“the intersection of militarism, nationalism, and patriarchy”

Amy is joined by Dr. Lisa DiGiovanni to discuss the histories of state violence in Spain and Chile, the critical concept of ‘militarized masculinity’, and how everyday people can resist the rise of militarism and hyper-masculinity.

Our Guest

Dr. Lisa DiGiovanni

Dr. Lisa DiGiovanni is a professor of contemporary Spanish and Larin American literature and film at Keene State College. She has a joint appointment as Chair for the Department of Modern Languages and Culture and as a professor int he Holocaust and Genocide Studies Department. her area of expertise is the twentieth-century dictatorial violence in Spain and Chile. As a professor, she teaches introductory to advanced level courses that integrate language, literature, and film and studies state violence as social control.

The Discussion

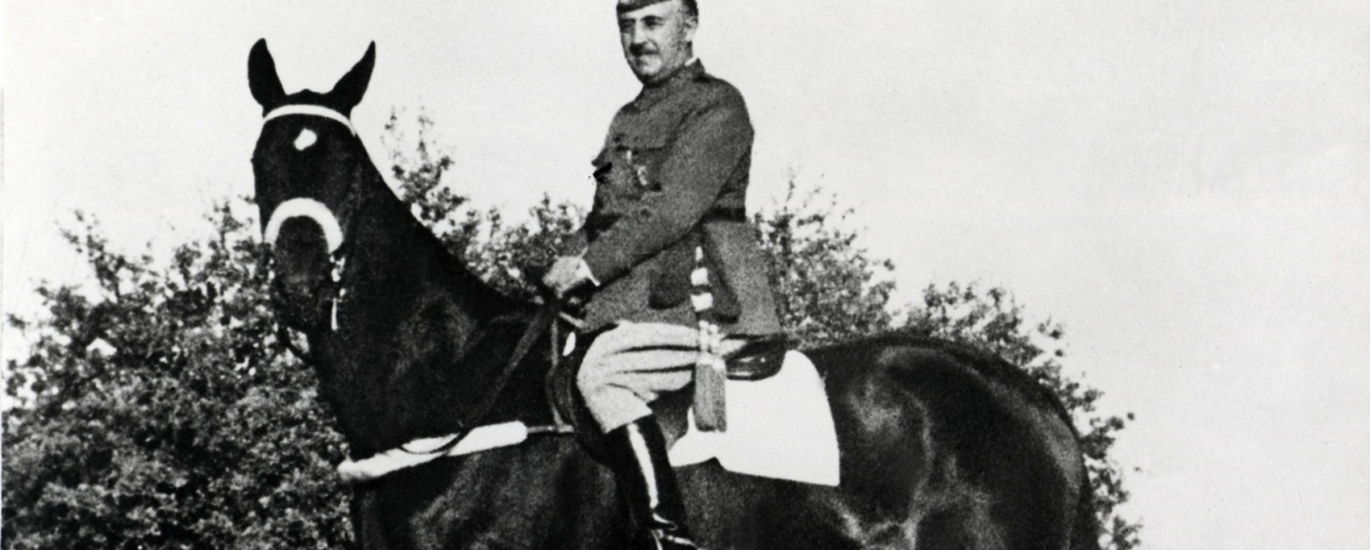

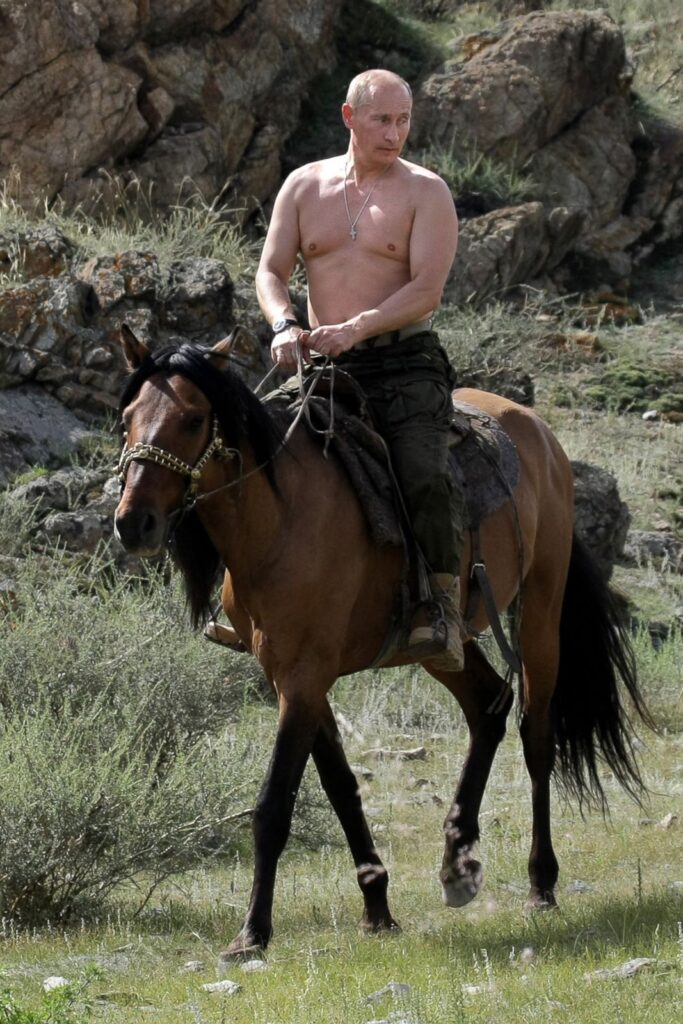

Amy Allebest: We’ve all seen pictures of Russian president Vladimir Putin, shirtless and riding on horseback. President Putin presents a hyper-masculine persona that projects strength and domination and is easy to make fun of. But experts on authoritarianism say that this brand of masculinity can lead to violent conflict on a global scale, as was evidenced in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Lisa DiGiovanni, a professor in the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Department at Keene State College, studies state violence as social control. She refers to Putin’s brand of manhood as “militarized masculinity”, a term that was coined by political scientist Cynthia Enloe. It is rooted in a belief that violent force is the most effective solution to political unrest and that aggression is natural and unavoidable. Putin is merely one recent example of militarized masculinity. Two other examples that I’m familiar with are the regime of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who ruled Spain for 36 years, and the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, who ruled Chile for 16 years. I’m so interested to learn more about the ways that gender influences politics from Dr. Lisa DiGiovanni. Welcome, Lisa!

Lisa DiGiovanni: Thank you for having me.

AA: I’m so excited to have you here. I’ll introduce you to our listeners by reading a brief professional bio first, and then we’ll have you introduce yourself after that. Dr. Lisa DiGiovanni is a professor of contemporary Spanish and Latin American literature and film. Her area of expertise is the twentieth-century dictatorial violence in Spain and Chile. As a professor, she teaches introductory to advanced level courses that integrate language, literature, and film. And Lisa, like I said earlier, I thought it was so interesting to read that you’re in the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Department. Is that right? There’s a whole department dedicated to that at your school?

LD: Yes. And I have a joint appointment. I’m Chair of Modern Languages, so the majority of courses that I teach are in Spanish on contemporary culture and history, but I also teach every year a course or two in Holocaust and Genocide Studies in English.

AA: Amazing. Well, please, if you’ll start us off by telling us a little bit about yourself personally. Where you’re from, your education, and what brought you to this work.

LD: Sure. If we go back in time to 1996, I was around 18, and I wanted to learn everything I could about Latin America and Europe. I wanted to learn Spanish, I wanted to learn French, I wanted to learn Italian. My great-grandparents spoke Italian, Sicilian, and it was lost with my father. My grandparents spoke it, my father spoke broken Italian, and I really wanted to learn both Italian and Spanish. So in 1996, I was only 18 and quite naive, and I traveled down to Guatemala with my backpack for the summer to learn Spanish. And at that time, they were ending a very bloody civil war, and the details about all of the horrors of the genocide of the early 1980s were coming to light at that time. And I returned to the U.S. really wanting to know more.

I did my bachelor’s degree at Northern Arizona University, and I studied Spanish, that was my major. I also spent time in Ecuador before I graduated. And it was very clear to me that becoming fluent in Spanish was absolutely necessary to have a global perspective and to go outside of my bubble. So I moved to Spain in 2000, right after I graduated with my bachelor’s degree. I moved to Madrid to do a master’s degree in Spanish literature and culture. I fell in love with Spain and I wanted to learn more after I finished my master’s degree. So in 2002, I started my PhD and I started to think about dictatorial violence in a transatlantic comparative framework. So I was thinking about the Spanish Civil War, World War II, fascism in Italy, fascism in Spain, and how these relate to military dictatorships and fascism, or neo-fascism in Latin America.

I finished my PhD and still wanted to learn more, and in 2008 I did a graduate teaching certificate in women’s and gender studies. And at the University of Oregon, there’s a fantastic program. I learned so much in that year. It was a way to give language to a lot of the things that I had already been thinking. It was a wonderful, wonderful experience. And with that, I was able to think in new ways about my dissertation and my scholarship, which focused on representations of dictatorial violence in Spain and Chile. So, learning about intersectionality allowed me to see these contexts in new and clearer ways. There’s been so much that’s been written about the Spanish Civil War, about the dictatorial regimes in Latin America, about the Holocaust, but there’s still a lot to be said. There’s still a lot to be discovered in terms of the different connections, there are so many dots that we need to connect, and I think that that’s one of the reasons why you were interested when I gave this talk on militarized masculinity. So that’s a little bit of the background.

AA: Yes, that’s exactly why I was so interested. We met each other briefly because I attended one of your talks at the University of Utah. And it was such an interesting new lens for me to think about, like I said in the intro, how this hyper-masculine persona that some leaders project actually then plays out politically. I have a personal connection to both Spain and Chile, and so your area of interest totally intersects with mine. But even as you were saying, fascism in the time of WWII, I think most people are more familiar with Germany because that’s what we learn about in school. I never studied anything about fascism in Spain in school. It’s only because our family went to Spain and lived there for a little while, and only because I lived in Chile for a time that I ever even heard about Pinochet. And this is so, so important. And the U.S.’s involvement in these dictatorships in Latin America is something that listeners should really dig into more, especially citizens of the United States. They’re stories that definitely need to be told.

LD: Absolutely. I agree with you that the history of Spain is so often left out in discussions of World War I and World War II. And the Spanish Civil War was such an important event. I teach a course called Fascism in Spain, and students are just thirsty for that knowledge because it’s so often left out and it should not be. If we were to look at that history to understand Franco and the Franco regime, you’d need to understand the historical context that came right before, or that produced him, in a way. So, Spain at the very end of the 19th century, turn of the 20th century, was going through an identity crisis in a lot of ways. Spain had lost its huge imperial power in Latin America, there was very large unrest, you had a whole range of political groups from the right to the left. And in the 1920s there was a brief time where there was a dictatorship before Franco’s dictatorship. And during that period you had a very creative and progressive left that would not be suppressed. I mean, think about Salvador Dalí and Federico García Lorca, Luis Buñuel, all of these amazing thinkers, they were coming of age in the 1920s when there was this repression.

In 1931, the Second Spanish Republic was established. The first was established in the late 19th century, but it was very short-lived and returned to monarchy. The Second Spanish Republic was established in 1931. The king, the monarchy, left Spain, and there were enormous hopes in the center and the left for big changes in terms of inequalities regarding class and gender. So the Second Republic was established. This is really important because the Franco dictatorship was very much a backlash. We have to keep this in mind because these backlashes are specific responses, and we see this in different contexts at different times, you see something very similar in Chile. In 1931 you had more involvement of women in politics, but interestingly, in politics on both the left and the right. We can’t just have this monolithic image of women as one. You had both conservative and progressive women in this context, working with progressive and conservative men, struggling for what Spain should look like, where Spain should go.

On the table they had agrarian reform, educational reform, separation of church and state, reform of the military, and all of these things really frightened those groups that had something to lose, or thought they had something to lose, with those different reforms. There was also support of cultural pluralism for the support of the Republic. The Republic was in place before the Spanish Civil War from 1931 to 1936. In 1936, during that period of the Republic, you had swinging back and forth conservative and progressive governments but in a republic. And there were stirrings on the side of the right. And you have to keep in mind that the 1930s was the birth of fascism in Spain. There were Spanish fascists that looked to Italy, some looked to Nazi Germany, but most actually looked to Mussolini’s fascist model. So you had this very polarized social, political, historical, economic context that really came to a head in 1936, when Franco, along with other military leaders, staged a coup to overthrow the democratically elected Second Republic.

Now, in the case of Spain, the military was absolutely divided. You had loyalists that wanted to defend the Republic, and so they didn’t side with the golpistas, those insurrectionists. A three-year war ensued, and although it’s called a civil war, it actually in a lot of ways was an international war. There was a pact of non-intervention by other forces that were growing in power, the Axis forces and the Allied forces. But the Axis forces ended up going against their word and supporting the fascist uprising, so those three years of the civil war very much depended on this international context. The Republic did not get the kind of support internationally that the fascist side got from Hitler and Mussolini, and that was actually very significant.

This is just an overview. There are so many things I could say, I’m kind of simplifying. But you get to 1939, and to be sure there were soldiers, there were activists from the United States that, regardless of the U.S.’s position on the Spanish Civil War, volunteered because they saw in the Second Republic an incredibly important and telling unfolding conflict. So the international brigades, I think that that’s a topic that U.S. history definitely should involve. There were, like I said, writers. Hemingway went, Langston Hughes went, a lot of these big names in U.S. history, cultural, political history, were very interested in Spain. The right won in 1939, and the Franco regime was established. And on those ruins of war, we have to keep in mind that this is in the context of World War II still happening. So in 1939, Franco was still an ally of Mussolini and Hitler and it was a very uncertain time still for the Franco regime. And what happens when a regime is afraid of losing power? There’s a lot of repression. The repression was political, it was social, and it was economic.

you had this very polarized social, political, historical, economic context that really came to a head in 1936

Militarized masculinity played an enormous role in the foundation of the Franco regime. Franco was very much a military man. Part of this conservative backlash to the Second Republic had to do with gender norms. The conservatives wanted to uphold these traditional gender norms. The dictatorship lasted throughout the ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s, and up until 1975, when Franco died. And certainly there was change. It wasn’t monolithic, but the worst years were certainly the 1940s. Those are considered los años de hambre. All of Spain was struggling, but the actual war continued for the Republicans. Even what you can consider middle-of-the-road Democrats to radical leftists, there were anarchists as well, communists, socialists, that whole spectrum, the war did not really end for them in 1939. So many went into exile, many were imprisoned, there was torture. And then in the cultural realm, in education, there was indoctrination, and that kind of indoctrination was absolutely militarized.

There are three important concepts: militarism as an ideology, militarization as a process, and militarized masculinity as a gender identity. Militarization happens through building up the armed forces, placing the armed forces at the center of the state, including militaristic language in education, and also, very importantly, conscription. Obligatory military service was absolutely necessary in this process to uphold this repressive, conservative military regime. And I think that that is something that we can see in multiple contexts. We can see that in Chile. In the case of Putin, which you started out by talking about militarized masculinity and how that really defines Putin’s gender identity, he and the former USSR were talking about the opposite side of the political spectrum when we’re talking about politics and fascism. However, one thing that they have in common, Soviet-style communism and fascism, is this view of an authoritarian, patriarchal, militarized leader. Militarism actually connects these. If we were to look at repressive communist regimes, you have that militaristic element there. And so I find that militarism, militarized masculinity, militarization as a process, it needs to be more front and center. It almost seems that it’s the air we breathe and the water we swim in like gender norms. And it’s so obvious, but it’s so obvious that it’s absent from sight, if that makes sense?

AA: Yes, it does make sense, for sure. That was a fabulous overview and historical framework. That’s so, so helpful. And I’m wondering, as you’re talking about the propaganda of militarization and conscription and the glorification of war, I’m thinking of how that would affect everyday Spaniards at the time. For little boys that are growing up and thinking, what does it mean to be a man? And then for little girls, too. What were the actual rules that were put in place and how did it affect everyday Spanish people at the time?

LD: Hmm. So, I’m a collector of old books, and I think that we can find so much about ideology and indoctrination in school textbooks. I have found school textbooks in both Spain and Chile from the years of the Second Republic, when you had this opening, and it’s saying that men and women are equal. I have this book that’s called El niño republicano, The Republican Child. And it asks, what is a republic? And there’s a section about the embarrassment of slavery and colonization, very forward thinking and published in 1932.

AA: Wow.

LD: So then you see in the 1940s, I have this whole collection, some are authentic and a couple I have are reproductions. But you have these school textbooks, imagine that in fourth grade you have one book and it has all of the subjects in it. The first page, so we’re talking 1940, even to the 60s, first page is “La historia religiosa”. Right front and center is religion. And that really contrasts with the decade before, which focused on democracy, democratic process, and “what is a republic?”, right? Another interesting thing about these textbooks, which are so fascinating, it’s particularly the originals. You know how when we’re kids we draw? It’s just amazing, I think I want to donate them to a museum or something. I got them in Spain in the flea market that’s on Sunday at El Rastro in Madrid. There’s a section for boys and a section for girls. In those two sections, it’s “What is a girl’s role in society and what is a boy’s role?”

AA: In the textbooks in the schools? Oh my goodness.

LD: Yep.

AA: Wow.

LD: I wish I had one here to show you. I bring them into the classroom and these kinds of historical primary sources are just fascinating for the students. We often think of historical progress in some kind of a straight line, and we’re going to the future and it’s more modern and somehow better. But history progress isn’t a straight line. So it’s really interesting to see how open-minded those textbook writers were in the early 1930s, how open-minded they were in comparison to those textbook writers in the 1950s and even ‘60s in Spain. That’s just one very concrete example that militarism as an ideology permeates education, but also media. It permeates comic books, it permeates toys. And so if we think about some of the main characteristics, militarism is a belief that the military must be used to suppress dissent, that force is the only means, the only possible way to protect national interests. You see the intersection of militarism, nationalism, and patriarchy.

There’s also the notion that the peaceful civilian is feminine, whereas the quintessential male is the warrior figure, right? And I think that these ideas around gender in many contexts have unified rank and file perpetrators, civilian bystanders, and genocidal architects. So it’s really important to think about that. Militarism is performative and pervasive. Militarism could not survive without the help of women, so it’s not just a gender identity that is supported by men. Anti-militarism can be supported by both men and women and those that don’t fit into that gender binary, but then conversely, militarism also could be supported by these different groups. So when we talk about the military dictatorship in Spain or in Chile, or we talk about these current crisis spots around the world, very clearly, these leaders could not have this power alone. We can never leave the dictators alone, that would be too easy to just villainize them. They do have a foundation of support and they protect that support through media and education and all of these other things that we’re talking about. But in all of these cases, you have those in the societies that very much want a different kind of Spain or Chile or Russia. So yes, gender matters. It matters then, it matters now.

If we think about some of these current crisis spots, you have a certain nostalgia, like a right-wing nostalgia for military order. And there’s this idea that it is the military leader that can kind of clean up the politics that don’t function. It’s obviously very anti-democratic. And so it’s the politics of anti-politics. And so when you look at Spaniards or Chileans, there have been a lot of changes in both of those places. And I think that they have very feminist movements and there’s just so much going on and that’s super exciting, but you do have those nostalgics for Pinochet, for Franco. And for me it’s quite clear that when those 20-year-old Spaniards go out in the streets very much against the current socialist party, and they put their arm up in the fascist salute, so many of them have camouflage on, and the fascist salute means obey versus fight, you can very much see how militarism cannot be disconnected from gender norms. It’s very much interconnected.

AA: Mm-hmm. First I’ll say that this is reminding me so much of Riane Eisler’s conception of dominator cultures versus partnership cultures. And this is just the textbook definition of dominator culture, right?

LD: Yes.

AA: I was going to ask how Spain has moved on since the Franco regime. I know that there are still some aspects of patriarchy within Spanish culture, and I’m specifically thinking of that controversial kiss from the head of the Spanish Soccer Federation, just the masculine assumption of ownership over a woman’s body, that was such an unequal power dynamic if you even watch it happen.

LD: I’d be happy to talk about that. Spain today is a democracy, it’s considered a constitutional monarchy, if we think, for instance, of the case of the UK. There are differences, but there are similarities too. There is a king and queen but there are democratic elections, and in those democratic elections there are multiple parties ranging from the left to the right. And currently there’s a populist right wing party called Vox. And I bring this up because those supporters of Vox would very much be in support of that kiss and in defense of the coach’s entitlement to do something like that. Currently in Spain, that’s considered the far-right party, but surprisingly they have gained traction in the last decade. And on the other side you still have a communist party that was made legal again in the early 1980s. So there was the transition to democracy from ‘75 to about ‘83, but in the early ‘80s there was still this fear that the military could take over once again. There was an attempted coup actually, but that attempted coup did not turn into a civil war and a military dictatorship. In this case, the king intervened and wanted to uphold the democracy that Spain had been developing at that time.

So, in the 1980s and ‘90s, you had this opening up. It’s not that the Franco regime and the conservatives were able, like in other places, to completely suppress dissent. So there were many in Spain during the Franco regime who resisted in a variety of ways. And resistance, it comes in many different forms. It’s not just physical resistance, it can be through literature and writing in kind of allegorical terms. Feminism began to grow more in the ‘70s and ‘80s in Spain. And also the left and the socialist party, El Partido Socialista (PSOE), really gained a lot of support. Particularly in the ‘90s and in the last few decades, Spain has made enormous strides. There’s such an active feminist community in Spain. I had the privilege and honor to march on March 8th, which is International Women’s Day. Right before COVID, it was March 8th, 2020. And this was a real demonstration, keeping with your point about what is the cultural ethos of the moment? What is Spain like now? On the 8th of March this huge demonstration was recognizing the gains that those fighting for equality have made, but also recognizing what needs to be done as well.

this huge demonstration was recognizing the gains that those fighting for equality have made, but also recognizing what needs to be done

So you have this massive, very progressive feminist movement in Spain, and you have, I would say, a very large population of heterosexual cisgender men that are very critical of that militarized masculine identity. And then obviously there’s a very thriving LGBTQI+ community in Spain that questions the past. But, like I said, when you make these different gains you have backlash. And so right now it is important to keep your eye on Spain and keep your eye on Vox, the party that I spoke about. Santiago Abascal is very much in line with the Putin/Trump identity. You mentioned Putin’s physical display of his body and being a representation of this militarized masculinity that he wants to put forward. Santiago Abascal did the same thing on a horse as well in an ad. So militarized masculinity is alive and well, but I would also say that anti-militarized masculinity is very alive and well too. I think that we just need to put it more into our language. Militarized masculinity needs to be a term that we use, because when we use these concepts we can identify them more easily, right?

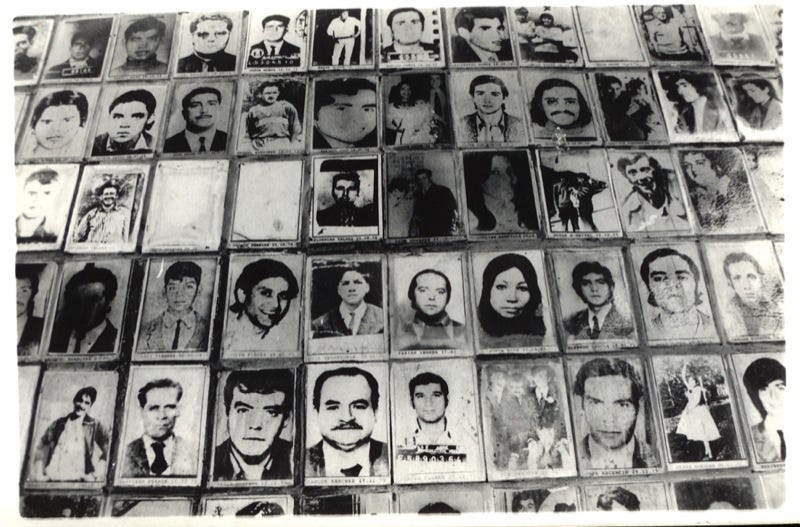

AA: For sure. Wonderful. Thank you so much for that. We’re going to pivot to Latin America now and talk about Chile. And as I mentioned a little earlier, I lived in Chile for a year and a half. I was a Mormon missionary there and I had never heard of Pinochet. That’s how they say it in Spanish, you might’ve heard Pinochet, for listeners, I say Pinochet because that’s how they say it there. But I didn’t know anything about the conflict that had happened in the ‘70s. I was riding on a bus in the city near downtown Santiago, and we went past some apartment blocks, these big buildings, and there were hundreds of really large black and white photos of young people’s faces that had been put on the sides of these apartment buildings. And I remember shivering from head to toe, and I could just feel that something really horrible had happened, that there was a haunting quality to those faces, even though I didn’t know. And then kind of in bits and pieces, like missionaries weren’t allowed to go out on the 18th of September because there were protests. And I thought, “Protests of what? What happened?” And gradually, after living there for a while, I heard about the history from Chileans. And I actually learned a lot about it through protest music that people still listen to, like Víctor Jara. And when I came home, I looked it up and learned about the history more and just cried and cried with grief about what had happened and the U.S.’s role in that military coup.

I also recommended that listeners read The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende. That’s a novelization of what happened, and she was the niece or maybe the step-niece or the great-niece of Salvador Allende, who was assassinated in that coup. Anyway, I have a personal connection. Another piece of media is a song about the Chilean cueca by Sting. I don’t even remember–

LD: ‘They Dance Alone’.

AA: ‘They Dance Alone’. It’s a traditional Chilean dance called the cueca, which is traditionally done with a man and woman, and it’s these haunting images of women with their disappeared son or their disappeared husband on their chest because they’ve lost this beloved man in their family to this militarized masculinity, this military event in their country. Anyway, that’s my personal connection to Chile, and I would love for you to now tell us the story, Lisa, about what happened in Chile in the ‘70s.

LD: Yeah. It’s really interesting to think about some of the relationships between Spain and Chile. Allende very much supported, from Chile, the Second Republic. And in the meantime, Pinochet admired Franco from afar. Franco in many ways was a role model for Pinochet. And so you had, in both cases, this very progressive moment. Under Allende from 1970 to 1973, you had an economic reform, agrarian reform, an agenda to minimize this enormous gap between the rich and the poor. And that was similar to Spain in the 1930s. And so in the three years that Allende and the Popular Unity sought to implement different reforms that would benefit a whole range of marginalized groups, in those three years, those groups that felt threatened by those reforms, including business elites in the United States who partnered with business elites in Chile. One of the biggest industries in Chile is copper and the United States has very much depended on cheap Chilean copper, so the profits were going to be in question with these empowering steps that the Popular Unity was taking. And so there were sabotage actions during the three years that Allende was in power. It created a more polarized situation than what was already a polarized context. And it created a lot of instability and the United States did contribute to that instability. So, what happened? Well, that instability created the idea, for those who otherwise would support Allende, that things were not going well. You had those who never supported Allende on the far right, that right from the beginning were against the kind of reforms that the Popular Unity was putting forward. And then you had this whole spectrum. You had those kind of in-the-middle Christian Democrats, but they were conservative, who ended up supporting the coup because of a lot of this political and economic instability. There was high inflation at this time.

But we really need to think about all of the actions that created that situation. Instead of looking at the complexity of it, those who supported the coup and those different international actors just wanted to see it as the Allende socialist democracy that was not going to work. And of course that would be a big threat to the United States and U.S. interests throughout Latin America. Because Allende believed in democratic process, and so if you can peacefully establish a socialist, very forward-looking, more equal society, very different from the Cuban model, it could have been an enormous role model for other Latin American countries. So, many against these reforms were very much afraid of the power of someone like Allende, who was not a military man. He was a doctor originally, doctor turned politician. We think of Che Guevara, he was a medical student turned revolutionary. Allende, on the other hand, was doctor turned politician, and he believed in the democratic process. So the military coup took place in 1973. And unlike the case of Spain, a full-scale civil war did not break out, in part because those in the military that would have defended democracy were already targeted and taken out. And that’s pretty important to think about. So there was this fairly unified armed force, the armed forces, that took hold in 1973 to 1980, those were the most repressive years.

AA: Sorry, Lisa, could you back up and describe how Pinochet murdered Allende? Who did they kill? Who did they disappear? Like right at the beginning, and then maybe talk about the oppression. Can you tell that moment too?

LD: Yes. So, there was a very strategic plan that the armed forces carried out, and it involved numerous cities in Chile. But the point of attack, which was so symbolic, was La Moneda. And La Moneda is kind of like the White House in the United States. So imagine the White House being bombed by the military leadership. I don’t want to jump around too much, but I think, for instance, with the January 6th insurrection in the United States, my eyes and those of us who have studied military dictatorships, we’re looking at the military. What’s the military going to do? What’s the military leadership going to do? And fortunately, they sided with democracy and democratic process and did not side with the insurrectionists, right? So key. So, the bombing of the presidential palace, La Moneda, took place on September 11th. Chile had a September 11th before we did, in 1973.

So the armed forces took hold of the interior and Salvador Allende was in his office, and from his office he transmitted a very important speech to the Chilean people saying “don’t give up,” and he did not want to surrender. And while it was uncertain for a little while, he did kill himself, but he also didn’t have very many alternatives. He could have been forced into exile, killed, but he decided to take his life into his own hands, which was very tragic and in many ways turned Allende into a martyr, which the military regime did not want at all. So his family went into exile, and many of those Allende supporters in Santiago were rounded up and put in the soccer stadium, the national stadium. And in the beginning it was quite chaotic. I mean, even if you weren’t a card-carrying student socialist, even if you had some kind of relationship to someone who was politically active, you were also targeted and rounded up.

Then, in 1975, the repression became more focused and there was a whole network of secret service agents. They were called the DINA, and it’s kind of like the CIA in Chile. And actually there are some connections between our CIA and the secret service in Chile. And so the regime created a culture of fear. One of the enormous consequences was social fragmentation. Families and friends were broken apart because there was so much fear of what could happen. Torture behind closed doors functioned for three main reasons: one, to get information about who was plotting against the regime, two, to punish those who had resisted, and three, to send a very powerful signal to anyone else that if you try to organize against this military government, the consequences will be harsh. So, many went into exile. But in the meantime, and I think that this is always really important to emphasize, there were so many brave Chileans that continued the fight in various ways, some in exile, some on the ground in Chile, in various ways acting very courageously against the military regime.

AA: And these are the faces that I saw on the side of those buildings, are the disappeared, right?

LD: Yes.

AA: And what really hits me too, especially now that my kids are the age that it would have been, like so many families lost college students. They were college students that were fighting for a better world, these idealistic kids in their twenties, and they just disappeared and never knew what happened to them. And as far as I know, there are still families that never had that closure of knowing what happened to their children during that time.

LD: Yeah, that’s absolutely correct. And I think that cultural production, like documentary film and literature and testimonies, feature films, they play a very big role in educating the public, uncovering, complicating, finding new pieces that haven’t been explored. There was a truth commission in Chile, unlike the case of Spain. So there was a transition to democracy, there was a plebiscite, a yes or no vote in 1989. And it was very difficult because so many people were afraid to go out and vote “No” for the continuation of the dictatorship. They were either afraid or they thought it was going to be rigged, so what’s the point anyways? But there was a pretty solid “No” campaign, and this is represented in a film called No, which I recommend. Like any cultural representation, it tells a certain point of view. In this case, it shows how the “No” campaign convinced many to get out and vote. And indeed in 1990, the no vote won over the yes vote, but you have to keep in mind that the yes vote, and don’t quote me on this, but I think it was around 46-47% voted for Pinochet’s neoliberal military regime. And when I say neoliberal, I’m not talking about liberal socially, but neoliberal meaning neoliberal economic policies, low taxes, minimum government intervention in business, but maximum military government intervention in politics. So, I mean, there are two sides to that coin of big government, right?

there were so many brave Chileans that continued the fight in various ways, some in exile, some on the ground in Chile, in various ways acting very courageously against the military regime.

AA: Oh yeah.

LD: So there’s a “no” to big government when it comes to the government wanting to improve the lives of the marginalized. That’s overreach. But then when it comes to controlling what can or cannot be said against that regime, you have complete overreach. That’s the irony of it, right?

AA: And gay marriage and women’s reproductive rights, they’re perfectly fine with government control in those areas.

LD: Exactly. That’s the point.

AA: And we’re feeling, I mean, so much of what you’ve said today I just think it is kind of scary because this is what it feels like in some ways in our country right now. The polarization, like you said it was a 46% vote for Pinochet, I just thought, yep, that’s how it’s feeling. We’re on the knife’s edge right now with this backlash against some of the progress that’s been made. So it’s very, very relevant. Sadly, we’re at the end of our conversation already, but I’ll ask you my last question, what are some takeaways from your research? And as we’re seeing more and more in our country, in other countries across Europe, which you alluded to, as we’re seeing these strongmen start to take hold, not just in Europe, I feel like it’s everywhere right now. What can a normal person do to resist this and to resist this militarized and hyper-masculine ideology?

LD: Well, while it sounds kind of cliché, you have to start with yourself. You have to start with yourself and think about your own daily activities. What kind of media do you consume, for instance, and how do you vote, how do you speak? The kind of language that we use, there are very small things that are actually quite huge things that we can do on a daily basis. I really do believe that there’s a continuum of violence, of state violence, dictatorial violence, genocide. It doesn’t come popping out of nowhere. There are a lot of things that happened before. For instance, if we turn to the United States, during the Trump years, violence was very much normalized through the discourse of Donald Trump that made it okay to talk about groups in a certain way and talk about aggression and violence in a certain way. So by starting with yourself and by thinking critically about jokes that marginalize and degrade certain groups, on a daily basis you can intervene in that way. And those might seem like very small things, but they actually aren’t.

And I think more broadly, this is something that’s been said so many times, but education is so important. Talking about what is so normalized, like to de-normalize. I think that that’s something I’d say. What can we do? We can de-normalize the normalization of violence and this idea of male dominance as being the true sign of masculinity. On a daily basis, there are things that we can do in our conversations, in our reading, and what we consume. There are ways that we can resist that.

AA: Wonderful. Well, that brings us to the end, Lisa. Thank you so much for bringing your expertise and your research to the episode. I’m so grateful to have learned so much today, and thank you for being here.

LD: Thank you for having me.

It almost seems that it’s the air we breathe and the water we swim in

like gender norms

Listen to the Episode

&

Share your Comments with us below!