“you can’t help if you can’t heal”

Amy is joined by sisters Alex Peterson and Bronwen Pugh who share the alarming data surrounding child sexual abuse before telling their own staggering story of survival and offering hope in the form of The Safe Child Project, a new initiative helping to spread awareness and to keep children safe.

Our Guests

Alex Peterson & Bronwen Pugh

Alex Peterson serves on the board of Prevent Child Abuse Utah and is the Director of Strategic Development & Impact for The Policy Project. Formerly, Alex worked for a United States Congressman before serving as the National Director of Donor Relations and personal aide to Ann Romney during Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign. Alex graduated from California State University, Long Beach, with honors, followed by an M.Ed. Policy from Harvard University. Alex and her husband Ben reside in Utah with their four children.

Bronwen Pugh lives in Marin County, CA with her husband and 3 spunky daughters. Her happy place is in nature with her family. She loves to sail, surf, paddle board, bike, rock climb, and ski/snowboard. Prior to raising her children, Bronwen received her JD from UCLA Law and worked for the ACLU. She is currently Operations Lead for Conduit Tech, a climate-focused software startup.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Patriarchy takes many different forms. Sometimes men feel the duty to protect women because they perceive women as childlike and angelic. Sometimes women defend patriarchy because they’ve been conditioned to see leadership as a male pursuit. Sometimes researchers unintentionally select male subjects or employers select male employees, not because of any animus toward women, but simply because of historical precedent and unconscious bias. But sometimes patriarchy takes a truly malevolent form, where a man uses his power, not only his physical power, but his social power to exploit and abuse people. And there is no abuse more malevolent and more harmful than the abuse of children.

Today, we’re going to talk about child abuse, and specifically child sexual abuse. So I want to start with a content warning that this is an episode that will be hard to hear. Just so you know what to expect, first we’re going to talk about the prevalence of the problem. Next, we’re going to hear two women’s stories, and they’ll be sharing the details of their stories as well as analysis about how and why this happens. And then we’ll end with an inspiring initiative to combat this pervasive problem. I want to welcome my two incredibly courageous guests today, Alex Peterson and Bronwen Pugh. Thank you for being here today. I am so grateful for your willingness to be here and share your stories with us, Bronwen and Alex.

Alex Peterson: Thank you, Amy.

Bronwen Pugh: Thank you. We’re excited to be here. Thanks for having us. No one I’d rather spend a Saturday afternoon with than my sister, who I don’t get to see as much as I would love to, and a new old friend, Amy. It was nice to meet you recently, and Alex and I have loved knowing your sister as well.

AA: That’s right, yeah, we’re talking with a pair of sisters that know me and my sister. It has been such a joy getting to know you too, Bronwen. Alex and I have known each other for a long time. I’ll just say to Alex, I remember the day I met you. Alex was a roommate of my sister Whitney, and we went over to see the apartment and you opened the door, and I just looked at you and went, “Oh, I love her. You should definitely live there, Whitney.” And you babysat my kids when they were little, and I just adore you, Alex. It’s been so great to be in touch. And yes, to meet you, Bronwen, too. I’m wondering if we can have you start off by telling us a little bit about who you are. Say your name first so that listeners can associate which name goes with which voice, but just say where you’re from, where you live now, maybe a little bit about your professional life, your personal life, and then we’ll dive in on the topic.

AP: Perfect. I’ll go first because I’m the youngest and I spent my whole childhood going last, haha. But this is Alex Peterson. I grew up partly in California, partly in Utah. I graduated from California State University, Long Beach, followed by graduate school at Harvard University, and I spent my career thus far working for a United States congressman and then on Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign. And most recently, I’ve been working at the Policy Project here in Utah. I’m married with four kids and we live in Utah County.

BP: Wonderful. I bet that felt good to go first, huh, Alex? I’m Bronwen. I’m the oldest daughter, Alex said she’s the youngest because she’s the youngest daughter. So to give a little intro, our family did grow up in Palo Alto. There were five children in the family and we were a girl sandwich. So we had three girls in the family and then an older brother who was older than all of us, and the younger brother, who was the baby of the family. Like Alex, I grew up in Palo Alto and then moved to Utah. I currently live in Northern California in a small town of 8,000 and I work for a small tech startup. I have three young daughters, and our family loves to hike, bike, surf, podcast, and really do anything outdoors.

AA: Fantastic. Thank you to both of you. We could just say that Alex went first because it’s alphabetical. I mean, it’s A and B. To not bring up sibling rivalry from the past. So let’s dive in on this topic. And I would love it if you could share an overview of statistics. How common is child abuse and child sexual abuse, and give us the breakdown of the numbers in terms of gender for victims and for perpetrators as well. I think Alex, you were going to take this one.

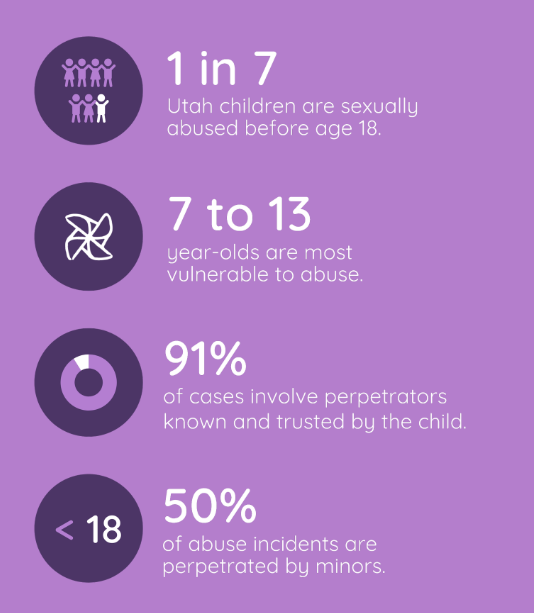

AP: Yes. Thanks, Amy. So, sexual abuse is notoriously difficult to measure. There’s no single source of data that provides a complete picture of the crime, and every state counts a little bit differently. But the most reliable sources of statistics show that about one in nine children will be sexually abused before the age of 18. Here in Utah, that number is closer to one in seven children, and that only accounts for hands-on sexual abuse. Not verbal sexual abuse or online sexual abuse, which is on the rise, but something hands-on. Children aged 7 to 13 are the most vulnerable to abuse, and in about 91% of cases, the perpetrator is known and trusted to the child and likely to the family as well. Half of those cases are also perpetrated by juveniles, so that means that someone under the age of 18 sexually abusing someone else under the age of 18. We also know that about half of survivors of child sexual abuse are sexually revictimized in adulthood. For example, one study showed that 87% of sexually trafficked victims had experienced child sexual abuse prior to being trafficked. And it’s such a common factor in so many of society’s largest problems. We see a correlation with child sexual abuse and higher rates of suicide, incarceration, school dropout rate, substance abuse, poor mental health, the list goes on and on.

And then, of course, we also probably all know somebody that’s been sexually abused and hasn’t reported it, so these numbers are likely very low across the board. As far as gender dynamics, in about 80 to 90% of reported sexual abuse cases the victims are girls as opposed to boys. And between 10 and 20% of the time, the perpetrator is female as opposed to male. There is some evidence to suggest that sexual abuse by females is severely underreported due to societal and cultural perceptions about gender and sexuality. So, that just gives a little bit of a snapshot in the picture. And then we could talk about assault as well. Those rates are also staggering, and Utah has a lot of work to do with adult sexual assault and domestic violence.

AA: Could you share a little bit of those statistics if you have them, Alex?

AP: Yes. Utah has a disproportionately high rate of sexual assault compared to the national average. The latest research I saw showed that our rape rate is 55.5 people per 100,000, whereas nationally it’s 42.6 per 100,000. And then as far as broad sexual assault and not just rape specifically, it’s projected one in three Utah women will become a victim of sexual assault in their lifetime. And that’s a rate that’s notably higher than the national average. I also just saw a study from the FBI that showed that rape is the only violent crime in Utah that’s higher than the national average. Our other violent crimes are all lower than other states.

AA: As I’m hearing those statistics, I mean, I live in Utah now, as you do, Alex. I used to live in Northern California, like you do currently, Bronwen. I know, Alex, you did too, that’s where we met. My next question, and a lot of listeners are going to be saying… Why? Why on earth? And people who associate Utah with the dominant religion in the state, and that religion, at least in my experience, tends to be very pro-family and talks a lot about the evil of child abuse. That’s something that is talked about. But why on earth would this be happening more here? I don’t know that any of the three of us know this, and I’m sure it’s being studied, but it’s very, very concerning. But it happens everywhere, right? I mean, this is something that has always happened and has always happened everywhere.

AP: One thing that I just thought of is that the Child Protective Services group under the Department of Health and Human Services here in Utah does say that they are unique in that they count all incidents, whether the perpetrator lives outside the home or inside the home, and some other states don’t count that way. Some also might say that the fact that we have higher reporting could be a sign that in Utah we take this really seriously. Reporting doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a higher rate of incidents. We also know that we do have really close-knit family and community structures, and so there may be access to children and trust with our children in a way that there isn’t in other states.

AA: Hmm, that’s interesting. Thank you so much, Alex, for providing that little bit of analysis that there’s not really an apples to apples, one state to another in reporting. That’s really important to remember. What you said about the big families and lots of kids around reminds me anecdotally of multiple of the stories of sexual abuse that have happened in my extended family, which happened because it was kind of an environment of free-range parenting of kids out playing at different people’s houses. And there was so much trust in neighborhoods or in rural communities where kids go from house to house, and some terrible abuse happened to some of my family members because of that. That would be another interesting way to study it, is different kinds of cultures within states of lots of kids running around on their own with that free-range parenting. There’s so much analysis that I’m sure has been done and that we could do, but I’m wondering if we can now move along to your stories and have you talk about the shape that this took in your lives as your stories, which particular to you, but there are some themes that we’ll talk about that are kind of emblematic of some of the things that are common in abuse cases. So you can choose who goes first now, Alex or Bronwen, and just tell us what happened.

BP: I think it’s actually really interesting to talk about the statistics, and we were trying to dig up some statistics as we were preparing for the podcast. And what really struck me over and over again looking at the statistics is that while we do have a little bit of information, first of all, of course, it’s not apples to apples. And secondly, my strong feeling as a survivor is that there are huge gaps in the information to the point that this information is almost useless, really. Based on so many disincentives to report and, like Alex said, a lack of consistency and continuity in how we’re reporting. It just opens the door for so much speculation as to what this means, you know, does this particular state have really worse rates of abuse or does it mean it’s actually better and we’re more protective and we’re more comfortable reporting and there’s more trust in the community? It’s really possible to go any way because this is such sparse and gappy data.

one in nine children will be sexually abused before the age of 18

It also really struck me thinking about the statistics that you can’t improve what you can’t measure, and that there are a lot of areas for improvement here in reporting. And entities who have data, making that data publicly available and just realizing that there’s a lot that we probably can’t help in this situation, which has a lot to do with the victim. And when they are being abused, the lack of likelihood that they would feel safe reporting, that they would have the ability to report, and just the psychology behind it, where victims are very much self-blaming. Alex and I have experienced that. So, just a couple of comments and thoughts on those statistics.

AP: I was also going to say that. The CDC, Center for Disease Control, didn’t acknowledge child sexual abuse as a massive problem and as a public health crisis until the ‘90s, is my understanding. So it’s actually pretty nascent in that regard. For how long have we considered other issues problematic, and this one is still relatively new on the radar.

BP: Right. The data I saw was very new data, only started being measured really in the last handful of years. It’s really interesting. I want to set the stage with a couple of things. Number one, we’re going to talk about some hard things, some emotional things and relating to the subject of patriarchy, whether it’s patriarchy in families and communities and religion, as a subset of that abuse within patriarchies and child sexual abuse within patriarchies. And all three of us have had different experiences. In relation to that, and we’ve made different life choices, I want to acknowledge that this applies probably to many if not all members of your audience, Amy, who have all had such different and individual experiences here. I want to start by acknowledging the common ground that all three of us, likely everyone in the audience, can probably agree that our driving goal around the topic should be the protection of children, and adults as well, from sex abuse. It’s a wonderful goal. There aren’t many things in life that everybody can agree on, and I actually think this is one that pretty much everyone can probably agree on. We should be protecting children from child sexual abuse. Of course, when you dig into it just a little bit, it turns out to be very complex. But we ask that we open-heartedly acknowledge that we’re all coming in with our own experiences and feelings about this, and approaching the topic with some grace around that and the acknowledgement that we all want the same thing.

AA: Thanks so much for saying that, Bronwen. Yeah, I couldn’t agree more. And then whichever one of you wants to start, you can just dive in.

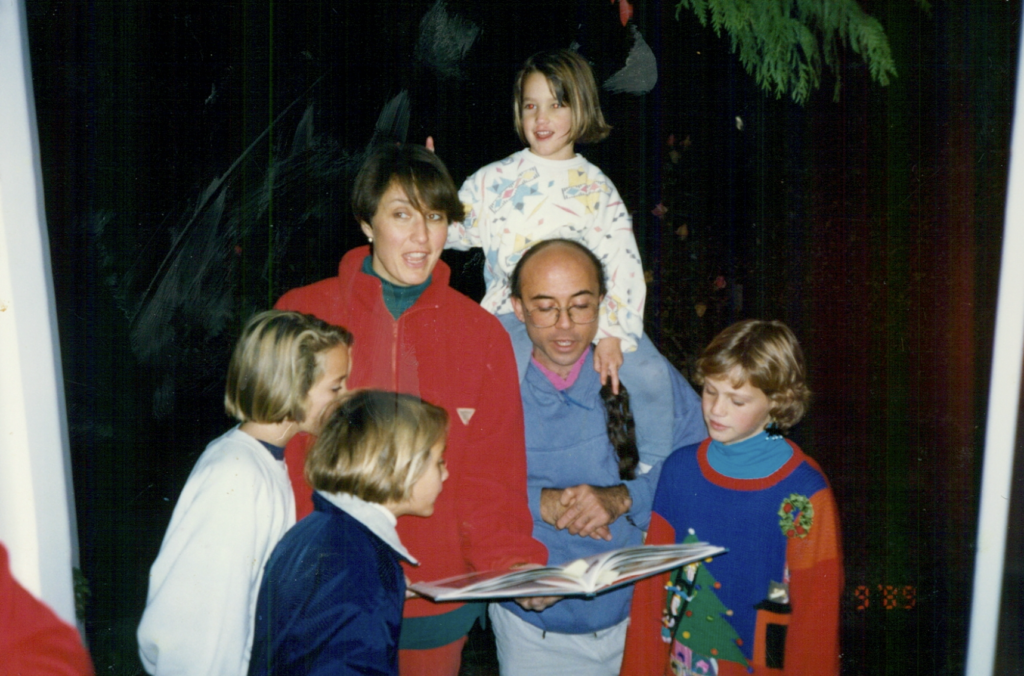

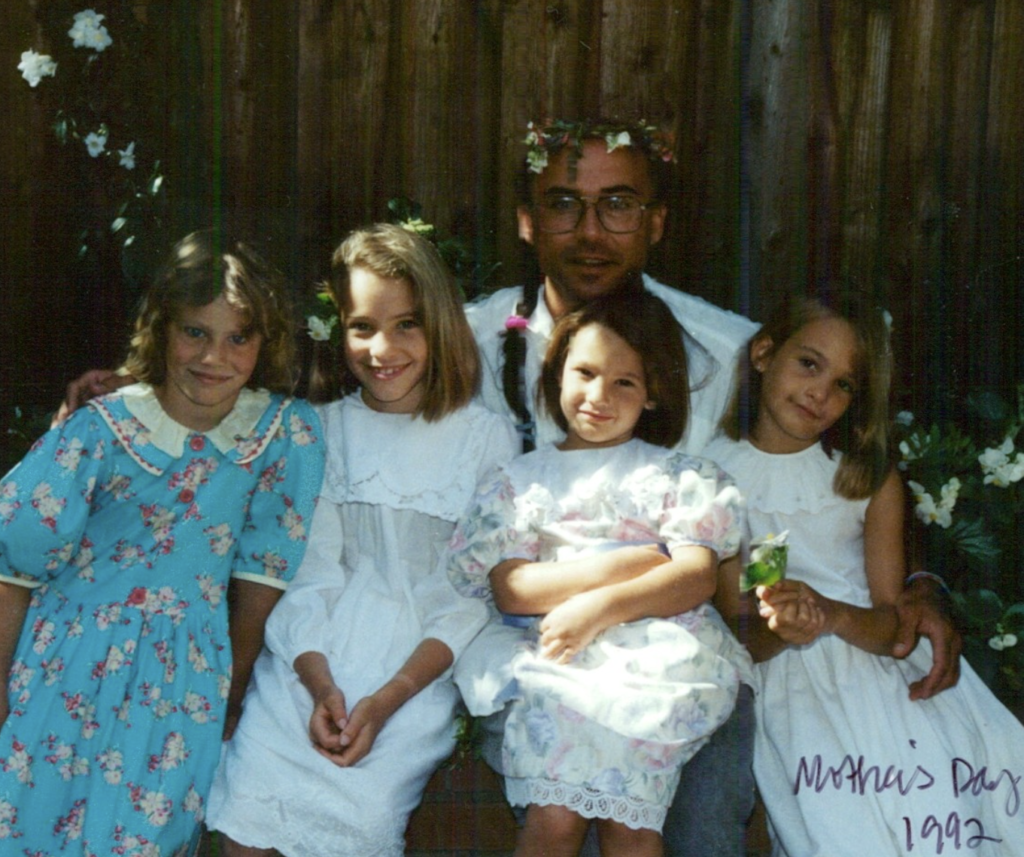

BP: Oh, now the oldest one goes first. Okay. We’ll just tell a story about what happened and really get into as many details as we like, or we can just kind of skim over some things, but just to get started to give some context and paint the picture. Alex and I lived in a nice town, a nice neighborhood, we were growing up in the ‘80s and the early ‘90s in Palo Alto, California. In our family, and just as a disclaimer, I’m going to be telling the story from my perspective, which is quite different from Alex’s perspective because there’s a four year gap between us. Which at the very young ages that we’re talking about, this particular abuse started when I was seven and Alex, you were three or four. So developmentally it was quite a big gap. And then based on birth order and all the nuances of being in a family, we approach this quite differently and are oriented quite differently. What I’m saying is really just for me.

From my perspective, the three most important influences in our family of origin were number one, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Both of our parents were members, and we went to church every week. Another big influence was multigenerational patterns of abuse of all kinds, and some undiagnosed mental illness sprinkled in there. So kind of a little petri dish for abuse in that way. And then the third thing, which was mostly driven by our mother, was a really strong desire for approval from our community. So how we experienced this abuse through the lens of our family, we were in an environment that from my perspective was really a caricature of many of the worst parts of structural patriarchy. And Alex, I’d love to hear your perspective and feel free to just jump into the narrative on what happened.

AP: I will, thank you. I mean, I will if I feel the need to, but keep going. Haha!

BP: Okay, haha, that was funny. I was seven when all this started. I was in second grade, and we went to a nice public school, and I had my friends and probably had a really normal life of a typical second grader. And one day we met this man named Tupou, and I don’t remember the first time I met him, but I remember suddenly he was just around a lot. And then our parents told us that he was going to be moving in with us. So he moved into our basement at the time that Alex was three or four, so she was in preschool. And I believe the reason was that, well, I know for sure that both of our parents were very involved in our church community. My mother was a cub scout leader and she was a Young Women’s president, and there were a lot of things going on. So she had a lot of commitments through church. My dad was always at work. He worked as a general contractor and he was gone most of the time. And my mom needed to go back to work and she was actually going to work from home doing bookkeeping for my dad. This was in a situation where they were struggling financially, and she felt compelled to go back to work in order to improve their financial situation.

So Tupou moved into our basement. He was a member of our church. My mom was kind, she was pretty, she had a very much “I will be nice at all costs” kind of MO. She was very much liked by everybody she met. And my mom trusted Tupou because he was a member. She believed that because he held the priesthood in our church, he would bless our family. Particularly, my mom didn’t feel that my dad was necessarily an upstanding holder of this priesthood, and so she adopted this man, and he was presented to us as “this is going to be your surrogate father” in a lot of ways. When Tupou moved in, he declined to disclose his last name. No resume, no referrals. Tupou was not being paid to watch us. He watched us in exchange for us giving him free housing. My parents knew, and we knew as children, that Tupou had been excommunicated from the Church of Jesus Christ for some reason, it had to do with a girl. My mom knew that and we knew that. It was a young girl, but we didn’t know the details, and we still don’t. We haven’t been able to get those details despite efforts. But we do know that there was this little girl in Southern California where Tupou lived previously, in the Long Beach area, I believe, who was a member of his congregation. We later found out that he groomed her, and ended up sexually abusing her over many years, although we didn’t know the details at the time. So we moved really quickly after hiring Tupou, we moved to another house across town and Tupou moved with us. So he went from living in our basement to living in the detached garage of our new house. And in the back of the garage was this teeny tiny bedroom. Actually, Alex and I went to visit this house. What was that Alex, two years ago?

AP: Yeah.

BP: And it was really amazing how tiny it is. It was completely jimmy rigged. Maybe our dad built it, he was a contractor. Do you know, Alex, if dad built that house?

AP: Yeah, I think so.

BP: For some reason, you take a typical detached garage and literally somebody had just built a closet sized mini apartment. It had one bedroom and this tiny kitchenette and a teeny tiny bathroom, really just enough to maintain human life. And it was really dark and there was no room for anything in the bedroom except for a bed and a TV. So that’s where Tupou lived. My mom at this point was working as a bookkeeper in the basement of the main house, and so our job when we came home from school was to go into the back cottage where Tupou lived and to stay there until dinner time. At that point, we would go into the main house. Oftentimes when our parents had obligations at church or elsewhere, Tupou would come into the main house and make us dinner. So that was the basic setup. And Alex, I would love for you to jump in here and keep going if you’d like to, but your face is telling me you don’t want to.

AP: No, no, you’re doing a great job. I mean, obviously I experienced a lot of this differently, but I think you’re capturing the broad strokes. Do you want me to fill in any specific detail?

BP: No, totally up to you. Feel free to take it from here, I just don’t want to dominate.

AP: No, keep going. This is great.

BP: Okay, cool. So from the moment that Tupou met us, he completely ignored our two brothers and he got right to work grooming us three girls. He showed a tremendous amount of interest in us. I remember my first conversations with him were him just saying, “Oh, you’re so beautiful. I’m so lucky to be a nanny to three beautiful little girls.” And so he got straight to work playing games with us. And this developed over time. It started as really fun physical contact intensive games. But over time, as we resisted playing his games, then he would start to bribe us with candy or with television. And if we still resisted, especially as time progressed, he would resort to using threats, fear, and force. The beginning was lots of games to introduce deliberately ambiguous sexual contact. The games were focused on playing pretend, and at first they seemed fun. He would ask us to pretend to be models and seduce him. That was a new word for us. So he would teach us how we were supposed to walk and kiss him and move our hips, and what we were supposed to do to seduce him. When we were pretending to be models, he would take pictures of us in various states of undress. He would ask us to take off all our clothes and paint our naked bodies with fun, bright colored paints, and take pictures and paint all of the parts of our bodies, including our private parts.

One of his most common games was wrestling. Tupou was always trying to wrestle us. And as he did, he would rub his genitals against our bodies and his face would turn red and he would have a smile of pleasure across his face. I had no concept of sexuality at the time, but I knew I strongly disliked the experience as a seven year old, so I avoided it. But Alex is teeny tiny and Alex was small enough that he could literally just pick her up and rub her body wherever he wanted. So he would do that and he would also reassure us because I was feeling very uncomfortable about this. And he would say, “Oh no, we’re just wrestling and there’s nothing wrong going on here.” And then the contact became a little, it had a little edge of maybe coercion going on. The physical touch and the rubbing, he started to introduce domination and control.

The first way that I experienced that was constant full body tickling, including bottoms, chest, thighs. And I remember he would never stop when we told him to stop, no matter how much we begged. He would often force me into a locked room, tickle me all over against my will, put his tongue in my ears, suck on my toes, just gross, unpleasant stuff and he just refused to let me go. He would make us pretend that we were grownups playing sex on the bed with him. It became more and more about overt domination. And again, Amy, this is a podcast about patriarchy, and I know that domination is an important theme in that. And I can’t speak to that other than his ability to control us, which was clearly quite important to him, and he was really getting a lot out of that. Alex and I both remember him holding our baby brother out a window and threatening to drop him until we, I don’t know, whatever he wanted us to do at the time, kisses or contact. Do you remember, Alex?

AP: Yeah, I think that night it involved touching and kissing his genitals in increasing levels of severity, right?

BP: That sounds right. Yeah. I remember being woken up many times to him French kissing me while I slept. After school, we would play these coercive games of strip poker, where you had to play, and you couldn’t just take off your watch, you had to take off all your clothes. And I remember at sleepovers that he was always really into our friends and our girlfriends. He would knock on the windows of the main house while I had girl sleepovers with my friends, trying to scare us. He was really enjoying, I think, the scary part of it and demanding to be let in and to play at the sleepovers with us. And he also enjoyed the secretive part of it, you know, instructing girls not to tell their parents. He also would punish me, and he enjoyed that as well. If I didn’t keep his secrets or do what he wanted, he’d tell on me, pack raw eggs in my lunch instead of hard boiled eggs, or pour hot sauce on my sandwiches and various forms of weird punishment. He would cultivate trust and try to gain the trust of children.

He would invite us to braid and accessorize his hair, he had a long ponytail and he always had these fun ponytail accessories that were brightly colored little butterfly clips. He’d put them in his hair and he would always happily participate in our kid games. So there was this element of like, “Wow, this guy’s really fun.” And all our friends thought he was really fun too. He went out of his way to be fun. He was volunteering at, I believe, five or six different kindergarten classrooms in the public school district and he was involved in the community in every way. He would do summer camps at the JCC, like summer art camps, and he was an after-school language tutor, and really seemed to be everywhere. All the kids in the community knew him and liked him. He could kick a ball sky high. And we didn’t know any adults who really liked to play with kids in a kid way. He was the clown. I mean literally, he had these red clown clothes that he would, I think–

AP: Yeah, he would go to birthday parties and work as a clown. I think, to your point, Bronwen, everything in this individual’s life was designed to lure children. He rode a tricycle, he rode a skateboard, he developed these juggling tricks and he could throw M&Ms into the air and you’d call out a color and he’d catch it in his mouth. He’d show up at a park or a playground and within two minutes he’d be surrounded by children just because of the charisma that he had developed and spent hours and hours and hours orienting these tricks to draw children to him.

BP: Yeah, back in those days, we had school sleepovers. I don’t think we do that anymore, I think we kind of figured that one out. That was a thing, and he was the clown at the school sleepover and was really into that. So yeah, lots of little details there. And then developing secrecy. He would give us candy when we weren’t supposed to have it, or let us watch TV when we’re not supposed to. And he would always insist it’s a special treatment. It’s our secret. He would say, “If you tell the secret, I won’t be able to do this for you anymore.” So he was intentionally conditioning us to never tell. He was also normalizing sexual conversation. The first time I ever heard the word virginity he was trying to get me to promise to lose my virginity to him if I lost a bet that we made or in exchange for a special outing. He told us girls that he didn’t like vagina hair, but he would prefer a clean vagina like mine and my sister’s. He would constantly knock on the door when I was taking a bath and badger me to open up so he could help me soap up my hard-to-reach spot. And he would talk about this girl in Long Beach who he had a relationship with before he became our nanny, and how that was a great relationship, and I believe conditioning us to do the same. He talked constantly about our friends wanting to kiss little girls. He explicitly had crushes on some of our friends, talked about how beautiful they were, and would try and convince us to invite them over for a play date. He would talk about how much he wanted to kiss their lips. He would make up these like weird songs, slightly sexual songs about particular friends.

And then he started introducing sexual exposure. Anytime we went into his cottage, which was his teeny apartment in the garage, there would be Barbies in pairs or in threesomes in sexual positions, and they would be oftentimes tied up. And again, just going with the theme of domination, coercion, and we can explore how that relates to patriarchy, but he would tell us that they were playing and having fun. He would tell us that we were lucky because we got to watch adult movies with him, and we didn’t tell our parents, so he would have us watch pornographic movies with him. And he would actually pause the movies and explain the different parts, you know, what is an orgasm, talk about how good it feels and what an orgy is, and explain the sexual content in detail. He would take us on outings to adult entertainment and sex toy shops, have us play with the toys, watch us very carefully and ask us if we would like to play with them or have him buy one for us. Whenever our parents weren’t around and we were in his cottage, he would take off all his clothes that he would typically just be wearing underwear only and explained how that helped him feel most comfortable. So you could tell how this was just slowly amping up over a period of years. He was living in our home for four years. Is that right, Alex?

AP: Yeah. So after four years, we ended up needing to move out of state, you know, economically it just wasn’t viable to continue living in California. And as Bronwen had said, the abuse had just continued to escalate and escalate over those years. And then we moved to Utah, but we came back to visit every summer. And at one point our parents flew him out to Utah to stay and invited him to come and volunteer in my elementary school in Utah. And then we would go back to California and sometimes we would be left to stay alone with him in his apartment for days on end. And then one day just happened to be the last time we ever heard from him, and we never heard from him again. Obviously, we were thrilled as children to never hear from him again. And so we never really asked why, we just kind of hoped this horrible chapter of our life would recede into the background. Is that the right way to capture that, Bronwen, that transition from California to Utah?

BP: Absolutely. We were really skipping over the worst of the abuse towards the end of when he was living with us. What I can say about that is that I’m not really aware of a lot of what happened during that stage because I had not been a good pupil, you know? I really strongly disliked him. I would go for days and weeks without talking to him. Alex and I had brought this to the attention of my mother, our parents, and time after time it was clear that our mother wasn’t interested. She didn’t want to be bothered with this. I would oftentimes be exhorted to not bother Tupou, not upset him, stop making him angry, and why can’t I get along with him? And so because of that, Tupou did a lot of stuff that I really had no idea about to my younger sisters who were just younger and who weren’t as developmentally aware and not able to say no. And unfortunately they were just more vulnerable to being coerced. So Alex, if you want to talk about that, that’s fine. All that grooming really did lead to some pretty serious sexual abuse, unfortunately. And then, like Alex said, after the community found out, there was a community scandal. Our family moved to Utah, I believe in part due to that community scandal. And yes, Tupou did continue to have contact with us for years, and then one day he just disappeared. So we can get as much into any of that as you guys would like.

AA: This is just harrowing to listen to, and I do want to say how grateful I am for your courage in talking about this. I think it’s so, so important to talk about it. Because I think, and you would know best of all, but that sometimes the shame and the stigma keeps people from talking about it and from reporting it. So I think the more people are able to openly talk about it, it de-stigmatizes it, it removes the blame from the victims to say “I don’t have anything to be ashamed of here. This is not anything I did wrong.” To be able to speak openly and freely, I’m very, very grateful for that. As I’m listening to this story, and I’m guessing that listeners who are hearing this are going like, Where were your parents? How was this happening right under their noses in the basement of the house or just out in the garage when you said your mom is working at home? How in the world is this happening under their noses, and then what happened when you tried to tell them? And then you just mentioned a community scandal. So if you can talk about that piece of you telling them, trying to report to your parents, and then how did the information get out into the community?

AP: To a large extent, Amy, this was not happening under our parents’ noses, it was happening in front of their faces. And it’s something that I think I will never fully understand, but I have tried. And I think what I’ve come to understand is that parents cannot give what they don’t have to share. And our parents excelled in many ways, and we had so many protective factors and positive childhood experiences, but our parents didn’t have the ability to nurture or protect and guide in some really fundamental ways. And I think this abuse, they knew it was happening, but they didn’t believe it was illegal or immoral.

AA: How? How did they not think it was? Did they not understand that it was harming you? Did they not know the extent that was happening or did they maybe… I can understand they didn’t understand it was illegal, but that wouldn’t be the driving factor I think for many parents. They wouldn’t care whether it was legal or not, they would know that it was harming their child. They didn’t see the harm in it?

BP: Exactly. The way it was described to me, I remember as a child when I would make these complaints is, “Bronwen, why can’t you get along?” And I think that comes a lot from a background of abuse. And from my perspective, also from a background of church patriarchy and community patriarchy. I’m not talking about our community in Palo Alto necessarily, but really just our cultural patriarchy, which I think we had more of a cultural patriarchy during the early ‘80s even than we do today. At least I see it that way. The way it was described to me was also, “Well, you don’t like going to the dentist, so don’t complain about it.” And I think the undertone there was getting sexually abused by men is like going to the dentist. It’s a part of life and it’s uncomfortable, but this is something that men need and we just are going to have to roll with it. And you could complain about it and you can make a scene, or you could just accept that this is part of our job as women is to take this kind of abuse. And I don’t think she would have ever have thought of it as abuse, to be honest.

AP: I do remember my mom saying things like, “That’s how men are”, or “If you don’t like it, then just run away or tell him to stop.” And actually I think that’s part of what has been so difficult to metabolize as an adult, because the abuse for me started at such a young age and was so incredibly normalized. It wasn’t as horrifying or scary in the moment as it might have been if it happened one time when I was 13 and I had no idea what was happening, right? But I think one of the most difficult things is trying to understand how the abuse was contextualized. Or not contextualized to some degree, right? I was led to believe that it was so normal. It actually wasn’t until I was an adult that I understood that what happened to me was illegal and was immoral, and that there actually could be a criminal case. That was decades before I came to understand that, Amy.

BP: Yeah, just to add a little more color on this, I think a lot of the way that my mom saw this was through a lens of unilateral forgiveness, you know? Just for anything that men do, which I think she felt was part of her religious duty. And then also just a culture of men making the decisions and whatever men decide is the right thing.

AP: Yeah, and I think we’d have to have our parents on here to fully understand their relationship to that period of time as well. But I have a bit of understanding and context on their upbringings. I mean, they both grew up in extremely dysfunctional homes. My mom has said that as a girl in her family, at best you were ignored, at worst you were vocally denigrated and physically abused with things thrown at you. It was an extremely vulgar environment. She recalls pornographic magazines being displayed around the home really casually. So women were not respected in any way, shape, or form. And her parents were both alcoholics and had a pretty dysfunctional relationship, so I think she just never really developed judgment and grew up most comfortable in an environment with abusive men.

BP: Yeah. And I think that led to the situation where when we told her about this and, you know, the best way that children can, which I’ll completely own as a seven year old, like I might’ve done a terrible job. I probably did. But I continued to bring this to my mom, which is why Tupou ended up trying to do a lot of this behind my back. He knew that he needed to worry about me and he knew he didn’t need to worry about our mom. So it led to this environment where it’s not that my mom didn’t know, it’s that she wouldn’t know. And that green-lighted for Tupou, and he started to amplify his predation. It was more brazen over time, and he was happy to do it right in front of our mother. She would take the pornographic pictures that Tupou took of us and put them in our childhood photo album.

AA: I know from reading the reports that there were other adults who became aware of the abuse and that somehow, I believe, both of you ended up being called into the counselor’s office at school. And this was investigated by police, is that right? How did that happen?

AP: Yes, that’s right, Amy. In 1995, the abuse had just become so normalized and so expected, even though we were told it was a secret, it was just a normal part of everyday life. The story goes that a playmate, when I was in second grade, she wanted to come over and play. And I said, “You’re absolutely welcome to come play. I’d love it. But you’re going to have to take off all of your clothes and we’re going to have to play strip poker with our live-in babysitter.” And for her, that was atypical. So she said, “I’m absolutely not coming over.” And she told her parents, who then called the police. This did lead to a criminal investigation that was brief and short-lived. Tupou was a volunteer in our school, and in many different schools, and so this became a little bit of a sensational story in the community, and one that my family was very interested in controlling the message on. Bronwen, you can take that from here. I feel like you understand the legal portion better.

BP: Yeah, so various adults had been concerned and voicing their concern from the beginning. I remember I was probably eight when I started to hear that new word, “pedophile”, kind of whispered around quite a lot and talking about Tupou. These complaints were occasionally brought to our parents, and our parents would ignore the complaints and ask whoever was voicing the concern to not share those concerns around. And it really invokes the fact that this is an innocent man and that he’s being targeted simply because he is somebody who likes to spend time with children who’s a male and that this could ruin his life. After this particular complaint was made, and this is really, in my opinion, one of the saddest parts of this story and a side story, is that this little girl, who was invited over by Alex, and who had decided to tell her parents what had happened, her parents asked her if she would be comfortable testifying on our behalf in court. And this was a seven year-old at the time, and this brave little girl decided that she would be willing to do that for her friends.

At the same time, there was a bit of an investigation made and I remember sitting down at the kitchen table eating dinner with my sisters, my mom, and Tupou, who was really like our surrogate father. I could tell that my mom was agitated and defensive about something, and she had been for a few days. She had been on the phone. And during this conversation I was told that investigators would be coming to my school the next day in order to ask some questions about Tupou. And my mom said, “Tupou is family, and we protect family. And you are to tell whoever asks you that there’s been no abuse and that nothing has happened and Tupou has done nothing wrong.” My mom explained Tupou is innocent and there’s some misinformed community members who would really like to put him in jail because he’s a male who enjoys playing with children. And that this is a matter of loyalty to the family, it’s imperative that you let everybody know that this is an innocent man and that nothing ever happened. So, I believed them. I felt scared for their safety, my mom’s safety, who was clearly distressed, Tupou’s safety. I was 12 at the time. I believed I should protect my mom and Tupoufrom these bad people. And so the next day I went to school, I was questioned by a male investigator, at the beginning of sixth grade, and I lied and I told him Tupou had done nothing wrong. And in that moment, I actually believed I was telling the truth because I had been told over and over again that there’s nothing wrong with what’s happening here.

I had no ability to connect these daily behaviors to the word abuse or to really any inkling that anything was wrong. And that was really my mom’s honest perspective, that while this may be happening, there’s nothing wrong here. I had really absorbed that feeling and really the domination was so complete. I’d been so conditioned to disbelieve my own feelings and just believe whatever they told me and it just felt like a daily dentist appointment. You go and it’s uncomfortable and just part of being a kid, and it just sucks. But why complain? I think that was really a pinnacle where I did something and at the time I didn’t feel bad about it, but that’s a guilt that I’ve really carried with me throughout my entire life. And that feeling that I let my sisters down and that I let the community down.

And another person I let down without even knowing it was this little girl who was willing to defend us in court, because what happened next was that the investigation was shut down because my sisters and I were not allowed to testify. My mom let the investigator know that we would not be allowed to testify in court and that she was doing that in order to protect us from having to testify in court against our nanny who we loved. And this little girl was actually maligned. I don’t think that my mother did this intentionally wanting to hurt this little girl, but there was this girl and then another woman in particular who had been very vocal about saying that Tupou is a volunteer in this woman’s daughter’s kindergarten class. And this woman just said, like, “I’ve seen him playing with the kids, I’ve seen him playing on the playground. I haven’t seen anything illegal, but there is something seriously wrong here.”

And so these two characters, this little seven year-old girl who was willing to stand up for her friends, and then this woman who actually herself had been a victim of child sex abuse and really just had an antenna and knew exactly what she was seeing. They were the most vocal opponents of Tupou. And our mom really went to town. She wrote an editorial to the local newspaper defending him and indirectly, without stating any names, calling the people who were accusing him, calling them misinformed and whatever else. She also went around and passed a petition around the community asking that the criminal investigation be dropped. So after all this agitation in the community and the fact that we couldn’t testify, the case was closed.

I had been told over and over again that there’s nothing wrong with what’s happening here.

AP: And Amy, we’ve actually since learned that the detective who investigated our case, he was assigned to sex crimes. Within four years, he was actually arrested and dismissed for sexually abusing four other women who were in the back of his police car, or who he had been investigating. He was sexually abusing them. So it’s really a whole community with some problems here.

AA: I read the report of whichever detective interviewed you both in your school. That was him?

AP: Yes. Luis Berbera. In 1999 he was charged and sentenced.

BP: And he had also interviewed Tupou during that investigation, not only was he sent to our school, but he also interviewed Tupou. And as an adult, for me reading the transcript from that interview, it is clear as day that Tupou was somebody who needs further investigation. Even Tupou’s way of talking about his relationship with us children was extremely disturbing but completely overlooked. The whole community was rocked and this woman and this little girl who had stood up for us and were really interested in our safety as children and the safety of the entire community, they ended up for years with a lot of pain and a lot of hurt. And this little girl, it really had impacted her entire life in a profound way, that as a little girl, from her perspective it felt like an entire community turned on her and accused her for years and years of trying to put an innocent man in jail.

AA: Oh my gosh. To be accused of lying, right? Just outright lying because it’s one person’s word against another.

BP: Yeah, and like, “You have a dark mind. Why would you make this stuff up?” And that’s something that I think Alex and I are interested in speaking to in our story. First of all, just to de-stigmatize, and secondly, I think that’s actually another common theme. There’s almost these conflicting currents of like, “If you’re a child and you’ve seen something, or you saw something happen to your friend, you should report.” But then this conflicting current of, “Don’t mess with this adult stuff. You’re going to get somebody innocent put in jail.” I think we have conflicting interests in protecting innocent people. Oftentimes men, but also protecting children. And again, this is just getting into some of the nuance and complexity around these situations, and we certainly experienced that nuance in our community during this time.

AA: So you have this woman in the community who saw him interacting with kids on the playground and had the antenna and said, “I know there’s something wrong and bad here.” You have a little bit of stirring within the community. Was he abusing any other children? He had access to so many children. Do you know if he had other victims at the time?

BP: We don’t know. I would not be at all surprised if there were other victims, but we don’t know that. He was put in jail during that investigation, and the reason he went to jail briefly was because our other sister leaked something. She was told not to, but she accidentally leaked something very small. And based on just that, he did go to jail. At that point, he was released on bail. My mom and another family whose daughters were close to Tupou raised the bail money and bailed him out of jail. And then the charges were dropped, although what was left was a restraining order. There was a requirement that Tupou receive counseling regarding appropriate behaviors around children, and a restraining order that he wasn’t allowed to be within however many feet of us. He wasn’t allowed to have contact with us anymore, although that was completely disregarded. He came immediately back to live with us and he did live with us for quite a while after coming out of jail before we moved to Utah. And then again, our parents really fostered that relationship and went out of their way to continue having him come to Utah and us to go to California. And as Alex said, we spent quite a lot of time with him after that until he did disappear.

AA: So his next victim, it was after you had gone to Utah, is that right?

AP: Yeah. Yeah, we haven’t totally gotten into what was going on with our family, but it was an extremely tumultuous time. My dad’s business was failing, my mom had another baby and she wasn’t sleeping. I remember her crying in the corner a lot. It seemed like everything with Tupou was coming to a head, so it just felt like this pressure cooker that was about to blow. We ended up needing to move to Utah, and as we now know, right after we moved to Utah, Tupou moved out into an apartment. And he met a child who lived in the apartment complex and he started abusing that child for years and years. He eventually was caught abusing that child out in public and was arrested and was put in jail. At that point, we never heard from Tupou again for many years.

AA: Okay, so that was when he disappeared. From your perception, you had no idea that that had happened, but he had another victim that spoke up. How was he caught at that point? Did she tell authorities?

AP: Amy, we now know that after we moved to Utah, this pedophile, Tupou, moved into an apartment, and in the same complex there was a young girl that he started a sexual relationship with and introduced her to drugs and all kinds of abuse. That went on for years and years, but eventually he was caught while abusing her out in public and he was charged on 50 counts and sentenced to over 60 years in prison. Once he was imprisoned, we never heard from him again. We didn’t know why, we just knew he was no longer calling and leaving menacing voice messages on our machine, and my mom stopped talking about him.

BP: On our end, really, it was just crystal clear that this is something we don’t talk about ever. My sisters and I remained, really for me it felt like paralyzed fear for years, that this is not something we’re ever to speak of or address. We never told anyone what happened. My mom never spoke about the community scandal ever again, and my sisters and I were really trying as hard as we could to forget everything that had happened. Even though I try not to think about it, I was still terrified that Tupou was going to come find me and take my virginity, just like he promised he would. So, fast forward to when we’re young adults, and Alex, you’re going to have to take this one because you’re responsible for all the adult piece.

AP: Yeah. Like Bronwen said, this was something that haunted us for years and years and years, but we didn’t know that it was wrong. We didn’t know that it was illegal. We didn’t even know that we were allowed to feel uncomfortable about it. So it just felt like it was slowly eating away at us, and this really came to a head for me.

AA: I want to ask, if it’s okay for me to interrupt you here, even if you didn’t know cognitively, if you hadn’t been told that it was wrong, that it was illegal or immoral, I imagine you had emotional, somatic responses to what had happened. Not only the sexual abuse, but also the silencing. Did you have symptoms that were disruptive in your lives in between that time?

BP: Well, I can only speak for myself. My experience of this was entirely that. I was the oldest, it was my job to protect my sisters and keep them safe and make them happy. And that I was literally powerless to do that, that my one chance that I had to do that, I failed, which was when that investigator came to my school. So a lot of my somatic issues have actually been around listening and speaking. We could talk about somatic issues in childhood and then while processing as an adult. The most acute for me I’ve actually felt recently. After this was all concluded at this sentencing hearing, Alex had pressed charges, brought Tupou to court, and he was sentenced for yet another equivalent to a life sentence. And we had the ability to deliver victim impact statements, which I’m so glad they exist, they’re extremely powerful and really the one chance in the court proceedings where the victim gets a blank slate and they get to say whatever they want without being cross examined. It was an extremely empowering experience. We all got to do that. And this one, was it 2022, Alex? It was just a couple of years ago.

AP: Yes, it was around 2022.

BP: For me, after delivering my victim impact statement to Tupou, I asked the judge for permission to face my mother. I was given permission and I basically told my mom something along the lines of, “You knew. I told you and you knew. You didn’t listen to me.” And while saying that, I felt my ears start to pop and something weird, like when you’re in an airplane and your ears start going a little wonky, and that popping feeling continued for a day and a half. And then I woke up the next morning and had lost 100% of the hearing in my left ear and was told that I would never hear again. So, yeah, there have been some somatic effects of our experiences, haha.

AP: And didn’t you learn, John Wayne, that you had actually had a stroke in that moment? In the sentencing hearing, you had a stroke and that’s what caused the deafness in your ear now.

BP: Right. And just all the typicals, for me, I experienced as a child and as an adult, you know, paralyzing fear and helplessness, a lot of phobias like I’m still worried that bad guys are going to break into my house. Just weird stuff, depression through my entire childhood, guilt, as we’ve talked about, as a child feeling that I should be able to do more. I should be able to understand this. I had no idea what was happening. It felt very confusing, but I felt like I needed to understand it to protect my sisters, even though this sexual knowledge was really out of my reach developmentally. And feeling like a failure. And then a lot of it for me, for my side, which Alex, I would imagine you may not feel this way, you can tell us. A lot of this felt like confusion, cognitive dissonance from being gaslighted, but also, and this is maybe temperamental or birth order related, but I was so fixated on getting my mom to listen and getting her to do something because I knew she was the one who had the power. And the way that was received by my mother and Tupou, who were very clearly on the same team, that was the mother and the father figure. The way that was received was, “Why are you such a troublemaker? Why are you causing trouble? Why are you upsetting Tupou? Why do you keep doing this? Why can’t you just be more agreeable?” That was stated explicitly in a million different ways. So that’s a little identity I’ve hung onto through my whole life. I’m the troublemaker and the bad girl no matter what I do, I’m just always causing trouble. So that really became a part of my identity, unfortunately.

AP: I do think it’s interesting to note that a lot of the pain and suffering is in our relationship to our mother. I think confusion and complexity around becoming mothers ourselves, and we had two parents, we still do, and I have wondered why at times the responsibility we’ve placed more on our mother and what does that say about our own internalized views of the role of a mother compared to a father. I’m still not sure I have clarity on that.

BP: Which speaks directly to patriarchy and who should really bear the responsibility for the safety and wellbeing of children. But yeah, at least for me I was super clear from day one meeting this man that this is a bad guy. I’ve been really clear through this whole journey that this is somebody who should be in jail. The reason we actually brought the legal case at the time we did is because of a particular proposition that was going to enable him to get out of jail sooner. It occurred to us that he could still hurt other people, other girls, and we wanted to prevent that. Any other thoughts there, Alex?

AP: We did learn through the legal process that there is a difference between just your run-of-the-mill opportunistic sex offender and pedophiles. And with a sex offender, typically they prefer sex with adults, but they’ll take advantage of a child. With a true pedophile, they tend to never age out of the system. A sex offender will get old, their testosterone might drop, they’ll get erectile dysfunction, they won’t have the drive to abuse. Whereas a pedophile will never, ever stop abusing. And children are always susceptible as victims, even if someone’s sitting in a wheelchair and can’t get up and chase a victim. So they are prosecuted, at least in California, that was a distinction that it’s prosecuted a little bit differently. And parole looks a little bit different for those groups. In our case, Tupou is a real pedophile and prefers sex with children.

BP: As adults, as far as our role in rectifying the situation was concerned, our responsibilities toward Tupou have felt very clear, at least for me. This is somebody who needs to be in jail for a long time. But as Alex mentioned, a lot of my healing personally has been trying to get more understanding around what happened with my mom, and what does that mean? What happened with my dad? Why was he always at work? Why was that okay? Just that type of healing has needed to happen for sure, and going through all the stages of it.

AP: I’ll also say, Bronwen and I felt compelled to come forward and there was a criminal investigation, but for many victims and survivors, that may not be at all the right choice for them. And it’s not that individual’s responsibility, right? It’s the perpetrator’s responsibility. So I hope that no victim feels that they bear any responsibility, whether or not they come forward and press charges, because it’s an incredibly isolating experience and very few cases that are brought actually end up having a successful prosecution.

AA: Well, that was the next question I was going to ask. Because I did derail you earlier, Alex, when you were going to talk about this next phase of the story and then I got into well, wait, what was going on inside of you? So thank you for indulging that tangent because I wanted to understand what it had felt like inside for you. But take us through that decision that you made. It sounds like he had gone to jail because of this other victim, but then he was going to be up for parole despite the fact that he was a textbook diagnosed pedophile. That they would allow him to get out of jail on parole. Is that right, Alex? And that’s why you made the decision to bring charges against him? How long had it been, and is there a statute of limitations? What was that next piece of the story like?

AP: Thanks, Amy. Yeah, so as a young adult, early twenties, right around the time that I met you, Amy, and was roommates with your sister, I had come back to California after living in Utah. And something about inhabiting the same physical area resurfaced a lot of memories and I found them very troubling. And I actually did call the Palo Alto Police Department at that time and explained that some things had happened to me as a child and I don’t know if they were wrong or not. Can I do anything about that? That’s when I learned that Tupou had been incarcerated. And that did bring some peace of mind, but also great horror, knowing that because I had lied to the police, there were victims after me that had been traumatized by this man. And that police officer also did tell me that because of statute of limitations there wasn’t going to be any legal pathway for me. So I just kind of tucked that away, but it didn’t sit quite right. And as the years went on and I decided I was ready to become a mother myself, I really had to confront this more directly. Like I said, our parents are incredible in so many ways, and it was hard to make sense of how wonderful parents could allow this and facilitate this to happen. So I didn’t have a good trust in myself that I could prevent abuse if it happened to me and I was abused with the parents that I had.

So I ended up reaching back out to law enforcement again, and I spoke to a different detective this time, shared a little more detail, and she told me that this actually sounds pretty severe. And there’s a certain clause with the statute of limitations in California, and this may have changed now too, but if there’s a certain duration and a certain severity, the statute of limitations doesn’t even apply. And this detective was pretty convinced that the district attorney could gather enough evidence to bring charges against Tupou. We also learned that California was considering a law, I think it was called proposition 57, that would prove to be really, really lenient for any incarcerated individual who had good behavior. And I could look and see that Tupou did have good behavior and could potentially get released. So Bronwen and I felt compelled to move forward. And there was a criminal case brought, it was the state of California versus this individual. The way the law works, Amy, as far as I understand it, is that there are civil cases wherein one individual sues another individual for damages, and then there are criminal cases wherein the state or the federal government says that you broke our law and now you need to pay for breaking the law. So this was a criminal case. We were witnesses in a case that the state of California brought.

AA: I see. What year was that?

BP: That was 2016. And there were a lot of legal technicalities actually, in that case. One of them was that you can’t re-open a case that’s already been closed. It’s double jeopardy. So this case had already been opened when we were children, an investigation happened, Tupou went to jail based on something that was told about him by our sister. And interestingly, another nuance to the legal proceedings is that even though the statute of limitations, and I actually can’t recall, there are some forcible sexual crimes such as rape where there’s no statute of limitations in California. And for others, like a sexual criminal felony, you can bring them before the victim’s 40th birthday. I actually can’t recall exactly where we fall on that spectrum, but it was clear that we could bring this case, but that because some aspects of this case had been opened, that there was a lot of nuance about whatever had been brought previously when we were small children, we couldn’t revisit those things.

Fortunately, there was an abundance of other things that we were able to revisit. So it actually ended up playing a little bit in our favor in a very weird way. Very little evidence had been surfaced during that first investigation because who knows what would have happened if more evidence had been surfaced, how that would have played out in court. But it was nice to be able to bring all of this evidence as adults, using everything that we remembered and to be able to really bring the case ourselves in our own voices. That ended up, for me, being a very empowering and healing experience. And I acknowledge that that’s not something that many victims are even able to do. California has extremely liberal laws around statutes of limitations, and there are many states where the statute of limitations are much shorter and don’t really offer anything near a realistic timeline for a child who has been abused and is part of a system that enabled, or at least permitted that abuse and then has to grow out of that system and has to do healing and processing and get to the point where they’re ready to speak up. It ends up being quite illogical, these really artificial statutes of limitations that aren’t accommodating for the typical timeline when these would be brought.

AA: That makes sense. And meanwhile, as we’ve talked about, the perpetrator is continuing to abuse more people and it could be stopped at any point along the timeline, right? If someone were able to bring charges. So, continuing the timeline of the story, there was a period in between 2016 when the case was opened and then the episode that you shared, Bronwen, where you were reading the victim impact statement and literally had a stroke. That’s insane. That was a five-year period, it sounds like. What was that like, and then I’d love it if you could talk about the results of the case and how things have been for you afterward.

BP: Yeah, I feel like you should own this part, Alex. This really is your part. Like, you drove the entire, I was literally just like, “Go Alex, go Alex!” You’re the one. You did it, babe.

AP: Maybe we just talk for a minute about the sentencing hearing itself. That was a powerful moment. I have pictures I can send you too, Amy, if you want to put them in. It was three of us, it was the little friend from second grade, it was the woman he had abused after, a couple of friends, all there.

AA: The little girl? The seven year-old, she got to be vindicated in the end?

BP: And the woman who had spotted Tupou from a mile away and knew exactly who he was and had been maligned.

AP: And the woman from Long Beach from twenty years prior.

AA: Wow.

AP: They were all there. You can actually talk about that part, Bronwen, you’re going to do that one more articulately.

BP: No, it was very cool. Summing up everything that had happened during those five years, of course it started with a decision of like, do we speak up? And as Alex said, that was a unanimous decision. That being said, we were scared out of our wits. We had so many questions. I think one of the biggest challenges for me, and Alex, you can speak on whether this was a challenge for you. But in my heart of hearts, I still believed that maybe nothing wrong had happened. And I actually believed that until the day of the sentencing hearing.

AP: I completely agree. I had no idea how grave the crimes had been, how many laws were broken, and how serious the sentence would end up being.

BP: What drove us to do this is that we wanted to facilitate the protection of Tupou’s past victims and potential future victims. We were fortunate that we knew the names of some of them. I firmly believe there are many other victims of Tupou out there, but we really felt like we had strength in numbers. So my perspective on those five years was that well, nothing really bad happened to me, but I certainly want to advocate for this group of amazing women who have been so damaged by Tupou. So I think that made the choice and the process easier. That being said, I can completely empathize with and understand any victim of sexual abuse, as Alex mentioned, who doesn’t feel like reporting or going to court is part of their process. It’s an extremely intimidating and honestly terrifying experience. And speaking of patriarchal structures of power, I mean, that’s the definition of the courts. It is not designed to be victim-centric at all. You’re literally put on a stand, shaking, facing the perpetrator face-to-face, and being cross examined and accused of all manner of things, and it’s scary. That being said, I couldn’t have been happier that we went through it. It felt like such an important part of our lives, our healing experience. Especially, as I mentioned, the victim impact statement. There were some real repercussions for all of us from that cost that we’re living with. Even today, I absolutely believe that it was worth it. And, you know, somatic symptoms. I lost my hearing, but I will just mention, and I hope this isn’t too gross, Alex threw up and our other sister had some violent physical reactions as well. It was not fun or easy, I’ll just put it that way. Any other questions about court? And if not, we can just talk about what happened afterward and how we’re doing today.

AA: Well, I didn’t ask before if you got your hearing back.

BP: I was told by doctors that I never would. And it was based on lots of studies, but miraculously I have retrieved 85% of my hearing up from zero. It took about a year and a half to get there, and every time I’ve gone to the audiologist, all of the doctors come out and they cheer for me. And they’re like, “This should not happen. We’ve never seen this happen before.” So I feel very, very fortunate. I do have a hearing aid, but I’m in an amazing situation, and I feel really good about where I landed.

AA: Oh, thank goodness.

AP: Bronwen has said it’s her battle scar, a battle wound that she is proud of.

BP: I’m proud of it. It’s a good conversation starter. “I lost my hearing.” “Oh, why’d you lose your hearing?” “Well, let me tell you a story.” But actually, it has facilitated so many amazing conversations and I really am proud to have a scar. If you asked me today, do you want 100% hearing or 85%, I’d be like, for sure 85%. I believe in Jesus. He walked around with puncture holes in his hands. Apparently, he’s still walking around like that today, and he could just heal those himself. But this is perfect because what I felt like happened during that court experience for me is that it felt like giving birth where you’re externalizing something that’s been internal. And it was so much internal pain, so much internal cognitive dissonance and confusion, and it was only through that experience that I was able to really externalize that. And that showed up in physical ways, as you can imagine, but I felt like I was liberated and like I was free. I feel a lot of resolution. I’m not even the same person as I was before that court experience. I’m just so grateful to Alex, she’s always been an instigator and I’m grateful that she kept pushing for that and was bringing us all along with her. Because the healing I’ve received through that has been something really irreplaceable. And at this point I wouldn’t really want to change my child experience at all. I’m much better than I was before any of this happened, and I wouldn’t give away the strength that I feel now.

AP: Yeah, and I’ll say that going into the sentencing hearing, we had no idea for sure what the outcome would be. I was worried that I had dragged everyone through the mud for five years with no upside and no guarantee of outcome. But it ended up being so incredibly validating, more validating than we even knew it would be wherein we sisters could say that our parents may never believe that this was wrong, but the state of California disagrees. And that helped us to understand that we disagree. And it solidified the importance of protecting innocent victims. It really opened up in me this ability and compulsion to dedicate substantial life energy to eliminating child sexual abuse. I knew I needed to start doing whatever I could here in Utah, which is where we’re living, and that’s kind of what led me to meeting you, Amy. Should we talk about that?

AA: Yeah. Our reconnection after like 15 years or something. Yeah, tell that story from your point of view, Alex.

AP: Okay. Pretty special story. Right after the sentencing hearing, I knew I wanted to dedicate substantial life energy to prevention, and I knew I needed to better understand the efforts in Utah and get up the learning curve here. So I just started making a list of any stakeholder I could think of, and that included nonprofit groups, private organizations, and public organizations. And there are some incredible ones in Utah focusing on everything from prevention to detection, prosecution, all the way to healing resources and aftercare. So I tried to meet with any stakeholder I could and asked, what’s the work that you’re doing and where do you need support, where are the holes? And the thing that I hadn’t expected, that I kept hearing again and again, was that these groups said that their biggest pain point is the legislature or lack of legislative support and legislative funding. Whether that’s “We need loopholes to be closed” or “We need harsher punishments” or “We need funding.” And that was really curious to me and not what I expected to hear. Maybe I was listening a little bit biased because I studied policy in grad school and I worked on campaigns.

But I started looking at the makeup of our legislature here in Utah, and I learned that even though half of the state of Utah is female, less than a quarter of our state legislature is female, and zero percent of our federal delegation. Our four congressmen and our two senators, every single one of them is male, and I was curious what that might mean for abuse prevention efforts, if anything. So I dove into research on legislative spending and of course, none of this would surprise you, Amy, given how well versed you are in this, but I learned that women and men have significantly different spending priorities in any legislature. And that’s not unique to Utah, that’s not even unique to the United States, but women in government tend to place less emphasis on defense spending and energy spending, and much more emphasis on education, healthcare, social programs, and environmental protection. To be clear, both male and female legislators tend to favor expansion and support a lot of this, but females will actually fund it and will prioritize dollars there. Females also tend to redirect more funding back to their districts, the people who elect them, and they also tend to respond to constituent requests more. And it really underscored the importance to me of the need for equal representation everywhere, right? Because by electing women, you are actually changing how the government functions, and that’s actually changing how citizens live day to day.

So I was kind of grappling with this. I was really interested in asked about this new information to me and what it might mean in child abuse prevention efforts. And it prompted me to reach out to you, Amy. I was a podcast listener and figured that if anyone can help me interpret the power dynamics at play here in Utah that are unwittingly impacting abuse prevention, I think Amy could help. So we went to lunch, you generously agreed to meet with me, and then you connected me with your friend, Emily Bell McCormick. And Emily is the founder of a nonprofit called The Policy Project. It’s based here in Utah, it’s a 501c3 that acts as an accelerator for sound public policy, and they do that through community education and engagement, relationships with the legislature, and the creation of public-private partnerships.

So Amy and Emily and I got lunch and I ended up joining The Policy Project. And we got to work. It consists of six women, and we have hundreds of incredible volunteers and supporters. We collectively launched the Safe Child Project, Senate bill 205, which just passed in the Utah State Legislature a few weeks ago. What that bill does is it fully funds child sexual abuse prevention education for every elementary school in the entire state. There are many states that allow abuse prevention education, but not many that fund it and Utah is actually the first state in the nation to secure ongoing funding prevention education. The goal is that every K-6 student every year or every other year can learn what sexual abuse is, how to recognize it if it’s happening to them or someone they know and love, and how to report it.

even though half of the state of Utah is female, less than a quarter of our state legislature is female, and zero percent of our federal delegation…

AA: It strikes me that that would have been life-changing for you. Because you were both so young and you were being actively groomed and gaslit and told that there was nothing wrong. And I think that if there had been an educator in your classroom who had been speaking candidly, if this or this happens, that is wrong, here’s what you can do. Someone might be telling you that you can’t say and that it’s a secret, but actually… You know what I mean? Am I right in thinking that that could have changed the whole trajectory for you?

AP: Absolutely, Amy. And I’ve actually spoken to survivors who said that they had a curriculum like this, and some didn’t disclose right away but some did. And then some said that if they come again to my school, this educator, I am going to work up the confidence to share next year when they come. And the only thing we were hearing at home was that this is completely normal. This is happening to everyone. It’s how the world works, you should come to expect this. I was learning at school things to stop, drop, and roll if I catch on fire, or to sign a document saying no to drugs, but nobody at school or at church or anywhere was talking about what child sex abuse is and what to do if it’s happening.

AA: Yeah, that’s incredibly powerful. Also, it was an honor for me to introduce you to Emily. I knew that it wasn’t my area of expertise, but I’m grateful and lucky to know a lot of great people. But there was this really special moment, Alex, because you had told me the story. As we said, we had known each other in Palo Alto years ago, so we already knew each other, but we reconnected in Utah after all that time. You told me what happened in your life and that you were interested in working on child sex abuse. And when I said that you need to meet Emily because Emily does policy, we did not know that that was going to be the next project for The Policy Project. It was only sitting at lunch, and it gives me chills and makes me cry actually to think of that moment when we went to lunch with Emily and I was like, “You do policy, you do policy. Let me just sit here and listen to you talk.” And Emily said, “I haven’t quite announced it yet, but the next project we’re doing is on child sex abuse prevention,” not even knowing your backstory. I felt honored to be there, it was one of those little miracle moments where it’s like, wow, something really special is happening here.

AP: I cannot agree more. Thank you, Amy.

AA: Yeah. It was an honor to be a part of it. Again, I am so, so grateful and honored that you were willing to share your story. I’m so grateful for the work you’re doing in the world, making it a safer place for children. I’m wondering as we wrap up the episode, if you could each share some final thoughts with listeners.