“let’s figure out how to make this better for both of us”

Amy is joined by Jen Lumanlan to discuss her book, Parenting Beyond Power: How to Use Connection and Collaboration to Transform Your Family and the World, exploring the ways power-over parenting teaches patriarchy to the next generation, plus needs-based alternatives and practice scenarios to help listeners put these anti-patriarchal parenting approaches into use.

Our Guest

Jen Lumanlan

Jen Lumanlan, M.S., M.Ed., (she/her) obtained Bachelor’s degrees (Forestry, English) from the University of California, Berkeley and a Master’s in Environmental Management from Yale University and enjoyed a career in sustainability consulting before having her daughter, when she realized she was in for her toughest challenge yet. She went back to school for a Master’s in psychology focused on child development and another in education to understand how to raise her child, and launched a podcast, Your Parenting Mojo, to share what she was learning with others.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: As a mother, I have received lots of parenting advice over the years. Some of that advice was helpful and wanted, and plenty of it wasn’t. But nowhere in the books or articles or casual conversation did anyone ever mention how patriarchy affects our parenting. Long-time listeners will know that plenty of feminist scholars from Kate Millett to Anne-Marie Slaughter have written about patriarchy and motherhood as interconnected concepts, but when it comes to practical parenting tips, what we should and could actually do about patriarchy right now to prepare the next generation, the sad truth is that most of the literature that’s out there continues to reinforce patriarchal norms of hierarchy, of power over, of punishment. “Patriarchy says that one person must always be dominant,” writes parenting coach Jen Lumanlan. She says, “White people over everyone else, the male in a heterosexual partnership,” and she adds “the mother over the child.” You might be wondering with me then, how can we challenge these patriarchal parenting norms? Are we really ready to let go of our power over our children? And what alternatives are out there? I am very pleased to have a guest with us today who’s going to help us answer all of these questions and many more. She’s a researcher, writer, and celebrated parenting coach, the one I just quoted. Please join me in welcoming Jen Lumanlan, author of Parenting Beyond Power: How to Use Connection and Collaboration to Transform Your Family and the World. Welcome, Jen!

Jen Lumanlan: Thanks, it’s so great to be here with you.

AA: Jen Lumanlan, M.S., M.Ed., obtained bachelor’s degrees in forestry and English from the University of California, Berkeley, and a master’s in environmental management from Yale University, and enjoyed a career in sustainability consulting before having her daughter, when she realized she was in for her toughest challenge yet. She went back to school for a master’s in psychology focused on child development and another in education to understand how to raise her child. She launched a podcast, Your Parenting Mojo, to share what she was learning with others. Her work is guided by academic research in an attempt to help parents to create a world in which their child’s and their own needs are met alongside the needs of all children and all parents. She’s the author of Parenting Beyond Power, the book which we will be discussing today. Jen, I’m really, really excited to get into this. But first, I’m wondering if you could introduce yourself to listeners a little more personally. Tell us where you’re from and what brought you to do the work that you do.

JL: Yeah. I am from England originally, which accounts for a very strange accent, which I’m told is mostly American these days. I grew up with two parents and a sister, and I didn’t have the best parenting role models. So after I had my daughter, I kind of realized, “Well, I don’t know what I’m doing and I can’t really look to how I was raised to inform how I want to raise her. So what tools do I have?” And I realized that I am really good at looking at research. Coming from an academic background, it was something I was comfortable with. At the same time, as I was thinking through this, I was getting these emails from the typical websites that you sign up with when you’re expecting a child, and some of them were sending me emails like, you know, “Five ways to tell if your baby has a developmental delay,” and I’m like, “This is just clickbait, and if they ever do tell me something useful, it’s something useful about one study that was just released. And how am I supposed to know if this confirms the last 50 years of research on this topic or is completely in the other direction?” And so I was like, “I’m pretty sure I can do better than this.”

So I ended up going back to school and getting those additional degrees, basically to put a framework around what I was learning and say, “Is there more here that I’m missing?” And then I kind of thought, “Well, I might as well share what I’m learning with other people while I’m doing it.” So, we’re 200+ episodes in now, where usually I either interview an expert who’s sort of the go-to person in a specific field on a topic that parents care about, or I’m looking at a series of interrelated topics and I’m kind of talking through, okay, if we believe this and if we know this, what does that say about what we might want to do about this topic related to timeouts, related to rewards, related to whatever. Yeah, that’s the Your Parenting Mojo podcast in a nutshell.

AA: Love it. And I love that you’ve put this book out there, too, to reach, I assume, a whole new audience of parents who are wanting to do things differently from the way we were raised, but don’t know how, right? I’d love to dig into the book, because there’s so much to cover here. I wanted to start out by talking about the concept that parenting is political. You say this in the book, and that our most commonplace parenting methods are deeply steeped in white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism. I’d love to have you dig in on that and learn a bit more. How did these oppressive systems show up in our parenting? And then, of course, why do we need to be concerned about that?

JL: Right. And you sort of mentioned it already as you’re taking up that question. You’re talking about power. And at their core, these three systems of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism are all related to power. White supremacy says that white people should have more power over people of color and that that is the natural and correct way that the world should be run. Patriarchy says that masculine men should have more power over gay men, and all men should have more power over all women and trans women at the bottom of the heap in this patriarchal order of things. And capitalism says that people who have more money have more power than people who have less money. So these are kind of the three systems that are interrelated that say how it’s okay to show up in the world. And when the version of ourselves that we put out into the world is aligned with those systems, we are rewarded, and when the version of ourselves that we put out is not aligned with those systems, we are punished.

Just as an example, I had a call right before this call that ran longer than I thought it was going to, and I sent you a quick message and said, “Hey, are we recording with video on? Because I’m not really ready.” I thought I was going to have more time because I know that our patriarchal system rewards women for showing up in a certain way, and that if I’m looking more professional, more fluffed, right, if I’ve smoothed out my skin tone, then people look at me in a certain way that is different from the very casual clothes that I was wearing half an hour ago. So I am rewarded for the fluffing that I did. I would have been “punished” for not fluffing adequately by people potentially thinking, “Oh yeah, she probably doesn’t know what she’s talking about. What is she wearing? Why is her hair so weird?” Maybe some people are already thinking that, but there would have been more of it. So that’s how the systems of rewards and punishments work in our broader society.

Our parents, whether they realized it or not, looked out into the world and they saw these systems happening. And because they loved us, because they wanted the best for us, they wanted us to succeed in the world, they used their power over us, firstly, to get us to do what they wanted us to do because they had deep needs for ease, right? “I just want this parenting thing to be easier,” which many of us carry today. And also because they were preparing us to be successful out in this world. So, we might think abstractly, “Yes, I want to do things differently from the way I was raised because I see how much pain and hurt I’m carrying around.” But unless I know what to do differently, particularly in times of stress when we fall back on all of the power over tools that we were raised with, we’re not going to actually be able to achieve our goal of doing something differently. We will raise our children using the same tools that we were raised with unless we make a conscious decision to do it differently and when we have some tools to be able to do it differently. So that’s what the book and my work in general aims to provide.

AA: I wish that I had had this book when my kids were little. My kids are older now, they’re 23 down to 16. And I feel really good about the way I raised them. I read lots of parenting books, I knew I definitely wanted to do some things similarly and some things differently. But, oh, I think back to some of the strategies that I had even learned in the books that were coming out at the time, and I just think, “Oh my gosh, I just wish I’d had better tools.” And you’re right, in those moments of stress of a tantrum, I mean, it’s just really, really hard to access, even stuff that we’ve learned, if we haven’t practiced it enough, we just revert to what we know, or just what can make the tantrum stop. It’s really hard. My next question is, you point out that most conventional parenting advice tells us that it is the parent’s job to be in charge and obtain their child’s compliance. It insists that the parent’s way is the right way because young children aren’t equipped to handle the world, they don’t have understanding, and they just don’t know how to do it. So the parent does need to be the one who exerts that power. How would you respond to that?

JL: Yeah. If we think back to our own childhood, chances are most of us can remember a time when we knew what we needed. We knew how we wanted our parent to respond to us. We knew that we had a need to be seen and heard and understood and known as who we really were and to belong in a family without having to change ourselves, without having to put this polished version of ourselves out there to just be accepted by who we truly were. And our parents either didn’t see that or couldn’t see that. So what we’re talking about when we’re talking about, you know, “Shouldn’t I be the one who’s in control here?” There’s this idea floating around at the moment about being a sturdy parent, which is kind of another way of saying that I’m the one who knows better than you do. What we’re actually saying when we’re saying that is “I know your needs better than you do.” And that has really important implications for the kind of children we’re raising.

I think back to the epigraph that I used in the book which links back to the idea we’ve already talked about, about how these systems are out there in the world. The epigraph is: what if I told you that your ideas about politics are actually just your ideas about childhood extrapolated? And that’s from a political scientist named Dr. Toby Rollo up in Canada. So when we’re saying, “I am the parent, I should be in charge,” what we’re saying is, “I support all of those other power over systems, because that is what I am training my child to do. When I am the sturdy parent and I am in charge, I am training my child that a person who is bigger, who is older, who earns the money, who has all of the tools available to be able to get somebody else to do something, that that person should– it is their job to get the other person to comply.” I actually did an interview with a listener a while ago who is Iranian. She was born in Iran and grew up a little bit in Iran and then moved to the U.S., and she said, “Every time I think about all the reasons why people say, ‘I should be the one in charge,’ I think back to all the reasons why men in Iran say ‘I should have control over women.’ And I can’t think of a reason yet why I should be able to control my child that isn’t a reason that men in Iran use to control women.” And she said, “I can’t think of myself as a feminist, I can’t call myself a feminist and also believe that I have the right to control what my child does.”

AA: Okay, well, I know listeners are probably with me and really wanting to embrace those ideas, but are thinking of a hundred examples like, “But what about this? But what about this?” And we’re going to get into all of those.

JL: Yes, we are.

AA: Yeah, don’t worry. We’ll get to that. We’ll get to the nitty gritty of it. Okay, so tell us about, first of all, the problem solving approach. What is it and why might it be more effective than our usual parenting practice?

JL: Yeah, essentially what we’re doing is instead of saying “the thing that I want you to do is the most important thing and that’s the only way that we can proceed is I’m going to win when you change your behavior, and you’re going to lose because you’ve changed your behavior, you didn’t get to say how I changed my behavior.” Instead of doing that, we’re saying, “What are the actual needs that we have here?” And we’re going to talk a lot more about what needs are. “What are the needs of each person in this interaction, and can we see each person’s needs as equally valid?” When we’re doing this we’re differentiating needs from strategies, and this is such an important point because it’s so easy to get caught up in this in the English language because the English language allows us, and probably other languages allow us to say, “I need you to unload the dishwasher.” That’s not a need, right? If I’m saying to my husband, “I need you to unload the dishwasher,” what I’m actually saying is “I have needs for collaboration and teamwork and for support and I’m asking you to unload the dishwasher if that can also meet needs that you have so that we can get both of our needs met.”

When we start thinking about strategies, which is the way we’ve decided, you know, “This is the thing I want to get my kid to do,” when we instead think about our needs, we uncover multiple strategies to meet both of our needs and the vast majority of the time we can find a strategy that meets both of our needs. And when we meet both of our needs, we’re not in this power over relationship anymore. We’re also not being permissive. We’re not saying,

“Yes, whatever you want. Yes, you can have it.” Because if we do that, my need is not being met, and then I’m a permissive parent. And I think a lot of people are scared, right? If I’m meeting your need, that means I’m permissive. What stops this from being permissive is that I know what my needs are and we are going to meet my needs and meet your needs as well. A lot of the parents I work with tell me “I didn’t even know what needs were until we started working together.” And if we don’t know what our needs are, we get stuck on these dueling strategies. Understanding needs is the critical piece of problem solving and it allows us to find strategies that meet both of our needs.

when we’re saying, “I am the parent, I should be in charge,” what we’re saying is, “I support all of those other power over systems…”

AA: I love that. Well, let’s get into it then. I’d love you to walk us through a real life scenario, maybe with a younger child. Let’s say it’s bedtime and we’ve tucked in the child and read a story and done the whole routine, and then we go to turn out the light and the child just says, “I’m not tired,” tosses off the covers and is hopping out of bed. What would be the power over response to this that comes kind of from that model of patriarchal, you know, “I’m at the top, I will force compliance.” What would be that? And then how would we navigate that interaction using a problem solving approach from your model instead?

JL: Yeah. So, I am imagining that parents listening to this can maybe see how they’ve handled it in the past, right? Maybe we’ve done things like tell them to stay in bed, “It’s my time now and you have to stay in bed. There’s no other option here.” We may have offered a reward. “If you stay in bed, you can have X.” We may have threatened a punishment. “If you don’t stay in bed, then this thing that you really want to have or want to have happen is not going to happen.” Rewards and punishments are all a part of that power over approach. When we’re using a reward and a punishment, which is, I mean, they’re essentially two sides of the same coin, what we’re saying is “I am the judge of what is appropriate here, and when your behavior matches my expectations, you can have the reward. If it doesn’t match my expectations, I’m going to punish you until you change your behavior because I’m the person in charge and I get to say.”

So what we’re saying is, okay, let’s not do any of those things, but it’s not a free-for-all at our house and you get to do anything that you want to do. What we’re wanting to understand is why doesn’t the child want to stay in bed? So your question gives us a head-start on that. Maybe the child isn’t tired. Maybe there’s also something else at play. Maybe they’re afraid of something. I hear from a lot of parents, “My kid says they’re afraid, and actually I don’t think they really are afraid, they just know that if they say they’re afraid, then I’ll come back to the room.” Maybe they need connection with you. And I hear this over and over again. Parents are like, “Why does my kid drag out bedtime? They have to say goodnight to every flipping toy in the room. Why does this take so long? They’re stalling every step of the way.” When we see that happening, it’s almost always because the child is looking for more connection with the parent and something as simple as 10 minutes of daily protected one-on-one special time – we call it “special time” so that it’s not just, you know, we’re hanging out together, we’re going to fold the laundry, we’re going to do what you want to do for 10 minutes – that can completely shift the tone of bedtime.

The child is no longer trying to wring every single moment of connection out of bedtime. They prefer if you weren’t stressed out and yelling at them to stay in bed, but they’ll take it over going to go calmly to bed and the whole thing’s over in five minutes, and then I have to lie there by myself. I’d rather be with you for an hour, even if you’re yelling at me. So when we understand what the child’s need is, then we start to find strategies to meet the need. If it’s connection, we try to find some time for connection earlier in the day. We’re also looking at what our needs are. Is my need for self care and the reason I’m having a hard time with this is because it seems to me as though every moment that you’re resisting bedtime is a moment that is stolen from my self care time? Then we start to look at, well, are there ways that I can get self care earlier in the day so that I’m not relying on this period of time after bedtime to get all of my self care and then I don’t have to be so tight about bedtime? I might be able to find more capacity to come towards you because my need for self care has been met. Those are the kinds of strategies we start looking at in that kind of situation.

AA: This is really helpful. I’m thinking of so many scenarios, and maybe we’ll talk about this a little bit later in the episode, too, but I’m just thinking back to moments in my parenting where I haven’t parented the way I wanted to. And when I dig just a little bit under it, it is that my own needs weren’t being met. Either I was just exhausted at the end of the day, like in this bedtime scenario, or I remember specifically there was one time I went for a run with my daughter and we had agreed on an amount of time that we were going to run and she just kept stopping and saying, “Oh, I don’t want to do it.” I even noticed it at the time, like, “Whoa, this is a disproportionate reaction to this.” And I think a lot of it had to do with my expectations, but right underneath was my fear. My fear that I hadn’t taught her to push through discomfort, that I hadn’t taught her to be a hard worker. I had a lot of fears that I needed to just address in myself. She was probably truly just tired that day and it wasn’t about her, actually. And I was acting like it was about her and that this was important that she needed to do. It was all about me and my fears. And I think that happens so often in parenting that when we get a little space and distance, we look back and we’re like, “Oh no,” we took out our own unresolved insecurities and worries and wielded that as a weapon. It’s just so unfortunate and not fair to the kid.

JL: Oh yeah. I teach a whole 10-week workshop called “Taming Your Triggers” for that exact reason. Because so many of these particularly control-based examples, like you’re giving, in the framework that I use, a lot of people will say, “We have a need for control.” I don’t believe that we have a need for control. I believe that when we think we have a need for control, underneath that is always a fear. The fear of something, just like you described, “I’m not preparing you well enough. My need for competence is as a parent is not being met. I don’t feel like a competent parent when you are saying that you don’t have the resilience to push through any challenge.” So then we start looking at “Can I reframe this and perceive myself as a competent parent because I can see you knowing what is enough for you,” right? In all the ways that we as women struggle to say, “No, that’s too much for me. I can’t take that on right now.” You know this already, small child! Haha. I can look to you and learn from you on that. If I can get out of this mindset of “You’re not resilient enough, you’re not going to be able to fit into white supremacist-patriarchal-capitalist world. You’re not going to earn enough money, you’re not going to be able to buy the house you want because I haven’t taught you to be resilient enough. You’re not going to be able to get a job,” all these things, and I help myself heal from the hurts that I experienced and the ways my parents couldn’t show up for me because of all their own unresolved trauma, so that I can now show up for you in a way that honors and sees you for who you truly are, and also honors and sees me for who I truly am as well.

AA: Yeah. I love that. Okay, I’m going to throw another scenario at you. You can walk me through exactly what you would do. Let’s say the other example was kind of in the privacy of your home, you’re tucking your child in, they don’t want to go to bed. One thing also that can get really tricky for parents is if they’re in public, I think, because then there’s the embarrassment. It’s not only that I’m worried I’m not a good parent, it’s like, “Oh no, other people will see that I’m not a good parent.” And then when you’re on a schedule, that’s another trigger. Let’s say we’re dropping our child off at school and they decide, “I am not going into school today.” And we try all the like, “Oh, it’s okay. You’re going to have a great day” and try to coach them or whatever. And then it’s a tantrum and we’ve tried for a little while to be positive and helpful, and then there’s a line of cars behind us and we’re running late for work and people are starting to look because our child’s kicking and screaming. Can the problem solving approach still apply? Or, this is a rhetorical question, is it time to just revert back to the power authoritative parent? What do we do?

JL: We use our power over the child. No, we don’t. I want to sort of draw out something that you said early on in that question. “Other people will see that I’m not a good parent,” and I see that over and over again. This is such a trigger for so many parents. This could be parenting in public, could be parenting in front of our own parents, in front of the in-laws, at the playground, right? “I need to have my need for competence met.” When that is not met, when that is threatened by perceived judgment from somebody else, which frankly, we never know if it’s real, right? The teacher who’s in the pickup line might be thinking, “Oh my goodness, look at that parent. They are doing the absolute best they can on a struggling morning.” They may be having so much compassion for us. And what we perceive is “You’re a crappy parent. You should be able to get your kid out of the car. How many times have we done this already, it’s already November. You should have this under control by now.” When we perceive that judgment, it constrains the potential strategies that we are able to consider.

What we want to be doing in this situation, ideally, is when there is a difficult situation with our child, we don’t want to address it in that moment. If our child is refusing school, I mean, it almost never comes out of nowhere, right? It almost never begins as a massive tantrum in the drop-off line of, “I’m not going to school today.” It ramps up over a period of time. So what we want to be doing is seeing this happen way before it gets to the tantrum in the drop-off line phase so we can address it outside of that moment. At that moment, we’re basically trying to get through it with as much grace as we possibly can. And that will probably involve some variation of, “I know this really sucks and I don’t know all the reasons why you’re not wanting to get out of the car right now. I’m seeing the long line of cars behind me and I’m feeling really stressed out and I was due at work 10 minutes ago. I really want to hear your side of this and why this is so hard and I don’t have the capacity to do that right now. Would you be willing to get out of the car and just know that tonight we’re going to have a conversation about this where we can truly try and see why this is so hard for you and how we can meet both of our needs. Would that be okay with you?” So we’re still not using our power over, right?

That phrase, “would you be willing to?” is like gold dust when we use it with our kids. Oh my God, the first time you hear your child saying back to you, “would you be willing to do X for me?” It’s like, “Aww!” Because that phrase allows me to consider, “Do I have the capacity for that right now? Will doing this detract from my ability to meet any of my needs? No, it doesn’t. And it helps me meet my needs for collaboration with you. Yes, I’m willing to do it.” Or, “Actually no, I don’t see how I can meet my need for nourishment and food right now if I’m going to read you a story at the moment, so I’m not willing to do it at the moment. I am willing to read to you after lunch.” So, “Would you be willing to get out of the car right now and go to school? I’m so sorry if this is not the easiest day for you and I want to talk about this with you tonight.” Ideally, we’re going to have had that conversation last night, but assuming that ship sailed, right? That’s what we’re going to say in the car and we’re going to hope that our child is willing to get out of the car.

And if they’re not, do we have any ability to make this a sick day? Can we leave them with a neighbor or a friend this one time, knowing that tonight we’re going to address this? And then what do we do tonight, “Tell me how you’re feeling about school. What’s coming up for you when we’re going to school? Why is this hard?” And then we’re listening for the needs underneath. Is there a struggle with a teacher? Is there a struggle with the schoolwork? Is there a struggle with peers? Are they feeling disconnected from us for being apart from us for so long? Is it because they have high sensory needs and the pushing and shoving that happens on the playground is too hard for them to cope with and they get dysregulated? Until we know that, any attempt to get them to go to school is using power over.

Okay, I also have needs to be at work, I have the need to meet responsibility for my coworkers, for competence in my work, for responsibility. So how can we meet your need and also meet my need? Then the strategies we consider are going to be different based on the child’s needs, because if they are having sensory issues in the playground, having a conversation about what happens in the classroom is not going to help. When we understand the need, “Okay, you want to not have people touching your body. How can we make that happen? Let’s work with the teachers with all the different places that people touch your body that don’t feel good to you. And let’s put plans in place that we can navigate that.” Or “You’re struggling with the schoolwork, let’s figure out how we can better support you in that.” Understanding needs opens up the strategies so that we’re no longer, “You have to do this and I don’t care why you’re saying you don’t want to. Let’s go to school.” Let’s get to the bottom of this together. And there’s such a powerful difference between “you’re going to do it because I say so” and “let’s figure out how to make this better for both of us.”

AA: Yeah, it is. It’s a long-term solution and you win your child’s trust also. I remember this moment when my oldest daughter– Well, all of my kids have pretty much always loved school. My oldest daughter loved school pretty much every day of her life from preschool until eighth grade. And I remember that one day she was sobbing at the house, and I just said, “We’ve got to go,” and I was trying to figure out how to teach her tools to deal with the anxiety she was feeling. I was trying to get to the bottom of it, but it just was so clear to me as we drove up to the front of the school and I said, “It’s time to get out” and she was bawling. And if I had relied on power, if I had relied on force like when she was four, like picking her up, peeling her off of my body and handing her over to the teacher, at some point that stops working. At some point you both realize that you cannot force your child to do anything they don’t want to do. So even if you win those battles when they’re little, it just won’t even work long-term, and I was very aware of that. If she refuses, I can’t make her, I wouldn’t even want to, but I just was very aware that she was old enough. And she got out of the car and went in. But it was this realization that she’s old enough and big enough now, she’s going to do what she’s going to do at this point.

JL: Yeah. And to put a finer point on what you’re saying, I wish I could attribute this quote and I will try and find it so I can send it to you. It’s along the lines of– Oh, actually, I remember where it’s from. It’s from Parent Effectiveness Training.

AA: Oh, yeah. I love that system. Yes.

JL: I’m forgetting the author right now, but yes, Parent Effectiveness Training. The author [Thomas Gordon] talks about how when your kids are older, you lose the ability to have power over them because they’re bigger and you can’t force them anymore. What you have at that point is influence. And if you use power over your kids when they’re young, you lose the ability to influence them because they don’t want to be influenced by someone who has used power over them. So if you want that influence when they’re older to be able to have them come to you when things are hard, when another kid is trying to get them to steal or the first time a kid says to them, “If you love me, you’ll perform the sex act on me,” do we want them to be able to come to us and say, “I was in this situation, it was really hard, and I need help”? If we have used power over them, they’re not going to come to us with that stuff. If we have demonstrated through our actions for years and years and years that when we have hard stuff together, we’re going to figure out a way to get through this and meet both of our needs, they will come to us with that and then we are able to influence them. And that’s what we want, right? That’s what we’re going for when our kids are getting older.

AA: Yeah, for sure. That definitely checks out. That tracks over the course of my life, how I was parented as a kid, unfortunately. And then I was grateful I did read Parent Effectiveness Training early enough in my parenting that it was a paradigm shift for me and really, really helpful. Okay, one thing that strikes me too is that this is a lot of work, Jen. It’s just faster and more efficient and easier to have an authoritative approach. And having a negotiation where we are negotiating, “I have needs, you have needs, let’s discuss, let’s figure out what’s underneath this,” it’s exhausting. And I do believe it’s worth it, and you’re on the podcast, you believe it’s worth it. You’ve published books about it, you’re doing this work. But how would you encourage parents to gear up for what is required in doing this work?

JL: Yeah, I guess I would push back a little bit on the characterization of it being exhausting. I fully, 100% agree that it takes more effort the first time around. It takes more effort to learn a new tool, to practice the tool that you’re not familiar with, to try to understand what your child’s feelings are. What are my feelings? It takes some effort to understand what my needs are in a situation. Not just what am I trying to get you to do, but what are my actual needs? What are your actual needs? It does take more effort to be able to do that, but when we do that, what we do is we create sustainable strategies that meet both of our needs and then our kid stops resisting us. So if you’re having the same arguments with your child over and over again, every single day, if they’re resisting getting into bed every day, staying in bed, resisting brushing teeth, resisting putting shoes on to get out of the house. Or with an older kid, resisting homework, resisting getting out of the car in the morning to go to school, all of the things our kids resist. Could you imagine not having that fight every day? Because when you understand each other’s needs and you find a strategy that meets both your needs, you’re not having that fight every day, so that’s where it gets easier. So, yes, it’s a little more time and energy intensive up front, and then the amount of time and energy it saves you on the back end is almost immeasurable. And in addition, it meets your needs for competence, for ease, for calm, for peace in your home, because you’re not having these fights all the time with your kid over every single little thing.

AA: I believe you, and I’ll definitely say it’s worth it. As someone with four kids, I will also say that some kids are just kind of more suited for all the stuff that’s required of them and a short conversation like “let’s get to the needs” is a little easier than with other kids. And I do have one child who, just everything, I mean, even the most normal things, this child wants to negotiate and get into long conversations with every single thing. I do believe it’s worth it because it’s a better long-term practice and it saves the relationship, which as you said, then you know that the child is going to come to you. But the truth is, I mean, if that’s the nature of the child, forgive me for just thinking out loud here, but if that’s the nature of the child, what are your options? Like you said, you go to power at some point and that blows up in your face. If not on that day, it does at some point. Or you just say, “Yeah, this is going to be a little bit more time consuming than if I had a pretty easy-going kid that didn’t chafe against all of the constraints of society, including brushing teeth, including being on time to school every blasted day. Yeah, that’s just the nature of the human being that you have in your care that you love so much.” Those are the options, right? Either power or love and listening and negotiation. So I guess that’s the thing. It’s not an option like the power is going to make it better anyway.

Not just what am I trying to get you to do, but what are my actual needs?

JL: Yeah, and I guess what I would say to that, you know, I’m not trying to diagnose your kid and I think there’s a danger in jumping right to pathological demand avoidance, which is a very, very high need for autonomy when sometimes it just means that we’re putting so many demands on the child that they are pushing back against everything, any request that we’re trying to make. What we can do in that situation is say, okay, I see that autonomy is a really, really big need for you that you want to have a say in this decision. And in the book I put this framework as a cupcake of needs. The cupcake model is the idea that we are usually trying to meet similar needs over and over again. For parents, it’s very often peace, ease, harmony, patience, and we call that the cherry need. That’s going to be the thing that comes up most often over and over again. And then underneath that is the frosting, which is the next three to five needs that come up over and over again. Underneath that is the other 40 needs.

If it’s not one of those things, the cherry or the frosting, it’s going to be something else in the cupcake. So what I’m hearing is for this child, autonomy is one of the cherry needs, if not the cherry need. And what we’re working with with that child is, okay, there’s a request. What would it take for me to say yes to this? What are my concerns? What are my fears? What do I want to control, and what are the fears underneath that? What am I worried is going to happen? What plan can we put in place to make sure that thing I’m worried about doesn’t happen? That’s what we’re saying about avoiding being a permissive parent, because when I can say what I’m worried about and we put a plan in place so that that doesn’t happen, then my need for competence and ease as a parent are met and then also you get your need for autonomy met as well. That’s how I would approach it. “What would it take for me to say yes to this?” is the question where you have a child who has such a pervasive desire for autonomy.

AA: Wow, that’s great. Well, thanks for indulging my little problem-solving, trouble-shooting in my personal life. Okay. Zooming out to the bigger picture, I’m wondering how these problem solving approaches actually help our communities to dismantle and heal from the oppressive structures like patriarchy and white supremacy. Can you talk about how these efforts to change our homes might affect the larger cultural constructs?

JL: Yeah, so if we think back to where we started this conversation and the idea that white supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism are all power over systems, which we perpetuate by using power in our homes to get our kids to do what we want them to do, not because we are saying, “Yes, I want to perpetuate this system because I love them so much” but because it seems like it’s the only way to get things done, right? When we reject that paradigm and say, “Instead, I am going to try to the best of my ability, knowing this is a new skill and I will fail because I’m human and humans fail and then we will get up again and we will do it again.” We will repair, we will keep moving forward and building our collaboration when we are going to see each other’s needs as equally valid. I’m not just going to roll over and say “Yes, darling, whatever you want goes,” especially my high autonomy kids, right? “Yes, you get to do whatever you want.” No. It is, “As long as my needs are met,” which is, “I have a need for your safety, I have a need for competence in parenting, which I can meet in a whole bunch of other ways.” It doesn’t have to be saying no to the thing that you’re asking for. When my needs are met and your needs are met, we share power in this relationship and then we raise children who know how to share power, who are adept at finding strategies that meet both of our needs. And, goodness, it doesn’t take super long to practice this with a child before they start bringing you strategies that meet your needs. Before they stop resisting every single thing that you say, because their need for autonomy is just being met, because you’re not putting as many limits on their behavior.

So you’re practicing this, your parenting gets easier, your kids take this out into the world, they take this to school, they take this into problem-solving with their friends, they start to be able to see, “Okay, why do you want to do this? What’s your actual need? Okay, here’s my need. How about we try it this way, because then we can meet both of our needs?” They do it with their friends. They go out into the wider world, perceiving that it doesn’t matter what color my skin is, what color your skin is, each of our needs are equally valid. It doesn’t matter what genitals you have, what gender presentation you have, your needs are just as valid, not more, not less than mine. And then capitalism, I don’t have all the answers on that one, but I hope we can at some point somehow get to a system that doesn’t rely on us using money to be able to say “Because I have money, my needs are better and more important than yours.” The path on that one is a little less clear, but I don’t believe that we can exist in a world that has these systems that run it when we see each other’s needs is equally valid. The two cannot coexist. And so the best way I see of creating a world where everybody truly gets to belong, gets to express their whole selves, be accepted for who they really are, to thrive as a whole human being, is to raise our children using these tools because then they go out into the world and they create that too. And then we move away from all of these power over systems. That’s where I hope we go.

AA: Yeah, for sure. I mean, it’s actual grassroots change, right? Like grass growing from the bottom up. And like you’re saying, bringing that sensibility to their marriages, bringing that sensibility to their religious leadership, to their political leadership. Thinking of capitalism, I guess some low-hanging fruit would be making meaningful campaign finance reform and the ability of billionaires, for example, to pay people–

JL: We should be having this conversation on election day.

AA: I know! We’re recording this on November 4th of 2024 and that’s top of mind. But it’s true that if these adults had been raised in this way to really, truly have an egalitarian view of the world, it would be morally repugnant to allow people to buy votes, to buy influence in our political system, because it’s just unethical and everyone would know that. So, yes, hear, hear. And you have to start when they’re little. I was thinking about another example, kind of like the devil’s advocate of a listener who wants to be on board but is a little bit skeptical and might say, “What about when safety is involved?” And maybe you could do a two-part answer to this. A toddler that’s going to run into a busy street, that’s your first one. And then how about for a second one, a teen who you know is getting involved in risky behaviors, maybe drinking and drug use and they’re quite private about their lives and you’re trying to problem-solve and you know that they’re doing this. It’s illegal and potentially a very dangerous thing. So, first a toddler, then a 17 year-old. What would you do?

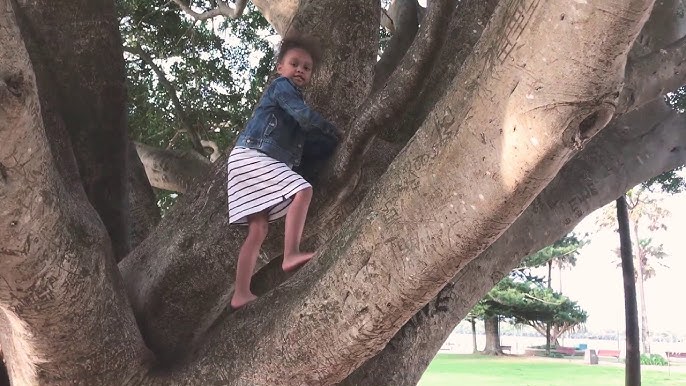

JL: Sure. I know that there are some people who work in this space who are pretty far out there and will say that we don’t have any responsibility whatsoever to use our power over our children. And I don’t go that far. I think that if there’s truly a safety concern that we do have a responsibility to use our power benevolently, and I think that the vast majority of the time we can avoid those kinds of situations. So I’m thinking in the example, let’s leave the street for a moment and let’s go with something climbing up a tree. Parents will often shout, “Be careful!” which doesn’t actually tell the child anything about the risk or what we’re worried about. A phrase you can use there is, “I’m worried that X is going to happen. I’m worried that you might fall. I’m worried that you’re not going to be able to get down again. What’s your plan?” So we’re involving the child, we’re not making this “This is my decision, I’ve decided you can’t climb the tree.” It’s, “Here’s what I’m worried about. I’m worried about your safety. How can we make sure that my need to keep you safe is met, while also meeting your need for joy, for play, for movement, for excitement, for challenge?” Those are probably all the reasons the child’s climbing the tree. Maybe we can have them climb up to where they are now, and then they climb down to show us they can do it. And then we think, “Okay, I’m actually more comfortable with that now. I can see how they’re competent. They are climbing down. I know that they can climb a little bit higher and they will still be able to get down.” Maybe we might not be able to see a way that we can make it safe enough and then we might say, “I’m so sorry, I’m just not comfortable with that. I don’t see a way that we can make it safe enough that this is comfortable for me, so I don’t want you to climb the tree.”

And what we’re doing here is we are privileging and prioritizing our need for safety over their need for all the other things that we just talked about. And if we truly cannot find a way to meet both of our needs, then our first tool should be to set a boundary. “I’m not willing to do X.” This isn’t a boundary-setting situation because we’re trying to change the child’s behavior, so, “I’m not willing to allow you to do X. I’m not willing to allow you to climb a tree.” We’re setting a limit. And ideally what we then want to do is to say, “Okay, can we come back to that?” And in a week, could I be more comfortable with it? What would have to be true for me to be able to say yes to this? Just like we talked about with the autonomy piece. Could you climb in safer places? Could we go to the climbing gym? You can get some more practice at climbing and then I’ll feel more comfortable with you climbing the tree and I can say yes to that. How could I say yes to this?

Taking it to the street example, very often I think we just see, “Oh, my kid’s running into the street. That’s not safe.” And it’s actually funny, this conversation is coming up twice in my conversation with you. In the same interview with the listener from Iran that we already talked about, she gave another example where her husband and her au pair had taken two kids to get their vaccinations, a five year-old and a three year-old. And they basically had to hold the kids down to give them the vaccinations. So, you know, no argument if you decide to give your kid vaccinations, that is your right, that is your decision. It’s the holding down part that is tricky. Ideally, we want to be working on making sure we have the child’s consent. Maybe the nurse can come back. We can give you tools to regulate, to distract, all those kinds of things. That didn’t happen in this case. And then they left the appointment and the five year-old ran out into the street. And it seems like a safety issue, right? “No, no, you can’t run out into the street.” They get home, the five year-old is telling mom about this and she asks, “Why did you do that? That’s not like you, you don’t normally run off.” The five year old said, “I wanted to punish daddy.”

AA: Oh gosh. Wow.

JL: “I didn’t feel safe when the vaccination was forced on me and I wanted daddy to feel how I felt when I was given that vaccination.” So my hypothesis is that perhaps more times than we might think, this is not just a “safety” issue. This is our child trying to communicate something to us in the best way that they know how. And we’re so lucky that that five year-old was so verbal they were able to share that with us. That gives us that insight into what is my child trying to tell me through this run-in-the-street behavior? So, yes, we should make sure that our children are safe and also we should be trying to understand what need is behind that behavior. What need are they trying to meet by doing that, and how can I meet that need? So they don’t perceive that the best way they have to communicate that need to us is to run out into the street. So that’s the toddler. Let me just pause there and see if anything comes up for you on that.

AA: Well, the thing that came up for me was teenagers, me being a teenager, and I can remember multiple people saying the words, like uttering the words, “F you, Dad,” as they tried drugs for the first time. So it actually bridges perfectly to part two. I was just thinking that there’s something in there oftentimes, maybe not every time, it can be about a variety of different needs. But that’s very interesting for that little child to perceive that “I wanted to punish dad because he made me feel unsafe” and just the rebellion. Oh, that’s powerful. I’m glad you shared that. Okay, let’s jump to that teenager then, because I think it’s similar. I do. I think it’s similar.

JL: Yes, and as a bridge to get there, it’s not just your son that has a high need for autonomy. We all have a need for autonomy. We all want to make decisions that feel important in our lives. It’s just that some kids are more vocal about it. Some kids are more willing to, and girls are particularly socialized this way, “Your needs don’t matter. Stop articulating your needs. You are too big, too loud, too much, just stop it. And when you stop articulating your needs, I will reward you with love and belonging and acceptance because now you’re a good girl and good girls are rewarded out in the world.” This is what we’re training our children to do when we are telling them, “No, we are not going to meet your need for autonomy. You do not get to be part of this decision making.” This is why we then have women show up and say, “I’m a people pleaser. I’m a recovering people pleaser. I don’t know how to say no to people.” And the unspoken part is “because I was never allowed to say no, because my need for autonomy was never met.”

So when we have this teenager who’s, you know, “F you, Dad,” what we see underneath that is years and years and years of unmet needs for autonomy, for connection and collaboration, for being seen and known and understood for who we truly are as a person. And our teen is turning to these teens who are doing drugs, is turning to the drugs themselves, as a way of saying, “I know you don’t want me to do this, and this is why I’m doing it, to punish you, to hurt you in the way that you have hurt me.” A lot has happened already by the time we’re getting to the point where our child is doing drugs. And let’s just say, that ship has sailed, we cannot change anything about that now, what do we do in this moment? In this moment, we can say something along the lines of– and as the sidebar, how tempting is it to say, “You’re grounded, you’re never going out again, you’re never seeing those friends again,” all the power over methods that we could default to.

Instead to say, “Oh my gosh, I’m thinking about all the reasons why you might’ve tried drugs for the first time last night, and I am thinking about my part in that, and all the times that I have not listened to you. I have not heard your perspective on things that must have been really important to you. I have made you do things you didn’t want to do and I prohibited you from doing things you did want to do. And at the time, I didn’t know any better. I didn’t know what my needs were. I didn’t know that I had a need for competence in parenting and I thought the only way I could meet that need was to say no to you. And now I’m learning that there is a different way and that I can be a competent parent and also have you meet your needs for autonomy and to be able to make decisions that are important to you. So I’m not going to punish you for doing drugs. What I want to do is to listen. And I know that in the past I’ve said that before, and what it has ended with is me trying to get my way and trying to steamroll you, steamroll over you into doing something that will meet my need. And I may do that again by accident because it’s just the tool that I was raised with and it’s what my body knows how to do. And when you see me doing that, I want you to tell me, I want you to use a safe word that we’re going to come up with together so that I can pause and see what’s going on for me and how can I meet that need that doesn’t involve you being prohibited from doing something. And moving forward, I want to try to understand what your needs are and what my needs are and find ways to meet both of our needs.”

And as these words are coming out of my mouth in this fictitious example, right, I didn’t go through that rebellious phase. I very easily could have, I mean, I guess I did a little later. I married an undesirable person, as it were, but I didn’t go through it in my teenage years. It came out a little later. And if either of my parents had had the capacity, the knowledge, the ability to say those words to me, would it have made a difference? Yes, it would, it would have made a profound difference. And you’re nodding, and I’m guessing it would have for you too.

AA: Oh, yeah. Huge. It would have been transformative. Yeah, and, I mean, generally the way I see the world is that parents are doing their best, and they’re doing the best with the tools that they inherited. And if they weren’t given better tools, then we can’t really blame them for that, and all we can do is do better, right? We inherit what we inherit, and then we try to make that change. One thing that we talk about on the podcast and have talked about a lot more recently is how patriarchy specifically creates an environment where men aren’t able to gain some of those tools of processing their own emotions, processing their own needs and they also are kind of rewarded for that. Maybe not even kind of, they are rewarded for those power over tools. So patriarchy, especially in really overt patriarchal systems like conservative religious patriarchies, where men really do have very obvious, explicit power over women, these boys can grow into men that really do believe they know better for everybody else. They can exercise that power benevolently most of the time, but if they lose their temper, it’s just because they love the person and they needed to correct them and that was their right. It enables this really bad behavior throughout the course of a man’s life and then those men are the ones who are creating all the systems so then women end up enacting those same systems even though they were harmed by them. It’s just such a shame so this link between patriarchy and power over parenting isn’t just simply that they’re both hierarchies. Patriarchy really does create the environment where we parent like this.

JL: And then we parent like this and it perpetuates.

AA: Yes, yes, exactly.

JL: It keeps the whole thing going and so on and so on. Unless we decide to do something differently, and that decision has to be there. And then, again, we can’t just say, “Okay, I don’t want to do that anymore. But what do I do when my kid is refusing to do whatever, runs into the street, does the drugs? I have to know what I’m going to do.” And that’s where the rubber hits the road.

AA: Yes.

JL: That’s the important part.

AA: And that’s why I’m so grateful for your book and for your podcast and for all the work you’re doing because that really was me. And like I said, I did discover Parent Effectiveness Training, which I don’t know if you would endorse their methodology and their ethos.

JL: Yes, actually. Especially considering the time, right? This was out in the seventies. Dr. Thomas Gordon is the author, and I would say there’s a lot of alignment with my work. The main place where it falls short a little bit is in truly seeing and understanding each person’s needs. There’s some conflation between needs and strategies and that gets us into trouble, in addition to a bit of privileging of the parents’ desires and that the only strategy that is really acceptable from the kids is ones that fully come toward the parent and there’s no coming toward the child on the parent’s part, which is a really powerful thing to do. So, in general yes, with a couple of tweaks that I try to address through my work.

I want to try to understand what your needs are and what my needs are and find ways to meet both

AA: Yeah. Well, again, I wish I’d had your book when my kids were younger, but that’s a really meaningful and wonderful contribution then to the conversation and moving things forward. My last question for you, Jen, is a pivot from the parenting strategies and philosophies. I wanted to ask you a little bit about an author’s note near the beginning of Parenting Beyond Power, where you write that this book is for everyone, but it’s especially for white privileged parents. And on this topic of race, you go on to say, “I hear repeatedly from BIPOC authors that white people need to do their own work. And I haven’t been able to find a book by a BIPOC author that explicitly tells white parents how to work to overcome white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism.” So, yes, I’m wondering about this book and who your intended audience is and why.

JL: Yeah, thanks for that question. I think it’s really important and it was something that I really struggled with as I was writing, because there’s a long history of white folks telling everybody else how to parent, right? We told indigenous parents for centuries, “The way you parent is not very good and you should parent how we parent.” And lo and behold, a couple hundred years of that has not had good outcomes for indigenous families. And also now we realize, “Oh, perhaps the ways that we are parenting is perpetuating–” well, some of us are realizing, definitely in our broader culture there is this idea that white people should be in charge and that that’s the way it should be. So I didn’t want to be just another white person telling BIPOC people how to parent. And there are a lot of people of color who listen to my podcast, who are involved in my communities, and I kind of took it to them and said, “What do you see in this? What do you see is my role in this is the right way to approach this?” Because you quoted from the book that there are not any books that I am aware of by BIPOC authors that focus specifically on this issue.

Because the books that I have read all talk about how to talk with your kids about race and racism. And that work is critical, and we cannot stop doing that work, especially if we identify as white, we have to be having those conversations. If you’ve ever sworn in front of your child and then told your child not to swear, what does your child remember? Does your child remember the lesson of your words or does your child remember the lesson of your actions? If we’re talking with our kids about racism, hopefully somewhat regularly, but if it’s kind of an intimidating topic, maybe it comes up at Thanksgiving and Indigenous Peoples Day and maybe not much beyond that, then what our kids are actually learning from every single day is: “Does my parent listen to my perspective? Does my parent force me to do things that I don’t want to do or prohibit me from doing things that I do want to do without giving any reason and without considering my perspective?” Those are the lessons that they are learning day in, day out, every day.

And there are books by BIPOC authors that will say, “Here’s how you talk to your kids about race. And when my kid doesn’t brush their teeth, I tell him, ‘You’re going to brush your teeth now.’” So within the very same book, there’s that dichotomy. That racism sucks and you go and brush your teeth right now. So what my BIPOC listeners told me is that this framework is just as important to them but that there sometimes have to be adjustments in the way that they use it because of our – I’m pointing to myself, white parents, white people’s failings that sometimes we might see, for example, a Black or Indigenous family who sends their kid to preschool in pajamas. If I do that, it’s “I’m meeting my kid’s needs. They want to feel fluffy pajamas. My child loves feeling fluffy things on her skin, so I’m meeting her need for comfort by sending her to school in pajamas.” If a Black parent does that, there’s a much higher chance they get reported to child protective services for being a negligent parent because who sends their kid to school in pajamas, right? That’s not okay. And so that is my failure. That is every white person’s failure that we look at me doing this as “I’m meeting my child’s needs” and we look at a Black person or an Indigenous person doing the same thing as “they’re an incompetent parent.” So there sometimes have to be adjustments in the way that Black and Indigenous parents particularly use these approaches because of our failure as a society to be able to truly perceive their meeting their and their child’s needs as competence.

So it’s our responsibility, before we make that call to Child Protected Services, particularly for a teacher or a person in a position of authority, is this actually incompetence or is this parent trying to meet this child’s need? And ultimately what we’re working toward is the people having the privilege doing the most work. So if I’m a person who has racial privilege, economic privilege, maybe not gender privilege if we’re women, but in the hierarchy with transgender women at the bottom, I have more privilege than a transgender woman does. It is my job to do a lot of this work to understand that other people have needs to raise a child who understands that other people have needs and hold those needs with equal weight as their own, so that you, Black parent, Indigenous parent, can raise your child who can thrive, who can be their whole self as well. So that’s why I think it’s our responsibility to do most of the work and why I focus so heavily on the power dynamic in these interactions that seem like they’re about discipline, but actually they’re about teaching our kids about how to use power. In addition to the talking about race piece that many other people have plowed that ground more than I have.

AA: Fantastic. Oh, thank you so much. Well, Jen Lumanlan, this has been a really illuminating conversation. I’m so, so grateful, as I said before, for your book and for all the work you’re doing. As we wrap up, could you let listeners and viewers know where we can find everything you’re doing, a website, social media handles, anything that we can have so we can find your work?

JL: Yeah. I don’t love social media, I have to say, so that’s not the best place to find me. Yourparentingmojo.com is the place where podcast episodes are released, you can get notified when new episodes come out. One really useful tool that I want to make sure that your listeners know that I have is a quiz to identify your child’s cherry needs. They’re their biggest needs that come up over and over again. That’s yourparentingmojo.com/quiz. You can answer some basic questions about your child, just ten questions, it’s super, super short, and then we’ll send you a guide that explains, okay, here’s probably what your child’s most important need is and a whole bunch of strategies that you can use to try and meet that need more often. Because when you see and understand and meet your child’s cherry needs more often, your needs for peace, for ease, for harmony, for collaboration, for all the things that you’re longing for as a parent, get met more of the time as well. So that’s at yourparentingmojo.com/quiz.

AA: Wonderful. And again, the book is Parenting Beyond Power: How to Use Connection and Collaboration to Transform Your Family and the World by Jen Lumanlan. Thanks so much for being here, Jen, this was wonderful.

JL: You’re so welcome. Thanks for having me. It was a lot of fun to talk with you.

I can’t call myself a feminist and also believe

that I have the right to control what my child does

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!