“children were not being educated so much as they were being held hostage”

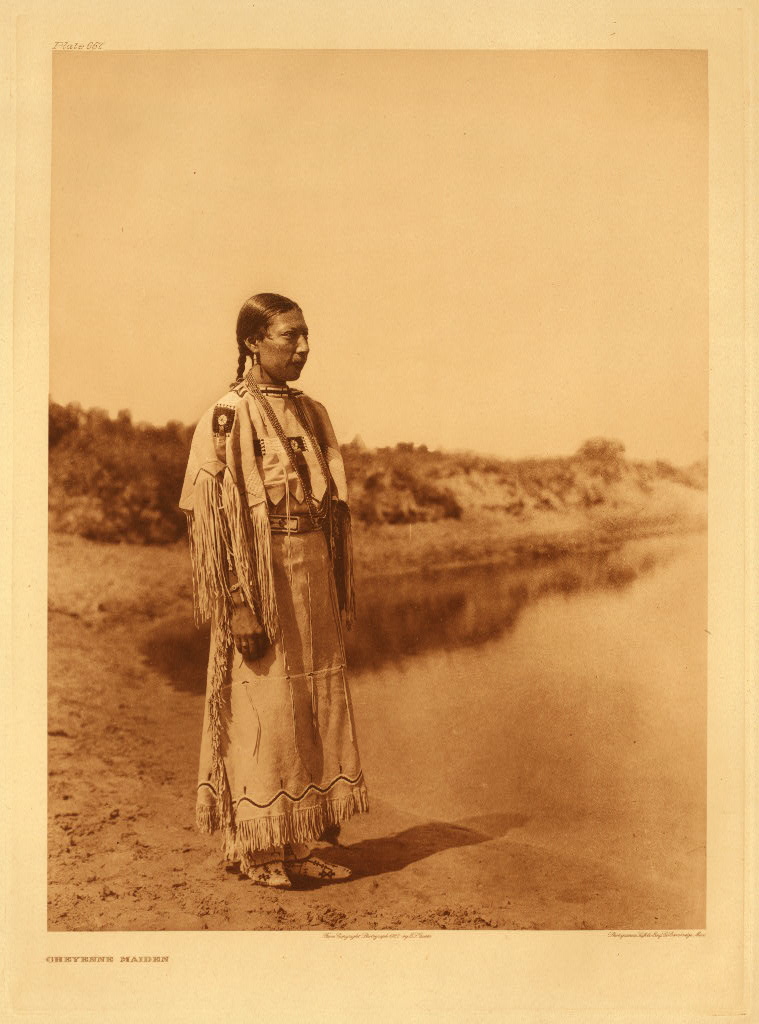

Amy uses Dr. Henrietta Mann’s book, Cheyenne Arapaho Education, to explore the history of the Cheyenne (Tsitsistas) people of the Great Plains, investigating historical gender roles, the devastating effects of white supremacy and colonialism, and the shameful history of American Indian Boarding Schools.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In the winter of 2024, I took a class on Native American education as part of my PhD program at the University of Utah. My class was taught by Dr. Connor Warner, who was a fantastic teacher. He’s a white guy, but he grew up on the Cheyenne reservation in Montana, and he’s married to a woman who is an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Chippewa tribe. And by the way, I learned through this class that being enrolled usually means that you have a certain amount of Native ancestry, and different tribes have different criteria for being enrolled members.

Here’s another thing that I learned through this class and through other classes that I’ve taken in Native American Studies. Native peoples and scholars use the terms Native American, Indigenous, and Indian to describe Native peoples, and in Canada, they usually refer to Native peoples as First Nations. I had thought that “Indian” was an outdated, if not offensive term. And having a lot of friends from India, I do find it also kind of confusing. But I’m just saying at the beginning of the episode that while I usually use the terms “Indigenous American” and “Native American”, I have started sometimes saying “Indian” because that’s what my books and teachers and my Indigenous classmates often say.

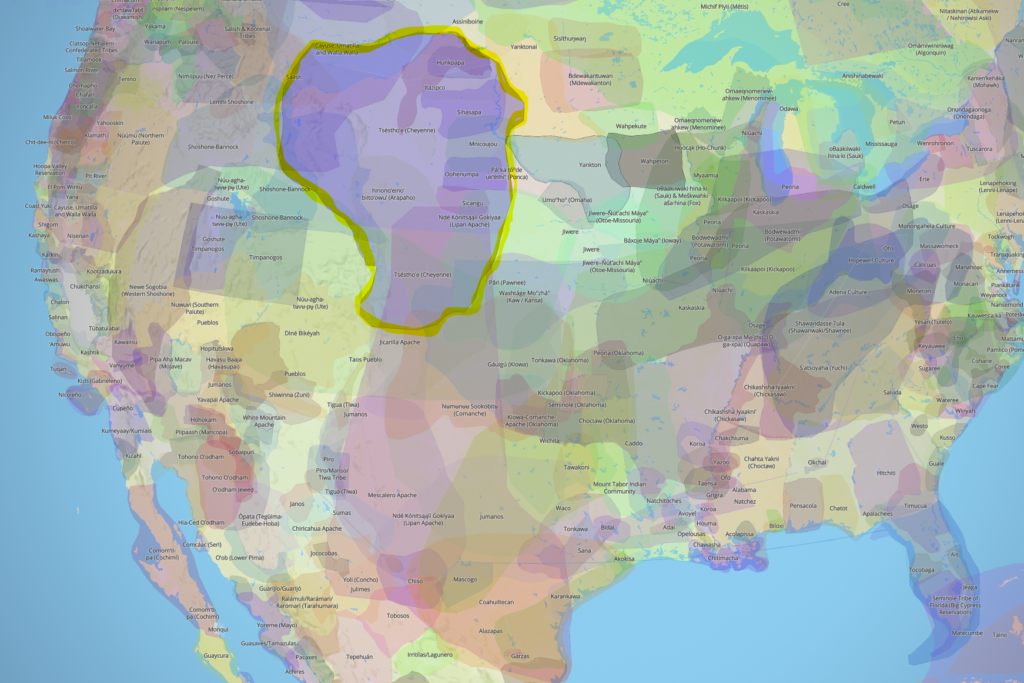

For our final project for this class, we were asked to choose a tribe and study their history, particularly the history of education. I knew immediately that I wanted to study the people whose land I had grown up on in a suburb of Denver, Colorado. So I went to a website called Native Land, which maps indigenous land all over the world. It’s amazing, and I highly recommend that you do this. Go to native-land.ca and you can type in a city and state or a zip code and see whose land it is. I learned that Greenwood Village, Colorado was Cheyenne land, so I decided to study the Cheyenne. Today I’m going to share some of what I learned about the Cheyenne tribe.

In terms of sources, I drew heavily from the work of Dr. Henrietta Mann, who is a full-blood Cheyenne enrolled in the Cheyenne Arapaho tribe of Oklahoma, and she had an amazing career. She was the endowed chair in Native American Studies at Montana State University, Bozeman. She’s retired now, but she also taught at UC Berkeley, she taught at Harvard, and she taught at the Haskell Indian Nations University located in Lawrence, Kansas. Dr. Mann has served as the director of the Office of Indian Education Programs and Deputy to the Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In 1991, Rolling Stone magazine named Dr. Mann one of the ten leading professors in the nation, and in 2021 she was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Biden. Dr. Mann is now 89 years old and is retired, so I couldn’t get her on the podcast, but I’m using her book, Cheyenne Arapaho Education 1871-1982 as the main source for this episode.

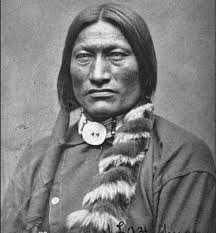

Let’s get to know the Cheyenne. First of all, where did the Cheyenne get their name? Well, the word “Cheyenne” comes from the Sioux word Šahíyena, which means “unintelligible speakers.” And the Sioux called them this obviously because they couldn’t understand them. This was during a time that they all lived in what is now Minnesota in the 1500s. The Cheyennes speak a language that comes from the Algonquin family and Sioux is a completely different language family, so they couldn’t understand each other and so that’s why they called them the people with the unintelligible language. The Cheyenne, however, refer to themselves by a different name, and that name I’m going to try to pronounce correctly. It’s spelled T-S-I-S-T-S-I-S-T-A-S. So it looks like it’s Tsitsistas. And this name didn’t appear in print until the late 1800s, and it’s not generally used by non-Cheyenne people, both because the term “Cheyenne” is embedded in American historical documents, and so we’re all used to that, and also because it’s super difficult for English-speakers to pronounce. But Tsitsistas is what Cheyenne speakers call themselves.

My next question was, how did the Cheyenne end up living near the Sioux in the first place, since Sioux Territory is in the Dakotas, and Algonquin Territory, as far as I knew, was in Eastern Canada? The short answer is that they moved around a lot, even before they were displaced by white settlers. The longer and more interesting answer is that the Cheyennes say that in the most ancient times they did live far to the Northeast in what we now call Canada, where they had a hunting economy and they subsisted on wild game. And then a terrible illness struck and the grief and fear caused by the epidemic prompted them to leave their ancient homeland and to move to what is now Minnesota.

Their oral tradition passed down through generations and generations says that on their way while they were migrating from that area in the northeast toward the southwest to what is now Minnesota, they say that the Great Creator sent a prophet named Sweet Medicine. Sweet Medicine made a huge impact on Cheyenne culture. When I was reading about this figure, it kind of reminded me a little bit of who Abraham or Moses would be in the Judeo-Christian tradition because he gave the people laws and religious traditions. He also organized military societies led by war chiefs, whose duties were to keep order and to maintain a hunting territory. He also established a judicial system operated by 44 senior men known as peace chiefs. And he established four major laws prohibiting lying, cheating, marrying relatives, and inter-tribal murder. He devised their value system, which consisted of love, respect, cooperation, generosity, understanding, humility, and maintenance of the Cheyenne way of life. Most importantly, Sweet Medicine gave the people four sacred arrows and an accompanying ceremony, which was called the Arrow Renewal. Henrietta Mann says that the Cheyenne’s distinct identity as a tribe has as its very foundation the four sacred arrows, the holy gift from the creator. Tradition says that during the 446 years that Sweet Medicine lived with the Cheyennes, they were happy and life was good. This is, again, all according to Dr. Henrietta Mann.

In addition to the visit from Sweet Medicine, the Cheyennes also acquired another companion while they were moving from Canada to Minnesota. They learned to tame the dogs that inhabited that area, so the people named this whole era of their history for the animals that traveled with them in search of a new home. Thereafter they referred to it as “the Time of the Dogs.” By the 1670s, the people – they call themselves “the people,” and I know the Navajo or the Diné refer to themselves as also “the people” and the Cheyenne do as well. So, the people were living in southwestern Minnesota and a group of Cheyenne men traveled east and they found a French explorer and fur trader named LaSalle and his men. This was their first contact with Europeans coming into their land, and this was really scary for them since Sweet Medicine had prophesied about white men with hair on their faces who would end up taking everything from them. And this historic meeting between Cheyenne and LaSalle’s men occurred on February 24th, 1680, near what is now Peoria, Illinois.

This is a really interesting, important moment because Mann writes that some Cheyennes attempted to avoid contact with the white men altogether, others tolerated their strange ways and welcomed them in friendship. Mann writes, “Thus, three centuries ago, the white men’s presence forever dichotomized the Cheyenne world.” Like, how are they going to deal with these newcomers, these new people? This division is another theme that’s common among Native American nations, and actually among many indigenous peoples who are colonized by outside aggressors. I can totally imagine that if I were in that position, I might be really torn about which strategy to use, whether to make friends or avoid them or fight. I can absolutely see how people would have different approaches. We don’t get to know the future in the present moment, and those approaches and strategies deciding what to do could cause a lot of contention within the community. But anyway, back to the timeline.

In the early 18th century, the Cheyenne began buffalo hunting trips. They were an agricultural people before this, they would do farming, but they started going on buffalo hunting trips to the plains. For a while they would return from the hunts to harvest and take care of their crops, but during this time, they also started adopting some things from these European-American white people, and they adopted steel knives. That was a big deal. And multicolored beads was something that they traded for, so they started creating beautiful art and adorning their clothing with just this amazing, beautiful beadwork. And most importantly during this time period, the Cheyenne got horses from the Europeans, and that ushered in the age of the horse. Henrietta Mann says that “the horse so dramatically altered their lives that in a brief 25 years, the Cheyenne evolved into equestrian hunters of the buffalo.” It’s said that “the rider and the animal became like one integrated animal.” This was kind of surprising to me. I had pictured The Great Plains Indians hunting buffalo on horseback since time immemorial. But of course, I sort of forgot that horses arrived with Europeans and they only reached the interior of the country gradually, so kind of recently, actually.

The Cheyenne kept migrating west from Minnesota and kind of to the south as well. And their culture increasingly centered on buffalo, which they used for every part of their life, their food, their clothing, and their shelter. And they also acquired a buffalo hat with buffalo horns that had a spiritual power along with the four sacred arrows. So the buffalo was very, very central for them in their lifestyle and also spiritually. Also in the 19th century, other big things happened. They met the Arapaho peoples, with whom they formed an alliance that persisted to this day. You may have noticed that Henrietta Mann’s book is called The Cheyenne-Arapaho. They have completely different languages, they’re not mutually intelligible, and I am assuming they began communicating in some sort of lingua franca because they became very, very strongly allied together. They spread through Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado. And although the Cheyenne and Arapaho were both small nations with about 3,000 people each during that time in the 19th century, as a combined military force they were very powerful. They kept the Kiowa, the Shoshone, the Blackfoot, and the Pawnee Indians out of their hunting territory, so they protected the integrity of their land, the barriers and borders of their land. The Cheyenne became the dominant traders in guns, horses, and buffalo skins in the central plains. During this time, at kind of their peak, they had land that stretched from Montana all the way down to Texas and then to the east included the Oklahoma panhandle.

the white men’s presence forever dichotomized the Cheyenne world.

So, what are some aspects of Cheyenne culture, especially regarding gender? I didn’t have to study this for my class, but of course, because I’m me, I’m always looking out for things like that. I’m just curious about what the gender dynamics were. And here I want to point out that I’ve heard many people state that “Native Americans are matriarchal.” It’s really, really important to remember that North America, let alone Central America and South America, but even if we’re just talking about North America, that’s an entire continent and it has more than 570 federally recognized tribes, hundreds of languages, and as many cultures. So if you ever hear someone say “Native Americans think X,” or “Native Americans believe Y,” that’s a red flag, because there is way, way too much variety to make generalizations like that.

Regarding men and women in leadership, like whether it’s patriarchal or matriarchal, it is true that many Native American groups are matrilineal, many are matrilocal, some have women in their governing councils. Some do. And there were certainly far more egalitarian practices on the North American continent than in Europe at the time, for example. That’s definitely true. But the Cheyenne were and are patriarchal. Their creation story involves a creator who is described with masculine pronouns. I will say, and I’m not sure, I would have to look into this more, but because the stories were passed down orally for thousands of years and they were only written down by European Christians in the 19th century, it’s possible that some of these stories did acquire some aspects of European patriarchy, some aspects of perhaps even European religion. I don’t know, I’m not sure. But you always have to think about the sources and who was writing them down and that there might have been some fingerprints on there. But according to everything that I’ve read, their great creator was thought of more as a father.

What we know for sure is that in Cheyenne culture, their prophets, like Sweet Medicine, were men. All the peace chiefs who made the decisions were men, and the spiritual and medicine people of the tribe who were vested with the highest authority were men. And a few more things about Cheyenne culture that I found fascinating. Henrietta Mann writes a lot in her book about her own great-grandmother, White Buffalo Woman, who was born in 1852. She met her great-grandmother when she was little and her great-grandmother was old, so she kind of touched the lifetime, a lifespan of someone who had lived during an incredibly volatile time and where lots and lots of changes had happened. The way her great-grandmother lived, having been born in 1852, and then the way she has lived, and again, she’s still alive, it’s really stunning to cover that much change in that family. So she writes about her great-grandmother, White Buffalo Woman, that “when she was conceived, the Great One participated in the act of love of her parents by creating a spirit, which was nurtured in the womb of her mother as she journeyed to the world. From the second she was conceived, she was a person. Abortion was not practiced or condoned. To abort was to become a murderer and incur the penalty for murder, which was usually exile from the tribe.” And again, I want to point out the huge range of belief and practice between Native American tribes. Some thought of abortion as acceptable and some did not.

Mann continues to write that tribal custom dictated that a pregnant woman should look upon and think only of the beautiful, avoiding the ugly as much as possible, which would ensure that the child would be beautiful and healthy. Shortly following birth, usually in the early part of the day, the midwife would take the newborn infant in her arms and introduce the child to the sacred persons in the tribe and the sacred directions of southeast, southwest, northwest, northeast, up to the heavens and down to the sacred earth. When White Buffalo Girl, that was the name she was given when she was born, when White Buffalo Girl was born, she was named for a respected relative on her father’s side of the family. When her umbilical cord dried and fell off, it was sewn into an elongated diamond-shaped case, which was then ornamented completely with beads. Had she been a boy, the umbilical cord would have been preserved in a beaded case that was shaped like a turtle. The little case that had the umbilical cord in it was initially fastened to the baby’s cradle board, but as the baby matured, then the person would tie it to their belt along with their awl and their knife sheaths, which was such a cool detail too, to know that you would always have a belt with an awl and knives attached. And your own umbilical cord.

Henrietta Mann continues and she writes, “As is true for all Cheyenne babies, White Buffalo Girl was loved. For the first few months of her life, her mother and other female relatives spent much time holding her and protecting her from the weather. When she grew stronger, she was placed in a cradle board. And then when she could walk, her childhood education began. She was never whipped or punished, but was taught to be quiet in the presence of her elders. She discovered that needless, excessive crying resulted in isolation rather than attention. And this lesson, repeated often enough, led to self-control and consequently, quiet.” It’s an interesting cultural value, the quiet of children around adults. Really interesting. She continues to write, and again, she’s still writing about her great-grandmother’s childhood as she imagines it and kind of as emblematic for Cheyenne children.

“She was taught to cultivate qualities such as courage, honesty, strength, skillfulness, creativity, perseverance, and decisiveness.” Again, so interesting to choose those words. I thought, what would I choose for my family’s values that I want to instill in my children, my community’s values? And I thought, I don’t know that they wouldn’t be the same, as I’m thinking about it. Courage is the very first one. Courage and then honesty, definitely, strength, definitely, but then skillfulness, that’s interesting. Creativity, perseverance, and decisiveness, that one really stuck out to me. “White Buffalo Girl became White Buffalo Woman upon reaching puberty, when her parents gave away a horse to mark her transition to adulthood. Thereafter, she no longer imitated adult life in play, but was expected to conduct herself as a woman of the people. Above all, she was taught to hold the Great One first in her life and to revere the sacred Earth Mother and to respect all life, human and animal.”

So now to the topic that my class was specifically studying: how are the Cheyenne educated? Mann writes that in traditional Cheyenne culture, the medicine people and chiefs were great examples, but the parents and paternal aunts and her grandparents and other elders were the teachers for the next generation. And again, it’s just so interesting how every culture educates its children about how to be successful adults in their society. So, of course, Cheyenne children were educated in the same way. What is going to be required of you to function in the community and to ensure survival in the world that we live in, right? For the Cheyenne, their world was extremely connected to the land and to the buffalo. And their work was divided by gender, just like just about every culture on earth until very recently. For example, men were hunters and warriors responsible for feeding and defending their families. A woman might occasionally become a hunter or a warrior, but not usually. Women owned their houses, which was much more equitable than European and American culture at the time, of course. And women’s other jobs were to carry wood and water to camp, put up and take down the teepees as they moved around, prepare food, make clothing, and care for children. Both genders took part in storytelling, artwork, and music, and in traditional medicine.

In Mann’s book, she writes a section that I found interesting because she frames Native education in a way that white settlers would understand. She says, “As the tribe moved over the plains, the young people learned the geography of the land. Courses in biology and science were offered in which the students learned the ways of the animals and the uses of plants and herbs. Education was not separated from life, but was intertwined with it.” And in terms of history and literature, Indigenous peoples in what is now the U.S. didn’t have written language like the Aztecs and the Mayans did, just south of what is now the U.S. and what is now Mexico. The Aztecs and Mayans did write stories in a different system than our phonetic one, but they did write. In what is now the U.S., there was no written language. What they had instead was a very sophisticated oral tradition where the elders would tell stories and then they would test the children on that oral history as they grew up, and they took it very seriously. Oral literature was divided into categories, such as the sacred stories of creation and the prophets, tribal history, hero stories, mysteries, war stories, and ve’ho’e stories. “Ve’ho’e” was the term for both spider and white man, and it represents an intelligent mischief-maker or villain who complicates life for himself by failing to respect Cheyenne traditions. The children learn stories about examples of ways that the white men misdirected their intelligence and had an inability to listen and follow instructions.

Basically, after they started interacting with white colonizers, the Cheyenne developed a whole category of cautionary tales teaching their kids to not be like white people. And honestly, who can blame them, right? Since the white people came and stole their land, murdered their people, broke their promises, and drove the buffalo to extinction in the most obscenely wasteful way imaginable. It’s understandable that they would take on the character of a villain and someone that you did not want to be like. But anyway, those were some of the points of traditional Cheyenne education. And I want to point out here something interesting that came up in class on the subject of verbal and auditory learning. I just learned that once human beings go from solely oral tradition to written language, they do gain certain skills and abilities from writing and reading, but their brains also lose certain skills and abilities. And this makes sense to me. I’m old enough to remember a time before cell phones, when I had tons of people’s phone numbers memorized, and now I don’t even know all of my children’s phone numbers! So, you can just observe that in your own life. Once you externalize the mechanism of holding information and it’s not in your brain anymore, you don’t have to remember it, you do lose the capacity for memory. The brain just starts to work in a totally different way. The capacity for remembering things in an oral society is hugely, hugely expanded and really, really important.

I want to say one more word about language, because due to the boarding school system, largely, which we’ll talk about in a minute, now a lot of native languages are going extinct. So whereas they weren’t traditionally written and transcribed, they’re now being transcribed in order to preserve them, and there are revitalization efforts going on in a lot of native languages. My professor for this class, because he was raised on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation, knows a lot more about the Northern Cheyenne and their numbers were hugely reduced during COVID because COVID hit Native communities so hard and also elderly people. And in many communities, it’s only the elderly that remember their native language, so it’s at a crisis point in a lot of Native communities to get videos and transcriptions of the language so they’re not lost forever.

Next question, what are some important historical moments as the U.S. forces moved west onto Cheyenne land? I’ll give a very abbreviated chronological timeline. In the years between 1825 and 1865, first of all, an important thing to know is that the Cheyenne, who had been one people, had divided into a northern band that lived mostly in Montana and northern Wyoming, and then a southern band that was allied with the Arapaho and lived in southern Wyoming and Colorado. This was partly due to the path that the white settlers were taking that was getting rid of the grasses and thus the animals. It had kind of made a cut across the northern and the southern Cheyenne and so they split and became two different tribes. A lot of what happened in their negotiations with the U.S. government happened to them both, sometimes in different ways and sometimes in the same ways. The U.S. negotiated four official treaties with the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, each of which were just ways for the U.S. to acquire more land.

Henrietta Mann, I’ll mention, she’s a Cheyenne-Arapaho. She’s from Oklahoma. The southern band ended up going to Oklahoma and the northern band ended up going to Montana. So she’s Cheyenne-Arapaho from the southern one. She writes that “The people could not understand the white man’s obsession with control and manipulation. Such behavior was incompatible with their people’s way of life and worldviews, especially in relation to space and time concepts.” So they didn’t even really have a way of understanding when a document or when a negotiation included ‘in perpetuity,’ because time was cyclical for them. They conceptualized space and time as rhythmic cycles that flowed in a circle. Mann writes, “They consequently walked in balance with all life and accepted the order of all things about them.” And because of this completely different understanding of land and time, the Cheyenne didn’t understand at first that they were being manipulated into giving their land away, and that they would never get it back.

By the mid-1860s, more and more white settlers were arriving on their land, and the native occupants were defending their territory, sometimes violently. And I think this is one of the classic injustices of colonization. The colonizer commits violence by going to the land in the first place and forcibly taking it away, and committing violence against the people who live there. But then as soon as the people fight back, then the colonizer accuses the victims of causing the violence. The oppressor can claim that the oppressed are the ones who are thwarting the peace process, because they’re simply defending themselves. And this is what happened with Native Americans more broadly, and with the Cheyenne people specifically. White settlers started viewing these Indians as scary, and barbaric, and fierce, and violent, simply because they were fighting back against what was happening to them.

There were a couple of inflection points where huge tragedies happened to the people. One was on November 29th, 1864, when Colonel John Milton Chivington, who was interestingly a former Methodist minister-turned-soldier, led his troops in a surprise attack upon a camp of Cheyenne in the early morning hours while everyone was still asleep. Chief Black Kettle congregated the people around his lodge where he was flying a large American flag and a smaller white flag of truce or surrender. But despite the flags, the soldiers continued the slaughter for eight hours, killing 137 people, 109 of whom were women, children, and the elderly. Henrietta Mann’s great grandmother, White Buffalo Girl, was there at the massacre. She survived and she was traumatized for the rest of her life, and she always kept her moccasins on from that day forward. Always, even while she slept, because she was always afraid that she’d have to run. Colonel Chivington and his soldiers were never punished for what they did.

Then, after many broken treaties with the U.S. government, the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho were forced to move to Oklahoma by the Medicine Lodge Treaty in 1867. As they were walking to Oklahoma, many people died from disease on their way there, but they believed they had finally negotiated peace with the U.S. Government, so Chief Black Kettle accepted that they just needed to move to Indian territory in Oklahoma. It was at this point that the next horrific massacre occurred. They were camped along the Washita River along with Sioux and Arapaho and Kiowa and Comanche peoples who had all been pushed out of their lands and they were thrown together on reservations and all on the move. White Buffalo Woman was 16 years old at this point. She and her family were at that camp with Chief Black Kettle again when the U.S. soldiers struck. This time it was on November 27th, 1868, again in the early hours while they were all asleep. The camp was awakened by gunshots and a military band that was playing music as Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his men rode into the camp. When the shooting was over, 29 people were dead, this time it was 11 men, 12 women, and six children. Among the dead were Chief Black Kettle, who had always advocated making peace with the white settlers, and also White Buffalo Woman’s brother, who was also a chief. His name was Little Rock, and he had been shot in the forehead while he was standing in front of his sister, White Buffalo Woman, and another sister of theirs, and some children. He was blocking them with his body and was shot in the head. White Buffalo Woman’s mother was taken as a prisoner of war because they were on the riverbank, that’s where they were camped, and she was too old to be able to scramble up the riverbank to safety, and so she was captured.

as soon as the people fight back, then the colonizer accuses the victims of causing the violence

Many, many other horrific things happened. For example, in 1878, when they got to Oklahoma to the reservation, the conditions were terrible. Some of the leaders made the decision to take their people back north, they wanted to go back up to Montana. And 297 Cheyenne began the march with the group split into two bands, one was led by Little Wolf and the other by Morningstar, who is also called Dull Knife. Morning Star’s band got caught and sent to Fort Robinson in Nebraska. It was the dead of winter, and the soldiers at Fort Robinson told the Cheyenne people that if they didn’t go back to the reservation in Oklahoma, they wouldn’t give them food, water, or heat. And people were scraping ice off the windows to try to get something to drink. Many of them decided to try to escape from Fort Robinson, but in that escape attempt, 61 people were killed. The rest of the people eventually were allowed to settle at a nearby creek.

The next important date was in 1884, an executive order created the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Southeast Montana. The Oklahoma one had already been established and that was the one they were trying to escape from, but eventually most of them stayed there. And then 1884, which was later, was when the Northern Cheyenne people got a reservation and they were forced to vacate their traditional homes and head for the reservation, because then it would leave the rest of the land open for white settlement. They created this reservation basically for a land grab for the white settlers.

In 1887, it continued this process of diminishing their land base. In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act, or the Allotment Act, and that was where the government thought that the indigenous practice of communal land use was uncivilized so they took reservation land, which was supposed to be sovereign Indian land. It was already so tiny, already it had shrunk so much, but the government assigned each man, not each person, each man, a little plot of land where he was supposed to have a farm and to raise a patriarchal family. So, a man and a wife and his kids on a little plot, which is not the way they had lived before.

Then the point of this was after the Indians had been assigned their little allotments, then they’re like, “Yay, you got all of the land you need, you got your little plot,” and the government took the rest of the reservation land and sold it to white people. On the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation in Oklahoma, approximately 30,000 homesteaders rushed onto the reservation at noon after it was done, after they sold the land, rushed onto the reservation and by evening in that one day, the Cheyennes and Arapahos were a minority on what had formerly been their own reservation. I’m going to read one newspaper clip from the time, a newspaper called the El Reno Democrat described, “All at once the wild unsettled region of 4 million acres had been transferred from the land of the Aborigines and was claimed by the progressive Aryan, who centuries ago set the star of empire to the west, and following up every advantage now claimed the larger part of the civilized world.”

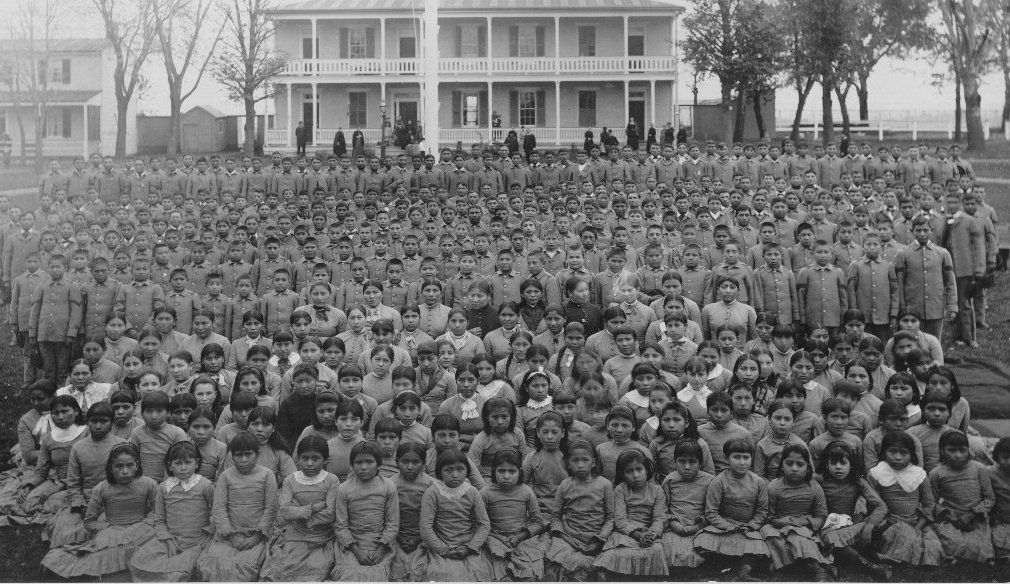

Okay, we’ve talked about literal genocide of white people killing Indians and outright stealing their land, and now we’re going to talk about cultural genocide. How did they do that? How did they shift to that? The answer is through education. At some point it became clear to the government that they were spending a ton of money on the Indian Wars, and they decided it was too expensive to kill them, and it would be better to make them assimilate. And that’s not an exaggeration, people literally wrote that it was too expensive to kill them, and so they should change tactics for that reason. Cultural genocide through education has happened to all Native American communities, but a little differently in each case. For the Cheyenne, it started in 1867 during this time where they were weary from being pursued over the plains and they were facing extinction from starvation. So when the U.S. government said that they would leave them alone if they sent their children to white schools, eventually they gave in. At first, the white schools were on their reservations and they were run by Quakers who came to the reservation to convert them to Christianity. And Mann writes that both Cheyennes and Arapahoes resisted, but that the Cheyennes were especially determined to not convert to Christianity. They were totally uncooperative, totally unwilling to go to church or go to schools. They resisted more than the Arapaho for some reason, in her telling of it.

Formal public education, not run by the Quakers, was initiated in January of 1871. And on the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation in Oklahoma, there was apparently a shack with a dirt floor and a dirt roof, and the parents sent their children to the shack to learn English, learn about Christianity, and gain some skills in math and just basic skills. But importantly, learning a trade that would enable them to function in white society. Mann writes that many Cheyenne families still refuse to send their kids to these white schools, and she said that her great-grandmother, White Buffalo Woman, had talked about Sweet Medicine’s warning that the strangers with the white skin and the hair on their faces would take away their children and erase their history, their beliefs and their language, leaving their children knowing nothing and taking everything from the people. So they saw this as a fulfillment of prophecy and they were not going to send their kids to have all of their heritage erased. So they were very, very resistant.

There are records from the time that say that sometimes the Indian agents, who were the white men that were assigned by the government to oversee the Native Americans in a certain area, sometimes the Indian agents were reporting back and being like, “I cannot get any Cheyennes to send their kids to school. They just wouldn’t do it.” And I have to include here one of the saddest passages I read in Mann’s book was this conversation between the Indian agent who was trying to get the families to send their kids to school. And he said, “You have to send your kids to school because soon the buffalo are going to be gone and you need school so that it can teach your kids how to live without the buffalo.” And what they replied, I guess the agent wrote, “They replied that they do not desire to live after the buffalo shall become extinct.”

In 1874, a man named John Seger became superintendent of the manual labor boarding school at the Cheyenne and Arapaho agency. This was a boarding school that was, I believe, on the grounds of the reservation. And Seger was great with kids and he really loved and respected the people, and he said, like, “You let me take your kids to school and then I’ll adopt your customs in exchange.” He would say, “I’ll make them white, but then you can make me Indian.” And in my opinion, I think it is great that he was kind and he did demonstrate love and respect genuinely for these people, but at the same time, it’s still part of a project that’s inexcusably morally wrong. His purpose was to win their trust so that he could erase their culture. And I think it’s easier to see the harm of this cultural genocide when the perpetrators are murderers, and it’s harder to see it if the perpetrators are friendly and respectful, but they’re still accomplishing the same ends. Also in her book, Mann quotes an Indian agent who wrote that one of the main purposes of putting Indian kids in white schools was to keep Native adults under control. A man named Agent Miles wrote, “There is no other means so effectual in holding restless Indians in check as to have their children in school.” Mann comments that it seems like the children were not being educated so much as they were being held hostage.

The next stage of education was the off-reservation boarding school. In the late 1870s, there were reports that were revealing that Native students weren’t learning to speak and read English at the rate that the government had hoped. So they kind of reasoned, well, the kids might be in school all day but then when they go home to their families at night, they’re not speaking English anymore. The term they used was “back to the blanket,” meaning back to their heritage culture, back to their heritage language, back to their family life. And so they were losing the civilization that they were gaining during the day at school. They decided they needed to get the kids off the reservation and do boarding schools far away so they couldn’t regress. So Cheyenne students were put on a train and they were sent to either the Syracuse Boarding School in New York or the Hampton Institute in Virginia.

Meanwhile, in the late 1870s, a little before this, several young Cheyenne men who were deemed rebellious had been captured and placed in shackles to be sent to prison. White Buffalo Woman was there when they were taken away. And it’s so awful to read the account and think of what it would feel like to watch your teenage brothers or your son or your nephews be placed in iron shackles like animals and hauled away, never to be seen again. She said there were no words to describe their grief and their rage as they watched that happen and couldn’t stop it. These young men were taken to a prison in Florida and they were under the care of a man named Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt. While supervising those prisoners in Florida, Lieutenant Pratt hatched the idea that he could take his military discipline and he could start a boarding school for these young men, and he was convinced that he could do it successfully.

That leads us to 1879, when Lieutenant Pratt founded the most famous boarding school in American history. It was called Carlisle Indian Industrial School, and it was a federally funded school that was in former army barracks in Pennsylvania. Many, many Native children and teens were sent to Carlisle from all over the country. At the time that it opened, there were 52 Cheyenne children enrolled there. That’s a long train ride to get to Pennsylvania. I highly recommend the book Education for Extinction by David Wallace. He talks in depth about Carlisle and even the accounts of the kids, who rode in a train who had never ridden in a train before and how terrifying that was to go that fast and they’re being taken away from their families. It’s a really, really important book to read also.

Interestingly, unlike, I would say, many white educators at the time, Pratt actually believed that Native people were not naturally inferior to white people. He wrote a couple of things about this. He wrote, “The Indian is born a blank, like all the rest of us. Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of a civilization, and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit.” Another thing he wrote was, “If all men are created equal, then why are Blacks segregated in separate regiments and Indians segregated on separate tribal reservations? Why aren’t all men given equal opportunities and allowed to assume their rightful place in society?” So, race was really meaningless in his mind. He wasn’t as racist technically as many Americans were at the time. However, Pratt was also the one who uttered probably the most famous phrase about Indian education: “Kill the Indian, save the man.” His goal was to absolutely obliterate every ounce of Native culture in the students so that they would completely leave behind their heritage and totally assimilate into the white world. I guess he was less racist because he believed they could do that, but it was just so incredibly prejudiced and still racist, I guess it’s culturalist or something, that he just saw no value in the native culture and native way of living and just complete white supremacy of that the white culture was in every way superior.

When students entered Carlisle, what happened when they showed up, first of all, there were a bunch of white adults, teachers or administrators or people who were working there, and they took the children’s clothing and burned them. Just imagine being a child and how your clothes feel, the only thing that you’d brought from home, you probably got those clothes from your mom and dad or from your grandparents, and those were taken away. Then they cut the kids’ hair, which, in some of those kids’ cultural context, meant that someone had died. You only cut your hair if you were in deep, deep grief and mourning, so that’s traumatizing also. Then the kids were prohibited from speaking their native languages and they were commanded to only speak English. Most of these kids knew not one word of English, and they were physically punished if they spoke their native language in many, many cases.

The typical school day was divided into two large time blocks. In the morning, that was dedicated to academics: reading and writing English, some basic math. And then the afternoons were for the industrial arts, with boys being educated in farm work and in mechanics. Not mechanics like physics and engineering, but like tin smithing, iron smithing, blacksmithing, things like that. And teachers wrote about the need to discipline students harshly. One teacher’s journal said, “The most promising boys are those who have been severely disciplined.” Henrietta Mann points out how traumatizing this severe discipline would be for Cheyenne kids since their culture made no allowance whatsoever for harsh discipline and they did not use corporal punishment on their kids. So to be spanked or hit or whipped or slapped with a ruler was– it’s horrible to do that to any kid, but to a Cheyenne kid, they’d never experienced that before, and it was very, very, very damaging to them. There are so many accounts of kids experiencing excruciating homesickness as well as terrible physical illnesses with no family members to comfort them. As we know, many children died and many children ran away.

Carlisle school had 567 Cheyenne kids enrolled over the course of the year, out of the thousands that they taught. And like other boarding schools, like Haskell and Chiloco, which were some other boarding schools where Cheyenne kids, especially, were enrolled, the boys, again, were trained to work as farmers or in manufacturing. This is another really important point, because Pratt did say that there are no racial differences, everyone is equal. At the same time, these schools were not preparing kids to be doctors or lawyers or politicians or business owners. They were preparing them to function in their proper place in the social hierarchy, doing the farm work and the manufacturing work. And girls were trained to do cooking and cleaning and laundry, and then some arts and crafts. Again, things that you would do in a white person’s home in a patriarchal family, or as a servant in someone else’s home.

Students were also apprenticed out to white families during the summers, which was supposed to give them kind of like an internship opportunity to gain work experience and contacts. And in some rare cases that did work and it kind of benefited them, but they were never paid and mostly they were just doing menial tasks basically as exploited servant labor for these white families. They would just get a free worker for the summer, so it was mostly exploitative.

So, what happened to the kids who did graduate from Carlisle and other boarding schools? Some of the most devastating moments I read about in several of the books that I’ve read are accounts of these young people coming home to their families and despising their families because they’ve absorbed the racism that they were indoctrinated in at school. And then also when kids came back home to their communities from these schools, the boys were unable to find work as farmers or they had been taught to manufacture things that no one needed. They had no job. And the girls had been taught skills, again, like setting tables with tablecloths or doing ironing, skills that they would only need to do in white people’s homes, not in a teepee, not in their home. And so these students had been prepared for white life, but white people were never going to let them assimilate fully and take their jobs and marry their children. So thousands of Native teenagers and young adults fell into this tragic abyss, like this no man’s land, where they didn’t fit anywhere anymore, and they didn’t have the skills that they needed to be an adult in either society. That was one of the most tragic things that I had never thought of until this class, is that they were consigned to this no man’s land where they weren’t prepared to be adults anywhere.

One important note on boarding schools. It’s important to know that there was a very wide range of experiences. There were tons of these schools, from the East Coast to the West Coast, everywhere in between across the continent. Some teachers were very caring and nurturing, and some told the kids, “I’m your mom while you’re away from home,” which is problematic in itself that this white adult is like, “I’ll be your new mother,” but at least they were kind. But other teachers and administrators were horrifically abusive, and there are many, many accounts of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. It just depended which school you went to, what time period, who you got as your teachers. So there’s a wide, wide variety in people’s experiences.

Toward the end of the 19th century, some Cheyennes were in faraway boarding schools, but increasingly the government was realizing, again, all about the money, that it was too expensive to fund schools at the federal level. And also, it wasn’t working. So, get this: at Carlisle there were 10,500 students that went through Carlisle while it was open. 10,500 students from 140 tribes during the 39 years that it operated. Of those 10,500 students, guess how many people graduated? 158. That’s a 1.5% graduation rate. So, in 1927, the Rockefeller Foundation funded research to see how the boarding schools were doing. And in 1928, a man named Lewis Meriam published the report of their findings, like, how are the boarding schools doing in terms of preparing these Native kids to be able to succeed in the world that we’ve created now here? And it was a scathing review. The Meriam Report said that the system was an absolute abomination. Americans should be ashamed. The kids were suffering with not enough food, not enough healthcare, and they weren’t even learning what they were supposed to be learning. Essentially, boarding schools had failed in every way.

One thing that sunk in as I was reading this is that the report was published in 1928, and some boarding schools kept operating until the 1980s. And they knew since 1928 that it wasn’t even working. Not only was it abusive, it wasn’t even working. And they kept functioning. Some of them were open for decades after that. In many cases, after the Meriam Report, the government said that they kind of reversed and said that kids should go to schools on the reservations again. And the overall attitude in the country was also shifting. In the 20th century, Congress passed a number of measures that sometimes emphasized tribal sovereignty and sometimes literally dissolved tribal sovereignty, saying, “You’re not a part of a tribe, you’re just a citizen of the United States like everywhere else.” But either way, what it did was it left tribal nations in the lurch to educate their kids without much help from the government. Many Native kids attended schools on the reservations from that point forward and then through the 20th century, sometimes on the reservations, sometimes not, and sometimes just public schools where these Native kids were a very small minority and encountered terrible racism and bullying both from the students and from their teachers. Native kids had the highest dropout rate in the country. In one district in Oklahoma in the 1970s, the dropout rate for Cheyenne kids was 90%. And Native American students still have the highest high school dropout rate in the country.

thousands of Native teenagers and young adults fell into this tragic abyss

But one chapter that I found really inspiring in Henrietta Mann’s book was where she talked about the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act in 1975, which gave some tribes a little bit of government money in reparations for all of the horrors that they had inflicted on them. And the tribes used this for scholarships for their students in their tribes. But Mann said, “We had already been taking education into our own hands for years,” even before they got this government money and before the Act that was like, “Here, we’ll help you with education.” Already before, in the 1960s, the Cheyenne-Arapaho tribe had seen that their kids were not thriving. They were really struggling, so they elected new young leaders to their governing body, which included two college graduates and two women. And Henrietta Mann was both. She was a woman and a college graduate. And of course, as we know, she went on to get a PhD.

In the early ‘70s, these new leaders had the goal, first of all, to close the communication gap between Indian children and white teachers in public schools. They envisioned an environment where Native kids would be centered and have a more healthy learning environment, so they wanted to hire Cheyenne instructors to teach history and language and to redesign standardized tests, including an IQ test that was based on what they called “Indian thought processes.” They did all of those things, and in 1972 they started a school called the Institute of the Southern Plains that taught classes in Cheyenne language and Cheyenne culture. They served nutritious food that was prepared by a professional cook, and actually that cook had received her training as a cook at a boarding school. So this was a really neat way to employ someone who had gotten trained in a skill, like, “Yes, we have a need for you.” So it was employing Native teachers and chefs. They had a basketball hoop, the court was dirt, but at least they had something. And then they had a Native-centered learning environment.

Tragically in the book, Mann predicted that the school would shut down, and indeed it did in 1977. But those elements that Mann described, a Native-centered curriculum that placed Native kids at the center instead of the margins, tribal adults as teachers, a history curriculum that told the truth about what had happened, a language curriculum that allowed students to speak or even learn, if they hadn’t been able to learn their native language at home as children, because if their parents hadn’t been able to speak it in boarding school, then their kids didn’t know it. But it allowed them to maybe revitalize their language in school. These are some of the things that Native kids need to thrive, as well as skills in English and math and everything that will allow them then to graduate high school, go to college, and then be able to participate and flourish in the outside culture that we live in now, but to be able to have the nurturing in all of those skills that they need.

In conclusion, as I’m looking at Cheyenne today, one interesting school that I found while researching is called St. Labre, L-A-B-R-E. It was founded in Montana in 1884, during that time when the reservation had been established for the Northern Cheyenne in Montana. And a lot of people had been displaced by all those homesteaders coming in, because that happened in Oklahoma and in Montana, that so many people were displaced when homesteaders came in. And this white guy, this former soldier in Montana, had seen all of these people who didn’t have homes and had nothing, so he contacted– I think he must have been Catholic because he contacted a Catholic bishop and said, “We need to help these people.” So Bishop Brondel recruited priests and nuns to work among the Northern Cheyenne in 1884. They had a log cabin, and it served as a residence, school, dormitory, and church. So, again, it’s just mixed and complicated, right? They’re teaching them Christianity, it’s white paternalism, and preparing them for white life, basically. They’re also taking them in and helping them when they see them unhoused and suffering in the cold.

But this school is still there and I was impressed by their website. They offer a lot of services for the community. They talk on the website with so much compassion about how the Native community struggles with alcoholism and drug use, you would understand why. I just think of if that had happened to my ancestors and then my own parents and then passed down to me. It’s just really, to me, very understandable why, if you had a way to kind of numb and dull the pain, it’s just easy to imagine that and have compassion for it. But anyway, St. Labre seems like a really interesting school that is emblematic of a lot of the elements in history, so that was an interesting one. I was also inspired to see in Montana a college called Chief Dull Knife College. Again, this man whose community called him Morning Star, but he was also named Chief Dull Knife. And there is a tribal college in Montana. In Oklahoma, for the Southern Cheyenne-Arapaho, there’s a college called Bacone College, B-A-C-O-N-E, and it’s been chartered by the Cheyenne-Arapaho tribe, I think in 2019, so it’s applied for status as a tribal college. These are just some examples that I found in my research about what’s going on for the Cheyenne right now, and trying to create environments for students that have those elements, that Henrietta Mann talked about in the 1970s, that kids need to be able to thrive.

It’s been a really, really meaningful project for me to learn about the peoples who first inhabited the land that I grew up on. I am a descendant of the settlers that colonized the Intermountain West, and I honestly feel just so sick in my soul about what my ancestors participated in and were never held accountable for. I think it’s extremely important to be honest about our history and to begin the process of learning what we can do to make it right in any way that we possibly can. So I would encourage anyone listening or watching to do three things. As a start, look up whose land you’re on. Go to native-land.ca. It’s also just really fascinating to look over the globe, it’s such a cool website. But start by learning the land that you grew up on and then where you live now. And second, look up the history of these peoples, look up the tribes that were the original inhabitants of the land you’re on, and then buy a book or read information online. There are so many websites. Go to the tribe’s page. Sometimes universities in your area will have tons of digitized, free information on the internet that you can learn about these peoples to educate yourself about the history.

And then third, find out what those tribes are doing today. What are their challenges? In their words, what are they saying is the best way to show support? And then maybe go to an event and show up and just listen, or do a lot of reading about what people are saying right now and what’s most helpful. That’s my advice. So I’m going be doing this for a long, long time, so if you have comments, please send me comments. If you’re watching on YouTube, you can drop your comments below, or if you’re listening on the podcast, then email me at breakingdownpatriarchy@gmail.com. And I’m excited to have everyone along on board in this process. Thanks for joining and see you next time on Breaking Down Patriarchy.

Go to native-land.ca

you can type in a city and state or a zip code and see whose land it is

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!