“We tend to believe that our brains are telling us the truth, which is the biggest scam in the world”

Amy is joined by author Kara Loewentheil to discuss her book, Take Back Your Brain: How a Sexist Society Gets in Your Head—and How to Get It Out, plus strategies to change our thought patterns, break out of sexist social conditioning, and live our values from the inside out.

Our Guest

Kara Loewentheil

After graduating Harvard Law School, litigating reproductive rights, and running a think tank at Columbia University, Kara Loewentheil did what every Ivy League feminist lawyer should do: quit a prestigious academic career to become a life coach! Less than a decade after leaving the law, Kara has taught hundreds of thousands of women how to close the “Brain Gap” that keeps them feeling anxious and dis-empowered. Her work enables women to identify the ways that sexist social messages impact their brains and how to rewire their thought patterns to create true, authentic confidence from within. Her internationally top-ranked podcast, UnF*ck Your Brain, has been recommended by sources from The New York Times to the We Can Do Hard Things Podcast with Glennon Doyle.

The Discussion

Amy Allebest: Recently, I was giving a big talk at a conference. I am totally comfortable with public speaking. In fact, it’s one of my strengths. I had done the research and I knew that the content that I was presenting was incredibly valuable. And yet, in the hours before the presentation, I was consumed with self doubt. My body was flooded with anxiety, I swore I would never accept a speaking engagement again. And one thought I had was, “I wonder if I feel this way because of the way I was raised. I bet if I had gone to an Ivy League school when I was 18, if I had been raised to believe that it was okay for women to work outside the home, if I had seen women leaders, if I had pictured myself as anything other than a wife and mother, then I wouldn’t be feeling so insecure.”

And maybe part of that is true. But when I started reading Kara Loewentheil’s book, Take Back Your Brain: How a Sexist Society Gets in Your Head and How to Get It Out, I was shocked to read that this woman, this author, who literally attended Yale and Harvard as a young adult and has had high-power jobs and leadership positions all through her adult life, sometimes struggled with the same kind of self-doubt that I did. Her book is an instruction manual on how to rewire that programming, and I am thrilled to welcome author Kara Loewentheil to talk about this book today. Welcome, Kara!

Kara Loewentheil: Thanks for having me! Just the title of this podcast, as soon as I saw it, I was like, “Wow, that’s my natural home.”

AA: Awesome. Well, likewise. When I saw the title of your book I was like, “Must order, must read that now.” And honestly, I will say to listeners, I get this question and comment a lot from listeners and viewers on the YouTube channel too, doing the work of breaking down patriarchy and understanding the history and how we got here is super important, but the question I always get is, “Okay, now what? Now I can see it, I see the things that are wrong in society. I can even see the patriarchy that I’ve absorbed into my own brain, but how do I rewire it?” And your book was so incredibly helpful to me personally in doing that work, so thank you. I highly, highly recommend this book to listeners. Go out and buy it right now and we’ll tell you how to buy it in a second. Okay. First I’ll read your professional bio, Kara, and then I’ll ask you to– Yeah, the part where you just squirm in your chair.

KL: Oh no, you know what? Women should be proud of their accomplishments. On my podcast, I make women brag about themselves and it’s so uncomfortable for people. People come on and I say, “I’m not doing an introduction, I’m going to introduce your name and I want you to talk about your accomplishments,” and people are very uncomfortable.

AA: They are. Do you want to do that then? Should I put you in a hot seat?

KL: I can do that. I’ll do it.

AA: Okay, tell us about yourself.

KL: I come from what I call the very common Ivy League lawyer to life coach pipeline. I started my career as a lawyer. I’ve been a professional feminist my whole life, one way or the other. I went to Yale, as you said, and I was the coordinator of the Yale Women’s Center and escorted at the service clinics and et cetera, et cetera. And then I graduated and I worked for Planned Parenthood as a media writer. And both in the reproductive rights movement and in my Jewish family it was sort of like lawyer or doctor were the two big career paths, and I was definitely not going to be a doctor, so I became a lawyer. I spent years strategizing to get to the exact position I wanted, which was to be a reproductive rights litigator. There are maybe twenty of those jobs in the country. It’s a small group if you want to be practicing at a high level doing constitutional litigation, which is what I wanted to do.

So I went to Harvard Law School and I clerked for a federal appeals court judge and I did all of these very mainstream things you have to do. And I got that job, there was one litigation fellowship in reproductive rights the year I finished my clerkship because it was 2008, so there was economic collapse and funding had dried up for a lot of places. I got that job, so I had my dream job at a national nonprofit that litigates all the big reproductive rights cases. And I had been working to get there for 8 to 10 years and I had that experience that I think a lot of women do, which is like, “Okay, I got the brass ring and I still don’t feel confident or good about myself,” right? All along the way, it was like, “If I get into a good law school, okay, if I get a clerkship, if I get a federal clerkship, if I get an appellate clerkship, if I get a litigate, if I get the fellowship litigating, if I, if I, if I… then I’m finally going to feel good.”

And at a certain point, I had to admit that possibly the answer was not to get the next career accomplishment. Well, I wasn’t quite ready to admit it, so first I went into academia because I I didn’t understand academia and I thought they had their summers off – don’t know why, if you ask any professor you know. So I did a fellowship at Yale and then I ran a think tank at Columbia, and at that point it really was clear that no accomplishment was going to change the way that I thought and felt. I had gotten into yoga and then meditation, I’d gone to therapy, I’d been on that fixing-yourself journey that so many women go on. And around the time that I started at Columbia, or I was finishing my second-to-last fellowship, I discovered the kind of coaching that I have built my work on the foundation of, of actually changing the way you think. And it was really powerful. When I found it, it was not feminist in nature. It was like the underlying cognitive tools, but even without the lens that I then later had to create it was really powerful and helpful. And I decided that I was going to take this leap. And so instead of going on the market to get a law professor job, I quit and became a life coach on the internet instead. And here I am eight years later with a famous podcast and a book coming out. So what I’m saying is, everybody quit your job and get a job on the internet!

AA: Perfect. That’s what I’m telling my kids to grow up and do.

KL: My parents have come around. They’ve adapted. It was a shock at first, for sure.

AA: I bet. Okay, tell us about your podcast and then a little bit about the book and where people can find it.

KL: Yeah. My podcast is called Unf*ck Your Brain: Feminist Self-Help for Everyone, and that podcast really was the beginning of this particularly feminist bent to my work. And it really took off, I think, because there’s such an appetite for it and such a desire for concrete tools. Because people ask me for my advice, having a big podcast, but I didn’t do any advertising, I didn’t have any sponsorship. I was just teaching things that I had found helpful and that I felt were news to me when I learned them, so it seemed like other people needed to know them too. So that’s the podcast, and I’ve had it since 2017. Really wild to think about. That’s almost seven years.

And now I have my first book, which is Take Back Your Brain: How a Sexist Society Gets in Your Head and How to Get It Out. And the book is really designed to be like a one-stop shop. So it has sort of a little bit of everything, but it adds up to the whole of what you need. It has some of that historical and social context of explaining why we think and feel the way we do and how the beliefs that we’ve absorbed are integrated into society in ways we don’t even see, and how those impact the way that we actually think about ourselves. And it also has very concrete tools for changing how you think, because I think a lot of women, or people, socialized women, have experienced what you’re describing. “Okay, now I’m aware, but I don’t know what to do,” which honestly is the same thing that I and a lot of my clients experienced outside the feminist context and talk therapy.

AA: Totally.

KL: I went through that, where I was sort of like, and this is in the past, I’m engaged to a lovely man now, but in the past, it was like, “So, I understand why I’m attracted to unavailable men, but what’s the plan? Do I just keep doing it and watch myself do it? Do I chain myself to the radiator? How are we solving this?” And I think that cognitive change strategies are really the answer to both those questions of: how do I take this awareness and actually make it something that I can, not to sound like a tech bro, but to operationalize in my life, right? How do I take the awareness that the reason I feel so insecure is socialization and actually feel more confident, not just go through life still feeling insecure but at least I guess knowing it’s not my fault. Which is better than nothing, but it’s not as good as feeling confident.

AA: Yep. Awesome. I loved how you point out multiple times in the book, as a little reminder, that you’re framing this book as, I mean, we think of it as a self-help book. And you point out that when men talk about these issues of how to live the good life we call it philosophy, and typically when women write about the exact same topics we call it self-help and it’s thought of a little bit differently, right?

KL: Yes. I think even in bookstores, even if we don’t even get to philosophy, the same topics that for women are in self-help for men are in leadership development or executive development. Even within the self-help genre, it’s like executive and leadership is kind of the male version, which is somehow more highfalutin than just ladies trying to help themselves. But a lot of the questions that my work asks that I’m teaching my students to ask are those big questions. These are the questions that Aristotle and Plato and Socrates were asking. I went to Yale and I did Directed Studies, which is like a read-all-the-books-by-the-old-dead-white-men-philosophers program, essentially. But it has its benefits, and one of those is seeing the ways in which these are the same questions we’re asking, like, how do I know what’s real? When you start to think about, okay, what’s actually happening and what’s my thought about it and what’s the gap in between those things? That’s a question of what is real. How do I come to know what I believe is reality? How do I experience whatever’s outside of me? What meaning does my mind make of it? What kind of person do I want to be? What kind of person should I try to be? What are my responsibilities to myself or to my fellow people? What is the good life? These are all questions that women are encouraged to never think about and to be occupied with the day-to-day of life and be overloaded with the day-to-day of life because we are socialized to feel that we always have to be in service to everyone else in order to feel worthy or valuable.

So, I think those questions are essential for any human, and that women have been socialized not to ask them, and women have been socialized not to trust their own answers. We’re socialized to believe that we are not the authority in our own lives and we can’t be trusted to make big decisions. Sometimes I imagine this art piece that shows voices yelling headlines from the internet and magazines at women from the moment they get up with each stage of your day, the number of articles or reels or whatever out there, they’re telling you that you don’t know how to do it and you’re doing it wrong. Like, what kind of water should you drink in the morning, what kind of skincare should you use, what outfits are you allowed to wear for your body type, what colors look good on you or not. And should you be drinking coffee? No, you should be drinking tea. No, it should be matcha. No, it should be mushrooms. It’s just endless, and women live with this barrage of explicit and implicit messages that we cannot possibly make our own decisions for ourselves. Every woman I know thinks she’s doing everything wrong all the time, essentially.

How do I take the awareness that the reason I feel so insecure is socialization and actually feel more confident, not just go through life still feeling insecure but at least I guess knowing it’s not my fault…

So we’re systematically stripped of the time and ability to ask those questions and the trust in ourselves that we’re allowed to make those decisions for ourselves. I think of it as practical philosophy. And so, of course, it’s self-help because women and other marginalized people have always had to help themselves. And I’m not in any way against conventional therapy, even mainstream coaching, I think there’s a lot of benefit to both those things which were also primarily created by white men who were not sitting around asking themselves “Huh, I wonder how this changes if you’re socialized as a woman?” That didn’t occur to them. They didn’t give a shit, they weren’t socialized as women! So we’re going to have to make our own way, help each other, help ourselves, learn a different approach, because the mainstream even of the self-help industry is not going to deliver that to us.

AA: So true. Thanks for that framing. Let’s dive into the book. I have so many questions for you and passages that I want to highlight for listeners. I loved that you were so personal and vulnerable. And you opened the book, as I mentioned in the intro, with a scene where you were having a moment where you were feeling flooded with self-doubt, sobbing under your desk. Can you talk about that moment and what that symbolized for you?

KL: Yeah, although it’s funny to call it that moment, because that was not the only moment that I was crying under the desk, it was just the one that starts the book. I mean, I think that I really experienced so many times the “when I get there, I’m gonna feel confident.” Like, “Okay, I don’t feel confident after college, but if I get into a top law school… Okay, I got into the #2 law school at the time, but I’ll feel confident if I get a clerkship…” If, if, if, if, if. And it just didn’t matter, right? Every woman I know and every person socialized that I know has experienced the way in which if your brain is programmed to believe that you are always not doing enough and not good enough, which is what we’re socialized to believe, your brain will always move the milestone. It always moves the marker. Or if you do succeed, that it has some reason that it doesn’t count. It’s like, “Oh, it turns out that it wasn’t as hard as I thought.” Or “Oh, no, I only got that promotion because I work hard, it’s not because I’m smart.” Or “It’s because I’m friendly with so-and-so and they were just being nice.” The number of women I have coached who think somebody married them or promoted them just to be nice to them, which is also hilarious because that’s not really how men are socialized to act, so I don’t think that’s what’s happening. Straight men aren’t socialized to marry women just to be nice to them as a favor.

So, I experienced that insecurity my whole life until I found coaching. And I also don’t ever sell coaching as like, “You’ll never have a negative thought again.” You have a human brain. I’ve done so many podcast interviews for my book, and my brain has its own favorite thing, which is like, “You talk too much and you could be more succinct.” And I’ve done a lot of work to reframe for myself that this is how I talk, so I might as well think it’s a strength. Obviously, it’s worked pretty well. But that conversation still runs on. The big difference is the way that I relate to and engage with those thoughts. When you start rewiring your brain you start changing your thinking. Some thought patterns will eventually just go away, you don’t have to deal with them anymore, which is awesome. That’s not what happens for all of them, but your relationship to them changes. It becomes much more like when your kid is really upset about something that you know doesn’t matter, and you’re just like, “Okay, I know it’s very upsetting.” You can be compassionate, but you’re not sucked into “Oh my God, I am a stupid idiot.” You’re just sort of like, “Okay, I hear you. I know.” That’s just a thought I have and I don’t really believe it anymore. It’s sort of like a ghost thought.

So that’s where I’ve come to, but I really want to normalize that when you start changing your thinking your old thoughts don’t just disappear. I mean, part of the problem is that people think that awareness will change their thinking, like, “Oh, now I know why I feel insecure. Why is it still here?” But awareness doesn’t change your brain’s neurological structure. And even when you start thinking something new, you’re strengthening one neural pathway, but you still have a really strong old one and it’s going to take a while for the new one to become dominant. I think that a lot of people start trying things and then they just quit before they give it enough time to really sink in and work.

AA: Yeah. I think we’re probably all guilty of that in some area of our lives. And that’s why sticking with the book and thinking I’m actually going to do these exercises, I’m going to put myself through the paces just like anything else, to actually make the changes. I want to back up just a little bit and examine that voice, you call it “the voice” in the book, and have you talk a bit about where it comes from. And I want to say here, too, that a lot of the men in my life also struggle with similar things of self-doubt and imposter syndrome and a lot of pressures, but there is something specific that I think women typically experience differently. Can you talk about the voice that women tend to experience?

KL: Also, I want to say in response that that patriarchy is bad for everybody. The next book will be For Men: Take Back Your Brain, haha. There are obviously a lot of ways that men are socialized that are very detrimental and keep them from connecting to their emotions and being vulnerable and being intimate and all sorts of things. So, patriarchy is bad for everyone. This is just where I focus. And I am engaged to a man and he has lots of some of these thought patterns also. The difference that I see for women is that it’s always getting related back to like, “I’m basically not worthy and shouldn’t exist.” I will see that men might have imposter syndrome or might have insecurities about their body, but it often doesn’t seem to go as directly to this sort of, “Therefore, my body is disgusting and I need to hide it. I could never let anyone see me naked, no one would ever be attracted to me.” Women are so socialized in this way of thinking that you’re supposed to be perfect, and so anything that’s “wrong” with you is a strike at your very worth or value or deservingness of anything. And again, yes, some men struggle with that as well. But I do think that the way that women are socialized is to believe that our worth and value essentially come from other people’s opinions of us and perceptions of us, and from the never-ending impossible struggle to live up to impossible standards.

So I think that women seem to be more often, on a day-to-day basis, questioning their own worth and value and right to exist. It sounds dramatic, but when you work with people’s brains all day, like I do, you really see the thoughts they have that they’re not even aware of or wouldn’t necessarily admit to. Most women won’t say at the beginning of the conversation, “Oh yeah, I don’t know if I’m good enough to exist.” We don’t have that thought consciously playing in our head all the time. But when you start coaching and you start getting into those tender parts or the places that people feel really insecure or really rejected, that’s what you get down to, is some variation of “I’m not worthy of love, I’m not good enough to be accepted or to have relationships or for anyone to care about me.” The voice is what I call that internal monologue. Some people have a very verbal internal monologue that they’re very aware of, like mine is like having another person and it’s a whole conversation. For some people it may be more pieces here and there, some people are not as used to tuning in to their own thinking and they’re not as aware of their thoughts. Some people may be more visual and they see more images. But the voice is sort of the way that socialization comes out in our brains.

We pick up all these messages implicitly and explicitly from society for our whole lives. Like, who do you see as the heroine in the movies and what does she look like? Who’s the CEO of everybody’s company, and who’s at home with their kids? Who are people asking about losing weight or not? Who are people asking about getting engaged or not? It’s just constant gender signals and messages that we’re absorbing. It’s sort of like your brain has all these LEGO pieces and it’s building thoughts for you out of these pieces, but they sound like you. So if you heard it in a male announcer voice like “Women with cellulite should be ashamed of themselves,” it wouldn’t be as painful, right? You’d be like, “Oh, that’s the patriarchy. That’s what that is.” But that’s not what you hear. What you hear is “Oh my God, I don’t know if I should wear shorts this summer. I know I’m supposed to be confident, but my legs remind me of my grandmother’s legs, and they shouldn’t look like that. Maybe one of those treatments online does work.” It sounds like your voice, which is the problem. We tend to believe that our brains are telling us the truth, which is the biggest scam in the world because your brain is almost never telling you the truth. But we think it is factually observing and narrating to us. So the voice becomes that really oppressive internalization of all of these messages that we don’t even realize are external messages because they just sound like us. They just sound like our thoughts.

AA: Such a good point. That’s one of the trickiest things for me to figure out and in parenting my kids, also, and we talk a lot about when to believe yourself and when not to.

KL: Ugh, there’s no easy answer!

AA: There’s not.

KL: It would be great if there was, but there really isn’t. Sometimes you are going to believe something dumb your brain said and sometimes you’re going to dismiss something that was true. But one of the things I see in the women that I coach is this desire to have the exact right answer because we don’t trust ourselves and we don’t think we’re allowed to make mistakes. It’s like women are socialized to believe that there’s zero room for error, and that any mistake is fatal and is a sign that they are bad at whatever or that they can’t trust themselves or they’re unworthy. I’m constantly getting questions like, “How do I know when to trust myself and when not to?” And I’m like, “I wish I could give you a three-part test or a little dye test you could do, but you just have to decide.” You’re not always going to get it right, and I’m much less concerned about if you are making the “right” decision and I’m much more concerned with how you talk to yourself when a decision doesn’t work out the way you want.

AA: Yep.

KL: Like, what is your relationship with yourself when you do try something and fail or when someone does reject you? How are you talking to yourself then? That is what is most important.

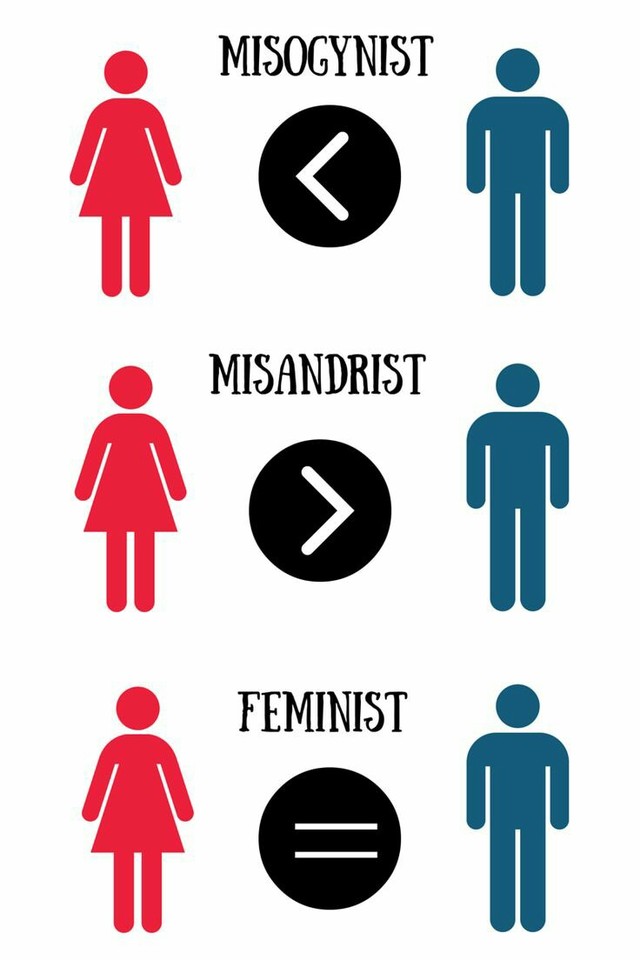

AA: Yeah, that’s great. Okay, we’re going to pivot to a different topic that you bring up in the book, and that’s feminism. We’ve talked a bunch on the podcast about feminism, but it still is such a polarizing word, which is so silly to me. I’m a big fan of looking at a dictionary if there’s a word that everybody’s arguing about, like just look it up in the frickin’ dictionary and let’s agree on a definition and then you can agree with it or not. Tell us what feminism actually means, and I loved your three options regarding your stance on feminism. What are they?

KL: Yeah, this is how I define it. I’m never trying to get into a fight about objective truth. It’s all just thoughts, man. Everybody’s got their own thoughts. But the way that I think about feminism is that it is actually not really about women specifically, it is the belief that people should have the same options and rights and opportunities regardless of their gender. There aren’t only two genders, feminism isn’t just about women and men, there’s a spectrum of gender. So what I see in the book is that people seem to think that there’s this neutral thing they can be where they’re not a feminist and they’re not a sexist. And I’m saying that I don’t think that’s true. If you start at the top, there are two camps. One is that people of all genders should have the same rights and opportunities, you know, equity and equality. The other camp says that some genders should have different and better rights, or has a belief that one gender is better than the other. That’s it, those are the two camps. So, if we’re sticking in the heteronormative paradigm of man and woman, then you could be a misogynist, which means you think that women are inferior, you could be a misandrist, which means you think that men are inferior. And the fact that almost no one knows that word and that it seems hilarious to say you choose that as a policy perspective just shows you how sexist our society is. So you could be a misogynist, you think men should have more rights than women, you could be a misandrist and think that women should have more rights than men, or you could be a feminist and think that people should have the same amount of rights. Those are your three buckets. You don’t get to be a neutral that’s not sexist. That is a feminist.

AA: Here, here. Bravo. I love that. And I love how simple it is. It’s not complicated in my view. I love your explanation of that. Another question on a topic related to this is that lately I’m seeing a lot of women doubling down on gender essentialism. For example, women saying that we need to reclaim emotion and intuition because men are more logical but women are more emotional, so lean into your emotions and that’s the way they want to be feminine.

KL: Oh God, so many soapboxes I have about this. So many thoughts and feelings.

AA: Please, up on the soapbox you go.

KL: I’ll try it out. The short soapbox would be, I mean, you can imagine in the self-help-wellness-y world, oh my God, there’s so much divine feminine and divine masculine, and those are not actually gendered. You cannot just take a word that has been something for a thousand years and declare that it doesn’t mean that thing. I just think it’s ridiculous to claim, if you want to talk about different types of attributes, okay! You could make whatever collection or schema of attributes you want to make and call them whatever you want. But when you call things masculine or feminine, you are bringing up a schema that people have been socialized with about what is masculine and what is feminine. It would be like me saying, “These are blue, but they’re not blue. They just look like blue.” I can’t even think of a good example for it. You can’t divorce the words from that historical context.

As somebody who started my career doing policy and historical and legal analysis, there’s always an interesting way in which radical extremists end up converging. You see that in radical conservatives who believe that there are only two genders and that the sex you’re assigned to at birth is your correct gender, and there are only two. And they need to marry each other, and everybody needs to be straight, and everybody’s defined by their genitalia. That’s one side of the horseshoe, and then you have radical feminists with a big focus on biological gender and the unique social contexts and vulnerabilities of women based on biological gender. So those horseshoes come around, and they end up almost meeting. And we see that in every generation. It would be fun to do MadLibs where you take off the identifiers and you just mix up the terms and then see if you can identify whether it was a very right-wing conservative or a very woo-woo supposedly left-wing person who said it. The horseshoe’s converging.

You don’t get to be a neutral that’s not sexist. That is a feminist.

AA: True. You can see that with anti-vax stuff too, right? The most conservative and the most liberal–

KL: It’s coming back around. They’re both distrusting authority in different ways.

AA: Yes, exactly. Well, that’s super interesting and I thought it was really important. Another really great point that you make, which I loved, was that you talk about, well, in the whole book one of the points is to deprogram and rewire our brains. That’s super hard work. So what do you say to people, usually other feminists, who say, “I shouldn’t have to do this work. Why should I have to change? It’s men who should have to change, or the world should have to change. I shouldn’t have to change.” How do you answer that?

KL: I mean, I have two answers. One is that you don’t have to. You get to decide. The book is not here to tell you you should do anything. So, number one, you always get to decide, I’m not telling you what to do. Sometimes people get concerned that life coaching is cult-y and I’m always like, “I don’t want to be in charge of anything you do.” Cult leaders want to be in charge of what you wear and what you eat, and I can barely handle myself. I am not here to tell you to do anything. So, number one, you don’t have to change. Number two, your emotional experience is being created by the way that you think and react to the world. So you get to decide if you are cool with your emotional experience and the way that you’re acting based on it, or if you’re not. And you get to decide, if you’re not, how are you going to deal with that? Do you want to go to therapy? Do you want to do ayahuasca? Do you want to try coaching? It’s up to you. You get to decide.

But number three, we have so much focus on policy and structural issues and how everybody else needs to change in feminism, and we don’t spend a lot of time talking about the ways that we might also be complicit in and contributing to the perpetuation of these systems. Or we talk about that in a very virtue-signaling way, but we’re not actually doing that work internally. And from my perspective, obviously we internalize these social beliefs, that’s how they keep getting created out there in the world. We’re all living them out because they have been programmed into us so deeply. So even if you’re someone who says, “I don’t give a shit about my emotional experience, I just want to create policy change,” whose brain is creating policy change? If your brain is deeply programmed and captured by patriarchy, which I promise you it is, even if you’re a feminist like me, mine was too, then the ideas you come up with, the way you can communicate, all of that has come from your brain. Everybody who’s ever changed society, it was because they had managed to get themselves an independent perspective that was different from what society told them.

So I think, fine, let’s keep 90 percent of the focus of the movement on policy, but can we have 10 percent focus on what it’s done to our brains and our emotional health and our emotional lives? And I think it would help more people see the value of feminism. Because the political awareness of feminism is such an awakening for people, and as you said in the very beginning, it often leaves them feeling like, “Well, now I just hate everything and everyone, and I don’t know what to do about it! And I still have to live in this world, and also I still like my dad and my brothers. What am I supposed to do?” You know? I’m living a complex human life that doesn’t completely map up onto this structural analysis, and I think that this internal work gives us a way to bridge and integrate those things and live our values more from the inside out.

AA: Yes. I love it. It seems like sound principles, too. Anyone who’s gone to couple therapy knows that you have to make a plan for if the partner doesn’t change. The world may not change as much as we want to see it change in our lifetimes. What are we going to do in the meantime?

KL: Right. And also, we’re part of the world! The world isn’t this other thing that we can be like, “I’ll just be static and the world is going to change.” I talk a lot in the book about the different ways that we reenact oppressive systems because we’ve internalized them. That doesn’t mean that it’s our fault. I’m not really that interested in the assignation of fault, I just don’t think that that’s all that useful. It doesn’t mean it’s our fault or it’s the victim’s fault or anything like that. It just means that of course if you grow up in a sexist, or a fatphobic, or a homophobic, or an ableist, or a racist society, you’ve absorbed those ways of thinking. And if you don’t try to become aware of them and change them, you are unavoidably going to replicate the systems that you’re trying to escape.

AA: For sure. Well, speaking of that, can you tell us about the concept of the brain gap? I thought that was a really useful phrase.

KL: The brain gap is this gap that women experience between how they want to think and feel and how they actually think and feel. It might sound something like, “I knew I should feel confident speaking because I’ve done this before and it’s a big part of what I do, and I know this is valuable, but I still feel really anxious and insecure.” So it’s that split brain experience of like, “I want to think and feel a certain way,” or “I think I should think and feel a certain way, but I don’t.” One of the examples I give in the book that was very salient for me was that before I found coaching, dating was one of the big areas where I needed to work on rewiring my brain. I had this big brain gap between, “Well, I want to believe that women don’t need to be married or in a relationship, and a man doesn’t define you or validate you, and who cares what men think,” and blah blah blah. And yet, I was obsessively refreshing the Tinder queue to see if a match had messaged me back yet. There is a gap there. What is that? That’s the brain gap. That is the difference between two different thought patterns, which is really important to understand. Because when we frame it to ourselves as, “I want to think this but I actually feel this,” we don’t know what to do with that. What are you supposed to do? You just have a conflicting thought and feeling like you’re screwed.

When you think of these as two different thought patterns, which you probably learned at different times in your life, now we can understand the conflict. Because from a very young age, you’re absorbing messaging around the importance of romantic love in a woman’s life. That women should be very focused on their romantic life, that no matter what else a woman accomplishes, if she’s not married and doesn’t have kids, it’s somehow sad or she’s failed at something. That an older woman who isn’t married and doesn’t have kids, something’s gone wrong. You’re absorbing all of that. And then when you’re 20, 15, even if it’s when you’re 12, you discover feminism and you start hearing other messages and you start wanting to believe those. You’ve still got 10 years of really primal socialization around what you have to do to be judged worthy and okay by your society, which for humans is a real primitive brain survival kind of desire. So that’s the brain gap. It’s that gap between those two or more thought patterns. The only way we can change that brain gap is by, rather than trying to tell ourselves to believe this great thought we wish we believed, using the tools I teach in the book to get very clear on what can we actually believe now and then building our way towards that better belief and ending up with one integrated thought pattern. But if you don’t do that you just end up stuck and ping-ponging because your brain has to choose different thoughts that are not compatible and it doesn’t know what to do.

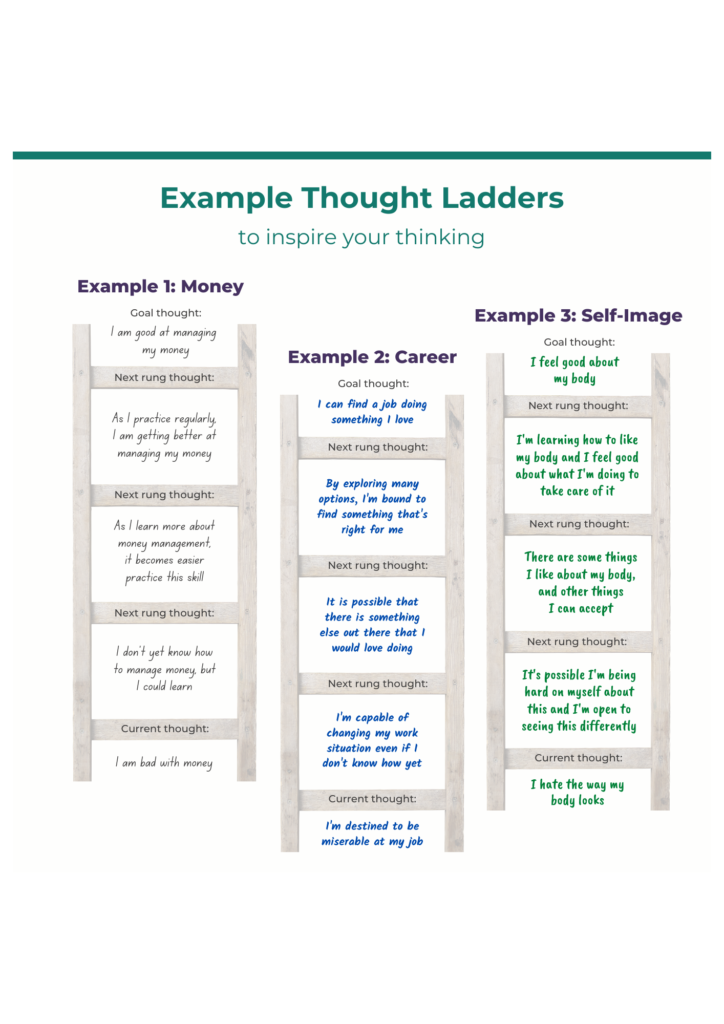

AA: Yep. One of the most useful exercises in the book for me was the ladder exercise to do that very thing. Okay, I recognize I’m at A and I can even see why, I want to be at B but I don’t know how to get there. Can you talk about the ladder?

KL: Yeah. The thought ladder is a tool that helps you go from what you’re believing now to what you want to believe. I think it’s a crime of the self-help community that what most people have heard of is just positive thinking or affirmations, which generally don’t work. There’s at least one study that I cite in the book that shows that trying to practice positive thinking can actually backfire and make you feel worse when you don’t believe those thoughts, because it just emphasizes how far you are from what you want to believe and how impossible that seems to you. So they’re not helpful, but that’s the only tool people are given. To just think positively, or good vibrations, or whatever. The thought ladder teaches you how to create what I call a 10 percent less shitty thought. Because we’re really just going for incremental change, right? You can’t go to the gym and be like, “I want to deadlift 400 pounds. I’ve never done anything. Let me try to pick that up.” You’re going to break your back. It’s not even going to come off the floor. Nothing’s going to happen. You have to start small and start lifting and build your way up.

And the same is true for your brain. Your brain’s not a muscle, but you can say any sentence to yourself. I can say to myself, “The lizard people built the pyramids.” I don’t believe that, there’s no emotional payoff in my body. And the same thing happens if you’re trying to go from, “I hate my stomach” to “I’m a beautiful goddess.” You can say the words to yourself, but there’s no emotional payoff, it doesn’t feel like anything, you haven’t changed your thought. But when you start with a 10 percent less shitty thought, something like “This is a human stomach. There are other stomachs in the world that look like this.” That is a neutral thought. I always say that your neutral thought should not look inspirational on Pinterest. You wouldn’t put it on an Instagram graphic, nobody would share it with a heart. It’s really just, what can you literally actually believe now that feels a tiny bit better in your body, where you get 10 percent relief from how bad you feel when you think your current original thought? That’s how you can move mountains with that approach, but you have to really start with those small actionable steps. In the book I give a bunch of prompts to help you develop those thoughts. And, of course, I teach that in depth in my membership program, the Feminist Self-Help Society. But the book gives you a really good start at using that tool.

AA: I thought it was so, so helpful. I did it on a couple of different things and even in just a few minutes of drawing it out on a piece of paper it actually really helped me.

KL: That’s the thing, y’all. We’re like, “If I can’t get there in two seconds, I don’t want to go at all.” And I’m like, “Well, I’ll get you there in six seconds. Can we be the tiniest bit patient?” You can actually change how you feel pretty quickly if you’re willing to just take a little step on the way.

AA: Yeah, so true. I want to talk about just a few different topics. You bring up a bunch in the book, but we’ll just drop into a couple. One of them that really resonated for me was the concept of rewiring our brains on having agency and the power to act versus just waiting for life to happen to us. And you talk specifically about how patriarchy has socialized women to have that approach of being passive and letting life happen to us. Can you talk about how we’ve been raised or conditioned to believe that and then what we can do to retrain ourselves?

KL: Yeah. I think that women are socialized and brought up to not trust in their own efficacy or agency. And I want to say that this stuff is relative. I obviously am somebody who believes in my own agency and efficacy to a pretty high degree. I’ve created all of these outcomes. But there are still places that I see that I think probably a man with my success record would think that he could go twice as far, and I’m, like, “Maybe one more third,” right? It’s all relative. So I’m never saying, I mean, I know so many strong women. I’m never saying that women are like spineless jellyfish flopping around on the floor. But if you look inside and think, “Okay, where do I see my own self-doubt still?” It’s all from wherever you’re starting from naturally. I think women are more socialized to put their head down, work hard, and wait to be rewarded. Women get more of that messaging like, “Don’t ask for too much, don’t seem greedy, don’t seem ungrateful, don’t think too well of yourself, don’t get too big for your britches.” We see society often tearing down women who have accomplished things or critiquing women. I mean, people are talking about Oprah’s weight all the time. The woman is incredibly successful and came from nothing, but what does society want to constantly talk about? How much adipose tissue is on her body. There are all these ways it’s constantly forced on us.

And that’s big-scale, and then it happens in smaller communities. Somebody gets divorced or made a mistake or had an affair or whatever, and you can go from The Scarlet Letter all the way up till now. I think that women are socialized to think, “If I make one misstep, that’s it. There’s something wrong with me. Everybody’s going to come for me.” And I had a therapist on my podcast recently, this was after the book so it’s not in the book, but she was talking about this study that showed that parents who are dealing with young kids will intervene to protect girls earlier than with boys. If a girl makes a mistake or makes a mess, they’ll swoop in and fix it for her, whereas boys are allowed to kind of make a mistake and make a mess and figure it out. So, girls get the message that you shouldn’t ever screw it up, you shouldn’t ever make a mistake, you shouldn’t ever make a mess, and girls tend to be more praised for being “perfect”. Like, “That drawing is so perfect,” or “You look so perfect.” So women have this perfectionism bred very deeply. And I think that when you look historically, there have been a lot of negative consequences from stepping out of line. I mean, talk about The Scarlet Letter, right? When I teach a webinar I do called The Feminist Anxiety Fix, I show a picture of a scold’s bridle, something that was put on women who were nagging or scolds. There’s so much historical and probably even epigenetic trauma around standing out, speaking up to authority, wanting more than you’re given, or wanting more than you have. I think all of that contributes to women staying small because being small feels safer.

AA: Mm-hm. For sure. Two more topics on a really great list of lots of different ones, but one that I want to hear you talk about is love and sex, and the other one is women’s relationship with making money.

KL: The book goes into so much more than I can cover here, but one of the things that I think is really important in the book and the chapter around romantic relationships is what I call the four traps of romantic socialization. These are the thought patterns that women are socialized to have around their romantic relationships, which are insecurity, scarcity and settling, fixation and rumination, and magical thinking. The book goes deeper into each of those thought traps, so if you’re somebody who struggles in your dating life or who struggles your romantic relationships, whether that’s having a lot of relationships that didn’t work out the way you wanted, or you’re in a relationship but you feel very emotionally up and down about it, I think that at least one of those four traps is at play.

And one of my favorite things about that very long chapter, and part of it’s about dating and love and part is about sex, my favorite thing that I learned when writing the part about sex was that there’s a term for this phenomenon that I had been coaching on for years, and the term is object of affirmation-based arousal or desire. It’s the idea that women are socialized, and I knew that women were socialized to see themselves as sexual objects, but what I’ve observed in coaching is that women then become socialized to only be able to feel arousal if they feel they’re being actively desired. So I would coach a lot of women who were saying, “Well, my partner’s not making me feel sexy.” And I’m sure some men have said that, but in general men are socialized to see themselves as the sexual actors and as their own sexual desire as being something that arises organically within them just because they are a man, and then that desire finds people or things to attach to. Or maybe that desire is evoked by someone else just existing, but it’s about their desire. Whereas women talk about it as like, “I can’t feel sexy,” by which they mean worthy of desire. They’re not really talking about their own arousal. They’re talking about “I don’t feel desired,” which is what I associate with being in the mindset or the physical state to have sex. So I was thrilled to find a name for that. And I talk in the book about why it’s so important and how to be able to create your own feeling of arousal or sexual desire or sexual agency, because you don’t want to have that be dependent on how someone else is acting.

AA: Yeah, totally. And we’re talking about, in all of these different areas, of being the subject of your own life.

KL: Yes. Sometimes I feel like what I’m teaching just boils down to that I just want women to think that they are actual autonomous human beings who are the central character of their own lives, who exist and can act upon the world in the same way that men are socialized to see themselves as doing.

AA: Yeah, for sure. Okay, how about money? This was a really interesting one. And listeners know about my personal background, too, that I was raised in a very conservative religion that was still teaching girls and women to never work outside the home. So I’ve had to really navigate this as an adult, and since a feminist awakening, really rewiring all kinds of assumptions and feelings that I have about money. Can you talk about that a little bit?

KL: Yeah. I was raised in a family that assumed I’d have a career, but I still had to do a ton of rewiring because I came up sort of identifying with working in the nonprofit world and thinking that people who care about money are bad, or people who want to make money are bad. It’s very hard to run a business with those thoughts, so I had to do a lot of rewiring from a different direction. In the book, I talk about the three money lies that I think society teaches women. One is that money is for men. The number of women I have coached who just believe that they are irresponsible with money, and they can always give you evidence because you can always distort everything that’s happened to you to fit your paradigm. You can always look back and be like, “I shouldn’t have bought that lipstick in 2019. If I’d invested that $12…” and whatever. So, women are really socialized to believe that men are better at making money, that men are better at math and understand the stock market and finances better, even though studies show that actually women make better investors than men. They have better investment outcomes than men because they are, essentially, less arrogant. They actually read things and consider and think about them more and they don’t just blindly trust their own opinions as much.

And I think a lot of this comes from socialization, because if you ask most women what it means to be good with money and they’ll say being thrifty or not overspending. It’s very similar to diet culture. It’s about restriction, sticking to a plan, et cetera. Whereas most men will say it’s about making money and creating wealth, right? And the media we get is totally targeted that way. There are studies that I talk about in the book showing that most of the media targeted at men around money is to take risks, create wealth, build a portfolio, and for women it’s about how to budget, how to be thrifty, how to save money. And historically, women didn’t have their own money, so you were just given some amount as your household purse that you were supposed to manage. So that socialization is still impacting us so deeply today. The first lie is that money is for men.

studies show that actually women make better investors than men. They have better investment outcomes than men because they are, essentially, less arrogant.

The second lie is that wanting money makes you a bad person. I think this is something that we certainly weaponize against women a lot more. Especially being in the self-help and wellness space – I mean, I don’t really think of myself as in the wellness space, but in the self-help and coaching space – I see that the people making the most money, a lot of them are still men. It’s sort of like many professions where most of the people in the profession are women, but the top people are men. And I don’t see a lot of hate targeted at them for building multi-million dollar businesses and wanting to make money and create wealth. That’s just assumed to be natural for a man, but there is so much drama around women entrepreneurs wanting to make money in the self-help or wellness spaces. Or the idea that you could both want to help people and make money is like anathema for women because women are just supposed to help everybody for free all the time until like the Giving Tree, they just die. That is how women are socialized. So, that’s lie number two.

And then lie number three is the idea that you can sort of opt out and that it doesn’t have any impact on the world. And I think that that is tied to the way women are socialized to see themselves as not being full economic participants in society. So it’s sort of like you can just walk away, like I’m not really part of this, I don’t have to participate in it. I’m not a wealth coach, I don’t think everybody needs to want to make money or build wealth, but I want women to have done the deprogramming to choose on purpose. If you just love couponing, great. If that’s really because you just love it, and not because you believe you’re incapable of making money or that it would make you a bad person if you wanted to make money, or that you are somehow demonstrating virtue through the restraint of couponing or whatever other socialization there is. Because when we try to opt out then the current unequal distribution of resources just intensifies, right? So it goes back to that same conversation we were having, that we’ve internalized all of it and we’re acting it out. We can’t just say that the problem is over there. We’re all part of it. If I chose not to have my business, for instance, and not to try to build it, then not only would all the women I’ve helped not have been helped, but also probably they would have spent that money on another face cream that didn’t work and actually stripped their skin, or another weight loss cleanse. All that money would just be going into the pockets of Weight Watchers and L’Oréal. So, there’s no neutral opting out as though you’re not impacting this whole ecosystem that we’re trying to change.

AA: Hmm. I love that. Yeah, I have to go back and read that chapter again. This is something that seriously is, like a lot of this is, so, so relevant to me and I know will be to so many people who read the book. One last thing is something that we haven’t explored as much as I want to, so I was super happy that it was in the book, is the intersection between patriarchy and capitalism and how those two things create unique problems in society. Can you talk about that just for a minute?

KL: Yeah. And I’m surprised we haven’t gotten to it yet in this conversation, but the whole book comes from an intersectional perspective, which means it’s not just capitalism, it’s also race, ethnicity, national origin, age, body size and type, neurodivergence. Any identity you have, you are socialized in a certain way, and that socialization impacts your brain in different ways. The very first exercise in the book is actually going through all your different identities and listing out what messages you received based on that. From the structural side in terms of capitalism, I think that capitalism intersects with patriarchy in so many ways, so we cannot cover them all, but obviously the way that women’s work is valued and what kind of work women do is given economic value and when it’s not. So, all of the traditional labor that women perform in the home, like sex, childbearing, child-rearing, housework, cooking, those are not counted as economic labor when they’re performed in the context of a relationship or in a family. I think it impacts us in terms of women’s ability to rest, because women are socialized to believe that they should always be serving other people or doing something to earn their worth. And capitalism also teaches us that productivity is what determines our worth and our value. So if you’re socialized to believe that you don’t have inherent worth and then capitalism socializes you to believe that being productive is how you get worth, then women get in this constant “I need to be productive” mindset. And also “productive” means such a weird variety of things, because it’s not just work. Somehow cleaning your house or exercising is productive. It has become a catch-all category for anything that we deem to be morally good versus not. So, there are so many intersections.

AA: Yeah. It was really, really great. And I loved how you talk about reclaiming time for our own priorities as a really important act of sovereignty that pushes back against that patriarchal and capitalist framework, of saying “No, I’m going to determine what my priorities are and use my time in a way that might not be on that list of acceptable activities.” I thought it was really useful.

KL: You have to read chapter nine to learn how to do that.

AA: Yes. Well, we won’t give everything away. And you’re right, we are really touching just the tip of the iceberg of the book. But we’re about to the end of our episode, and I want to share one of my takeaways, Kara. I’ll read one passage where you say: “Feminism has not historically provided a solution to the emotional experience that this awareness” – the awareness of patriarchy, basically – “that this awareness created. It hasn’t taught women what to do with all of those emotions and how to handle integrating the awareness of unfairness with the circumstances of their real lives.” I know that we talked about that at the beginning, but I just wanted to emphasize again how useful and valuable I found this book to be. So again, thank you. Thank you for your book and thank you for your work. It has been an absolute delight to have you on the podcast. Thank you so much, Kara.

KL: Thank you for having me.

AA: And just one more reminder, Kara, of where people can find the book. Because I really do recommend that people, as soon as you finish listening to this episode, go buy the book. Where can we find it, Kara?

KL: Yes, you can find the book anywhere books are sold. We’ve got the hardcovers out, the audiobook is out, which I read myself, e-books, anywhere you usually get your books.

AA: Okay, fabulous. And also tell us where to find all of your work. I know you have a fantastic Instagram account, for example, and websites. Where can we find everything else?

KL: Yeah. My name is a little hard to spell, so I recommend you go to takebackyourbrainbook.com. There will also be links there to where you can buy the book, and then my social media is there. Just an easy home for everything.

AA: Perfect. Well, thanks again so much, Kara Loewentheil. Thank you for being here today.

KL: Thanks for having me.

Let’s keep 90% of the focus of the movement on policy,

but can we have 10% focus on what it’s done to our brains?

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!