“You’re not reinventing the wheel”

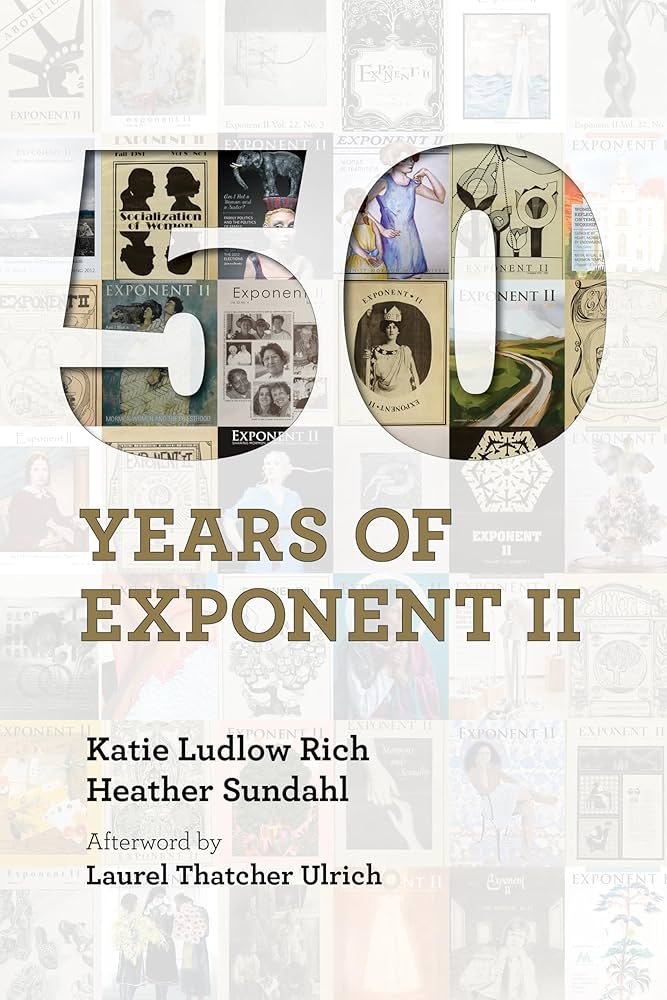

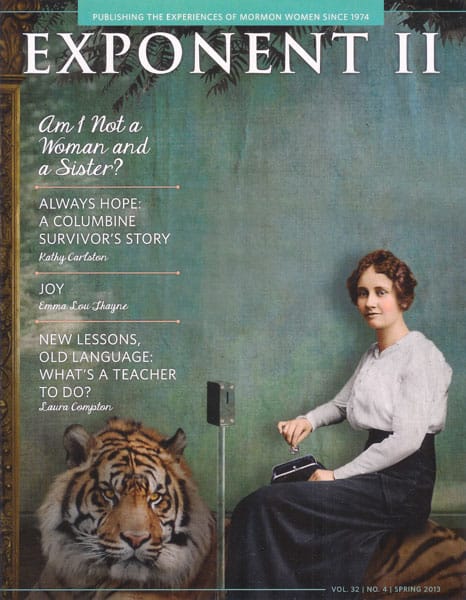

Amy is joined by Heather Sundahl & Katie Ludlow Rich of the Exponent II to discuss their book 50 Years of Exponent II, explore the history of this essential publication, and celebrate the history and future of Mormon feminism.

Our Guests

Heather Sundahl

Heather Sundahl believes in the power of stories. In the pursuit of this, she has volunteered with Exponent II for twenty-eight years. As a writer and editor, Heather works to amplify the voices of marginalized folks and has collected the oral histories of Batswana, South African, Native American, and queer Mormon women. She received an MA in English from BYU in 1994 and an MA in Marriage & Family Therapy from UVU in 2023. Heather currently works at a residential treatment center where she helps her teenage clients find narratives that promote growth and healing. She lives in Orem, Utah.

Katie Ludlow Rich

Katie Ludlow Rich is a writer and independent scholar of Mormon women’s history. Her work focuses on centering women’s voices and their agentive decisions even when functioning within a patriarchal tradition. She has a bachelor’s in history and a master’s in English, both from Brigham Young University. Her writing has appeared in Exponent II, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, The Journal of Mormon History, and The Salt Lake Tribune. She lives in Saratoga Springs, Utah.

The Discussion

AA: When I reflect on my personal mission to deconstruct patriarchy, I think a lot about a period of about 10 years of my life when I was really struggling. These were the years when the realities of being a young mother and homemaker were setting in. My mind and heart had always been devoted to the religion of my family and community, but my mind and heart had also always been devoted to a quest for objective truth and social justice. The conflict between my love for my faith and my lived experience of constant patriarchal injustice caused a mental and emotional upheaval for which I had no outlet, and in which I had very little companionship; only a handful of women, thank goodness for them, who felt equally anguished.

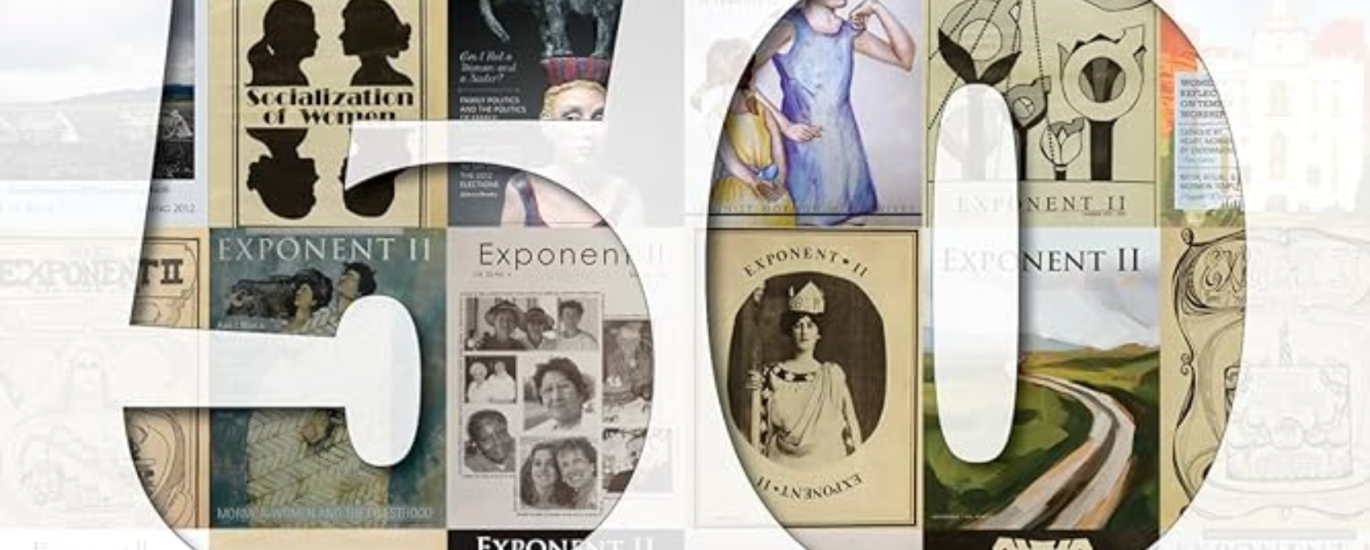

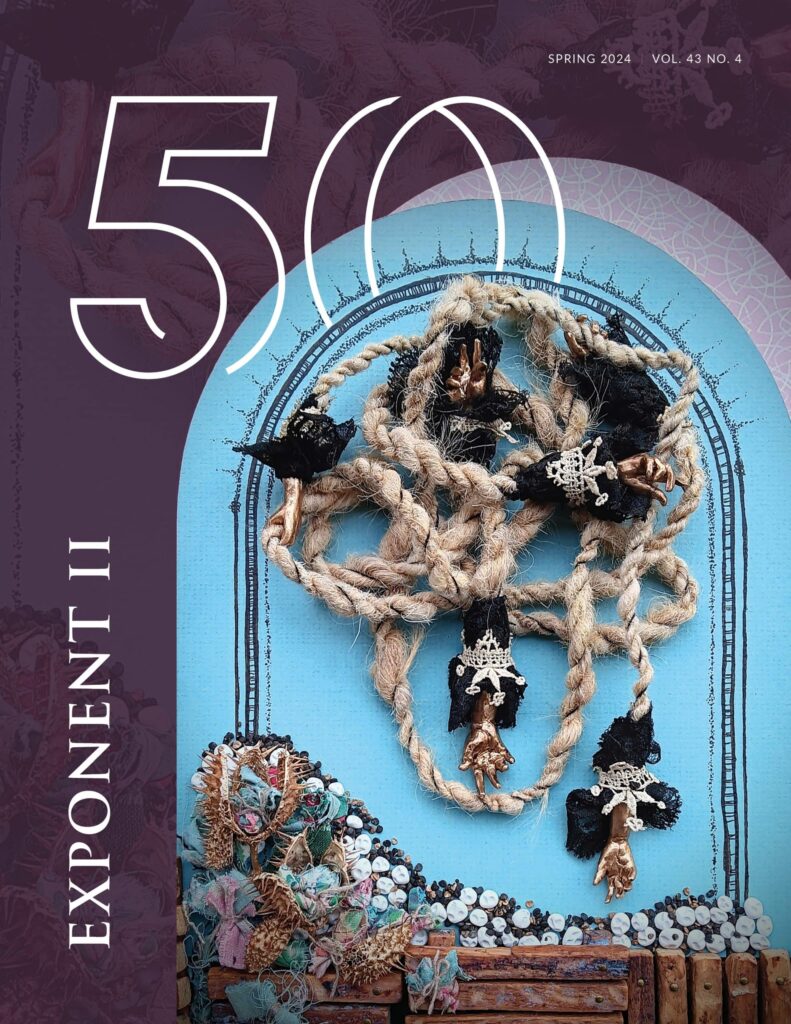

It was in this period of my life that I discovered a magazine called the Exponent II. It was a periodical for women in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to explore all the aspects of their lives. Including struggles, large and small, in stunning emotional and intellectual honesty. I immediately subscribed, and it became a life raft for me and, eventually, as I’ll talk about later, a launching pad for the work I do now. So today’s episode is dedicated to the Exponent II. And specifically, to a book that celebrates 50 years of the publication celebrating and supporting and nurturing LDS women.

The book is called 50 Years of Exponent II and its editors are Heather Sundahl and Katie Ludlow Rich who are joining me today. Welcome Heather and Katie, we are so happy to be here! I always start out the episodes with an introduction and by reading your professional bio. So I’ll do that first and then I’ll have you each introduce yourselves more personally after that.

Heather Sundahl believes in the power of stories. In pursuit of this, she has volunteered with Exponent II for 28 years. As a writer and editor, Heather works to amplify the voices of marginalized folks and has collected oral histories of Botswana, South Africa, Native American, and queer Mormon women. She received an MA in English from BYU in 1994 and an MA in Marriage and Family Therapy from UVU in 2023. Heather currently works at a residential treatment center where she helps her teenage clients find narratives that promote growth and healing. She lives in Orem, Utah.

Katie Ludlow Rich is a writer and independent scholar living in Saratoga Springs, Utah. Her work focuses on centering women’s voices and their agentive decisions, even when functioning within a patriarchal religious tradition. She has a bachelor’s in history and a Master’s in English, both from Brigham Young University. Her work has appeared in Exponent II, Dialogue: a journal of Mormon thought, and the Journal of Mormon History.

So again, welcome ladies. I’m so excited to hear all about Exponent II and all of the work that you’re doing, but I As I mentioned, I’d love to just start with a little bit of your personal histories. So maybe I’ll have you go first, Katie, and then Heather, you can follow. Just tell us a little bit about where you’re from and what the kind of forces were in your life that made you the person that you are today.

KR: I grew up in Modesto, California. And then came out to BYU for school and I was a history major and then had this year off where I worked at a law firm and then went back to school to get my master’s in English. And right before I started that master’s, I was a research assistant with Dr. Bill Hartley on the Mormon Trail. And so I spent that summer reading trail diaries. It’s kind of exploring women’s experiences within the early Church and the early Utah experience in a new way. And then as I graduated and became a stay-at-home mom—I have four kids—those stories just stayed with me and stayed with my interests and I kind of kept up on Mormon history stuff as new things came out.

And in 2019 decided I wanted to kind of pursue it more seriously, more professionally. And 2021 then became a really big year for me. So that was the year that I started as a blogger with exponent two. So in January of that year, and then in June of 2021, I attended and presented at the Mormon History Association conference for the first time.

And I was challenging the claim that Brigham Young disbanded the Relief Society in 1845. That was my project that I had been working on. And while there, I got to meet Heather Sundahl and Caroline Klein and Nancy Ross and these other extraordinary Exponent bloggers and leaders in the organization in person for the first time. But then also from across the courtyard, I saw Claudia Bushman and Richard Bushman, and I was way too intimidated to go introduce myself to them. I was like, I have nothing to say, but I was just amazed to kind of be in the presence of that founding editor of Exponent II and feeling this moment as a blogger for the organization and thought about how the 50 year anniversary was coming up. And how we should do something to kind of mark this significant moment, and maybe I can do something. But I was the new kid on the block, and I was both new to the field of Mormon history, new to the organization, and I couldn’t do a big project like this by myself. I needed a partner who had the relationships and experience and a track record of big projects. And that’s where Heather comes in.

Okay, take it away, Heather.

HS: I love it. Yeah, so I am also a California girl. I am from Southern California and also came to BYU just a few years before Katie and also got a master’s in English. So we’ve got a few parallels, a few things like really line up. And when I was at BYU, I got a master’s in English and I was working with Gloria Cronin and Cecilia Farr and Sue Lundquist and these were just really intersectional women before that was probably even a word. They really just opened my mind up, just gave labels to the stuff that I was seeing.

And you know, Amy, I’ve told you before the story about being a freshman at BYU and going to that big Sunday Night Fireside, and it was by a woman and I was so excited that we were going to hear from a woman and I show up and she’s like, “Women, we don’t need to become astronomers because we can sing Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star to our children.” And I just went back to my dorm and laughed until I cried. I was just like, Oh my gosh, is this what my life is relegated to? I felt like I didn’t have a choice. So these women really kind of introduced me to the world of choice. And Sue Lundquist with her Native American Studies really introduced me to the world of story and the power of story. And so I ended up writing my master’s thesis on story and how the way we tell stories can define and change our lives.

So a few years later, my husband and I moved to Belmont, Massachusetts, and I meet just this whole group of Exponent women who are so fabulous. And I just immediately feel at home like I’ve never felt at home before. And so I started mentally writing this book back in 1996, being in my twenties, kind of clueless, just observing them and just grabbing up every little piece of wisdom and interesting stuff that they had. And then over the years, I worked with Exponent, I sort of learned who came before, and then became involved with the people who came after, and I felt like I am part of this bridge generation who sort of knows both sides of this. And I even wrote an outline in a proposal at one point for a history book on Exponent, but the timing wasn’t right.

So I decided to go back to school. And then Katie reaches out to me like two weeks into my semester where I just started this two-year program in marriage and family therapy, and she just lays the whole thing out. And part of my head is like, Oh hell no. You don’t even know how to log into your account at UVU. Like, you are so old. You have to make the young ones…you have to promise to like write their papers for them if they will help you find where the articles are because you can’t figure it out. Like it is so intimidating. But my heart was like, Oh, hell yeah, I am all in. And I don’t even think I told you I had to think about it. I think I was like, Oh yes, yes, count me in. I don’t know how or when I’m going to do it, but count me in. I’m all for it. And it has just been a ride. It really has been a fantastic experience.

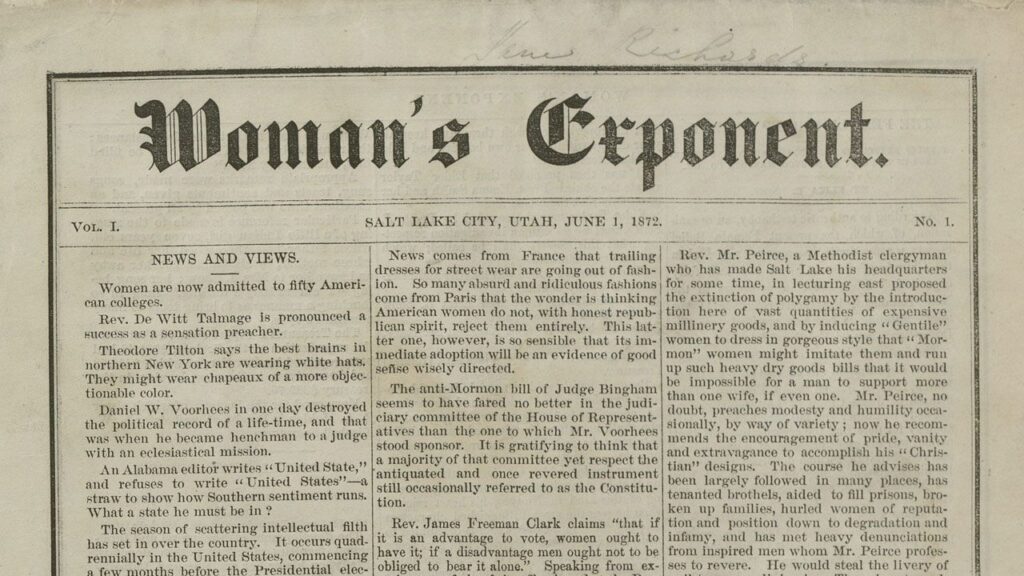

AA: Oh, that’s great. I love knowing that backstory. So as we kind of dive into the conversation, let’s back up and talk about the Exponent. And I’m guessing that a lot of listeners or viewers are familiar enough with the LDS Church and with LDS feminism, but some might not be, and won’t know even some of the kind of Mormon-y lingo. So if you can start by telling us about the original Woman’s Exponent, because you’re writing a book about the Exponent II, but what was the original Woman’s Exponent? Who wrote it and why was it significant?

KR: The original Woman’s Exponent was a Utah-based periodical that started in 1872 and continued till 1914. Lula Greene Richards, a niece of Brigham Young, was the founding editor and then after a few years it passed on to Emmeline Wells who was the editor for the next 40 years. And it had a lot of arguments for women’s rights and for suffrage as part of this larger state and national suffrage movement, alongside articles about housekeeping and articles printing Church leaders remarks at various meetings, and faith and women’s rights just side by side in the same paper. And it became really foundational as these women in the 1970s learned about it and got to learn pieces of that history.

But it continued until about 1914 when Emmeline Wells had become the General Relief Society president a few years before. And after being editor for decades, when she’s in this position of leadership, the Woman’s Exponent ends and the Relief Society Magazine begins. And so women continue to have this publication. It goes from this semi-formal publication, semi-connected to the Church, to a direct publication by the Church with the Relief Society Magazine. And that continued until 1970.

AA: Okay. So then why and when did it stop? And then what was the Church like for women in the years afterwards, after the Exponent was discontinued?

KR: Yeah. So it was discontinued in favor of that Relief Society Magazine. And initially in those next couple of decades, we’re in the progressive era and we have a lot happening. We have the Relief Society doing really huge projects. They had this huge wheat storage program and sold it for significant sums to the U.S. government during World War I. They became the first social workers in Utah and led the social work program. They had this huge maternity welfare work where they would have birthing kits in ward buildings that the Relief Societies would use to go help deliver babies. And they tracked legislation through the Relief Society Magazine, and they kept up on things and lobbied for women’s rights and for maternal health care and child health care and had hospitals and just had huge projects.

And then over kind of the long arc of the 20th century, we start to see the Relief Society’s autonomy and power rollback. One of those kind of key moments is in 1946 when Joseph Fielding Smith, who was a General Authority, discouraged women from giving ritual healings and giving blessings by the laying on of hands. And that statement from him to call the elders instead, makes it into the general relief society handbook and becomes this kind of landmark statement that really shifts the culture of women’s power and authority in significant ways. And what we see here is what makes it into handbooks and what becomes institutionalized. And when we’re in times of transition, we’re seeing women continue to lose power, lose autonomy, lose authority.

Then in the 1960s, the priesthood correlation program really kicks up. So the Church was globalizing at a massive rate at this point. And they had just incredible growth as they’re sending missionaries out throughout the world and they’re facing questions about how to manage programs and lessons and buildings and all of these things across the globe and want to streamline efforts. And so they do this through the priesthood correlation program, which for probably these male leaders is something that just makes sense; that we are going to make things uniform and make things more accessible. We’re going to make it easier for local congregations to have buildings. We’re going to have lesson plans so that people can have gospel teachings in their home and things like that. But the consequence ends up being that women lost a lot of authority in those coming years.

HS: So, yeah, let me just jump in here and say that in the LDS faith now, that sort of the top woman in the LDS faith is the General Relief Society president. And at this point she only serves for a few years. And by the time she’s kind of figuring out what’s going on, a new one comes in. And if you ask people to name them, people are like, “um, she’s blonde…”

KR: They’re all blonde.

HS: Yeah, they’re all blonde and they’re all skinny too. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Back in this time period that Katie’s talking about from 1945. To 1974, that’s almost 30 years. You have Belle Spafford as the General Relief Society president. She was a boss. She did amazing things and she was in charge and she made decisions and she helped shape the curriculum and sort of at the same time where they’re kind of like, “We’ve got to dismantle some of this stuff. We have to consolidate this power.” And so they need to release and not have women with this continuity of power who don’t serve for four decades. And I think it’s also interesting. She left in April of ‘74 and Exponent started in July of ‘74. A lot of stuff happened in 1974.

HS: The 1970s were huge for this transition of power. In 1970, they end the Release Society Magazine. And in an effort to like streamline these publications they canceled a bunch of different publications in favor of three main publications, Ensign for Adults, New Era for Teens, and The Friend for children. But all of those publications were going to be under the leadership of this priesthood correlation committee.

AA: Yeah, for people who don’t know too, this is a group that’s exclusively men. And so we’re saying the group of men canceled all of these publications and consolidated.

HS: And I’m sure in their minds, they’re like, why should we have two things? Let’s just have one that’s for everybody. But the research shows, even if you’ve read that book, Invisible Women, when you try to make things universal, they default to being male. So you’ve got your crash test dummies who are for the average male body. iPhones and all of our technology, pianos designed for average male hands, not female hands. And so you see that people can go in with the very best of intentions and I’m willing to gift them that, but it ends up that one size does not fit all, nor should it.

We’ve got to dismantle some of this stuff. We have to consolidate this power.

KR: Another big aspect of this that that ends up tying into these Boston women and the projects that they’re doing is that in 1970 priesthood correlation committee also ends the financial independence of the Relief Society on the global and the local level of the Church. So these grain storage programs and these other huge ways that the General Relief Society had raised money over the years, they’re instructed to send that to the general funds of the Church and they lose access to their own funds. On a local level, they also are asked to pass things over to their general funds and then really studied budgets come out of what the bishop assigns them.

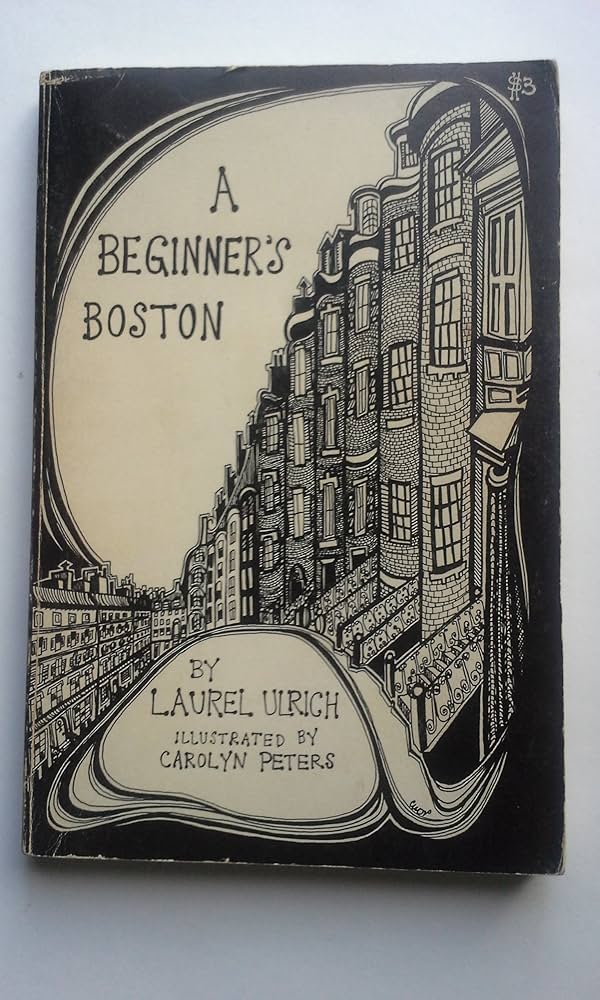

HS: So let’s pick that up in Boston with these women. You can see that the women who started Exponent II, they started with this model of more empowerment and the women were doing all sorts of really interesting things. One of the things when, if you ask Laurel or Judy or Claudia what sort of started it, they will all talk about A Beginner’s Boston, which was this guidebook that the Relief Society decided to publish and put together. Laurel was in charge of it and they sold it and they had the Boston Globe review it and it was reprinted multiple times. It was a huge success. It made them so much money. They were buying new curtains. They were changing out all the appliances in the buildings. They were paying for bills, for babysitters. When people would attend the women’s meetings midweek… I mean, they just had so much money. And then all of a sudden that money’s gone, that money is taken away. And not just the money, but it’s like, “Oh, we don’t need you to do those projects. Just do what we tell you to do. We’ve got some jobs for you.” And those women were happy to serve. They were happy to pitch in and do whatever they were called to do, but they missed being able to be a little bit ambitious, to develop their talents, to kind of work with this cadre of women.

And Boston in the seventies was just… Boston anytime is fascinating and I’m completely biased and I will totally admit that I was there for 22 years, but Boston was really this hub of intellect and innovation and ideas. You’ve got the civil rights movement going on. You have the ERA which, when the ERA first came out, it was not a foregone conclusion that the Church was going to speak out against it. If you look at the Utah Constitution, in it there are a few lines that the ERA has taken almost verbatim. I mean the ERA is based in part on the Utah Constitution, which just basically says you’re not going to get discriminated against because of sex. It’s very very basic. So you have Laurel Ulrich getting the book, The Feminine Mystique from her ward organist. Like that’s just normal. That’s just who these women were. And they didn’t think they were radical. Nobody felt like they were doing crazy underground work. This is just what they’re doing.

So they do this A Beginner’s Boston and then they talk with Eugene England and they pitch, can we do an issue of Dialogue, of this Journal of Mormon Thought that’s progressive leaning, which I think is also in response to the Church kind of taking over these periodicals and everything having to go from the absolute top down and be filtered through this sort of Salt Lake lens. For many years when you would listen to our general conferences, so much of it felt very Salt Lake specific. They would talk about certain things that… I’m in California, I’m like, what are you talking about? I don’t understand what you’re talking about. The culture just got so woven with some of the doctrine. So they ask if they can take over an issue and it’s called the Pink Issue and, Katie, isn’t it still the most requested, read, sold issue of dialogue?

KR: Well, it’s a collector’s item that is incredibly hard to get a very sought after collector’s item.

HS: It’s very treasured and then these women they’re like, we’re on a roll like what can’t we do? Claudia Bushman was like, everything we touch turns to gold and then they’re like, let’s do an institute class. Let’s teach people. A lot of Church history wasn’t taught at that point. I think there was one picture of Emma Smith in the Church archives, and it turns out it wasn’t even Emma Smith. It was just kind of abysmal, the lack of women that had been documented and researched in Church history.

So they are doing this and this also again speaks to Boston, that the leadership is like Awesome. Go for it. And it’s not like, Okay, here’s this man and he’s going to oversee and you all have to submit to him and get approval for these things. These women were just told, you know, go for it.

And so one of the women, Susan Kohler, she went to Harvard’s Widener library and she’s digging in the stacks in the Mormon section and she comes across this huge stack of those original Exponents, Woman’s Exponent that Katie was talking about earlier. And here you have all of these feminist foremothers that are really complicated because they’re suffragists and polygamists, which talk about what feels sort of like an oxymoron. Like, how can you blend those things? But these Boston women, they sort of felt like that because they were very devout. They were very devout Latter-day Saints and yet they considered themselves feminist. And so this is how it sort of came to be.

Katie? You take it from here.

KR: Yeah, so what is radical is so dependent upon your context, right? So in Boston, there are groups like Boston Female Liberation, which also called themselves Cell 16 based on living in 16 Lexington Avenue. But the idea was that you’re going to have these like small groups of women who were pushing for women’s rights. And if you have so many different small cells, they couldn’t be infiltrated and broken up. And if you take one down, the movement is not crushed, right? And so these Boston Mormon feminists call themselves the LDS cell of women’s lib and they’re doing these projects, but what they are doing does not feel radical compared to other groups. There’s other groups who are publishing very actively for bodily autonomy, for abortion rights, for access to free childcare, improved access to education. And these women care about a lot of these issues, but they are talking about them in a relatively tame way and in the context of their lives as LDS women.

So you have women who are the wives, bishops, and stake presidents. They may have several children and you have some single women, like Judy Dushku, who starts with these consciousness raising groups. When she is not married, she comes out as a graduate student and then becomes a comparative politics professor at Suffolk University and is a couple blocks away from Boston Commons and takes her students after class down to the commons to see whatever protest is going on, to hear. And so when she takes a little rhymed manifesto that she gets from this other feminist group that she’s visiting to her friends, like this is a cause for debate and discussion with these Mormon women. How does what we believe compare to this poem that talks about living for ourselves. Aren’t we supposed to live for other people? Isn’t that what we’re supposed to do, serve and be Christlike? And how do we talk about our growth and our independence within the context of our lives?

So as they start Exponent II they are in each other’s houses and in each other’s lives and continuing these conversations and because they came to feminism from so many different entry points, they had a lot of disagreement and a lot of debate and a lot of argument that none of these major topics were points that they all agreed on in the same way. But these group projects became a way to work through difference and be in community with one another.

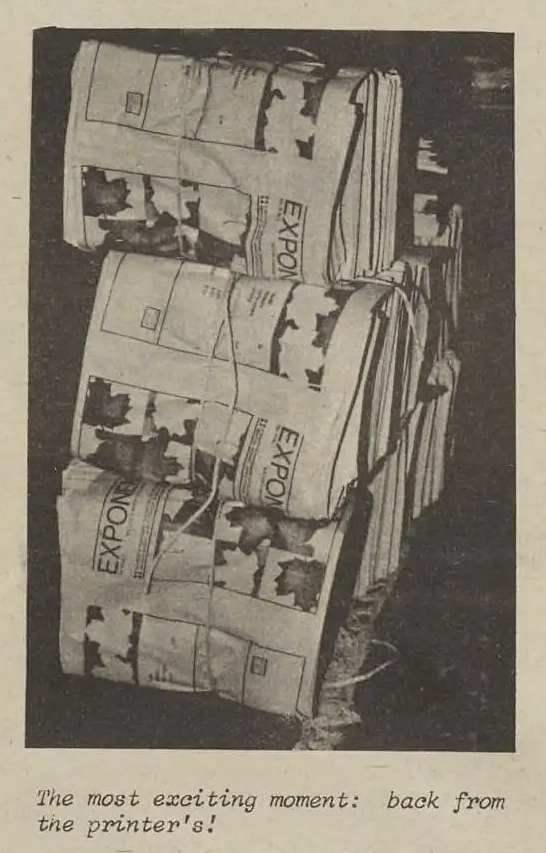

So we have those earlier projects and then they decide to do the newspaper. And in these days, they are doing what we call “paste up parties”. And as we started this project, I kept hearing about paste up, but I really didn’t understand what that meant. You know, by the time I was doing anything with publication, I was using Adobe InDesign, right? So paste up, they would have these like glass boards with grids on them and lights behind them. They call them light boards. And then they would have paper on it and they would paste up the columns of text and put these headings on one letter at a time and hand draw the art or put these art pieces on and then take that to the printer and get these blue pages back and mark it up for editing and then take it to the printer.

It was a very physically involved process. They’re shoulder to shoulder, they’re in each other’s homes. It moves to different houses over the years, according to who has the space available and the time available. But early on, they’re in Grethe Peterson’s home in Cambridge, and her husband Chase was in the administration of Harvard and they had this large house where they had this fourth story kind of attic space that was not being used, and it had this large ping pong table from a previous tenant and they take that over as their workstation. They have these light boards on there. They have tape and glue. They put all of these old issues up on the wall to look for examples for design continuity. And her golden retriever, Muffin, is like the receptionist as these women come and go once a quarter for these meetings. And there’s a lot of talking that happens, a lot of sharing of food, of talking about each other’s lives and raising each other’s children, and publishing. It was a mix of all of these things together.

AA: Amazing. I love all of those details. And I’m picturing also a bunch of them had kids too, right? I mean, this is a major undertaking to do, and I’m just thinking, like, constantly interrupted to have to go to attend to their…

HS: Yes, and that’s just normal. That’s part of it, is having the kids there. And I didn’t really realize it until when I came on in 2000—and January of 2000, I had my second child and then in early March, Nancy Dredge called me and asked if I would be an associate editor. And I was like, well, I don’t know. I just had this baby. Am I allowed to show up and edit and work with you while I’m nursing? And she was like, Of course you are. Welcome to the club. This is what we do. And it absolutely was what we did and what they did. They called it “Zooing It With The Kids.”

AA: Oh, I love that. That’s so great. Okay, so what was the reaction of LDS women who got Exponent II? And I guess first I should ask you, how did they distribute it? How did people find out about it? How did they request it? How did they receive it? And then what did they think?

HS: Well, in the beginning, it was less about requesting and more about receiving. They just were like, we are going to spam your inbox. Basically they sent it everywhere. They sent it to anyone that they knew, like give it to your friends and just distributed. Of course, the local Boston women knew about it, but then they would contact their friends in Utah and be like, “okay, we are sending you this”. And the friends are like, “we’re so excited.” And Katie, we’ll get to this in a minute. They just thought like, I’ve got the best idea. Let’s send it to the Church office building. Let’s send it to every General Authority for him to give to his wife. And they’ll be so excited about it. And we know that they also sent it to some BYU professors.

And so Katie, in a second, we’ll get to some of the men’s reaction, but the women…in general, the women who read it loved it. And there’s just such fun fan mail where people are writing, you know, “far out of feminist magazine for Mormon women.” There’s just all of this excitement and it’s really filling a need. And as Katie and I always talk about, it is not a monolith. There were so many different things. There was, you know, recipes and excerpts from the original Woman’s Exponent about suffrage and rights and they just kind of, it was like a sampler platter and maybe you didn’t like one piece, but you like this other one and you didn’t expect to like the whole thing. Nobody expected to wholesale embrace everything.

And the women, the people who didn’t like it were often the ones who didn’t read it. Where we were like, “Oh, there’s this thing that I’ve heard they talk about Heavenly Mother,” or “they use the word feminist. It’s a women’s lib thing.” You know, it’s scary. It’s ERA. And so there were some women who were like, I can’t support this because I am committed to staying at home. And like…. more than half the Exponent women are like, yeah, me too. And I think that you still sometimes get these things. It’s like, “Oh, if you’re a feminist, then you hate men. You either don’t want children or you don’t want to be with your children. You’re going to prioritize work over family.” There’s just all of these associations that have just been beaten into us that are just ingrained. And, you know, 50 years later we’re still battling with some of the same stigmas and false associations.

But most of the women loved it. People subscribed. There were 2000 subscribers early on and everyone shared it with everyone else. They printed it on this really cheap newsprint. I mean, it’s just the flimsiest of the flimsy because they’re like, this isn’t precious. Enjoy it, read it, pass it along, use it to wrap stuff in, to mail to a friend—it’s all good.

KR: We have enough indelible ink in our lives. We can have something that is just to share ideas and keep moving on with our lives.

AA: Hmm. I love that. And I actually really love, you’ve mentioned it a couple of times, but there was like a multiplicity of views and that there wasn’t a need for purity of ‘this is the one way to be a Mormon feminist’. I love the openness and that’s something that I feel like feminists right now could really learn from in the Church and out, just like more broadly being able engage in dialogue and conversation and make space for other points of view. I think that’s so fabulous that that was present in their ethos.

KR: From the beginning they prioritized community over ideological purity. And my favorite example is in the second issue on the same page. On the top, there is an article by this woman who’s arguing that the right and faithful thing for mothers to do is, when you have young children, you should stay at home with those children and maybe you do something else later, but this is the right thing for you to do. And then right under that is an article Judy Dushku wrote where she interviewed a woman who was a doctor. Her husband was also professional, and they had a nanny for their young children, and they felt that that was the right thing for them to do for their families. And so that’s on the same page where you’re presenting that there isn’t just one way to be a woman or to be a mother or to be a feminist. They’re making room for more space than that.

HS: And Exponent has continued that tradition. With Kate Kelly a few years ago there was this Ordain Women Movement and we had a whole issue on Ordination, and there was such a lovely, not even balance but just a variety of perspectives because balance implies that there’s two, but there’s not just two, there’s a multiplicity. It was these different quilt squares of this person believes this and this one believes this and they can all be displayed and valued. And people get to take what works for them and then be exposed to other things in a way that isn’t threatening.

Another example of this privileging community over sort of ideological purity or having to somehow prove your feminist-ness or prove your Mormon-ness is in the late 70s. You have Sonia Johnson, who is the leader of Women for ERA. The Church at this point has come out and said, “No, we’re not doing this.” And Judy, of course, Judy’s always been I think the most radical of the Exponent women. Judy is just this fabulous combination of the devout rebel where she is just fabulous. So she decides that she wants to invite Sonia Johnson to Boston and have a meeting and have her speak. And, again, instead of people saying “This is what she believes. This is what she stands for.” “Let’s let her tell us. Let’s ask her questions. Let’s hear her lived experience.” And everyone was not for it. And instead of just sort of Judy saying, “Well, too bad we’re doing this.” She held the meeting, but she made sure it was not an Exponent-sponsored event. She made sure that it was no judgment. If you don’t want to come, that is fine. This is not going to be a test where, you know, if you don’t show up, then we’re suddenly going to kind of cut you out.

There were some women who cut themselves out, who decided this has gone too far, I don’t want to be part of it. They themselves backed away. But the majority of women, from what I’ve heard, they felt that their views were respected and they didn’t feel like they had to believe a particular brand of Mormon feminism. And Exponent has always said there is not a brand. Whatever you are, that is your brand and that’s yours. It’s like when you give people a recipe and everybody shows up and you’re like, is that really the same recipe? That’s things look so different and that’s how it is. Everybody puts it together differently. Everybody gets their stuff at different places and it all comes out unique and there’s a similarity and a little bit of continuity, but it’s all just…

there isn’t just one way to be a woman or to be a mother or to be a feminist

AA: And it makes for a great buffet table if they’re all different! Okay, so let’s talk about what you were kind of referring to earlier in terms of how the men reacted. And by that, I mean, I guess you could talk about how regular men, like the husbands of these women reacted, but specifically how did the General Authorities of the institutional Church, how did they react to the Exponent II?

HS: The first issue came out in July of 1974, but 1975 became this big year where over the course of the year the Exponent staff started to hear things and then ultimately had like these three main meetings with male Church leaders. So early on in the year, Claudia Bushman, the founding editor, hears from Bob Rees, who’s editor of Dialogue at the time, that General Authorities had told the leader of the Church history department, Leonard Arrington. That the Church was not to be appearing to be supportive of these unsponsored publications like Dialogue and like Claudia Bushman’s women’s lib paper. And he is required to ask one of his historians, Maureen Ursenbach, to pull an essay that she had written about Eliza R. Snow from Dialogue. So Bob writes to Claudia about that, and he’s like, “I hope that we’re not being blackballed. I hope this isn’t a big censorship policy, but I’m a little bit worried about this.” And a few months later at a staff meeting, their bishop, John Romesh, and Claudia Bushman’s husband, who was the stake president, Richard Bushman come to the meeting as emissaries for these phone calls that they’d been receiving from men in Salt Lake. And initially the bishop was like, look, I don’t want to upset the apple cart. He was a very nice guy. He had a good relationship with these women. He’s working with them in a lot of different callings. They’re all active LDS women and he is not trying to come and be the tough guy, but he’s like, we have a problem here. You’re, you’re using the announcements and Relief Society to talk about this and using the bulletin and using the Church building for some of your activities. And we can’t have that. And it’s like, okay, but is that a universal policy? Is that going to apply to daughters of the Utah Pioneers who also meet at the Church building? Is that going to apply to these informal groups of men who go play basketball in the week? And he’s like, I guess it’s going to have to be a universal policy, but all I know for sure is you can’t use the Church building. We can’t appear to support you.

And then Richard Bushman had gotten phone calls about these two main things that Claudia recognizes in retrospect as the things that really got exponents, negative attention from the Church leaders. And the first was an interview that she did with the Boston Globe. The Globe did an article about the Church, the LDS Church in Boston, and as wife of the stake president, she was interviewed and she talked about the racial restrictions. So we’re in 1975 and until 1978, the Church had this policy that Black members could not have the priesthood and both Black men and women could not go to the temple and receive many of the ordinances. And in 1975, she says that her husband would really like Black members of the Church to be able to serve missions, which they were then prohibited to do. And that there were a lot of white members who want this ban to be lifted. And we’re told that it’s going to need to take a revelation, but that is what we want to have happen. The Church was not happy about her talking about like, it looks like you guys are being restive. You can’t be talking to the press and be talking about these issues. We keep our stuff within the family; don’t talk to the press about big issues.

And then the second was what Heather had mentioned about how they had sent a flood of issues to the Church office building, expecting it to be so positively received, and they were surprised when it was not. What is radical depends on your context and for them, their paper compared to all these things these other women’s groups are doing in Boston, what they are writing is not in the least bit radical. And they see their own intentions and their own efforts, and they know that they are doing this as a very faithful effort to elevate women’s voices and talents and build community. But the men did not see that that way. L. Tom Perry was a new Apostle. He had been the Boston Stake President before, and he is put in charge of calling and he says, “it’s like you are trying to tweak the noses of the brethren”, that these women are somehow trying to show off that they they can do this thing. So that leads to a little bit of tension, but the women’s response is like, we are going to double down with our faithfulness. We are going to do our visiting teaching. We are going to be inviting to everyone. We’re going to accept all of the callings asked of us by these Church leaders. And we’re going to prove through our faithfulness.

They didn’t yet get that what the men wanted was obedience. It wasn’t about the faith. So then Elder Hales, who’s a new General Authority in Salt Lake and had moved from Boston, he had been in the Boston Stake Presidency, and he comes back for a stake conference and Richard Bushman, a stake president. And as was a common practice at the time, Elder Hales stays at the Bushman’s home for that weekend to participate in the conference, and he requests to meet with Claudia. And he tells her that Exponent II should cease and that it will come to no good and “look, I’m not telling you you have to end, but I am strongly cautioning you: you really need to resign as wife of the stake president. You cannot be seen as the leader of this feminist paper”. And he tells her that he had sent an issue through the priesthood correlation committee and that nothing was objectionable except for the art. The art smacked of an underground newspaper. That the men were kind of offended by these little quotes that the women have throughout; just taking things like instead of that ‘men are that they might have joy’ ‘that people are that they might have joy’. You know, how radical is that? But they’re kind of embarrassed by these little quotes that the women have throughout the paper, and they say, “look, like the paper is substandard in the way that is written, but it was generally given their approval.”

Heather, what else is happening with Elder Hales and the reading of the paper?

HS: Oh my gosh, I love this so much. So Elder Hales, he talks to the women, he’s kind tries to shut them down and everything. And then in the 50th anniversary magazine of Exponent that just came out recently, I was able to read Carol Lynn Pearson and she has chunks of her diary in there and in her diary she talks about Elder Hales reaching out to her and saying, “I read that poem you put in the Exponent and it is so beautiful. I think that all men in the Church should have to read it.” So clearly he’s reading Exponent and he’s not offended by it. He is enjoying it. And then he says, “next time you have a poem, don’t send it to Exponent, send it to Ensign.” And it’s like, wow, we’re in competition with the Ensign. That’s kind of exciting.

KR: So he tells them on one hand that it’s substandard in the way that it’s written, but on the other hand he says, I am a changed man having read this poem, Carol Lynn Pearson, and I want it in the priesthood manuals.

HS: Yes. Exponent’s trash, save it for us.

KR: So Claudia is really anxious about what to do because she feels this pressure. She says, “I am not repentant, but I am obedient. And I’m being asked by this General Authority to resign as the wife of the stake president.” And her friends are aghast and they’re like, you can’t do that. And they debate and they talk about all these things. And Claudia’s like, our talents are being wasted by the Church. And another woman’s like, “well, maybe we should open a modeling agency? Maybe they would like that instead.” But they really wrestle with how to approach this and really dig into like, what are our intentions?

And they decide to fast and pray and get together after they break their fast and decide, are we going to continue? And they get together and feel like the lord didn’t care one way or another what they did, that it was up to them to decide. And what they knew was that people were writing to them about how much it meant to them, about how it was giving them space in the Church—and some of them felt that way as well, that it gave them a place to be a Mormon and a feminist to reconcile these identities and that it mattered. And so they decide to write letters to Elder Hales about what this project has meant to them.

So they send those to him. He passes them on to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who then decide to send L. Tom Perry out specifically to meet with the Exponent staff in Boston. And so that happens in November of 1975. He comes out and it’s this big meeting and we have these incredible minutes, like five pages of notes from these minutes. And he tells them, “look, I am not going to tell you that you have to shut down. That will be up to you. But I am here to caution you.” And he cautions them about all kinds of things, how we have a prophet who speaks for the Church and how we need to let him speak and we don’t speak for the Church. And don’t get ahead of the brethren and don’t talk about big issues when they’re out there. Don’t talk about the Equal Rights Amendment. Don’t challenge gender roles. That was a big one. He’s like, “you can’t even be marginal on the issue. The role of men and women is different and children need the mothers in the home.”

And they’re like, did you read our issues? We are not telling women that they have to leave their homes. But he also tells them that the general boards of the women’s auxiliaries, they no longer represent the Church because the Church is becoming global and it’s not just Utah-based and those boards are going to be dissolved and regional boards are going to be come up, and if these women persist in this project they are going to be denied those great callings of being these regional representatives in these new boards.

HS: When did those come about, Katie? When did those happen?

KR: In the United and Canada? Still not yet.

HS: Okay, thank you.

KR: There are some new in 2021 finally, there are some area authority callings for women who report to the male area authorities. But it still has not happened for women in the United States and Canada. And there’s this great quote from Laurel in the minutes that Exponent II may not be that important, but the women of the Church are, and what if they need us? And also that kind of captures the spirit of what they decided to do.

Claudia does decide to resign the next month. She officially resigns. She’s like, I’m going to go about doing lots of valuable projects in my life, but I’m seeing the writing on the wall with this particular thing. And her resignation really sets the stage for Exponent to be able to pass on leadership, that it doesn’t just have this one charismatic leader, but that leaders keep coming up and they keep learning how to pass it on. And Nancy Dredge—who had just had her third baby and had just moved back from a stint in Korea where her husband had a Fulbright Fellowship—she’s like, I don’t know if I can really do this, but I’m interested in doing it and I’m going to give it a try. And then she’s editor for the next six years and does this incredible job of building it out even more as this like national platform for Mormon feminists to be in conversation for one another.

AA: Amazing. Okay. Well, what I’d love to have us do now is to have you share some highlights about the timeline between 1974 and today, basically the content of Exponent II. And that’s literally what you did with this book that’s coming out, 50 Years of Exponent II, which I mean, is it kind of like a best of album and….

HS: Greatest hits!

AA: Exactly. So first I’ll ask you how you selected the works that you chose, what was it like to put it together? If you could talk about that just for a second. And then I’d just love it if you could share some of your highlights.

HS: There was so much to go through and, and Katie and I, of course, have our own biases. So we tried to be as democratic as possible. We reached out to the editors of each thing and said, what are the pieces that you are like “if this isn’t in my section, I will never sleep again.” We reached out to the people on the blog and had people nominated. We put it on social media. So we tried to get as much feedback from lots of different sources. And there were things that came up that I wouldn’t have thought of, but that touched a lot of people. And I can, looking at them, I can see why this really matters.

Katie, how did you feel about the process?

KR: It was incredibly hard to select. So we have six units that go through kind of different editor areas and then a selection of the blog. And to narrow it down, we have the history as the first half, and then we have these units of selected works. And what gave me peace and lets me sleep at night, is that the pieces that didn’t make it in are still published in Exponent II. And the whole digital backlog was scanned and uploaded to archive.org by BYU Library, and it’s more accessible than ever before. That’s what really gives me peace, that these pieces that didn’t make it in this work are still published by Exponent. They’re not lost.

And then Heather had some great selections to talk about.

HS: Yeah. Let me pull one of my favorite ones is fairly early. It is from 1982. So that’s eight years in to Exponent II. And it is from Lavina Fielding Anderson, who I know you—like we do, Amy, you have a soft spot in your heart for her and all her good work. And hers, this is a talk that she gave at an Exponent date dinner before they even started the magazine. Once they found those original Woman’s Exponents. So like once a year we need to have a big dinner where we have a speaker and we just sit and talk, celebrate women and our awesomeness, and so Lavina Fielding Anderson was the speaker and she talks about, it’s called ‘On being happy and exercise in spiritual autobiography.’ And she talks about her own spiritual life. Then she broadens it out to the spiritual lives of Mormon women and what impacts them. And her last three lines, I just…if I were a vinyl lettering gal, I’d have this over my mantle. So let me share this. “I feel that we may have circumscribed our limits too narrowly. Our birthright is joy, not weariness, courage, not caution and faith, not fear by covenant and consecration. May we claim it.” She sounds like a prophetess right there. I get goosebumps every time I hear it, read it. It just is so powerful saying that it’s too narrow; our birthright is joy not weariness. It’s so much to chew on.

I had a couple others, but one very—and this is one that’s very personal to me, it’s from Fall of 2002. I was one of the associate editors. And when I read this, I cried. It just really, and I’m going to get emotional just even talking about it, it’s Encircling by Kylie Nielson, who is now a friend of mine. And so it’s really fun to have sort of worshipped somebody’s words and then to meet the person. So she’s talking about miscarriage and I’ll read a few of her lines.

“In my mind, I call her Eden,

a name without a mother or a child.

Still, I miss her head tucked into my neck, breathing softly,

her warm sleep body gathered in my arms,

even after holding other children of my creation,

like Eve, I suppose. On a brisk December birthday,

I would have swaddled her in a blanket or two

to take her home, instead of an early birth death.

May, so bright and shiny, two days later,

I sat in the sun by the pool, swimming suit taut

over my empty stomach. Every year now,

there’s that circling, this May, the December,

the May, she’s a thought, brief.

I find myself thinking another without realizing,

but the return is a comfort, a marking,

a naming of Eden, mother of my mothering.”

And this is one of the things that Exponent does so well, is these evergreen topics that you could pull something like that out of the original Woman’s Exponent, losing children, and trying to talk about it…it’s a very private grief. Not much has changed in a hundred years. It’s still something that women…a sorrow that they carry silently with them. And by her giving it voice, it was validating to me and so many other women who had experienced that same thing, but never had words for it.

AA: That’s so beautiful. Heather, thanks for reading those passages. What about you, Katie?

KR: So I had the privilege of creating the index for the book, and that was a new experience for me. But one thing that I found interesting as I was indexing pages to match with certain topics in the index, was how many times I was indexing your piece ‘Letter to the Brethren’, of how many different topics it touched on. And I was hoping that I could actually turn this back to you and have you tell us a little bit about that piece and where you were at that stage in kind of your development.

AA: Hmm, it’s really weird for me to read it now. I wrote it in 2013 and my tone is just so good and dutiful, like I’m just trying to be that good girl showing deference to the patriarchs. And I really did feel back then that I just thought they just don’t know. They don’t know how we’re struggling. They don’t know how painful this is for us as women. They meaning like the leaders of the Church, the male leaders of the Church; if they knew they would help us. And I wrote this letter to Elder Holland. He was the leader that I felt closest to for various reasons, and I just poured my heart out, specifically about the temple, because it was the temple language that was the most wounding to me. And I think partly also, it’s really hard to read overtly patriarchal, subjugating language in scripture, but the temple’s the only place where you actually have to covenant that you accept it.

You can walk out of a sacrament meeting if you don’t like the talk. You can walk out of Relief Society. There’s no real loss if you do that. In the temple, there’s no way out of the language. It’s scripted and you’re there—you know, if it’s your first time, you’re there with your entire family, your parents around you—and you literally make a covenant to God and witnesses that you accept that subjugating language. And that felt like spiritual violence to me, to be put in that position. And I was just desperate. So writing about it felt really radical because we are technically not supposed to write the language. It was very hard for me, but I thought he certainly just must not have thought about this.

And then, to get that letter… I just remember so clearly opening the mailbox and getting the letter. Oh my gosh, he wrote me back! And opening it, and it was just like the most generic letter back from his secretary. And I thought, I don’t even know if he read it. It was heartbreaking. It just made me feel really disregarded and completely unseen, and it highlighted how structurally powerless I was.

But I’m glad that happened in retrospect, because that was the seed; that event, me writing it, sending it, getting a crappy response, and having to reckon with that, that was the seed that resulted in me writing subsequent stuff like ‘Dear Mormon Man’, which was really an important thing for me to do too, and then that’s what led to Breaking Down Patriarchy. Honestly, I really truly would not be here if I hadn’t started there. And Exponent was…it wasn’t an important part of my journey, it was a critical, it was the first step in my journey. That’s what it changed for me.

KR: You articulated in that letter so many points that you touch on, so many topics within how this language affects marriages, how it affects families, how it affects boards, how it affects individuals and their relationships with the Church, and it’s such a great example of how it goes from the personal and how this is hurtful to you to then looking to the structural and that entire shift that takes place.

HS: And that was the same as those early Exponent sisters sending it to their office building. You’re just like, if they knew they would be so happy, like they just don’t know. They just don’t know.

KR: My very first blog post for Exponent II was an open letter I wrote about women not speaking in general conference enough, and then getting a response back that was all these reasons why they don’t have more women speak. And it was all reasons that the men had created, rules that they had imposed. That’s what led me to take the courage to speak publicly about these issues as well. And I love that that is the platform that Exponent continues to provide; these first steps to learn how to have conversations.

Its issues that maybe people have thought about in previous generations, but it’s new again for each person as you have your feminist awakening. And then it puts you in community with other people who have thought and cared about these issues. And it becomes this soft-landing space where you are no longer alone.

It’s a wonderful catalyst.

AA: It is. I would say that’s exactly what Exponent II has given me, critical information and community, especially as I was waking up and just flailing and struggling so much. It gave me those two things. So what would you say? I mean, that’s what it means to me for sure. What would you say this new book and Exponent II in general offers women? And maybe this will be kind of like your final takeaways.

KR: So Gerda Lerner, that feminist scholar, talks about how women’s history is the primary tool for women’s emancipation. And this is, is our attempt to help give Mormon feminists and give women part of their history that is never going to be handed to them in any other way. This is the first institutional history of the organization. And there are some other great resources like Mormon Feminism, but there are so few stories where we can look at the arc of 50 years of women’s lives and relationships and conversations and struggles and to be able to hand someone this and let them see that they are not alone. They are not the first to experience this. They are not reinventing the wheel when they encounter issues of patriarchy and structural sexism. But they are standing on the shoulders of giants and they can build upon a legacy and kind of walk forward together.

it’s new again for each person as you have your feminist awakening

HS: Yeah. And just building on what Katie said, again this is something that Katie and I have discussed is that what I really think Exponent at its best does well is it provides a model for how to teach people like, don’t eat your young. Don’t eat the baby feminists. When somebody new comes along and they’re like, Oh my gosh, did you know that Joseph Smith talked about Heavenly Mother in one of his versions of the first book? You’re like, duh, everybody knows that. You’re so late to the party… We need to have this soft spot for them to land. We need to let people know “you’re right. That’s important, what you’re thinking about. You don’t have to be the first for it to be important. It’s important.”

And then the flip side of that is that by documenting all these things you’re recording so that you’re not ignoring the foundational women. You’re not reinventing the wheel and pretending like they never said these things before. So it’s this sort of two prong: don’t eat your young and the other is don’t put your grandma’s out on an ice floe. Let’s honor these women, both the young and the old. And let’s learn from each other and let’s take care of each other and nurture and validate and witness our truths.

AA: So powerful. I’m so grateful for the Exponent II and grateful for this new book and the work that you’ve put into it because I do have to say, too, when I read the book when I was reading the beginning… I’ll just say this as we wrap up. I have in some ways kind of taken a step back even from LDS women’s history because it can be so painful for me. And what I didn’t expect as I opened it up was how actually healing it was to come back to those Mormon foremothers, to the story that you just told on this episode about how it came to be and to feel that sense of this is my tribe, these are my people, these are the women who have nurtured me and have been there for me. I was bawling, bawling as I read it. And so deeply, deeply grateful for that reminder of things I had known and also stories I had never heard before in this book and articles I had never read. The reminder of where I come from and the community that’s nurtured me.

So I will be grateful forever for your work and for this book. And I highly recommend to listeners to pick up this book, no matter your relationship with the LDS Church. And honestly, even if you’ve never been LDS, it would be a fan, a completely fascinating book to read about LDS feminism. So can you just tell us really quickly how to find the book and where to find Exponent II, where to find all your work?

HS: Exponent II is at exponentii. org. And from there you can find tabs where you can find a link to buy our book on Amazon. But you can also go to independent booksellers and have them order it and go to Barnes Noble. But Amazon is the trusted evil to be able to get our book.

AA: Yes. That’s a great way of putting it. I love it. Thank you again so much, Katie Ludlow Rich and Heather Sundahl. Thanks for being with us today and thanks again for all you do.

Our birthright is joy,

not weariness.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!