“What if I had spent my whole life praying to a woman?”

Amy is joined by Breaking Down Patriarchy collaborator Celeste Davis to discuss her late-blooming into feminism, taking up space, re-writing the marital script, and how we can all build better relationships by holding love and accountability in equal measure.

Our Guest

Celeste Davis

Celeste Davis is the writer behind the popular Substack ‘Matriarchal Blessing’. She is a certified spiritual director through the Chaplaincy Institute, specializing in LDS faith transitions. She lives in Spokane, Washington with her husband and four kids.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy, I’m Amy McPhie Allebest. For today’s episode, I’m going to start out with a little story. It’s a true story, because it’s about me. And this is me in about September, maybe this past summer, a few months ago, in late 2024. I was starting my second year of my PhD program, and also still running the podcast and running the YouTube channel and the social media. And I love all of those projects so much. I’m also a mother of four and I’m married and have a bunch of relationships that are important to me, and it got to be too much. And I thought, “I’m going to have to cut something.” But I very much did not want to because I love everything I’m doing so much and it’s so important to me. So I was talking with my husband one night and I said, “I think that to save the YouTube channel,” which I really, really, really wanted to, I did not want to stop, “I’m going to need to hire a writer. That’s the only way I’m going to be able to manage everything.” And I was talking to my husband and saying, “I just don’t know who could be the writer to take that on.” And I said, “You know who I would love to get? My dream person to collab with would be Celeste Davis.” Celeste is a writer that I’ve been following for a long time. I’d seen her on a podcast episode also, and just thought, “this woman is brilliant.” And so I had her on the podcast to do an episode and just thought, “Yeah, I so respect the way she thinks, the way she writes.” So we had that conversation, I went to bed, and in the morning I woke up with that top of mind, was my first priority was to email Celeste. We had not really chatted except just to have her on the podcast. And I was going to email and say “is there any way you would ever be interested in maybe collabing with me and maybe writing for me?” And in my inbox was an email from Celeste Davis to me! And here she is, the fabulous, amazing Celeste Davis, to join me on a whole podcast episode. Maybe we’ll start by having you tell this story from your point of view, Celeste.

Celeste Davis: It’s such a miraculous, happy story. I’m happy to share my side of it because this is really a match made in heaven both ways. We’ll get to more of my story about my feminist awakening later, but one Amy McPhie Allebest plays heavily into that personally for me. And I am a writer, I’ve always been a writer, I love to write. And early last year, 2024, I was thinking about branching out as a copywriter. And I was thinking, “Who would be my dream person or company or brand to write for, that wouldn’t be hard at all for me to just believe in their vision?” And top of the list, it was Breaking Down Patriarchy. I was like, “Gosh, she probably doesn’t need a writer. She’s doing podcasts and YouTube and all of this stuff.” So I wrote down that that would be my first choice, but then I never reached out. And then I reached out in September because I was thinking about starting my own podcast, which I never actually did. But anyway, I did want Amy to be the first guest. So I wrote her an email being like, “Do you want to be on my non-existent podcast?” And you were like, “Funny timing! Can we hop on a call?” We hopped on a call and you were like, “You can say no.” And I was like, “Yeah,” right away I was like, “I don’t need any time to think. I will absolutely write for you.” And we’re happily skipping into the distance together.

AA: The rest is history. True. And hopefully listeners are watching that YouTube channel because I’m really, really proud of it. I’m so grateful for it. And if you have been, you’ve been seeing Celeste’s work, because Celeste has been writing episodes for the last little while and it has been a dream collaboration. Yeah, I’m so happy with that and so grateful to be chatting with you more, and becoming friends as well has been really, really fun. And such a fruitful meeting of minds, I love all of our conversations and I learn so much from you. Today I’d like to do this episode a lot about you and your story and some of the lessons that you’ve been learning along the way. Why don’t you start us off at the beginning, Celeste? I’ve heard you describe yourself sometimes as a late-bloomer feminist.

CD: Very late in my life.

AA: Start as early as you want and just tell your story.

CD: Yeah. So, first off, I do write on Substack. I write about patriarchy, which is why this is a good collab, because I think about it all the time. And I think one of the unique perspectives I bring to the discussion of this is having such a fresh perspective because it’s not been that long ago that I’ve had this patriarchal awakening. It’s fresh, so I feel like I view the whole thing with such fresh eyes because I was taught a tale that was completely the opposite, that patriarchy isn’t a thing and that everything’s fine and everything’s equal and “what are you complaining about? It’s fine.” And just for me personally, I was born and raised in the LDS church. I was never a Mormon feminist ever. I mean, until the very, very last year I was in the church, maybe. But not only was I not a Mormon feminist, I was annoyed by the Mormon feminists. Sorry to say, but those stereotypes sunk deep into me that feminists were just whiny complainers making a big deal out of nothing. I just thought that genders were supposed to be separate and have their own unique contribution to the world, and I really believed what was taught to me that we’re equal but we’re different, we just have different roles. So I completely bought in, hook, line, and sinker, into all of the patriarchy that was sold to me. I was like, “Sounds good to me!” And yeah, I did all of the Mormon things a Mormon girl is supposed to do, happily, loved it. Went to BYU, served a mission in Slovenia, got married in the temple, had four kids, all of it fine, fine, fine, fine, fine.

And in fact, I was so bought in that, you know, in the LDS church, we have a history of polygamy. And for a lot of women, this is a secret wound, a pain point, they have to swallow this thing that they think is unfair or unjust. How could a God do that to women? And we still have it in the afterlife even though we don’t have it now. It was never an issue for me, which is embarrassing, honestly. I mean, not until the very end. I wasn’t one that was always in pain over it. And in fact, I can remember a conversation with my husband when we were first married and he was like, “I just could never take another wife in heaven. I just want to be with you.” And I was like, “Well, you’re going to have to, sorry.” Yeah, it’s just like “God wants you to, so get over it, bud.” I was just so bought in. And I even got a master’s degree in sociology. I mean, it was from BYU, but I think the most progressive place on campus is the sociology department. And even then, every single class and lecture on feminism, I would come home so annoyed. And I never on purpose took any of the sociology of gender classes ever because it was so annoying to me to hear my friends and colleagues and teachers have this be a hot-button issue for them, the lack of equality. I was like, “What are they talking about? Of course we’re equal.”

AA: BYU was too liberal?

CD: Haha, yes! I know, I was really annoyed. I was really annoyed by the feminists and I just didn’t agree. I thought we’re fine and in fact everyone would be happier if we just accepted our role as mothers. Embarrassing, actually, but I’ve come a long way. Anyways, so my feminist awakening was very long and slow and arduous, and once I started opening my mind to equality in other realms, it kind of snowballed at first, seeing how unfairly some of the progressive members were treated at church, especially around LGBTQ issues. That kind of snowballed for me, racism was in there for sure. In my master’s program I had a really big awakening around race inequality that I wasn’t aware of, and that became an issue. But yeah, feminism was like the last domino for me. And even when I left the church, I wouldn’t have put it in my top five reasons for leaving, which is rare as a woman. So when I say late blooming, I mean– and I left in 2020. And I can remember a book club read Neylan McBaine’s book, Women at Church, and none of it bothered me. I was like, “Oh, women are bothered by this. Huh. Okay.” But it didn’t bother me. And now every one of those issues is like, “Ah! It’s so unequal!” But at the time it just didn’t bother me. And then after I left the church, that was a time of worldview vertigo, almost comatose, of everything I thought was put into question. About not just religion, but everything in the world by politics and government and everything. And so I started reading more and thinking more and being like, “Oh, wow. Yeah, the Mormon church was actually really unfair to women. Huh.” And more and more, month by month, I’d be like, “No, yeah, really. But wait, no yeah really!” I had stories, and I was like, “That wasn’t fair, that wasn’t fair, that was never fair. Oh, shoot.” Tons of stories from my mission.

AA: When you say stories, personal experiences that hadn’t bothered you at the time, but in retrospect–?

CD: Yes. Just one example, when I was in the missionary training center before I got sent out on my mission, the guy who was the bishop over the little training center group that we were in… Uh, I still hate telling the story, but it is a true story. I went to Slovenia and so I was in a room all day. I was the only sister missionary. I was with two elders all day, every day learning Slovene and learning how to be a missionary. And this bishop I had in the MTC was very concerned that I was distracting the elders. And when I went on my mission, all I wanted to do was. serve God. I wanted so badly to convert the whole country and I wanted to be such a good missionary. So when he called me in to talk to me, I was thinking, he was going to compliment me and my efforts and be like, “you’re doing such a good job.” I was trying so hard to obey every rule and he called me in to be like, “Watch your body language. Don’t laugh at their jokes. Watch what you wear. Try not to make eye contact.”

“Oh, women are bothered by this. Huh. Okay.” But it didn’t bother me.

AA: Oh my gosh. By the way, what were you wearing?

CD: I mean, I was completely covered, basically wrist to ankle, almost, you had to wear pantyhose, you know? But he was so concerned that “a pretty girl like you must be terribly distracting.” Gross. My heart pounds every time I retell that story. At the time, I was like, “Ha, ha, ha… okay.” And so inappropriate, too. He asked if I had a boyfriend and he asked if he wanted him to get in contact with my boyfriend to try to make him reconsider marrying me. He was like, “Would you like me to call him into my office to reconsider?” Because he was a professor at BYU.

AA: Yeah. So bad.

CD: I know. Anyway, and then I had thought of a lot of unfair stuff that I just hadn’t realized, I hadn’t really thought about that much. Really it wasn’t until I think in 2020, I read Sue Monk Kid’s The Dance of the Dissident Daughter, and that was the point at which I was like, “Okay, I have a little baby feminine wound, maybe just a little bitty hole in my heart.” And I was like, “Oh, this isn’t just a hole, this is a cavern. This goes so deep.” And I had not even really conceptualized how much it had always been there, the feminine wounding, the divine feminine wounding, that lack of divinity. Father God is a god, Son God is a god, mother is just a mortal. There is no divine feminine, we knew nothing about her, we don’t pray to her, we’re forbidden from praying to her. And I hadn’t really thought of how that would affect me, but then I was reconceptualizing my life and thought, “What if I had spent my whole life praying to a woman?” Oh my gosh, immediately I was like, “Oh, ouch, ouch, ouch.” I could immediately see so much of the shame of this really strict Old Testament father god that had been kind of like the shoulder angel, the shoulder devil, he was both. He was at one point nurturing and loving, but always that other side of like, “You could be doing better. Are you repenting? Are you having the spirit?” Just all the time, so much shame. As a mother there would’ve been so much less fear and shame and guilt and so much more warmth and embracing, and I was so sad for my life spent in so much shame. And I know that’s not everyone’s experience, but that was my experience.

I lived with so much spiritual guilt and shame on a daily, almost hourly basis. So realizing that, and then that kind of broke me open to reading a slew of other books. And then I found the Breaking Down Patriarchy podcast right when you came out with it, and it made me feel so not crazy. I had no idea at that time, I was like, “Okay, I know the Mormon church is patriarchal and problematic,” but I really had no idea how deep it went in the rest of the world. I knew I wasn’t taught about women’s history in the church, like feminist history, which is what I talked about last time I was on your podcast. But I really didn’t think about the rest of the history. I was like, “Oh, I know about Rosa Parks, I know about Joan of Arc, I guess we’re good here.” And I literally can remember where I was every episode of the first six or seven episodes, and I just needed to sit down. I would be on a walk or I would be at home doing the dishes and I just needed to lie down. I was like, “Oh, it goes so much deeper than I even realized.” Of course in the Yellow Wallpaper episode and the Room of One’s Own, I was like, “How do women in the 17th and 18th and 19th centuries feel just like I feel trapped in this house, trapped in these roles?” It was so validating and such an important part of my awakening. I will be forever thankful to you because I was like, “Oh, it’s not in my head. I am not making this up.” Because you really don’t know. All I had in my head was 35 years of messages that if you are complaining about this, you’re the crazy one, you’re making it up, it’s equal, it’s fine. So, thank you.

AA: I’m grateful too, because as you know, I didn’t know this stuff either. That was the whole point that I did it. So we were on that journey together, learning from all of those books and all those scholars who, like you said, for hundreds of years people have been talking about it. It’s that reinventing the wheel, every generation of women struggling, thinking they’re crazy and alone when a lot of the work has already been done. Hooray that we found it, better late than ever, right?

CD: Hooray. And I don’t know if you remember this story, you probably don’t, but I wrote an essay called ‘The Never Ending Story of Mormon Feminism’ about how Mormon feminists keep having to reinvent the wheel because they have no idea of what happened the generation before them. I didn’t know about this massive Mormon feminist Sonia Johnson, or the ones before her or the ones before her. We just have to keep reinventing the wheel and waking up, and I had never heard that Gerda Lerner quote. And you, probably before you even knew who I was, commented on that essay, like way back in 2022 or something, and you wrote that quote and I was like, that is so funny that I reinvented the wheel of the quote of women reinventing the wheel without realizing Gerda Lerner had already invented that wheel. That’s like the exact essay, and this quote I’d never heard before.

AA: Yeah, that’s crazy. Okay, so you started your feminist awakening. What happened in your life when that happened?

CD: Well, yeah, that was tricky because I had really built my life brick by brick on the patriarchal promises and expectation that my entire purpose in life was just to be a wife and a mother. And I love being a wife and a mother, but I have had to drastically reorient myself into a person and not just a servant, really. And not just existing for other people’s health and happiness, but for my own, too. But I had already made all of my life’s choices based on thinking that was my entire purpose. So it was messy, it was a lot of grieving, a lot of like, “Okay, if I had a time machine, I would do a lot of things very differently. But I don’t have a time machine. I have this life, this one life, so now how can I take this one life and these circumstances that are my life, of having four children and being a stay-at-home mom, with some side hustles sprinkled in, how can I recenter myself in my own life?” And then you realize why so many women don’t, because it’s freaking hard and because at every turn you either think yourself that you are selfish or people are outright telling you that you are selfish or bitchy or mean, or whatever it is, that you are doing life wrong. Because really, we don’t like women who take up space, who make a stink.

And you realize that this is why so many women stay in their place, because it’s freaking hard. And again, it’s hard externally, but it’s hard internally. It’s so hard to undo. That selfish message goes so deep, so deep into your bones that every time you take another centimeter for yourself in your daily life, you’re like, “Am I being selfish? Did I go too far? Am I too selfish now? Is this too much?” When really, oh my gosh, when I think about when I had babies and toddlers, I had maybe five minutes to myself a day, crazy overcompensating to the way other end of the spectrum where I was almost a non-person, just a vessel of service. And it took a lot of work, Amy, I will not beat around the bush, internally and externally, and I’m not there yet, to try to center myself in my own life with four children and a husband. Can we talk about marriage for a minute?

AA: Yeah, please.

CD: I think a lot of women are in this situation, actually. I’m not the only late-blooming feminist out there who got married with one set of expectations and a script for how you think marriage is supposed to go, and then halfway through realizing, “Shoot, I’m an empty vessel, I did not center myself in my life, and now I need to make some changes.” Those changes are really hard. But I think the reason maybe this isn’t talked about that much is because women don’t ever want to talk badly about their husbands because they love their husbands. And it’s hard to both hold a deep and profound love for your husband and see him as the good man that he is, and talk about how our patriarchal scripts have failed us in creating equal marriages. And that is a really hard thing to talk about. It’s a hard thing to talk about publicly, it’s a hard thing to grapple with privately, but I think it’s really, really important that we don’t diverge into either extreme of either, like, “My husband doesn’t like to do the dishes and the laundry and childcare, so he’s a piece of garbage” or, “Well, this is our script and I love him, so I just have to do everything for him.” We have to find this middle road. And also if you want to leave then leave, I’m not here to divorce-shame anybody. A lot of times it is the best option. But for me, I didn’t want to divorce. I love my husband and I want to have him in my life. So I had to then figure out a way to both love him and rewrite our marital script completely.

AA: Before you dive into your particular story, I want to highlight, too, that you are the one who taught me this concept, which I think you got from bell hooks, which is more broadly what we both try to do in our work, which is to approach this topic with fierce love and fierce accountability. Both. bell hooks is a hero for both of us in that way, and like a guiding light in holding both. Can you talk about that a little bit and also the insight that you had politically about the fierce love and fierce accountability?

CD: Yes, thanks for bringing that up because I don’t think we recognize how rare it is to hold both. And bell hooks was an awakening for me because I was kind of used to feminist dialogue being all accountability. Like, “Men have not had enough accountability, they need way more, we have to hold them way more accountable” and just really harping on that. And understandably so, because there has been a lack of accountability. But bell hooks says that the great failing of feminism is a failure to include a love of men, which if we’re going to be effective in creating change, that’s a very important component. And also we don’t want to dehumanize anyone, that’s how war starts, that’s not good. It’s not good energy to have in your body, it’s not a good energy to have in the world, but it’s really, really hard on a micro scale and on a macro scale. It’s actually so hard and so rare to hold both love and accountability equally, because it’s easier almost if it’s just going all for one or all for the other.

And I’ll say in my life, I was taught the all love side, that the only important thing is having love for men, and so the only tools I was handed in my marriage were love, forgiveness, empathy, compassion, selflessness, accommodation. And those things are important in a marriage, but for women, they’re taught way too strongly, like way out-balanced in the tools of love. And if you don’t also have the tools of accountability, of setting boundaries, of prioritizing yourself and taking up space and holding your husband accountable if he is misbehaving or if he is hurting you or people around him. We don’t have those tools to hold them accountable for the consequences of their actions to make them see, “Oh, this action you’re doing is hurting me, it’s hurting our children, it’s hurting you.” We don’t have the tools because, if you were like me, we’re only taught the tools of love, and that seems to contradict love, so it seems like the wrong choice. It seems like the selfish choice. It seems like the mean choice to be like, “You’re harming us.” But it’s so important to have both.

AA: You mentioned that it aligns politically too, right?

CD: Yes. I mean, speaking broadly, obviously there are individual exceptions here, but I think the right tends to lean towards the only love script, and the left tends to lean towards the only accountability script. And you need both, you need love and accountability both on a macro scale and on a micro scale. And thank goodness for people like bell hooks, who are able to bring love into accountability. And I think another example of bringing accountability into love recently was Bishop Budde in her sermon after the inauguration. She gave a whole sermon on love and unity, which is what you kind of expect from a religious sermon, the all love script. And then her last three paragraphs were accountability to the president, being like, “Hey, you’re hurting people. You are hurting our trans and immigrant brothers and sisters” and it was holding him accountable. It was looking him in the eye and being like, we all need love and we all need unity, but you also need to know when you’re hurting people and have that brought to your awareness so that there are some consequences for your actions. And I think the reason that that went viral and made national news is because we’re not used to seeing it. We’re not used to seeing love with accountability or accountability with love or calls for both. It’s rare, and we’re very used to seeing all one or all the other. We’re very used to those messages. If she just had the first half of the sermon, “we all need to be unified,” on the right we’re very used to those kinds of messaging. “Let’s all be together in this, let’s all be unified.” And on the other side, if the end of her sermon was said from someone on the left, we’re very used to those calls like, “you’re doing harm, you’re doing harm, fix it, be better.” We’re very used to that. So that wouldn’t have made the news one way or the other if it was divided in that way. But when you combine both, and I’m not saying you have to be a centrist on every issue, I’m not saying that. Whatever your political standing, you can hold those ways you think the country needs to be run really fiercely while still incorporating elements of love and accountability together.

it’s hard to both hold a deep and profound love for your husband and see him as the good man that he is,

and talk about how our patriarchal scripts have failed us

AA: For sure. Other examples I’m thinking of are from the civil rights movement, like radically advocating for change while acknowledging the humanity in the individuals in front of you. Yeah, that’s so important.

So that’s kind of an overarching framework, and I really loved that. You’re the one who highlighted that or pointed it out to me from hooks, but let’s dig into now your particular relationship in your marriage, if you’re willing to talk about that.

CD: Yeah, for sure. And I’ll bridge it even further, from the macro to the micro. I remember on one of your YouTube scripts you invited Dr. Riane Eisler onto your show, who talks about dominator societies and partnership societies. And something that she said that I think about now all the time is that in neolithic societies, there used to be a partnership culture as a pattern that shifted into a dominator culture. And she said that shift started in the home. It started with the transition out of matrilineal and matrifocal societies into patriarchal, and then having the husband as the dominator and the wife as the dominated. So if we’re going to be transitioning now, we’re still in that dominator society that was set up centuries ago, where men are at the top of the hierarchy. And if we are going to make that shift again, it’s probably not going to be a top-down shift, it’s going to be bottom-up, it’s going to start in the home and it’s going to have to be love and accountability both. It’s going to have to be a shift into a partnership, not a domination. I think this work is actually so important if you want to be a mover and a shaker in moving towards a partnership society. It’s going to have to start in the home.

I love what adrienne maree brown says on this as well, she’s a social justice activist for racial equality and a lot of different things. She talks a lot about democracy and how the presidency is just the tip of the iceberg if we’re not actually willing to be democratic in our homes and in our neighborhoods. And if we’re not actually willing to have those compromising conversations where we’re working together in partnership, and we’re working things out and we’re compromising and we’re being democratic about decision making, instead of just one person always makes the decisions and one person always follows. Or in the neighborhood, working together to make a better neighborhood, those kinds of, again, bottom-up things, are how we create a better democracy. But we always just want to focus way far out, with top-down kinds of things. And those are important too, but we can have a real big effect in deconstructing the patriarchy starting in our homes and starting by refusing to be that kind of one up, one down partnership, which is so much understanding and empathy because even apart from religion and Mormonism, that has been our historical script, is for men– I mean, you have a whole podcast and YouTube channel, see those for examples, of how marriage and our society has been set up. So it’s very understandable that even if you go into marriage with the best of intentions, especially once you have kids, you kind of slot into these centuries-old grooves of these servitude/served roles. It’s very understandable.

So, back to me. I love my husband. I have a great husband. I have a feminist husband. He was marching in women’s marches when I was still annoyed with feminists. I was like, “You can go by yourself.” For years he would make signs, he would go and he would be marching with his boss and friends and I would be at home, like, “Have fun.” He is a great guy. But still, the script we were handed from his parents’ marriage, my parents’ marriage, my grandparents’ marriages, his grandparents’ marriages, all the way up, was extremely patriarchal. No matter how nice we both are, that was the script we were given, and we slotted into those roles. And to undo the status quo in a marriage takes a lot of work. Again, even if you’re working with very nice, compatible, wonderful people, it just takes a lot of work. We had to do therapy. I had to really, and again, a lot of it was internal for me. A lot of it was like, “Wait, no. I need to change, and then I need to validate myself that it is okay to change. It’s okay to ask him to do more.” And every single step I had to do that mental work of validating myself. And again, your podcast really helped. Like, “I’m not making this up. I’m not crazy. I’m going to ask him to cook half the meals.” That was a big one. Or do half the laundry. Do the kids’ doctor’s appointments. And yeah, it was just not an easy transition. We’re still working it out, but the progress we’ve made in five years is frankly, to give some help out there, pretty incredible. We really are trying for equality however we can. We did the Fair Play cards, we went to therapy, we’re going through it. And he has been really great, too. But yeah, at the same time, if I hadn’t done that work and insisted upon it, we would still be slotting into the patriarchal roles.

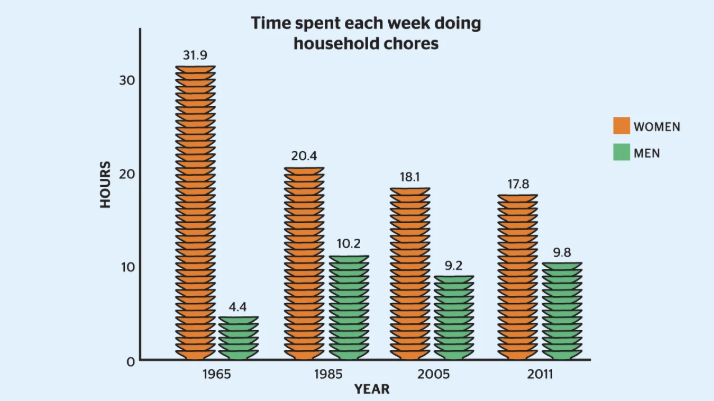

AA: And a lot of people stay there. We talked about this in our episode, pretty explicitly, on The Second Shift. Of the myth, the stories that women, especially, will tell ourselves to make it okay. But it’s not okay. If you logged everything, it’s definitely not equal. It’s demonstrably unequal. But in order to not get divorced, women will just say, “Oh, he’s so wonderful in all these ways. I’m not unhappy.” And they’ll just shove it.

CD: A million percent. Thanks for bringing that up. Yeah, women have really had gratitude weaponized against them, which is what Hochschild says in The Second Shift, that of her interviewees, she really in-depthly stayed with these 12 couples for years and interviewed them and watched their dynamics to see how everyone was feeling about the division of domestic labor. And she was like, “From my eyes, I am tallying, calculating the hours, and they are so unequal.” The woman does the first shift, these are all women who worked full-time, and does a full second shift at night while her husband is watching TV or in the garage or reading or sleeping. It wasn’t fair. And she said, however, every single one of the 12 of the women reported feeling thankful for how progressive her husband was, which I see constantly. And the other really interesting thing Hochschild says there is that they’re not wrong, because she did this study in Berkeley, in the Bay Area in California, which has always been a more progressive part of the country. And these men were more progressive. And so Hochschild says that they’re not wrong because on the scale of men, these men were more progressive even though the wives are doing all the work. Even at that time, and this was the early ‘80s, even just that they were allowing their women to work was thought of as something that the women should be thankful for. And all the 12 men said that. “She should be thankful I let her work.” But Hochschild says that they should be thankful given the range of men, if you’re going to compare men to other men, yeah, they should be thankful. If you’re going to compare the men to their fathers, which the men often would do, then you’re right again, you should be thankful. But if you compare the men to the women, if you compare the workload of the husbands to the workload of the wives, it is so vastly unequal. But the women were grateful because compared to the scale of men, they were the lucky ones. So just the difference of scales is really broad.

AA: Yeah. So you have this feminist awakening, you’re doing the work at home, which I love how you talked about that. I had forgotten that Riane Eisler said that, it was such a good reminder that it started becoming this way through just relationships, just regular people making changes in relationships, and that’s how we can change it again. Thanks for talking about marriage. At what point did you start writing about patriarchy in your Substack? And then I have questions about where do you get the material that you decide you want to talk about? And what have been some of the deep dives that you found yourself really compelled to take?

CD: Ooh, how much time you got? I clearly could talk about this all day. I often do, my poor friends. Yeah, I used to talk about my experience leaving the church on Substack, and then I just was done talking about that. I didn’t have anything more to say. So I transitioned. It was really an article I wrote about the movie Oppenheimer, which I hate. Anyway, speaking of a feminist awakening, one of the statistics that honestly kind of radicalized me like, “Whoa, this is a problem that’s so deep that I have never even considered,” is the Bechdel test. It has its problems, it has its issues. But learning that in the study of the 2,000 most popular movies of the past 40 years, less than half passed the Bechdel test, where two named women talk to each other about something other than a man, that’s the Bechdel test, less than half passed that. But 95% of movies passed the reverse Bechdel test, where two named men talk to each other about something other than a woman. I really had to be like, “Whoa, how have I never even noticed?” Never even noticed. I mean, pick a movie, any of our most popular movies, Star Wars, Harry Potter, Indiana Jones, James Bond, obviously, it is insane how rare it is for women to talk to each other in movies. So I wrote about that and that was responded well to, I was like, “Oh, people want to hear about patriarchy? Excellent, because I have so much to say.”

if you compare the workload of the husbands to the workload of the wives, it is so vastly unequal.

So I was going to talk all about women’s rights and inequality and different things, but I got like a month into this patriarchy Substack situation where I was like, oh, oh, oh. I can’t be talking about women. If we’re going to really get to the heart of this issue, I have to talk about the men. And again, not that we hate men, not that everything is men’s fault, but just that when we talk about feminism, when we talk about gender equality, we’re talking to women. When we have gender equality legislation, it’s for women. Men don’t talk about gender equality and we don’t ever speak about gender equality to men. We speak about it to women being like, “You’re not crazy,” da da, da. But I’m like, if we’re going to solve this, we’ve got to rope the men in and we’ve got to talk to them and talk about it. And this was my biggest a-ha of this entire year, maybe of my Substack in general, realizing the role of patriarchal masculinity, which is in front of me all the time, but I had never really placed it in its role in society. But the book For the Love of Men by Liz Plank was a big eye-opener to me, especially when she links– and let me just pause really quickly and differentiate patriarchal masculinity from regular masculinity from maleness. Maleness is being a man. It should be celebrated, it should be honored, it should be completely loved and honored. And then even masculinity, which is culturally dependent, has changed a ton through the centuries, throughout time. What that is, what that means to be a man in our current iteration, it’s often strength and assertiveness and confidence, and that’s wonderful, and that should be celebrated and that should be honored and encouraged. But patriarchal masculinity is defined as avoiding the feminine, basically like you can be these masculine traits that we’ve decided are for a man, strong and assertive and tough, you cannot be soft and effeminate and tender and caring and empathetic and all of those things. That’s patriarchal masculinity and that’s the problem, not masculinity, not maleness.

So Liz Plank says that patriarchal masculinity touches, I mean, pick a societal problem, any societal problem, like environmentalism. To be a man is to eat meat and drive a truck, and men have a higher carbon footprint than women. Let’s talk about war, like let’s talk about violence, let’s talk about corruption, let’s talk about anything. Patriarchal masculinity, being a man, is touching that societal problem, and yet it’s never brought up in the government, in legislation. How often do we talk about masculinity in any of these conversations we’re having about how to make the world better? Almost never, almost never. And yet it touches so many issues. And it’s actually bananas, bonkers, crazy that we never, ever talk about it. I’m pointing it out for good reason, because people don’t like it when you talk about it. Especially, sorry, men, but men hate it when you talk about masculinity as a woman. They hate it. My comments– whew! Anyways.

AA: Why do they hate it? Because I have observed this too. Why do they hate it? What do they say in your comments?

CD: I will cite one of my favorite patriarchy creators is Cyzor on Instagram and TikTok, and he is phenomenal. He says that people come at him all the time for talking about this. He says that the reason why is because in our society, patriarchy really places masculinity and being a man at the very center of a man’s identity. So when you come for it, you are not just coming for something that doesn’t affect him, you’re coming for the center of what he has built his identity and his life and his decisions around and how he sees himself. So it’s immediately met with defensiveness and dismissal and it’s very emotionally charged. And people get so, like you are personally attacking them even though you’re not, you’re talking about these societal scripts, but it feels immediately very personal.

AA: Yeah, that’s so true. I think I’ve seen that too. And it gives me compassion, right? For men. And I know how I have felt at different times when I have felt myself being called out for a certain thing or participating in a system of oppression over another group of people, and it can feel scary. It’s scary to confront the possibility that I’ve been an oppressor, that I’ve been doing things wrong, that I have hurt somebody else. I can feel that. Which just brings us back to what we were talking about at the beginning, the love and accountability.

CD: As a society, as a family, as a neighborhood, as a business, whatever it is. We want this life to be better for you. We want the world to be better for men.

AA: For everybody, yeah. Well, that brings us to the end of the conversation, Celeste. This has been so illuminating, even talking about topics that I think about all the time were brought into relief in a new way chatting with you today. I’ve enjoyed it so much. Let’s wrap up with some final takeaways, some things that you want to leave listeners with as we end.

CD: Yeah. I’d say, again, the dismantling of patriarchy starts in the home. Just like any system, I think it does fall to people at the bottom of the hierarchy to really stand up with their heads held high and their shoulders held back in integrity, staying out of that drama triangle of being the perpetrator and the victim and the savior, staying away from all of those roles. But just in integrity, in love and accountability, saying, “I love you. I love men. I love everything, and things have to change.” And knowing that that doesn’t make you any less loving, but being able to really make your marriages more equal, that’s sacred ground. That’s not selfish ground, that’s not you whining and complaining. That is sacred ground and it’s important. It’s hard work, but it’s important work. Hope for the future, hope for making things more fair for everybody.

AA: Mm. That’s so beautiful, so powerful. Thank you, Celeste. Okay, really quickly, tell listeners where they can find your work.

CD: I am on Substack. My Substack is called Matriarchal Blessing.

AA: Okay, awesome. Yes, I highly recommend Celeste’s Substack. As I said, that’s where I first knew who you are, is through your writing. You’re a powerful force for good in the world, Celeste. Thanks for joining me today.

CD: As are you. Thank you.

even if you go into marriage with the best of intentions…

you kind of slot into these centuries-old grooves

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!