“think of all those young women of color and young Black women who never got the chance”

Amy is joined by Dr. Kabria Baumgartner to discuss her book, In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America, and explore the triumphs and struggles of young Black women seeking an education in pre-Civil War America.

Our Guest

Dr. Kabria Baumgartner

Dr. Kabria Baumgartner is a historian of the 19th-century United States, specializing in the history of education, African American women’s and gender history, and New England studies. She’s the author of In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America, which tells the story of Black girls and women who fought for their educational right in the 19th-century United States. Her book has won four prizes, including the prestigious 2021 American Educational Research Association’s Outstanding Book Award.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: In the fall of 2023, I took a class in my PhD program that explored the role of education in social movements in the United States. One of our assigned books was called In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America by Kabria Baumgartner. I was really intrigued. Never had I thought about educational activism before, and I knew almost nothing about Black women’s activism before the Civil War. So I was very excited, and this book did not disappoint. It turned out to be one of my favorites of the semester and it was a favorite among my classmates as well. I am thrilled to welcome to the podcast the author of In Pursuit of Knowledge, Kabria Baumgartner. Thanks for being here, Kabria!

Kabria Baumgartner: Thank you so much, Amy! I appreciate you inviting me to be on your podcast.

AA: I’m super excited that you’re here. I’m really honored, and I did absolutely love the book. I recommend this to listeners, that this is one that you buy and read, because I learned so much. And again, I love discovering pockets of history that I’m like, “I didn’t even think to think about that issue!” So this was just really eye-opening. I can’t wait to get started. I’ll introduce you first with a professional introduction, and then we’ll have you tell your own story after that.

Kabria Baumgartner is a historian of the 19th-century United States, specializing in the history of education, African American women’s and gender history, and New England studies. She’s the author of In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America, which tells the story of Black girls and women who fought for their educational rights in the 19th-century United States. Her book has won four prizes, including the prestigious 2021 American Educational Research Association’s Outstanding Book Award. Well deserved, and congratulations, Kabria. If we can start by having you introduce us to you, where you’re from and some factors of growing up that led you to do the work that you do today.

KB: Yes, that’s a great question. I would say that in addition to my work studying 19th-century US history, I’m also a community engaged public historian. A lot of the work that I do is deeply researched and in collaboration with local communities, particularly here in Eastern Massachusetts, but also in the New Hampshire Seacoast area. Now, I’m not originally from this area. I’m from Los Angeles, California, born and raised, and I thought I would live my entire life in that city when I was younger. But I began to develop a deep interest in the history of New England and the Atlantic world. And that got me thinking about studying the history of African Americans in this region, looking at the history of the slave trade and slavery in the region, and what it meant for African Americans to build their own communities here.

AA: That’s really interesting. And you live in Boston. Do you teach at Northeastern?

KB: I do. I live in the greater Boston area, I say, and I teach at Northeastern University.

AA: I love Northeastern. My oldest daughter went to BU, so very close to you, and we visited Northeastern and loved it. She had a couple of friends who went over there so she would go over. The campus is right by the art museum, right?

KB: Yes. The MFA.

AA: Yeah, the MFA. We love the MFA. We went there every time I went over to visit in Boston, but that’s a very different climate from LA.

KB: It is.

AA: Are you… Are you okay? Are you surviving?

KB: Usually around March I start to ask myself, “Uh, what am I doing in Boston?” In terms of the history, there are some interesting parallels between Los Angeles and Boston. Especially when we think about early Black communities, that history happened at different times, but there are certainly parallels. I’m always really excited to hear about scholars who are exploring the history of education in California, in Los Angeles. Those are really vibrant histories there, even as I study it mostly on the East Coast.

AA: That’s really great. Well, let’s dive into the book and use the book as the talking points for the conversation, so you can acquaint us with this whole really rich story. My first question is, can you tell us where and when the story is situated and set the scene for the rest of the story?

KB: Sure. My book begins with the story of young African American women in pursuit of knowledge and in pursuit of schooling. I follow the story of Sarah Harris, who was a young Black girl who grew up in Connecticut, and wanted to pursue an advanced education so that she could become a teacher. And when she was living in Canterbury, Connecticut, she had walked by this school called the Canterbury Female Seminary. And that school was run by a white Quaker woman named Prudence Crandall. So Sarah Harris walked by this school, she saw young, white women taking advantage of this elite education, and Sarah wanted that for herself. She wanted to experience the joy of learning and she wanted to be in service to her future profession, which was teaching.

And so she approached Prudence Crandall. She talked about her ambition to become a teacher that she wanted to study there. She presented her qualifications, that she would be able to excel there, and Prudence Crandall carefully considered it and finally decided that she would admit Sarah Harris. It was that moment, Sarah’s ask and Prudence’s acceptance, that completely disrupted the town of Canterbury. White leaders were enraged. They were not only mad at Sarah Harris, they were mad at Prudence Crandall. And they did all that they possibly could to thwart what would have been the first integrated school in Connecticut. So the book starts there, with that story, and then broadens out to follow the experiences of African American girls and women who are in pursuit of opportunities for schooling and teaching.

AA: One thing that’s really important and sometimes surprising for people who haven’t studied history is to think of segregated schools in the north, right? This isn’t in Georgia or something, this is in Connecticut. And this is antebellum, which, for those who don’t know, means before the Civil War. What were the laws on the books? Was it prohibited for Black people to be educated, or educated in white schools, or was this just de facto segregation?

KB: I think it’s a mix of both. What I found in studying this throughout New England is that it’s particular to certain towns and cities. I use this term in the book called “hyperlocal” to describe how unregulated it was. In Canterbury, Connecticut, we do have evidence from the early 1800s that Black children went to school with white children at the primary school level. It seems that when you got to higher levels of schooling, separation was desired by white leaders, by white parents, and sometimes by white students themselves. So that’s Canterbury. You might find that 20 miles away there were laws on the books at the local level that said that public schools there would be segregated. So there was no universal policy by the state of Connecticut or in Massachusetts, which is unlike parts of the South at this time that did ban Black education.

AA: Okay. That makes sense. I found that first story to be so compelling. That story about the courage of Sarah Harris and the courage of Prudence Crandall, like you said, for both of them to know what was right and stick with it, and they both endured a lot of abuse from the community. I don’t remember the outcome for Sarah. What did she end up doing?

KB: For Sarah, there was a particular moment when she was trying to pursue this advanced education. She was maybe in her early twenties and this advanced education was going to help her in her future career as a teacher. I think for her, other life choices happened. She got married, she eventually had children, and so she never got that advanced education that she wanted. She was able to attend the Prudence Crandall Seminary for some time, but as you said, there was so much abuse and harassment that they faced that one wonders what kind of learning they were really able to do in a sustained way. But they do talk about having had debates and they talk about having written essays. And they opened the school day reading the Bible and closed the school day reading the Bible. So we know that it was an intellectual environment, that they learned a lot, and that they were in a community and they enjoyed it very much, but it was punctuated by these bursts of violence. We can only imagine how awful that really was for them.

AA: Okay. The next incident that illustrates a similar trend is the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary. Can you tell us about that?

KB: Yes. I was quite surprised to uncover the story of the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary. When I say I began with Sarah Harris and Prudence Crandall, I began there, and following some of those young Black women led me to the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary. One of the students who had attended that school ended up at the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary. And one of the patterns that I noticed in studying Black women’s education is that oftentimes there’s one Black woman there, there’s usually another, and then sometimes even more. So in some ways, they attended these predominantly white institutions as a cohort. It was really interesting using census records, using school catalogs, and biographical records to identify the six Black women who attended the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary. And their attendance there meant that the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary was one of the first, if not the first, racially integrated female seminary in New York, if not in the North itself. It’s really a pioneering institution in that way. It’s an integrated institution. Young African American women are there as equals, they are to be respected, they are to be engaged, they are to be part of the community, and that was really incredible to see in the 1840s.

when you got to higher levels of schooling, separation was desired by white leaders, by white parents, and sometimes by white students themselves

AA: Yeah, it really was. I was shocked, too. That was so interesting. One theme that came through for me in that part of the chapter was the concept of respectability and this crushing pressure that these young women felt that they had to prove themselves as the representative of the race, right? The race and gender pressure of being such pioneers, and just how tragic it was that they constantly felt that need to present themselves in a certain way in order to be accepted. And again, it’s just not fair to put that pressure on someone to say, “I represent this whole entire group of people.”

KB: Exactly. Right. I mean, they certainly talk about that pressure and having to perform in some ways, and at least in the materials and sources I’ve been able to find, these young women didn’t often talk about the racism they experienced. But there were subtle hints. So they were experiencing some racism, they were feeling the pressure of what it means to be in a predominantly white environment, but they knew why they’re there. They understood their purpose. For a lot of them, it was to be a teacher, so they had to get this education at a high level so that they could take it back with them to their community. I think they endured, and for me that was something that was important to highlight in this chapter. That these were young Black women students who endured because they wanted an education.

AA: Yeah. That makes me want to pause here and talk about one of the overarching themes in the book for me, and that was the driving motivation that a lot of these women that you talk about – because there are so many fascinating stories throughout the book. But one thing that binds them together is this motivation for personal purpose. Can you talk a little bit more about that? Was it about racial uplift or was it for a personal sense of mission? Why were they working so hard specifically in the field of education?

KB: Yes. I find that a lot of these young Black women were in pursuit of knowledge because they saw it as one of the few opportunities open to them at the time. In the 19th century, when they’re dealing with gender prejudice, they’re dealing with racial discrimination, what avenues or paths are open to them? What’s available to them? And they found that there were very few paths for them, but one of them was education, one of them was schooling, and that they had a role to play in pushing for educational change. They feel that they could do it. And to be fair, they were successful at it, so they were able to realize these equal school rights victories. They were able to democratize these female seminaries and public high schools and even primary schools.

So they felt that that, in some ways, was their calling and their purpose. It was individual in that they individually became teachers and gave back to the community, but I think that they saw their work not just in collaboration, but as having an even deeper impact that they would make that path for the next generation that much easier. I think that is what bound them together, because they all knew each other. That’s another thing that was really fascinating to uncover. At first, it might seem like these cases are separate. There’s a story here, there’s a story there. But in the research that I did, I noticed that they were all part of Black communities that were networked. And so they knew each other, they supported each other, and they were all fighting for equal school rights no matter where they were in New England.

AA: That’s so cool. Yeah, there was this individual motivation and then the combined effort that was really, really cool to see too. And the impact that that can have when a lot of people are pushing together in concert, right?

KB: Exactly. And I think that was the part of the book that I saw as sort of trying to shift the scholarship. We might tell, and we have told, the individual story of the Prudence Crandall Seminary. There are quite a few books about it. But to connect that one to the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary, to connect that to, decades later, Maritcha Lyons at Providence High School. To see all of these as connected was one of the contributions of the book.

AA: Mm-hmm. For sure. And I think that’s why it was selected to be on our reading list in class, because we were studying how education is connected to social movements. Not just a one-off, yes, inspiring story of someone who was pushing boundaries and breaking barriers, that’s inspiring and really necessary, but these people were working together as a network that was actually changing the landscape of education because they were working together. And so many times that story, especially of women, and especially, especially women of color, it doesn’t get told. Things change and then nobody knows how or why.

KB: Precisely. Exactly.

AA: So kudos to you for bringing all of these stories to light. The next one that I wanted to ask you about is Rosetta Morrison, who worked alongside African American men to advance education for Black Americans, right?

KB: Yes. Rosetta’s story is not one that I expected to find in the archive. It’s one of those stories where you see the name once, you remember it for some reason, it sort of sticks with you, and then you see it come up again and again and you start to put the story together. It’s kind of incredible. She was bound out to service as a child in New Hampshire for a white family.

AA: Okay, explain that because that might be new to some listeners. What does it mean to be bound out to service?

KB: There was this practice in the late 18th and early 19th century, before there was a child welfare system, that if a child was orphaned and did not have family that could care for them, or even if the child did have family but the family was impoverished, that child would be a ward of the town or city and they would be apprenticed or bound out to service. That means that they would have an indenture contract where they would work for a family for a certain number of years, usually to about adulthood, which was 16, 18, sometimes even a little longer at 21. So we have records of Rosetta, probably orphaned as a child, who was bound out to service to a family in Exeter, New Hampshire, and she probably remained with that family until about the age of 16 or 18. We don’t have exact records for how long she spent with them.

AA: Okay, tell us her story. And I’ll just mention really quickly that this chapter mentioned the practice of requiring women to quit their teaching jobs upon marriage. This happened to her, right?

KB: It did, yeah. She was able to get some kind of learning while she was in this white household in Exeter, New Hampshire. It’s possible that she actually attended the public schools in Exeter. It’s not totally clear, but it’s possible. She was absolutely literate, she was smart and ambitious, and was able then to attend the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary. She stayed there for a couple of years, and in the book I talk about the curriculum there, which was really advanced. So she was prepared when she moved to New York to open her own school, and she did. She had an advertisement in the newspaper, and she welcomed maybe 50 to 70 African American children. She was running this school almost by herself, but she then recruited one of her former classmates, another Black woman, to teach with her, and she was successful. The school was sort of the pride of the community.

She then met Isaac Wright and, as far as I can tell, fell in love. And at that point she had to make this decision. She couldn’t really continue teaching if she’s married, she had to give up teaching, and so she did. And this is not abnormal either, I should say, for women at the time who teach while they’re single and then they get married and they stop teaching. They could stop teaching sometimes because of prevailing views, because of laws that are on the books that married women can’t teach. Some may not have wanted to teach after getting married, but they didn’t really have that option until much later in the 19th century. So Rosetta stopped teaching, but her life, as people can read, was very complicated and tragic. And as I was thinking more about her story, I realized that this book is not just a book that tells triumphant stories, as much as we like to think about education and triumph.

In Rosetta’s case, she had this advanced education, she was very smart, she was entrepreneurial, she wanted to give back to her community and she did. But because her husband was a fugitive slave, their family was always in a precarious situation. They were always looking over their shoulder and running. I found them in Maine in one census record, and they just didn’t have stability. Eventually her husband left the family, we think that he may have become a mariner and was part of seafaring adventures. So she was a single mother to a handful of children and she ended up as a laundress, someone who does laundry, and that was her fate. There was something about that story that was just… It’s always traumatic for me. At first, I’m approaching this history in a very triumphant way, thinking that education can set us free, and I’m realizing that there are parameters to that. There are limitations, no matter how much we want to achieve. There are other oppressive systems and processes that might get in our way.

AA: That was definitely my takeaway too. Reading the personal stories of what it actually felt like, for example, for Isaac Wright after the Fugitive Slave Act where there’s nowhere that’s safe. I mean, you can escape from the South but then it’s not even safe for you in the North. That was my takeaway, was like, what would Rosetta’s life have been like had there been just laws, right? If she had been able to work hard and do everything that she could do, and then if the structure had been different, her life would have been very, very different. It’s really, really tragic. And inspiring too, because you think of every child in her classroom that she taught. It has a ripple effect and she did so much good, but it’s just so unfair, all of the challenges and trials that she had to face, which is through no fault of her own.

There are limitations, no matter how much we want to achieve. There are other oppressive systems and processes that might get in our way.

KB: Exactly, exactly. It really reminded me that education doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Even though the principal of the Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary, Hiram Kellogg, had created this opportunity to bring in a cohort of young Black women, they were able to study there, they were able to achieve great things… That’s one path, that’s wonderful, but it doesn’t mean that those Black women who then go into other areas can enter them freely. It means that with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act her life is going to be impacted, and her education won’t save her, and her education doesn’t save her. And that was something I had to really grapple with in working on this book and thinking about education, because it’s not often how we talk about education.

AA: Yeah, for sure. So, those stories were in Part One of the book, which is organized by seminaries, the educational context of ladies’ seminaries. And the next part of the book is about public schools, right? Exploring the pursuit of educational justice specifically in Massachusetts public schools.

KB: Yes, that’s right.

AA: Okay. So the two women that I would love you to talk about from this section are Sarah Parker Remond and Eunice Ross. Can you tell us about them?

KB: Yes. I’ve been pretty fascinated with Sarah Parker Remond for a while, and I think I’m fascinated by her in part because I know where she ended up in her life and I’ve found that to be pretty incredible. To tell the story backwards, she is buried in Rome, Italy, and she ended up living a good part of her adult life there as a doctor. She was actually able to pursue her dreams of becoming a doctor in Italy and not in the United States, and I always found this to be really fascinating. It sort of speaks to a larger trend among African Americans, especially in the late 19th century and into the 20th century, who find a home in Europe and not in the United States. So Sarah Parker Remond – and we don’t quite know how to pronounce the surname – she grew up in Salem, Massachusetts. Her family was fairly well known and well regarded. There was an emerging Black middle class, and Sarah would be then part of that emerging Black middle class. She was very smart, very curious, she loved reading and read as many books as she could. Even though she didn’t have ready access to books, she would find ways to borrow them from friends and from acquaintances, and she was also able to attend the public schools in Salem.

These schools were integrated, so there were Black children seated next to white children, and that seemed to be fine for a while. It seems, though, that after Sarah was admitted into the public high school for girls in Salem, and she had achieved so much, she rose to the top of her class, the white residents of Salem then issued a petition basically calling for the expulsion of Black girls at the high school and Black children altogether, saying that they should be moved to a separate segregated facility. And the school committee entertained the petition, they debated it, and they voted and agreed to create segregated schools in Salem in the late 1830s. And Sarah reflects on this moment and she talks about how incredibly devastated she felt, how sad she was, how traumatic it was that she no longer had this opportunity for advanced learning, because it was a high school. When they segregated the Black children, they put them all in the same school. There was no grading, really, there weren’t levels there, they were just all in the same school.

Sarah felt this as an attack on her, an attack on her family, and on Black people and Black education. So she and her family actually end up relocating for a while. They came back to Salem maybe a little under a decade later, but the moment was sort of etched on her heart. She said she’ll never forget how she was treated, and as an adult she experienced similar incidents of racism, so much so that she left the United States altogether. And I think that her story is an incredible one. There’s a biography about Sarah that I think is great, and it’s about what it meant to be a Black woman at this time who had dreams, who had ambitions, and where can you realize them? For her, it was Europe. It was the United Kingdom and then Italy.

AA: Yeah. One of the hardest parts to read of the book, of many, was this part with the racist white parents and how awful they were when Sarah succeeded in school. This is a girl who is clearly gifted and doing so well in school, and those racist white parents were just awful. Awful. It was so heartbreaking to read that part.

KB: Right. And then for me what really stood out was that they felt emboldened to petition. There’s a document that one can find in the archives. They signed their names to it, so they’re very open about what they’re asking for, but that the school committee goes along with it. I think that’s the part where I pause. There were moments where they all could have said, “Let’s stop this. We don’t have segregated schools, let’s not start it.” That no one reflects in that way, that the school committee agrees to create a segregated school system, I think that was the part that I was devastated while reading it and learning about it. I could only imagine how Sarah Parker Remond felt, and that she may have felt even a little bit of guilt that it was her achievement that somehow had precipitated this, and she sort of hints at that in her reflection of the event later on. To put that burden on a child is unjust.

AA: It’s so true. And it was interesting, too, to be thinking about the psychology of the parents. That maybe it was okay with them to have Black children in their kids’ schools as long as they maybe “knew their place” or weren’t threatening. You know what I mean? Like, “We’ll be benevolent about this and allow them to be here,” but the jealousy and the racism of the hierarchy was triggered when she started to outshine their children. It allowed them to trigger that monster reaction like, “Don’t you dare,” you know what I mean? It was just interesting to read that.

KB: That’s right. There’s a scholar named Koritha Mitchell who talks about this term “‘know your place’ aggression” and that’s exactly what this is an example of. It was this idea that Sarah didn’t know her place and that her place was not at the top of her class. That she should have hidden her intelligence or not been ambitious. And because she didn’t know her place, there was this white aggression reaction to her that not only impacted her, but impacted all Black children in Salem.

AA: Yeah. Let’s move on to the story of Eunice Ross, because this was another really, really interesting story.

KB: Yes. What’s interesting about Eunice Ross, I was surprised and really happy to come across her name in a petition for women’s suffrage in the mid to late 19th century. Again, when we think about some of these young Black women, we see their names come up in a variety of social movements and a variety of causes. She was from Nantucket and she also was in pursuit of knowledge. She wanted to become a teacher and she had an opportunity to study with and be tutored by a white woman. So Eunice prepared herself to take an exam. A lot of the high schools in the mid 19th century in Massachusetts were what we might call today exam schools. They’re actually really tough exams. We have some records from at least the latter part of the 19th century, and we see what kinds of questions the students had to answer and pass in order to be admitted to the high school. So a lot of studying was required. Eunice passed the exam to attend the high school in Nantucket that she was trying to attend, and basically the school committee told her, “You cannot, even though you’ve passed the exam and you’ve met all the qualifications. Essentially, you’re Black and you’re not wanted here, and so you cannot attend.”

And that started her on the path of activism. She wrote to a few supporters in the town, the white woman who tutored her was also an advocate, and they end up corresponding with African American activists in Salem and in other parts of the state. They’re really pushing for what they call “equal school rights”. These battles, though, are so long. In the grand scheme of things they seem short, but they’re really long, right? If we think about one’s high school education, and I have no record that Eunice was ever able to attend the high school in Nantucket. So there’s this long, drawn-out fight and battle and debates in newspapers. And at the end of it, she never got to go to school. And I think that was, again, one of the lessons in telling the story. It’s not triumphant. The schools in Nantucket were eventually integrated, and schools in other parts of Massachusetts were, especially after 1855. But just think of all those young women of color and young Black women who never got the chance to attend the high school that they wanted to.

AA: Yeah, it’s heartbreaking. I have a couple more questions from this section. One is about how gender and race intersect here in really interesting ways. One of the things that I’m remembering is that when there were these petitions, and sometimes legal petitions, court cases where the Black community, parents and community members, they say they’re fighting for integration. It’s interesting that they selected little Black girls as the face of the issue. Can you talk about that? Because that was kind of a complicated dynamic at play there where they selected girls and not boys. Can you talk about that a little?

KB: Yes. This was really interesting to me to uncover. A lot of the Black families, as I mentioned, were part of a network. They knew each other, their families intermarried too, it’s very interesting. So we can think about how some of these young Black girls knew each other, or young Black women knew each other, prior to some of the school integration battles happening. Because they were networked, they were thinking strategically about how to win equal school rights. And this part of the story is really important because oftentimes when we’re thinking of social movements and we’re thinking about Black activism and Black activists, we’re not always thinking about their strategies or their deep intellectual planning and work and organizing.

In the case of equal school rights, that deep planning and strategy and organizing was about propping up the Black girl as the face of educational justice. Educational justice has to be achieved because there’s a Black girl here who deserves our sympathy and who we should all be fighting for and who we should all embrace. And I think it’s because there were prevailing ideas of the 19th century about girlhood and about womanhood. This idea that they’re harmless, they need to be protected. They don’t have the right to vote, so they’re not going to challenge politics in that way. I think there’s a way in which some of these Black activists played into that. So they used the Black girl as a way to really push for equal school rights. “Black girls aren’t going to cause any problems, so we can just educate them in our schools.” I think that was sometimes what Black activists were saying.

And part of the reason why I would say this is because there was a very famous case in 1849 involving a young Black girl in Boston named Sarah Roberts, and her father was adamantly against segregated schools. He had attended a segregated school and he hated them. He detested them. He said he would do all that he could in his power to abolish them, and they did use the terms “abolish” and “abolition” for obvious reasons. In this case with Sarah Roberts, her father, Benjamin Roberts, had an option of using his son as part of the case. And he made a strategic move and he said, “We will not use my son,” who at the time was like 10. “We will not use him. Instead, we will use Sarah because we think that she’s the one people will be sympathetic toward. She’s the one who’s considered harmless. She’s the one who needs to be protected.” So there was a state Supreme Court case involving Sarah Roberts. So there is a way in which the Black girl became the face of the social movement. And what was really interesting was to be in dialogue with Rachel Devlin, who wrote the book A Girl Stands at the Door, talking about the Black girl in 20th-century school desegregation movements. We see the same figure coming up, right? Ruby Bridges, Linda Brown, we see the same image being used and I think for some of the same reasons, still. So there’s almost a tradition within that strategy that Black activists adopted.

AA: It’s really interesting. And one heartbreaking thing for me, too, is the narrative of Black men, starting from the time that they’re boys, that they’re not as sympathetic, that they’re not also innocent children who also deserve education. That they’re just gentle little kids like every child. So just knowing that white people will not be as sympathetic to little Black boys also broke my heart, to be honest.

KB: That’s right. That’s actually the other part of the story that Benjamin Roberts was somehow keenly aware of, so he strategically put forward his six or seven year-old daughter, knowing how black boys are regarded. And it goes back to some of the stereotyping and the intersection, as you said, between gender and race. It’s going to mean certain things for Black boys and certain things for Black girls.

AA: Yeah. Okay, one more question on this part. You can tell I loved the whole book and this part especially. I was so inspired by these mothers who were leading the fight for their daughters’ education. It just really struck me that these are not people who were trained in politics or taught how to be activists. It’s the parents, it’s very community led, and it was a lot of times women led. These are moms. And I thought that was so inspiring.

KB: It was. One of the images that I use in the book is this image of a Black mother leading her two children into the schoolhouse, and there’s what I perceive to be a white male, maybe a teacher or a principal, kind of pushing them away saying “No, you cannot enter.” It was Black mothers who were absolutely leading the charge. And Black fathers too, as you know, with the case of Benjamin Roberts. What was interesting to see with some of these Black mothers was their own experience, which then impacted and shaped their daughters. In working on this book and tracing some of these families, it was very interesting to see that Maritcha Lyons’s mother had a connection to the Prudence Crandall Seminary. So it’s this thing where, okay, maybe her mother didn’t have an education, per se, in politics. But she knew what happened at Prudence Crandall Seminary, so she could kind of follow similar organizing steps in Rhode Island in the 1860s to open up an opportunity for her daughter, Maritcha Lyons.

AA: That’s so cool! And it is kind of a story of meaning and redemption and that it was all worth it when you think of Eunice Ross. There wasn’t enough time for her, like you said, in the four years that she was trying to go to this high school, but everyone around saw it. It did move the needle, and maybe it was a little too late for her, but in some of these situations that maybe felt like a failure to the individual, it actually wasn’t because then it opened up people’s minds all around them so that they could take that next step.

KB: Exactly. There really is something to this idea of intergenerational activism. Even in those social movements that fail, the next generation learns something from that. And they don’t quit, they keep pushing, they keep moving forward trying to create social change. I think that’s something that’s particularly powerful that these Black mothers offered to their Black daughters.

AA: That’s so beautiful. I love that. Okay, one other question I wanted to ask you about is the concept of “character education”. So they’re going to school and learning and then teaching not only history and reading and writing and arithmetic, but they’re teaching “character education”. What did that mean to them?

KB: I was particularly surprised to kind of move into and peer into the classroom. I will say that one of the hardest parts of writing a book about late 18th-, early 19th-century schooling in the classroom is not having a sense of what those classrooms always looked like. We don’t have many diaries from children describing their schooling. We have a few letters, but we don’t have diaries. We don’t know what things looked like on a day-to-day, week-to-week basis. And even from teachers, they weren’t always keeping diaries of what it’s like running their classroom. But in some of the work that I’ve been able to do and I’ve been able to piece together, I found that Black women teachers like Susan Paul and Sarah Mapps Douglass were practicing this kind of character education. They infused their curriculum with this character education, which was important to other teachers at the time. How do we create and shape American citizens, and how can our curriculum help us do this?

At least in the case of Susan Paul, she did this often through the Bible. She had these very young children reading the Bible. She had them talking about virtue, about honesty, but she also had them singing songs about patriotism and what it meant to be American, and what it meant for these young Black children to call the United States their home. Because Susan Paul led a juvenile choir, and as part of that juvenile choir these young children were singing these kinds of political songs, it’s also about building their character. There are ideas of respectability infused in it as well. But I think that Susan Paul and later Sarah Mapps Douglass really saw this idea that if they were able to nurture the child and build those values, that they would have an advantage in life. They would be able to pursue their dreams and be successful. That was their belief as teachers. And that’s how they taught. Even if sometimes those children who become adults were not able to realize their dreams, for all the reasons that we’ve just been talking about, because there are other oppressive systems at work that get in the way. Even if that happens, though, I think that these Black teachers saw their curriculum as providing a foundation, and they were really hopeful.

I think that’s another point, that despite all that was going on in the 19th century and that Black people and people of color have had to endure, a lot of them were so very optimistic. They believed very strongly in change and that change would come. And I think that infused the character education. Because I could imagine, on the flip side, a very pessimistic way of thinking about the country, and thinking about education and what the possibilities were. But Sarah Mapps Douglass, Susan Paul, a lot of these Black women teachers were very optimistic that change was going to come.

AA: I have a quote from you from this part that says that character education was “nothing short of revolutionary insofar as it explicitly enabled African American children to take their rightful position as morally upright citizens fully worthy of equality and justice.”

KB: Right.

AA: And that is so moving to me to think of just how hard they were working to instill that self-respect and self-esteem in these kids. And the knowledge, the deep internal knowledge, irrespective of what the law says or what that particular person might say to you, that you know that you’re worthy. And that you’re also preparing to be a contributing, upstanding member of society. I thought that was so moving.

KB: That’s right. It’s that these children who will become adults will have something to contribute to society. We expect them to have something to contribute, so we’re laying that foundation. I think that’s what these teachers were saying. They were laying that foundation so that those children would become the adults who contribute to their communities. Which was not always, as you said, in the laws that were sometimes passed and the stereotypes that abounded, that wasn’t always the case. It was sometimes thought that Black children who would become adults would have nothing to offer in terms of civic contributions or political and social contributions. But these Black women teachers said, “No, you will have something to offer and we will prepare you for that.” And in some ways they were right, because we see in the post-Civil War era, even in the North, that these Black children who became adults would hold office, at least the men would, and women would be involved in other ways. They would be involved in social organizations and political organizations, they’d be leading, at least by the 20th century, some of the anti-lynching campaigns. So, in a lot of ways, those Black teachers were right, and it was important that they were offering that kind of education.

despite all that was going on in the 19th century and that Black people and people of color have had to endure, a lot of them were so very optimistic. They believed very strongly in change and that change would come.

AA: One more question that came up for me is the debate even in the African American community about whether it was emotionally healthier for their children to attend integrated schools where they were having to confront so much racism, or whether it was actually better for them to attend all Black schools. With a Black teacher and with classmates who were undergoing the same struggles and kind of got it, so they felt a lot safer. Can you remind me if these Black teachers that we’ve been talking about, did they teach integrated classrooms or did they teach only Black classrooms? And then what’s your take on that debate at this period of history? What was better for Black children at that point?

KB: I think that’s a great question, and it came up, of course, in the 19th century and again in the 20th century around the Brown decision. I think for Susan Paul and for Sarah Mapps Douglass, Paul was in Boston and Mapps Douglass was in Philadelphia, they were both teaching Black children and Black children only. Boston as a city did not welcome Black women as teachers teaching integrated classrooms or all white classrooms until about the 1860s or 1870s. So when we’re thinking about integration in Boston, it might mean, and this is what some Black activists argued, that Black teachers would lose their jobs too. So that’s one part of it. And then the other part is, what would it be like then for Black children to learn from white teachers who might harbor racist ideas and might treat those Black children differently? It was absolutely a debate in the Black community.

Sometimes these Black activists who really pushed for integration weren’t pushing for integration because they thought Black children should go to school with white children, they were pushing for integration because they thought that was the only way to access resources. How do we get the books that we need in our classroom? How do we get enough space in our schools? How do we get proper pay for our teachers? The only way we might be able to do that is through integration. And this is why I say that when we’re thinking about social movements and strategies, these are the kinds of decisions that certain Black activists have to consider. And it’s why there’s debate even among those activists and sometimes there’s a prevailing view.

In this case, in the 19th century around the Equal School Rights movement, most Black activists said, “Let’s pursue integration. It’s the only way to get resources.” Even though you had a smaller contingent saying, “No, let’s not go that route. We’re going to lose our teachers. We’re going to lose the protections that might come that our Black children need. There’s so much that we’re going to lose.” The same debate comes up in the context of Brown in the 20th century, and it’s sort of this perpetual problem. It’s hard to say what’s better or what’s worse. I wish that these Black activists didn’t have to make such tough choices. It’s a real dilemma. And I think even today, we still haven’t democratized our schools fully, so that’s part of that struggle even in our present moment.

AA: Yeah, I mean, I’ve had conversations recently about historically Black colleges and universities. One of our dear friends, a boy that is one of my daughter’s best friends, is at Howard right now. And it seems like, from what he says and from what his family is reporting, it’s incredibly validating and empowering to be in those spaces, especially if you’ve grown up in a majority white community. It can have such a fortifying effect. But I guess looking back at the 19th century and even into the 20th century, just the power to make that choice, the sovereignty and authority to say, “I prefer for my child to go to this school versus this one.” That’s the underlying issue of whether it’s just or not. You can have both options. But for the white power to say, “No, you’re not allowed to go to these integrated schools,” maybe that was the underpinning in terms of justice and equity.

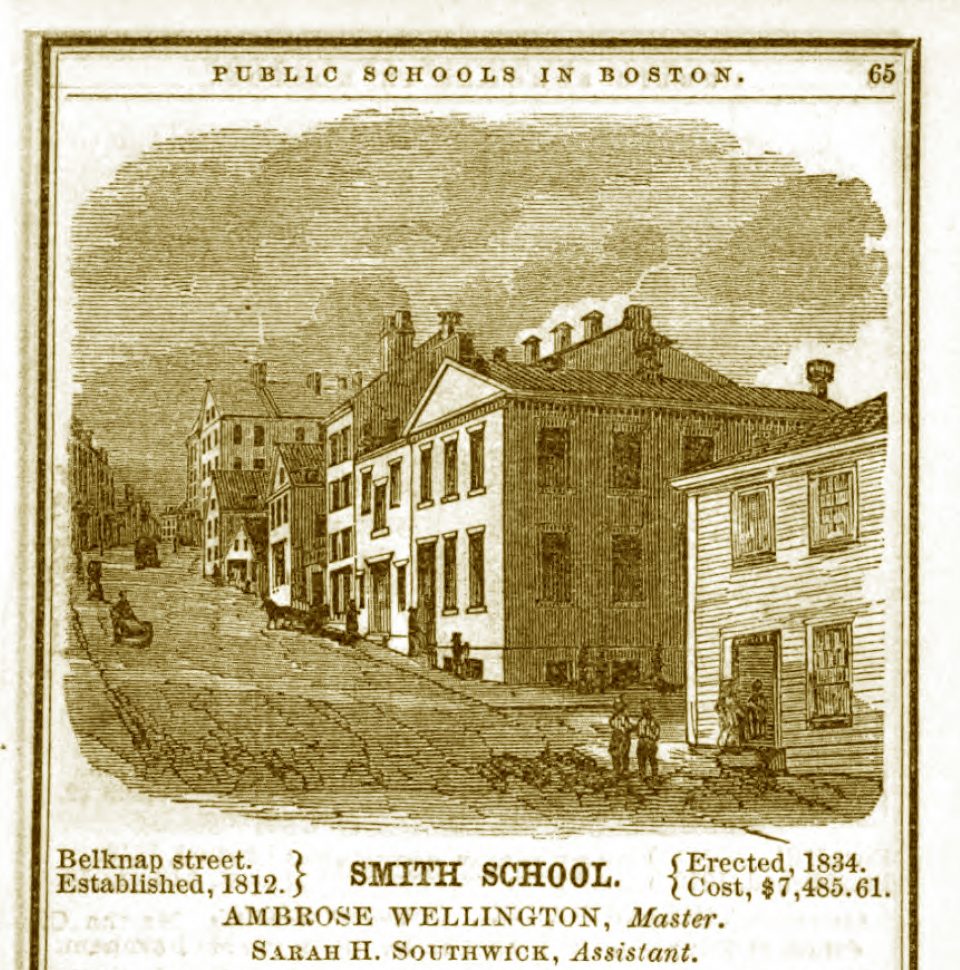

KB: That’s right. I think in the Boston case, some activists were saying that the segregated school could actually still stay open as an option in addition to the integrated school. So essentially, white children would come to what used to be the segregated school. That was actually talked about. It didn’t happen because there were people who thought there was a stigma around the segregated school that used to be in the Black neighborhood.

AA: Interesting.

KB: So it closed, and I think that actually really damaged the Black community. It’s the Smith School in Boston. I think it damaged the Black community that that was a school that closed. And it had been in existence for almost a century, so to see it closed in that way was really disruptive. And I think it was really hard as an institution, if we think about institutional power, yes, it was segregated, yes, it lacked resources. It was imperfect, but it meant something to Black children and Black families. It had a history, and that history was kind of forgotten once the school closed.

AA: Well, again, I am so grateful that you, as a historian, have done the work of bringing these stories to light and talking about these really, really important issues. Which, as we were just saying, still have relevance today. I learned so much from your work. I’m wondering if there are any last thoughts that you want to share, any final takeaways, before we wrap up the episode.

KB: One thing I would say is that there are so many great lessons that we can learn from the Equal School Rights Movement. Part of writing this book is to tell the story, but also to think about a usable past, right? How can we think about what these activists did in the past and how might we be able to carry on that work today? How might we be able to adapt some of these lessons to our present moment? I really appreciate you engaging me in conversation and having read the book, because this is exactly what I want to be able to do to connect this history to the present. So, thank you.

AA: Thank you. Again, listeners, I can’t recommend this book highly enough. It’s called In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America by Dr. Kabria Baumgartner. And Kabria, again, thanks so much for being here.

KB: Thanks, Amy. It’s been great.

We expect them to have something to contribute,

so we’re laying that foundation.

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!