“I would love my life to not have to be so brave”

Amy is joined by married partners – poet Phillip Brown and therapist Andres Brown – for an authentic and heartful exploration of queer identity, queer safety, queer relationships and patriarchy through an exchange of poetry and conversation.

Our Guests

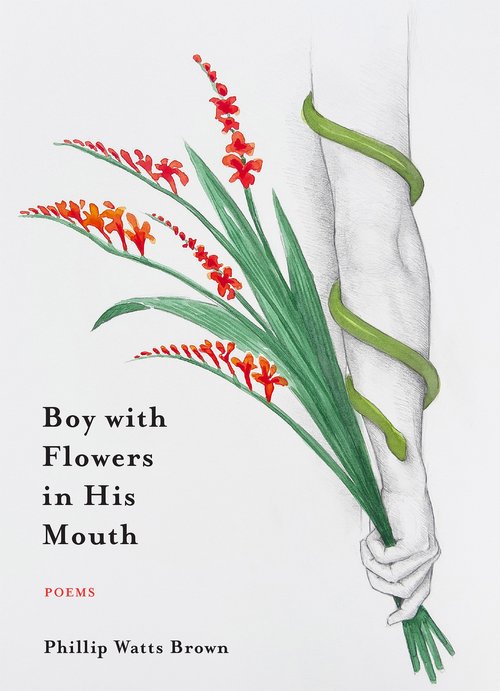

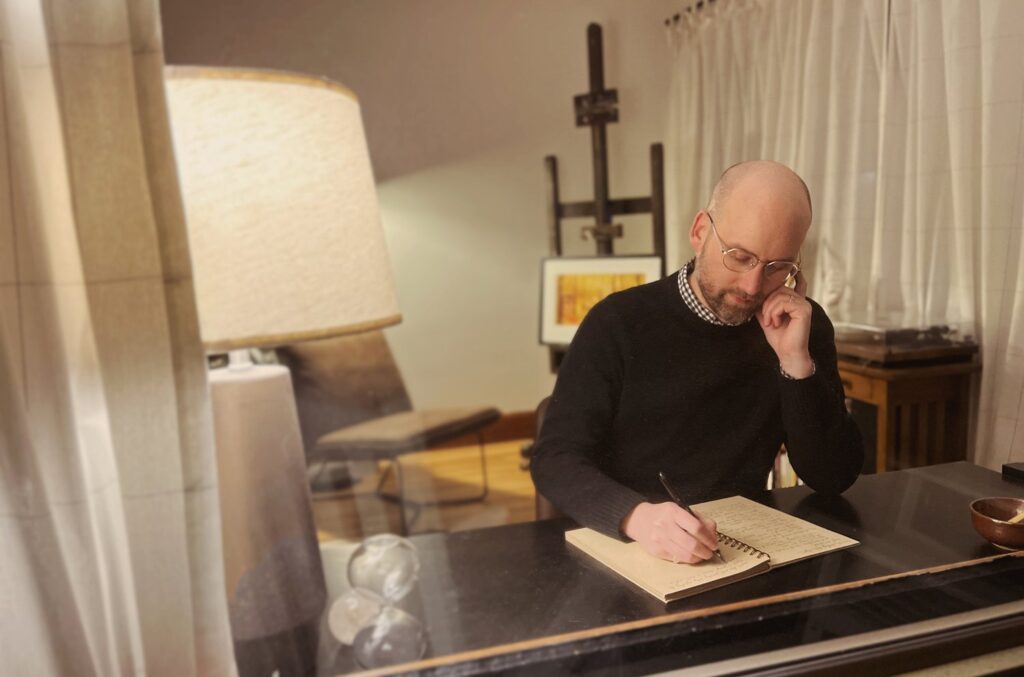

Phillip Watts Brown

Phillip Watts Brown is a poet and artist after earning a BA in graphic design from Brigham Young University. He earned an MFA in poetry from Oregon State University. He is the author of Boy with Flowers in His Mouth, which was published by Gold Line Press in February, 2025. His work has appeared in literary journals and anthologies, including Ninth Letter, the Common, Ruminate, Nimrod, Tahoma Literary Review, and others. Phillip lives with his husband in northern Utah, where he works as a graphic designer. He’s also a poetry editor for the online literary journal, Halfway Down the Stairs.

Andres Larios Brown

Andres Larios Brown (They/Elle) is a Utah-based licensed marriage and family therapist dedicated to healing for LGBTQ plus communities. As training director and partner at Simple Modern Therapy and Institute, Andres focuses on trauma, healing, and wellbeing for those who feel marginalized or othered. Andres specializes in identity development and reclaiming healing practices for queer, trans, and BIPOC communities. As a therapist of both lived experience and learned expertise, they are committed to helping LGBTQ+ people thrive.

In addition to providing therapy, Andres focuses on creating and facilitating training for therapists and teaches at U of V’s Masters of Social Work Program and U of O’s Couples and Family Therapy Program. They have co-authored a chapter in the Rutledge International Handbook of Couple and Family Therapy, as well as a number of other articles in different academic journals. Through therapy, teaching, training, and advocacy. They seek to bridge the gap between research and clinical practice. They and their husband of eight years live in northern Utah where they spend as much time with family and loved ones as possible.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: The poet Alan Ginsburg said “poetry is the one place where people can speak their original human mind. It is the outlet for people to say in public what is known in private.” As a groundbreaking gay poet, Ginsburg did indeed say things out loud that previously had only been known in private. And in doing so, he gave permission to those who read his work to speak their original human mind. Today I have the great honor of speaking to a poet whose work absolutely takes my breath away. His name is Phillip Watts Brown, and joining us also is Phillip’s partner and spouse, Andres Larios Brown, who is a brilliant therapist. These two magnificent souls are going to be sharing their poetry and their wisdom on several topics regarding LGBTQ Life that I have wondered about, and I am so excited to share this episode with the breaking down patriarchy community today. Thank you so much for being here, Phillip and Andres,

Andres Brown: Thanks for having us.

Phillip Brown: We’re excited to be here.

AA: So we’ll start out with Phillip. Phillip Watts Brown is a poet and artist after earning a BA in graphic design from Brigham Young University. He earned an MFA in poetry from Oregon State University. He is the author of Boy with Flowers in His Mouth, which was published by Gold Line Press in February, 2025. His work has appeared in literary journals and anthologies, including Ninth Letter, the Common, Ruminate, Nimrod, Tahoma Literary Review, and others. Phillip lives with his husband in northern Utah, where he works as a graphic designer. He’s also a poetry editor for the online literary journal, Halfway Down the Stairs.

So actually, let’s just stick with you, Phillip, at first and have you tell us about yourself personally, and then we’ll move to Andres after that. Can you just tell us a little bit about what makes you, you and what has brought you to the work that you do today?

PB: Sure. So I am from Utah originally, was born in Provo and raised there a little bit and then in Sandy, Utah. I had gone to Oregon for graduate school, and that was a really formative experience to kind of get away from Utah and then to return. I’ve always been very creative, was making art and drawing when I was younger, and started writing poetry when I was probably about 12. So I’ve often been doing both for a while.

I was trying to think about what I would do as a career, and I wanted it to be something creative. I discovered graphic design in my senior year of high school and I thought, oh, this is perfect. And so a creative career that is also more practical. And so, yeah, I’ve been working as a graphic designer for a while, but my path has kind of wandered through getting a graduate degree in English, working as an editor, teaching some English classes, and kind of returned back now to graphic design.

And I just love poetry for ways in which it can take a moment and really look at something with attention and peel back the layers. I feel like I was an attentive child and was always kind of interested in kind of quieter moments, and so maybe it’s natural that I became a poet. So I work now at a university. I’ve worked at a few universities in a row, and I really love and care about education and I stay close to that even though my day-to-day job is the work of being a graphic designer.

AA: That’s wonderful. One question I wanted to ask you, because you’ve both agreed to be on a podcast called Breaking Down Patriarchy, is if you could pinpoint any patriarchal teachings or ideologies as you were growing up? How did you observe patriarchy at play and what is the impact that you feel like it had on you as you were growing up? And I know that’s a big question, but maybe you could pick a few things.

PB: Yeah, I mean, certainly we’ll get into Andres and I both growing up in an LDS context, so the religion of being part of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints definitely has the typical patriarchal structures that I think are in a lot of Judeo-Christian religions, as well as some that are maybe particularly unique to Mormonism. But I would say that I would probably immersed in those and didn’t realize that I was. So there were things about how my family operated or things that happened at church that I probably was less questioning of.

Where I noticed it personally was often more like gender roles; I was acutely aware early on that my interests were what might have been considered more appropriate for girls. And so I felt a tension cause I was sensitive. I didn’t really roughhouse or want to wrestle. I didn’t enjoy sports. And I felt sort of an awareness begin to grow that patriarchy was informing. So, I mean, of course I wouldn’t have used the word at that time, but there were rigid roles and, and that I was falling outside of that. And then certainly as I became aware of my sexuality, I felt further outside of that. I felt that there was an expectation for how a man should be, what boys should like, what I should do as a career, how I should provide for a family, what kind of relationships I should have. I think I felt all of those pressures.

And so that to me feels like a real strong principle of patriarchy. And I think I even was aware that it was different at this context for girls. There was an allowance for a tomboy, a girl who liked sports, and there wasn’t really the equivalent for the sensitive artistic boy. Certainly the word ‘gay’ would then get kind of whispered, and that was something that was feared. And so, yeah, I feel like that’s been something that I was very aware of as a kid in a way that generated a self-consciousness in me. And I feel like as an adult now, that is something that I work against where I try to embrace those things without that shame, try to let go of that and really expand the definition of what it means to be a man.

AA: Wonderful. I know we’ll get a deeper into those topics later in the conversation, but thank you for sharing that as your introduction.

PB: Of course.

AA: So now let’s talk about Andres. Andres, welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy. And I’ll read your formal bio first too. Andres Larios Brown, pronouns They/Elle is a Utah-based licensed marriage and family therapist dedicated to healing for LGBTQ plus communities. As training director and partner at Simple Modern Therapy and Institute, Andres focuses on trauma, healing, and wellbeing for those who feel marginalized or othered. Andres specializes in identity development and reclaiming healing practices for queer, trans, and BIPOC communities. As a therapist of both lived experience and learned expertise, they are committed to helping LGBTQ+ people thrive.

In addition to providing therapy, Andres focuses on creating and facilitating training for therapists and teaches at U of V’s Masters of Social Work Program and U of O’s Couples and Family Therapy Program. They have co-authored a chapter in the Rutledge International Handbook of Couple and Family Therapy, as well as a number of other articles in different academic journals. Through therapy, teaching, training, and advocacy. They seek to bridge the gap between research and clinical practice. They and their husband of eight years live in northern Utah where they spend as much time with family and loved ones as possible.

That is awesome. So Andres, thank you. And I’d love it if you could actually start by telling us about your pronouns, because some listeners may not be familiar with the pronoun ‘elle’. So maybe you can tell us about that and then tell us about who you are.

AB: Amy, thanks so much. Yeah, I think it’s been a really interesting journey and I know that we’ll also kind of get a little bit more to gender and non-binary gender. For me, it’s been this really interesting space of trying to figure out how to make sense of who I am, not only in English, but also in Spanish. As somebody who is a multiracial—my dad is an immigrant from Guatemala. My mom is of Western European or Pioneer Stock—I feel like there’s kind of this really interesting both and, and so in Spanish, those who are familiar with Spanish, Spanish is a pretty binary gendered language, either ending an ‘o’ for masculine or ‘a’ for feminine. And so there’s some efforts to have more neutral or non-binary conversations or engagement with Spanish language by ending an ‘e’ rather than an ‘o’ or an ‘a’. So instead of ‘amigo’ or ‘amiga’, it’s ‘amige’. Instead of ‘novio’ or ‘novia’, it would be ‘novie’. And so elle is also that pronoun that you can use that translates a little bit better non-binary experiences into Spanish.

AA: Wonderful. Thank you so much. Okay, and now tell us where you’re from and a little bit about your growing up and what brought you to do the work that you do today.

There was an allowance for a tomboy, a girl who liked sports, and there wasn’t really the equivalent for the sensitive artistic boy. Certainly the word ‘gay’ would then get kind of whispered, and that was something that was feared.

AB: Oh, what a good question. A big question. I think our journeys are always really complex. Well, I was born here in Ogden, actually raised in California. My parents got divorced when I was pretty young and my mom then took us to California, so I was raised in Central Valley, California in a little bit more kind of rural community. And so I got the opportunity to really grow up with horses, pigs, goats, mending fences; really got to kind of live that life, but knew that I have family here in Utah, so I would come back here over winters or the summer.

After I graduated from high school, I then went on a Church of Jesus Christ, Latter Day Saints mission to Monterey, Mexico, and that’s actually where I got to learn Spanish. I didn’t grow up speaking Spanish, so it’s been kind of interesting to learn it a little bit later. But then afterwards came to Utah for undergrad. I double majored at the University of Utah in Psychology and Human Development and Family Studies. And then that was around the time when I was coming out, so when I was choosing grad schools, I knew that I just needed to not be in Utah. I needed a little bit of a breath from this environment to be able to fully understand myself.

So ran away to Oregon and that’s where Phillip and I actually met was in Oregon. Even though we both have roots here in Utah and lived there for a couple of years. I mean, I really loved my work that I was doing there, but started to notice more and more I was getting a lot of clients who had experienced some form of conversion therapy, whether traditional conversion therapy or conversion light therapy, and was finding that there wasn’t a lot of resources for therapists in working with people from the Church of Latter Day Saints were navigating identity, faith, family that wasn’t maybe perpetuating this idea that we needed to somehow try and make it work, that we could hold both.

And so I decided to come back to Utah, back to the homeland, to kind of the source of my trauma, but to provide really attuned and thoughtful and expansive and liberatory therapeutic spaces for my community. So we were up at Utah state for a couple of years, and yeah, now we’re here in Ogden. And so really the main impetus for coming back to Utah was to do this work with my community at the intersection of faith, religion, identity, and queerness.

AA: Hmm. That’s very brave for both of you because I feel like that can sometimes be the sight of the greatest pain—like you said, it is the sight of trauma. But it is maybe you’re uniquely able to do that work in the place that you know the best and you understand the context the best. How has that been for you?

AB: Oh, I think on the one hand, really beautiful, really meaningful. I knew I wanted to be a therapist when I was 12. And so in a lot of ways I feel like I’m living kind of 12-year-old Andre’s dream. I look very different than what I thought it would look like. And so on the one hand, feel really honored. I hold a reverence for the role that I play in my community’s life and my client’s life. And it’s been hard and healing. I wasn’t anticipating how big of a trauma response I would have. Coming back to the source of my trauma, being around people who had once felt a sense of belonging and now felt really othered. There’s often not the assumption that I was raised in this culture or in this religion. And so sometimes that can feel really confusing for my sense of self to be like, oh, these are my people. I grew up with a funeral potato recipe that was like my families. Right? And kind of just this understanding of the culture, but now coming very outside of that has been really hard, really difficult, and like you said, brave.

Phillip and I talk a lot about how I would love my life to not have to be so brave. I would actually love to exist without bravery being at the forefront. But that has been kind of something that I think we’ve just had to lean into rather than run away, which I think I originally did. Kind of moving into the fire has been healing for me, to also then find community here in Utah, being my full, authentic self rather than a reduced version of myself. It’s also been really meaningful.

AA: That’s really wonderful. Thank you for sharing that. I also actually do want to ask you, and I know it’s a huge question, but the question I asked Phillip too, which is how did you kind of identify patriarchal constructs as you went? How did you observe patriarchy kind of as you grew up? Or in retrospect, how was patriarchy at play in your life?

AB: What a good question. I think some of it is the same, or I’ll say amen to what Phillip had said. So I won’t maybe repeat those pieces as far as adherence or non-adherence, which gender norms and expectations…. One thing that stood out to me is I feel like my mom was my first example of a feminist, which I think maybe she would wrestle with that as a label for herself. She’s very much still connected to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, is very active and believing and finds real value in that worldview and that theology. But being a single mother, growing up in a rural part of California, there was also less maybe rigid or distinct to like: men do this, women do this. My mom was very much in the like, oh, we’re building a fence? We’re building the fence together. She’s always kind of had this more fierce energy, I think, to her. And so that I started to notice more and more as. Growing up, there were certain pieces where I viewed my mom as really strong, really independent, but then certain things we needed, say a priesthood holder to be in our home when the missionaries were coming over or to do certain things. It required maybe outsourcing that patriarchy because we didn’t have it within the home.

And then as my brother and I then started to get to that age where then we had the priesthood or power, it was this real wrestle of feeling maybe this responsibility as young boys to do certain things or to hold certain power where again, the age discrepancy didn’t quite match. And so there was kind of this non-traditional understanding. I felt like I interacted with it as again, kind of this really interesting theme in my life as kind of as an outsider. I saw other families have this more traditional role and it felt like that was celebrated and accepted and our family often felt like, oh, this isn’t quite aligning, and I didn’t quite know how to make sense of that given the power, the beauty, the resilience of my mom.

AA: Hmm, that’s really interesting. Thank you for sharing that. I’ll just add too that because I’m just realizing right now that listeners who don’t affiliate or have never been members of the LDS Church, and this will have to be a whole other episode, but explaining like the priesthood, like the implications of being in a household run by a woman. In the LDS Church boys are ordained, like every boy is just automatically ordained to the priesthood at age 12, and then there’s higher ordinations. And so you get this weird tension where a boy can outrank his mother in authority based on the priesthood structure, which is a patriarchal structure. I don’t think that’s ever come up on the podcast before until just right then. And when you said it I was like, oh, we’ll need to explain that. But yeah, that’s a topic for another day. Thank you for bringing that out.

Well, thanks for those intros. That was already fascinating, but I’d love to dig into kind of the meat of the conversation today. And Phillip, you as a poet are going to share some of your poetry and then Andres will share some of your insights as a therapist, and we’re hoping that this conversation just unfolds organically. But I think where we’ll start is with three poems by again, Phillip Watts Brown. So I’ll have you read your poem, Phillip, and then I’d love for you both to just discuss the themes, anything that you would like to discuss as you read these poems. So we’ll start with ‘Boy with Flowers in his Mouth’ and Phillip, I would love it if you would read that.

PB: Of course. This poem is the first poem in my collection and the poem from which the title for the whole collection comes. Yes. It’s titled ‘Boy with Flowers in His Mouth’.

Everyone can tell

he’s a boy who blooms.

Can’t talk without petals falling,

soft evidence against him.

He bites down on stems

keeping quiet, the taste

both bitter and floral:

a terrible summer.

Shame unfurls in the silence,

his body a greenhouse

flush with desire. A dozen

questions blossom on his tongue.

No one will explain this.

No one will name the flowers.

So this poem came from an image that I saw, actually a photograph of a boy holding flowers in his mouth, and it was just titled simply that. And I thought that was a really interesting phrase. It instantly connected to me with my voice as a gay man.

Often, for whatever reason, our voices are one of the big tells. We, growing up, Andres and I talked about how we were conditioned to be nervous about everything from how we sat or stood or walked. But speaking is tricky. I think you can’t avoid your voice, but I had a self-consciousness that it would somehow out me and reveal something. So I thought about this image of holding flowers in your mouth, a sort of uncomfortable obstacle. And also this blooming quality felt like it connected with the perhaps more delicate feminine quality of my voice. I had the experience that, I mean, I think a lot of boys have before their voice changes where I was confused from my mother on the phone..

But I think for me, what was really difficult about that time period was how much silence there was. There wasn’t a lot of conversation about, oh, you know, you might be going through this, or, you know, asking some questions, discussion at church and at home about sexuality, especially homosexuality was in whisper tones, if at all. Mostly not at all. And so I think the poem is an effort to open into this sort of larger loneliness that I think a lot of queer youth can experience, which is going through an experience and nobody is really helping you through it or nobody is talking about it, which can feel isolating. I know I certainly felt like the only one or I was having this unique experience, and later came to really appreciate finding community. But this poem sits in that early space, that place where I was feeling a self-consciousness, worried to talk, worried to reveal something. It’s like hanging around this really big secret, but no one’s talking about it. And that’s just really tough.

AB: Yeah, Phillip, as you’re talking, it makes me think so much about how as queer humans, again, kind of this fear of some sort of indication, some sort of movement, the way that we sit. I remember early on being asked to check my fingernails and whether or not I checked it this way or this way, depending on whether I looked at a straight on or this way, would somehow indicate femininity, which then indicated a queerness. And so I remember early on being taught to not trust my instincts, to not trust my natural way of checking my fingernails, but to perform masculinity in a way that would allow me to be safe to hide among other representations of masculinity. And so I think there’s a real resilience for us and being able to do that.

And I think so much of the work that I do as a therapist is learning to undo that, to actually shift our relationship with our natural selves, with our instincts, with our impulses, to get really comfy and cozy to return back to self because we’ve gone through so many processes to shift the way that we speak, the way that we sit, or what we like, right? Our favorite bands in middle school and high school, we had to make sure that they were aligned with this appropriateness or this palatable or this acceptable category of existence rather than being able to say, oh my gosh, I love pink, or I love floral, or I love blue, or I love gold. Or, again, being able to really rest in self. So I feel like what’s really interesting is it can be a really lonely experience and it can show up both mentally and physically in again, we feel really at war with our bodies.

PB: Yeah. I feel like when you said performing, that really resonated with me because I thought, oh, that feels like a big piece of patriarchal masculinity is sometimes like performing it correctly. And if you don’t, you are othered or outed. And I think, I love what Andres was saying about authenticity as a contrast to that. I think part of my unpacking is that I’m trying to stop performing. I actually got really good, unfortunately, at hiding, at performing, lying to a degree, not revealing things about myself.

So the work of adulthood and the stuff that Andres does in therapy with their clients is, you know, it’s so much of this taking off a costume almost and trying to be more authentic. But yeah, I think it can all feel very performative. And now on the other side, I sometimes look at, especially like straight men, and I think so much of this can feel like performative or I wonder what they would do if they felt greater allowance.

AA: I wonder that too. And I’m curious too, whether as you started to kind of live more authentically and try to trust your instincts, for example, if you are going to check your fingernails, like okay, I can do it how I want, or I don’t have to alter my voice or be conscious of my gestures or my, the way I carry myself. Did that feel really scary at first? Because I think you are doing those things to keep yourself safe. Right? So I wonder if like you had it, you’re trained mentally and like somatically in your bodies to keep yourself safe. Was it scary to just let yourself be out in the world where you might not have felt safe before?

AB: Yes. I think the short answer, yes, and I think that’s the tension; is we’re often asked to sacrifice authenticity in order to feel safe. That’s the tension that we feel in a lot of ways. Phillip and I talk a lot about this, where the more visibility queer we are, the less safe we feel in this world. The more we allow ourselves to be vibrant, to hold hands in public, to share that we’re a gay relationship, to be soft in ourselves, the more at risk we are for potential danger. And yet I think part of it is just that cost is too high to maintain that safety sacrificing authenticity. I think it harms our soul deeply and profoundly and ongoingly, and so we maybe get to honor our soul’s healing while also maybe interacting with the real life implications of the danger of being queer in public.

Especially right now feels increasingly scary to be visibly ourselves, but I think at this point we don’t have any other option but to be our authentic, visible selves.

AA: Thank you so much for that. Did you have something to add, Phillip? Please do.

PB: I mean, mostly just again, amen to all of that. I was going to just say that it’s a unique experience to feel bravery around things that other people may not think about. I was talking to a friend once about holding hands in public and saying that Andres and I actually rarely do, almost never, and there have been a few places where I was able to do that, and it felt brave and she remarked how she holds hands with her husband without thinking. It’s sort of an almost unconscious thing. She just reaches for his hand. For me, it’s brave.

So yeah, it’s kind of a strange thing to feel brave and require courage to maybe get dressed and go out your door to hold hands with somebody to say what you like. I mean, really when I got asked like, oh, what music do you like? That was like panic instead of…let me answer the question. Some people are like, oh, I can’t choose a favorite. That’s the biggest thing to deal with, and I still will have sometimes just a moment of self-consciousness. So I think we are being brave and we wish we didn’t have to be so brave, but I think Andres and I have both experienced the freedom that comes from being a little more courageous.

the more visibility queer we are, the less safe we feel in this world

AA: Thank you so much for sharing that, and I’m hoping that any queer listeners will feel validated and encouraged and heartened to hear you say that, and any cisgender straight listeners who haven’t considered what that would feel like. I’m just grateful for that opportunity to think about that and try to take on that perspective and consider the privilege that it is, especially as you talked about, and especially in this poem, that the line that…oh, the whole thing was so moving to me, but “can’t talk without pedals falling / soft evidence against him.” That’s the line that for me, I thought, I’ve never had to think about it. I’ve never had to think about how my speech could betray me. I mean, my patterns of speech or the tone of my speech could betray me. And so thank you for that invitation to have greater empathy for our listeners who may not have considered that before.

Let’s move on to the next poem. This one…Wowsers. I mean, they all hit so hard, Phillip, I’m just blown away by your poetry. But this one is called ‘Sacrament’, and I think we do have a lot of listeners who are not familiar with LDS culture. So if you could explain a little bit of the context that might be LDS specific and then read the poem, that’d be great.

PB: Of course. Thank you for the kind words about my poems. So yes, this poem has to do with the sacrament, which for an LDS context is our version of communion. And basically, it’s those sort of biblical symbols that are supposed to represent the body of Jesus Christ. Typically it’s bread and wine; for an LDS audience, it’s water. And we’ve already talked about how young boys are ordained to the priesthood and at different ages you are given different assignments. And so when you are 12, you get to pass the sacrament to the congregation. When you’re 16, you get to bless the sacrament and you’re up there at the front. So I had the experience of doing all of that. Or when you’re 14 you get to prepare it. It was all these sort of different ages, but it was all centered around this ritual.

And yeah, you’ll see the image that really stuck with me was…and I had this thought when I was at that age preparing the sacrament, is you would kind of drape the table with a white sheet or a tablecloth and then lay out these trays and then you’d put the bread and the water, and then you put another tablecloth or sheet over the top. And I was told at one time that it represented Christ’s body, so it almost looked like a body under the sheet. But straightening it…and I was a little perfectionist and I wanted it to be just so…that felt very akin to making a bed. And so for me, that really made this juxtaposition that I thought was really rich. And so that led to this poem.

Sacrament

Drape the table with a white sheet

as if making a bed, straighten the hem.

Ease the bread from its plastic sleeve,

placing in each tray a soft slice.

Christ’s body — yes, only bread, but still

this idea of a man in your hands.

During the service older boys break

then bless the bread, a lesson

in how men handle one another.

They bow their heads after it’s done.

When you take the sacrament,

let it rest on your tongue like a silence.

Instead of Jesus, you contemplate

those boys, their smooth jawlines

resurrecting inside you a longing

you’re afraid they’d crucify you for.

Some future Sunday, you will know.

You will touch the warm bread

of another man, passing yourselves

back and forth beneath the sheets.

Bowing with desire as with reverence

you bless each other’s bodies,

seeing how they’ve already been broken

in the name of God.

AA: I was stunned by this poem. It’s so powerful. And also, if I can say this, it struck me…I was kind of reading with kind of double consciousness thinking of how a devout member of the church would read it, and it struck me as being quite sacrilegious. It was so beautiful and it broke my heart, but I was aware of like my formal self reading it and associating those what devout members think of as sacred ordinances with what Mormons would call the profane, which is sexuality, and then even more so homosexual sexuality. So I guess my first question is what did it feel like to have this poem come to you? And as it was coming forth from you, was it scary or uncomfortable to write? And then I thought like, oh my, has his mom read it? Like, who is your audience? What was that like for you? If I could ask that?

PB: Yes. I love that question. It’s always a little strange how poems, once they’re all done and I’ve had a little time, they feel kind of closed up and that they feel as if they’ve always been that way. But there was a time where I was doing revisions on this poem and trying to figure out how to broach the topic. What’s fascinating is I was writing from my experience, which it could feel to some that this poem, conflates, or you know, kind of brings together a religious experience and a sexual experience. But the hard thing was for me, at 12 years old, starting to have stirrings of my own sexuality…that’s what was happening. I was sitting there and I was looking at these 16, 17-year-old boys, and they were attractive to me. And so I’m sitting there in church, having a religious experience that was inherently underneath was having strings of a sexual experience.

And of course, if sexuality is profane, then this feels sacrilegious. And that was certainly the message that I got. So I actually think that writing these kinds of poems in this collection has been an effort towards healing of actually saying “No. Sexuality is not profane. There’s nothing wrong with being gay.” And in fact, I remember hearing a lot that, oh, sex is just so sacred. That’s why you save it for marriage. And no one mentioned me having a husband and they wouldn’t have said that that was sacred. But in this poem, I think I’m trying to say, look, it is sacred. It’s just as sacred. And so I recognize the way the poem could be received, and I think that’s what lends the poem some power. But I think I was writing it for myself and it was 1) it was an experience I was already having. Those two things were right next to each other every time I was at church. And 2) it speaks to how I’m trying to experience sexuality and actually for that matter. The other side of the coin to see spiritual, religious experiences as being open to the body and to being sensual.

And so, I don’t know… those go together more than the religion allowed me to believe. So I think it’s been a healing experience. Did I have a little bit of apprehension? Yes. When I first published it, it was in an individual journal and sharing that on Facebook, saying, oh, I have this poem published. I was nervous. A lot of people have responded to it, and I know a lot of writers talk about the value of something risky, something that’s vulnerable, helping us to work towards something that ultimately is powerful. And I think that’s true with this poem.

AA: I do have to say I had such a visceral reaction when I read the poem and it kind of like took my breath away. The word that came to my mind is just art. Like that’s art. And it is that riskiness. And there’s something I was going to say political, and I don’t know if you object to that label, but there’s something beautiful and powerful and personal, but there’s something political about it. And then that integration in a way that is going to ruffle some feathers and maybe be seen as sacrilege. I just thought of Asher Lev in, My Name is Asher Lev, and I was just like, oh my gosh. That was such a powerful piece of art for me. So, Andres, would you like to share some thoughts about this also?

AB: Yeah. I think first and foremost, I think that it’s one of the greatest honors of my life to be married to a poet. I think that there’s something really beautiful about kind of hearing such a beautifully crafted representation of my experience and of somebody that I love so much. So in a lot of ways I’m so proud of Phillip for this poem, for being brave, for quote unquote risking. Because I think so much of us, so much of our upbringing is taught to not…Blessed are the peacemakers where we don’t stir the pot. We don’t kind of disrupt. And so I feel really proud of Phillip and I think it’s been this really interesting piece that Phillip already kind of talked about, which is how we’re taught that our sexuality disqualifies us for divinity. That we’re taught that, again, kind of going back to that other poem as well, that who we are betrays us, puts us at risk. And so I think for many of us, we have this really complicated relationship with deity, with divinity, where we feel like our queerness, again, moves us out of qualifying for that not being worthy.

But I think what Phillip’s talking about is so much of, again, the work that I try to do in myself and with other people is actually we claiming that and saying our deviance actually is our divinity. That actually, that which society or our culture has told us is bad may actually be a spiritual access point, that actually what we as queer people get to do gets to be expansive and beautiful and reverent. It doesn’t have to be an either/or. It gets to be a both/and. And I think by doing that, there really gets to be, again, this real celebration of self which we were taught to fear at worst and at best tolerate, and I think what we try to do is celebrate that. Right? That I feel so grateful that I am queer. I get to navigate the world with these identities and with this gender and with this sexuality, rather than, again, continuing to say, oh, well, I prefer if I could or if I could go back, I would change it that way. I would have better access.

I actually feel like I have deeper access to divinity as I embrace my authenticity, my congruence, and my queerness than I did when I was trying to conform or contort myself into some version that actually wasn’t celebratory of a divine maker.

AA: Hmm. That’s so beautiful and powerful. Thank you so much for that. Well, we have the great privilege of hearing one more poem from Phillip. This one is called ‘Meditation on a Gumball Machine’.

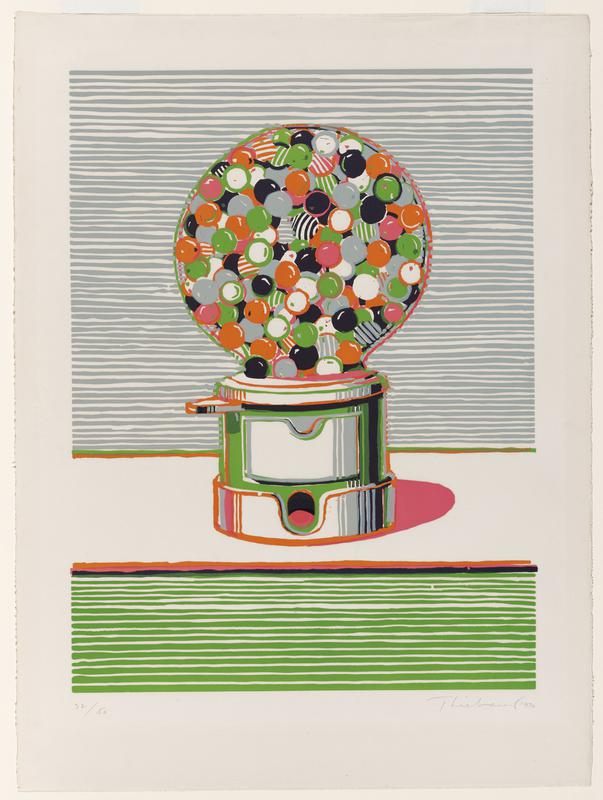

PB: This poem was initially inspired by the visual artist Wayne Thiebaud, who paints pieces of cake and pie and sort of these pop art things, and he has a lot of fabulous paintings of gumball machines. So that’s where I started. And I ended up kind of surprised at where the poem took me.

Meditation on a Gumball Machine

Circus of circles, rainbow dispenser,

paint swatch jukebox, a whole birthday

in a snow globe. The cosmos packed

with bright planets, stars, more shades

than they explained in school. Green, orange,

blue, and violet giants next to red

and yellow suns. The nucleus of one

massive atom or one boy’s head

hoarding grenades.

Have you ever felt so sick of secrets

you’d spend every nickel to be emptied,

a glass moon with nothing to hide?

People think grief only comes in blue,

but what about the hot pink losses?

The white regrets glowing in the dark.

Maybe the blues are really sky souvenirs

from an afternoon you walked home to yourself,

sugar on your tongue, every cell inside you

shiny and solid. Listen,

the love you tasted that day is worthy.

Whatever sweetness your parents said

you couldn’t have,

you can have.

This poem is a really meaningful one to me. As you work on poems, a lot of times they stop surprising you. They become really familiar. This one I struggled to figure out how to end it. And I remember the day that I figured out this ending… I kind of came upon it and my own poems ending made me emotional, made me a little teary, and that doesn’t usually happen. And so it felt really special and even as I was reading it today, I felt a little emotion come up. So it feels like a resonant poem for me. And I think this speaks to what I was already saying about the other poems, that this is an effort towards healing. So this reassurance, I mean, I even am speaking in second person as if talking to myself at the end saying, you know what? You’re okay the way you are, who you love, sort of imagining in the context of this poem, perhaps a kiss was had or some experience was had earlier in the day. Hey, that’s worthy, that’s equivalent. And then this notion when I circled back to gumballs and I was thinking of those machines that are at the front of the grocery store and kids are pining for the treat that the parent says, no, we’re not going to have that. And I mean… I am not a parent. I understand the difficulty involved in all of that, but there was something there that spoke to me with this kind of forbidden existence. And so to tell myself, you know what, whatever I was told that I couldn’t have or shouldn’t want is okay.

And it was fascinating to me to go back to the beginning where I thought I was just talking about gumballs, but actually the rainbows, the birthday, the universe being a little different than it was originally explained. All of those have whispers of some queer theme, and so I realized the poem in this case was kind of wise and knew what it needed to be before I did.

AA: For the record, I want to say I also cried at the end, that line. I totally got that and I got the gumball reference of like the kid wanting the gumballs and that line, “whatever sweetness your parents said you couldn’t have, you can have.” I sat with it and cried myself.

PB: That’s so lovely.

AA: And Andres, what are your thoughts about this one?

AB: I’m going to continue with the emotions. Yeah, I don’t think that there’s been a time where Phillip’s read this that I haven’t kind of felt this emotion. Again, I think it’s this resonance and powerful symbol. The main thing kind of top of mind is I remember the first time Phillip read this to me. The line that stood out to mean was “the hot pink losses” that kind of just, boom, hit so deeply. I think my experience as a gender diverse human, as somebody who has always felt a connection to femininity, but has often been restricted from being able to get access to that femininity and how hard that’s been for me.

I remember early on as a little human, really wanting a Holiday Barbie, that was what I wanted: 1998 Holiday Barbie was just like a big Holiday Barbie for me. And I remember sharing that with my parents and them being told that I didn’t have access to that, that I couldn’t, that that wasn’t for me and how much I had to grieve that desire, that connection, but then being told really distinctly that I couldn’t. And so I think that for me, there’s lots of a hot pink losses. There’s the grief of what I didn’t have access to as a gender diverse human that didn’t know that they have language, but continually being told, no, no, no, no, no, no, no. And I think in a lot of ways, the grief that many of us as queer people have, which is we’re never going to get that childhood back. I’m never going to get that experience as a little human of opening up a Holiday Barbie and feeling joy and celebration. That’s something that I get to give to myself now, but I carry with me the wounds of all of these hot pink losses.

AA: Thank you for sharing that. My goodness. We’re going to switch gears now, but before we do, I’d love it if you could tell us, Phillip, where can we find all of your poetry? Because listeners, I mean the three of us are able to read along and see the words and it’s really powerful to hear them, but I think people will want to know where they can find and read again and again. So where can they find your poetry?

PB: Sure. I have a website that’s probably the easiest place to get to phillipwattsbrown.com and make sure there are two Ls in Phillip. My collection Boy with Flowers in his Mouth, is available through the publisher, as I mentioned it was Gold Line Press. There is a link to that on my website, so that might be the easiest place. I’m also on Instagram @phillipwbrown, and there’s a linktree with links there as well. So hopefully you can find it if you’d like to. And many of these poems were published individually in online journals before being collected in the book. So two of the ones that I’ve read today are online and there are links to those as well.

AA: Wonderful. Thank you so much. And there’ll be links also on our website in the, the transcription of the episode too. Thank you so much.

Okay, we’re going to switch gears really quickly and ask Andres to take the lead for the next section. And we were talking a little bit before we did this episode about some topics that I’ve never addressed on the podcast before and I’ve wanted to, so I’ll introduce it with this little anecdote cause I’ve had this come up for me recently. I have a friend who’s a gay man. I’ll say it’s not Stacey Harkey, just for people who know I’m friends with Staecy and you’re like, oh, Stacey, it’s not, he lives in California. This is a different guy and a good friend of mine, a really, really good person. We were working on a project together recently. I noticed that he was asking me to do a lot of the behind the scenes work, like literally making copies sometimes and just kind of like the grunt work for the project. Also, he was getting paid for our project and he didn’t offer to let me have a cut or, you know, share what he was getting paid for this project.

And it wasn’t really about the money. It’s a privileged position that I didn’t need the money. That’s not why I was doing the work. But it did start to bug me a little bit. And I mentioned it to one of my daughters. I was a little confused and she’s like, “mom, just because a man is gay doesn’t mean he’s not sexist.” And I was like, oh, I guess I kind of did think that. And it was kind of a funny thing for me to realize. So I have a two-part question. First of all, is my daughter, right? Have you seen misogyny, or benevolent patriarchy among gay men? And then the second question is, I have heard that patriarchal dynamics can show up even in same sex partnerships or in queer partnerships, not just in cis-het partnerships. And so Andres, you called it replicating power and misogyny in rainbow colors. And I was like, whoa. Oh my gosh. Please unpack that. So I’ll take my question off the air and you can just go for it.

AB: Oh yeah. think the short answer is yes. I think misogyny, sexism, patriarchy, power is alive and well, unfortunately in queer communities. I think you were alluding to a lot of the wisdom that we know, which is queerness does not absolve us from replicating harm. I think with queer men, maybe specifically gay men cause I think terms like ‘queer’ and ‘gay’ are also really fascinating and really interesting, which is probably a whole episode in and of itself. But I think with gay men specifically what we see is that there’s such a proximity to privilege that often there is a wan disqualifier from the world being designed for you, these structures being really beneficial for you. And so while you may have to lose some privilege in maybe the sexuality, there’s lots of other privilege in a lot of different areas that we see that it’s really difficult for people to want to sacrifice that privilege in order to even that power differential.

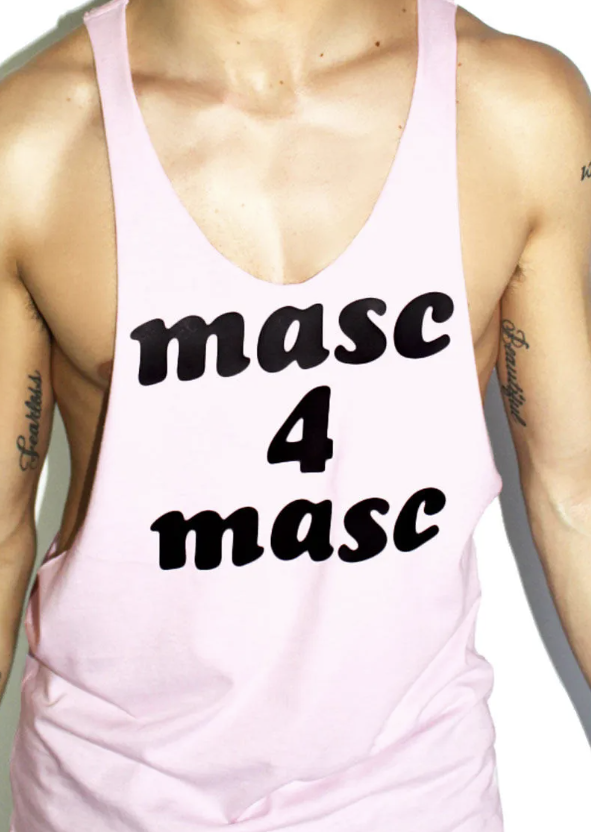

In order to disrupt the patriarchy you have to be willing to remove your access to some of this privilege. And so I think that we see that it’s alive and well. Sometimes we see that it’s even bigger in queer communities. You often hear about stories like masc4masc; so masculine gay men being only interested in having sexual or romantic relationship with other masc men. We’ve learned to fear femininity. We’ve learned to really seek after maybe even hyper-masculine presentations. And so that can then reinforce again, misogyny in being even more fearful of femininity because of maybe the harm that you’ve experienced, the trauma or again, that proximity to privilege.

AA: That’s really interesting. So I’m sure it doesn’t always, but like…your sexual preference and stuff that can be completely just natural and benign. But sometimes that can come from a bit of, like you said, kind of the pushing away of the femininity, which can be misogynistic in a way. Right?

AB: Yeah. I mean, it’s so interesting. We were taught, well, I think in patriarchal structures we’re taught that femininity is less than, right? That femininity is something to be feared, to be exiled, to be dominated over, right? And so I think it just in any sort of patriarchal framework, but going back maybe to what Phillip was talking about in these different poems. We as queer people, as queer assigned male at birth people, are also taught that whatever femininity is within us is going to betray us. It’s going to lead to our non-belonging, it’s going to lead to our rejection. And so we maybe have extra fear wrapped into, oh, if there is an aspect of femininity, I need to really create these structures to remove myself from that. Which again, what we see is that coming out doesn’t mean that suddenly we’re then really good at being introspective and unpacking and processing and healing.

And so I think, again, a lot of the work that I do is also with maybe more hyper masculine gay men in really unpacking our trauma that some aspects of how we navigate the world maybe is a result of this. Trauma isn’t an organic, innate piece of our sexuality, of our gender, of our experience.

AA: Hmm. That’s fascinating.

PB: It comes out too, in simple preferences. Some people will say, I care for this, or I don’t care for this. The example Andres gave of masc4masc, which is this kind of phrase that gets thrown around. I think some of those people would say, I’m just attracted to masculine men. I’m just not attracted to a feminine guy. And they sort of say it in a really unquestioning way, but I think that’s where there’s this like…What’s underneath that? And I know for me, the fear that I had about acknowledging what music I liked was because there was a fear around femininity and being perceived as feminine. So I think you can see that play out and if there’s some investigation, sometimes you realize where some of that comes from.

And then conversely, I’ve seen some queer people actually really champion the feminine and some of the attributes that we have stereotypically associated with femininity as a source of power. And there’s a reclaiming an unapologetic femme energy. And that’s been really lovely to see. And I find myself… I mean, I think Andres is a good example to me sometimes of embracing the feminine. And I’ll feel kind of in between as I feel my conditioning kicking in. And I see examples of a possibility and I’m invited to reflect on where these preferences might come from. And I see more and more the limitations of the patriarchal structure and the liberation possible with being open to femininity and not making it the big scary possibility to be found out as having anything feminine and now I sort of am more proud of those things or try to be.

AA: That’s wonderful. Ah, it’s great. I’m reflecting too on the specific anecdote that I shared too, that it was, I mean, the things that I noticed were just kind of gender roles, probably just unexamined gender roles of not thinking to share the payment, like the compensation, and also me doing kind of the behind the scenes work. I did it without even thinking about it for a long time too, because I also have been conditioned to do behind the scenes work for free as a woman. So I didn’t even notice it. I don’t think he noticed it, and I didn’t notice it until I did notice it, and then I was like, oh. I kind of like maybe relied on him to be the one to handle that, and then I thought, no, I need to be the one to push back against that.

But anyway, this brings up kind of my second question, which is in a relationship where you said, again, Andres, that sometimes it can replicate power and misogyny in rainbow colors, like just the way we’re trained, the way we observe adults in our childhood, our whole lives, that even in queer partnerships, those things can manifest themselves. Could you talk a little bit more about that? And if I can be so bold, I might even ask you if any hierarchical dynamics have come up even in your own relationship?

AB: Yeah, please, please. I think one of the things that keeps coming up for me is, and I don’t mean to be trite, but I think it would be silly of us to believe that we can grow up being socialized in a certain way and not have it impact us consciously and subconsciously in uninterrogated ways. And so Phillip and I will often talk about—I mean, bless Phillip. I think being married to a therapist is an experience in and of itself—but we often talk about not if these things are going to show up, but when and how. So, rather than feeling like somehow we’ve elevated ourselves out of that, or we’ve removed ourselves completely from that, being really mindful of it’s going to show up and it’s going to show up in surprising, unexpected ways. And it doesn’t matter how much work we do. We need to be prepped and ready for when it shows up. What are we going to do with it?

In order to disrupt the patriarchy you have to be willing to remove your access to some of this privilege.

And so I think that’s been a key piece of Phillip and I’s relationship. For better or for worse. Bless your heart, Phillip. But I think it was really interesting. I think maybe the main area where this shows up, I mean, I don’t know if this quite answers your question, but when I was coming out as non-binary, I think that that was a really interesting experience for Phillip and I. We had gotten together as two gay men and really kind of aligning with kind of being a gay man myself. The security and the connection of having a relationship with Phillip and Phillip’s beautiful energy, I think then created an environment where I really got to explore, or quote unquote ‘interrogate’ this part of myself that I had always attached to maybe being gay but hadn’t, again, going back to those hot pink losses, had instilled in me such the strong, no, no, no. I can’t explore that. I can’t open that up. There’s too much hurt. So as soon as I was able to do that and as I was doing that, that then created this really interesting process for Phillip and I to talk about what does this mean for our relationship?

Oftentimes you talk about gay male relationships as two men, and some of the like real beauty and some of the difficulty of having two gay men having extra masculinity in a relationship dynamic where I feel like for Phillip and I, we then had to look at what does that mean if femininity is a bigger part of our relationship dynamic than maybe originally we had anticipated. And in some ways it also feels really silly because a lot of the maybe straight memes also fit really well for Phillip and I. My hair gets everywhere and so Phillip’s finding it all in like these different places or it takes me so long to get ready and Phillip’s like, five minutes, I’m ready to go.

So we see these really interesting parallels while also having this lens of maybe queerness and how we were both socialized in masculinity as this kind of key piece. So I think that’s what was coming up for me. Phillip, anything you’d like to add? I feel like I tangented away from the question.

PB: No, I mean, I will say what you’ve already brought up is that there are gender roles in relationships, and I do think queer people often get the annoying question of like, who’s the man? Who’s the woman in the relationship? Because there’s such a reinforced sense of that, that there can only be those two things. One must be this and one must be that. I always thought, well, what I love about a relationship being queer is everything gets to be custom or unique. Actually, Andres and I saw this the most when we got married because with weddings there are a lot of templates and there are these traditional rituals that align with gender roles. And so a woman is walked down the aisle by her father, and the groom goes first and she comes towards him. Well, Andres and I said, what do we want to do? Who walks down when and where? And it felt at times a little hard that we were without a template because wedding planning is difficult, but it also really opened it up to whatever it is that we want to do. And we ended up both walking together down the aisle. I think that that is just a really lovely part of our relationship.

But I think like Andres was saying, we were raised in a way that we are sort of steeped in these structures and so we can have some of those thoughts. But I feel like the way some people talk about marriage as a really intense growing experience, you are shown a lot of your weaknesses, you’re asked to kind of be better than you are and learn and grow, and you grow with another person in a way that’s hard to do on your own. I would say that queerness and queer relationships in a similar way, they’re a parallel. They require thinking about things that maybe in straight relationships, people can go a while without thinking about, and I feel like Andres and I have to think about these things.

As Andres sort of blossomed into this non-binary identity that has added in extra nuance, that is different even than some of our gay friends who are married, their relationship, our relationship might have some differences, but yeah…I know I have to be aware the way anybody in a relationship should be aware, like, am I bringing in some patriarchal paradigms? And maybe if I do something, regardless of who my partner is, I could be guilty of those things or I strive to move away from those things. But it is really fascinating because it think I might have thought early on like that, that’s not really going to be a thing because I’m not oppressing my wife or I’m not doing things in that same way. But instead I think that Andres and I have actually arrived at an area where there’s really the possibility for that and there’s always the effort to be more aware and to navigate it together. And it’s just a really interesting layered experience to be in a queer relationship.

AB: We are not perfect by any means. Right? And so this is ideal, right? I think we still have to navigate this ongoing, again, kind of this piece of not if, but when these pieces of… I know sometimes Phillip and I kind of navigate explaining something or overexplaining something, or assuming that one of us doesn’t know something, maybe really basic: is that mansplaining? How do we make sense of that? Sometimes it feels like very much yes. And sometimes it’s like, no, I just wanted to help. And so we’re I think ongoingly trying to unpack that and be really mindful of it and not fall too much into this either/or.

I know early on Phillip tells the story of…I grew up on a farm and so I feel like I am very much like I can kind of give messy, get into the dirt. But early on there was I think a dead rat underneath Phillip’s car and Phillip was kind of freaking out. He didn’t probably know what to do and I was like, I got this. And so I go and I was able to take care of that. But I think for us, again, it’s that value of being able to be a both/and rather than either/or, that our masculinity doesn’t have to sacrifice femininity and femininity doesn’t have to sacrifice masculinity. We get to hold them together and celebrate them both together. not as mutually exclusive but interconnected.

AA: Brilliant. Those insights are just so helpful, and I have learned so much from both of you through this conversation. I’ve been deeply moved and I am so grateful for this conversation. I’m wondering if we can close by having you share some action items. We’ve been doing this at the end of each episode this season, so if you could leave just our listeners with one or two action items, maybe for listeners who are queer or identify on the LGBTQ+ spectrum, and then listeners who are not, because there may be different calls to action for different groups.

AB: You know, it’s interesting. I think that there’s maybe lots of calls to actions, but the one that stood out the most, and it actually feels like it’s for both members of the LGBTQIA+ community and those outside of it is maybe an invitation to reconnect with authentic self. I think so much of our world asks us to be reduced, restrict, and repressed versions of ourself, and I think that that can lead to a lot of maybe the harm that we replicate in our relationships because of a harm that we have in relationship to self. And so my invitation, my hope, is that we can move towards more authenticity, more congruence. I think what we see is authenticity invites authenticity, and so if we could be in a world with more authentic us, I think that we could also heal.

PB: I feel like my call to action is more aligned with my identity as a poet. I think that poems often highlight symbols and metaphors and things that carry a little bit of significance and weight. In the poems that I read, it was gumballs, flowers, bread, the sacrament. And so I guess I would encourage people to, first of all, notice the things around you that speak to you and are your own private metaphor or symbol. And I think maybe in the context of this podcast, to maybe think about what is the symbol of your gender or your sexuality. If you were to write a poem and… hey, maybe that’s a call to action too, you could try writing a poem. But if you were to write one about a part of yourself, rather than just trying to describe your anxiety or to write about your sense of what it means to be a mother, or your sense of what your sexuality, whatever it might be, what happens if you reach for a metaphor? What’s an image that speaks to you? I think for me, reflecting on these metaphors, I’ve learned things about myself by writing the poem. So it might be really interesting as you come up with an image or a symbol, it might reveal to you something about yourself.

AA: Fabulous. I’m going to do that. I used to love writing poetry in college—I was in English undergrad, and I think it would be wonderful for me to go through that exercise and do that more often. So thank you both again. Thank you for those takeaways, for those calls to action, and thank you for the work you’re doing in the world and for being on breaking down patriarchy today.

PB: Thank you.

AB: Thanks so much.

our masculinity doesn’t have to sacrifice femininity

and femininity doesn’t have to sacrifice masculinity

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!