“no work for liberty is ever lost”

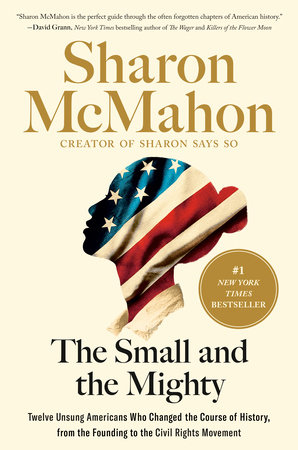

In our first episode of Season Five, Amy is joined by Sharon McMahon to discuss her book, The Small and the Mighty, honoring the histories of overlooked but world-changing women in America’s history and discussing how we can all gain wisdom and take heart from their bold examples.

Our Guest

Sharon McMahon

Sharon McMahon is a #1 New York Times bestselling author, educator, and host of the chart-topping podcast Here’s Where It Gets Interesting. McMahon became known as “America’s Government Teacher” during the 2020 election for her viral efforts to combat political misinformation. Her knack for breaking down complex topics with clarity, humor, and a steadfast commitment to facts has attracted a community of one and a half million followers—affectionately called the “Governerds.” McMahon’s newsletter, The Preamble, is one of the largest publications on Substack, providing historical context and non-partisan insights to help readers navigate today’s political landscape. Her debut book, The Small and the Mighty, has been celebrated as one of the year’s top reads by Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and Goodreads, highlighting the unsung heroes who shaped America.

Beyond education, Sharon McMahon has led philanthropic initiatives that have raised over $11 million to address critical needs, from medical debt relief to disaster recovery. She inspires audiences with a message of hope: history shows us that even small actions can create powerful change.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: On one of our very first episodes of Breaking Down Patriarchy, I shared the following quote from Gerda Lerner’s The Creation of Patriarchy: “Women are and have been central, not marginal, to the making of society and to the building of civilization. But until the most recent past, historians have been men, and what they have recorded is what men have done and experienced and found significant. They have called this ‘history’ and claimed universality for it. What women have done and experienced has been left unrecorded, neglected, and ignored in interpretation. Thus, the record of the human race is only a partial record in that it omits half of humankind and it is distorted in that it tells the story from the viewpoint of the male half of humanity only.” I thought of this quote when I read Sharon McMahon’s new book The Small and the Mighty. McMahon opens her book by saying that most histories have celebrated “the men with the best military strategy, the people with the most ships, those with vast fortunes and political power.” But she says that it is the people outside the dominant caste, those whose impact has been missed by people who either don’t know where to look or have intentionally decided not to. It is their stories that she has come to find the most interesting. The Small and the Mighty brings so many important and fascinating stories to life. And to talk about them today I am thrilled to welcome author, teacher, and historian Sharon McMahon. Welcome, Sharon!

Sharon McMahon: Oh, I’m so excited to be here. Thanks for having me.

AA: In case you’ve been living under a rock, listeners, for the past few years, Sharon McMahon is the #1 best-selling author of The Small and the Mighty: Twelve Unsung Americans Who Changed the Course of History, From the Founding to the Civil Rights Movement. She is the host of the incredibly successful and fabulous podcast, Here’s Where It Gets Interesting, and she’s a thought leader with an educational, inspiring Instagram account @sharonsaysso. She’s known as America’s government teacher, and she leads what are affectionately referred to as “governerds” all across the country. I count myself as one of those governerds, and I also highly recommend subscribing to Sharon’s substack called The Preamble. Sharon, I just have to say that I love The Preamble. I’m particularly really eating up your profiles of the current Supreme Court Justices.

SM: Oh, thank you!

AA: Those are so fascinating and it’s so important. I forward them to my family and my friends. I’m just a huge fan of your work and I’m so thrilled you have you here.

SM: That’s so nice. Thanks for reading, I appreciate that. Those profiles are, I think, really interesting. They take a long time to put together, but I think that these are things that most people don’t know, and we need to know about our Justices.

AA: Yep, I agree. And I can tell they take a long time to put together. I’m a writer myself, and I just marvel at how prolific you are in churning out really incredible content.

SM: Thank you.

AA: Let’s start out by having you introduce us a little bit to your personal background. I’d love to know who you are and what brought you to the work that you do today.

SM: My background is in education. I’ve been a long-time classroom teacher, and before that I became interested in history and government because of a newspaper route that I had as a child. I read the newspaper every day while I walked my three-mile route, and then I also had unfettered access to the library, which was near my home. Then I later would take the bus down to the big main branch library. I spent so much time reading and being able to follow whatever the whim of the day was, learning new things. So that’s really the genesis of how I got to know a lot of the things that I know. And then I became a classroom teacher, and as a teacher you learn to anticipate what you’re going to get asked. You know, like, “they’re not going to know about this thing” or period one asks a question and you know period four is going to have the same question. So all of that informs the work I do today. And it’s a different thing teaching adults on the internet, but in some ways it’s also the same. In some ways, it’s not that different.

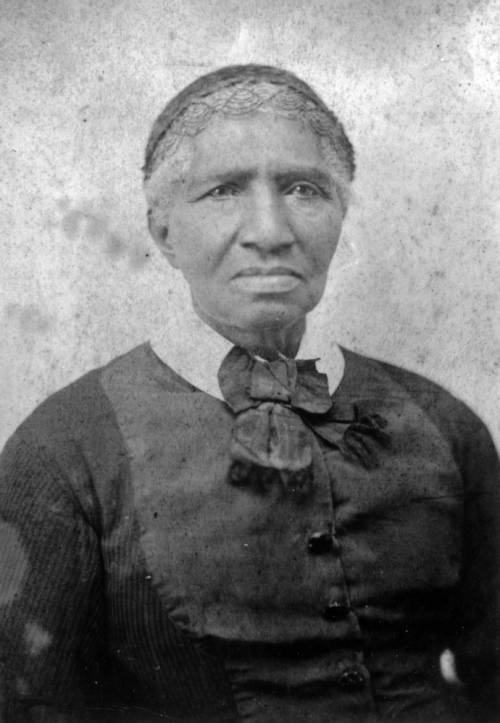

AA: That’s awesome, thank you. Okay, let’s talk about the subjects of your book. I loved your book so, so very much, and I’d love to spend some time with some of these people. You introduced your book with this beautiful story about the Northern Lights and your realization that there are these incredible stories, and you make the analogy, it’s a metaphor, but these histories that are there but we just don’t know about them. So for you to bring these really inspiring stories to light, I’m just excited to share a few of them. And then if you haven’t bought the book yet, go buy it right now, everyone who’s listening. But I’d love to start with Clara Brown. I have to say, I’m from Colorado and I loved all of our history units all through my elementary school. I know I have never heard of Clara Brown before, and I was so sad that we didn’t learn about her in our state history but I’m so grateful that I know about her now. So can you tell us about Clara?

SM: Yeah. Clara Brown was an enslaved woman who was born enslaved and she unfortunately watched her children and spouse get sold off to different owners. She herself was sold off to someone else. And she sort of vows that she will someday, she hopes they will meet again, it’s really the fondest wish of her heart that she will find her children again one day. And throughout the course of her life, Clara is sold to another owner and then she is emancipated. She is set free when her owner dies and she is able to seek a job for pay. And being able to seek a job for pay as a free woman in her fifties is something she’s never had the opportunity to do before. And it takes her across the country from where she had been enslaved in Kentucky to Kansas, to Missouri, and finally, to Colorado. She hears about opportunities in Colorado that really fascinate her, and she partners with a man who is a wagon train master, a well-known person who leads groups of people across what was referred to at the time as this sort of American desert, we refer to it now as the Great Plains. And she walks hundreds of miles to what will become the state of Colorado and becomes a wealthy woman through the fruit of her own labors.

I say in the book that if there was a picture that needed to go next to the phrase “self-made” in the dictionary that Clara Brown should be next to it. She truly comes from absolutely nothing. She was enslaved, she had not one possession to her name, and she becomes wealthy through her own hard work. She begins to invest in all kinds of interesting things, properties, mining claims, et cetera. And one of the things that I think is most interesting about Clara is that, of course, she changes the course of Colorado history. She becomes friends with the governor, she becomes friends with the mayor, the governor sends her on these sort of missions on behalf of Colorado, she becomes an official pioneer of the state of Colorado. But one of the things that I think is most interesting about her is that when she became well off, she began investing in Colorado’s infrastructure. And we think of infrastructure today as fiber optic cables and bridges, but at the time, infrastructure was what was holding your communities together, and often those were things like houses of worship and schools. That was the infrastructure that kept communities moving forward, those communal bonds that were formed. Americans– Humans are not meant to live in isolation. Humans have evolved to live in communities.

And Clara invests in churches and schools that she has no hope of attending. She has no intention of attending. She’s no intention of becoming Catholic, she’s a Protestant. She has no intention of going to the Methodist church or the Presbyterian church. She belongs to a different church. And yet it is her money that funds many of these church buildings so that other people can have important communities too. And some of these churches actually still exist. They’re on the national register of historic places. You can go online and look up some of the churches that Clara Brown contributed to. There’s a beautiful church in Central City, Colorado that Clara contributed half the amount of money to its construction, it took years to build. It’s a beautiful stone church that has all kinds of really cool paintings on the inside and they sent away for a pipe organ and the pipe organ has really cool paintings on each of the pipes. And again, all of that, Clara does not go to this church. And it really strikes me. Who is contributing to churches they do not belong to? I don’t know anybody that does that today.

AA: No, no.

SM: If you go to a house of worship, you give to your own house of worship. You don’t give money to somebody else’s church, let alone pay for half the construction of a church building. It takes like six years to build. But her belief was that everyone should be free, and that meant free to worship in the way that you saw fit and the infrastructure needed to worship in the way you saw fit. And I will save some of the story for all of the ways in which Clara changes the face of Colorado, but suffice it to say that her contributions were so renowned even during her lifetime that she developed such a unique and large reputation that people were writing about her in East Coast newspapers. People were writing about her by her nickname, which became “Angel of the Rockies.” And what a legacy to be known for, what a legacy to have spread far and wide. She did, in many ways, what Americans today wouldn’t even consider doing. And there’s a really, really interesting twist to her story that I’ll let the reader read about. Those are just a few things that I really love about her.

if there was a picture that needed to go next to the phrase “self-made” in the dictionary that Clara Brown should be next to it

AA: Yeah, me too. Like I said, I’m so grateful to know about her. Next time I’m in Colorado I’ll go to Central City and I’ll go to that church. And you said that there’s a stained glass portrait of her in the Supreme Court chambers in Denver.

SM: Yes.

AA: I can’t wait to see that. And I’m so grateful to have her introduced into my life. And I do want to say too, I mean, our podcast is Breaking Down Patriarchy, so we’re always looking at systemic issues and what are the systems that were put in place hundreds or thousands of years before we lived and we work within these systems. And I loved how in Clara’s story, and actually all of these people, you really bring to the fore those unjust systems of sexism and racism that she encountered. There’s one passage that talks about how when she was paying for a wagon train, she had to pay double the price that a white man would have paid.

SM: That’s right.

AA: And these egregious injustices that she encountered and her resilience and her strength in overcoming them was just incredibly inspiring to me.

SM: She would not have had the tools to say, “Here’s how I will fight against the patriarchy, here’s how I will change the systemic issues.” That would not have been a tool she would have had the ability to reach for, and yet she did what so many of our forebearers have done when they have enacted major changes, which is the next needed thing. She kept putting one foot in front of the other. And it can be very easy to feel like the problems are too big. They’re monumental, these systems of patriarchy, of racism, of misogyny are many, many, probably millennia old. That’s probably not even exaggerating it.

AA: It’s not.

SM: And it seems like, how would I fix a 5,000 year-old problem? You know what I mean? How would I personally fix that? But most of the stories in this book show how a single individual absolutely can impact the course of history. And Clara is just a really, really beautiful example of that.

AA: Yeah. She sure is. Okay, let’s move on to another one. Katharine Lee Bates. I did know her name, and I thought “she wrote a really famous song, but I don’t remember which one,” and then I learned all about it. But I would love you to talk about Katharine Lee Bates. And specifically, I have to say, I got choked up when I read what she wrote, I think in a journal, she said, “I would study and study and study and know, and know, and know.” She just had this yearning for knowledge. Can you tell us all about Katie? I think she went by Katie.

SM: Yeah. Katie is her mother’s youngest child. She’s born on the coast of Massachusetts and her father was a congregationalist minister and he died shortly after she was born, leaving her mom a single mother. And there are a few different people in this book who are single mothers, and single motherhood has always been one of the most difficult paths to journey. It’s still very, very challenging to be a single mother, but there was a big social stigma associated with being a single mom in the past and it was quite difficult to support your children because of these sexist systems that closed women out from a huge variety of educational opportunities and a huge variety of professional opportunities. Women had to piecemeal together, you know, “I’ll do some sewing, I’ll do some gardening, I’ll take in somebody’s laundry.” And you see that over and over. There’s a very small proscripted set of acceptable professions that women are allowed to pursue. And Katie’s mother encounters that system. And Katie’s mom even describes in a letter to a friend how profoundly exhausted she is. And it strikes me that her mom is not just profoundly physically exhausted, trying to care for all of her children, but she has to be profoundly emotionally exhausted trying to make a way for her children. And she, of course, has to lean on her older children to help make ends meet, and her son picks up some of the slack.

Katie is her youngest child, and often older siblings feel like the youngest kid gets away with everything, you know, like, “Why does she get to go to that thing when she’s 15? I had to wait until I was 18.” If you’re an older sibling, you know what I’m talking about. I’m an older sibling, like, “Why does the youngest kid get to do everything?” My older kids say that about my youngest kids. And I even say this in the book, that Mama is tired. By the time the youngest child comes around, Mama is tired and she can’t care about everything equally the way she did, with the same hypervigilance she did when her older children were younger. So Katie kind of gets away with stuff that her older siblings can’t. She spends her childhood writing in her little journals underneath the lilac tree and her older siblings are like, “We’re out here trapping muskrats to keep the family afloat, and you’re writing and picking flowers and swinging in the swings.” But Katie, even as a child, observes the truth of the world. And her observation, even as a child, is that men can do whatever they want and women are supposed to do sewing and domestic labor. That is what women are good for. And throughout her entire life, she rails against the needle, as she calls it. Why should women have to do sewing? And even women who have professions, she says, and she does later go on to have a profession, they’re still supposed to sew, while men who become professionals don’t have any domestic labor to do.

She writes in one of her journals at the time, you know, her fascination with the world. She’s writing a letter to Mr. Sun, “How do you glow so brightly? What are you made of?” And she says, as you mentioned, her fondest wish is that she could go to school as much as she wanted and she would learn and learn and learn and know, and know, and know. And she knows that that is not the normal route that a woman is allowed to take. And through a series of fortunate events, she does become an academic. She’s allowed to go to Wellesley at the time Wellesley was being formed. She later becomes a faculty member there and she does devote herself to knowing and knowing and knowing, but her ultimate contribution to history is not in the things that she knew, it’s in the things that she wrote. And the things that she wrote changed the hearts and minds of tens of millions, maybe hundreds of millions of Americans in ways that she could have never predicted.

But had she not had the opportunity to know all of the things that she did, had she not had the opportunity to travel, which was one of her favorite hobbies, she would not have been able to write a poem that all of us know, that’s now set to music, but that poem is “America the Beautiful”. And when you think about the lyrics of “America the Beautiful”, in each verse, she’s describing something beautiful about the country that she has personally experienced, like the amber waves of grain, purple mountains majesty, and she then describes some sort of problem or aspirational hopes of a way that we can overcome it. She’s describing what America at her best will be in each verse, and each verse sort of follows the same formula, but it does so in such a stirring way that there’s almost nobody who would listen to that song and feel nothing. There was a huge movement to make “America the Beautiful” the national anthem, and that movement has never really died, honestly. Our current national anthem, there’s a lot of great things about it, and it’s very sentimental to people now, but our current national anthem is really hard to sing.

AA: Hahaha, that’s true!

SM: It’s very hard to sing. It’s also very militaristic.

AA: Yes, it’s war-centered!

SM: Yes. Yes. And “America the Beautiful” is about, in the words of Jessye Norman, it’s about this land and the people of this land, and the beauty that is our brotherhood in a way that the current national anthem is not.

AA: Yeah. Count my vote for “America the Beautiful”. I didn’t know that was a movement, but sign me up.

SM: Yes, yes. They really lobbied hard, the National Hymn Society, which is a religious organization, lobbied hard for the president to make “America the Beautiful” the national anthem. The Star Spangled Banner has only been the official national anthem since the 1930s.

AA: Mm-hmm. I remember you saying that. I was shocked, I had no idea. So interesting. I want to bring out one more detail from Katie’s story, and that is when she got the teaching job at Wellesley, she wrote to a friend, “I am dreading next year horribly. I am a regular coward and I would like to take my heels and run for it.” And I loved that so much! It was so relatable, and I’m so grateful that you put that little morsel in there for all your readers because I think all of us feel that way. And I thought maybe even you, Sharon, in front of all these giant book tours and all of the publicity that you’re doing. I wonder if sometimes you feel like, “I don’t know if I want to do this” and feel scared. And then if that’s true, how do you overcome your fear so that you can do the work that you were born to do?

SM: You know, I love that quote from her, not because I want her to feel afraid, but because as you mentioned, it’s so relatable. We tend to think about great Americans as, you know, they ride on the back of a bald eagle and they have a sword and they’re fearless in their pursuit of greatness. That’s how we tend to view great Americans. They marched into battle. And that statement shows, “No, in fact I was terrified and I just kept doing the next needed thing. And I didn’t want to do it.” I mean, I think most of us have experienced what I will sometimes refer to as the anticipatory dread of doing something we really don’t want to do, or we think is going to be terrifying and we think about it and the dread, the anticipatory anxiety of like, “Oh no, I don’t want to do that public speaking next week. I do not want to fly on an airplane,” whatever it is. Most of us have experienced that. I absolutely have many times. I used to be terrified to fly on planes, and I would spend weeks and weeks and weeks obsessing about this, “Oh no, it’s going to be so scary. It’s going to be so terrible. What if there’s turbulence?” Well, I’m happy to report that I had since gotten over my fear of flying, but it used to be absolutely terrible.

I was terrified and I just kept doing the next needed thing

Before embarking on this giant six-week book tour where I’m in 15 cities in front of huge audiences, thousands of people in each city, I did have anticipatory anxiety. Not that I was afraid of talking to an audience, because I knew the audience was going to be friendly and they were all excited to see me. And, you know, I was excited to see them. But thinking about being away from home for six weeks, I’m naturally kind of a homebody and like, “Oh, I have to be on all these planes and all these airports are going to be so stressful and I don’t know if I should do it” and blah, blah, blah. I absolutely was concerned about whether or not I would even be able to pull it off. And I will say, of course, as it’s almost always true that the anticipatory anxiety is worse than the actual doing, once you’re actually doing it, it’s fine. And that’s absolutely how I felt. I’m so glad I did it. It was a once in a lifetime experience, I had so much fun, but I absolutely was like, “Oh no, what have I gotten myself in for?” shortly before leaving. I absolutely did.

AA: Yeah. Well, that’s good to hear. I hope that listeners take that away from that passage and from what you just shared. And this is something that I talk about with my kids sometimes too, is when to listen to your voice and when not to. When to listen to your mind and when not to. But there are these things like, you know, this was her taking a job at Wellesley and she was so passionate about education. And you, of course. In order to reach our potential, there are times that our brains are going to be screaming, “No, no, no, it’s too scary!”

SM: Totally.

AA: And just knowing that everybody feels that way and to take that next brave step in order to, again, to do what we were wanting to do and make the contribution that we’re here to make. So again, thanks for including that. So helpful. The next figure that I would love you to talk about, the next example of the small and the mighty doing amazing things is Rebecca Brown Mitchell. And again, this was a woman I had never heard of, and I’ve lived in the Western United States my whole life. I have family in Idaho but I’d never heard of her and I’m so grateful I know about her now. So can you introduce us to Rebecca?

SM: She is a fantastic example of what breaking down the patriarchy means. She truly is. Because even in the 19th century, when she lived, when her first husband dies she is imprisoned in what she calls the “iron cage of the law,” where the patriarchal laws were such that women were not allowed to inherit their own familial property, they were called coverture laws. Women needed to be covered by some kind of male relative, whether it’s a brother, a dad, a husband. So when her husband dies, she is only allowed legally to inherit two things: the family hymnal and the family Bible. She has no legal right to her own clothing, to the dishes that they got as a wedding gift, to her children’s belongings. And even at the time, she is like, “This is bananas.” If she had been that kind of woman, she would have been like, “This is BS. This is a BS rule.” And she wants to make something of herself. She longs to do something more than just sewing. No shade to sewing, I love needle crafts, but you know what I mean? I don’t want to be obligated to only have that as my job. So she tries to find a college that will accept her. And over and over she’s told no, as a single woman, she eventually does get remarried to her husband’s brother and then their marriage dissolves. So now she has not just, “Oh, you’re a widow,” but it’s unclear if they just separated or if they legally divorced, there aren’t any records of it. Nevertheless, now she’s a widow plus a divorcée or the societal equivalent of whatever that looks like in people’s minds. And over and over these colleges tell her, “No, you can’t be admitted.” And she’s applying to religious colleges, she wants to become a missionary, and none of the religious organizations will accept her. She persists and eventually one of them relents and lets her do some sort of correspondence-type work and she decides when her children are grown and her youngest child is a teenager that she is going to head west.

This is a theme in the book, is that many women sort of revolted against this very fully formed patriarchal society of the eastern part of the United States and sought refuge in the American West where things were different. The women of the West could vote long before women of the East. You could vote in Utah way before you could vote in Massachusetts as a woman. And that’s one of the things I talk about in the book, too. Why women of the West? What was the West doing that gave women rights that women of the East didn’t have? She gets on a train with her teenage daughter and runs out of money in Eagle Rock, Idaho, what later becomes Idaho Falls. And this is one of the things that I love about her. Throughout the rest of her life, first of all, she is in her forties and fifties when she’s embarking on this journey. She is not some hot 21 year-old. She is not in what we would call today the prime of her life. If you look at pictures of her, she is dressed head to toe in ruffling black taffeta. Very old school like “My husband died, I’m wearing all black for the rest of my life” type situation. She looks like an older woman wearing just copious amounts of floofy black taffeta fabric. And you know that everything that she tries to do, she’s starting schools, she’s starting churches, she’s starting suffrage movements. She’s working to gain women the right to vote. She becomes a very well renowned public speaker. She’s traveling by train and by wagon throughout all of the mountain passes into Montana and into Utah and all of these very, very rural, cold places where travel is difficult so that she can be a speaker in all these different events.

You know that tongues were wagging. People were like, “Who does she think she is?” She’s referred to in newspapers as a “tiny tornado,” And that shows that other people observed the type of energy, the vigor with which she pursues suffrage. And she ultimately is one of the women behind the passage of the amendment in the state of Idaho that allows women the right to vote. And she even gives these exhortations when people are like, “Why Idaho?” It’s not like Idaho was a bastion of progressivism, right? That’s not how Idaho was or is today. She even said, “Why not do the unheard of thing? Let Idaho be among the first.” and I love this phrase, “why not do the unheard of thing?” And she goes on to do something that she’s the first woman in the world to do, and becomes famous in her lifetime for being the first woman in the world to do this thing. But that phrase, “Why not do the unheard of thing?” was something that the men of Idaho had really not even considered. They were wanting to maintain the status quo and here women are pressing them to do the unheard of thing. Let Idaho be among the first. And it is their persistent concerted efforts that change things, not just for themselves. They knew that gaining the right to vote was not so much about themselves. Rebecca is like 60 something years old at this point. This is for them. The women of the future and their labors were for all of us, you know, it was not about “give me a million dollars so I can buy my feather hats.” These labors are on behalf of descendants they did not even know yet. And to me, that is such an encouraging thing to think about.

There’s another character in the book Inez Milholland, who does not accomplish some of her goals. They say about her after her death that no work for liberty is ever lost. That it becomes part of the fabric of the nation, and I think that’s such an encouraging thing to think about when we are working to change systems, when we’re working to change deeply entrenched ideas that are thousands of years old, that no work for liberty is ever lost. Even if you don’t pick up the ball and carry it across the finish line yourself, it changes the fabric of the country, it changes who we are as a people. And it’s just something that I find valuable to sort of hang on to. That even if I don’t see an achievement in my lifetime, that does not mean that my labors were in vain. And even though Rebecca does see Idaho women gain the right to vote, that doesn’t mean that she achieved everything that she wanted to. It doesn’t mean that tongues didn’t wag behind her back. It doesn’t mean that she didn’t feel the fear and do it anyway. And it occurs to me that so many of us are not necessarily afraid to fail, we’re afraid to let other people watch us fail. And that’s what keeps us stuck. It’s not that we might not achieve our objective, because we fail to do things all the time. We fail to work out the number of times we say we’re going to. We fail to eat the right number of servings of vegetables. We actually fail at things all the time. It’s other people watching us fail that we’re afraid of. The people who go on to be great Americans that history regards with kindness, that history says, “these are people worth remembering,” they are not the critics, they’re the doers and they’re the people who allowed other people to watch them and try and fail and try again. And to keep doing the next needed thing.

AA: Beautiful. This reminds me, if I can share this really quickly, of a conversation that I had yesterday with a friend of mine, a woman of color, and we were talking about doing anti-racist work. And we’re recording this pretty closely after the election in 2024, and there’s a lot being talked about about Black women just being exhausted and needing to rest and about white women needing to step up and do more. And talking with this friend of mine yesterday, I said, “I think that sometimes white women are scared of doing it wrong.” And she said, “Yeah, scared of people calling them out and canceling them. And they’re scared of being shamed publicly.” And I said, “Yes, for sure. And also really scared of causing additional harm. Scared of hurting people. They’re scared of making those mistakes.” And she said, “Yeah, I think that maybe a lot of what white women need is the resilience to be able to have the courage to make mistakes and keep going.” And that is exactly to your point, Sharon, and how you wrote it in the book, the courage to let people see you make mistakes and fail. And that’s really scary. And especially when the stakes are really high, but that was what was on my mind. It’s one thing to make a mistake like not show up at the right time for a meeting that you scheduled, like I did. It’s another thing to make a mistake and do actual harm, like harm comes from it. And to be able to pick yourself up and say, “I’m sorry, I learned” and just have that humility and then the courage and resilience to be like, “and I’m going to try again, I’m not going to give up.” That’s what came to my mind when I was hearing that.

SM: Yeah, I hear you. I hear you. And I know where you’re coming from and where your friend is coming from. When you’re talking about people being afraid to cause harm, afraid of doing it wrong. And we let that fear, whether it is real or whether it is imagined, and I think sometimes, yes, people have real fears about like, “Well, I did it before and I hurt somebody” so they’re sort of once bitten twice shy. But I do think that people use that as an excuse. They use the excuse to keep them from actually trying. They use it as a cover for “I don’t want to hurt anybody so I’m not quite sure what to do.” The answer is to just do the next needed thing. That’s what forebearers have done. Sometimes they made a mistake and realized, well, this was not actually helpful. And you know what, that actually is tremendously useful information. If you try something and it doesn’t go well, then you know, okay, that was not the right thing to do. And you don’t have to waste your time doing that again in the future. I’ve heard this advice given from the titans of industry, people who have made billions of dollars, who have been wildly successful at whatever their venture is. People have said, “what’s the secret to your success?” And over and over, people have given some variation of the phrase “fail faster,” try again and get it wrong faster, because failure is incredibly instructive. Failure is incredibly valuable information that you can actually not gain by thinking, by just ruminating on it, by reading up on it. You can only gain that super valuable information from trying and failing at something. Fail faster is a really useful way to think of it.

Even if you don’t pick up the ball and carry it across the finish line yourself, it changes the fabric of the country, it changes who we are as a people

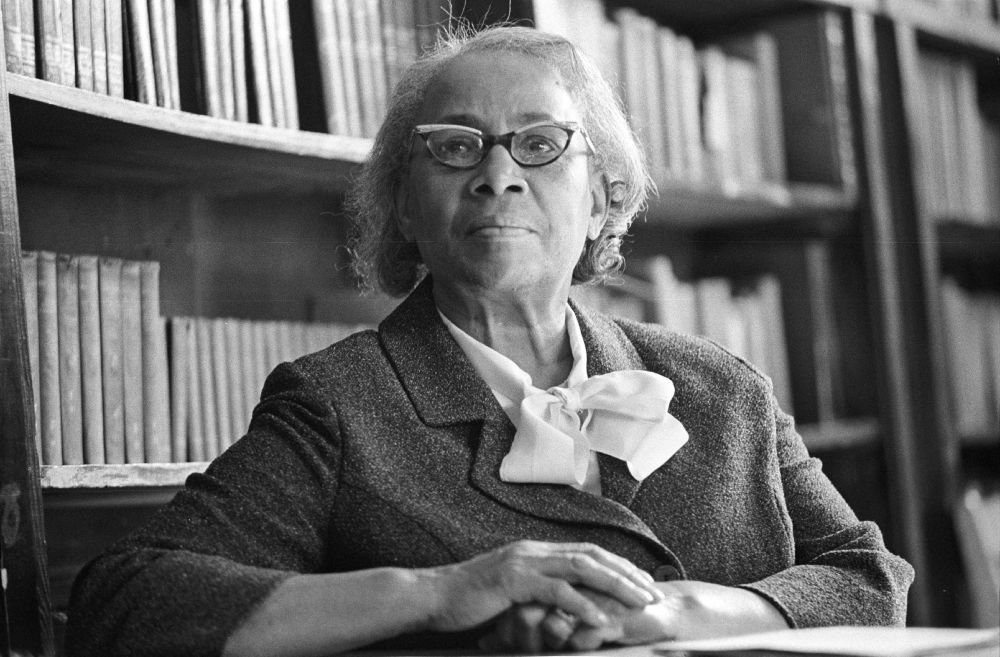

AA: I love that. That’s fantastic. And I’ll throw in here too, another teaser that you mentioned Inez Milholland, and we won’t have time to go into her story, but my listeners and my viewers on YouTube will know about Inez Milholland as the woman who was riding the white horse leading the women’s parade, the great women’s march for women’s suffrage. So you know who she is already and I learned so much about this woman and was so inspired by her. So again, just another plug to get the book and read all about her. She’s just fantastic. But maybe the last women that I’ll ask you about, Sharon, are Claudette Colvin and Septima Clark whom you feature in your book, and I’m so grateful. These are heroes of mine. I studied women in the civil rights movement during my master’s degree and wrote my master’s thesis on women in SNCC. And I knew about these women and again, was just thrilled to get to know them better and learn details I’d never heard before.

I’m going to read just this one little passage that you wrote in the chapter on Septima Clark. You quote her as saying, “You never know when a person’s going to leap forward or change around completely. I’ve seen growth like most people don’t think possible. I can even work with my enemies because I know from experience that they might have a change of heart any minute.” And that makes me emotional because I think of times that I have had a change of heart, that I’ve learned things and I’ve been so grateful for people’s patience with me when I make mistakes. And just that relentless faith in people that they could have a change of heart any minute. I just love that from Septima. And I know that’s one of the cornerstones of your work, Sharon. So could you talk about that a little bit, talk about Septima and about that quote, especially in the context of this moment in history, how relevant it is.

SM: It really is, isn’t it? I love Septima. She’s also a personal hero of mine. She was born in 1898 and had a set of life circumstances that nobody would ever wish to emulate. She gets married, she has a baby, her baby dies of a birth defect. She has another baby and discovers that her husband has a secret second life. He is married to somebody else, has kids with this other woman, and then shortly after discovering this, her husband dies, leaving her what? A single mom. And she becomes despondent. She contemplates suicide and is rescued sort of at the last moment from committing suicide. She goes on to become a teacher because her mom did not want her to become a domestic servant. Her mom knew firsthand how easy it was for “domestics,” as they were called, to be taken advantage of by their employers and that it made them very vulnerable. She wants her daughter to get an education. So Septima becomes a teacher at a time when she was not allowed to teach in Charleston public schools where she grew up. Even as a Black teacher, she was not allowed to teach in Black schools. They did not hire Black teachers in Charleston. And she moves to one of the South Carolina barrier islands, Johns Island, and she begins teaching at a school for Black children there and the conditions that she is teaching in are truly horrific. The amount of illness, contagious illness and malnutrition and issues that this community on Johns Island faced were formidable. And the school that she teaches in does not have any windows or glass in the windows. It only has shutters and it does not have electricity and the children do not have any books. The only choices were to keep the shutters closed to keep the bugs out – this is again, South Carolina, plenty of bugs – or to leave them open and get eaten alive by bugs. And again, bugs spread contagious illness.

So the children were literally learning in the dark with no books, and the sign on the front of the school said “Promised Land School” and it was anything but the Promised Land. It really was anything but. There’s no chance that Septima looked around her life, looked around at the school she was teaching, and she was often forced to send her own child to live with her dead husband’s parents because she did not have the financial resources or the physical resources to care for him, so he would periodically have to go stay with them. There’s no chance that she thought, “I’m really making such a societal difference here. I’m really overturning systemic racism. I’m really impacting the civil rights of African Americans working here at Promised Land School.” I can promise you that she did not think that. And yet, instead of throwing up her hands and feeling like nothing will ever change, which is that cynicism, that sense of nihilism or fatalism that so many Americans have today, she refused to engage in it. She refused to engage in this idea that nothing can ever change. And despite her external circumstances, despite the totality of her life, which includes being falsely arrested and accused of crimes she doesn’t commit, which includes people actively trying to kill her. They catch people on their way to firebomb her house, she has her life spared on multiple occasions. She’s fired from her job, she’s made a laughingstock of the community. Despite all of these circumstances, she never gives up hope that people and things can change. And in fact, she goes on to demonstrate that people and things can change.

When she’s fired from her job at Charleston Public Schools, that frees up her time to begin teaching adults and her freed up time allows her to teach somebody, an adult woman by the name of Rosa Parks. And in many ways, Septima is the mother of the civil rights movement. It was Septima who was empowering people like Rosa Parks to do the work that she went on to do. And of course, you know this having studied women in the civil rights movement, that Rosa was far more than just a lady on a bus, that she had a really significant impact on the civil rights movement beyond that day on a bus in December in Montgomery, Alabama. But Rosa would not be who she was had Septima not been there for her. Claudette Colvin would not be who she was without Rosa Parks. The web of interconnectedness of these women, I think, is an important takeaway here. We do not know all of the ways in which our work will impact people of the future. And it echoes back to what I was saying earlier. 100 years earlier, in the case of Rebecca Brown Mitchell, 50 years earlier, almost, in the case of Inez Milholland, no work for liberty is lost. And Septima goes on to say, as you quoted, that at the end of her life, she becomes a member of the Charleston school board. People ask her what she’s learned, and she says, “I have learned that I can work with my enemies. Because they might have a change of heart at any moment.”

And, dang it, if that is not a message that Americans need today. And I’ve mentioned this before, and so many people have told me like, “Oh, I’m just not there, I’m not ready to work with my enemies. I actually really hate my enemies, so why would I want to work with them? So… I’m gonna pass.” Listen, Septima had real enemies. She had people actually trying to kill her. She grew up in the Jim Crow South. She was not equal throughout most of her lifetime. She did not have equal rights. She was part of many lawsuits to gain more equal representation, more rights. Septima had real enemies, both personal and systemic, and her perspective was, “I can work with my enemies because they might have a change of heart at any moment.” And how are our enemies going to have a change of heart if we do not work with them? That is a very real question I would pose to Americans today. If your enemies only coexist with your other enemies, guess what? It’s going to be a self-perpetuating cycle. They’re just going to keep on being like, “Yeah, you are right, you’re totally right.” They’re only going to hear echoes of their own opinions reverberating back to them. How will our enemies see the light if we refuse to share it with them? Whoever you define your enemy as, and I’m not talking about like a warfare enemy, I’m talking about somebody with whom you have a strong ideological difference. How will they see the light if you don’t show them your candle? And that is just as relevant a message in 2024 and 2025 as it was in 1955, as it was in 1898, as it was in 1850, and for thousands of years before that.

AA: Hear, hear, I couldn’t agree more. And Sharon, I think that’s a perfect way to wrap up our conversation. I feel so heartened and so galvanized to keep doing the next needed thing and to remember that no effort in the right direction is wasted. We all inherit what we inherit and we have no control over that, but we do have control over what we do and how we choose to use our precious time on earth. And again, I cannot recommend highly enough this book, The Small and the Mighty. I know you’ll find it inspiring and galvanizing because it helps us identify what is the work that I have to do. All of these amazing examples, they did what they were supposed to do or what they were born to do. What can I do now? So Sharon, again, thank you. I’m such a big fan and this was just a beautiful conversation. Thank you so much for joining us today.

SM: It’s my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

she never gives up hope

that people and things can change

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!