“Don’t let boys tell you you can’t do it.

You’re allowed to be here.”

Amy “levels up” her video game knowledge with Game Developer Ashley Ruhl, who teaches us about feminism in gaming, Gamergate, women wastelanders, ‘pink games’, and how all of us can help support gender equity and representation in this massively popular pastime.

Our Guest

Ashley Ruhl

Ashley Ruhl is a Narrative Director, Narrative Designer, Cinematic Designer, and Writer exclusively in games. Over the past 13 years she has focused on a multi-prong approach of character-driven narrative, eye-catching cinematics, and intuitive game design. She was the first woman at Telltale to hold the titles of Episodic Director and Assistant Episodic Director, credited for Episode 3 and Episode 1 of “Tales from the Borderlands” respectively, and was selected for Forbes “30 under 30” list in video games in 2016. Ruhl focuses on cinematic delivery and strong emotional agency in game narrative, creating memorable moments that encourage players to be authors of their own stories.

The Discussion

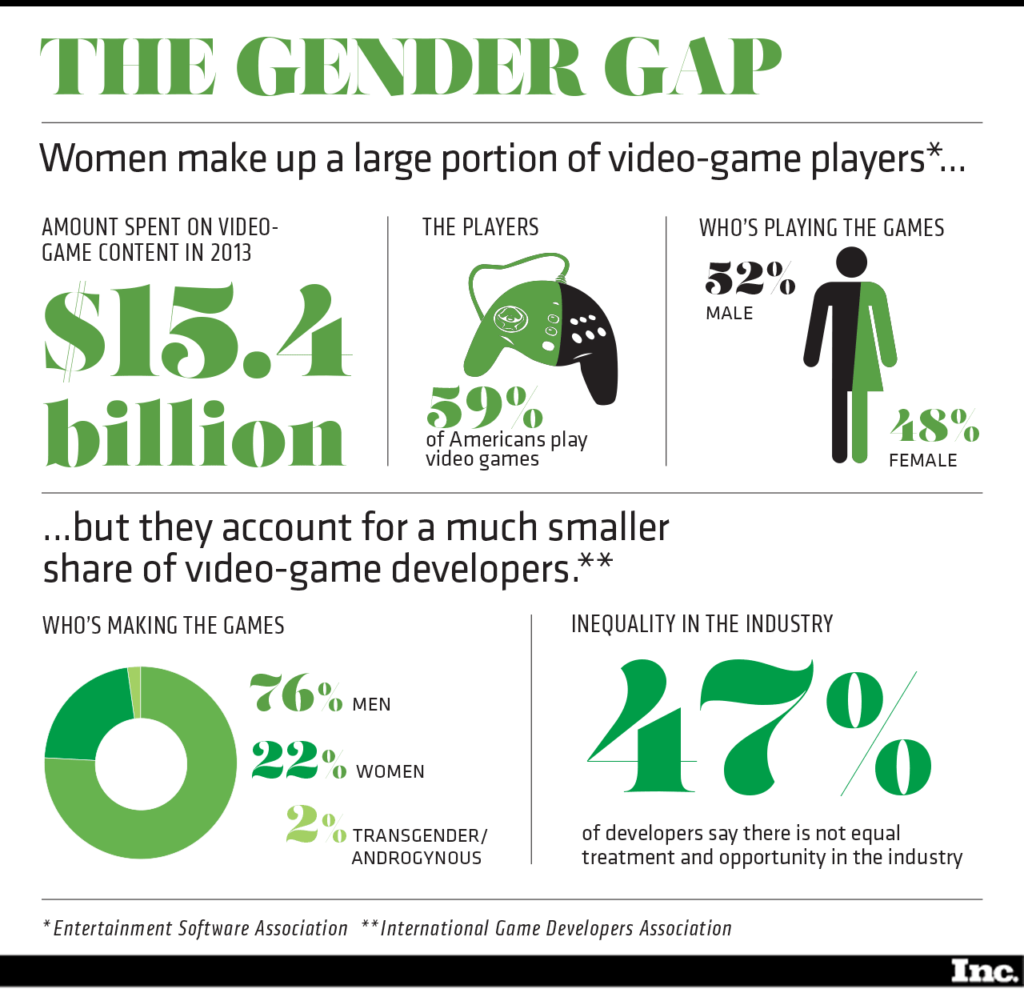

Amy Allebest: I’d like to start today’s episode by asking you to imagine a person who plays video games. If the person you’re imagining in your mind is anything like the popular representation of gamers, they’re probably young–a teenager–maybe pale, geeky, maybe hiding in a basement, and of course you probably imagined them male. And yet this lingering stereotype is quickly becoming outdated as gaming today is far from niche or nerdy, with over 3 billion gamers worldwide and a rapidly closing gender gap. As of just last year, 46% of video game players worldwide were women, and that percentage is only increasing. In fact, if we look at mobile and tablet gaming, the majority of players are already women. And yet, despite these shifting demographics, video games continue to be largely made by men for men.

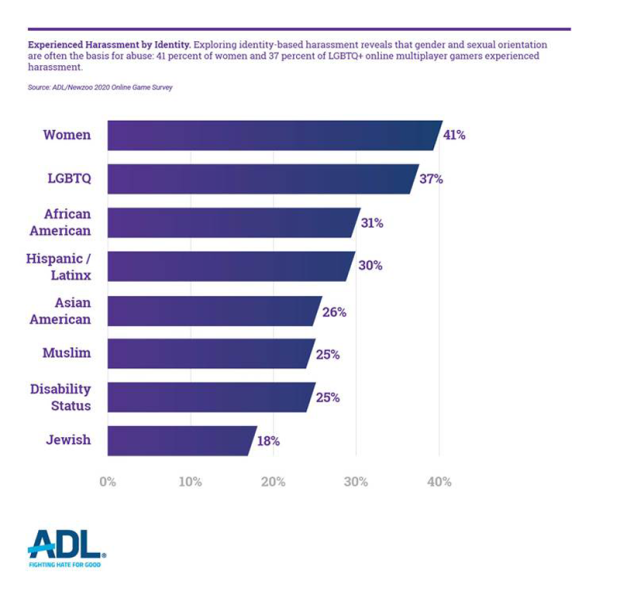

According to Women in Games–a nonprofit dedicated to women in gaming and esports–among the top 15 games companies, their executive teams are on average 84% male. Again, in this industry where nearly 50% of players are women, women occupy only 16% of executive roles. If this weren’t enough, research also indicates that female characters are overly sexualized and often shunted into secondary roles within the games themselves. And these sexist tendencies unfortunately reflect in the gaming communities as well. With the 2023 study finding that nearly 75% of women report harassment when playing games online, and tragically 59% say that they hide their gender altogether while playing games for fear of how they’ll be treated.

As this industry and pastime continues to grow and grow, affecting more than a billion girls and women across the globe, it’s clear that this form of play can have serious influence on our culture, and that is why I’m so excited to be discussing video games today with narrative director and gaming professional Ashley Ruhl. Welcome, Ashley.

Ashley Ruhl: Thank you for having me.

AA: Ashley Ruhl is a narrative director, narrative designer, cinematic designer, and writer exclusively in games. Over the past 13 years, she has focused on a multi-prong approach of character driven narratives, eye catching, cinematics, and intuitive game design. She was the first woman at Telltale to hold the titles of Episodic Director and Assistant Episodic Director. Created for Episode Three and Episode One of Tales from the Borderlands respectively, and was selected for Forbes 30 under 30 list in video games in 2016. Ruhl focuses on cinematic delivery and strong emotional agency in game narrative, creating memorable moments that encourage players to be authors of their own stories.

I have to say, I mentioned this to you before we started Ashley, but my 16-year-old son is very, very into computer games and not just as a consumer, not just as a player, but as a creator. He’s building a game right now that’s already taken more than a year, and he will be so excited to listen to this episode. He’s crafting everything from character to, like, he does the art, he does the music, he loves world building is basically what it is. And I’ve learned so much about gaming through him that it really is this immersive, rich world. So I’m really excited to hear about that and about women’s experience in games.

Before we dive into that content though, I’d love it if you could just introduce yourself to listeners, tell us where you’re from and kind of what brought you into the gaming world and doing the work that you do today.

AR: Sure. So if I went back, if I go back to when I was a kid, I didn’t have a lot of game consoles growing up. It was not something that was common in my household and it wasn’t a gendered thing for me, but it was mainly my parents wanted to avoid giving me game consoles ’cause they thought I’d be in front of it all day. I don’t think that would’ve been the case; and it was weird too ’cause they let me play like PC games or Mac games, you know, shareware stuff and the Monty Python’s Complete Waste of Time. Just weird stuff like that. But I didn’t grow up with games and it wasn’t until I was 12 that I got my first game console. And so I was playing a couple games on there, like Glover is one of my favorites, Alone in the Dark: The New Nightmare. And then as I got older, I started seeing the games that I wanted to play were not as common. I think the tone and the kinds of things that I was interested in were not the mainstream and not the games that everybody else was playing.

When I went to college, I majored in animation and I always knew I was going to be some kind of visual artist and I wanted to go into commercial art. And originally I was thinking feature films, marketing, that kind of thing for animation. But then I found the game program at my college and I was really intrigued by game narrative and the idea that you could build this world that immerses people, that brings them in and it becomes their story as well. And I can talk more about this later, but I really love the way that game narrative kind of forces self-reflection because it means that you are putting part of yourself into the role of this character. And so you start to think, well, what would I do? Or what would this character do? And it’s kind of a gateway towards self-reflection and thinking about yourself as part of the game.

Even then in college, it was still very difficult for me to feel like I was quote unquote, a “gamer”. There was definitely a gender gap there, and I struggled a bit to feel like I belonged in that space, but it was just something that…you know, when it grabs onto you and you just feel like you wanna push through it because it’s important to you! You just kind of stick with it.

And when I graduated school with an animation degree, I was originally again looking for animation jobs, but then I fell into the world of cinematic design. And the game that I’m actually currently working on was originally launched in 2011, so it’s been around a very long time. That was when I was getting into the industry, and so I was an animator. I knew a little bit about camera work, like character performance was my forte. And they said, “Hey, we’re looking for contract cinematic designers for this game. We want you to make the cut scenes inside this game”. And I was like, Sure, yeah, I think this works. But then I ended up accidentally making a whole career out of it and really working on cutscenes–like visual presentation of characters–and really based in games that had choice, that had dialogue choices and different ways the story could play out. And that’s how I started getting more into the narrative side of it and then the writing side of it, but really just understanding the way that players engage with the narrative within games.

So my career has kind of been all the facets of narrative within games, whether that’s the scripting side of it, the gameplay part of it, the writing or the cinematics. And yeah. Then I just came back to this team for Star Wars: The Old Republic a couple times, and now I’m the Narrative Director, which is super cool. So I feel like I’ve grown up with this project a little bit, even though I wasn’t here the whole time. I left and came back and saw different iterations of it. And so that’s where I’m at now.

AA: So cool. Tell us a little bit about what you actually do as a Narrative Director.

AR: So as a Narrative Director, I oversee basically anything that is narrative within the game, and that involves reviewing the writing, reviewing the cinematics. Our team is full of implementers too; all of our directors are also implementers, so I’m also still building cinematics.

Before this, I was the Lead Cinematic Designer on the project, and then when I moved into the Narrative Director role, that fell to someone else. I still make cutscenes in the game, but as narrative director, I’m kind of overseeing all of that–giving those reviews–but I’m also helping shape the overall direction of where we want the story to go, how we want all the pieces to feel, what the tone is of everything. And on top of that, I’m also coordinating a lot with the other departments. So we have multiple departments of design. We have gameplay, we have level design, we have the UI interface, all of that. And then we also have our art teams. So my role as Narrative Director is to coordinate with all those different departments and make sure whatever we’re building in narrative really syncs up with everything that’s happening in the game and that we’re all moving towards one big cohesive vision. So I kind of have more of a bird’s eye view of things while also seeing all the details on the ground and just making sure we’re all coordinated.

AA: Hmm, that’s so cool. I have so many questions about this and I’m realizing…like I’m new to the gaming world, completely new and only kind of acquainted with it through my son, but it really strikes me, especially when you were talking before about the player having agency–that world building in a computer game context. This is not gonna be new to you, but maybe listeners who aren’t acquainted. I mean, it’s really striking me anew that it combines all of these areas of the arts that I love as a liberal arts person. It’s combining literature when we’re talking about narrative and a story, right? A story’s happening where a character is so important and we can relate to that through books that we’ve loved from the time we’re young. But then you’ve got this art element too. People are creating worlds; some of them are painting and they’re using graphic design and creating this world. And then you have music. And sometimes the soundtracks are so evocative even on their own that you listen to them separately. And then you’ve got even like the costumes that the characters are wearing. You are creating a world, but the difference is you combine all these artistic elements.

It’s almost like a play that you can act in, but you’re not scripted. You get to decide what you do in that world. So it is this incredibly rich art form. And as we get in to discuss the gender implications–we’re gonna see reflected in these new imagined worlds what human beings do in the real world, and what they bring to it. So as the Narrative Director, I’m wondering, as you oversee all of that stuff, does gender play into how you direct things? I’m really curious how it would be to have a man as the overseer of this world creation versus having a woman bring different sensibilities to that.

AR: I think it definitely comes down to personality, and I think that we can see from historical and the way other games have been developed that it can lean in one direction or another, depending on gender more stereotypically. But for me, I think it’s: if you can lead with empathy and inclusion where you’re trying to make sure that all the voices are heard, and everyone is contributing to a bigger picture, that’s where I think the strongest product comes from. I think that does lean more into a matriarchal view of things versus a patriarchal. My perspective on a matriarchal society is not just that women are in charge, but that we lift up the weakest among us or the people who need the most, so that we are all on even footing. We are a circle. And you need someone to guide that vision, but they’re not necessarily the person who makes all the decisions and everybody just says, “Okay, I’m doing what that person wants.”

it’s kind of a gateway towards self-reflection and thinking about yourself as part of the game.

There are definitely some games that have had more savants or creative leads that say, this is my vision. Everyone execute on my vision, and we celebrate those people and we lift them up. But it’s not always the whole picture. You know, for me, my approach is much more about trying to get the most out of my teams by inviting them to the table and saying, “here is the rubric, here is the outline, the space to play, and I wanna see what you bring to it.”

I’m also a band kid, so the idea of the whole band is a greater sound than any individual instrument is something that really affected me when I was younger. And I try to bring that into the creative work that I do as well. So in that way, I think–if you’re thinking about it in gender terms, if women are more prone to lean on the strengths of their teams and invite everybody in to be a part of this bigger image, versus men who are more inclined I’ll say to be the strong leader who tells and dictates to people what to do…that is one way to look at it. But again, I think it’s very dependent on personality and it’s not necessarily bound by gender. I’ve seen it completely the opposite. But more stereotypically I could see it falling in that direction.

AA: Yeah. Well that’s really cool ’cause that’s applicable, I think, to all different fields of work too. Just that style in the workplace of lifting other people up, like you said. It makes me think of Riane Eisner’s ‘dominator culture versus partnership culture’ and bringing partnership wherever we happen to work. That’s a more equitable and egalitarian way to conduct anything that we do in the world. So that’s awesome.

AR: Yeah. I also have been a, a conference associate at the Game Developers Conference for a very long time and basically help run the conference. And that program is run as very much a service-oriented leadership style where it’s less prove to me why you deserve to be here. And it’s more how can I help you do your best work? And I try to bring that mentality into my leadership as well, because I want people to know on my teams that I know that they are capable of the work and I want to know how I can empower them to find that. And I think very often in the game industry and in many industries we can have leaders that say, “well, you’re just not cutting it,” or “you’re not proving to me why you belong here.”

And this also ties into being part of gamer culture as well; the gatekeeping and the like prove to me why you belong in our circle. For me, that is so deeply imprinted in my brain that I’m just trying to make sure that everybody knows that they are welcome and that I want to make sure I can do what I can to make them feel comfortable and empowered in those spaces.

AA: That’s awesome, Ashley.

Okay. Let’s talk about gender equity in gaming. I’m curious if you have any personal experiences of what it’s been like to be a woman in this historically male-dominated field, and then if you can talk about any trends you’re noticing or data you’d like to share with us.

AR: Yeah, so like I mentioned, when I was in college it was definitely already an imbalance. I think it was harder to be a woman in the gaming spaces because of a couple of factors. It was this choice I had to make of things that I’m like, well, do I wanna take the energy to call this out because it’s annoying me or because I don’t think it’s fair? Or do I want to stay silent and let it slowly eat me away on the inside? And both of them have negative things to result in. For me personally I remember… so I went to college between 2006 and 2010, and I feel like games in general have gotten better with gender representation, but I also know that the treatment of women in gaming spaces has not changed that much as much as I’d like it to, which really bums me out. It’s over 10 years ago. but I remember there would be times where I’d call out like, why do all the female characters have to have midriffs? Why do all of them have to be, you know, super sexualized? I remember my guy friends being like, “Ugh, this again.” I’m like, but no, it’s important. Like, do you see this? Do you see this imbalance? And because they didn’t share my world perspective or my life perspective, it was harder for them to accept that things should change. The norm was wrong.

I have seen that shift and I have seen, as the industry has matured, we have more of a range of representation for femme characters and masculine characters, which is super cool. There are still some things that hold very true, like Call of Duty is gonna be very Call of Duty, but we’ve also seen a lot more female soldiers in those games that don’t have to be sexualized or have a completely different cut on their fatigues, you know?

I’ve also reflected, and this is part of my personal growth through all this, is that I’m what I call a ‘recovering cool girl’, where I was the girl who could hang with the guys. And so I was repressing a lot of who I was, my gender identity because I wanted to fit in. And so I hated the color pink and I was so upset by anything that was even suggesting that women could be sensual even. And now I feel like I flipped almost the opposite direction. I’m like, anybody can be anything. And so I’m excited to see the super macho masculine woman, but also the woman who likes to flaunt it and likes to be more sexual and be more expressive with her gender. But I like to see that with the male characters as well, and everybody in between, the whole rainbow in between. I like to see that representation for everybody and I think we are seeing more of that in games.

But if we look at just the biggest games that are the most exposed to all of our media culture, it still leans very heavily in stereotypical gender norms. But there’s a lot of really cool colorful stuff that’s happening in indie spaces and more game development focused spaces.

AA: Hmm, that’s really interesting. Yeah, I was a total ‘pick-me girl’ too for a while. I think it’s really common to go through that phase in life. Partly I think just ’cause psychologically you’ve sensed from the time you’re little, like…those are the people who have power in the room. Those are the people who can keep me safe physically or in my career. Ingratiating yourself with that power totally makes sense. To keep ourselves safe, right? To be like, oh yeah, I can hang with it. I’m not gonna cause any problems. At least that’s kinda the process that I’ve gone through to have compassion for myself when I look back on how I did that.

And it’s super scary and uncomfortable and it’s just nobody likes to be the squeaky wheel. Nobody likes to be in that role, right?

AR: Yeah, yeah. A hundred percent.

AA: …a gadfly that’s just annoying people all the time. Like, sorry, but there’s still a problem. So it’s understandable.

I’m curious how these changes– ’cause it sounds like there’s still room to grow, there’s still distance yet to be traveled– but how have the positive changes happened so far in the past? Has it been through women speaking up in the industry? Have there been any noticeable shifts in policy? Hhow have those changes happened?

AR: Yeah, so there has been a lot. I’m not a huge expert in these fields, but I can talk kind of broadly of how the industry has evolved. Are you aware of the Gamergate movement?

AA: Oh yeah. I’ve heard of it, but actually I wouldn’t be able to describe it, so I’d love you to talk about it.

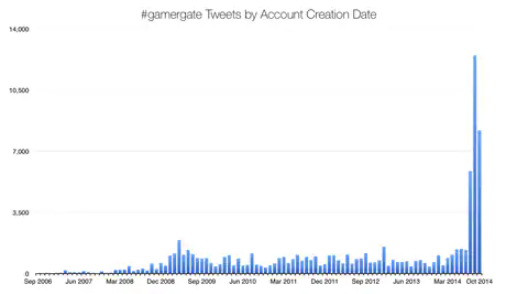

AR: Sure. So Gamergate started in 2014 and it was one of the first doxing campaigns. It was the internet-majority men targeting marginalized women–women of color and transwomen–and ciswomen, basically saying you don’t belong here. And making a very concerted effort to push people out of the industry and push them off the internet.

It was a really scary time. And at the time I was still a minority within development spaces, in the studios I worked in. So I got very used to being the only woman in the room. It was not something that was uncommon for me, like when I was in high school I was a drummer, I was one of the few women on my wrestling team in middle school. I just got used to it. I was like, this is normal. I don’t recognize that I am the only woman in the room. Other people will see me a certain way, but I don’t see that. I don’t see that I am a gender minority here.

And so when Gamergate came around, I was definitely freaked out, but personally, I did not feel as threatened. I knew a lot of people that I cared about were, and that was scary because at the time I did not know many women in game development. We were isolated. We didn’t really have a lot of connective tissue, or at least for me coming into the industry when I did. And I feel like Gamergate highlighted that there are a lot of women in the industry. Even for the people who say, “oh, there were just a couple of them.” It’s like, no, there are a lot of women. And there was a bit of women coming together after Gamergate to really say, “No, we are here. We do belong here.” And that kind of formed a lot of communities that I still have, of women in the industry that…we can all rally together and go, no, that is weird. That is a weird thing. We shouldn’t be dealing with that.

So there was definitely a shift there for sure, where women realized we had to be a bit more vocal and also stand up for each other and make ourselves more visible. And then in the years after that, there were more people, especially in the wake of the MeToo movement in Hollywood that, within games, women were speaking out more against the sexist policies or just the cultural things that were definitely not okay within studios. We saw that happen a lot at Riot, for example. Riot Games had huge lawsuits about the way women were treated, the way the C-Suite treated women employees and that kind of thing. And it became more normal to speak out about those things. And it doesn’t mean that those people came out without scars because they were the ones who spoke up, but we started seeing more of that and being like, no, actually, that’s not okay. That’s not okay.

And slowly cultural change happened. Slowly over time, the bro culture of studios started to fade away. Now we look back on it and you go, oh, in like 2010 there were executives having pool parties with women they had hired in bikinis. Or ‘booth babes’. ‘Booth babes’ were very common. They’re just women that they dress in scantily clad outfits and they put them in front of booths to drive people to those booths at conventions and expos and things like that. And we’re seeing a lot of that go away just because we’ve shone more of a light on it and we have more people saying, no, that’s not okay. And we have a lot of men too, being like, actually I never felt comfortable with that, but I never felt comfortable saying anything about it.

So I think we owe it a lot to the women who started speaking up and started organizing and finding a lot of other people to group together and say these things to make the industry better. I still think there’s definitely some gender bias in some things. Like you mentioned at the top, the executive level is still predominantly men. We have a lot more women in junior roles and mid level roles, but when you get to manager, director, C-Suite, there’s fewer women there. So there’s definitely still an imbalance, but I think it’s still shifting. It’s still changing. So even if it feels slow, I do see the progress over the last decade.

AA: That’s really great. I feel like I was gonna ask you too–and you already kind of answered this–but it seems like Gamergate was happening around the same time as the MeToo movement and I was just reflecting, even just this morning actually, on things that used to be completely normal, like stuff that boys would say to me just in the hall when I was in high school, for example. I’ve told my kids things that I used to hear in the hall and they’re like, what? That is such egregious sexual harassment. Who did you tell? I was like, “I’d never heard the term sexual harassment. I didn’t tell anybody. It was just normal and I hated it, but there was no vocabulary to describe what was happening, let alone have somebody say ‘that’s what that is. Here’s what you do and it happens. You can go to these people, you can get help.’” And I feel like once that’s established and once you kind of have critical mass of enough people with that sensibility, that’s when things can start to change faster.

So do you think within the industry now, if crap happens, that you’ve seen a shift where women would be like Absolutely not. Like we’re not gonna do that anymore and people know what to do about it? Has it reached that tipping point or are we still kind of struggling to get there a bit?

AR: I think we definitely have more resources and I think when we’re looking for it, we can find the references for what to do in those situations. Because I think in your gut, you’ll always know when something doesn’t feel right. But the question is, do you tamp that down to stay the course or do you look for resources or be vocal about it, about what’s going on?

I think there’s definitely a shift in how our communities are connected and there’s always going to be a certain amount of protection that studios are doing to protect themselves from things that are happening that are inappropriate. But we have more external resources now, I think, that are saying “Hey, you don’t have to put up with this and we want to be there for you to let you know you’re not nuts.” You’re not nuts for revealing this is wrong. And I think for me, that’s the biggest comfort. It’s actually why I wanted to foster a women-in-games space in Austin where I live, because I am already meeting women that are just starting in the industry and have 1, 2, 4 years experience who are saying “Oh, this is happening. This makes me feel weird. I don’t know if he should be saying stuff like that, or I don’t know if this is how this should go down.” And I go, oh no, that’s definitely bad. You shouldn’t have to deal with that. And it’s okay for you to speak up and push back against that. And just that little bit of encouragement to say, yeah, oh, the feelings I was feeling are valid and I should push back against this.

Just having that little bit of community support I think goes a long way because it makes us all into advocates that feel like we have someone in our corner. Even if we don’t have someone on top dictating, yes, this is this and that is that we have more community support on the ground.

AA: Yeah. Amazing. And as you said, the more people and–you are in a leadership position now as a director, right?–and the more women are in the C-suite, that really helps. Because then you can go to a superior…well, it would be assumed, sometimes women are upholders of patriarchal systems as well. It’s not a guarantee, but more likely as there’s more gender representation that you’ll be able to go to someone who could actually do something about it too, as well as having that support like you said, with coworkers. That’s awesome.

Okay. I have a specific question and I’m thinking about the game Half-Life and then my son loved Half-Life: Alyx. And he talked about Half-Life: Alyx, for a long time before I realized that Alyx was a woman, ’cause it’s kind of a gender neutral name. That was kind of like a shift for me. Like, oh wow, that’s actually so cool. And I’m wondering about the kind of behind the scenes of what goes into writing a character, or what considerations go into writing a female protagonist as opposed to a male protagonist. What are programmers and the people who are writing those characters…what are they thinking about?

You’re not nuts for revealing this is wrong.

AR: I think the biggest thing to start with is life experience. If you can find writers who match the life experience that you’re trying to put on screen, that is the ideal. Not to say that they are the representation of their gender or their orientation or their race or anything like that, but it definitely gives you a better starting point to create a more authentic character.

I think where we got started was we just needed to make the genders feel less gendered. And more about personalities and more about how people approach the world. We started with a male is default, like that was just the normal. And then women are a very specific, like that’s a personality trait is women. And we needed to bring it to the middle where your default is person and that can be played by a man or a woman, and we normalize that.

That was actually one of the reasons I felt like I could continue with playing games and potentially making games was when I was in college I played Mass Effect. In Mass Effect, you play as Commander Shepherd and you can start out in the character screen as male or female. And all the lines are the same. Just one has a female actor and one has a male actor. There are a couple lines here or there that are more gender targeted–like from other characters commenting on you–but as the hero, you are Commander Shepherd, your gender is not important in that equation. And that moment when I got to be Commander Shepherd and my gender wasn’t being addressed by all the characters, I was just a really cool character in this sci-fi opera. That was the moment that unlocked it for me. It was like, you gotta normalize it. You gotta normalize gender.

So I felt like that was where we need to just start now. I feel like we’re at a place where we can get into the subtler tones of how people communicate and how societal gender, like upbringing changes the way we interact and speak. There’s an argument for saying that it’s nice to imagine a world beyond that and beyond our gendered upbringing that makes writing a female character different than writing a male character. So that’s something we can strive for in narratives. But I also think it’s nice to have characters that connect with our life experiences, so we try to connect that in the way we write characters to subtle things. You know, the way people react to a probing question or how someone takes on bad news or how they direct a room and using that gendered upbringing. And part of that is part of their personality, how they developed that personality, but it’s not the only part of it. There’s a lot of other factors in things that influenced how that character should act and move and speak and interact with everything around them.

So that’s kind of the world that I’m excited to be in, is that we get to use that as a lever, but it’s not a defining trait. I joke about how you look at the action films of like the aughts and you have the muscle, the fixer, the programmer, the woman. Like she’s just her role on the team and she doesn’t get to be anything but the coolest person you’ve ever seen. And she has to be twice as good as everybody else. And I’m like, no, just gimme the weirdos. I want mediocre women. I want women in my stories that are just normal people trying their best and failing sometimes. That’s what I want. So like there was an example I had when we were making Tales From the Borderlands in Episode Three… Borderlands historically, most of their enemy types are men, and these are people of the wasteland. It’s very Mad Max. And so the idea was, oh, I don’t feel as bad shooting a guy in the face as I would shooting a woman in the face, which is its own bag of worms that, you know, we can get into. But I didn’t want that for our game. And so we were making a game within that universe. And I was like, no, I want female goons. I want as many female goons as guy goons because I want it to be clear that this is everybody. This isn’t a one gender sort of thing. And so the thing I pushed for was just having in the background, some of the bad guys that you’re defeating are also women. They don’t need to draw attention to it. They don’t need to say, oh look, there’s a woman like… that’s irrelevant. That’s a bad guy. You shoot the bad guy. And I wanted to kind of just normalize it. And so that’s kind of been my strategy with a lot of character development and bringing different genders and different backgrounds into narrative is just normalize it, normalize that they are there and everybody knows that they’re there, and that’s just a thing, that’s just a normal thing for everybody. And we can have just as many character traits as the male characters. Because again, they’re just people, instead of woman being only this one thing…

AA: Yeah, that is an interesting can of worms though. I hadn’t thought of that–like the social norms that would protect women. Like, a man in the real world…like because of the size differential, right? Like a man hitting a woman is something that, you know, you never wanna see that gender-based violence. So that is a really complicated issue. And that’s interesting. In a virtual world, what are those dynamics like? Can you speak to that a little bit more? And then I think kind of part of this too, the way the gender dynamics play out, I would love to have you describe how sexual harassment, or even like virtual assault does happen in the virtual world. Can you describe kind of some of those dynamics of like how people treat each other in their gendered kind of avatar roles?

AR: Yeah, I have some examples of that. It’s tough because it’s like we have the examples of the worst. Most of the time things are pretty even keel, and I think in general things feel more balanced. But there are definitely some people who cling to stereotypes and clinging to those gender dynamics very fiercely, and they make the most noise. But in terms of the dynamics of gendered characters in game development, I actually…when I was working on Defiance–which is an online game, you see a bunch of other players in the world–I actually got into pretty fierce debates with our animators about, they’re like, oh, we need different run cycles for the women. And I’m like, “why?” And they’re like, well, women move differently. And I was like, “what do you mean?” And they say, oh, well, you know, they move more with their hips, there’s more feminine… And I’m like, “okay, hold on. First of all, no. Second, I understand there are more stereotypical ways that you’re going to portray gender. You can be the big masc guy or the small femme woman, but there’s such a broad range the body types and gender representation.” And I was like, okay, first of all, I think that we should be addressing all of our characters as ‘warriors of the wastes’. That’s what they are. They’re all soldiers of fortune, so they’re not gonna run differently because of that.

If we had more of like a different character type or a different job that meant that they would maybe move a little bit more centrally or sultry, sure. But then that would also go on the male characters if they’re in that role and that vocation. But if we’re thinking about them as like, no, they’re all rough and tumble, camping out, shooting bad guys, that shouldn’t come into play, in my opinion.

There are, of course also some examples of when you do gender the body types, and then you put an animation on both of them one looks a little different than the other. Underneath a digital character is what they call a rig, and the rig is the skeleton. Then all of the geometry on top of that is their body mesh. So the body mesh sits on top of the skeleton, on top of the rig, and then you animate the bones of the rig to make them move around. If you have designed a male rig to be a much different proportion than a female rig, if you apply the same animation of both of them, the male character may look normal when they’re walking but if it was designed for his skeleton and you put it on a smaller skeleton, the arms may be out here like just hanging wide off their sides, and the legs might be a little bit more splayed as they walk, and that can look strange. But again, that is a detail in the design of the rigs that you’re like, okay, you really gendered the rigs. So then if you want to go animation for everybody, you’ve kind of screwed yourself ’cause you’ve made it so you have to make two different animations because you’ve changed the skeletons so differently.

But tying into that, I think because of the way we have created a very different design in male versus female characters, it definitely allows people with less than the best intentions to express not healthy behavior towards particularly female presenting characters in games. I had an example when I played EverQuest Two online on the PS2. It was the weirdest thing ’cause I had a, the PlayStation 2 was not designed to go online, but I had the little attachment on the back for an ethernet cable. I had a keyboard that was attached to it. It was wild. But I remember I played this female barbarian and I loved her ’cause she was like seven feet tall, just big and muscular. And it was like goals. And I had this other male barbarian who kept following me around. Just because I had a female character and like getting really close to me and like wanted to like pretend we were kissing all the time. And I’m like, dude, go away. I wanna play the video game. And then there’s always the chat stuff that happens in chat comments that can occur. And I’ve also seen like people who just give lots of in-game currency to female-presenting characters ’cause that makes them feel good.

AA: Like money. You’re saying they use like digital money in gifts and stuff because they want this female character to like them?

AR: Yeah. And I’ve seen men who play the female characters because they get more attention and just more people pay attention to you if they think you’re a woman. Because I mean, that’s normal in nerd spaces as well, where you just get more attention whether you wanted it or not. And that can be very frustrating ’cause you’re like, I just want to be quote unquote “normal”. I just wanna play the game like everybody else.

So that’s like the presentation of the character, even if you aren’t a woman in real life, can affect how you play the game. And some people lean into that and they lean into the perks of it. But I’ve also seen a lot of men who play a female character in games and see the way that they’re treated and see how it’s different and go, man, I had no idea. And you just kind of tilt your head like, really? You didn’t, you didn’t know, huh? But, you know, it’s just perspectives, it’s life perspectives and what we have sort of come to internalize as “normal”, quote unquote, or as acceptable. When other people step into that, they go, “this is awful. How could anybody put up with this?” It’s like, well, we’ve internalized it. We’ve decided that this is okay, or at least that we have to deal with it. Like it’s expected of us to just deal with this.

AA: Yeah. That’s fascinating. I was thinking about how one primary feature of patriarchy is the centrality of men. Just the man is the default person. And like you’ve described already in this conversation, the man historically has been the default character, and then there’s oh, another that’s a woman and she’s the sidekick and she has these tropes that she falls into, but the person default is man. And as a girl growing up, like, there were books that were for kids and then there were ‘girl books’ and there are movies, and then there are ‘chick flicks’. The default thing is the masculine, the default thing is the male. And so like all of us know what it would feel like because we grew up, you know, reading Harry Potter for example, where the main character is a boy and the main bad guy is a boy, and the main wizard is a man. You know what I mean? We are used to that. We are used to playing male characters in our minds and… until very recently, a boy would never have gone to a chick flick or read a girl book, right? Because of misogyny. Like a boy doesn’t wanna be associated with a girl character.

And I was just gonna ask you, and then you answered it like, oh my gosh, it would be such an education for an opportunity for a boy or a man to not only read a girl book, not just read a book or go to a movie, but actually move around a world in a body of a female or a feminine presenting person and see what happens. And so I was just listening with such fascination of the two scenarios that you described, that sometimes you do get more positive attention because you’re a woman and sometimes you get negative attention. But I wonder if that’s a really useful opportunity for men to have empathy, to be able to walk a mile in this other person’s shoes and see like, oh, this is different. That’s fascinating to me. I am curious too, like if you do experience sexual harassment, like being followed, somebody’s bumping up against you or doing something inappropriate that feels really uncomfortable, what do you do? Is there recourse? Like does it depend on where you’re playing? How do you handle that?

AR: It depends on the game. There are a lot of games that have blocking and reporting tools that’s basically an accepted thing in games. And a lot of them have become very robust so players can report inappropriate behavior and then the teams can act on it and potentially suspend or ban those players. There’s more blocking tools. There’s tools for, say, online games where you’re only grouped up with people for a short amount of time. You can start to some games, you can select, Hey, I don’t wanna be paired up with this person in this game moving forward. And they’ll say, “okay, for the next two weeks, you won’t get paired up with this person.” Or if you block them, you just won’t end up in games with them. So there’s tools for it, but they’re not always the most robust. And because games are enormous and they have potentially tens of thousands of players, that doesn’t always does solve the problem or get addressed in a timely manner.

I think the best pressure we can have is really just community-based; that players say something when they see it. And especially men too, because I’ve been in games where….so playing online shooters where as soon as a woman speaks, people are like, oh my god, it’s a girl! And it’s like two brain cells, just two brain cells just operating. And you’re like, “oh, you got me. Ha, I’m here.” But then they just harass you and then they say derogatory comments. And the idea is to make themselves feel better and laugh with their buddies. You know, it’s a community thing. And so the more we have people going, “Hey, that’s not cool”, or the rest of the team going, “Hey, that’s not cool.” That person will either become very quiet or very loud and they get real defensive about it because they think it’s normal, they think it’s okay because their peer group has said it’s okay. And so the more people we have in those spaces being like, Hey, not cool. Like that’s all you gotta do. Just that’s not cool. You don’t have to make a big deal out of it. You don’t have to stop everything you’re doing just like, nah. It discourages that behavior because it isn’t being supported by the community around them.

There was one incident where I was playing with a friend, this was years ago on Overwatch, and I was in a group chat with her. We were on the same team, so we have team chat and there’s six people in the chat. And so my friend and I are both in game dev and she was introducing me to one of her friends who’s also in game dev, and I was like, oh, that’s so cool. And we’re just having a conversation about game development and what we do and…it almost felt like he just couldn’t help himself. There was a guy on our team that was like, oh my gosh, you’re girls in the chat. We go, yeah, good for you. You spotted us. Good job. Like, where’s Waldo? Like, there you go. Wow. But we just stopped for a second…

AA: Oh my gosh.

AR: And then just continued our conversation. completely ignoring him. So yeah, I think having community pushback on what we think is normal or okay or acceptable is the best way for us to combat that kind of behavior.

AA: Awesome. Thanks for describing that. And I feel like, I mean now that it is changing so much where, we talked about at the beginning, almost half of players online are women now, and as that goes on hopefully men will just get used to it. Like you’ve been saying all this time of like, oh yeah, there’s other people in here. Why is gender such a defining factor? Why does it matter so much?

AR: Those stats are really interesting to me because back in like 2014, 2015, that was still also the case–that women were the majority if you count all games. And that is another caveat that I catch myself doing that too, ‘all games’ because then there’s this gendered idea of, well those aren’t real games like Farmville or browser-based games, you know, Bejeweled. And people go, oh, I’m not a gamer, but I do play a lot of this game. And it’s like, then you’re a gamer! I mean, you don’t have to accept that label, but those are games. And we have a history of discounting ‘pink games’. So like you’re saying, chick flick; ‘pink games’ is kind of the term for the games that are more targeted towards women and feminine interests and the thing is like…pink games have been around since the nineties and there have been games made by women, made for women all in that time. They just don’t…they’re kind of erased. They’re kind of suppressed in our history. And so we keep having this conversation of like, oh, women are just coming into the space. And it’s like, no, maybe women weren’t always a majority in terms of including all of games, but women have always been a segment of the game space, both the developer and the player space.

But yeah, I think it’s interesting ’cause I remember stats from like 2015 where they’re like, oh, if you count all mobile gaming women actually outnumber men. And the average player is a woman in her thirties or forties and that’s been around for a decade now. But it’s kind of the conversations we have because like we have our main tentpole games to get the most attention are not necessarily marketed towards women or highlight that women play them or are involved in them.

pink games have been around since the nineties and there have been games made by women, made for women all in that time

AA: Yeah. Wow, that’s really interesting. Okay, so I’m wondering if you can now shift kind of from character and character interaction and talk about the actual content of games. I’m curious if you see patriarchal influences in the content, what sort of narratives are being shared through gaming and how those narratives are either challenging or reinforcing patriarchal norms?

AR: So I think the biggest thing with games that have a strong narrative backbone is they are often reflections of the people who make them, the stories that they want to tell or they feel compelled to tell are more connected to their life experience. So because a lot of these games have been driven by men at the leadership positions, they tend to be more male-focused. And it’s actually an interesting trend for me to look at because you look back at like the eighties and nineties and a lot of the games, including arcade games and the early games are masculine; I’m going to defeat all the evils and save the princess. And this big macho character. I got all these big muscles and weapons and I’m just the coolest guy you’ve ever seen.

And then we get to the aughts, the early aughts and the tens, and you start to see a shift of games that are more about being a dad because all of these designers are now fathers. You look at like The Walking Dead, The Last of Us, God of War, like God of War is a great example because early God of War games were: I’m just this badass who slices through everything. It’s just super gory, super violent. And then the reboot of God of War is about how he has to take care of his son. And he’s figuring out what to do with all this rage and like how he sees himself as a father. And it’s like, yeah, this is just a reflection of the people who are driving these games. Which is why I mentioned I think the more we can put marginalized creators in the driver’s seat, the more we’ll see those stories represented and we’ll see less patriarchal, more diverse stories put out onto paper.

There’s also studios that I think are doing good work and branching away from what the expected norm is like. Life is Strange, for example. Life is Strange is a choice-based game where you play as a girl in high school, and there’s also relationships that you can form with another woman. And it’s not sensationalized, it’s not, you know…it is a character trait. It is something about those characters. They are attached to each other. They care about each other, and that’s something you can make a choice of as a player, but you can only play as this girl, and you can’t play as a boy in this scenario. This is about her story. So it’s very much driven by the perspective of a girl in high school. And so seeing more of those games get attention and visibility is the first step.

And then studios making the priority to bring more marginalized people, underrepresented people into their leadership spaces and their storytelling spaces is how we get a more equitable storytelling experience. I kind of just like to say that I don’t think the games that we already have need to completely go away. They just shouldn’t be the only thing that people think of, or they shouldn’t be the dominating idea. They should be one of many. And it’s a hard shift because it’s hard to convince people that games can be all these different stories and all these different perspectives. Because I think people often, when we ask for that kind of change, they feel threatened that we’re gonna take something away from them. And I’m like, no, I’m not taking it away. I just want us all to exist on the same plate.

AA: Mm-hmm. Like a microcosm of the whole gender issue kind of in the world. in any field. So interesting.

Okay. One of my last questions really quickly is, I’d love it if you could talk about girls or talk to girls maybe who are interested in getting into the gaming industry as a future career. What message would you have for them?

AR: I’d say find your community. Find people who are interested in building games around you and who share your perspective. Don’t let boys tell you you can’t do it. You’re allowed to be here. Your perspectives on games are valid. You should be able to make the stories that you wanna make that are important to you. You don’t have to fit someone else’s mold, and the perspective that you bring can only make a larger image stronger, even if it’s different, especially if it’s different. It creates more interesting and colorful stories for us to experience together. And then you will find that person who resonates with your story and goes, that’s me. I felt that. That’s who you’re making it for. The version of you that’s out there that you don’t know who sees the world like you do.

AA: That’s really beautiful. That’s awesome. Well, as we wrap up, Ashley, I’d love to know if there’s anything that you’d like to leave as a final takeaway for our listeners, and especially if there’s some action that we can take to make a positive difference. That’s kind of like a theme of the season is what are some action items that we can do to make the world less patriarchal and just a better and more just place?

AR: I think in terms of the gaming space, look for games that don’t get as much attention because there are literally thousands of games released every year, and there are a lot of very cool, marginalized, underrepresented creators that are putting games out there for people to play on your phone, on a web browser, on switch, on console. Itch.io is a great website for downloading really indie games, like really small experiences, but they kind of give you a better sense of what the indie space is doing and what ideas we’re all throwing around there.

And I just also just wanted to plug a couple of resources that we have in games. There’s Take This, which is takethis.org. It is a group that works on decreasing the stigma and increased support for mental health in gaming.

AA: Mm, amazing.

AR: Crash Override is a website that helps people who have been targeted by online abuse and crashoverridenetwork.com. They are a great resource. If you ever find yourself doxed or you find yourself the target of a hate mob online, they’ve got through all the Gamergate stuff, they know what they’re talking about. And last, I’d say supporting Black Girl Gamers; it’s an organization that has presence on a ton of social media, and they’ve got videos and creators that you can follow.

But ultimately, I’d say engage with the game content that you want to see more of, the change you want to see. So engaging with creators that inspire you, that you feel are bringing more diversity and more new ideas to our spaces, and just disengage with the people who aren’t, because there’s really no point in giving them any oxygen if they’re there to make our space less friendly to everybody.

AA: Great advice. And where can listeners find your work, Ashley?

AR: So I post about my dev stuff on Blue Sky now or on LinkedIn. You can find me @ashleyruhl.

AA: Okay, awesome. Well, I had a blast with this conversation. I learned so much and this was so, so interesting and valuable. So thank you Ashley rule for being with us today. Thank you.

AR: Yeah, I love this conversation. I love bringing more people into this topic.

AA: Me too.

you will find that person who resonates with your story and goes,

That’s me. I felt that.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!