tension. And I think the really important thing is once you realize this is like any other thing that comes up in your life. It feels like so catastrophic when it happens, when your kid comes out, to some people. But when you realize this is just like anything else—you use the same tools, you’ve got to manage it the same way. People just really ease into it and it’s not as hard as it seems.

AA: Hmm.

AD: About three years ago we started doing support groups for LGBTQ, like we’ve got a women’s group for LGBTQ women. We’ve got a group for people who are in mixed-orientation marriages, people who are spouses of queer people. We’ve got moms, moms of trans kids. We’ve got about 12 different support groups that we do once a month. Those tend to be really…like any kind of place where people can talk and work through kind of how they’re feeling and see other people doing it.

There’s just not any modeling. We don’t talk about it. We’ve never really talked about it in the Church. My mom had nowhere to go, no one to talk to, and we’re still there. So, yeah, we’ve become this place, we’ve become this kind of repository.

AA: So you’re filling a void, really, because like you said…I thought that was so interesting and never thought about it in exactly those terms when you said a few minutes ago, just that the Church is trying to make efforts to say like, ‘okay, we don’t see their LGBTQ, queer nature as inherently sinful’ and like, ‘oh, we want you to stay. We don’t want you to leave.’ But then they offer absolutely no support. No support at all. So that’s the void that you perceived and that’s what you’re filling.

AD: Well, and people repeat stuff that was said in the seventies, eighties, nineties, and early two-thousands. Which, I get that we want to keep aware that those were beliefs that we had, but because of the internet and social media, those things live in the hearts of people.

AA: Yeah. It’s awful.

AD: And it’s super painful. So, yeah, it’s hard.

AA: I’m curious also what the reception has been of Lift & Love, and especially if you’ve heard back from anyone in the institutional Church? Have you gotten any pushback? Or like some people will get kind of warnings that you’re getting out of line. Have you felt that at all?

AD: Actually there’s two answers to that.

One: I’ve had really great reception. I was able to speak at BYU Women’s Conference, which is really the only conference of women in the Church. I spoke two years in that. The first year I gave a 25-minute talk about my experiences. I talked about how like as a mom, I really connect to God and I connect to my child, but my child’s connection to God is separate from mine. Even though I want my child, you know… I want to do all that stuff with my kid for them. Like you connect with God, you do all this stuff…it doesn’t work that way.

So one of the Presidents of the Relief Society, the general women’s group at the Church, was there and invited me to come speak at headquarters. So I spoke last August to the Relief Society, the Primary, the Young Women’s, the Young Men’s, and the Sunday school Presidencies, General Presidencies of the Church and the Boards. I gave this presentation with another woman who works with the church….

AA: So listeners know, this is like the international headquarters of the LDS Church. These are the leaders for the entire global Church. That’s a big deal, Allison. That’s a big deal.

AD: Yeah. And it really was. It was special I felt, and they came up after and were like, ‘we need to know this. We need to hear more of this.’ And that felt really awesome. And I think as they go through the world and talk to people…because people will tell me anytime one of these leaders or any of the 70 (who are sort of the organizational leaders) go to meet in different congregations, they could ask the same questions about LGBTQ people. So hopefully that was great.

AA: I’m curious what you presented to them. You said that they said, ‘we need to be hearing this.’ What was it that you shared with them?

AD: Well, I talked to them about how I was raised with an LGBTQ…I said, I was raised in an LGBTQ family. Not that my parents were gay. But that’s part of our family culture, was having a gay person. My friends in high school knew that I had a gay brother, and it really changed the way I saw things. And then talked about having this child, and I talked about how hard it is to come to Church when people are talking about, you know…I think the narrative is or was that gay people and trans people are ruining families. And it’s absolutely not the case. I mean, Jake is just as much part of my family and an important part of my family is the other two. And I think we are all stronger for him in the family.

So I talked about that and I talked about how to talk to parents. I said, you know, a lot of times parents will become protective of this child before the leadership, the local leadership even knows that there’s a gay kid or a trans kid in the family. And they’ll leave before anybody knows and then you’ve lost this entire family and the generations that come from them and the gifts that each of them bring to the church. And we need all these gifts. I mean, these are important gifts. So we’re losing the valuable resource of people because we are not there for them.

So we talked about that. I talked about the suicide rates. LGBTQ children are four times as likely to attempt suicide as a non-LGBTQ child and trans children are even higher as you can imagine. And I mean, everything about our Church is about children and family, and in this one space we have a black hole.

it’s a tragedy too for the institutional church to lose all of those wonderful families

So just talking to them about how to help their kids. I mean, really, like I have to do things differently with this child. I know that it’s best for Jake to marry and to have a family. That makes him ineligible for the temple marriage that my husband and I have. But I also know that that’s a really important thing for him and I have to be okay. I have to be courageous and say ‘that’s okay. This is what’s best for my child and I know what’s best and I have this connection to God, to our heavenly parents.’ They have guided me, and to be able to say that is hard. It doesn’t sound like a hard thing to say. And it was easy for me just to say, but it’s hard in the face of, “well, that’s not right and you shouldn’t be saying that.” But each of us have to be courageous in standing up for what we believe and being able to help people do the same.

Now, the second year I spoke at BYU, there was a group that… I’m not even going to name them because I don’t want anyone to know about them, but they complained and they sent out social media things and got BYU got a lot of kind of like emails, like ‘why are you having these people come talk about LGBTQ?’ And ‘this is against our religion’. And we actually had to have police the next year at the two sessions that I was in.

AA: Oh my goodness.

AD: Yeah. And then this last year they didn’t… there’s another thing called Education Week. And they said they were too worried about me speaking and then I didn’t get asked to speak at BYU Women’s Conference again. So I’m not sure what the deal is there. I think the one problem is, is that there’s no place within the Church organization for people to go if they’re having problems. So a lot of people call me…like a man who was coming back to Church, was married and had been an addict for many years, and wanted to go and talk to his bishop and repent of that. Like he was feeling this really sacred feeling of ‘I want to get rid of this feeling.’ So he went to his bishop and his bishop went to the stake president who’s over sort of the bigger geographic area and over the bishop. And he said, “Well, you’re going to have to divorce this man.” And the guy was like, “No, this man’s been so important in my life.” The bishop told him, and then he went back to the stake president, they were like, “We’re commanding you to divorce,” which…we don’t do that. In fact, I ran it up to a bunch of people and they said, “No, that’s wrong advice.”

But there’s nowhere in the church, there’s no support group, there’s no office that’s helping people or taking these horrible situations where they’re being treated badly. So there’s really nowhere for people to get relief. And I think that would be the best start. And conversations, there’s no conversations going between the higher leaders that are even above the organizational leaders and anyone in the LGBTQ community or, you know, Lift & Love or whoever. And that’s a shame.

AA: Mm-hmm.

AD: So the Gallup poll for the US is like 9.3% of people identify as LGBTQ. Internationally it’s 11.4%. But if you are Gen… let’s see if you’re Gen Z it’s 23%.

AA: Wow.

AD: It’s almost a quarter of our kids. Now, not all of them are going to be in same sex marriages, and not all of them are going to transition, but they’re identifying that way. So we have almost a quarter of our children identifying, and we’ve got no systems to accommodate that. And that is a problem. And it’s going to be a bigger problem as these families try to wrestle with what to do and there’s no support.

AA: Mm-hmm. Well, as we wrap up this conversation, Allison, I’ve been asking everybody, all my guests on this season of the podcast to share some calls to action. So that listeners who do feel moved to get involved or want to do something to help, to take action and do something about the challenges that we’re facing. So what would you say would be some action items that we could take away from the conversation today?

AD: Okay. This is such a good question and people say to me all the time, “Oh, you’re doing such good work.” And I’m like, “Well…jump in. Come on in.” I mean, if you have an LGBTQ child, support and love them and talk to them and be open and comfortable telling other people how you’re choosing to raise this child and teach them about God and all the things. I love the phrase ‘choose courage over comfort’ because I think that is so much harder than it sounds. Being courageous when everyone in our religion seems to be thinking this one thing, or whatever it is, is hard. It’s hard and it’s hard for us as women to stand up and say, “I’m just seeing it different. I’m going to do this differently.” What needs to happen is when LGBTQ people are disparaged or made fun of or if you’re uncomfortable, tell your leader “I’m uncomfortable with this situation,” because that’s how the information gets up the chain. But if you’re uncomfortable, I would say choose courage over comfort if you can. If it’s not harming your child or you stay and stand up for what you know to be right, whatever that is.

I’m just reading this book by Richard Hanks about his father, Marrion D Hanks, who was made a General Authority at like 31 and was a General Authority his whole life, never an Apostle, which would be the next step up. But he was the Mission President for Elder Holland, Elder Cook and Michael Quinn, who was a writer, a feminist who has a long history with the Church, good and bad, and was very insightful. But he would get thousands of letters, and he got one from a couple who wanted to leave the church because they were really angry about things that leaders had done and they just couldn’t reconcile it. And he said to them, he talked about Paul and how Paul was uncomfortable. The Apostle Paul was uncomfortable, like in Romans. He was meeting with them and they were doing all these things. They were judging each other and he said, “but Paul stayed in that uncomfortable space and spoke against it.” Okay, so I’m going to paraphrase what he said. He said the road is not easy and he—Marion D Hanks—was conflicted with a lot of things that we taught in the church. He was like in the forties, fifties, sixties, seventies. It was very conflicted. And he said, “The road is not easy. I walk it with heartbreak. My decision is made to stay in and lift and love,” he said, which I love of course, “and recognize the utter indispensability of the institution as an instrument to get God’s work done.”

And I do really believe in the instrument as an important tool for love for lifting people. Gosh, we do so much good when we are other-focused and I really believe in that, and that struck me because I feel like that’s sort of my path; like stay and lift and love others and just be sort of a model of what we can do to change. I think it’s the only way when we have so many people who are really just trying to follow. I think it’s the only way to show people how to mature into that ‘second phase of life’, as Richard Rohrer would say, or to just focus on what’s important and to mature in religious beliefs is for all of us. I need models. We all need models. So stay and lift and love if you can.

AA: Well that’s really beautiful and I do appreciate that so much because I do know so many people who—as you said at the beginning and all the way through—don’t want to leave the church, and there does need to be change, and there does need to be more lifting and loving and welcoming and expansion of people’s individual hearts and institutional changes to make it a welcoming place for people who do want to stay, so that it’s safe and doesn’t do any harm.

AD: Right. And then, I mean, this forevermore, is part of our families. And so we need to adjust. And we need to make it a safe place and a loving, embracing place for all families.

AA: Wonderful. Well, tell us really quickly where people can find your work, your Instagram handle, or everywhere else that you are.

AD: Yep. @liftandloveorg is our Instagram handle. Liftandlove.org is our website and gatherconference.com is where you can sign up. We have Gather Conference in June, at the end of June. It’s going to be kind of an amazing event, and it just feels so good to be together and to love one another and worship with all of these things in your heart. Come find us.

AA: Fantastic. Thank you so much, Allison Dayton. Thank you for talking about this.

AD: You’re so welcome. I love it.

we’re losing the valuable resource of people

because we are not there for them

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!