“we’re not treating the birth experience with the level of preciousness that it deserves”

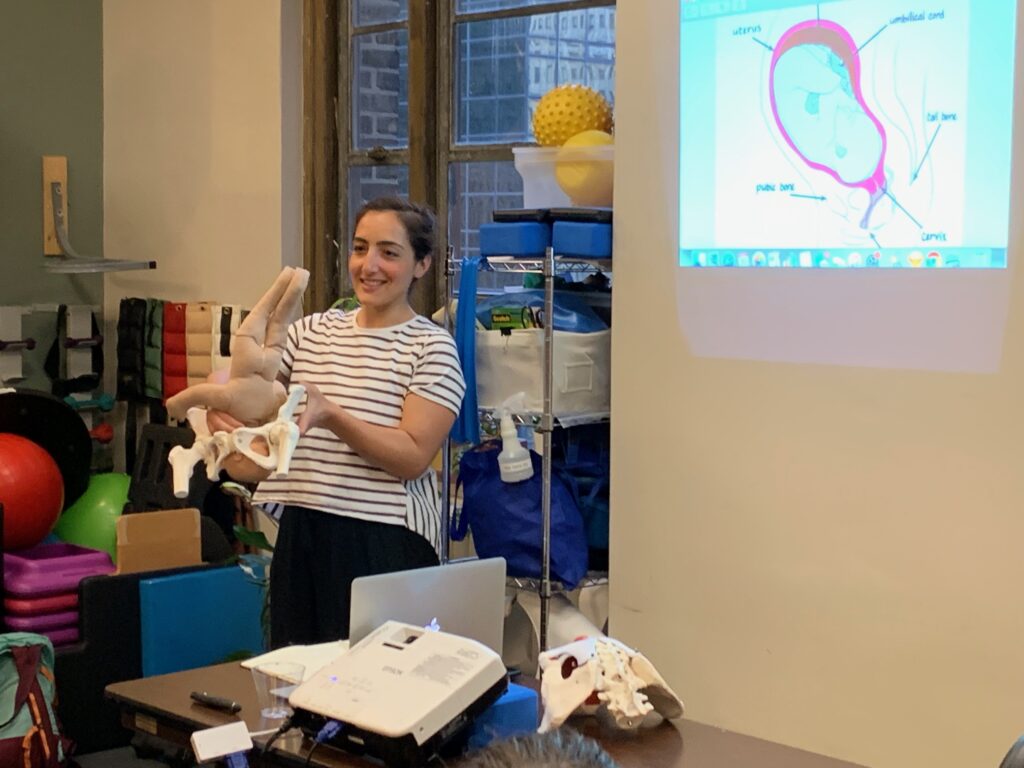

Amy is joined by Ashley Brichter of Birthsmarter to discuss her journey into doula work, the witch hunt against midwifery, and how through education and advocacy we can create better birth stories for ourselves and our children.

Our Guest

Ashley Brichter

Ashley Brichter is an educator, birth worker, consultant, and entrepreneur. She is a champion for maternal health and for systemic reforms to improve the lives of families by rebalancing division of labor at home and funding parental leave, universal healthcare, and early childhood education. She founded Birthsmarter in 2019, which provides unbiased, inclusive, and award-winning practical wisdom and guidance to the next generation of families. Ashley is a proud Bi-Co graduate and currently lives in Salty Lake City with her husband and two kids. She a Certified Fair Play Facilitator, a Tory Burch Fellow, and she sits on the board of ProNatal Fitness.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Welcome to Breaking Down Patriarchy, I’m Amy McPhie Allebest and I’m here with Ashley Brichter of Birthsmarter. I’m so excited for this conversation, Ashley, welcome!

Ashley Brichter: Thank you so much for having me. I’m also so excited.

AA: This is a topic that has been really, really important to me since I had my first child, which was, as of this recording, 23 and a half years ago. But I remember doing so much preparation ahead of time for her birth. I have four children, and each of their births was such a hugely different experience from the others, but I’ve done a lot of reading and there is an overlap between birth philosophy, birth methods, and patriarchy that I’ve always wanted to explore. Ashley and I met at Alt Summit in 2023, immediately clicked and hit it off, and maybe in our second conversation we knew that this was an episode that needed to happen. So, I’m really excited. Could we start off by you introducing yourself? Tell us a little bit about where you’re from, maybe your education and background, what brought you to Birthsmarter, and how you came to do the work that you do today.

AB: Absolutely. I like leading in my bio by sharing that I’ve always wanted to be in the education space. I feel like I show up as an educator first in the world, and that started as young as three years old when I told everybody I was going to be a teacher and loved playing with school supplies. And I learned how to read a book like face-out, I was like, “I can read this way.” And it was like, “That’s it. That’s what you’re going to do.” So I pursued that for my entire young adult life. I was the kid that volunteered at the principal’s office in middle school and high school, and I was very interested in school policy and administration. And at the same time, I was very interested in babies and families, and I started babysitting or being a mother’s helper when I was, I think, six and a half. That’s when my first cousin was born that I remember thinking, “I can help take care of this baby.” And it was both to play with the little one, but I also have always been very aware of what parents go through. I remember wanting to help my aunt and knowing that babysitting was always about doing the dishes as it was about making sure the baby was happy when I was there. I think some of that is because my parents got divorced when I was seven. We started having a shift in attention where I got to identify them as humans, as opposed to just being my parents, and I was thinking about their experience and what they were going through. So there was always an overlap of, like, how does this work, how are young people influenced, and what does that mean for the world? I knew I wanted to live in a world that was better than the one I had, and it felt like starting with young people was the way to do that.

I went to Haverford college, which is a tiny, tiny liberal art school outside of Philadelphia. And I had to study education at Bryn Mawr college, which is right across the way, they’re sister colleges, because Haverford doesn’t have the education program. I wound up majoring in political science because education wasn’t a full major, so I just minored in it. At the same time as studying in college, I worked in Center City, Philadelphia, and I got my teaching certification. I knew going in, that was actually sort of a compromise for my family. My parents were like, “You can go to a liberal arts school, but you have to graduate with a degree that you can use.” And I struggled throughout college, I had a ton of different placements, I worked in preschools, I worked in middle schools, I worked in high schools, and I struggled to really land on what I wanted to teach. I wound up getting my certification in secondary social studies, but when I was really in the classroom full-time as a student teacher my senior year, I I didn’t love it. And when I graduated from college, I had a really interesting experience where I couldn’t get hired in any of the sort of progressive, interesting schools up and down the East Coast because there were hiring freezes because of budget cuts in public education. At the same time, there’s a program I’m sure you’ve heard of called Teach for America, and that is a way that they were trying to address the fact that there weren’t a lot of qualified teachers. So four of my classmates who had no background in education all got hired to teach in Philly because they were political science majors who applied for this program and the city had signed a contract to place Teach for America students into classrooms.

And sitting with that felt really hard. I was like, I’ve worked so hard and I’m so dedicated. And the way the system is set up is really tricky. And my grandparents were teachers, my mother and father in-law are teachers. I know the system well enough to know that even if I worked it and I went into the classroom, I was going to be burning a candle at both ends and really cutting my teeth for the first five years as a teacher, pouring my heart and soul in and not making any money. I felt unmotivated, so I took a year off and said, “I’m going to not go into a school. I’m going to travel and I’m going to make money and I’m going to figure it out. And then I’ll see, and maybe I’ll go get my master’s in a year.” And during that year, I wound up realizing that I couldn’t get away from entrepreneurialism. Both of my parents and my brother, my grandparents, so many people around me in my life have started their own businesses. We have a little bit of that immigrant entrepreneurialism in our family. So I started my first LLC my first year out of college, and it was a catch-all for being a nanny, being a personal assistant, and being a personal chef. I found this niche in New York City where I could be like the right hand for high-impact women in life’s transitions.

AA: Wow.

AB: And now, looking back, I’m like, “Can I hire that person?” It was whatever. If you had a flood, I would file your insurance claim. If you were getting divorced, I would help you with your kids. And that then cycled. Somebody asked me if I was a postpartum doula, because they had a newborn and I was like, “I don’t know, tell me more about that.” There was a three-day training to become a postpartum doula to give you a little bit more context on working with families with newborns. I did that and then I was like, “Sure, I’m a postpartum doula.” And then I was like, “I don’t really know anything about breastfeeding,” so I did a lactation training and became a lactation counselor. And then somebody asked if I was a birth doula. And I was like, “Oh, I think that crosses the line,” because bodies are gross. I’m a classroom person. But I trained as a birth doula because I really liked this client. And it was very much that “Sure, I can do that” mentality.

AA: That, to me, seems like that’s a completely different arena. Childbirth is a different thing.

AB: It crossed a line. Yeah, it crossed a line.

AA: What was the training like for that?

AB: Well, my birth doula training was with Deborah Pasquale Bonaro, who is a very, very well known doula trainer with DONA, Doulas of North America, and that training changed my life. And one thing in particular, so I did the training thinking, “Alright, this is another way of supporting someone and supporting this woman who I’ve grown to really like in our interviews and prenatals. I can sit with somebody through anything that’s challenging. I know that.” The fluids were different, but I was game to try it. I’ve always been interested in birth and babies, but in the doula training program, we learned about the role of oxytocin. And we learned that in order to have uterine contractions, and uterine contractions push a baby out, you have to feel a sense of trust and relaxation. And I thought back to the most classic story in my family, which is that my mom went into a big New York City hospital, she got an epidural, she laid on the bed, my dad and the obstetrician, who was a man, ordered a pizza and were like kickin’ it, and nobody was thinking about her. And I think about how unempowered she was during her birth experiences, and how much she loved my brother and I, but she didn’t attach to giving birth. And I was like, “How did that happen? How do people not know that physiologically we need one thing and systemically we’re getting another? Oh wait, and then we’re blaming women for birth not going well.” So there was this shift where I said to myself, I deeply understand the brokenness of the public education system in the United States, I’ve studied that for nearly 10 years, and now I get it. I get what’s happening in birth before I’ve even been in there. I want to spend some more time exploring this.

AA: Wow, that’s amazing. So, then what?

AB: Then I worked in New York City and I really dove into postpartum doula work and birth doula work. My husband and I met in high school, which is very unheard of for New York City kids, and we stayed together through college. We stayed together right after college, so we were very young and got married and decided to have a baby as babies. So I was doing this work as I was thinking about getting pregnant. I did a continuing education class as a doula. There was a class being run by the Childbirth Education Association of Metropolitan New York, which doesn’t exist so much since COVID, but they led a one-day training on teaching labor support. So, if you were a childbirth educator, what does that look like? But if you were a doula, you could go and take it as a continuing education class so that when you meet with people, you had better language for, “try this position,” or “try this breathing technique.” And in that workshop, someone from the organization said, “This class is offered as part of a full training program to become a childbirth educator.” And I was like, “Tell me more. This is a job? Oh, of course, right? In the movies, there are people that teach Lamaze classes. There’s somebody that sits at the front of a room and can walk you through your journey when you’re expecting what you can expect, right?”

physiologically we need one thing and systemically we’re getting another

So it was really like this light bulb went off that was like, “I can take all of this stuff that I’ve been figuring out for the last four years and put it in a one-to-many model and go back to playing with curriculum and pedagogy and thinking about how people learn and where I can have a big impact.” I was so sold. I signed up for the program on the spot. It was a two-year program, it was incredibly comprehensive, and I worked to become a childbirth educator. And that’s just to say that most childbirth education training programs are about three days. You can do a three-day intensive and then a little bit of self study and take an exam and become a certified childbirth educator. So the quality in this field varies greatly. And I taught my first class at eight months pregnant.

AA: Oh, wow!

AB: I had three couples come in my neighborhood and they were like, “Great, we’ll take your class.” And it was so funny to be “Me too.” And then I gave birth to my daughter on June 29th, 2014. It was about 12 hours, and 10 and a half of those hours I would do again right now. They were the greatest 10 hours of my entire life. I loved every second, and then the end of my birth got really complicated. I wound up with internal bleeding and emergency surgery, and not understanding what I had done wrong because I felt so prepared. I knew so much, I made all the right decisions, and this was supposed to work. So I left that birth wondering what I needed to do differently next time. And a lot of it, logistically, there were some things about her positioning and I learned about my pelvic floor, which was not part of my original training, doula training or childbirth education training. So I learned a little bit about the anatomy and fetal alignment side that I could mess around with in my own experience, but I also really learned that it wasn’t my fault and that I needed to let go. And that I wanted to show up as a birth educator allowing for more flexibility and freedom and not be so outcome-oriented. Because most classes and people you encounter when you’re in your pregnancy journey really have some level of bias that there’s one right way to have this baby, right? If you need an epidural or if you need a C-section, okay, but the right way, especially if you’re someone who wants to be in charge and own this experience, is to have an unmedicated vaginal birth and nothing goes wrong.

And what I really realized in the two years after my daughter was born was how few people have that. And that was the difference between being in the field as a student and being in the field as a parent. I realized that I could be so much more vulnerable and other people were more vulnerable with me sharing their experiences of pregnancy and birth and immediate postpartum, and nobody was having the blissful time that was promised to us. So Birthsmarter as an organization was about four years in the making since the year after she was born. I knew I wanted to teach differently. I got pregnant again in 2017 and had my son, and that birth was both healing and utterly, jaw-droppingly confusing.

AA: Why?

AB: So, typically, in what’s called the stages of labor, which we should talk more about, we’re taught that uterine contractions last about a minute, and when things are really active, they come about every three, four minutes. My contractions with him for almost five hours were lasting up to two minutes and they were coming every nine, ten, eleven minutes.

AA: Oh, longer but more spread out. So it didn’t seem like active labor.

AB: Yeah, and a two minute contraction is like earth-shattering. In the contraction I was like, “I can’t do this,” but then the break was so long that I was falling asleep, I was getting into deep sleep, that then I had enough energy to do the contraction. But I remember he was born, I held him, and I looked at my doula and my midwife, and I was like, “The stages of labor are not a real thing,” and they were like, “No, not really.” And I was like, “Why do we still teach that?” And they were like, “I don’t know,” and I was like, “I’m not gonna teach those anymore.”

AA: Wow. That’s really interesting. Well, you know what? Let’s back up. Let’s talk about birth. For listeners who maybe haven’t had a baby or have had babies and nobody explained it to them. How would you explain it now? After all the education, including your own life experience as part of your education.

AB: Right. So, there is a way that birth is typically described, which is a linear progression of what happens. I think about it very much as if birth is primarily described the same way people learn how to cook, right? There are thousands and thousands of cookbooks filled with recipes of, like, one and then two and then three and then four, and then you get your final product. There is an amazing book called Salt Fat Acid Heat. Do you know that cookbook?

AA: I do, yeah.

AB: Samin Nosrat is a huge inspiration of mine. So the way we think about birth is more like that. There are principles that need to be applied. In order to get a baby out vaginally, three things need to happen. The uterus needs to contract, the cervix needs to get soft, and the baby needs to rotate. And uterine contractions, which come from oxytocin, our trust, love, bonding, relaxation, safety hormone, right? Uterine contractions can happen if you’re induced or if you go into labor on your own. It can happen epidural or no epidural. The interventions don’t matter when we’re just talking about what needs to happen mechanically. Cervical softening, most people actually don’t think about. Most people think about dilation, which is the opening, and cervical dilation is a side effect. So whenever you’re trying to affect change, it always makes sense to look at the root cause, right? The root cause of cervical dilation or the opening, making space for a baby, is the cervical tissue getting soft and changing shape. That tissue will go from feeling like the tip of your nose to feeling like the inside of your cheek. And it gets soft because of the release of a hormone-like substance called prostaglandins.

And when it gets really soft, and the uterus contracts, the uterus is pulling the cervix up and out of the way. So there’s a feedback loop that’s happening. Your cervix gets soft, that tells your brain to make oxytocin, you release oxytocin, you have more contractions, you pull the cervix up and out of the way, you push the baby down, you release more prostaglandins. And as that happens, and your baby rotates through the pelvis, you’re good to go. If we lead with trust and safety and we lead with freedom of movement, which allows for the baby’s rotation and allows for the baby to put pressure on the cervix to soften, we’re good, right? We’ve stacked the cards in your favor. You have everything you need to have a vaginal birth. If something’s not working, you can go back to one of those two things. Do we need to move around more and essentially you’ve got a cookie stuck in a cookie jar? What do we need to shake or shimmy or rotate? Or are you holding on to something? Are you feeling scared? Are you feeling worried and we need to do some sort of an emotional release to let go? All births make sense in that context, understanding that sometimes things can be pathological. And then we need medical intervention to help parent or baby.

AA: What an interesting, different way to look at it. Like you said, those three things need to happen, but it makes sense to me, even as you’re describing it, that everybody’s body is going to do it slightly differently. Right?

AB: Absolutely.

AA: That’s why there is so much variation and why it doesn’t really make sense to say it’ll last this many minutes, this many minutes apart. There are probably averages, but…

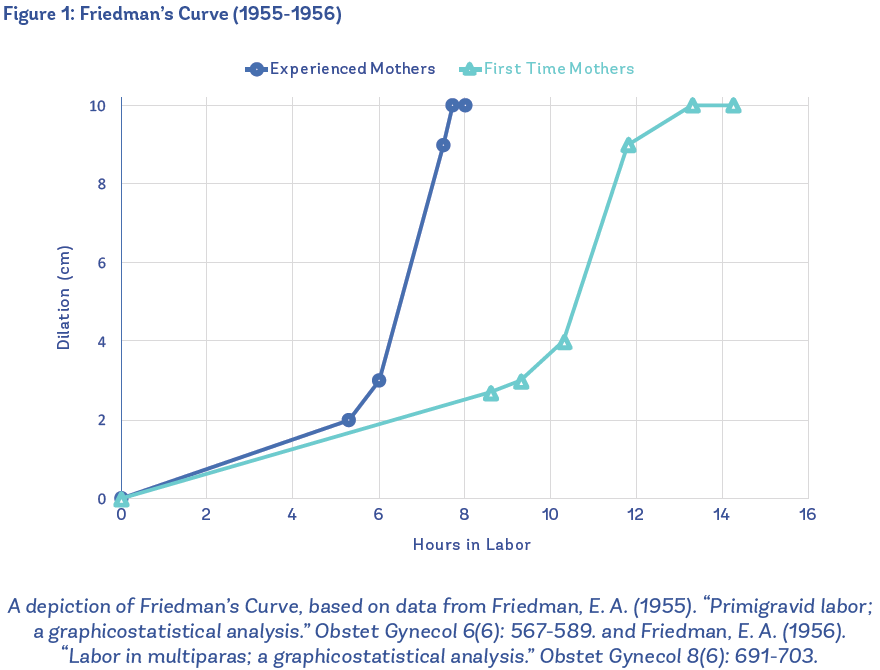

AB: Yeah, and even the averages are really hard to come by. What we operate on now came out of the late 1950s, early 1960s, and it was a study of 500 women in New York City. The doctor was Friedman, so the result of the study was Friedman’s Curve. And what they were looking for, they went into it to find the information: what is the linear progression of dilation to time? And based on 500 women, with errors in the science and in the study that would not fly nowadays, we determined that once somebody was four or five centimeters, they should dilate one centimeter an hour.

AA: Okay.

AB: And everyone has been held to that standard since.

AA: Interesting. Wow. So you’re describing this Dr. Friedman, I’m assuming a man, haha.

AB: Yes.

AA: That’s kind of leading me, as you’re describing this I’m thinking, “Yes, linear and measurements–” which are valuable, like having data and knowing averages is so valuable. I don’t mean to like diminish that at all, but that’s such a male Western way of looking at things, which leads me to ask again, like we talked about in the intro, what’s the intersection or the interplay of the masculine world with, I would imagine since time immemorial, women just giving birth in nature, not really being able to time their contractions, not really able to have a measurement, but they’re surrounded probably by women that they know and trust in their communities. They’re either in their own home or maybe they’re out in the forest, it just seems like there must have been a big shift at some point. Can you talk about that?

AB: Absolutely. Can I share one of my favorite things in teaching, though? Because you mentioned that someone could be out in the forest, and the reason that learning about oxytocin in my doula training in 2011 or 2012 changed my life is because of understanding the role of oxytocin when someone would have been in the forest. So, if you are pre-civilization and you start having contractions and you realize that there’s a natural threat, there’s a predator in the bush, the skies are turning black, something about this environment is scaring you, hormonally, that means that your newborn baby and your postpartum body will not be safe.

AA: Yeah.

AB: So, oxytocin driving uterine contractions is a physiological failsafe for humans in the smartest way.

AA: That’s amazing.

AB: Because your baby, connected to the placenta, getting all of its blood and oxygen nutrients, is safe inside your body, even if you wait four hours or four days to go into labor. So what happens when people have a start-and-stop or a “Hey, we should go into labor” body and it doesn’t quite work, is that something hormonally is telling you that you’re not ready. That your baby’s not ready or the environment is not ready. And the idea that you can get to safety and then relax and have oxytocin turn on again is mind-blowingly awesome for me.

AA: It is mind-blowingly awesome! I would never think of that. That’s true. Wow, that’s what triggers it. Safety triggers it and keeps it going, and that’s the way of nature keeping us safe.

AB: Keeping us safe. Right. Okay, so the shift. As far as we can tell, from all the birth imagery that exists, when women were giving birth, they were in an upright position surrounded by other women. Those things are true across cultures and across history. The change happened in about the 1700s in Europe with the invention of forceps. So what happened throughout human history is that women would have babies, and most of the time it went well, but not always. It is an imperfect science, so there would be plenty of situations where a baby or a mother’s life is in danger and where a baby would get stuck. And until the 1700s, we had no way of addressing that. Forceps are essentially glorified salad tongs that can go into a vagina and grab ahold of the baby’s cheekbones, actually, and rotate the baby and sort of add traction to pull the baby out. In order to use forceps well, we need a woman to be lying at a height where the doctor who knows how to use forceps can see what’s going on.

The original invention of forceps became a life-saving tool, and then there became a bit of gatekeeping and power grab around who was able to get trained to use forceps, and those were male obstetricians. And then there became a sort of subtle shift in that maybe we should trust these male obstetricians for everything, because they have this one piece of technology that can be really helpful. And I think the thing that’s worth acknowledging around the depth of nuance in birth is that it is both so powerful and empowering and awe-inspiring and works so well, and can be so terrifying because the risk of something going wrong is truly catastrophic for a family. And that’s a very fine line to walk, both thinking historically and about anybody who’s currently expecting. Is it selfish of me to want an empowering experience when that might in some way put my baby at risk or put me at risk? And should I just do this thing that guarantees an alive baby and deal with the aftermath of whatever that is? And there’s really no right and wrong there. It’s just important to acknowledge that, and that’s what we talk a lot about at Birthsmarter, where someone’s personal circumstance comes in, where we’re always going to make different choices if there’s been a history of loss, or a history of loss even in your extended family or friend circle. So, that’s something worth considering.

But in general, we started to see in the late 1700s and certainly into the 1800s, the move from birth being something that you did with the women in your community to more and more women either bringing obstetricians into their birth or starting to go into hospital settings. As you get into the 1800s, there’s also the rise of the use of anesthesia, and there’s a really interesting and unfortunate history with the intersection of both patriarchy’s role on birth but also racism’s role on birth. Especially in the United States, J. Marion Sims, who’s noted as the father of gynecology, did all of his research on enslaved women without any anesthesia. So that both moved the field forward technically, but left these generational trauma wounds in women, and especially Black women and women in the South. And since then, there has been a conflict in the United States where Black midwives or granny midwives attended the majority of births in the South for years and years because they held the ancestral knowledge of how to support women. And there were very intentional smear campaigns by male obstetricians in the United States, which was like the modern-day witch hunt of saying that these women were not trained and were not fit to be supporting birth and that the only safe way that civilized humans would give birth is by coming to the hospital.

And then we get into this really complicated, sort of self-fulfilling cycle of men saying that women should be giving birth in hospitals with obstetricians. To some extent because birth is hard and it is scary, but especially women of upper class who didn’t do a lot of manual labor, who didn’t have a lot of challenges in their life, men were like, “They’re too frail to go through this challenge of giving birth.” And there both is something and isn’t something about that. But the self-fulfilling prophecy of it is that when you then take them away from their communities, put them in an environment where they’re scared and they’re alone and they can’t move, you’re making it so that the physiology of birth can’t work and it becomes nearly impossible. One of the places that my mind almost can’t appreciate women enough is by thinking of how many millions of babies have been born under these circumstances. Because yeah, having a baby is really hard under the best of circumstances, but asking women to be alone in a hospital, scared, where nothing about the hormonal feedback loop or the physiological feedback loop of birth is working… And we’re still having our babies there. And we’re still showing up to parent there. We all get 10 extra gold stars, right? Twilight sleep was one of the versions of that in birth history. Twilight sleep was a newer version of anesthesia, in the 1920s it got really popular. Anesthesia, as we know it, puts us to sleep. Twilight sleep calmed your body enough and affected your brain so that you didn’t remember the experience, but it didn’t take the pain away.

AA: Oh, it’s like the worst of both worlds. Because I would want the opposite. So the pain is part of it, well, it’s important…

AB: It is important, right? And that’s a whole other thing, is that actually there’s no physiological benefit of pain. Childbirth doesn’t have to be painful, and there are people in the world who think childbirth can be pleasurable and there’s no pain. I didn’t experience that, I haven’t seen that, but I do understand physiologically that what we need is intensity because we need to get somewhere safe.

there were very intentional smear campaigns by male obstetricians in the United States

AA: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

AB: You want to pay attention, right? I just think it’s a lot. It’s like a lot of a lotness. That’s what having a baby is. It’s just all of it. But pain doesn’t come up, really, unless something is wrong, physically or emotionally. And so we do a lot of work in our prenatal classes to try and separate the fear-pain-tension cycle from understanding how to work with your body. But twilight sleep and Googling the images of women giving birth in early American hospitals under twilight sleep are heartbreaking because essentially they were put into straitjackets and then they came out not remembering. My grandmother had twilight sleep with my uncle and she carries really incredible trauma from both not remembering, but also feeling it. It’s a visceral memory that she has, and her postpartum was so traumatic for her to just say that she got handed this baby that she didn’t know. And I think what’s really complicated about it is that twilight sleep, the marketing was coming up around the same time that there were marketing campaigns undervaluing midwives.

And when we’re talking about feminism or sexism or the patriarchy, or any version of how this history makes sense for women, both sides of the coin make sense. For the women saying, “I want to go into a hospital and I want to get this newest anesthesia,” or even today, “I want a planned C section, I want a planned epidural. I don’t want to go through the pain, the trauma, the feeling of unpredictability, the lack of control. I shouldn’t have to do that. Men don’t have to do that. Why do I have to do that? Because I’m the one who can grow the baby.” So their version of trying to opt out or make it easier is rational. And then you have people who are like, “I don’t want doctors poking and prodding and putting me on an assembly line of what it means to have a baby in the United States because I want to be in control.” And that version is rational. And one of the hardest and saddest things that has come out of the last 200 years is that birthing parents, families, dads, everybody is now sort of pitted against each other because it’s led to this binary division of “I’m in a medicated camp” or “I’m in an unmedicated camp” and everybody has been harmed. Like in any other area where the patriarchy has set the stage, everybody’s actually harmed by the system because the system doesn’t allow for physiological birth in patient-centered care.

AA: Yeah, that makes sense. One thing that I wanted to ask you about is “medical paternalism”, because that’s a phrase that we’ve talked about on other episodes and that I think about sometimes. My sister is a labor and delivery nurse, actually, and this comes up a lot, kind of like you said, like when patriarchy has set the stage. There are a lot of components that sometimes can even be invisible because everybody’s used to it. And also sometimes when patriarchy creates a system, sometimes the system creates a culture and then the culture persists even once the structure isn’t necessarily there anymore. Like you said, it just sets the stage for everything. Can you talk about that a little bit?

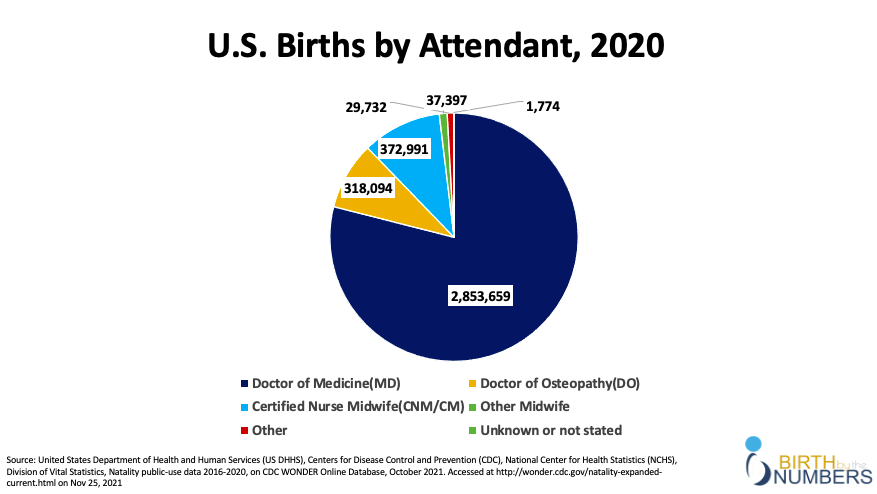

AB: Yeah, I think there are two ways that the legacy of that is still omnipresent for everybody giving birth, probably more than two. There’s an element of chain-of-command culture in hospitals, and what shifts we really want to see happen today with labor and delivery nurses compared to midwives, if they’re allowed to work, and obstetricians. A sub-piece of that is also the legacy of these smear campaigns against midwifery and what modern midwifery looks like today. And then the last piece of that, I think, is understanding the role of female obstetricians and the internalized sexism that can come up when people are like, “I just want to find a female OB,” and they’re actually still dealing with all of the same issues.

AA: Yes, I was going to ask you about that. Even just anecdotally in my experience, I had three different OBs with four different births. The one who was the most nurturing, the most safe, my absolute favorite doctor I’ve ever interacted with, happened to be a man. And then you can hear horror stories of women. So it doesn’t guarantee… So to say it’s paternalism, I think what I was implying before is that it means that patriarchal structures are undergirding the system, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that men behave in a certain way or women behave in a certain way. So keep going, but I’m really grateful that you’re talking about that because that’s something I wanted to ask.

AB: I also think that the language we would use for that is the obstetrical model of birth versus the midwifery model of birth. The obstetrical model is very linear, it tries to make birth very predictable, and the midwifery model is much more patient-centered. What is really interesting that we talk about a lot is that you’re going to have midwives that practice like OBs, and you’re going to have OBs that practice like midwives. Just like any other healthcare practitioner, choosing based on the letters after their name is generally, in my experience, not the right way to go. You’re trying to find a values-based fit and get to use sort of creative thinking about what you want your provider, your practitioner to show up with in whatever field of medicine you’re looking for.

I think the chain-of-command culture is really interesting because when birth moved into the hospital, even the labor and delivery nurses– and I think labor and delivery nurses are my second favorite players. Anesthesiologists are my first favorite players. I don’t know why anesthesiologists are just super chill, they’re always really nice and kind and relaxed and in general I have a great time with them on labor and delivery. And then labor and delivery nurses tend to be hit or miss with whether they’re working for the patient or working for the hospital.

AA: I can see that.

AB: And in general, they’re working for the hospital and they’re working for their OB. And the way we say it is that we’re teaching childbirth education classes to expectant parents with the aim of feeling like you can be on a team with all of the medical practitioners in the room. There are childbirth education approaches that will pit you against the hospital system, where that’s what advocacy looks like, advocacy looks like going in with your fists up. And you’re ready to say, “I’m going to make sure that the system works for me.” There might be medical environments where that’s beneficial, but giving birth is not one of them because oxytocin is so important. So for expectant parents, what we want to see is that they’re making the decisions ahead of time to give birth in a place where the system will support physiological birth. And that’s intervention agnostic. To me, physiological birth is that your oxytocin can flow because you feel trust and safety and you have the freedom to move around to get your baby to wiggle out of that cookie jar. And again, that can happen if you’re induced, that can happen if you have an epidural, those things are neither here nor there. But you want a provider whose North Star is that you are able to do what you need in your body. And if interventions are used, they’re used because they’re going to help you relax or take some pain or pressure away so that you can find some unique positions.

When we see labor and delivery nurses, and so many more of them are being trained right now in spinning babies and other techniques that really help them show up for the patients, sometimes labor and delivery nurses are going to be the very best patient advocates. And sometimes, and we’ve all been in this situation with nurses, they’re really cold and they really are bothered by you asking for something different. One of the innate complications of putting birth in the hospital situation is that nothing is wrong. And every other time you go to a hospital, something is wrong and you’re reliant on this medical care. And when you’re talking about having a baby, what we’re missing in our society is a safe, medically supported environment so that if there’s a risk, we have the appropriate care, but not asking everybody to be on this same timeframe. And understandably, for labor and delivery nurses who are at work, right, they’re going to need some level of efficiency and predictability to do their job in the system that we have. But that is definitely a place where we see the legacy of patriarchy and we really need to infiltrate change, because labor and delivery nurses being an advocate for physiological birth would be one of the fastest ways to change the system.

AA: Amazing.

AB: Female OBs, and complications there, that’s everywhere, right? Internalized sexism is one of the ugliest parts of this. This whole thing, the whole patriarchy system, is looking at a woman and feeling like you want a sense of security and a sense of shared experience and trust, and having someone– I think what it is, it’s like having someone choose the other side of the coin. So, to become an obstetrician, think about what that experience has been like. For a woman to break into the field of medicine and finish med school and work her way up and try to be respected in a hospital organization and in a bigger practice, there has to be some numbing to individual patient experience. And there’s some acceptance of what it means to be successful if you’re achievement-oriented and control-oriented and you’re going to play this game by these external standards. Some women get to a place in their career where being more paternal or more patriarchal is how they interpret success. And then they’re going to pass that down to their patients and say, “You should be stronger, don’t complain,” or “This isn’t a big deal,” or “I am in charge, I have this god-like complex,” right?

And, male or female, that lineage for obstetricians results in obstetrical violence. That’s obstetrical violence, that’s obstetrical trauma, that’s an OB putting their hands in a woman’s vagina to rotate a baby or cutting an episiotomy or doing any of those procedures without consent. And however we get there, and there are a lot of different ways to ask OBs to stop and pause and get a second opinion, or do additional training or have labor and delivery nurses step in, on our side of it, it’s having patients paying attention and making sure they’re asking for consent or their partners are stopping the OBs. But something needs to happen at a faster rate to slow medical providers down and slow OBs down and say, “Hey, this isn’t a run of the mill experience where you’re at work and you’re doing a surgery where somebody is asleep. It’s not even that somebody needs life or death care. What it is, is this experience of a family having a baby. The one chance that they have to welcome this baby into the world.” And that, I think, is where it pulls on my heartstrings every time. Because even for you, having had four babies, you only got to have each of those babies one time. That’s the story. That’s your birth story forever, and that’s your baby’s birth story forever, is how they came into this world. And we’re not treating the birth experience with the level of preciousness that it deserves.

AA: Agreed.

AB: Beautiful. Completely beautiful.

AA: That makes me think, if we have this system that again was created a couple hundred years ago, and that has been gradually changing, like you said, your grandmother giving birth in twilight sleep and having just truly traumatic experience. And then my mom also, I don’t know, I think they were starting to allow dads to be in the room in the hospital, but everybody was having anesthetized experiences in the hospital, sometimes dads couldn’t even be in there. I feel like it is changing gradually, structurally, I hope in a positive direction, but I’ll let you talk about that. I’m wondering what changes you would like to see in the structure, and then also if you can’t change the structure in time for your own birth, your own precious birth, like you just said, what are the changes that individuals can make? And what is Birthsmarter’s role in making those changes?

AB: Without being too much of a Debbie Downer, it’s really sad to report that the system as a whole is not getting better in the United States in the big way that we want to see. There are so many community organizations and people doing a lot of experimenting around reform where I do feel very hopeful that we will have the potential to implement really impactful changes soon. But even from when we were born, where I felt like everybody was having this sort of epidural hospital birth, we’ve seen the C-section really increase. When I was born, the C-section rate hovered around 22% and there were huge public health cries that were like, “Hey, we’ve got to lower this, this is too high.” The World Health Organization recommends a C-section rate of between 10 and 15%, so 22 is really high. And we’ve gone way up and we’re hovering around 32% in the United States right now. There is definitely a way that the assembly line model– because it’s not the epidural. The epidural, when it’s used well, is this amazing tool for childbirth. But the assembly line predictability model of birth and incredibly high insurance premiums for OBs and litigation culture are making it really hard to support physiological birth and provide patient-centered care. Because if something goes wrong and you could have just done a C-section, then that’s on you as the OB. So there are a lot of layers in what’s happening with modern obstetrical practices and limitations. One of the saddest statistics that we know is that women today are twice as likely as our moms were to die during childbirth or postpartum.

AA: I did not know that. Really? Wow. That’s crazy.

AB: Yeah. Because we’re moving at a clip where we’re not paying attention to individuals. And one of the hugest issues today, this year, in the past five-ten years, really, is the fact that Black maternal health in particular, Black women are three to four times more likely than white women to die during childbirth or immediately postpartum. And where I’m from in New York City, that can be four to twelve times higher. Between urban centers where you have huge populations of Black women or just health deserts, where hospitals are in these big mergers and hospitals are closing, you have so many places in the southern half of the United States where there is no hospital within an hour of you. Where are you even going to go for prenatal care? So, rural America is really struggling. People trying to change midwifery licensure laws to get more midwives into the world is not happening fast enough, but one of the things that needs to change. So there’s the “both and” of like, it’s not better, but I think we’re really paying attention. It feels like we’re paying attention to the industry and the humans in a very different way. And I think that as much as I hate social media, I really do think that has been a catalyst because it’s a way that women get to be in conversation with each other. I think that there’s some amount of storytelling and humanizing of what’s happening where we won’t be allowed to let this problem continue for much longer. That’s my hope.

AA: Yeah. That’s good to know.

AB: But for individuals, because it can be really scary to feel scared and still say, “But I really want to have a baby.” So how do I take this as someone who’s getting pregnant and times that by a lot if you’re a queer person getting pregnant, if you’re a black woman getting pregnant, there’s this added weight of like, “What’s my experience going to look like and how do I advocate for myself? What we say at Birthsmarter is that there’s no one right way to have a baby, and what we look at is called the Birthsmarter framework, and this is actually helpful for making any stressful decision in your life. Imagine a Venn diagram with three circles. The first thing we always lead with is, what do we know physiologically? And that, in birth, is quite literally, what do we know? What’s the awe-inspiring science? But in other cases in your life it’s just, what is true? What is universally accepted at the root? And it would be so fun to just teach the physiology of birth. Honestly, I think I like bodies enough that I would enjoy teaching that class. But it’s not enough to prepare somebody to have a baby.

the system as a whole is not getting better in the United States in the big way that we want to see

So then we add in this level of what is the societal context, and how do we have to actually pay attention to where patriarchy, capitalism, racism are tying our hands behind our backs. It’s like, “Here’s the starting line of this race and you guys all have to move back 10 yards. It’s going to be a little bit harder for you.” And knowing that going in doesn’t have to make you a victim and it doesn’t have to villainize anyone or anything in modern medicine. It just allows us to sort of neutralize the landscape of what we’re going to have to navigate. And then the last piece of the equation is what’s your personal circumstance? I mentioned that earlier because infertility and loss is something that would put you on a very different path of decision-making than not, right? But other things like that are your sexual orientation or how you identify, your weight, your race, your socioeconomic status. What I love about it is being able to sit in a room with nine expectant couples who have all chosen to take the same prenatal class on the same day in the same city, they should have a lot of similarities, and knowing there are going to be nine ways to have a baby and nine ways to raise that baby. That is actually a very beautiful part of living in this world.

So we lead by encouraging everybody to be nonjudgmental about themselves and not putting the weight of the world on their shoulders. And being nonjudgmental about each other so that we can get out of the binary of “This is right, this is wrong. I’m really judging you for wanting X, Y, or Z or not wanting X, Y, or Z.” And part of what we talk about beyond that is just this idea of letting go and being comfortable with what happens. And it’s not to say you shouldn’t do any preparation. Megan Davidson is an amazing doula in New York City, and she wrote a book called Your Birth Plan, and she draws an analogy to planning a trip, like a big summer vacation. Those of us who have traveled at all know that you sometimes miss your flight and you sometimes get to a hotel and you’re like, “Oh, nope!” Or you get food poisoning when you try this new restaurant, but that doesn’t make it so that you shouldn’t prepare, you shouldn’t get the book from the library and read about the place you’re going and make a loose itinerary and sort of sketch it out. So when we have people who are expecting, we don’t really want them to be in the category of, “Oh, people have been having babies before me and people will be having babies after me, I’m just going to wing it.” Because that’s not giving them enough to root into, to stack the cards in their favor and make the best decisions.

And we also don’t want people who are either so scared or anxious that they are trying to plan every specific move that they’re going to make where they have these 10-page birth plans and they’re like, “Why isn’t my OB reading my birth plan?” Because that’s not how it works either. And I think talking specifically about the epidural is a really interesting place to get at this. If we have a class, a childbirth education class at Birthsmarter, this is how we start the conversation, which is to say, “Some of you are in this room, you’re taking a childbirth class because you don’t want an epidural. You have worked 20, 30, 40 sometimes years to be in your body and you’ve been waiting to get pregnant and you’re excited to have this baby and you want to feel it. You want to experience it and the epidural in some way is going to take that away, right? That means that a doctor is going to be poking and prodding and they’re going to be in charge and you want to be in charge. You want to be in control. And that’s really wonderful. There are also people in this room who are coming to a childbirth class, but they know they want an epidural. But they want to know enough about the field that they’re going to be walking in to navigate the rest of it, or how can I get an epidural without it increasing negative consequences? And they really know that they want an epidural because they’ve worked for 20, 30, 40 odd years in order to feel a sense of control and a sense of self, and they don’t want to be howling at the moon. They want to be in the box of who they are and what they understand, and that really makes sense.”

And when you start to look at a choice like making an epidural in that way, and you can really deeply empathize for how scary it is to stand on the threshold of “I’m going to have a baby,” the desire to be in control is universal. And for me, I think what’s so interesting about this podcast and this episode is thinking about how that is in some way playing into the fact that we have all been raised, we have all been socialized to live in a patriarchal society where being in control is the gold standard and actually getting ready to have a baby is going to push every single human to not be in control. You can’t predict if you need an epidural or you don’t need an epidural because you’ve never had this baby before and you don’t know what your body is capable of. And the ask for us in Birthsmarter childbirth education classes is for expectant parents to sit with that and to contemplate what it would mean to show up and not be in control. And preparation for unpredictability is very different from preparation for “Here’s the recipe and I have everything that I need to be successful.”

AA: Yes. So true. That’s so true. I’m thinking through my births and my friends and my sisters and yes, they’re all so different. I love the trip analogy. That’s so useful. And I think one thing that really blew me away and I’ve carried it with me and will for the rest of my life was that experience in childbirth of digging deep into this strength that I had built up over the course of my life and watching in absolute awe at what my body was capable of and what Amy was capable of. You know, like the involuntary stuff that I had no control over, but then the way I participated in it mentally, emotionally, and I really drew on past strength that I had built. So in that sense, yes, being in control like, “I can do this,” and paradoxically at the same time, you have to let go. You have to let go. And hanging on to the fear or hanging on to the pain shuts everything down, it makes it hurt worse. And being able to let go and lose control at the same time, it was unlike anything else I’ve ever done and was profoundly strengthening for the rest of my life to watch myself do that.

AB: The phrase that we play with a lot at Birthsmarter is a “pregnant opportunity,” and that could be a really nice reflection or a way to put a pin in what you’re saying, because I felt that so deeply. I feel like a much better person after I gave birth and a much better person after I’ve parented, because I looked at these moments as these opportunities to figure out the relationship I had with my body and the relationship I had with my mental health and the relationship I had with my partner and the relationship I had with Western medicine. And all of those things have carried me into parenting, they’ve carried me into being an entrepreneur, they’ve carried me into being a friend, where I was forced to look critically at what I was capable of and who I wanted to be. And that opportunity is what I want everybody to grasp and feel like there can be real intentionality around. And that childbirth and having a kid isn’t something that has to happen to you, because having a baby can be awesome.

AA: Yeah. That’s fantastic. Well, like I said, I did do a lot of preparation before each one of my births, and that really, really helped me. For any listeners who are pregnant or maybe planning to have a baby in the next little while, I do think it’s something, like you said, Ashley, that you want to do a lot of preparation for and then that also includes being prepared to let go of control! Wow, I would have loved to have you as a resource as I was preparing for those births. Can you tell us, just as we wrap up, tell us where listeners can find Birthsmarter in person, or if you have an online presence or access to materials online, how can people find you?

AB: Yeah. Birthsmarter started in New York City and we still teach a ton of childbirth education classes in New York City. And then in COVID, we brought everything online. So we have on-demand childbirth education classes and live virtual classes on Zoom so that you can live even in New York, but you can live wherever you want around the country or the world and still have the accountability of a date and a teacher to ask questions to. The three options for us, the in person, virtual on Zoom, and on-demand, meet people where they are. And we’ve started expanding city to city. We teach in Salt Lake City, in Phoenix, in Denver, and in Portland, Maine. I might be forgetting some, but they’re all at birthsmarter.com. And we’re expanding very slowly with a teacher training program. The other thing that is newer for us is the Birthsmarter teacher training and certification program for folks that want to learn how we think about birth and how we set up our classroom environment and use our curriculum and bring Birthsmarter classes across the country and across the world.

We didn’t say this earlier, but childbirth education, as we know it, really came out as a response to what was happening in the late 1800s and early 1900s where women were losing control. And Lamaze childbirth education and Bradley childbirth education were sort of parallel. They didn’t have anything to do with each other, it seems, but they were parallel voices in about the 1940s saying, “Hey, this doesn’t have to be scary. This doesn’t have to be fearful. Your partners can help you. Your community can help you. Breathing can help you. Let’s be intentional about it.” So childbirth education in this sense of, “Hey, let’s go take a class,” has really been around for nearly a hundred years. I think Birthsmarter is just the first organization that is looking at it in more of a nonjudgmental, partner-focused, very inclusive and accessible way to not have it be just a reaction to, but a really reframing and rebuilding of what is possible for the whole family.

And that’s the other thing I would say, is that I think Birthsmarter might not be the best fit for everybody. If there’s somebody who’s really type A and just wants to be told what to do, we’re not the best because we really encourage critical thinking and we love curiosity and we love people who have an open mind and want to investigate and think and learn, even if it doesn’t apply to them. But we are very proud to be very partner-centered and the curriculum is as much, if not more, written for whoever is going to be supporting you. Not just to support mom or the birth parent, but because they’re becoming parents too. And then our accessibility program is really important to us. We’re inclusive by design in our curriculum and our language, but we’re also financially accessible to everybody. There’s an alternative pricing program that means nobody will be turned away from a Birthsmarter class due to lack of funds. And all of that is to try and get the highest quality, most thoughtful preparation for expectant parents out there as we can, because it is so important and we want to give people whatever support we can.

AA: That’s so inspiring. This is just an incredible resource. I’m so grateful it’s out there. Thank you for the work you’re doing and I’m super excited for people to go check out your work online, and hopefully, if they live in a city where you’re in person too, can check it out. Thank you, Ashley Brichter, so much. Thanks for being here today. I so enjoyed our conversation and I learned a ton.

AB: Yeah. Thanks so much for having me. It was so fun!

Like in any other area where the patriarchy has set the stage,

everybody’s actually harmed…

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!