“we all had ancestors who lived in harmony with the land”

Amy is joined by Osprey Orielle Lake, author of The Story is in Our Bones: How Worldviews and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis, to confront the damage that patriarchy and endless economic growth have caused to our planet, discuss the realities of climate disaster, and talk about the ways we can still save our living world.

Our Guest

Osprey Orielle Lake

Osprey Orielle Lake is the founder and executive director of the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, or WECAN. She works internationally with grassroots, BIPOC, and Indigenous leaders, policymakers, and diverse coalitions to build climate justice, resilient communities, and a just transition to a decentralized, democratized, clean energy future. She sits on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature and on the steering committee for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. Osprey’s writing about climate justice, relationships with nature, women in leadership, and other topics has been featured in The Guardian, Earth Island Journal, The Ecologist, Ms. Magazine, and many other publications. She’s the author of the award winning books Uprisings for the Earth: Reconnecting Culture with Nature and The Story is in Our Bones: How Worldviews and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: When I think about my childhood in Seattle, Washington, the thing I remember most are the trees. My siblings and I had a forest in our backyard, and we would climb to the top of what we called the umbrella tree when we were sad or we needed to be alone to think. We made villages for slugs using leaves and petunia petals, picked and ate wild berries that we never even knew the names of, and we felt the peace and the joy and the freedom of growing up in nature. Perhaps because of these childhood experiences, there is still nothing that makes me happier and more whole and at peace than being in the wilderness. And it is deeply distressing to me to witness its destruction. On a broader scale, the thought that our beloved Earth is suffering from human-created pollution and climate change is a problem of existential proportions, and this catastrophe is actually linked to the system of patriarchy. I recently read a book called The Story is in Our Bones: How Worldviews and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis by Osprey Orielle Lake. I am so excited to discuss this topic and this book with Osprey today. Welcome, Osprey!

Osprey Orielle Lake: Thank you so much for inviting me. I’m really glad to be here with you.

AA: I’m so excited to talk with you. As usual, I’ll introduce you by reading your professional biography first, and then I’ll ask you to introduce yourself a little more personally to listeners afterward.

Osprey Orielle Lake is the founder and executive director of the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, or WECAN. She works internationally with grassroots, BIPOC, and Indigenous leaders, policymakers, and diverse coalitions to build climate justice, resilient communities, and a just transition to a decentralized, democratized, clean energy future. She sits on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature and on the steering committee for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. Osprey’s writing about climate justice, relationships with nature, women in leadership, and other topics has been featured in The Guardian, Earth Island Journal, The Ecologist, Ms. Magazine, and many other publications. She’s the author of the award winning book Uprisings for the Earth: Reconnecting Culture with Nature, as well as the book we’ll be discussing today, The Story is in Our Bones: How Worldviews and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis. That is a fascinating biography, Osprey, and I’d love to hear a little more about you, where you come from and some factors in your life that brought you to write this book and to do the work that you do in the world.

OOL: Well, thank you for that generous introduction. I think, like a lot of people, we have our different stories of how we’ve arrived at looking at this moment of great peril for the Earth and all of our communities, but also great promise. And it’s so strange in some ways to be living in these multiple realities where I just see so much harm to the Earth and endless destruction to people and communities as the climate crisis escalates, but also other crises that are social and economic and racially based, what many scholars are calling a poly-crisis, you know, where there are many multiple crises going on at the same time. We see that unfolding rapidly.

And at the same time, I’m so inspired by the work that I do at the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, and also so many coalitions and networks of people all over the world that we’re working with every day, where I see reforestation and food security networks and women leading incredible movements. And the way that we’re now able to have conversations around colonization and racism and patriarchy, where a decade ago we were having those conversations, but not so openly and publicly. It’s such an interesting time of seeing so much peril, but also so much promise.

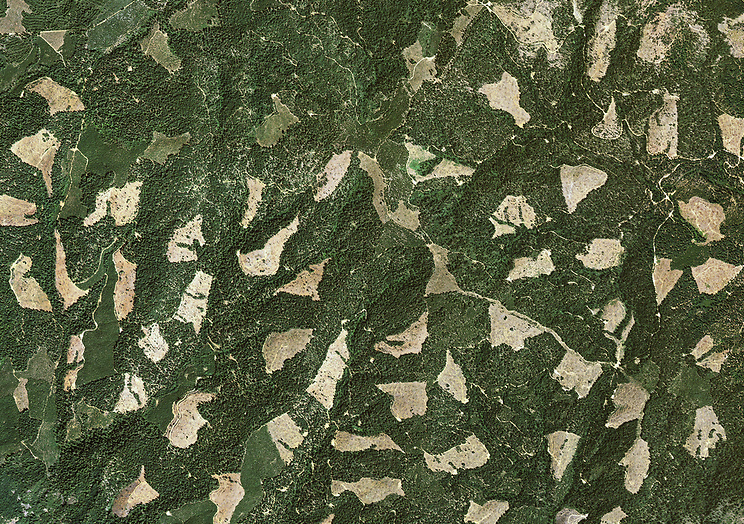

What really brings me here is my lived experience of things that I’ve experienced, the pains and hardships of life. What comes to mind right now as a childhood experience, I grew up in the town of Mendocino, which is about four hours North of San Francisco, and I was going through my own issues around a lot of trouble with my parents and childhood and looking and searching for healing. And I found a lot of healing in nature, which I think is true for many people, and the redwood trees became very, very important to me, walking in the redwood trees and really having them adopt me, if you will, as a relative and a place where I could go for comfort and well-being and learning. And I mention this because it’s also a time where there’s been huge devastation to those redwood forests, enormous amounts of logging. Only about 4 percent of the old growth forest is left, and there’s second growth forest, so that’s wonderful, but still, we’ve lost so much of our redwood forest.

I had an experience early on in my youth of seeing a very large clear-cut forest as far as my eyes could see, just like a battlefield of stumps, and it really broke my heart. And I realized that something is really remiss and has gone wrong in a society that would allow this kind of harm to so much beauty. I was a very young person at the time, but that’s sort of a beginning seed that all was not right with the world. And then there are many, many, many other experiences of wanting to do something to bring a positive outcome for humanity and for the land and for the web of life.

AA: Is this something that you studied in college and did as a young adult? When did you arrive at actually getting involved in organizations and learning how to make an impact in this area?

OOL: Yeah, my degrees are in the area of ecology and humanities, really, kind of a combination program that I put together. My first campaign actually was on the redwoods, when I was working to stop logging on a river called Big River, which is just south of the town of Mendocino. That’s kind of where I cut my teeth on my first campaign, so that started in high school. And how I arrived at the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network – we’re fast-forwarding many, many years – is that during the Obama administration, one of the annual climate talks that year was in Copenhagen. And there was a lot of hope from many of us that because Obama was in office, that there would be a transformative presence at the climate talks and that governments would really move forward in a different way that was much more bold and appropriate for the crisis at hand. And, as we all know, those climate talks did not create the kind of change that we need, that was commensurate with the crisis we’re facing.

It was right about then that I was actually walking in the redwoods, it’s interesting how the redwoods keep coming up, but I was walking in the redwood trees and I had this deep feeling, instead of quietude and peace, it was like feeling the screaming of the Earth, honestly. And I stopped everything I was doing and said, “I’m going to get involved in this climate crisis.” And when I did a lot of research, I found that, and at that time it wasn’t as visible as it is now, but that one of the big untold stories is the nexus between women’s leadership and climate solutions. That not only were women being impacted first and worst by the climate crisis due to global gender inequality, but also that they were leading solutions and were essential to making a difference. So that’s when I decided that I’m going to work on women and climate, and eventually WECAN was born.

AA: Hmm, I love that. That’s great. Well, since you mentioned it right now, I’ll ask you that first. How and why are women impacted first and worst by climate catastrophe?

OOL: Well, I’ll give a few examples. And I would just direct people to go to our website at wecaninternational.org because we have pages on statistics around women’s stories. And we have a database called Women Speak, and it has thousands of stories by and about women in different sectors around this issue. But in this moment, what I would share is that because of gender inequality, which is not innate, but is part of a social construct we’re engaged in right now, everything from women’s economy to their mobility, to their voice in politics, to their agency is diminished in patriarchal societies. And as a result, when climate crises happen or there are climate impacts, women are at a great disadvantage. Everything from knowing how to swim – which in some countries they are not allowed to learn how to do, which you might need to swim in a flood – to having a car, being able to drive, having the economy to have a car. All of these things about women’s daily life become very serious factors when there are climate disruptions. Women are also caring for their children and their elderly, so they’re not running out the door by themselves, they’ve got their families to attend to. They’re feeding their families in areas that are drought stricken, and so they also have to deal with all those kinds of needs of their families. There is so much more impact on women in these situations.

At the same time, it’s important to lift up the narrative that when we look at solutions, about 40 to 80 percent of all household food production in the Global South is done by women. And so much of what happens with these climate impacts depends on how people are going to survive in terms of food and water. Study after study shows that women are growing the food for their households. The UN has shown studies that when you’re in areas where you need to be collecting water, women are the ones who know about the water tables, they’re the ones monitoring the water, they’re the ones collecting the water, and if you don’t involve them in these water programs, the programs don’t even work. So we really need to continue to have this lens of bringing forward women’s leadership and a feminist analysis, because often different foundations or government policies will put men in charge of these programs and they don’t work. You have to have women at the table and in charge.

something is really remiss and has gone wrong in a society that would allow this kind of harm to so much beauty

I’ll give one stat that I think is really interesting, and I presented this at the Scenarios Forum, which is a forum that feeds the IPCC reports. A study shows that with just a one unit increase in something called the women’s political empowerment index, which is basically an index people do to study a country’s relationship with the empowerment of women – as an example, are women in political office? How are their economies being developed? Do they have more agency or not? How are they involved in society? With just a one unit increase in the women’s political empowerment index, we see an 11.51 percent decrease in carbon emissions, which is huge. It’s hard to get anything up over 10 percent that decreases carbon emissions. And definitely the climate crisis is not only about carbon emission reductions, however, it’s a really powerful indicator to see what happens when women have power, and what happens with environmental policies and care for their communities and the transformation of local economies. And I would just close by saying that we can look very clearly, since we’ve all recently come out of the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, there are a lot of stories that came out and it was shown that countries that were led by women did far better with their populations navigating the COVID-19 pandemic than their male counterparts. I think there’s a lot to be said about women’s leadership. And it’s not about putting men down, it’s about lifting women up and creating egalitarian societies. We’ve got to get women front and center at this point, and I think it’s really key that we do that.

AA: Hear, hear. You’re a great match for this podcast, because that’s something that we talk about constantly, that the goal is egalitarianism. The goal is the involvement of the whole human family working together to solve problems. So yes, it’s excellent. Okay, let’s back up a little bit. I want to back up in terms of the organization of the book and set the stage with a broad and big concept that you open the book with, and that’s worldviews. In the first place, before we even talk about the nitty gritty of policy, there’s this foundational aspect of how do we even see the world and our place in it as humans? The first chapter of your book is titled ‘Worldviews Are a Portal’. What are some examples of various worldviews and what are the implications of those worldviews?

OOL: Thank you for asking that question. I so enjoyed writing this book because WECAN is very involved on a day-to-day basis with protecting forests, reforestation projects, stopping fossil fuel pipelines, going to the UN climate talks, and bringing delegations of frontline women. So we have this very hands on, tangible work that we do every day. And at the same time, I wanted to take a moment with this book to go upstream and look at how we got into the mess we’re in, to put it simply. Because my experience, and I know from talking to a lot of people, is that it’s really hard to heal something when you don’t name it. It’s sort of like when you go to the doctor if you’re not well, they can’t just start prescribing things. They’re going to diagnose and research and analyze what is going on. So the book is really looking at, okay, how do we look at root causes and understand where these ideas came from that led to the moment we’re in?

When I’m talking about things like colonization and racism and patriarchy and the endless economic growth system, this extractive economy, all these things that we’re experiencing that are oppressive, dangerous, destructive systems, they didn’t just appear. And they’re, to me, not just human nature. They are something that humans are doing now. They’re the current social construct we’re in, but it’s not innate. This is not all who we are. So, how did we get here? Looking at worldviews allows us to go upstream and have a very different conversation so we can look at root causes and look at how we’re going to transform where we are now, but we have to be able to know what those are.

As an example, I make a distinction between the dominant culture in our worldviews versus, as an example, indigenous peoples or land-based peoples, or even ancient societies that were pre-colonial and pre-patriarchal societies that we all come from. So that we’re not sort of just like, “Gee, we’re in modern society and this is who we are. We’re just bad people, this is us.” I think we need to look at this from a historical lens, both to learn and to transform, but also to find good heart and good spirit of who we are, as a part of the web of life as a species on this planet that can be life-enhancing. So, some of the worldviews that we’re looking at are this idea of dominion over nature. Humans have dominion over nature. How did that happen? What is that worldview coming from? Or men having dominion over women or that there have to be binaries and there’s no room for gender diversity. Or the fact of white supremacy. How is it that white people are the chosen, more important people than everyone else? I mean, these are all hierarchical, patriarchal constructs that are quite dangerous. And they’re worldviews that are part of mostly Western society, that we really need to dismantle, compost in the compost pile, and transform, because they’re not working for anyone except for the wealthy elite. And that is simply not working.

So, it’s looking at those things, but also then exploring what healthy worldviews are, and really looking at these ideas that come from indigenous peoples around reciprocity with the land. How do we have an animate cosmology and how do we see the Earth is alive? Because we would treat the Earth and each other very differently if we had that respect and understanding that we’re here as part and particle of nature, not above nature. So, also looking at that, but also, as I was mentioning before, giving us the opportunity to have a larger historical lens so that we can look at our own ancestry in pre-patriarchal ways and pre-colonial times when we all had ancestors who lived in harmony with the land. And I’m not saying it was some past utopia. People had struggles, people have never been perfect, but I’m talking about the overall fact of a respect for each other and the land that we maintained. And how do we retrace those ancestries and reconstruct them and reclaim them today? This is sort of this idea of how we get into a worldview analysis that helps us remember our place in the Earth lineage and the larger arc of our presence here on the planet.

I think it’s a very healthy thing that we look at how we construct our world. What are our codes of conduct? What are ethics? Where did they come from? What are our assumptions and beliefs about how humanity has organized itself? And we can see this playing out in what is going on in Gaza and Israel right now, what is going on in Sudan, what is going on in the Democratic Republic of Congo, all of these extraction ideas and colonization ideas and struggles around belonging and identity. And really going back into a place, the story in our bones, about our place on the land that we do belong. And how do we reconnect? Because I think this deep sense of orphanage from the living Earth is not the only reason, but it’s absolutely central to the violence and harms we’re experiencing now. Because when you don’t feel that you belong and you don’t feel that you’re part of your community and the Earth, it generates unhealthy constructs that can lead to violence and to over-consumerism and all these things to make up for the fact of not belonging and not feeling part of the Earth and our communities.

AA: Yeah, I do love the title of the book, The Story is in Our Bones, because it is comforting and I think gives a sense of optimism because this can be such a depressing topic. We can feel kind of that existential dread, like, “Well, it’s too late for us,” and it can be really, really discouraging. I like that the title does allude to what you just talked about, that this is something that we all carry inside of us, a past in our own lineage. Like you’re saying, even if we come from Europe, going back before patriarchy, going back before the industrial revolution, even something that recent, even to more pastoral and more harmonious living with the Earth, we can all kind of tap into something that’s healthier. We can learn from and should learn from and honor other ancestral stories and traditions, but we don’t need to appropriate or go to somebody else’s stories for inspiration. It’s in all of our past. I like that you point that out. Are there any origin stories that you want to highlight that you share in the book or that you find particularly inspiring?

OOL: Yes, absolutely. And I wanted to comment, it’s an interesting thing and I’m glad you brought up the whole point about indigenous peoples and not appropriating information, which I think is absolutely key. As the dominant society, we’ve done plenty of extracting and we need to stop that. I think it’s a lot about researching our own ancestries, collecting those stories, learning about our food traditions, our ancient songs, getting our hands in the garden, and that direct experience and other ways of knowing. But also I do want to highlight that 80 percent of all the biodiversity left on earth is in the stewardship, in the lands and hands of indigenous people. So, simultaneously, while we’re on this journey of healing ourselves and the dominant culture, I think it’s also important to learn from indigenous people in a respectful, not extractive manner, because they are custodians of traditional ecological knowledge that we need to learn from right now. And most of us are living on stolen land. How do we actually create reparations and respect for indigenous peoples and support their calls for land back, support their calls for indigenous rights, and respect for their knowledge system?

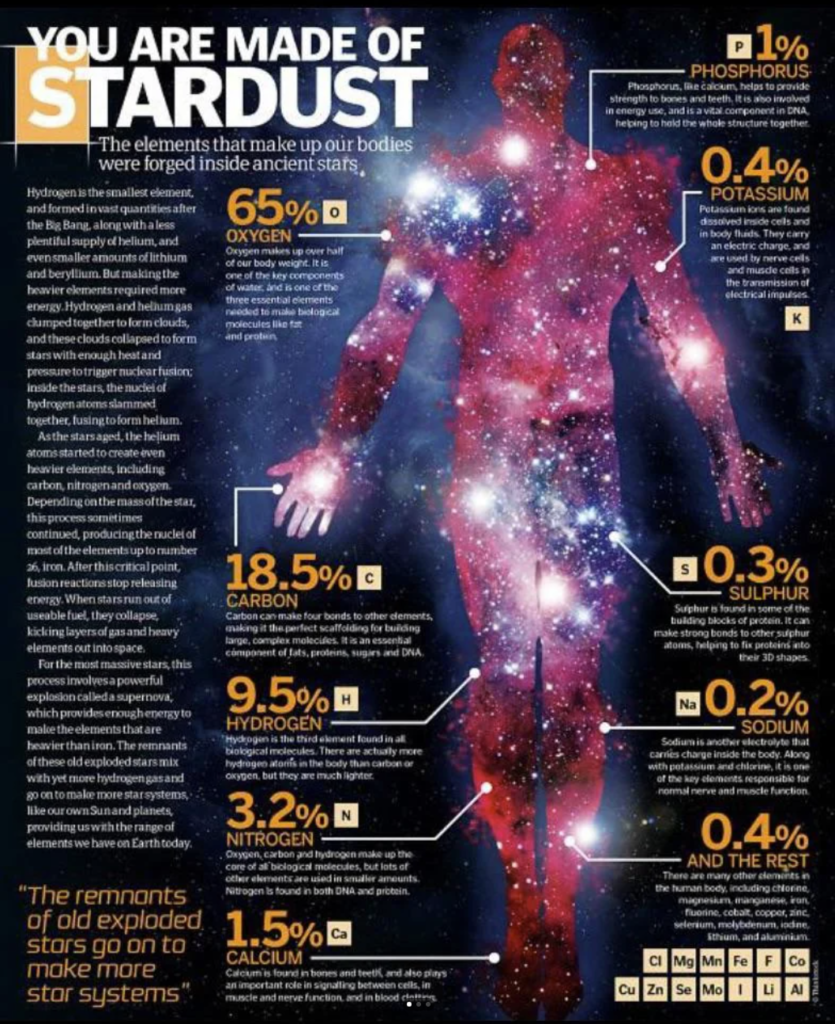

I feel like we’re sort of in a dance of weaving where we live and understanding the indigenous people where we live, learning who they are and lifting up their leadership, while simultaneously doing this other work. They sort of need to go on at the same time. So I’m really glad that you surfaced that. And in terms of the origin stories, one of the things that is something I focused on at the beginning of the book is actually getting us really connected to the Earth by remembering that we all come from the elements of what the Earth is made of. So in essence, we know when we look at the scientific evolution of our planet and the birth of our solar system, we all learned this in grammar school at some point, that there was the birth of the Earth and the stars and how literally through the process of what happens with the stars, these elements came to the Earth. And from that, we see the beginning of the first organisms. I won’t go on and on. All the things that we learned about single cell organisms developing into more and more developed species.

And why I mention this is because it is a way of remembering that the story is in our bones. We all literally come from the stars. We literally come from all the elements and components of the Earth. We’re part of this evolutionary story. We’re part of this Earth lineage and we never talk about it unless you’re in grammar school. It hardly ever comes up in conversation, yet it’s an essential origin story. It’s an essential part of who we are. So, again, this idea of how we regenerate belonging and confidence in ourselves and inner place of well-being and feeling ourselves as part of this animate cosmology has a lot to do with remembering our origins that we are literally nature. Not metaphorically, we are literally nature. That literally the forests and the mountains and the waters in our bodies are our relatives. They are our ancestors. We literally come from plants and animals. And that worldview shift is gigantic when we actually move it from an intellectual concept into our bodies, where we’re really remembering that from our heart and our spirit and our emotions and our mind that, oh my goodness, I’m part of this magnificent evolutionary pattern that has occurred on this planet. It’s such a gift.

And how do we actually embody that on a daily basis and make it part of our norm? I’ve been very, very honored to have a lot of indigenous mentors throughout my life, but one thing that has really touched me is learning how a lot of indigenous peoples, and I’m sure my own ancestors, if I’ve learned some about their origin stories, but this idea that whether it’s on an annual basis or frequently, having these ceremonies and rituals where you walk through the creation story, you tell it again and you enact it again. And people think it’s some primitive thing or some mythological metaphor. No, it’s actually bringing your whole society and culture and your community, bringing yourselves present into this moment, who we are in creation, and remembering that as a daily activity. And I would even go so far as to say, as I’ve studied this more, that I actually think it’s a political action. Because how can we have good politics or govern properly if we don’t even consider ourselves part of the animate living Earth and feel separate? It makes no sense. I think this is also really key to how we need to move forward.

AA: That’s so beautiful. And you kind of took me by surprise a little bit when I asked about origin stories. I guess I expected to hear a particular tradition or a particular, you know, myth or religious story, and you took us to science instead. I’ve never heard such a beautiful merging and I guess realization that it’s one in the same. The oneness is what we learn in science classes, but that origin story does have this spiritual resonance and this psychological and emotional resonance. And then, like you just explained, it has political impact too. But just remembering that we’re all on this rock in space together, right? This is our home. This is our common home. So merging all of those things into one common origin human stories was really beautiful and powerful. Thank you.

Another question I have for you is this: on the podcast here at Breaking Down Patriarchy we’ve talked a lot about how white supremacy and homophobia intersect with patriarchy, but we’ve talked a lot less about patriarchy and the way that that has influenced our treatment of the Earth and how it’s impacted our environment. Can you talk about those structures? I know we talked about that a little bit a few minutes ago, but can you dig into that a little bit more?

OOL: Sure. And I will give a few nuggets, but it is actually a giant topic.

AA: It is.

Not metaphorically, we are literally nature…literally the forests and the mountains and the waters in our bodies are our relatives

OOL: We get into it in depth and my books all pull on a few nuggets, because it is so intersectional as a topic, so I’m really glad that you asked the question. I’ll begin by saying that the rise of the patriarchy was relatively recent in regard to the arc of humans being on Earth. We were egalitarian societies for the most part. There were goddesses and gods and matriarchal societies, which are not, as you probably have talked about on your podcast before, matriarchal societies are not mirrors of patriarchal societies, meaning that women are in charge and women at the top of a hierarchy. They’re egalitarian societies, unlike how we typically defined patriarchy. And why this matters is because when you see the rise of the patriarchy, you also see the rise of this idea of one male God and monotheism. There wasn’t monotheism before. Everyone saw, as we were talking earlier, the Earth as animate, the stones are alive, the rivers are alive, we’re all part of the great Earth Mother, everything is alive and we’re part of that web of life.

And with the rise of patriarchy, we now have this distant male God who’s no longer in the stones and the rivers and the land. He’s up somewhere else and now not part of our embodied experience. Right there you have an immediate separation from nature, and the minute you’re separate from something, there’s the component of othering. And as soon as we have othering, we can then have dominion over, or hierarchy over. So this idea of this one male God figure, and this hierarchy and dominion over, all adds into the separation from nature narrative, which has been a very dangerous course that humanity has gone on, that we really need to remedy immediately and heal. So this dominance and control over nature really is part of the patriarchal project. And also, hierarchy and dualism where you see nature versus culture and white people and people of color, all these binaries also come out of this ideology of patriarchy. And also I would say the rise of the extractive economy, because now we have this dominion and the land is here and nature is here for us to take and take and take from. So you’re asking, you know, how does this impact nature? What we’re taking and taking and taking from nature now, because we are more important, we’re on the top of the hierarchy and nature is below us. And instead of us being in a circle with nature, and nature as our relative, now we have this dominion over nature to use and be there just for our use. The reciprocal relationship with the land has been diminished. And I would also say, in terms of feminist values, indigenous peoples and their view of reciprocity and living in relationship is also greatly diminished with the patriarchy, and that means their traditional ecological knowledge. So now that’s not important. And the academic male sciences are all, you know, Western science is now more important than all this traditional ecological knowledge, which actually teaches us how to live with the land. These are all different ways that the patriarchy has really harmed our relationship with nature. I would also say the understanding of the goddesses. We need to bring back our goddesses, we need to bring back our healthy gods. It’s not just that the gods are bad, but we need to bring back that balance of the healthy goddesses and gods and that sense of the living Earth and that equity and celebration of every aspect of nature and life.

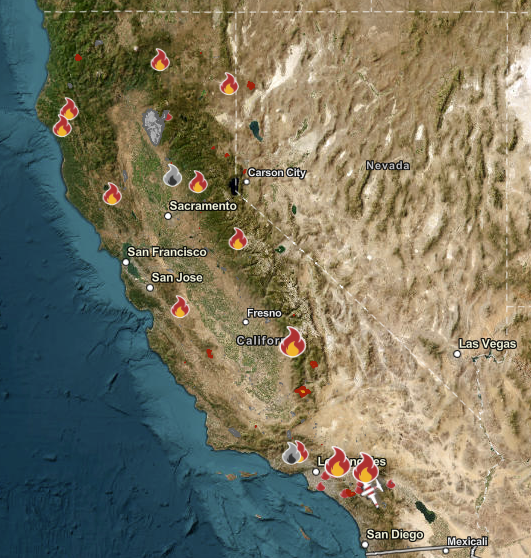

AA: One thing that came to mind as you were talking was how you open the book, as I recall, so correct me if I’m wrong, but I think in the introduction you talk about the wildfires in Northern California. And that hit me really hard too. My family lived in Northern California at the time, too, and there’s really no way to describe, I think you would agree, the grief and the horror that you feel when the forests that you love are burning. It was so interesting for our family to learn more, as you do when you live in Northern California, about overgrowth and the indigenous ways of using fire to manage the landscape. And that when Europeans came and colonized, they thought they knew better and they stopped doing controlled burns and controlled fires like the indigenous stewards of the land had done since time immemorial, and it creates tinderboxes and can create the conditions where then absolute destruction happens. And that’s just one example that comes to mind, the knowledge that’s lost when a white supremacist, patriarchal culture comes in. And the image that you recalled from your childhood too, of clear cutting forests and then doing farming that’s not sustainable. The whole thing doesn’t even work long-term. It’s not only harmful for the people, just the devastation of the Native peoples who have lived there, but also it doesn’t even work.

OOL: No, no. It’s really important. Yeah, thank you for pointing that out. I still have reactions to thinking about that fire, because people died, we were all locked in our homes. I remember waking up in the morning and the sky was black-orange at noon. I mean, it was black, but with this weird orange tinge, and your mind says, “I’m in an apocalypse. I’m in an apocalypse. This is happening.” And it’s terrifying. And I’m sorry to say, but we’re probably going to see more of that, not just in California, but all over the world. There are many, many, many blazes as we speak right now in Canada, and it’s not even the fire season. It’s way before their fire season. I think that the earth is reflecting back to us our behavior, and we are seeing Mother Earth shaking and moving and rolling and changing her climate to balance herself. And it’s hard. I don’t think we should shy away from saying that. I mean, I do think that we can turn these things around. I am an optimist in the sense that we could act to really bring down the global temperature. Scientists have shown us how to do that, but we need to do it at speed and scale like we’ve never seen before. And at the same time, I think it’s important to realize that we need to prepare ourselves for hard times. I think it’s important to just say it, even though it’s hard to look at it. We need to look at it.

AA: Yeah. Well, let’s talk more about that. I’d love for you to talk about some of the things that are going on in the world right now in terms of ecological destruction and climate change. Maybe talk a little bit about the grim realities that we’re experiencing and looking at, and then we’ll move into some of the things that we can do to make it better.

OOL: Yeah, absolutely. There’s so much that could be said, from the mass extinction of species that are going on every day, the litany is quite long. What I would focus on right now, because I think people are aware that we are seeing massive fires, massive flooding and droughts, I mean, it’s climate chaos. And different regions are being impacted in different ways. I think the thing that we need to realize that is also coming from more of feminist and intersectional lens is who’s being impacted the most. We talked about women, but we also need to look at Black and Brown and Indigenous communities and people living in the Global South. Because what happens when these disasters come is that low-income communities and Indigenous, Black, and Brown communities are suffering the worst because of white supremacy and because of patriarchy and because of things that we’re talking about. These systems of oppression have a real-time impact. And of course, the climate crisis and environmental degradation are going to impact everyone. There’s no place to go be safe, even if you think you’re going to go make a bunker somewhere. Where are you going to get your food? How is the water going to last? There’s no place that’s going to be safe. Everyone is going to be impacted, but to different degrees. It’s not even.

And we need to look at that and really address that and have what we like to call climate justice. There needs to be a climate justice approach and analysis of how we’re going to look at the harms and how we look at solutions, how we do at the UN climate talks. At the COP27 in Egypt we were able to define a loss and damage fund so that those being harmed the worst, who did the least to create the climate crisis and put the least amount of carbon emissions in the atmosphere, those communities are cared for. There’s this loss and damage fund. Of course it needs a lot of work, and governments are not following through with funds going into that fund. But nevertheless, we need to fight for things where there’s more equity in how the world experiences a climate crisis as it comes, climate disruptions and climate disasters. I think it’s important to look at it very holistically and prepare ourselves and ensure that those who are not from wealthy countries, who did not cause the same harm, that there really is a way to lift all boats at the same time, if you will, and care for all the different communities.

Lastly, I would say, it is really frustrating because a lot of scientists are, I think The Guardian even just a few days ago came out with an article about how a lot of scientists are saying, and we know this from going to the UN climate talks every year, what governments have decided upon still bakes in about a 2.53 degree rise in global temperature when we need to be at 1.5. We’ve bounced over and we need to get it back down. It is really scary because much more radical change is needed, much more transformative leadership is needed at a time when the world is not in good governance right now. We’re not, in many countries around the world, including here in the United States. There are so many problems around addressing the climate crisis and other social ills. I think that we have to really push our governments much harder than we are, and this is why we have to have a systems approach because it means tugging at the economy. We have a fossil fuel economy. We have geopolitical factors. All of these things are very complex and tied into each other. But what I do know is that we can approach this with our heart and our spirit and our intellect and every part of ourselves and not give up. And continue to understand that humans have done remarkable things under enormously difficult situations.

That’s what I really hold onto, is that there is an opportunity for us here. As I mentioned, it’s kind of a moment of promise or peril, and the promise is for a great transformation in the human project right now. We have to hold that and center that and create the reality that we want, and that means a lot of hard work. I don’t mean it in some fantasy way, I mean rolling up our sleeves and getting to work. I love the saying that “hope is a verb with its sleeves rolled up.” And for me, this is it. We all need to engage. No one can be on the sidelines, and we all need to do our part in this unfolding story. We actually do have an opportunity for change, but we have to engage.

AA: Yeah, that’s wonderful and inspiring. I’m going to push you on the details, because one conversation that comes up for me, among friends or even in our family– One thing I will say too, that gives me hope and is really heartwarming for me, is that raising my kids in Northern California, in the Bay Area, they were learning from the time they were in preschool about living responsibly and taking care of the Earth. They are absolutely up in arms and livid when people don’t compost and don’t put things in the right bins, and they don’t want to waste food. It is so beautiful for me to see my kids being raised in their public schools that way. But I’ll say one thing that we talk about sometimes is like, okay, we recycle and we drive electric cars, actually, we hardly eat any beef. Anything that we learn about that we’re like, “Okay, this is making an impact,” we really try to implement in our family. My kids also, like I was sending them to school with lunches in Ziploc bags and they’re like, “Mother! No single-use plastic!” I’m like, “I grew up with Ziplocs, I never thought about it.” And I was grateful that they told us about it.

But I guess the hard thing that comes up is that sometimes I’ll read an article that’s like, “You realize that none of your recycling is actually getting recycled.” Or, you can live this way and never use a Ziploc bag, never use a plastic bag again, and it’s not even going to make a dent in it because it’s all of these huge corporations that are making most of the impact. And it sometimes, I think, makes people want to just throw their hands up and be like, “Well, what can I even do?” What can I do? I care a lot, but I don’t want to live in existential crisis mode and be terrified all the time when I don’t even know what I can do. So, what are some concrete things that we can do? And I recognize also, sorry, I’m being really long winded here, but I’m just processing it out loud. At the end of the day, we also have to live with integrity and live aligned with our values. And if everybody does that, then it will have a big impact. It’s still the right way to live, right? Whether or not it has a huge impact, to make those small changes at home. But my question for you is, what would you recommend that we do in our households, in our daily lives, and maybe some action items that we can do that could make even a bigger impact than just abstaining from Ziplocs?

OOL: Yeah, I think it’s a great question, and I’m really glad that you’re wrestling with it because we’re all wrestling with it. You’re certainly not alone. I kind of see it like an ecosystem and every part of the ecosystem being important. Let’s start with our home. It does matter how we live in our home, for all the beautiful, beautiful reasons that you said. And I love hearing about your children. I have had that experience too, with young people that we might do classes with, and, boy, if you make a mistake, which is good, they’ll tell you right away. The awareness factor is huge, and I absolutely love it. I think it’s because of the education that is being shared with them. Not everywhere, let’s face it, we’re in California and I do think things are different in California. I’m not saying people across the country aren’t doing great work or in other places in the world, but I feel very thankful for the kind of education that’s happening here.

And it matters because, one, I feel like it’s the education, but also the youth, I think they’re very aware that their very futures are on the line. So there’s a ferocity and responsibility around it that is literally coming from them wanting to survive and live, and we need to hear that urgency and that discipline that they’re carrying. I think that all those practices are good. One, because I think that if people do it collectively, as you mentioned, it does make a difference if everyone is doing it. And that means we need to do it and that one act is important collectively. Absolutely, it’s important when it’s done collectively. And not only is it an act, but it’s also a mindset about our relationship to the things around us. To stuff, to bags, to what we’re purchasing or not, and it can influence whether we’re consuming or not. Over-consumerism is huge, wasting food is huge. One of the biggest sources of pollution is food waste, so these are not small things. I definitely don’t think it’s small to make our homes a site of transformation, a site of action and transformative thinking. I think our home circles absolutely matter, and then sharing that with others. That’s sort of our home base situation, but no, I don’t think it’s enough.

The next ecosystem outreach would be to get involved in groups that are doing work that you’re interested in. I do think, and I know people say this a lot, but it’s because I think it’s true, which is to really take that time to think about what you’re passionate about. What do I love? What part of this ecosystem am I most interested in? Because that’s what we’ll have energy for. The things that we love are what we have energy for. So, finding your place, whether it’s reducing plastic garbage or whatever it happens to be fighting fossil fuel companies, or whatever it is that is someone’s interest area, dig in and do that. I don’t think it’s good for us to just be at home. And I’m not saying everybody has the capacity or privilege to do something beyond their home. I think that’s also really important to elevate. Some people are simply trying to feed their kids, and I don’t think in any way that more should be asked of them. I think that it’s unfair to be judging each other.

I think this is something we all need to take on. What can I do? What’s the most I can do with the resources I have and who I am and, you know, what our racial backgrounds are. All of that accounts for what we can contribute. I think also we need to refrain from all of this cancel culture and judging each other. I think definitely spurring each other on, I don’t mind calling out the fossil fuel industry or the mining companies or the wealthy elite. Go have at it with them. But I think that everyday people need to support each other in our collective activities and definitely get involved with groups who are taking action. Because we need more people to take action, more people caring, more people realizing that when we collect together, we have enormous power.

I definitely don’t think it’s small to make our homes a site of transformation, a site of action and transformative thinking.

And just to give some examples so it’s not so abstract, since we were talking about the UN climate talks, we’ve been going there for over a decade with frontline women and working with many, many other activists and leaders that go every year. And people are like, “Why are you going to the COP? It will never be resolved there. The climate crisis will never be resolved there.” And that’s true, it won’t be resolved there. But the fact is, governments are making decisions there. And if we’re not there, things would be far worse. The 1.5 degree guardrail was put into the Paris climate agreement. That happened because of the push of grassroots leaders and civil society, all of us being there demanding and having actions and protesting along with the climate vulnerable countries, that push from the inside from the climate vulnerable countries with civil society forced 1.5 degrees into the Paris climate agreement. It wasn’t there before. And that 1.5 degrees has been a huge leverage point for many of us doing advocacy work with financial institutions or with governments or corporations to demand that they adhere to the Paris climate agreement guardrail. That’s huge. That happened because of collective action or this loss and damage fund, which really forced a discussion on climate justice. Last year we had the climate talks in Dubai, and the conversation was supposed to be on a global stock take and civil society, and again, climate vulnerable countries demanded that we finally talk about ending fossil fuels. It wasn’t on the agenda and we forced it there. We didn’t get everything we wanted, but it’s now part of the conversation. So, my point being that there are collective actions that we all need to participate in, and that’s where we get our energy from. That’s what will give us hope. And it is also like a remedy for despair. Are we going to make everything perfect and have happy endings? I have no idea. But I know it’ll be a lot less bad and our children will have better opportunities with every small degree of global warming that we can stop and every tree we can save and every waterway protected. Anything we can save and protect is going to make the future better. I think that’s a stance that we can collect around.

AA: I agree. I can’t imagine anything that would be more of a unifying goal than just wanting to protect our children, the next generation of people who live on Earth. How it could be a partisan issue is beyond me. How could anyone disagree with that? I agree. Well, that’s very inspiring, Osprey. That really helps me to be optimistic and to remember, too, so many good things. Like you pointed out, critical, critical changes have been made in this world by people just working for it. And the naysayers will always say it can’t be done, but we as humans have done really incredible things. The arc of the moral universe has bent toward justice when we have chosen to make it.

OOL: Right, exactly. And just to share something from nature that is something that’s really inspired me, because, again, I’m not trying to paint a pretty picture that we’re not massive destroyers on this planet right now as the dominant society. But also, how do we look at ourselves as life-enhancing? Something that’s really excited me is that one of our projects is in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and we’ve been working there for about eight years with one of our coordinators, Neema Namadamu, who’s an amazing leader. We started doing reforestation work with her about eight or maybe even nine years ago in an area that, through slash and burn techniques, again, through colonization and through extractive economies and that whole history, destroyed these forest lands. And the Amazon rainforest, of course, is primary when we think about ecological integrity of the planet and an ecosystem that the whole world depends on. But right after the Amazon rainforest is the Congo basin and the forest there that must be protected.

We have now about one thousand women leaders who are reforesting these damaged lands, and 25 percent of the trees go back for the communities to use, and 75 percent of the trees are there to rewild the forest and heal it. And as a result of this, many years later and the trees that we’ve grown a lot, we’re not quite there yet, but an enormous amount of the population is no longer utilizing the old growth forest, which of course is the most important for biodiversity and carbon sequestration. So we’re protecting 1.6 million acres of old growth forest as the communities are using 25 percent of the trees that we’ve grown. And then we’re reforesting and rewilding this area. It’s just been so amazing to see this. It’s all women-led in a country that’s very patriarchal, and there’s been a lot of violence against women because of the wars that have happened there. It’s giving them safety, it’s giving them leadership, it’s giving them power.

The last part I wanted to say is that just in the last year and a half, which has really excited me, which we didn’t know and the foresters didn’t know what happened so quickly, is that when you reforest it brings back moisture, and the trees bring back rain and moisture to the land. Now the forest is reseeding herself, and there’s what we’re calling “wild nurseries” everywhere, where there are pockets of all the natural forest coming back all on its own in addition to our nurseries. So we’re seeing this incredible regeneration and this forest coming back, and I just wanted to share that because we’re talking eight years later, way faster than the scientists thought, we’re seeing this forest regenerate itself through this intervention of humans being life-enhancing. That kind of thing also brings me a lot of hope.

AA: Yeah, that’s incredibly heartening. I love that story. Thank you so much for sharing that. That’s beautiful. Well, is there anything else that you’d like to share with our listeners and viewers as a takeaway before we wrap up, Osprey?

OOL: Yeah, there are two things I’ll mention quickly because they’re very practical. In terms of movements that I’m really excited about are obviously women-led movements as a solution to climate change, indigenous rights as a solution to the climate crisis. And two particular campaigns that I’m also really excited about, one is called Rights of Nature. This idea that we need to recognize nature being a rights-bearing entity, that rivers have a right to thrive and grow and be healthy, forests have the right to grow and be healthy. Just like we have human rights, nature also needs rights. It’s a new governance system about how we can protect nature, and people can read about it in my book and look it up, Rights of Nature. I’m on the executive committee for the Global Alliance for Rights of Nature, so a lot of that is part of our work at WECAN. I’m also on the steering committee of something called the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, which is a mechanism to get countries to basically come off of fossil fuels, and how to create an agreement between all countries to end fossil fuels. It’s gaining a lot of momentum and it’s a very interesting initiative. I wanted to point out those two pieces of policy because I think it’s also important to think, how do we actually create these systems and policies and initiatives that can do what we want to do for the healthy and just world we’re looking forward to?

AA: Wonderful. Well, we’ll have all of those organizations in the show notes. And I also want to say, again, how much I recommend your book. Again, Osprey Orielle Lake is the author and our guest today, and the book is The Story is in Our Bones: How Worldviews and Climate Justice Can Remake a World in Crisis. I recommend also reading that book, because like you say, it goes into so much more depth than we were able to cover here on the episode today, and listeners and viewers can get a lot more wonderful ideas of how we can take action. Thank you again so much for being here today. I learned so much from you and I’m really grateful for the work you’re doing.

OOL: Thank you so much for having this show and inviting me. I really appreciate it. Thank you.

You have to have women at the table

and in charge.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!