“Students should be able to learn anything from anywhere”

Amy is joined by educator Ben Blair of Newlane University to discuss actionable steps towards building a more egalitarian education system, how new technologies can expand learning opportunities across the globe, and why we should question the popularity of time-based assessments, student competition, adversarial teachers and more.

Our Guest

Ben Blair

Ben Blair holds a PhD in Philosophy and Education from Columbia University. He is a co-founder and President of Newlane University. Started in 2017, Newlane is an online university with a mission to make quality liberal arts higher education accessible to anyone on earth by breaking down barriers of cost, schedule, and geography. Ben and his wife Gabrielle have six children. After six years in Oakland, CA they now live in Normandy, France.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Think back to your earliest memories of school. Who was in your class? What was the environment like? Okay, keep that in your mind, and now come on a little historical journey with me, where we drop in on a few schools throughout the ages. In Mesopotamia, only a limited number of individuals were hired as scribes to learn reading and writing, so only royal offspring and sons of rich professionals went to school. Most boys were taught their father’s trade or were apprenticed to learn a trade, while girls stayed at home with their mothers to learn housekeeping and cooking and to look after younger children. In the city-states of ancient Greece, during the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, affluent students were taught by private tutors, while the state educated young men in military training. During the Islamic Golden Age, Muslims established schools next to mosques where boys were educated. Girls also had opportunities for education, not just learning cooking and caretaking, and a Moroccan woman named Fatima al-Fihriya founded a mosque in 859 that later developed into the University of al-Qarawiyyin, which is considered to be the world’s first university. However, only men were admitted to that university until 1940. The Aztecs educated all their youth at home until age 15, when all children, regardless of gender or social class, went to school. However, at school, boys were taught writing, astronomy, statesmanship, and theology, while girls were taught homemaking and religion. In Europe, during the early Middle Ages, the monasteries of the Roman Catholic Church were the centers of education and literacy, the primary purpose of which was to train the all-male clergy.

Now I want to ask you, how different would your schooling have been if you had been born in a different time or place? If you are a man with high social standing, probably not that different, no matter when or where you were born. If you are a man from a humble background, or, if you’re a woman from any background, your experience and the trajectory of your life would have been vastly different. Today we’re going to talk about school, and specifically the philosophy behind different types of schooling. And here to speak with us is an expert on the topic, founder of Newlane University, Ben Blair. Welcome, Ben!

Ben Blair: Thank you, Amy!

AA: It’s so great to have you here today. I’m so excited for you to talk about school with us. Ben Blair is a co-founder and president of Newlane University. He holds a PhD in philosophy and education from Columbia University, and he is a co-author of The Kids Are All Right with his wife, Gabrielle Blair. So, Ben, I am a big fan of your work and a big fan of you as a person and friend of mine. And I’m wondering if we can start this conversation, and I must say, a conversation I’m really excited about, exploring the justness and the philosophical underpinnings of education in general. I’m so excited to dive into this topic, but I’m wondering if you can tell listeners a little bit more about you, where you’re from, the essential features of the way you grew up that brought you to be the person you are today.

BB: I’m happy to, and thank you. I’m kind of a fanboy of Breaking Down Patriarchy also, so I’m really pleased to be here with you, Amy. I currently live in Normandy, France, we’ve lived here since 2019. Before that, we lived in Oakland, California and we still kind of view Oakland as home. And I was born and raised in Provo, Utah. My father was a professor of linguistics at BYU. My father was really passionate about teaching and learning foreign languages, so that was a big part of our family. We always had a lot of visitors from other countries that came to work on some foreign language project my father was working on.

And then my mom, I thought of my mom as a stay-at-home mom, but she also taught ESL and she taught English at the junior high before I was born. My mom and dad worked building these foreign language courses, they would record these courses and my siblings participated in them, making like a Spanish course, a French course, a German course. And my brother just older than me marketed these and built it into a successful company that was later acquired. But just the idea of education and meeting different cultures and this passion for developing curriculum was something that was just part of our family culture.

And then after I finished my doctorate, I worked for a while at K12 that did online schools. They would have a different virtual academy for most of the states in the US. And I first started working with the foreign language program, it was part of the courses that my father and mother and siblings had contributed to. So I first started with that and then I worked on other areas, other curricula where I would review competitors’ materials and look out on what’s just around the corner in online education. So I spent about seven years deeply immersed in online education and what people were doing, and this was just when online education was starting to take a hold, long before COVID when everyone was doing education online. So I did that for a while, and then Newlane started. It really started when I was in graduate school and my co-founder was in graduate school, he was studying instructional design. It really was more a passion project about curriculum development. It was all this excitement of, hey, there are these massive open online courses that MIT and Yale and Stanford are putting out. And there are these open educational resources that people make to share and distribute widely and YouTube had just started, and there were all these videos, and it just felt like this world of education was opening up. It was like everything is open, everything is possible, we can learn anything. And my co-founder and I were super excited about this, and he had developed the basic bones of what would eventually become the Newlane platform. And it was basically just: here’s a platform for developing curriculum that can incorporate resources from the internet, no matter what the resources are.

And we really thought, “Some company’s going to do this and we’re really excited about it and whatever company’s doing that, we want to be part of that.” And we would go to conferences and we’d talk with people and were always on the lookout for like, “Who’s going to do it?” And we started doing other work, like I did this video series with our family and my co-founder was the lead technologist at a state university. And we kept thinking, “Why hasn’t anyone done this?” And then we were kind of at a place where we said, “Let’s just try this out. No one’s done it, let’s just go for it.” So we kind of struck out. We had this basic platform that he had built, and we started to just put courses on it and talk through, well, what features do we need? What are the essential features? We don’t want this to be a big, bloated platform. And because of our experience, we had a good idea of the things that we wanted and didn’t want. And then we launched. We didn’t start out– your introduction is super compelling, and we kind of arrived at what’s wrong with education, which is that exclusivity is this big looming monster in education. We didn’t start out thinking, “Let’s go tackle that.” We started out with, “We’re really excited about developing curriculum, and there are all these amazing resources, and the library of available resources is just continuing to expand,” so we were really excited about that. And then as we started talking with students who were interested, this idea of gatekeeping and exclusivity, that education was built to exclude a lot of people, that became the new passion for us. We’re really excited about developing curriculum, we have a great platform for building curriculum, but the heart of this is that quality education is a basic right and it should not be withheld from anyone.

AA: I love, I mean, sometimes you have a dreamer, a visionary, that can see, “This is wrong with the world and we need it to be this way and we want it to be more just.” And sometimes the problem is that that’s a really great idea, but if you don’t have the training to know how to create that change and to do it practically, in concrete details, then sometimes the change never happens because the idea can’t take off. It doesn’t have legs under it. So I think it’s really neat that you’re qualified, you have all this experience from the time you were little, it sounds like. Your parents are both educators and then you were educated at Columbia and you’ve done all this stuff. So you’ve got like, “I know how to do this,” and it sounds like afterwards it was like, “Oh my gosh, and this will make an amazing difference in the world to make the world a more equitable place.” Is that right? So you’ve got both pieces, which is really great.

everything is open, everything is possible, we can learn anything

BB: Yeah. I’m still very excited and enthusiastic about developing curricula. It’s something that feels like genetic inheritance that I get excited about in ways that other people don’t.

AA: I love it.

BB: Then the reward of now having graduates from Newlane and seeing their lives change is much more motivating and much more rewarding. And seeing how that could expand and address more people, this is what we want to do. We want to make education available and accessible. Our mission is to make quality online liberal arts higher education accessible to everyone on earth by breaking down the barriers of cost, schedule, and geography. We tried to build that into the basic DNA of what we’re trying to do. And then as we’ve seen that be realized, it’s been super, super rewarding.

AA: That’s amazing. I started the episode, the introduction, kind of as broad as you possibly could, right? Going back to the very beginning of what we know about education. But I just do want to spend literally one minute really putting a fine point on that. What are the problems that we’ve seen in education throughout history and through today? What are the inequities that we see?

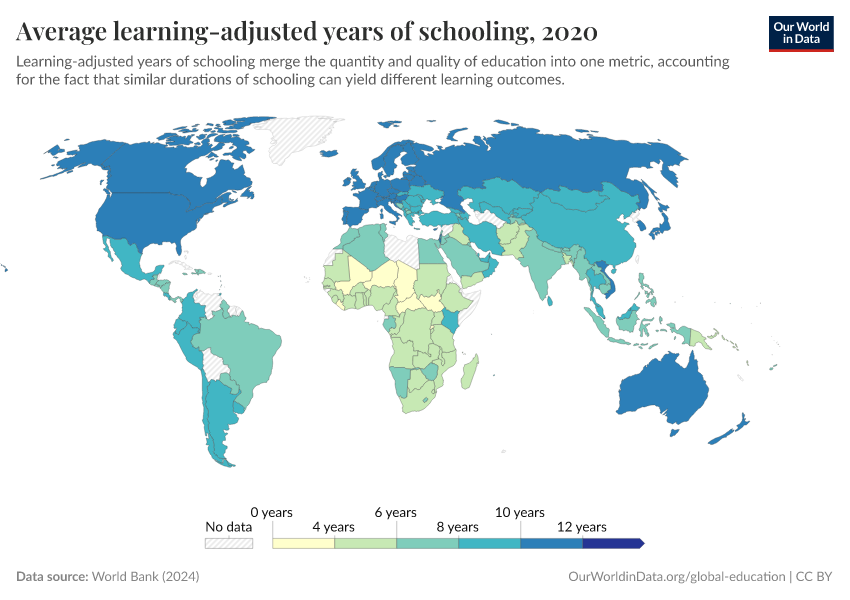

BB: I don’t know that I’m an authority on all the inequities in education, but I would say this looming monster of exclusivity. And I think your introduction really painted a compelling picture of that. Education has been reserved for a certain group of people and everyone else is excluded. And I think there’s been tremendous value for those certain people who got this education, they had this richer life in some ways than other people. I do feel like education is one of the most valuable heritages of the human experience. That not only have we developed a lot of knowledge and learned how to do a lot of things, but we’ve passed that on and we can pass that on and other people can learn and master these things and experience a more enriched life. And I would say we’ve definitely made strides, women can now go to college, people from different races can go to college. It’s not as exclusive as it has been. It’s really taken a long time to get there. And now the main barriers are cost, schedule, geography, and internet access and bandwidth. But with those, anyone anywhere in the world can enjoy and benefit from this invaluable heritage of ours.

AA: I love that.

BB: Today, we’re in this amazing position, this amazing time where these huge, enormous barriers have dissolved. And it’s a super exciting time to be alive. It feels so hopeful. And at the same time, and this is part of what motivated us, is that it felt like the whole world is open, we have access to unimaginable libraries, unimaginable stores of knowledge, and yet it costs $120,000 to get a degree. And you had to live in these places and you had to be available at these times when the classes were held. So, breaking down these barriers of access to this information did not translate into now everyone gets this education. And part of what we wanted to do is to contribute to expanding this and making quality education available and accessible to more and more people.

AA: Amazing. Well, let’s find out how you’re doing that. And I’d love to frame the conversation around your manifesto, the Newlane manifesto. Maybe what I’ll do is read you a phrase from your own manifesto and then have you expound on it a little bit and talk about how this idea is shifting and bringing more equity to education throughout the world. The first one I want to talk about is this, it says, “Education should be available and accessible to every person on earth.” And then it says, “Making quality education inaccessible or exclusive is immoral. Education belongs in the same category as shelter, clean water, and basic food.” That’s a bold claim. Tell us about that.

BB: Yeah, we wanted to write a manifesto that was aspirational but also meaningful and something that we could really take practical steps toward. And we wanted to make a firm stand, so I think casting this as a moral issue was important for us. That it’s not just “quality education is really valuable,” but “access to quality education is a basic right and it’s immoral to deny people that.” And we’ve had excuses to block people from that, but our work should be to remove barriers so everyone can access this. And I do think that a quality education is among the most valuable heritages of humanity. And denying some people that because of where they live, or when they’re available, or what they can afford is something with moral implications. We want to be on the side of opening up access, of making it available to more and more people. And I think putting it in the context of those other rights, that we could say, “People deserve shelter if they can afford it, and if they live in the right place, and if their schedule allows,” or to do the same with clean water and basic food, we would retract with horror at that. And we haven’t treated education like that, but it’s not a very far jump to see that access to quality education has similar implications as access to those.

AA: Can I share one little story from my own life, my own experience? I went to Cambodia a few years ago, and I was talking with one of the tour guides who was saying, like, “We love women here in Cambodia, it’s almost like a matriarchy. We have goddesses and the husbands are always like, ‘Oh, honey, whatever you want in the household.’” And I thought, “That’s lovely. Sure! I’m not going to doubt, and I think it’s cool that you pray to goddesses.” But we went to an elementary school and we were learning from them, playing games with the kids, and I talked to the principal of the school. It went up to fifth grade, so like age eleven. I had been playing games with the kids for quite a while, and there were a few that I thought were just so cute, and the kids were doing something else and I was looking out over them, and I said, “So how many of these kids will go on to high school?” And he said, “Almost all of them will go on to high school,” I think that he said to like age 16. And because I had already started studying gender, I said, “All of them?” And he said, “Oh, well, all of the boys.” And it turned out that the girls, this was their last year of school at age 11 because they were needed at home, taking care of children, taking care of the household, working on the farm, doing that work.

So, to your point of looking at it as a right, a human right for all people, that can be a philosophical thing that lives in your head. When you look at the actual faces of children and like, “At that table of those kids eating together, that one will get to go to school,” and you can tell where that’s going to take his life. “That one, this is her last year. She’ll be 12 next year, that’s her last year,” and picturing actually what her real life will look like without education. All else being equal – they live in the same place, they have the same families, they have the same communities – the only difference is gender, and gender determines schooling. It was really hard. All you have to do is look at a child to realize yep, food, air, clean water, shelter, access to education will determine everything for that person’s future. So, I’m with you. You just look at a kid and you will be converted to that way of thinking. Your next point in the manifesto says, “Education should be disconnected from geography. Students should be able to learn anything from anywhere on earth. With few exceptions, tying education to geography is a form of exclusion.” Can you talk about that?

BB: Yeah, this is another aspirational tenet of the manifesto, but it’s also something that we return to regularly to see how we can reach more people. Geography has been an enormous barrier. We might think in the United States, “Well, if you live in these neighborhoods or these states, you might not have access to this and this.” But if you think on the global scale, like you mentioned in Cambodia, then the scale gets huge. One of our earlier students is a mother from Zambia and she had tried to find a university and she didn’t have a place in her town where she could get a quality education. When I spoke with this student, she would say that there just weren’t any options, and her life was kind of blocked at that point. There weren’t really routes outside from where she was. But with an education that she could access just with access to the internet, it would change her possibilities, it would change her whole outlook, it would change her whole status in her community in profound ways that I can’t imagine.

And another student from Egypt, he had earned a degree at a local college, but he wanted to study philosophy. And he learned about Newlane and started studying and really excelled. The way he wrote papers and would perform on assessments was really exceptional, and I had this realization that had this person been raised in Massachusetts or Connecticut or Palo Alto, he could have been this all-star, the whole world bending over to help him. And what he can do and what this opportunity gives him is not only an opportunity for him to excel in something that he loves, but with that, this self-conception of who he is and what his potential is for the rest of his life and the future he can imagine now, that he couldn’t ever imagine. And I don’t use that term loosely, like, he could not imagine the sorts of things that can be in his future now. And it really was fundamentally a question of geography. You were born in this place, so your future has these options and that’s it.

AA: Wow, that’s really powerful. I’m so happy that you’re sharing actual examples of people that you know that you’ve been able to help, so keep those coming. You mentioned, geography and schedule probably overlap a lot of the time, right? I wanted to read the sentence about schedule, too. You say, “Education should be disconnected from a schedule. The most effective time to learn something is when the student is ready, not when the teacher or institution is available.” I’d never thought about that. You mentioned it a little bit before, but one thing that I thought as I was reading through it is that it seems like a typical university schedule where the teacher and the institution has decided the classes that we offer are these times, I’m guessing that that excludes, or at least it makes it very hard for students who need to work, which would perpetuate classist systems, right? The students who are coming from modest backgrounds who are not having anybody pay for their university education, they have to work, and then the difficulties compound for them, and then perpetuates this and they can’t get ahead. Am I reading that right? That schedule is a bigger deal than I thought, is what I’m trying to say.

BB: Yeah, it’s a huge deal. And in fact, our first foot out in marketing is that we have this reasonable tuition cost. It’s been really amazing to hear again and again from students that this schedule piece is as important, if not more important than the cost, the affordability of a degree. And if there’s a profile, the most prominent profile of our students, and this gets to what you talked about in the introduction and the whole idea of breaking down patriarchy. A prominent profile of a Newlane student is a mother who completed some college, and then because she started a family or needed to take on work obligations or needed to care for a family member, stopped her college education. She often would work to put her husband through school, and her husband not just through a bachelor’s degree but through an advanced degree, and she never finished college, never imagined that they wouldn’t finish college, never thought, “I don’t care about education,” but primarily because the schedule wouldn’t work. They couldn’t fit school into their schedule. And because of that, they didn’t ever complete a bachelor’s degree and the future that they had kind of promised themselves was just blocked at that point.

Not to say that everyone needs to get a bachelor’s degree and everyone needs to get an advanced degree, but so many of our students had thought, “Of course I’m going to get a bachelor’s degree. I’d like to get an advanced degree. Education is very important to me.” And those visions, those anticipations were cut off just because they couldn’t meet with the rigid school schedule. And then another piece that I come back to often is how flippant a school can be with saying something like, “I’m sorry, this course isn’t available ‘til next fall, so you’re not going to be able to complete your degree for another year. So just put your life on hold for one year while we wait for this course to be offered again in the fall.” This flippant attitude of institutions, because they hold all the power all the control of like, “We make the calls. This is what you signed up for,” how they are kind of flippantly treating people’s lives. These are people’s lives that are held up for a year. And every time I come back to this, I’m just astounded at how casual and flippant universities can be with people’s lives like that.

AA: Yeah, and it makes a real difference for them. It’s nothing to the institution and it’s everything to that individual student. Okay, let’s move on to the next tenet of this manifesto. It says, “Education shouldn’t be admission or permission based, but freely available upon the asking.” That’s really radical. Do you want to read the next sentence and then talk about it?

I’m just astounded at how casual and flippant universities can be with people’s lives

BB: “The current admission based system is a vestige of a scarcity model that could only fit a limited number of seats in a classroom. No one should have to be admitted or ask permission to learn a subject.” This is one of the tenets that it took me a little while to wrap my head and really be converted to this. I was kind of hesitant on this, just thinking, “Well, come on, not anyone can just go to medical school.” And the more we talked about it, the constraints and the barriers to education make it so that, yeah, only certain people go to medical school. And often it’s because they know it’s going to be an economically rewarding career, or that’s what their mother did, or their aunt or their uncle. And if we treat it not like we have treated it before, but if we just said, “Hey, anyone who wants to do this can do this,” then the people who are really interested, who want to do it for the good in itself of medical education, that it could attract these people. Instead of being like, “We’ve just narrowly confined and defined who can go to these places, and by doing that, we’ve excluded many people who could be amazing candidates.” I think of the example I gave of this student in Egypt who never would have thought, never could have imagined doing this sort of program. And I just imagine, you know, there’s that quote about Einstein’s brain, I forget who it was. They said something like, “I’m not as impressed about Einstein’s brain, but just knowing how many other equally as capable brains just go on unnoticed because we don’t have a way to kind of recognize and enable all these other people who are blocked off.”

AA: Yeah, can you even imagine? Oh, the grief of imagining all of the human potential that was not able to flower because there was nothing to foster it throughout the ages. That’s tragic. I guess the way to take that grief and channel it forward toward the future is to say, “Let’s do something about it,” which is what you’re doing. Some of the sub-points in the manifesto are that education shouldn’t have a prescribed completion time, and it shouldn’t be set to a specific time period in a person’s life. Can you talk about that a little bit? Because these are all like, whoa, they just challenged preconceived notions that I didn’t even realize I had just because it was based on what I’ve seen so far in my life.

BB: Yeah, education should not have a prescribed completion time. This student in Zambia that I mentioned earlier, she had worked with another university and she’s an amazing student. She would thrive at any school. And this school that she went to, she had to withdraw because the assignments were due at midnight on a certain date and she wasn’t able to finish the assignment then and there wasn’t flexibility. And then she found us and we’re like, “Yeah, we’ll work with you, we’ll be flexible. If you don’t master it right now, that’s fine, you can master it later.” What’s important is mastering the content for the course or the degree, it’s not mastering the content within this really rigid time frame. And then another example I have is talking with a Newlane professor, and the way a student passes a course at Newlane is that they meet with the professor in a one-on-one video conference like this, and it’s called a “course hearing,” and the professor has all the goals and objectives from the course and their role is to verify that the student has mastered all the goals and objectives, or not yet. And at the end of that conversation, it’s a 30-40 minute conversation, at the end of that course hearing, the professor either says, “I’m satisfied you’ve mastered all the goals and objectives. I’m happy to approve you for passing this course.” Or they say, “I’m not yet satisfied you’ve mastered all the goals and objectives. Go back and review the lesson on photosynthesis and we’ll schedule a follow-up hearing.” And I told this to one of our professors and he said, “Oh my goodness, that would have changed everything for me and my students. There are so many students that I feel like I have to give them a C but I know if I had another week, they’d be fine.”

AA: Yes.

BB: So, first, what is really important is, have they mastered the content or not? That’s what’s important. If we then tie it into, have they mastered the necessary objectives and goals before this date, then what are we doing? What happens is that we end up punishing students for not very good reasons at all.

AA: Yeah. I remember this TED Talk by Sal Khan, who founded Kahn Academy, and he talks about holes in the foundation of your house, and if you have to move on and keep building the second floor on top of a first floor that isn’t solid, the house is going to fall at some point. So the quality of the education is diminished by moving on before the student’s ready anyway. I feel like that’s not good for anybody. Again, it’s just like, duh, why hasn’t it always been like this? And I guess it’s true that it is hard if you have a classroom of 30 kids and they’re all moving at different rates. Maybe you have somebody who gets photosynthesis after 5 minutes, and somebody else needs a longer time. So I get why sometimes it’s not possible to individualize instruction, but I think it’s awesome, and that’s one of the benefits of the structure that you use at Newlane.

BB: And just to your point, our educational system in a lot of ways is built to say, “Let’s reward and celebrate the kids who learn photosynthesis in five minutes and let’s punish the kids who learn photosynthesis, but it takes them a few weeks longer.” It’s a ridiculous scenario when you think of it like that, but it’s how most institutions are kind of set up.

AA: Yep. Okay. Next one. And this has several sub-points that I’d love you to go into, Ben. The next one that I selected from the manifesto is: “Education should not be competitive or judged by other students’ achievements.” And that kind of goes along with what we were just saying about the different students in a classroom. But can you talk about some of the factors and the features of this statement?

BB: Yeah, I mean, just our most recent conversation that our education system is built to celebrate the people who master the stuff in a shorter time frame than others and then the question isn’t mastery, but the question is timed mastery, and I’m not sure how valuable that is. How this plays out is, I mean, I talked about what a course hearing looks like. It’s really an individual assessment. It’s competency-based education. That’s a term that maybe you and your listeners are familiar with. The idea is that what matters is that someone has mastered the material, not how long they’ve spent in the class, how much they participated in the class, whether they turned in all the assignments, it’s just have they mastered it yet or not. And what we’ve tried to do is lower the stakes. And I feel like we, in a lot of what we’ve done, have tried to push back against a lot of the culture in higher education where often professors are set up as an adversary, as someone who’s like, “I need to sort these students in some sort of arrangement.” And what we’ve tried to do is make the professor’s role really straightforward. You just assess whether they’ve mastered these objectives or not yet, and give them guidance if they haven’t, and that’s it. You’re not an adversary, you’re not a judge on the student, you’re a judge on their mastery of this material, and we want to be really rigorous in that and make sure that our records of what the students have mastered are meaningful and informative. I think what you said before that it’s a truism that it takes some people longer to learn things than others, but that doesn’t mean they should be punished for that or that their mastery should somehow be viewed as less than the mastery of someone who learned it faster.

AA: Yeah. One thing that I thought of when I read this was the fact that you’ve articulated it in the manifesto that it’s not a competitive environment and you shouldn’t be judged in comparison to other students. I’ve done a lot of volunteering with first-gen college applicants and then mentoring them through college, and I’ve known a few students who come from a low-income background, their parents are immigrants, their parents haven’t been to college, sometimes not even to high school, they get into a really great college and they’re so proud and they’re totally capable, but the imposter syndrome can be terrible. And that feeling that they already have inside of them, of “I don’t belong here,” or they’re just not sure that they measure up just because of their life experience. So if the environment there at college is at all comparative and competitive, which they usually are, students can drop out of college because of that. Not that they’re not academically capable, but because they just feel like, “I can’t compete, I don’t belong.” So it was really heartwarming to me to read that, that education should not be competitive or judged against each other. There’s just no reason for it. I really thought that was powerful as well. The last one I wanted to ask about is that education should not have a prescribed way of teaching. Can you talk about that one?

BB: Yeah. And sorry, I don’t mean to get into too many details about Newlane, but just to give context for how this works now and how we imagine it working in the future. At Newlane, a degree is made up of courses, courses are made up of lessons, lessons are made up of objectives, that’s our nomenclature for all those. An objective is a specific intended learning outcome. So an example of an objective might be, “Explain the process of photosynthesis” or “Re-tell Plato’s allegory of the cave.” It’s this very specific, granular, measurable objective. And for each objective, what we’ve done is we’ve either created instructional resources or we’ve curated them. So it might be like, “Here’s a video that explains photosynthesis,” or “Here’s a podcast that talks about the allegory of the cave,” or “Here is an interactive website that shows how photosynthesis works.” So each objective has different instructional resources, and often different types of instructional resources like a video and written text or a podcast episode. And then the standard is the objective. So we don’t really care how you learn to explain the process of photosynthesis, as long as you can explain the process of photosynthesis. It doesn’t matter if you learn it by reading a book, talking with your aunt, talking with a friend, watching a video, it doesn’t matter. What we’re after is, can you explain the process of photosynthesis? And then we work to rigorously verify that yes, this student can explain the process of photosynthesis. So that’s how we work now. And in the future, we would love for this to be an even more open place where it’s like a lot of people compete for better and better ways to explain the process of photosynthesis or better and better ways to explain the effects of patriarchy, whatever it may be. You can imagine there’s some random high school teacher in Panguitch, Utah, who actually can explain photosynthesis better than anyone at Harvard, but they’re not given any forum to do that. And if there could be a forum that that person could be rewarded for that, because that’s a really valuable skill.

it takes some people longer to learn things than others, but that doesn’t mean they should be punished for that or that their mastery should somehow be viewed as less than…

AA: Wow, that’s so cool. That’s amazing. Well, that makes me want to read, there’s one thing under this heading where you write: “Prevalent teaching approaches are often culturally, gender, or socioeconomically biased. While clear and explicit learning objectives can be universally agreed upon, the manner in which these are achieved should be as diverse as the student body.” That’s what I’m hearing you explain, is that different people have different ways of learning, and there can be different sources of that learning, and it doesn’t matter how, it just matters that they learn it. And I wanted to bring that up too, because unfortunately we’re to the end of our hour and I wanted to end on that, because this is a really concise articulation of a way that you are breaking down these unjust social barriers and acknowledging that prevalent teaching approaches are often biased in gender and socioeconomic factors and cultures. So you really are doing this work of dismantling these structures. My last question for you is, what are the specific ways that you see Newlane breaking down patriarchy and other unjust social systems?

BB: So, the internet and why the accessibility of the internet, has been just a huge part in breaking down a lot of those barriers. And what we’ve tried to do is break down those, focusing on those three barriers. Okay, the cost, let’s make a tuition that is affordable for anyone. And then a schedule, let’s make a schedule or let’s allow flexibility in the schedule so that students, if they don’t master the content within a really rigid framework, that’s okay, as long as they can master the framework. And then geography, if they can have access to the internet, they can master all of the objectives at any time. And we have seen, and this has been super rewarding to see this specific profile, a mother who completed some college but didn’t complete a degree. Now she’s completed her degree, and I’m thinking of a particular student who completed a degree in philosophy, and is now in a master’s program in philosophy at San Francisco State University. And first, there’s just that she feels confident and feels like, “Yeah, I can do a master’s degree in philosophy,” which is something she couldn’t have imagined before and now can imagine. And also just her view of herself and what her options and what the horizons for her are. I’m thinking of this particular student, but it’s this profile that comes again and again. They have thought that this door was permanently closed and it’s no longer closed. So in terms of breaking down patriarchy, if that is opening doors that have been closed to certain populations, it’s been really, really rewarding to help open some of those doors.

AA: That’s incredible, Ben. And I think you know, because we’ve talked and you’ve listened to the podcast too so listeners will know this, but me going back to graduate school, it really did change my life. It really did. And way after the fact, after I had already gone to get my master’s degree and I read The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan, I think it was toward the end of the book where she is addressing– and this is in the early ‘60s, and women say, like, “Once I start to wake up and see whoa, whoa, whoa, I’ve been stunted, I’ve been sidetracked. I got off the freeway that was taking me toward my potential, and now I’m kind of at this dead end. What do I do?” And Betty Friedan said, “Go back to school.” That is the thing that will get you back on the freeway. Then you’ll have all these paths open up to you from there. And that was validating too because I was like, “That’s what I did!” And that really is what had the impact. So for you to make that available to women, as you’re describing, it’s unbelievably helpful, and that does dismantle patriarchy. And then, like you said, that woman shows up in all of the areas of her life differently, empowered, and with confidence, and with critical thinking skills, and all the things that we get from education. I just want to, again, kind of sing the praises of this initiative because it’s breaking down patriarchy and classism as we talked about in some ways, those geographic boundaries reinforce racism and all of the different things that keep the human family from reaching their potential. I’m just so inspired by your work, Ben. And maybe the last question I’ll ask is where can we find out more about Newlane University and how can we support this incredibly important work?

BB: You can find us at newlane.edu. And if what we’ve been talking about makes you think of someone who’s like, “Oh, this could be a good fit for this person,” send them to Newlane. And as you were talking about your experience, I’m all over again feeling what a loss this world would have been had you not gone back to school. Just look at this amazing world you’ve opened up and that it can track back to going back to school makes me feel all the more confident about the work we’re doing.

AA: Thank you for that, and thank you for your work. I find it so beautiful and uplifting and I highly encourage listeners to check it out. Ben Blair of Newlane University, thank you so much for being here today.

BB: Thank you, Amy.

what matters is that someone has mastered the material

not how long they’ve spent in the class

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!